Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) against CD19 have been shown to direct T-cells to specifically target B-lineage malignant cells in animal models and clinical trials, with efficient tumor cell lysis. However, in some cases, there has been insufficient persistence of effector cells, limiting clinical efficacy. We propose gene transfer to hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPC) as a novel approach to deliver the CD19-specific CAR, with potential for ensuring persistent production of effector cells of multiple lineages targeting B-lineage malignant cells. Assessments were performed using in vitro myeloid or natural killer (NK) cell differentiation of human HSPCs transduced with lentiviral vectors carrying first and second generations of CD19-specific CAR. Gene transfer did not impair hematopoietic differentiation and cell proliferation when transduced at 1–2 copies/cell. CAR-bearing myeloid and NK cells specifically lysed CD19-positive cells, with second-generation CAR including CD28 domains being more efficient in NK cells. Our results provide evidence for the feasibility and efficacy of the modification of HSPC with CAR as a strategy for generating multiple lineages of effector cells for immunotherapy against B-lineage malignancies to augment graft-versus-leukemia activity.

De Oliveira and colleagues present a method to continuously generate effector cells targeting B cell neoplasms in vivo by modifying human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) to carry a CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR). The modified HSCs produce effector cells of multiple lineages with cytolytic activity against CD19-expressing cells.

Introduction

Cancer therapy has evolved over the last few decades, and improvements in survival and quality of life have been achieved through new drugs and protocols, better supportive care, and the advent of targeted therapy (Lesterhuis et al., 2011). The possibility of using the patient's own immune system, coupled with in-depth understanding of cancer biology and advances in gene transfer techniques, has led to multiple developments in cancer immunotherapy (Zarour and Ferrone, 2011). Clinical experience with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) as a therapeutic option for hematological malignancies has strengthened the evidence that the immune response plays an important role against cancer. Chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) have been conceived in an attempt to redirect targeting of immune cells unhindered by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) restriction, now progressing to clinical trials (Ertl et al., 2011; Kohn et al., 2011).

Targeting of the CD19 antigen has emerged as a promising approach, inspired by the success of the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody Rituximab (Croxtall, 2011). CD19 is an attractive target as it is restricted to B-lineage, not lost in the neoplastic transformation, present on most of the B-lineage malignancies and absent on hematopoietic stem cells, and ablation of CD19-positive cells is compatible with life (Uckun et al., 1988). Preclinical and clinical data show proof of concept, but a major limitation in clinical applications is the limited persistence of modified effector cells, typically ex vivo expanded mature T-cells (Kochenderfer et al., 2010; Porter et al., 2011; Savoldo et al., 2011).

Modification of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) has been proposed as a therapy for genetic diseases, with successful examples being gene therapy clinical trials for adenosine deaminase-deficient severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) (Gaspar et al., 2011) and X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (Cartier et al., 2009). Modification of HSPCs with CAR brings the prospect of long-term transgene persistence as result of successful engraftment of gene-modified HSPCs, leading to CAR expression in multiple hematopoietic lineages, amplifying the potential antileukemic activity (Kohn and Candotti, 2009; Doering et al., 2010; Kohn et al., 2013). Recent publications have shown successful in vivo development of T-cells from genetically engineered human HSPCs for immunotherapy applications against HIV or cancer (Vatakis et al., 2011; Kitchen et al., 2012; Giannoni et al., 2013).

Using previously published CD19-specific CAR constructs (Cooper et al., 2003; Ertl et al., 2011) cloned into lentiviral vectors, we evaluated the potential for modification of human HSPC with CAR as a novel approach for immunotherapy of hematological malignancies. The hypothesis is that HSPCs transduced with CD19-specific CAR will give rise to not only persistent production of target-specific T-lymphocytes, but also effector cells in multiple lineages, amplifying the antileukemic effect. The presence of CAR-modified myeloid and natural killer (NK) cells is especially attractive as these are the first cells to be produced after HSPC transplantation, becoming the initial effectors until CAR-modified T-cells arise from the thymus, augmenting the graft-versus-leukemia activity. In order to test the concept and its feasibility, human HSPCs modified to express anti-CD19 CAR were evaluated in vitro after differentiation cultures into myeloid or NK cells, and functional assays were conducted to evaluate specific lysis of CD19-positive targets. Use of CAR-transduced HSPCs to produce multiple leukocyte subtypes with specific cytolytic activity may provide additional complement to the more traditional cancer immunotherapy approach using mature T-lymphocytes.

Materials and Methods

Lentiviral vectors

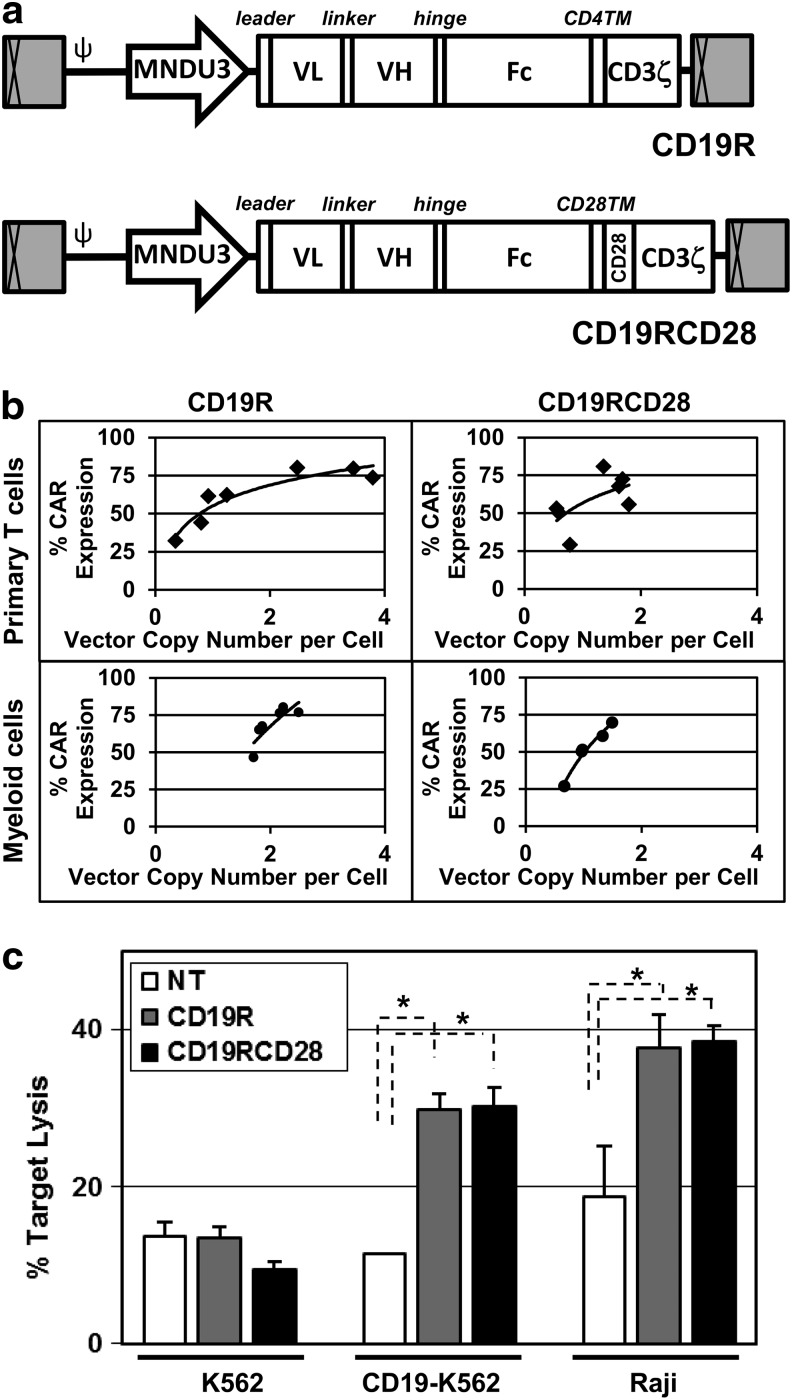

The first-generation CAR construct, CD19R, has a single-chain variable domain (scFv) from the CD19-specific murine IgG1 monoclonal antibody FMC63 linked to a spacer derived from the Fc and hinge regions from the human IgG4 heavy chain, fused to residues from the human CD4 transmembrane region, followed by the cytoplasmic domain of the human CD3zeta chain (Cooper et al., 2003). The second-generation CAR construct, CD19RCD28, has the scFv from FMC63 and the human IgG4 spacer followed by the human CD28 transmembrane and intracellular domains linked to CD3zeta (Kowolik et al., 2006). Both anti-CD19 CAR constructs were cloned into the CCL backbone (Zufferey et al., 1997) with the MND LTR U3 region as the internal enhancer/promoter (Halene et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2003) producing the vectors CCLc-MNDU3-CD19R (CD19R) and CCLc-MNDU3-CD19RCD28 (CD19RCD28) (Fig. 1a). Vectors CCLc-MNDU3-EGFP and CCLc-MNDU3-luciferase were used to transduce HSPCs with enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) or firefly luciferase (LUC) as control vectors for transduction protocols. Vector preparations were produced by triple-plasmid transfection of 5 μg of pCCL-cPPT-MNDU3-CD19R or pCCL-cPPT-MNDU3-CD19RCD28, 5 μg of a HIV-1 gag/pol-expressing plasmid (pCMVΔR8.91) (Zufferey et al., 1997) and 1.0 μg of the pMD.G plasmid to express the vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (Naldini et al., 1996). 293T cells were plated on poly-L-lysine-coated 10 cm plates at 5×106 cells per plate in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; D10) and transfection was performed 24 hr later using standard TransIT-293 protocol (Mirus Bio, Madison, WI). Eighteen hours later, transfected cells were treated with 10 mM sodium butyrate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and 20 mM HEPES in D10. After 8–12 hr, the cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then fresh D10 with 20 mM HEPES was added. Vector-containing supernatant was harvested 48 hr later. Larger-scale preparations (2–5 liters) of vectors concentrated by tangential flow filtration were produced as described, with titers measured by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis of vector copies in transduced HT29 cells (Cooper et al., 2011).

FIG. 1.

Lentiviral transduction of human primary cells. (a) Lentiviral vectors carrying CD19-specific CARs (CD19R and CD19RCD28) driven by the MNDU3 promoter (diagram to scale). The enhancer-deleted, SIN long terminal repeats are depicted as the gray boxes with cross-hatches at each end and the elements of the HIV-1 backbone are illustrated as is the MNDU3 promoter used to drive CAR expression. Components of the CAR are indicated as the signal peptide (leader), the single chain antibody variable light (VL) and heavy (VH) chains joined by a linker, the Fc spacer derived from the human Fc receptor, the transmembrane (TM) sequences, and the CD3ζ and CD28 signaling domains. (b) CAR expression versus provirus copy numbers in transduced primary human T-cells (black diamonds) for CD19R (left upper panel) or CD19RCD28 (right upper panel), and transduced in vitro-differentiated human myeloid cells (black circles) for CD19R (left lower panel) or CD19RCD28 (right lower panel) (n=3). (c) Cytotoxicity by primary human T-cells activated from PBMC, nontransduced (NT, white columns) and transduced with CD19R (gray columns) or CD19RCD28 (black columns), against K562 (p=0.0679), CD19-K562 (p<0.0001), and Raji (p<0.0001) target cells, at an E:T ratio of 20:1. Values represent arithmetic means of results from four experiments, error bars represent mean+SEM, and asterisks indicate statistical significance. CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; E:T ratio, effector-to-target ratio; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; SEM, standard error of mean; SIN, self-inactivating.

Human and murine cell lines

The human cell lines Raji (CD19-positive) cells, K562 (CD19-negative) cells, and Jurkat cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA), and kept in RPMI medium containing 10% FBS (R10 medium). DL-1-transduced OP9 murine stroma cells (OP9-DL1) were provided by Gay Crooks (University of California–Los Angeles [UCLA], Los Angeles, CA) and grown in alpha-MEM medium (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) containing 20% FBS (Alpha-20 medium).

The full-length human CD19 cDNA was excised from pCMV6-CD19 (Origene, Rockville, MD) using EcoRI and PmeI and used to replace eGFP in the plasmid pCCLc-MNDU3-eGFP, producing CCLc-MNDU3-huCD19, used to transduce K562 cell line into a CD19-positive target. K562 cells were transduced with CCLc-MNDU3-huCD19 to express human CD19 on their surface (CD19-K562). Clones were selected after sorting with Automated Cell Deposition Unit for high-level uniform CD19 expression and proliferation rate to match the parental K562 cells.

Primary human cells

Collection of anonymous human cord blood units from the delivery rooms at UCLA Ronald Reagan Medical Center and use of human peripheral blood cells were deemed exempt from need for formal approval by the Institutional Review Board at UCLA. Human CD34-positive cells were isolated from fresh umbilical cord blood using immunomagnetic beads (MACS CD34 MicroBead Cell Separation Kit; Miltenyi, Auburn, CA) and stored in liquid nitrogen. Isolation efficiency was always above 70% for CD34 positivity. Thawed human CD34-positive cells were prestimulated for 14 hr in 5% CO2 at 37°C in X-Vivo15 medium (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) enriched with recombinant human (rhu)SCF (50 ng/ml), rhuFlt-3 ligand (50 ng/ml), and rhuThrombopoietin (50 ng/ml; transduction medium; cytokines from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Transduction was performed for 24 hr with addition of lentiviral vectors at a concentration of 5.5×107 TU/ml onto 105 cells in 1 ml of transduction medium in wells coated with recombinant human fibronectin fragment RetroNectin (Takara, Otsu, Japan).

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were obtained from anonymous donor blood samples (UCLA CFAR Virology Core Laboratory) and isolated using gradient centrifugation on Ficoll-Hypaque. T-lymphocytes were activated with Dynabeads T-activator CD3/CD28 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in R10 in 72 hr incubation in 5% CO2 at 37°C. Cells were then washed during magnetic bead removal, and immediately used for lentiviral transduction in R10 at 5.5×107 TU/ml onto 5×105 cells. Medium-term cultures of T-cells were carried in R10 with rhuIL-2 (10 ng/ml; R&D Systems) for a minimum of 7 days before the functional experiments.

Differentiation cultures of primary human cells

Myeloid differentiation was performed in culture for 12–15 days by incubation in 5% CO2 at 37°C in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (Mediatech) containing 10% FBS, enriched with cytokines rhuSCF (100 ng/ml) and rhuIL-3 (100 ng/ml) from day 1, with addition of either rhuG-CSF (10 ng/ml) or rhuGM-CSF (10 ng/ml) on day 3, in tissue-culture-treated six-well plates, accordingly to published protocols (Gaines and Berliner, 2005). Cells were divided and expanded every 3 days, with no cells discarded, keeping cell concentrations below 5×105/well.

NK cell differentiation was performed in coculture with nonirradiated murine stroma OP9-DL1 monolayers over 35–40 days by incubation in 5% CO2 at 37°C in Alpha-20 medium with cytokines rhuSCF (5 ng/ml), rhuFlt-3 ligand (5 ng/ml), rhuIL-7 (5 ng/ml), and rhuIL-15 (10 ng/ml) from day 1. Cells were split every 4 days, with passage through a 70 μm strainer to remove detached stromal cells, and re-plated over fresh confluent OP9-DL1 stroma, in tissue-culture-treated 12-well plates (De Smedt et al., 2007).

In vivo studies

NOD/SCID/γ chainnull (NSG) mice (NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ; stock no. 005557; Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were housed in accordance with approved protocol by the UCLA Office of Animal Research Oversight. All animals were handled in laminar flow hoods and housed in microinsulator cages in a pathogen-free colony in a biocontainment vivarium facility. Newborn pups at 3–7 days of life were injected with 3×105 cells/pup via intrahepatic injection of nonmodified or transduced human CD34-positive cells isolated from umbilical cord blood, 1 day after conditioning with 150 cGy of sublethal total body irradiation from a 137Ce source with attenuator. Transplanted pups were housed with nursing mothers and weaned to separate cages at 3 weeks. Blood samples were collected via the retro-orbital venous plexus under general anesthesia with isoflurane at 8 and 12 weeks posttransplantation to evaluate engraftment efficiency. Bone marrow, spleen, and blood were harvested from each animal 8 months posttransplantation for flow cytometric and qPCR analyses. Leukocytes were also isolated for functional studies from bone marrow and spleen of engrafted mice after hypotonic lysis of red blood cells with 0.2% NaCl solution for 30 sec. Other engrafted mice were subcutaneously injected with 1×106 CD19-positive Raji cells at 12–14 weeks of life, with follow-up with measurement of tumor development and euthanasia when the largest diameter reached 15 mm or tumor ulceration was present. Tumor volumes were calculated per the ellipsoid volume formula (π/6×L×W×H) (Tomayko and Reynolds, 1989).

Flow cytometry

For analysis of cell surface markers and CAR expression, cells were first incubated in PBS with 5% FBS at 4°C for 5 min, and then incubated with fluorescent-labeled murine monoclonal antibodies to human CD14-PE, CD33-APC, CD34-PerCP, CD56-PE, or CD3-PerCP for 20 min in the dark at 4°C. For all tests, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated polyclonal F(ab′)2 fragment goat antihuman IgG1 Fcγ (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) (Cooper et al., 2003) (55.5 ng per 105 cells) was used for the detection of the human IgG spacer in both CAR constructs on cell surface. Jurkat cells stably transduced with the CD19-CAR with expression above 96% were used as positive controls for detection of CAR expression, and PBMC were used as controls for expression of human cell surface markers. After being washed with PBS, cells were analyzed on an LSRII (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) cytometer.

Cytotoxicity assays

Assays were performed using the flow-cytometry-based nonradioactive Live/Dead Cell Mediated Cytotoxicity Kit (Invitrogen), using 5×103 targets per well labeled with 3,3′-dioctadecyloxacarbocyanine (DiOC). Target cells used included CD19-positive Raji cells, CD19-negative K562 cells, and CD19-positive K562 cells (CD19-K562). Effector cells were added at effector-to-target (E:T) ratios of 1.25:1, 2.5:1, 5:1, 10:1, 20:1, 40:1, and 80:1. Cell mixtures were incubated in tissue-culture-treated U-bottom 96-well plates in 5% CO2 at 37°C in propidium iodide (PI)-containing R10 for times described in the Results section. Nonviable targets were double-positive cells for DiOC and PI. An LSRII cytometer was used to acquire all samples, and percent lysis of targets was based upon the following equation: Percent of specific lysis=[no. of nonviable target cells in coculture with effector cells/(no. of nonviable target cells in coculture+no. of viable target cells in coculture)] – [no. of nonviable targets cultured alone/(no. of nonviable targets cultured alone+no. of viable targets cultured alone)]×100% (Kane et al., 1996). All samples were loaded in triplicate, and all assays had controls with isolated effectors and targets. rhuGM-CSF was added at the concentration of 10 ng/ml to the assay medium in some experiments.

Apoptosis induction was evaluated by using the flow-cytometry-based FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Biosciences). Effector cells were incubated in R10 with target Raji cells at an E:T ratio 10:1 in tissue-culture-treated U-bottom 96-well plates in 5% CO2 at 37°C for 6 hr. Staining with the kit reagents accordingly to instructions was followed by flow cytometry acquisition within 1 hour. Target cells were identified by costaining with an APC-labeled murine monoclonal antibody to human CD19 (BD Biosciences).

Vector copy number assessment

Genomic DNA was extracted using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA), and quantified using the Sigma-Aldrich DNA Quantification Fluorescence Assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). All assessments were obtained by qPCR using the ABI 7700 Sequence Detector (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). TaqMan primers and probes were used to detect the HIV-1 ψ region of the vector provirus (Sanburn and Cornetta, 1999) and were compared with a standard curve made with genomic DNA extracted from a cell line with a known lentiviral vector copy number diluted with genomic DNA from the parental nontransduced cell line.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assays

NK cells were harvested from culture plates, passed through a 70 μm strainer to remove stromal cells, and subjected to negative selection using the Dynabeads Untouched Human NK Cells kit (Invitrogen). Columns were washed twice to increase the recovery, and purity was assessed by flow cytometry. After the enrichment, cells were immediately used for functional assays.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assays to detect interferon gamma (IFN-γ) secretion were performed using the Human IFN-gamma ELISpot Kit (Mabtech, Mariemont, OH). All microplate wells were coated with a monoclonal anti-IFN-γ antibody provided with the kit. Then, 2×105 effector cells and 104 target cells (preirradiated with 10,000 cGy) were plated in the wells with 200 μl of R10 and incubated in 5% CO2 at 37°C for 48 hr. RhuIL-2 (R&D Systems) was added at 10 ng/ml to selected wells. After incubation, all wells were washed with PBS 0.05% Tween, and treated with a biotinylated monoclonal anti-IFN-γ antibody for 2 hr at 37°C. Subsequent treatments with streptavidin-peroxidase and chromogen were used for spot formation, and plates were read with a CTL-ImmunoSpot S5 Micro Analyzer (Shaker Heights, OH). Negative controls were isolated targets or effector cells without targets, and unmodified human PBMC were positive controls. Only large spots with light rims were considered positive, and a minimum of five spot-forming units (SFU) per well was required for a significant response. Results were reported as SFU per million of incubated effector cells.

Cell staining preparations

For microscopy staining, 0.5–1.0×105 cells were applied to slides using a cytocentrifuge (CytoSpin4; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Resulting preparations were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature (RT) and rinsed with Dulbecco's PBS (DPBS; Mediatech). Morphology preparations used standard staining with May Grunwald-Giemsa protocol (Sigma-Aldrich). Immunocytochemistry preparations started with blocking with 5% FBS in DPBS for 30 min at RT, followed by incubation with 1/200 Biotin-SP-AffiniPure F(ab′)2 Fragment Goat Anti-Human IgG, Fc-gamma fragment specific for 60 min at RT, and washed 3 times for 5 min in double-distilled water. Next, the smears were incubated in 1/500 peroxidase–streptavidin for 30 min at RT, washed 3 times for 5 min, and treated using DAB-Plus Reagent Set (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Lastly, the smears were counterstained with May Grunwald and 1/20 diluted Giemsa stain (Sigma-Aldrich), rinsed with double-distilled water, and air-dried. Images were obtained using a Nikon Eclipse TS100 inverted microscope (Nikon), and captured at 10× and 40× using a Nikon Digital Sight Fi1 digital camera system and NIS-Elements F3.0 imaging software.

Colony-forming unit assay

Human HSPCs were cultured immediately after transduction in MethoCult H4434 Classic (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC) incubated for 14 days in 5% CO2 at 37°C for the detection and quantification of HSPC. Colonies were counted and scored, and collected for genomic DNA extraction and qPCR.

Statistical analyses

Cell type, transduction status, percent of CAR expression, culture conditions, and experiment order were considered independent variables, and nonparametric one-way ANOVA was used for analysis of data to compare the different cell populations in study. Cytotoxicity assays were evaluated considering all assay replicates, using mixed linear models. Mixed effects models were constructed to control for variation in measurements day to day. Model adequacy was checked by residual analysis. Log transformations were used on the response target-killing variable when residual plots showed violations in model assumptions. Nonparametric methods were used when sample sizes were small and skewed data were both present. For the tumor challenge experiments, tumor volume was logged because of its skewed distribution. Linear mixed models were constructed to assess the relationship between (logged) tumor volume and time (in days), group, and the time×group interaction (growth rate). Kaplan–Meier curves were created to visualize survival rates of the mice between groups. Survival rates were formally tested for differences between groups using the log-rank test. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and IBM SPSS Version 19 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). p-Values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Lentiviral vectors carrying CD19-specific CAR constructs

Lentiviral vectors were produced carrying the genes encoding CD19-specific CAR that had the signaling domain from human CD3ζ alone (CD19R, first generation) (Cooper et al., 2003) or the CD3ζ domain combined with the costimulatory signaling domain from human CD28 (CD19RCD28, second generation) (Kowolik et al., 2006) (Fig. 1a). Both vectors contained the CD19-specific CAR constructs driven by the MNDU3 internal enhancer/promoter, which has been demonstrated to successfully modify HSPCs with persistent transgene expression (Halene et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2003; Giannoni et al., 2013). Normal human HSPCs were transduced with each of the vectors and then induced to differentiate in vitro along the myeloid or NK cell lineages. These mature cells were evaluated for CD19-specific immune activity.

Assessment of lentiviral vector constructs in primary human T-cells

Both vector constructs were first evaluated after transduction of primary human T-cells for transgene integration, phenotype, and function. Using a vector concentration of 5×107 TU/ml, the arithmetic means of transduction efficiencies of T-cells by CD19R and CD19RCD28 were 61.7% and 58.4%, respectively, with mean vector copy numbers of 1.86 and 1.2 copies/cell (Fig. 1b, upper panels). Cytotoxicity assays of T-cells against CD19-positive cells (Raji cells and CD19-K562 cells) documented specific targeting of CD19 at up to twice the lysis of nonspecific target cells (K562 cells), similarly by both CD19R- and CD19RCD28-transduced T-cells (Fig. 1c). These findings recapitulate those of Kowolik et al. (2006), who used the same CAR constructs delivered to human T-cells by electroporation of expression plasmids.

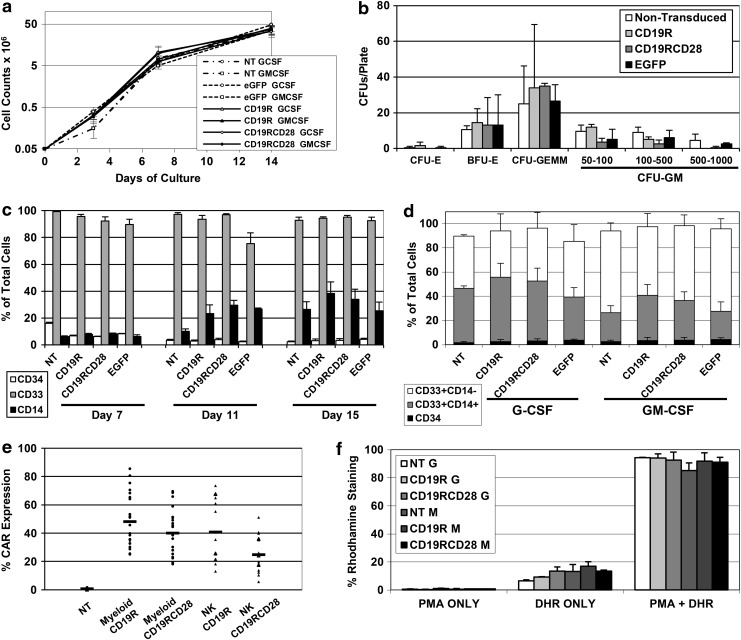

Myeloid differentiation cultures

To assess expression and activity of the CAR transgenes in the offspring of modified HSPCs, human CD34-positive cells isolated from cord blood were transduced with either one of the two anti-CD19 CAR vectors, a control EGFP vector, or mock-transduced (nontransduced cells), and cultured to undergo myeloid differentiation. To evaluate the effector activity of different CAR-bearing myeloid cell populations, the myeloid differentiation cultures were performed in the presence of rhuG-CSF or rhuGM-CSF. Cultures were started with 105 CD34-positive HSPCs, with a split into two populations on day 3 for the G-CSF- or GM-CSF-containing conditions. At the end of the 15 days required for the culture, the average numbers of cells were 40–50 million cells per condition (∼1,000-fold expansion) (Fig. 2a). There were no differences in cell numbers among nontransduced and transduced populations, or presence of either G-CSF or GM-CSF, indicating that transduction with CAR did not disturb cell growth and survival. Colony-forming unit assay of CD34-positive HSPCs transduced with both CD19-specific CARs showed no differences of proliferation or differentiation, as compared with EGFP-transduced or nontransduced cells (Fig. 2b); vector copy number analyses of colonies confirmed transduction efficiency with averages of 2.78 copies/cell for the CD19R-modified cells, 0.71 copies/cell for the CD19RCD28-modified cells, and 0.92 copies/cell for the EGFP-transduced cells.

FIG. 2.

Myeloid in vitro differentiation of modified human HSPC. (a) Cell proliferation during in vitro differentiation cultures of myeloid cells from human umbilical cord blood CD34-positive HSPCs, comparing cells differentiated in the presence of rhuG-CSF or rhuGM-CSF, nontransduced (NT) or transduced with EGFP, CD19R, or CD19RCD28 (arithmetic means of four experiments). Values in y-axis are represented in logarithmic scale. (b) Distribution of CFU counts for CFU assay with human CD34-positive HSPCs, nontransduced or transduced with lentiviral vectors carrying EGFP, CD19R, or CD19RCD28. CFU-E, CFU-erythroid (p=0.68); BFU-E, burst-forming unit-erythroid (p=0.99); CFU-GEMM, CFU-granulocyte, erythroid, macrophage, megakaryocyte (p=0.88); CFU-GM, CFU-granulocyte, macrophage, 50–100 cell colonies (p=0.21), 100–500 cell colonies (p=0.28), 500–1,000 cell colonies (p=0.12). Error bars represent means of triplicates+SD. (c) Expression of human cell surface makers CD34 (white columns) (p=0.1166), CD33 (gray columns) (p=0.4936), and CD14 (black columns) (p=0.1741) on in vitro-differentiated myeloid cells, nontransduced (NT) or transduced with CD19R, CD19RCD28, or EGFP, distributed by day of culture. Values represent arithmetic means of results from three experiments and error bars represent mean+SEM. (d) Expression of human cell surface markers on in vitro-differentiated myeloid cells, nontransduced (NT) or transduced with CD19R, CD19RCD28, or EGFP, distributed by culture conditions in rhuG-CSF and rhuGM-CSF and vector transduction, defined as CD34-positive (black columns) (p=0.2479), CD33-positive/CD14-positive (gray columns) (p=0.0059), and CD33-positive/CD14-negative (white columns) (p=0.02). Values represent arithmetic means of results from three experiments and error bars represent mean+SEM. (e) Expression of CAR in myeloid (black circles) and NK cells (black triangles) differentiated in vitro from human CD34-positive HSPCs, nontransduced (NT) or transduced with CD19R or CD19RCD28 (n=18). (f) Dihydrorhodamine 123 assay of myeloid cells differentiated in vitro with or without stimulation with phorbol myristate acetate, distributed by culture conditions in G-CSF (G) and GM-CSF (GM) and vector transduction (p=0.8634). Values represent arithmetic means of results from three experiments and error bars represent mean+SEM. CFU, colony-forming unit; HSPC, hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells; NK, natural killer.

The immunophenotype of the differentiated cells assessed by flow cytometry demonstrated that the early myeloid marker CD33 was expressed by more than 85% of the cultured cells (Fig. 2c). CD14 was assessed as a marker of monocyte populations in myeloid differentiation cultures. At days 11 and 15, the CAR-transduced myeloid cells had similar CD14 and CD33 expression as compared with nontransduced cells (Fig. 2c). CD33-positive/CD14-positive cell populations were found at higher frequencies in G-CSF-cultured myeloid cells (Fig. 2d), but no differences were noted among nontransduced and transduced cells.

Transduction efficiencies of the HSPCs by the CAR vectors were assessed in myeloid differentiation cultures on day 15 by flow cytometry using commercially available FITC-conjugated polyclonal F(ab′)2 fragment goat antihuman IgG1 Fcγ for detection of the IgG spacer component of both CAR constructs (Cooper et al., 2003) (Figs. 2e and 3g) and by qPCR measurement of vector proviral DNA sequences (Fig. 1b, lower panels). Arithmetic means of CAR expression were 48.1% for CD19R-transduced (range 25–85.5%) and 40.1% for CD19RCD28-transduced cells (range 18.1–69.6%). Vector copy number analysis by qPCR showed a mean of 2.1 vector copies/cell (range 1.7–2.5) for the CD19R-transduced cells and a mean of 1.1 vector copies/cell (range 0.7–1.5) for the CD19RCD28-transduced cells.

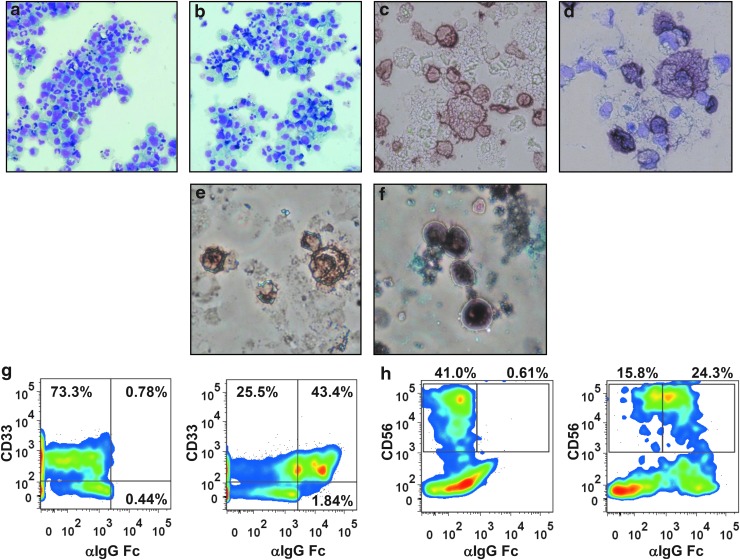

FIG. 3.

Cytospin preparations and flow cytometry analyses of in vitro-differentiated myeloid and NK cells. Cytospin of myeloid cells differentiated in vitro in the presence of (a) rhuG-CSF or (b) rhuGM-CSF, May-Grunwald Giemsa staining (Nikon Eclipse TS100 inverted microscope, 10×, Nikon Digital Sight Fi1 camera). Peroxidase immunocytochemistry staining of in vitro-differentiated myeloid cells using F(ab′)2 fragment goat antihuman IgG, Fc-gamma fragment specific, (c) without counterstaining and (d) counterstained with May Grunwald dye (Nikon Eclipse TS100 inverted microscope, 40×, Nikon Digital Sight Fi1 camera). Peroxidase immunocytochemistry staining of in vitro-differentiated NK cells using F(ab′)2 fragment goat antihuman IgG, Fc-gamma fragment specific, (e) without counterstaining and (f) counterstained with May-Grunwald dye (Nikon Eclipse TS100 inverted microscope, 40×, Nikon Digital Sight Fi1 camera). (g) Flow cytometry pseudocolor plots of representative samples of in vitro-differentiated myeloid cells stained for human cell surface marker CD33 and CD19-specific CAR (using FITC-conjugated F[ab′]2 fragment goat antihuman IgG1 Fcγ); nontransduced cells (left panel) and CD19R-transduced cells (right panel) are shown. (h) Flow cytometry pseudocolor plots of representative samples of in vitro NK cells stained for human cell surface marker CD56 and CD19-specific CAR; nontransduced cells (left panel) and CD19R-transduced cells (right panel) are shown. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate.

The dihydrorhodamine 123 assay was used to measure the respiratory burst activity of in vitro-differentiated myeloid cells, as a measure of their functional maturity. More than 95% of nontransduced and transduced cells demonstrated staining by dihydrorhodamine after stimulation with phorbol myristate acetate, irrespective of whether they were differentiated with G-CSF or GM-CSF (Fig. 2f). These findings demonstrate that the myeloid differentiation cultures gave rise to mature myeloid cells, and that transduction CAR did not affect myeloid maturation.

Morphologic aspects of differentiated cells were assessed by microscopy of cytospin preparations stained with May-Grunwald Giemsa on day 15 (Fig. 3a and b). Myeloid cells differentiated in G-CSF or GM-CSF demonstrated 10–20% of the cells with the appearance of mature neutrophils, 10–15% of monocytes, 5–10% of macrophages, and all the different stages of myeloid differentiation, with similar findings for nontransduced and transduced cells. Immunocytochemical staining of the cells with biotinylated F(ab′)2 fragment antihuman IgG Fc-gamma fragment, which recognizes the stalk portion of the CAR, followed by incubations with peroxidase–streptavidin and DAB demonstrated intense diffuse expression of the CAR protein on the membrane of the myeloid cells differentiated from transduced HSPCs (Fig. 3c and d). The microscopy of cytospin preparations confirmed the flow cytometry findings (Fig. 3g) and evidenced that CAR was uniformly expressed on the membrane of transduced cells.

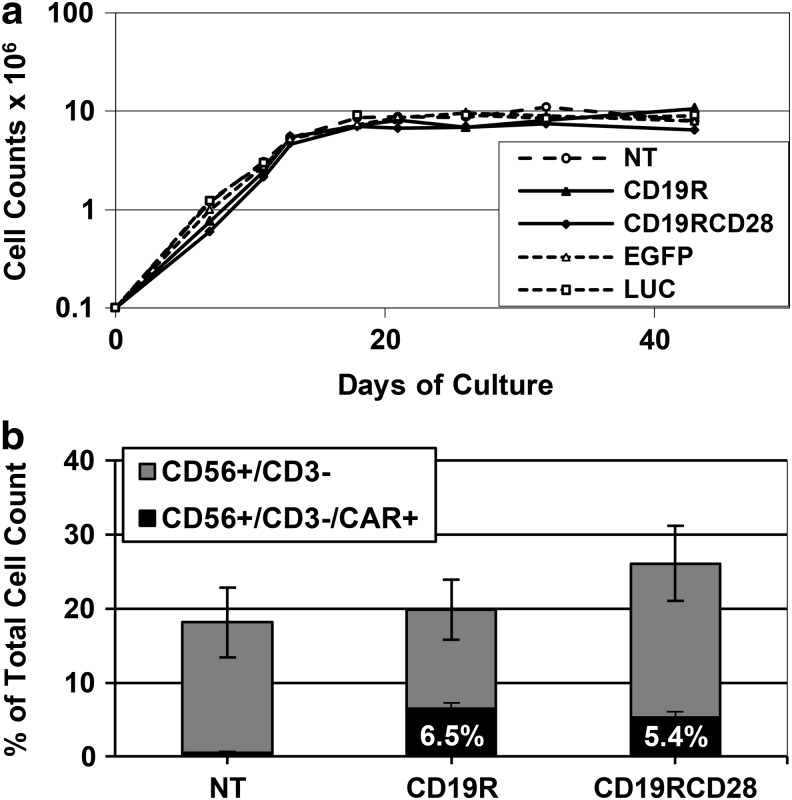

NK cell differentiation cultures

Human HSPCs were also transduced with the two CAR vectors or control vectors with EGFP or firefly luciferase and differentiated in vitro into NK cells by coculture with OP9-DL1 stromal cells in the presence of IL-7 and IL-15 (De Smedt et al., 2007). We then assessed cell proliferation, maturation, CAR expression, and CD19-specific cytotoxic function.

Total yields of cells achieved on day 40 of culture in all conditions averaged 10 million cells, with no differences in cell growth rate or yields among nontransduced and transduced populations (Fig. 4a). Morphologic analysis of cells from these cultures on microscopy showed the presence of 10–20% large mononuclear cells with large nuclei, typical of NK cell morphology, 5–10% of myeloid cells, and abundant numbers of cells with fine reticular cytoplasm and small nuclei, compatible with the murine stromal cells. Immunocytochemical staining of cells from the NK differentiation cultures demonstrated cells expressing the CAR protein in an intense diffuse pattern on the membrane of 20–40% of the cells derived from transduced HSPCs, similar to the findings on modified myeloid cells (Fig. 3e and f).

FIG. 4.

NK cell in vitro differentiation of modified human HSPCs. (a) Typical cell proliferation of in vitro-differentiated NK cells from human umbilical cord blood CD34-positive HSPCs, comparing nontransduced (NT) and cells transduced with CD19R, CD19RCD28, EGFP, or firefly luciferase (LUC). Values in y-axis are represented in logarithmic scale. (b) Expression of human surface markers CD56 and CD3, and CAR expression of in vitro-differentiated NK cells, nontransduced or transduced with CD19R or CD19RCD28, defined as CD56-positive/CD3-negative (total height of columns), CAR-negative (gray columns), and CAR-positive (black columns). Values represent arithmetic means of results from 18 experiments and error bars represent mean+SEM.

At days 35–44 of culture, between 15% and 30% of the cells displayed the immunophenotype of differentiated NK cells (CD56 positive/CD3 negative) (Figs. 3h and 4b), with no differences among nontransduced and transduced cells. Mean transduction efficiencies of all cells in culture were 40.6% for CD19R and 24.8% for CD19RCD28, assayed by flow cytometry (Fig. 2e). When we consider only CD56-positive/CD3-negative cells, an average of 32% carried CD19R and 20.5% carried CD19RCD28 (Fig. 4b). CAR-expressing CD56-positive/CD3-negative NK cells comprised an average of 10% of the total cells in the cultures. Vector copy number analysis showed a mean of 4.6 copies/cell (range 3.1–5.8) for CD19R and 2.3 copies/cell (range 1.6–3.1) for CD19RCD28 on the nonenriched cell populations from differentiation cultures.

Cytotoxicity assays with in vitro-differentiated myeloid cells

Assessment of CD19-specific killing by CAR-expressing myeloid cells was performed by cytotoxicity assays against Raji cells, a CD19-positive human cell line. Myeloid cells were harvested at 14–16 days of culture, resuspended in fresh R10 for coculture with DiOC-labeled target cells at different E:T ratios, and assay plates were analyzed by flow cytometry immediately after an incubation period of 12 hr.

G-CSF-differentiated myeloid cells performed increased killing of Raji cells by populations transduced by either CARs in similar fashion, in comparison to nontransduced cells (Fig. 5a). Overall, the presence of CD19-specific CAR doubled the lytic activity against Raji cells over background. The maximum mean lytic activity of G-CSF-differentiated myeloid cells was 26% at an E:T ratio of 80:1 (Fig. 5a, left panel). GM-CSF-differentiated myeloid cells bearing either of the CARs achieved increased killing of Raji cells with similar activity (Fig. 5a, right panel). In general, GM-CSF-differentiated myeloid cells had significantly higher lytic activity (p<0.0001) against Raji cells compared with G-CSF-differentiated cells.

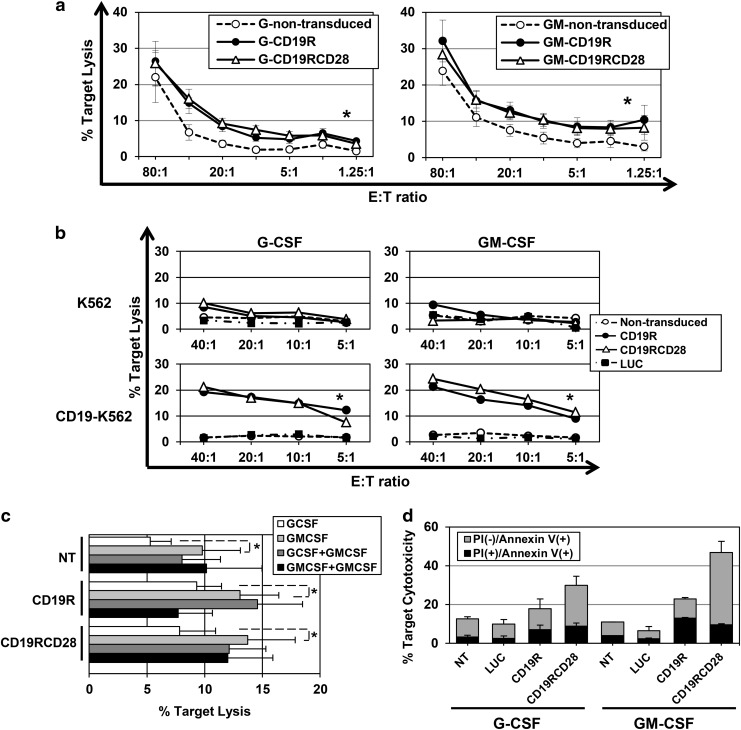

FIG. 5.

Cytotoxicity of CAR-transduced in vitro-differentiated myeloid cells. (a) Cytotoxicity against Raji cells of myeloid cells differentiated in vitro in G-CSF (left panel) or GM-CSF (right panel), nontransduced (white circles), CD19R-transduced (black circles), or CD19RCD28-transduced cells (white triangles) (p<0.0001). Values represent arithmetic means of results from 15 experiments, error bars represent mean+SEM, and asterisks indicate statistical significance. (b) Cytotoxicity against K562 (upper panels) and CD19-K562 cells (lower panels) of myeloid cells differentiated in vitro in G-CSF (left panels) or GM-CSF (right panels), nontransduced (white circles), LUC-transduced (black squares), CD19R-transduced (black circles), or CD19RCD28-transduced cells (white triangles) (p<0.0001). Values represent arithmetic means of results from four experiments, error bars represent mean+SEM, and asterisks indicate statistical significance. (c) Cytotoxicity of myeloid cells differentiated in vitro in the presence of G-CSF (white bars) or GM-CSF (light gray bars) in R10 medium assay or in R10 with addition of GM-CSF 10 ng/ml (dark gray and black gray bars, respectively) against Raji target cells at a 20:1 E:T ratio. Values represent arithmetic means of results from four experiments, error bars represent mean+SEM, and asterisks indicate statistical significance. (d) Cytotoxicity of myeloid cells differentiated in vitro in the presence of G-CSF or GM-CSF against Raji target cells at a 10:1 E:T ratio with measurement of cell lysis (PI staining) and apoptosis induction (Annexin V binding) on target cells, by nontransduced (NT) and LUC-, CD19R-, and CD19RCD28-transduced myeloid cells. Values represent arithmetic means of results from two experiments and error bars represent mean+SEM.

Assessment of CD19-specific targeting was also performed using CD19-K562 and parental K562 cells (which do not express CD19) (Fig. 5b). The differences in cytolytic activity between nontransduced and CAR-transduced cells were more pronounced with CD19-K562 than with Raji cells. There was minimal lysis of parental K562 by any of the myeloid populations and less than 10% lysis of CD19-K562 cells by nontransduced or cells transduced with either CAR or luciferase, demonstrating no increased nonspecific target lysis. In contrast, there was clearly increased lysis of CD19-K562 by either CD19-specific CAR-transduced populations.

Even though CAR-modified myeloid cells presented significantly higher killing of CD19-positive target cells, it was observed that nontransduced cells at high E:T ratios also presented some degree of killing, especially when differentiated in the presence of GM-CSF. This is probably because of the previously described GM-CSF-induced neutrophil priming (Swain et al., 2002; Seely et al., 2003). This hypothesis is supported by the findings that the presence of GM-CSF in the cytotoxicity medium assay induced statistically significant higher nonspecific killing of cell targets by in vitro-differentiated myeloid cells, CAR-modified or not (Fig. 5c).

Apoptosis induction in target cells by in vitro-differentiated myeloid cells was evaluated by FITC-Annexin V staining, in order to further appreciate the CAR-mediated cytotoxicity (Fig. 5d). Nonmodified, luciferase- and CAR-transduced effector cells were incubated with Raji target cells for 6 hr, and then stained with FITC-Annexin V and antihuman CD19 in the presence of PI. Higher levels of Annexin V binding to target cells were detected with incubation with CAR-modified myeloid cells, and the levels found for incubation with nonmodified and luciferase-transduced effector cells were equivalent, in both myeloid differentiation conditions. Similar to the findings with the detection of target cell lysis, cells differentiated in the presence of GM-CSF seem to present higher levels of antigen-induced cytotoxicity. The results of the Annexin V staining assays provide further evidence of the antigen-specific targeting determined by CAR-modified cells and suggest that isolated detection of target cell lysis may not document the full magnitude of the CAR-mediated cytotoxicity by myeloid cells. Higher levels of target apoptosis induction were found at incubation with CD19RCD28-modified cells than with CD19R-transduced cells.

Cytotoxicity assays with in vitro-differentiated NK cells

In vitro-differentiated NK cells were harvested and resuspended in fresh R10 for incubation of 4–6 hr with DiOC-labeled targets, following similar protocols to myeloid cells.

The CD19-negative K562 human cell line is a highly sensitive target for mature NK cells as it lacks MHC expression that inhibits NK-mediated lysis. All different in vitro-differentiated NK populations presented K562 lysis, with averages of 19.9%, 24.9%, and 31.8% by nontransduced, CD19R-transduced, and CD19RCD28-transduced cells, respectively, at a 20:1 E:T ratio, demonstrating that transduction with either generations of CARs did not impair maturation or function of NK cells.

Analysis of lysis of Raji cells showed that NK cells expressing CD19-specific CAR had higher lytic activity, as compared with nontransduced cells. CD19RCD28-transduced NK cells consistently showed increased lysis of Raji targets compared with CD19R-transduced NK cells (Fig. 6a). CD19-K562 cells were lysed at slightly higher rates than parental K562, with CD19RCD28-transduced NK cells possessing the highest levels (Fig. 6b).

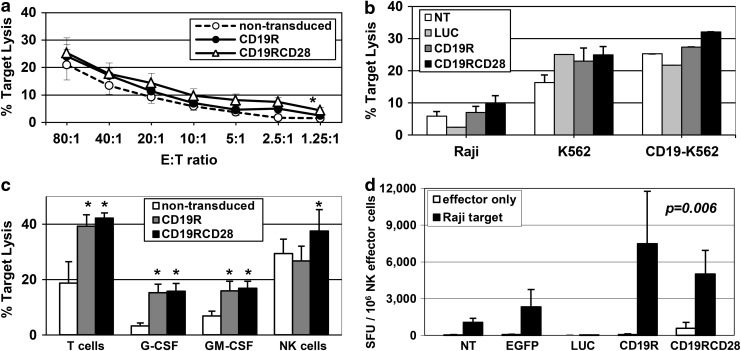

FIG. 6.

Cytotoxicity and target-specific activation of CAR-transduced in vitro-differentiated NK cells. (a) Cytotoxicity of in vitro-differentiated NK cells against Raji cells (p<0.0001), nontransduced (white circles), CD19R-transduced (black circles), or CD19RCD28-transduced NK cells (white triangles). Values represent arithmetic means of results from 18 experiments, error bars represent mean+SEM, and asterisks indicate statistical significance. (b) Cytotoxicity against Raji (p=0.0035), K562 (p=0.0035), and CD19-K562 cells of in vitro-differentiated NK cells, nontransduced (NT, white columns), luciferase-transduced (LUC, light gray), CD19R-transduced (dark gray), or CD19RCD28-transduced (black columns) at a 10:1 E:T ratio. Values represent arithmetic means of results from four experiments and error bars represent mean+SEM. (c) Cytotoxicity of primary T-cells (p<0.0001) and in vitro-differentiated myeloid cells (p<0.0001) and NK cells (p=0.02), nontransduced (white columns) or transduced with CD19R (gray columns) or CD19RCD28 (black columns) against Raji cells at a 20:1 E:T ratio, adjusted by percentage of mature cells (NK cells) and CD19-specific CAR expression (T-cells and myeloid cells). Values represent arithmetic means of results from 18 experiments, error bars represent mean+SEM, and asterisks indicate statistical significance. (d) IFN-γ ELISPOT assay of in vitro-differentiated NK cells, nontransduced (NT) and transduced with EGFP, firefly luciferase (LUC), CD19R, or CD19RCD28, against Raji cells (p=0.006). Values represent arithmetic means of results from four experiments and error bars represent mean+SEM.

Cytolytic assays adjusted for absolute frequencies of CAR-positive effector cells

To better appreciate the killing activity of the different effectors, target lysis data were adjusted for the percentages of CAR-modified cells for primary T-cells and in vitro-differentiated myeloid cells. Data for Raji targets at a corrected 20:1 E:T ratio are shown (Fig. 6c). Because in vitro NK differentiation has low efficiency, E:T ratios were adjusted to the percentage of mature NK cells.

The adjusted cytotoxicity values confirm the CD19-specific targeting by T-cells and by in vitro-differentiated myeloid cells expressing either CD19R or CD19RCD28 (Fig. 6c), with no difference between the two CAR generations. For NK cells, higher target lysis is evident only with CD19RCD28-expressing cells (37.5%); lysis of Raji cells by first-generation CD19R-expressing NK cells was similar to the results with nontransduced cells (26.7% and 29.3%, respectively). Comparisons among the different effector cells showed highest antigen-specific lysis by T-cells, with NK cells in second and myeloid cells last. Nonspecific target lysis by nontransduced cells was highest by NK cells, and minimal with myeloid cells (Fig. 6c).

Activation of in vitro-differentiated NK cells by CD19-positive targets

To confirm the CD19-specific activation of CAR-expressing NK cells, ELISPOT assays were performed to detect secretion of IFN-γ by differentiated NK cells in coculture with Raji targets. For these assays, differentiated cells were enriched for NK cells using negative selection, with assay samples averaging 32.6% of CD56-positive/CD3-negative cells and 57.6% of CAR expression.

Responses in the IFN-γ ELISPOT assay were based on enumeration of spot-forming cells adjusted to the number of mature NK cells present in each sample (Fig. 6d). All NK cell populations incubated without targets had SFU values similar to incubation of nontransduced or EGFP- or LUC-transduced cells against Raji targets, below 2,316 SFU/106 effector cells. Incubation of CAR-transduced cells with Raji presented significantly higher mean SFUs, above 5,020 SFU/106 effector cells, showing specific activation of CAR-modified NK cells by CD19-positive targets. The highest value was 7,495 SFU/106 effector cells by CD19R-transduced cells against Raji targets. Addition of rhuIL-2 to the cultures during the assay nonspecifically raised IFN-γ release from all samples, obscuring CAR-specific effects (data not shown).

In vivo studies in humanized NSG

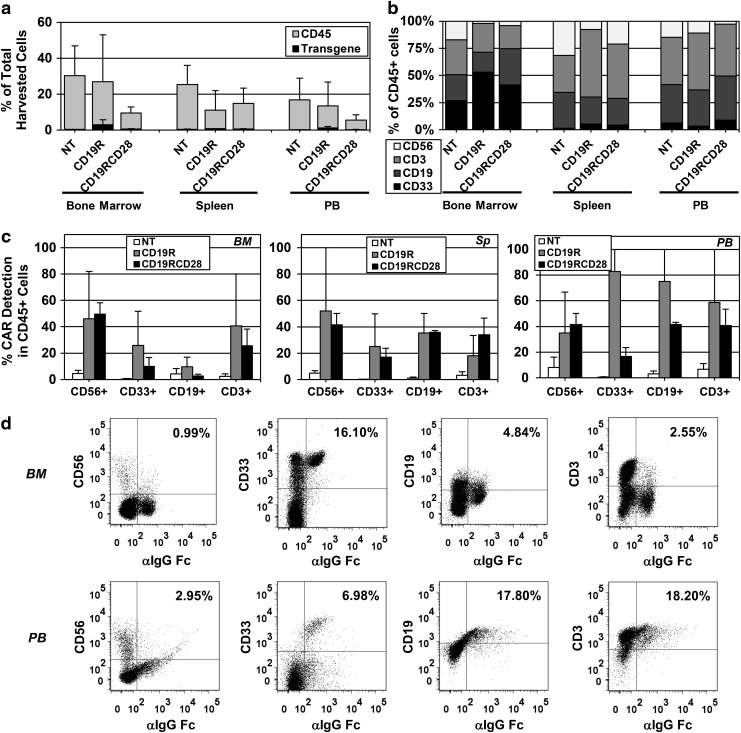

In vivo assessment of the engraftment, proliferation, and differentiation of modified human HSPCs was performed by the intrahepatic injection of nonmodified and CAR-transduced human HSPCs into sublethally irradiated NSG pups. Long-term human hematopoiesis in transplanted mice was analyzed through harvest of bone marrow, spleen, and peripheral blood at 32 weeks posttransplant (Fig. 7a–d). Human engraftment in all three compartments (as detected by the percentage of human CD45-positive cells) was variable in the different groups, but there was no statistical difference between nontransduced and CAR-transduced arms. CAR-modified cells were detected in the whole cell populations harvested from bone marrows (mean 5.55% and range 0.5–10.6 for CD19R; mean 1.87% and range 0.5–5.4 for CD19RCD28), spleens (mean 1.1% and range 0.1–2.1 for CD19R; mean 1.7% and range 0.1–6.1 for CD19RCD28), and peripheral blood (mean 2.65% and range 0.1–5.3 for CD19R; mean 2.2% and range 0.1–5.6 for CD19RCD28) of NSG engrafted with CAR-modified HSPCs (Fig. 7a, c, and d). Different hematopoietic lineages were successfully detected in all arms bearing the human cell surface markers CD33, CD3, CD56, and CD19, with CAR-positive cells present in all lineages (Fig. 7b–d). Mean vector copy number of cells harvested from engrafted mice was 0.79 copies/cell (range 0.27–1.13) for CD19R and 0.71 copies/cell (range 0.02–1.79) for CD19RCD28.

FIG. 7.

Engraftment of CAR-transduced human HSPCs in humanized NSG mice. (a) Human engraftment (detected by the percentage of human CD45-positive cells) and CAR-positive cells shown as percentage of total harvested cells from bone marrows, spleens, and PB from humanized NSG mice 32 weeks postintrahepatic injection into pups. Mice were engrafted with nontransduced human HSPCs (NT) or CAR-transduced human HSPCs (CD19R or CD19RCD28). Values represent arithmetic means of results from three experiments with 2–7 mice per group and error bars represent mean+SEM. (b) Distribution of different human hematopoietic lineages in humanized mice, myeloid cells (CD33+), B-lymphocytes (CD19+), T-lymphocytes (CD3+), and NK cells (CD56+), represented as percentages of total human CD45-positive cells harvested from bone marrows, spleens, and PB from humanized NSG mice 32 weeks postintrahepatic injection into pups. (c) Distribution of CAR-positive cells by different human hematopoietic lineages in humanized mice, NK cells (CD56+), myeloid cells (CD33+), B-lymphocytes (CD19+), and T-lymphocytes (CD3+), represented as percentages of total human CD45-positive cells harvested from bone marrows (BM), spleens (Sp), and PB from humanized NSG mice 32 weeks postintrahepatic injection into pups of nontransduced human HSPCs (NT) or CAR-transduced human HSPCs (CD19R or CD19RCD28). Values represent arithmetic means of results from three experiments and error bars represent mean+SEM. (d) Representative flow cytometry dot plots of BM and PB of a humanized mouse injected with CD19R-modified human HSPCs. Human cell surface markers CD56, CD33, CD19, and CD3 were plotted against CAR expression detected by FITC-conjugated F(ab′)2 fragment goat antihuman IgG1 Fcγ. NSG, NOD/SCID/γ chainnull; PB, peripheral blood.

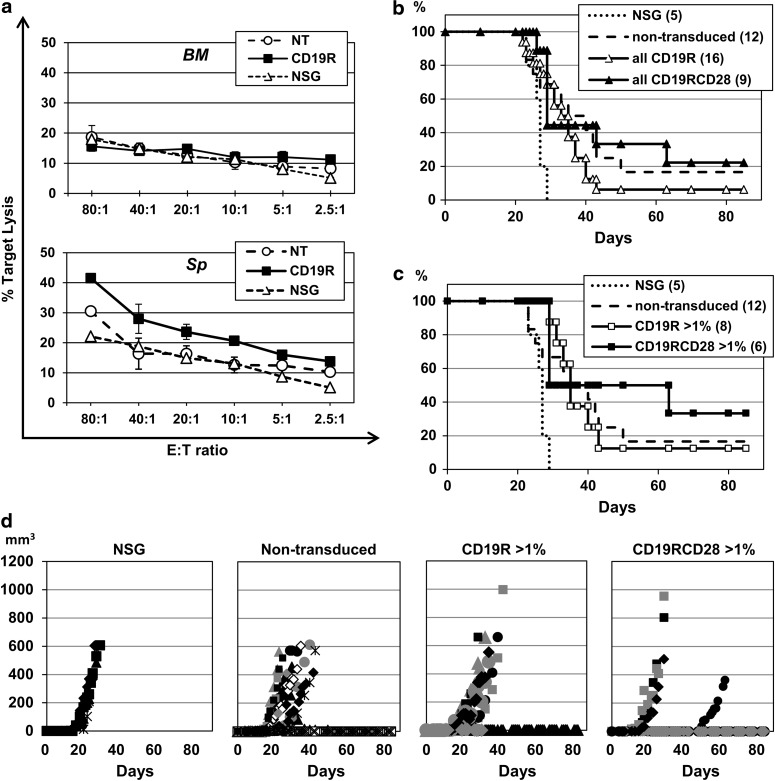

Total leukocytes isolated from bone marrows and spleens of NSG (nonhumanized, nontransduced, and CD19R-transduced HSPCs) were incubated without any particular enrichment in ex vivo cytotoxicity assays against target Raji cells in ascending E:T ratios. Bone marrow cells did not present differences in Raji cell lysis among nonhumanized NSG, nontransduced humanized NSG, and CD19R-transduced humanized NSG mice, with maximum lysis of less than 20% at an 80:1 E:T ratio (Fig. 8a, upper panel). Spleen cells from CD19R-modified humanized NSG presented higher Raji cell lysis at all E:T ratios, well above the levels by nonhumanized NSG and nontransduced humanized NSG, with maximum lysis of 41.5% at an 80:1 E:T ratio (Fig. 8a, lower panel). These results confirm antigen-specific cytotoxicity by CD19R-modified mature cells present in the spleens of the humanized mice.

FIG. 8.

Antigen-dependent cytotoxicity targeting CD19 in the humanized NSG mouse model. (a) Leukocytes were harvested from bone marrows (BM) and spleens (Sp) from humanized NSG mice 32 weeks postintrahepatic injection into pups of nontransduced human HSPCs (NT) or CD19R-transduced human HSPCs, and assayed against Raji target cells at different E:T ratios. Leukocytes from nonhumanized NSG (NSG) were used as controls. Values represent arithmetic means of results from two experiments and error bars represent mean+SEM. (b) Kaplan–Meier estimates in days of time to euthanasia of study mice in the different arms: nonhumanized (NSG), humanized NSG engrafted with nontransduced human HSPCs (nontransduced), humanized NSG engrafted with CD19R-transduced human HSPCs (CD19R), and humanized NSG engrafted with CD19RCD28-transduced human HSPCs (CD19RCD28). Numbers of study mice per group are shown in parentheses. (c) Kaplan–Meier estimates in days of time to euthanasia of study mice in the different arms, including only mice with more than 1% of humanization of leukocytes on the peripheral blood (as detected by flow cytometry) in the humanized arms. Numbers of study mice per group are shown in parentheses. (d) Diagrams of the development along time in days of tumor volumes of subcutaneous injection of 1×106 CD19-positive Raji cells in study mice groups shown in (c).

Tumor challenge experiments with subcutaneous injection of CD19-positive Raji cells were performed with other experimental mice, comparing nonhumanized NSG (NSG arm), humanized NSG engrafted with nontransduced human HSPCs (nontransduced arm), humanized NSG engrafted with CD19R-transduced human HSPCs (CD19R), and humanized NSG engrafted with CD19RCD28-transduced human HSPCs (CD19RCD28). Injected mice were followed with measurements of tumor volume development, and euthanasia was performed when the largest diameter reached 15 mm or tumor ulceration was present, and Kaplan–Meier estimates of time in days to euthanasia were elaborated for all arms (Fig. 8b and c). Surviving mice were found on all humanized arms, as opposed to nonhumanized NSG (log-rank p-value 0.018). Mice in the CD19RCD28 arm had the best survival curve (Fig. 8b), specifically the mice with more than 1% of human cells detected in the peripheral blood (Fig. 8c), although statistical significance was not reached because of the small number of study mice. Tumor volume measurements (Fig. 8d) also demonstrated favorable trend for the mice in the CD19RCD28 arm and virtually no benefit of transduction with first-generation CD19R over the nontransduced arm.

Discussion

HSCT is a standard medical procedure in the care of high-risk patients with CD19-positive hematological malignancies, using HSPCs of autologous or allogeneic sources depending on the diagnosis, in an attempt to develop immune response against cancer. The treatment protocols include a chemotherapy conditioning regimen, with or without radiation, that has the dual purpose of destruction of residual cancer cells and preparation of the bone marrow environment to allow engraftment of infused HSPCs. Introduction of genes encoding anti-CD19 CAR into HSPCs may allow rapid and sustained production of target-specific effector cells of multiple leukocyte lineages, enhancing the graft-versus-malignancy activity (Tran et al., 1995; Hege et al., 1996; Roberts et al., 1998; Biglari et al., 2006; Esser et al., 2012). Furthermore, the introduction of CAR-modified HSPCs in the HSCT context would favor effective immune response against minimal residual malignancy, favor the engraftment of modified cells, and decrease the probability of immunogenicity of the CAR constructs on the surface of effector cells. Transduced HSPCs will yield granulocytes and monocytes within 1–2 weeks, followed by production of NK cells in a few months and T-lymphocytes potentially over a longer time-course (Rappeport et al., 2011; Vatakis et al., 2011; Kitchen et al., 2012; Giannoni et al., 2013). CAR expression by these cells may confer enduring antileukemic immunity with a continuously generated mix of effector cell types, as opposed to current cancer immunotherapy approach using modified mature T-lymphocytes.

To assess the potential to modify human HSPCs with CAR, we performed in vitro studies of human CD34-positive cells transduced with lentiviral vectors carrying genes for a CAR recognizing the CD19 antigen. These HSPCs were differentiated in cytokine-driven culture systems to produce myeloid or NK cells that may function as target-specific cytolytic cells. Two different CD19-specific CAR constructs were used: first-generation CAR containing only the CD3ζ cytoplasmic domain as signal transduction moiety (CD19R), and second-generation CAR containing the CD3ζ signaling domain and the CD28 costimulatory domain (CD19RCD28). It is known that second-generation CARs are more efficient than first-generation constructs for target-specific activation of modified T-cells in vitro and in vivo, but little is known about CAR activation of myeloid and NK cells produced from modified HSPCs.

In vitro myeloid differentiation was driven by either G-CSF or GM-CSF, yielding mixed populations of CAR-expressing myeloid cells, including monocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages. In vitro differentiation of HSPC to NK cells on OP9-DL1 stroma with IL-15 resulted in cell populations with a small percentage of CD56-positive/CD3-negative NK cells (18–25%), with 5.5–6.5% expressing the CAR. In vitro differentiation of modified HSPC to T-cells was not performed, as the resulting cells are not fully mature and may lack effector function. In vivo experiments using humanized NOS/SCID/γc−/− (NSG) mice as xenograft recipients demonstrated that CAR-transduced HSPCs were able to produce multilineage CAR-modified cells detected in bone marrows, spleens, and peripheral blood of engrafted mice.

Differentiated cells from modified HSPCs not only displayed morphologic features of maturity documented by microscopy, immunocytochemistry, and flow cytometry, but also acquired mature functions. Myeloid cells produced in vitro from CD34-positive cells in G-CSF or GM-CSF had normal oxidative respiratory burst activity as assessed by the dihydrorhodamine assay. NK cells produced from CD34-positive cells displayed active killing of K562 cells, which are susceptible to NK-mediated cytolysis, and CAR-bearing NK cells showed CD19-specific activation on the IFN-γ ELISPOT.

GM-CSF-differentiated myeloid cells had significantly higher cytotoxicity, both nonspecific and antigen specific, than G-CSF-differentiated myeloid cells. The high nonspecific background cytolytic activity is most likely because of activation of the cells by the culture conditions, with GM-CSF having greater priming effects (Swain et al., 2002; Seely et al., 2003) on the cells. Cytotoxicity of nontransduced NK cells differentiated in vitro was high against all cell targets and not antigen dependent. Nonetheless, the myeloid and NK cells produced in vitro and expressing the CAR consistently showed CD19-specific effector activity above the background, in both cytotoxicity and antigen-specific IFN-γ ELISPOT assays. This effect was seen with both CD19-positive Raji and CD19-K562 targets. Thus, despite the limitations from the activated state of the effector cells produced in vitro, the potential for producing non-T-cell effector cells expressing CAR specifically mediating antigen-specific reactivity from transduced HSPCs was demonstrated. These results corroborate previously published evidence of activation by CAR of effector cells other than T-cells (Tran et al., 1995; Hege et al., 1996; Roberts et al., 1998; Biglari et al., 2006; Esser et al., 2012).

NSG pups transplanted with CAR-modified human HSPCs presented differentiated CAR-bearing cells in bone marrow, spleen, and peripheral blood. Ex vivo total leukocytes harvested from spleens of NSG engrafted with CD19R-transduced human HSPCs demonstrated antigen-specific cytotoxicity, documenting that CAR-modified human HSPCs gave rise to functional CAR-modified cells that specifically targeted CD19 antigen. CD19R-modified bone marrow cells may have failed to present higher levels of Raji cell lysis because of cell immaturity or presence of lower percentages of T-cell and NK cell populations. In vivo challenge of engrafted humanized NSG with subcutaneous injection of CD19-positive Raji cells demonstrated that there is inhibition of tumor development and suggest potential survival advantage of mice engrafted with HSPCs modified with second-generation CD19-specific CARs with CD28 costimulation.

The CD19RCD28 vector was consistently made at lower titers than the CD19R vector and had lower efficiency for transduction of CD34-positive HSPCs (measured by viral copy number analysis and flow cytometry) despite adjustments to match the multiplicity of infection of the two vectors. Neither of the CARs used in this study had detectable effects on HSPC proliferation and/or differentiation, compared with nontransduced cells. In myeloid cells differentiated from HSPC transduced with either of the CARs, there was similar specific targeting of CD19-positive cells. In NK cells differentiated from CAR-modified HSPCs, only the second-generation CAR (CD19RCD28) achieved specific responses to CD19-positive cells, with CD19R-transduced cells performing similar to nontransduced cells. These findings are in accordance with previous descriptions that second-generation CARs containing CD28 domains (Kruschinski et al., 2008; Pegram et al., 2008) [or other costimulatory molecules (Altvater et al., 2009)] conferred enhanced cell activation and specific lysis of CD19-positive targets by transduced peripheral blood NK cells (Walker et al., 1999; Kruschinski et al., 2008; Pegram et al., 2008; Altvater et al., 2009).

There is concern that the presence of CAR in HSPCs and their progeny cells could activate effector cells in an antigen-independent manner, creating a nonspecific and potentially detrimental pathway for cellular damage (Hombach et al., 2010). Full assessment of specific functional activity was limited by properties of the cells produced in vitro, which are produced by culture with pharmacologic levels of cytokines. In vivo, these cells would be produced by natural hematopoiesis and therefore would not be expected to be hyperactive. Current clinical trials use constructs similar to the ones used in this study for modification of mature T-lymphocytes, and no clinical signs of chronic T-cell activation were detected beyond the tumor lysis syndrome caused by tumor burden reduction. Our results suggest that the presence of CAR does not affect in vivo HSPC function and production of target-specific effectors. While the long-term production of CAR-expressing effectors is attractive as a method to achieve persistent antileukemic immunity, regulatory elements could be included in the transgene vector construct, such as miRNA or condition-specific promoters to allow CAR expression only in specific cell state, such as T-cell activation events, only when the cells infiltrate tumor tissues or in the presence of a specific cytokine milieu. In the situation of mixed chimerism, the presence of gene-modified cells could be terminated in vivo if needed by inclusion of a suicide gene in the vector and administration of the appropriate pro-drug. Further in vivo studies are needed to evaluate the biology and function of the different subpopulations of CAR-modified leukocytes produced. Effects on the cellular progeny need to be assessed, such as nonspecific cell activation, tissue homing, and development of immunological memory. Animals engrafted with high levels of CAR-modified HSPCs should be evaluated regarding the limitations of the antileukemic activity, simulating clinical scenarios.

The data presented in this study support the concept that modification of HSPCs with CAR is feasible, does not impair differentiation, and leads to antigen-specific effector cells of multiple lineages. These results provide the initial steps for the advancement of this concept to clinical trials of immunotherapy of leukemias and lymphomas using transplantation of CAR-modified HPSCs.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Broad Stem Cell Research Center Flow Cytometry Core, the UCLA CFAR Virology Core Laboratory, and the UCLA Immuno/BioSpot Core for technical assistance. Support was provided by the UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Grants UL1RR033176 and UL1TR000124, UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, Hyundai Hope on Wheels Research Grant Award, and St. Baldrick's Foundation Scholar Career Development Award #180637 to S.N.O.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Altvater B. Landmeier S. Pscherer S., et al. 2B4 (CD244) signaling by recombinant antigen-specific chimeric receptors costimulates natural killer cell activation to leukemia and neuroblastoma cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:4857–4866. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biglari A. Southgate T.D. Fairbairn L.J. Gilham D.E. Human monocytes expressing a CEA-specific chimeric CD64 receptor specifically target CEA-expressing tumour cells in vitro and in vivo. Gene Ther. 2006;13:602–610. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartier N. Hacein-Bey-Abina S. Bartholomae C.C., et al. Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy with a lentiviral vector in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Science. 2009;326:818–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1171242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper L.J. Topp M.S. Serrano L.M., et al. T-cell clones can be rendered specific for CD19: toward the selective augmentation of the graft-versus-B-lineage leukemia effect. Blood. 2003;101:1637–1644. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper A.R. Patel S. Senadheera S., et al. Highly efficient large-scale lentiviral vector concentration by tandem tangential flow filtration. J. Virol. Methods. 2011;177:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croxtall J.D. Rituximab: as first-line maintenance therapy following rituximab-containing therapy for follicular lymphoma. Drugs. 2011;71:885–895. doi: 10.2165/11206720-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smedt M. Taghon T. Van de Walle I., et al. Notch signaling induces cytoplasmic CD3ɛ expression in human differentiating NK cells. Blood. 2007;110:2696–2703. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-082206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doering C.B. Archer D. Spencer H.T. Delivery of nucleic acid therapeutics by genetically engineered hematopoietic stem cells. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2010;62:1204–1212. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertl H.C. Zaia J. Rosenberg S.A., et al. Considerations for the clinical application of chimeric antigen receptor T cells: observations from a recombinant DNA Advisory Committee Symposium held June 15, 2010. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3175–3181. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esser R. Muller T. Stefes D., et al. NK cells engineered to express a GD(2)-specific antigen receptor display built-in ADCC-like activity against tumor cells of neuroectodermal origin. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2012;16:569–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01343.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaines P. Berliner N. Differentiation and characterization of myeloid cells. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 2005;Chapter 22 doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im22f05s67. Unit 22F.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar H.B. Cooray S. Gilmour K.C., et al. Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy for adenosine deaminase-deficient severe combined immunodeficiency leads to long-term immunological recovery and metabolic correction. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3:97ra80. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannoni F. Hardee C.L. Wherley J., et al. Allelic exclusion and peripheral reconstitution by TCR transgenic T cells arising from transduced human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Mol. Ther. 2013;21:1044–1054. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halene S. Wang L. Cooper R.M., et al. Improved expression in hematopoietic and lymphoid cells in mice after transplantation of bone marrow transduced with a modified retroviral vector. Blood. 1999;94:3349–3357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hege K.M. Cooke K.S. Finer M.H., et al. Systemic T cell-independent tumor immunity after transplantation of universal receptor-modified bone marrow into SCID mice. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:2261–2269. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hombach A. Hombach A.A. Abken H. Adoptive immunotherapy with genetically engineered T cells: modification of the IgG1 Fc ‘spacer’ domain in the extracellular moiety of chimeric antigen receptors avoids ‘off-target’ activation and unintended initiation of an innate immune response. Gene Ther. 2010;17:1206–1213. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane K.L. Ashton F.A. Schmitz J.L. Folds J.D. Determination of natural killer cell function by flow cytometry. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 1996;3:295–300. doi: 10.1128/cdli.3.3.295-300.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitchen S.G. Levin B.R. Bristol G., et al. In vivo suppression of HIV by antigen specific T cells derived from engineered hematopoietic stem cells. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002649. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer J.N. Wilson W.H. Janik J.E., et al. Eradication of B-lineage cells and regression of lymphoma in a patient treated with autologous T cells genetically engineered to recognize CD19. Blood. 2010;116:4099–4102. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-281931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn D.B. Candotti F. Gene therapy fulfilling its promise. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:518–521. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0809614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn D.B. Dotti G. Brentjens R., et al. CARs on track in the clinic. Mol. Ther. 2011;19:432–438. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn D.B. Pai S.Y. Sadelain M. Gene therapy through autologous transplantation of gene-modified hematopoietic stem cells. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:S64–S69. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowolik C.M. Topp M.S. Gonzalez S., et al. CD28 costimulation provided through a CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor enhances in vivo persistence and antitumor efficacy of adoptively transferred T cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10995–11004. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruschinski A. Moosmann A. Poschke I., et al. Engineering antigen-specific primary human NK cells against HER-2 positive carcinomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:17481–17486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804788105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesterhuis W.J. Haanen J.B. Punt C.J. Cancer immunotherapy—revisited. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2011;10:591–600. doi: 10.1038/nrd3500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naldini L. Blomer U. Gallay P., et al. In vivo gene delivery and stable transduction of nondividing cells by a lentiviral vector. Science. 1996;272:263–267. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegram H.J. Jackson J.T. Smyth M.J., et al. Adoptive transfer of gene-modified primary NK cells can specifically inhibit tumor progression in vivo. J. Immunol. 2008;181:3449–3455. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter D.L. Levine B.L. Kalos M., et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in chronic lymphoid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:725–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappeport J.M. O'Reilly R.J. Kapoor N. Parkman R. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for severe combined immune deficiency or what the children have taught us. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 2011;25:17–30. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts M.R. Cooke K.S. Tran A.C., et al. Antigen-specific cytolysis by neutrophils and NK cells expressing chimeric immune receptors bearing zeta or gamma signaling domains. J. Immunol. 1998;161:375–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanburn N. Cornetta K. Rapid titer determination using quantitative real-time PCR. Gene Ther. 1999;6:1340–1345. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savoldo B. Ramos C.A. Liu E., et al. CD28 costimulation improves expansion and persistence of chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in lymphoma patients. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:1822–1826. doi: 10.1172/JCI46110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seely A.J. Pascual J.L. Christou N.V. Science review: cell membrane expression (connectivity) regulates neutrophil delivery, function and clearance. Crit. Care. 2003;7:291–307. doi: 10.1186/cc1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain S.D. Rohn T.T. Quinn M.T. Neutrophil priming in host defense: role of oxidants as priming agents. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2002;4:69–83. doi: 10.1089/152308602753625870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomayko M.M. Reynolds C.P. Determination of subcutaneous tumor size in athymic (nude) mice. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1989;24:148–154. doi: 10.1007/BF00300234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran A.C. Zhang D. Byrn R. Robert M.R. Chimeric zeta-receptors direct human natural killer (NK) effector function to permit killing of NK-resistant tumor cells and HIV-infected T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 1995;155:1000–1009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uckun F.M. Jaszcz W. Ambrus J.L., et al. Detailed studies on expression and function of CD19 surface determinant by using B43 monoclonal antibody and the clinical potential of anti-CD19 immunotoxins. Blood. 1988;71:13–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vatakis D.N. Koya R.C. Nixon C.C., et al. Antitumor activity from antigen-specific CD8 T cells generated in vivo from genetically engineered human hematopoietic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:E1408–E1416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115050108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker W. Aste-Amezaga M. Kastelein R.A., et al. IL-18 and CD28 use distinct molecular mechanisms to enhance NK cell production of IL-12-induced IFN-gamma. J. Immunol. 1999;162:5894–5901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. Rosol M. Ge S., et al. Dynamic tracking of human hematopoietic stem cell engraftment using in vivo bioluminescence imaging. Blood. 2003;102:3478–3482. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarour H.M. Ferrone S. Cancer immunotherapy: progress and challenges in the clinical setting. Eur. J. Immunol. 2011;41:1510–1515. doi: 10.1002/eji.201190035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zufferey R. Nagy D. Mandel R., et al. Multiply attenuated lentiviral vector achieves efficient gene delivery in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 1997;15:871–875. doi: 10.1038/nbt0997-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]