Abstract

Signal transduction cascades in living systems are often controlled via post-translational phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of proteins. These processes are catalyzed in vivo by kinase and phosphatase enzymes, which consequently play an important role in many disease states, including cancer and immune system disorders. Current techniques for studying the phosphoproteome (isotopic labeling, chromatographic techniques, and phosphospecific antibodies), although undoubtedly very powerful, have yet to provide a generic tool for phosphoproteomic analysis despite the widespread utility such a technique would have. The use of small molecule organic catalysts that can promote selective phosphate esterification could provide a useful alternative to current state-of-the-art techniques for use in, e.g., the labeling and pull-down of phosphorylated proteins. This report reviews current techniques used for phosphoproteomic analysis and the recent use of small molecule peptide-based catalysts in phosphorylation reactions, indicating possible future applications for this type of catalyst as synthetic alternatives to phosphospecific antibodies for phosphoproteome analysis.

Keywords: Kinase mimic, Kinase mimetic, Phosphorylation, Phosphoproteome, Phosphospecific antibody, Nucleophilic catalysis

Introduction

Proteomics is the study of the structure and function of proteins; phosphoproteomics is a subset of proteomics that involves the identification and characterization of proteins containing one or more mono-, di-, or tri-phosphate groups. The phosphorylation of proteins (catalyzed by the enzymatic action of protein kinases) is a reversible process involved in the regulation of cell signaling pathways [1, 2]. As such, phosphoproteomics provides an insight into which proteins and pathways are activated as the phosphorylation states of proteins are modulated and can therefore aid the identification of novel protein-based drug targets. However, despite the importance of phosphoproteomics in the elucidation of cellular signal transduction pathways involved in human health and disease, current methods of investigating the phosphoproteome still suffer from significant limitations.

The methods used in this burgeoning field have been recently and comprehensively reviewed from kinase identification [3], analytical chemistry [4], and chemical biology toolkit [5] perspectives and the main approaches are briefly overviewed below.

Current phosphoproteomic tools

One method of studying phosphoproteomics is the use of isotopically labeled ATP (using 32P) for the phosphorylation of proteins followed by isolation using SDS-PAGE or TLC [6]. It has also been shown that isotopic labeling of amino acid residues (using 13C/15 N) as well as the introduction of deuterated methyl groups (which can also increase the selectivity of antibodies, see below) can be used in the identification of novel proteins involved in cellular signaling pathways [7, 8]. Typically, isotopic labeling is used as a generic diagnostic tool for identifying tri- and diphosphate esters. These methods, however, suffer from low throughput and limitations associated with state-of-the-art bioinformatics tools and protein sequence database coverage [9].

Strong cation exchange (SCX) chromatography can also be used as an analytical tool for the study of phosphoproteomics [10]. Typically, resolution and characterization of complex mixtures of peptides (from phosphoproteomic samples) is carried out using reverse-phase HPLC coupled to an SCX column prior to analysis by mass spectrometry. While this methodology has proved useful in phosphoproteomics studies [11], there are several weaknesses to this technique. The presence of salt in the sample significantly reduces column efficiency. This is due to the displacement of the peptide/cation exchange sites by the salts which results in poor separation of peptides and more rapid elution of peptides from the column [10]. As a result, either desalting or a further purification step is required to achieve the desired purity of the peptide/protein for analysis. This acts to decrease the throughput of these systems and limits their utility when separating complex mixtures of peptides.

Protein/peptide purification and identification can also be achieved via immobilized-metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) [12–15]. This technique relies upon the formation of chelates between amino acid residues with ions, typically Cu(II), Ni(II), Zn(II), or Fe(III) ions which are covalently bound to a solid chromatographic support. These chelating ions can be considered as Lewis acids that can coordinate to electron-donating heteroatoms (O, N, and S) present on the amino acid residues of proteins with the remaining coordination sites of the metal ions being occupied by water. Although many amino acid residues (e.g., cysteine, aspartic acid, and glutamic acid) can participate in binding, the major contributing factor to protein separation in IMAC is the availability of histidyl residues which are often chemically attached as labels to aid purification and identification [16, 17].

IMAC is of particular use in industrial settings as it provides a cost-effective, rapid, and (moderately) efficient method to purify large quantities of proteins [16]. IMAC, however, is of less use when considering the identification and characterization of novel proteins. Prior to IMAC purification, proteins are often labeled with histidine tags to increase the affinity of the proteins for the metal-based solid support, however, attachment and removal of these tags can often be problematic [17, 18]. IMAC can also induce the degradation of amino acid side chains and cleavage of the protein backbone, reducing its utility as a purification technique. These side reactions result from metal-catalyzed oxidative processes which produce reactive radical species that can react with several amino acid residues (e.g., histidine, cysteine, and proline) and result in protein degradation [19–21]. This is particularly problematic for cysteine residues for which the free sulfhydryl moiety can be oxidized to the corresponding sulfenic, sulfinic, or sulfonic acid or converted to sulfoxide or sufone derivatives [21].

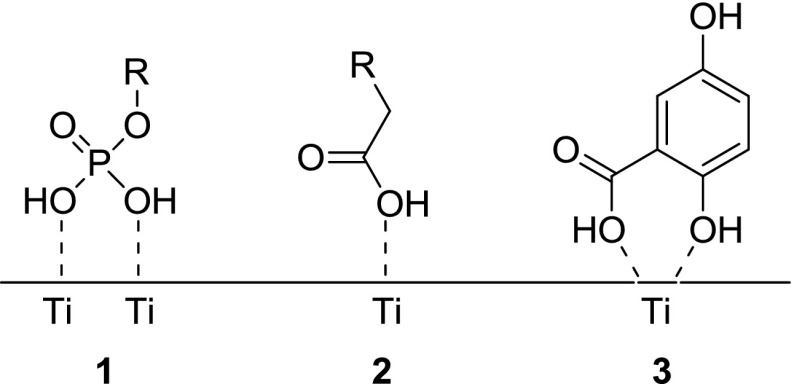

Another chromatographic strategy for protein purification/identification is TiO2 chromatography, which is of particular use when applied to phosphorylated proteins [22]. This method has been widely utilized in the phosphoproteomic field due to the unique ion-ligand exchange properties of TiO2 and its stability towards variations in both pH and temperature. The different binding modes of phosphorylated peptides compared to non-phosphorylated peptides facilitate the separation of phosphorylated peptides (Fig. 1) [23–25].

Fig. 1.

Different binding modes of phosphorylated peptides (1), non-phosphorylated peptides (2), and 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (3) to a TiO2 surface (taken from Engholm-Keller et al. 2011) [22, 24, 26]

Larsen et al. [26] were able increase the specificity of this technique with regards to phosphopeptides through the use of low pH buffers and the introduction of 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB) as an eluent additive. They suggested that the phosphoryl group in a phosphorylated peptide (1) binds to the TiO2 surface via a bridging bidentate interaction with the Ti surface whereas the carboxylic acid side chains of non-phosphorylated peptides (2) and also DHB (3) bind in a monodentate fashion; the DHB therefore competes for the carboxylic acid binding sites but not the phosphopeptide ones [22, 26]. This results in improved retention of phosphorylated peptides in comparison to non-phosphorylated peptides, aiding the purification/identification process. Larsen et al. [26] also proposed that the use of low pH conditions for peptide loading ensures that the carboxylic acid moiety of the peptide is protonated, i.e., rendered neutral and elutes from the column rapidly. By contrast, the phosphoryl group retains its negative charge (due to its lower pKa) and so is more efficiently retained on the column.

Several studies have been carried out to compare (phospho)peptide enrichment using IMAC and TiO2 chromatography [27–29]. Jensen et al. [27] and Cantin et al. [28] found TiO2 chromatography to be more efficient in the purification/identification of phosphopeptides, particularly with respect to elution of non-phosphorylated peptides from the column. However, Bodenmiller et al. [29] identified different phosphopeptides and different phosphorylation sites using each technique and found IMAC to have a higher specificity than TiO2 chromatography. These comparisons highlight the lack of a generally applicable and sufficiently specific chromatographic technique that can be utilized in the study of phosphoproteomics.

The most commonly used method of investigating the phosphoproteome is the use of phospho-specific antibodies [6, 9]. These antibodies are used in conjunction with other techniques such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), western blotting, and flow cytometry. Phosphospecific antibodies only recognize the phosphorylated form of a protein, thus aiding purification/identification of complex mixtures containing both phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated proteins [30–32]. Phosphospecific antibodies are often used along with non-phosphospecific (“pan”) antibodies, with the phosphospecific antibody aiding determination of the fraction of the protein that is phosphorylated and the pan antibody detecting the total amount of protein. This allows the identification of a specific protein using the pan antibody regardless of its phosphorylation state.

While anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies are most commonly used to investigate the phosphoproteome, the main drawback of this technique is the influence of the neighboring amino acid residues on the antibody efficiency. Anti-phosphoserine and threonine antibodies have also been developed but are not yet of high enough quality to be routinely used in proteomic research due to lack of selectivity, although the use of recombinant phosphoserine- and phosphothreonine-binding domains does present an opportunity to improve this [9, 10].

Prospects for the development of “chemical” phosphoproteomic tools

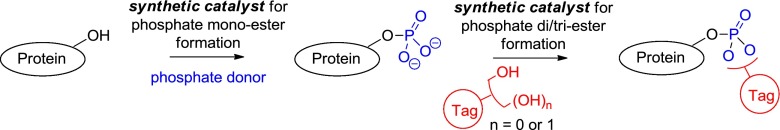

The above brief survey highlights the fact that while current procedures for protein identification and purification have proved very powerful, there is still a need for improved generally applicable tools for phosphoproteomic analysis. A novel approach to improving this situation would be through the development of synthetic catalysts to selectively “tag” phosphorylated peptides/proteins in complex mixtures to enable their identification (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Potential approach to the tagging of a phosphorylated protein

Much effort has been expended by the phosphopeptide synthesis community to develop robust methods for what is termed either “global phosphorylation” or “post-assembly” phosphorylation of preformed peptides containing non-side-chain protected serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues [33–36]. However, to the best of our knowledge, little focus has been put on developing protocols and catalysts that impart site-selectivity when presented with several potential reactive amino acid side chain hydroxyl groups in the manner of kinases. There is however increasing interest in the synthetic community directed at developing catalysts for the regio- and enantioselective phosphorylation of other classes of alcohol. This work and an assessment of the prospects of developing this area to encompass sequence selective phosphate tagging of peptides and eventually proteins, as envisioned in Fig. 2, is presented below.

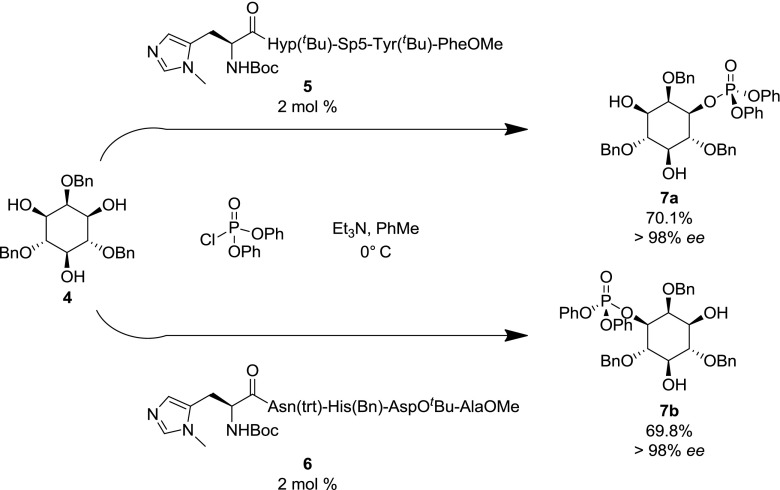

In 2001–2002, Miller et al. [37, 38] reported the use of peptide-based catalysts in the regio- and enantioselective total synthesis of d-myo-inositol-1/3-phosphate (7a/b), demonstrating the use of imidazole functionalized pentapeptides (e.g., 5/6) in catalytic asymmetric phosphate transfer (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Enantioselective synthesis of d-myo-inositol-1/3-phosphate (taken from Miller et al. 2001/2002) [37, 38]

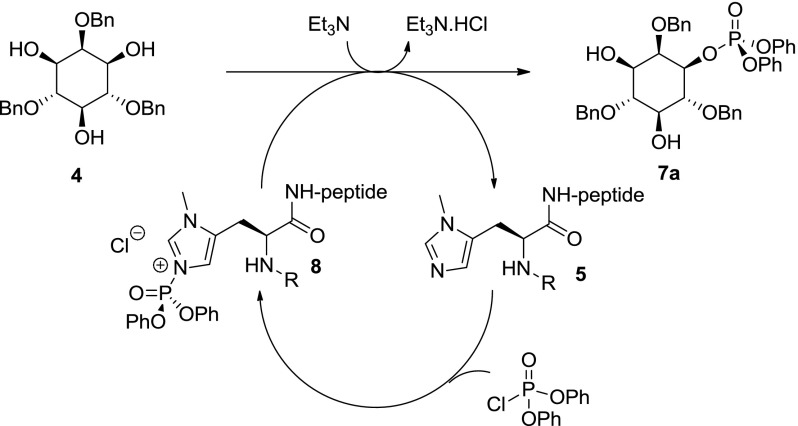

The proposed catalytic cycle proceeds via asymmetric nucleophilic P(V) phosphate transfer, achieved through the use of the π-methylhistidine (Pmh) residue, mimicking the action of histidine kinases [39] in the formation of a chiral high energy phospho-imidazolium ion 8 (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Proposed mechanism for asymmetric phosphorylation (adapted from Miller et al. 2001) [37]

Phosphate transfer occurs in the homochiral environment provided by the peptide scaffold to produce the desired product 7a with high regio- and enantioselectivity and regenerates the catalyst for the catalytic cycle.

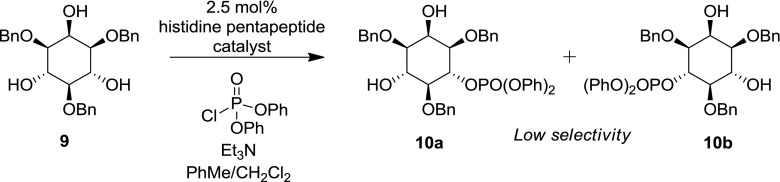

These histidine pentapeptide-based catalysts have also been used in the regio- and enantioselective synthesis of a series of eight unique inositol polyphosphates, highlighting the synthetic versatility of these reactions [40]. Despite the utility of these reactions, the use of P(V) has the limitation that the majority of P(V) chlorophosphate reagents contain phenyl substituents as these impart greater stability than alkyl substituents. This can often be problematic as the phenyl phosphate hydrolysis or hydrogenolysis conditions that are invariably applied after phosphorylation are often not compatible with sensitive substrates [37, 38, 40]. Histidine-based pentapeptide catalysts have also yet to achieve effective selectivity between the 4- and 6- positions of the inositol ring despite a catalyst screening of over 150 catalysts (Scheme 3) [41, 42].

Scheme 3.

Low selectivity of 4- (cf. 6-) phosphorylation of inositol (adapted from Sculimbrene 2004) [42]

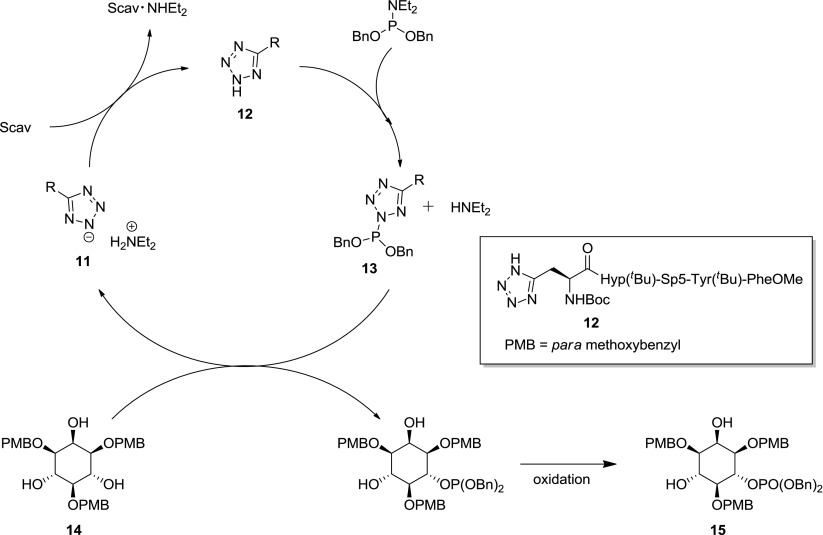

Interestingly however, Miller et al. [41] were able to significantly increase the selectivity of this phosphorylation for the 6- position through the use of tetrazole-based pentapeptide catalysts in conjunction with phosphoramidite [P(III)] phosphorus transfer reagents. They found that the optimal catalyst for this process contained the same peptide backbone as that used in the enantioselective synthesis of d-myo-inositol-1-phosphate (5, Scheme 1) [37] but with the N-methylimidazole moiety of the catalyst being replaced with a tetrazole group. Tetrazoles promote phosphoramidation via a different catalytic cycle to that by which N-methylimidazoles promote phosphorylation (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Proposed catalytic cycle for tetrazole-based catalysts (adapted from Miller et al. 2010) [41]

Phosphoramidite transfer from N,N-diethylphosphoramidite to the tetrazole moiety of the catalyst produces the activated P(III) species 13, nucleophilic attack of the 1,3,5-tri-O-myo inositol (14) then results in P(III) transfer to form PMB protected d-myo-inositol-6-phosphate 15 (70 %, 69.1 % ee). This catalytic cycle results in the formation of the free tetrazole acid 11 and diethylamine. These byproducts combine to form a dialkyl ammonium salt and so initial procedures required an excess of the tetrazole-based catalyst, i.e., the catalyst did not turn-over [43]. Importantly, Miller et al. [41] were able to overcome this problem (adopting methodology described by Hayakawa et al. [44]) through the introduction of 10-Å molecular sieves, which act as effective amine scavengers allowing the release of catalyst 12. These molecular sieves also act as a drying agent, helping to prevent hydrolysis of the activated phosphoramidite species 13. Tetrazole-based catalysis is potentially more versatile than the previously described N-methylimidazole based catalysis because P(III) reagents are inherently more reactive and accommodate greater structural diversity than their P(V) chlorophosphate-based analogues but do necessitate the use of a separate subsequent oxidation step to give the final phosphate product, which can be problematic in the presence of oxidatively labile functionality such as cysteine and methionine side chains of peptides and proteins [38, 40].

The regio- and enantioselective control that has now been gained in the phosphorylation of inositol substrates using small molecule peptide-based catalysts is of significant chemical and biological importance. Inositol and its phosphorylated analogues play a pivotal role in the IP3/DAG signal transduction cascade [45] and so these selective phosphorylation techniques offer the prospect of being employed to increase our understanding of these important processes.

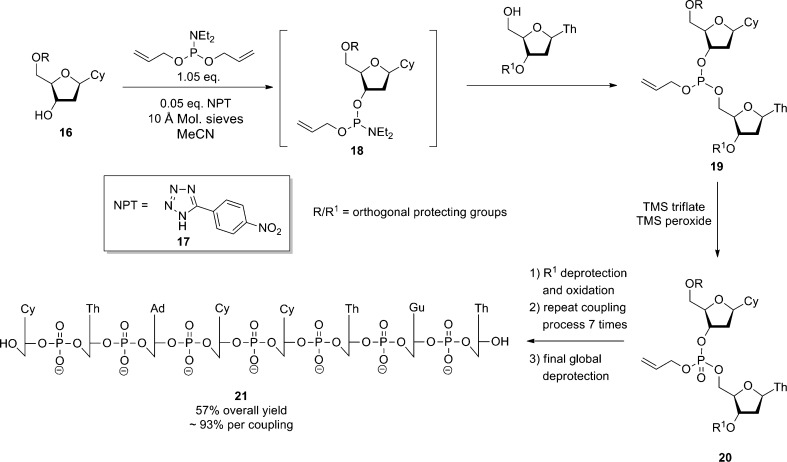

Structurally, more simple, achiral tetrazoles have also been described as efficient organic catalysts for the P(III)-based phosphorylation of other alcohol substrates and in particular have proven to be extremely useful in oligonucleotide synthesis [44, 46–48]. These reactions follow the same catalytic cycle as described above for the peptide-based tetrazole catalysts and so again require the use of a scavenger to recycle the catalytic tetrazole moiety. Using 5-(para-nitrophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (NPT, 17), Hayakawa et al. [44] were able to demonstrate the utility of this technique in the synthesis of oligonucleotides via P(III) transfer achieving an average yield of 93 % per coupling/deprotection cycle for an octomer (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5.

Hayakawa’s general strategy for oligonucleotide synthesis via tetrazole-based catalysis [44]

In the absence of the tetrazole-based catalyst no reaction occurs. This procedure is particularly useful for the synthesis of long oligonucleotides, for which the limiting factor in sequence length achievable is the yield per coupling/deprotection cycle. Methodology based on these procedures has now been adopted for use in automated DNA/RNA synthesizers which can achieve coupling efficiencies of >99 % [49].

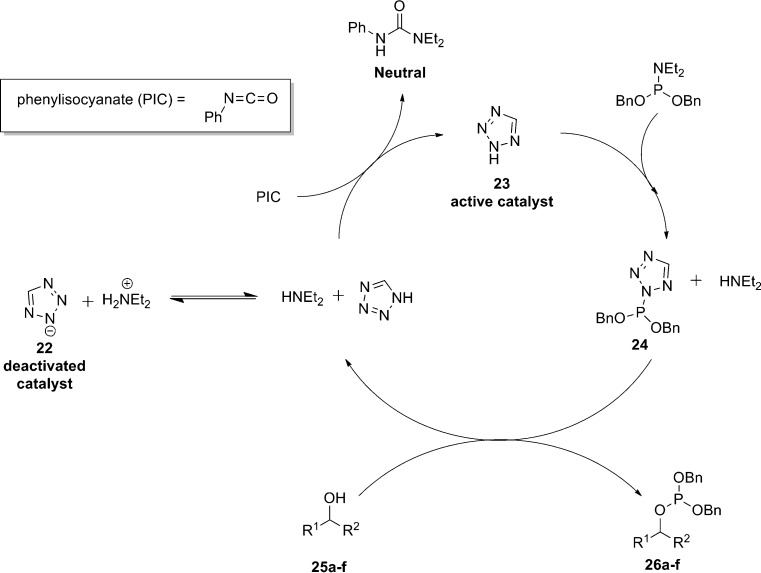

Tetrazole-based catalysis has also been utilized in the phosphitylation/phosphorylation of other hydroxyl containing organic compounds [46]. Limitations of this methodology are again due to catalyst deactivation resulting in the requirement for an excess of the tetrazole reagent (i.e., the catalyst does not turn-over) and low levels of conversion. Sculimbrene et al. [46] successfully developed a catalytic process through the incorporation of isocyanates or isothiocyanates into the reaction system. The isocyanates/isothiocyanates act as amine scavengers (in a functionally similar manner to the 10-Å molecular sieves used by Miller [41]) by acting as electrophiles which trap out the nucleophilic diethylamine as neutral (thio)ureas thereby allowing the protonated tetrazole catalyst to maintain the catalytic cycle (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6.

Sculimbrene’s phosphorylation of alcohols via tetrazole-based catalysis [46]

Screening of various isocyanates and isothiocyanates identified phenylisocyanate (PIC) as the optimal scavenger for the process. This method was successfully applied to the phosphitylation of primary and secondary alcohols with conversions being significantly increased in comparison to control reactions not containing the isocyanate, however, when applied to tertiary alcohols levels of conversion were still poor. This may be due to the fact that tertiary alcohols are significantly less reactive than their primary/secondary alcohol analogues and oxidation with H2O2 may also result in formation of the corresponding alkenes through elimination (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sculimbrene’s phosphorylation of alcohols via tetrazole-based catalysis [46]

aConversion determined by 1H NMR using internal standard

Sculimbrene et al. [50] have recently reported an alternative catalytic procedure for the phosphorylation of primary and secondary alcohols, utilizing titanium-based Lewis acids and pyrophosphates [P(V) reagents]. Use of tetrabenzylpyrophosphate (TBPP, 1.2 eq.) in conjunction with Ti(OtBu)4 (10 mol%) proved optimal for the reaction and importantly extended the substrate scope of these catalytic phosphorylation procedures to include protected amino acids residues (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sculimbrene’s phosphorylation of alcohols using Ti(OtBu)4 and pyrophosphates [50]

aFrom 1H NMR product decomposes during Si chromatography

This procedure incorporates the use of a base (in this case NiPr2Et) to provide efficient catalytic turnover by acting as an acid scavenger and allows the use of a P(V) phosphorylating agent, thus avoiding the formation of elimination products associated to the use of P(III) reagents followed by subsequent oxidation (Entry 6, Table 1). Sculimbrene et al. [50] again, however, describe the phosphorylation of tertiary alcohols using these conditions as being inefficient. This procedure provides marginally improved yields in comparison to the previously described use of tetrazole-based catalysts in conjunction with isocyanates (Table 1).

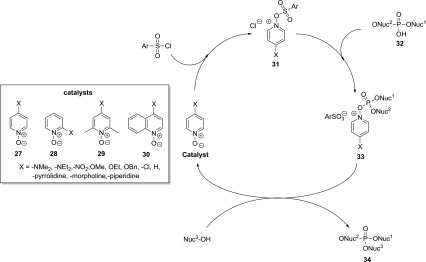

Other, structurally simple, achiral nucleophilic catalysts have also been employed to effect P(V)-based alcohol phosphorylation reactions and in particular have proven to be useful in oligonucleotide synthesis: e.g., N-methylimidazole and various pyridine N-oxides (Scheme 7) [51, 52].

Scheme 7.

Pyridine N-oxides in phosphotriester bond formation (adapted from Efimov et al. 1985) [51]

These catalysts are used in conjunction with condensing agents (e.g., aryl sulfonylchlorides) and have been reported to provide a faster and more efficient method of phosphotriester bond formation in comparison to tetrazole catalyzed oligonucleotide synthesis. Investigation of the relative reaction rates using electron-rich and electron-poor pyridine- and quinolone-N-oxides (27–30) revealed that the unsubstituted catalysts and those containing electron-withdrawing substituents had no rate accelerating effect while electron-donating substituents (particularly para substituted variants) resulted in significant rate enhancement. The 2,6-lutidine-based catalyst 29 and quinolone-based catalyst 30 were found not to accelerate the reaction rates. Effimov et al. [51] propose that this is due to steric hindrance inhibiting the nucleophilic attack of the catalyst on the aryl sulfonyl chloride. They also demonstrated that the para substituted pyridine N-oxides were more efficient than their ortho substituted analogues, this is again presumably a result of steric hindrance around the reactive O-center although the electronic effects of the substituents may also reduce catalyst performance. The optimal catalyst for phosphotriester formation was found to be para dimethylaminopyridine-N-oxide (4-DMAP-N-oxide) which was used to synthesize a 20-mer in 4 h and overall yield of 18 %, providing a rapid and efficient synthesis of oligonucleotides.

Conclusions

While current techniques for the study of the phosphoproteome including the use of isotopic labeling, various chromatographic techniques and phosphospecific antibodies have proved very powerful, there remain limitations to their usefulness particularly with respect to their specificity and generality. Consequently, it can be expected that there will be significant interest in new methods that can improve this situation. Towards this end, we have highlighted in this short review the role that small molecule organic and transition metal catalysts can play in mediating the selective phosphorylation of alcohols. Although this chemistry has not been systematically adapted to the task of transforming phospho monoesters into phospho di- and tri-esters, the basic bond-forming events involved in these reactions are essentially analogous to those in alcohol phosphorylation. Success in this setting would raise the prospect of catalyzed tagging of phosphorylated peptides and proteins (cf. Scheme 2, above). Of course, the methods currently available are unsuitable for this purpose in large part because they are typically designed to operate on relatively simple substrates under non-aqueous laboratory conditions. There is clearly a huge challenge associated with developing these types of reactions to allow successful, selective tagging on complex substrates such as proteins in biologically relevant milieu. However, we believe that the studies outlined above may lay the foundations for the development, in the not too distant future, of new methods for analysis of phosphated peptide fragments and proteins by means of small molecule catalyzed tagging. Notwithstanding the significant challenges particularly around selectivity and reactivity that will need to be overcome to achieve this goal, we expect progress in this direction to emerge soon and hope that this review will contribute towards accelerating that process.

References

- 1.Lim YP. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3163–3169. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsen JV, Blagoev B, Gnad F, Macek B, Kumar C, Mortensen P, Mann M. Cell. 2006;127:635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sopko R, Andrews BJ. Mol Biosyst. 2008;4:920–933. doi: 10.1039/b801724g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nilsson CL. Anal Chem. 2012;84:735–746. doi: 10.1021/ac202877y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martic S, Kraatz HB. Chem Sci. 2013;4:42–59. doi: 10.1039/c2sc20846f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson SA, Hunter T. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1093–1094. doi: 10.1038/nbt0904-1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ficarro SB, McCleland ML, Stukenberg PT, Burke DJ, Ross MM, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, White FM. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:301–305. doi: 10.1038/nbt0302-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brill LM, Salomon AR, Ficarro SB, Mukherji M, Stettler-Gill M, Peters EC. Anal Chem. 2004;76:2763–2772. doi: 10.1021/ac035352d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalume DE, Molina H, Pandey A. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:64–69. doi: 10.1016/S1367-5931(02)00009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blagoev B, Ong SE, Kratchmarova I, Mann M. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1139–1145. doi: 10.1038/nbt1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDonald WH, Ohi R, Miyamoto DT, Mitchison TJ, Yates JR. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2002;219:245–251. doi: 10.1016/S1387-3806(02)00563-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaberc-Porekar V, Menart VJ. Biochem Biophys Methods. 2001;49:335–360. doi: 10.1016/S0165-022X(01)00207-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porath J, Carlsson J, Olsson I, Belfrage G. Nature. 1975;258:598–599. doi: 10.1038/258598a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Porath J. Protein Expr Purif. 1992;3:263–281. doi: 10.1016/1046-5928(92)90001-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sulkowski E. Bioessays. 1989;10:170–175. doi: 10.1002/bies.950100508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arnold FH. Biotechnology. 1991;9:151–156. doi: 10.1038/nbt0291-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takacs BJ, Girard MF. J Immunol Methods. 1991;143:231–240. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90048-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gu J, Stephenson CG, Iadarola MJ. Biotechniques. 1994;17:257–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krishnamurthy R, Madurawe RD, Bush KD, Lumpkin JA. Biotechnol Prog. 1995;11:643–650. doi: 10.1021/bp00036a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rana TM. Adv Inorg Biochem. 1994;10:177–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Humphreys DP, Smith BJ, King LM, West SM, Reeks DG, Stephens PE. Protein Eng. 1999;12:179–184. doi: 10.1093/protein/12.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Engholm-Keller K, Larsen MR. J Proteomics. 2011;75:317–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuroda I, Shintani Y, Motokawa M, Abe S, Furuno M. Anal Sci. 2004;20:1313–1319. doi: 10.2116/analsci.20.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pinkse MW, Uitto PM, Hilhorst MJ, Ooms B, Heck AJ. Anal Chem. 2004;76:3935–3943. doi: 10.1021/ac0498617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dobson KD, McQuillan AJ. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2000;56:557–565. doi: 10.1016/S1386-1425(99)00154-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsen MR, Thingholm TE, Jensen ON, Roepstorff P, Jorgensen TJ. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:873–886. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T500007-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jensen SS, Larsen MR. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2007;21:3635–3645. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cantin GT, Shock TR, Park SK, Madhani HD, Yates JR., 3rd Anal Chem. 2007;79:4666–4673. doi: 10.1021/ac0618730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bodenmiller B, Mueller LN, Mueller M, Domon B, Aebersold R. Nat Methods. 2007;4:231–237. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Panicker RC, Chattopadhaya S, Yao SQ. Anal Chim Acta. 2006;556:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2005.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tichy A, Salovska B, Rehulka P, Klimentova J, Vavrova J, Stulik J, Hernychova L. J Proteomics. 2011;74:2786–2797. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dahan S, Chevet E, Liu JF, Dominguez M. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2007;1:922–933. doi: 10.1002/prca.200700153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McMurray JS, Coleman DR, Wang W, Campbell ML. Biomolecules. 2001;60:3–31. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2001)60:1<3::AID-BIP1001>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perich JW (2004) In Synthesis of Peptides and Peptidomimetics, Houben-Weyl Methods in Organic Chemistry, Vol. E22b. Thieme, Stuttgart, p 375–424

- 35.Attard T, O’Brien-Simpson N, Reynolds E. Int J Pept Res Ther. 2007;13:447–468. doi: 10.1007/s10989-007-9107-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toth GK, Kele Z, Varadi G. Curr Org Chem. 2007;11:409–426. doi: 10.2174/138527207780059295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sculimbrene BR, Miller SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:10125–10126. doi: 10.1021/ja016779+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sculimbrene BR, Morgan AJ, Miller SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:11653–11656. doi: 10.1021/ja027402m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, Hunter T, Sudarsanam S. Science. 2002;298:1912–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1075762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morgan AJ, Komiya S, Xu Y, Miller SJ. J Org Chem. 2006;71:6923–6931. doi: 10.1021/jo0610816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jordan PA, Kayser-Bricker KJ, Miller SJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:20620–20624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001111107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sculimbrene BR (2004) PhD Thesis (Boston College, Boston)

- 43.Dahl BH, Nielsen J, Dahl O. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 1987;6:457–460. doi: 10.1080/07328318708056255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hayakawa Y, Kataoka M. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:11758–11762. doi: 10.1021/ja970685b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hunter T. Cell. 2000;100:113–127. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81688-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brady PB, Morris EM, Fenton OS, Sculimbrene BR. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:975–978. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.12.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beaucage SL, Iyer RP. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:2223–2311. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)88752-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beaucage SL, Iyer RP. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:1925–1963. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)86295-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zlatev I, Manoharan M, Vasseur JJ, Morvan F (2001) In Curr Prot Nucl Acid Chem; John Wiley & Sons, Inc

- 50.Fenton OS, Allen EE, Pedretty KP, Till SD, Todaro JE, Sculimbrene BR. Tetrahedron. 2012;68:9023–9028. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2012.08.070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Efimov VA, Chakhmakhcheva OG, Ovchinnikov Yu A. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:3651–3666. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.10.3651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Efimov VA, Buryakova AA, Dubey IY, Polushin NN, Chakhmakhcheva OG, Ovchinnikov Yu A. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:6525–6540. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.16.6525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]