Abstract

Older women have higher phosphorus levels than men. Estradiol causes phosphaturia in rodents. Whether sex hormones associate with phosphorus levels in humans is unknown. In 1,346 community-living older men, we evaluate the cross-sectional association of sex hormones with serum phosphorus, using linear regression with serum phosphorus levels as the dependent variable. Mean age was 76 years, phosphorus was 3.2±0.4mg/dl, and 18% had moderate kidney disease. Each 10pg/ml higher total estradiol associated with 0.05mg/dL lower serum phosphorus levels (95 % CI −0.09 to −0.02; P < 0.01) in a model adjusted for age, race, testosterone, sex hormone binding globulin, calcium, eGFR, intact PTH, 25(OH) vitamin D, body mineral density, and alkaline phosphatase. Results were similar in individuals with or without CKD. Serum testosterone levels were also associated with lower serum phosphorus levels (β per 200ng/dL greater total testosterone = −0.08; 95% CI −0.13 to −0.04; P < 0.001). Results were confirmed in an independent sample of 2,555 older men, and associations were not attenuated when adjusted for fibroblast growth factor-23 levels. Estradiol may induce phosphaturia in humans. Future studies are required to elucidate potential effects of testosterone on phosphorus homeostasis.

Keywords: Phosphorus, estradiol, testosterone, menopause, sex hormones, kidney disease, cardiovascular disease

Introduction

Higher serum phosphorus levels are associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) and all-cause mortality, independent of traditional CVD risk factors in community-living populations;(1-3) associations that are evident even for serum phosphorus levels within the normal range, and among persons with normal kidney function.(1-3) Phosphorus induces vascular smooth muscle cells to calcify in-vitro,(4) and higher serum levels are associated with arterial calcification(5) and stiffness(6) in the general population. Thus, insights into determinants of serum phosphorus on a population scale may identify new pathways contributing to CVD. Yet, most demographic, dietary, and traditional CVD risk factors are not strongly associated with serum phosphorus levels.(7) Known determinants such as severe chronic kidney disease (CKD) and primary hyperparathyroidism are relatively rare on a population-level. Thus, determinants of serum phosphorus in community-living populations remain largely unknown.

Across prior studies conducted among community-living populations, women of postmenopausal age consistently have serum phosphorus levels that are 0.15-0.30mg/dL higher than similarly aged men.(1, 3, 6-9) Treatment of parathyroidectomized and ovariectomized rats with estradiol results in declines in serum phosphorus levels and increases in urinary phosphorus loss.(10) We hypothesized that estradiol might regulate renal phosphorus excretion in men, and that sex hormones may account for differences in serum phosphorus between older men and women. Studying this question in a cohort of older men avoids the confounding influences of endogenous changes in estradiol through the menopausal transition and effects of post-menopausal hormone therapy (HT). To that end, we evaluate the cross-sectional association of sex hormone concentrations with serum phosphorus levels among community-living older men who participated in the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOs) study.

Results

Among the 1,346 study participants from the United States MrOs Study (MrOs US), the mean age was 74 ± 6 years and 91% were white. The mean total estradiol level was 22.6 ± 8.6 pg/ml, mean total testosterone level was 406.8 ± 171.1 ng/dl, mean serum phosphorus level was 3.2 ± 0.4 mg/dL, and mean estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was 76 ± 18 ml/minute/1.73 m2. Two hundred thirty-eight subjects (18%) had eGFR < 60 ml/minute/1.73 m2, and 8 (0.6%) had eGFR < 30 ml/minute/1.73 m2. Participants with higher serum phosphorus levels were more likely to have diabetes mellitus, higher serum calcium, and lower intact parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels. Men with higher phosphorus levels also had lower total estradiol and testosterone levels (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of MrOs US Participants by Serum Phosphorus Levels.

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 3.00 (n=524) |

3.00 - 3.50 (n=549) |

3.51-4.00 (n=231) |

> 4.00 (n=42) |

||

| Demographics | |||||

| Age (years) ± SD | 73 ± 6 | 74 ± 6 | 74 ± 6 | 74 ± 7 | 0.48 |

| Caucasian % (n) | 90% (474) | 90% (495) | 94% (218) | 86% (36) | 0.15 |

| Medical History | |||||

| Diabetes mellitus % (n) | 12% (63) | 15% (80) | 23% (52) | 38% (16) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension % (n) | 42% (221) | 46% (252) | 43% (99) | 59% (25) | 0.13 |

| Smoking % (n) | 0.67 | ||||

| Current | 3% (17) | 4% (23) | 3% (7) | 2% (1) | |

| Former | 59% (307) | 59% (322) | 63% (146) | 69% (29) | |

| Dietary Intake | |||||

| Calcium (mg) ± SD | 805 ± 396 | 808 ± 389 | 783 ± 352 | 732 ± 381 | 0.56 |

| Phosphorus (mg) ± SD | 1156 ± 454 | 1162 ± 479 | 1138 ± 455 | 1098 ± 478 | 0.79 |

| Calories (kcal) ± SD | 1642 ± 653 | 1626 ± 642 | 1620 ±v633 | 1572 ± 642 | 0.90 |

| Fat servings ± SD | 1.5 ± 1.3 | 1.5 ± 1.2 | 1.4 ± 1.1 | 1.4 ± 1.4 | 0.73 |

| Physical Exam Measurements | |||||

| BMI (kg/m2)* | 26.5 (24.7, 29.0) | 27.1 (24.8, 29.4) | 27.3 (25.2, 30.0) | 27.9 (24.6, 31.6) | 0.09 |

| Whole body BMD (g/cm2) ± SD | 1.16 ± 0.12 | 1.17 ± 0.13 | 1.17 ± 1.13 | 1.17 ± 0.14 | 0.78 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) * | 138 (127, 149) | 138 (125, 150) | 137 (124, 148) | 139 (123, 153) | 0.57 |

| Blood Measurements | |||||

| Total estradiol (pg/ml) ± SD | 23.9 ± 8.8 | 22.6 ± 8.1 | 20.4 ± 8.3 | 18.7 ± 8.7 | < 0.001 |

| Total testosterone (ng/dl) ± SD | 430 ± 177 | 409 ± 165 | 363 ± 165 | 316 ± 135 | < 0.001 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2) * | 75 (65, 84) | 74 (65, 84) | 74 (65, 85) | 72 (54, 84) | 0.09 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) ± SD | 9.3 ± 0.4 | 9.3 ± 0.4 | 9.4 ± 0.4 | 9.5 ± 0.4 | < 0.01 |

| 25 (OH) Vitamin D (ng/ml) ± SD | 26 ± 8 | 25 ± 8 | 24 ± 8 | 26 ± 8 | 0.22 |

| Intact PTH (pg/ml)* | 32 (25, 40) | 29 (23, 37) | 28 (23, 37) | 26 (20, 33) | < 0.001 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L)* | 71 (61, 87) | 71 (59, 87) | 72 (57, 88) | 75 (63, 97) | 0.36 |

| Albumin (g/dl) ± SD | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 0.58 |

Median (Interquartile range)

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index, BMD = bone mineral density, eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate, and PTH = parathyroid hormone.

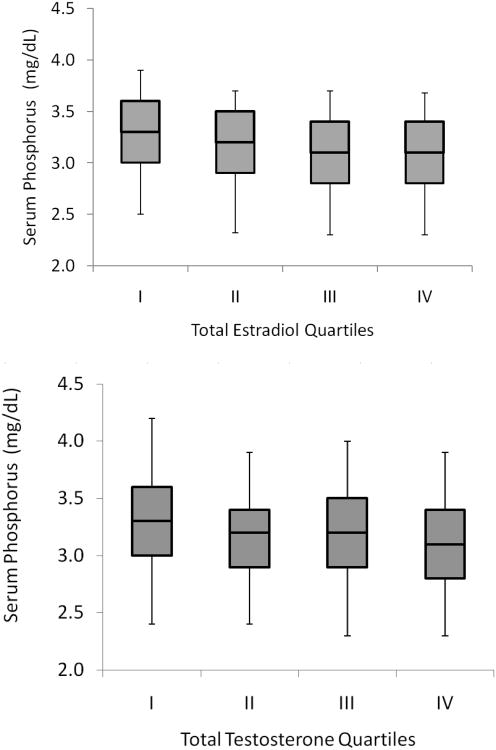

Total estradiol levels were inversely correlated with serum phosphorus in unadjusted analysis (r= −0.17, P< 0.001; Figure 1), In a model adjusted for age and race (Table 2, Model 1) each 10 pg/ml higher total estradiol level was associated with a 0.088 mg/dL lower serum phosphorus level. With additional adjustment for testosterone (Model 2) and sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) (Model 3), about one third of this association was attenuated, but despite this, total estradiol remained significantly associated with lower phosphorus levels. Further adjustment for serum calcium levels, eGFR, intact PTH, and 25 (OH) vitamin D levels had little effect on the association (Model 4), nor did adjustment for alkaline phosphatase and whole body BMD, such that in the final adjusted model, each 10 pg/ml higher total estradiol level was associated with a 0.053 mg/dL lower serum phosphorus level (Model 5). Results were similar when bioavailable estradiol levels were evaluated in place of total estradiol (Table 2). Results were also similar among participants with or without CKD (defined as an eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2). Each 10 pg/ml higher total estradiol was associated with a 0.060 mg/dL lower serum phosphorus level in persons without CKD (95% CI −0.097 to −0.022), and 0.038mg/dL lower serum phosphorus level in persons with CKD (95% CI −0.119 to 0.043).

Figure 1. Distribution of Serum Phosphorus Levels by Quartiles of Estradiol and Testosterone in Older Men (MrOs US).

Line within boxes shows median level, borders of boxes reflect the 25th and 27th percentile of the distribution, and border of error bars reflect the 10th and 90th percentile of the distribution. Total estradiol quartiles (in pg/ml) were < 17.2 for quartile 1, 17.2-21.6 for quartile 2, 21.7-27.0 for quartile 3, and > 27.0 for quartile 4. Total testosterone quartiles (in ng/dl) were < 300 for quartile 1, 300-387 for quartile 2, 388-488 for quartile 3, and > 448 for quartile 4.

Table 2. Association of Estradiol Levels with Serum Phosphorus Levels in MrOs US.

| Total Estradiol (per 10 pg/ml greater) | Bioavailable Estradiol (per 5 pg/ml greater) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| β | 95% CI | P-value | β | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Unadjusted | -0.089 | -0.115 to -0.062 | < 0.001 | -0.060 | -0.080 to -0.040 | < 0.001 |

| Model 1 | -0.088 | -0.115 to -0.061 | <0.001 | -0.059 | -0.080 to -0.038 | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | -0.058 | -0.091 to -0.025 | 0.001 | -0.031 | -0.056 to -0.006 | 0.014 |

| Model 3 | -0.050 | -0.083 to -0.016 | 0.004 | ** | ||

| Model 4 | -0.050 | -0.082 to -0.016 | 0.004 | -0.033 | -0.057 to -0.009 | 0.008 |

| Model 5 | -0.053 | -0.086 to -0.019 | 0.002 | -0.035 | -0.060 to -0.011 | 0.005 |

Model 1: Adjusted for age, race.

Model 2: Adjusted for Model 1 variables plus total testosterone in total estradiol model, or bioavailable testosterone in the bioavailable estradiol model.

Model 3: Adjusted for Model 2 variables plus sex hormone binding globulin

Model 4: Adjusted for Model 3 variables plus calcium, eGFR, intact PTH, and 25-OH vitamin D

Model 5: Adjusted for Model 4 variables plus alkaline phosphatase and whole body BMD.

Model excluded as sex hormone binding globulin levels are used in the calculation of bioavailable sex hormone levels.

Testosterone is the primary precursor of estradiol in men, and we observed some attenuation of the association of estradiol with serum phosphorus when the model was adjusted for testosterone levels. Therefore, we explored further the association of serum total testosterone with serum phosphorus. In unadjusted analysis, total testosterone was inversely correlated with serum phosphorus levels (-0.16, P< 0.001; Figure 1). In age and race adjusted models, each 200 ng/dl higher total testosterone level was associated with 0.086 mg/dL lower serum phosphorus levels (Table 3, Model 1). Additional adjustment for estradiol weakened, but did not abolish this association (Model 2). However when SHBG levels were included in models, the association for testosterone was returned to a magnitude similar to the unadjusted model (Model 3). Further adjustment for serum calcium, eGFR, intact PTH, and 25 (OH) vitamin D had little effect on the testosterone association (Model 4), nor did adjustment for alkaline phosphatase and whole body BMD (Model 5).

Table 3. Association of Testosterone Levels with Serum Phosphorus Levels in MrOs US.

| Total Testosterone (per 200 ng/dl greater) | Bioavailable Testosterone (per 100 ng/dl greater) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| β | 95% CI | P-value | β | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Unadjusted | -0.087 | -0.113 to -0.060 | < 0.001 | -0.102 | -0.132 to -0.072 | < 0.001 |

| Model 1 | -0.086 | -0.113 to -0.059 | < 0.001 | -0.102 | -0.133 to -0.072 | < 0.001 |

| Model 2 | -0.052 | -0.085 to -0.019 | 0.002 | -0.078 | -0.114 to -0.042 | < 0.001 |

| Model 3 | -0.081 | -0.122 to -0.041 | < 0.001 | ** | ||

| Model 4 | -0.088 | -0.129 to -0.048 | < 0.001 | -0.083 | -0.119 to -0.048 | < 0.001 |

| Model 5 | -0.084 | -0.125 to -0.043 | < 0.001 | -0.080 | -0.115 to -0.044 | < 0.001 |

Model 1: Adjusted for age, race.

Model 2: Adjusted for Model 1 variables plus total estradiol in the total testosterone model, or bioavailable estradiol in the bioavailable testosterone model.

Model 3: Adjusted for Model 2 variables plus sex hormone binding globulin

Model 4: Adjusted for Model 3 variables plus calcium, eGFR, intact PTH, and 25-OH vitamin D

Model 5: Adjusted for Model 4 variables plus alkaline phosphatase and whole body BMD.

Model excluded as sex hormone binding globulin levels are used in the calculation of bioavailable sex hormone levels

To provide a comparison of the relative strength of associations of various factors associated with serum phosphorus, we compared the beta coefficients per SD increment for each continuous measure in our multivariable model. In age and race adjusted models, the strength of association of estradiol with serum phosphorus was approximately the same as that of testosterone and natural log transformed intact PTH, and approximately twice as strong of that of serum calcium and eGFR (Table 4).

Table 4. Age and Race Adjusted Comparative Strength of Associations of Continuous Variables (Per SD Greater in Each) with Serum Phosphorus Levels in MrOs US.

| β | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total estradiol (per 8.6 pg/ml greater) | -0.076 | -0.098 to -0.052 | <0.001 |

| Bioavailable estradiol (per 5.5 pg/ml greater) | -0.065 | -0.088 to -0.042 | <0.001 |

| Total testosterone (per 171.6 ng/dl greater) | -0.074 | -0.097 to -0.051 | <0.001 |

| Bioavailable testosterone (per 76.2 ng/dl greater) | -0.078 | -0.101 to -0.055 | < 0.001 |

| Intact PTH (per 0.4 Ln greater [pg/ml]) | -0.068 | -0.091 to -0.044 | <0.001 |

| Serum calcium (per 0.4 mg/dl greater) | 0.040 | 0.017 to 0.063 | 0.001 |

| eGFR (per 18.1 ml/min/1.73 m2 greater) | -0.033 | -0.057 to -0.009 | 0.007 |

| 25(OH) vitamin D (per 8.0 ng/ml greater) | -0.017 | -0.041 to 0.007 | 0.15 |

| Dietary phosphorus (per 464.8 mg/day greater) | -0.005 | -0.028 to 0.018 | 0.68 |

| Dietary calories (per 643.7 kcal/day greater) | -0.006 | -0.030 to 0.017 | 0.61 |

| Dietary fat (per 1.2 servings/day greater) | -0.002 | -0.026 to 0.021 | 0.85 |

Fibroblast growth factor-23 is a novel phosphaturic hormone, and may be influenced by estradiol. Therefore, to investigate whether these results were reproducible in an independent sample, and to determine whether adjustment for fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-23 levels may attenuate the associations, we repeated our main analysis in MrOs Sweden; a sister cohort to MrOs US with similar enrollment criteria and available measurements, plus availability of FGF-23 concentrations. The mean age of the 2,555 MrOs Sweden participants was 76 ± 3 years, mean total estradiol was 21 ± 8 pg/ml, mean total testosterone was 450 ± 190 ng/dL, mean serum phosphorus was 3.3 ± 0.5 mg/dL, and mean eGFR was 72 ± 20 ml/min/1.73 m2 (697 [27%] had eGFR < 60). FGF-23 levels were right-skewed with a median level of 44 pg/ml (interquartile range 33-58pg/ml). Other MrOs Sweden participant characteristics have been described in detail elsewhere.(11) The adjusted associations of estradiol and testosterone levels with serum phosphorus levels in MrOs Sweden were in the same direction and of similar strength to those in MrOs US. Further adjustment for FGF-23 levels did not materially alter the sex hormone – serum phosphorus associations (Table 5).

Table 5. Associations of Sex Hormones with Serum Phosphorus and Effect of FGF-23 Adjustment in MrOs Sweden.

| Total Estradiol (per 10pg/ml greater) | Total Testosterone (per 200 ng/dl greater) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Predictor Variable | β | 95% CI | P-value | β | 95% CI | P-value |

| Adjusted* Association | -0.079 | -0.110 to -0.049 | < 0.001 | -0.049 | -0.078 to -0.021 | < 0.001 |

| Adjusted* Association plus FGF-23 | -0.080 | -0.110 to -0.049 | < 0.001 | -0.047 | -0.076 to -0.019 | 0.001 |

Adjusted for age, city, sex hormone binding globulin, eGFR, calcium, intact PTH, and 25 (OH) vitamin D. The Estradiol model was additionally adjusted for total testosterone, and conversely the testosterone model was additionally adjusted for total estradiol.

Discussion

We demonstrate that higher serum estradiol and testosterone levels are each independently associated with lower serum phosphorus levels in community-living older men. These associations were reproducible in an independent cohort of older men in Sweden and were not explained by one another, SHBG levels, kidney function, intact PTH, 25 (OH) vitamin D, or FGF-23 levels. In conjunction with prior reports, this study suggests that estradiol may have phosphaturic properties in humans. Less is known about the effects of testosterone on phosphorus homeostasis. The inverse correlation of testosterone and phosphorus levels reported here may reflect enhanced deposition of phosphorus into bone, reduced bone resorption, or previously unrecognized effects on gastrointestinal absorption or renal excretion of phosphorus.

Correlates of phosphorus levels in the general population were recently evaluated in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III).(7) Dietary variables, 25 (OH) vitamin D levels, and kidney function were not strongly associated with serum phosphorus levels, and most of the variance in serum phosphorus remained unexplained, so determinants of serum phosphorus remain largely unknown. Notably, women had serum phosphorus levels that were 0.16 mg/dL higher on average than men in NHANES III;(7) a finding reported consistently in other community-living populations.(1, 3, 6-9)

The renal regulation of phosphorus is principally achieved through the sodium phosphate co-transporter type IIa (NaPi-IIa) in the proximal convoluted tubule.(12-14) Recently, Faroqui and colleagues reported that treatment of parathyroidectomized and ovariectomized rats with estradiol decreased NaPi-IIa mRNA and protein levels, resulting in lower serum phosphorus levels and enhanced urinary phosphorus loss.(10) To our knowledge, no previous study has evaluated the association of endogenous serum estradiol and phosphorus levels in humans, but existing studies support a similar effect. In an observational study among over 4,500 community-living Italians with a wide age spectrum, men had a modest and linear decrease in serum phosphorus level with advancing age. Women followed a similar trajectory until age 45-54, when there was an abrupt increase in serum phosphorus levels and commensurate decrease in urinary phosphorus loss, perhaps resulting from decreased endogenous estradiol during the menopausal transition.(8) In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, women taking HT had significantly lower serum phosphorus levels compared to women not taking HT.(9) Observational studies and small randomized clinical trials have evaluated urine phosphorus excretion with HT therapy. HT treatment resulted in lower serum phosphorus levels and greater phosphaturia compared to pre-treatment levels or to the placebo arm, respectively.(15-18) Although estradiol has skeletal and other non-renal effects that could affect phosphorus homeostasis, and because the inverse correlation of estradiol and phosphorus was essentially unaltered with adjustment for alkaline phosphatase and BMD, our leading hypothesis is that the association reported here resulted primarily from estradiol increasing urinary phosphorus excretion among older men.

While evidence provided here and elsewhere support the hypothesis that estradiol decreases NaPi-IIa mRNA and protein levels, and induces phosphaturia, the mechanism(s) remains uncertain. Estrogen receptors are expressed in the proximal tubule of the rat kidney,(19) so a direct effect is possible. The majority of the estrogen response is mediated through two estrogen receptors (ER), ERα and ERβ. In rats, Faroqui and colleagues observed decreased NaPi-IIa levels and phosphaturia in response to estradiol in vivo, however this effect was not blunted with a specific inhibitor of ERα No change in klotho levels (a key co-factor for FGF-23 binding) was observed with estradiol therapy in this study.(10) Using a 7/8 nephrectomy CKD model in rats, Carrillo-Lopez et. al. recently demonstrated that estradiol increased serum FGF-23 levels in vivo, and increased FGF-23 mRNA and protein levels in a rat-derived osteoblast cell line in vitro.(20) Because FGF-23 decreases NaPi-IIa levels in the proximal tubule and induces phosphaturia,(21) this finding suggests that estradiol may induce phosphaturia indirectly, through up-regulation of FGF-23. In our study, among the subset of 2,555 Swedish MrOs participants, statistical adjustment for FGF-23 levels did not materially alter the associations of estradiol or testosterone with serum phosphorus, arguing against this hypothesis. Our observational study cannot definitively elucidate the biological pathways responsible for these associations. Possibilities that a direct effect of estradiol may be mediated through ERβ or other estrogen ligands have not yet been investigated, to our knowledge.

Studies evaluating testosterone on renal phosphorus homeostasis are sparse, conflicting, and often confounded by concomitant changes in estradiol. Ralston and colleagues evaluated treatment with estradiol versus estradiol plus testosterone for 6 months in 32 young surgically menopausal women. Both groups had decreases in serum phosphorus and increases in phosphaturia of similar magnitude compared to pre-treatment baseline.(22) Treatment of healthy middle-aged men with goserelin decreases both serum testosterone and estradiol, and concomitantly increases serum phosphorus levels and decreases phosphaturia.(23) In experimental animals, some have reported effects in the opposite direction to those observed here. Orchiectomized male rats demonstrate lower serum phosphorus levels compared to non-orchiectomized controls, and testosterone treatment restored serum phosphorus levels.(24) Several possibilities may account for the inverse correlation between total testosterone with serum phosphorus levels in our study. First, while adjustment for whole body BMD had little effect on the association in our study, testosterone increases bone formation and reduces bone resorption, which might affect serum phosphorus. Second, testosterone is the predominant precursor of estradiol in men.(25, 26) However, it appears unlikely that the association of testosterone with serum phosphorus is mediated through estradiol because statistical adjustment for estradiol had little effect on the association of testosterone with phosphorus in both the MrOs US and MrOs Sweden cohorts. Last, it remains possible that testosterone may have unrecognized effects on renal or gastrointestinal phosphorus metabolism.

Prior studies consistently demonstrate phosphorus levels that are approximately 0.15 to 0.30 mg/dL higher in older women compared to similar aged men.(1, 3, 6-9) Here, we report that each 10 pg/ml higher estradiol and 200 ng/dl higher testosterone were independently associated with lower serum phosphorus levels, (approximately 0.05 mg/dL and 0.08mg/dL, respectively in MrOs US) in men. While the clinical significance of this effect size may appear, interpretation requires recognition that older men have serum estradiol levels that are approximately four fold higher (∼15 pg/ml greater), and serum testosterone levels that are approximately 20-fold higher (∼285 ng/dl) than post-menopausal women.(27) Based on the strengths of the observed associations, differences in estradiol would be expected to account for approximately 0.09 mg/dL higher serum phosphorus level, and differences in testosterone would account for an additional 0.12 mg/dL higher phosphorus level in women compared to men. Collectively, this magnitude of difference in serum phosphorus compares favorably to differences in phosphorus levels between men and women reported in prior studies. Future studies of both sexes and concurrent measures of estradiol, testosterone, serum and urine phosphorus levels are required to determine whether differences in sex hormones account for the sex differences in serum phosphorus levels.

Strengths of this study include its relatively large sample size, community-living and geographically diverse setting, and availability of demographic, laboratory, and BMD measurements in all participants. The similar design and measurements in MrOs Sweden allowed us to test reproducibility and evaluate potential mediation through FGF-23. All phosphorus measurements were made in fasting morning specimens, decreasing influences of diurnal variation. However, the study also has important limitations. We lacked urinary phosphorus measurements, participants were all older, most were Caucasian, and few had CKD. Results may differ in younger persons, other race-ethnicities or in moderate to advanced CKD. The cross-sectional study design did not allow evaluation of temporality.

We conclude that higher serum estradiol levels and testosterone levels are each independently associated with lower serum phosphorus levels in community-living older men. These associations were not attenuated with adjustment for FGF-23 levels. In the context of prior studies, these data suggest that estradiol may directly or indirectly induce phosphaturia in humans. The mechanism responsible for the association of testosterone with serum phosphorus is less certain, but may reflect either bone or previously unrecognized renal or gastrointestinal effects, or conversion to estradiol. Future studies should evaluate whether differences in sex hormones may explain higher phosphorus level consistently observed in older women compared to men.

Materials and Methods

Study Participants

MrOs US

The primary analysis for this study evaluated participants in the United States MrOs study; an observational cohort study designed to evaluate risk factors for fractures in older men.(28, 29) Between March 2000 and April 2002, 5,995 men aged ≥ 65 years were recruited from Birmingham, Alabama; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Palo Alto, California; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Portland, Oregon; and San Diego, California. Inclusion required ability to walk without the assistance of another person; absence of bilateral hip replacements; ability to provide self-reported data and informed consent; planned residence near a field center site for the duration of the study; and absence of medical conditions judged by the investigator to result in imminent death. Institutional review boards at each center approved the study.

From the cohort, random number generators were used to select 1,602 men for measurement of sex hormones. Among these, we excluded 17 (1%) with missing serum estradiol measurement, 94 (6%) with missing serum phosphorus measurements, and 145 (9%) with missing covariate data, providing a final analytic sample of 1,346 subjects for the present analyses.

MrOs Sweden

Fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF-23) measurements were considered a key candidate mediator of the association of sex hormones with serum phosphorus, and were not available in MrOs US. Therefore, to confirm our findings in an independent cohort, and to evaluate whether FGF-23 levels attenuated the associations, we performed a secondary analysis in MrOs Sweden – a sister study to MrOs US with similar design. Study participants were recruited from 3 Swedish cities (Malmo, Goteborg, and Uppsala)., indentified using national population registers. Inclusion required male sex, age 69-80 years, and ability to walk without assistance. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Among the 3,014 Swedish MrOs participants, 375 were excluded for missing serum estradiol or testosterone measurements, 25 were excluded for missing serum phosphorus measurements, 30 were excluded for missing FGF-23 measurements, and 29 were excluded for other missing covariates, resulting in a study sample of 2,555 participants (85%) for this study.

Measurements

Sex Hormones

All blood measurements were performed on venous samples obtained after an overnight fast. Total serum estradiol and testosterone were measured using a combined tandem mass spectrometry (Taylor Technology, Princeton, NJ). The range of detection for estradiol and testosterone were 0.625 to 80 pg/ml and 25 to 3200 pg/ml, and the intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation (CV) were < 7% and <11%, respectively. SHBG was measured using an Immulite Analyzer with chemiluminescent substrate (Diagnostic Products Corp., Los Angeles, CA). The standard curve ranged from 0.2 to 180 nm/L and CVs were < 6%. All sex hormone and SHBG values were above the respective assay sensitivities. Serum albumin levels were analyzed using a Roche COBAS Integra 800 automated analyzer (Roche Diagnostics Corp., Indianapolis, IN), with a detectable range from 0.2 to 6.0 g/dL, and with CV's < 2%. These measurements were combined in the Sodergard equation to calculate bioavailable estradiol and testosterone levels.(30) Constants used in calculations were 3.14*108 L/mol for estradiol to SHBG, 4.21*104 L/mol for estradiol to albumin, 5.97*108 L/mol for testosterone to SHBG, and 4.06*104 L/mol for testosterone to albumin.(31)

In MrOs Sweden, Sex hormones were also measured by mass spectroscopy using a HP5973 quadrupole mass spectrometer as described elsewhere.(32) For total estradiol, the intraassay CV was 1.5% and interassay CV was 2.7%, and for total testosterone the interassay CV was 2.9% and interassay CV was 3.4%.

Serum Phosphorus

In MrOs US, serum phosphorus measurements were made from morning fasting blood specimens using a standard clinical automated analyzer (Roche COBAS Integra 800, Roche Diagnostics Corp. Indianapolis, IN) at a central laboratory at the University of Oregon Health Sciences Center. The range of detection was 0.3 to 20.0 mg/dL, all values were within the assay limits, and CV's were < 3%. In similar fashion, serum phosphorus measurements were made by a standard clinical chemistry analyzer in the Department of Clinical Chemistry at the Uppsala University Hospital in MrOs Sweden, as described elsewhere.(33)

Other Measurements

Standardized questionnaires provided information on participants' age, race, and history of hypertension and smoking. Prevalent diabetes was defined by fasting glucose > 126 mg/dL, use of oral hypoglycemic medications or insulin, or self-report. Dietary intake of fat, calories, calcium, and phosphorus were assessed by a modified Block Dietary Data Systems questionnaire (Block Dietary Data Systems, Berkeley, CA). Medications were recorded by trained study personnel at the baseline clinic visit, and were matched to their ingredients based on the Iowa Drug Information Service (IDIS) Drug Vocabulary (College of Pharmacy, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA).(34) Height and weight were measured with subjects wearing light clothes and no shoes, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated (weight [kg]/height [m]2). Systolic blood pressure was measured twice at the right brachial artery using a standard sphygmomanometer and an 8-megahertz Doppler probe after a 5-minute rest.

Serum calcium, creatinine, alkaline phosphatase, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), total cholesterol, and triglyceride assays were measured using a Roche COBAS Integra 800 automated analyzer, and low density lipoprotein (LDL) was calculated using the Friedewald equation.(35) eGFR was calculated using the modified 4-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation.(36, 37) 25 (OH) vitamin D2 and D3 were measured using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry, with deuterated stable isotope 25 (OH) vitamin D3 used as the internal standard. The CVs were < 5.0%, respectively. The minimum detectable limit for vitamin D2 is < 4 ng/ml and for vitamin D3 is < 2 ng/ml. The sum of vitamin D2 and D3 were used for 25 (OH) vitamin D levels in analyses. Total intact PTH was measured using the Immunoradiometric Assay 3KG600 with CVs < 8.5%.

Whole body BMD was measured using dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) (Hologic, Inc., MA). A central quality control lab, certification of DXA operators, and standardized procedures for scanning were used to insure reproducibility of DXA measurements across field-centers. The inter-clinic CVs were 0.6% for the spine and 0.9% for the hip.

Finally, in MrOs Sweden, intact FGF-23 levels were measured using ELISA according to the manufacturer's protocol (Kainos Laboratories International, Tokyo, Japan), as described elsewhere.(33, 38) The two-site ELISA has previously been shown to recognize only biologically active FGF-23, and not inactive c-terminal fragments.

Statistical Analysis

We used the MrOs US sample for the primary analysis for this study. Baseline differences in demographic and clinical variables the MrOs US sample were compared across phosphorus categories using analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables, and Chi-squared test for categorical variables. Graphical methods demonstrated an approximate Gaussian distribution for serum phosphorus levels, and a linear relationship between estradiol and phosphorus levels. We used multivariate linear regression to evaluate the association of total estradiol (per standard deviation [SD] increase) as the primary predictor variable of interest, and with serum phosphorus levels as the dependent variable. An initial model was unadjusted. Model 1 adjusted for age and race, model 2 additionally adjusted for testosterone, and model 3 additionally adjusted for SHBG. Model 4 adjusted for other variables selected a priori on the basis of our hypothesized influence serum phosphorus levels (eGFR, intact PTH, calcium, 25 (OH) vitamin D). A final model additionally adjusted for whole body BMD and serum alkaline phosphatase levels, as we hypothesized that the association of estradiol with serum phosphorus would be mediated through changes in urinary phosphorus regulation, and therefore, would remain independent of bone mineral density and markers of bone turn-over. Next, we evaluated whether results were similar in subjects with or without CKD (defined as eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73m2). These sequences of models were repeated evaluating serum total testosterone as the predictor variable of interest. In companion analyses, we also evaluated the associations of bioavailable estradiol and testosterone levels with serum phosphorus levels. Next, we compared the relative strength of association of estradiol and testosterone with serum phosphorous to the other variables used in the multivariable models. To facilitate comparison, each was evaluated as per SD change. Skewed variables were natural-log transformed.

In companion analyses, we replicated the multivariable models evaluating the association of total estradiol and testosterone with phosphorus in MrOs Sweden. Models were adjusted for model 4 variables, as described above, with 2 exceptions. All MrOs Sweden participants were Caucasian, so the race term was omitted. MrOs Sweden participants came from 3 Swedish cities, so a term for city was included to account for potential regional differences in study participant characteristics.

We used STATA version 9.2 and 10 SE (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX), and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

Sponsored by: This study was supported by a Nephrology Fellowship Stipend from Amgen Pharmaceuticals (J. Meng), the Sandra A. Daugherty Foundation Award for Cardiovascular Epidemiology (J.H. Ix) and an American Heart Association Fellowship to Faculty Transition Award (J.H. Ix). The US Osteporotic Fractures in Men (MrOs) Study is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), the Ntational Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), and the National Institutes of Health Roadmap for Medical Research under the following contracts and grants: U01 AR45580, U01 AR45615, U01 AR45632, U01 AR45647, U01 AR45654, U01 AR45583, U01 AG18197, U01 AG027810, and UL1 RR024140. The Swedish MrOs study was supported by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, the Avtal om Läkarutbildning och Forskning/Läkarutbildningsavtalet research grant in Gothenburg, the Lundberg Foundation, the Torsten and Ragnar Söderberg's Foundation, the Novo Nordisk Foundation and grants from the COMBINE consortium,

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no relationships to disclose.

References

- 1.Dhingra R, Sullivan LM, Fox CS, Wang TJ, et al. Relations of serum phosphorus and calcium levels to the incidence of cardiovascular disease in the community. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:879–885. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.9.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foley RN, Collins AJ, Ishani A, Kalra PA. Calcium-phosphate levels and cardiovascular disease in community-dwelling adults: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am Heart J. 2008;156:556–563. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tonelli M, Sacks F, Pfeffer M, Gao Z, et al. Relation between serum phosphate level and cardiovascular event rate in people with coronary disease. Circulation. 2005;112:2627–2633. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.553198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jono S, McKee MD, Murry CE, Shioi A, et al. Phosphate regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell calcification. Circ Res. 2000;87:E10–17. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.7.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foley RN, Collins AJ, Herzog CA, Ishani A, et al. Serum phosphorus levels associate with coronary atherosclerosis in young adults. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:397–404. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008020141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ix JH, De Boer IH, Peralta CA, Adeney KL, et al. Serum phosphous concentrations and arterial stiffness among persons wiht normal kidney function to moderate kidney disease in MESA. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:609–15. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04100808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Boer IH, Rue TC, Kestenbaum B. Serum phosphorus concentrations in the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:399–407. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cirillo M, Ciacci C, De Santo NG. Age, renal tubular phosphate reabsorption, and serum phosphate levels in adults. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:864–866. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0800696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onufrak SJ, Bellasi A, Cardarelli F, Vaccarino V, et al. Investigation of gender heterogeneity in the associations of serum phosphorus with incident coronary artery disease and all-cause mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:67–77. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faroqui S, Levi M, Soleimani M, Amlal H. Estrogen downregulates the proximal tubule type IIa sodium phosphate cotransporter causing phosphate wasting and hypophosphatemia. Kidney Int. 2008;73:1141–1150. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marsell R, Mirza MA, Mallmin H, Karlsson M, et al. Relation between fibroblast growth factor-23, body weight and bone mineral density in elderly men. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:1167–1173. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0780-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forster IC, Hernando N, Biber J, Murer H. Proximal tubular handling of phosphate: A molecular perspective. Kidney Int. 2006;70:1548–1559. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck L, Karaplis AC, Amizuka N, Hewson AS, et al. Targeted inactivation of Npt2 in mice leads to severe renal phosphate wasting, hypercalciuria, and skeletal abnormalities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:5372–5377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoag HM, Martel J, Gauthier C, Tenenhouse HS. Effects of Npt2 gene ablation and low-phosphate diet on renal Na(+)/phosphate cotransport and cotransporter gene expression. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:679–686. doi: 10.1172/JCI7103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adami S, Gatti D, Bertoldo F, Rossini M, et al. The effects of menopause and estrogen replacement therapy on the renal handling of calcium. Osteoporos Int. 1992;2:180–185. doi: 10.1007/BF01623924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stock JL, Coderre JA, Mallette LE. Effects of a short course of estrogen on mineral metabolism in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985;61:595–600. doi: 10.1210/jcem-61-4-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stock JL, Coderre JA, Posillico JT. Effects of estrogen on mineral metabolism in postmenopausal women as evaluated by multiple assays measuring parathyrin bioactivity. Clin Chem. 1989;35:18–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uemura H, Irahara M, Yoneda N, Yasui T, et al. Close correlation between estrogen treatment and renal phosphate reabsorption capacity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:1215–1219. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.3.6456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davidoff M, Caffier H, Schiebler TH. Steroid hormone binding receptors in the rat kidney. Histochemistry. 1980;69:39–48. doi: 10.1007/BF00508365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carrillo-Lopez N, Roman-Garcia P, Rodriguez-Rebollar A, Fernandez-Martin JL, et al. Indirect regulation of PTH by estrogens may require FGF23. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:2009–2017. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008121258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu S, Quarles LD. How fibroblast growth factor 23 works. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1637–1647. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007010068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ralston SH, Fogelman I, Leggate J, Hart DM, et al. Effect of subdermal oestrogen and oestrogen/testosterone implants on calcium and phosphorus homeostasis after oophorectomy. Maturitas. 1984;6:341–344. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(84)90006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burnett-Bowie SM, Mendoza N, Leder BZ. Effects of gonadal steroid withdrawal on serum phosphate and FGF-23 levels in men. Bone. 2007;40:913–918. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vanderschueren D, Van Herck E, Suiker AM, Visser WJ, et al. Bone and mineral metabolism in aged male rats: short and long term effects of androgen deficiency. Endocrinology. 1992;130:2906–2916. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.5.1572302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grumbach MM, Auchus RJ. Estrogen: consequences and implications of human mutations in synthesis and action. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:4677–4694. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.12.6290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones ME, Boon WC, Proietto J, Simpson ER. Of mice and men: the evolving phenotype of aromatase deficiency. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2006;17:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laughlin GA, Barrett-Connor E, May S. Sex-specific determinants of serum adiponectin in older adults: the role of endogenous sex hormones. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:457–465. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blank JB, Cawthon PM, Carrion-Petersen ML, Harper L, et al. Overview of recruitment for the osteoporotic fractures in men study (MrOS) Contemp Clin Trials. 2005;26:557–568. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orwoll E, Blank JB, Barrett-Connor E, Cauley J, et al. Design and baseline characteristics of the osteoporotic fractures in men (MrOS) study--a large observational study of the determinants of fracture in older men. Contemp Clin Trials. 2005;26:569–585. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sodergard R, Backstrom T, Shanbhag V, Carstensen H. Calculation of free and bound fractions of testosterone and estradiol-17 beta to human plasma proteins at body temperature. J Steroid Biochem. 1982;16:801–810. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(82)90038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vermeulen A, Verdonck L, Kaufman JM. A critical evaluation of simple methods for the estimation of free testosterone in serum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:3666–3672. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.10.6079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mellstrom D, Vandenput L, Mallmin H, Holmberg AH, et al. Older men with low serum estradiol and high serum SHBG have an increased risk of fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1552–1560. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marsell R, Grundberg E, Krajisnik T, Mallmin H, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-23 is associated with parathyroid hormone and renal function in a population-based cohort of elderly men. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;158:125–129. doi: 10.1530/EJE-07-0534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pahor M, Chrischilles EA, Guralnik JM, Brown SL, et al. Drug data coding and analysis in epidemiologic studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 1994;10:405–411. doi: 10.1007/BF01719664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levey AS, Greene T, Kusek JW, Beck GJ. A simplified equation to predict glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine [Abstract] J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;11:A0828. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E, Kausz AT, et al. National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:137–147. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-2-200307150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamazaki Y, Okazaki R, Shibata M, Hasegawa Y, et al. Increased circulatory level of biologically active full-length FGF-23 in patients with hypophosphatemic rickets/osteomalacia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:4957–4960. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]