Abstract

With respect to the treatment of addiction, the objective of extinction training is to decrease drug-seeking behavior by repeatedly exposing the patient to cues in the absence of unconditioned reinforcement. Such exposure therapy typically takes place in a novel (clinical) environment. This is potentially problematic, as the effects of extinction training include a context dependent component and therefore diminished efficacy is expected upon the patient’s return to former drug-seeking/taking environments. We have reported that treatment with the NMDAR coagonist D-serine is effective in facilitating the effects of extinction to reducing cocaine-primed reinstatement. The present study assesses D-serine’s effectiveness in reducing drug-primed reinstatement under conditions in which the context of extinction training is altered in rats self-administering cocaine. After 22 days of cocaine self-administration (0.5 mg/kg) in context “A”, animals underwent 5 extinction training sessions in context “B”. Immediately after each extinction session in “B”, animals received either saline or D-serine (60 mg/kg) treatment. Our results indicate that D-serine treatment following extinction in “B” had no effect on either IV or IP cocaine-primed reinstatement conducted in “A”. These results stand in contrast to our previous findings where extinction occurred in “A”, indicating that D-serine’s effectiveness in facilitating extinction training to reduce drug-primed reinstatement is not transferable to a novel extinction environment. This inability of D-serine treatment to reduce the context specificity of extinction training may explain the inconsistent effects observed in clinical studies published to date in which adjunctive cognitive enhancement treatment has been combined with behavioral therapy without significant benefit.

Keywords: D-serine, cocaine, self-administration, context, extinction, reinstatement

The environment an individual frequents to use addictive substances can play an important role in resumption of drug-taking, even after prolonged periods of abstinence. These contextual stimuli, along with stress, drug-associated cues, and the addictive drug itself are major impediments for maintaining abstinence during the treatment of cocaine addiction and have been observed to reinstate drug-seeking behavior in rodents [1]. Cocaine addiction can be defined as a psychological disease characterized by uncontrolled, compulsive drug-seeking and drug use despite negative health and social consequences [2]. To reduce the efficacy of drug predictive environmental stimuli to induce reinstatement of drug-seeking, extinction training or exposure therapy is often employed. The objective of extinction training is to decrease drug-seeking behavior by repeatedly exposing the individual to cues in the absence of the unconditioned reinforcer. Such exposure therapy typically takes place in a novel context (e.g. a rehabilitation center). This is potentially problematic because the effects of extinction therapy are context dependent and therefore diminished effectiveness of such therapy is expected upon the patient’s return to former drug-seeking/taking environments [3]. Most preclinical extinction/reinstatement studies do not take these environmental differences into account, as the extinction experience occurs in the same context as the acquisition of drug-taking [4].

Since the establishment of the involvement of N-Methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors during extinction learning in fear conditioning studies and reports of D-cycloserine facilitating conditioned fear extinction learning [5], interest in the use of NMDA receptor co-agonists during extinction training for the treatment of addiction has increased substantially. Recent attention has been given to D-cycloserine, a partial agonist at the co-agonist site on the NMDA receptor, for the treatment of cocaine addiction [6]. Various studies have revealed the efficacy of D-cycloserine to facilitate extinction and reduce drug-seeking using both the conditioned place preference (CPP) and the self-administration behavioral paradigms [7]. However, clinical research results to date have not been consistent with these promising preclinical reports. For example, clinical studies that have used D-cycloserine as an adjunctive treatment for addiction have revealed no effect on cue reactivity of heavy smokers [8]. D-cycloserine had no effect on cue reactivity or attentional tasks in heavy alcohol drinkers [9] and D-cycloserine administration increases craving in alcohol-dependent individuals [10] and cocaine-dependent participants [11, 12]. Thus, despite promising results from preclinical studies, those obtained from clinical trials have generally not been positive.

Previously, we have reported that treatment with the endogenous NMDA receptor co-agonist D-serine, is effective in facilitating the effectiveness of extinction to reduce cocaine-primed reinstatement using both the CPP [13] and the self-administration [14, 15] behavioral models in which extinction occurs in the same context as that of drug-seeking/taking. In the present study we assessed the effectiveness of D-serine in reducing the context specificity of extinction training to decrease cocaine-seeking behavior in rats with a history of extended access to cocaine self-administration.

Sprague–Dawley male rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA) weighting approximately 300 g at the start of the experiment, were singly housed in clear plastic cages. Rats were maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle (0700 hr/1900 hr) with food and water available ad libitum. These studies were approved by the University of Georgia Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Behavioral testing was conducted in self-administration operant chambers, the “A” environment (Med associates Inc., St. Albans, VT) previously described by Kelamangalath and Wagner [14]. For extinction training the “B” environment, “B”, was a modified version of the previously describe self-administration chamber. To create the novel “B” environment mesh grid flooring was substituted for the rod flooring, a black and white striped paper was attached to the rear wall, and the chamber was illuminated with the inactive lever light.

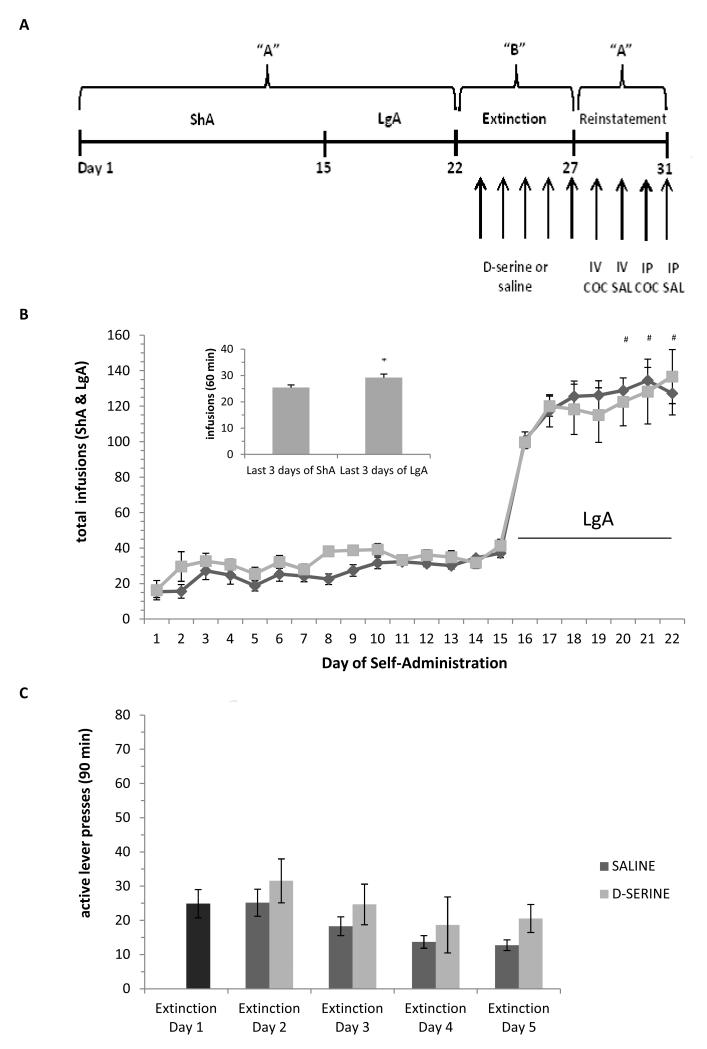

Before self-administration began an indwelling catheter was surgically placed into the right jugular vein of all animals, a detailed description of the jugular vein catheterization is described elsewhere [15]. After one week of recovery from surgery, animals were placed into the operant chambers to lever press for cocaine. Animals learned that lever pressing resulted in one infusion of cocaine (0.5 mg/kg) after which a 30 second timeout period began. During this timeout period, responses on the active lever had no programmed consequences. Self-administration was divided into three phases: 1) short access, ShA (90 min) on FR1 (days 1-10), 2) ShA on FR3 (days 11-15) and 3) long access, LgA (6 hr) on FR3 (days 16-22, Fig 1A).

Figure 1.

Experimental design for the “ABA” reinstatement protocol employed in the study. A) For the acquisition phase, context A (“A”) is the acquisition environment of cocaine self-administration. For the extinction phase, context B (“B”) is the novel environment of extinction training. Arrows represent one day. B) Cocaine self-administration and escalation of drug intake. The saline and D-serine treatment groups were similar in their acquisition of cocaine self-administration (days1-15) before extinction training and treatments began. On day 16, cocaine self-administration sessions were increased from 90 min to 6 hrs (LgA). The bar graph inset indicates significant escalation of drug intake after animals were switched to the LgA sessions, there was significantly increased drug-taking within the first 60 minutes of the final 3 LgA sessions as compared to the final 3 ShA sessions (* p<0.05, one-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak). During the LgA phase, analysis by two-way RM ANOVA indicates an effect of time, F(1, 26)=3.25, p<0.005. (#, p<0.01, Holm-Sidak compared with day 16), but not between the subsequently divided treatment groups. Dark gray diamonds represent the saline group and light gray squares represent the D-serine group. C) Over the course of five days of extinction training, there was a similar decline in active lever responding for both the saline and D-serine groups treated post session. A two-way RM ANOVA for extinction days 2-5 indicates an effect of time but not of treatment.

For extinction training (days 23-27) animals were split into two groups, “B” saline and “B” D-serine. During the 90 minutes extinction training sessions, rats were placed into “B”, where responses on the active lever and inactive lever resulted in no programmed consequences. Immediately after each extinction session, animals were given an IP injection of their respective treatment saline (0.9 %) or D-serine (60 mg/kg). Although the dose of D-serine used is this study was comparably low in relation to other published work [16, 17], we have recently published work supporting the use of as little as 30 mg/kg of D-serine for enhancing the effectiveness of extinction to reduce drug-primed reinstatement [13].

Following extinction training rats were tested for cocaine-primed reinstatement. On day 28, animals with patent catheters were placed into the original drug-taking environment, “A” and responding on the active and inactive levers were measured for the first 60 minutes under extinction conditions to allow context-induced reinstatement to subside. At t=60 minutes rats received a single noncontingent IV cocaine-prime (0.5 mg/kg) and the lever responding for the next 30 minutes was assessed. This IV reinstatement protocol was repeated on day 29 using a saline-prime. On subsequent reinstatement test days, animals received either an IP injection of cocaine (10 mg/kg, day 30) or saline (day 31) immediately prior to being placed back into the operant chamber.

Statistics were done using SigmaStat software, version 3.1. (Chicago, IL, USA) A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied for all data analysis except where noted. A value of P≤0.05 was taken as significant, being determined from the Holm-Sidak post hoc test method.

Self-administration behavior between the subsequently divided saline (n=19) and D-serine (n=9) treatment groups was comparable throughout the LgA acquisition phase (Fig. 1B), demonstrating that they entered the extinction phase with similar prior drug-taking experience. Regarding the effects of transitioning to extended access to cocaine, when comparing the first 60 minutes of lever pressing during the last three days of ShA (25.4 ± 1.0 presses) to lever pressing during the last three days of LgA (29.2 ± 1.4 presses) a significant increase is observed (* p <0.05, one-way ANOVA/ Holm-Sidak; Fig 1B, inset,). The observation of escalation of drug intake after transitioning to extended access is in concert with our own and other published work [14, 18].

After 22 days of cocaine self-administration the two groups of rats were divided into two groups (balanced for cocaine intake during LgA) and subjected to extinction training in a novel context, “B”, for five days. In these treatment groups, either saline or D-serine (60mg/kg, i.p.) was administered i.p. immediately after each extinction training session. A two-way ANOVA analysis showed that regardless of treatment, rats extinguished operant responding at a similar rate and were not statistically sigificant (Fig 1C). We have previously published work that is consistent with these results; D-serine did not significantly alter the rate of extinction in an ShA/LgA self-administration behavioral paradigm when extinction was conducted in the acquisition environment, “A” [14].

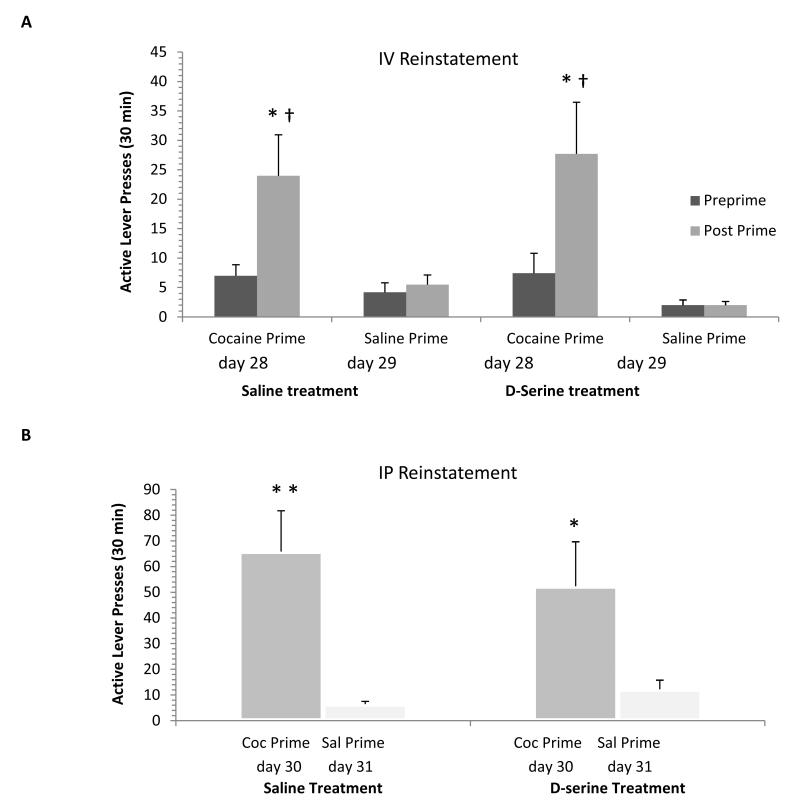

Following extinction training in “B”, all animals were tested in “A” for drug-seeking behavior using two types of noncontingent cocaine-priming tests; one administrated via the intravenous (IV) route and another administered via the IP route. On day 28 animal, for the first 10 mins, lever pressing was evaluated for context-induced reinstatement. Operant responding between the saline treatment group (16.4 ±3.2 presses) and the D-serine treatment group (18.7±5.4) were comparable (Suppl. Fig. 2). Later in the session, a comparison of the rats activity (day 28) for 30 min before (preprime) and for 30 min after (post prime) a cocaine IV prime (0.5mg/kg) demonstrates a significant increase in active lever pressing within both the saline (* p <0.05, one-way ANOVA/ Holm-Sidak) and D-serine (*p <0.05, one-way ANOVA/ Holm-Sidak) treatment groups (Fig. 2A). For the saline treatment group, comparing the day 28 cocaine post prime response (24.0 ± 7.0 presses) with the saline post prime response (5.5 ± 1.6 presses) on day 29, a difference in active bar pressing was evident († p <0.05, one-way ANOVA, Holm-Sidak). Similarly, in comparing the D-serine treatment group’s cocaine post prime responses (27.7 ± 8.8 presses) from day 28 with the saline post prime response (2.0 ± 0.7 presses) on day 29, there was again a significant difference in active lever pressing († p <0.05, one-way ANOVA, Holm-Sidak). Note that active lever pressing in the D-serine treatment group 30 minutes after a cocaine IV priming (27.7 ± 8.9 presses), was quite comparable in magnitude to that observed in the saline treatment group (24.0 ± 7.0 presses). Three animals from the saline treatment group and two animals from the D-serine treatment group catheters were blocked at the time of the IV cocaine challenge and data from these animals were therefore excluded from these results.

Figure 2.

The beneficial effects of cognitive enhancement following extinction training to reduce drug-primed reinstatement are not apparent using the “ABA” reinstatement protocol. A) Using the IV route, comparing 30 min before and after cocaine (0.5mg/kg) infusion in either the saline (n=16) or D-serine (n=7) treatment groups, there was a significant difference in lever pressing after a drug prime (PrePrime vs., Post Prime; * p<0.05, one-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak). In addition, post prime active lever pressing on day 28 was significantly increased as compared to that following a saline IV prime test performed on day 29 († p<0.05, one-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak). B) Using the IP route, cocaine (10mg/kg) significantly increased active lever pressing in both the saline treatment group (n=19, ** p<0.01, one-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak) and the D-serine treatment group (n=9, * p<0.05, one-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak) on day 30 as compared to a saline IP priming test on day 31. There was no significant difference in drug-seeking after a cocaine IP prime between the saline and D-serine treatment groups.

Evaluation of the IP reinstatement data showed that for the saline treatment group, when comparing the cocaine IP prime response (65.9 ± 15.9 presses) from day 30 to the saline IP prime (6.5 ± 1.1 presses) on day 31, there was a significant increase in active lever pressing (** p <0.01, one-way ANOVA/ Holm-Sidak; Fig. 2B). Similarly, in comparing the D-serine treatment group’s cocaine post prime response (52.3 ± 17.6 presses) from day 30 with the saline post prime response (12.2 ± 3.6 presses) from day 31, there was again a significant increase in lever pressing (* p <0.05, one-way ANOVA/ Holm-Sidak). Once again the active lever pressing in the D-serine treatment group 30 minutes after a cocaine IP priming (52.3 ± 17.6 presses), did not significantly differ from that observed in the saline treatment group (65.9 ± 15.9 presses). Thus, in concurrence with the IV priming results, the cocaine IP prime reinstatement test indicated no effect of D-serine treatment during extinction in “B” as compared to saline treatment. Together, these IV and IP drug-priming results indicate the effectiveness of D-serine in facilitating extinction training to reduce subsequent drug-primed reinstatement is not transferable when the extinction training has occurred in a novel context relative to that of the context associated with the acquisition of drug self-administration.

The primary result of the current report is that systemic administration of D-serine does not provide the beneficial effect of reducing cocaine-induced drug-seeking when extinction training occurs in a novel context (i.e. “ABA” protocol). We have previously shown that systemic administration of D-serine after each extinction training session is effective at reducing drug-primed reinstatement in rats when extinction is conducted in the original drug-taking environment (i.e. “AAA” protocol) [14]. However, the results of the present study are in concert with several other clinical studies [8-12] in which cognitive enhancement has not consistently resulted in decreased measures of craving or cue reactivity. The relation of these studies to the current results is discussed below.

We have considered D-serine, a full agonist at the strychnine-insensitive glycine modulatory site of the NMDA receptor, as a cognitive enhancer for the treatment of cocaine addiction. Previously, we have reported that when extinction training conditions are effective in reducing drug-primed reinstatement, an NMDA receptor antagonist can disrupt the ability of extinction training to decrease cocaine-induced drug-seeking [19]. In a complimentary fashion, we have also published work revealing the effectiveness of D-serine in reducing cocaine-primed reinstatement using ShA and LgA self-administration models [14, 15]. Despite this successful characterization of the effectiveness of D-serine in reducing cocaine-primed reinstatement tested in the “A” environment, the effectiveness of this treatment on drug-primed reinstatement when extinction training is conducted in a novel “B” environment has not been evaluated. This is of particular significance considering that a successful treatment for cocaine addiction with extinction training has yet to be established, likely due in part to the context specificity of extinction training [20, 21].

Our results revealed that after extended access to cocaine there was a significant escalation in drug intake over time. This result has also been observed in cocaine-dependent humans, as increases in frequency of drug intake and increases in the amount of drug use over time are hallmark characteristics of cocaine addiction [22]. In order to evaluate the effects of D-serine on the context dependency of extinction training, we modified the acquisition environment to create a novel context. Our results showed significantly increased lever pressing behavior upon the return to the acquisition environment after extinction training, as well as the animals in “A” lever pressed significantly more than animals extinguished in “B”, indicating that rats were able to differentiate between the two distinctive contexts (Suppl. Figs. 1&2). Finally, our results demonstrate that lever pressing after either an IV or an IP cocaine-prime was comparable between both treatment groups. Thus the context specificity of extinction training counteracted the positive effect of D-serine’s ability to reduce cocaine-primed reinstatement.

To date, there has been one other preclinical study that has assessed the effectiveness of an NMDA receptor co-agonist on the context dependency of extinction training to reduce drug-seeking behavior. In contrast to our current results, the published work from Torregrossa et al. [23] supports the use of cognitive enhancers for reducing the context dependency of extinction training. However, there are several noteworthy differences between their study and ours. For example, we have chosen to incorporate extended access into our rodent self-administration protocol, as it is thought to model some aspects of the state of addiction in humans [24]. A prominent characteristic of cocaine addiction is an increased frequency and an increase in the amount of drug ingested over time; the extended access protocol allows for the emulation of these traits. Additionally, we chose to examine the effects of D-serine on both IV and IP noncontingent drug-priming, an aspect of reinstatement to drug-seeking that is sensitive to extended access/LgA [25] as opposed to the cue-primed reinstatement tested by Torregrossa et al. [23]. Finally, another noteworthy difference is the specific cognitive enhancing agent that was administered. D-serine is an endogenous full agonist, whereas D-cycloserine is a partial agonist at the glycine modulatory site of the NMDA receptor [26]. It remains unclear as to which, if any, of these differences may underlie the disparate results observed between the current work and that of Torregrossa et al. [23].

Although most preclinical studies have shown that D-cycloserine paired with extinction can reduce drug-seeking/taking behavior, one report has shown that potentiation of the reconsolidation of cocaine-associated memories occurs when D-cycloserine is infused directly into the Basolateral Amygdala [27]. Eisenberg et al. [28] published work that reveals that the strength of conditioning and the strength of extinction training may determine whether cognitive enhancing treatment facilitates the original drug-associated memories or effects learning that occurs during extinction. During extinction newly formed memories compete for control of behavior with the original drug-associated memories [29]. Thus, if the original training is robust and extinction training is weak (i.e. fewer trials), reconsolidation of drug-associated memories could acquire control of behavior promoting drug-seeking or vice versa. In addition to promoting reconsolidation, another possible explanation for the discrepancies seen with D-cycloserine may be because it acts as a partial agonist at the glycine site of the NMDA receptor. D-cycloserine, when given to healthy individuals in the presence of increased levels of glycine, produced effects similar to those of NMDA receptor antagonists at low doses [30]. Therefore, it is possible that in an individual with high endogenous levels of glycine or D-serine, D-cycloserine may act in an antagonistic manner rather than as an agonist. At this point, it is clear that the various discrepancies among reports regarding the potential usefulness of D-cycloserine for the treatment of addiction may be explained by multiple possibilities.

Despite the accumulating clinical studies that have reported the relative ineffectiveness of D-cycloserine treatment for addiction [4], several recent reviews have recommended further investigation of the use of cognitive enhancers as treatment for cocaine addiction [31-33]. However, Kennedy et al. 2012 [34] have recently published a study in which the authors concluded that D-cycloserine treatment does not offer any additional advantages as compared to the placebo treatment group. Considering such results, we suggest that although treatments such as D-cycloserine and D-serine have been effective in treating fear-related conditions and decreasing the reinstatement drug-seeking behavior in rodents, they may not be effective in diminishing relapse in humans due to the interactions between context dependency and competition between consolidation and reconsolidation processes.

In summary, the efficacy of D-serine, a full agonist of the NMDA receptor at the glycine modulatory site in facilitating the effects of extinction training to reduce drug-primed reinstatement was not transferable to a novel context. This is an important observation when taken into consideration along with recent clinical work that has found D-cycloserine to be generally ineffective as an adjunctive agent for the treatment of addiction.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

D-serine did not facilitate extinction in the “ABA” reinstatement protocol.

Extinction in context B is ineffective in reducing drug-primed reinstatement.

D-serine did not alter IV or IP drug-primed reinstatement in the “ABA” protocol.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIDA DA 016302) to JJW and the Alfred P. Sloan Fellowship to SH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Epstein DH, Preston KL. The reinstatement model and relapse prevention: a clinical perspective. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168:31–41. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1470-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Baler RD, Volkow ND. Drug addiction: the neurobiology of disrupted self-control. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2006;12:559–66. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wickham JLM, Vurbic D, Froelich AA, Rosenblum DE, Thomas BL. The role of context similarity in ABA, ABC, and AAB renewal paradigms. Integrative Physiological and Behavioral Science. 2004;39:79. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Myers KMCWJ. D-cycloserine effects on extinction of conditioned responses to drug-related cues. Biological Psychiatry. 2012;71:944–55. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kaplan GB, Moore KA. The use of cognitive enhancers in animal models of fear extinction. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2011;99:217–28. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Brady KT, Gray KM, Tolliver BK. Cognitive enhancers in the treatment of substance use disorders: Clinical evidence. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2011;99:285–94. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Myers KM, Carlezon WA, Jr., Davis M. Glutamate Receptors in Extinction and Extinction-Based Therapies for Psychiatric Illness. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010 doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kamboj SK, Joye A, Das RK, Gibson AJ, Morgan CJ, Curran HV. Cue exposure and response prevention with heavy smokers: a laboratory-based randomised placebo-controlled trial examining the effects of D-cycloserine on cue reactivity and attentional bias. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;221:273–84. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2571-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Watson BJ, Wilson S, Griffin L, Kalk NJ, Taylor LG, Munafo MR, et al. A pilot study of the effectiveness of D-cycloserine during cue-exposure therapy in abstinent alcohol-dependent subjects. Psychopharmacology. 2011;216:121–9. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2199-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hofmann SGHR, Mackillop J, Kantak KM. Effects of d-Cycloserine on Craving to Alcohol Cues in Problem Drinkers: Preliminary Findings. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012:101–7. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.600396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Price KL, Baker NL, McRae-Clark AL, Saladin ME, Desantis SM, Santa Ana EJ, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled laboratory study of the effects of D: -cycloserine on craving in cocaine-dependent individuals. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2592-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Price KL, McRae-Clark AL, Saladin ME, Maria M, DeSantis SM, Back SE, et al. D-Cycloserine and Cocaine Cue Reactivity: Preliminary Findings. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35:434–8. doi: 10.3109/00952990903384332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hammond S, Seymour CM, Burger A, Wagner JJ. D-serine facilitates the effectiveness of extinction to reduce drug-primed reinstatement of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference. Neuropharmacology. 2013;64:464–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kelamangalath L, Wagner JJ. D-Serine treatment reduces cocaine-primed reinstatement in rats following extended access to cocaine self-administration Neuroscience. 2010;169:1127–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kelamangalath L, Seymour CM, Wagner JJ. D-Serine facilitates the effects of extinction to reduce cocaine-primed reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2009;92:544–51. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Duffy S, Labrie V, Roder JC. D-Serine augments NMDA-NR2B receptor-dependent hippocampal long-term depression and spatial reversal learning. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1004–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Karasawa J-I, Hashimoto K, Chaki S. D-Serine and a glycine transporter inhibitor improve MK-801-induced cognitive deficits in a novel object recognition test in rats. Behavioural Brain Research. 2008;186:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ahmed SH, Koob GF. Transition from moderate to excessive drug intake: change in hedonic set point. Science. 1998;282:298–300. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5387.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kelamangalath L, Swant J, Stramiello M, Wagner JJ. The effects of extinction training in reducing the reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior: Involvement of NMDA receptors. Behavioural Brain Research. 2007;185:119–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bouton ME. Context and behavioral processes in extinction. Learning & Memory. 2004;11:485–94. doi: 10.1101/lm.78804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Conklin CA, Tiffany ST. Applying extinction research and theory to cue-exposure addiction treatments. Addiction. 2002;97:155–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gawin FH, Kleber HD. Evolving conceptualizations of cocaine dependence. The Yale journal of biology and medicine. 1988;61:123–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Torregrossa MM, Sanchez H, Taylor JR. D-Cycloserine Reduces the Context Specificity of Pavlovian Extinction of Cocaine Cues through Actions in the Nucleus Accumbens. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30:10526–33. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2523-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Deroche-Gamonet V, Belin D, Piazza PV. Evidence for addiction-like behavior in the rat. Science. 2004;305:1014–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1099020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Knackstedt LA, Kalivas PW. Extended access to cocaine self-administration enhances drug-primed reinstatement but not behavioral sensitization. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322:1103–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.122861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Furukawa H, Gouaux E. Mechanisms of activation, inhibition and specificity: crystal structures of the NMDA receptor NR1 ligand-binding core. Embo J. 2003;22:2873–85. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lee JLC, Gardner RJ, Butler VJ, Everitt BJ. D-cycloserine potentiates the reconsolidation of cocaine-associated memories. Learning & Memory. 2009;16:82–5. doi: 10.1101/lm.1186609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Eisenberg M, Kobilo T, Berman DE, Dudai Y. Stability of retrieved memory: inverse correlation with trace dominance. Science. 2003;301:1102–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1086881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Berman DE, Hazvi S, Stehberg J, Bahar A, Dudai Y. Conflicting processes in the extinction of conditioned taste aversion: behavioral and molecular aspects of latency, apparent stagnation, and spontaneous recovery. Learn Mem. 2003;10:16–25. doi: 10.1101/lm.53703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Dickerson D, Pittman B, Ralevski E, Perrino A, Limoncelli D, Edgecombe J, et al. Ethanol-like effects of thiopental and ketamine in healthy humans. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2010;24:203–11. doi: 10.1177/0269881108098612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Nic Dhonnchadha BÁ, Kantak KM. Cognitive enhancers for facilitating drug cue extinction: Insights from animal models. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2011;99:229–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Olive MF, Cleva RM, Kalivas PW, Malcolm RJ. Glutamatergic medications for the treatment of drug and behavioral addictions. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2012;100:801–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Milton AL, Everitt BJ. The persistence of maladaptive memory: addiction, drug memories and anti-relapse treatments. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:1119–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kennedy AP, Gross RE, Whitfield N, Drexler KP, Kilts CD. A controlled trial of the adjunct use of D-cycloserine to facilitate cognitive behavioral therapy outcomes in a cocaine-dependent population. Addictive behaviors. 2012;37:900–7. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.