Abstract

The investigation of therapeutic protein drug–drug interactions has proven to be challenging. In May 2012, a roundtable was held at the American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists National Biotechnology Conference to discuss the challenges of preclinical assessment and in vitro to in vivo extrapolation of these interactions. Several weeks later, a 2-day workshop co-sponsored by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the International Consortium for Innovation and Quality in Pharmaceutical Development was held to facilitate better understanding of the current science, investigative approaches and knowledge gaps in this field. Both meetings focused primarily on drug interactions involving therapeutic proteins that are pro-inflammatory cytokines or cytokine modulators. In this meeting synopsis, we provide highlights from both meetings and summarize observations and recommendations that were developed to reflect the current state of the art thinking, including a four-step risk assessment that could be used to determine the need (or not) for a dedicated clinical pharmacokinetic interaction study.

Key words: cytochrome P450s, drug–drug interactions, pro-inflammatory cytokines, small molecule, therapeutic protein

INTRODUCTION

The increase in the clinical use of therapeutic proteins (TPs) has drawn attention to the potential for drug–drug interactions (DDIs) between TPs and small molecule (SM) drugs or TP-DDIs. With respect to pharmacokinetic interaction, systemic pro-inflammatory cytokines released during infection, inflammation, or cancer are known to suppress key SM drug-metabolizing enzymes, such as cytochrome P450s (CYPs). This results in decreased clearance of SM substrates of the affected CYPs (1). Recently, treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients with tocilizumab, a monoclonal anti-IL-6 receptor antibody was shown to desuppress (or normalize) CYP3A4-mediated clearance of simvastatin by just over 2-fold (2).

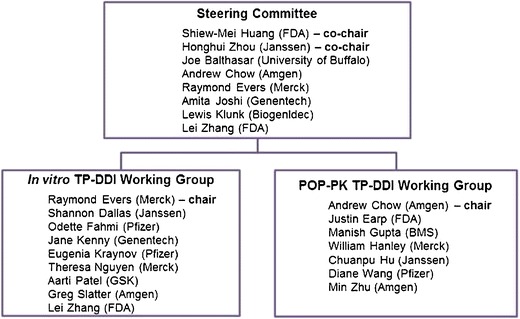

Regulatory interest in TP-DDIs has increased in recent years, and a variety of reviews and workshops have identified some of the knowledge gaps (3–5). On 25 May 2012, a 1.5-h roundtable entitled “Challenges in using in vitro and preclinical in vivo systems for assessing TP-DDI” was held at the National Biotechnology Conference (NBC American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists (AAPS)) in San Diego, CA. In vitro, in vivo, and in vitro to in vivo extrapolation aspects were considered and emerging data and ideas were presented. Several weeks later, on 4–5 June 2012, a workshop, co-sponsored by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the International Consortium for Innovation and Quality in Pharmaceutical Development (IQ Consortium), was held in Silver Spring, MD to facilitate understanding of new investigative approaches and identify the remaining challenges in TP-DDI evaluation. During the workshop, invited experts from academia, regulatory agencies, TP-DDI Working Groups (on In Vitro and Population Pharmacokinetic (PK) assessment, respectively) Fig. 1, and member companies of the IQ Consortium shared recent experience, discussed challenges, and debated best practices for preclinical and clinical approaches to the prediction and clinical assessment of TP-DDI (with changes in PK as surrogate for interaction). The main focus was on TPs that are pro-inflammatory cytokines or cytokine modulators. Here, we summarize the key discussion points from both meetings and the recommendations from the workshop. Two white papers from the IQ’s TP-DDI Working Groups are currently in preparation.

Fig. 1.

History, objectives, and members of the TP-DDI Working Groups. In 2009, experts from the FDA, academia, and industry formed a steering committee to develop a general framework for in vitro, in vivo, and clinical risk-based approaches to TP-DDI assessment during drug development. The steering committee initially focused its effort on the assessment of pharmacokinetics and metabolism-based DDIs involving monoclonal antibodies, fusion proteins, and cytokines. TPs’ potential both as perpetrators to drugs that are metabolized via CYP enzymes and as victims would be assessed. The steering committee then established two working groups with one focused on in vitro methodology to assess TP-DDIs and the in vitro–in vivo correlation, and the other focused on the development of a general practice for the appropriate model-based TP-DDI evaluation, such as population PK-based analysis. The two working groups are comprised of scientists from the IQ Consortium and the former PhRMA technical groups, academia, as well as the FDA

AAPS NBC ROUNDTABLE: CHALLENGES IN USING IN VITRO AND IN VIVO SYSTEMS FOR ASSESSING TP-DDI

Three presentations on the current status of TP-DDI were followed by a panel discussion with the audience. Key questions included whether in vitro data could be “actionable” with respect to defining the need for a clinical DDI study, whether the acute phase response protein C-reactive protein (CRP) could be used as a potential biomarker for CYP modulation in inflammatory disease, and whether TP-DDI could be quantitatively predicted from preclinical data and what clinical DDI study designs were appropriate.

In Vitro Challenges

The roundtable highlighted a key challenge with current in vitro systems, namely whether such data are actionable. For example, in isolated human hepatocytes, although the suppression of CYP3A4 and CYP1A2 by IL-6 is well established, recent publications have revealed some key limitations in the predictive value of the model (6–8). The human hepatocyte model is now being applied to new cytokine targets such as the pro-inflammatory cytokine, IL-23. New data were presented showing that IL-23 in human hepatocyte culture did not suppress CYPs. This was proposed to be due to the lack of IL-23 receptor expression on hepatocytes. Since IL-23 might have an indirect effect on CYPs mediated by immune modulatory cells, a long-term co-culture system with human hepatocytes and Kupffer cells was established. In this system, a positive control, the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β, caused a Kupffer cell and concentration-dependent secretion of IL-6 and IFN-γ, but no such effect was observed when cells were incubated with IL-23. A strong effect of IL-1β on the activity of CYP3A4 was observed and this effect was dependent on the presence of Kupffer cells. As expected, IL-23 had no effect on CYP3A4 in vitro. These data illustrate the dichotomy between direct effects of a single cytokine and potential indirect effects mediated by stimulation of the release of additional cytokines. This study showed that a lack of relevant pro-inflammatory cytokine receptors on hepatocytes or Kupffer cells may preclude a direct effect of the cytokine on CYP activity. These IL-23 in vitro data were recently corroborated (9). The presence or absence of relevant cytokine receptors on hepatocytes or Kupffer cells may therefore be a valuable piece of biological information that can be used along with knowledge of the disease indication to discern a path forward for the investigation of TP-DDI.

In Vivo Challenges

While many preclinical CYP suppression studies have used lipopolysaccharide (LPS) endotoxin to induce an acute phase response in vivo (10), there are few studies on the ablation of CYP suppression by rodent-specific anti-cytokine antibodies in rodent models of inflammatory disease (11–13). One common feature which links preclinical in vivo LPS-mediated CYP suppression studies and clinical disease treatment effects on CYP3A is that the upper limit of CYP activity changes is generally about 2–3-fold. As such, the first challenge for in vivo assessment is that the magnitude of the effect is smaller than conventional CYP induction and inhibition. At this level, TP-DDIs are only a concern for victim drugs with a narrow therapeutic index.

A hypothesis was advanced that inflammatory disease treatment effects on an inflammation biomarker, CRP, may help predict the likelihood of a measurable clinical effect of a disease treatment on CYP-mediated drug clearance (5). In the tocilizumab–simvastatin clinical drug–disease interaction study (2), CRP levels in RA patients dropped from relatively high values (40–50 mg/L) to near the upper limit of normal value of 3 mg/L. IL-6 is an important cytokine in the human liver (14) and one of its primary effects is the secretion of CRP by hepatocytes (15). Supplementary genomic data (5,16) and some clinical studies (2,17–20) have all revealed a relationship between CYP3A and CRP or IL-6. Data were presented where CRP changes in 19 selected inflammatory disease clinical studies were compared to CRP changes observed in the tocilizumab–simvastatin study in patients with RA. Key conclusions from the small number of studies examined were that tocilizumab in RA patients markedly reduced relatively high CRP levels to near baseline and that some indications, like psoriasis, had relatively smaller elevations of CRP in the untreated population.

One premise regarding the CYP effects that occur due to treatment of inflammatory disease is that the change will not exceed the difference between the expression of CYP in the inflammatory disease population and normal individuals. It is a challenge therefore that large-scale clinical studies or meta-analyses that benchmark CYP suppression in a well-characterized inflammatory disease population are not available. As such, the last challenge for in vivo assessment is that drug–disease interactions must be investigated in the disease population, and there are few, adequate, and well-controlled clinical examples of TP-DDI to enable in vitro–in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) assessments. This challenge, coupled with the limitations in existing preclinical models (7,8), suggests that an alternative methodology to assess TP-DDI risk is needed. If hepatic responses to inflammatory disease revolve primarily around IL-6, then CYP effects might be predictable based on trial population averages of pre- and post-treatment CRP levels. Consequently, it was proposed that the risk of CYP-related TP-DDI may eventually be ruled out for certain disease indications like psoriasis, where the hepatic CRP response to systemic manifestations of psoriatic inflammation may not be as large (8). Clinical investigation may be indicated when mean or median CRP changes are above some yet to-be-determined threshold. Additional clinical studies on diverse inflammatory cytokine targets and in diverse indications are needed to discern whether CRP changes and disease indication are valid predictors of clinically measurable drug–disease interactions.

IVIVE Challenges

The limited amount of data on clinically significant TP-DDI is likely due to the modest magnitude of interactions which makes detailed concordance analysis of in vitro and in vivo findings a challenge. Adding to this challenge, current in vitro systems may not be sophisticated enough to capture the complex nature of TP-DDI as clinically observed TP-DDIs may involve indirect effects of multiple cytokines, are pharmacodynamics-based, may involve complex signaling among different types of cells and be dependent on the health or disease status of the patients. The indirect, complex, and pharmacodynamics-based TP-DDIs are illustrated by the following examples.

Methotrexate, an immunomodulator, decreases the clearance of several anti-TNFα TPs including infliximab (21), adalimumab (22), golimumab (23), and certolizumab pegol (24), presumably through the suppression of immunogenicity. However, methotrexate does not affect the systemic exposure of the anti-TNFα fusion protein etanercept (25). The mechanism underlying these different effects is poorly understood.

In another example, both muromonab-CD3 and basiliximab, when co-administered with cyclosporine, increase its concentration in blood (26,27), but they cause this TP-DDI through different mechanisms. Muromonab-CD3 can induce a limited “cytokine storm” after the first injection which releases cytokines such as TNF-α, interferon, and IL-2 (28). It is known that IL-2 can suppress CYP3A under in vitro (29–31), ex vivo (32), and in vivo settings (33), which may explain the muromonab-CD3–cyclosporine interaction. Basiliximab, in contrast, binds to the IL-2 receptor (IL-2R) on activated T cells. It has been hypothesized that basiliximab displaces IL-2 from the IL-2R, and that displaced IL-2 may act on CYP3A (27).

Another significant challenge for IVIVE is that in vivo studies are often confounded by a myriad of factors, such as disease status, immunogenicity, concomitant medications, and target-mediated drug disposition. Currently available in vitro systems, unfortunately, cannot recapitulate these conditions, although attempts have been made to retrospectively construct IVIVE for IL-6 (34), which is currently the only inflammatory cytokine that has both in vitro and clinical data.

THE FDA-IQ CONSORTIUM CO-SPONSORED TP-DDI WORKSHOP

Over 70 representatives from industry and regulatory agencies and invited speakers from academia attended the 2-day workshop. Industry, academic, and regulatory perspectives were shared through 14 presentations, 2 panel discussions, and an audience poll. Two working groups comprised of members from IQ Consortium, regulatory and academia, the “In Vitro TP-DDI” Working Group and the “POP-PK TP-DDI” Working Group (see Fig. 1), presented their collective output. White papers summarizing Working Groups’ perspectives and specific details of the meeting, including a summary of the polling results, are currently in preparation.

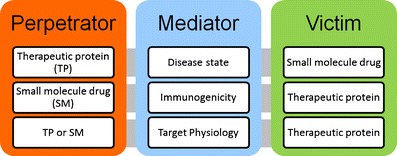

Observations on Clinical TP-DDI

Understanding the clearance mechanism(s) for an investigational SM or TP is the basis for assessing potential for PK-oriented TP-DDIs. Clearance mechanisms for SMs and TPs are quite different. For SMs, clearance mechanisms often involve biliary and renal excretion as well as hepatic metabolism. For TPs, clearance mechanisms are often specific target-mediated, Fc receptor-mediated (for monoclonal antibodies or antibody fragments/fusion proteins), or nonspecific receptor-mediated endocytosis, immunogenicity-mediated clearance, and renal metabolism. Three elements can be considered in assessing TP-DDIs: a perpetrator, a victim, and a mediator (disease state, immunogenicity, or target physiology) (Fig. 2).

A TP (as the perpetrator) can interact with a SM (as the victim) by influencing the disease state (as the mediator). Pro-inflammatory cytokines released under disease conditions such as infection, inflammation, or cancer have been shown to decrease the expression of CYPs. TPs which alter inflammatory/immune/disease processes thus may have indirect pharmacokinetic interactions with SMs which are substrates of the affected CYPs, such as the tocilizumab–simvastatin interaction in RA patients (2).

A SM (as the perpetrator) can have indirect PK interactions with a TP (as the victim) via alteration of immunogenicity. For example, methotrexate can significantly decrease the clearance of infliximab, presumably due to the suppression of immunogenicity of infliximab by methotrexate, as subjects who receive infliximab treatment and develop immunogenicity usually have accelerated infliximab clearance (21), although a role of the Fcγ receptor in this interaction cannot be excluded.

A SM or TP (as the perpetrator) may interact with a TP (as the victim) by influencing its distribution via alteration of target physiology or target-mediated disposition. For example, tumor uptake of trastuzumab decreases with concomitant administration of an anti-VEGF antibody. Mechanistic studies suggested that the observed changes in tumor uptake were attributable to the reduction in both tumor blood flow and vascular permeability to macromolecules (35).

Fig. 2.

The trilogy of commonly observed indirect TP-DDIs. (1) TP (as the perpetrator) can interact with a SM (as the victim) in the disease state. (2) SM (as the perpetrator) can have indirect PK interactions with a TP (as the victim) via alteration of immunogenicity. (3) SM or TP (as the perpetrator) may interact with a TP (as the victim) at the PK level via alteration of target physiology or target-mediated disposition

Mechanisms for many TP-DDIs are still poorly or partially understood, and these mechanisms are likely to be more complex than the few listed above. An in-depth understanding of the clearance pathways involved in the disposition of victim drugs and the pharmacological effects of perpetrator drugs in the specific disease setting is needed to develop a meaningful TP-DDI assessment plan.

Population PK Modeling Approach for Assessing TP-DDI

Since most of the observed TP-DDIs are discerned under specific disease-mediated conditions, clinical TP-DDI studies are usually conducted in patients rather than healthy subjects. Population PK modeling (36) provides a feasible approach for TP-DDI assessment as it allows less intensive sampling, incorporation of TP-DDI assessment in larger phase 2 and 3 trials involving relevant patient populations, integration of data generated from multiple studies during different development phases, and evaluation of the effect of combined “perpetrators” on a TP and potentially the effect of a TP on co-medications when the analysis is pre-specified and concentrations of the co-medications are assayed. Historically, the population PK approach has most often been used in an exploratory manner and it serves as a powerful tool for screening purposes, ruling out TP-DDIs or identifying unexpected interactions for further characterization in dedicated TP-DDI studies (37). Over the last decade, experience has accumulated and the methodology is maturing. The current population PK approach can also be used as a confirmatory tool in assessing TP-DDIs (38,39).

At the workshop, clinical trial simulation results and regulatory examples where population PK was used to develop DDI labels were presented that demonstrate the advantages and utility of pre-specified population PK as a tool for assessing TP-DDIs. The following observations emerged from the discussion:

The population PK approach is an effective way to detect significant unexpected DDIs with SMs as perpetrators and confirm expected DDIs as the effect of concomitant medications can be incorporated as a covariate in the population PK model for assessing TP-DDIs involving a number of SMs (40,41).

The population PK approach may provide valuable information on perpetrator effects of a TP on a SM or vice versa. When a priori information is available, the trial design can be pre-specified and PK data of both SM and TP drugs can be collected. In such cases, the effects may be assessed for the TP either as a victim or as a perpetrator. When post hoc analyses are conducted where the PK of the concomitant medications is unavailable, it is not possible to determine the effect on the SM drug.

It was noted that the current population PK-based modeling methodology (38,39), when used properly, can generate reliable results for confirmation purposes. The importance of prospective planning, proper study design, and the use of pre-specified models in the analysis was emphasized. Additionally, a priori dialogue between FDA and the sponsor on the feasibility of using this approach is usually helpful. Further, the DDI assessment should be based on the 90% confidence interval of the DDI effect on the parameter of interest, not on its statistical significance in the model.

The POP-PK TP-DDI Working Group (Box 1) evaluated the performance of the population PK approach in TP-DDI assessments by conducting simulation studies. The results showed that, with adequate study design and analysis, the population PK approach can achieve the desired power for TP-DDI assessment using concomitant medications as covariates of clearance (CL). For a balanced study design with equal number of subjects in the study drug alone arm and combination arm, the sample size required for the population PK approach is similar to that for the noncompartmental analysis approach for the model drug tested. Increasing the number of subjects in one arm, however, can significantly increase the power of the DDI assessment. Under the simulated scenarios (at least 20% difference in CL), the chance of falsely concluding lack of DDI (type 1 error rate) is well controlled and the magnitudes of DDI are estimated with no bias. As the next step, the working group plans to evaluate how dosing error, PK sampling time error, and model misspecification affect the accuracy and precision of the DDI results. The working group also plans to test the power of TP-DDI assessment when PK parameters other than clearance are affected.

Case studies were presented where the population PK approach has been used for regulatory decision making in DDI assessment. In some instances, the approach was utilized for dose adjustments for labeling purpose, and in another situation, it was used to alleviate the need for separate dedicated DDI studies. Of note, in many cases, however, DDI findings identified by the exploratory population PK approach did not end up in the labeling due to poor data quality or study design.

The challenges of using the population PK approach for DDI evaluation were also discussed at the workshop. A major challenge is that, unless properly designed and pre-specified in protocol design, the population PK approach applied to date usually assesses one-way interactions only (i.e., the effect of concomitant medications on PK of the investigational drug). This is because usually only the concentrations of the investigational drug are measured in the phase 2 and 3 trials. Unreliable or misleading drug interaction results may be concluded if the study is poorly designed and substantial amount of dosing/sampling times are missing or inaccurately recorded. Other confounding factors such as disease progression or other sources of variability (e.g., age/gender/race) that may affect the PK of the compound (investigational drug or concomitant medications) may also not be properly addressed.

In Vitro TP-DDI

The In Vitro TP-DDI Working Group (Box 1) presented the results of an initiative related to lab-to-lab variability and standard practices for industrial in vitro evaluation of cytokine-related CYP-mediated TP-DDIs.

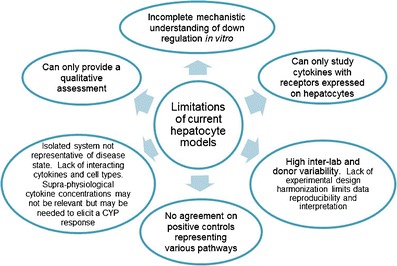

In addition to the challenges highlighted at the AAPS NBC Roundtable (i.e., whether in vitro data are actionable), the application of primary hepatocytes as a tool to predict DDIs between SMs and TPs currently has significant limitations (Fig. 3). These limitations are different from those faced with SM DDIs, for which in vitro systems are generally well qualified (37,42,43). For example, a fundamental concern regarding in vitro assessment of TP-DDI is that hepatocyte culture is an oversimplified system, which cannot reproduce the complex biology of in vivo disease states. Another unique aspect of TP-DDI is the potential heterogeneity and/or instability of the necessary biological reagents, and it is important to understand the biochemical characteristics of large molecule reagents for proper interpretation of results (7).

Fig. 3.

Limitations of applying current isolated hepatocyte models to the assessment of cytokine effects on CYP enzymes

The In Vitro TP-DDI Working Group (Box 1) pooled internal cross-company data on the suppression of CYP3A4 by IL-6. Although the suppression of CYP3A4 mRNA expression and activity by IL-6 was consistently observed, a large inter-hepatocyte donor and inter-lab variability in IC50 values existed. This variability is likely due to both intrinsic inter-donor differences and the lack of a harmonized experimental design. Additionally, IC50 values increased substantially with incubation time, possibly due to the down-regulation of the IL-6 receptor in hepatocytes over the course of the experiment (7). The working group members shared and compared experimental methodologies and established a harmonized protocol with agreed-upon culture conditions for some critical parameters and controls. With this harmonized protocol, the IC50 values for the suppression of CYP3A4 mRNA by IL-6 were similar across four of the six companies, with key media components influencing the outcome. The details of this work and a recommendation from the working group for in vitro conditions will be presented in a forthcoming white paper. The consensus view from the workshop was that the hepatocyte culture, as employed at the moment, may not be an appropriate system for quantitative TP-DDI prediction. Nevertheless, in vitro approaches are still useful for mechanistic studies, and continued investment in the development of more predictive in vitro platforms (e.g., co-culture models) may be of value.

Regulatory Perspective on TP-DDI Assessment

Regulatory agencies including the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the FDA have included recommendations on TP-DDI assessment during drug development in their guidances. The EMA guideline published in July 2007 entitled “Guideline on the Clinical Investigation of the Pharmacokinetics of Therapeutic Proteins” describes concerns about immunomodulators such as cytokines that have shown a potential for inhibition or induction of CYP enzymes thereby altering the metabolism of SM substrates of these enzymes. The guideline suggests that the need for in vitro and/or in vivo studies should be considered on a case-by-case basis (44). The 2012 FDA draft guidance on DDI (37) expands recommendation on TP-DDI assessment from its 2006 draft. This new draft guidance reflects FDA’s current thinking in evaluation of TP-DDI. The thought process for TP-DDI studies and the types of studies that may need to be conducted are illustrated in Fig. 7 of the new draft guidance (37). General considerations include:

If an investigational TP is a cytokine or cytokine modulator that has known effects on CYP enzymes or transporters, studies should be conducted to determine the magnitude of the TP’s effects on drugs that are substrates of the affected CYP enzymes or transporters (4).

If a TP will be used with other drug products (SM or TP) as a combination therapy, studies should evaluate the effect of each product on the other.

If there are known mechanisms for interactions or prior experience suggests potential PK or PD interactions, appropriate evaluations for possible interactions should be conducted. Some interactions between drugs and TPs are based on mechanisms other than CYP enzyme or transporter modulation.

In vitro or animal studies have limited value in the qualitative and quantitative projection of clinical interactions because translation of in vitro to in vivo and animal to human results to date has been inconsistent, necessitating clinical drug interaction studies.

The FDA received comments from 27 individual companies, associations, and other interested parties on the new draft DDI Guidance during the public commentary period. Comments on the TP-DDI session included whether “pro-inflammatory cytokines” instead of “cytokines” should be the focus of the TP-DDI assessment. Based on the comments that FDA received, there appeared to be different opinions regarding the utility of in vitro models in predicting TP-DDIs. For example, some stated that in vitro or preclinical in vivo data could be useful on a case-by-case basis and studies performed in an appropriate in vitro model along with scientific justification can be used to guide decision for clinical DDI study; others proposed to remove the option of conducting in vitro studies to assess the effect of TP on a SM. Case studies and discussions from the AAPS NBC Roundtable and the FDA/IQ Consortium Workshop strongly suggest that existing in vitro and animal models have limited value in the prediction of clinical TP-DDIs. However, in vitro or animal models may be useful for mechanistic evaluation and scientific exploration of TP-DDI and are encouraged to build our knowledge base. The interpretation of Fig. 7 in the draft guidance was also discussed, and it was recommended that the “in vitro study” box in Fig. 7 of the guidance be removed in light of discussions on in vitro data limitations. Guidance comments were discussed at the workshop and will be considered by the FDA during the guidance revision.

CONCLUSION

These conference highlights show how the scientific community has responded to address gaps previously identified in the field of TP-DDI (3). The following observations and recommendations were developed to summarize the current state of the art thinking.

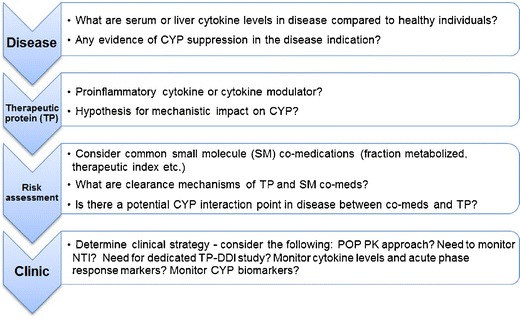

Evaluation of TP-DDI requires scientific diligence and is currently best done in clinical studies. The need for dedicated TP-DDI studies could be discerned by an assessment that involves four steps. First, consider the disease indication and biology, then the TP class of interest, followed by an analysis of risk related to concomitant medications, clearance mechanisms, and patient factors. Finally, these factors drive the clinical strategy that is devised (Fig. 4). This way, a thorough understanding of relevant cytokines and their impact on CYPs in the disease setting, along with consideration of whether a mechanism exists for a novel TP to influence pro-inflammatory cytokines, can be used to determine whether a clinical study is necessary. When there is insufficient information for risk assessment, potential interactions could be explored in phase 2 studies using population PK approaches or relevant biomarkers.

Preclinical quantitative assessment of TP-DDI, either in vitro or in vivo, is not recommended at this time, but may be useful for mechanistic evaluation. Investment in exploration of TP-DDI mechanisms and new in vitro tools is encouraged.

A population PK approach may provide invaluable information such as confirmatory results on perpetrator effects of other TP or SM on the TP being studied if appropriate planning is performed in advance.

Future work on treatment-induced changes in levels of acute phase biomarkers and/or endogenous CYP substrates may help define the potential for clinically significant effects on CYP substrates.

Fig. 4.

Suggested four-step approach to assess TP-DDI risk for cytokine or cytokine modulator and effects on CYP enzymes

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the TP-DDI Steering Committee (Fig. 1) and the in vitro TP-DDI and POP-PK TP-DDI Working Groups for their scientific contributions and valuable discussions. We also thank Dan Lu and Amita Joshi for concept discussions around Fig. 4 and Shannon Dallas, Manish Gupta, Amita Joshi, Eugenia Kraynov, and Min Zhu for critical review of this manuscript. Additionally, we acknowledge the contribution of the presenters and moderators of both the AAPS NBC meeting (Raymond Evers, Amita Joshi, Jane Kenny, Greg Slatter, Lei Zhang, and Honghui Zhou) and the workshop (Andrew Chow, Leslie Dickmann, Justin Earp, Raymond Evers, Eva Gill Berglund, Manish Gupta, Chuanpu Hu, Graham Jang, Jane Kenny, Eugenia Kraynov, Bernd Meibohm, Edward T. Morgan, Christophe Schmitt, Greg Slatter, Diane Wang, Lei Zhang, and Honghui Zhou). The roundtable was sponsored by the AAPS. The workshop was co-sponsored by the U.S. FDA and the International Consortium for Innovation and Quality in Pharmaceutical Development (www.iqconsortium.org), a not-for-profit organization of pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies with a mission of advancing science-based and scientifically driven standards and regulations for pharmaceutical and biotechnology products worldwide.

Disclaimer

The manuscript reflects the views of the authors and should not be construed to represent FDA, IQ Consortium, or individual company views or policies.

Conflict of interest

Andrew Chow and Greg Slatter are employees and own stock of Amgen Inc. Jane Kenny is an employee of Genentech, Inc., a member of the Roche Group, and may have an equity interest in Roche. Diane Wang is an employee and owns stock of Pfizer. Honghui Zhou is an employee and owns stock of Johnson & Johnson. Justin Earp, Raymond Evers, Maggie Liu, and Lei Zhang have no conflict of interest to report.

References

- 1.Morgan ET. Impact of infectious and inflammatory disease on cytochrome P450-mediated drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;85(4):434–8. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmitt C, Kuhn B, Zhang X, Kivitz AJ, Grange S. Disease-drug-drug interaction involving tocilizumab and simvastatin in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89(5):735–40. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Girish S, Martin SW, Peterson MC, Zhang LK, Zhao H, Balthasar J, et al. AAPS workshop report: strategies to address therapeutic protein-drug interactions during clinical development. AAPS J. 2011;13(3):405–16. doi: 10.1208/s12248-011-9285-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang SM, Zhao H, Lee JI, Reynolds K, Zhang L, Temple R, et al. Therapeutic protein-drug interactions and implications for drug development. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87(4):497–503. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slatter JG, Wienkers LC, Dickmann LJ. Drug interactions of cytokines and anticytokine therapeutic proteins. In: Zhou H, Meibohm B, editor. Drug interactions of therapeutic proteins: Wiley; 2013. chapter 13 p. 215–238.

- 6.Dallas S, Sensenhauser C, Batheja A, Singer M, Markowska M, Zakszewski C, et al. De-risking bio-therapeutics for possible drug interactions using cryopreserved human hepatocytes. Curr Drug Metab. 2012;13:923–9. doi: 10.2174/138920012802138589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickmann LJ, Patel SK, Rock DA, Wienkers LC, Slatter JG. Effects of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and an anti-IL-6 monoclonal antibody on drug-metabolizing enzymes in human hepatocyte culture. Drug Metab Dispos. 2011;39(8):1415–22. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.038679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickmann LJ, Patel SK, Wienkers LC, Slatter JG. Effects of interleukin 1beta (IL-1beta) and IL-1beta/interleukin 6 (IL-6) combinations on drug metabolizing enzymes in human hepatocyte culture. Curr Drug Metab. 2012;13(7):930–7. doi: 10.2174/138920012802138642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dallas SC, Souvik; Sensenhauser, Carlo; Batheja, Ameesha; Singer, Monica; Silva, Jose. Interleukins-12 and -23 do not alter expression or activity of multiple CYP enzymes in cryopreserved human hepatocytes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2013;41:689–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Yang KH, Lee MG. Effects of endotoxin derived from Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide on the pharmacokinetics of drugs. Arch Pharm Res. 2008;31(9):1073–86. doi: 10.1007/s12272-001-1272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashino T, Arima Y, Shioda S, Iwakura Y, Numazawa S, Yoshida T. Effect of interleukin-6 neutralization on CYP3A11 and metallothionein-1/2 expressions in arthritic mouse liver. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;558(1–3):199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ling S, Jamali F. The effect of infliximab on hepatic cytochrome P450 and pharmacokinetics of verapamil in rats with pre-adjuvant arthritis: a drug-disease and drug-drug interaction. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009;105(1):24–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2009.00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dickmann LJ, McBride HJ, Patel SK, Miner K, Wienkers LC, Slatter JG. Murine collagen antibody induced arthritis (CAIA) and primary mouse hepatocyte culture as models to study cytochrome P450 suppression. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83(12):1682–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taub R. Liver regeneration: from myth to mechanism. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5(10):836–47. doi: 10.1038/nrm1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rhodes B, Furnrohr BG, Vyse TJ. C-reactive protein in rheumatology: biology and genetics. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7(5):282–9. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang X, Zhang B, Molony C, Chudin E, Hao K, Zhu J, et al. Systematic genetic and genomic analysis of cytochrome P450 enzyme activities in human liver. Genome Res. 2010;20(8):1020–36. doi: 10.1101/gr.103341.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen YL, Le Vraux V, Leneveu A, Dreyfus F, Stheneur A, Florentin I, et al. Acute-phase response, interleukin-6, and alteration of cyclosporine pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;55(6):649–60. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1994.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rivory LP, Slaviero KA, Clarke SJ. Hepatic cytochrome P450 3A drug metabolism is reduced in cancer patients who have an acute-phase response. Br J Cancer. 2002;87(3):277–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frye RF, Schneider VM, Frye CS, Feldman AM. Plasma levels of TNF-alpha and IL-6 are inversely related to cytochrome P450-dependent drug metabolism in patients with congestive heart failure. J Card Fail. 2002;8(5):315–9. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2002.127773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haas CE, Kaufman DC, Jones CE, Burstein AH, Reiss W. Cytochrome P450 3A4 activity after surgical stress. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(5):1338–46. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000063040.24541.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maini RN, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR, Smolen JS, Davis D, Macfarlane JD, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of multiple intravenous infusions of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody combined with low-dose weekly methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(9):1552–63. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199809)41:9<1552::AID-ART5>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abbott Laboratories. Humira® US Prescribing Information. 2011. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/125057s0276lbl.pdf. Accessed 20 May 2013.

- 23.Janssen Biotech Inc. Simponi® US prescribing information. 2011. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/125289s0064lbl.pdf. Accessed 20 May 2013.

- 24.UCB Inc. Cimzia® US prescribing information. 2012. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/125160s0174lbl.pdf. Accessed 20 May 2013.

- 25.Zhou H, Mayer PR, Wajdula J, Fatenejad S. Unaltered etanercept pharmacokinetics with concurrent methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;44(11):1235–43. doi: 10.1177/0091270004268049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vasquez EM, Pollak R. OKT3 therapy increases cyclosporine blood levels. Clin Transplant. 1997;11(1):38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strehlau J, Pape L, Offner G, Nashan B, Ehrich JH. Interleukin-2 receptor antibody-induced alterations of ciclosporin dose requirements in paediatric transplant recipients. Lancet. 2000;356(9238):1327–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02822-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chatenoud L, Ferran C, Legendre C, Thouard I, Merite S, Reuter A, et al. In vivo cell activation following OKT3 administration. Systemic cytokine release and modulation by corticosteroids. Transplantation. 1990;49(4):697–702. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199004000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tinel M, Robin MA, Doostzadeh J, Maratrat M, Ballet F, Fardel N, et al. The interleukin-2 receptor down-regulates the expression of cytochrome P450 in cultured rat hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 1995;109(5):1589–99. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90648-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thal C, el Kahwaji J, Loeper J, Tinel M, Doostzadeh J, Labbe G, et al. Administration of high doses of human recombinant interleukin-2 decreases the expression of several cytochromes P-450 in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;268(1):515–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sunman JA, Hawke RL, LeCluyse EL, Kashuba AD. Kupffer cell-mediated IL-2 suppression of CYP3A activity in human hepatocytes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2004;32(3):359–63. doi: 10.1124/dmd.32.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elkahwaji J, Robin MA, Berson A, Tinel M, Letteron P, Labbe G, et al. Decrease in hepatic cytochrome P450 after interleukin-2 immunotherapy. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;57(8):951–4. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(98)00372-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piscitelli SC, Vogel S, Figg WD, Raje S, Forrest A, Metcalf JA, et al. Alteration in indinavir clearance during interleukin-2 infusions in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Pharmacotherapy. 1998;18(6):1212–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Machavaram KK, Almond LM, Rostami-Hodjegan A, Gardner I, Jamei M, Tay S, et al. A physiologically-based pharmacokinetic modelling approach to predict disease-drug interactions: suppression of CYP3A by IL-6. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013. doi:10.1038/clpt.2013.79. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Abuqayyas L, Balthasar JP. Pharmacokinetic mAb-mAb interaction: anti-VEGF mAb decreases the distribution of anti-CEA mAb into colorectal tumor xenografts. AAPS J. 2012;14(3):445–55. doi: 10.1208/s12248-012-9357-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheiner LB, Rosenberg B, Marathe VV. Estimation of population characteristics of pharmacokinetic parameters from routine clinical data. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1977;5(5):445–79. doi: 10.1007/BF01061728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.FDA. Drug interaction studies—study design, data analysis, implications for dosing, and labeling recommendations. Draft Guidance for Industry. 2012. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm064982.htm. Accessed 20 May 2013.

- 38.Hu C, Zhang J, Zhou H. Confirmatory analysis for phase III population pharmacokinetics. Pharm Stat. 2011;10(1):14–26. doi: 10.1002/pst.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu C, Zhou H. An improved approach for confirmatory phase III population pharmacokinetic analysis. J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;48(7):812–22. doi: 10.1177/0091270008318670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duan JZ. Applications of population pharmacokinetics in current drug labelling. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2007;32(1):57–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2007.00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou H. Population-based assessments of clinical drug-drug interactions: qualitative indices or quantitative measures? J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46(11):1268–89. doi: 10.1177/0091270006294278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grimm SW, Einolf HJ, Hall SD, He K, Lim H-K, Ling K-HJ, et al. The conduct of in vitro studies to address time-dependent inhibition of drug-metabolizing enzymes: a perspective of the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:1355–70. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.026716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chu V, Einolf HJ, Evers R, Kumar G, Moore D, Ripp S, et al. In vitro and in vivo induction of cytochrome P450: a survey of the current practices and recommendations: a Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America perspective. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:1339–54. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.027029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.EMA. Guideline on the clinical investigation of the pharmacokinetics of therapeutic proteins. 2007. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003029.pdf. Accessed 20 May 2013.