Abstract

Purpose

To investigate relationships between blood pressure (BP), ocular perfusion pressure (OPP), and intraocular pressure (IOP) in open-angle glaucoma (OAG) patients of different body mass index (BMI) classes.

Methods

Data from participants of a prospective, longitudinal, single site, observational study was analyzed. Patients with a prior diagnosis of OAG completed two baseline visits (one week apart) with follow up visits every 6 months for 2 years. At each visit, BP, weight, height, and IOP were recorded for normal weight (BMI=18.5-24.9; n=38), overweight (BMI=25.0-29.9; n=43) and obese (BMI ≥30; n=34) patients. BP was measured using automated ambulatory measurements after five minutes rest and IOP was measured using Goldmann applanation tonometry.

Results

IOP decreased from baseline to two-year measurement in normal weight (-1.5, 95%CI -2.7-(-0.4)), overweight (-1.9, 95%CI -3.4-(-0.4)), and obese (-2.5, 95%CI -3.9-(-1.2)) OAG patients. Systolic blood pressure (SBP) and OPP decreased from baseline to two-year measurement in all three BMI categories, although not reaching statistical significance. In normal weight patients, there was a significant, positive correlation between changes in IOP and SBP (r=0.36, p=0.0431). A significant, negative correlation was observed between changes in IOP and OPP in overweight (r=-0.56, p=0.0002) and obese (r=-0.38, p=0.0499) patients.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that in normal-weight individuals with OAG, changes in SBP were positively correlated to changes in IOP. However, this relationship did not exist for overweight or obese patients. Instead, overweight and obese patients displayed a negative correlation between OPP and IOP.

Keywords: Blood Pressure, Body Mass Index, Glaucoma, Intraocular Pressure, Ocular Perfusion Pressure, Open Angle Glaucoma

INTRODUCTION

Primary open angle glaucoma (OAG) is a multi-factorial optic neuropathy with characteristic progressive loss of retinal ganglion cells and visual field. Although increased intraocular pressure (IOP) is considered to be a major risk factor in the development of glaucoma, vascular elements, including systemic arterial blood pressure (BP) and ocular perfusion pressure (OPP), have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of OAG.

Hypertension is defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥90mmHg and has an increased prevalence in individuals with a Body Mass Index (BMI) of overweight (BMI = 25.0-29.9) or obese (BMI ≥ 30) (1). The association of high arterial BP with increases in IOP has been described in numerous studies; more recently, this relationship has been reported in Asian populations, including the Kumejima and Tajimi Studies in Japan, the Beijing Eye Study, and the Central Indian Eye and Medical Study (2-5).

There are two theories that exist to explain a mechanism for the proposed relationship between BP and IOP (6). The first theory speculates that the autonomic nervous system (ANS), an important regulator of BP, may affect the circadian rhythm of aqueous humor secretion, which should lead to corresponding changes in IOP (7). The second theory suggests that Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE), which is involved in the renin angiotensin system that influences BP, may also decrease IOP, possibly by inhibiting cholinesterase activity or by increasing prostaglandin synthesis (8). This is reinforced by studies where ACE inhibitors are used to reduce IOP in rabbits (8).

OPP is defined as the difference between arterial pressure and venous pressure, which is equal to or slightly greater than IOP (6). In large population based trials, including the Los Angeles Latino Eye and Barbados Studies, reduced OPP has been found to be associated with both the incidence and prevalence of glaucoma (9-10). Mechanistically, reduced ocular blood flow may be secondary to elevated IOP and/or reduced BP, or it could be the consequence of a primary insult to the ocular vasculature, such as vasospasm and/or faulty vascular auto-regulation (6).

The purpose of this analysis through the Indianapolis Glaucoma Progression Study (IGPS) is to investigate the relationship between BP, OPP, and IOP in different BMI classes of individuals with OAG.

Materials and METHODS

Patient data originated from the IGPS. The IGPS is a prospective, longitudinal, single site observational study of OAG patients from Indianapolis, Indiana and its surrounding areas conducted at Indiana University Hospital. All study procedures conformed to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the institutional review board at the Indiana University School of Medicine. Subjects signed informed consents prior to study entry.

Participants had received the diagnosis of OAG from a glaucoma specialist prior to enrollment in the IGPS, and were currently under the care of the diagnosing physician. Treatment decisions regarding glaucoma medications were made strictly by the primary ophthalmologists with no intervention from the research team. Two initial baseline measurements were performed one week apart, followed by visits every 6 months. These baseline measurements served as confirmation of both glaucomatous status and study measurement reliability. All exams were performed in the same order, at the same time of day, for each patient. All subjects had open angles on gonioscopic exam and had secondary causes of glaucoma ruled out during recruitment. In each participant, one qualified eye was randomly assigned as the observational study eye.

The inclusion criteria included: age of 30 years or older, OAG in the study eye as determined by a glaucoma specialist, best corrected Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study visual acuity of 20/60 or better in the study eye, and acceptable reliability indexes in previous visual fields (VF) performed.

The exclusion criteria included: advanced VF damage consisting of a mean deviation (MD) worse than -15 dB, evidence of pseudoexfoliation or pigment dispersion, history of acute angle closure glaucoma or a narrow occludable angle (per history), history of intraocular trauma, and severe or progressive retinal disease such as retinal degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, retinal detachment, or any abnormality preventing reliable applanation tonometry.

Body Mass Index: Height was measured in centimeters. Weight was measured in kilograms. The following equation was used to calculate the BMI:

BMI was categorized as follows: normal weight (BMI=18.5-24.9), overweight (BMI=25.0-29.9) and obese (BMI ≥30) (1).

Brachial Artery Blood Pressure: Brachial artery BP was assessed after a five-minute rest period using a calibrated automated sphygmomanometer (CVS, Woonsocket, RI) at the beginning of each study visit. Hypertension is defined as SBP ≥140 mmHg or DBP ≥90mmHg (1).

Mean arterial pressure (MAP): MAP was calculated using the following equation.

Intraocular Pressure: IOP was measured with Goldmann applanation tonometry.

Ocular Perfusion Pressure: OPP was calculated from the measured arterial BP and IOP measurements. The following equation was used to calculate the OPP:

Descriptive statistics including mean and standard error were computed. The mean change from baseline to two years was considered statistically significant if the 95% confidence interval did not include 1. Pearson correlation coefficients were determined to compare changes in measurements from baseline to two years between the study measurements. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

After two years of follow-up, data from 38 normal weight, 43 overweight, and 34 obese individuals at baseline was analyzed. By 2 years, 5 patients increased from normal weight to overweight, 3 patients decreased from overweight to normal weight, and 3 patients decreased from obese to overweight. The demographics of the study population at baseline are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics at baseline

| Parameter | Whole group | Normal weight | Overweight | Obese |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, n | 115 | 38 | 43 | 34 |

| Age, years (SE) | 65.0 (1.0) | 68.1 (1.9) | 62.2 (1.7) | 65.1 (1.6) |

| Gender, F/M | 70/45 | 26/12 | 26/17 | 18/26 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 44 (38%) | 12 (32%) | 14 (33%) | 18 (53%) |

| BMI, kg/m2 (SE) | 28.1 (0.5) | 22.4 (0.3) | 27.6 (0.2) | 35.3 (0.7) |

| SBP, mmHg (SE) | 134.3 (1.9) | 130.2 (3.4) | 132.7 (2.5) | 141.0 (3.8) |

| DBP, mmHg (SE) | 83.3 (1.0) | 81.3 (2.0) | 84.1 (1.1) | 84.5 (2.2) |

| MAP, mmHg (SE) | 100.3 (1.2) | 97.6 (2.3) | 100.3 (1.5) | 103.3 (2.5) |

| OPP, mmHg (SE) | 50.7 (0.9) | 49.6 (1.7) | 50.5 (1.3) | 52.3 (1.6) |

| IOP, mmHg (SE) | 16.1 (0.4) | 15.4 (0.6) | 16.3 (0.8) | 16.6 (0.6) |

| MD, dB (SE) | -3.5 (0.3) | -3.8 (0.6) | -3.7 (0.6) | -3.0 (0.6) |

| PSD, dB (SE) | 4.1 (0.3) | 4.5 (0.6) | 4.3 (0.6) | 3.6 (0.5) |

SE, standard error; BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure; OPP, ocular perfusion pressure; IOP, intraocular pressure; MD, mean deviation; PSD, pattern standard deviation

Normal weight, BMI=18.5-24.9; Overweight, BMI=25.0-29.9; Obese, BMI≥30; Arterial Hypertension, SBP≥140 mmHg or DBP ≥90mmHg

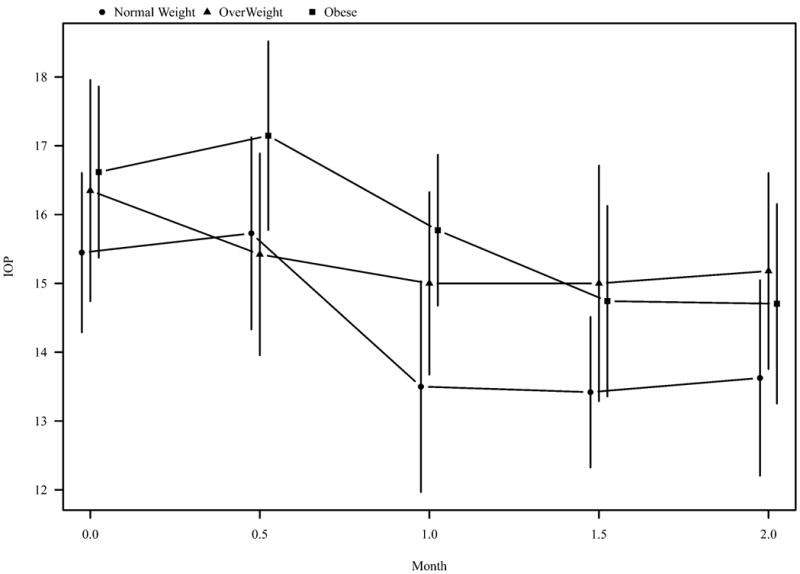

IOP decreased from baseline to two-year measurement in normal weight (-1.5, 95%CI -2.7-(-0.4)), overweight (-1.9, 95%CI -3.4-(-0.4)), and obese (-2.5, 95%CI -3.9-(-1.2)) OAG patients (Figure 1). SBP and OPP decreased from baseline to two-year measurement in all three BMI categories, although not reaching statistical significance. This is presented in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Intraocular pressure (IOP) in normal weight, overweight, and obese individuals over 2 years.

Table 2.

Change from baseline to two-year measurement.

| Measurement | Normal weight | Overweight | Obese |

|---|---|---|---|

| IOP, mmHg | -1.5 [95%CI -2.7-(-0.4)] | -1.9 [95%CI -3.4-(-0.4)] | -2.5 [95%CI -3.9-(-1.2)] |

| SBP, mmHg | -3.8 [95%CI -12.3-4.7] | -2.3 [95%CI -8.3-3.8] | -3.9 [95%CI -10.9-3.2] |

| OPP, mmHg | -0.3 [95% CI -3.9-3.2] | -0.1 [95% CI -3.5-3.4] | -0.7 [95% CI -2.6-4.0] |

| BMI, kg/m2 (SE) | -0.12 [95% CI -0.46-0.22] | -0.42 [95% CI -1.27-0.43] | -0.14 [95% CI -0.82-0.55] |

| MD, dB (SE) | -0.60 [95% CI -1.44-0.23] | -0.13 [95% CI -0.69-0.44] | 0.39 [95% CI -0.11-0.90] |

| PSD, dB (SE) | 0.19 [95% CI -0.16-0.53] | 0.15 [95% CI -0.35-0.65] | -0.41 [95% CI -0.90-0.08] |

IOP, intraocular pressure;SBP, systolic blood pressure;OPP, ocular perfusion pressure; CI, confidence interval

Normal weight, BMI=18.5-24.9; Overweight, BMI=25.0-29.9; Obese, BMI≥30

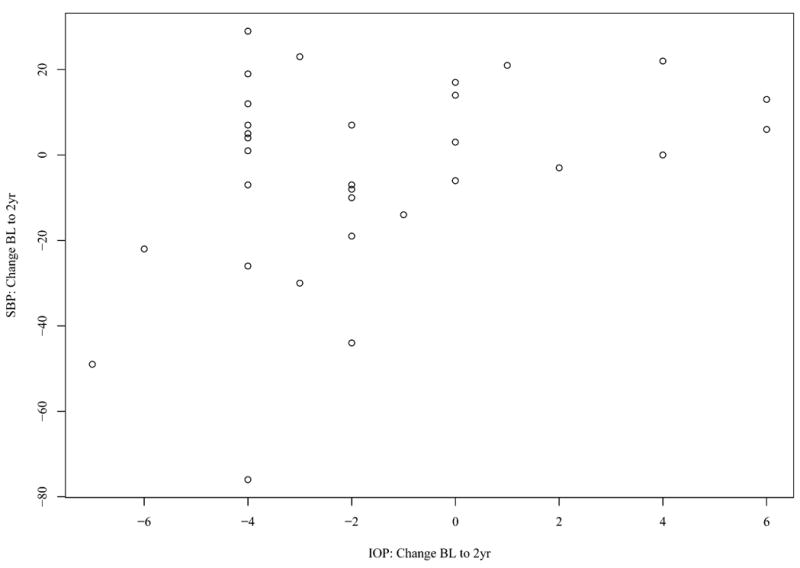

In normal weight patients, there was a significant, positive correlation between changes in IOP and SBP (r=0.36, p=0.0431), as shown in Figure 2. However, no correlation between IOP and SBP changes was observed in the overweight (r=-0.08, p=0.65) or the obese population (r=0.09, p=0.64). No significant correlation was found between DBP and IOP.

Figure 2.

Change in systolic blood pressure (SBP) from baseline (BL) to 2 years (2yr) versus change in intraocular pressure (IOP) from BL to 2yr in normal weight individuals.

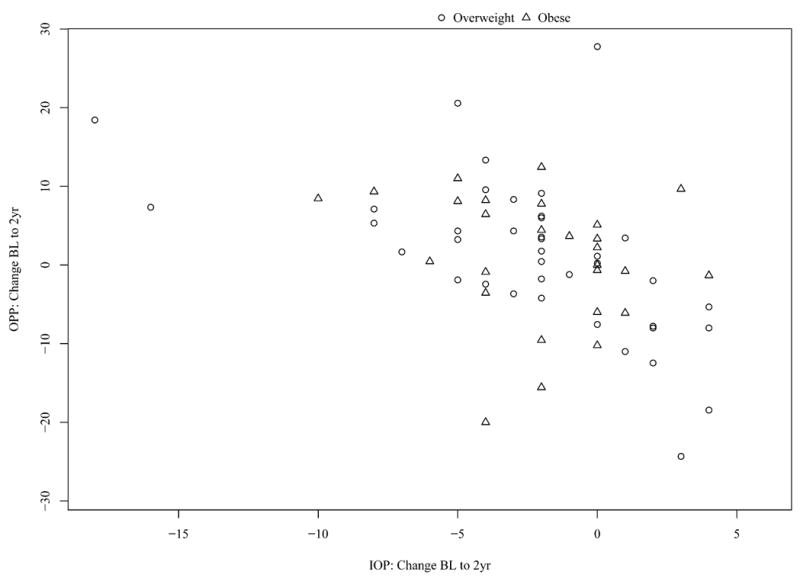

Conversely, there was a significant, negative correlation between changes in IOP and OPP in overweight (r=-0.56, p=0.0002) and obese (r=-0.38, p=0.0499) patients, as demonstrated in Figure 3. No correlation between IOP and OPP was observed in normal weight patients (r=0.03, p=0.89).

Figure 3.

Change in ocular perfusion pressure (OPP) from baseline (BL) to 2 years (2yr) versus change in intraocular pressure (IOP) from BL to 2yr in overweight and obese individuals.

DISCUSSION

This study analyzed a subset of the IGPS data to explore relationships between BP, OPP, IOP, and BMI in patients with glaucoma. Significant correlations were observed between SBP and IOP in normal weight individuals and between OPP and IOP in overweight and obese patients.

The changes that occurred in BP and IOP from baseline to 2 years are likely attributable to the medications that the patients were using. Beta blockers are utilized for the treatment of hypertension as well as OAG and thus may have overlapping systemic and ophthalmologic effects. The percentage of individuals taking various medications for managing BP at baseline and 2 years are listed in Table 3, and the percentage of those taking various medications for OAG at baseline and 2 years are listed in Table 4.

Table 3.

Medications used for managing blood pressure at baseline and 2 years.

| Medication | Used at Baseline (%) | Used at 2 years (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Metoprolol | 7 | 7 |

| Atenolol | 11 | 9 |

| Carvedilol | 1 | 2 |

| Lisinopril | 11 | 12 |

| Losartan | 5 | 5 |

| Amlodipine | 9 | 10 |

Table 4.

Medications used for managing glaucoma at baseline and 2 years.

| Medication | Used at Baseline (%) | Used at 2 years (%) |

| Timolol | 17 | 14 |

| Dorzolamide/Timolol | 13 | 15 |

| Latanoprost | 22 | 19 |

| Travoprost | 20 | 25 |

| Brimonidine | 17 | 16 |

| Brimonidine/Timolol | 1 | 8 |

Results of this study demonstrated that in normal weight individuals with OAG, changes in SBP were positively correlated to changes in IOP after two years. This association between IOP and SBP was not observed for overweight or obese individuals. Although several previous studies have explored the relationship between SBP and IOP, there have not been studies that specifically evaluate the differences between BMI categories. However, similar to our study, significant correlations between SBP and IOP have been shown. The Kumejima and Tajimi studies both found a significant correlation between elevated SBP and elevated IOP (2-3). Other studies found a significant correlation between increased IOP and increased SBP and DBP—specifically the Beijing, Barbados, Beaver Dam, Egna-Neumarkt, and Rotterdam Studies (4,10,12-14). One study, The Blue Eye Study, presented conflicting data as an increase in IOP with both increases and decreases in SBP and DBP was reported (15). However, the only statistically significant values stated in this article were an increase in mean IOP in the right eye by 0.28 mmHg (95%CI 0.23-0.34) for each 10 mmHg increase in SBP and by 0.52 mmHg (95%CI 0.40-0.66) for each 10 mmHg increase in DBP (15).

A negative correlation between changes in OPP and changes in IOP was found in overweight and obese patients. This correlation was not observed in normal weight individuals. Many epidemiological studies have investigated the role of OPP in OAG, but without relating OPP to IOP in different BMI classes. The important determination in these studies was that a reduced OPP is indeed a risk factor for OAG (9,10,13,16,17). The Barbados Study reported that lower systolic, diastolic, and mean perfusion pressures were risk factorsfor long-term OAG incidence in an African-descent population (10). The Latino Eye Study found that low systolic, diastolic, and mean perfusion pressures were associated with an increased prevalence of OAG in adult Latinos (9). The Egna-Neumarkt and Baltimore Eye Studies reported an increased risk of OAG with decreased diastolic perfusion pressures (13,16). The Early Manifest Glaucoma Trials identified lower systolic perfusion pressure as a predictor for OAG progression (17). One limitation of the current analysis is that we did not explore patients of African descent vs. European descent separately, although results from this analysis are underway and will be presented in a future manuscript.

The results of our study suggest that the relationship between SBP and IOP may more important than that between OPP and IOP in the normal weight population. In contrast, the relationship between OPP and IOP may be more important in the overweight and obese population. A possible reason for this discrepancy may be that normal weight individuals are less likely to suffer from hypertension, while overweight and obese individuals have a greater tendency toward elevated BP (1). Individuals with hypertension may have pathological changes of intraocular blood vessels; thus, their eyes may be more sensitive to changes in OPP (11). On the other hand, eyes of normal weight individuals may contain healthier, more resilient blood vessels that are adaptable to changes in OPP. However, this may not be applicable to our study due to the similarity in SBP between normal weight and overweight individuals at baseline. Another limitation is that the BP measurements in this study were only mildly elevated above normal and the length of time that the BP may have been elevated before being measured at baseline is unknown. Further investigation is required to help explain this incongruity among the BMI classes.

The longitudinal nature of the IGPS with 6 month follow-up for 2 years and even continuing onward for future analysis make our study unique compared to other epidemiological studies in that multiple other recent studies have been conducted for approximately 1 year or less (2, 3, 5, 9). The Blue Mountain Eye Study and Baltimore Eye Study are similar to our study in that they were also longitudinal in nature, spanning 2 and 3 years, respectively (15, 16).

Currently there is a lack of data describing the relationship between BP and IOP in American populations, despite the prevalence of hypertension in the overweight and obese populations in the United States. It could be exceedingly useful to establish a relationship between these two factors as hypertension could be managed through lifestyle and medical treatment. That is, BP could potentially be a modifiable risk factor for ocular hypertension and/or OAG.

In summary, a significant, positive correlation between SBP and IOP was observed in normal weight individuals, while a significant, negative correlation between OPP and IOP was observed in the overweight and obese BMI categories. As the IGPS study continues to gather data, relationships between systemic and ocular biometric factors may be further elucidated.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by: Grant 1R21EY022101-01A1 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

Footnotes

Authors do not have a proprietary interest relevant to this study. Dr. Alon Harris would like to disclose that he receives remuneration from MSD and Alcon for serving as a lecturer and from Merck, Pharmalight and Sucampo Pharmaceuticals for serving as a consultant. Investigator also holds an ownership interest Adom (which all relationships above are pursuant to IU's policy on outside activities).

All subjects in the study gave informed consent prior to participating. The study was conducted within the guidelines of the Indiana University Institutional Review Board.

References

- 1.Levine DA, Calhoun DA, Prineas RJ, Cushman M, Howard VJ, Howard G. Moderate waist circumference and hypertension prevalence: the REGARDS Study. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24(4):482–488. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.258. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomoyose E, Higa A, Sakai H, et al. Intraocular pressure and related systemic and ocular biometric factors in a population-based study in Japan: the Kumejima study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;150(2):279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.03.009. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawase K, Tomidokoro A, Araie M, Iwase A, Yamamoto T Tajimi Study Group; Japan Glaucoma Society. Ocular and systemic factors related to intraocular pressure in Japanese adults: the Tajimi study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92(9):1175–1179. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.128819. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu L, Wang H, Wang Y, Jonas JB. Intraocular pressure correlated with arterial blood pressure: the beijing eye study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144(3):461–462. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.05.013. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jonas JB, Nangia V, Matin A, Sinha A, Kulkarni M, Bhojwani K. Intraocular pressure and associated factors: the central India eye and medical study. J Glaucoma. 2011;20(7):405–409. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e3181f7af9b. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costa VP, Arcieri ES, Harris A. Blood pressure and glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(10):1276–1282. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.149047. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gherghel D, Hosking SL, Orgül S. Autonomic nervous system, circadian rhythms, and primary open-angle glaucoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 2004;49(5):491–508. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2004.06.003. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah GB, Sharma S, Mehta AA, Goyal RK. Oculohypotensive effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in acute and chronic models of glaucoma. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2000;36(2):169–175. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200008000-00005. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Memarzadeh F, Ying-Lai M, Chung J, Azen SP, Varma R Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Group. Blood pressure, perfusion pressure, and open-angle glaucoma: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(6):2872–2877. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2956. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leske MC, Wu SY, Hennis A, Honkanen R, Nemesure B BESs Study Group. Risk factors for incident open-angle glaucoma: the Barbados Eye Studies. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(1):85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.017. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Ciuceis C, Porteri E, Rizzoni D, et al. Effects of weight loss on structural and functional alterations of subcutaneous small arteries in obese patients. Hypertension. 2011;58(1):29–36. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.171082. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein BE, Klein R, Knudtson MD. Intraocular pressure and systemic blood pressure: longitudinal perspective: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(3):284–287. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.048710. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonomi L, Marchini G, Marraffa M, Bernardi P, Morbio R, Varotto A. Vascular risk factors for primary open angle glaucoma: the Egna-Neumarkt Study. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(7):1287–1293. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(00)00138-X. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hulsman CA, Vingerling JR, Hofman A, Witteman JC, de Jong PT. Blood pressure, arterial stiffness, and open-angle glaucoma: the Rotterdam study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125(6):805–812. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.6.805. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell P, Lee AJ, Wang JJ, Rochtchina E, de Jong PT. Intraocular pressure over the clinical range of blood pressure: blue mountains eye study findings. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(1):131–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.12.088. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tielsch JM, Katz J, Sommer A, Quigley HA, Javitt JC. Hypertension, intraocular pressure, and primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:216–221. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100020100038. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leske MC, Heijl A, Hyman L, Bengtsson B, Dong L, Yang Z EMGT Group. Predictors of long-term progression in the early manifest glaucoma trial. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(11):1965–1972. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.016. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]