Abstract

Assessing the correlation between molecular endpoints and cancer induction or prevention aims at validating the use of intermediate biomarkers. We previously developed murine models that are suitable to detect both the carcinogenicity of mainstream cigarette smoke (MCS) and the induction of molecular alterations. In this study, we used 931 Swiss mice in two parallel experiments and in a preliminary toxicity study. The chemopreventive agents included vorinostat, myo-inositol, bexarotene, pioglitazone and a combination of bexarotene and pioglitazone. Pulmonary micro-RNAs and proteins were evaluated by microarray analyses at 10 weeks of age in male and female mice, either unexposed or exposed to MCS since birth, and either untreated or receiving each one of the five chemopreventive regimens with the diet after weaning. At 4 months of age, the frequency of micronucleated normochromatic erythrocytes was evaluated. At 7 months, the lungs were subjected to standard histopathological analysis. The results showed that exposure to MCS significantly downregulated the expression of 79 of 694 lung micro-RNAs (11.4%) and upregulated 66 of 1164 proteins (5.7%). Administration of chemopreventive agents modulated the baseline micro-RNA and proteome profiles and reversed several MCS-induced alterations, with some intergender differences. The stronger protective effects were produced by the combination of bexarotene and pioglitazone, which also inhibited the MCS-induced clastogenic damage and the yield of malignant tumors. Pioglitazone alone increased the yield of lung adenomas. Thus, micro-RNAs, proteins, cytogenetic damage and lung tumors were closely related. The molecular biomarkers contributed to evaluate both protective and adverse effects of chemopreventive agents and highlighted the mechanisms involved.

Introduction

Assessing the correlation between cancer and modulation of molecular endpoints in experimental models is essential for validating the use of intermediate biomarkers in humans. This correlation would apply to the prediction of carcinogenic risks and to evaluation of chemopreventive agents in terms of both safety and efficacy. In fact, the lack of appreciable changes in the baseline profiles of molecular endpoints would indicate that an agent is potentially safe, whereas the ability to counteract the alterations induced by carcinogens indicates that an agent is potentially efficacious. In addition, information on the mechanisms involved is a prerequisite for a rational implementation of chemoprevention measures in humans.

Despite the dominant role of cigarette smoke (CS) in the epidemiology of cancer and other chronic diseases, it is difficult to reproduce these pathological conditions in animal models. We developed a murine medium-term bioassay in which exposure early in life to CS, especially mainstream CS (MCS), results in a potent carcinogenic response (1,2). In addition, genomic and postgenomic technologies are applied to study the effects and the mechanisms of CS-induced diseases (3).

The most obvious way to prevent CS-induced diseases is to refrain from smoking or to quit smoking. Chemoprevention provides a complementary strategy that can be targeted to protect (i) current smokers who are addicted to CS, (ii) passively exposed subjects and (iii) ex-smokers, who constitute a broad proportion of the population. In previous studies, we investigated inhibition of MCS-induced tumors by various chemopreventive agents, either natural or synthetic, under conditions mimicking treatments of either current smokers (4,5) or ex-smokers (4), or even prenatal treatments (6,7). In other studies, we evaluated modulation of CS-related molecular endpoints, such as micro-RNAs (miRNAs) in both rats (8) and mice (9), and proposed the analysis of miRNA expression and proteome profiles as a tool for predicting the safety and efficacy of chemopreventive agents (10,11).

The goal of this study was to correlate the induction of tumors and alterations of molecular endpoints by MCS in mice and their inhibition by chemopreventive agents, some of which are already in use for therapeutic purposes in humans. In particular, vorinostat (VOR) or suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (Zolinza®) is an inhibitor of histone deacetylase that selectively upregulates Cx43 expression (12), whereas bexarotene (BEX) or 9cUAB30 (Targretin®) is a retinoid X receptor (RXR)-specific retinoid. Both drugs are proposed for treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (13). Pioglitazone is a synthetic ligand of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) (14) and is approved for the therapy of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Myo-inositol (MYO), or cis-1,2,3,5-trans-4,6-cyclohexanehexol, a food constituent, has anticancer properties (15). Based on mechanistic considerations, we also tested a combination of BEX and PIO.

The data presented here demonstrate the validity of the investigated biomarkers for predicting both the carcinogenic response to MCS and their modulation by chemopreventive agents. The results highlight some protective effects of the investigated agents but also point out possible adverse effects that should be taken into account in view of applications in humans.

Materials and methods

Mice

A total of 340 postweanling Swiss ICR (CD-1®) mice (Harlan Laboratories, San Pietro al Natisone, Udine, Italy), 107 neonatal mice of the same strain and 484 neonatal Swiss H mice bred in the animal house of the National Center of Oncology (Sofia, Bulgaria) were used. The mice were housed in MakrolonTM cages on sawdust bedding and maintained on standard rodent chow and tap water ad libitum. The animal room temperature was 23±2°C, with a relative humidity of 55% and a 12 h day/night cycle. Housing, breeding and treatment of mice were in accordance with European (86/609/EEC Directive) and National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Chemopreventive agents

The chemopreventive agents MYO, VOR, BEX and PIO were supplied by National Cancer Institute through Thermo Fisher Scientific (Germantown, MD). The agents were incorporated in the diet at four doses each (see below). Standard rodent chows in powder (Kostinbrod, Sofia, Bulgaria, and Teklad 9607, Harlan Laboratories) were used.

Subchronic toxicity study

The chemopreventive agents were administered at four dose levels each to postweanling Swiss ICR (CD-1®) mice. The mice were divided into 18 groups, each composed of 10 males and 10 females.

Group A included mice kept in filtered air (sham exposed); Groups B, C, D and E included mice treated with MYO at 8000, 4000, 2000 and 1000mg/kg diet, respectively; Groups F, G, H and I included mice treated with VOR at 1000, 500, 250 and 125mg/kg diet, respectively; Groups J, K, L and M included mice treated with PIO at 240, 120, 60 and 30mg/kg diet, respectively; Groups N, O, P and Q included mice treated with BEX at 240, 120, 60 and 30mg/kg diet, respectively.

The mice were treated for 6 weeks, during which they were weighed at weekly intervals and were inspected daily to detect possible interim deaths, signs of morbidity and behavioral alterations.

Exposure to MCS

A whole-body exposure to MCS of neonatal Swiss ICR (CD-1®) mice (Genoa Laboratory) and Swiss H mice (Sofia Laboratory) was achieved by burning Kentucky 3R4F reference cigarettes (University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY) and commercially available cigarettes (Melnik King Size, Bulgartabac), respectively, as described previously (1). The average concentrations of total particulate matter in the exposure chambers were 605 and 584mg/m3, respectively.

Modulation of miRNA expression by MCS and chemopreventive agents

This study included the same 18 groups of mice (A–Q) used in the subchronic toxicity study plus 5 additional groups.

Group R included postweanling mice treated for 6 weeks with a combination of PIO at 120mg/kg diet and BEX at 240mg/kg diet (10 males and 11 females); Group S included neonatal mice exposed to MCS for 10 weeks, starting at birth (10 males and 11 females); Group T included MCS-exposed mice treated for 6 weeks, after weaning, with PIO at 120mg/kg diet (14 males and 10 females); Group U included MCS-exposed mice treated for 6 weeks, after weaning, with BEX at 240mg/kg diet (10 males and 10 females); Group V included MCS-exposed mice treated for 6 weeks, after weaning, with a combination of PIO at 120mg/kg diet and BEX at 240mg/kg diet (10 males and 11 females).

At 10 weeks of age, all 447 mice from Groups A–V were killed by CO2 asphyxiation, and the lungs were collected. RNA was extracted from the right lungs by using Triazol and column chromatography and kept at −80°C. One to three lung pools were prepared within each experimental group and gender, for a total of 82 pools. Quantification of RNA and evaluation of its integrity were performed as described previously (8). miRNA analyses were performed by using a microarray platform containing quadruplicates of 1969 miRNAs, 694 of which were mouse specific and 1275 were human specific (miRCURY LNATM microRNA Array, fifth generation, EXIQON, Vedbaek, Denmark). A total of 312 miRNAs overlapped in mice and humans. Modulation of the expression of two miRNAs (let-7 and miR-125) by MCS and chemopreventive agents was confirmed by real-time quantitative PCR, as described previously (8). The miRNA microarray data are available at GEO database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/, GEO number requested).

Modulation of proteome profiles by MCS and chemopreventive agents

A total of 1164 proteins were evaluated in the lung samples pooled from 12 experimental groups (Groups A, B, F, K, N and R−V). The proteins were purified from left lung homogenates and labeled by fluorescent tracers. For each sample, 20 μg of protein was diluted in Extraction/Labeling Buffer (Clontech) and then labeled by incubation at 4°C for 2h with either Cy3 or Cy5 monofunctional protein—reactive dyes (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK). The labeled proteins were purified by elution with Desalting Buffer in Protein Desalting Spin Columns (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Purified labeled proteins were quantified by the bicinchoninic acid method using a NanoDrop ND-1000 nanospectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, NC). The proteins of each sample were hybridized on two glass microarrays. The Clontech Ab Microarray 500 was coated with 508 antibodies spotted in duplicate (Clontech, Mountain View, CA), and the Explorer Antibody Microarray was coated with 656 antibodies in duplicate (Full Moon BioSystems, Sunnyvale, CA). Microarray hybridization was performed at room temperature for 40min with continuous shaking. The slides were carefully washed with gentle rocking, dried by centrifugation and analyzed by laser scanning and fluorescence detection.

Modulation of MCS-induced cytogenetic damage and lung tumors by chemopreventive agents

This study used a total of 486 neonatal Swiss H mice, divided into 7 experimental groups.

Group A included control mice kept in filtered air since birth throughout the whole experiment (sham-exposed mice, 33 males and 31 females); Group B included mice exposed for 4 months to MCS, starting within 12h after birth, and thereafter kept in filtered air for 3 additional months (34 males and 38 females); Group C included MCS-exposed mice treated with MYO at 8000mg/kg diet, starting at weanling (4–5 weeks) and continuing until the end of the experiment (34 males and 37 females); Group D included MCS-exposed mice treated with VOR at 1000mg/kg diet, starting at weanling (4–5 weeks) and continuing until the end of the experiment (35 males and 35 females); Group E included MCS-exposed mice treated with BEX at 240mg/kg diet, starting at weanling (4–5 weeks) and continuing until the end of the experiment (35 males and 40 females); Group F included MCS-exposed mice treated with PIO at 120mg/kg diet, starting at weanling (4–5 weeks) and continuing until the end of the experiment (34 males and 35 females); Group G included MCS-exposed mice treated with a combination of PIO at 120mg/kg diet and BEX at 240mg/kg diet, starting at weanling (4–5 weeks) and continuing until the end of the experiment (31 males and 34 females).

After 4 months, peripheral blood smears were prepared from 140 mice (10 males and 10 females per group), stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa, and analyzed for the frequency of micronucleated normochromatic erythrocytes (NCE) (50 000 NCE per mouse).

The “spontaneously” moribund mice, which were housed separately, and all those mice that survived after 7 months were deeply anesthetized and killed by CO2 asphyxiation. A complete necropsy was performed, and the lungs were collected. The accessory, middle and caudal lobes of the right lung were cut into two pieces each, whereas the cranial lobe was left uncut. The left lung was cut into three pieces. This accounted for a total of 10 lung sections to be subjected to standard histopathological analysis (1).

Data analysis and statistical analysis

After local background subtraction, microarray data were log transformed, normalized and analyzed by GeneSpring® software version 7.2 (Silicon Genetics, Redwood City, CA). Expression data were median centered by using the GeneSpring normalization option. Comparisons between experimental groups were done by evaluating the fold variations of quadruplicate data generated for each miRNA and duplicate data generated for each protein. In addition, the statistical significance of the differences was evaluated by means of the GeneSpring analysis of variance applied by using Bonferroni multiple testing corrections. As inferred from volcano plot analysis, differences with P < 0.05 and >2.0-fold variations between experimental groups were taken as significant.

Comparisons between groups regarding survival of mice and incidence of tumors were made by chi-square analysis. Body weight, frequency of micronucleated NCE, and multiplicity of histopathological lesions were expressed as means ± SE of the mice composing each experimental group, and comparisons between groups were made by Student’s t-test for unpaired data.

Results

Subchronic toxicity study

After 6 weeks of treatment, there was no spontaneous death and no apparent morbidity or behavioral alterations in any group. A statistically significant (P < 0.05) loss of body weight, compared with controls, was only observed in male mice treated with PIO at 240mg/kg diet (data not shown). Based on these results, it was decided to use the chemopreventive agents at the following doses: MYO 8000mg/kg diet, VOR 1000mg/kg diet, PIO 120mg/kg diet and BEX 240mg/kg diet.

Intergender differences in baseline miRNA and proteome profiles

There were some intergender differences in the baseline miRNA and protein profiles. In fact, the expression of four miRNAs and four proteins in sham-exposed mice was significantly different in the two genders. In particular, a higher baseline expression in males than in females was detected for miR-216 (2.4-fold) and miR-684 (2.8-fold), whereas a higher expression in females than in males was detected for miR-302 and miR-499 (both 2.1-fold). Three proteins, including Itchy homolog E3 ubiquitin protein ligase (Swissprotein code Q5QP37), epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate 8 (Swissprotein code Q12929) and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (Swissprotein code P39689), were higher in males than in females, whereas endothelial nitric oxide synthetase 2; Swissprotein code P70313) was higher in females than in males.

Effect of MCS on miRNA and proteome profiles

Exposure of mice to MCS extensively dysregulated the expression of pulmonary miRNAs, mainly in the sense of downregulation. In fact, the 11.4% of the miRNAs tested (79 of 694) were downregulated >2-fold compared with sham-exposed mice.

Females were more susceptible to MCS-related miRNA dysregulation than males. In particular, four miRNAs, miR-126 (sham/MCS ratio = 2.5-fold), miR-145 (2.2-fold), miR-684 (2.5-fold) and miR-946a (2.1-fold), were downregulated >2-fold and with a statistically significant difference in males but not in females. In contrast, 16 miRNAs showed an opposite trend, being significantly downregulated by MCS in females but not in males, with sharp intergender differences: let-7f (sham/MCS ratio = 6.8-fold), miR-125b (5.9-fold), miR-208b (6.9-fold), miR-296 (3.0-fold), miR-297a (6.4-fold), miR-466a (7.7-fold), miR-466b (2.4-fold), miR-466e (6.4-fold), miR-467g (6.5-fold), miR-574 (7.9-fold), miR-668 (5.4-fold), miR-669h (6.1-fold), miR-709 (5.9-fold), miR-744 (6.7-fold), miR-2141 (5.6-fold) and miR-2143 (5.3-fold).

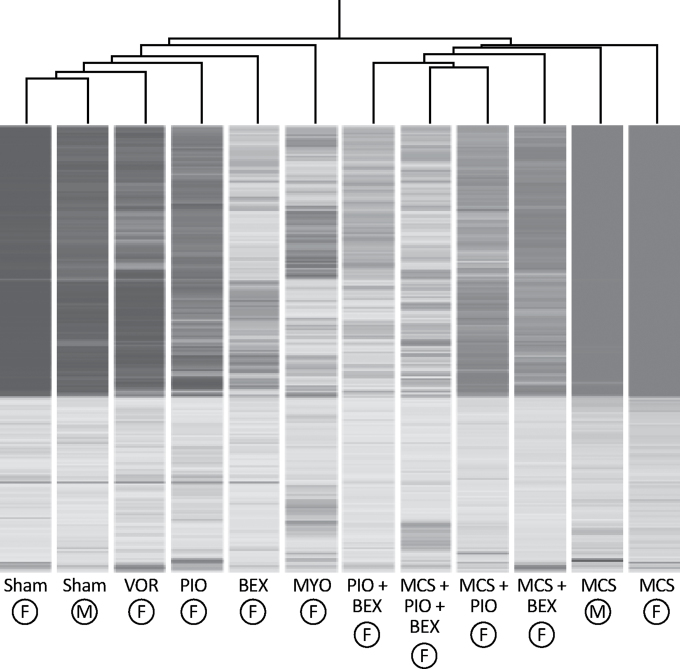

On the other hand, the pulmonary proteome was mainly dysregulated by MCS in the sense of upregulation. In fact, the 5.7% of the proteins tested (66 of 1164) were upregulated >2-fold compared with sham-exposed mice. The hierarchical cluster analysis reported in Figure 1 shows that proteome profiles in sham-exposed mice and MCS-exposed mice of both genders fell at the opposite extremities of the dendrogram.

Fig. 1.

Hierarchical cluster analysis showing modulation of proteome profiles in the lung of both male (circled M) and female (circled F) mice exposed to MCS, compared with sham-exposed mice, and effect of the chemopreventive agents MYO (8000mg/kg diet), VOR (1000mg/kg diet), PIO (120mg/kg diet), BEX (240mg/kg diet) and a combination of PIO (120mg/kg diet) and BEX (240mg/kg diet) either in sham-exposed or in MCS-exposed female mice.

There were intergender differences in proteome profiles as a response to MCS, mostly in the sense of a more remarkable induction of protein expression by MCS in females than in males. This trend was detectable for proteins involved in inflammation, stress response, signal transduction, xenobiotic metabolism, apoptosis, cell proliferation and intracellular vesicle trafficking. Details are given in Supplementary Results (SR 1), available at Carcinogenesis Online.

Modulation of baseline miRNA and proteome profiles by chemopreventive agents

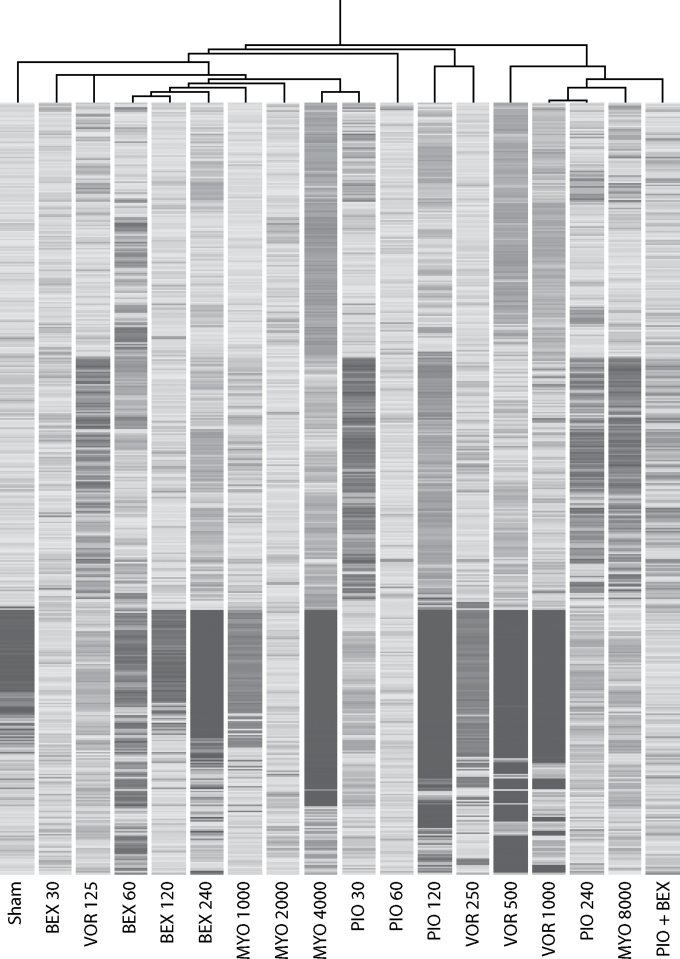

Figure 2 shows at a glance the dose-dependent ability of the examined chemopreventive agents to change the baseline miRNA expression profile in mouse lung. In detail, MYO significantly dysregulated nine miRNAs, six in the sense of upregulation, including miR-302 (2.0-fold), miR-509 (1.8-fold), miR-592 (1.8-fold), miR-876 (1.9-fold), miR-880 (1.8-fold) and miR-1953 (1.7-fold), and three in the sense of downregulation, including miR-543 (1.9-fold), miR-764 (2.6-fold) and miR-1901 (2.0-fold). VOR produced some alterations of miRNAs in sham-exposed mice, with dose-dependent effects. In particular, miR-107 was downregulated (1.5-fold), whereas miR-106 (1.5-fold), miR-183 (2.0-fold) and miR-1961 (1.6-fold) were upregulated by VOR. Boxplot, scatter plot, and volcano plot analyses (data not shown) provided evidence that modulation of miRNA expression by VOR is more pronounced in males than in females. In fact, at doses >500mg/kg diet, VOR dysregulated the expression of 10 miRNAs in males and of 4 miRNAs in females. In particular, in males, VOR upregulated let-7g (8.0-fold), let-7i (6.9-fold), miR-106 (1.7-fold), miR-125b (5.6-fold), miR-183 (2.4-fold), miR-466k (4.3-fold) and miR-466j (3.4-fold), and downregulated miR-20 (1.9-fold), miR-684 (2.4-fold) and miR-764 (2.8-fold). In females, VOR upregulated miR-125b (2.2-fold), miR-206 (1.7-fold) and miR-183 (1.8-fold), and downregulated miR-302a (2.4-fold). Four miRNAs, miR-293 (1.6-fold), miR-509 (1.6-fold), miR-551b (1.7-fold) and miR-592 (1.6-fold), were upregulated by PIO, whereas six miRNAs, miR-218 (2.2-fold), miR-296 (2.6-fold), miR-335 (3.2-fold), miR-376b (1.7-fold), miR-764 (2.2-fold) and miR-1893 (1.6-fold), were downregulated by PIO. BEX significantly upregulated the expression of miR-1905 (1.6-fold) and miR-1934 (1.5-fold) and downregulated the expression of miR-543 (1.6-fold) and miR-1937 (1.4-fold). Male mice were more sensitive than female mice to BEX-induced miRNA modifications (data not shown). Six miRNAs, miR-129 (1.7-fold), miR-299 (1.8-fold), miR-302 (1.7-fold), miR-483 (1.8-fold), miR-877 (2.1-fold) and miR-2182 (1.9-fold) were upregulated by the combination of PIO and BEX.

Fig. 2.

Hierarchical cluster analyses evaluating the ability of the chemopre ventive agents MYO (1000, 2000, 4000 and 8000mg/kg diet), VOR (125, 250, 500 and 1000mg/kg diet), PIO (30, 60, 120 and 240mg/kg diet), BEX (30, 60, 120 and 240mg/kg diet) and a combination of PIO (120mg/kg diet) and BEX (240mg/kg diet) to change the baseline expression of pulmonary miRNAs compared with sham-exposed mice.

None of the five examined chemopreventive regimens dramatically altered the baseline lung proteome (Figure 1). The major exception was represented by the combination of BEX and PIO, which clustered far away from sham. In particular, as detailed in Supplementary Results (SR 2), available at Carcinogenesis Online, treatment with MYO considerably increased the expression of six proteins involved in cell proliferation and differentiation, signal transduction, stress response and inflammation. Treatment with VOR increased the expression of five proteins involved in the control of cell replication, signal transduction and tissue integrity maintenance, and decreased the expression of histone deacetylase [Supplementary Results (SR 3), available at Carcinogenesis Online]. PIO upregulated 12 proteins involved in intracellular trafficking, antioxidant response, modulation of Ras expression, maintenance of tissue integrity, apoptosis, insulin response, stress response and peroxisome biogenesis [Supplementary Results (SR 4), available at Carcinogenesis Online]. Of the proteins modulated by BEX, one protein is involved in cell proliferation and three proteins in cell differentiation [Supplementary Results (SR 5), available at Carcinogenesis Online].

Modulation of MCS-altered miRNA and proteome profiles by PIO, BEX and their combination

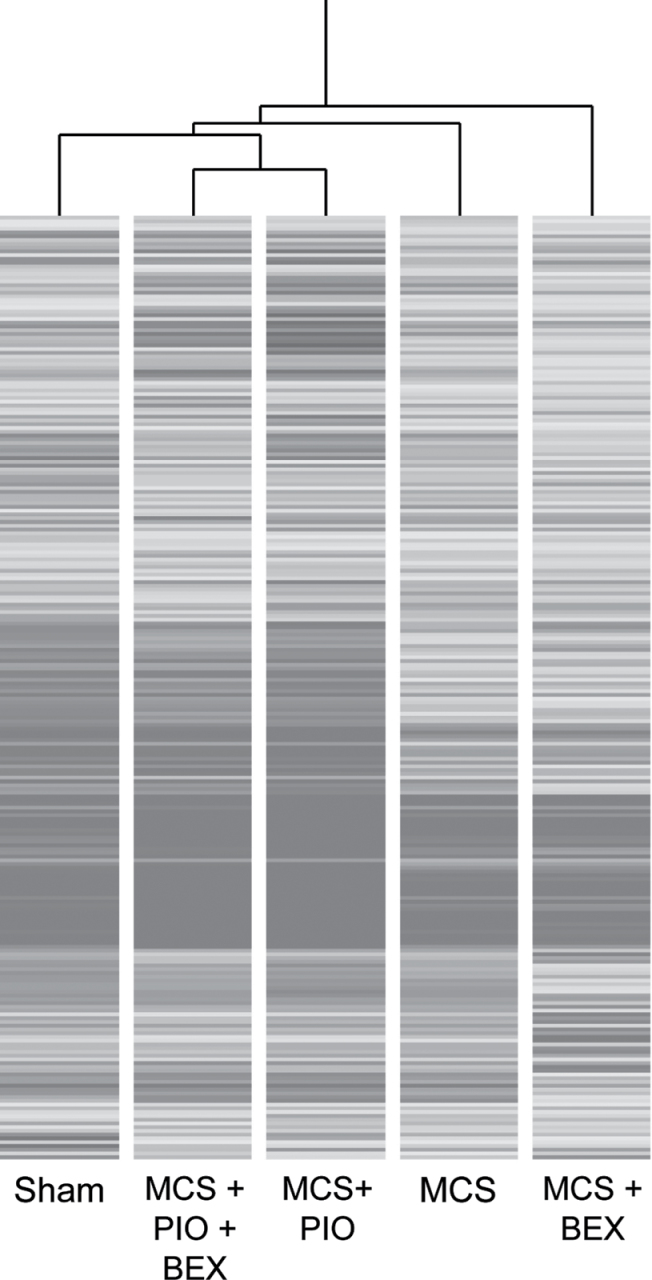

BEX alone did not appreciably reverse the miRNA alterations produced by MCS, whereas PIO was more efficient. Combination of PIO and BEX was the most effective treatment in approaching the baseline profile recorded in sham-exposed mice (Figure 3).

Fig. 3.

Hierarchical cluster analysis evaluating the ability of PIO and BEX, either alone or in combination, to modulate the expression of 694 miRNAs in the lung of MCS-exposed mice.

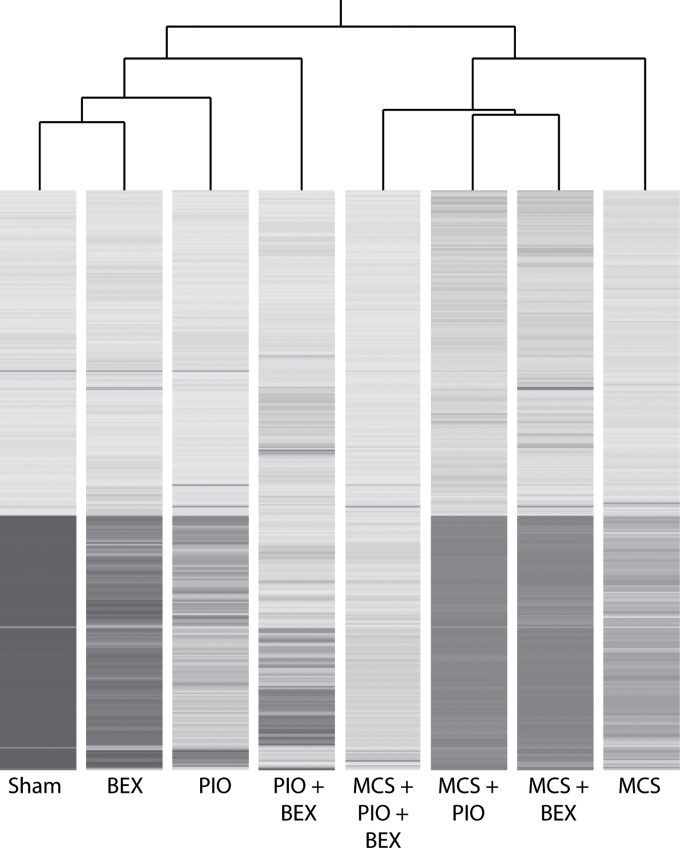

Both PIO and BEX were able to reverse the MCS-induced proteome alterations to some extent, but both were still linked with MCS in the dendrogram (Figure 4). As detailed in Supplementary Results (SR 4), available at Carcinogenesis Online, the MCS + PIO/sham ratio was at least 2-fold higher than the MCS/sham ratio for five proteins that were upregulated by PIO in sham-exposed mice. On the other hand, the MCS/sham ratio was higher than the MCS + PIO/sham ratio for Ras, whose expression was not affected by PIO in sham-exposed mice. The MCS + BEX/sham ratio was slightly but significantly higher than the MCS/sham ratio for epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate 8 and lower for hRXR [Supplementary Results (SR 5), available at Carcinogenesis Online]. Combination of PIO and BEX was more effective than either individual agent in modulating MCS-related proteome alterations (Table I).

Fig. 4.

Hierarchical cluster analysis showing modulation of proteome profiles in the lung of female mice, either sham exposed or MCS exposed, as related to treatment with PIO (120mg/kg diet), BEX (240mg/kg diet) and a combination of PIO and BEX.

Table I.

Modulation of lung protein expression by the combination of PIO and BEX, relatively to those proteins that were significantly modulated by either PIO alone (A) or BEX alone (B) in sham-exposed mice and MCS-exposed mice

| Protein | Fold variation as related to sham | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIO | BEX | MCS | MCS + PIO | MCS + BEX | MCS + PIO + BEX | |

| A | ||||||

| Sorting nexin | 6.6 | 5.5 | 5.8 | 3.6 | ||

| Thioredoxin | 6.0 | 0.6 | 4.7 | 4.6 | ||

| Ras | 1.0 | 4.0 | 2.8 | 1.1 | ||

| Multiple PDZ domain protein | 6.2 | 0.6 | 2.7 | 5.3 | ||

| RAS p21 protein activator 1 | 1.9 | 4.5 | 4.9 | 4.7 | ||

| Sp1 transcription factor | 7.5 | 5.4 | 7.2 | 6.9 | ||

| Insulin-like growth factor binding protein | 7.0 | 0.8 | 5.7 | 5.6 | ||

| Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase | 1.9 | 6.2 | 6.9 | 3.5 | ||

| BCL2-like 1 | 1.9 | 6.1 | 6.3 | 5.2 | ||

| Peroxisome biogenesis factor | 10.1 | 1.0 | 5.3 | 4.7 | ||

| Peroxisomal D3,D2-enoyl-CoA isomerase | 8.7 | 0.8 | 4.6 | 6.7 | ||

| PPARγ | 2.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 2.3 | ||

| B | ||||||

| Epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate 8 | 4.0 | 6.5 | 7.7 | 6.6 | ||

| Keratin (pan) | 0.7 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 0.9 | ||

| Cell division cycle 27 | 1.5 | 6.1 | 5.8 | 3.7 | ||

| Retinoid X receptor (hRXR) | 2.1 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 2.4 | ||

Survival and body weights of Swiss H mice in the chemoprevention study

Supplementary Table I, available at Carcinogenesis Online, summarizes the data relative to survival and body weights. Survival of MCS-exposed mice after 4 months was high, excepting the mice treated with VOR and especially with the combination of PIO and BEX. At the end of the experiment, there was a poor survival in all MCS-exposed mice. Treatment of MCS-exposed mice with either PIO or BEX resulted in a significant protection against MCS lethality.

Exposure of mice to MCS significantly decreased the body weights at weaning and after 4 months compared with sham-exposed mice. Body weights recovered to control levels 3 months after discontinuation of exposure to MCS. A significant loss of body weight was recorded in MCS-exposed males treated with VOR and females treated with PIO + BEX. On the contrary, PIO alone exerted protective effects against the MCS-induced loss of body weight.

Modulation by chemopreventive agents of MCS-induced cytogenetic damage

At 4 months of age, at the end of the period of exposure to MCS, the frequencies of micronucleated NCE (means ± SE) in sham-exposed Swiss H mice were 1.5±0.08 ‰ (males) and 1.2±0.07‰ (females), and those in MCS-exposed mice were 2.7±0.23‰ (males, P < 0.01) and 1.9±0.08‰ (females, P < 0.01). Individually, MYO, VOR, PIO and BEX did not significantly affect the MCS-related cytogenetic damage (data not shown). The combination of PIO and BEX significantly attenuated the MCS-induced cytogenetic damage in male mice (2.1 ± 0.18‰, P < 0.05).

Modulation of preneoplastic and neoplastic alterations in the lung of MCS-exposed mice

As shown in Table II, exposure of mice to MCS for 4 months, starting at birth, resulted at 7 months of age in a significant increase in the incidence of several lesions, including alveolar and bronchial epithelial hyperplasias, microadenomas, adenomas and malignant tumors in the lungs of mice of both genders. Multiplicity of adenomas and malignant tumors was also significantly increased in MCS-exposed mice.

Table II.

Preneoplastic and neoplastic alterations in the respiratory tract of Swiss H mice, as related to exposure to MCS and treatment with chemopreventive agents

| Treatment | Gender (no. of mice) | Alveolar epithelial hyperplasia | Bronchial epithelial hyperplasia | Microadenomas | Adenomas | Malignant tumors | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence | Multiplicity | Incidence | Multiplicity | |||||

| Sham | M (35) | 1 (2.9%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.9%) | 0.03±0.03 | 0 | 0 |

| F (28) | 2 (7.1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| M + F (63) | 3 (4.8%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.6%) | 0.02±0.02 | 0 | 0 | |

| MCS | M (34) | 10 (29.4%)a | 6 (17.6%)a | 9 (26.5%)a | 11 (32.4%)a | 1.2±0.39a | 5 (14.7%)b | 0.7±0.36b |

| F (38) | 13 (34.2%)a | 8 (21.1%)a | 6 (15.8%)b | 8 (21.1%)a | 1.6±0.55b | 5 (13.2%)b | 0.8±0.39 | |

| M + F (72) | 21 (29.2%)c | 14 (19.4%)c | 15 (20.8%)c | 19 (26.4%)c | 1.4±0.34c | 10 (13.9%)a | 0.7±0.26a | |

| MCS + MYO | M (31) | 11 (35.5%)c | 6 (19.4%)a | 7 (22.6%)a | 12 (38.7%)c | 2.4±0.68c | 2 (6.5%) | 0.2±0.14 |

| F (37) | 12 (32.4%)a | 5 (13.5%)b | 6 (16.2%)b | 11 (29.7%)a | 2.4±0.65a | 3 (8.1%) | 0.2±0.11 | |

| M + F (68) | 23 (33.8%)c | 11 (16.2%)c | 13 (19.1%)c | 23 (33.8%)c | 2.4±0.47c | 5 (7.4%)b | 0.2±0.09 | |

| MCS + VOR | M (33) | 10 (30.3%)a | 7 (21.2%)a | 3 (9.1%) | 13 (39.4%)c | 2.2±0.59c | 6 (18.2%)a | 0.7±0.35b |

| F (35) | 14 (40.0%)a | 8 (22.9%)a | 4 (11.2%) | 12 (34.3%)c | 2.2±0.59c | 6 (17.1%)b | 0.9±0.41b | |

| M + F (68) | 24 (35.3%)c | 15 (22.1%)c | 7 (10.3%)a | 25 (36.8%)c | 2.2±0.41c | 12 (17.6%)c | 0.8±0.27a | |

| MCS + PIO | M (33) | 8 (24.2%)a | 8 (24.2%)a | 8 (24.2%)a | 15 (45.5%)c | 3.7±0.80c,d | 8 (24.2%)a | 1.5±0.52a |

| F (34) | 11 (32.4%)a | 5 (14.7%)b | 7 (20.6%)a | 13 (38.2%)c | 2.7±0.69c | 7 (20.5%)a | 0.4±0.18b | |

| M + F (67) | 19 (28.4%)c | 13 (19.4%)c | 15 (22.4%)c | 28 (41.8%)c | 3.5±0.54c,d | 15 (22.4%)c | 0.9±0.28a | |

| MCS + BEX | M (34) | 7 (20.6%)b | 6 (17.6%)a | 10 (29.4%)c | 10 (29.4%)a | 1.3±0.51a | 5 (14.7%)a | 0.7±0.35b |

| F (36) | 8 (22.2%) | 7 (19.4%)a | 11 (30.6%)a | 11 (30.5%)a | 1.0±0.41b | 6 (16.7%)b | 0.7±0.35 | |

| M + F (70) | 15 (21.4%)a | 13 (18.6%)c | 21 (30.0%)c | 21 (30.0%)c | 1.2±0.32c | 11 (15.7%)a | 0.7±0.25a | |

| MCS + BEX + PIO | M (31) | 13 (41.9%)c | 5 (16.1%)a | 8 (25.8%)a | 13 (41.9%)c | 2.6±0.73c | 1 (3.2%) | 0.03±0.03 |

| F (34) | 15 (44.1%)a | 4 (11.8%) | 7 (20.6%)a | 10 (29.4%)a | 1.4±0.51c | 0e | 0 | |

| M + F (65) | 28 (43.1%)c | 9 (13.8%)a | 15 (23.1%)c | 23 (35.4%)c | 2.1±0.46c | 1 (1.5%)d | 0.02±0.02d | |

a P < 0.01 compared with sham of the same gender.

b P < 0.05 compared with sham of the same gender.

c P < 0.001 compared with sham of the same gender.

d P < 0.01 compared with MCS of the same gender.

e P < 0.05 compared with MCS of the same gender.

Of the five chemopreventive regimens, VOR decreased the MCS-related increase of incidence of microadenomas but had no significant effect on the yield of adenomas and malignant tumors. MYO decreased both incidence and multiplicity of malignant tumors. Although this effect was evident, it was close to statistical significance (P < 0.1) only for multiplicity in combined genders. BEX alone had no significant effect. PIO alone increased the yield of adenomas, an effect that reached the statistical significance threshold in males and combined genders. Combination of PIO and BEX inhibited the pulmonary tumorigenicity of PIO. In addition, this combination almost completely suppressed the ability of MCS to induce malignant tumors in the lung.

Discussion

The results of this study, performed under controlled experimental conditions, provide evidence for a solid correlation between early alterations of molecular biomarkers in the lung of MCS-exposed mice and induction of both systemic genotoxic damage and histopathological alterations in lung. Likewise, there was a substantial correlation between modulation of miRNA expression and proteome profiles by chemopreventive agents and protection toward genotoxic damage and lung tumors.

The observed ability of MCS to affect the pulmonary expression of miRNAs, especially in the sense of downregulation, agrees with the conclusions of previous studies (11,16–18). In fact, the 11.4% of the 694 miRNAs analyzed was downregulated by MCS. Interestingly, males and females responded in an opposite way to the MCS-induced dysregulation of miR-125b, a repressor of ErbB2. This oncogene is sensitive to estrogens and is involved in pulmonary carcinogenesis. Together with modulation of estrogen metabolism by CS in murine lung (19), this finding provides mechanistic support to the view that females are more susceptible than males to lung carcinogens, which in any case is still a controversial issue (1). Downregulation of miRNAs was accompanied by upregulation of the 5.7% of the 1164 proteins analyzed. These molecular signatures reflect both adaptive mechanisms and activation of pathways involved in the cancer process. Under comparable exposure conditions, in agreement with the results of previous studies (1,2), the mice exhibited both clastogenic damage in peripheral blood erythrocytes and a variety of histopathological alterations in mouse lung, also including both benign and malignant tumors.

The investigated chemopreventive agents have previously been assayed in mouse models of pulmonary carcinogenesis, mostly using A/J mice treated with typical CS components, such as benzo(a)pyrene, 4-(methylnitrosoamino)-1,3-pyridyl-1-butanone and vinyl carbamate. In particular, protective effects were observed with VOR (20,21), BEX (22–24) and PIO (25–27) although PIO promoted lung cancer progression and metastasis in immunocompetent mice (28). MYO inhibited the formation of pulmonary adenomas in mice treated with benzo(a)pyrene and 4-(methylnitrosoamino)-1,3-pyridyl-1-butanone (29,30) but failed to inhibit lung tumors in vinyl carbamate-treated mice (31). MYO was also tested successfully in combination with dexamethasone (29,32,33). Moreover, this combination was the only chemopreventive regimen that attenuated the weak carcinogenicity of environmental CS (33).

In this study, the drugs were less effective toward MCS as a complex mixture. BEX did not produce any significant effect. VOR reduced the incidence of microadenomas but not that of adenomas or malignant tumors, whereas MYO interfered with later carcinogenesis stages by affecting the yield of malignant lung tumors. On the other hand, PIO significantly enhanced the yield of pulmonary adenomas in MCS-exposed mice. In parallel, PIO enhanced the incidence of kidney lesions in the same mice, compared with mice exposed to MCS only (34). It is noteworthy that PPAR agonists have been reported to be tumorigenic in multiple sites of rodents and in the urothelial epithelium of monkeys (35,36). A recent meta-analysis of 17 studies showed a modest excess risk of bladder cancer in type 2 diabetes patients treated with PIO (37). These findings deserve attention because this drug is extensively used in diabetes patients and little time has elapsed since beginning its clinical use.

Luckily, the adverse effects of PIO both in the urinary tract (34) and in the lung (this study) of MCS-exposed mice were lost when this drug was combined with BEX. Indeed, this combined treatment was the most effective in reducing both the systemic clastogenicity of MCS and its ability to induce malignant tumors in the lung, which were almost totally prevented. Both RXRs and PPARs belong to the nuclear hormone superfamily and control the expression of multiple target genes. Interestingly, RXR is an obligate heterodymeric partner for PPARs (38,39), which suggests that not only tumorigenicity of PIO is suppressed when PPARγ is bound to RXR but even that this combination inhibits MCS-induced lung tumors.

The investigated drugs produced some dysregulation of baseline miRNA profiles and upregulation of a number of proteins in the lung of smoke-free mice. The identity of dysregulated mRNAs and proteins and their functions are reported and commented in Results and in Supplementary Results. As expected, BEX upregulated hRXR, and VOR downregulated the expression of histone deacetylase. The most remarkably upregulated protein was P25, a P53-dependent regulator of cell cycle, which is targeted by two miRNAs modulated by VOR, i.e. miR-106 and miR-302. Combination of PIO and BEX extensively downregulated the baseline expression of miRNAs and proteins, which may reflect some toxicity of these combined drugs. At the same time, however, this combination was by far the most efficient treatment in counteracting MCS-related miRNA and protein alterations.

In the interpretation of our data, it should be kept in mind that the molecular analyses were done on whole pulmonary tissue, and it is conceivable that both MCS and chemopreventive agents act differentially on the three major cell types found in any tissue, including adult organ-specific lung stem cells, the progenitor or transit-amplifying cells and the terminally differentiated cells. Therefore, our findings provide the net effect of the investigated agents on the mixed-cell population of the lung. It should be also taken into account that both genotoxic and epigenetic mechanisms are involved in the observed molecular alterations and that epigenetic events can even contribute to chromosome aberrations (40).

In conclusion, the results of this study highlight the close relationships between miRNAs, proteins, cytogenetic damage and lung tumors in MCS-exposed mice. In addition, these molecular biomarkers contribute substantially to the evaluation of both protective and adverse effects of cancer chemopreventive agents, either individually or in combination, and to the discovery of new precancer targets.

Supplementary material

Supplementary Table 1 and Results (SR 1–SR 5) can be found at http://carcin.oxfordjournals.org/

Funding

United States National Cancer Institute (Contract N01-CN 53301); Bulga rian Ministry of Education, Youth and Science (National Scie nce Foundation); Hasumi International Research Foundation (Bulgaria).

Conflict of Interest Statement: None declared.

Supplementary Material

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- BEX

bexarotene

- CS

cigarette smoke

- MCS

mainstream cigarette smoke

- miRNA

micro-RNA

- MYO

myo-inositol

- NCE

normochromatic erythrocytes

- PPARγ

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

- RXR

retinoid X receptor

- VOR

vorinostat.

References

- 1. Balansky R., et al. (2007). Potent carcinogenicity of cigarette smoke in mice exposed early in life. Carcinogenesis, 28, 2236–2243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Balansky R., et al. (2012). Differential carcinogenicity of cigarette smoke in mice exposed either transplacentally, early in life or in adulthood. Int. J. Cancer, 130, 1001–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. De Flora S., et al. (2012). Genomic and post-genomic effects of cigarette smoke: mechanisms and implications for risk assessment and prevention strategies. Int. J. Cancer, 131, 2721–2723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Balansky R., et al. (2010). Prevention of cigarette smoke-induced lung tumors in mice by budesonide, phenethyl isothiocyanate, and N-acetylcysteine. Int. J. Cancer, 126, 1047–1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Balansky R., et al. (2012). Inhibition of lung tumor development by berry extracts in mice exposed to cigarette smoke. Int. J. Cancer, 131, 1991–1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Balansky R., et al. (2009). Prenatal N-acetylcysteine prevents cigarette smoke-induced lung cancer in neonatal mice. Carcinogenesis, 30, 1398–1401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Balansky R., et al. (2012). Transplacental antioxidants inhibit lung tumors in mice exposed to cigarette smoke after birth: a novel preventative strategy? Curr. Cancer Drug Targets, 12, 164–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Izzotti A., et al. (2010). Chemoprevention of cigarette smoke-induced alterations of MicroRNA expression in rat lungs. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila)., 3, 62–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Izzotti A., et al. (2010). Modulation of microRNA expression by budesonide, phenethyl isothiocyanate and cigarette smoke in mouse liver and lung. Carcinogenesis, 31, 894–901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Izzotti A., et al. (2012). MicroRNAs as targets for dietary and pharmacological inhibitors of mutagenesis and carcinogenesis. Mutat. Res. Rev., 751, 287–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. De Flora S., et al. (2012). Smoke-induced microRNA and related proteome alterations. Modulation by chemopreventive agents. Int. J. Cancer, 131, 2763–2773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ogawa T., et al. (2005). Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid enhances gap junctional intercellular communication via acetylation of histone containing connexin 43 gene locus. Cancer Res., 65, 9771–9778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Marks P.A. (2007). Discovery and development of SAHA as an anticancer agent. Oncogene, 26, 1351–1356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zieleniak A., et al. (2008). Structure and physiological functions of the human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. (Warsz)., 56, 331–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wattenberg L.W., et al. (2000). Chemoprevention of pulmonary carcinogenesis by brief exposures to aerosolized budesonide or beclomethasone dipropionate and by the combination of aerosolized budesonide and dietary myo-inositol. Carcinogenesis, 21, 179–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Izzotti A., et al. (2009). Downregulation of microRNA expression in the lungs of rats exposed to cigarette smoke. FASEB J., 23, 806–812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Izzotti A., et al. (2009). Relationships of microRNA expression in mouse lung with age and exposure to cigarette smoke and light. FASEB J., 23, 3243–3250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Izzotti A., et al. (2011). Dose-responsiveness and persistence of microRNA expression alterations induced by cigarette smoke in mouse lung. Mutat. Res., 717, 9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Peng J., et al. (2013). Estrogen metabolism within the lung and its modulation by tobacco smoke. Carcinogenesis, 34, 909–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Casto B.C., et al. (2011). Prevention of mouse lung tumors by combinations of chemopreventive agents using concurrent and sequential administration. Anticancer Res., 31, 3279–3284 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tran K., et al. (2013). The combination of the histone deacetylase inhibitor vorinostat and synthetic triterpenoids reduces tumorigenesis in mouse models of cancer. Carcinogenesis, 34, 199–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pereira M.A., et al. (2006). Prevention of mouse lung tumors by targretin. Int. J. Cancer, 118, 2359–2362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang Y., et al. (2006). Organ-specific expression profiles of rat mammary gland, liver, and lung tissues treated with targretin, 9-cis retinoic acid, and 4-hydroxyphenylretinamide. Mol. Cancer Ther., 5, 1060–1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang Y., et al. (2009). Preventive effects of bexarotene and budesonide in a genetically engineered mouse model of small cell lung cancer. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila)., 2, 1059–1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang Y., et al. (2010). Chemopreventive effects of pioglitazone on chemically induced lung carcinogenesis in mice. Mol. Cancer Ther., 9, 3074–3082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fu H., et al. (2011). Chemoprevention of lung carcinogenesis by the combination of aerosolized budesonide and oral pioglitazone in A/J mice. Mol. Carcinog., 50, 913–921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li M.Y., et al. (2012). Pioglitazone prevents smoking carcinogen-induced lung tumor development in mice. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets, 12, 597–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li H., et al. (2011). Activation of PPARγ in myeloid cells promotes lung cancer progression and metastasis. PLoS One, 6, e28133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wattenberg L.W. (1999). Chemoprevention of pulmonary carcinogenesis by myo-inositol. Anticancer Res., 19, 3659–3661 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hecht S.S., et al. (2002). Inhibition of lung tumorigenesis in A/J mice by N-acetyl-S-(N-2-phenethylthiocarbamoyl)-L-cysteine and myo-inositol, individually and in combination. Carcinogenesis, 23, 1455–1461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gunning W.T., et al. (2000). Chemoprevention of vinyl carbamate-induced lung tumors in strain A mice. Exp. Lung Res., 26, 757–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang Z., et al. (2000). A germ-line p53 mutation accelerates pulmonary tumorigenesis: p53-independent efficacy of chemopreventive agents green tea or dexamethasone/myo-inositol and chemotherapeutic agents taxol or adriamycin. Cancer Res., 60, 901–907 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Witschi H. (2000). Successful and not so successful chemoprevention of tobacco smoke-induced lung tumors. Exp. Lung Res., 26, 743–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. La Maestra S., et al. (2013). DNA damage in exfoliated cells and histopathological alterations in the urinary tract of mice exposed to cigarette smoke and treated with chemopreventive agents. Carcinogenesis, 34, 183–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hardisty J.F., et al. (2008). Histopathology of the urinary bladders of cynomolgus monkeys treated with PPAR agonists. Toxicol. Pathol., 36, 769–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sato K., et al. (2011). Suppressive effects of acid-forming diet against the tumorigenic potential of pioglitazone hydrochloride in the urinary bladder of male rats. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol., 251, 234–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bosetti C., et al. (2013). Cancer risk for patients using thiazolidinediones for type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Oncologist, 18, 148–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ziouzenkova O., et al. (2008). Retinoid metabolism and nuclear receptor responses: New insights into coordinated regulation of the PPAR-RXR complex. FEBS Lett., 582, 32–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tachibana K., et al. (2008). The role of PPARs in cancer. PPAR Res., 102737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bradley M.O., et al. (1987). Relationships among cytotoxicity, lysosomal breakdown, chromosome aberrations, and DNA double-strand breaks. Mutat. Res., 189, 69–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.