Abstract

Objectives. We tested 3 hypotheses—social causation, social drift, and common cause—regarding the origin of socioeconomic disparities in major depression and determined whether the relationship between socioeconomic status (SES) and major depression varied by genetic liability for major depression.

Methods. Data were from a sample of female twins in the baseline Virginia Adult Twin Study of Psychiatric and Substance Use Disorders interviewed between 1987 and 1989 (n = 2153). We used logistic regression and structural equation twin models to evaluate these 3 hypotheses.

Results. Consistent with the social causation hypothesis, education (odds ratio [OR] = 0.78; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.66, 0.93; P < .01) and income (OR = 0.93; 95% CI = 0.89, 0.98; P < .01) were significantly related to past-year major depression. Upward social mobility was associated with lower risk of depression. There was no evidence that childhood SES was related to development of major depression (OR = 0.98; 95% CI = 0.89, 1.09; P > .1). Consistent with a common genetic cause, there was a negative correlation between the genetic components of major depression and education (r2 = –0.22). Co-twin control analyses indicated a protective effect of education and income on major depression even after accounting for genetic liability.

Conclusions. This study utilized a genetically informed design to address how social position relates to major depression. Results generally supported the social causation model.

One of the most replicated findings in psychiatric epidemiology is the inverse relationship between psychopathology and socioeconomic status (SES). Beginning with the Jarvis report1 and replicated by seminal studies such as the Midtown Manhattan,2 New Haven,3 and the study of London women by Brown and Harris,4 population-based studies have consistently demonstrated that most forms of mental illness, from schizophrenia to depression, are more common among less educated and more impoverished groups.5

Despite this abundance of descriptive epidemiology, the underlying reason for the social patterning of psychopathology, specifically major depression, remains largely unresolved. There are 3 hypotheses that could produce this inverse association. First, social causation, which argues lower SES in young adulthood is associated with increased exposure to stress and adversity, which are established causes of major depression. In this model, low SES is the antecedent to major depression. Second, social drift, which argues that individuals with major depression (or genetic liability for depression) are less likely to move out of (or more likely to move into) low SES over the life course.6 In this model, major depression is the antecedent to low SES in adulthood. Third, the common cause model argues that some third factor increases risk for both major depression and low SES in adulthood. In this model, there is no direct relation between SES and depression; rather, the correlation between them is entirely attributable to this common (genetic or environmental) factor.

With a handful of notable exceptions,7–11 few studies have examined these hypotheses comprehensively in a single sample. For early onset, severe forms of psychopathology such as schizophrenia, extant studies generally support the social drift hypothesis.7,8 By contrast, for major depression most, but not all,6 evidence points to a social causation hypothesis.7,9–11 However, most of these studies have not accounted for individual differences in liability for psychopathology. It is now established major depression has a substantial genetic component,12,13 and it is possible that this genetic liability is a common cause of both depression and low SES. For example, children with depressed parents have lower educational attainment than children with nondepressed parents.14

The goals of this study were 2-fold. First, we used a twin study design to examine 3 hypotheses of the observed inverse relationship between SES and major depression: social causation, social drift, and common cause. Second, we determined whether the correlation between SES and depression varied as a function of genetic risk (e.g., gene–environment interaction). If the SES–depression relationship was predominantly driven by social causation, we expected that twins from low SES households would have both lower SES in adulthood and higher risk of major depression than twins from high SES households, and that this relationship would be similar for monozygotic (MZ) and dizygotic (DZ) pairs. If social drift was predominant, we expected that twins with major depression would have lower SES in adulthood than their parents did, and that this association would be similar for MZ and DZ pairs. There were 2 types of common causal pathways to be considered: (1) environmental and (2) genetic liability. For common environment factors, we expected that the twin with higher adulthood SES would have similar risk of depression as their co-twin among both MZ and DZ pairs, because the childhood social environment of MZ and DZ twins is similar,15 and the twin with high adulthood SES was still exposed to the same family environment as their co-twin. By contrast, the common genetic factors model leveraged the fact that MZ twins unexposed to major depression shared all of the genetic liability that increased depression (or low SES) risk as their co-twin, but that DZ co-twins shared only half the genetic predisposition. Therefore, we expected that the risk of major depression associated with low SES would be equal among adulthood SES-discordant MZ pairs but somewhat higher among discordant DZ pairs (because we expected a positive relationship between low SES and depression, and thus, the SES and depression relationship would reflect residual confounding by genetic factors that DZ twins did not share).13 Finally, there might be interplay between genetic liability and environment factors (e.g., genetic liability for major depression might sensitize individuals to the influence of SES), which we also evaluated.

As a caveat, although we positioned these hypotheses as competing models, it is possible that multiple processes might be operating simultaneously; for example, if evidence was consistent with social causation, it might be that this effect was strongest for those with low SES in childhood, suggesting a common social cause. Determining more precisely why SES and major depression are correlated may inform the implementation of interventions to promote mental health for disadvantaged groups.

METHODS

Data were from the Virginia Adult Twin Study of Psychiatric and Substance Use Disorders, a population-based study of non-Hispanic White MZ and DZ twins from the Mid-Atlantic Twin Registry. Participants were interviewed from 1987 to 1989 at a mean age of 30 years. Of twins successfully contacted, 92% completed interviews; additional details of the study design are described elsewhere.13 Because major depression is more common among women,16 and because the processes by which social disparities in depression emerge might vary by gender,17–19 this study was restricted to female–female twins to effectively “match” on gender-specific factors. Zygosity was determined using a twin physical resemblance questionnaire that was validated against genotyping with an error rate of approximately 5%.13 Participants' missing data on major depression or SES indicators were excluded.

Measures

Major depression.

Lifetime and past-year major depression were assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Revised Third Edition,16 a semistructured assessment with high interrater reliability.20 Each member of a twin pair was interviewed by different interviewers who were blinded to the depression status of the co-twin.16 A 4-level variable was created to index each individual’s aggregate genetic liability for major depression as reflected by their co-twin status: The variable was coded −1 for MZ twins whose co-twin had no history of depression; coded −0.5 for DZ twins whose co-twin had no history of depression; coded +0.5 for DZ twins whose co-twin had positive history of depression; and coded +1.0 for MZ twins whose co-twin had positive history of depression.

Childhood socioeconomic status.

Several indicators of SES were examined.3 Each participant was asked to report on the education of their main support in childhood (in years), which was then categorized (< 9, 9–11, 12, 13–15, 16, and > 16) for analysis. Occupation of the head of their household was categorized as: 0 = farmer or laborer, 1 = craftsperson or skilled laborer, 2 = service worker, 3 = clerical or salesperson, 4 = paraprofessional or technician, and 5 = professional manager. These were collapsed into blue collar (0–2) and white-collar (3–5) occupations for analysis. In instances in which twins disagreed on the level of education or occupation of the head of household (which occurred for 272 pairs [27.1%] for education and 327 [32.7%] pairs for occupation), only the highest reported value between the pair was used. The majority of disagreements (> 75%) within a pair were between adjacent categories.

Adulthood socioeconomic status.

Three indicators of SES in adulthood were investigated: education, income, and occupation. Education was categorized as previously described. Annual household income was categorized as less than $18 000, $18 000 to $23 999, $24 000 to $29 999, $30 000 to $34 999, $35 000 to $39 999, $40 000 to $49 999, $50 000 to $74 999, and $75 000 or greater. Personal occupation was categorized as previously described. Finally, indicators of financial strain were assessed: (1) whether individuals had enough money to meet their needs (dichotomized as not enough vs just or more than enough for analysis); and (2) how often individuals had trouble affording (a) leisure activities, (b) clothing, and (c) food, each measured on a 4-point scale and dichotomized as often versus sometimes, seldom, or never for analysis.

Socioeconomic mobility.

The social drift hypothesis was examined by comparing respondent’s SES to that of their main support in childhood. Average educational attainment has increased substantially over the past 50 years, and therefore, to quantify mobility in SES relative to parental SES, this overall population increase had to be taken into account. First, both parental education and adulthood education were standardized relative to their respective means (to transform years of education to educational attainment relative to their respective cohorts), and then a new variable representing the difference between standardized education in adulthood and standardized parental education was then created. This variable quantified an individual’s educational attainment relative to both their own cohort, and to their parents own educational attainment.

Analysis

Initially, the similarity between MZ and DZ twins in major depression and adulthood SES characteristics were assessed using tetrachoric correlation coefficients. Next, a series of logistic regression models were used to assess the association between indicators of parental and adulthood SES and both lifetime and past year major depression. Based on previous evidence that suggested a generally monotonic relationship between SES and health, we modeled the indicators of SES as continuous variables. These models accounted for age and genetic risk for major depression as indicated by co-twin depression history, as previously described. To further examine the possibility of a common cause (environmental or genetic) to both educational attainment in adulthood and major depression, paired odds ratios and McNemar’s test were calculated from co-twin control analyses. In these analyses, a direct causal effect between low educational attainment in adulthood and past year major depression was supported if the association between education and depression was similar for MZ and DZ pairs who were discordant for educational attainment. By contrast, if the association between education and major depression was stronger for DZ pairs than MZ pairs, this was supportive of a noncausal association because of genetic factors common to both depression and low SES.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to estimate the relative importance of genetic and environmental components of depression and SES. First, univariate twin models of major depression (and then SES) were fit. In these models, the total variance in major depression was decomposed into latent (not directly observed) additive genetic effects (A), shared environmental effects (C; i.e., environmental factors that are shared within a twin pair, such as parenting style), unique environmental effects (E; i.e., environmental factors experienced by only 1 twin, such as romantic relationships), and measurement error.13,21 In these SEM models, relative importance of A, C, and E sources of variance in major depression (and SES) is a function of the similarity of MZ pairs relative to DZ pairs; the correlation in A within the twin pairs is set at 1.0 for MZ twins and 0.5 for DZ twins, reflecting their genetic resemblance. Similarly, the correlation in C within twin pairs is set to 1.0 for both MZ and DZ twins (reflecting “equal environments” across twins),15 under the assumption that aspects of the shared environment (e.g., parenting style, family disruption) affect MZ and DZ twins similarly. To identify the best fitting model of the variance in major depression (and then SES), paths among A, C, and E were dropped in successive models to determine whether a more parsimonious model could be achieved without a loss of model fit (e.g., a model with just additive genetic and unique environment effects: AE).13,21 Model fit was assessed using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the log-likelihood test; smaller values of these indexes indicated better model fit. Once the best fitting univariate models of major depression and SES were identified, we fit a bivariate twin SEM to assess the genetic and environmental sources of covariance of major depression and low SES.

We used 2 strategies to evaluate gene–environment interaction. First, we assessed whether the relationship between SES indicators and risk of major depression varied by genetic liability for depression (indicated by an individual’s co-twin status) in logistic regression analyses. If the relationship between SES and major depression was more pronounced among individuals with high genetic risk, this suggested that genetic propensity for depression sensitized individuals to the influence of SES. Second, to evaluate whether the genetic and environmental contributions to major depression varied by indicators of childhood SES, SEM twin models were first fit within strata of childhood SES (i.e., low vs high parental education), which allowed the A, C, and E coefficients to vary across the strata; then, these coefficients were constrained to be equal across the strata. If the model fit significantly worsened when the parameters were forced to be equal (i.e., making the path that quantified the genetic source of variance in major depression the same for low SES as high SES), this would indicate that the influence of genetic or environmental factors on depression varied as a function of childhood SES.

Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and Mx version 1.68 (Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA).

RESULTS

Descriptive characteristics of the sample are provided in Table 1. Education of main support in childhood and adulthood educational attainment were correlated (0.43). For all adulthood SES variables, the correlation within pairs was substantially higher for MZ versus DZ twins. The correlation (mean ±SD) in educational attainment was 0.79 ±0.85 for MZ pairs and only 0.54 ±0.59 for DZ pairs. The correlation in household income was 0.40 ±0.44 for MZ pairs and 0.18 ±0.23 for DZ pairs, and the correlation in occupation was 0.50 ±0.53 for MZ pairs and 0.26 ±0.27 for DZ pairs. Correlations for the indicators of financial strain were markedly lower (on the order of 0.10–0.16 for MZ twins and 0.04–0.10 for DZ twins).

TABLE 1—

Descriptive Characteristics for Female Twins in the Baseline Virginia Adult Twin Study of Psychiatric and Substance Use Disorders: Virginia, 1987–1989

| Variable | No. (%) or Mean ±SD |

| Age, y | 30.08 ±7.6 |

| Zygosity | |

| MZ | 1240 (57.59) |

| DZ | 913 (42.41) |

| Lifetime major depression | 757 (35.00) |

| Childhood SES | |

| Education of main support, y | |

| < 9 | 538 (25.35) |

| 9–11 | 289 (13.62) |

| 12 | 644 (30.35) |

| 13–15 | 241 (11.36) |

| 16 | 221 (10.41) |

| > 16 | 189 (8.91) |

| Occupation of main support | |

| Farmer/laborer/craftsperson | 901 (42.54) |

| Service/clerical/salesperson | 231 (10.91) |

| Technical/professional/manager | 986 (46.55) |

| Adulthood SES | |

| Education, y | |

| < 9 | 21 (0.97) |

| 9–11 | 113 (5.22) |

| 12 | 833 (38.51) |

| 13–15 | 613 (28.34) |

| 16 | 425 (19.65) |

| > 16 | 158 (7.30) |

| Household income, $ (n = 2028) | |

| < 18 000 | 313 (15.44) |

| 18 000–23 999 | 255 (12.57) |

| 24 000–29 999 | 276 (13.61) |

| 30 000–34 999 | 219 (10.80) |

| 35 000–39 999 | 204 (10.06) |

| 40 000–49 999 | 282 (13.91) |

| 50 000–74 999 | 333 (16.42) |

| ≥ 75 000 | 146 (7.20) |

| Occupation | |

| Farmer/laborer/craftsperson | 149 (8.72) |

| Service/clerical/sales | 845 (49.44) |

| Technical/professional/managerial | 715 (41.84) |

| Indicators of adulthood financial strain | |

| Have enough money | |

| Yes | 1874 (86.64) |

| No | 289 (13.36) |

| Have trouble affording leisure items | |

| No | 1887 (87.24) |

| Yes | 276 (12.76) |

| Have trouble affording clothing | |

| No | 1450 (67.04) |

| Yes | 713 (32.96) |

| Have trouble affording food | |

| No | 1580 (73.05) |

| Yes | 583 (26.95) |

Note. DZ = dizygotic; MZ = monozygotic; SES = socioeconomic status. The sample size was n = 2163.

We initially explored the social causation hypothesis. As expected, having genetic liability for depression was strongly associated with major depression in the past year in a dose-response manner (relative to MZ twins whose co-twin never had major depression [MZ−]: odds ratio [OR]DZ− = 1.63; ORDZ+ = 2.80; and ORMZ+ = 2.86; all P < .05). Higher educational attainment in adulthood was significantly associated with lower odds of major depression in the past year even after accounting for depression status of the co-twin in the sample overall (OR = 0.82; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.72, 0.94). The protective association between educational attainment and major depression persisted after accounting for education of main support in childhood (OR = 0.78; 95% CI = 0.66, 0.93). The relationship between household income and past year major depression was similar to that of education (OR = 0.93; 95% CI = 0.89, 0.98). The 4 indicators of financial strain were all significantly predictive of great risk of past year major depression; for example, not having enough money was associated with a doubling in the odds of depression even after accounting for household income and genetic risk (OR = 2.05; 95% CI = 1.42, 2.95).

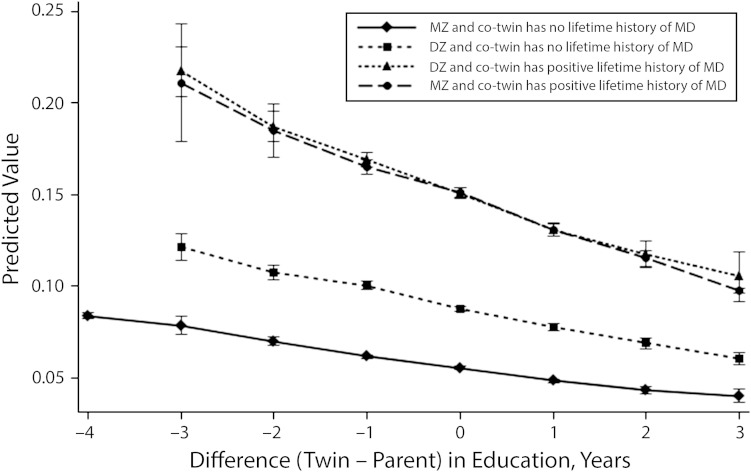

We then examined the social drift hypothesis by assessing whether upward or downward social mobility relative to one’s main support in childhood was associated with major depression. Greater educational attainment relative to one’s main support in childhood was significantly associated with lower risk of past year major depression, even after accounting for genetic risk in the sample overall (OR = 0.84; 95% CI = 0.72, 0.99), indicating that upward mobility—independent of actual years of education attained—was a unique protective factor for depression. This relationship was similar for MZ and DZ twins who had a co-twin with major depression (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Predicted probability of past year major depression by difference between participant’s own education and education of main support in childhood: Baseline Virginia Adult Twin Study of Psychiatric and Substance Use Disorders, Virginia, 1987–1989.

Note. DZ = dizygotic; MZ = monozygotic. Data were adjusted for age and zygosity, stratified by major depression (MD) status of co-twin. Whiskers indicate 95% confidence intervals.

We next addressed the common social cause hypothesis. Higher childhood SES, indexed by education of main support in childhood, was not associated with lower odds of lifetime major depression (OR = 0.98; 95% CI = 0.89, 1.09); this indicated that low SES of origin was not a common cause of both major depression and low SES in adulthood. In the SEM analyses, model fit did not significantly deteriorate when estimates were constrained to be equal across strata of childhood SES (either education or occupation), indicating that the genetic and environmental contributions to major depression did not vary as a function of childhood SES (data available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

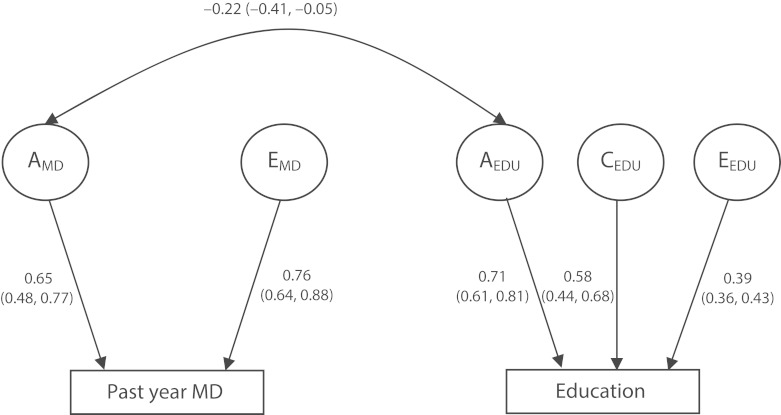

We then examined the common genetic cause hypothesis using bivariate twin models. In this model, a restricted AE (genetic and unique environment only) model was a better fit for past year major depression than the full ACE model; education was best described by a full ACE (genetic, common environment, and unique environment) model. As shown by Figure 2, genetic risk for depression and higher educational attainment were modestly inversely correlated (r2 = –0.22). Co-twin control analyses, which accounted for this genetic correlation by examining the relationship between education and major depression within twin pairs discordant for education, were consistent with a causal relationship between low educational attainment in adulthood and past year depression because the association between low education and major depression was similar for the 3 key groups: the entire population, and MZ and DZ discordant pairs (OROverall = 75.1; 95% CI = 37.4, 150.9; ORMZ = 77.6; 95% CI = 32.1, 187.5; and ORDZ = 71.0; 95% CI = 22.7, 221.9; all P < .001). Analyses examining family income and past year major depression were also consistent with a causal interpretation (OROverall = 9.44; 95% CI = 5.81, 15.35; P < .001; ORMZ = 12.78; 95% CI = 6.48, 25.18; P < .001; ORDZ = 6.11; 95% CI = 3.02, 12.37; P < .001). Thus, although SEM analyses indicated a genetic correlation between major depression and education, the co-twin control analyses showed that the predictive association between education and depression was consistent with a causal model, rather than shared genetic risk.

FIGURE 2—

Bivariate twin model of past year major depression and educational attainment in adulthood: Baseline Virginia Adult Twin Study of Psychiatric and Substance Use Disorders, Virginia, 1987–1989.

Note. A = Additive genetic effects; AIC = Akaike Information Criteria; C = Common environmental effects shared by twins that make them more similar; E = Unique environmental effects that make twins different; MD = major depression. AICBEST MODEL = −1759.4 (df = 4296) versus AICFULL MODEL = −1756.7 (df = 4293). Values are standardized path coefficients (95% confidence interval).

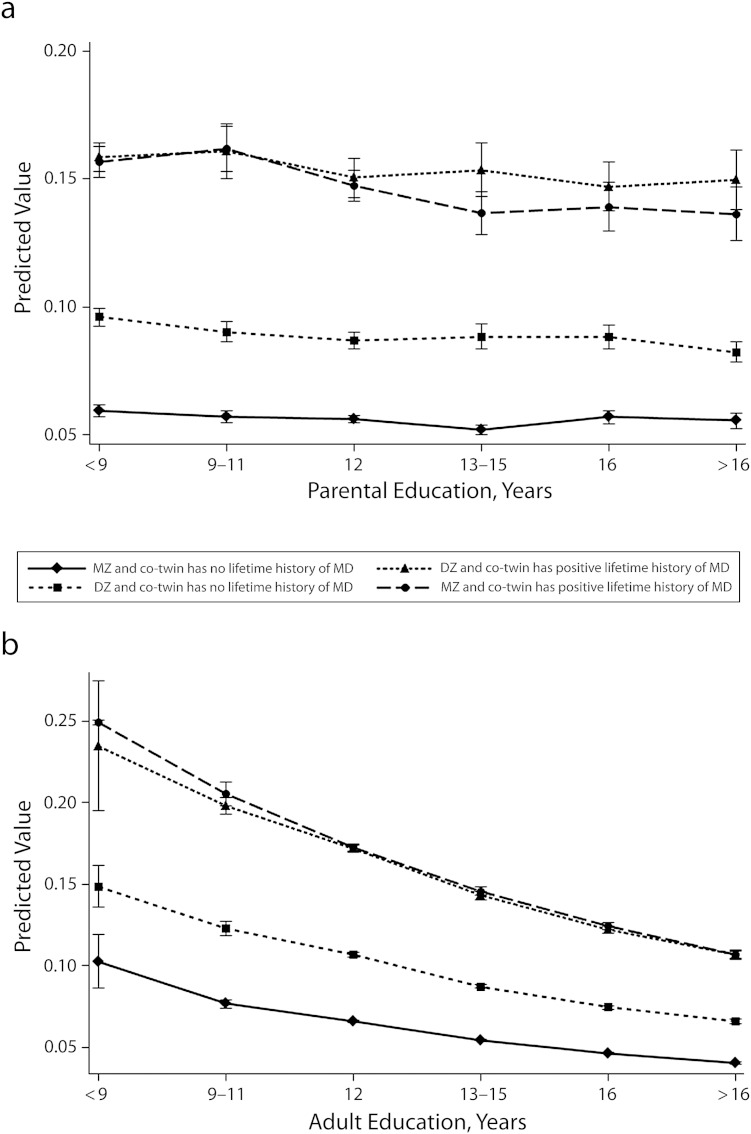

Finally, we turned to the question of gene–environment interaction, Figure 3 shows the predicted probability of lifetime and past year major depression by parental and adulthood education, respectively, stratified by co-twin depression status. Figure 3a illustrates that, as expected, individuals with high genetic risk for depression had a higher likelihood of major depression themselves and that this relationship did not vary by SES of childhood. By contrast, the difference in the slopes for individuals with a co-twin with versus without a history of major depression offered suggestive evidence in that genetic risk for depression might sensitize individuals to the influence of low educational attainment (Figure 3b).

FIGURE 3—

Predicted probability of past year major depression by (a) education of main support in childhood and (b) adulthood educational attainment: Virginia, 1987–1989.

Note. DZ = dizygotic; MZ = monozygotic. Data were adjusted for age and zygosity, stratified by major depression (MD) status of co-twin. For 3b, predicted probability and SE were combined. Whiskers indicate 95% confidence intervals.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined 3 hypotheses of the origin of disparities in major depression: social causation, social drift, and common (genetic or environmental) cause. Overall, we found that even after accounting for genetic risk, the observed SES disparities in depression were consistent with the social causation hypothesis. We found that upward social mobility was associated with lower risk of major depression, but no evidence that social drift was associated with greater risk of depression. We found evidence for a quite modest shared genetic risk for low education and major depression, and no evidence that childhood SES was associated with depression risk, indicating that a common cause model (either because of genetic or environmental factors) did not readily explain social disparities in depression. Finally, we examined the interplay between genetic and environmental sources of covariance between SES and major depression. There was modest evidence of gene–environment interaction, such that having genetic propensity for depression might “sensitize” individuals to the influence of low SES. Previous work indicated that one way genetic risk for depression is expressed is by sensitizing individuals to the negative effects of stressful life events,22 which might be an explanation for these results.

This analysis demonstrated several conceptual issues relevant to examining the joint action and interaction of genetic risk and the social environment. In particular, it highlighted the fact that genetic and environment risk might covary (e.g., gene–environment correlation),23–25 and the environment might be a pathway by which genetic liability is expressed.25 Environmental contexts—such as SES—may moderate expression of genetic risk in several ways (e.g., trigger or buffer a genetic effect).23–27 In this study, there was modest evidence that low SES enhanced the expression of genetic liability for major depression. It was also necessary to acknowledge developmental processes (e.g., in this study, examining both childhood and adulthood SES) in deciding which genetic and environmental factors were most salient for particular health outcomes.25

This study also illustrated some methodological issues that were relevant to examining the joint action and interaction of genetic risk and the social environment. For example, careful attention was needed concerning whether the interaction of genetic and environmental factors was assessed on an additive or multiplicative scale.28–30 The choice to use a particular statistical model can often be driven by the form of available data rather than because of a specific a priori notion that genetic and environmental factors interacted in a multiplicative rather than additive manner.31,32 Careful attention needs to be paid regarding the conceptualization of how the interaction is hypothesized to work (e.g., are positive environmental factors—such as higher SES—thought to buffer genetic risk, or is genetic risk thought to sensitize individuals to the influence of a poor environment?).31,32 Interactions should also be evaluated using multiple approaches (e.g., examining both individuals and twins, as was done in this study) to determine the robustness of findings to model specification; we also note that additive interactions might be more relevant to public health prevention efforts than multiplicative ones.27–32

These findings should be interpreted in light of study limitations. Our primary analysis was focused on the relationship between depression and education; education tends to be completed early in the life course, before peak onset of depression. Other measures of SES (e.g., wealth, receipt of public assistance) were not available. We only examined 1 form of psychopathology; these relationships might vary for other disorders.11 This study was restricted to non-Hispanic White women interviewed approximately 20 years ago, and thus findings might not generalize to other demographic groups, and should be replicated in more recent and diverse cohorts. SES of parents was assessed by self-report, and in some cases twins disagreed; however, the majority of disagreements were between adjacent categories. We had limited statistical power to definitively identify the best fitting bivariate twin model, and some of the risk estimates were based on a limited number of discordant (particularly for education) cases, which resulted in wide CIs; however, the results presented were broadly consistent with previous work on the genetic and environmental contributions to major depression16 and education.33 Also, approximately 6% of respondents were missing data on household income; however, results using this indicator of SES were consistent with those using education (for which all respondents had complete data). Thus, we did not feel that these missing cases substantially influenced our findings. Finally, some have questioned whether the drift versus causation model is appropriate for understanding disparities in major depression,9 and it is possible that the relevance of socioeconomic processes differed for subpopulations (e.g., recent immigrants). This study also had a number of strengths. The sample was derived from a population-based twin registry, major depression was assessed using a validated instrument, and this study is one of the few to evaluate multiple hypotheses of the origin of socioeconomic disparities in depression simultaneously.

As we illustrated, twin samples offered a means to examine the joint action and interaction between genetic liability and the social position. These approaches were complementary to studies of specific polymorphisms, which provided suggestive, but far from definitive, evidence of gene–environment interactions relevant to depression risk.34

Acknowledgments

B. Mezuk is supported by a Career Development Award from the National Institute of Mental Health (K01-MH093642).

Human Participant Protection

This study was approved by the institutional review board at Virginia Commonwealth University, and all participants provided informed consent.

References

- 1.Jarvis E. Insanity and Idiocy in Massachusetts: Report of the Commission on Lunacy (1855) Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Srole L, Langner TS, Michael ST, Opler MK, Rennie TAC. Mental Health in the Metropolis: The Midtown Manhattan Study. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hollingshead AB, Redlich FC. Social Class and Mental Illness: A Community Study. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown GW, Harris T. Social Origins of Depression: A Study of Psychiatric Disorder in Women. New York, NY: Tavistock Publications; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muntaner C, Eaton WW, Miech R, O’Campo P. Socioeconomic position and major mental disorders. Epidemiol Rev. 2004;26(1):53–62. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodman A, Joyce R, Smith JP. The long shadow cast by childhood physical and mental problems on adult life. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(15):6032–6037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016970108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dohrenwend BP, Levav I, Shrout PE. Socioeconomic status and psychiatric disorders: the causation-selection issue. Science. 1992;255(5047):946–952. doi: 10.1126/science.1546291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eaton WW. A formal theory of selection for schizophrenia. Am J Sociol. 1980;86(1):149–158. doi: 10.1086/227207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eaton WW, Muntaner C, Bovasso G, Smith C. Socioeconomic status and depressive syndrome: the role of inter- and intra-generational mobility, government assistance, and work environment. J Health Soc Behav. 2001;42(3):277–294. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jonsson U, Goodman A, von Knorring A, von Knorring L, Koupil I. School performance and hospital admission due to unipolar depression: a three-generational study of social causation and social selection. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(10):1695–1706. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0476-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miech RA, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Wright BRE, Silva PA. Low socioeconomic status and mental disorders: a longitudinal study of selection and causation during young adulthood. Am J Sociol. 1999;104(4):1096–1131. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kendler KS, Gatz M, Gardner CO, Pedersen NL. A Swedish twin study of lifetime major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):109–114. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kendler K, Prescott C. Genes, Environment, and Psychopathology. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stansfeld SA, Clark C, Rodgers B, Caldwell T, Power C. Repeated exposure to socioeconomic disadvantage and health selection as life course pathways to mid-life depressive and anxiety disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46(7):549–558. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0221-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kendler KS, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Health AC, Eaves LJ. A test of the equal-environments assumption in twins studies of psychiatric illness. Behav Genet. 1993;23(1):21–27. doi: 10.1007/BF01067551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kendler KS, Prescott CA. A population-based twin study of lifetime major depression in men and women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(1):39–44. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray ET, Hardy R, Strand B, Cooper R, Guralnik J, Kuh D. Gender and life course occupational social class differences in trajectories of functional limitations in midlife: findings from the 1946 British birth cohort. J Gerontol A Bio Sci Med Sci. 2011;66A(12):1350–1359. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith BT, Lynch J, Fox C et al. Life-course socioeconomic position and type 2 diabetes mellitus: The Framingham Offspring Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(4):438–447. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kessler RC, McLeod JD. Sex differences in vulnerability to undesirable life events. Am Sociol Rev. 1984;49(5):620–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-RL. I: History, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(8):624–629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neale MC, Cardon LR. Methodology for Genetic Studies of Twins and Families. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kendler KS, Kessler RC, Walters EE et al. Stressful life events, genetic liability, and onset of an episode of major depression in women. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(6):833–842. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.6.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dick DM. Gene-environment interaction in psychological traits and disorders. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2011;7:383–409. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kendler KS, Baker JH. Genetic influences on measures of the environment: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2007;37(5):615–626. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rutter M, Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Gene-environment interplay and psychopathology: multiple varieties but real effects. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47(3-4):226–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pescosolido BA, Perry BL, Long JS, Martin JK. Under the influence of genetics: how transdisciplinarity leads us to think social pathways to illness. Am J Sociol. 2008;114(suppl 1):S171–S201. doi: 10.1086/592209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bronfenbrenner U, Ceci SJ. Nature-nurture reconceptualized in developmental perspective: a bioecological model. Psychol Rev. 1994;101(4):568–586. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.101.4.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsuang MT, Bar JL, Stone WS, Faraone SV. Gene-environment interactions in mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 2004;3(2):73–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shanahan MJ, Hofer SM. Social context in gene-environment interactions: retrospect and prospect. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60(special issue 1):65–76. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kendler KS, Gardner CO. Interpretation of interactions: guide for the perplexed. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(3):170–171. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.081331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Walker AM. Concepts of interaction. Am J Epidemiol. 1980;112(4):467–470. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson WD. Effect modification and the limits of biological inference from epidemiologic data. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44(3):221–232. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heath AC, Berg K, Eaves LJ et al. Education policy and the heritability of educational attainment. Nature. 1985;314(6013):734–736. doi: 10.1038/314734a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duncan LE, Keller MC. A critical review of the first 10 years of candidate gene-by-environment interaction research in psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(10):1041–1049. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]