Abstract

COL1A1

Osteogenesis imperfecta is a rare connective tissue disorder characterized by bone fragility and low bone density. Most cases are caused by an autosomal dominant mutation in either COL1A1 or COL1A2 gene encoding type I collagen. However, autosomal recessive forms have been identified. We present a patient with severe respiratory distress due to osteogenesis imperfecta simulating type II, born to a non-consanguineous couple with mixed African-American and African-Hispanic ethnicity. Cultured skin fibroblasts demonstrated compound heterozygosity for mutations in the LEPRE1 gene encoding prolyl 3-hydroxylase 1 confirming the diagnosis of autosomal recessive osteogenesis imperfecta type VIII, perinatal lethal type.

Keywords: autosomal recessive, LEPRE 1 gene, osteogenesis imperfecta, perinatal form, skeletal dysplasia

INTRODUCTION

Osteogenesis imperfecta is a rare group of heritable bone diseases characterized by propensity to spontaneous fractures, growth deficiency and in some subtypes, blue sclerae. Osteogenesis imperfecta is more commonly caused by an autosomal dominant (AD) mutation in the COL1A1 or COL1A2 gene, which encodes type I collagen (1). However, emerging research has demonstrated autosomal recessive (AR) mutations leading to osteogenesis imperfecta (2). These genes encode the cartilage-associated protein (CRTAP), prolyl 3 hydroxylase 1 (P3H1/LEPRE1) or cyclophilin B (encoded by PPIB). Together, these proteins help form the collagen prolyl 3-hydroxylation complex that facilitates modification of the α chains of type I collagen. According to the NCBI database, LEPRE1 is leucine proline-enriched proteoglycan (leprecan) 1 [Homo sapiens] (Gene ID: 64175). LEPRE1 has been found to be a founder mutation in 1.5% of asymptomatic individuals from West Africa and in 0.31–0.5% of asymptomatic African-Americans. We present the clinical, radiological and autopsy findings in a patient who was diagnosed in utero with short femora and bone fractures. Cultured fibroblasts from a skin biopsy disclosed two causative mutations in the LEPRE1 gene resulting in the lethal AR perinatal form of osteogenesis imperfecta.

CLINICAL HISTORY

The patient is the result of a first pregnancy to a non-consanguineous couple. The mother is of African-Colombian descent and the father is of African-American descent. There was good prenatal care and routine laboratory screens were all negative; however, the antenatal screening ultrasound study at 18 weeks gestation revealed short femora. Detailed ultrasound studies at 25 and 35 weeks gestation showed short extremities with bowing of the long bones including the radii, ulnae and femora as well as fractures of the femora. Other abnormalities included polyhydramnios, breech presentation and intrauterine growth restriction. The parents had declined an amniocentesis.

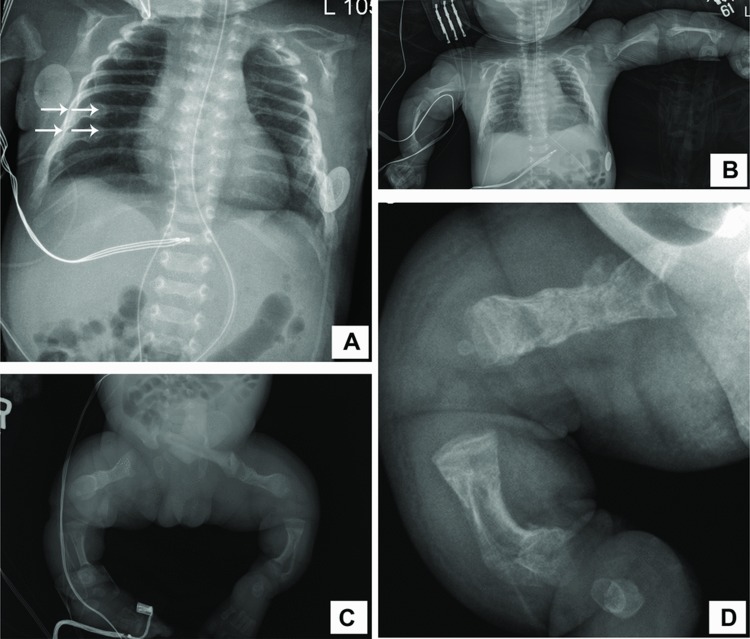

At 35 weeks gestation, the mother presented with preterm labor. Due to breech positioning and previous noted abnormalities, the female infant was delivered by emergency Cesarean section. APGAR (activity, pulse, grimace, appearance & respiration) scores were 2, 6 and 7 at 1, 5 and 10 min of life, respectively. Respiratory distress was evident soon after delivery and was managed by nasal continuous positive airway pressure (NCPAP) ventilation in the neonatal intensive care unit. Examination revealed a generally hypotonic and edematous infant with respiratory distress and short limbs in varus deformity. Sclerae were noted to be white. The birth weight was between 3rd and 10th percentile, head circumference just above 10th percentile and length grossly below 3rd percentile for gestational age. Initial radiographs (Figure 1) showed diffuse osteopenia with multiple bilateral healing fractures of the seventh and eighth ribs (arrows). There was symmetrical shortening of the humeri, radii, ulnae, femora, tibiae and fibulae and widening of the metaphyseal segments of all long bones. Healing fractures of the right proximal humerus and both femora were noted along with lateral bowing of the tibiae and fibulae. Differential diagnoses at this time included severe, perinatal osteogenesis imperfecta or campomelic dysplasia.

Figure 1. .

Composite photographs of her skeletal survey. (A) Chest radiograph on day 1 of life demonstrating demineralization of the bones and multiple healing rib fractures, including two each in the right and left seventh and eighth ribs (arrows). (B) Frontal view of the upper part of the body depicting shortening and demineralization of long bones, more recent fractures of both proximal humeri. (C) Frontal view of the lower limbs demonstrating demineralization with shortening and bowing of all of the long bones. The metaphyses also appear widened. There are healing fractures of the mid-shafts of both femora and both proximal tibiae. (D) Lateral view of the right femur at 10 days of age showing more fractures as evidenced by increasing areas of callus formation.

Early consultation with genetics, endocrinology and orthopedic specialties were pursued and the consensus was made for gentle handling, no casting and provision of adequate analgesia, chromosomal analysis and collagen mutation testing. By day 7 of life, the infant was weaned off NCPAP and oxygen supplementation and was tolerating enteral feeds administered via an orogastric tube. She required minimal morphine dosing. In the succeeding weeks, the infant experienced progressive respiratory deterioration. She was first noted to be desaturating frequently when handled despite preadministration and increased dosing of morphine. She then had to be re-placed on supplemental oxygen via nasal cannula on day 14 of life. Chest radiographs did not show any significant parenchymal abnormalities although lung expansion seemed consistently poor. There was gradually increasing inspiratory oxygen fraction (FiO2) requirement over the following week requiring re-placement on NCPAP ventilation. On day 29 of life, she went into severe respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation using a high-frequency oscillatory ventilator (HFOV). A C-reactive protein was elevated at 2.8 mg/dL with a relative neutropenia (WBC 4900/mm3) and increased bands of 23%. Empiric antibiotic treatment was initiated after blood and urine culture specimens were obtained. Lumbar puncture was deferred due to the increased risk of inducing fractures. Enterococcus faecalis was isolated in the blood culture and Klebsiella pneumoniae was isolated from the endotracheal tube culture. Antibiotic therapy was adjusted and continued for 21 days to cover for the possibility of meningitis. In the meantime, karyotype studies were reported as normal.

By day 36 of life, a week after being on mechanical ventilation, there was no clinical improvement. The infant continued with CO2 retention and borderline oxygen saturations despite maximal settings on the HFOV and an FiO2 of 1.0. A multidisciplinary meeting was held, including the palliative care team, social worker, neonatology and the patient's family. It was determined that if needed, chest compressions may be ineffective, detrimental and painful for the infant given her propensity for fractures. Respiratory support would continue but the patient would not receive escalation of care with vasopressors and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) if needed.

On day 48 of life, the infant was replaced on a conventional ventilator at high settings and switched to continuous fentanyl infusion for pain management. The results of DNA sequencing for COL1A1 and COL1A2 mutations in the patient's peripheral blood were reported as negative and a skin biopsy for further analysis was performed. She continued with frequent and deep desaturations and as per previous discussion with the family, in the event of bradycardia, resuscitation was to be limited to one dose of intravenous epinephrine. On day 54 of life, the patient developed bradycardia, which did not respond to intravenous epinephrine, and expired. The parents were informed of the events, counseled by the staff and gave consent for an autopsy.

AUTOPSY REPORT

The autopsy demonstrated the body of a female child with multiple skeletal dysplastic features, measuring 31.5 cm from crown to rump, 12.5 cm from rump to heel and weighing 3826 g. There was shortening and bowing of the upper and lower extremities (Figure 2), with both lower extremities having a varus deformity. The chest circumference was 38.5 cm and that of the abdomen was 33.5 cm. Periorbital edema was present. The sclerae were white. The soft tissues of the scalp were edematous resulting in a cephalic circumference of 36 cm (normal: 31.5 cm). The occipital region was flat. The anterior fontanelle was large, measuring 4.5 × 4 cm. The posterior fontanelle was 3 × 2 cm.

Figure 2. .

The patient's posterior view at autopsy demonstrating short and bowed upper and lower extremities. Notice redundant skin that seems excessive for the bone length.

Internal examination revealed pleural petechiae bilaterally. The lungs were congested and atelectatic. There was a 2.2 × 1.7 × 1.7 cm cystic mass with serous fluid located on one ovary and a similar cyst located on the other ovary, measuring 1.2 × 0.8 × 0.8 cm. The cranial posterior fossa was small.

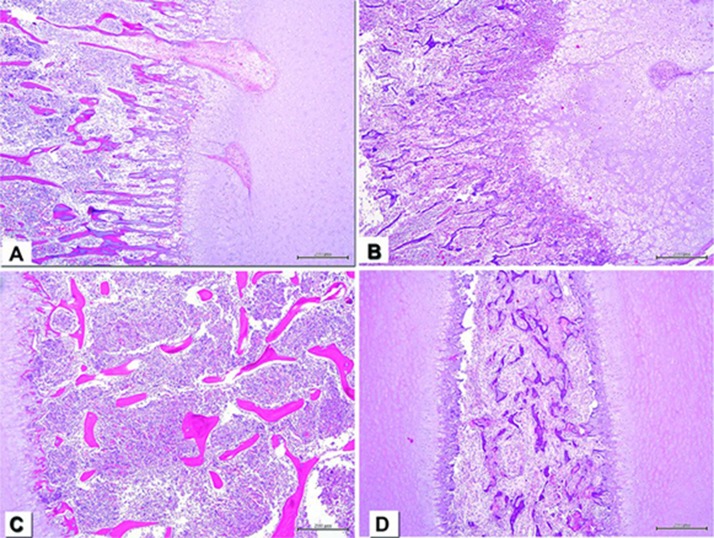

Microscopic examination of the ribs (Figure 3) demonstrated an irregular costochondral junction, thinning bony trabeculae and callous formation at the site of a healing fracture. The vertebral column disclosed a compressed vertebral body with expansion of the intervertebral disc as well as callous formation and thinning bony trabeculae. The liver showed centrilobular and sinusoidal congestion, microvesicular steatosis and hepatocellular atrophy. The lungs had collapsed parenchyma with congestion, numerous desquamated pneumocytes with intra-alveolar hemosiderin-laden macrophages, and patchy hyaline membranes. There was mucus and neutrophils located in the bronchi and bronchioli indicative of acute bronchopneumonia. The ovaries contained multiple follicular cysts.

Figure 3. .

Composite photomicrograph of bone histology. All slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Internal scale of 200 m at the left lower corners. (A) Age-matched control of costochondral junction demonstrating a well-demarcated straight line between the cartilage to the right and the bone to the left. The bone is properly mineralized. (B) Our patient's costochondral junction depicting an irregular demarcation between bone and cartilage. (C) Age-matched control-vertebral body. Notice the normal bone trabeculae and bone marrow. The vertebral body occupies almost the entire field of view, leaving a minimal portion of cartilage (intervertebral disc) to the left. (D) Compressed vertebral body from our patient (all the photographs were taken with the 4× lens). Depicts abnormally mineralized bone trabeculae and bone marrow fibrosis. There are two portions of intervertebral discs on both sides.

Fibroblast culture from a skin biopsy was sent to the Collagen Diagnostic Laboratory at the University of Washington, Seattle. Their report indicated heterozygosity for two causative mutations in the LEPRE1 gene, the gene that encodes P3H1, confirming the diagnosis of perinatal lethal osteogenesis imperfecta. No abnormalities were found in the gene sequencing analysis of COL1A1 and COL1A2, CRTAP or PPIB genes.

DISCUSSION

Osteogenesis imperfecta is a rare group of connective tissue disorders that increase the patient's susceptibility to multiple bone fractures. As a group, it has a prevalence of approximately 1 in every 20 000 births (3). There are currently 11 well-defined subtypes of osteogenesis imperfecta, mainly being separated by their genetic mutation and clinical presentation. Types I–IV are the classical Sillence types and are all AD with defects in either the COL1A1 or COL1A2 genes. Type V, which has a distinctive histology but unknown etiology, is also AD. Type VI is AR and is phenotypically characterized by a mineralization defect and distinctive histology. Types VII–IX are AR and are due to 3-hydroxylation defects, while types X and XI are also AR, but are secondary to chaperone defects (4).

Under the new classification, our patient is classified as having osteogenesis imperfecta type VIII. This is the perinatal severe to lethal form due to an AR mutation in the LEPRE1 gene, which encodes P3H1. The P3H1, along with CRTAP and cyclophilin B (CyPB), form the prolyl 3-hydroxylase complex in the endoplasmic reticulum. This complex is a part of the post-translational modification system of type I collagen (5). There are currently 17 known mutations of the LEPRE1 allele, occurring throughout the gene (6). Our patient had two causative mutations, presumptively on different alleles.

A very small proportion of Mid-Atlantic African-Americans (0.4%) are estimated to be carriers of the LEPRE1 mutation, resulting in recessive osteogenesis imperfecta in an estimated 1/260,000 births in that population. It is believed that the carriers were brought to the United States during the slave trade, as an estimated 1.5% of Ghanians and Nigerians are carriers (7). The parent's of our patient are both of African descent, with the mother being of African-Hispanic descent and the father of African-American descent.

This patient's phenotype differs from the classical severe AD perinatal form of osteogenesis imperfecta (type II) because even though our patient had intrauterine fractures, bone deformities and slight macrocephaly (spuriously increased because of scalp edema), she did not have blue sclerae, and she survived for 7 weeks in the neonatal intensive care unit. A phenotype similar to our patient has been previously described in type VIII osteogenesis imperfecta. The majority of the patients present with rhizomelia and fractures in the long bones and rib cage. The head circumference is usually normal, but the skull is poorly mineralized with enlarged fontanelle. The sclerae are also either white or light gray (6).

The mode of inheritance needs to be addressed for proper genetic counseling, as the perinatal severe forms tend to be de novo mutations without risk of recurrence; however, in severe AR inheritance the parents must be informed about the 25% risk of recurrence in every subsequent pregnancy.

While bisphosphonates, physical therapy and orthopedic surgery are mainstays in the treatment of the other types of osteogenesis, there is currently no effective treatment in patients with the perinatal lethal type. However, there are trials, mainly in animal models, that use pharmacologic targeting of stem cells to induce osteoblastic differentiation (8) and there is hope that the future generations of affected infants may benefit from pharmacogenomics.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

REFERENCES

- [1].Sykes B, Ogilvie D, Wordsworth P, et al. Consistent linkage of dominantly inherited osteogenesis imperfecta to the type I collagen loci: COL1A1 and COL1A2. Am J Hum Genet. 1990;46:293–307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Cabral WA, Chang W, Barnes AM, et al. Prolyl 3-hydroxylase 1 deficiency causes a recessive metabolic bone disorder resembling lethal/severe osteogenesis imperfecta. Nat Genet. 2007;39:359–365. doi: 10.1038/ng1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Marini JC. Osteogenesis imperfecta. Nelson textbook of pediatrics. In: Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jensen RM, editors. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders;; 2011. pp. 2437–2440. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Forlino A, Cabral WA, Barnes AM, Marini JC. New perspectives on osteogenesis imperfecta. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;;7:540–557. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Marini JC, Cabral WA, Barnes AM, Chang W. Components of the collagen prolyl 3-hydroxylation complex are crucial for normal bone development. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1675–1681. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.14.4474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Marini JC, Cabral WA, Barnes AM. Null mutations in LEPRE1 and CRTAP cause severe recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;339:59–70. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0872-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cabral WA, Barnes AM, Adeyemo A, et al. A founder mutation in LEPRE1 carried by 1.5% of West Africans and 0.4% of African Americans causes lethal recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Genet Med. 2012;14:543–551. doi: 10.1038/gim.2011.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gioia R, Panaroni C, Besio R, et al. Impaired osteoblastogenesis in a murine model of dominant osteogenesis imperfecta: a new target for osteogenesis imperfecta pharmacological therapy. Stem Cells. 2012;30:1465–1476. doi: 10.1002/stem.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]