Abstract

Background

Grandmothers living with grandchildren face stressors that may increase depressive symptoms, but cognitive-behavioral strategies, such as resourcefulness, may reduce the effects of stressors on mental health.

Purpose

This analysis examined the contemporaneous and longitudinal relationships among intra-family strain, resourcefulness and depressive symptoms in 240 grandmothers, classified by caregiving status to grandchildren.

Methods

Grandmothers raising grandchildren, grandmothers living in multigenerational homes, and non-caregivers to grandchildren reported on intra-family strain, resourcefulness, and depressive symptoms using mailed questionnaires at three time points over five years. Structural equation modeling was used to evaluate the mediating effects of resourcefulness and the relationships between variables.

Discussion

Grandmother caregiver status had significant effects on depressive symptoms and intra-family strain, but not resourcefulness. At all waves, higher resourcefulness was associated with fewer depressive symptoms, which reduced appraisals of intra-family strain.

Conclusions

Interventions focused on strengthening resourcefulness could reduce depressive symptoms over time.

Over the past two decades, attention to the roles that grandparents play in families has increased related to the rise in the numbers of grandparents raising grandchildren and the upsurge in multigenerational households. The 2000 United States census data estimates that 3.7 million grandmothers live in households that include grandchildren, and of these, at least 25% of the households do not include the parents of the grandchildren (Simmons & Dye, 2003). In contrast to grandmothers who play a supporting role to adult children and their families living in separate residences, grandmothers who live with grandchildren, with or without the children’s parents in the same home, face unique stressors that may impact their emotional well-being, particularly when such stressors are sustained. Grandmothers raising grandchildren report more stresses and depressive symptoms than their peers who are not doing so (Blustein, Chan, & Guanais, 2004; Fuller-Thomson & Minkler, 2001; Musil & Ahmad, 2002) and are therefore at risk for greater physical and psychological problems (Hayslip & Kaminski, 2005; Leder, Grinstead, & Torres, 2007; Zauszniewski, Au, & Musil, 2012). Grandmothers in multigenerational homes typically provide a home to adult children and grandchildren, either in a long-term multigenerational living arrangement, or for short-term help related to divorce, military deployment, or financial setbacks of their adult children—all situations that may contribute to substantial challenges within the family.

Theoretical models suggest that cognitive behavioral strategies for dealing with adversity, such as resourcefulness, can mitigate the effects of stress on psychological well-being (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Pearlin, Mullan, Semple & Skaff, 1990; Thoits, 1995; Zauszniewski, Eggenschwiller, Preechawong, Roberts, & Morris, 2006a; Zauszniewski, Lai, & Tithiphontumrong, 2006b). It is important to evaluate whether proposed meditating mechanisms, such as resourcefulness, operate as hypothesized in helping to reduce stress. Therefore, the purpose of this analysis was to examine the cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships between family stress (specifically intra-family strains), resourcefulness, and one indicator of psychological well-being, depressive symptoms, in a sample of grandmothers classified according to their caregiving status to grandchildren. Because there are no other longitudinal studies describing these relationships, this analysis offered a unique opportunity to examine such relationships, which could provide support for intervention work in the area of resourcefulness and caregiver well-being.

Background

A considerable body of literature has developed over the past 15 years examining grandmothers raising grandchildren and the effects of such arrangements on the grandmothers, and to a lesser extent, on the grandchildren. Grandmothers who assumed the caregiving role to grandchildren report many stressors and challenges in their role despite the rewards and gratifications of doing so (Emick & Hayslip, 1999; Hughes, Waite, LaPierre, & Luo, 2007; Lumpkin, 2007). Stress or stressors, in this context, refers to demands that invoke some cognitive, behavioral, or emotional coping efforts (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Thoits, 1995), and can include acute life events, ongoing strains, or daily hassles (Thoits, 1995); ongoing strains appear to have the greatest impact on depressive symptoms and psychological distress (Thoits, 2010). The primary focus of this analysis was the ongoing intra-family strains grandmothers face.

Grandmothers living with grandchildren have reported more intra-family strains, such as conflict among children, problems that don’t get resolved, or disagreements about a family member’s friend or activities than grandmothers who did not live with grandchildren (McCubbin, Thomson & McCubbin, 1996; Musil, Warner, Zauszniewski, Wykle, & Standing, 2009). Grandmothers raising grandchildren also reported more family legal and financial problems, while those living in multigenerational homes were more likely to report changes in family composition due to marriage, divorce, job loss, or other circumstances, especially among those in the adult child generation. These changes may complicate daily living situations, tax financial resources and interpersonal relationships, or contribute to depressive symptoms within the grandmother, in particular (Hayslip & Kaminski, 2005; Musil et al.). Intra-family strains associated with difficult family relationships and dynamics were particularly troubling for grandmothers who were often the “glue” of their family units and a stabilizing force for their grandchildren (Barnett, Mills-Koonce, Gustafsson, & Cox, 2012; Goodman, 2007; Standing et al., 2007). The mental well-being of these grandmother caregivers can have an impact on family well-being (Barnett, et al.; Hammen, Shih & Brennan, 2004; Musil, Warner, Zauszniewski, Jeanblanc, & Kercher, 2006).

Ongoing intra-family strain has been associated with more depressive symptoms (Musil et al., 2009). Numerous studies indicate that grandmothers raising grandchildren were likely to report more depressive symptoms than their peers who are not raising grandchildren (Fuller-Thomson & Minkler, 2001; Hayslip & Kaminski, 2005; Kelley, Whitley, Sipe, & Crofts-Yorker, 2000; Leder, Grinstead & Torres, 2007; Musil & Ahmad, 2002; Musil et al., 2011). Grandmothers living with grandchildren, especially if single, often reported elevated depressive symptoms regardless of whether there is an adult child in the home (Blustein et al., 2004).

Research in the area of grandparent caregiving has focused on factors such as social support and, to a lesser extent, coping, that could reduce the impact of stress, whether life events, hassles or strains, on mental health outcomes (Hayslip & Kaminski, 2005; Kelley, et al., 2000). For example, external social support reduced the effects of daily hassles on grandparenting stress and life satisfaction (Gerard, Landry-Myers, & Roe, 2006); of grandparental stressors on mental well-being (Sands, Goldberg-Glen, & Thornton, 2005); and of grandmother role stress on depressive symptoms (Musil & Ahmad, 2002). Surprisingly, much less attention has been given to coping strategies that could potentially improve psychological well-being in grandmother caregivers. The use of less avoidant coping mediated the relationship between greater grandmother role stress and depressive symptoms (Musil & Ahmad), and, in a different sample of grandmothers, resourcefulness mediated the relationship between intra-family strains and depressive symptoms (Musil et al., 2009).

Resourcefulness is a set of cognitive-behavioral skills for coping with adversity, such as cognitive reframing, problem-solving, and positive self-talk (Zauszniewski, 1997; Zauszniewski et al., 2006 a,b). Among those serving as caregivers to older adults, resourcefulness is related to better task performance, adaptive and social-role functioning, health behaviors, psychological well-being (Fingerman, Gallagher-Thompson, Lovett, & Rose, 1996; Gonzalez, 1997; Picot, Zauszniewski, & Delgado, 1997; Rapp, Schumaker, Schmidt, Naughton, & Anderson, 1998; Zauszniewski, 1996; Zauszniewski & Chung, 2001; Zauszniewski, Chung, & Krafcik, 2001) and to less caregiver burden (Intrieri & Rapp, 1994; Zauszniewski, 1997). Although grandmothers raising grandchildren report more depressive symptoms, they show no differences in resourcefulness (Musil et al., 2009) when compared with grandmothers living in multigenerational homes or who are non-caregivers to grandchildren.

Cross-sectional and intervention data about the relationship between resourcefulness and depressive symptoms suggests that it is a promising strategy for reducing the effects of stress on health, and thus warrants attention. Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies provide evidence to support the mediating effect of resourcefulness on the relationship between stress and depressive symptoms. Daily hassles and caregiving burden were found to affect resourcefulness and mental health in African American women (Zauszniewski, Picot, Roberts, Debanne, & Wykle, 2005; (Zauszniewski, Bekhet & Suresky, 2009). Resourcefulness mediated the effects of strain on depressive symptoms in grandmothers, regardless of their caregiving status to grandchildren (Musil et al., 2009) and in Chinese mothers during pregnancy and 6 weeks postpartum (Ngai & Chan, 2012). Findings from a recent pilot intervention trial with grandmothers raising grandchildren (Zauszniewski, et al., 2012) showed lower resourcefulness was associated with higher stress and more depressive symptoms prior to intervention, but that teaching resourcefulness skills to grandmothers reduced their stress and depressive symptoms over time (Zauszniewski, Musil & Au, 2013, in press). Thus, the research suggests that resourcefulness may be a potentially useful set of cognitive-behavioral strategies for women involved in caring for their grandchildren.

Across 24 months, grandmothers raising grandchildren and grandmothers in multigenerational homes continued to experience more intra-family strain than non-caregiver grandmothers. Transitions to greater caregiving responsibility, such as becoming a primary caregiver to a grandchild, were associated with increased intra-family strain. For depressive symptoms, grandmother caregiving group differences also remained, although levels of symptoms do not appear to change significantly over two years’ time. Grandmothers who are older, employed, married, or have more education are less depressed. Resourcefulness was shown to remain relatively stable over 24 months regardless of transitions in caregiving (Musil et al., 2011). There is limited data about the level of stability of intra-family strain, resourcefulness, or depressive symptoms over longer time periods, and whether the relationships between these variables, specifically the mediating effects of resourcefulness (Musil et al., 2009; Zauszniewski et al., 2006), are sustained at each time wave when considered within the context of longitudinal models.

Conceptual Model

The underlying conceptual framework for this study is Zauszniewski’s middle range theory of resourcefulness (Zauszniewski, 2005), which examines the relationships between contextual factors (grandmother caregiving status), process regulators (stress), resourcefulness (resourcefulness as concept), and quality of life (psychological well-being). According to this theory, stress (intra-family strain) affects psychological well-being (depressive symptoms) directly, and also indirectly, through resourcefulness. The contextual factor of grandmother caregiving status could affect stress, resourcefulness, and psychological well-being directly.

Intra-family strain, which reflects the grandmother’s perception of problems with family members and family interactions (McCubbin et al., 1996), has been shown to have a positive relationship with depressive symptoms (Musil et al., 2009; Zauszniewski et al., 2005). Therefore, we expected that greater intra-family strain would lead to increased depressive symptoms, but that greater resourcefulness would reduce depressive symptoms at each time point and over time. Further, since resourcefulness is thought to be relatively stable over time without efforts to improve it (Rosenbaum, 1990), and given the ongoing nature of strain, we expected relative stability of these variables over time. Therefore, based on prior work and theory, we hypothesized that we would find (a) relatively stable autocorrelations for each of the three variables across time, (b) paths from intra-family strain to increased depressive symptoms, with a mediating effect of resourcefulness at each time point, and (c) potential cross-lagged effects of intra-family strain on depressive symptoms and/or of resourcefulness on depressive symptoms (Thoits, 1995, 2010; Zauszniewski, et al., 2013). Establishing a mediating relationship between resourcefulness and depressive symptoms would provide a point of potential intervention to help older women/caregivers manage their psychological well-being.

Methods

Design

This analysis continued our report of findings from a longitudinal study about the health of grandmothers as caregivers to grandchildren. This analysis extended our prior cross-sectional analysis of intra-family strain, resourcefulness, and depressive symptoms (Musil et al., 2009) to a longitudinal model, and it extended our analysis of the stability of these variables from 2 years (Musil et al., 2011) to 4 to 4.5 years. Data were collected for a total of five time points from grandmothers once a year for 24 months, then extended for two more time points with data collection 2 to 2.5 years apart due to external funding, but here we only analyze data from the first, third and fourth time points. Our considerations in selecting these time points included maximizing both the sample size for analysis (cases eligible for analysis decrease with each time wave) and the length of the time frame under study, while providing relatively equivalent time intervals between waves (2 to 2.5 years). Further, given the theoretical and statistical complexity of the model, we restricted the number of time points to three waves (Lockhart, MacKinnon & Ohlrich, 2011). Based on theoretical modeling rooted in the extensive stress, coping and psychological well-being literature, we use structural equation modeling (SEM) to examine these relationships (Hair, Black, Babin & Anderson, 2009).

Study Sample

The study sample was drawn from an original sample of 485 Ohio grandmothers who participated in a longitudinal study of grandmothers as caregivers to grandchildren. At baseline, the grandmothers were categorized by their caregiving status to grandchildren age 16 or under: primary caregivers (n=183) who lived with one or more grandchildren without their parent(s) in the home; multigenerational grandmothers (n=135) whose household included at least one parent of a residential grandchild; or non-caregivers to grandchildren (n=167) who lived within a one hour drive of grandchildren and provided fewer than 20 hours per week of babysitting or childcare to them. We excluded grandmothers who provided extensive babysitting to maximize between group differences in caregiving responsibilities, particularly because those with heavy caregiving responsibilities had health effects similar to primary caregivers (Fuller-Thomson & Minkler, 2001). Grandmothers across the state of Ohio were recruited using random digit dialing (RDD) conducted by a university-affiliated survey research center, with supplemental convenience sampling of grandmothers raising grandchildren (Musil et al., 2006). Of the total sample, 75% were recruited through RDD and 25% by convenience methods. All of the non-caregiver grandmothers, 93% of multigenerational grandmothers, and 39% of primary caregivers were recruited through RDD. The baseline response rate of 73% was considered a good response rate for mailed surveys (Dillman, 2000).

Of the original sample of 485 grandmothers at T1, 435 participated 2 years after baseline (T2), and 369 continued 2 to 2.5 years after that, or 4 to 4.5 years after baseline (T3). Prior findings (Musil et al., 2011) indicate that switching to higher caregiving responsibility is associated with more perceived stress, intra-family strains, and problems in family functioning; therefore, we limited the sample to those who maintained a stable caregiving across all time waves in order to examine these relationships within a population who did not experience possible confounding effects from caregiving transitions. Thus, the sample of 240 grandmothers whose data were analyzed here participated in three waves of the study over approximately 4 to 4.5 years, with each wave 2 to 2.5 years apart, and they retained the same caregiving status to grandchildren across all waves of study participation.

Subject attrition (n=116) across waves was due to invalid contact information (n=36), deaths (n=29), unreturned questionnaires (n=27), refusals (n=15), and illness or nursing home (n=9), which reduced the T3 sample to 369. Of those 369 grandmothers, 5 of them did not return questionnaires at T2 and were excluded from analysis. Another 124 grandmothers who reported caregiving transitions over the 4 to 4.5 year span were excluded; these transitions were primary to multigenerational (n=4), primary to non-caregiver (n=22), multigenerational to primary (n=5), multigenerational to non-caregiver (n=50), non-caregiver to primary (n=7) and non-caregiver to multigenerational (n=9), with an additional 7 primary, 11 multigenerational and 9 non-caregivers who changed caregiving status during the 4 to 4.5 years but returned to their original status at T3. Such transitions are not uncommon, especially for those in multigenerational homes where adult children’s life circumstances can affect the grandmother’s involvement in the grandchild’s care (Standing, Musil, & Warner, 2007).

Measures

All measures were formatted for pencil and paper self-administration and were part of a larger questionnaire that examined stress and health of grandmothers and their caregiving to grandchildren. Only the instruments used to measure intra-family strain, resourcefulness and depressive symptoms are described here.

Intra-family strain was assessed with a 10- item composite scale of the intra-family strain subscale of the Family Inventory of Life Events (FILE) (McCubbin, et al., 1996). Respondents indicate whether, in the last 12 months, these problems or events occurred in their families, such as increased difficulty managing child(ren), increase in conflict between husband and wife, and increase in problems that don’t get resolved. Higher scores indicate more intra-family strain. This subscale shows discriminant validity between high and low conflict families (McCubbin et al., 1996), with reported α reliability of .72, which in this study ranged from α = .76 to .80 over time.

Depressive symptoms were measured using the 20-item CES-D scale (Radloff, 1977). Individuals were asked to evaluate how often over the past week (on a scale from 0, rarely, to 3, most or all of the time) they felt a certain way. Some examples include, were you bothered by things that don’t usually bother you, did you feel depressed, and did you enjoy life. Scores for individual items were summed into a composite item. The CES-D has had extensive validity testing, including validation with clinical diagnoses of depression in community samples (Radloff). The CES-D has excellent reported reliability (.88-.92), with study alphas ranging from .90 to .92 over time waves.

Resourcefulness was measured by a 25-item modified version of the Self-Control Schedule (SCS) (Rosenbaum, 1990; Zauszniewski, 1997) that was derived in a psychometric study by Zauszniewski (1997). This version is consistent with Rosenbaum’s conceptualization of resourcefulness, and correlated .97 with the 36-item version (Zauszniewski, 1997; Musil et al., 2009). On the SCS, participants indicate how well each item describes their behavior, ranging from (5) “Always like me” to (0) “Not at all like me.” Items include; “When an unpleasant thought is bothering me, I try to think about something pleasant,” and “I often find it difficult to overcome my feelings of nervousness and tension without outside help. Higher scores indicate higher resourcefulness. The alpha reliability of the 25-item instrument was .75 in community dwelling elders (Zauszniewski, 1997) and was .81-.82 over time in this sample. Evidence of construct validity for the measure has been reported (Zauszniewski, et al., 2006).

Grandmother caregiving status was based on self-report at each time point during a phone call preceding each data collection, and verified by questionnaire data about who else lives in the household, number of grandchildren living with the grandmother, and caregiving responsibility data for each grandchild, with follow-up phone clarification if needed in rare cases.

Data collection

At T1, participants were mailed a consent form, a questionnaire, and a stamped return envelope, followed by reminder postcards, and follow-up packets, according to our protocol developed based on the recommendations of Dillman (2000). At each time point, participants received telephone calls to update information and caregiving group status prior to our mailing of questionnaire packets. Participants received a gratuity of $15 at baseline and $25 at T2 and T3 upon questionnaire return. At each of the time points, grandmothers were categorized according to their highest level of caregiving responsibility to grandchildren.

Analysis

This analysis examined the relationships between intra-family strain, resourcefulness and depressive symptoms, and tested if the impact of intra-family strain on depressive symptoms is mediated by resourcefulness cross-sectionally and over time; it excluded demographic variables other than caregiving status to grandchildren. There are several approaches to analyzing longitudinal data, which include contemporaneous (all possible paths between variables within the same time wave), cross-lagged (all possible paths between variables from one time wave to the next future wave), and combined cross-lagged and contemporaneous structural equation models (Lockhart et al., 2011). All models were developed based on the theoretical framework, as suggested by Hair et al. (2009). In modeling relationships between variables, the purpose is to identify the most parsimonious model; with this in mind, statistically not significant paths were removed from each starting model, and, in addition, paths were added based on modification indices, if consistent with theory (for example, backward paths from T3 to T1 would not be added) (Hair, et al.).

The first step was to test each of the univariate, autoregressive (single variable) models for resourcefulness, intra-family strain and depressive symptoms to identify if the data fit an autoregressive format. Each model included two dummy variables representing grandmother caregiver group (primary vs. else and multigenerational vs. else). These autoregressive models provided stable building blocks for the more complex multivariate autoregressive model, as suggested by Joreskog (1993). Next, in order to evaluate the mediating effect of resourcefulness, we combined the three autoregressive models and planned to test 1) the cross-lagged model with all possible cross-lagged paths from one time point to the subsequent time points (e.g., regression paths going from T1 depressive symptoms to T2 resourcefulness; from T1 resourcefulness to T2 depressive symptoms, and so on); 2) the contemporaneous model with all possible contemporaneous effects (within the same time period) between variables at T2 or at T3 (e.g., regression paths of T2 depressive symptoms to T2 resourcefulness and T2 resourcefulness on T2 depressive symptoms, and so on); and 3) a combined contemporaneous and cross-lagged model. All paths were tested simultaneously, with paths sequentially added or removed, one path at a time, based on modification indices or non-significance, respectively, while remaining consistent with the theoretical model. Models were evaluated using goodness of fit indices: the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI >.90, ideally reaching .95), Comparative Fit Index (CFI> 90, ideally .95), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA <.08, ideally .05). The best-fitting model was to be used as the final model.

Results

The analysis sample included 107 primary caregivers raising grandchildren without parents in the home, 24 grandmothers in multigenerational homes, and 109 non-caregivers to grandchildren. The mean age of the sample was 57.5 years, although the grandmothers raising grandchildren were significantly younger than grandmothers in the other two groups (55.3 v. 59.3 years). Across the groups, 46% were employed, 58.8% were married, 70.4% were white, and 87% had completed high school. There was a higher proportion of women of color in the primary caregiver group. Demographic data by group is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Factors of Grandmothers by Caregiving Group N=240

| Primary | Multi-generational | Non-caregiver | Test Statistics | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| n = 107 | n =24 | n = 109 | |||

|

| |||||

| Age wave 1 | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 55.3 (7.9) | 58.9 (10.7) | 59.3 (8.8) | F = 6.3 | p <.01 |

|

| |||||

| Race | |||||

| White | 66 (61.7%) | 18 (75%) | 85 (78%) | χ2 = 7.15 | p= .03 |

| Non-White | 41 (38.3%) | 6 (25%) | 24 (22%) | ||

| AA | 34 | 6 | 22 | ||

| AI/AN | 1 | ||||

| Multiple | 5 | 2 | |||

| Not listed | 1 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married | 60 (56.1%) | 10 (41.7%) | 71 (65%) | χ2 = 5.04 | p= .08 |

| Not Married | 47 (43.9%) | 14 (58.3%) | 38 (35%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Education | |||||

| < HS | 17 (15.9%) | 2 (8.3%) | 11(10%) | χ2 = 2.03 | p= .36 |

| ≥HS missing | 90 (84.1%) | 22 (91.7%) | 97(89%) | ||

| 1(1%) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Employment | |||||

| Employed | 46 (21.9%) | 8 (33.3%) | 57 (52.3%) | χ2 = 3.7 | p= .16 |

| Not Employed | 61 (57%) | 16 (66.7%) | 52 (47.7%) | ||

Means and standard deviations for all study variables, by group, at each time point are presented in Table 2. Bivariate correlations between the study variables are presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations of Main Study Variables and ANOVA test results

| Primary n= 107 |

Multi n=24 |

Non Caregiver n = 109 |

F-test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intra-family Strain | ||||

| T1 | 4.5 (2.8) | 2.2(2.3) | 2.8 (2.4) | 15.92*** |

| T2 | 4.3 (2.8) | 2.5 (2.3) | 2.5 (2.5) | 13.15*** |

| T3 | 4.2 (2.8) | 3.8 (3.7) | 2.8 (2.6) | 6.62** |

| Resourcefulness | ||||

| T1 | 3.2 (0.7) | 3.1(0.8) | 3.3 (0.6) | 0.67 |

| T2 | 3.3 (0.6) | 3.1 (0.6) | 3.4 (0.6) | 2.28 |

| T3 | 3.2 (0.6) | 3.1 (0.7) | 3.3 (0.6) | 2.27 |

| Depression | ||||

| T1 | 15.4 (10.7) | 10.8 (9.6) | 11.1 (10.4) | 5.21** |

| T2 | 15.0 (11.1) | 10.0 (8.2) | 11.8 (10.9) | 3.50* |

| T3 | 14.6 (11.1) | 11.7 (7.9) | 11.5 (10.7) | 2.41 |

p < 0.05 level.

p < 0.01 level.

p <.001 level.

Table 3.

Correlations between Study Variables

| Study variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Primary | - | ||||||||||

| 2. Multigenerational | -.30** | - | |||||||||

| 3. T1 Intra family strain | .34** | -.17* | - | ||||||||

| 4. T2 intra family strain | .32** | -.10 | .55** | - | |||||||

| 5. T3 intra family strain | .21** | .03 | .47** | .49** | - | ||||||

| 6. T1 Resourcefulness | -.03 | -.07 | -.14* | -.18** | -.11 | - | |||||

| 7. T2 Resourcefulness | -.07 | -.11 | -.12 | -.23** | -.14* | .70** | - | ||||

| 8. T3 Resourcefulness | -.04 | -.11 | -.16* | -.28** | -.18** | .58** | .60** | - | |||

| 9. T1 CES-D | .21** | -.07 | .49** | .39** | .30** | -.28** | -.25** | -.28** | - | ||

| 10. T2 CES-D | .16* | -.10 | .38** | .43** | .30** | -.29** | -.33** | -.25** | .68** | - | |

| 11. T3 CES-D | .14* | -.04 | .39** | .35** | .39** | -.29** | -.28** | -.32** | .71** | .66** | - |

p < 0.01 level.

p < 0.05 level.

Model testing results

The data fit a contemporaneous model well. For the cross-lagged model, poor goodness of fit statistics across model iterations (CFI <.85) indicated that the data did not fit a cross-lagged format. Modification indices from the contemporaneous model did not support the use of cross-lagged effects, and we did not continue to develop the combined cross-lagged and contemporaneous model. Therefore, we present data from the autoregressive, contemporaneous analysis as the best fitting model.

Contemporaneous model

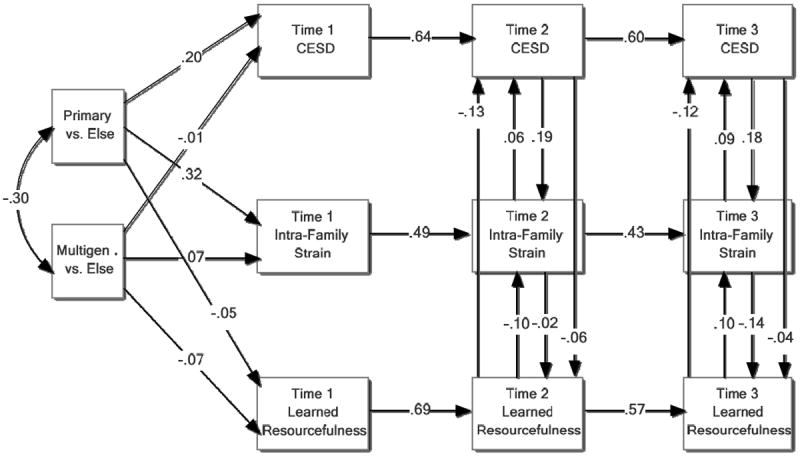

The contemporaneous model was developed over 15 steps, and incorporated the three autoregressive models. The baseline autoregressive model with all contemporaneous paths is shown in Figure 1, although contemporaneous paths at Time 1 are not modeled as a matter of statistical control (Lockhart, et al., 2011). Strong autocorrelations exist across the three waves for each of the models; for example, the correlations between the CES-D time waves are .64 and .60. Caregiver status indicators (dummy coded as primary v. else and multigenerational v. else) are inversely correlated. The paths from primary caregiver status to CES-D depressive symptoms are of medium effect, whereas the path to resourcefulness is not significant. Paths from multigenerational status are not significant, but are retained in the model due to coding for caregiver status. At Times 2 and 3, modest paths are shown from resourcefulness to depressive symptoms, from depressive symptoms to intra-family strain, and from intra-family strain to resourcefulness, and the other paths are not significant. Subsequently, paths were added or eliminated, one at a time, based on modification indices or non-significant paths, as shown in Table 4, which supplies goodness of fit statistics for each sequential step.

Figure 1.

Baseline autoregressive contemporaneous model showing standardized regression weights

Table 4.

Goodness of Fit statistics for each model step: Contemporaneous Autoregressive Model

| Model | Chi-Square | df | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Initial Model | 186.86 | 30 | .70 | .84 | .148 |

| 2 | Add covariance: CES-D 1 to CES-D 3 | 133.63 | 29 | .80 | .89 | .123 |

| 3 | Remove path: Intra-family 2 to Resourcefulness 2 | 133.73 | 30 | .80 | .89 | .121 |

| 4 | Remove path: Groups to Resourcefulness 1 | 135.06 | 32 | .82 | .89 | .116 |

| 5 | Remove path: Intra-family 2 to CES-D 2 | 135.76 | 33 | .82 | .89 | .114 |

| 6 | Remove path: Resourcefulness 3 to CES-D 3 | 136.68 | 34 | .83 | .89 | .112 |

| 7 | Remove path: Resourcefulness 3 to Intra-family 3 | 137.70 | 35 | .83 | .89 | .111 |

| 8 | Remove path: Intra-family 3 to Resourcefulness 3 | 138.49 | 36 | .84 | .89 | .110 |

| 9 | Remove path: CES-D 2 to Resourcefulness 2 | 139.92 | 37 | .84 | .89 | .108 |

| 10 | Remove path: Intra-family 3 to CES-D 3 | 142.20 | 38 | .84 | .89 | .107 |

| 11 | Remove path: Resourcefulness 2 to Intra-family 2 | 145.50 | 39 | .85 | .89 | .107 |

| 12 | Add path: CES-D 1 to Intra-family 1 | 90.52 | 38 | .92 | .95 | .076 |

| 13 | Add path: Resourcefulness 1 to CES-D 1 | 81.35 | 37 | .93 | .95 | .071 |

| 14 | Add Covariance: Intra-family 1 to Intra-family 3 | 66.53 | 36 | .95 | .97 | .060 |

| 15 | Remove paths: Resourcefulness 1,2 to CES-D 1.2 and CES-D3 to Resourcefulness 3 Correlate: Resourcefulness and CES-D all time points |

73.87 | 36 | .94 | .96 | .066 |

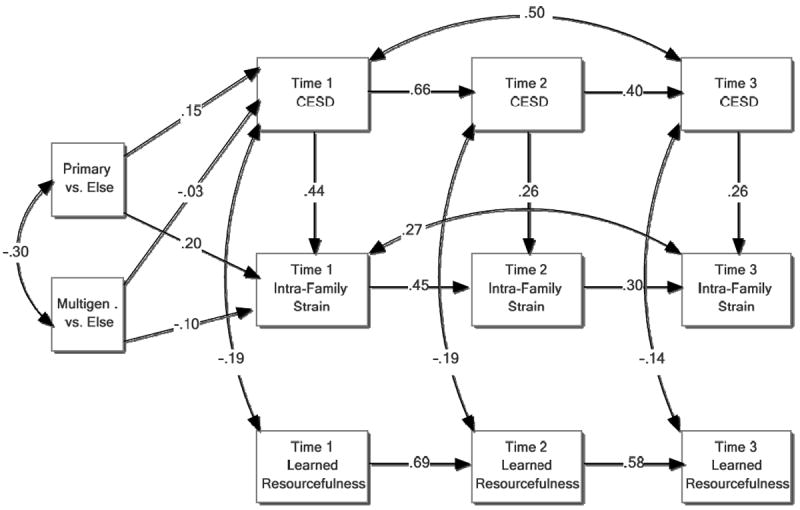

At Model 14, Chi-square 65.97, df. 36, p<.002. TLI =.95, CFI =.97, and RMSEA=.06, primary caregiving status affected depressive symptoms and intra-family strain. Consistent with earlier models, but contrary to expectation, depressive symptoms affected intra-family strain at each time point. Further, the paths between resourcefulness to depressive symptoms at Times 1 and 2 were as expected, but at Time 3, the path was opposite in direction, flowing from depressive symptoms to resourcefulness. In the interest of parsimony, we removed the directional paths between these two variables and inserted correlated paths between depressive symptoms and resourcefulness at each time point instead, yielding a good fitting model (Model 15, Figure 2), with Chi-square 73.33, d.f = 36, p<.000. TLI =.94, CFI =.96, and RMSEA=.07. In the final model, primary caregiver status predicted higher levels of depressive symptoms and intra-family strain; depressive symptoms contributed to perceptions of intra-family strain; and the relationship between depressive symptoms and resourcefulness was determined to be correlational rather than causal in nature (See Tables 5 & 6).

Figure 2.

Final autoregressive contemporaneous model showing standardized regression weights and correlations.

Table 5.

Maximum Likelihood Estimates-Final Model Structural Relationship Parameters

| Model Parameters | Unstandardized Regression Weights | Standardized Regression Weights | SE | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary → CES-D 1 | 3.089 | .148 | 1.180 | .009 |

| Multi → CES-D 1 | -1.097 | -.032 | 1.95 | .574 |

| CES-D 1 → CES-D 2 | .680 | .662 | .057 | *** |

| Primary → Intra-family 1 | 1.086 | .201 | .301 | *** |

| Multi → Intra-family 1 | -.852 | -.095 | .494 | .085 |

| CES-D 1 → Intra-family 1 | .113 | .436 | .014 | *** |

| Resourcefulness 1 → Resourcefulness 2 | .624 | .691 | .041 | *** |

| CES-D 2 → CES-D 3 | .391 | .395 | .057 | *** |

| Intra-family 1 → Intra-family 2 | .461 | .453 | .056 | *** |

| CES-D 2 → Intra-family 2 | .067 | .261 | .014 | *** |

| Intra-family 2 → Intra-family 3 | .319 | .305 | .064 | *** |

| CES-D 3 → Intra-family 3 | .072 | .261 | .015 | *** |

| Resourcefulness 2 → Resourcefulness 3 | .597 | .581 | .053 | *** |

p<.001

Table 6.

Maximum Likelihood Estimates-Final Model Covariances

| Model Parameters | Covariance Estimates | Correlation Estimates | SE | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary <---> Multi | -.045 | -.295 | .010 | *** |

| CES-D 1 to Resourcefulness 1 | -1.246 | -.192 | .374 | *** |

| CES-D 1 to CES-D 3 | 42.666 | .495 | 7.231 | *** |

| CES-D 2 to Resourcefulness 2 | -.626 | -.190 | .217 | .004 |

| CES-D 3 to Resourcefulness 3 | -.580 | -.144 | .228 | .011 |

| Intra-family 1 to Intra-family 3 | 1.473 | .266 | .401 | *** |

p<.001

Discussion

This analysis contributes to the literature on the psychological well-being of older women, especially grandmothers. It is the first study to examine the cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships between family stress, specifically intra-family strains, resourcefulness and depressive symptoms, and contributes to literature in the areas of stress and grandmother caregiving. The most innovative aspect of this study is the longitudinal examination of resourcefulness as a mediator in the relationship between intra-family strain and depressive symptoms in grandmothers as caregivers to grandchildren.

Grandmother caregiver status had significant effects on depressive symptoms and intra-family strain. Grandmothers who were continuous primary caregivers to grandchildren reported more depressive symptoms and intra-family strain than grandmothers who lived apart from their grandchildren or in multi-generational homes. This finding was consistent with most literature regarding the social and psychological well-being of grandmothers providing extensive care to grandchildren in comparison to their non-caregiving counterparts (Fuller-Thomson & Minkler, 2001). Szinovacz and Davey (2006), in contrast, found that grandmothers who provided over 800 hours of out of home care to grandchildren each year had fewer depressive symptoms than grandmothers currently or previously living with grandchildren (they did not distinguish between primary v. multigenerational arrangements) or than grandmothers providing less than 800 hours of babysitting for grandchildren. The effects of multigenerational status on intra-family strain and depressive symptoms were negligible, and are in contrast to prior cross-sectional findings about living with adult children and grandchildren (Musil et al., 2009), although Goodman (2007) found that most multigenerational families demonstrate relatively effective functioning.

We deliberately restricted this analysis to grandmothers who had consistent caregiving status with grandchildren in an effort to avoid the variability in stress that accompanies increasing or changing caregiving responsibility with grandchildren. Both strain and depressive symptoms were affected by primary caregiver status, reflecting the complex family situations that grandmothers raising grandchildren experience. We considered whether grandmother caregiving status could affect the longitudinal model as a whole, and in additional analysis not presented here, examined moderating effects of primary v. non-caregiver status, but did not find evidence of buffering effects for the set of inter-related variables. This suggests that the circumstances of grandchild caregiving affect stress and outcomes, rather than modifying the relationships between variables.

Grandmother caregiver status did not affect resourcefulness, which indicates that it might be a generalized cognitive-behavioral skillset. At each time wave, higher resourcefulness correlated with fewer depressive symptoms, but fewer depressive symptoms contributed to appraisals of less family strain; in other words, depressive symptoms affected how grandmothers appraised their family situations. According to Zauszniewski’s theory (2005), we had expected that strain would affect resourcefulness and depressive symptoms, and that resourcefulness would function as a mediator and reduce the effects of strain on depressive symptoms. In preliminary analysis using pairs of autoregressive models, resourcefulness reduced depressive symptoms at each time point, but when strain was included, the paths did not consistently reflect effects from resourcefulness to depressive symptoms. Whether paths between resourcefulness and depressive symptoms are causal or correlational seem to be influenced by intra-family strain, so additional research is needed to verify these relationships. However, it is important to consider the time sequencing of variables in any cross-sectional or longitudinal analyses (Lockhart, et al., 2011), and lack of clear cross-sectional sequence could affect findings of a contemporaneous mediating effect. However, for the longitudinal models that showed no cross-lagged effects, perhaps the strength of the autoregressive effects of resourcefulness and depressive symtpoms overshadowed any longitudinal cross-variable relationships.

Findings reveal new information about the stability of family strain, resourcefulness, and depressive symptoms over nearly a 5-year period. Intra-family strain was moderately correlated across time waves (.30-.45). Similarly, depressive symptoms showed strong autocorrelations (.40-.66) and resourcefulness showed even stronger continuity between time waves (.58-.69). These high autocorrelations might impact the mediational tests because the bivariate correlations were considerably reduced when incorporated within the longitudinal multivariate context. However, the sustained levels of intra-family strain and depressive symptoms among grandmothers warrants attention from care providers and policy makers who deal with grandparent caregiving and child welfare.

The correlation between depressive symptoms and resourcefulness is supported by other studies of women caregivers, including studies of grandmothers in the caregiving role. However, the finding that this correlation is consistent over time is interesting in light of Rosenbaum’s theory of resourcefulness, which suggests that resourcefulness skills, while generally stable, can be learned informally over time in response to adverse situations (Rosenbaum, 1990). Thus, one might question why grandmothers did not learn to be more resourceful over time in managing their daily caregiving responsibilities, and instead, consistently maintained a steady level of depressive symptoms over time. It is possible that their depressive symptoms posed a barrier to the sort of informal self-study Rosenbaum anticipated, suggesting that grandmothers may benefit from a structured, tailored intervention that teaches resourcefulness skills.

In a recent pilot clinical trial, 88% of the grandmothers reported a need for resourcefulness training 4-months after receiving it, and 92% of them reported that they believed other grandmothers like them need resourcefulness training (Zauszniewski et al., 2012). This finding and the results of other psycho-educational and social intervention studies suggest the need for ongoing, consistent, and reinforced skills’ training to improve psychological well-being symptoms. Targeted strategies for grandmothers providing care to their grandchildren are essential; this sub-group of the older population is at-risk and could benefit from resourcefulness training to specifically manage family issues and depressive symptoms.

The contemporaneous causal effect of depressive symptoms on intra-family strain implies that individuals suffering from depressive symptoms are more likely to have a negative outlook regarding life events, and thus be disposed to cite problems with intra-family strain, as their own mental health could affect their ability to interact and intervene proactively with their own families (Barnett, et al., 2012; Hammen, et al., 2004). Perhaps, chronic depressive symptoms are the lens through which some women who are raising grandchildren perceive intra-family strain, and as such, mental health assessment and intervention could have psychological benefits for them and improve intra-family relationships. These clinical implications highlight the need for brief assessments of grandmother caregivers when they or their grandchildren seek health care.

With an expanding number of households classified as “grandfamilies,” it is of growing urgency that we develop a better understanding of the family dynamics of multigenerational and grandparent-headed households. This paper provides information about the longitudinal effects of caregiving to grandchildren and about the relationships between depressive symptoms and resourcefulness relative to grandmother caregivers’ coping with intra-family strain. Future intervention research may help to clarify the short and long-term effects of resourcefulness training and other interventions that may augment grandmothers’ efforts to manage their own and their families’ well-being.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NR005067-10 Intergenerational Caregiving to Youth at-risk and Grandmothers, Caregiving, Families and Transitions

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barnett MA, Mills-Koonce WR, Gustafsson H, Cox M. Mother-Grandmother Conflict, Negative Parenting, and Young Children’s Social Development in Multigenerational Families. Family Relations. 2012;61(5):864–877. doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2012.00731.x. [Google Scholar]

- Blustein J, Chan S, Guanais FC. Elevated depressive symptoms among caregiving grandparents. Health Services Research. 2004;39(6):1671–1689. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00312.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillman D. Mail and internet surveys: The tailored design. 2. New York: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Emick MA, Hayslip B. Custodial grandparenting: Stresses, coping skills and relationships with grandchildren. International Journal of Aging & Human Development. 1999;48(1):35–61. doi: 10.2190/1FH2-AHWT-1Q3J-PC1K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, Gallagher-Thompson D, Lovett S, Rose J. Internal resourcefulness, task demands, coping, and dysphoric affect among caregivers of the frail elderly. International Journal of Aging & Human Development. 1996;42(3):229–248. doi: 10.2190/UHJB-CA5L-2K03-3BNV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Thomson E, Minkler M. American grandparents providing extensive child care to their grandchildren: Prevalence and profile. Gerontologist. 2001;41(2):201–209. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerard JM, Landry-Meyer L, Roe JG. Grandparents raising grandchildren: The role of social support in coping with caregiving challenges. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2006;62(4):359–383. doi: 10.2190/3796-DMB2-546Q-Y4AQ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez EW. Resourcefulness, appraisals, and coping efforts of family caregivers. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 1997;8(3):209–227. doi: 10.3109/01612849709012490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman CC. Family dynamics in three-generation families. Journal of Family Issues. 2007;29(3):355–379. [Google Scholar]

- Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. Multivariate Data Analysis 7th Ed. Prentice Hall; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Shih JH, Brennan PA. Intergenerational Transmission of Depression: Test of an Interpersonal Stress Model in a Community Sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(3):511–522. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayslip B, Kaminski PL. Grandparents raising their grandchildren: a review of the literature and suggestions for practice. The Gerontologist. 2005;45(2):262–9. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes ME, Waite LJ, LaPierre TA, Luo Y. All in the family: the impact of caring for grandchildren on grandparents’ health. Journal of Gerontology B: Psychological & Social Sciences. 2007;62(2):S108–19. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.2.s108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intrieri RC, Rapp SR. Self-control skillfulness and caregiver burden among help-seeking elders. Journals of Gerontology. 1994;49(1):19–23. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.1.p19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joreskog K, Sorbom D. LISREL 8* Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMLES Command Language. Scientific Software; Lincolnwood, IL: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley S, Whitley D, Sipe T, Crofts Yorker B. Psychological distress in grandmother kinship care providers: The role of resources, social support, and physical health. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2000;24(3):311–321. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley SJ, Whitley D, Sipe TA. Results of an interdisciplinary intervention to improve the psychosocial well-being and physical functioning of African American grandmothers raising grandchildren. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships. 2007;5(3):45–64. doi: 10.1300/J194v05n03_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley SJ, Whitley DM, Campos PE. Grandmothers raising grandchildren: Results of an intervention to improve health outcomes. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2010;42(4):379–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2010.01371.x.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal and Coping. Springer; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Leder S, Grinstead LN, Torres E. Grandparents raising grandchildren: Stressors, social support and health outcomes. Journal of Family Nursing. 2007;13(3):333–352. doi: 10.1177/1074840707303841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart G, MacKinnon D, Ohlrich V. Mediation analysis in psychosomatic medicine research. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2011;73(1):29–43. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318200a54b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumpkin JR. Grandparents in a parental or near-parental role. Journal of Family Issues. 2008;29(3):357–372. [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin HI, Thompson AI, McCubbin M. Family assessment: Resiliency, coping and adaptation: Inventories for research and practice. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin System; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Musil C, Ahmad M. Health of grandmothers: a comparison by caregiver status. Journal of Aging and Health. 2002;14(1):96–121. doi: 10.1177/089826430201400106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musil CM, Gordon NL, Warner CB, Zauszniewski JA, Standing T, Wykle ML. Grandmothers and Caregiving to Grandchildren: Continuity, Change, and Outcomes Over 24 Months. The Gerontologist. 2011;51(1):86–100. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musil C, Warner C, Zauszniewski J, Jeanblanc A, Kercher K. Grandmothers, caregiving, and family functioning. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2006;61:S89–S98. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.2.s89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musil C, Warner C, Zauszniewski J, Wykle M, Standing T. Grandmother caregiving, family stress and strain and depressive symptoms. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2009;31(3):389–408. doi: 10.1177/0193945908328262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngai FW, Chan SW. Learned resourcefulness, social support, and perinatal depression in Chinese mothers. Nursing Research. 2012;61(1):78–85. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e318240dd3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist. 1990;30(5):583–94. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picot S, Zauszniewski J, Delgado C. Cardiovascular responses of African American female caregivers. Journal of the Black Nurses’ Association. 1997;9(1):3–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rapp SR, Shumaker S, Schmidt S, Naughton M, Anderson R. Social resourcefulness: its relationship to social support and wellbeing among caregivers of dementia victims. Aging and Mental Health. 1998;2(1):40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum M. The role of learned resourcefulness in self-control of health behavior. In: Rosenbaum M, editor. Learned resourcefulness: On coping skills, self-control, and adaptive behavior. New York: Springer; 1990. pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sands RG, Goldberg-Glen R, Thornton PA. Factors Associated with the Positive Well-Being of Grandparents Caring for Their Grandchildren. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2005;45(4):65–82. doi: 10.1300/J083v45n04_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons T, Dye JL. Grandparents living with grandchildren: 2000. U. S. Census Bureau (Census Bureau Publication No. C2KBR-31); Washington, DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Standing T, Musil C, Warner C. Grandmother’s Transitions in Caregiving to Grandchildren. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2007;29:613–631. doi: 10.1177/0193945906298607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szinovacz ME, Davey A. Effects of retirement and grandchild care on depressive symptoms. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2006;62(1):1–20. doi: 10.2190/8Q46-GJX4-M2VM-W60V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Stress, coping and social support processes: Where are we? What’s next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;35:53–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51(S):S41–53. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zauszniewski JA. Self-help and help-seeking behavior patterns in healthy elders. Journal of Holistic Nursing. 1996;14(3):223–226. doi: 10.1177/089801019601400305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zauszniewski JA. Evaluation of a measure of learned resourcefulness for elders. Journal of Nursing Measurement. 1997;5(1):71–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zauszniewski JA. Resourcefulness. In: Fitzpatrick JJ, Wallace M, editors. Encyclopedia of Nursing Research. New York: Springer Publishing; 2005. pp. 256–258. [Google Scholar]

- Zauszniewski JA, Au TY, Musil CM. Resourcefulness training for grandmothers raising grandchildren: Is there a need? Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2012;33(10):680–686. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2012.684424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zauszniewski JA, Bekhet AK, Suresky MJ. Relationships among perceived burden, depressive cognitions, resourcefulness, and quality of life in female relatives of seriously mentally ill adults. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2009;30(3):142–150. doi: 10.1080/01612840802557204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zauszniewski JA, Chung C. Resourcefulness and health practices of diabetic women. Research in Nursing and Health. 2001;24(2):113–121. doi: 10.1002/nur.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zauszniewski JA, Chung C, Krafcik K. Social cognitive factors predicting the health of elders. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2001;23(5):490–503. doi: 10.1177/01939450122045339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zauszniewski JA, Eggenschwiler K, Preechawong S, Roberts BL, Morris DL. Effects of teaching resourcefulness skills to elders. Aging and Mental Health. 2006a;10(4):404–12. doi: 10.1080/13607860600638446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zauszniewski JA, Lai C, Tithiphontumrong S. Development and testing of the Resourcefulness Scale for older adults. Journal of Nursing Measurement. 2006b;14(1):57–68. doi: 10.1891/jnum.14.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zauszniewski JA, Musil CM, Au TY. Resourcefulness training for grandmothers raising grandchildren: Acceptability and feasibility of two methods. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2013 doi: 10.3109/01612840.2012.684424. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zauszniewski JA, Picot SJ, Roberts BL, Debanne SM, Wykle ML. Predictors of resourcefulness in African American women. Journal of Aging Health. 2005;17(5):609–33. doi: 10.1177/0898264305279871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]