Abstract

Lobomycosis, a fungal disease of the skin and subcutaneous tissues caused by Lacazia loboi, is sometimes referred to as a zoonotic disease because it affects only specific delphinidae and humans; however, the evidence that it can be transferred directly to humans from dolphins is weak. Dolphins have also been postulated to be responsible for an apparent geographic expansion of the disease in humans. Morphological and molecular differences between the human and dolphin organisms, differences in geographic distribution of the diseases between dolphins and humans, the existence of only a single documented case of presumed zoonotic transmission, and anecdotal evidence of lack of transmission to humans following accidental inoculation of tissue from infected dolphins do not support the hypothesis that dolphins infected with L. loboi represent a zoonotic hazard for humans. In addition, the lack of human cases in communities adjacent to coastal estuaries with a high prevalence of lobomycosis in dolphins, such as the Indian River Lagoon in Florida (IRL), suggests that direct or indirect transmission of L. loboi from dolphins to humans occurs rarely, if at all. Nonetheless, attention to personal hygiene and general principals of infection control are always appropriate when handling tissues from an animal with a presumptive diagnosis of a mycotic or fungal disease.

Key Words: Lobomycosis, Lacazia loboi, Zoonoses, Dolphins, Marine mammals, Mycoses

Introduction

Lobomycosis, a fungal disease of the skin and subcutaneous tissues described originally in 1931 is caused by the uncultivable onygenale fungus Lacazia loboi (Herr et al. 2001). Uniquely, this infectious agent is found naturally only in humans and dolphins and has been considered to represent a zoonotic disease, although most authors recognize the rarity of dolphin-to-human transmission (Bermudez et al. 2009, Paniz-Mondolfi et al. 2012, Waltzek et al. 2012). In dolphins, lobomycosis is characterized by firm, white-to-grayish nodules and verrucous plaques on the dorsal and pectoral fins, head, peduncle, and tail that may form large confluent patches (Fig. 1) (Migaki et al. 1971, Reif et al. 2006). Histologically, the lesions consist of multiple granulomas in the subepidermal tissue with inflammatory infiltrates containing histiocytic cells and multinucleated giant cells. Yeast-like round to lemon-shaped cells with thick, refractile walls measuring 7–12 μm are arranged in short chains connected by tubular bridges. These cells stain with methenamine silver and generally resemble the L. loboi described in humans (Bossart et al. 1984, Reif et al. 2006).

FIG. 1.

Dolphin with extensive lesions of lobomycosis from the Indian River Lagoon, Florida. Photograph courtesy of E. Howells, Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution at Florida Atlantic University, 2007. Reprinted with permission.

Thus, the concept that L. loboi might be transmitted to humans from dolphins as a zoonosis seems logical upon initial consideration and indicates that appropriate precautions be used when handling presumptively infected dolphins. Furthermore, recent reports describing lobomycosis or lobomycosis-like disease (LLD) (based on photographic evidence) in dolphins from the Indian Ocean (Kiszla et al. 2009), the Japanese coast (Shirakihara et al. 2008), the western Pacific (Van Bressem et al. 2007, Van Bressem et al. 2009) and the North Carolina coast (Rotstein et al. 2009), as well as in humans from the African continent (Al-Daraji et al. 2008) and the European coast (Papadavid et al. 2012), may indicate that the ecological niche for the disease is expanding. Thus, the risk for transmission to humans, if real, may also increase. Alternatively, increased recognition and reporting may account for the apparent geographical expansion. Several authors have postulated that geographic expansion of lobomycosis in humans may be attributable to direct or indirect contact with infected dolphins that presumably migrated from endemic areas (Paniz-Mondolfi et al. 2012, Papadavid et al. 2012). Direct and indirect human contact with dolphins has expanded due to the increased number of dolphins under managed care in aquaria and commercial exhibitions, swim with dolphin programs for recreational or therapeutic benefit, and occupational exposures of veterinarians, marine biologists, and others who handle dolphins during health assessments, rescue operations, and rehabilitation efforts of stranded or injured animals.

Natural and Experimental Transmission of L. loboi

Support for the zoonotic potential of L. loboi is found in a report describing lobomycosis in a previously healthy 24-year-old aquarium attendant in France who worked in an aquarium pool with an infected bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) (Symmers 1983). The dolphin had been caught in the Bay of Biscay off the French–Spanish coast and had multiple nodular lesions of the skin, with histologic evidence of yeast-like fungal cells on lesion biopsy. The patient developed a granuloma on the hand accompanied by supratrochlear lymphadenopathy approximately 3 months after regular exposure to the infected dolphin in the hospital pool in which it was being held. Histologically, the patient's lesions were characteristic of lobomycosis and contained short chains of fungal cells.

With the exception of this single case, further evidence that L. loboi can be transmitted from dolphins to humans under natural conditions is limited. Few cases have been reported in humans from coastal environments (Paniz-Mondolfi et al. 2012). The first was a patient from Surinam (Wiersema et al. 1965), an area where lobomycosis occurs in Guiana dolphins (Sotalia guianensis) that inhabit the Surinam River estuary (DeVries et al. 1973). A second case developed in a young man from South Africa who was an avid swimmer and diver (Al-Daraji et al. 2008). The third occurred in a fisherman from Venezuela who developed lesions on the ear after being pierced with a fishing hook in a coastal area where an affected dolphin was observed (Bermudez et al. 2009). Most recently, lobomycosis was diagnosed in a female farmer with hypoglobulinemia and common variable immunodeficiency and hepatitis who lived on the Greek coast (Papadavid et al. 2012). These observations suggest that the marine environment may occasionally be a source of infection for both species but do not implicate direct transmission from dolphins to humans (Bermudez et al. 2009).

L. loboi can be transmitted directly from human to human under highly unusual circumstances. The first example occurred accidentally following resection of an auricular lesion and placement of a skin autograft obtained from the patient's shoulder where the lesion eventually developed. Transmission was believed to occur through a contaminated needle used to anesthetize the resection site on the ear and then for the skin graft site (Azulay et al. 1970). A second accidental transmission of lobomycosis occurred in a laboratory worker who collected skin biopsies from infected patients in Brazil, purified fungal cells from the biopsy material, and inoculated L. loboi into mice to propagate the organism in the laboratory (Rosa et al. 2009). Similarly, experimental inoculation of a laboratory scientist with yeast-like cells from a human patient shows that under unusual circumstances, Lacazia of human origin can be transmitted to other humans (Borelli 1961). L. loboi can also be transmitted by direct inoculation into mice, hamsters, tortoises, and armadillos (Paniz-Mondolfi et al. 2012). However, a report by a dermatologist who suffered an accidental laceration during a biopsy procedure of a dolphin with lobomycosis (Norton 2006) and anecdotal reports by a veterinary pathologist who was exposed to tissues from infected dolphins through wounds incurred during autopsy on several occasions (G.D. Bossart, personal communication, 2010) without subsequent development of lobomycosis suggest that transmission from dolphins to humans, even through direct inoculation, is unlikely in immunocompetent individuals.

Morphologic and Molecular Studies of L. loboi in Humans and Dolphins

Several lines of evidence support the contention that dolphin to human transmission of L. loboi is extremely rare. First, the organisms demonstrated in tissues from infected dolphins and humans differ morphologically (Fig. 2). The Lacazia cells seen in dolphin tissues are smaller than those in lesions from humans under light microscopy (Haubold et al. 2000). Morphometric analysis of tissue showed that human Lacazia have approximately twice the area and are 30% longer in their major axis than the organisms in dolphin tissues (Haubold et al. 2000). Furthermore, the ultrastructural characteristics of cell wall destruction differ between dolphins and humans. The authors postulated that the morphologic differences may result from environmental differences in salinity, temperature, and an aqueous environment, or, alternatively that the differences may represent the organism's cellular response to physiologic conditions within the host. A third possibility is that the organisms from humans and dolphins represent true phylogenetic divergence (Haubold et al. 2000).

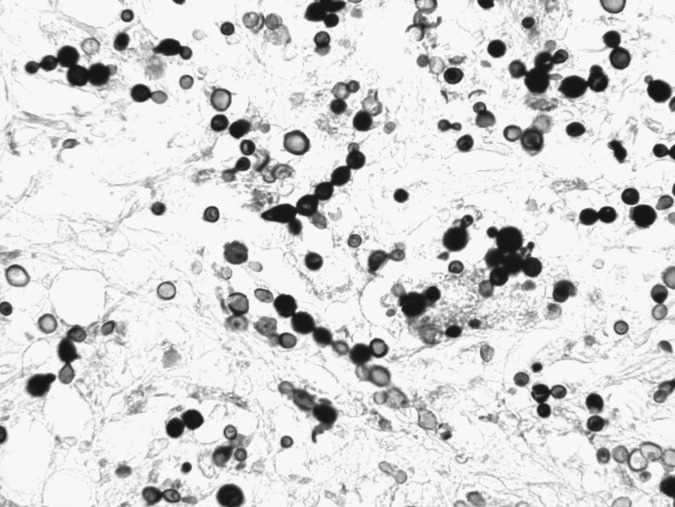

FIG. 2.

Photomicrograph of dermal tissue from a dolphin with lobomycosis. The yeast-like cells are seen singly and in chains connected by tube-like bridges, characteristic of Lacazia loboi. Gomori methenamine silver stain. Magnification, 400×.

In support of the latter hypothesis, molecular sequencing of ribosomal DNA from an infected dolphin showed a novel sequence related more closely to Paracoccidiodes brasiliensis than to L. loboi of human origin (Esperón et al. 2012). This recent evidence is supported by an earlier study that showed that ribosomal RNA gene sequences from an infected dolphin were 97% homologous with P. brasiliensis (Rotstein et al. 2009). However, sera from infected dolphins recognized the immuno-dominant ≈193-kDa antigen from an extract of human L. loboi more strongly than the gp43 antigen of P. brasiliensis in western blotting analyses (Mendoza et al. 2008). Serological cross-reactivity between serum from human patients with lobomycosis and P. brasiliensis has also been demonstrated (Camargo et al. 1998). However, direct molecular and phylogenetic comparison of Lacazia of dolphin and human origin has not been reported.

Epidemiologic Characteristics of Human and Dolphin Lobomycosis

The endemicity and natural history of lobomycosis in dolphins and humans are strongly contrasted. Lobomycosis was first reported in a Florida bottlenose dolphin (T. truncatus) in the Gulf of Mexico in 1971 (Migaki et al. 1971) and is endemic in south Florida's coastal estuaries. Early reports describe sightings of apparently infected dolphins in the Florida Keys, and the Indian River Lagoon (IRL) dating to the 1950s (Caldwell et al. 1975). The IRL, an estuary that extends 156 miles along approximately 40% of Florida's eastern coastline, is a hyperendemic locale for the disease in dolphins. Capture–release health assessment studies showed that the prevalence in the IRL is approximately 10% and that the disease aggregates in the southern reaches of the estuary (Reif et al. 2006). In this zone, an area with slightly higher water temperatures and lower salinity than the northern IRL, the prevalence is higher, approaching 17% (Murdoch et al. 2008). Geographic differences in the prevalence of lobomycosis and LLD (Burdette Hart et al. 2011) suggest that specific features of the marine environment create a suitable niche for Lacazia and potential transmission to dolphins or humans. However, human lobomycosis has not been reported among approximately 1.7 million persons who inhabit the coastal counties bordering the IRL. Extensive human exposure to the IRL through recreational activities suggests that the organism could be introduced into the dermis through cuts, punctures, and abrasions, if, in fact, the Lacazia of dolphins was a human pathogen under natural circumstances. Lobomycosis is extremely rare in industrialized countries, diagnosed almost exclusively among persons with a history of exposure to tropical environments (Elsayed et al. 2004). For example, the first case reported in the United States occurred in 2000 in a traveler who had visited Venezuela frequently and was likely exposed through contact with a waterfall (Burns et al. 2000).

Conversely, lobomycosis in humans is endemic in tropical regions of Central and South America and is most frequently associated with exposure to fresh water habitats, vegetation, and soil (Rodriguez-Toro 1993). Lobomycosis associated with occupational exposures to farmers, hunters, mineral explorers (gold panning), rubber workers, fishermen, and others has been reported widely in endemic areas (Fuchs et al. 1990, Rodriguez-Toro 1993). Transmission in occupational and residential settings appears to occur by cutaneous introduction of the organism through trauma, including cuts, snakebites, ray stings, insect bites, and abrasions on exposed surfaces of the body. Several high-risk occupational groups have regular exposure to fresh water aqueous environments. However, lobomycosis has not been reported in either of the two freshwater species of dolphins that inhabit the Amazon and Orinoco river basins of Brazil and Venezuela where the human disease is endemic, botos (Inia geoffrensis) or tucuxis (Sotalia fluviatilis) (Paniz-Mondolfi et al. 2009).

The Immune System in Dolphin and Human Lobomycosis

Defects in the immune system may constitute a common pathway for infection of humans and dolphins with Lacazia. Lobomycosis has been described in a dolphin with hypogammaglobulinemia and chronic-active hepatitis (Bossart 1984), and similarly in a woman with hypoglobulinemia and cholestatic hepatitis (Papadavid et al. 2012), suggesting that the disease may occur in immunocompromised dolphins and humans. However, only a single case of lobomycosis has been described in a patient infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (Xavier et al. 2006).

In human lobomycosis, impairment of cellular immunity is characterized by failure to become sensitized to dinitrochlorobenzene, negative hypersensitivity skin tests to common bacterial and fungal pathogens, and a delayed skin allograft rejection (Pecher and Fuchs 1988). Depressed cellular immunity may be responsible for the chronicity of the lesions and failure to resolve spontaneously (Rodriguez-Toro 1993). Mononuclear cells obtained from patients with lobomycosis exhibit cytokine profiles predominantly of the Th2 profile (Vilani-Moreno et al. 2004a). A higher frequency of immunosuppressive cytokines transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β1) and interleukin-10 (IL-10) found in the skin lesions of patients suggests that immunoregulatory disturbances may be responsible for the large number of fungal cells present in the granulomas and lack of pathogen containment (Vilani-Moreno et al. 2005, Vilani-Moreno et al. 2011).

Similarly, dolphins with lobomycosis have multiple defects in adaptive immunity (Reif et al. 2009). Compared to healthy dolphins, affected dolphins had reduced numbers of circulating helper T cells and mature and immature B cells as well as a reduction in the number of cells expressing major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules. Mitogen-induced lymphocyte proliferation of T and B cells was reduced substantially. Changes in lymphocyte surface markers and proliferation were accompanied by reduced antibody titers to common marine microorganisms. No evidence for impaired phagocytosis in monocytes and granulocytes obtained from dolphins with lobomycosis was found, compatible with a report that phagocytosis of L. loboi by monocytes from human patients did not differ from controls (Vilani-Moreno et al. 2004b). Despite evidence that humans and dolphins have substantial defects in cell-mediated immunity, it remains unclear whether infection with Lacazia represents an opportunistic infection or whether infection leads to secondary changes in immune function (Reif et al. 2009, Honda and Raugi 2013).

Conclusions

In summary, morphological and molecular differences between the human and dolphin organisms, differences in geographic distribution, the lack of human cases in an endemic, high-prevalence area of dolphin lobomycosis, the existence of only a single documented case of presumed zoonotic transmission, and anecdotal evidence suggest that direct transmission of L. loboi from dolphins to humans is highly unusual. The risk of acquiring a Lacazia infection from a dolphin with clinical evidence of lobomycosis appears to be very low. Nonetheless, appropriate hygiene and care are always appropriate when handling tissues from an animal with a presumptive diagnosis of an infectious disease.

Acknowledgment

The work was supported in part by Florida's Protect Wild Dolphins specialty license plate fund, through Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution at Florida Atlantic University.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Al-Daraji WI. Husain E. Robson A. Lobomycosis in African patients. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:234–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azulay RD. Carneiro J de A. Andrade LC. Blastomicose de Jorge Lobo. Contribuçao ao estudio da etiologia, inoculaçao experimental, imunologia e patologia da doença. An Bras Dermatol. 1970;45:47–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermudez L. Van Bressem MF. Reyes-Jaimes O. Sayegh AJ, et al. Lobomycosis in man and lobomycosis-like disease in bottlenose dolphin, Venezuela. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1301–1303. doi: 10.3201/eid1508.090347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borelli D. Lobomicosis experimental. Dermatol Venez. 1961;3:72–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bossart GD. Suspected acquired immunodeficiency in an Atlantic bottlenose dolphin with chronic-active hepatitis and lobomycosis. J Am Vet Med Assn. 1984;185:1413–1414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdettt Hart L. Rotstein DS. Wells RS. Bassos-Hull K, et al. Lacaziosis and lacaziosis-like prevalence among wild, common bottlenose dolphins Tursiops truncatus from the west coast of Florida, USA. Dis Aquatic Organ. 2011;95:49–56. doi: 10.3354/dao02345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns RA. Toy JS. Woods C. Padhye AA, et al. Report of the first human case of lobomycosis in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1283–1285. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.3.1283-1285.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell DK. Caldwell MC. Woodard JC. Ajello L, et al. Lobomycosis as a disease of the Atlantic Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus Montagu, 1821) Amer J Trop Med Hyg. 1975;24:105–114. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1975.24.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camargo ZP. Baruzzi RG. Maeda SM. Floriano MC. Antigenic relationship between Loboa loboi and Paracoccidioides brasiliensis as shown by serological methods. Med Mycol. 1998;36:413–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries GA. Laarman JJ. A case of Lobo's disease in the dolphin Sotalia guianensis. Aquat Mamm. 1973;1:26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Elsayed S. Kuhn SM. Barber D. Church DL, et al. Human case of lobomycosis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:715–18. doi: 10.3201/eid1004.030416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esperón F. García-Párraga D. Bellière EN. Sánchez-Vizcaíno JM. Molecular diagnosis of lobomycosis-like disease in a bottlenose dolphin in captivity. Med Mycol. 2102;50:106–109. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2011.594100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs J. Milbradt R. Pecher SA. Lobomycosis (keloidal blastomycosis): Case reports and overview. Cutis. 1990;46:227–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haubold EM. Cooper CR., Jr Wen JW. Mcginnis MR, et al. Comparative morphology of Lacazia loboi (syn. Loboa loboi) in dolphins and humans. Med Mycol. 2000;38:9–14. doi: 10.1080/mmy.38.1.9.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herr RA. Tarcha EJ. Taborda PR. Taylor JW, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of Lacazia loboi places this previously uncharacterized pathogen within the dimorphic Onygenales. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:309–314. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.1.309-314.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner LK. Raugi GJ. Fivenson DP, editor; Butler DF, editor; Callen JP, editor; Quirk C, editor; Elston DM, editor. Lobomycosis. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1092451.htm. [Mar 21;2013 ]. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1092451.htm

- Kiszka J. Van Bressem MF. Pusineri C. Lobomycosis-like disease and other skin conditions in Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins Tursiops aduncus from the Indian Ocean. Dis Aquat Organ. 2009;84:151–157. doi: 10.3354/dao02037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza L. Belone AF. Vilela R. Rehtanz M, et al. Use of sera from humans and dolphins with lacaziosis and sera from experimentally infected mice for Western blot analyses of Lacazia loboi antigens. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15:164–167. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00201-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migaki G. Valerio MG. Irvine B. Garner FM. Lobo's disease in an Atlantic bottle-nosed dolphin. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1971;159:578–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch ME. Reif JS. Mazzoil M. McCulloch SD, et al. Lobomycosis in bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) from the Indian River Lagoon, Florida: estimation of prevalence, temporal trends, and spatial distribution. EcoHealth. 2008;5:289–297. doi: 10.1007/s10393-008-0187-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton SA. Dolphin-to-human transmission of lobomycosis? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:723–724. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadavid E. Dalamaga M. Kapniari I. Pantelidaki E, et al. Lobomycosis: A case from Southeastern Europe and review of the literature. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;6:65–69. doi: 10.3315/jdcr.2012.1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paniz-Mondolfi AE. Sander-Hoffman L. Lobomycosis in inshore and estuarine dolphins. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:672–673. doi: 10.3201/eid1504.080955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paniz-Mondolfi AE. Talhari C. Sander-Hoffman L. Connor DL, et al. Lobomycosis: An emerging disease in humans and delphinidae. Mycoses. 2012;55:298–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2012.02184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecher SA. Fuchs J. Cellular immunity in lobomycosis (keloidal blastomycosis) Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 1988;16:413–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reif JS. Mazzoil MS. McCulloch SD. Varela R, et al. Lobomycosis in Atlantic bottlenose dolphins from the Indian River Lagoon, Florida. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2006;228:104–108. doi: 10.2460/javma.228.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reif JS. Peden-Adams MM. Romano TA. Rice CD, et al. Immune dysfunction in Atlantic bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) with lobomycosis. Med Mycol. 2009;47:125–35. doi: 10.1080/13693780802178493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Toro G. Lobomycosis. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:324–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1993.tb01466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa PS. Soares CT. Belone Ade F. Vilela R, et al. Accidental Jorge Lobo's disease in a worker dealing with Lacazia loboi infected mice: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:67. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-3-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotstein DS. Burdett LG. McLellan W. Schwacke L, et al. Lobomycosis in offshore bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus), North Carolina. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:588–590. doi: 10.3201/eid1504.081358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirakihara M. Amano M. Van Bressem MF. Skin lesions in a resident population of Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins in Japan. Paper SC/60/DW6 presented to the IWC Scientific Committee; Santiago, Chile. Jun 27;2008 ; Cambridge: IWC; [Jul 11;2013 ]. 30 May. [Google Scholar]

- Symmers WS. A possible case of Lobo's disease acquired in Europe from a bottle-nosed dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1983;76:777–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bressem MF. Van Waerebeek K. Reyes JC. Félix F, et al. A preliminary overview of skin and skeletal diseases and traumata in small cetaceans from South American waters. Lat Am J Aquat Mamm. 2007;6:7–42. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bressem MF. Santos MO. Oshima JE. Skin diseases in Guiana dolphins (Sotalia guianensis) from the Paranagua´ estuary, Brazil: a possible indicator of a compromised marine environment. Mar Environ Res. 2009;67:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilani-Moreno FR. Lauris JR. Opromolla DV. Cytokine quantification in the supernatant of mononuclear cell cultures and in blood serum from patients with Jorge Lobo's disease. Mycopathologia. 2004a;158:17–24. doi: 10.1023/b:myco.0000038433.76437.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilani-Moreno FR. Silva LM. Opromolla DV. Evaluation of the phagocytic activity of peripheral blood monocytes of patients with Jorge Lobo's disease. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2004b;37:165–168. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822004000200010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilani-Moreno FR. Belone AF. Soares CT. Opromolla DV. Immunohistochemical characterization of the cellular infiltrate in Jorge Lobo's disease. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2005;22:44–49. doi: 10.1016/s1130-1406(05)70006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilani-Moreno FR. Belone AF. Lara VS. Venturini J, et al. Detection of cytokines and nitric oxide synthase in skin lesions of Jorge Lobo's disease patients. Med Mycol. 2011;49:643–648. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2010.547993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltzek TB. Cortés-Hinojosa G. Wellehan JF., Jr Gray GC. Marine mammal zoonoses: A review of disease manifestations. Zoonoses Public Health. 2012;59:521–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2012.01492.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiersema JP. Niemel PLA. Lobo's disease in Surinam patients. Trop Geogr Med. 1965;17:89–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xavier MB. Ferreira MM. Quaresma JA. de Brito A. HIV and lacaziosis, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:526–527. doi: 10.3201/eid1203.051426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]