Abstract

Background

Diagnosis of significant coronary artery disease (CAD) in at risk patients can be challenging, typically including non-invasive imaging modalities and ultimately the gold standard of coronary angiography. Previous studies suggested that peripheral blood gene expression can reflect the presence of CAD.

Objective

To validate a previously developed 23-gene expression-based classifier for diagnosis of obstructive CAD in non-diabetic patients.

Design

Multi-center prospective trial with blood samples drawn prior to coronary angiography.

Setting

Thirty-nine US centers.

Patients

An independent validation cohort of 526 non-diabetic patients clinically-indicated for coronary angiography

Intervention

None.

Measurements

Receiver-operator characteristics (ROC) analysis of classifier score measured by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), additivity to clinical factors, and reclassification of patient disease likelihood vs disease status defined by quantitative coronary angiography (QCA). Obstructive CAD defined as ≥50% stenosis in ≥1 major coronary artery by QCA.

Results

The overall ROC curve area (AUC) was 0.70 ±0.02, (p<0.001); the classifier added to clinical variables (Diamond-Forrester method) (AUC 0.72 with classifier vs 0.66 without, p = 0.003). Net reclassification was improved by the classifier over Diamond-Forrester and an expanded clinical model (both p<0.001). At a score threshold corresponding to 20% obstructive CAD likelihood (14.75), the sensitivity and specificity were 85% and 43%, yielding NPV of 83% and PPV 46%, with 33% of patient scores below this threshold.

Limitations

The study excluded patients with chronic inflammatory disorders, elevated white blood counts or cardiac protein markers, and diabetes.

Conclusions

This non-invasive whole blood test, based on gene expression and demographics, may be useful for assessment of obstructive CAD in non-diabetic patients without known CAD.

Primary Funding Source

CardioDx, Inc.

Chronic coronary artery disease (CAD), including chronic stable angina, afflicts 16.5 million patients in the United States, with approximately 500,000 new patients diagnosed annually (1). Substantially more patients are evaluated for chest pain or other symptoms suggestive of CAD, but only a minority are ultimately diagnosed with CAD (2–4). Clinical evaluation of patients with suspected CAD is variable and includes diagnostic tests of varied accuracy, reproducibility, ease of use and potential for patient morbidity (5). Many patients undergoing invasive diagnostic coronary angiography do not have obstructive CAD, despite widespread availability of non-invasive diagnostic modalities (6).

No simple blood-based biomarker has been validated for diagnosis of obstructive CAD. Biomarkers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) have been associated with future cardiovascular event risk (7, 8), but there is no well-defined role for biomarkers in current assessment of patients with symptoms suggestive of CAD (9). We recently identified differential blood cell gene expression levels in patients with CAD (10) suggesting that CAD detection from a peripheral blood sample might be possible. The PREDICT multi-center study was designed to develop and validate blood-based gene expression tests for CAD , enrolling both diabetic and non-diabetic patients clinically indicated for invasive angiography. Differences in plaque morphology have been observed for CAD patients with and without diabetes (11, 12), and these differences were also reflected at the level of gene expression (Elashoff et al., submitted). Thus, we have derived an algorithm specifically relating non-diabetic patient CAD status to expression levels of 23 genes and sex-specific age functions (Elashoff et al., submitted).

Herein we report initial prospective validation of this gene expression algorithm for likelihood of obstructive CAD, defined as one or more coronary atherosclerotic lesions causing ≥50% luminal diameter stenosis, in non-diabetic patients with suspected CAD.

Methods

General Study Design and Study Population

Subjects were enrolled in PREDICT, a 39 center prospective study, between July 2007 and April 2009. The study was approved by institutional review boards at all centers and all patients gave written informed consent. Subjects referred for diagnostic coronary angiography were eligible with a history of chest pain, suspected anginal-equivalent symptoms, or a high risk of CAD, and no known prior myocardial infarction (MI), revascularization, or obstructive CAD. Subjects were ineligible if at catheterization, they had acute MI, high risk unstable angina, severe non-coronary heart disease (congestive heart failure, cardiomyopathy or valve disease), systemic infectious or inflammatory conditions, or were taking immunosuppressive or chemotherapeutic agents. Detailed eligibility criteria are in Appendix 2.

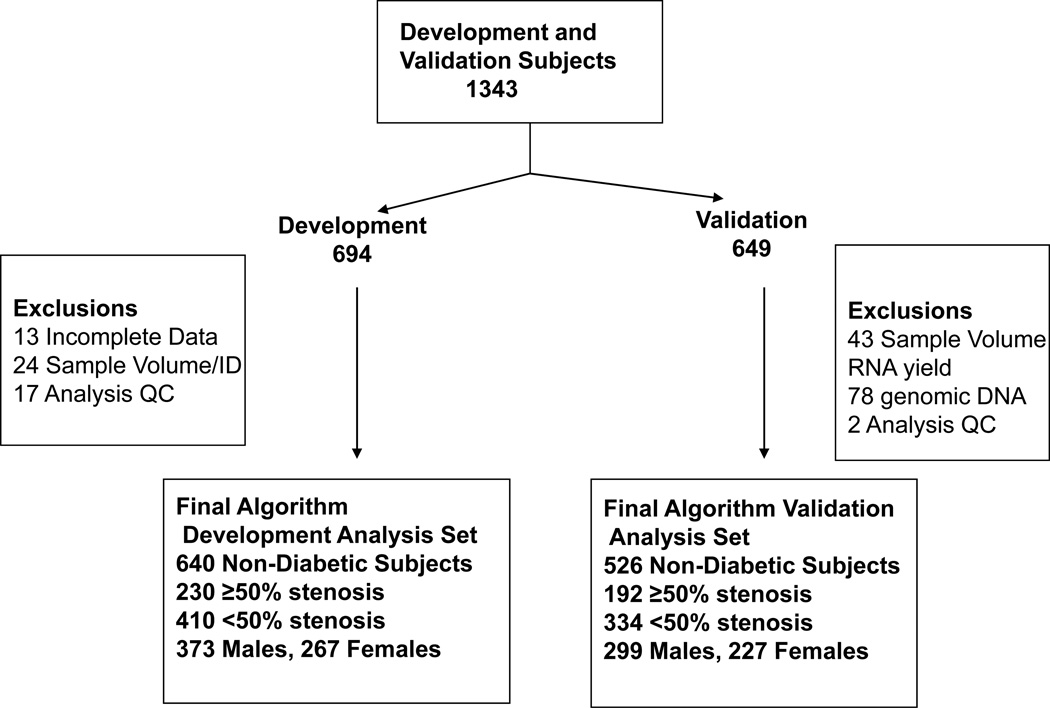

From 2186 enrolled subjects who met inclusion criteria, 606 diabetic patients were excluded, as this initial algorithm development and validation was focused on non-diabetics. The limitation to non-diabetic patients was based on the significant differences observed in CAD classifier gene sets dependent on diabetic status (Elashoff et al., submitted). Of the remaining 1580 patients, 5 had angiographic images unsuitable for QCA and 6 had unusable blood samples. For the remaining 1569 subjects, 226 were used in gene discovery; the remaining 1343 were divided into independent algorithm development and validation cohorts (Figure 1) sequentially based on date of enrollment.

Figure 1.

Allocation of Patients from the PREDICT trial for algorithm development and validation. From a total of 1569 subjects meeting the study inclusion/exclusion criteria 226 were used for gene discovery. The remaining 1343 were divided into independent cohorts for algorithm development (694) and validation (649) as shown; 94% of patients in these cohorts came from the same centers. For algorithm development a total of 640 patient samples were used; 54 were excluded due to incomplete data (13), inadequate blood volume (19), sex mismatch between experimental and clinical records (5), or statistical outlier assessment (17) (see Supplement for details). For the validation cohort a total of 123 samples were excluded based on: inadequate blood volume or RNA yield (43), significant contamination with genomic DNA (78), or prespecified statistical outlier assessment (2).

Clinical Evaluation and Quantitative Coronary Angiography

Pre-specified clinical data, including demographics, medications, clinical history and presentation, and myocardial perfusion imaging results were obtained by research study coordinators using standardized data collection methods and data verified by independent study monitors.

Coronary angiograms were analyzed by computer-assisted QCA. Specifically, clinically-indicated coronary angiograms performed according to site protocols were digitized, de-identified and analyzed with a validated quantitative protocol at Cardiovascular Research Foundation, New York, NY (13). Trained technicians, blinded to clinical and gene expression data, visually identified all lesions >10% diameter stenosis (DS) in vessels with diameter >1.5mm. Using the CMS Medis system, (Medis, version 7.1, Leiden, the Netherlands), technicians traced the vessel lumen across the lesion between the nearest proximal and distal non-diseased locations. The minimal lumen diameter (MLD), reference lumen diameter (RLD = average diameter of normal segments proximal and distal of lesion) and %DS (%DS = (1 - MLD/RLD) x 100) were then calculated.

The Diamond-Forrester (D–F) risk score, comprised of age, sex, and chest pain type, was prospectively chosen to evaluate the added value of the gene expression score to clinical factors (14). D–F classifications of chest pain type (typical angina, atypical angina and non-anginal chest pain) were assigned based on subject interviews as described (Appendix 2) (14), and D–F scores assigned (15). For this classification, subjects without chest pain symptoms were classified as non-anginal chest pain. Myocardial perfusion imaging was performed as clinically indicated, with local protocols, and interpreted by local readers with access to clinical data but not gene expression or catheterization data. Imaging results were defined as positive if ≥1 reversible or fixed defect consistent with obstructive CAD was reported. Indeterminate or intermediate defects were considered negative.

Obstructive CAD and Disease Group Definitions

Patients with obstructive CAD (N=192) were defined prospectively as subjects with ≥1 atherosclerotic plaque in a major coronary artery (≥1.5mm lumen diameter) causing ≥50% luminal diameter stenosis by QCA; non-obstructive CAD (N=334) had no lesions >50%.

Blood Samples

Prior to coronary angiography, venous blood samples were collected in PAXgene® RNA-preservation tubes. Samples were treated according to manufacturer’s instructions, then frozen at −20°C.

RNA Purification and RT-PCR

Automated RNA purification from whole blood samples using the Agencourt RNAdvance system, cDNA synthesis, and RT-PCR were performed as described (Elashoff et al., submitted). All PCR reactions were run in triplicate and median values used for analysis. Genomic DNA contamination was detected by comparison of expression values for splice-junction spanning and intronic ADORA3 assays normalized to values of TFCP2 and HNRPF. The RPS4Y1 assay was run as confirmation of sex for all patients; patients were excluded if there was an apparent mismatch with clinical data. Sample QC metrics and pass-fail criteria were pre-defined and applied prior to evaluation of results as described (Elashoff et al., submitted).

Statistical Methods

The analyses for comparison of demographic and clinical factors (Table 1) used SAS Version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA). All other analysis was performed using R Version 2.7 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Unless otherwise specified, univariate comparisons for continuous variables were done by t-test and categorical variables by Chi-square test. All reported p-values are two-sided.

Table 1.

Clinical and Demographic Characteristics of the Final Development and Validation Patient Sets1

| Development | Validation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Obstructive CAD2 (N=230) |

No Obstructive CAD (N=410) |

P-value | Obstructive CAD (N=192) |

No Obstructive CAD (N=334) |

P-value | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 63.7 (11.1) | 57.2 (11.8) | <0.001 | 64.7 (9.8) | 57.7 (11.7) | <0.001 | |

| Men, No. (%) | 180 (78.3%) | 193 (47.1%) | <0.001 | 134 (69.8%) | 165 (49.4%) | <0.001 | |

| Chest pain type | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Typical | 61 (26.5%) | 66 (16.1%) | 42 (21.9%) | 41 (12.3%) | |||

| Atypical | 28 (12.2%) | 56 (13.7%) | 42 (21.9%) | 49 (14.7%) | |||

| Non-cardiac | 47 (20.4%) | 137 (33.4%) | 50 (26.0%) | 134 (40.1%) | |||

| None | 91 (39.6%) | 143 (34.9%) | 58 (30.2%) | 109 (32.6%) | |||

| Blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg |

|||||||

| Systolic | 138 (17.7) | 133 (18.3) | <0.001 | 140 (17.7) | 132 (18.1) | <0.001 | |

| Diastolic | 79.7 (11.0) | 79.6 (11.7) | 0.94 | 79.2 (11.3) | 77.5 (10.9) | 0.086 | |

| Hypertension | 163 (70.9%) | 237 (57.8%) | 0.002 | 142 (74.0%) | 203 (60.8%) | 0.001 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 170 (73.9%) | 225 (54.9%) | <0.001 | 133 (69.3%) | 208 (62.3%) | 0.109 | |

| Curent smoking | 53 (23.2%) | 99 (24.3%) | 0.75 | 38 (19.8%) | 68 (20.4%) | 0.70 | |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 30.5 (6.0) | 31.0 (7.5) | 0.35 | 29.8 (5.5) | 31.3 (7.0) | 0.009 | |

| Ethnicity, White not Hispanic | 210 (91.3%) | 347 (84.6%) | 0.016 | 181 (94.3%) | 293 (87.7%) | 0.015 | |

| Clinical syndrome | |||||||

| Stable angina | 123 (53.5%) | 214 (52.2%) | 0.78 | 107 (55.7%) | 176 (52.7%) | 0.46 | |

| Unstable angina | 35 (15.2%) | 81 (19.8%) | 0.149 | 31 (16.1%) | 58 (17.4%) | 0.74 | |

| Asymptomatic, high risk | 72 (31.3%) | 113 (27.6%) | 0.32 | 53 (27.6%) | 100 (29.9%) | 0.60 | |

| Medications | |||||||

| Aspirin and salicylates | 153 (66.5%) | 232 (56.6%) | 0.029 | 139 (72.4%) | 205 (61.4%) | 0.012 | |

| Statins | 109 (47.4%) | 142 (34.6%) | 0.003 | 93 (48.4%) | 127 (38.0%) | 0.021 | |

| Beta blockers | 82 (35.7%) | 133 (32.4%) | 0.52 | 85 (44.3%) | 124 (37.1%) | 0.113 | |

| ACE inhibitors | 57 (24.8%) | 67 (16.3%) | 0.013 | 47 (24.5%) | 64 (19.2%) | 0.155 | |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | 29 (12.6%) | 39 (9.5%) | 0.26 | 18 (9.4%) | 34 (10.2%) | 0.76 | |

| Calcium channel blockers | 33 (14.3%) | 46 (11.2%) | 0.29 | 26 (13.5%) | 34 (10.2%) | 0.25 | |

| Antiplatelet agents | 27 (11.7%) | 21 (5.1%) | 0.003 | 16 (8.3%) | 17 (5.1%) | 0.142 | |

| Steroids, not systemic | 23 (10.0%) | 33 (8.0%) | 0.45 | 19 (9.9%) | 38 (11.4%) | 0.59 | |

| NSAIDS | 47 (20.4%) | 78 (19.0%) | 0.76 | 30 (15.6%) | 58 (17.4%) | 0.60 | |

Characteristics of the 640 subjects in the Algorithm Development and 526 subjects in the Validation sets. P values were calculated by t-tests for continuous variables and using chi-square tests for discrete variables. Significant p values in both sets are bolded and underlined and are bolded if significant in single sets.

Obstructive CAD is defined as >50% luminal stenosis in > 1 major vessel by QCA.

Gene Expression Algorithm Score

The gene expression algorithm was developed with obstructive CAD defined by QCA as ≥50% stenosis in >1 major coronary artery, corresponding approximately to 65–70% stenosis based on clinical angiographic read. The algorithm was locked prior to the validation study. Raw algorithm scores were computed from median expression values for the 23 algorithm genes, age and sex as described (Appendix 3) and used in all statistical analyses; scores were linearly transformed to a 0–40 scale for ease of reporting.

ROC Estimation and AUC Comparisons

The prospectively defined primary endpoint was the ROC curve area for algorithm score prediction of disease status. ROC curves were estimated for the a) gene expression algorithm score, b) the D–F risk score, c) a combined model of algorithm score and D–F risk score, d) Myocardial perfusion imaging, and e) a combined model of algorithm score and imaging. Standard methods (16) were used to estimate empirical ROC curves and associated AUCs and AUC standard errors. The Z-test was used to test AUCs versus random (AUC = .50).

Paired AUC comparisons: i) gene expression algorithm score plus D–F risk score vs D–F risk score, and ii) gene expression algorithm score plus myocardial perfusion imaging vs imaging alone; were performed by bootstrap. For each comparison, 10,000 bootstrap iterations were run, and observed AUC differences computed. The median bootstrapped AUC difference was used to estimate the AUC difference, and the p-value estimated using the empirical distribution of bootstrapped AUC differences (i.e. the observed quantile for 0 AUC difference in the empirical distribution).

Logistic Regression

A series of logistic regression models were fit with disease status as the binary dependent variable, and compared using a likelihood ratio test between nested models. Comparisons were: i) gene expression algorithm score plus D–F risk score versus D–F risk score alone; ii) gene expression algorithm score plus myocardial perfusion imaging versus imaging alone; iii) gene expression algorithm score versus the demographic component of the gene expression algorithm score; iv) algorithm score plus expanded clinical model vs expanded clinical model alone.

Correlation of Algorithm Score with Maximum Percent Stenosis

The correlation between algorithm score and percent maximum stenosis as continuous variables was assessed by linear regression. Stenosis values were grouped into five increasing categories (no measurable disease, 1–24%, 25–49% in ≥1 vessel, 1 vessel ≥50%, and >1 vessel ≥50%) and ANOVA was used to test for a linear trend in algorithm score across categories.

Expanded Clinical Model

An expanded clinical factor model was developed that incorporated the 11 clinical factors that showed univariate significance (p<.05) between obstructive CAD and no obstructive CAD patients in the development set (sex, age, chest pain type, race, statin, aspirin, anti-platelet, and ACE inhibitor use, systolic blood pressure, hypertension, and dyslipidemia). A logistic regression model was fit using disease status as the dependent variable and these 11 clinical factors as predictor variables. A subject’s ‘expanded clinical model score’ was the subject’s predicted value from this model.

Reclassification of Disease Status

Gene expression algorithm score and D–F risk scores were defined as low (0% to <20%), intermediate (≥20%,<50%), and high risk (≥50%) obstructive CAD likelihoods. Myocardial perfusion imaging results were classified as negative (no defect/possible fixed or reversible defect) or positive (fixed or reversible defect). For the D–F risk score analysis, a reclassified subject was defined as i) D–F intermediate risk to low or high algorithm score, ii) D–F high risk to algorithm low, or iii) D–F low risk to algorithm high. For the myocardial perfusion imaging analysis, a reclassified subject included i) imaging positive to algorithm score low risk, or ii) imaging negative to algorithm score high risk. Net reclassification improvement of the gene expression algorithm score (and associated p-value) compared to the D–F risk score, expanded clinical model, or myocardial perfusion imaging result was computed as described in Supplementary methods, with the definition of reclassifications shown above (17). Net reclassification improvement is a measure of reclassification clinical benefit, and is sensitive to both the fraction and accuracy of reclassification. Conceptually, it is the difference between a) the fraction of subjects who are reclassified correctly from an incorrect initial classification, and b) the fraction of subjects who are reclassified incorrectly from a correct initial classification.

Results

A total of 1343 non-diabetic patients from the PREDICT trial, enrolled between July 2007 and April 2009, were sequentially allocated to independent development (N= 694) and validation (N= 649) sets, as shown in Figure 1. The clinical characteristics of the development and validation sets were similar. Overall, subjects were 57% male, 37% had obstructive CAD and 26% had no detectable CAD. Significant clinical or demographic variables that were associated with obstructive CAD in both cohorts were increased age, male sex, chest pain type, elevated systolic blood pressure (all p< 0.001), hypertension (p=0.001), and white ethnicity (p=0.015), as summarized in Table 1.

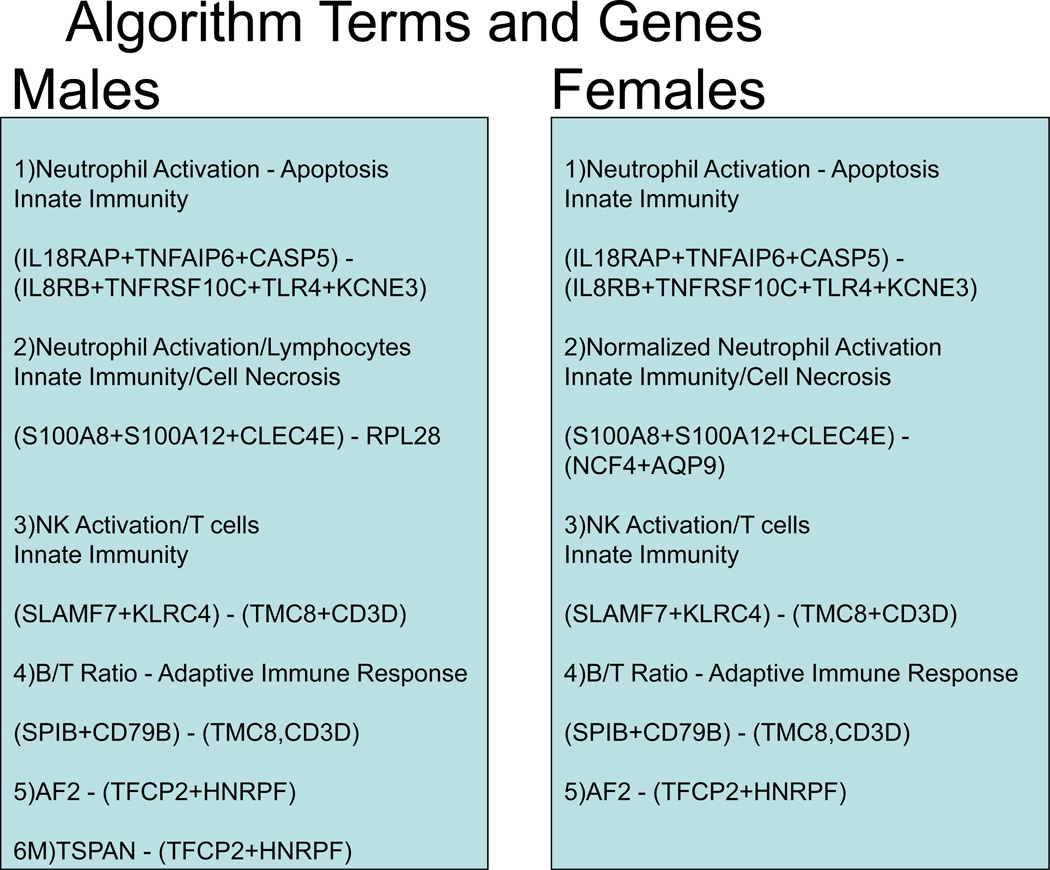

The final algorithm, consisting of 23 genes, grouped in the 6 terms, 4 sex-independent and 2 sex-specific, is shown schematically in Figure 2. The subsequent analyses are for the independent validation set only.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the Algorithm Structure and Genes. The algorithm consists of overlapping gene expression functions for males and females with a sex-specific linear age function for the former and a non-linear age function for the latter. For the gene expression components shown 16/23 genes in 4 terms are gender independent: term 1 – neutrophil activation and apoptosis, term 3 – NK cell activation to T cell ratio, term 4, B to T cell ratio, and term 5 –expression of gene AF289562 normalized to the mean of TFCP2 and HNRPF. In addition, Term 2 consists of 3 sex-independent neutrophil/innate immunity genes normalized in a sex-specific way to neutrophil gene expression (AQP9,NCF4) for females and to RPL28 (lymphocytes) in males. The final male specific term is the normalized expression of TSPAN16. The raw algorithm score is calculated from RT-PCR data as described (Appendix 3); for clinical use, the raw score was converted to a 0–40 scale by linear transformation.

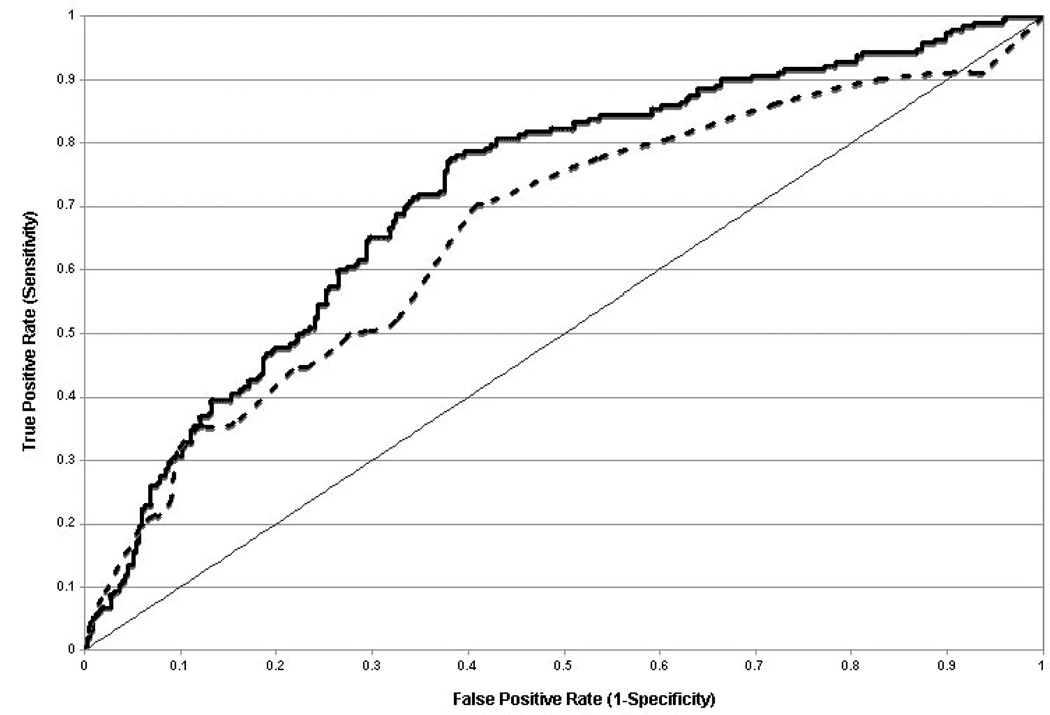

ROC Analysis

The primary endpoint AUC was 0.70 ±0.02, (p<0.001) with independently significant performance in male (0.66) and female subsets (0.65) (p <0.001 for each). For the primary clinical comparator of the Diamond-Forrester (D–F) risk score, ROC analysis showed a higher AUC for the algorithm score and D–F risk score combination, compared to D–F risk score alone (AUC 0.72 versus 0.66, p=0.003, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

ROC analysis of Validation Cohort Performance For Algorithm and Clinical Variables. Algorithm performance adds to Clinical Factors by Diamond-Forrester. Comparison of the combination of D–F score and algorithm score (heavy solid line) to D–F score alone (---) in ROC analysis is shown. The AUC=0.50 line (light solid line) is shown for reference. A total of 525 of the 526 validation cohort patients had information available to calculate D–F scores. The AUCs for the two ROC curves are 0.721 ± 0.023 and 0.663 ±0.025, p = 0.003.

The most prevalent form of non-invasive imaging in PREDICT was myocardial perfusion imaging. In the validation set 310 patients had clinically-indicated imaging performed, of which 72% were positive. Comparative ROC analysis showed an increased AUC for the combined algorithm score and myocardial perfusion imaging results versus imaging alone (AUC 0.70 versus 0.54, p <0.001).

Sensitivity, Specificity

We calculated the sensitivity and specificity for a score threshold of 14.75, corresponding to a disease likelihood of 20% from the validation set data. At this threshold, the sensitivity was 85% with a specificity of 43%, corresponding to negative and positive predictive values of 83% and 46%, respectively, with 33% of patients having scores below this value.

Association with Disease Severity

The algorithm score was moderately correlated with maximum percent stenosis (R=0.34, p<0.001), and the average algorithm score increased monotonically with increasing percent maximum stenosis (p< 0.001, Figure 4). The average scores for patients with and without obstructive CAD were 25 and 17, respectively.

Figure 4.

Dependence of Algorithm Score on % Maximum Stenosis in the Validation Cohort. The extent of disease for each patient was quantified by QCA maximum % stenosis and grouped into 5 categories: no measurable disease, 1–24%, 25–49% in ≥1 vessel, 1 vessel >50%, and >1 vessel >50%. The average algorithm score for each group is illustrated; error bars correspond to 95% confidence intervals. The complete relationship of algorithm score to obstructive CAD likelihood is depicted in Supplementary Figure 1; in Figure 4 scores of 10, 20, and 30 correspond to 15, 30, and 57% disease likelihood. A score of 15, corresponding to a 20% likelihood was used for dichotomous analyses as described in the text.

Reclassification

Reclassification may be a more clinically relevant measure of comparative predictor performance than standard measures such as AUC (18). Table 2A shows reclassification results for the gene expression algorithm compared to D–F risk score. In the validation cohort 27% of patients were reclassified and the net reclassification improvement for the gene expression algorithm score was 20% (p<0.001). The majority of reclassified subjects (75/141) were those with intermediate D–F risk scores. The gene expression algorithm reclassified 78% (75/96) of these patients, with 47 reclassified correctly to low or high risk versus 28 reclassified incorrectly; the incorrect reclassifications were predominantly to high risk (21/28). Additionally, 38 D–F low risk subjects (15%) were reclassified as high risk, and 28 high risk subjects (16%) reclassified as low risk.

Table 2A.

Reclassification analysis of Gene Expression Algorithm with Diamond-Forrester Clinical Model

| With Gene

Expression Algorithm |

Total | Reclassified % | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Int. | High | Lower | Higher | Total | ||

| D-F Low Risk | |||||||

| Total | 118 | 96 | 38 | 252 | 15.1 | 15.1 | |

| Obstructive CAD | 16 | 19 | 22 | 57 | 38.6 | 38.6 | |

| No Obstructive CAD | 102 | 77 | 16 | 195 | 8.2 | 8.2 | |

| Observed risk | 14% | 20% | 58% | 23% | -- | -- | |

| D-F Intermediate Risk | |||||||

| Total | 28 | 21 | 47 | 96 | 29.2 | 49.0 | 78.1 |

| Obstructive CAD | 7 | 11 | 26 | 44 | 15.9 | 59.1 | 75.0 |

| No Obstructive CAD | 21 | 10 | 21 | 52 | 40.4 | 40.4 | 80.8 |

| Observed risk | 25% | 52% | 55% | 46% | -- | -- | -- |

| D-F High Risk | |||||||

| Total | 28 | 60 | 89 | 177 | 15.8 | 15.8 | |

| Obstructive CAD | 6 | 29 | 56 | 91 | 6.6 | 6.6 | |

| No Obstructive CAD | 22 | 31 | 33 | 86 | 38.4 | 38.4 | |

| Observed risk | 21% | 48% | 63% | 51% | -- | -- | |

| Total Patients | 174 | 77 | 174 | 525 | |||

| Obstructive CAD | 29 | 59 | 104 | 192 | |||

| No Obstructive CAD | 145 | 118 | 70 | 333 | |||

| Observed risk | 17% | 33% | 60% | 37% | |||

| Table 2B. Reclassification

analysis of Gene Expression Algorithm with Expanded Clinical Model

(ECM) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Gene

Expression Algorithm |

Total | Reclassified % | |||||

| Low | Int | High | Lower | Higher | Total | ||

| ECM Low Risk | |||||||

| Total | 121 | 37 | 4 | 162 | 2.5 | 2.5 | |

| Obstructive CAD | 13 | 7 | 3 | 23 | 13.0 | 13.0 | |

| No Obstructive CAD | 108 | 30 | 1 | 139 | 0.8 | 0.8 | |

| Observed risk | 11% | 19% | 75% | 14% | |||

| ECM Int Risk | |||||||

| Total | 58 | 94 | 54 | 206 | 28.2 | 26.2 | 54.4 |

| Obstructive CAD | 16 | 26 | 32 | 74 | 21.6 | 43.2 | 64.8 |

| No Obstructive CAD | 42 | 68 | 22 | 132 | 31.8 | 16.7 | 48.5 |

| Observed risk | 28% | 28% | 59% | 36% | -- | ||

| ECM High Risk | |||||||

| Total | 2 | 41 | 115 | 158 | 1.3 | 1.3 | |

| Obstructive CAD | 0 | 24 | 71 | 63 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| No Obstructive CAD | 2 | 17 | 44 | 95 | 2.1 | 2.1 | |

| Observed risk | 0% | 59% | 62% | 60% 526 | |||

| Total | 181 | 172 | 173 | 526 | |||

| Obstructive CAD | 29 | 57 | 106 | 192 | |||

| No Obstructive CAD | 152 | 115 | 67 | 334 | |||

| Observed risk | 15% | 33% | 61% | 37% | |||

| Table 2C. Reclassification

analysis of Gene Expression Algorithm with Myocardial Perfusion Imaging

Results | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Gene

Expression Algorithm |

Total | Reclassified % | |||||

| Low | Int. | High | Lower | Higher | Total | ||

| Imaging Negative | |||||||

| Total | 41 | 31 | 15 | 87 | 17.4 | 17.4 | |

| Obstructive CAD | 7 | 8 | 7 | 22 | 31.8 | 31.8 | |

| No Obstructive CAD | 34 |

23 | 8 | 65 | 12.3 | 12.3 | |

| Observed risk | 17% | 26% |

47% | 25% | |||

| Imaging Positive | |||||||

| Total | 57 | 78 | 88 | 223 | 25.6 | 25.6 | |

| Obstructive CAD | 6 | 21 | 49 | 76 | 7.9 | 7.9 | |

| No Obstructive CAD | 51 | 57 | 39 | 147 | 34.7 | 34.7 | |

| Observed risk | 11% | 27% | 56% | 34% | |||

| Total | 98 | 109 | 103 | 310 | |||

| Obstructive CAD | 13 | 29 | 56 | 98 | |||

| No Obstructive CAD | 85 | 80 | 47 | 212 | |||

| Observed risk | 13% | 27% | 54% | 32% | |||

Risk categories: Low = 0–<20%, Intermediate = ≥20–50%, High = ≥50%.

Classification improved in 18.2% of disease patients and improved in 1.8% of non disease patients for a net reclassification improvement of 20.0% (p<.001)

Reclassification categories which are included in this calculation are bolded.

Risk categories: Low = 0–<20%, Intermediate = ≥20–50%, High = ≥50%.

Classification improved in 9.9% of disease patients and improved in 6.3% of non disease patients for a net reclassification improvement of 16.2% (p<.001)

Reclassification categories which are included in this calculation are bolded.

Risk categories: Low = 0–<20%, Intermediate = ≥20–50%, High = ≥50%.

Classification improved in 1.0% of disease patients and improved in 20.3% of non disease patients for a net reclassification improvement of 21.3% (p<.001)

Reclassification categories which are included in this calculation are bolded.

Classification by the expanded clinical model alone and with the addition of the gene expression score was also analyzed. A total of 22% of the patients were reclassified by the gene expression score and the net reclassification improvement was 16% (p<0.001, Table 2B). The vast majority of reclassified patients were intermediate risk by the expanded clinical model alone (112/118) and of these 74 were reclassified correctly and 38 incorrectly; incorrect reclassifications were preferentially to high risk (22/38). The AUC of the expanded clinical model alone was 0.732, and the AUC for the gene expression algorithm plus the full clinical model was 0.745 (p=0.089). For both clinical models overall, when reclassification errors occurred they were more likely to the high risk category, consistent with the gene expression algorithm having a higher negative predictive value than positive predictive value at this threshold.

A comparison of myocardial perfusion imaging versus gene expression algorithm results yielded a net reclassification improvement of 21% (p<0.001, Table 2C).

Discussion

This study prospectively validates in non-diabetic patients, clinically referred for invasive angiography, a non-invasive test for obstructive CAD defined by QCA, that is based on gene expression in circulating whole blood cells, age and gender. This study extends our previous work on correlation of gene expression changes in blood with CAD (10) to prospective validation of a classifier for non-diabetic patients with obstructive CAD by ROC analysis. The test yields a numeric score (0–40) with higher scores corresponding to higher likelihood of obstructive CAD and higher maximum percent stenosis (Supplementary Figure 1).

The gene expression score increases classification accuracy by ROC analysis compared to clinical factors (Diamond-Forrester), which has been challenging to achieve with genetic or biomarker approaches, at least for cardiovascular event prognosis (19, 20). It has also been suggested that reclassification of patient clinical risk or status, as captured by net reclassification improvement, may be a more appropriate measure than comparative ROC analysis for evaluating potential biomarkers (17, 18). The gene expression algorithm score improves the accuracy of clinical CAD assessment as shown by a net reclassification improvement of 20% relative to D–F score and 16% relative to an expanded clinical model (Tables 2A,B). For the most prevalent non-invasive test, myocardial perfusion imaging, the improvement was 21% (Table 2C), although these results are likely exaggerated in this angiographically referred population. The contributions to the reclassification improvements were 2%, 20%, and 6% from subjects without obstructive CAD and 18%, 1%, and 10% for subjects with obstructive CAD for Diamond-Forrester, myocardial perfusion, and the expanded clinical model, respectively. Overall, independent of imaging result or clinical risk category, increasing gene expression score leads to monotonically increased obstructive CAD risk. This is at least partially a reflection of the correlation of gene expression score with the extent of CAD, as measured here by maximum percent stenosis.

This gene-expression test could have clinical advantages over current non-invasive CAD diagnostic modalities since it requires only a standard venous blood draw, and no need for radiation, intravenous contrast, or physiologic and pharmacologic stressors. In the validation cohort, for example, only 37% of patients undergoing invasive angiography had obstructive CAD and the rate was particularly low in women (26%). A similar overall rate of obstructive CAD in an angiography registry for patients without prior known CAD was recently reported, with little sensitivity to the exact definition of obstructive CAD (6). The gene-expression test described here identified a low-likelihood (<20%) of obstructive CAD in 33% of patients referred for invasive angiography, although the majority of these patients were also at low risk by clinical factor analysis (Table 2A). After excluding low risk D–F score patients, an additional 11% (56/525) were classified as low risk by the gene expression algorithm. These patients had an observed risk of 23% as compared to 49% overall for the D–F intermediate and high risks groups.

Relationship of the Gene Expression Algorithm to Prior Studies

The algorithm consists of two types of terms: sex-specific age functions of obstructive CAD likelihood and gene expression terms that reflect changes in gene expression within a cell type, changes in cell type proportions, or a combination of the two. The sex-specific differences in cardiovascular risk and presentation are well known and largely reflect reduced risk in pre-menopausal women (21, 22). The gene expression terms appear to reflect an innate immune response, as illustrated by the preponderance of up-regulated genes preferentially expressed in granulocytes/neutrophils and natural killer cells. This is at first view surprising as the cell types most consistently found in atherosclerotic plaque are monocytes and T-cells. However, roles for a variety of circulating cells and both innate and adaptive immunity in atherosclerosis have been described (23, 24).

The significance of changes in specific cell-type distributions in whole blood with respect to cardiovascular events has been investigated in both angiographically evaluated and post-PCI populations, with neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio being the most significant predictor (25, 26). Algorithm Term 2 consists of three genes expressed predominantly in granulocytes/neutrophils (27, 28). In men term 2 is normalized to RPL28, one of the ribosomal proteins, which are preferentially expressed in lymphocytes (27). Thus, this term reflects the neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio in men. In women, this term is normalized to genes highly correlated with neutrophil count, rather than RPL28, consistent with reduced significance of neutrophil count in predicting CAD in women (29). The common upregulated genes in term 2 (S100A8, S100A12, and CLEC4E) are highly correlated with the 11 gene signature we described previously, including the most significant gene from that study, S100A12 (10).

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. First, the gene expression changes observed likely represent disease-correlated effects or disease-responsive effects, and not a causal role in disease pathogenesis. These changes may reflect overall disease burden, the inflammatory activity of the patient, or both, and not a specific level of stenosis.

From a clinical perspective the validation study patient population is limited to a non-diabetic US-based population with chest pain or asymptomatic high-risk presentation who have been referred for invasive angiography, and does not address test performance in low-risk, asymptomatic individuals, patients with high risk unstable angina or acute MI or diabetics. Further studies will be needed to refine the test negative predictive value, and to examine directly test performance relative to non-invasive imaging modalities as the current population of patients clinically referred for angiography likely over-estimates disease prevalence. In particular, the present myocardial perfusion imaging comparisons are affected by referral bias, especially for the negative patients. Thus, the clinical utility of the gene expression algorithm will need additional validation in lower risk populations.

The maximum stenosis endpoint is anatomical rather than functional; correlation to fractional flow reserve might be more informative. In addition, the influence of non-coronary atherosclerosis on the test score has not been determined, although this is less likely to have impact in a chest-pain population.

Finally, prognosis of future cardiac events has not been evaluated. While coronary inflammation is widely accepted as a cause of plaque progression, rupture, and MI (30, 31), a possible relationship between the test result and future events remains unexplored. It is intriguing that some of the algorithm terms may reflect cell-type ratios that have been implicated in major coronary event prediction (25, 32).

From a molecular and cellular perspective, defining disease risk from circulating blood cell RNA levels and reported age and gender only partially reflects the molecular changes in coronary atherosclerosis observable in blood. Analysis of protein or lipid biomarker levels, secreted by smooth muscle, endothelial, and inflammatory cells in the diseased vessel wall, or other sources of inflammatory markers (such as liver) might yield complementary information (33). In addition, gene expression based measures of physiological rather than chronological age may yield improved predictive information (34).

Conclusions

We describe the prospective multi-center validation of a peripheral blood-based gene expression test to determine the likelihood of obstructive CAD in non-diabetic patients as defined by invasive angiography. This test provides a statistically significant but modest improvement in patient classification as compared to clinical factors and non-invasive imaging as defined by patient CAD status. Further studies are needed to define the performance characteristics and clinical utility in populations with lower pre-test probability.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. An independent statistical analysis was completed by Dr. Nicholas Schork at the Scripps Research Institute without any funding from the sponsor. The primary endpoint and secondary endpoints were prospectively defined and transmitted for external statistical analysis prior to completion of the validation study data set.

The authors gratefully acknowledge all the patients who provided samples for the PREDICT study as well as the study site research coordinators and those who contributed to patient recruitment, clinical data acquisition and verification, validation study experimental work and data analysis. We thank Michael Walker, Richard Lawn, and Fred Cohen for helpful suggestions on the manuscript.

This work was funded by CardioDx, Inc. SR, MRE, PB, SED, JAW, AJS, and MY are employees of CardioDx, Inc and have equity interests and/or stock options in CardioDx. WGT and PTS are former employees have equity or stock options in CardioDx. SR, MRE, JAW, AJS, PB and WGT have filed patent applications on behalf of CardioDx, Inc. WEK reports research support from CardioDx. NJS, MW, and EJT are supported in part by the Scripps Translational Science Institute Clinical Translational Science Award (NIHUL1RR025774). AL reports funding from CardioDx to complete the QCA studies reported herein.

Footnotes

“This is the prepublication, author-produced version of a manuscript accepted for publication in Annals of Internal Medicine. This version does not include post-acceptance editing and formatting. The American College of Physicians, the publisher of Annals of Internal Medicine, is not responsible for the content or presentation of the author-produced accepted version of the manuscript or any version that a third party derives from it. Readers who wish to access the definitive published version of this manuscript and any ancillary material related to this manuscript (e.g., correspondence, corrections, editorials, linked articles) should go to www.annals.org or to the print issue in which the article appears. Those who cite this manuscript should cite the published version, as it is the official version of record.”

RSS, SZ, RW, JM, and NT report no conflicts of interest with respect to the contents of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Steven Rosenberg, CardioDx, Inc., 2500 Faber Place, Palo Alto, CA 94303.

Michael R. Elashoff, CardioDx, Inc., 2500 Faber Place, Palo Alto, CA 94303.

Philip Beineke, CardioDx, Inc., 2500 Faber Place, Palo Alto, CA 94303.

Susan E. Daniels, CardioDx, Inc., 2500 Faber Place, Palo Alto, CA 94303.

James A. Wingrove, CardioDx, Inc., 2500 Faber Place, Palo Alto, CA 94303.

Whittemore G. Tingley, Division of Cardiology, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA 94143.

Philip T. Sager, Gilead Sciences, Inc. 3172 Porter Drive, Palo Alto, CA 94304.

William E. Kraus, Duke Center for Living, 3475 Erwin Road, Box 3022, Rm. 254, Aesthetics Building, Durham, NC 27705.

L. Kristin Newby, Duke Clinical Research Institute, P.O. Box 17969, Durham, NC 27715-7969.

Robert S. Schwartz, Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation, Abbott Northwestern Hospital, 920 E. 28 Street, Suite 620, Minneapolis, MN 55407.

Szilard Voros, Piedmont Heart Institute, 95 Collier Road, NW Suite 2035, Atlanta, GA 30309.

Stephen Ellis, The Cleveland Clinic, 9500 Euclid Avenue, F25, Cleveland, OH 44195.

Naeem Tahirkheli, 4221 S. Western, Suite 4000, Oklahoma City, OK 73109.

Ron Waksman, Cardiovascular Research Institute, Medstar Research Institute, Washington Hospital Center, 110 Irving St. NW, Suite 6B-5, Washington, DC 20010.

John McPherson, 1215 21 Ave S. MCE 5th Fl S. Tower, Nashville, TN 37232.

Alexandra Lansky, Cardiovascular Research Foundation, 111 East 59th Street, New York, NY 10022-1122.

Nicholas J. Schork, Scripps Translational Science Institute, 3344 North Torrey Pines Court, Suite 300, La Jolla, CA 92037.

Mary E. Winn, Scripps Translational Science Institute, 3344 North Torrey Pines Court, Suite 300, La Jolla, CA 92037

Eric J. Topol, Scripps Translational Science Institute, 3344 North Torrey Pines Court, Suite 300, La Jolla, CA 92037.

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119(3):480–486. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martina B, Bucheli B, Stotz M, Battegay E, Gyr N. First Clinical Judgment by Primary Care Physicians Distinguishes Well between Nonorganic and Organic Causes of Abdominal or Chest Pain. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:459–465. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00083.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Svavarsdottir AE, Jonasson MR, Gudmundsson GH, Fjeldsted K. Chest pain in family practice. Diagnosis and long-term outcome in a community setting. Can Fam Physician. 1996;42:1122–1128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klinkman MS, Stevens D, Gorenflo DW. Episodes of care for chest pain: a preliminary report from MIRNET. Michigan Research Network. J Fam Pract. 1994;38(4):345–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibbons RJ, Abrams J, Chatterjee K, et al. ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for the management of patients with chronic stable angina--summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients With Chronic Stable Angina) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(1):159–168. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02848-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel MR, Peterson ED, Dai D, et al. Low diagnostic yield of elective coronary angiography. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(10):886–895. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ridker PM, Paynter NP, Rifai N, Gaziano JM, Cook NR. C-reactive protein and parental history improve global cardiovascular risk prediction: the Reynolds Risk Score for men. Circulation. 2008;118(22):2243–2251. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.814251. 4p following 2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melander O, Newton-Cheh C, Almgren P, et al. Novel and conventional biomarkers for prediction of incident cardiovascular events in the community. JAMA. 2009;302(1):49–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zebrack JS, Muhlestein JB, Horne BD, Anderson JL. C-reactive protein and angiographic coronary artery disease: independent and additive predictors of risk in subjects with angina. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(4):632–637. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01804-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wingrove JA, Daniels SE, Sehnert AJ, et al. Correlation of Peripheral-Blood Gene Expression With the Extent of Coronary Artery Stenosis. Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics. 2008;1(1):31–38. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.782730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burke AP, Kolodgie FD, Zieske A, et al. Morphologic findings of coronary atherosclerotic plaques in diabetics: a postmortem study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(7):1266–1271. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000131783.74034.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ibebuogu UN, Nasir K, Gopal A, et al. Comparison of atherosclerotic plaque burden and composition between diabetic and non diabetic patients by non invasive CT angiography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;25(7):717–723. doi: 10.1007/s10554-009-9483-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lansky AJ, Popma JJ. Qualitative and quantitative angiography. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1998 Text Book of Interventional Cardiology; [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diamond GA, Forrester JS. Analysis of probability as an aid in the clinical diagnosis of coronary-artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1979;300(24):1350–1358. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197906143002402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaitman BR, Bourassa MG, Davis K, et al. Angiographic prevalence of high-risk coronary artery disease in patient subsets (CASS) Circulation. 1981;64(2):360–367. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.64.2.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newson R. Confidence intervals for rank statistics: Somers' D and extensions. Stata Journal. 2006;6:309–334. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Sr, D’Agostino RB, Jr, Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008;27(2):157–172. doi: 10.1002/sim.2929. discussion 207-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cook NR, Ridker PM. Advances in measuring the effect of individual predictors of cardiovascular risk: the role of reclassification measures. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(11):795–802. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-11-200906020-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paynter NP, Chasman DI, Buring JE, Shiffman D, Cook NR, Ridker PM. Cardiovascular disease risk prediction with and without knowledge of genetic variation at chromosome 9p21.3. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(2):65–72. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-2-200901200-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson PW, Pencina M, Jacques P, Selhub J, D’Agostino R, Sr, O’Donnell CJ. C-reactive protein and reclassification of cardiovascular risk in the Framingham Heart Study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2008;1(2):92–97. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.831198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gopalakrishnan P, Ragland MM, Tak T. Gender differences in coronary artery disease: review of diagnostic challenges and current treatment. Postgrad Med. 2009;121(2):60–68. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2009.03.1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stangl V, Witzel V, Baumann G, Stangl K. Current diagnostic concepts to detect coronary artery disease in women. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(6):707–717. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanderlaan PA. Thematic review series: the immune system and atherogenesis. The unusual suspects:an overview of the minor leukocyte populations in atherosclerosis. J Lipid Res. 2005;46(5):829–838. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R500003-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Packard RR, Lichtman AH, Libby P. Innate and adaptive immunity in atherosclerosis. Semin Immunopathol. 2009;31(1):5–22. doi: 10.1007/s00281-009-0153-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horne BD, Anderson JL, John JM, et al. Which white blood cell subtypes predict increased cardiovascular risk? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(10):1638–1643. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duffy BK, Gurm HS, Rajagopal V, Gupta R, Ellis SG, Bhatt DL. Usefulness of an elevated neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in predicting long-term mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97(7):993–996. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palmer C, Diehn M, Alizadeh AA, Brown PO. Cell-type specific gene expression profiles of leukocytes in human peripheral blood. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:115. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watkins NA, Gusnanto A, de Bono B, et al. A HaemAtlas: characterizing gene expression in differentiated human blood cells. Blood. 2009;113(19):e1–e9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-162958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rana JS, Boekholdt SM, Ridker PM, et al. Differential leucocyte count and the risk of future coronary artery disease in healthy men and women: the EPIC-Norfolk Prospective Population Study. J Intern Med. 2007;262(6):678–689. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Libby P, Theroux P. Pathophysiology of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2005;111(25):3481–3488. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.537878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Packard RR, Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis: from vascular biology to biomarker discovery and risk prediction. Clin Chem. 2008;54(1):24–38. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.097360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dragu R, Huri S, Zuckerman R, et al. Predictive value of white blood cell subtypes for long-term outcome following myocardial infarction. Atherosclerosis. 2008;196(1):405–412. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ardigo D, Assimes TL, Fortmann SP, et al. Circulating chemokines accurately identify individuals with clinically significant atherosclerotic heart disease. Physiol Genomics. 2007;31(3):402–409. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00104.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hong MG, Myers AJ, Magnusson PK, Prince JA. Transcriptome-wide assessment of human brain and lymphocyte senescence. PLoS One. 2008;3(8):e3024. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.