Abstract

To regulate stress responses and virulence, bacteria use small regulatory RNAs (sRNAs). These RNAs can up or down regulate target mRNAs through base pairing by influencing ribosomal access and RNA decay. A large class of these sRNAs, called trans-encoded sRNAs, requires the RNA binding protein Hfq to facilitate base pairing between the regulatory RNA and its target mRNA. The resulting network of regulation is best characterized in E. coli and S. typhimurium, but the importance of Hfq dependent sRNA regulation is recognized in a diverse population of bacteria. In this review we present the approaches and methods used to discover Hfq binding RNAs, characterize their interactions and elucidate their functions.

Keywords: Hfq, sRNA, ncRNA, Protein-RNA interactions

1. Introduction*

Bacteria employ small regulatory RNAs (sRNAs) to control gene expression [1, 2]. In bacteria, sRNAs are critical for bacterial survival under adverse conditions as well as to express virulence factors [3]. There are two main types of sRNAs in bacteria. Cis-encoded transcripts originate from the same locus as the genes or operons they regulate, and have 1:1 correspondence with them. This class includes riboswitches and natural antisense transcripts. Riboswitches are RNA motifs encoded within the mRNA that modulate gene expression through structural rearrangements in response to a regulatory signal [4]. Natural antisense transcripts are RNAs transcribed from the opposite strand of the gene and act by base pairing with perfect complementarity to their target [5]. Unlike the cis-encoded sRNAs, trans-encoded sRNAs, which are the focus of this article, are transcribed from a different locus than their targets and act through imperfect base pairing. In this way they often regulate multiple mRNAs, forming a web of regulatory activities that occur in response to the environment of the bacterium [1]. Often, trans-sRNAs act to positively or negatively regulate the translation of target mRNAs by freeing or blocking the ribosome binding site or targeting a message for degradation [6]. Interactions that occur between a trans-sRNA and its targets often require the RNA binding protein Hfq [1]. Hfq facilitates these interactions by stabilizing RNA-RNA duplex formation, aiding in structural rearrangements, increasing the rate of structural opening or by increasing the rate of annealing (Figure 1A) [7–10].

Figure 1. Hfq-RNA Complex Formation and Hfq Binding Faces.

A. Hfq binds sRNAs and mRNAs with similar affinity. Hfq may bind either the mRNA or sRNA first before forming the ternary complex. B. Crystal structures of Hfq-AU5G (PDB ID: 1KQ1) and Hfq-polyA (PDB ID: 1HK9) superimposed. AU5G binds the proximal face and polyA binds the distal of the homohexamer.

Hfq is widely conserved in bacteria and about half of all gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria express it [11, 12]. In the case of hfq mutant or deletion strains, regulatory effects of sRNAs fail to occur even though the sRNAs are transcribed in response to environmental cues. Phenotypes of these mutants typically include: slowed growth rates, increased cell size, and increased sensitivity to stress [13–15]. Hfq has also been recognized as a virulence factor in many bacteria including Vibrio cholerae, and Salmonella typhimurium where hfq deletion strains fail to colonize, regulate motility or regulate outer membrane protein expression [12, 16, 17].

Hfq forms a donut shaped homohexamer and has been shown to have two well characterized RNA binding sites (Figure 1). In E. coli, sequences that are A/U rich and typical of sRNAs bind to the proximal surface of Hfq while A rich sequences typical of mRNAs bind to the distal surface [18–21]. The proximal site was first characterized by a crystal structure of S. aureus Hfq bound to AU5G RNA and showed that the RNA wrapped itself around the central pore of the protein in a circular manner (Figure 1B). Biochemical analyses later showed that Hfq binds to short A/U rich stretches that are preceded or followed by a stem-loop structure sometimes found in a central location of the RNA and more recently at the rho-independent terminator [22–24]. The binding of A-rich sequences to the distal face was first defined by a series of mutations to the distal face that led to disruption of polyA binding [19]. Some years later the specificity for the distal face interaction was further elucidated in a study of the interaction of Hfq with the mRNA rpoS as being an AAYAA motif, where Y is a C or a U [25]. These results were further verified by investigation of the interactions of Hfq with two more mRNAs, fhlA and glmS, genomic SELEX, as well as a crystal structure of E. coli Hfq bound to polyA RNA (Figure 1B). The motif has been described as AAYAA, (ARE)x, and most recently as (ARN)x [20, 25, 26]. The nomenclature for this motif has evolved to (ARN)x as the binding site was found to be less specific than AAYAA and the acronym ARE was already in use to describe A/U-Rich Elements in eukaryotic mRNAs [20, 27]. Hfq binds to sRNAs and mRNAs with similar affinity. In vitro, the order of binding does not appear to matter with respect to formation of tertiary complexes of duplex annealing (Figure 1A). Crystal structures of Hfq from other organisms reveal some species specific RNA interactions. While S. aureus Hfq binds A/U rich sequences in common with E. coli it has recently been shown that the distal site binds an (RL) motif, similar to B. subtilis, and in contrast with the E. coli (ARN)x motif [18, 20, 28]. The RL motif is a two nucleotide repeat where R is purine specific and L is a non-specific linker. A signature sequence difference in RL binders is a phenylalanine at position 30 [18]. This residue makes the R site selective for adenosine by creating a pocket and providing stacking stabilization. While the biological consequences of these differences in distal site binding specificity is not fully understood, conservation of key binding residues suggests delineation between gram-positive versus gram-negative organisms and the way sRNA/Hfq-dependent gene regulation is used in these organisms [18, 28]. Crystal structures and binding studies of two Hfq proteins from cyanobacteria suggest that the proximal site binding of these proteins is not specific for A/U rich RNAs as seen in other bacterial Hfqs. In addition to the well characterized proximal and distal surfaces the lateral surface and the C-terminal extension have also been shown to bind to RNA [29–31]. It has been proposed that the lateral surface binds to polyU tracts located in the body of an sRNA while the polyU tract at the 3' end of an sRNA anchors the transcript to the proximal face of Hfq [30]. The role of the C-terminal domain in RNA binding remains murky but structural and biochemical studies suggest that it may bind to longer RNA molecules and/or increase interaction specificity by recognizing additional motifs within an RNA [29, 31].

Identification of Hfq binding RNAs, characterization of their structure and interactions with Hfq as well as unraveling their functions is fundamental to gaining an understanding of this complex regulatory network in bacteria. The complexity of the sRNA regulation has gradually come into focus over the last decade and now it is clear that this network is indeed vast. The ability of one sRNA to regulate multiple mRNAs and one mRNA to be regulated by multiple sRNAs as well as the regulation of mRNAs that serve as transcriptional regulators themselves add to the complexity of the network [32–34]. In E. coli and S. typhimurium ~30–35 Hfq-binding sRNAs have been discovered and approximately ~ 25% of all S. typhimurium mRNAs bind Hfq in vivo, making the number of potential RNA binding partners for Hfq in the cell very large [35–38]. Thus despite high levels of Hfq expression, it is believed that the availability of Hfq is often limiting in the cell [39, 40]. There is also evidence that Hfq and/or Hfq-RNA complexes may also engage in protein-protein interactions with RNaseE, PNPase, poly(A) polymerase, RNA polymerase, the degradosome and the ribosome which provides mechanistic insight but also implies additional complex biological roles [41–45]. While Hfq is abundant in the cell observations tell us that it is a limiting factor which is not surprising given the plethora of RNA and protein binding partners possible for Hfq [39, 40, 46, 47]. Still, Hfq is able to coordinate a rapid cellular response to stress, in 1–2 minutes [48–50]. How is Hfq able to successfully perform this job? While several plausible theories based on current evidence exist, many of which have been recently reviewed [51], it is critical to continue studying Hfq-RNA interactions at three different levels: discovery, biophysical characterization, and functional analysis. Finally, since so much of our understanding comes from a small set of organisms it is important to branch out into other bacterial species to increase our understanding of this complex and fascinating regulatory network.

The goal of this review is to provide a brief overview of some of the key techniques used to investigate and characterize Hfq-RNA interactions and to provide the reader with insight into the strengths of various methods and how they should optimally be applied. We have structured the article as if the reader were new to the field of Hfq-associated regulatory RNAs and needed to know what the fundamental questions are and how to go about answering them. In Section 2 the identification of binding partners will be discussed. The main question here is to whom does Hfq bind? There will also be insight into the function of the interaction. Section 3 focuses on the biophysical nature of Hfq-RNA interactions. Where do RNAs bind on Hfq and where does Hfq bind on RNAs? What is the effect of Hfq binding on RNA secondary structure and duplex formation? What are the relative contributions of thermodynamics versus kinetics in Hfq-RNA interactions? The last section focuses on questions surrounding the function of Hfq-RNA binding. What are the biologically relevant outcomes of Hfq-RNA interactions and how do they impact the fitness and virulence of bacteria?

2. Identification of binding partners

The first step in studying Hfq-RNA interactions and gaining insight into their regulatory outcomes is to identify the binding partners. Strong binding between Hfq and its sRNA or mRNA partners and the effects of Hfq on transcript and protein levels can be used to identify novel sRNAs and their targets. Three main methods will be discussed; co-immunoprecipitation of RNAs with Hfq, proteomics and transcriptomics in hfq knockout strains, and SELEX.

2.1 Co-immunoprecipitation

Hfq co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) is one of the most common methods used to identify Hfq binding RNAs. The co-IP step can be performed by isolating Hfq bound transcripts using an Hfq specific antibody, an epitope tagged Hfq, or by incubating cellular extracts or purified RNA pools with an affinity tagged Hfq. Once the binding partners have been isolated there are several methods for determining which RNAs have been pulled down. Early work used microarrays, shot gun cloning, and enzymatic sequencing. More recently, the advent of inexpensive high-throughput sequencing (HTS) has altered the experimental landscape and is now the most common approach to deconvolute the pull-down [36, 38, 52, 53]. One of the best features of co-IP is the ability to directly identify Hfq-RNA interactions in a high-throughput fashion, but some limitations occur due to the potential for non-specific interactions. Another drawback is that the lengthy protocol can result in degradation of large mRNA transcripts.

A critical decision that the researcher has to make concerns the growth conditions of the bacteria. It is important because many transcripts are short lived or only expressed under specific growth conditions and thus may go undetected in one experiment while being highly abundant in another. In order to detect as many transcripts as possible several different conditions should be selected. Some researchers may wish to select a stress condition of particular importance in a pathogen of interest, or a growth phase that is known to exhibit significant expression changes in the absence of Hfq. Whatever the conditions, it is critical to recognize that it is most likely that many Hfq binding RNAs may not be present and thus go unnoticed.

Incorporation of a polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis size fractionation step is another key decision. It depends on whether the goal is to find sRNAs only or to also capture mRNA targets. The feasibility of sequencing a large number of isolated transcripts also plays into this equation. Size fractionation is helpful to enrich for sRNAs as well as to limit the size of the library that requires sequencing. The affordability of HTS makes the latter concern less relevant than in the past. It is ideal to use HTS without a size fractionation step so that both Hfq binding sRNAs and mRNAs are discovered simultaneously.

The choice to use an Hfq specific antibody or an affinity/epitope-tagged Hfq protein for the RNA pull down should be made with the following considerations. An Hfq specific antibody is available for E. coli but to use this technique in interesting pathogens, either the E. coli antibody must cross react with that organism's Hfq or a new antibody must be developed [54]. Sonnleitner et al. and Christiansen et al. have successfully developed antibodies in P. aeruginosa and L. monocytogenes for this purpose [52, 55]. The other option is to use an affinity or epitope-tagged Hfq which provides an excellent opportunity to perform this experiment without first preparing an antibody. Ramos et al. took advantage of the affinity tag method and discovered 24 novel sRNA in B. cenocepacia [56]. They purified a His-tagged Hfq protein that was subsequently incubated with an isolated RNA pool followed by capture of the Hfq-RNA complexes using Ni-NTA agarose magnetic beads. An epitope-tagged Hfq system was developed in Sittka et al. in which they created a chromosomal FLAG-tagged Hfq protein (Figure 2A) [36]. To obtain the Hfq bound RNAs they incubated a FLAG antibody with cell lysates and separated the bound from unbound RNAs using protein-A sepharose beads. One thing to keep in mind when using an epitope tag is that its presence may perturb RNA binding and therefore bias the results. The Hfq antibody or the FLAG-tag antibody detection directly from cell lysates provides the benefit of detecting transcripts that were bound in vivo.

Figure 2. Discovery of Hfq Binding RNAs.

A. Co-IP of Hfq bound RNAs using chromosomally FLAG tagged Hfq (adapted from Sittka et al.) [36]. Cellular extracts from hfqFLAG cells are prepared and co-IP with an α-FLAG antibody is performed. RNAs are extracted and modified to incorporate a polyA tail and 5'phosphate. A 5' adapter is ligated followed by cDNA synthesis and high-throughput sequencing to identify the bound RNAs. B. Genomic SELEX (adapted from Lorenz et al. and Zimmermann et al.) [68, 130]. A genomic library is created by random priming using primers that incorporate a T7 promoter and primer binding sites for reverse transcription and PCR. The library is transcribed to RNA and a binding reaction with Hfq is performed. Bound complexes are selected using filter binding. Bound RNAs are recovered from the filter followed by RT-PCR. The cycle is repeated multiple times followed by sequencing to identify the aptamers.

Once the Hfq bound RNAs have been isolated they can be identified by microarrays, shot gun cloning, enzymatic sequencing, or high-throughput sequencing. A pioneering study used direct detection of bound RNAs on genomic microarrays to detect 20 novel sRNAs as well as a number of mRNAs that interact with Hfq [38]. The sensitivity of this method was unparalleled at the time but required the use of an antibody specific for RNA:DNA hybrids as well as a species specific high density microarray. These features limit its use in other bacteria of interest. Co-IP has also been used in combination with enzymatic RNA sequencing and shotgun-cloning (RNomics [53]) to identify novel sRNAs in L. monocytogenes and P. aeruginosa respectively. The use of enzymatic sequencing was a success because it identified Hfq binding sRNAs in L. monocytogenes for the first time, but it required large amounts of RNA and time consuming sequencing gels making it unsuitable for large scale analyses. Similarly, shotgun cloning was able to identify new sRNAs on a small scale but the lengthy cloning and use of capillary electrophoresis make it sub-optimal for high-throughput investigations. That being said these approaches are successful and make use of techniques that are readily available and relatively low cost.

The advent and recent affordability of HTS has likely made it the ideal choice for identification of Hfq bound transcripts from co-IP. This method obtains sequence information for a large number of RNAs at one time making it more feasible to identify both mRNAs and sRNA in a wide variety of growth conditions. It does not have species specific requirements so it can be used regardless of sample origin. Also, the alignment of the cDNA clusters can often determine the 3' and 5' ends of sRNAs. This method was implemented by Sittka et. al. in combination with FLAG-tag Hfq co-IP to identify 1,253 mRNAs that were bound to Hfq as well as large number of sRNAs [36]. However, this method as well as any other protocol involving cDNA synthesis may have a bias against sRNAs because of the restricted capability of reverse transcriptase to process through highly stable structures [57].

Classification of an Hfq bound RNA as an sRNA or an mRNA is the final critical step in the discovery process. Once the transcript has been identified and its location mapped to the genome several criteria can be used to make the determination. mRNAs are often already annotated in the genomes of sequenced bacteria so assignment as an mRNA is relatively simple. If the species is not annotated, one can look for the classic characteristics of an open reading frame (ORF), including; conserved regulatory sequences, a ribosome binding site, and reduced conservation of the third nucleotide of codons. For sRNAs there are no hard and fast rules for required features. One seemingly tried and true predictor of an sRNA is an orphan rho-independent terminator and many searches incorporate this criterion [52, 53, 58]. Although, it should be noted that there are examples in multiple bacterial species of regulatory RNAs that also code for short peptides, recently reviewed by Vanderpool et al. [59]. A length component is often incorporated as well. This criterion can be implemented during gel fractionation or when scoring sequencing results and commonly enforces a general size range of ~ 50–500 nucleotides [38, 55]. Genomic location is also typically considered because historically, sRNAs have been found to be transcribed as standalone transcripts in intergenic regions [36, 38]. This requirement is a good place to start in a novel organism, but the results will not be comprehensive. It has been observed that sRNAs can be derived from the 3' ends of transcripts and from genes coding for tRNAs [35, 58]. So, for an exhaustive search, one should not only look in intergenic regions. Conservation of sRNA candidates among closely related species can also be taken into consideration but can become difficult as the sequences rapidly become disparate. Often, sRNAs involved in metabolic processes will be well conserved among related species but sRNAs found in pathogenicity islands or in cryptic prophages are species specific [58]. Given that most of these rules apply to some but not all sRNAs it is advisable to combine them in a way that can help identify the sRNAs but will not be exclusionary to certain types.

While cross-linking has not been used to pull down Hfq associated RNAs thus far we would be remiss not to mention the cross-linking and immunoprecipitation (CLIP) assay due to its success in identifying RNA-protein interactions [60–63]. This method uses UV cross-linking to create covalent bonds between RNA and protein that are in direct contact with one another. Cross-linking at 254 nm occurs due to the natural photoreactivity of nucleic acids as well as some amino acids at this wavelength. A typical CLIP experiment involves in vivo cross-linking followed by lysis and partial digestion of RNA. The RNP complexes are purified by co-IP to select for the protein of interest and the bound RNA fragments are identified using high-throughput sequencing. This technique identifies bound RNA and also provides information on the location of the interaction between the binding partners. Chi et al. used CLIP to identify miRNA and mRNA binding partners of Argonaute in the mouse brain [60]. Cross-linking provides advantages over co-IP alone. First, cross-linking directly reflects RNA-protein interactions in vivo because the bonds are formed in whole cells rather than lysates or purified RNA pools. This excludes the formation of unnatural complexes due to the lack of cellular components that result in the detection of biologically irrelevant interactions. Second, the RNAs obtained more accurately reflect direct targets because RNAs bound to a protein that associates with the bait protein are not pulled down. A disadvantage of CLIP, especially for potential use in the Hfq system, is the low cross-linking efficiency of purine bases. This caveat may limit the identification of mRNA binding partners. The success that cross-linking has had in the miRNA field makes the CLIP assay a logical candidate for use in the discovery of Hfq associated sRNAs and mRNAs as well as identification of Hfq binding motifs.

2.2 Transcriptomics and Proteomics

Transcriptomics and proteomics provide information on the effect of Hfq on transcription and translation which can lead to the identification of Hfq binding partners as well as insights into function. These methods do not provide evidence for a direct interaction between Hfq and RNA nor can it distinguish between primary and secondary effects, so interpretation must be performed with care. In addition, some changes in transcript/protein levels may only occur during specific conditions or may be too small to detect, so there is potential to miss or overlook important regulatory events.

Transcriptomics in wild type and hfq deletion strains can lead to detection of Hfq binding sRNAs and mRNAs. In these analyses wt and Δhfq cells are often grown under various conditions, followed by isolation of total RNA and detection using microarrays or high-throughput sequencing. This method identifies RNAs whose transcription or decay is significantly affected (directly or indirectly) by Hfq [36, 64, 65]. A direct effect occurs when Hfq acts on the transcription rate or decay rate through physical contact with the gene or mRNA. An indirect effect occurs when a change in transcript level occurs due the action of Hfq on some other DNA, RNA, or protein. Transcriptomic analysis only, cannot distinguish these mechanisms, so it is often coupled with another technique like Hfq co-immunoprecipitation [36]. The growth conditions can also be manipulated to disfavor the effects of transcriptional regulators that are known to be connected to Hfq [66]. Mapping the affected transcripts to the genome, identifies the genes and their functions, if annotated, can be suggested. For example, transcriptome profiling of S. enterica, S. maltophilia, and Y. pestis found that Hfq affects the levels of genes associated with stress response and virulence [36, 64, 65]. Published studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of microarrays to detect transcript levels but they require a high density oligonucleotide array to be available for the bacteria of interest [65]. Roscetto et al. have taken advantage of the increased affordability of HTS in lieu of microarrays to identify mRNAs that show changes in transcript levels due to Hfq, to predict novel sRNAs and to annotate transcription start sites in S. maltophilia [65]. They sequenced RNA from wild type and hfq mutants as well as in the presence and absence of 5' phosphate dependent terminator endonuclease (TEX). Comparison of RNAs from wild type and mutant strains scored changes in transcript levels caused by Hfq, while the TEX treatment allowed them to annotate transcription start sites and identify potential sRNAs. Northern analysis and qRT-PCR can be used to validate observed changes in transcript abundance although it has been noted that the abundance levels measured by qRT-PCR are lower than those obtained in microarray results [64].

Proteomics can be used to characterize global control of gene expression at the post-transcriptional level by monitoring which proteins show significant expression changes in the presence and absence of Hfq. Examining protein levels can identify targets that are regulated translationally and would have been missed by transcriptome analysis. This approach often uses 2-D gel electrophoresis to identify proteins with differential expression but the technique resolves only a fraction of total protein, so proteins with low abundance, low solubility, or that co-migrate with another species may not be detected. These studies have been done with the intent to find Hfq-sRNA targets rather than both sRNAs and mRNAs. Using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, Barra-Bily et al. were able to identify a set of 55 proteins with expression differences in an hfq mutant in S. meliloti [67]. Proteomics alone cannot distinguish between transcriptional and post-transcriptional/translational regulation, but a sample-matched procedure that combines transcriptomics and proteomics can resolve this problem. This method was used in S. Typhimurium by using part of a culture for RNA isolation and microarray analysis and the other part for proteomics analysis using LC-MS [13]. Ansong et al. compared the change in transcript levels with the change in protein content to distinguish between the two types of regulation. They found that the majority of effects in hfq mutant strains were due to post-transcriptional events. Proteins from their results were validated by western blot analysis and agreed with previously published results. Another benefit of using simultaneous transcriptomics and/or proteomics approach is that no tagging or isolation of Hfq was required.

2.3 Genomic SELEX

A significant problem that plagues all of the techniques described above is that they require the RNA to be transcribed at detectable levels under the selected condition. While the use of HTS has made it easier to obtain data from multiple growth conditions, it is unreasonable to expect a researcher to assay all possible growth or stress conditions under which an sRNA could be expressed. A complimentary approach to discover Hfq binding RNAs avoids the issue of growth dependent expression by screening a genomic library for Hfq binding RNAs in a systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) experiment (Figure 2B) [68].

The uncoupling of RNA detection and growth conditions occurs by creating a genomic library via random priming of all endogenous DNA sequences behind a T7 promoter. Transcription of the library yields a pool of RNAs that represents the entire genome of the bacteria; therefore, all possible transcripts are present regardless of growth condition. The caveat however, is that the RNAs start and stop at random genomic positions and do not correlate with actual transcription start sites or termination sites. Once the RNA pool is created, Hfq is added and allowed to bind. The bound and unbound transcripts are separated using filter binding and the enriched transcripts are reverse transcribed and amplified. The PCR products obtained are transcribed into a new RNA pool and the selection process is repeated. In their protocol, the whole cycle was repeated 9–10 times at which point the Hfq binding RNAs were sequenced and mapped to the genome. They also verified that the aptamers that were obtained bound to Hfq in a cellular environment by employing a yeast three hybrid assay. This technique was able to recover many known Hfq binding sRNAs and mRNAs although it missed some of the most well know and prolific species. This oversight may be due to a lower affinity of these for Hfq than the selected aptamers or to reverse transcription stops as a result of their highly structured nature. It is also possible that some transcripts were overlooked because they were misfolded or amplified in a manner that altered Hfq affinity. A notable result from this study was the large number of aptamers that corresponded to the antisense strand of protein coding genes. This differs from the focus on trans-sRNAs as Hfq binders. The location of these cis-antisense transcripts near start codons and intervening sequences between genes in operons suggests a potential role for Hfq in translation regulation, gene processing and expression within polycistronic messages.

3. Folding and Interactions

Once the question of to whom Hfq binds has been answered, one may begin to consider the nature of the interactions. A large amount of biochemical and crystallographic data are now available to support the RNA binding surfaces on E. coli Hfq. It is generally accepted that A/U rich elements typical of sRNAs bind to the proximal surface and that (ARN) tracts typical of mRNAs bind to the distal surface [19–22, 25]. Existing evidence also supports a role for the lateral surface in binding U-rich sequences found in the body of sRNAs and for the C-terminal extension in binding longer RNA fragments [29–31]. Crystal structures in other organism including S. aureus and B. subtilis have shown that species specific Hfq-RNA binding occurs [18, 28]. With the discovery of sRNAs and Hfq in pathogenic bacteria as well as their link to virulence, the need to characterize the specificity of binding and the binding surfaces of these Hfq homologs is of particular interest. Crystallographic data provide tremendous insight into these questions but this review will focus on biochemical and biophysical techniques that are readily available to a wide variety of labs.

Another question is where does Hfq bind on mRNAs and sRNAs? This question is more difficult because binding sites that have been characterized often have unique features based on the specific RNA studied. This heterogeneity has prevented the formation of an exacting definition. A general trend seen in Hfq binding sites on sRNAs is the presence of single stranded A/U rich regions flanked on one or both sides by a stable stem loop structure [22, 69–72]. These motifs have been found in the body of the RNA as well as at the very 3'end of the RNA where it is part of the polyU stretch of the rho-independent terminator [22–24]. The importance of Hfq interactions with mRNAs did not become apparent until recently, so these sites have just started to be defined. However, several well-studied examples provide valuable insight and it has been established that in most bacteria the sequence of the binding site is (ARN)x and is present in highly structured 5'UTRs of regulated messages [25, 26, 73]. All three validated sites lie to the 5' side and in close proximity to their sRNA binding sites. When the (ARN)x motif of these messages is mutated it results in decreased ternary complex formation and dysfunctional regulation.

Duplex formation between an sRNA and mRNA is often central to the regulatory outcome desired in response to stress and environment. Hfq serves to aid in duplex formation by remodeling RNA, by increasing the local concentration of the two RNA molecules, or by increasing the rate of structural opening [7–10]. The effect that Hfq has on duplex formation is vital to understanding how a specific regulatory pair functions. Hfq is an RNA chaperone and it has been proposed to remodel RNAs into more favorable structures for duplex formation. This activity has been shown in some instances and not others; therefore, investigating this possibility in an RNA of interest can provide insight into how Hfq promotes duplex formation [22, 54, 74]. Elucidating the relative contribution of thermodynamics and kinetics to the Hfq RNA interactions is also important in understanding how a specific regulatory outcome is achieved. In a cellular environment Hfq is very abundant but it has been shown to be limiting and that RNAs have to compete with each other for binding [39, 40, 46, 47]. The ability of a regulatory pair to affect its outcome is dependent upon its ability to compete for Hfq. This competition is modulated by how tightly and how fast it associates and dissociates from the secondary and ternary complexes with Hfq.

3.1 Electrophoretic Mobility Gel Shift Assay (EMSA)

EMSA is a very common, easy and adaptable assay that can be used to answer a wide variety of questions regarding Hfq RNA interactions. The technique is based on the change in migration of RNA upon binding of a protein. Use of P32 labeling and phosphorimaging allows for accurate quantitation. The assay can be used qualitatively to determine whether or not an RNA binds Hfq or quantitatively to allow the determination of thermodynamic and kinetic parameters.

An EMSA should be performed on a native polyacrylamide gel poured at the percentage optimal for migration of the bound complex into the gel and for resolution of the free and bound RNA complex, which is dependent on the size of the RNA. Typical gel percentages are 4–8% and may also contain 3–5% glycerol which can improve complex resolution. The acrylamide:bisacrylamide ratio used is typically 29:1 to accommodate the large size of the Hfq-RNA complex and gels are typically run in 0.5–1X TBE buffer often at 4°C to stabilize the complex during resolution. While the use of EDTA in the running buffer deviates from the conditions used in RNA conformational studies, we have found it is not detrimental and simplifies the experiment by eliminating the need for buffer recirculation and long running times.

It is important to obtain a homogenously folded RNA population, but due to the complex structure of some sRNA and mRNAs this can be difficult. Multiple folding conditions can be evaluated by changing monovalent salt conditions, magnesium ion concentrations and annealing conditions. Typical monovalent salt concentrations are from 100 mM to 500 mM and magnesium concentrations are from 1 mM to 10 mM. sRNAs with regions of self-complementarity have exhibited the tendency to form homodimers which must be avoided [19, 75]. This tendency can be exacerbated by high magnesium ion concentrations. The RNA should be annealed prior to binding by heating to 75–95°C followed by a period of cooling. The temperatures and durations vary between labs but we have found that 1 minute at 90°C in the absence of magnesium followed by slow cooling at room temperature for 30 minutes works for many RNAs.

Binding specificity can be influenced by the salt concentration as well as addition of competitor RNA. It is well known that Hfq can interact non-specifically with RNAs mainly due to electrostatic interactions between the negatively charged RNA and the overall positive charge of Hfq. This non-specific interaction is stronger at low salt concentration. While non-specific binding is highly dependent on salt, specific RNA-protein interactions are less dependent on ionic strength. This is due to the added stabilization provided by the favorable free energy associated with the specific contacts made. The general outcome is that as salt concentration is increased the interaction becomes more specific and the affinity decreases. This effect has been observed with Hfq as it has been shown that high salt concentrations will decrease the affinity of some sRNAs for Hfq [76]. We have found that the salt conditions used for folding provide a good balance between specific and non-specific interactions. It is common in RNA-protein binding assays to add a competitor RNA to reduce non-specific binding. This addition should be considered carefully in the case of an Hfq-RNA binding reaction, as Hfq has been shown to specifically bind tRNA and poly(A) RNA which may inadvertently alter the measured binding constants [77].

Once the assay conditions are selected, the goal of the experiment should be chosen from several options: the presence or absence of an interaction between the RNA and Hfq can be determined, the effect of Hfq on duplex formation can be assessed or thermodynamic and kinetic parameters can be obtained. If thermodynamics is the focus, equilibrium dissociation constants (Kd) can be determined by titrating an RNA with increasing amounts of Hfq so that a range of free and bound complexes is present. The concentration of P32 labeled RNA in this reaction should be trace, at least 10–100 fold below the Kd. The Hfq concentrations should cover two orders of magnitude above and below the Kd and should maximize the number of data points in the binding transition region. Trace conditions simplify the Kd calculation by allowing one to assume that the free protein concentration changes insignificantly. When determining a Kd the binding reaction must be incubated long enough to achieve equilibrium, typically 5–30 minutes at room temperature. For very tight binders longer incubation may be required due to slow off rates. The binding reactions are then combined with loading buffer containing glycerol or sucrose, loading dyes of choice and then resolved. It should be recognized that loading dyes may affect migration of RNP complexes and can be omitted to avoid problems. A drawback of EMSA is that the gel may need to be run for several hours to adequately resolve the complexes.

To obtain thermodynamic parameters the free and bound bands are quantified from the phosphorimage. The percent bound RNA is determined and then plotted versus the log Hfq concentration. These points are then fit by a nonlinear least-squares analysis to a cooperative binding model (for Hfq the cooperativity values typically fall between 2 and 3). Multiple binding events may occur because one RNA may bind multiple Hfq hexamers. This effect can be observed in the case of Hfq binding DsrA (Figure 3) as well as with other RNAs. This case may be dealt with by using a partition function for two sites or by simplifying the data to consider only the K1 events in which case all shifted bands are summed to yield a “bound” state. The analysis of the gel shown in Figure 3A demonstrates the two site fitting method based on equations 1–3.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where ƒDH I and ƒDH II are the fractions of DsrA in complexes D•HI or D•HII, the Hfq concentration is of monomers, K1 and K2 are binding constants for the first and second site, n is the Hill coefficient and the function QDH in (3) is the sum of the terms for each bound state. To obtain a binding constant for each state one simultaneously fits equations (1–3) while if only the first binding constant is desired an equation like (4) can be used.

| (4) |

The Kd determined in equation (4) should have a value similar to the K1 value obtained from the partition functions in equations (1–3). Some labs use the dual binding fit whereas others use the single site. The choice of which fitting to use is based on perceptions of physiological relevance. The decision is not straight forward as the topic is still debated. The binding of two Hfq hexamers by one RNA may be an effect only observed in vitro due to the trace conditions of RNA and the large concentrations of Hfq. This condition may not exist in the cell because of competition for Hfq. A recent study by the Weichenrieder group particularly calls the biological relevance of multiple Hfq binding into question because they found strong evidence that an sRNA binds both the proximal and lateral surfaces of Hfq [30]. If this is the case it is unlikely that one sRNA could bind multiple Hfq protein except under in vitro conditions of trace RNA.

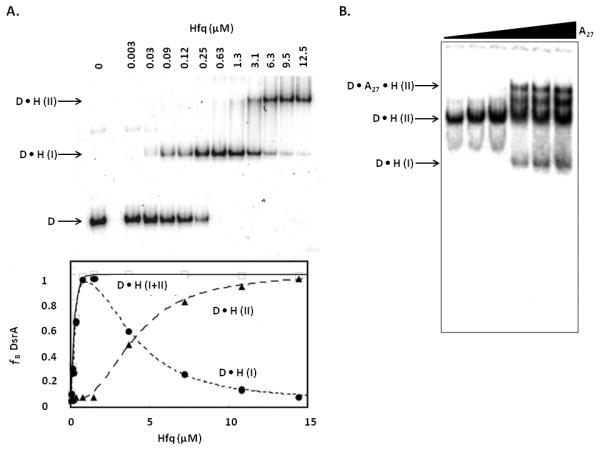

Figure 3. Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays.

A. Two site fitting used for DsrA and Hfq (image from Lease and Woodson) [75]. P32 labeled DsrA was titrated with 0–12.5 μM Hfq monomer. The D•H(I) band is DsrA bound to one Hfq hexamer and the D•H(II) band is DsrA bound to two Hfq hexamers. Plot of the fraction of DsrA bound (ƒB) versus Hfq concentration showing the fitting of each site independently and combined. B. Competition assay of A27 with pre-formed D•H(II) complex (image from Mikulecky et al.) [19]. Titration of increasing concentrations of A27 (0–3 μM) leads to the formation of a ternary complex.

A variation of this technique, called a competition assay, can be used to assess which face of Hfq an RNA is binding as well as its ability to bind compared to other RNAs (Figure 3B). This method is particularly useful for determining binding of RNAs by Hfq homologs whose binding specificities have not yet been determined. This approach uses a preformed Hfq-RNA complex which is then challenged with increasing concentrations of a competitor of interest. The ability of a competitor to promote dissociation of the RNA from the preformed complex can then be assessed by monitoring an increase of the free RNA. To use this assay to gain information about the Hfq binding face specific for an RNA of interest, the preformed complex should contain Hfq and an RNA for which the binding face is known. The ability of a competitor molecule to remove the known RNA from Hfq indicates that they bind the same face and a lack of ability to compete indicates binding on a different area of Hfq. One specific application of this technique was used by Mikulecky et al. to determine the RNA binding sites on E. coli Hfq (Figure 3B). In that experiment a DsrA-Hfq complex was preformed and unlabeled A27 was added at increasing concentrations. As the amount of A27 increased the formation of DsrA-Hfq-A27 occurred, indicating that Hfq binds DsrA and A27 on different faces and that they act independently.

EMSA can also be used in a straightforward experiment to evaluate the effect that Hfq has on duplex formation of a regulatory RNA pair. The Aiba group studied the duplex formation of SgrS and ptsG over time in the presence and absence of Hfq to investigate if Hfq could enhance the rate of duplex formation [78]. To explore the effect of Hfq they added Hfq to the binding reaction and then extracted Hfq with phenol before loading the reaction onto the gel. Before treatment with phenol it is advisable to first digest with proteinaseK to prevent the RNA from transferring to the organic phase along with Hfq. They found that within one minute a significant amount of duplex had formed in the presence of Hfq, suggesting that Hfq strongly enhances the rate of duplex formation. Rapid duplex formation in the presence of Hfq highlights a limitation of EMSA. The time it takes to prepare the samples may exceed the time it takes for the complex to form so one may not be able to quantify fast events, although quench-flow techniques can resolve this issue.

Kinetic parameters can also be determined using EMSA by following binding reactions over a time course. The fraction of each complex can be plotted against time and fit to rate equations. This application was used to demonstrate the effect of Hfq on the rate of DsrA and rpoS annealing [25]. In this experiment the two RNAs were monitored over time for the formation of duplex, in the presence and absence of Hfq. Using this technique Soper and Woodson were able to show that Hfq increased the rate of duplex formation ~ 30 fold [25].

The use of EMSA to evaluate the binding of Hfq to truncated RNA constructs has been used to identify the portions of RNA that are necessary for binding. This approach was used to identify the lengths of the 5'UTRs of fhlA and rpoS required for Hfq binding and sRNA-mRNA duplex formation [25, 26]. In both cases constructs with varying 5'UTRs were made and assayed for their ability to form a duplex. Salim and Feig, as well as Soper and Woodson, were able to determine the relevant 5'UTR length for optimal duplex formation using this approach.

3.2 Filter Binding Assays

Filter binding assays allow for the measurement of both thermodynamic and kinetic properties of Hfq-RNA binding [76]. Unlike EMSA where complexes are separated in a gel matrix this assay employs a double filter to separate the bound from unbound RNAs. The top membrane is nitrocellulose and binds the RNA-protein complexes and the bottom membrane is a charged membrane that binds free RNA. The two membranes are seated in a dot blot apparatus and samples are drawn through by applying a vacuum. Quantitation of the RNA and RNA-protein complexes is performed using phosphorimaging. Some particular benefits to this assay are the ability run on high-throughput 96 well plates, to manipulate the volume of the reactions to obtain optimal detection, high sensitivity and low cost. This method is particularly useful for determining fast kinetics of binding due the rapid rate of complex separation [76]. One potential drawback however, is that you can no longer resolve multiple binding events; as discussed earlier those events may or may not be relevant in a given study. Equilibrium dissociation constants can be obtained by titrating the RNA with increasing amounts of Hfq and fitting the data to standard binding isotherms. Kinetic parameters can also be determined by keeping the RNA and protein concentrations constant and varying time. Control experiments in the absence of protein should be performed to account for non-specific nucleic acid binding to the nitrocellulose membrane. This technique was implemented to investigate and compare the binding properties of nine different sRNAs [76]. Olejniczak found that the sRNAs had similar affinities for Hfq but varied in their ability to compete for Hfq binding. The binding properties determined using the filter binding assay agreed with those obtained using other methods under the same conditions.

3.3 Surface Plasmon Resonance

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) has been used to study the thermodynamics and kinetics of Hfq binding to both sRNAs and mRNAs. SPR monitors changes in the refractive index near the surface of a sensor that occur due to binding events. One strength of this technique is the simultaneous, real time measurements of both kinetic and thermodynamic parameters. In this technique, one binding partner is immobilized on the sensor surface and the other is continuously flowed in. When a binding event occurs, the refractive index increases and when the complex dissociates, the refractive index decreases. The results are plotted as response units versus time and are most commonly fit to a simple 1:1 Langmuir binding model to obtain kon and koff values. The Kd can then be calculated by dividing the koff by kon.

There are several steps that must be taken in order to execute a successful SPR experiment investigating an Hfq-RNA interaction. Though theoretically it shouldn't matter, it is most typical to immobilize the RNA on the surface of the sensor and flow in Hfq. The larger size of Hfq provides a greater change in response when the two molecules interact [79]. Also, the negative character of the chip surface can repel the RNA if it is chosen as the analyte [80]. For a high affinity interaction like that of Hfq with an RNA, the RNA should not be immobilized at too high of a concentration or problems associated with mass transfer could arise [79]. We have found that ~ 3 fmol works well in the case of fhlA. To prepare the RNAs for SPR, they are biotinylated at the 5' end and purified using a spin column. It is critical that the samples are very pure as the presence of contaminants could affect the SPR signal or interact with the analyte and impact binding. A benefit of SPR is that it is a label free approach but it does require immobilization which could lead to changes in binding. Unfortunately, this technique is not suitable for high-throughput analysis as only a few samples can be analyzed at a time and each analysis requires 5–15 minutes.

This approach has been used to analyze the kinetics and thermodynamics of Hfq binding to the mRNAs fhlA and ompA and to the sRNA MicA [7, 26]. The Wagner group used SPR in addition to EMSA and filter binding to obtain Kd values, association and dissociation rates for ompA and MicA [7]. In both cases the values obtained were similar between the three techniques demonstrating the value of each in obtaining reliable data. In the study of fhlA-Hfq, SPR was used to demonstrate that the (ARN)x motif is important for distal site interaction and to support a wrap-around model for fhlA binding. This model suggests that the RNA binds to both surfaces of Hfq at once [26]. To investigate the importance of the (ARN)x site contact with Hfq, the ability of constructs with or without the site to interact with Hfq were compared. It had previously been shown that fhlA interacts with both Hfq surfaces, so the data was fit to a parallel binding model where fhlA can interact with either side of Hfq independently before forming the complex where both sites are bound. The step where both sites are bound was omitted from the fitting because the technique cannot register that type of unimolecular rearrangement. The inability of SPR to detect internal rearrangements of this type is its shortcoming. The fhlA construct that contained both the proximal and distal site had two low nanomolar Kds whereas the construct with only the proximal binding site had only one, indicating that the (ARN)x site is important for distal surface binding. Salim and Feig also performed a competition experiment by pre-binding Hfq to fhlA and then flowing in either A18, DsrA, or both. All three scenarios led to faster than direct dissociation rates which suggests that fhlA binds in a wrap-around fashion. These experiments highlight the use of SPR to obtain information beyond thermodynamic and kinetic parameters.

3.4 Other Biophysical Methods

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) is most widely recognized in studying DNA-Protein interactions and protein biophysics but has also been successfully used to obtain thermodynamic information and binding stoichiometry of an of RNA and protein interaction [19]. ITC directly measures the heat released or absorbed during a chemical reaction by monitoring the power consumption required to keep a sample cell and a control cell at the same temperature over the course of a reaction [81]. Direct measurement allows for a more accurate determination of thermodynamic data than a gel shift. Some issues that have limited its usefulness are the need for a large sample size as well as the inability to deconvolute the energy from the multiple binding interactions or from structural rearrangements.

Fluorescence anisotropy measures the change in polarized light emitted from a fluorophore in solution during a binding event [82]. This change is a result of decreased tumbling of the labeled molecule upon binding of a larger molecule. This phenomenon allows for the evaluation of a molecules' binding properties by providing a direct measure of the bound to free ligand ratio. Fluorescence is a safer option than radiolabeling but it is less sensitive and much larger which may affect binding. A benefit of this approach is that it is solution based which omits a separation step and therefore may more accurately reflect true equilibrium binding. This approach can be applied to Hfq-RNA systems by labeling the RNA molecule with 6-carboxyfluorescein, titrating it with increasing amounts of Hfq and observing the change in anisotropy [83–86]. The data are plotted as anisotropy versus time and fit by a nonlinear least-squares analysis to a two step binding model.

Fluorescence anisotropy was used to investigate the RNA binding surfaces on Hfq in a similar fashion as EMSA. Sun and Wartell assessed a variety of Hfq mutants followed by binding studies with RNA substrates [84]. In agreement with previous studies, they found that DsrA binds to the proximal surface and that A18 binds to the distal surface of Hfq. They also used the fluorescence anisotropy data to determine reaction stoichiometries which led to some ambiguities regarding the binding ratio of the A18 Hfq interaction. Uncertainty in the amount of Hfq required to saturate binding of the labeled RNA caused an underestimation in the amount of bound RNA, leading to a discrepancy with ITC data. This incongruity was later resolved by allowing flexibility in the variable that accounts for the fraction of bound RNA [85]. Determining an accurate binding model of other than two state reactions can be challenging using fluorescence anisotropy if the anisotropy change between the two states is not well defined and/or if there is cooperative binding. EMSA is better suited for this because of the added information provided from visualization of discrete bands that represent different complexes. This observation can provide the binding stoichiometry and guide the correct selection of a binding model.

3.5 Chemical and Enzymatic RNA Modification

The use of chemical and enzymatic analysis of RNAs can be employed to determine the secondary structure of an RNA, the Hfq footprint and structural changes upon Hfq binding. Additionally, some techniques allow structure determination and protein interaction mapping in vivo. One approach uses a complementary set of enzymatic and/or chemical modifications that react with the nucleotides in different ways to provide a complete assessment of each nucleotides environment. To determine Hfq binding sites on the RNAs, the probes can be used in the presence and absence of Hfq. In the presence of Hfq some nucleotides will become protected, indicative of a binding site. In addition to seeing protection, some nucleotides may become more reactive, indicative of secondary structure rearrangements. Two different methods can detect the cleavages or modifications. One route uses reverse transcription with an end labeled primer to detect both scissions and modification for RNAs of any length (by using multiple primers). The other technique uses end labeled RNA for direct detection but can only be used for shorter molecules, typically less than 300 nucleotides in length. The fragments obtained from these methods are then separated on denaturing polyacrylamide gels along with one or two ladders that assign the site of cleavage/modification on the RNA. Efforts to obtain a uniformly folded RNA as well as the selection of binding buffer conditions should be taken as discussed for EMSA.

One illustrative example of the use of nucleases was the determination of the effect of Hfq on the sodB mRNA and its regulatory partner, RyhB sRNA [87]. Geissmann et al. used a combination of RNaseA which cleaves 3' to single stranded cytosines and uracils, RNase T1 which is specific for single stranded guanines, RNase I which cleaves any single stranded residue and RnaseV1 that is specific for double stranded regions and provides positive evidence for helical regions. This probe combination allows for sufficient coverage of the RNA to provide an accurate secondary structure. RNases are large and therefore show signs of steric hindrance and care must be taken optimize enzyme concentration and incubation time as the presence of secondary cleavage events can lead to misinterpretation of the data. The data obtained allowed for the accurate determination of secondary structures of the two RNAs as well as footprints pinpointing the Hfq binding site(s). Also, the occurrence of enhanced cleavage at certain residues in the presence of Hfq can show a loop opening event or other rearrangements such as in the case of Hfq binding to sodB mRNA.

Another useful probe is the Tb3+ or Pb2+ ion which cleaves single stranded RNA in a sequence independent manner. The small size of these ions avoids the steric hindrance issues that RNases have, which allows for detection of subtle structural changes upon Hfq binding. The Masse lab used this method to detect an enhanced interaction between the regulatory pair, RyhB and iscS, in the presence of Hfq and the Hfq binding site on the iscS mRNA [88]. The concentration of the ion must be optimized to obtain conditions where less than one cleavage occurs per RNA molecule. The reaction can be quenched at the optimized time with addition of EDTA. Lead(II) has also been used to determine secondary structures in vivo and could potentially be used to map Hfq interaction sites in vivo in the future [89].

Selective 2'-hydroxl acylation analyzed by primer extension (SHAPE) is a chemical modification based technique that takes advantage of the ability of the hydroxyl selective electrophile, N-methylisatoic anhydride (NMIA), to react without sequence specificity with more flexible/accessible nucleotides [90]. The use of SHAPE to determine secondary structures and footprinting provides the advantage of only having to use one chemical modification technique to obtain necessary structural information. Modifications are revealed by reverse transcription and resolution on denaturing gels or by capillary electrophoresis. Capillary electrophoresis analysis allows for a significant increase in throughput and software to analyze the raw data and obtain reactivities for each nucleotide is available [91, 92]. Our lab has successfully used SHAPE in combination with capillary electrophoresis to determine the secondary structures and Hfq footprinting of glmS and fhlA mRNAs [26, 73].

Several considerations are important to successfully implement SHAPE to study RNA-Hfq interactions including: RNA design, RNA folding, RNA modification and primer extension conditions. To detect adduct formation reverse transcription (RT) is used. RT can lead to a loss of information due to pausing at the 3'end during the initiation phase and at the 5'end because of an intense band equivalent to the full length extension product. To avoid this loss of information, the RNA can be inserted into a structured cassette, first described by the Weeks lab, where the RNA is flanked by highly structured hairpins and also an RT primer binding site on the 3'end [90]. While the cassette improves this problem it may still interfere with mapping Hfq binding sites at the polyU tract of the rho-independent terminator since the 3' end is unnatural in these constructs. The stability of the hairpins ensures that the cassette structure does not interfere with the folding of the RNA of interest. To facilitate analysis of many RNAs we have created a modified pUC19 vector containing the cassette behind a T7 promoter so that any RNA of interest can be cloned into the vector and transcribed. The RNA must be renatured prior to modification as described in the previous techniques.

To modify the RNA, NMIA is added at a concentration and time that must be optimized to obtain only one adduct formation per molecule. NMIA +/− reactions are run in parallel so that natural RT stops can be accounted for in the data analysis. In order to obtain footprinting data Hfq +/− reactions can be run as well. Hfq is added to a final concentration of 1 μM hexamer and allowed to bind at room temperature for 30 minutes before reaction with NMIA. After NMIA reaction the RNA is ethanol precipitated or in the case of Hfq + reactions it is first proteinaseK digested and then phenol-chloroform extracted. The primer extension reaction is performed using RNA Superscript III in four separate reactions; NMIA +, NMIA −, and two sequencing ladders created by including ddNTPs into the reaction mixture. Each reaction contains an RT primer with a unique fluorophore that allows identification of the different reactions in the capillary electrophoresis readout.

The reaction is then separated by capillary electrophoresis. Reactivities for each nucleotide are determined by analyzing the raw data with ShapeFinder (Figure 4A) [93]. Data for Hfq + reactivities are obtained from a unique set of reactions that can be run in a parallel lane. The reactivities for the Hfq +/− reactions can then be compared to determine where protection has occurred (Figure 4). The resulting data is used to determine the fold of the RNA using RNAstructure and the Hfq protection can be mapped (Figure 4B) [94]. The structures for fhlA and glmS that we determined using this approach added to the evidence for an important Hfq binding interaction at (ARN)x sites in the 5'UTRs of regulated messages [26, 73]. This method provides accurate, high-throughput structure determination and footprinting. The cost of fluorophore labeled primers is high but the use of a universal RNA cassette makes it a worthwhile one-time investment.

Figure 4. SHAPE Derived Structure and Hfq Footprinting of glmS.

A. Normalized reactivities for each nucleotide in the presence and absence of Hfq (image from Salim et al.) [73]. Double stranded residues are indicated by P1, P2, etc….. and Hfq binding (ARN)x sites are indicated. B. Schematic of the SHAPE derived secondary structure with reactivities and Hfq footprint superimposed. RBS is the ribosome binding site and GlmZ binding site is the binding site of the regulatory RNA. Footprints were deemed weak if Hfq binding resulted in a reactivity change between 0.3–0.59 and strong if the change was > 0.6.

New developments in SHAPE that describe high-throughput analysis and in vivo structure mapping have recently been published [95, 96]. These techniques have not yet been applied to bacterial sRNA systems but hold promise for investigating Hfq-RNA interactions. Lucks et al. recently described high-throughput SHAPE analysis that is able to obtain structural information from an in vitro pool of RNAs that are distinguished from one another using bar-codes [95]. This method is able to obtain quantitative high resolution structure information for hundreds of RNAs in a single experiment. It is important to study RNA in vivo because the biologically relevant structure may exist only in the cellular environment. In addition, RNA-protein interactions are represented in the data. Chang et al. designed two new electrophiles, 2-methyl-3-furoic acid imidizolide (FAI) and 2-methylnicotinic acid imidizolide (NAI), which maintain the selective reactivity to hydroxyl groups but are non-toxic and have a sufficient half life in cells to modify the RNAs. They found that NAI had a higher reactivity and chose to use it to validate their technique by probing the 5S rRNA in mouse embryonic stem cells and in yeast. When SHAPE data was overlaid with the crystal structure, they found that NAI had modified the RNA at the predicted nucleotides in as little as 1 minute. Comparison of in vitro and in vivo SHAPE structures for the 5S rRNA led to the identification of important contact sites with other RNA and proteins. One can easily imagine this technique being used to map the structures of mRNAs and sRNAs that interact with Hfq and to determine Hfq binding sites in vivo. Some potential complexity lies in separating the effect of protein binding and structural changes on the reactivities and declaring the identity of the protein binding partner.

3.6 Isoenergetic Microarray Mapping

Microarray mapping is a unique approach to secondary structure determination, Hfq binding site identification and Hfq derived structure change. The technique is based on the ability of single-stranded RNA regions to hybridize with complementary oligonucleotide probes in contrast to double stranded RNAs [71]. A microarray with probes specific for the RNA of interest is created to match the probe specifications required for the particular target. The structure of the RNA is determined alone and then various complexes can be studied by comparing the hybridization intensity in the presence of other complex components. The incorporation of locked nucleic acid and modified nucleotides are incorporated where necessary to account for varying thermodynamic stabilities of the probes due to the specific sequence. This technique can be used with a broader set of conditions than with chemical and enzymatic assays that often require specific conditions for reactivity. The method is limited by the thermodynamic stability of the target molecule structure and the stability of its interaction with other biomolecules. This approach has been used to determine the structure of DsrA in complex with Hfq and rpoS, and OxyS in complex with Hfq and rpoS or fhlA [97]. Fratczak et al. obtained structures for both sRNAs that agreed with previous data and identified previously suggested Hfq binding sites. They were also able to confirm that the DsrA secondary structure is not altered upon Hfq binding and that Hfq facilitates sRNA-mRNA duplex formation. The broad application of this technology has been minimized because of the large amount of effort that must be invested to create a unique microarray for each RNA of interest.

4. Functional Characterization

The number of Hfq dependent sRNAs identified in various bacterial species is large but only a small set have well defined biological functions. Bacterial sRNAs are not easily grouped into categories that indicate their functions and because of this, the function of these sRNA regulators often have to be elucidated on an individual basis. Many of the techniques discussed in Section 2 to identify Hfq binding mRNAs also give some information about function if the gene has been annotated. In addition to those techniques we will present approaches that allow for the identification of the RNA binding partner, given an Hfq associated sRNA or mRNA of interest (Table 1). Binding partner identification is often the first step after an initial discovery technique. After identifying potential RNA partners it is necessary to validate that the interaction is direct and that there is a real biological effect.

Techniques for Finding RNA Binding Partners

| Technique | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics |

|

|

| sRNA Over Expression |

|

|

| sRNA Pulse Expression |

|

|

| sRNA Knockouts |

|

|

4.1 Bioinformatics

Due to the availability of many bacterial genomes, bioinformatics approaches for the discovery and analysis of sRNAs have flourished. There are many ways that computational tools can be employed to help elucidate the functions of Hfq binding sRNAs and mRNAs, specifically by aiding in the prediction of an RNA binding partner of a given sRNA or mRNA. The most useful aspect of these approaches is the ability to guide lab work to obtain results in a more efficient manner. This guidance saves time and money in the lab. Computational approaches are often not sufficient on their own due to false positives and fake negative feedback and therefore must be validated experimentally. In addition, prior information about the system to be studied is necessary to create a useful tool. These tools have been successful in organisms where Hfq binding sRNAs and mRNAs are well characterized and have the potential to be modified easily to accommodate species specific characteristics of the network. Bioinformatics can be a particularly useful tool when studying pathogens or bacteria that are hard to grow and manipulate in the lab. These studies could be facilitated by an initial computational analysis followed by experiments in a model bacterium.

One of the earliest examples of employing bioinformatics to identify a target mRNA was a simple blastn search to identify a 16 nucleotide region of complementarity between MicC and ompC [98]. These searches are useful in identifying interactions that have long regions of continuous complementarity which is unfortunately a minority of Hfq-dependent sRNAs. Despite this limitation, J rgensen et al. have very recently used blastn to identify an mRNA target of McaS after a proteomics/transcriptomics approach failed, demonstrating its utility and use as a starting point for RNA binding partner identification [99]. This approach is also useful because it requires no prior knowledge besides the requirement of complementarity between the two RNAs to guide the search. Another relatively simple bioinformatics approach is to look for the presence of a transcription factor binding motif. The transcription of some sRNAs is controlled by transcription factors [49, 100]. By identifying the transcription factor that controls expression of the sRNA the function may be apparent based on the role of the transcription factor. For instance, Papenfort et al. were able to identify two σE-dependent sRNAs involved in omp mRNA regulation using this method [49].

Once a set of targets for a given sRNA have been validated, the knowledge of those interactions can guide a computational search for new mRNA targets [101]. Sharma et al. first defined a binding motif for GcvB based on 16 known target binding sites using the MEME (multiple em for motif elicitation) software [102]. By providing the sequences of the know targets the program was able to identify an 8 nucleotide long motif that was present in all but 2 of the mRNAs. To identify previously unknown targets of GcvB the motif was used to search the −70 to +30 regions of all annotated Salmonella protein coding genes using a MAST (motif alignment and search tool) [102]. Frequently, sRNAs interact with mRNAs in this region of the 5'UTR, but this parameter should be chosen based on the known targets of the specific sRNA of interest. Widening this criterion may lead to more false positives. The annotated transcription start sites of the genes should also be taken into consideration. If the interaction was found from −60 to −70 but the RNA is transcribed starting at −50 then the putative interaction is likely irrelevant. The genes that showed a significant match to the motif were then input into TargetRNA [103] to identify the targets that had the strongest base-pairing with GcvB. Overall they obtained 42 potential mRNAs that passed all of the bioinformatic criteria, 4 of the 5 that they chose to validate showed regulation. This technique successfully identified known and new targets that were missed by a transcriptomics approach and demonstrated the utility of a combining bioinformatics with other experimental approaches. A drawback of the method is that a large amount of previous knowledge is needed to train the computational queries. This limits its use in finding interactions for sRNAs that have few known targets or in organisms where sRNAs are not well characterized.

In addition to designing your own unique search strategy there are many accessible programs that have been designed to allow researchers to easily perform bioinformatics studies without designing their own algorithms. These programs and their detailed methods have been recently reviewed by Li et al. so we will just provide a brief overview of a selection of these here [104]. TargetRNA was designed to identify potential mRNA partners given the sequence of an sRNA and the genome of interest. mRNA-sRNA interactions are scored based on the hybridization between the two RNAs without considering intramolecular base pairing or psuedoknots. The omission of the secondary structure of the RNAs is a limitation because the presence of these structures can significantly affect the likelihood of an interaction. The program also provides parameters that can be specified by the user such as seed length and the location of the interaction site relative to the promoter. Overall their approach was able to identify ~ 70% of the RNAs used in the training set. TargetRNA was one of the first programs developed to predict sRNA targets in bacteria. It was designed using a limited amount of known information which may make it less useful than some of the newer programs. That being said it has been successfully incorporated into several recent studies [101, 105, 106].

Many other programs have become available to aid in the identification of mRNA-sRNA interactions. sRNATarget was developed by Zhao et al. by incorporating 35 positive (validated interactions) and 86 negative targets into its training set. Unlike TargetRNA this approach also considers the secondary structure of the RNAs [107]. They were able to obtain a greater accuracy rate for predicting the training set than TargetRNA. The program IntaRNA evaluates RNA-RNA interactions using a complex algorithm based on hybridization and accessibility of the target site [108]. This program is effective but is computationally demanding, whereas an alternate server called RNApredator achieves similar accuracy in less time [109]. The program sTarPicker has been shown to outperform the above methods in target prediction and accuracy of binding site prediction. The key difference in their approach is a two-step hybridization model that first picks targets based on stable seed interactions and then on extended hybridization of the entire binding site [110]. All of these available tools can aid in the discovery of Hfq –associated RNA binding partners when combined with other techniques and therefore contribute to the determination of their biological functions. The current searching methods will continue to evolve as new information about the sRNA regulatory network is learned. Some current insights that may improve predictions are to include requirements for Hfq binding sites in the mRNAs and to focus on known binding motifs for particular sRNAs.

The Collins group took a unique approach to defining the functions of bacterial sRNAs by using a network biology approach that takes advantage of existing microarray data to elucidate the functions of sRNAs [111]. Knowledge of sRNA interactions can often lead to clues about the function of the sRNA. This is the first program to take advantage of the large body of known interactions to make functional predictions for the whole sRNA network [111, 112]. First they applied a Context Likelihood of Relatedness (CLR) algorithm to a compilation of existing microarray expression profiles that were obtained under various conditions [113]. This algorithm identifies regulatory relationships using an inference approach and identified 459 potential targets. They were then able to identify functional enrichment in seven sRNA subnetworks by assigning gene functions to the putative targets. They validated the functional implications of three of these sRNAs. This technique is useful because there are several sRNAs known to regulate multiple mRNAs who all function in a similar physiological process [101, 114]. The identification of that process allows new targets to be inferred based on their involvement in that pathway. This approach was based on microarray data and therefore does not distinguish between direct and indirect interactions. The incorporation of proteomics data would be an improvement. In general, the more data the analysis includes the greater the predictive power. This method can easily be adapted to other organisms with profiling information.

4.2 Manipulation of sRNA Expression

A widely used approach for defining the function of an sRNA is to manipulate its expression. Many variations including over expression, pulse expression and knockouts have been used to identify the mRNA targets of an sRNA or to identify the sRNA regulator of a given mRNA or phenotype. The basic concept behind these experiments is that changing the expression of an sRNA will lead to detectable changes in transcript levels, protein levels or changes in phenotype.

Creating an sRNA over expression strain involves cloning the RNAs into a high copy plasmid behind an inducible or constitutive promoter. It is necessary to place the transcription of the sRNA under control of an alternative promoter because some sRNAs will not be highly expressed under the natural promoter even when present in a high copy number plasmid. The high copy number expression provides for a high level of sRNA transcription which minimizes the effect of any chromosomally derived sRNAs. They should be inserted such that transcription begins at the natural transcription site which if not known can be determined using a technique such as 5'RACE [115]. This approach allows for the study of sRNAs that may be poorly expressed naturally or are toxic to the bacteria. A caveat of sRNA over expression is the potential to cause inadvertent consequences by disrupting the balance of the natural sRNA network and can lead to confusing results.

Given an sRNA of unknown function, a good way to begin characterizing it is to determine the identity of proteins that show changes in expression when it is over expressed. The Wagner group used this approach to identify the regulation of ompA by MicA [116]. They observed differences in protein expression from strains with high, normal or low MicA expression using two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2D-PAGE). Proteins that showed changes of greater than 2.5 fold between the strains were subsequently identified using MALDI-TOF. The protein, OmpA, showed the greatest change in abundance and was subsequently validated as a MicA target. This method was also used by Frohlich et al. to classify SdsR as a regulator of ompD [100]. In this case a significant change in OmpD expression was identified simply from a 1D-PAGE analysis due to its characteristic size, and then verified by northern and western blots. Proteome analysis does suffer from the inability to differentiate between direct or indirect effects, and mRNA stability or translational regulation as the mechanism of control.

In organisms where the majority of sRNAs have been discovered, an sRNA over expression library can be created to screen the effects of a large number of sRNAs on a given mRNA or phenotype. The utility of this approach was demonstrated by the identification of an additional sRNA that regulates rpoS [117]. An sRNA library with 26 Hfq binding sRNAs was created and co-transformed with an rpoS-lacZ fusion. The β-galactosidase output was monitored for significant increases or decreases and led to the identification of four sRNAs previously unrecognized to regulate rpoS. By observing the ability of two of the putative sRNAs to act on rpoS in strains where the positively acting sRNAs were deleted, they were able to determine that the effects produced in the original screen where indirect. In the deletion strains the down regulation of rpoS previously seen no longer occurred. This observation illustrates the need to be aware of effects caused by artificially titrating Hfq from natural sRNAs and target mRNAs, as this can be an issue during sRNA over expression. Mandin and Gottessman went on to further characterize the regulation of rpoS by the sRNA ArcZ as bona fide. A useful feature of this approach is that once an sRNA library has been created it is easy to rapidly screen any target mRNA of interest by simply cloning it into a fusion vector.