Abstract

Objective

Eosinophil predominant inflammation characterises histological features of eosinophilic oesophagitis (EoE). Endoscopy with biopsy is currently the only method to assess oesophageal mucosal inflammation in EoE. We hypothesised that measurements of luminal eosinophil-derived proteins would correlate with oesophageal mucosal inflammation in children with EoE.

Design

The Enterotest diagnostic device was used to develop an oesophageal string test (EST) as a minimally invasive clinical device. EST samples and oesophageal mucosal biopsies were obtained from children undergoing upper endoscopy for clinically defined indications. Eosinophil-derived proteins including eosinophil secondary granule proteins (major basic protein-1, eosinophil-derived neurotoxin, eosinophil cationic protein, eosinophil peroxidase) and Charcot–Leyden crystal protein/galectin-10 were measured by ELISA in luminal effluents eluted from ESTs and extracts of mucosal biopsies.

Results

ESTs were performed in 41 children with active EoE (n=14), EoE in remission (n=8), gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (n=4) and controls with normal oesophagus (n=15). EST measurement of eosinophil-derived protein biomarkers significantly distinguished between children with active EoE, treated EoE in remission, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and normal oesophagus. Levels of luminal eosinophil-derived proteins in EST samples significantly correlated with peak and mean oesophageal eosinophils/high power field (HPF), eosinophil peroxidase indices and levels of the same eosinophil-derived proteins in extracts of oesophageal biopsies.

Conclusions

The presence of eosinophil-derived proteins in luminal secretions is reflective of mucosal inflammation in children with EoE. The EST is a novel, minimally invasive device for measuring oesophageal eosinophilic inflammation in children with EoE.

Keywords: Eosinophil, pediatric, enterotest string test, oesophagitis, inflammation, epithelial barrier, gastrointestinal tract, oesophageal disease, oesophageal disorders, oesophageal lesions, oesophageal reflux, oesophageal strictures, allergy, breast milk, childhood nutrition

Significance of this study.

What is already known on this subject?

Eosinophilic oesophagitis (EoE) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterised by symptoms of oesophageal dysfunction and oesophageal mucosal eosinophilia.

Mucosal biopsy is required to make the diagnosis and, in some cases, monitor disease activity.

Serum and stool biomarkers have provided mixed results regarding disease activity in EoE.

What are the new findings?

-

▸

Oesophageal mucosal biopsy samples obtained from patients with active eosinophilic oesophagitis (EoE) contain increased quantities of eosinophil granule proteins.

-

▸

Quantities of eosinophil granule proteins in oesophageal luminal samples obtained with the oesophageal string test correlate with eosinophil counts and granule protein levels in oesophageal tissues.

-

▸

Intraluminal sampling of the oesophageal secretions can monitor histological inflammation in EoE.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

-

▸

The oesophageal string test might provide a valuable device to measure inflammation in patients with oesophagitis. The oesophageal string test may offer significant value in monitoring the impact of therapeutic interventions on oesophageal inflammation in patients with eosinophilic oesophagitis.

Background

Eosinophilic oesophagitis (EoE) is a chronic oesophageal disease characterised by a constellation of symptoms and eosinophil predominant inflammation of the oesophageal epithelium.1 2 A significant problem besetting the understanding of pathogenic mechanisms and the care of patients with EoE is the identification and capture of biomarkers of oesophageal inflammation. Except for enumeration of eosinophils in oesophageal biopsies, no validated measurements of oesophageal inflammation or disease activity have been identified. Previous studies suggest that measurements of eosinophils as well as extracellular eosinophil secondary granule protein (ESGP) deposition in the oesophageal mucosa may serve as valuable measures of disease activity in EoE.3–6

The ESGPs include four cationic proteins present in the eosinophil's large specific (secondary) granule known as major basic protein-1 (MBP1), eosinophil peroxidase (EPX), eosinophil-derived neurotoxin (EDN) and eosinophil cationic protein (ECP). A fifth protein, the Charcot–Leyden crystal protein/galectin-10 (CLC/Gal-10),7 is primarily a cytosolic protein, but is also present in the eosinophil's primary (coreless) granule.8 Each granule-associated protein carries different biochemical and functional properties relevant to proposed pathogenetic mechanisms for oesophageal dysfunction and remodelling in EoE.9–12 Thus, measurement of eosinophil-derived proteins, including ESGPs and CLC/Gal-10, within the oesophageal mucosal microenvironment could provide both clinically relevant information regarding EoE disease activity and novel pathophysiological mechanisms.

To date, the only methodology to assess mucosal inflammation in patients with EoE is endoscopy and mucosal biopsy. Correlation of symptoms with eosinophilic inflammation is variable and peripheral measurements of eosinophil-associated biomarkers from serum and stool have been of limited value13–15 in which some demonstrate significant correlation whereas others do not. As an alternative to endoscopy and mucosal biopsy and peripheral measures, we have used the proximal portion of the Enterotest device16 17 to measure luminal eosinophil-derived proteins and termed this section of the Enterotest the oesophageal string test (EST). We hypothesised that measurements of ESGPs and CLC/Gal10 directly in oesophageal luminal secretions would reflect mucosal inflammation in EoE.

Materials and methods

Enterotest description

The Enterotest (HDC Corporation, Pilpitas, CA, USA), a minimally invasive string-based technology composed of a capsule filled with approximately 90 cm of string, was originally designed to detect gastric and small intestine pathogens, sample bile and assess for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) (online supplementary figure S1A).17–19 In this study, one end of the string (∼10 cm) was pulled from the capsule and wound around the index finger (online supplementary figure S1B–D). The capsule was swallowed, the proximal string taped to the cheek (online supplementary figure S1E) and the remaining string in the capsule deployed to end in the duodenal lumen, where the capsule was dislodged.

We sampled luminal secretions from the proximal part of the Enterotest string and termed this the EST. Locations of oesophageal and gastric segments of the Enterotest were determined using pH indicator sticks (online supplementary figure S1F) supplied with tests, and if subjects were on antiacid medications, by measuring the length to the lower oesophageal sphincter at the time of endoscopy.

In vitro analysis of ESGPs and CLC/Gal-10 using the EST

See online supplementary methods.

Subject selection and Enterotest nylon string administration

Subjects between the ages of 7 and 20 years who were undergoing an endoscopy with biopsy at either the Children's Hospital Colorado, Aurora, Colorado, USA or Ann and Robert H Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA to determine the causes of abdominal pain, vomiting, growth failure, dysphagia or histological efficacy of EoE treatment were enrolled in this study. Exclusion criteria included a history of oesophageal stenosis (stricture or narrowing), gelatin allergy or other causes that put subjects at increased risk (bleeding diatheses, connective tissue diseases) of endoscopic complications. Histories were taken to record symptoms, allergic history, family history and medications. Review of endoscopic and pathology records were performed to assure diagnostic accuracy and determine clinical features.

Subject diagnoses were assigned according to the following criteria based on published consensus recommendations:1 2 (1) EoE-active: children with symptoms of oesophageal dysfunction and oesophageal eosinophilia >15 eosinophils/HPF, in whom other causes of symptoms and oesophageal eosinophilia were ruled out; (2) EoE-remission: children with EoE as defined above who had undergone at least 8 weeks of treatment (topical steroids or dietary elimination) and who, at the time of their endoscopy, were asymptomatic; (3) GORD: children with symptoms of vomiting or heartburn who had responded to proton pump inhibitor treatment and/or had an abnormal pH impedance monitor of the distal oesophagus. Subjects were on proton pump treatment at the time of the endoscopy; and (4) Normal: children with symptoms that lead to endoscopic testing who were found to have histologically normal oesophageal, gastric and duodenal mucosae.

The night before endoscopic procedures, subjects swallowed the Enterotest (online supplementary figure S1). Subjects could drink liquids until 3 h before their endoscopic procedure. If families or subjects desired, the subject was admitted to the Research Center (Clinical and Translational Research Center) at the Children's Hospital Colorado or Ann and Robert H Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago the night before the procedure.

The day after swallowing the Enterotests, subjects had upper endoscopy performed. After anaesthesia was administered, the Enterotest was removed, adherent secretions were eluted from the proximal oesophageal section of the Enterotest and the sample was immediately frozen for later batch analysis of the ESGPs and CLC/Gal-10. The oesophageal string location was determined as noted below (online supplementary figure S1F). Mucosal pinch biopsies were then taken from oesophageal mucosal surfaces and immediately snap frozen for eosinophil-derived protein extraction and measurement. Diagnostic biopsies were placed in neutral buffered formalin for processing and routine H&E (eosinophil enumeration) and immunohistochemical (EPX Staining Index) staining.

This study was approved by the Colorado Multi-institutional IRB (COMIRB) and IRBs of the University of Illinois at Chicago and the Children's Memorial Hospital.

Processing EST samples and biopsies for ESGPs and CLC/-10 biomarker assays

See online supplementary methods.

Quantitative measurement of ESGP and CLC/Gal-10 biomarkers

ESGP and CLC/Gal-10 levels present in EST samples and biopsy extracts were determined using commercial (EDN, ECP; MBL International, Woburn, MA, USA) or inhouse developed (MBP1, CLC/Gal-10, EPX) ELISAs. Assays for EDN and ECP were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Double-antibody sandwich ELISAs for MBP1 and CLC/Gal-10 were developed and standardised at the Ackerman laboratory (Chicago, IL, USA) and for EPX at the Lee laboratory (Scottsdale, AZ, USA). MBP1 and CLC/Gal-10 ELISAs used standard curves generated using the purified eosinophil-derived protein, prepared as previously described.7 20–22 For MBP1, mouse monoclonal antibodies were used for both capture and detection (mouse anti-human MBP1-clones, J14-8A2 and J13-6B6, respectively, kindly provided by Dr Hirohito Kita, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA), the detection antibody being biotinylated and detected using streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase (ExtraAvidin Peroxidase, E2886; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and FAST OPD Tablet substrate (P9187; Sigma-Aldrich). CLC/Gal-10 ELISAs used a mouse monoclonal capture antibody (Anti-human Gal-10/CLC, Cell Sciences, Canton, Massachusetts, USA), whereas the detection antibody was a CLC/Gal-10 affinity purified rabbit polyclonal antibody prepared as previously described.7 Detection antibodies for the MBP1 and CLC/Gal-10 ELISAs were biotinylated using a Biotin-XX Microscale Protein Labelling Kit (B30010; Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, Eugene, Oregon, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. MBP1 and CLC/Gal-10 ELISA assays detected these eosinophil-derived proteins in the ranges of 11.8–750 and 0.125–16 ng/ml, respectively, with recoveries of 80%–100% and 100%–120%, signal to noise ratios >5 and coefficient of variation (CV) of 15%.

Specific parameters and detailed protocol and methods associated with the EPX-based ELISA in mice have been recently described.23 EPX ELISA detected EPX in the range of 8–1024 ng/ml, with recovery of 90%, signal to noise ratios >15 and an assay CV of 13%.

Histological analysis

Eosinophils were enumerated in formalin-fixed, H&E stained tissue sections as previously described (KC, SS, JM, Denver; HM, Chicago).24 Eosinophils were defined as having at least one nuclear lobe identified in association with intracellular eosin stained granules. Only epithelial eosinophils were enumerated (surface area 0.26 mm2). Results were reported as peak (in one mucosal sample from most densely populated section) and mean eosinophils/HPF (from 5 HPFs counted). Analytical variability of histological assessment was <5% and discrepancies between investigators were resolved.

EPX immunohistochemistry and EPX scoring

Immunohistochemistry for EPX and determination of the EPX Staining Index score for proximal and distal oesophageal biopsies were performed in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections as previously described.6

Statistical analysis

SAS V.1 9.2 was used for statistical analysis. Biomarker levels were compared across groups using ANOVA. Since these outcome variables were not normally distributed, logarithmic transformation to the natural base was applied to the data, where the value of 0 in biomarker level was coded as 10−6. Spearman correlation coefficient (r) was used to assess the correlations between biomarkers. Fisher's z transformation was applied when testing statistical significance of r. C-statistics (ie, the area under receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve) were used to quantify the discriminating ability of a biomarker. C value>0.7 was considered acceptable discrimination. ROC was estimated from the logistic regression model with the level of biomarkers being a continuous predictor.

Results

Eosinophil-derived proteins bind to Enterotest nylon strings in vitro

As determined by western blot analyses, Enterotest strings detected a concentration dependent increase in MBP1 protein from eosinophil lysates (online supplementary figure S2); EPX and MBP1 were detected on Enterotest nylon strings as early as 1 h after incubation with lysates (online supplementary figure S3). Strings were also able to detect EPX and MBP1 from IL-5 activated intact eosinophils (online supplementary figure S4) as early as 1 h following incubations. Strings were also able to capture another eosinophil-derived protein, EDN, from activated eosinophils (1×106) (online supplementary figure S5). Together, these in vitro results supported the feasibility of using Enterotest nylon strings in situ to capture eosinophil-derived proteins.

Subject characterisation and tolerance of procedure

Forty-one subjects were recruited; no significant differences in recruitment were identified between the two sites. Clinical characteristics of these subjects are summarised in online supplementary table S1. No complications or endoscopic mucosal findings were identified that were related to the performance of Enterotests and a gagging sensation during swallowing the capsule was the only problem reported.

Mucosal biopsy concentrations of ESGPs and CLC/Gal-10 differentiate subjects with active EoE from those with treated EoE, GORD and normal subjects without inflammation

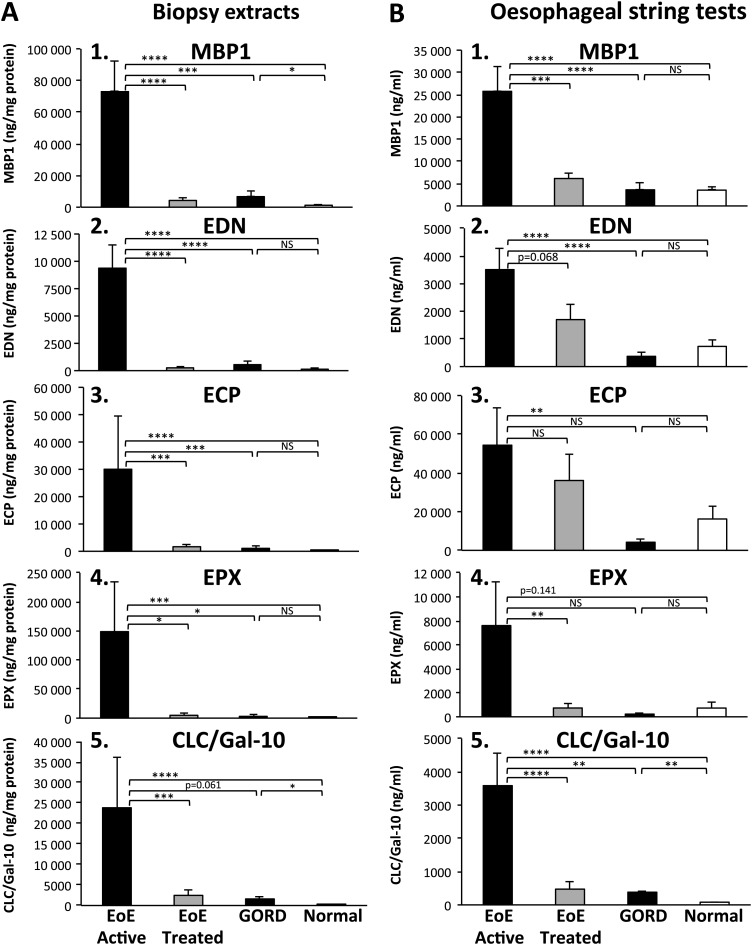

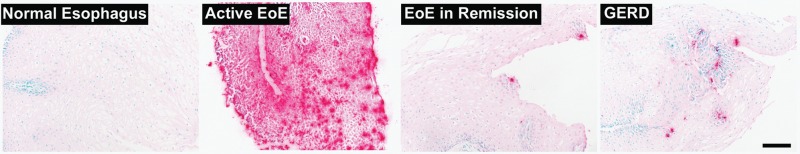

Eosinophil enumeration has been the ‘gold standard’ biomarker used for assessing mucosal inflammation. Thus, we first compared the number of mucosal eosinophils (enumeration and EPX Staining Index) with quantitative measurements of eosinophil-derived proteins in biopsy extracts. Consistent with previous studies, both eosinophil numbers and EPX Staining Indices were significantly greater in subjects with active EoE compared with EoE in remission, GORD and normal controls (table 1). Eosinophil-derived protein concentrations (figure 1; (A1) MBP1, (A2) EDN, (A3) ECP, (A4) EPX and (A5) CLC/Gal-10) in oesophageal biopsy extracts were significantly increased in subjects with active EoE compared with treated EoE (MBP1, p<0.0001; EDN, p<0.0001; ECP, p<0.001; EPX, p<0.05; CLC/Gal-10, p<0.001; active vs treated), GORD (MBP1, p<0.001; EDN, p<0.0001; ECP, p<0.001; EPX, p<0.05; active vs GORD) and to those with normal mucosa (MBP1, p<0.0001; EDN, p<0.0001; ECP, p<0.0001; EPX, p<0.001; CLC/Gal-10, p<0.0001 active vs normal).

Table 1.

Summary of histological and gross features of mucosal eosinophilia

| EoE-active (untreated), n=14 | EoE-remission (treated), n=8 | GORD, n=4 | Normal oesophagus, n=15 | p Values untreated EoE versus treated, GORD, normal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eosinophil peak count (±SEM) | |||||

| Proximal | 30.1±6.0 | 0.4±0.3 | 0.3±0.2 | 0 | p<0.001 |

| Distal | 45.4±8.9 | 0 | 0.8±0.4 | 0 | p<0.001 |

| Eosinophil average of five random fields (±SEM) | |||||

| Proximal | 17.4±3.9 | 0.1±0.1 | 0.3±0.2 | 0 | p<0.001 |

| Distal | 28.9±6.0 | 0 | 0.3±0.2 | 0 | p<0.001 |

| EPX Staining Index* | |||||

| Proximal | 34.2±5.3 | 4.4±2.3 | 0 | 2.8±2.8 | p<0.001 |

| Distal | 41.1±1.9 | 6.5±3.5 | 11.3±6.0 | 5.9±3.3 | p<0.001 |

| Endoscopic evidence of exudate (% of total patients) | 6 (43%) | 2 (25%) | 1 (25%) | 0 | p<0.001 |

| Microabscess† (% of total patients) | 11 (79%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | p<0.001 |

| Superficial layering‡ (% of total patients) | 9 (64%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | p<0.001 |

| |||||

Panels show representative images of immunohistochemical staining for EPX (red reaction product) in tissue sections from subjects with normal oesophagus, untreated EoE, treated EoE in remission and GORD that were used to generate the EPX Staining Index in this study.

Microabscess: four or more eosinophils adjacent to each other in the superficial epithelia.

Superficial layering: eosinophils within the luminal surface of the oesophageal epithelia.

EoE, eosinophilic oesophagitis; EPX, eosinophil peroxidase; GORD, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.

Figure 1.

Eosinophil-derived protein levels in oesophageal biopsy and oesophageal string test (EST) samples. Oesophageal mucosal biopsies concentrations of (A1) major basic protein-1 (MBP1), (A2) eosinophil-derived neurotoxin (EDN), (A3) eosinophil cationic protein (ECP), (A4) eosinophil peroxidase (EPX) and (A5) Charcot–Leyden crystal protein/galectin-10 (CLC/Gal-10). Eosinophil secondary granule proteins and CLC/Gal-10 as measured by ELISA are shown in samples from subject groups (eosinophilic oesophagitis (EoE) active—black bars, EoE treated—light gray bars, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD)—black bars, normal—white bars). Results are reported as ng of eosinophil protein per mg of total protein in the biopsy extract. EST concentrations of (B1) MBP1, (B2) EDN, (B3) ECP (B4) EPX and (B5) CLC/Gal-10 from the same subject groups are reported as ng of eosinophil protein per ml of EST supernatant. Biomarker levels were compared across groups using ANOVA. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, NS, not significant.

Next we wanted to determine whether mucosal biopsy concentrations of eosinophil-derived proteins correlated with traditional and newer measurements of eosinophil burden. All eosinophil-derived proteins tested correlated significantly with peak eosinophil counts, mean eosinophil counts and EPX Staining Indices measured in the above subject groups (p<0.0001 for all eosinophil proteins vs peak eosinophil, mean eosinophil and EPX Staining Index) (table 2A).

Table 2.

Correlations of eosinophil-derived protein concentrations from biopsy extracts and ESTs with histological measures of mucosal eosinophilia

| Peak eosinophils* | Mean eosinophils* | EPX Staining Index* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Biopsies | r Value† | p Value | r Value† | p Value | r Value† | p Value |

| MBP1 | 0.72559 | <0.0001 | 0.72003 | <0.0001 | 0.72052 | <0.0001 |

| EDN | 0.78673 | <0.0001 | 0.79306 | <0.0001 | 0.75952 | <0.0001 |

| ECP | 0.70621 | <0.0001 | 0.70804 | <0.0001 | 0.66968 | <0.0001 |

| EPX | 0.61117 | <0.0001 | 0.61596 | <0.0001 | 0.60103 | <0.0001 |

| CLC/Gal-10 | 0.66360 | <0.0001 | 0.66329 | <0.0001 | 0.65902 | <0.0001 |

| EPX Staining Index* |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. ESTs | r Value† | p Value | ||||

| MBP1 | 0.72170 | <0.0001 | ||||

| EDN | 0.47688 | <0.002 | ||||

| ECP | 0.20519 | NS | ||||

| EPX | 0.54145 | <0.0002 | ||||

| CLC/Gal-10 | 0.72735 | <0.0001 | ||||

n=41 subjects for peak and mean eosinophil numbers and EPX index.

Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (r) for values from n=41 subjects.

CLC/Gal-10, Charcot–Leyden crystal protein/galectin-10; ECP, eosinophil cationic protein; EDN, eosinophil-derived neurotoxin; EPX, eosinophil peroxidase; EST, oesophageal string test; MBP1, major basic protein-1.

Together, these results determined that mucosal biopsy concentrations of eosinophil-derived proteins, similar to eosinophil enumeration, serve as reliable measures of mucosal eosinophil burden. In addition, measurements of biopsy extracts were significantly different between disease states suggesting they were reflective of disease activity.

EST detection of ESGPs and CLC/Gal-10 differentiates subjects with active EoE from those with treated EoE, GORD and normal subjects without inflammation

To determine whether we could capture evidence of mucosal inflammation by using an intraluminal device, we next measured levels of luminal oesophageal eosinophil-derived proteins with ESTs in subjects with active EoE, treated EoE, GORD and normal oesophagus. Eosinophil-derived proteins (figure 1; (B1) MBP1, (B2) EDN, (B3) ECP, (B4) EPX and (B5) CLC/Gal-10) were significantly increased in EST samples obtained from subjects with active EoE compared with those with treated EoE (MBP1, p<0.001; EPX, p<0.01; CLC/Gal-10, p<0.0001; active vs treated), GORD (MBP1, p<0.0001; EDN, p<0.0001; CLC/Gal-10, p<0.01; active vs GORD) as well as subjects with no histopathological evidence of oesophageal inflammation (MBP1, p<0.0001; EDN, p<0.0001; ECP, p<0.01; CLC/Gal-10 p<0.0001; active vs normal).

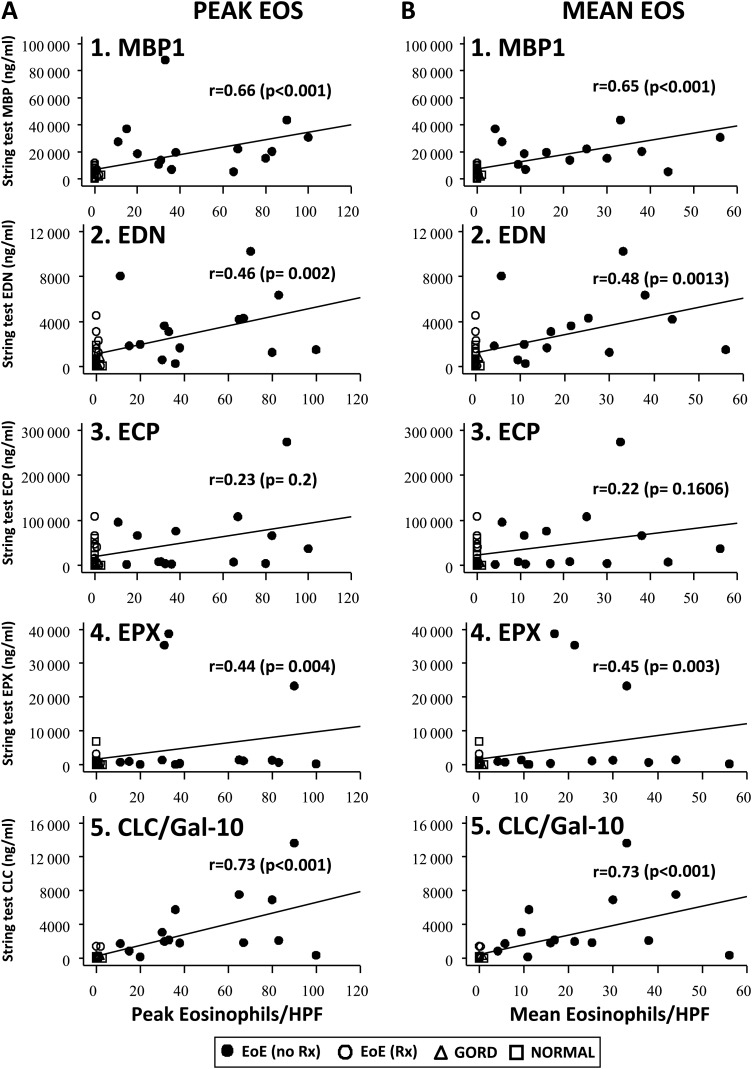

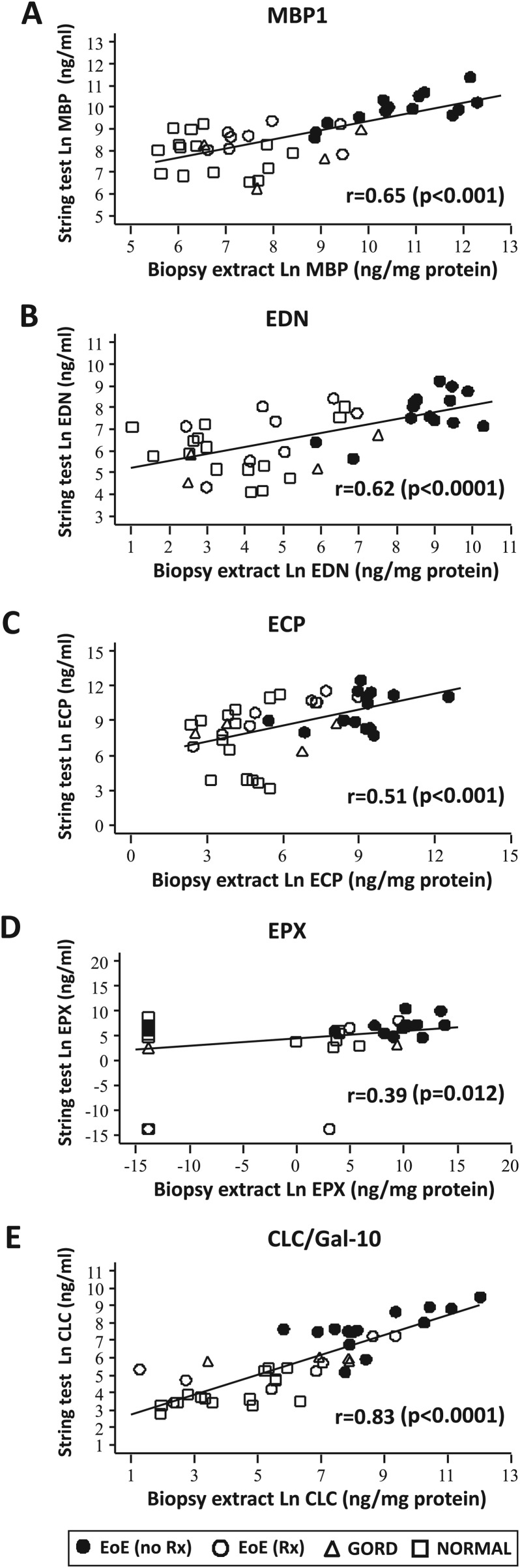

Luminal measurements of eosinophil-derived proteins correlate with tissue measurements of mucosal eosinophilic inflammation

To determine whether luminal concentrations of eosinophil-derived proteins were reflective of tissue measurements of eosinophil burdens, we performed correlational analyses of eosinophil-derived protein concentrations obtained with ESTs with three measures of eosinophilic inflammation present in the tissue: (1) traditional gold standard measurement1 2—eosinophil counts/HPF (peak and mean), (2) newer measurement6—EPX Staining Index and (3) newest measurement (this study)—eosinophil-derived protein levels in mucosal biopsy extracts determined by ELISA. Concentrations of MBP1, EDN, EPX and CLC/Gal-10 measured in EST samples obtained from all subjects correlated significantly with eosinophil counts (figure 2; A, peak eosinophils; B, mean eosinophils) and EPX indices (table 2B). In addition, EST assessments of all eosinophil-derived proteins correlated significantly with measures of the same biomarkers measured in extracts of matched mucosal biopsies (MBP1, p<0.001; EDN, p<0.0001; ECP, p<0.001; EPX, p<0.05 and CLC/Gal-10, p<0.0001) (figure 3). Together, these results demonstrated that capture of luminal eosinophil-derived biomarkers by ESTs provides an accurate reflection of oesophageal mucosal eosinophilic inflammation.

Figure 2.

Correlation of eosinophil-derived proteins in oesophageal string test samples with eosinophil counts in oesophageal mucosal biopsy samples. Spearman analyses correlating oesophageal string test sample eosinophil-derived protein levels with peak (panel A, 1–5) and mean (panel B, 1–5) eosinophil counts were performed. Spearman rank correlation coefficients (r) and associated p values are shown. EoE-no Rx (untreated—active disease) (solid circles), EoE-Rx (treated—in remission) (open circles), GORD (open triangles) and normal oesophagus (open squares). CLC/Gal-10, Charcot–Leyden crystal protein/galectin-10; ECP, eosinophil cationic protein; EDN, eosinophil-derived neurotoxin; EoE, eosinophilic oesophagitis; EPX, eosinophil peroxidase; GORD, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease; MBP1, major basic protein-1.

Figure 3.

Correlation of eosinophil-derived protein concentrations in luminal oesophageal string test (EST) samples with eosinophil-derived proteins in oesophageal mucosal biopsy samples. (A) major basic protein-1 (MBP1), (B) eosinophil-derived neurotoxin (EDN), (C) eosinophil cationic protein (ECP), (D) eosinophil peroxidase (EPX) and (E) Charcot–Leyden crystal protein/galectin-10 (CLC/Gal-10) concentrations in EST and mucosal biopsy extracts were correlated using Spearman analyses (rank correlation coefficients (r) and associated p values). Eosinophilic oesophagitis (EoE)-no Rx (untreated—active disease) (solid circles), EoE-Rx (treated—in remission) (open circles), gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) (open triangles) and normal oesophagus (open squares).

ESTs can detect eosinophilic inflammation without evidence of superficial inflammation

We next determined whether evidence of superficial mucosal inflammation was necessary to detect luminal inflammation with the EST. Of the 14 active EoE subjects, white exudates, microabscess or superficial layering were seen in all but four subjects despite each having detectable eosinophil-derived protein levels in either their biopsy or EST samples. Except for one condition, ECP versus microabscess (table 3, values in bold), no significant correlations were identified between gross or histological measurements of oesophageal mucosal inflammation with respect to eosinophil-derived protein concentrations measured in mucosal biopsies.

Table 3.

ESTs can detect eosinophilic inflammation without evidence of superficial inflammation

| Sample source | White exudate (8 without vs 6 with) p value* | Superficial layering (9 without vs 5 with) p value* | Microabscess (9 without vs 5 with) p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBP1 | Biopsies | 0.6354 | 0.4457 | 0.0817 |

| ESTs | 0.4921 | 0.0325 | 0.0430 | |

| EDN | Biopsies | 0.0681 | 0.2850 | 0.2137 |

| ESTs | 0.3718 | 0.2475 | 0.5314 | |

| ECP | Biopsies | 0.1573 | 0.1342 | 0.0384 |

| ESTs | 0.0507 | 0.7435 | 0.8338 | |

| EPX | Biopsies | 0.1445 | 0.5722 | 0.7302 |

| ESTs | 0.5830 | 0.2279 | 0.3776 | |

| CLC/Gal-10 | Biopsies | 0.7754 | 0.6341 | 0.4833 |

| ESTs | 0.6070 | 0.2490 | 0.2881 |

Active EoE subjects (14) with or without evidence of superficial mucosal inflammation (noted in parentheses in table) were compared with each other for each of the eosinophil-derived proteins from each sample source (biopsy or EST).

From two sample t tests comparing subjects with versus those without a particular endoscopic/histological condition. Statistically significant values (p<0.05) are in bold.

CLC/Gal-10, Charcot–Leyden crystal protein/galectin-10; ECP, eosinophil cationic protein; EDN, eosinophil-derived neurotoxin; EoE, eosinophilic oesophagitis; EPX, eosinophil peroxidase; EST, oesophageal string test; MBP1, major basic protein-1.

No significant correlations were identified between gross measurements (white exudate) of oesophageal mucosal inflammation with respect to eosinophil-derived protein concentrations measured from biopsy or EST samples (table 3). Except for two conditions, MBP1 versus superficial layering and microabscess (table 3, values in bold), no significant correlations were detected when comparing histological evidence of superficial epithelial inflammation (eosinophil microabscess and superficial layering) with eosinophil-derived protein concentrations measured from ESTs. These results suggest that ESTs can capture eosinophilic inflammation even if there is no evidence of superficial mucosal inflammation.

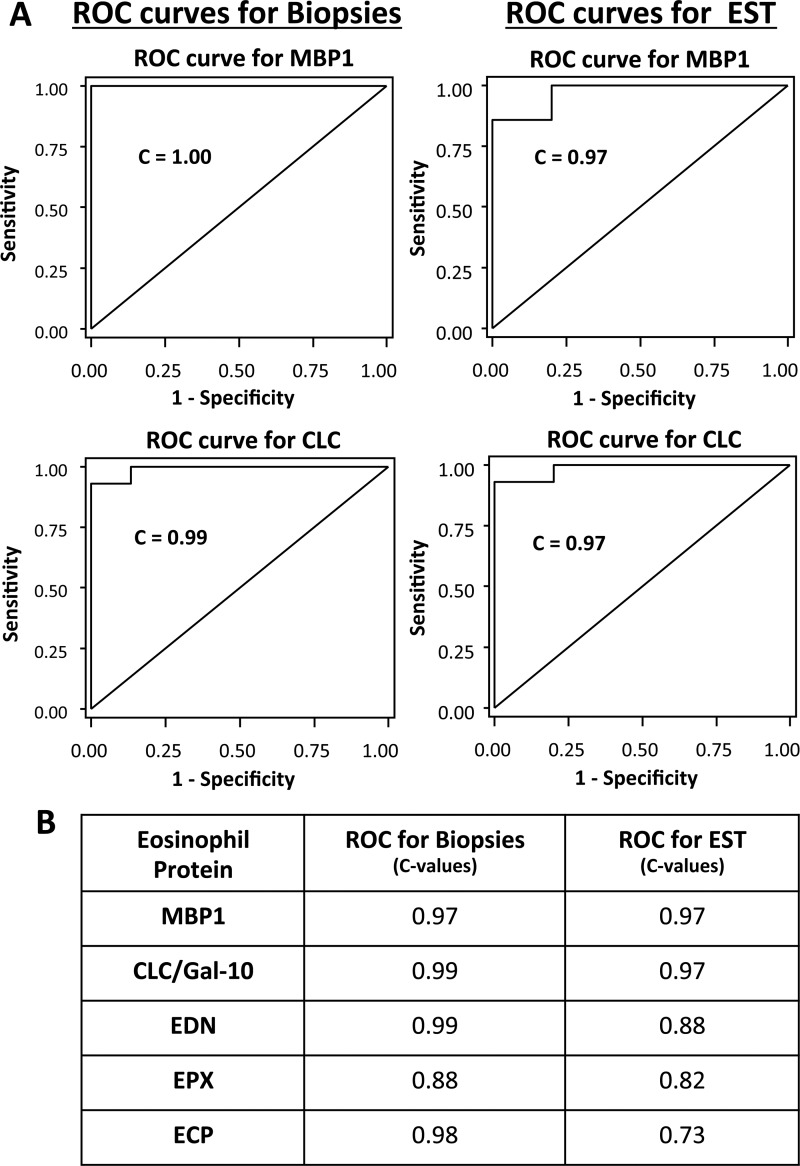

EST-based assessment of eosinophil-derived proteins represents a sensitive and specific test for oesophageal eosinophil inflammation

We next sought to determine whether assessments of subjects using mucosal biopsies and EST-based measurements of eosinophil specific proteins achieved diagnostic/therapeutic thresholds that would permit their use to diagnose and monitor children with EoE. ROC curves for eosinophil-derived protein concentrations of MBP1 and CLC measured in mucosal biopsies and ESTs indicated a high predictive power with C=1.00 and C=0.99 for mucosal biopsy sampling, and C=0.97 and C=0.97 for EST sampling, respectively (figure 4A). Significant predictive values were also true for each of the other eosinophil-derived proteins (figure 4B and online supplementary figure S6).

Figure 4.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the diagnosis of eosinophilic oesophagitis with biopsies and oesophageal string test (EST) sampling of eosinophil-derived proteins. ROC sensitivity versus specificity curves (A) are shown for biopsies (left panels) and ESTs (right panels) for measurements of major basic protein-1 (MBP1) and Charcot–Leyden crystal protein/galectin-10 (CLC/Gal-10) in biopsy extracts and EST supernatants. C-statistics (the area under the ROC curve) are indicated as a measure of the discriminating ability of each biomarker. (B) C-values for the ROC curves for biopsies and EST samples for other eosinophil secondary granule proteins are presented here and graphically in online supplementary figure 6. ECP, eosinophil cationic protein; EDN, eosinophil-derived neurotoxin; EPX, eosinophil peroxidase.

Discussion

EoE is a chronic disease characterised histologically by epithelial eosinophilia.1 2 To date, oesophageal eosinophilia can only be fully assessed by procuring mucosal biopsies during endoscopic procedures. While endoscopy with biopsy is a safe, efficacious and commonly performed procedure, it is also costly, time consuming and carries potential complications. In an effort to determine a less expensive, quicker and safer alternative to endoscopic biopsy, we wondered whether mucosal eosinophilia associated with EoE could be assessed in a less invasive manner using an FDA-approved device, the Enterotest.16–18 We hypothesised that detection of eosinophil-derived proteins in the oesophageal lumen would be reflective of oesophageal mucosal microenvironments. We used the proximal portion of the Enterotest and termed this the EST. Results from these studies demonstrate that: (1) ESTs captured luminal eosinophil-derived proteins, (2) luminal eosinophil-derived protein concentrations correlated significantly with those present in oesophageal mucosal biopsies and (3) luminal measures of inflammation correlated with disease activity. Taken together, these results demonstrate that measurements of luminal eosinophil-derived proteins reflect mucosal inflammation in EoE.

Past difficulties in assessing oesophageal inflammation have been characterised primarily by the inability to directly access inflamed mucosal surfaces and the limited number of biomarker(s) to assess disease activity. Attempts to measure biomarkers from peripheral sites such as the blood or stool may or may not be reflective of the oesophageal mucosal microenvironment, and EoE studies to date have lacked sufficient sensitivity and specificity to be clinically useful.13–15 Our study showed for the first time that tissue concentrations of eosinophil-derived proteins correlated with eosinophil number and likewise with disease states. This novel finding provided us with another metric to evaluate luminal measurements of eosinophil-derived proteins captured by the EST.

Other measures of oesophageal function such as ultrasound, endoflip, stationary and mobile motility monitoring and pH/impedance monitoring are invaluable to document anatomy and real-time oesophageal function, but they cannot analyse biochemical features of oesophageal inflammation.25–27 Therefore, we first tested the ability of the Enterotest to capture eosinophil proteins from the oesophageal lumen. Consistent with previous studies that used the Enterotest to geographically target different sections of the gastrointestinal tract,16–19 we used the proximal end of Enterotest to directly measure oesophageal inflammation in children with EoE. Our results demonstrate that oesophageal portions of the Enterotests or the EST detected luminal concentrations of eosinophil-derived proteins which correlated significantly with the gold standard eosinophil enumeration (peak and mean), the recently defined methodology, EPX Staining Index and the herein described measurements of eosinophil-derived proteins in biopsy extracts. The high degree of correlation of eosinophil-derived proteins from EST samples with these metrics provides very strong support for the use of the EST to biochemically interrogate the oesophageal mucosa.

Our findings document the use of the EST to capture eosinophil-derived proteins and its potential use as a device to assist in monitoring therapeutic efficacy in patients with EoE. In this regard, therapeutic efficacy could be monitored on a more regular basis following changes in treatments or during exacerbations of disease. However, the small number of GORD patients studied to date, and the lack of commercially available standardised ELISAS for a number of eosnophil biomarker, currently obviate use of the EST as a diagnostic device for EOE pending further studies.

Cellular and molecular profiles of secretions liberated from mucosal surfaces of the intestinal, bronchial and rhinopulmonary tracts provide robust and reproducible findings indicative of disease activity in other diseases.28–30 In this regard, our study as well as studies of patients with eosinophil-related diseases such as asthma and allergic conjunctivitis revealed that eosinophils and their products are deposited generously within affected mucosal surfaces and these can be captured in fluids obtained from the lung, tears and now the oesophagus.31–36

Eosinophilic inflammation of the oesophageal mucosa may or may not contain evidence of superficial eosinophilia as characterised by endoscopic findings of white exudates, histological patterns of microabscess formation and/or superficial layering.3 5 6 37 38 Our results are highly suggestive that eosinophil-derived proteins can be captured regardless of whether gross or histological evidence of surface eosinophilia is present, but further studies will need to be completed to validate this finding.

Eosinophil-derived proteins are biologically potent molecules that carry significant functional activities relevant to the mechanisms of pathogenesis in EoE. In animal models, MBP has been shown to contribute to increased epithelial permeability, smooth muscle contraction and liberation of molecules related to tissue remodelling and fibrosis.11 12 39 40 These functional properties bear particular relevance to patients with EoE. Pathogenetic mechanisms related to EoE include alterations in barrier function with dysregulated filaggrin expression,41 altered oesophageal motility and oesophageal stricture formation/long segment narrowing.26 27 Thus, ongoing identification and measurement of eosinophil-derived proteins may provide additional insights into pathogenetic mechanistic pathways.

In this study, ESTs captured eosinophil-derived proteins successfully, but a few technical and biological issues remain to be addressed. Whereas this study focused on measurements of eosinophil-derived proteins as a biomarker of EoE, future studies will need to identify novel intraluminal biomarkers that will allow for the differentiation of EoE from other forms of oesophagitis. Identification and validation of these biomarkers will then offer increased diagnostic capacity of the device, especially in the assessment of patients with dysphagia and other symptoms referable to the oesophagus. To maximise the ability of ESTs to harvest measureable levels of eosinophil-derived proteins from oesophageal secretions, this study was performed leaving ESTs in the oesophagus overnight. The eventual use of ESTs will be best suited to an office setting, and ongoing studies are testing shorter incubation times. Contamination from swallowed oropharyngeal or refluxed gastric secretions may alter oesophageal measurements, but our data (not shown) related to gastric contamination suggest low inconsequential eosinophil-derived protein levels in the stomach. Minimally detectable levels of eosinophil-derived proteins in normal patients could have been from undetected oesophageal inflammation in swallowed nasal/oral secretions; these levels did not reach those detected in active EoE patients. The primary sources of proteins measured here are eosinophils, but basophils, mast cells, neutrophils and T lymphocytes also express or sequester low levels of some of these proteins.42–49 These sources may also help to explain the non-zero values of ESGPs in control and treated subjects.

In summary, we have demonstrated the use of a minimally invasive test, the EST, to document mucosal inflammation in children with EoE. Although we do not suggest that the EST will replace endoscopy and biopsy as a critical tool for analyses of EoE, it certainly has the potential to significantly improve the evaluation and treatment of patients with EoE who may require repeated assessments of their oesophageal mucosae. In addition, as future biomarkers are identified and validated for EoE, ESTs may be able to differentiate patient phenotypes that are more predisposed to complications or responsive to various treatments.

Acknowledgments

We thank the physicians (Robert Kramer, Edward Hoffenberg, Edwin Liu, Edwin de Zoeten, David Brumbaugh, Christine Waasdorp, Shikha Sundaram, Cara Mack, Michael Narkewicz, Ronald Sokol, Jason Soden, Deborah Neigut, Barry K Wershil, Lee Bass, Jennifer Strople) and nurses (Tammy Armstrong and Jo Anne Newton), research assistants (Rachel Harris, Alyson Yeckes, Joseph Ruybal, Katherine Dunne), pathology staff (Sara Garza) and endoscopy technical staff (Bill Markovich) who contributed to this work by helping to provide and collect samples and recruit subjects. We thank Shikha Sundaram, David Brumbaugh and Sean Colgan for their helpful comments on the manuscript development and Len Ross for his insights in this study. We are grateful to our patients and families who consented to be a part of this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: GTF and SJA: study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; statistical analysis; obtained funding; administrative, technical and material support; study supervision. JJL: study concept and design; analysis and interpretation of the data; critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content; obtained funding; administrative, technical and material support; study supervision. VM: study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; technical support. CP: acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; technical support. SO: acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; statistical analysis; technical and material support. JM: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; administrative, technical and material support. KA and SS: acquisition of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; administrative, technical and material support; study supervision. AFK: acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content; obtaining funding; administrative, technical and material support; study supervision. HM-A, PA and BM: acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; administrative, technical and material support. MK: acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; administrative, technical and material support. DA, ML, CK and DF: acquisition of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. ZP: study design; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; statistical analysis. SF: acquisition of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; administrative, technical and material support. WM: acquisition of data; study design; administrative, technical and material support; study supervision; critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content. ZR: acquisition of data; administrative, technical and material support; study supervision; critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content. KC: acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Funding: This work supported in part by grants or gifts from NIH–R21AI079925 (GTF/SJA), Thrasher Research Fund (GTF/SJA), supported by NIH/NCATS Colorado CCTSI grant number UL1 TR000154 (GTF). Shell, Mandell, Boyd and Savoie Families (GTF), American Gastroenterological Association (GTF/SJA), Campaign Urging Research for Eosinophilic Diseases (SJA/GTF), Buckeye Foundation (AFK), Pappas Foundation (GTF), American Partnership for Eosinophilic Disorders (SJA/AFK/GTF), Sandhill Scientific (GTF/SJA), Mayo Foundation and NIH HL058732 (PI: Nancy A. Lee, JJL), and the NCRR K26 RR0109709 (JJL), NIH- 1UL1RR025741 (AFK).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by the Colorado Multi-Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data measuring gastric protein levels are available for public review.

References

- 1.Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology 2007;133:1342–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;128:3–20 e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kephart GM, Alexander JA, Arora AS, et al. Marked deposition of eosinophil-derived neurotoxin in adult patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:298–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mueller S, Aigner T, Neureiter D, et al. Eosinophil infiltration and degranulation in oesophageal mucosa from adult patients with eosinophilic oesophagitis: a retrospective and comparative study on pathological biopsy. J Clin Pathol 2006;59:1175–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mueller S, Neureiter D, Aigner T, et al. Comparison of histological parameters for the diagnosis of eosinophilic oesophagitis versus gastro-oesophageal reflux disease on oesophageal biopsy material. Histopathology 2008;53:676–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Protheroe C, Woodruff SA, de Petris G, et al. A novel histologic scoring system to evaluate mucosal biopsies from patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:749–55 e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ackerman SJ, Liu L, Kwatia MA, et al. Charcot-Leyden crystal protein (galectin-10) is not a dual function galectin with lysophospholipase activity but binds a lysophospholipase inhibitor in a novel structural fashion. J Biol Chem 2002;277:14859–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dvorak AM, Letourneau L, Login GR, et al. Ultrastructural localization of the Charcot-Leyden crystal protein (lysophospholipase) to a distinct crystalloid-free granule population in mature human eosinophils. Blood 1988;72:150–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aceves SS, Ackerman SJ. Relationships between eosinophilic inflammation, tissue remodeling, and fibrosis in eosinophilic esophagitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2009;29:197–211, xiii–xiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aceves SS, Broide DH. Airway fibrosis and angiogenesis due to eosinophil trafficking in chronic asthma. Curr Mol Med 2008;8:350–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kagalwalla AF, Akhtar N, Woodruff SA, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: epithelial mesenchymal transition contributes to esophageal remodeling and reverses with treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;129:1387–96 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pegorier S, Wagner LA, Gleich GJ, et al. Eosinophil-derived cationic proteins activate the synthesis of remodeling factors by airway epithelial cells. J Immunol 2006;177:4861–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Konikoff MR, Blanchard C, Kirby C, et al. Potential of blood eosinophils, eosinophil-derived neurotoxin, and eotaxin-3 as biomarkers of eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;4:1328–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta SK. Noninvasive markers of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2008;18:157–67; xi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Subbarao G, Rosenman MB, Ohnuki L, et al. Exploring potential non-invasive biomarkers in eosinophilic esophagitis: a longitudinal study in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2011;53:651–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas GE, Goldsmid JM, Wicks AC. Use of the enterotest duodenal capsule in the diagnosis of giardiasis. A preliminary study. S Afr Med J 1974;48: 2219–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gracey M, Suharjono, Sunoto Use of a simple duodenal capsule to study upper intestinal microflora. Arch Dis Child 1977;52:74–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beukeveld GJ, Bijleveld CM, Kuipers F, et al. Evaluation and clinical application of the Enterotest for the determination of human biliary porphyrin composition. Eur J Clin Chem Clin Biochem 1995;33:453–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liebman WM, Rosenthal P. The string test for gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Dis Child 1980;134:775–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ackerman SJ, Loegering DA, Venge P, et al. Distinctive cationic proteins of the human eosinophil granule: major basic protein, eosinophil cationic protein, and eosinophil-derived neurotoxin. J Immunol 1983;131:2977–82 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ackerman SJ, Corrette SE, Rosenberg HF, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of human eosinophil Charcot- Leyden crystal protein (lysophospholipase). Similarities to IgE binding proteins and the S-type animal lectin superfamily. J Immunol 1993;150:456–68 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swaminathan GJ, Weaver AJ, Loegering DA, et al. Crystal structure of the eosinophil major basic protein at 1.8 A. An atypical lectin with a paradigm shift in specificity. J Biol Chem 2001;276:26197–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ochkur SI, Kim JD, Protheroe CA, et al. The development of a sensitive and specific ELISA for mouse eosinophil peroxidase: assessment of eosinophil degranulation ex vivo and in models of human disease. J Immunol Methods 2012;375: 138–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walsh S, Antonioli D, Goldman H, et al. Allergic esophagitis in children: a clinicopathological entity. Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:390–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fox VL, Nurko S, Teitelbaum JE, et al. High-resolution EUS in children with eosinophilic “allergic” esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc 2003;57:30–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwiatek MA, Hirano I, Kahrilas PJ, et al. Mechanical properties of the esophagus in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2011;140:82–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nurko S, Rosen R, Furuta GT. Esophageal dysmotility in children with eosinophilic esophagitis: a study using prolonged esophageal manometry. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:3050–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balbi B, Pignatti P, Corradi M, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage, sputum and exhaled clinically relevant inflammatory markers: values in healthy adults. Eur Respir J 2007;30:769–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katial R. Biomarkers for nononcologic gastrointestinal diseases. Immunol Clin NA 2009;29:119–27; xi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leonardi A. In-vivo diagnostic measurements of ocular inflammation. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;5:464–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gleich GJ, Adolphson C. Bronchial hyperreactivity and eosinophil granule proteins. Agents Actions Suppl 1993;43:223–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koh GC, Shek LP, Goh DY, et al. Eosinophil cationic protein: is it useful in asthma? A systematic review. Respir Med 2007;101:696–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leonardi A, Borghesan F, Faggian D, et al. Eosinophil cationic protein in tears of normal subjects and patients affected by vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Allergy 1995;50:610–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trocme SD, Aldave AJ. The eye and the eosinophil. Surv Ophthalmol 1994;39:241–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Udell IJ, Gleich GJ, Allansmith MR, et al. Eosinophil granule major basic protein and Charcot-Leyden crystal protein in human tears. Am J Ophthalmol 1981;92:824–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.von Ungern-Sternberg BS, Sly PD, Loh RK, et al. Value of eosinophil cationic protein and tryptase levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid for predicting lung function impairment in anaesthetised, asthmatic children. Anaesthesia 2006;61: 1149–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peters MS, Schroeter AL, Kephart GM, et al. Localization of eosinophil granule major basic protein in chronic urticaria. J Invest Dermatol 1983;81:39–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leiferman KM, Ackerman SJ, Sampson HA, et al. Dermal deposition of eosinophil-granule major basic protein in atopic dermatitis. Comparison with onchocerciasis. N Engl J Med 1985;313:282–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Furuta GT, Nieuwenhuis EE, Karhausen J, et al. Eosinophils alter colonic epithelial barrier function: role for major basic protein. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2005;289:G890–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jacobsen EA, Taranova AG, Lee NA, et al. Eosinophils: singularly destructive effector cells or purveyors of immunoregulation? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;119: 1313–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blanchard C, Stucke EM, Burwinkel K, et al. Coordinate interaction between IL-13 and epithelial differentiation cluster genes in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Immunol 2010;184:4033–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abonia JP, Blanchard C, Butz BB, et al. Involvement of mast cells in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;126:140–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abu-Ghazaleh RI, Dunnette SL, Loegering DA, et al. Eosinophil granule proteins in peripheral blood granulocytes. J Leukoc Biol 1992;52:611–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aceves SS, Chen D, Newbury RO, et al. Mast cells infiltrate the esophageal smooth muscle in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, express TGF-beta1, and increase esophageal smooth muscle contraction. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;126:1198–204; e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ackerman SJ, Kephart GM, Habermann TM, et al. Localization of eosinophil granule major basic protein in human basophils. J Exp Med 1983;158:946–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ackerman SJ, Weils GJ, Gleich GJ. Formation of Charcot-Leyden Crystals by human basophils. J Exp Med 1982;155:1597–609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Butterfield JH, Weiler D, Peterson EA, et al. Sequestration of eosinophil major basic protein in human mast cells. Lab Invest 1990;62:77–86 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kubach J, Lutter P, Bopp T, et al. Human CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells: proteome analysis identifies galectin-10 as a novel marker essential for their anergy and suppressive function. Blood 2007;110:1550–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Monteseirin J, Vega A, Chacon P, et al. Neutrophils as a novel source of eosinophil cationic protein in IgE-mediated processes. J Immunol 2007;179:2634–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]