Abstract

Many patients with acute ischaemic stroke have contraindications to thrombolytic therapy. We describe a 45 yr old Afro-Caribbean female with HbSC disease whom was electively admitted for a cerebral angiogram to evaluate an intracavernous aneurysm measuring 20 mm in diameter. During the procedure, she suffered a right MCA territory ischaemic event with a NIHSS of 10. A CT angiogram demonstrated no dissection and no evidence of a major vessel occlusion. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) was administered intravenously within 60 minutes of symptom onset. She had clinical and haematological evidence of a painful sickle cell crisis and required manual exchange transfusion within a few hours of thrombolysis. This is the first reported case of the use of thrombolysis for acute stroke in a sickle cell crisis; and in the presence of such a large unruptured aneurysm. A registry of unusual thrombolysis cases might help clinicians in cases when there is little evidence to support decision-making.

Key words: Stroke, Thrombolysis, Aneurysm

Background and purpose

The benefits of thrombolysis with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) for acute ischaemic stroke have been demonstrated. However, many patients cannot be considered for treatment, often because of late presentation, but sometimes as a result of an absolute or relative contraindication to thrombolysis. These contraindications are numerous and include seizure at onset, rapidly resolving symptoms, known coagulopathy, major surgery within the preceding 21 days, or extracranial haemorrhage within 3 months. Some of the less frequently encountered contraindications include recent arterial puncture, or known intracranial arteriovenous malformation or unruptured aneurysm.

The purpose of this report is to illustrate the case of a patient with two relative contraindications to thrombolysis, who was nonetheless treated without significant complication.

Summary of case

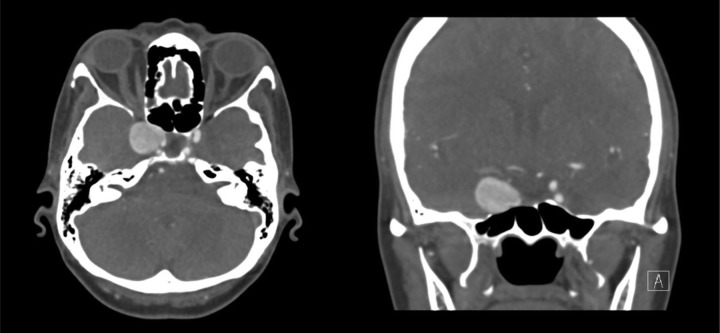

A 45 yr old Afro-Caribbean woman, with a past medical history of sickle cell (HbSC) disease, systemic sarcoidosis, and previous splenectomy, was found to have a large (20 mm diameter) right intracavernous internal carotid aneurysm as an incidental finding on an MRI brain scan organised for investigation of headaches. This was confirmed with CT angiography (Figure 1). She was electively admitted for a catheter angiogram to evaluate the anatomy of the aneurysm further prior to consideration of intervention.

Figure 1.

CT angiogram demonstrating the intracavernous aneurysm measuring 20 mm

Using a conventional femoral arterial approach, the right ICA was cannulated and the anatomy of the aneurysm defined. Following this the left ICA was catheterised, at which point the patient suddenly became confused and irritable. Examination revealed dysarthria and a dense left hemiparesis (MRC power 0/5 upper and lower limbs), visual inattention to the left, with an NIHSS (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale) score of 10. The catheter study was aborted and an urgent unenhanced CT brain scan did not demonstrate any early ischaemic changes or haemorrhage. A CT angiogram excluded iatrogenic arterial dissection and intracranial proximal arterial occlusion. At this stage it was felt that the likely aetiology was an embolic event related to instrumentation during the angiogram. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) was administered intravenously (0.9 mg/kg) within 60 minutes of symptom onset.

During thrombolysis, the patient started to complain of severe right foot pain and then back pain, which was treated with supplementary oxygen, intravenous fluids and pethidine analgesia. Blood tests revealed an HbS level of 47%, with an Hb of 9.7 g/dl. The haematologists were consulted; they advised manual exchange transfusion to reduce the sickle load and the risk of further stroke. A femoral vascath was inserted and transfusion was commenced, within 12 hours of thrombolysis.

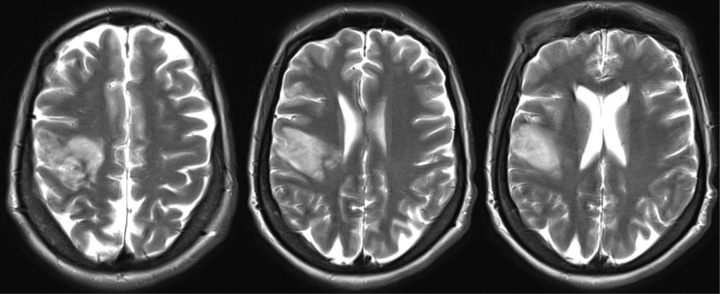

An MRI brain scan after 48 hours revealed a subacute right middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory infarct involving the lateral temporal lobe and posterior frontal lobe with evidence of mild haemorrhagic transformation (Figure 2), which was asymptomatic (no deterioration in NIHSS associated with this 0. Further investigations revealed no cardio-embolic source on echocardiography and 24 hours of ECG telemetry. Blood tests including treponemal serology, anti-nuclear Abs, anti-cardiolipin Abs, anti-beta2 glycoprotein 1 Abs, thyroid function tests, renal function, liver function, bone profile, cholesterol and glucose all normal. Her conventional vascular risk factors aside from her SC disease were limited to a history of smoking and a family history of ischaemic heart disease. Her prescribed medications before the acute event were Prednisolone, Methotrexate, Penicillin V, and Folate.

Figure 2.

MRI Brain revealing a subacute right MCA territory infarct involving the lateral temporal lobe and posterior frontal lobe with evidence of mild haemorrhagic transformation

The patient had further exchange transfusions (12 units in total) which reduced the HbS level to 10.8% and HbC to 10.6%. She was kept well oxygenated and hydrated. She was discharged for further rehabilitation with a small improvement to 8 of her NIHSS score.

Discussion

The decision to thrombolyse this patient was a challenging one, given her known unruptured large aneurysm, and little evidence in the published literature to guide us. We have reviewed the literature on this and on the thrombolysis of patients with sickle cell disease, on pubmed using the search terms “sickle cell”, “thrombolysis” and “aneurysm”.

Edwards et al (2012) published a retrospective study of their experience in 236 patients given tPA over an eleven year period at two academic medical centres. Tweny-two of these patients had unruptured intracranial aneurysms. The rates of haemorrhage did not significantly differ between those with or without an unruptured aneurysm. Furthermore, none of the patients receiving tPA with an unruptured aneurysm had a symptomatic bleed1. This was further substantiated by Mittal et al (2012) who carried out a retrospective analysis of 105 patients treated with tPA and evaluated with intracranial angiography, of whom 10 had an intracranial aneurysm. The rates of intracranial haemorrhage were again similar in both groups2. The size of the largest unruptured aneurysm reported previously in a patient that received tPA is 16 mm3. The aneurysm in our report is larger still with a diameter of 20 mm.

However, there are individual case reports of aneurysm rupture post-thrombolysis. Rammos et al (2011) described a 51 yr old female who presented with a subarachnoid haemorrhage from an acutely ruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysm after receiving tPA for an acute left middle cerebral artery embolism4. Lagares et al (1999) reported an acutely ruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysm eight hours after receiving tPA for an acute myocardial infarct5.

There is very little literature concerning the use of tPA in patients with sickle cell disease. Sidani et al (2008) described a 21 yr old male with HbSS who presented with an extensive venous sinus thrombosis that failed to improve 24hrs after receiving automated red blood cell exchange followed by intravenous heparin. He subsequently received tPA with recanalisation of the veins6. There are no reports in the literature of the use of thrombolysis for arterial stroke in sickle cell patients.

In summary, this is the first report of the use of thrombolysis for an arterial infarct in a sickle cell patient and in the presence of the largest unruptured aneurysm reported in the literature. On reviewing the literature, it is clear that some relative contra-indications to thrombolysis are not convincingly supported by evidence. Randomised trial data is unlikely to be forthcoming in most instances, so reports of treatment without complications may be helpful when faced with these management dilemmas. As thrombolysis becomes more common, there may be an opportunity to build up a registry of such cases as an aid to clinicians faced with these difficult management decisions.

DECLARATIONS

Sources of funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors

Conflict of interest

None to declare

Acknowledgements

All contributing authors are listed

References

- 1. Edwards NJ, Kamel H, Josephson SA. The safety of intravenous thrombolysis for ischemic stroke in patients with pre-existing cerebral aneurysms: a case series and review of the literature. Stroke 2012;43:412–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mittal MK, Seet RC, Zhang Y, et al. Safety of Intravenous Thrombolysis in Acute Ischemic Stroke Patients with Saccular Intracranial Aneurysms. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2012: Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=22341666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Desai JA, Jin AY, Melanson M. IV thrombolysis in stroke from a cavernous carotid aneurysm to artery embolus. Can J Neurol Sci. 2011;38:352–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rammos SK, Neils DM, Fraser K, et al. Anterior communicating artery aneurysm rupture after intravenous thrombolysis for acute middle cerebral artery thromboembolism: case report. Neurosurgery 2012;70:E1603–7; discussion E7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lagares A, Gomez PA, Lobato RD, et al. Cerebral aneurysm rupture after r-TPA thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction. Surg Neurol. 1999;52:623–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sidani CA, Ballourah W, El Dassouki M, et al. Venous sinus thrombosis leading to stroke in a patient with sickle cell disease on hydroxyurea and high hemoglobin levels: treatment with thrombolysis. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:818–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]