Abstract

Allergic asthma, a chronic respiratory disorder marked by inflammation and recurrent airflow obstruction, is associated with elevated levels of Interleukin-5 (IL-5) family cytokines, and elevated numbers of eosinophils (EOS). IL-5 family cytokines elongate peripheral blood EOS (EOSPB) viability, recruit EOSPB to the airways, and at higher concentrations, induce degranulation and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. While, EOSA remain signal ready in that GM-CSF treatment induces degranulation, treatment of EOSA with IL-5 family cytokines no longer confers a survival advantage. Since the IL-5 family receptors have common signaling capacity, but are uncoupled from EOSA survival while other IL-5 family induced endpoints remain functional, we tested the hypothesis that EOSA possess a JAK/STAT specific regulatory mechanism (since JAK/STAT signaling is critical to EOS survival). We found that IL-5 family-induced STAT3 and STAT5 phosphorylation is attenuated in EOSA relative to blood EOS from airway allergen-challenged donors (EOSCPB). However, IL-5 family induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation is not altered between EOSA and EOSCPB. These observations suggest EOSA possess a regulatory mechanism for suppressing STAT signaling distinct from ERK1/2 activation. Furthermore, we found, in EOSPB, IL-5 family cytokines induce members of the suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) genes, CISH and SOCS1. Additionally, following allergen challenge, EOSA express significantly more CISH and SOCS1 mRNA and CISH protein than EOSPB counterparts. In EOSPB, long-term pretreatment with IL-5 family cytokines, to varying degrees, attenuates IL-5 family induced STAT5 phosphorylation. These data support a model wherein IL-5 family cytokines trigger a selective down-regulation mechanism in EOSA for JAK/STAT pathways.

Introduction

Eosinophils (EOS) contribute to the pathophysiology of allergic diseases, including asthma, through activation and subsequent release of inflammatory mediators and pro-fibrotic factors (1-5). Our laboratory and others have observed that allergic airway inflammation leads to an elevation number of airway eosinophils (EOSA) (2, 6-9), and that this increased number of EOSA is associated with higher concentrations of pro-inflammatory IL-5 family cytokines (i.e. IL-5, IL-3, and GM-CSF), found in asthmatic bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid 48 hours after segmental broncho-provocation with allergen (SBP-Ag) (6, 8, 10-12). Incidentally, these IL-5 family cytokines are critical for normal eosinophil biology and function and signal through heterodimeric receptors comprised of a shared common β chain (IL-5Rβc) and a ligand specific α chain (i.e. IL-5Rα) (13, 14). Eosinophil activation via these cytokines leads to a number of signaling pathways (including the JAK/STAT and Ras-Raf-EK/ERK pathways (13, 15-19)) and physiologically relevant endpoints, such as differentiation and recruitment, enhanced survival, and release of cytotoxic proteins and reactive oxygen species (4, 12, 20-23).

Important to the pathophysiology of allergic diseases, such as allergic asthma, there are distinct physiologic differences between EOSA and circulating blood EOS (EOSPB). Such differences include up-regulated surface expression of certain integrins in EOSA relative to EOSPB (6), allowing for greater adherence and motility, and elongated viability in EOSA (12, 20). Interestingly, upon exposure to IL-5 family cytokines, peripheral blood EOS (EOSPB) down-regulate surface expression of the IL-5-specific subunit of the IL-5 receptor (IL-5Rα) as well as the IL-5Rβc (24-26) and increase IL-3Rα surface expression (23, 24, 26). This receptor expression profile of decreased IL-5Rα and IL-5Rβc as well as increased IL-3Rα is reflected in EOSA (27-29), which furthermore exhibit elevated GM-CSFRα surface expression (27). Once in the airway, and upon conclusion of the immunological response to challenge, it would be crucial that there exist some regulatory mechanism to inhibit continuous IL-5 family cytokine induced survival signals and to guard against unremitting EOS activation. Given the evidence that IL-5 family cytokines continue signal in EOSA (e.g. GM-CSF continues to induce degranulation (27), which is dependent on MEK/ERK pathway signaling (21)) but that EOSA survival is no longer enhanced by IL-5 family cytokines (12, 20, 30), we tested the hypothesis that, in addition to changes observed in IL-5 family receptor expression, there is/are (a) pathway specific mechanism(s) regulating EOSA responsiveness to IL-5 family cytokines.

One possible selective attenuation pathway involves the suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) family proteins. JAK/STAT signaling up-regulates SOCS family proteins, which serve as negative feedback regulators in several immune systems (31, 32). SOCS family proteins block phosphorylation of membrane receptors and JAK family members, and subsequently, inhibit STAT binding and phosphorylation (31, 33, 34), all necessary to induce downstream JAK/STAT signaling, which has been linked to IL-5 family-induced survival in EOS (22, 23). Interestingly, in a murine model of allergic inflammation, Lee and colleagues found two members of SOCS family of genes, SOCS1 and CISH, also referred to as CIS1, were, respectively, modestly and highly expressed in hematopoietic cells trafficking to the lungs after OVA-challenge (35). These findings, combined with the observation that CISH is inducible in human EOSPB (17), led us to CISH and SOCS1 up-regulation as a possible IL-5 family signaling regulatory mechanism in human EOS.

The data presented herein represent a unique opportunity to test these questions with highly purified peripheral blood and airway eosinophils from patients with asthma undergoing an allergic airway challenge, of which the literature is extremely sparse, as well as with control peripheral blood eosinophils from unchallenged participants. We found EOSA exhibit decreased IL-5 family stimulated phosphorylation of STAT5 (pSTAT5) and STAT3 (pSTAT3) compared IL-5 family stimulation of same-day isolation of blood eosinophils from the SBP-Ag-challenged individuals (EOSCPB), while IL-5 family stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation (pERK1/2) remained unaltered between EOSA and EOSCPB. We also found that EOSA express significantly more CISH and SOCS1 mRNA and CISH protein than EOSCPB, while EOSCPB in turn express more CISH and SOCS1 mRNA and CISH protein than EOSPB from independent, non-challenged donors. Additionally, we observed 24-hour pretreatment of EOSPB with IL-5 family cytokines, to varying degrees, attenuates the ability of subsequent IL-5 family-stimulation to induce pSTAT5. Taken together, these data suggest distinct regulation mechanisms by which STAT3 and STAT5 signal transduction may be altered in EOSA, as compared to regulation of other pathways stimulated by IL-5 family cytokines.

Methods

Subjects

These studies were approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for Health Sciences Human Subjects Committee. Each subject provided informed, written consent prior to participation. We recruited atopic and non-atopic volunteer donors who had EOS comprising 2 – 10% of their peripheral blood leukocytes.

Isolation and treatment of peripheral EOSCPB and EOSA

Human peripheral blood eosinophils were purified from heparinized peripheral blood, as described previously (23). Briefly, a granulocyte pellet was obtained by centrifugation of the blood through a Percoll monolayer (1.090 g/ml) and subsequent hypotonic lysis of erythrocytes. The resulting granulocytes were resuspended in Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) supplemented with 2% newborn calf serum (NCS) and incubated with anti-CD16-conjugated paramagnetic microbeads (MACS system; Miltenyi, San Jose, CA) to deplete contaminating neutrophils. Eosinophil populations were at least 98% pure and 97% viable.

Fluid from bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was recovered and EOSA were isolated 48 hours after segmental bronchoprovocation with allergen (SBP-Ag), where antigen dose for SBP defined and BAL performed as described (27, 36). In brief, EOSA were obtained after centrifuging BAL fluid through a Percoll bilayer (1.085/1.100 g/mL), with the recovered EOS population at the interface between the two layers. As above, purification continued with hypotonic lysis of erythrocytes and resuspension in HBSS plus 2% NCS and incubation with anti-CD16-conjugated paramagnetic microbeads. Eosinophil populations were at least 98% pure and 97% viable.

Peripheral blood eosinophils were isolated and purified from the same donors who underwent SBP-Ag (challenged peripheral blood, EOSCPB), obtained from phlebotomy that occurred immediately after recovery from the bronchoscopy procedure. Control experiments were performed in all cases on the same day with peripheral blood from a different, unchallenged donor to validate that the purification process did not result in EOS activation.

For all experiments, freshly isolated EOS (2 – 4 million per recovery source, i.e. EOSA, EOSCPB, or EOSPB) were divided evenly between treatments and were incubated at 37 °C in 25 mM HEPES-buffered RPMI containing 0.1% human serum albumin for 30 min, then stimulated with IL-5, IL-3, or GM-CSF at the concentrations and times indicated in figure legends. Loading controls were utilized to appropriately compare for differences in cell number between groups and donors.

Immunoblotting

Primary human EOS cultures were diluted with ice-cold STOP buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.4, 137 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 mM NaF, and 1% mammalian protease inhibitor cocktail), pelleted by centrifugation, and lysed in RIPA buffer (STOP buffer containing 0.1% v/v glycerol, 0.01% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.25% deoxycholic acid). Lysates were sonicated and centrifuged at 15,800 × gravity for 10 min to remove the insoluble fraction. Supernatants were assayed for total protein content using the Pierce Micro BCA protein assay (Rockford, IL), electrophoresed on SDS-PAGE gels and immunoblotted as described in the figure legends using antibodies against the following: phospho-Tyr 695 STAT5 and phospho-Tyr 705 STAT3 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), phospho-Thr 185,-Tyr 187 ERK1/2 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), CISH (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), STAT5 and STAT3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and Actin Ab-5 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Membranes were visualized using the Epichemi II darkroom (UVP, Upland, CA) equipped with a 12-bit cooled CCD camera. Relative immunoblot band densities were obtained via analysis with NIH Image J software version 1.38×. Alterations in expression or phosphorylation of protein were normalized to appropriate loading control levels.

Isolation of mRNA and subsequent qPCR

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) from EOSPB, media-treated or activated in vitro with GM-CSF, IL-3 or IL-5, and from EOSPB (n = 3), EOSA (n = 4), and EOSCPB (n = 6) isolated 48 hr after an in vivo allergen challenge. The reverse transcription reaction was performed using the Superscript III system (Invitrogen/Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). Expression of mRNA was determined by qPCR using SYBR Green Master Mix (SABiosciences, Frederick, MD, USA). Human CISH (F-GTCCAGCCGAGTCCCCACTCC, R-TGCTCACCCCTGAACGCAGAG) and SOCS1 (F-GCTGGCCCCTTCTGTAGGAT, R-TGCTGTGGAGACTGCATTGTC) specific primers were designed using Primer Express 3.0 (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and blasted against the human genome to determine specificity using http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast. The reference gene, β-glucuronidase (GUSB), (F-CAGGACCTGCGCACAAGAG, R-TCGCACAGCTGGGGTAAG), was used to normalize the samples. Standard curves were performed and efficiencies were determined for each set of primers. Efficiencies ranged between 94 and 96%. Data are expressed as fold change using the comparative cycle threshold (ΔΔCT) method as described previously (37). The values presented in Figure 4A and B are fold change (2-ΔΔCt) compared to the level in untreated EOSPB that level was fixed at 1 (n = 5). The values presented in Figure 5A and B are fold change (2-ΔΔCt) compared to the level in EOSPB that average level was fixed at 1 (± 0.168 for CISH and ± 0.287 for SOCS1, n = 3).

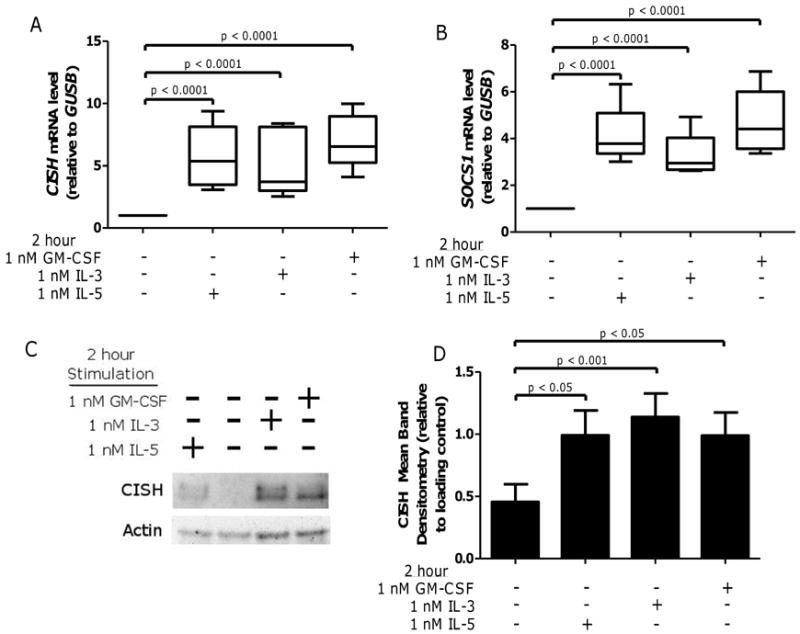

Figure 4. IL-5 family cytokines induce CISH and SOCS1 gene mRNA and protein in EOSPB.

EOSPB were purified, and treated for 2 hours with 1 nM IL-5, IL-3, or GM-CSF, then mRNA was extracted and purified or lysates were prepared for immunoblots. Real time PCR was used to quantify (A) CISH and (B) SOCS1 mRNA levels (relative to housekeeping gene GUSB) in five sample sets. Whiskers indicate range, box indicates the inner quartiles, central bar indicates the mean, p-values from mixed-effect ANOVA. (C) Lysates were immunoblotted for CISH with pooled data N = 9 (D) and normalized to actin. Data displayed fold change from IL-5 treated. Error bars indicate SEM, p-values from one-way ANOVA.

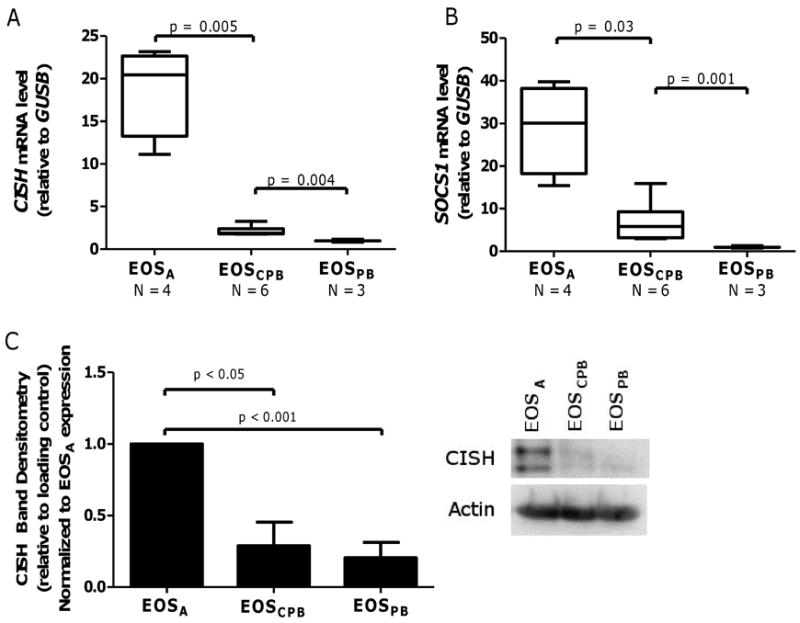

Figure 5. Compared to peripheral blood, EOSA exhibit elevated suppressors of cytokine signaling family members SOCS1 and CISH.

Real time PCR was used to quantify (A) CISH and (B) SOCS1 mRNA levels (relative to GUS1) in indicated number EOSA and peripheral blood EOS (EOSCPB and EOSPB). Whiskers indicate range, box indicates the inner quartiles, central bar indicates the mean, p-values from mixed-effect ANOVA. (C) Pooled data (N = 3) of CISH protein expression in purified non-stimulated EOSA, EOSCPB, and EOSPB, normalized to actin. Data display fold change from EOSA expression. Error bars indicate SEM, p-values from one-way ANOVA. Right panel: representative immunoblot.

Statistical analyses

Phosphorylated signaling markers and mRNA expression measures were compared among cell sources (EOSA, EOSCPB, EOSPB) and stimulants (media, IL-3, IL-5, GM-CSF) using either one-way ANOVA or linear mixed-effect ANOVA models with fixed-effect terms for cell source and stimulant and random-effect terms for donor and experiment to account for within-donor and within-experiment correlation. Measures were log-transformed as appropriate to achieve normal distributions and homogeneity of variance. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

IL-5 family cytokine-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation is unaltered between EOSA and EOSCPB while STAT5 and STAT3 phosphorylation is reduced in EOSA

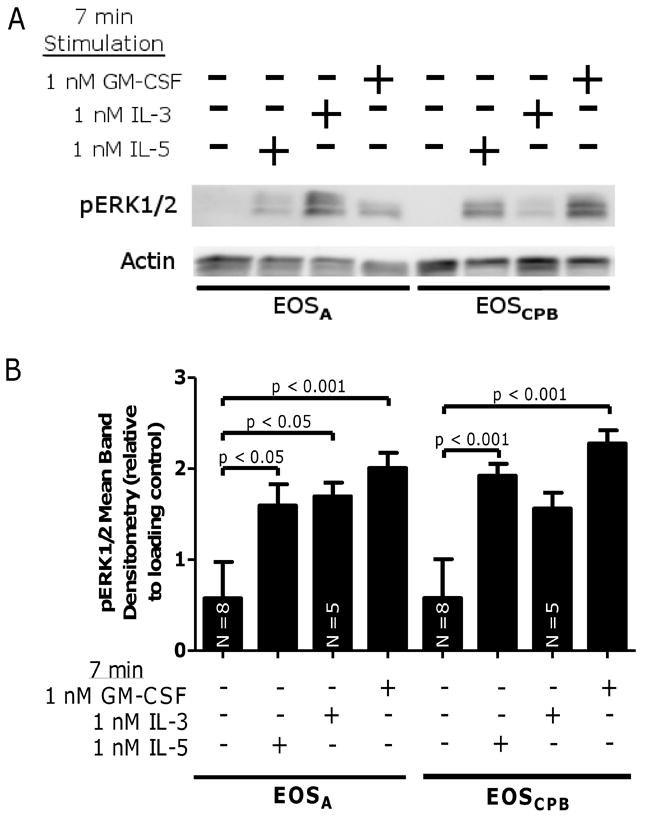

Compared to EOSCPB, EOSA exhibit phenotypic differences, including enhanced inflammatory capacity and prolonged survival uncoupled from IL-5 family cytokines (20, 30), while remaining responsive to IL-5 family cytokines regarding certain physiological endpoints, such as degranulation (27). Accordingly, we tested the idea that down-regulation in specific intracellular signaling pathways are associated with these phenotypic differences observed between EOSA and EOSPB. In this regard, IL-5 family cytokines have been shown by us and others to act via signaling cascades JAK/STAT (critical for IL-5 family-induced survival) and MAPK (crucial in IL-5 family induced degranulation) (4, 15-18, 21), thus we chose to examine these signaling cascades (at respective peak-activation time points) as potential markers of differences in EOSA and EOSPB/ EOSCPB activation. As shown in Figure 1, we found IL-5, IL-3, and GM-CSF elevates pERK1/2 in EOSA compared to media control (p < 0.05, p < 0.05, p < 0.001 respectively) (Figure 1A and B) to statistically equivalent levels relative to the respective cytokine-stimulation of pERK1/2 in EOSCPB (Figure 1B). Control experiments using EOSPB from unchallenged donors purified on the same day showed that the purification process does not alter baseline or IL-5 family cytokine stimulated pERK1/2 levels (Supplemental Figure 1A). These data are consistent with the previously observed reduction of IL-5Rα and elevation of IL-3Rα and GM-CSFRα on EOSA cell surface relative to circulating EOS (27, 28). Collectively, EOSA retain the capacity to activate ERK1/2 after stimulation ex vivo with IL-5 family cytokines.

Figure 1. IL-5 family cytokine-induced ERK1/2 activation is unaltered in EOSA.

(A) Representative blot of EOSA (lanes 1 – 4) and EOSCPB (lanes 5 – 8) stimulated for 7 minutes with media +/- 1 nM IL-5, 1 nM IL-3, or 1 nM GM-CSF. (B) Pooled data, N = 7 unless indicated on bar, corrected with loading control and log-transformed. Error bars indicate SEM, p-values from one-way ANOVA.

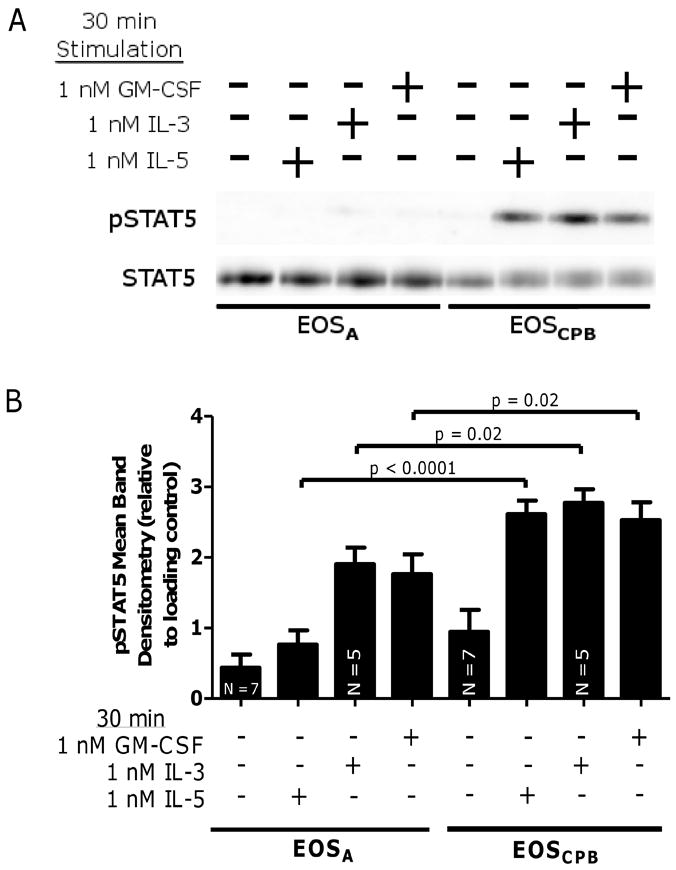

In contrast to the IL-5 family activation of pERK1/2 in EOSA, little to no pSTAT5 was detected in EOSA despite the fact that IL-5, IL-3, and GM-CSF elevated pSTAT5 in EOSCPB, while immunoblotting for total STAT5 indicates no change in total STAT expression (Figure 2A). IL-5, IL-3, and GM-CSF-stimulated pSTAT5 is significantly decreased in EOSA compared to the EOSCPB from that same challenged donor (p < 0.0001, p = 0.02, and p = 0.02, respectively) (Figure 2B). The purification process did not alter basal or IL-5 family cytokine stimulated pSTAT5 levels in EOSPB from unchallenged donors (Supplemental Figure 1B).

Figure 2. IL-5 family cytokine-induced STAT5 activation is attenuated in EOSA.

(A) Representative blot of EOSA (lanes 1 – 4) and EOSCPB (lanes 5 – 8) stimulated for 30 minutes with media +/- 1 nM IL-5, 1 nM IL-3, or 1 nM GM-CSF. (B) Pooled data, N = 6 unless indicated, corrected with loading control and log-transformed. Error bars indicate SEM, p-values from mixed-effect ANOVA.

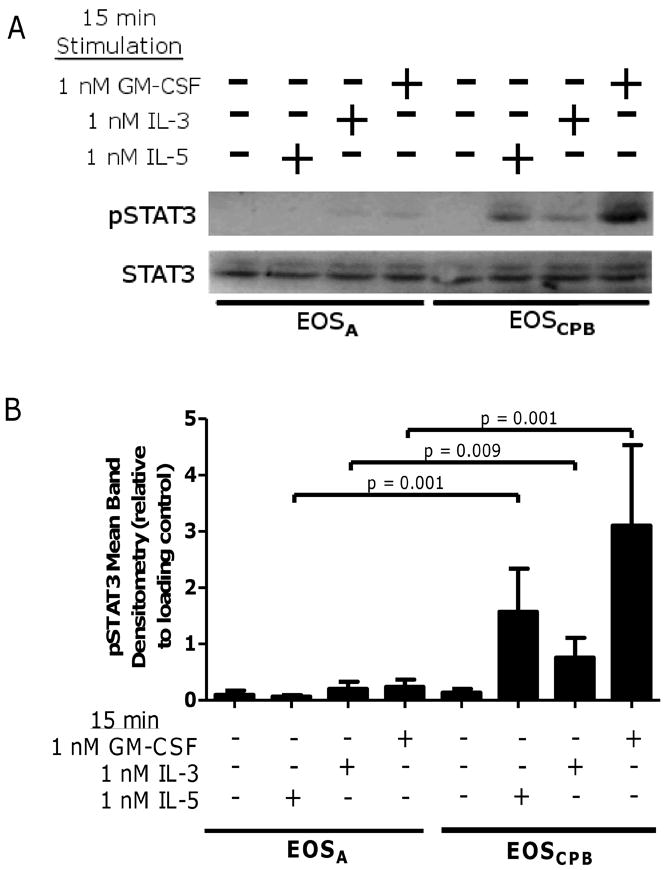

As shown in Figure 3, the pSTAT3 observations are similar to the pSTAT5 following stimulation with IL-5, IL-3, and GM-CSF. These treatments failed to induce pSTAT3 in EOSA (p = 0.001, p = 0.009, p = 0.001, respectively) relative to EOSCPB but did not alter total STAT3 levels (Figure 3A and B). Again, the purification process did not alter basal or IL-5 family cytokine stimulated pSTAT3 levels in EOSPB from unchallenged donors (Supplemental Figure 1C). Combined with observations that IL-3Rα and GM-CSFRα are present and even elevated on EOSA surfaces relative to EOSPB (27, 28), these data suggest there is potentially a JAK/STAT specific inhibition of IL-5 family cytokine signaling in EOSA.

Figure 3. IL-5 family cytokine-induced STAT3 activation is attenuated in EOSA.

(A) Representative blot of EOSA (lanes 1 – 4) and EOSCPB (lanes 5 – 8) stimulated for 15 minutes with media +/- 1 nM IL-5, 1 nM IL-3, or 1 nM GM-CSF. (B) Pooled data, N = 5, corrected with loading control. Error bars indicate SEM, p-values from mixed-effect ANOVA.

IL-5 family stimulation of EOSPB up-regulates mRNA transcripts and proteins for the Suppressors of Cytokine Signaling (SOCS) genes, CISH and SOCS1

Since phosphorylation of STAT3 and STAT5 are selectively attenuated following IL-5 family cytokine stimulation in EOSA, we sought to elucidate possible mechanisms by which this could occur. Others have observed that stimulation of immune cells with numerous cytokines activates both JAK/STAT pathways and up-regulates SOCS family proteins (31, 32, 34). SOCS proteins serve as a negative feedback mechanism to attenuate signaling through JAK/STAT cascades. To assess the relative expression of transcripts for this gene family in EOS, we stimulated EOSPB with IL-5 family cytokines and determined mRNA expression for the SOCS family members CISH and SOCS1. We found that stimulation with any of the IL-5 family cytokines results in a significant increase in expression of CISH and SOCS1 transcripts, with increases varying between about 2.5 and 10 fold compared to control treated EOSPB (Figure 4A and B). Immunoblotting confirmed that each IL-5 family cytokine up-regulates CISH protein expression at statistically significant levels (n = 9; IL-5 p < 0.05, IL-3 p < 0.001, GM-CSF p < 0.05) (Figure 4C and D).

EOS isolated after SBP-Ag express more CISH/SOCS1 compared to unchallenged EOS

Given our observations that IL-5 family members induce SOCS family gene expression, and that EOSA are refractory to IL-5 family cytokine-mediated STAT3/5 phosphorylation, we examined basal mRNA expression of CISH and SOCS1 and protein levels of CISH from untreated EOSA compared to untreated EOSCPB and EOSPB. At baseline, EOSA exhibit statistically elevated CISH and SOCS1 mRNA compared to EOSCPB isolated from the same individual (p = 0.005 and p = 0.03, respectively) (Figure 5A and B). Interestingly, mRNA transcripts from EOSCPB are also statistically elevated compared to expression levels from EOSPB at baseline (CISH p = 0.004, SOCS1 p = 0.001) (Figure 5A and B). This could suggest that the modest systemic elevation of these cytokines in acute inflammation causes a low-level activation of EOS. Immunoblotting for CISH protein confirmed the mRNA expression results, showing elevated CISH protein in EOSA compared to undetectable-to-low protein levels in both EOSCPB and EOSPB (n = 3, p < 0.05, p < 0.001, respectively) (Figure 5C).

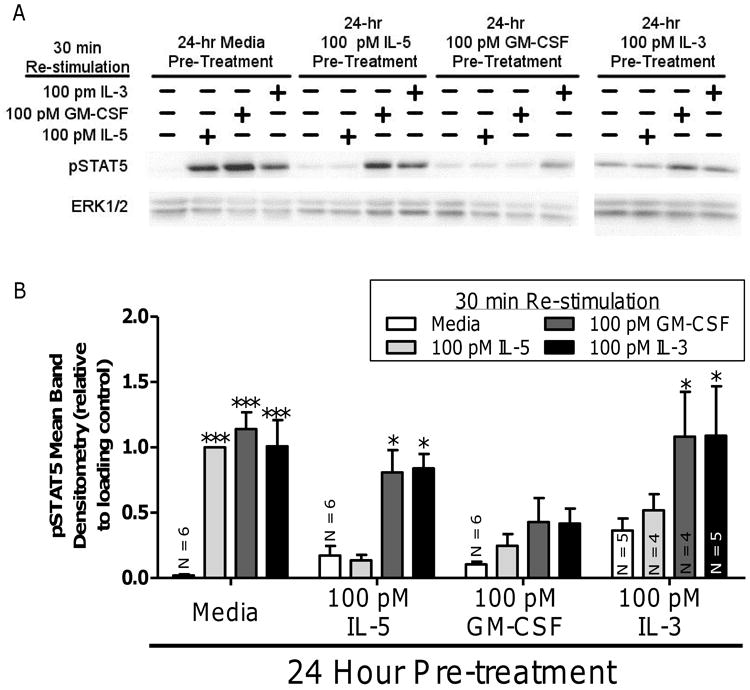

EOSPB exposed to GM-CSF recapitulate characteristic insensitivity of EOSA to IL-5 family cytokine-induced STAT5 phosphorylation

In vitro priming, achieved by exposing purified EOSPB to low concentrations of IL-5 family cytokines, recapitulates many behaviors/properties observed in EOSA, which are considered to be primed in vivo (1, 5, 8, 30, 38). Among other changes to eosinophil biology, as mentioned previously, priming EOSPB imparts decreased responsiveness to IL-5 family cytokines (24) through a relatively poorly understood mechanism that warrants additional research. To further our understanding of this decreased IL-5 family sensitivity (and therefore the process by which EOSPB progress to an EOSA-state), EOSPB were pretreated for 24 hours with media, IL-5, GM-CSF, or IL-3 then re-stimulated for 30 minutes with media, IL-5, GM-CSF, or IL-3 and pSTAT5 was assessed. As hypothesized, 24-hour media pretreatment permits each IL-5 family cytokine to induce significant levels of pSTAT5 after 30 minute treatment relative to media-alone re-stimulation (p <0.0001 for each cytokine, Figure 6). Interestingly, 24-hour GM-CSF pretreatment blocks any significant elevation of pSTAT5 relative to media-stimulated, regardless of which IL-5 family cytokine was used to re-stimulate. Furthermore, 24-hour pretreatment with IL-5, IL-3, or GM-CSF inhibits IL-5 re-stimulation from significantly elevating pSTAT5 significantly above the respective media-alone stimulation in agreement with previously discussed decreases in IL-5Rα surface expression. In either IL-5 or IL-3 pretreatment conditions, both IL-3 and GM-CSF re-stimulation significantly elevates pSTAT5 (IL-5 priming: p < 0.001 both GM-CSF and IL-3; IL-3 priming: p < 0.001 both GM-CSF and IL-3) (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Pre-treating human EOSPB with GM-CSF recapitulates down-regulation of IL-5 Family activated pSTAT5 in EOSA.

(A) Human EOSPB were treated 24 hours with media (lanes 1 – 4), 100 pM IL-5 (lanes 5 – 8), 100 pM GM-CSF (lanes 9 – 12), or 100 pM IL-3 (lanes 13 – 16), then, re-stimulated with 100 pM IL-5, 100 pM GM-CSF, or 100 pM IL-3 and probed for active STAT5. (B) Pooled data from five experiments, unless indicated on bar, was analyzed via 2-way ANOVA using post-hoc Bonferroni analysis p-values: * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.0001 compared to respective media, 24-hour pre-treatment

Discussion

IL-5 family cytokines modulate many EOS functions, including enhancing the inflammatory capacity and potentiating survival of the cell. In order to better manage certain inflammatory diseases, including allergic asthma, it is critical to better understand the phenotypic differences between EOSA and EOSPB. Elucidating mechanisms underlying the phenotypic differences would potentially provide insight into the efficacy of a range of therapeutics currently used as well as provide molecular targets for manipulation to alleviate EOS-associated symptoms present in allergic disorders like asthma. The goal of the present study was to determine the effect of IL-5 family cytokines on modulation of intracellular signaling in both EOSA and EOSCPB/EOSPB in terms of pERK1/2, pSTAT5 and pSTAT3, and expression of SOCS family members CISH and SOCS1.

Accordingly, we find that EOSA are refractory to IL-5 family induced pSTAT3 and pSTAT5 while inducing pERK1/2 at levels with no significant difference to that induced by IL-5 family cytokines in EOSCPB. Furthermore, expression levels of SOCS family members CISH and SOCS1 and CISH protein are elevated by IL-5 family cytokine stimulation. Interestingly, we observed an elevation of both CISH and SOCS1 mRNA and CISH protein in EOSA relative to both EOSCPB/EOSPB, with EOSCPB expressing significantly more CISH and SOCS1 mRNA compared to EOSPB. Also, 24-hour IL-5 family cytokine pretreatment of EOSPB attenuated the ability of IL-5 re-stimulation to induce pSTAT5. Furthermore, GM-CSF pretreatment additionally inhibited pSTAT5 induction by both IL-3 and GM-CSF. It is intriguing that only GM-CSF pretreatment attenuated IL-5 family re-stimulation of STAT5, regardless of the fact that all three IL-5 family cytokines induced CIS1 and SOCS1 genes. These collective data, gathered entirely from human donor samples from blood draws and/or bronchoaveolar lavage post-SBP-Ag, collectively point to a complex and specific system/mechanism of regulation that may influence eosinophil physiology and therefore inflammatory capacity and enhanced survival.

Given the differences our laboratory and others have observed between EOSA and EOSCPB/EOSPB, alterations in receptor subunit expression for the IL-5, GM-CSF, and IL-3 receptor α chains and the common β chain following SBP-Ag (23, 27, 28) cannot completely explain the general refractory nature of EOSA towards IL-5 family cytokines. For example, although the expression levels of the common β chain are decreased on EOSA, GM-CSF still induces release of eosinophil derived neurotoxin (EDN) where IL-5 cannot (27). If attenuation of downstream signaling was largely based on receptor common β chain expression levels, we would hypothesize that phosphorylation of ERK1/2, STAT3, and STAT5 would all be decreased in response to all IL-5 family cytokines in EOSA. If the downstream signaling attenuation was due to alterations in the ligand specific α chains, it would follow that only IL-5 induced signaling only would be attenuated with both IL-3 and GM-CSF induced signaling potentially increasing due to the elevated surface expression. However, neither of these models fit with the observations. Another plausible explanation would be that the decreased signaling may be a function of a threshold response needed for activation of one pathway versus another, or potentially represent a specific signaling pathway regulatory event. We know that IL-3 and GM-CSF have functional receptors on EOSA (27), which led us to test the hypothesis of altered signaling instead of pursuing the idea of an activation threshold. Also, the concentration of IL-5, IL-3, and GM-CSF used in the STAT3/5 and ERK1/2 phosphorylation experiments is in excess of the KD values of each receptor/ligand pairing (13, 22, 39-41). Our data indicate that phosphorylation of STAT5 and STAT3 is selectively attenuated in EOSA relative to ERK1/2 phosphorylation. These observations are in line with previous findings that indicate even after long-term exposure to IL-5, additional stimulation with IL-5 can phosphorylate MEK (24), indicating MEK/ERK signaling remains intact. We, therefore, hypothesized there is/are selective mechanism(s) which differentially affect(s) responses to these cytokines in the signaling pathways under consideration.

Our lab and others have found that in vitro stimulation of EOSPB with IL-5 family cytokines recapitulates certain signaling and physiological behaviors of EOSA regarding the enhanced responsiveness to pro-inflammatory chemokines, which EOSPB are normally minimally responsive to (1, 5, 20, 30, 38, 42, 43). Here, our data indicate that in vitro IL-5 family pretreatment of EOSPB is able to also recapitulate to different degrees the decreased responsiveness to IL-5 family-induced pSTAT5 observed in EOSA, proving a valuable model for EOSA, which are far less readily available than EOSPB. While the data here regarding the IL-5 family pretreatment indeed only represent a small subset of EOSA physiology, given the extremely limited literature surrounding the refractory nature of EOSA relative to IL-5 family stimulation (24, 27), this in vitro EOSPB system provides an exciting opportunity to research the EOS behavior upon IL-5 family exposure.

Reports from other immune cell systems have revealed that the SOCS family genes are up-regulated following STAT-induced transcriptional activation and selectively down-regulate signaling through JAK/STAT pathways (31, 34). Our data indicate that relative to EOSCPB/EOSPB, EOSA express elevated levels of CISH and SOCS1 mRNA and CISH protein. These data are in line with previous studies that indicate IL-5 and GM-CSF can induce CISH mRNA in human EOSPB (18) as well as systems in which SOCS family members down-regulate JAK/STAT signaling (31, 33, 34). For example CISH has been found to block STAT5b activity by binding to activating/dockings sites on signaling receptors (44, 45) while other members of the SOCS family proteins (i.e. SOCS1, SOCS2, and SOCS3) additionally block STAT5b activity (44). Interestingly, SOCS1 is capable of binding directly to the activating loop of JAK2 (46) thereby inhibiting several JAK/STAT-regulated signaling systems (reviewed in (47)). These previous data combined with our findings, therefore, present a possible mechanism for the JAK/STAT selective attenuation of signaling in response to IL-5 family cytokines in human EOS. Furthermore, based on our findings that all three IL-5 family cytokines induce CIS1 and SOCS1 mRNA products as well as CISH protein, we theorize that the systemic elevation of IL-5 family cytokines in disorders like allergic asthma may alter the responsiveness and inflammatory capacity of EOSA in distinct ways, which is further supported by the results that EOSCPB express significantly more CISH and SOCS1 mRNA than the non-challenged EOSPB. Additional support for the idea that expression of SOCS family members modulates EOS activation comes from a murine model of allergic airway inflammation. Deletion of Socs1 in an Ifng knockout mouse showed an overall intensification of asthma-like symptoms, including elevated eosinophil recruitment to the lungs, enhanced IgE serum levels, and increased cytokine and gene transcript production compared to the Ifng knockout alone (35), suggesting that in humans SOCS1 could play a crucial role in normal regulation of airway inflammation and EOSPB recruitment.

In terms of MEK/ERK signaling, IL-5 family cytokines are known to enhance eosinophil responsiveness to secondary stimuli that signal via G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) (4, 38, 43, 48). Since GPCRs often exhibit extensive cross-talk with MEK/ERK signaling pathways (49), including chemokine-induced GPCR signaling in EOSA (30), it would be crucial that many MEK/ERK signaling molecules remain signal-ready, which our observations support.

Given these data, future studies are necessary to further characterize the functional alterations that are observed between EOSA and EOSPB, including investigation of physiological endpoints and expression of any additional SOCS family members. One promising SOCS family member is SOCS3, which Lopez and colleagues found is inducible at the mRNA level in EOSPB and elevated in eosinophils from asthmatics and patients with eosinophilic bronchitis when compared to eosinophils from healthy control donors (32). Furthermore, SOCS3 has been observed to perform similar functions to both CISH and SOCS1, blocking JAK2 tyrosine kinase activity and has been linked to suppression of STAT3 activity (reviewed in (47)). The overlapping nature of these SOCS family members, and these SOCS3 data further support the idea that there is a very finely-tuned regulation system in these cells in which the smallest variations may lead to disease states, and that further research is warranted.

In summary, this study supports the idea that phenotypic differences observed between EOSPB and EOSA may be explained as functions of alterations in the signaling pathways that are modulated by IL-5 family cytokines. These cytokines serve to both recruit and activate EOSPB while providing negative-feedback mechanisms to regulate the inflammatory response of recruited EOS. This negative-feedback mechanism perhaps protects against inappropriate activation once the EOSPB have migrated to the site of allergic inflammation and are thus inundated with pro-inflammatory cytokines, including those of the IL-5 family. Manipulation of these regulatory pathways may provide new and novel therapeutics to alleviate symptoms in eosinophilic driven disorders such as allergic asthma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are extremely grateful to all our donors, especially our bronchoalveolar lavage volunteers. We also thank Sameer Mathur, MD, PhD, for oversight of the Laboratory Core that recruited and screened subjects and purified blood eosinophils; Elizabeth Schwantes, BS, and Paul Fichtinger, BS, for eosinophil purification; Larissa DeLain, BS, for her technical support; and Monica Gavala, PhD, for editorial comments.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grants NIH-NHLBI P01HL088594 to PJB and LCD, and 5T32DK007665 to MEB)

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bruijnzeel PL, Rihs S, Virchow JC, Jr, Warringa RA, Moser R, Walker C. Early activation or “priming” of eosinophils in asthma. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1992;122:298–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohno I, Nitta Y, Yamauchi K, Hoshi H, Honma M, Woolley K, O’Byrne P, Tamura G, Jordana M, Shirato K. Transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF beta 1) gene expression by eosinophils in asthmatic airway inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1996;15:404–409. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.15.3.8810646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yukawa T, Terashi K, Terashi Y, Arima M, Sagara H, Motojima S, Fukuda T, Makino S. Sensitization primes platelet-activating factor (PAF)-induced accumulation of eosinophils in mouse skin lesions: contribution of cytokines to the response. J Lipid Mediat. 1992;5:121–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bates ME, Green VL, Bertics PJ. ERK1 and ERK2 activation by chemotactic factors in human eosinophils is interleukin 5-dependent and contributes to leukotriene C(4) biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10968–10975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.10968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luijk B, Lindemans CA, Kanters D, van der Heijde R, Bertics P, Lammers JW, Bates ME, Koenderman L. Gradual increase in priming of human eosinophils during extravasation from peripheral blood to the airways in response to allergen challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:997–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johansson MW, Kelly EA, Busse WW, Jarjour NN, Mosher DF. Up-regulation and activation of eosinophil integrins in blood and airway after segmental lung antigen challenge. J Immunol. 2008;180:7622–7635. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohkawara Y, Lei XF, Stampfli MR, Marshall JS, Xing Z, Jordana M. Cytokine and eosinophil responses in the lung, peripheral blood, and bone marrow compartments in a murine model of allergen-induced airways inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;16:510–520. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.16.5.9160833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelly EA, Rodriguez RR, Busse WW, Jarjour NN. The effect of segmental bronchoprovocation with allergen on airway lymphocyte function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:1421–1428. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.5.9703054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mould AW, Ramsay AJ, Matthaei KI, Young IG, Rothenberg ME, Foster PS. The effect of IL-5 and eotaxin expression in the lung on eosinophil trafficking and degranulation and the induction of bronchial hyperreactivity. J Immunol. 2000;164:2142–2150. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broide DH, Firestein GS. Endobronchial allergen challenge in asthma. Demonstration of cellular source of granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor by in situ hybridization. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:1048–1053. doi: 10.1172/JCI115366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamid Q, Azzawi M, Ying S, Moqbel R, Wardlaw AJ, Corrigan CJ, Bradley B, Durham SR, Collins JV, Jeffery PK, et al. Expression of mRNA for interleukin-5 in mucosal bronchial biopsies from asthma. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1541–1546. doi: 10.1172/JCI115166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sedgwick JB, Calhoun WJ, Gleich GJ, Kita H, Abrams JS, Schwartz LB, Volovitz B, Ben-Yaakov M, Busse WW. Immediate and late airway response of allergic rhinitis patients to segmental antigen challenge. Characterization of eosinophil and mast cell mediators. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:1274–1281. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.6.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiPersio J, Billing P, Kaufman S, Eghtesady P, Williams RE, Gasson JC. Characterization of the human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:1834–1841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitamura T, Sato N, Arai K, Miyajima A. Expression cloning of the human IL-3 receptor cDNA reveals a shared beta subunit for the human IL-3 and GM-CSF receptors. Cell. 1991;66:1165–1174. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bates ME, Bertics PJ, Busse WW. IL-5 activates a 45-kilodalton mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase and Jak-2 tyrosine kinase in human eosinophils. J Immunol. 1996;156:711–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bates ME, Busse WW, Bertics PJ. Interleukin 5 signals through Shc and Grb2 in human eosinophils. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;18:75–83. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.18.1.2766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhattacharya S, Stout BA, Bates ME, Bertics PJ, Malter JS. Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-5 activate STAT5 and induce CIS1 mRNA in human peripheral blood eosinophils. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;24:312–316. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.24.3.4238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stout BA, Bates ME, Liu LY, Farrington NN, Bertics PJ. IL-5 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor activate STAT3 and STAT5 and promote Pim-1 and cyclin D3 protein expression in human eosinophils. J Immunol. 2004;173:6409–6417. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.10.6409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong CK, Zhang J, Ip WK, Lam CW. Intracellular signal transduction in eosinophils and its clinical significance. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2002;24:165–186. doi: 10.1081/iph-120003748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sedgwick JB, Calhoun WJ, Vrtis RF, Bates ME, McAllister PK, Busse WW. Comparison of airway and blood eosinophil function after in vivo antigen challenge. J Immunol. 1992;149:3710–3718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pazdrak K, Olszewska-Pazdrak B, Stafford S, Garofalo RP, Alam R. Lyn, Jak2, and Raf-1 kinases are critical for the antiapoptotic effect of interleukin 5, whereas only Raf-1 kinase is essential for eosinophil activation and degranulation. J Exp Med. 1998;188:421–429. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.3.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monahan J, Siegel N, Keith R, Caparon M, Christine L, Compton R, Cusik S, Hirsch J, Huynh M, Devine C, Polazzi J, Rangwala S, Tsai B, Portanova J. Attenuation of IL-5-mediated signal transduction, eosinophil survival, and inflammatory mediator release by a soluble human IL-5 receptor. J Immunol. 1997;159:4024–4034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bates ME, Liu LY, Esnault S, Stout BA, Fonkem E, Kung V, Sedgwick JB, Kelly EA, Bates DM, Malter JS, Busse WW, Bertics PJ. Expression of interleukin-5- and granulocyte macrophage-colony-stimulating factor-responsive genes in blood and airway eosinophils. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;30:736–743. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0234OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gregory B, Kirchem A, Phipps S, Gevaert P, Pridgeon C, Rankin SM, Robinson DS. Differential regulation of human eosinophil IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF receptor alpha-chain expression by cytokines: IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF down-regulate IL-5 receptor alpha expression with loss of IL-5 responsiveness, but up-regulate IL-3 receptor alpha expression. J Immunol. 2003;170:5359–5366. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hellman C, Hallden G, Hylander B, Lundahl J. Regulation of the interleukin-5 receptor alpha-subunit on peripheral blood eosinophils from healthy subjects. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;131:75–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02051.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshimura-Uchiyama C, Yamaguchi M, Nagase H, Matsushima K, Igarashi T, Iwata T, Yamamoto K, Hirai K. Changing expression of IL-3 and IL-5 receptors in cultured human eosinophils. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;309:26–31. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01526-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu LY, Sedgwick JB, Bates ME, Vrtis RF, Gern JE, Kita H, Jarjour NN, Busse WW, Kelly EA. Decreased expression of membrane IL-5 receptor alpha on human eosinophils: I. Loss of membrane IL-5 receptor alpha on airway eosinophils and increased soluble IL-5 receptor alpha in the airway after allergen challenge. J Immunol. 2002;169:6452–6458. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Julius P, Hochheim D, Boser K, Schmidt S, Myrtek D, Bachert C, Luttmann W, Virchow JC. Interleukin-5 receptors on human lung eosinophils after segmental allergen challenge. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:1064–1070. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.01986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu LY, Sedgwick JB, Bates ME, Vrtis RF, Gern JE, Kita H, Jarjour NN, Busse WW, Kelly EA. Decreased expression of membrane IL-5 receptor alpha on human eosinophils: II. IL-5 down-modulates its receptor via a proteinase-mediated process. J Immunol. 2002;169:6459–6466. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bates ME, Sedgwick JB, Zhu Y, Liu LY, Heuser RG, Jarjour NN, Kita H, Bertics PJ. Human airway eosinophils respond to chemoattractants with greater eosinophil-derived neurotoxin release, adherence to fibronectin, and activation of the Ras-ERK pathway when compared with blood eosinophils. J Immunol. 2010;184:7125–7133. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshimura A. Negative regulation of cytokine signaling. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2005;28:205–220. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:28:3:205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lopez E, Zafra MP, Sastre B, Gamez C, Fernandez-Nieto M, Sastre J, Lahoz C, Quirce S, Del Pozo V. Suppressors of cytokine signaling 3 expression in eosinophils: regulation by PGE(2) and Th2 cytokines. Clin Dev Immunol. 2011;2011:917015. doi: 10.1155/2011/917015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wormald S, Hilton DJ. Inhibitors of cytokine signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:821–824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R300030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yasukawa H, Sasaki A, Yoshimura A. Negative regulation of cytokine signaling pathways. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:143–164. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee C, Kolesnik TB, Caminschi I, Chakravorty A, Carter W, Alexander WS, Jones J, Anderson GP, Nicholson SE. Suppressor of cytokine signalling 1 (SOCS1) is a physiological regulator of the asthma response. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:897–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Denlinger LC, Kelly EA, Dodge AM, McCartney JG, Meyer KC, Cornwell RD, Jackson MJ, Evans MD, Jarjour NN. Safety of and cellular response to segmental bronchoprovocation in allergic asthma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e51963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Esnault S, Kelly EA, Nettenstrom LM, Cook EB, Seroogy CM, Jarjour NN. Human eosinophils release IL-1ss and increase expression of IL-17A in activated CD4(+) T lymphocytes. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42:1756–1764. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2012.04060.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sampson AP. IL-5 priming of eosinophil function in asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:513–517. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johanson K, Appelbaum E, Doyle M, Hensley P, Zhao B, Abdel-Meguid SS, Young P, Cook R, Carr S, Matico R, et al. Binding interactions of human interleukin 5 with its receptor alpha subunit. Large scale production, structural, and functional studies of Drosophila-expressed recombinant proteins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:9459–9471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lopez AF, Eglinton JM, Gillis D, Park LS, Clark S, Vadas MA. Reciprocal inhibition of binding between interleukin 3 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor to human eosinophils. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:7022–7026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.7022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murata Y, Takaki S, Migita M, Kikuchi Y, Tominaga A, Takatsu K. Molecular cloning and expression of the human interleukin 5 receptor. J Exp Med. 1992;175:341–351. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.2.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shindo K, Koide K, Fukumura M. PAF-induced eosinophil chemotaxis increases during an asthmatic attack and is inhibited by prednisolone in vivo and in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;237:146–151. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schweizer RC, Welmers BA, Raaijmakers JA, Zanen P, Lammers JW, Koenderman L. RANTES- and interleukin-8-induced responses in normal human eosinophils: effects of priming with interleukin-5. Blood. 1994;83:3697–3704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ram PA, Waxman DJ. Role of the cytokine-inducible SH2 protein CIS in desensitization of STAT5b signaling by continuous growth hormone. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39487–39496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004755200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Verdier F, Chretien S, Muller O, Varlet P, Yoshimura A, Gisselbrecht S, Lacombe C, Mayeux P. Proteasomes regulate erythropoietin receptor and signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5) activation. Possible involvement of the ubiquitinated Cis protein. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28185–28190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yasukawa H, Misawa H, Sakamoto H, Masuhara M, Sasaki A, Wakioka T, Ohtsuka S, Imaizumi T, Matsuda T, Ihle JN, Yoshimura A. The JAK-binding protein JAB inhibits Janus tyrosine kinase activity through binding in the activation loop. Embo J. 1999;18:1309–1320. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoshimura A, Naka T, Kubo M. SOCS proteins, cytokine signalling and immune regulation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:454–465. doi: 10.1038/nri2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu Y, Bertics PJ. Chemoattractant-induced signaling via the Ras-ERK and PI3K-Akt networks, along with leukotriene C4 release, is dependent on the tyrosine kinase Lyn in IL-5- and IL-3-primed human blood eosinophils. J Immunol. 2011;186:516–526. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luttrell LM. ‘Location, location, location’: activation and targeting of MAP kinases by G protein-coupled receptors. J Mol Endocrinol. 2003;30:117–126. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0300117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.