Abstract

Background:

Understanding the health care experience of people with dementia and their caregivers is becoming increasingly important given the growing number of affected individuals. We conducted a systematic review of qualitative studies that examined aspects of the health care experience of people with dementia and their caregivers to better understand ways to improve care for this population.

Methods:

We searched the electronic databases MEDLINE, Embase, PsychINFO and CINAHL to identify relevant articles. We extracted key study characteristics and methods from the included studies. We also extracted direct quotes from the primary studies, along with the interpretations provided by authors of the studies. We used meta-ethnography to synthesize the extracted information into an overall framework. We evaluated the quality of the primary studies using the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist.

Results:

In total, 46 studies met our inclusion criteria; these involved 1866 people with dementia and their caregivers. We identified 5 major themes: seeking a diagnosis; accessing supports and services; addressing information needs; disease management; and communication and attitudes of health care providers. We conceptualized the health care experience as progressing through phases of seeking understanding and information, identifying the problem, role transitions following diagnosis and living with change.

Interpretation:

The health care experience of people with dementia and their caregivers is a complex and dynamic process, which could be improved for many people. Understanding these experiences provides insight into potential gaps in existing health services. Modifying existing services or implementing new models of care to address these gaps may lead to improved outcomes for people with dementia and their caregivers.

The global prevalence of Alzheimer disease and related dementias is estimated to be 36 million people and is expected to double in the next 20 years.1 Several recent strategies for providing care to patients with dementia have highlighted the importance of coordinated health care services for this growing population.2–5 Gaps in the quality of care for people with dementia have been identified,6–8 and improving their quality of care and health care experience has been identified as a priority area.2–5

Incorporating the health care experience of patients and caregivers in health service planning is important to ensure that their needs are met and that person-centred care is provided.9 The health care experience of people with dementia and their caregivers provides valuable information about preferences for services and service delivery.10 Matching available services to patient treatment preferences leads to improved patient outcomes11,12 and satisfaction without increasing costs.13 Qualitative research is ideally suited to exploring the experiences and perspectives of patients and caregivers and has been used to examine these experiences for other conditions.14 We performed a systematic review and meta-ethnographic synthesis of qualitative studies exploring the health care experience of people with dementia and their caregivers in primary care settings, and we propose a conceptual framework for understanding and improving these health care experiences.

Methods

Literature search

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) from inception up to August 2011 using medical subject headings and free text terms (Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.121795/-/DC1). We also searched the journals Qualitative Research and Qualitative Health Research. Two authors (J.C.P. and D.P.S.) evaluated the titles and abstracts of the citations to identify potentially relevant studies. The flow of studies through the review process was recorded using standard review guidelines.15

Selection criteria

We included qualitative studies that used either interviews or focus groups to examine the health care experience of people with dementia (as defined by standard criteria) or their caregivers in primary care. We defined care-givers as informal caregivers (e.g., friends or family members). We also included studies that used both qualitative and quantitative methods (i.e., mixed methods studies) within the same study. For these studies, we only included the qualitative data that met our inclusion criteria. We included only studies published in English because of concerns about translating qualitative data.16,17 We also only included studies that described the primary research question, context of the research, study sample and methods used for data collection and analysis. We excluded studies that did not provide information from primary care or that provided only data about the experiences of health care providers.

Quality of studies

We assessed the quality of reporting of included studies using the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ).18 The presence or absence of reporting of each of the 32 items on the COREQ checklist was assessed in duplicate by 2 authors (J.C.P. and D.P.S.) for 20 studies. Because there was a substantial degree of interrater agreement for each COREQ item (average Kappa value > 0.7), the remaining studies were assessed by 1 author (J.C.P.). This method has been used in published systematic reviews of qualitative research.19,20

Data extraction

Information from included studies was extracted by 2 authors (J.C.P. and D.P.S.) and included the following data: country in which the study was performed; number and type of study participants (people with dementia, caregivers or both); study design (interviews or focus groups); principal experiences explored; and the theoretical framework (e.g., grounded theory).

We reviewed the studies in chronological order, and data were extracted until saturation was reached.

Meta-ethnography

We used the qualitative synthesis method meta-ethnography to extract information and synthesize the literature.19,21 Meta-ethnography produces a systematic review that is interpretative, rather than aggregative.22

In a meta-ethnographic analysis, information is categorized as a first-, second- or third-order construct. We first reviewed each primary study and extracted relevant direct quotations (i.e., first-order constructs). The interpretations of the data by the primary study authors were then extracted as second-order constructs. We then used meta-ethnography to synthesize the second-order constructs into third-order constructs, which formed our interpretations of the overarching themes arising from the primary studies. Key themes across studies were derived from the first- and second-order constructs.

The research team met throughout the review process to analyze and discuss the available first-and second-order constructs, resulting in continuous development and refinement of third-order constructs. These constructs were interpreted and organized into an overall health care experience framework.

Results

Selection of studies

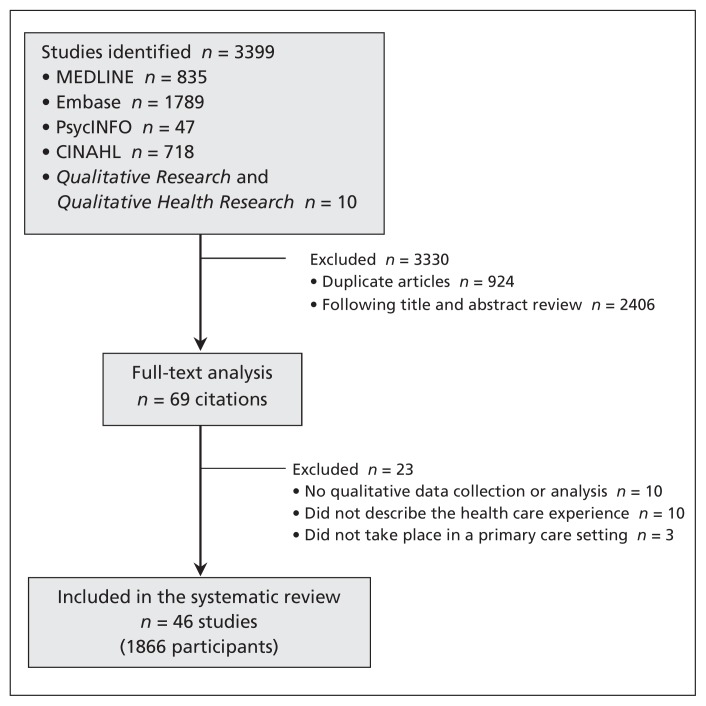

Our electronic database search identified 3399 citations (Figure 1). Of these, we included 46 studies in the final review (Table 1).23–68 These studies included 7 studies involving people with dementia, 25 studies involving caregivers, and 14 studies that involved both groups. Thirty studies used interviews, 10 used focus groups, and 6 used both methods. Most of the included studies presented only qualitative data, but a few studies reported both qualitative and quantitative data.25,26,55 Most studies were conducted in the United Kingdom, United States, Canada or Australia. The total sample size of the studies was 1866, with a mean sample size of 41 participants.

Figure 1:

Flow of studies through the analysis.

Table 1:

Characteristics of the included studies

| Study | Country | Type (no.) of participants | Data collection | Methodology | Principal experiences explored |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morgan and Laing23 | Canada | Caregivers (9) | Interviews | Grounded theory | Impact of a diagnosis of Alzheimer disease from the spouse’s perspective |

| Morgan and Zhao24 | US | Caregivers (217) | Focus groups | Content analysis | Caregivers’ perspective of the physician–patient relationship |

| Beisecker et al.25 | US | Caregivers (104) | Interviews | NR | Perceptions of caregivers about interactions between the physician, patient and caregiver when Alzheimer disease is diagnosed and as it progresses |

| Boise et al.26 | US | Caregivers (53) | Focus groups | NR | Factors to seeking diagnosis |

| Loukissa et al.27 | US | Caregivers (34) | Interviews, focus groups | NR | Experiences of caregivers |

| Bruce and Paterson28 | Australia | Caregivers (24) | Interviews | Content analysis | Adverse elements of interactions with general practitioners and community service providers |

| Chung29 | China | Caregivers (18) | Interviews | Grounded theory | Caregivers’ knowledge and subjective understanding of dementia |

| Butcher et al.30 | US | Caregivers (103) | Interviews | Phenomenological approach | Experience of caring for a family member with Alzheimer disease at home |

| Ericson et al.31 | Sweden | Caregivers (20) | Interviews | Content analysis | Best care from the perspective of family or professional caregivers |

| Smith et al.32 | US | Caregivers (45) | Interviews | Ethnography | Caregivers’ needs |

| Bruce et al.33 | Australia | Caregivers(21) | Interviews | NR | Circumstances regarding referral to community care |

| Hughes et al.34 | UK | Caregivers (10) | Interviews | NR | Ethical issues encountered by caregivers |

| Milne and Wilkinson35 | Scotland | People with dementia (24) | Interviews | NR | Disclosure of diagnosis of dementia |

| Werezak and Stewart36 | Canada | People with dementia (6) | Interviews | Grounded theory | Experience of early-stage dementia |

| Aggarwal et al.37 | UK | Caregivers (28), people with dementia (27) | Interviews | NR | Perspectives on care services and experiences of dementia |

| Bowes and Wilkinson 38 | UK | Caregivers (4), people with dementia (1) | Interviews | NR | Perspectives of older South Asian people with dementia and their caregivers |

| Cloutterbuck and Mahoney39 | US | Caregivers (7) | Focus groups | Content analysis | Barriers and facilitators to diagnosis among black caregivers |

| Teel and Carson40 | US | Caregivers (14) | Interviews | Qualitative description | Experiences of families seeking diagnosis and treatment (barriers and facilitators) |

| Beattie et al.41 | UK | People with dementia (14) | Interviews | Grounded theory | Memory problems, care needs and views on services |

| Connell et al.42 | US | Caregivers (52) | Focus groups | Constant-comparative method | Attitudes toward diagnosis and disclosure of diagnosis |

| Dupuis and Smale43 | Canada | Caregivers and people with dementia (142) | Focus groups | NR | Issues and needs related to community support services |

| Innes et al.44 | Scotland | Caregivers (30), people with dementia (25) | Interviews, focus groups | NR | Positive and negative aspects of service provision |

| Lampley-Dallas et al.45 | US | Caregivers (13) | Focus groups | Thematic analysis | Caregivers’ expectations of health care providers and their perceived level of satisfaction |

| Derksen et al.46 | Netherlands | Caregivers (18), people with dementia (18) | Interviews | Grounded theory | Impact of receiving a diagnosis |

| Downs et al.47 | UK | Caregivers (122) | Interviews | NR | Interactions with general practitioners regarding concerns about early signs of dementia |

| Gruffydd and Randle48 | UK | Caregivers (8) | Interviews | Phenomenological approach | Understanding of Alzheimer disease, psychosocial impact of caring, and extent to which available services are used |

| Harman and Clare49 | UK | People with dementia (9) | Interviews | Interpretative phenomenological approach; content analysis | Illness representations |

| Lindstrom et al.50 | US | Caregivers (19), people with dementia (19) | Focus groups | NR | Attitudes toward medications |

| Lingler et al.51 | US | People with dementia (12) | Interviews | Grounded theory | Experience of living with knowledge of a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment |

| Brown et al.52 | US | Caregivers (9) | Interviews | Grounded theory | Help-seeking process of older husbands caring for wives with dementia |

| Byszewski et al.53 | Canada | Caregivers (41), people with dementia (27) | Interviews, focus groups | NR | Process of dementia disclosure |

| Andersen et al.54 | Canada | People with dementia (4) | Interviews | Analytic inductive paradigm | Expectations of key stakeholders regarding cholinesterase inhibitor treatment |

| Cahill et al.55 | Ireland | Caregivers (28), people with dementia (28) | Interviews | NR | Patients’ satisfaction, attitudes and expectations regarding memory clinics |

| Lecouturier et al.56 | UK | Caregivers (6), people with dementia (4) | Interviews | – | Suggestions for improving the process of diagnostic disclosure |

| Millard57 | Australia | People with dementia (20) | Interviews | Immersion crystallization | Experiences with dementia |

| Robinson et al.58 | Australia | Caregivers (17) | Focus groups | Thematic analysis | Views on dementia diagnosis |

| Hughes et al.59 | US | People with dementia (17) | Interviews | Grounded theory | Pathways and barriers to diagnosis Alzheimer disease for black caregivers |

| Millard and Baune60 | Australia | Caregivers and people with dementia (37) | Interviews, group interviews | Grounded theory | Experience in primary care |

| Robinson et al.61 | Australia | Caregivers (15) | Focus groups | Thematic analysis | Family caregivers’ experiences in accessing dementia information and services |

| Adler62 | US | Caregivers (45), people with dementia (20) | Focus groups | Thematic analysis | Decision-making by people with dementia and their families about driving |

| Hutchings et al.63 | UK | Caregivers (11), people with dementia (12) | Interviews, focus groups | Thematic analysis, grounded theory | Factors influencing decisions to start or stop taking cholinesterase inhibitors |

| Hutchings et al.64 | UK | Caregivers (11), people with dementia (12) | Interviews, focus groups | Thematic analysis, grounded theory | Experiences with cholinesterase inhibitors |

| Livingston et al.65 | UK | Caregivers (89) | Interviews, focus groups | Grounded theory, Content analysis | To identify common difficult decisions and facilitators or barriers |

| Morhardt et al.66 | US | Caregivers (48) | Interviews | Thematic analysis | Barriers to seeking evaluation among communities with low proficiency in English |

| Leung et al.67 | Canada | Caregivers (7), people with dementia (6) | Interviews | Phenomenological epistemology | Obtaining diagnosis |

| van Vliet et al.68 | Netherlands | Caregivers (92) | Interviews | Grounded theory, comparative analysis | Barriers to diagnosis and understanding the diagnostic pathway for early onset dementia |

Note: NR = not reported, UK = United Kingdom, US = United States.

Study quality

The quality of information reported in the included studies varied (Table 2). The number of items reported on the COREQ checklist ranged from 3 items35 to 25 items63,64 (out of 32 items); the mean was 15 items. All but 1 of the studies reported consistent data and findings58 and clarity of major themes.35 Most studies included participant quotations, sampling methods, methods of approach and sample size. Few studies reported interviewer characteristics and participant knowledge of the interviewer, and none reported whether a relationship with the participants was established before the study.

Table 2:

Quality of reporting in the 46 included studies according to Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) criteria

| Criteria | No. of studies who reported the criterion (%) | References of the studies who reported each criterion |

|---|---|---|

| Personal characteristics | ||

| Interviewer or facilitator identified | 9 (20) | 28, 33, 34, 40, 45, 57, 62–64 |

| Credentials | 10 (22) | 33, 34, 40, 45, 48, 51, 57, 62–64 |

| Occupation | 13 (28) | 25, 28, 33, 40, 45, 46, 48, 51, 55, 57, 62–64 |

| Sex | 10 (22) | 28, 33, 34, 40, 45, 51, 57, 62–64 |

| Experience and training | 9 (20) | 30, 42, 45, 46, 51, 63, 64, 66, 67 |

| Relationship with participants | ||

| Relationship established before study | 0 (0) | |

| Participant knowledge of the interviewer | 1 (2) | 28 |

| Interviewer characteristics | 3 (7) | 57, 63, 64 |

| Theoretical framework | ||

| Methodologic orientation and theory identified | 31 (67) | 23, 24, 28–32, 36, 39–42, 45, 46, 48, 49, 51, 52, 54, 57–68 |

| Participant selection | ||

| Sampling | 38 (83) | 23–30, 32–34, 36, 38–42, 44–48, 50–55, 57, 58, 61–68 |

| Method of approach | 36 (78) | 23, 25–28, 30–34, 36, 40–42, 44, 45, 47–52, 54, 55, 57–68 |

| Sample size | 44 (96) | 23–34, 36–42, 44–68 |

| Nonparticipation (number or justification) | 8 (17) | 23, 24, 26, 28, 36, 53, 57, 68 |

| Setting | ||

| Setting of data collection | 27 (59) | 23, 25, 28, 30, 32, 33, 37, 39–43, 45, 46, 48, 50–52, 54, 55, 57, 58, 63, 64, 66–68 |

| Presence of nonparticipants | 10 (22) | 26, 28, 36, 50, 51, 56, 57, 62–64 |

| Description of sample | 38 (83) | 24–30, 32–34, 36, 39–42, 44–55, 59–68 |

| Data collection | ||

| Interview guide | 31 (67) | 24–30, 32–34, 39–42, 44–46, 49–52, 56, 58–65, 68 |

| Repeat interviews | 5 (11) | 23, 24, 35, 36, 55 |

| Audio or visual recording | 38 (83) | 24, 26, 28–34, 37–42, 44–46, 48–65, 67, 68 |

| Field notes | 14 (30) | 23, 27, 28, 32, 34, 37, 38, 40, 44, 51, 62–64, 66 |

| Duration | 24 (52) | 24–31, 39–42, 44–46, 51, 52, 54, 55, 57–59, 62, 67 |

| Data saturation | 7 (15) | 44, 46, 51, 63–65, 68 |

| Transcripts returned to participants | 2 (4) | 59, 65 |

| Data analysis | ||

| Number of data coders | 23 (50) | 25, 33, 34, 39, 40, 42, 45, 46, 49–51, 53–56, 58, 59, 62–66, 68 |

| Description of the coding tree | 36 (78) | 23–26, 28–30, 32, 34, 36, 39–42, 44–54, 57–65, 67, 68 |

| Derivation of themes | 43 (93) | 23–30, 32–34, 36–42, 44–68 |

| Use of software | 22 (48) | 23, 28–30, 33, 36–42, 44, 50, 53, 54, 62–65, 67, 68 |

| Participant checking* | 10 (22) | 23, 32, 36, 39–41, 44, 49, 52, 59 |

| Reporting | ||

| Quotations presented | 40 (87) | 23, 24, 26, 27, 29–46, 48–57, 59, 61–65, 67, 68 |

| Data and findings consistent | 45 (98) | 23–27, 29–57, 59–68 |

| Clarity of major themes | 45 (98) | 23–34, 36–68 |

| Clarity of minor themes | 34 (74) | 23–25, 27, 31, 32, 36, 39–42, 44, 45, 47–55, 57–68 |

Refers to whether the participants provided feedback on the findings.18

Health care experiences

We identified 5 major themes and several sub-themes from the primary and secondary constructs. These themes included seeking a diagnosis; accessing supports and services; addressing information needs; disease management; and communication and attitudes of health care providers. Illustrative first- and second-order constructs are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3:

Themes derived from studies included in the review

| Theme | Second-order constructs | Illustrative quotations (first-order constructs) |

|---|---|---|

| Seeking a diagnosis | ||

| Timeliness of diagnosis | Spouses wanted timely diagnoses with accompanying education about the disease, its course and management. Because the diagnosis was often delayed, families were disadvantaged in their ability to make long-term plans.62 | Caregiver: “We finally got a doctor to say MCI, but is something more, and go to see a neurologist … it took another 6 months. … My husband was probably one of the few people that would plead to be told he had Alzheimer’s.”62 |

| Diagnostic process | Dementia was attributed to “frailty” and to a tendency of people to “lose their mind” as they grow old. Words most often used to express the idea of dementia included “senile,” “confused,” “just getting old” and “old timer’s disease.”39 | Caregiver: “What do you expect [changes in cognition and behaviour]? He’s 72 years old.”39 |

| It takes a frustratingly prolonged process of up to several years to reach a diagnosis, whether by way of primary care or specialist in Alzheimer disease.58 | Caregiver: “A nightmare.”58 | |

| Several caregivers reported that their doctor was unsure or did not know what the problem was.40 | Caregiver: “I think doctors are reluctant to diagnose. I think their reluctance is probably for fear of discouraging family and the patient and also that they are not sure. They can’t be sure, so they’re just reluctant to diagnose as Alzheimer’s.”40 | |

| Assessment process was probing, demoralizing and frightening for several patients.55 | Patient: “It was embarrassing … I couldn’t even draw the house … even a child could do that … it is embarrassing. Maybe I would have done better at home … if I wasn’t so nervous.”55 | |

| Reaction to diagnosis | Most patients and their partners perceived the diagnosis as a confirmation of their suspicions. Patients and caregivers who had no suspicions of dementia tended to perceive the diagnosis as a shock. It is important to know what their expectations are about the diagnosis.46 | Caregiver: “In the past his mother and 2 brothers had suffered from dementia, so we had already considered the possibility.”46 “I didn’t expect him to get this; it’s in my family, not his” (starts to cry).46 |

| Accessing supports and services | ||

| Prolonged path to supports and services | Many caregivers and patients reported that their physician did not discuss next steps or provide current information about community-based services.42 | Caregiver: “I ran into the problem that they give you the information, but they don’t keep it current and up-to-date. You call places … and you get answering machines or you get disconnected or get told “we don’t do that service anymore” … that’s kind of frustrating.”42 |

| Caregivers felt that the whole system was in disarray: despite repeated efforts, they were unable to acquire information about what supports existed, to make contact with appropriate people or to secure services in a timely manner.61 | Caregiver: “One day I spent 3 hours on the phone repeating the same thing over to different people … nobody knows, whoever you ring, nobody is connected with anything.”61 | |

| Specialist services | The process of diagnosis was viewed negatively by caregivers when the dementia was misdiagnosed or not diagnosed. In contrast, the diagnostic process was viewed positively when caregivers felt that specialists had made an accurate diagnosis of dementia.24 | Caregiver: “Jim had been going to an internist who would do anything but say Alzheimer’s … and when Jim finally went to [neurologist], why he said, ‘It’s Alzheimer’s.’ That’s what it is, but doctors are afraid to say it.”24 |

| Meeting patient and caregiver needs through supports and services | All participants eventually consulted a family physician about the changes they had observed in their spouse or family member, and many expressed intense disappointment in the responses they received.61 | Caregiver: caregiver was told to “look it up on the Internet, which wasn’t a very helpful remark – I wanted support, human support.”61 |

| Many participants agreed that their inability to get information and support when they first needed it dampened their efforts to find information.61 | Caregiver: “So I sort of pulled back home and thought oh well, I’m imagining all of this, it’s not happening.”61 | |

| Some participants’ “quest” for information was productive and generated very positive feelings. Sometimes extremely supportive individuals from aged care and dementia support organizations were encountered.61 | Caregiver: “I cried over the phone for an hour … and they listened to me … she says go on, go on talking, they were absolutely wonderful.”61 | |

| Addressing information needs | ||

| Delivery of information | Written information was optimal because caregivers and patients were able to refer back to material when they needed to.27 | Caregiver: “The social worker gave us a lot of information. It is sitting on our kitchen table … we have read some of it.”27 |

| Other suggestions made by patients spoke to the emotional aspects, including a need for empathy.53 | Patient: “There should be more openness to emotion.”53 | |

| Caregivers commonly found that confidentiality impeded them from receiving information, but communication improved if it was clear that the patient gave his or her permission.65 | Caregiver: “On the phone the people would say ‘well we’d have to speak to your mother first to get permission to talk about her issues’ because you know they couldn’t say anything to me … I have to get my mother’s permission to represent her.”65 | |

| Quantity of information | Some of the patients’ perspectives included giving more information about the diagnosis and providing more follow-up information.53 | Patient: “I would like it in layman’s language.”53 |

| Caregivers wanted information but not all at once.65 | Caregiver: “I found, when he was first diagnosed, it was an awful lot to take in, you’re given all this information on what you should be doing, you don’t really want to know it.”65 | |

| Caregivers expressed feelings of frustration toward health care providers (especially at the initial stage of the illness) for not providing them with adequate information about the illness and references for support and resources.27 | Caregiver: “When you take your loved one to be tested, they should inform you of the resources available … they should tell you what to expect, where to go and what to do … nobody tells you what to expect in different stages … they tell you what to expect when you have a baby, but nobody tells you what to do when you reach that stage of life … they just don’t tell you.”27 | |

| Information content | Accessing the health care system, contacting health care professionals and knowing what kind of resources were available and how to access them were some of the issues discussed by caregivers.27 | Caregiver: “We need help with hygiene, grooming services, to take a bath, a shower, wash her hair, help with respite care, nursing homes, home health care agencies.”27 |

| Most comments were about not enough detail being given about the memory tests, the diagnosis and, in particular, the progression of dementia.53 | Caregiver: “I would have liked more about the disease and what it means in the long term.”53 | |

| Disease management | ||

| Knowledge of health care providers | Lack of clinical knowledge about dementia, inattention to patient’s cognitive deficits, and/or unconcern for the well-being of the patient was upsetting to caregivers.26 | Caregiver: “We changed to a lady doctor and the new doctor seemed to be very ill-prepared to treat an Alzheimer patient. We have since changed HMO’s and [my wife’s] new doctor seems to have little interest.”26 |

| Caregivers level of understanding of dementia was greatly influenced by the clarity and consistency of information they received from health care professionals.29 | Caregiver: “The doctors with whom our mother consulted knew very little about dementia. They simply told us that her presentations were a form of senility.”29 | |

| Initiating management | Sometimes caregivers perceived that their family physician would not have referred the patient to secondary care for assessment, diagnosis and treatment prescription if the caregiver have not been proactive themselves.64 | Caregiver: “Now you see if I hadn’t gone and asked the doctor about it I don’t suppose he would have put him on them, he wouldn’t have sent us to see about them.”64 |

| Several families found that assistance came only with prompting.62 | Caregiver: “Nobody told me that he shouldn’t be driving. Nobody asked the last 4 years … or told me about the driving.”62 | |

| Communication and attitudes | ||

| Valuing the perspectives of patients and caregivers | A number of caregivers reported feeling that their concerns were not taken seriously.26 | Caregiver: “The doctor was not even aware of the memory loss — even though I mentioned it to him many times.”26 |

| In cases in which an alternative diagnoses had been given, caregivers gathered and presented “evidence” to physicians for reconsideration.45 | Caregiver: “… to my surprise my husband just started to get lost and that kind of thing … So I began to converse with his doctor about this and every time he go to the doctor he [the physician] would say that he didn’t have a problem. He just couldn’t see it. But I’d say ‘Doctor, you have to work with me because something’s wrong.’”45 | |

| Impact on interaction | Open communication, helpful factual information and empathy went a long way toward family caregivers’ positive feelings about their interactions with the physician.26 | Caregiver: “I felt the doctors did not want to give us the true diagnosis and were not open with us about it. Communication was poor and they were reluctant about discussing the hopelessness of the case with us. We needed honest discussion and their help in facing this tragedy. I needed to be told, ‘We are here to support and guide you through this.’”26 |

| Physicians were expected to be compassionate, understanding, forthright and caring of the caregiver’s mental and physical health as part of the patient–physician relationship.45 | Caregiver: “You have to have the kind of doctor that is caring and will take time to discuss this with you because if you don’t, if you have one that really doesn’t have time for you, it can be terrible.”45 | |

Note: HMO = health maintenance organization, MCI = mild cognitive impairment.

Seeking a diagnosis

The theme “seeking a diagnosis” addresses the early stages experienced by people with dementia and their caregivers. Throughout this process, the timeliness of diagnosis was found to be important. Earlier diagnosis led to easier subsequent transitions. Many people with dementia and their caregivers expressed frustration, uncertainty and disorganization throughout the diagnostic process. The reaction to the diagnosis ranged from shock when dementia was not suspected to relief when dementia was suspected.

Accessing supports and services

The theme “accessing supports and services” describe the experiences of people with dementia and caregivers when seeking assistance from medical and community services. Patients and their caregivers often felt that the path to finding assistance was unnecessarily prolonged. They perceived a lack of knowledge and support by primary care providers about these services, and they consequently experienced difficulty in obtaining help. Specialist services, such as memory clinics, were generally regarded positively, although delays in accessing these services were common. People with dementia and their caregivers stressed the importance of supports or services congruent with their current needs and care goals.

Addressing information needs

The theme “addressing information needs” encompasses how information is delivered and the quantity and content of information. Caregivers and people with dementia often expressed having to “push” to obtain information. They appreciated when information was provided in a clear fashion and when written information was provided. However, although receiving information was appreciated, it was important that the quantity was not overwhelming. Both people with dementia and their caregivers frequently requested information about cognitive testing, medications, disease progression, finances and behaviour.

Disease management

We found that the knowledge of health care providers was a significant factor in the perceived effectiveness of disease management. Patients and caregivers preferred that their physicians be knowledgeable about dementia and its management. Although initiating management is thought of as the responsibility of the health care provider, many caregivers reported that they needed to approach the providers to initiate certain aspects of management. At times people with dementia or their caregivers had to initiate discussions about medications and other concerns (e.g., driving safety).

Communication and attitudes

The theme “communication and attitudes” was important at every stage of the health care experience for patients and caregivers. Valuing the perspectives of people with dementia and their caregivers was viewed as important, and both groups were dissatisfied when they felt discounted. They appreciated when health care providers displayed sensitivity and validation of feelings, as well as treated them with dignity and respect. Poor communication and attitudes led to frustration and could be seen as barriers to treatment. Conversely, good communication and attitudes put patients at ease and facilitated open and compassionate interactions.

Interpretation

We found an extensive body of qualitative research literature examining various aspects of the health care experience of people with dementia and their caregivers. Although the individual studies were conducted in a range of settings, we found similar themes between studies, suggesting that there are certain experiences shared by people with dementia. Both positive and negative experiences were reported in the included studies, although areas of dissatisfaction predominated the literature, highlighting several areas for the improvement of health care services and supports.

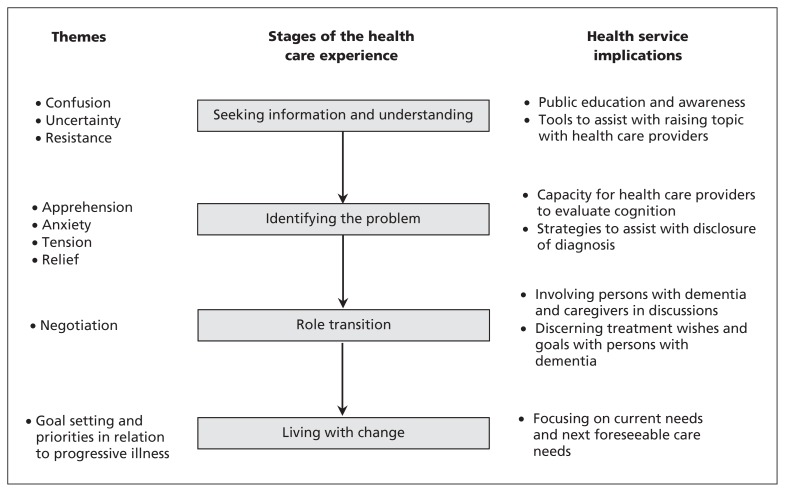

The overall health care experience of people with dementia and their caregivers can be conceptualized as progressing through several phases, each with unique challenges and opportunities for health care providers (Figure 2). The phases of this health care experience are seeking understanding and information; identifying the problem (diagnosis); role transitions following diagnosis; and living with the changes associated with this disease.

Figure 2:

Conceptual framework for the health care experience of people with dementia and their caregivers.

The initial stages of this experience are characterized by a need to seek information and understanding when cognitive changes are noticed by people with dementia or their caregivers. Challenges during this phase included an overall lack of information about dementia in society,69 associated social stigma70 and difficulty on the part of the person with dementia in communicating their symptoms.71 Often this phase is experienced as an extended period of uncertainty and distress. A formal diagnosis of dementia signifies a new stage in the health care experience. Identifying the problem can bring about a mixture of anxiety and relief. Relief may result from finally determining the cause of cognitive and behavioural changes and potentially confirming suspicions. People with dementia and their caregivers may also fear the inevitable progression of the disease. Following diagnosis, the roles assumed by the person with dementia, caregivers and health care providers become more formalized as each begins to prepare to cope with the illness over the long-term. It is important that the patient, caregiver and physician are supported in these new roles. Living with change is often characterized by continuous lifestyle adjustments that allow home and community living. Both people with dementia and their caregivers need practical advice on how to manage everyday life during this time.

Comparison with other studies

Our study is consistent with other recently published syntheses of studies exploring the experience of people with dementia during the process of diagnostic disclosure,72 the experiences of caregivers of people with cognitive impairment,73 and the experiences of health care providers in caring for patients with dementia.73 Together, these studies and our review suggest that the health care experience of patients and caregivers is less than optimal and that several areas of this experience could be improved. Similar findings have also been identified in other patient populations.19,20,74

There are several implications of our findings for health service delivery that may improve the health care experience of patients and caregivers throughout these stages. Given that most of the care for patients with dementia can be provided in primary care settings75 and the limited access to geriatric specialist services,76 there are several ways that primary care providers may be able to improve the care provided to patients with dementia and their caregivers. First, improving communication and attitudes around dementia were identified as important to patients and caregivers, and primary care providers should be aware of person-centred approaches to care.77 Additional education about dementia and its management may help provide health care providers with these skills.73,74,76,78,79

There are several specific changes to dementia care that may improve the health care experience of patients and their caregivers. Outreach and public education strategies can be successful in raising awareness of dementia and helping people identify cognitive changes sooner in order to bring these changes to the attention of primary care providers earlier.80,81 The introduction of screening programs for people at risk of dementia may aid in the early detection in primary care or community settings,82,83 but this requires further study. Education and interventions to equip people with self-management skills and resources have been shown to improve outcomes for a variety of chronic diseases in primary care, and these strategies may also be of benefit in coping with dementia.84 The introduction of services, such as dementia care managers, in primary care teams are promising ways to assist providers in improving the quality of dementia care and behavioural management strategies.85 Psychoeducation for caregivers, including information about dementia and management strategies in primary care or through facilitating linkages to community agencies (e.g., Alzheimer societies66) have been shown to have a major effect on caregiver burden and depression86 and delayed admission to a long-term care facility.87,88 Many of these strategies may be beneficial across the stages of the dementia experience, although some strategies may be more relevant during certain stages. Efforts to improve access to these services and strengthen the quality of dementia care in primary care may facilitate a more positive health care experience.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our study include the systematic method (meta-ethnography) used to identify and synthesize studies.89 Meta-ethnography added more depth than a typical systematic review by providing additional analysis and generation of comprehensive frameworks.89,90 We also evaluated the quality of studies using standard criteria previously used in meta-ethnographic studies.19,20

Although there is debate about the appropriateness of synthesizing qualitative information from different theoretical frameworks,90 we sought to provide a comprehensive understanding of the health care experience by including as many relevant articles as possible in our review. Moreover, there are other examples of published meta-ethnographic studies that have been synthesized across theoretical frameworks to create overarching syntheses.19,20 The quality of reporting of the included studies varied, and some studies may provide more accurate reflections of this health care experience than others.

Conclusion

We found several opportunities to improve the health care experiences of people with dementia and their caregivers. Many of the strategies we suggest for improving service delivery are in keeping with the emphasis on enhancing person-centred care. Through understanding and improving health care experiences, we hope that quality of life and other outcomes will be improved for people with dementia.

Supplementary Material

See also editorial by Flegel at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.131296

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Jeanette Prorok and Dallas Seitz designed the study, with contributions from Salinda Horgan. Jeanette Prorok and Dallas Seitz performed the systematic review. All of the authors participated in the synthesis of data. Jeanette Prorok wrote the manuscript, which was revised for important intellectual content by all authors. All of the authors approved the final version of the manuscript submitted for publication.

Funding: Funding for this project was provided through a Knowledge-to-Action grant (no. 114493) from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The study sponsors had no role in the design of the study, collection, analysis or interpretation of data, the writing of the report or the decision to submit the article for publication.

References

- 1.Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, et al. Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet 2005;366:2112–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Living well with dementia: a national dementia strategy. London (UK): Department of Health; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dementia UK. London (UK): Alzheimer’s Society; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 4.National plan to address Alzheimer’s disease. Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dementia: a public health priority. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laditka JN, Laditka SB, Cornman CB. Evaluating hospital care for individuals with Alzheimer’s disease using inpatient quality indicators. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2005;20:27–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chodosh J, Mittman BS, Connor KI, et al. Caring for patients with dementia: How good is the quality of care? Results from three health systems. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:1260–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vickrey BG, Mittman BS, Connor KI, et al. The effect of a disease management intervention on quality and outcomes of dementia care: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2006;145:713–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stewart M. Towards a global definition of patient centred care: the patient should be the judge of patient centred care. BMJ 2001;322:444–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Say RE, Thomson R. The importance of patient preferences in treatment decisions–challenges for doctors. BMJ 2003; 327:542–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jahng KH, Martin LR, Golin CE, et al. Preferences for medical collaboration: patient–physician congruence and patient out-comes. Patient Educ Couns 2005;57:308–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee Y-Y. Do patient autonomy preferences matter? Linking patient-centered care to patient–physician relationships and health outcomes. Soc Sci Med 2010;71:1811–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loh A, Simon D, Wills CE, et al. The effects of a shared decision-making intervention in primary care of depression: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2007;67: 324–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitzinger J. Introducing focus groups. BMJ 1995;311:299–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the prisma statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Temple B. Qualitative research and translation dilemmas. Qual Res 2004;4:161–78 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Twinn S. An exploratory study examining the influence of translation on the validity and reliability of qualitative data in nursing research. J Adv Nurs 1997;26:418–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tong A, Lowe A, Sainsbury P, et al. Experiences of parents who have children with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Pediatrics 2008;121:349–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morton RL, Tong A, Howard K, et al. The views of patients and carers in treatment decision making for chronic kidney disease: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ 2010;340:c112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell R, Pound P, Pope C, et al. Evaluating meta-ethnography: a synthesis of qualitative research on lay experiences of diabetes and diabetes care. Soc Sci Med 2003;56:671–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morgan DG, Laing GP. The diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: spouse’s perspectives. Qual Health Res 1991;1:370–87 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morgan DL, Zhao PZ. The doctor-caregiver relationship: managing the care of family members with alzheimer’s disease. Qual Health Res 1993;3:133–64 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beisecker AE, Chrisman SK, Wright LJ. Perceptions of family caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease: communication with physicians. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other 1997;12:73–83 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boise L, Morgan DL, Kaye J, et al. Delays in the diagnosis of dementia: perspectives of family caregivers. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other 1999;14:20–6 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loukissa D, Farran CJ, Graham KL. Caring for a relative with Alzheimer’s disease: The experience of African-American and Caucasian caregivers. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other 1999;14:207–16 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruce DG, Paterson A. Barriers to community support for the dementia carer: a qualitative study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2000;15:451–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chung JC. Lay interpretation of dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 2000;12:369–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Butcher HK, Holkup PA, Buckwalter KC. The experience of caring for a family member with Alzheimer’s disease. West J Nurs Res 2001;23:33–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ericson I, Hellstrom I, Ludh U, et al. What constitutes good care for people with dementia? Comparing the views of family and professional caregivers. Texto e. Contexto Enfermagem 2001;10: 128–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith AL, Lauret R, Peery A, et al. Caregiver needs: a qualitative exploration. Clin Gerontol 2001;24:3–26 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruce DG, Paley GA, Underwood PJ, et al. Communication problems between dementia carers and general practitioners: Effect on access to community support services. Med J Aust 2002;177:186–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hughes JC, Hope T, Reader S, et al. Dementia and ethics: the views of informal carers. J R Soc Med 2002;95:242–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Milne A, Wilkinson H. Working in partnership with users in primary care: sharing a diagnosis of dementia. Int J Integr Care 2002;10:18–25 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Werezak L, Stewart N. Learning to live with early dementia. Can J Nurs Res 2002;34:67–85 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aggarwal N, Vass AA, Minardi HA, et al. People with dementia and their relatives: personal experiences of Alzheimer’s and of the provision of care. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2003; 10:187–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bowes A, Wilkinson H. ‘We didn’t know it would get that bad’: South Asian experiences of dementia and the service response. Health Soc Care Community 2003;11:387–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cloutterbuck J, Mahoney DF. African American dementia caregivers: the duality of respect. Dementia 2003;2:221–43 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teel CS, Carson P. Family experiences in the journey through dementia diagnosis and care. J Fam Nurs 2003;9:38–58 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beattie A, Daker-White G, Gilliard J, et al. ‘How can they tell?’ A qualitative study of the views of younger people about their dementia and dementia care services. Health Soc Care Community 2004;12:359–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Connell CM, Boise L, Stuckey JC, et al. Attitudes toward the diagnosis and disclosure of dementia among family caregivers and primary care physicians. Gerontologist 2004;44:500–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dupuis S, Smale B. Probing the major concerns and issues encountered by dementia caregivers. Can Nursing Home 2004;15:36–40 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Innes A, Blackstock K, Mason A, et al. Dementia care provision in rural Scotland: service users’ and carers’ experiences. Health Soc Care Community 2005;13:354–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lampley-Dallas VT, Mold JW, Flori DE. African-American caregivers’ expectations of physicians: gaining insights into the key issues of caregivers’ concerns. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc 2005;16:18–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Derksen E, Vernooij-Dassen M, Gillissen F, et al. Impact of diagnostic disclosure in dementia on patients and carers: qualitative case series analysis. Aging Ment Health 2006;10:525–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Downs M, Ariss SM, Grant E, et al. Family carers’ accounts of general practice contacts for their relatives with early signs of dementia. Dementia 2006;5:353–73 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gruffydd E, Randle J. Alzheimer’s disease and the psychosocial burden for caregivers. Community Pract 2006;79:15–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harman G, Clare L. Illness representations and lived experience in early-stage dementia. Qual Health Res 2006;16:484–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lindstrom HA, Smyth KA, Sami SA, et al. Medication use to treat memory loss in dementia: perspectives of persons with dementia and their caregivers. Dementia 2006;5:27–50 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lingler JH, Nightingale MC, Erlen JA, et al. Making sense of mild cognitive impairment: a qualitive exploration of the patient’s experience. Gerontologist 2006;46:791–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brown JW, Chen SL, Mitchell C, et al. Help-seeking by older husbands caring for wives with dementia. J Adv Nurs 2007; 59:352–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Byszewski AM, Molnar FJ, Aminzadeh F, et al. Dementia diagnosis disclosure: a study of patient and caregiver perspectives. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2007;21:107–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Andersen E, Silvius J, Slaughter S, et al. Lay and professional expectations of cholinesterase inhibitor treatment in the early stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia 2008;7:545–58 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cahill SM, Gibb M, Bruce I, et al. ‘I was worried coming in because I don’t really know why it was arranged’: the subjective experience of new patients and their primary caregivers attending a memory clinic. Dementia 2008;7:175–89 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lecouturier J, Bamford C, Hughes JC, et al. Appropriate disclosure of a diagnosis of dementia: identifying the key behaviours of ‘best practice.’ BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Millard F. GP management of dementia — a consumer perspective. Aust Fam Physician 2008;37:89–92 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Robinson AL, Emden CG, Elder JA, et al. Multiple views reveal the complexity of dementia diagnosis. Australas J Ageing 2008; 27:183–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hughes T, Tyler K, Danner D, et al. African American caregivers: an exploration of pathways and barriers to a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease for a family member with dementia. Dementia 2009;8:95–116 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Millard F, Baune B. Dementia — who cares?: a comparison of community needs and primary care services. Aust Fam Physician 2009;38:642–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Robinson A, Elder J, Emden C, et al. Information pathways into dementia care services: family carers have their say. Dementia 2009;8:17–37 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Adler G. Driving decision-making in older adults with dementia. Dementia 2010;9:45–60 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hutchings D, Vanoli A, McKeith I, et al. Cholinesterase inhibitors and Alzheimer’s disease: patient, carer and professional factors influencing the use of drugs for Alzheimer’s disease in the United Kingdom. Dementia 2010;9:427–43 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hutchings D, Vanoli A, Mckeith I, et al. Good days and bad days: the lived experience and perceived impact of treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease in the United Kingdom. Dementia 2010;9:409–25 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Livingston G, Leavey G, Manela M, et al. Making decisions for people with dementia who lack capacity: qualitative study of family carers in UK. BMJ 2010;341:c4184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Morhardt D, Pereyra M, Iris M. Seeking a diagnosis for memory problems: the experiences of caregivers and families in 5 limited English proficiency communities. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2010;24:S42–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Leung KK, Finlay J, Silvius JL, et al. Pathways to diagnosis: exploring the experiences of problem recognition and obtaining a dementia diagnosis among Anglo-Canadians. Health Soc Care Community 2011;19:372–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.van Vliet D, de Vugt ME, Bakker C, et al. Caregivers’ perspectives on the pre-diagnostic period in early onset dementia: a long and winding road. Int Psychogeriatr 2011; July 1:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ayalon L. Knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease in four ethnic groups of older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2004;19:51–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hinton L. Working with culture: a qualitative analysis of barriers to the recruitment of Chinese–American family caregivers for dementia research. J Cross Cult Gerontol 2000;15:119–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Adams WL. Primary care for elderly people: Why do doctors find it so hard? Gerontologist 2002;42:835–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bamford C, Lamont S, Eccles M, et al. Disclosing a diagnosis of dementia: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2004; 19:151–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cook C, Fay S, Rockwood K. A meta-ethnography of paid dementia care workers’ perspectives on their jobs. Can Geriatr J 2012;15:127–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Iliffe S, De Lepeleire J, Van Hout H, et al. Understanding obstacles to the recognition of and response to dementia in different European countries: a modified focus group approach using multinational, multi-disciplinary expert groups. Aging Ment Health 2005;9:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hogan DB, Bailey P, Carswell A, et al. Management of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. Alzheimers Dement 2007;3:355–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Iliffe S, Wilcock J, Haworth D. Obstacles to shared care for patients with dementia: a qualitative study. Fam Pract 2006;23:353–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lee L, Weston WW. Disclosing a diagnosis of dementia: helping learners to break bad news. Can Fam Physician 2011;57:851–2 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pimlott NJG, Persaud M, Drummond N, et al. Family physicians and dementia in Canada: Part 2. Understanding the challenges of dementia care. Can Fam Physician 2009;55:508–9 e1–7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yaffe MJ, Orzeck P, Barylak L. Family physicians’ perspectives on care of dementia patients and family caregivers. Can Fam Physician 2008;54:1008–15 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mol MEM, van Boxtel MP, Jolles J. Education about dementia. Effectiveness of a public lecture. Tijdschr Gerontol Geriatr 2004;35:72–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mol MEM. Public education about memory and aging: Objective findings and subjective insights. Educ Gerontol 2006;32:843–58 [Google Scholar]

- 82.Moorhouse P. Screening for dementia in primary care. Can Rev Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2009:8–12 [Google Scholar]

- 83.Murphy CA, Solomon PR. Should we screen for Alzheimer’s disease? A review of the evidence for and against screening for Alzheimer’s disease in primary care practice. Geriatrics 2005; 60:26–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Von Korff M. Collaborative management of chronic illness. Ann Intern Med 1997;127:1097–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wagner EH. The role of patient care teams in chronic disease management. BMJ 2000;320:569–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pinquart M. Helping caregivers of persons with dementia: which interventions work and how large are their effects? Int Psychogeriatr 2006;18:577–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Roth DL. Changes in social support as mediators of the impact of a psychosocial intervention for spouse caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease. Psychol Aging 2005;20:634–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mittelman MS. A family intervention to delay nursing home placement of patients with alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1996;276:1725–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, et al. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10:45–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Atkins S, Lewin S, Smith H, et al. Conducting a meta-ethnography of qualitative literature: lessons learnt. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.