Abstract

Primary care practitioners (PCPs) have been encouraged to screen all adults for obesity and to offer behavioral weight loss counseling to affected individuals. However, there is limited research and guidance on how to provide such intervention in primary care settings. This led the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in 2005 to issue a request for applications to investigate the management of obesity in routine clinical care. Three institutions were funded under a cooperative agreement to undertake the Practice-based Opportunities for Weight Reduction (POWER) trials. The present article reviews selected randomized controlled trials, published prior to the initiation of POWER, and then provides a detailed overview of the rationale, methods, and results of the POWER trial conducted at the University of Pennsylvania (POWER-UP). POWER-UP’s findings are briefly compared with those from the two other POWER Trials, conducted at Johns Hopkins University and Harvard University/Washington University. The methods of delivering behavioral weight loss counseling differed markedly across the three trials, as captured by an algorithm presented in the article. Delivery methods ranged from having medical assistants and PCPs from the practices provide counseling to using a commercially-available call center, coordinated with an interactive web-site. Evaluation of the efficacy of primary care-based weight loss interventions must be considered in light of costs, as discussed in relation to the recent treatment model proposed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Keywords: weight loss, behavioral weight loss counseling, lifestyle modification, primary care practice, cost-effectiveness

In 2003, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended that primary care practitioners (PCPs) screen all adults for obesity and offer behavioral interventions and intensive counseling to affected individuals.1 This recommendation came at a time when fewer than half of PCPs were found to discuss weight management with their patients,2 and there were no evidence-based guidelines for implementing behavioral weight loss counseling in primary care settings. In 2005, in response to this gap in practice and research, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) issued a request for applications (RFA) to investigate the management of obesity in routine clinical practice.3 Three institutions were funded by a cooperative agreement (UO1), which allowed each to design and implement its own randomized controlled trial (RCT) of a novel weight loss intervention. However, investigators were encouraged to coordinate their trials, wherever possible, by developing common eligibility criteria and outcome measures. They met regularly (in person or by teleconference) to discuss these and other issues, including participant recruitment and retention, intervention development and implementation, statistical analyses, and dissemination.

Collectively, the three trials were referred to as Practice-based Opportunities for Weight Reduction (POWER).3 The POWER trial implemented at the University of Pennsylvania (UP) was known as POWER-UP,4 the study conducted at Harvard University (with coordination from Washington University) was referred to as Be Fit, Be Well,5 while the trial at Johns Hopkins University was named POWER Hopkins.6 The commonalities and differences among the three trials have been described previously.3 Investigators at each site also have published results for their primary outcome (i.e., weight loss at 2 years) in separate articles.4–6

The present article (with the five others in this supplement) provides further information about the development, implementation, and efficacy of the weight loss interventions tested in the POWER-UP trial at the University of Pennsylvania.4 The review begins by summarizing the current status of lifestyle modification for obesity, examines prior efforts to provide such treatment in primary care practice, and then describes the methods and interventions used in the POWER-UP trial. The treatment approach and results of POWER-UP are briefly compared with those from Be Fit, Be Well and POWER Hopkins. The paper concludes by discussing POWER-UP’s results in the context of recent recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force7 and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.8

Current Status of Lifestyle Modification for Obesity

Lifestyle modification for obesity – consisting of a combination of diet, physical activity, and behavior therapy – is considered the cornerstone of weight management for overweight and obese adults.9,10 This approach uses behavioral strategies, such as goal setting and record keeping, to help individuals reduce their calorie intake by approximately 500–1000 kcal/day, principally by reducing their portion sizes, snacking, and consumption of high-fat, high sugar foods.10–12 Caloric restriction is combined with recommendations to exercise (e.g., brisk walking) for at least 30 minutes/day most days of the week (i.e., 180 minutes/week).13 In academic medical centers, behavioral treatment typically is delivered in weekly group or individual sessions that are led by registered dietitians, psychologists, exercise specialists, and other counseling professionals.11

Weekly group lifestyle interventions of 16 to 26 weeks, as exemplified by the Diabetes Prevention Program12 and the Look AHEAD study,14,15 induce a mean weight loss of approximately 7–10% of initial weight during this time. Weight losses are associated with improvements in cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors,16 including prevention of type 2 diabetes in at-risk individuals.12 Patients are vulnerable to weight regain following the termination of treatment, but it can be limited by the provision of twice-monthly or monthly weight loss maintenance sessions.11 Participants in the Look AHEAD study, for example, maintained a 4.7% reduction in initial weight at 4 years with the support of twice monthly maintenance contacts.17

Lifestyle modification increasingly is being delivered by the Internet (rather than in face-to-face meetings), given its convenience to participants.18–20 Web-based programs allow dieters to record their weight, food intake, and physical activity on-line and to receive colorful graphic displays of their progress. The most successful programs also include personalized feedback from an interventionist.19–20 Despite their greater convenience, Internet intervention generally produce mean weight losses about one-third smaller than traditional face-to-face programs.20 By contrast, preliminary studies suggest that interventions delivered in individual or group phone calls achieve losses roughly equal to face-to-face interventions.21–23

Lifestyle Modification in Primary Care Practice

Only a handful of RCTs had been conducted on the behavioral management of obesity in primary care practice when NHLBI funded the POWER Trials in 2006. The absence of trials was not surprising, given that PCPs lacked the time, training, and incentive (i.e., insurance reimbursement for obesity management) required to deliver a comprehensive lifestyle intervention, as described above.24 As shown in Table 1, three trials in which PCPs provided brief behavioral counseling to obese patients in their practices produced mean losses of less than 2.5 kg at 6 to 12 months.25–27 The modest losses were probably attributable to the limited number of treatment visits provided, which ranged from an average of 3.6 to 9.7 over 6 to 12 months. Martin et al. conducted an exemplary trial, which randomly assigned low-income women to: 1) usual care, consisting of as-needed medical treatment; or 2) a 6-month weight loss intervention, consisting of brief, monthly PCP counseling sessions.26 Counseling visits lasted approximately 15 minutes and included personalized recommendations for changing diet and physical activity. At month 6, patients who received PCP counseling lost a mean of 1.4 kg, compared with a gain of 0.3 kg for usual care (p = 0.01).

Table 1.

Studies of brief primary care provider (PCP) counseling, provided alone or with pharmacotherapy

| Study | N | Interventions | Number of treatment visits | Months of post-randomization follow-up | Weight change at month 6, kg | Weight change at follow-up, kg | ≥5% loss of initial weight at follow-up, % of subjects | Attrition at follow-up, %* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brief PCP Counseling | ||||||||

| Cohen et al.25 | 30 | 1) Usual care | 5.2 | 12 | +0.6 ± 0.6a | +1.3 ± 0.8a | - | Not stated |

| 2) Usual care + PCP counseling | 9.7 | 12 | −1.8 ± 0.9b | −0.9 ± 1.0a | - | |||

| Martin et al.26 | 144 | 1) Usual care | 0 | 6 | +0.3 ± 0.4a | +0.3 ± 0.4a | 5.2 | 21 |

| 2) Usual care + PCP counseling | 6 | 6 | −1.4 ± 0.5b | −1.4 ± 0.5b | 12.5 | 32 | ||

| Ockene et al.27** | 1162 | 1) Usual care | 3.4 | 12 | - | 0.0a | - | 42 |

| 2) PCP training | 3.1 | 12 | - | −1.0ab | - | 42 | ||

| 3) PCP training + office support | 3.6 | 12 | - | −2.3b | - | 37 | ||

| Brief PCP Counseling + Pharmacotherapy | ||||||||

| Hauptman et al.31 | 635 | 1) PCP guidance + placebo | 10 | 24 | −4.7 ± 0.6a | −1.7 ± 0.6a | 24.1a | 57 |

| 2) PCP guidance + orlistat, 60 mg TID | 10 | 24 | −6.9 ± 0.6b | −4.5 ± 0.6b | 33.8b | 44 | ||

| 3) PCP guidance + orlistat, 120 mg TID | 10 | 24 | −8.0 ± 0.6b | −5.0 ± 0.7b | 34.3b | 44 | ||

| Wadden et al.34† | 106 | 1) Sibutramine, 10–15 mg daily | 8 | 12 | - | −5.0 ± 1.0a | 42 | 18 |

| 2) Sibutramine, 10–15 mg daily + PCP counseling | 8 | 12 | - | −7.5 ± 1.1a | 56 | 19 | ||

Note: Values shown for weight change are mean ± SEM. For each study, under “weight change” (at month 6 and at follow-up) and “ ≥5% loss of initial weight at follow-up,” values labeled with different letters (a,b) are significantly different from each other at p < 0.05; TID = three times per day.

Attrition is defined as the percentage of participants who did not contribute an in-person weight at the end of the study. An intention-to-treat analysis was used in most studies, except for two that used a completers’ analysis.25,27

This study did not report the standard deviations or standard errors of weight loss.

This study included two additional groups, both of which included intensive group lifestyle modification. The results of these groups are not displayed here.

Increasing the frequency of PCP lifestyle counseling to weekly or bi-weekly visits, as provided in group lifestyle modification programs, potentially could have increased mean weight losses in the study by Martin et al.26 However, as noted, PCPs may not have the capacity to provide such frequent treatment, given the already pressing demands on their schedules. Adding weight loss medication to PCP counseling offers another option for increasing weight loss, without taxing practitioners’ resources.

Adding Pharmacotherapy to PCP-Delivered Lifestyle Counseling

Trials conducted in academic medical centers have shown that adding weight loss medication to lifestyle counseling increases weight loss, compared with counseling alone.28–30 Medication is thought to facilitate adherence to diet and calorie recommendations by reducing hunger (i.e., the drive to eat), increasing satiation (i.e., to terminate eating), or blocking the absorption of nutrients (e.g., fat).28 Two RCTs, summarized in Table 1, examined the effectiveness of lifestyle counseling plus pharmacotherapy, provided by PCPs, as part of interventions that modeled brief office visits in primary care. Hauptman et al.31 studied the effectiveness of orlistat (a gastric and pancreatic lipase inhibitor) in primary care patients randomly assigned to: 1) placebo; 2) 60 mg of orlistat TID; or 3) 120 mg of orlistat TID. All patients were prescribed a reduced-calorie diet during year 1 and a weight-maintenance diet during year 2. They also received brief dietary guidance from their PCPs, along with educational videotapes and printed materials. As shown in Table 1, weight losses at month 24 were 1.7, 4.5, and 5.0 kg for the three groups, respectively (p = 0.001 for both orlistat groups compared to placebo).

Wadden et al.28 assessed the effects of sibutramine (a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor) and lifestyle counseling. Patients were randomly assigned to: 1) sibutramine (10–15 mg daily), accompanied by 8 brief PCP visits over 12 months, limited to monitoring blood pressure and pulse; or 2) sibutramine plus brief PCP lifestyle counseling, provided during the same 8 brief visits. Patients in the latter group completed homework assignments from the LEARN program,32 including daily food and activity records. Patients who received sibutramine plus PCP counseling lost significantly more weight at week 18 than did those who received sibutramine alone (8.4 vs. 6.2 kg, p = 0.05). At month 12, differences between groups were similar (7.5 vs. 5.0 kg) but no longer statistically significant.

These two studies, with the three others reviewed in Table 1, suggest that combining medication with brief PCP counseling is more likely to help participants achieve clinically meaningful weight loss (≥5% of initial weight) than is the provision of PCP counseling alone. This hypothesis remains to be tested using two new FDA-approved medications – lorcaserin33 and the combination of phentermine and topirimate.34 Many obese individuals, however, as well as their practitioners, may be unwilling to use weight loss medications because of concerns about their high costs (which frequently are not covered by insurance plans) and potential adverse health effects. Concerns about safety were underscored when sibutramine was removed from the market in 2010 because of findings that it increased the risk of CVD events in obese patients with a prior history of CVD.35 Thus, new methods, which do not rely solely on PCPs, are needed for delivering behavioral weight loss counseling to obese patients in primary care.

Use of Auxiliary Health Providers in Primary Care

Non-physician staff, known as auxiliary health providers (AHPs), provide an option for delivering such counseling in primary care. AHPs may have more time than PCPs to provide such care and at a lower cost. Most studies of AHPs have examined individuals with advanced training, such as nurses and pharmacists. However, trials have explored the use of medical assistants (MAs) and licensed practical nurses (LPNs) to provide behavioral counseling to facilitate compliance with mammography screening36 and smoking cessation.37

Prior to NHLBI’s issuing its weight management RFA, Tsai and Wadden developed a treatment model in which MAs were trained to serve as lifestyle interventionists (i.e., coaches), who worked in conjunction with PCPs.38 With this approach, called collaborative obesity care, PCPs were responsible for assessing and treating patients’ weight-related co-morbidities (e.g., hypertension, type 2 diabetes) using appropriate pharmacologic therapies. In a pilot study of 50 patients recruited from two primary care practices, participants were randomly assigned to: 1) quarterly PCP visits (which included the provision of printed weight loss materials); or 2) brief lifestyle counseling, which included quarterly PCP visits, along with eight brief (15–20 minutes) counseling sessions with a trained MA (who worked in the practices). The lifestyle intervention was adapted from the DPP.12 At month 6, participants in the brief lifestyle counseling and control groups lost 4.4 kg and 0.9 kg, respectively (p < 0.001). In addition, 48% of participants in the former group lost 5% or more of their weight, compared to 0% in the control group (p = 0.0001). However, at 1-year assessment, there were no significant differences between groups as a result of weight regain following the termination of MA coaching visits at month 6. This finding suggested that brief lifestyle counseling would need to be continued long term to facilitate the maintenance of lost weight.

The POWER-UP Study

The POWER-UP trial provided our research team an opportunity to extend its findings from the prior pilot investigation38 by increasing the study’s sample size and the duration of treatment. The trial also allowed for the addition of a third treatment arm, designed to induce greater weight loss by providing either meal replacements or FDA-approved medications. An overview of the study’s three treatment interventions is provided, following a brief description of the study design. This information has been published previously,4,39 but is summarized here to facilitate readers’ understanding of the five other empirical papers in this supplement.

Study Design

POWER-UP was a 2-year RCT in which 390 obese participants with at least two components of the metabolic syndrome were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: 1) Usual Care; 2) Brief Lifestyle Counseling; or 3) Enhanced Brief Lifestyle Counseling. Participants were recruited (and treated) at six primary care practices (in the greater Philadelphia area) owned by the University of Pennsylvania Health System. To be eligible, participants had to be established patients in the practice, ≥ 21 years of age, and have a BMI of 30 to 50 kg/m2 and at least two of five criteria for the metabolic syndrome. (Additional inclusion/exclusion criteria have been described elsewhere.4,39)

The 390 participants randomized to treatment had a mean age of 51.5 ± 11.5 yr, weight of 107.6 ± 18.3 kg, and BMI of 38.5 ± 4.7 kg/m2. Participants included 79 men (20.3%) and 311 women (79.7%), 95% of whom had completed high school or more; 54.4% of participants self-identified as non-Hispanic white, 38.5% as African-American, and 4.6% as Hispanic.

Treatment Groups

Table 2 provides an overview of the three treatment groups and reveals several commonalities. All participants were given the same diet and activity prescriptions but received different instructions and support for reaching these goals. Participants in Usual Care (N=130) met quarterly (i.e., every 3 months) with their PCP, who provided brief recommendations for weight management and distributed handouts adapted from the NHLBI brochure, Aim for a Healthy Weight.40 PCPs did not provide specific instructions for behavior change or ask participants to keep food or activity records.

Table 2.

Overview of Treatment Groups.

| Treatment Component | Usual Care | Brief Lifestyle Counseling | Enhanced Brief Lifestyle Counseling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quarterly Visits with Primary Care Provider | √ | √ | √ |

| NHLBI Handouts: “Aim for a Healthy Weight” | √ | √ | √ |

| Dietary goal: | |||

| 1200–1500 kcal/d if < 250lb | √ | √ | √ |

| 1500–1800 kcal/d if ≥ 250lb | |||

| Exercise goal: | |||

| ≥ 180 min/wk of moderate intensity activity | √ | √ | √ |

| Record Food Intake and Activity | √ | √ | |

| Brief Monthly Counseling Sessions with Medical Assistant | √ | √ | |

| DPP* Lifestyle Modification Curriculum | √ | √ | |

| Meal Replacements** | √ | ||

| FDA-Approved Weight Loss Medication** | √ |

Diabetes Prevention Program

Participants in this group will select (with their PCP) the use of meal replacements or medication.

Participants in Brief Lifestyle Counseling (Brief LC) (N=131) received the same quarterly PCP visits. In addition, they had monthly, individual 10–15 min visits with a MA (i.e., a lifestyle coach) who was trained to deliver treatment following abbreviated lessons from the DPP.12,38 Each visit began with a weigh-in and review of participants’ diet and activity records (and other homework assignments). The coach then introduced a new topic on behavior change and reviewed goals for the coming month.

Individuals in Enhanced Brief Lifestyle Counseling (Enhanced Brief LC) (N=129) received the same treatment as those in Brief LC. However, in consultation with their PCP, they were given a choice of also using either meal replacements41 or a weight loss medication – either sibutramine28 or orlistat.31 These three options were provided because of evidence that they increased weight loss, by 3–4 kg in the first 6 months, as compared with traditional lifestyle counseling alone.31,34,41 Participants were only allowed one treatment option (including one medication) at a time but could switch between options with their PCP’s approval. Those who chose meal replacements were instructed for the first 4 months to replace two meals and one snack daily with shakes or meal bars (provided by SlimFast). Thereafter, they replaced one meal and one snack. Orlistat was provided as 60 mg at each meal (with the option of increasing to 120 mg after 6 months). Sibutramine was provided as 10 mg/d, with the option of increasing to 15 mg/d after 6 months if blood pressure and pulse values were within normal limits. (As noted previously, sibutramine was removed from the market in October 2010 because of findings of increased CVD events.35 Participants who were taking sibutramine were given the option of using orlistat or meal replacements.)

Treatment Delivery and Training of PCPs and Coaches

Delivery of the interventions was standardized across the six sites by the use of detailed protocols and provider scripts (available from the first author). All participating PCPs and coaches were trained to deliver the intervention (to participants at their practice sites) by study staff who included physicians, psychologists, and registered dietitians. An initial 6–8 hours of training, provided before the study began, included an overview of the etiology and treatment of obesity, as well as a detailed review of the treatment materials provided to participants (and of methods to assess participants’ adherence to the intervention).4,39 Role-plays were conducted with PCPs and coaches to simulate patient visits, and a checklist was used to assess providers’ adherence to the protocol. (PCPs also receive extensive education about the use of sibutramine and orlistat, including contraindications to treatment and monitoring for side effects.) PCPs and coaches were recertified in treatment delivery every 6 months, and they met with study staff at least monthly (i.e., PCPs) and as frequently as weekly (i.e., coaches) throughout the study to discuss issues related to protocol implementation and participants’ progress.

Outcome Measures and Retention

All outcome measures were collected at randomization and at follow-up visits at months 6, 12, and 24. Change in body weight (in kg) from baseline to year 2 was the study’s primary outcome. The primary hypothesis was that participants in both Brief LC and Enhanced Brief LC would lose significantly more weight at year 2 than those in Usual Care. Secondary hypotheses included that participants in Enhanced Brief LC would lose significantly more weight at year 2 than those who received Brief LC. The three groups also were compared on changes in measures of CVD risk, eating behavior, physical activity, mood, quality of life, and treatment cost (as described in the additional papers in this supplement).

A total of 110 (84.6%) Usual Care participants completed the 2-year assessment, as did 112 (85.5%) and 114 (88.4%) of those in Brief LC and Enhanced Brief LC, respectively. Changes in weight in the intention-to-treat (ITT) population (which included all randomized participants) were compared using repeated measures linear mixed-effects models (for continuous outcomes) and generalized estimating equations models (for categorical outcomes).4

Weight Losses

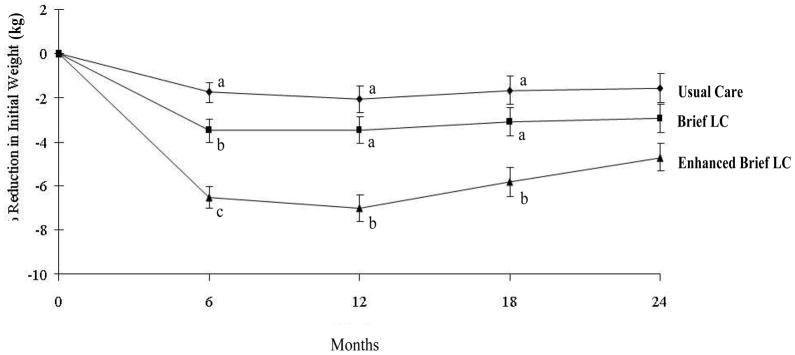

At month 24, participants in Usual Care, Brief LC, and Enhanced Brief LC lost a mean (± SEM) of 1.7±0.7, 2.9±0.7, and 4.6±0.7 kg, respectively (see Figure 1A). Enhanced Brief LC was superior to Usual Care (p<0.001), whereas other differences between groups were not statistically significant. Weight losses of all three groups differed significantly from each other at month 6 and generally reached their maximum at month 12 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mean (±SE) weight loss (in kg) in participants assigned to Usual Care, Brief Lifestyle Counseling (Brief LC), and Enhanced Brief Lifestyle Counseling (Enhanced Brief LC). At months 6, 12, and 18, groups with different superscripts (i.e., a, b, c) differ significantly (p ≤ 0.05) from each other.

A total of 21.5%, 26.0%, and 34.9% of participants in Usual Care, Brief LC, and Enhanced Brief LC, respectively, lost ≥5% of initial weight, with significant (p=0.02) differences between the first and third groups only. Corresponding values for losing ≥10% were 17.8%, 9.9%, and 6.2%, respectively, with the only significant (p=0.006) differences between the same two groups. (The percentage of participants who lost ≥5% included those who lost ≥10%.)

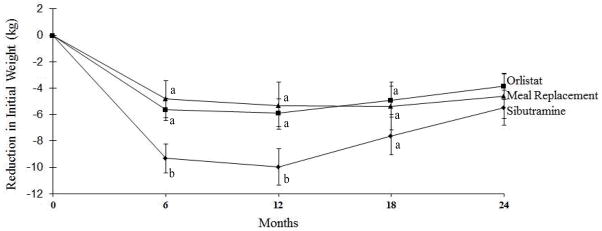

At the trial’s outset, 67, 38, and 24 participants in Enhanced Brief LC chose meal replacements, sibutramine, and orlistat, respectively, as their enhancement. An ITT analysis, based on participants’ initial choice of enhancements, showed that these groups lost 3.9±1.0, 5.5±1.3, and 4.6±1.7 kg, respectively, at month 24, with no significant differences among groups (see Figure 2). Eleven (16.4%) participants who began the trial on meal replacements switched enhancements, as did 15 (38.5%) on sibutramine, and 8 (34.8%) on orlistat. Nine sibutramine discontinuations were in response to FDA warnings about the medication, the first in November 2009, which culminated in its removal from the market in October 2010. The 6-month assessment occurred prior to these warnings for all participants.

Figure 2.

Mean (±SE) weight loss (in kg) in participants in Enhanced Brief Lifestyle Counseling who chose at the start of the trial to use sibutramine, meal replacements, or orlistat as their enhancement. (Participants may have changed enhancements during the study.) At months 6, 12, and 18, groups with different superscripts (i.e., a, b, c) differ significantly (p ≤ 0.05) from each other.

Month 24 weight losses for Enhanced Brief LC were reanalyzed, excluding the 44 (of 129) individuals who received sibutramine at any time. The remaining 85 participants lost 4.3±0.8 kg at month 24, which was significantly greater than the loss for Usual Care (1.7±0.7 kg) but not for Brief LC (2.9±0.7 kg). An analysis of the 66 participants in Enhanced Brief LC who used meal replacements (without ever using sibutramine) for the majority of the trial revealed a loss of 4.1±0.9 kg at month 24, which was significantly (p=0.044) greater than that for Usual Care but not Brief LC (p=0.302).

Clinical Implications of POWER-UP

Results of POWER-UP indicate that PCPs, working with MAs, can provide effective weight management for some of their obese patients in primary care practice. The Usual Care intervention, in which PCPs provided handouts and spoke briefly with participants about their weight at quarterly intervals, helped 22% of participants lose ≥5% of initial weight. By contrast, the study’s most intensive intervention, Enhanced Brief LC, facilitated 35% of patients achieving this goal. POWER-UP, thus, provides primary care practices a model for delivering lifestyle counseling to their obese patients, as encouraged by the U.S Preventive Services Task Force.1 Meal replacements probably provide a more economical and patient-acceptable method than medications of increasing weight loss with brief lifestyle counseling. Participants who used primarily meal replacements throughout the trial lost an average of 4.1 kg at 2 years, a value that compared favorably (at the same duration of follow-up) with the results of more intensive, group lifestyle modification programs.11,12,42

POWER-UP’s use of brief lifestyle counseling visits is particularly timely in view of the Centers’ for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) decision in 2011 to reimburse the provision of intensive behavioral weight loss counseling to obese seniors, when delivered by physicians, nurse practitioners, or physician assistants working in primary care.8 The CMS model proposes that patients have weekly, brief (i.e., 15 minute) face-to-face counseling visits the first month, followed by twice-monthly visits for the next 5 months. Patients who lose 3 kg at the end of this time are eligible for 6 additional monthly visits. The efficacy of this treatment model, as delivered by PCPs identified above, has not been tested. However, we believe that the higher frequency of treatment visits prescribed by CMS, compared to POWER-UP’s visit schedule (14 vs. 8 visits, respectively, in the first 6 months), should increase mean weight loss accordingly.43

In designing the POWER-UP study, we had wanted to provide more frequent lifestyle counseling visits to increase weight loss. However, we decided against this approach for fear of overwhelming the practices’ already busy MAs. PCPs with whom we discussed the issue believed that a high intensity intervention would be difficult to disseminate in primary care. They similarly thought that even a moderate intensity intervention (i.e., monthly visits), as used in POWER-UP, would be difficult to implement if the practice did not have additional support and funding.

Options for Lifestyle Modification in Primary Care Practice

In 2012, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force updated its recommendation that clinicians screen all adults for obesity and offer intensive multicomponent behavioral interventions to affected individuals.7 Two important modifications included: 1) a clear recommendation for high intensity counseling (defined as more than monthly contact); and 2) the suggestion that practitioners either provide such treatment themselves or refer patients to appropriate interventions. The option of referral is an important one, given that community-based weight loss programs and providers may be able to provide weight reduction at lower cost than primary care practitioners. However, we believe that it is critical to maintain PCPs’ involvement in the management of obesity and its co-morbidities, regardless of whether patients are referred out of practice for lifestyle counseling.

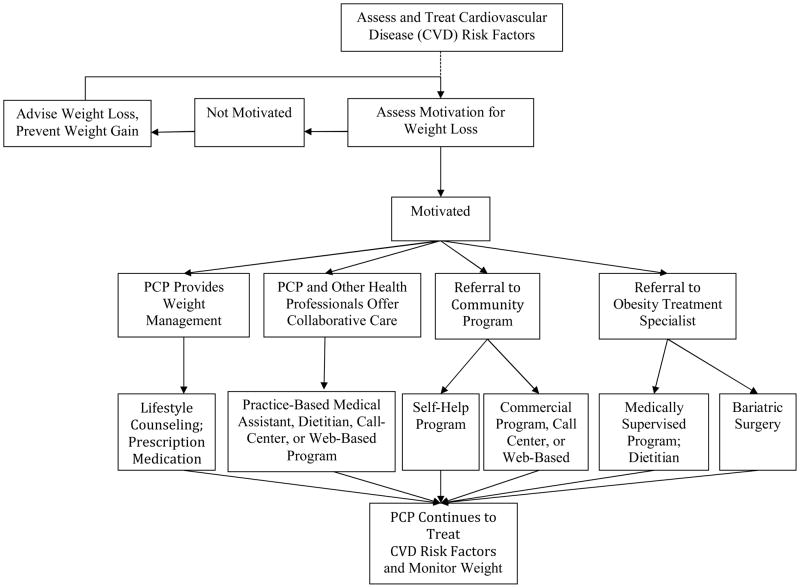

Tsai and Wadden44 proposed a treatment algorithm that puts PCPs at the center of obesity management, while providing numerous options for the provision of lifestyle modification with appropriate patients (see Figure 3). In this model, PCPs play a critical role in screening adults for obesity and in providing appropriate medical management for weight-related CVD risk factors and other conditions. PCPs also are well prepared to educate patients about the contribution of excess weight to health complications, as well as to inform them of the significant health benefits of a 5 to 10% reduction in initial weight.9,10 Practitioners also can assess obese patients’ motivation for weight reduction and, with interested patients, develop a weight loss plan. This could include brief quarterly counseling visits, shown by POWER-UP to be effective in inducing meaningful weight loss in about 20% of participants. With patients who do not wish to lose weight, PCPs should seek to clarify barriers to weight reduction and discuss the need to at least prevent further weight gain.45

Figure 3.

An algorithm for identifying an appropriate weight loss option. After treating cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors and assessing patients’ activation for weight loss, primary care providers (PCPs) may elect to offer behavioral counseling themselves (with or without pharmacotherapy) or to provide collaborative care with other health professionals. Alternatively, PCPs may refer patients to community programs (e.g., Weight Watchers) or to obesity treatment specialists (e.g., medically supervised programs, bariatric surgery).

PCPs have multiple options for offering behavioral weight loss counseling. We have already discussed options shown on the left-hand side of the algorithm which include physician-delivered lifestyle counseling (with or without the use of medication) and collaborative obesity care in which lifestyle modification is delivered by MAs, as in the POWER-Up study, or by other office personnel including health counselors, nurses, or dietitians. Some primary care practices may be able to offer group treatment, as provided in academic medical centers.46 In all cases, patients would receive behavioral weight management within the primary care practice, which has the advantage of capturing individuals at the point of treatment and fully integrating weight management with patients’ other health care.

The provision of behavioral counseling, using any of these models, may be impractical in many primary care practices because of the increased volume of patient visits (resulting from high frequency counseling), lack of physical space, or costs of hiring additional staff. Some PCPs may be able to refer patients to programs or professionals who provide counseling as part of an integrated health care system to which the practice belongs.

Alternatively, as shown on the right-hand-side of Figure 3, PCPs may refer motivated patients to self-help or commercial programs in the community that have been empirically validated (e.g., Weight Watchers47,48). These could include programs delivered by telephone (i.e., call centers), Internet, or their combination. PCPs also may refer patients to obesity-treatment specialists in the community (e.g., registered dietitians, physicians, bariatric surgeons). With all of these options, patients will benefit from their PCPs actively monitoring changes in their weight and health, congratulating them on their success, and reminding them of the need for long-term behavior change. We believe that PCPs must remain active members of the weight management team.

The Two Other POWER Trials

Be Fit, Be Well5 and POWER Hopkins6 both recruited obese patients from primary care practices, using similar participant eligibility criteria as the POWER-UP trial. However, the lifestyle interventions used in the two former trials diverged significantly from POWER-UP’s by delivering obesity management outside of the primary care practices, following models proposed on the right-hand side of Figure 3. As briefly described, both studies included the use of telephone- and Internet-delivered interventions.

Be Fit, Be Well randomly assigned predominantly low-income patients with hypertension to: 1) usual care; or 2) a 2-year behavioral weight loss intervention that also included self-management of hypertension. Every 3 months, intervention participants were prescribed three tailored goals to modify their eating and activity behaviors (e.g., reducing fat intake), which they monitored using either an interactive voice response (IVR) system or a study website. (Participants did not receive specific prescriptions for food intake [e.g., 1200 kcal/d] or physical activity [e.g., 180 min/wk of walking] because of concerns that such goals would not be acceptable to many individuals.) Intervention participants had monthly 15–20 minute telephone counseling calls the first year and every-other-month calls the second year. Calls were conducted by trained community health educators who also provided 12 optional, on-site group treatment sessions. Participants’ PCPs delivered at least one brief standardized message about the importance of participating in the intervention but otherwise did not provide any weight loss counseling.

As summarized in Table 3, at month 24, the usual care and intervention groups lost a mean of 0.5 kg and 1.5 kg, respectively. It is impossible to determine whether the modest average weight losses observed in the intervention group were attributable to the (primarily) remote delivery of treatment (by IVR and website), the moderate intensity of care (i.e., monthly contact), the decision not to provide specific goals for energy intake or expenditure, or to the study’s low-income population, comprised principally of ethnic minorities (i.e., 71% African American). African Americans typically lose significantly less weight than non-Hispanic white participants during the first 12–24 months of lifestyle modification.15,49 The mean weight losses in Be Fit, Be Well were similar to those obtained by Kumanyika et al.50 in a trial of minority participants, also conducted in primary care practices.

Table 3.

A summary of the three POWER trials.

| Study | N | Interventions | Number of treatment visits | Months of post-randomization follow-up | Weight change at month 6, kg | Weight change at follow-up, kg | ≥ 5% loss of initial weight at follow-up, % of subjects | Attrition at follow-up, %* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wadden et al.4 | 390 | 1) Usual care | 8 | 24 | −2.0 ± 0.5a | −1.7 ± 0.7a | 21.5a | 15 |

| 2) Brief lifestyle counseling (quarterly PCP visits + MA counseling) | 33 | 24 | −3.5 ± 0.5b | −2.9 ± 0.7ab | 26.0ab | 15 | ||

| 3) Enhanced brief lifestyle counseling (quarterly PCP visits + MA counseling + meal replacements/medication) | 33 | 24 | −6.6 ± 0.5c | −4.6 ± 0.7b | 34.9b | 12 | ||

| Bennett et al.5 | 365 | 1) Usual care | 0 | 24 | −0.1 ± 0.4a | −0.5 ± 0.4a | 19.5 | 10 |

| 2) Telephone + electronic-based + group counseling | 30 | 24 | −1.3 ± 0.4b | −1.5 ± 0.4b | 20.0 | 18 | ||

| Appel et al.6 | 415 | 1) Control (self-directed) | 2 | 24 | −1.4 ± 0.4a | −0.8 ± 0.6a | 18.8a | 7 |

| 2) Remote support only (telephone + electronic-based counseling) | 33 | 24 | −6.1 ± 0.5b | −4.6 ± 0.7b | 38.2b | 5 | ||

| 3) In-person support (telephone + electronic-based + in-person counseling) | 57 | 24 | −5.8 ± 0.6b | −5.1 ± 0.8b | 41.4b | 4 |

Note: Values shown for weight change are mean ± SEM. For each study, under “weight change” (at month 6 and at follow-up) and “ ≥5% loss of initial weight at follow-up,” values labeled with different letters (a,b,c) are significantly different from each other at p < 0.05; PCP = primary care provider; MA = medical assistant.

Attrition is defined as the percentage of participants who did not contribute an in-person weight at the end of the study. An intention-to-treat analysis was used in these studies.

Weight losses represent percentage weight change.

The POWER Hopkins trial examined the effectiveness of a 2-year behavioral weight loss intervention delivered remotely or in-person, in both cases by interventionists not affiliated with the primary care practices from which participants were recruited. Participants randomized to the Remote Support condition had 12 initial weekly phone calls (20 min), delivered by a trained counselor (from Healthways; www.healthways.com), followed by monthly calls for the remainder of the study (for a total of 33 phone contacts over the 2 years). Participants were instructed to record their weight, calorie intake and physical activity in a web-based program (provided by the study), which also presented a curriculum of behavior change.

Participants assigned to In-Person Support were provided weekly sessions for the first 3 months (9 group and 3 individual meetings) and 3 sessions per month (1 group and 2 individual meetings) from months 4–6. (All sessions were led by trained interventionists from Johns Hopkins University.) For the remainder of the study, these participants were offered two sessions per month, with one group and one individual contact (that latter which could be completed by phone, if desired), for a total of 57 contacts over 2 years. These participants were prescribed the same diet and activity goals as those in the Remote-Support condition and were provided the same web-based program. PCPs of participants in both intervention groups were provided a one-page report on patients’ progress at each routine office visit (i.e., scheduled as needed by patients, rather than as determined by the study), and they encouraged patients’ participation in the intervention. Participants assigned to a control group were provided a brief meeting with a lifestyle coach at randomization and the option of another meeting at month 24.

At month 24, mean weight losses in the Control, Remotely-Delivered, and In-Person Support conditions were 0.8, 4.6, and 5.1 kg, respectively (see Table 3). Weight decreased by ≥5% in 18.8, 38.2, and 41.4% of patients in the three groups, respectively. Both intervention groups were superior to usual care on both measures of success (p < 0.001).

The mean 4.6 kg weight loss achieved by the Remotely-Delivered intervention in POWER Hopkins is particularly impressive because it was achieved with only 33 brief telephone contacts, combined with the use of a web-based program. This intervention would appear to be as effective and significantly less costly, with respect to provider and participant time, than the In-Person intervention, which provided a total of 57 in-person contacts (combined with the same web-based program). Findings for the intervention contribute to a growing body of literature that indicates that high-intensity telephone-based interventions (with or without the addition of a web-based program) produce weight losses comparable to those achieved in traditional in-person interventions. (A version of the Power Hopkins Remotely-Delivered intervention is now commercially available from Healthways as “innergy.”)

Looking Ahead in Primary Care

POWER-UP’s Brief Enhanced Lifestyle Counseling approach and POWER Hopkins’ Remote Support intervention used markedly different methods to provide weight management to obese patients in primary care but achieved roughly comparable results at two years. POWER-UP offered weight management to patients in their primary care settings, as delivered by familiar PCPs and MAs from the practices. POWER Hopkins offered lifestyle modification through a call center operated by a commercial vendor (Healthways) with which patients had never had contact. POWER-UP used meal replacements and medications to increase weight loss above that which could be achieved by once-monthly lifestyle counseling alone (as demonstrated during the first 6 months). POWER Hopkins used weekly, brief (20 minutes) telephone calls during the first 12 weeks, combined with an interactive web-site, to deliver the high-intensity counseling that is commonly offered in academic medical centers. Both treatment models have their strengths and weaknesses and both potentially have a place in the management of obesity in primary care practice. PCPs’ desire to offer lifestyle counseling in their practices would be a critical determinant of their adopting the POWER-UP model, described here.

Cost is perhaps the most pressing issue facing the provision of weight loss counseling in primary care practice, as discussed by Tsai et al. in this supplement. Even though POWER-UP has demonstrated that PCPs and MAs, working together, can induce clinically meaningful weight loss in some patients, this finding does not necessarily mean that they can afford to provide such care, when less expensive, equally effective weight loss interventions may be available. The same concern arises when considering CMS’s proposal to reimburse only physicians, nurse practitioners (NPs), and physician assistants (PAs) for providing weight loss counseling. Ultimately, these practitioners, with their health care administrators, must decide whether they can afford to devote time to behavioral weight loss counseling, with its demand for weekly and then twice-monthly sessions for the first 6 months. Practices would have to hire more physicians, NPs, and PAs to provide routine medical care to patients whose former PCPs’ schedules were now filled delivering behavioral weight loss counseling. Hiring registered dietitians or other trained lifestyle interventionists to provide lifestyle modification would appear to be more economical for primary care practices (and CMS) than deploying physicians, NPs, and PAs in this effort.

The option of having patients receive weight loss counseling from a call center, Internet program, or face-to-face commercial program would appear to be very attractive to primary care practitioners and health plans, provided that the interventions had demonstrated their safety and efficacy in peer reviewed publications. In addition to potentially being less costly for health insurers and other payers to provide, remotely-delivered programs would appear to be more convenient and more economical for patients. A recent 26-week trial by Harvey-Berino et al. compared an in-person intervention to the same program provided by Internet.51,52 The in-person group lost a mean of 8.0 kg, compared with 5.5 kg for the Internet program. However, the cost of delivering the Internet program was only $372 per person compared with $702 for the in-person intervention, a difference based largely on participants’ travel costs. The attractiveness of Internet and call-center interventions is further enhanced by the ability to deliver them to persons in rural communities who do not have access to traditional face-to-face interventions.

The NHLBI-supported POWER trials have provided an important first step in identifying safe and effective methods of providing weight management to obese individuals encountered in primary care practice. Findings from the papers contained in this supplement, as well as additional expected publications from Be Fit, Be Well and POWER Hopkins, should provide preliminary guidance for practitioners who wish to provide weight loss counseling. As important, the present findings provide important hypotheses to test concerning the skills and credentials required to provide weight management in primary care and concerning the most cost-effective methods of providing such counseling.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (U01-HL087072) and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (K24-DK065018).

POWER-UP ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT00826774

This research was supported by grants U01-HL087072 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and K24-DK065018 from the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease.

We thank Amos Odeleye for his assistance with statistical analysis.

POWER-UP Research Group: Investigators and Research Coordinators

Academic investigators at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania were Thomas A. Wadden, Ph.D. (principal investigator), David B. Sarwer, Ph.D. (co-principal investigator), Robert I. Berkowitz, M.D., Jesse Chittams, M.S., Lisa Diewald, M.S., R.D., Shiriki Kumanyika, Ph.D., Renee Moore, Ph.D., Kathryn Schmitz, Ph.D., Adam G. Tsai, M.D., MSCE, Marion Vetter, M.D., and Sheri Volger, M.S., R.D.

Research coordinators at the University of Pennsylvania were Caroline H. Moran, B.A., Jeffrey Derbas, B.S., Megan Dougherty, B.S., Zahra Khan, B.A., Jeffrey Lavenberg, M.A., Eva Panigrahi, M.A., Joanna Evans, B.A., Ilana Schriftman, B.A, Dana Tioxon, Victoria Webb, B.A., and Catherine Williams-Smith, B.S.

POWER-UP Research Group: Participating Sites and Clinical Investigators

PennCare - Bala Cynwyd Medical Associates: Ronald Barg, M.D., Nelima Kute, M.D., David Lush, M.D., Celeste Mruk, M.D., Charles Orellana, M.D., and Gail Rudnitsky, M.D. (primary care providers); Angela Monroe (lifestyle coach); Lisa Anderson (practice administrator).

PennCare - Internal Medicine Associates of Delaware County: David E. Eberly, M.D., Albert H. Fink Jr., M.D., Kathleen Malone, C.R.N.P., Peter B. Nonack, M.D., Daniel Soffer, M.D., John N. Thurman, M.D., and Marc J. Wertheimer, M.D. (primary care providers); Barbara Jean Shovlin, Lanisha Johnson (lifestyle coaches); Jill Esrey (practice administrator).

PennCare - Internal Medicine Mayfair: Jeffrey Heit, M.D., Barbara C. Joebstl, M.D., and Oana Vlad, M.D. (primary care providers); Rose Schneider, Tammi Brandley (lifestyle coaches); Linda Jelinski (practice administrator).

Penn Presbyterian Medical Associates: Joel Griska, M.D., Karen J. Nichols, M.D., Edward G. Reis, M.D., James W. Shepard, M.D., and Doris Davis-Whitely, P.A. (primary care providers); Dana Tioxon (lifestyle coach); Charin Sturgis (practice administrator).

PennCare - University City Family Medicine: Katherine Fleming, C.R.N.P., Dana B. Greenblatt, M.D., Lisa Schaffer, D.O., Tamara Welch, M.D., and Melissa Rosato, M.D. (primary care providers); Eugonda Butts, Marta Ortiz, Marysa Nieves, and Alethea White (lifestyle coach); Cassandra Bullard (practice administrator).

PennCare - West Chester Family Practice: Jennifer DiMedio, C.R.N.P., Melanie Ice, D.O., Brandt Loev, D.O., John S. Potts, D.O., and Christine Tressel, D.O. (primary care providers); Iris Perez, Penny Rancy, and Dianne Rittenhouse (lifestyle coaches); Joanne Colligan (practice administrator).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Thomas Wadden serves on the advisory boards of Novo Nordisk and Orexigen Therapeutics, which are developing weight loss medications, as well as of Alere and the Cardiometabolic Support Network, which provide behavioral weight loss programs. David Sarwer discloses relationships with the following companies: Allergan, BaroNova, Enteromedics, Ethicon Endo-Surgery, and Galderma. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.U S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for obesity in adults: recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:930–2. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galuska D, Will J, Serdula M, Ford E. Are health care professionals advising obese patients to lose weight? JAMA. 1999;282:1576–1578. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeh HC, Clark JM, Emmons KE, Moore RH, Bennett GG, Warner ET, et al. Independent but coordinated trials: insights from the Practice-based Opportunities for Weight Reduction Trials Collaborative Research Group. Clin Trials. 2010;7:322–32. doi: 10.1177/1740774510374213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wadden TA, Volger S, Sarwer DB, Vetter ML, Tsai AG, Berkowitz RI, et al. A two-year randomized trial of obesity treatment in primary care practice. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1969–79. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Appel LJ, Clark JM, Yeh HC, Wang NY, Coughlin JW, Daumit G, et al. Comparative effectiveness of weight-loss interventions in clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1959–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett GG, Warner ET, Glasgow RE, Askew S, Goldman J, Ritzwoller DP, et al. Obesity treatment for socioeconomically disadvantaged patients in primary care practice. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:565–74. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moyer VA, on behalf of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Screening for and management of obesity in adults. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:373–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-5-201209040-00475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed December 14, 2012];Decision memo for intensive behavioral therapy for obesity (CAG-00423N) Available at: http://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decisionmemo.aspx?&NcaName=Intensive%20Behavioral%20Therapy%20for%20Obesity&bc=ACAAAAAAIAAA&NCAId=253.

- 9.National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. Obes Res. 1998;6:51S–210S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the North American Association for the Study of Obesity. The Practical Guide: Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wadden TA, Victoria LW, Moran CH, Bailer BA. Lifestyle modification for obesity: new developments in diet, physical activity, and behavior therapy. Circulation. 2012;125:1157–1170. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.039453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knowler WC Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donnelly JE, Blair SN, Jakicic JM, Manore MM, Rankin JW, Smith BK American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand. Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:459–71. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181949333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pi-Sunyer X, Blackburn G, Brancati FL, Bray GA, Bright R, Clark JM, et al. Look AHEAD Research Group. Reduction in weight and cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes: one-year results of the Look AHEAD trial. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1374–83. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wadden TA, West DS, Neiberg RH, Wing RR, Ryan DH, Johnson KC, et al. Look AHEAD Research Group. One-year weight losses in the Look AHEAD study: factors associated with success. Obesity. 2009;17:713–22. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wing RR Look AHEAD Research Group. Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1481–1486. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wadden TA, Neiberg RH, Wing RR, Clark JM, Delahanty LM, Hill JO, et al. Look AHEAD Research Group. Four-year eight losses in the Look AHEAD study: factors associated with long-term success. Obesity. 2011;19:1987–98. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haapala I, Barengo NC, Biggs S, Surakka L, Manninen P. Weight loss by mobile phone: a 1-year effectiveness study. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:2382–91. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009005230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tate DF, Jackvony EH, Wing RR. Effects of internet behavioral counseling on weight loss in adults at risk for type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289:1833–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harvey-Berino J, West D, Krukowski R, Prewitt E, VanBiervliet A, Ashikaga T, et al. Internet delivered behavioral obesity treatment. Prev Med. 2010;51:123–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Digenio AG, Mancuso JP, Gerber RA, Dvorak RV. Comparison of methods for delivering a lifestyle modification program for obese patients: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:255–62. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-4-200902170-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Befort CA, Donnelly JE, Sullivan DK, Ellerbeck EF, Perri MG. Group versus individual phone-based obesity treatment for rural women. Eat Behav. 2010;11:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perri MG, Limacher MC, Durning PE, Janicke DM, Lutes LD, Bobroff LB, et al. Extended-care programs for weight management in rural communities: the treatment of obesity in underserved rural settings (TOURS) randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2347–54. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.21.2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kushner RF. Barriers to providing nutrition counseling by physicians: a survey of primary care practitioners. Prev Med. 1995;24:546–52. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen MD, D’Amico FJ, Merestein JH. Weight reduction in obese hypertensive patients. Fam Med. 1991;23:25–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin PD, Rhode PC, Dutton GR, Redmann SM, Ryan DH, Brantley PJ. A primary care weight management intervention for low-income African-American women. Obesity. 2006;14:1412–20. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ockene IS, Hebert JR, Ockene JK, Saperia GM, Stanek E, Nicolosi R, et al. Effect of physician-delivered nutrition counseling training and an office-support program on saturated fat intake, weight, and serum lipid measurements in a hyperlipidemic population: Worcester Area Trial for Counseling in Hyperlipidemia (WATCH) Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:725–31. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.7.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wadden TA, Berkowitz RI, Womble LG, Sarwer DB, Phelan S, Cato RK, et al. Randomized trial of lifestyle modification and pharmacotherapy for obesity. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2111–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berkowitz RI, Wadden TA, Tershakovec AM, Cronquist JL. Behavior therapy and sibutramine for the treatment of adolescent obesity: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:1805–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Apfelbaum M, Vague P, Ziegler O, Hanotin C, Thomas F, Leutenegger E. Long-term maintenance of weight loss after a very-low-calorie diet: a randomized blinded trial of the efficacy and tolerability of sibutramine. Am J Med. 1999;106:179–84. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00411-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hauptman J, Lucas C, Boldrin MN, Collins H, Segal KR. Orlistat in the long-term treatment of obesity in primary care settings. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:160–7. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.2.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brownell KD, Wadden TA. The LEARN program for weight control: special medication edition. Dallas: American Health Publishing; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith SR, Weissman NJ, Anderson CM, Sanchez M, Chuang E, Stubbe S, et al. Multicenter, placebo-controlled trial of lorcaserin for weight management. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:245–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garvey WT, Ryan DH, Look M, Gadde KM, Allison DB, Peterson CA, et al. Two-year sustained weight loss and metabolic benefits with controlled-release phentermine-topiramate in obese and overweight adults (SEQUEL): a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 extension study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:297–308. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.024927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.James WP, Caterson ID, Coutinho W, Finer N, Van Gaal LF, Maggioni AP, et al. Effect of sibutramine on cardiovascular outcomes in overweight and obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:905–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mohler PJ. Enhancing compliance with screening mammography recommendations: a clinical trial in a primary care office. Fam Med. 1995;27:117–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katz DA, Brown RB, Muelenbruch DR, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Implementing guidelines for smoking cessation: comparing the efforts of nurses and medical assistants. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:411–416. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsai AG, Wadden TA, Rogers MA, Day SC, Moore RH, Islam BJ. A primary care intervention for weight loss: results of a randomized controlled pilot study. Obesity. 2010;18:1614–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Derbas J, Vetter M, Volger S, Khan Z, Panigrahi E, Tsai AG, et al. Improving weight management in primary care practice: a possible role for auxiliary health professionals collaborating with primary care physicians. Obesity and Weight Management. 2009;5:210–215. [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Aim for a healthy weight. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; Aug, 2005. (NIH publication no. 05-5213.) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heymsfield SB, van Mierlo CA, van def Knaap HC, Heo M, Frier HI. Weight management using a meal replacement strategy: meta and pooling analysis from six studies. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:537–49. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Svetkey LP, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ, Appel LJ, Hollis JF, Loria CM, et al. Weight Loss Maintenance Collaborative Research Group. Comparison of strategies for sustaining weight loss: The weight loss maintenance randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1139–1148. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.LeBlanc ES, O’Connor E, Whitlock EP, Patnode CD, Kapka T. Effectiveness of primary care-relevant treatments for obesity in adults: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:434–447. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-7-201110040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsai AG, Wadden TA. Treatment of obesity in primary care practice in the United States: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:1073–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1042-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DiLillo V, West DS. Motivational interviewing for weight loss. In: Wadden TA, Wilson GT, Stunkard AJ, Berkowitz RI, editors. Psychiatric Clinics of North America- Obesity and Associated Eating Disorders: A Guide for Mental Health Professionals. 1. Elsevier Inc; Philadelphia, PA, USA: 2011. pp. 861–870. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ma J, Yank V, Xiao L, Lavori PW, Wilson SR, Rosas LG, et al. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program lifestyle intervention for weight loss into primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2012 doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.987. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jebb SA, Ahern AL, Olson AD, Aston LM, Holzapfel C, Stoll J, et al. Primary care referral to a commercial provider for weight loss treatment versus standard care: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1485–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61344-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jolly K, Lewis A, Beach J, Denley J, Adab P, Deeks JJ, et al. Comparison of range of commercial or primary care led weight reduction programmes with minimal intervention control for weight loss in obesity: Lighten Up randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2011;343 doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kumanyika SK, Espeland MA, Bahnson JL, Bottom JB, Charleston JB, Folmar S, et al. TONE Cooperative Research Group. Ethnic comparison of weight loss in the trial of nonpharmacologic interventions in the elderly. Obes Res. 2002;10:96–106. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kumanyika SK, Fassbender JE, Sarwer DB, Phipps E, Allison KC, Localio R. One-year results of the Think Health! Study of weight management in primary care practices. Obesity. 2012;20:1249–57. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harvey-Berino J, West D, Krukowski R, Prewitt E, VanBiervliet A, Ashikagha T, et al. Internet delivered and behavioral obesity treatment. Prev Med. 2010;51:123–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krukowski RA, Tilford JM, Harvey-Berino J, West DS. Comparing behavioral weight loss modalities: incremental cost-effectiveness of an internet-based versus an in-person condition. Obesity. 2011;19:1629–35. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]