Abstract

Intermediate filaments are cytoskeletal elements important for cell architecture. Recently it has been discovered that intermediate filaments are highly dynamic and that they are fundamental for organelle positioning, transport and function thus being an important regulatory component of membrane traffic. We have identified, using the yeast two-hybrid system, vimentin, a class III intermediate filament protein, as a Rab7a interacting protein. Rab7a is a member of the Rab family of small GTPases and it controls vesicular membrane traffic to late endosomes and lysosomes. In addition, Rab7a is important for maturation of phagosomes and autophagic vacuoles. We confirmed the interaction in HeLa cells by co-immunoprecipitation and pull-down experiments, and established that the interaction is direct using bacterially expressed recombinant proteins. Immunofluorescence analysis on HeLa cells indicate that Rab7a-positive vesicles sometimes overlap with vimentin filaments. Overexpression of Rab7a causes an increase in vimentin phosphorylation at different sites and causes redistribution of vimentin in the soluble fraction. Consistently, Rab7a silencing causes an increase of vimentin present in the insoluble fraction (assembled). Also, expression of Charcot–Marie–Tooth 2B-causing Rab7a mutant proteins induces vimentin phosphorylation and increases the amount of vimentin in the soluble fraction. Thus, modulation of expression levels of Rab7a wt or expression of Rab7a mutant proteins changes the assembly of vimentin and its phosphorylation state indicating that Rab7a is important for the regulation of vimentin function.

Abbreviations: GST, Glutathione-S-Transferase; HA, Hemagglutinin; EGFP, Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein

Keywords: Rab7a, Vimentin, Rab protein, Intermediate filaments, Phosphorylation, Two-hybrid

Highlights

► We searched for new Rab7a interacting proteins and we found vimentin. ► We demonstrated that Rab7a interacts directly with vimentin. ► Rab7a influences vimentin's phosphorylation and soluble/insoluble ratio. ► Rab7a regulates vimentin organization and function.

1. Introduction

Intermediate filaments (IFs) are a major element of the cytoskeleton of animal cells although the less understood [1,2]. The IF protein family comprises about 70 different, although structurally related, members that are grouped in five different classes [1,2]. IF proteins are expressed at different stages during development and differentiation and several different IF proteins are expressed at the same time in a cell type [1,2]. IFs are the primary determinants of cell architecture and are assembled and organized in a highly dynamic way [2,3]. Recently, it has been discovered that IFs are also important for organelle positioning, organelle transport and organelle function [4].

Vimentin, the major intermediate filament protein of mesenchymal cells, is highly conserved in vertebrates, with a variable expression pattern during development and differentiation [5]. It has been demonstrated that vimentin moves bi-directionally along microtubules using kinesin and dynein–dynactin [3]. Vimentin assembly and functions are regulated by phosphorylation and indeed vimentin shows a complex phosphorylation pattern with several kinases being involved [5,6]. Different phosphorylation patterns of vimentin are associated to different mitotic phases [5,6].

A number of studies have established that vimentin has many distinct and complex functions and it seems to organize several cellular processes as attachment, migration and signaling by controlling the function of key proteins [5]. For instance, vimentin has a key role in the migration of immune cells, in the regulation of membrane-associated protein complexes, in the modulation of protein kinases serving as a scaffold, and even in the regulation of DNA by, for instance, sequestering transcription factors [5]. Also, beside regulating integrin trafficking, vimentin regulates integrin functions by constituting the vimentin associated matrix adhesions that, in some cases, involve even a direct interaction between vimentin and integrins [5,7,8]. Furthermore, vimentin plays an important role also in membrane traffic. Indeed, vimentin filaments are required for late endocytic traffic, for correct positioning of endosomes and lysosomes and for maturation of autophagosomes [9,10].

Using the two-hybrid system we isolated vimentin as an interacting partner of Rab7a, a small GTPase controlling late endosomal traffic. Unlike Rab7b, which is involved in the regulation of endosomes to TGN transport [11,12], Rab7a is important for the biogenesis of lysosomes, phagolysosomes and autolysosomes [13–16]. Rab7a exerts its functions through several effector proteins, including RILP (the Rab-interacting lysosomal protein), which is important also for multivesicular body biogenesis [17–20]. Mutations in the rab7a gene cause a peripheral neuropathy, the Charcot–Marie–Tooth type 2b (CMT2B), characterized by prominent sensory loss, muscle weakness, muscle atrophy, recurrent infections and ulcers leading to amputations [21–25]. In the nervous system Rab7a controls endosomal trafficking and signaling of nerve growth factor receptors [26,27], and mutant Rab7a proteins causing CMT2B have altered nucleotides Koff, inhibit neurite outgrowth and alter neurotrophin trafficking and signaling [28–33].

Our data indicate that Rab7a interacts directly with vimentin, and that this interaction modulates vimentin phosphorylation and assembly. Thus, we have discovered a new mechanism for vimentin regulation. These data suggest that Rab7a could, through the interaction with vimentin, be involved in the regulation of new cellular processes.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cells and reagents

Restriction and modification enzymes were from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). Chemicals and tissue culture reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). HeLa cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat inactivated FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 10 mg/ml streptomycin, in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C.

2.2. Yeast two-hybrid assay

A Gal4-binding domain/Rab7a ΔC fusion construct in the pGBKT7 vector was used to screen a pretransformed normalized human Matchmaker cDNA library (Clontech, # 638874) in order to identify Rab7a interacting proteins using AH109 yeast cells [34–36]. Transformants were plated onto synthetic medium lacking His, Leu, and Trp and clones were picked up after 5–6 days of incubation at 30 °C. From 2 × 106 primary transformants, 18 were encoding true positive clones and two of them encoded vimentin. Specificity tests were made transforming AH109 yeast cells with the pGBKT7 vector or PGBKT7-RILP (as a negative controls) or the pGBKT7-Rab7a wt constructs, and with the PGADT7-vimentin constructs. Clones were then assayed for growth on selective medium and for β-galactosidase activity using o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactoside as a substrate [34–36].

2.3. Plasmid construction

Rab7a constructs used in this study have been described previously [28,31,37]. Myc-tagged vimentin was obtained from OriGene (RC201546). Vimentin ORF was transferred using AsiSI and MluI restriction enzymes to pCMV6-AN-HA (OriGene, PS100013) to obtain a vector for the expression of HA-tagged vimentin. Vimentin ORF was also amplified by PCR using the following oligonucleotides: 5′-ACGCGGATCCATGTCCACCAGGTCCGTG-3′ and 5′-CCGGAATTCTTATTCAAGGTCATCGTGATGC-3′ and cloned in the vector pGEX4T3 using the restriction enzymes BamHI and EcoRI in order to obtain a plasmid for the bacterial expression of GST-tagged vimentin. All the newly made constructs were sequenced verified.

2.4. Transfection and RNA interference

Transfection was performed using Metafectene Pro or Metafectene Easy from Biontex (Karlsruhe, DE), as indicated by the manufacturer. After 20 h of transfection cells were processed for immunofluorescence or biochemical assays. For RNA interference control RNA (sense sequence 5′-ACUUCGAGCGUGCAUGGCUTT-3′ and antisense sequence 5′-AGCCAUGCACGCUCGAAGUTT-3′) and Rab7a-1 siRNAs (sense sequence 5′-GGAUGACCUCUAGGAAGAATT-3′ and antisense sequence 5′-UUCUUCCUAGAGGUCAUCCTT-3′) were purchased from MWG-Biotech (Ebersberg, Germany). The Rab7a siRNAs were efficient in silencing Rab7a as mRNA levels were reduced of about 80% and the Rab7a endogenous protein was not anymore detectable by Western blot [28]. Briefly, HeLa cells were plated 1 day before transfection in 6 cm diameter tissue culture dishes, transfected with siRNAs using Oligofectamine from Invitrogen (Milan, Italy) for 72 h, re-plated and left 48 h before performing further experiments.

2.5. Coimmunoprecipitation, pull-down and direct interaction experiments

For co-immunoprecipitation 25 μl of anti-HA resin (Ezview Red Anti-HA Affinity gel from Sigma-Aldrich) was used according to the manufacturer instructions. Briefly, cells were lysed with RIPA buffer (R078 from Sigma-Aldrich) and lysates were incubated with the anti-HA resin for 1 h at 4 °C on a rotating wheel. Co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous proteins was performed in HeLa cells using a crosslink immunoprecipitation kit (Pierce) following manufacturer instructions. Briefly, mouse anti-Rab7a antibody (Sigma) or mouse IgG was crosslinked to a resin using disuccinimidyl suberate (DSS) and incubated with pre-cleared HeLa cell lysate. After washing and elution immunoprecipitates were subjected to western blotting analysis using rabbit anti-Rab7a and anti-vimentin antibodies.

Immunoprecipitated samples were then loaded on SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting.

For pull-down His-tagged Rab7a wt and mutant proteins were expressed and purified from Escherichia coli BL21 as previously described [38]. 20 μg of each purified protein was bound to NiNTA resin at 4 °C for 45 min. Then the resin was washed 3 times for 5 min with a washing solution (NaH2PO4 50 mM, NaCl 300 mM, Imidazole 20 mM, pH 8.0) and incubated with the cellular lysate of N2A cells at 4 °C for 1 h. After extensive washing pulled-down samples were loaded on SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting.

For direct interaction GST, GST-tagged and His-tagged proteins were expressed in bacteria and affinity purified as described [17,38]. His-tagged Rab7a wt was incubated alone or in combination with GST or GST-tagged vimentin in PBS with 2 mM MgCl2 and GTP 0.8 mM for 1 h on a rotating wheel. Subsequently, samples were subject to GST pull-down using a glutathione resin. Samples were then subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

2.6. Antibodies

Mouse monoclonal 9E10 anti-Myc (ab32) and rabbit polyclonal anti-HA (ab9110) antibodies were from Abcam (Cambridge, UK), rabbit polyclonal anti-Rab7a (R4779), mouse monoclonal anti-Rab7a (R8779) and mouse monoclonal anti-tubulin (T5168) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), while anti-vimentin (sc-6260) and anti-vimentin phospho Ser38 (sc-16673) antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The anti-vimentin phospho Ser55 (ab22651) antibody was from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Primary antibodies were used at a 1:500–1:1000 unless otherwise indicated. Secondary antibodies conjugated with fluorochromes (used at 1:500 dilution) or HRP (used at 1:5000 dilution) were from Invitrogen (Milan, IT) or Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

2.7. Western blotting

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer and lysates were loaded onto SDS-PAGE. Separated proteins were transferred onto PVDF membrane from Millipore (Milan, IT). When phosphorylation was monitored, cells were lysed in the presence of phosphatase inhibitors (PhosphoSTOP, Roche). The filter was blocked in 5% milk in PBS for 30 min at room temperature, incubated with the appropriate primary antibody, washed in 5% milk in PBS and then incubated with a secondary antibody conjugated with HRP (diluted 1:5000). Bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence's system from GE (Milan, IT) or Western blotting Luminol Reagent from SantaCruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

2.8. Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy

Cells grown on 11-mm round glass coverslips were permeabilized, fixed and incubated with primary and secondary antibodies as described previously [39,40]. Cells were viewed with Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope.

2.9. Analysis of soluble vimentin/insoluble vimentin ratio

The method to analyze the soluble/insoluble ratio of vimentin has been previously described [41–43]. Briefly, cells were incubated at 4 °C for 30 min with phospho-buffer (NaCl 150 mM, Hepes 20 mM pH 7.6, 1% Igepal, 10% glycerol) containing phosphatase inhibitors (phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 1 from Sigma-Aldrich) and protease inhibitors (Complete protease inhibitor cocktail, Roche), and then scraped. Samples were then centrifuged at 20,000 g at 4 °C for 20 min. The supernatant (soluble fraction) was collected while the pellet (insoluble fraction) was washed 3 times with 2 mM EDTA in PBS1X, resuspended in Triton buffer (PBS 1 ×, 1% SDS, 0.1% Triton) and then boiled for 10 min and sonicated. Soluble and insoluble fractions were then separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred on nitrocellulose membrane and probed with the appropriate antibodies. Immunocomplexes were revealed by chemiluminescence. The ratio of soluble/insoluble vimentin was determined by scanning densitometry of immunoblots.

2.10. Quantification and statistical analysis

Protein levels were quantified by densitometry using the ImageJ software. The levels of vimentin were normalized against tubulin or against Rab7a, and analyzed statistically using Dunnett ANOVA post-hoc test. The analysis was based on the comparison of cells expressing HA-tagged Rab7a mutant proteins and cells expressing HA-tagged Rab7a or control cells as indicated.

3. Results

3.1. Rab7a interacts directly with vimentin

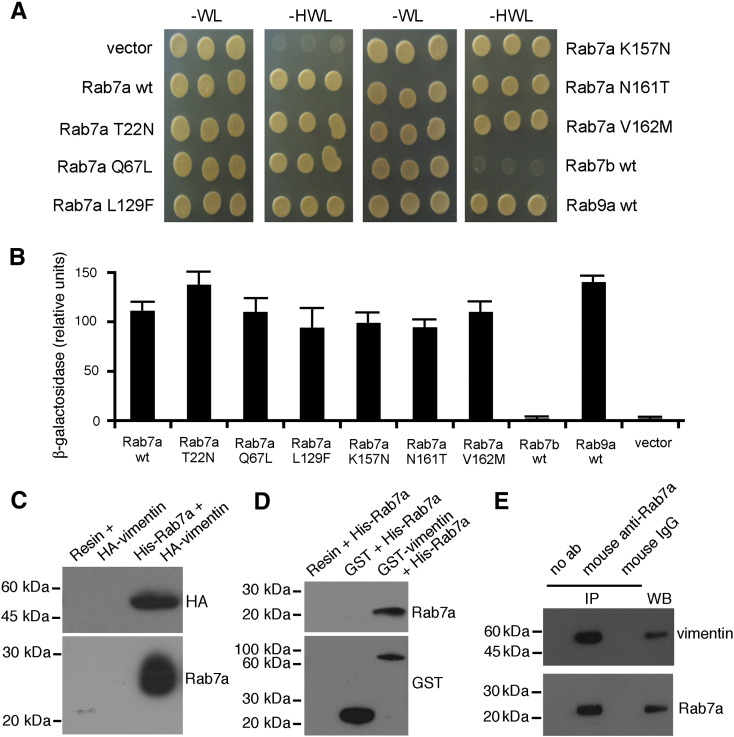

A yeast two-hybrid screen was used to identify proteins that interact with Rab7a. A Gal4-binding domain/Rab7a fusion construct was made in pGBKT7 vector and used to screen a human normalized universal cDNA library made from a collection of adult tissues, encoding proteins as C-terminal fusions with the transcriptional activation domain of Gal4 in the pGADT7Rec vector. From 2 × 106 primary transformants, 18 were encoding true positives that did not activate transcription in the presence of a non-specific test bait. Most of the clones encoded RILP while two transformants encoded the entire vimentin. The interaction was revealed by the growth of yeast cells expressing Rab7a wt and vimentin on synthetic medium lacking histidine (Fig. 1A). In the two-hybrid system the interaction was specific as yeast cells expressing vimentin alone were not able to grow without histidine (Fig. 1A). Moreover, vimentin was found to interact with Rab9, as previously published [43], but not with Ra7b, thus confirming that Rab7a and Rab7b are working on different steps of transport and interact with different effector proteins [44]. These results were confirmed using the other reporter gene, β-galactosidase (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, in the two-hybrid system vimentin was able to interact also with Rab7a mutant proteins such as the dominant negative T22N, the constitutively active Q67L and the CMT2B-causing mutants L129F, K157N, N161T and V162M (Fig. 1A–B).

Fig. 1.

Rab7a interacts directly with vimentin. AH109 yeast cells were co-transformed with pGADT7-vimentin and pGBKT7, PGBKT7-Rab7b, PGBKT7-Rab9 or pGBKT7-Rab7a wt or mutant constructs. (A) Double transformants were plated on WL and HWL synthetic medium and grown at 30 °C for two days. (B) The β-galactosidase activity of double transformants was measured using o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactoside as substrate as detailed in Materials and methods. Activities are measured as arbitrary relative units and represent mean ± s.d. values of 6 independent transformants from three independent experiments. (C) NiNTA resin alone or together with purified His-Rab7 was incubated with total extracts of HeLa cells overexpressing HA-vimentin. After affinity chromatography proteins were subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-HA and anti-Rab7a antibodies. (D) Glutathione resin alone or together with purified GST or GST-vimentin was incubated with purified His-Rab7a. After affinity chromatography proteins were subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-GST and anti-Rab7a antibodies. (E) Total extracts of HeLa cells and immunoprecipitates obtained with no antibodies (no ab), with mouse anti-Rab7a and with mouse IgG, as indicated, were subjected to WB analysis using rabbit anti-Rab7a and rabbit anti-vimentin antibodies.

To verify the results obtained with the two-hybrid screen we investigated whether Rab7a was able to pull down vimentin from cell extracts. We purified His-tagged Rab7a from bacteria and incubated it with total extracts of HeLa cells overexpressing HA-tagged vimentin. As shown in Fig. 1C, His-tagged Rab7a pulled down HA-vimentin from total cell extracts, thus confirming that the two proteins are present in the same complex. Subsequently, to check if the interaction was direct, we purified bacterially expressed GST-tagged vimentin and His-tagged Rab7a, we incubated them together and then we precipitated GST-tagged vimentin using the glutathione resin. Western blot analysis of the precipitated proteins revealed that His-Rab7a was able to bind to GST-vimentin (Fig. 1D). No binding of His-Rab7a to the resin alone or to the GST protein was detected (Fig. 1D). The binding between endogenous Rab7a and vimentin was also demonstrated (Fig. 1E) thus confirming the physiological significance of this interaction,

Altogether these data demonstrate that Rab7a interacts directly with vimentin.

3.2. Differential interaction of Rab7a mutant proteins with vimentin

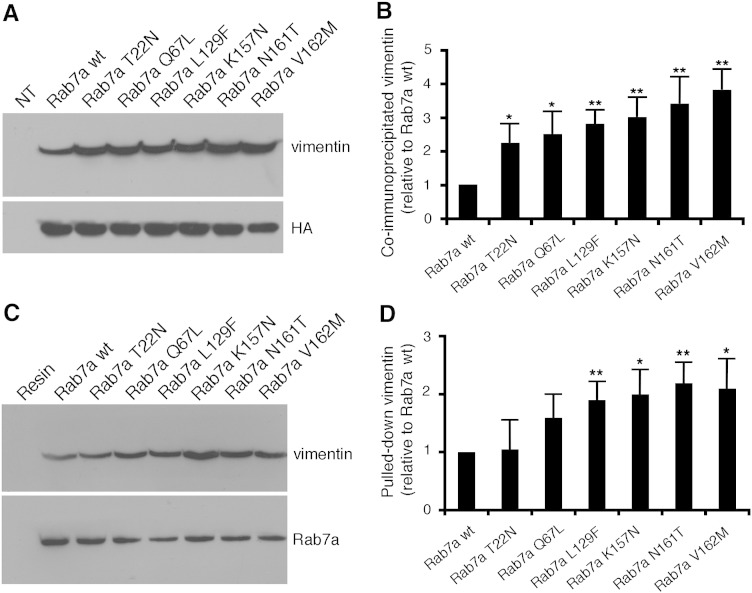

Having established that Rab7a interacts directly with vimentin we checked, using co-immunoprecipitation and pull-down, the ability to interact of the different Rab7a mutant proteins with vimentin. In particular, we used the dominant negative T22N mutant, the constitutively active Q67L mutant and the CMT2b-causing Rab7a mutants L129F, K157N, N161T and V162M.

Interestingly, Rab7a wt and mutant proteins were all able to co-immunoprecipitate endogenous vimentin, thus again proving the interaction between Rab7a and vimentin, but to different extent. Indeed, more vimentin was co-immunoprecipitated with the four CMT2b-causing mutant proteins (Fig. 2A). Quantification of three independent experiments revealed that these mutants were able to co-immunoprecipitate about 3 fold more efficiently endogenous vimentin compared to Rab7a wt (Fig. 2B). Similar results were obtained using bacterially purified His-tagged Rab7a wt and mutant proteins, in order to pull-down endogenous vimentin from HeLa total extracts (Fig. 2C–D). Indeed, CMT2B-causing Rab7a mutant proteins were able to pull-down vimentin about 2 fold more efficiently than Rab7a wt (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

CMT2B-causing Rab7a mutant proteins show altered binding to vimentin. (A) HA-tagged Rab7a wt and mutant proteins were expressed in HeLa cells and immunoprecipitated using an anti-HA resin. Immunoprecipitates were subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-vimentin and anti-HA antibodies. (B) Quantification of four independent co-immunoprecipitation experiments. Intensities of the bands were quantified by densitometry, normalized against the amount of the Rab7a protein expressed. Values are mean ± s.d. (C) Purified His-tagged Rab7a wt and mutant proteins, as indicated, were incubated with total extracts of HeLa cells. Precipitated proteins after affinity chromatography with NiNTA resin were loaded on SDS-PAGE and subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-vimentin and anti-Rab7a antibodies. (D) Quantification of four independent pull-down experiments. Intensities of the bands were quantified by densitometry and normalized against the amount of the Rab7a protein. Values are mean ± s.d. Values obtained expressing disease-causing Rab7a mutant proteins were found to be significantly different from the values obtained in cells expressing Rab7a wt (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

These data indicate that CMT2B-causing Rab7a mutant proteins interact more strongly with vimentin.

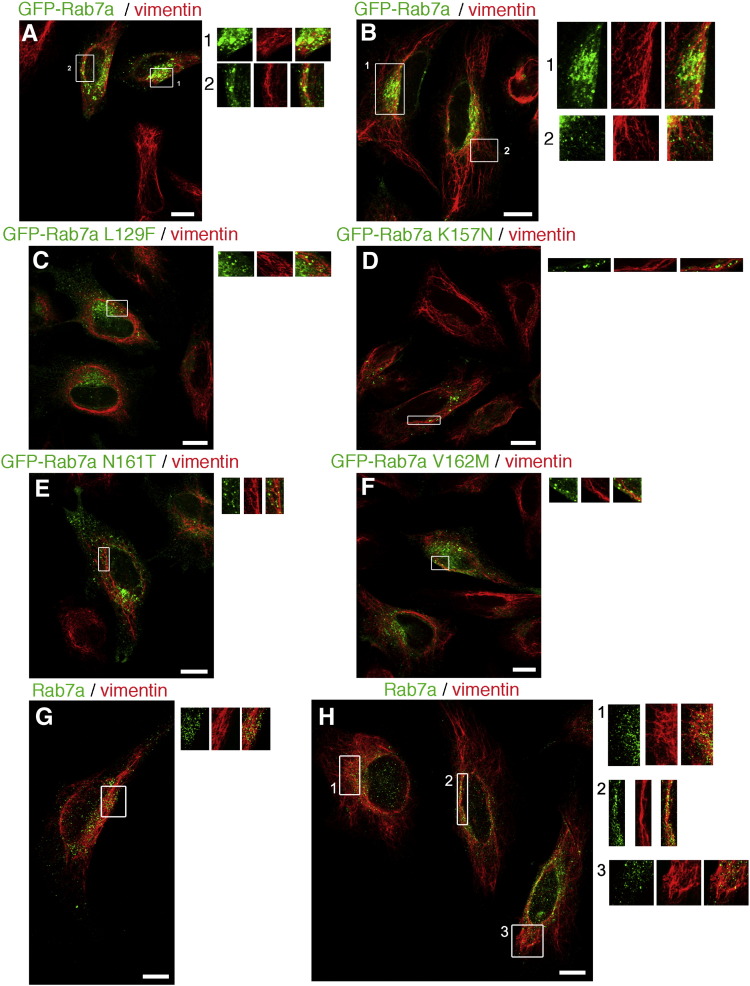

3.3. Intracellular localization of Rab7a wt and mutant proteins with vimentin filaments

To investigate a possible role of this interaction we decided to analyze the intracellular localization of Rab7a and vimentin in HeLa cells. Initially, we overexpressed in HeLa cells GFP-tagged Rab7a wt and examined its distribution using a specific antibody against vimentin. Immunofluorescence analysis revealed that there was some, although extremely limited, colocalization of Rab7a with vimentin (Fig. 3A–B). In particular, vesicles bearing Rab7a showed regions of colocalization with vimentin filaments and, sometimes, vesicles were surrounded by vimentin filaments (Fig. 3A–B). Furthermore, Rab7a-bearing vesicles were seen laying over vimentin filaments (Fig. 3A–B). Similar results were obtained by expressing CMT-2b causing Rab7a mutants (Fig. 3C–F). Immunofluorescence analysis on endogenous proteins revealed a similar distribution pattern (Fig. 3G–H).

Fig. 3.

Intracellular localization of Rab7a and vimentin filaments. HeLa cells overexpressing GFP-tagged Rab7a wt (A–B) or L129F (C), K157N (D), N161T (E) V162M and (F) mutant proteins were subjected to immunofluorescence analysis using an anti-vimentin antibody followed by a Cy3 secondary antibody. (G–H) Hela cells were subjected to immunofluorescence analysis using anti-Rab7a and anti-vimentin antibodies followed by Cy2 and a Cy3 conjugated secondary antibodies, respectively. The images represent maximum-intensity projections of Z stacks. Bar = 10 μm.

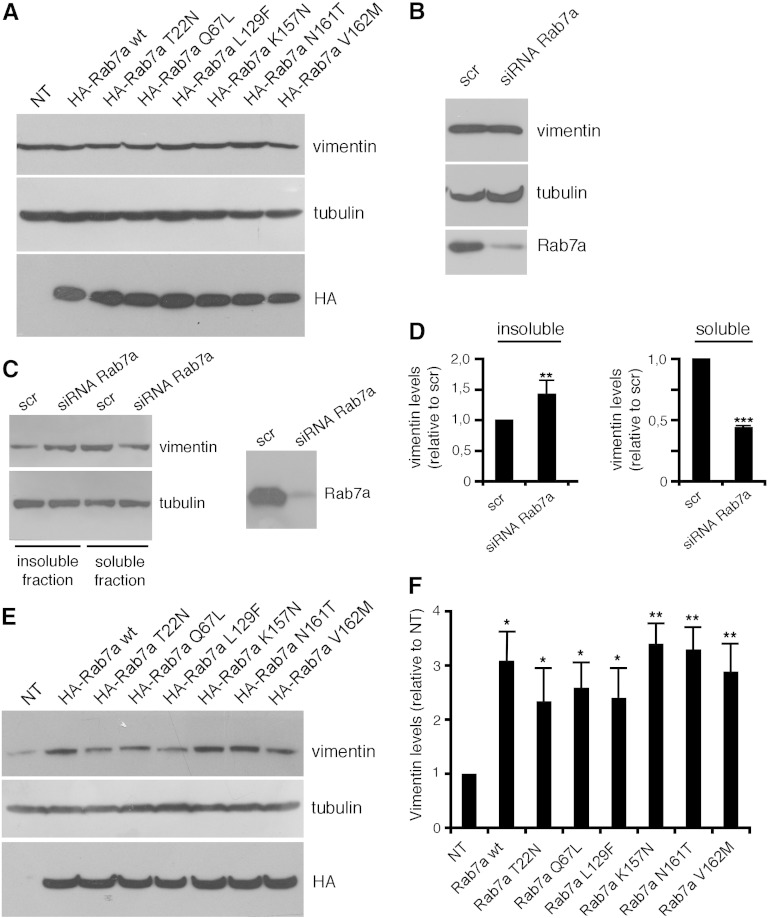

3.4. Modulation of Rab7a expression changes vimentin soluble/insoluble ratio

To further investigate the effect of Rab7a on vimentin we examined whether the total amount of vimentin changed after modulation of Rab7a expression in order to establish if Rab7 regulates vimentin expression, stability or degradation (Fig. 4A,B). Expression or silencing of Rab7a did not change the amount of vimentin mRNA, as judged by real time PCR (data not shown), nor the amount of vimentin protein suggesting that Rab7a does not influence vimentin expression or degradation (Fig. 4A, B). No differences in the amount of total vimentin were observed also when Rab7a mutant proteins were expressed (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Modulation of Rab7a expression alters vimentin filament organization. (A) Total extract of Hela cells (NT) or of HeLa cells expressing HA-tagged Rab7a wt and mutant proteins as indicated were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-vimentin, anti tubulin and anti-HA antibodies. Total extracts (B) or soluble and insoluble extracts (C) of Hela cells treated with control RNA (scr) or with Rab7a siRNA as indicated were subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-Rab7a, anti-tubulin and anti-vimentin antibodies. (D) Quantification of soluble and insoluble vimentins in Rab7a-depleted HeLa cells. The values represent the mean ± s.d. of four independent experiments. The intensities were quantified by densitometry, normalized against the amount of tubulin and plotted relatively to the intensities obtained in cells transfected with control RNA (scr). Values obtained in Rab7a-depleted cells were found to be significantly different from the values obtained in control (scr) cells (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). (E) Soluble extracts of HeLa cells overexpressing HA-tagged Rab7a wt and mutant proteins (as indicated) were subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-vimentin, anti-tubulin and anti-HA antibodies. (F) Quantification of soluble vimentin in HeLa cells transfected with HA-Rab7a wt and mutant proteins. The values represent the mean ± s.d. of four independent experiments. The intensities were quantified by densitometry, normalized against the amount of tubulin and plotted relatively to the intensities obtained in control cells (NT). Values obtained in cells overexpressing Rab7a wt or expressing disease-causing Rab7a mutant proteins were found to be significantly different from the values obtained in control (NT) cells (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

Subsequently, we decided to determine whether Rab7a influenced vimentin assembly/disassembly. Vimentin is present in cells as soluble precursors that can be assembled in filaments that are highly insoluble. Thus, we silenced Rab7a in HeLa cells, and then we analyzed the amount of vimentin present in the soluble and insoluble fractions. Interestingly, Rab7a-depleted cells showed an increase of vimentin in the insoluble fraction (Fig. 4C). Consistently, in these cells the amount of vimentin in the soluble fraction was decreased (Fig. 4C). Quantification of four independent experiments indicated that these differences were statistically significant (Fig. 4D). Then we measured the amount of vimentin present in the soluble fraction upon overexpression of Rab7a wt. In cells overexpressing Rab7a wt the amount of vimentin in the soluble fraction increased significantly (Fig. 4E–F). Furthermore, overexpression of CMT2B-causing Rab7a mutants caused a strong increase of soluble vimentin (Fig. 4E–F).

These data suggest that Rab7a is able to regulate vimentin assembly and disassembly and that CMT2B-causing Rab7a mutant proteins could induce vimentin disassembly.

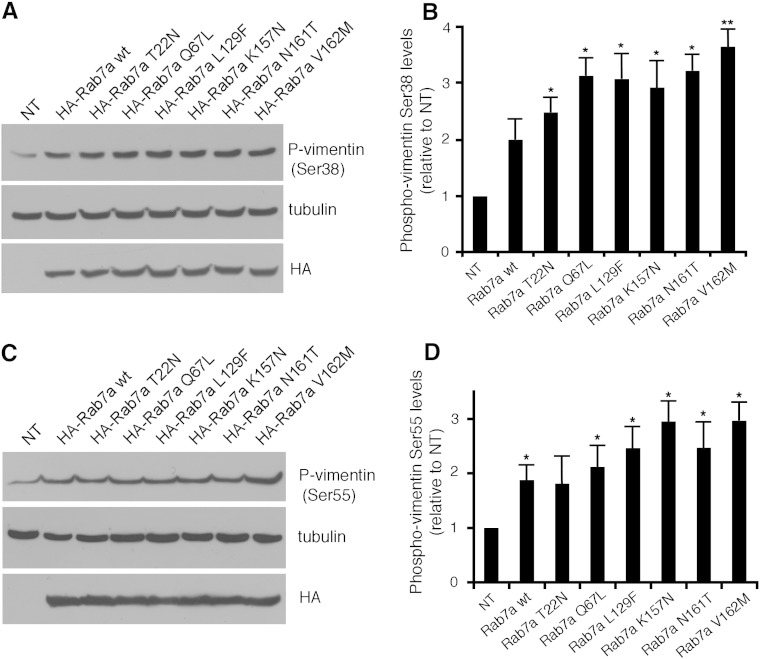

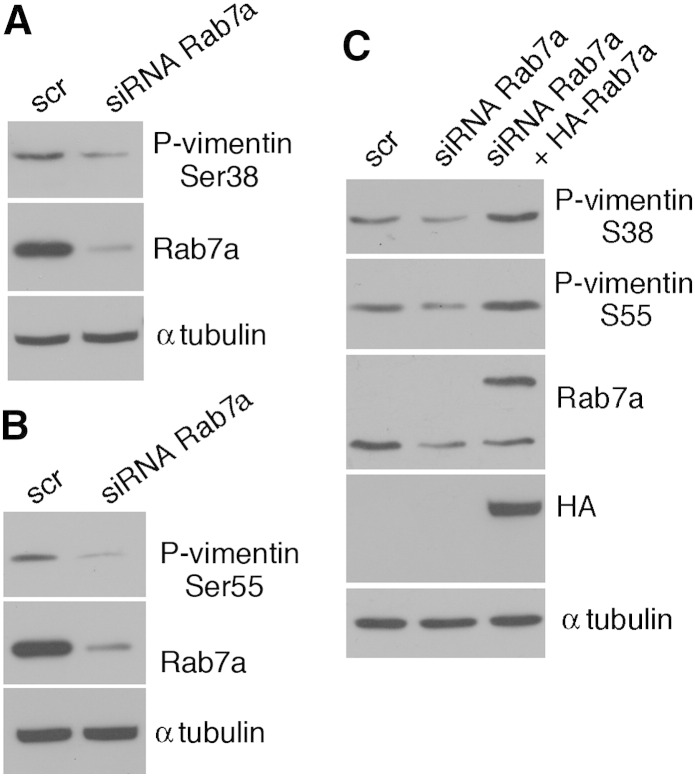

3.5. Modulation of Rab7a expression changes the phosphorylation pattern of vimentin

Vimentin dynamics are regulated by phosphorylation. Site-specific phosphorylation induces disassembly of vimentin filaments, and the increase of phosphorylation accompanies vimentin filament reorganization in vivo [45]. Vimentin is phosphorylated by different protein kinases at several sites. In order to establish if Rab7a regulates vimentin assembly by affecting vimentin phosphorylation, we used specific antibodies against phospho-vimentin at positions Ser-38 and Ser-55 on total extracts of HeLa cells overexpressing HA-Rab7a wt and mutant proteins. Notably, Rab7a overexpression caused an increased phosphorylation of vimentin both at Ser38 and Ser55 positions (Fig. 5A–D). Importantly, this increase was stronger when CMT2B-causing Rab7a mutants were expressed (Fig. 5A–D). Consistently, phosphorylation at these sites diminished in Rab7a-silenced cells (Fig. 6A,B). Importantly, phosphorylation levels at Ser-38 and Ser-55 were increased by overexpression of HA-tagged Rab7a wt in Rab7a-silenced cells, thus excluding off-target effects (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 5.

Rab7a overexpression induces vimentin phosphorylation. Total extracts of control HeLa cells (NT) or HeLa cells transfected with HA-tagged Rab7a wt and mutant proteins, as indicated, were subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-phospho-vimentin Ser38 (A) or Ser55 (C), anti-tubulin and anti-HA antibodies. (B, D) Quantification of phosphorylated vimentin Ser38 (B) or Ser55 (D) in cells expressing Rab7a wt and mutant proteins. Values represent the mean mean ± s.d. of four independent experiments. Intensities of the bands were quantified by densitometry, normalized against the amount of tubulin and plotted relatively to the values obtained in control HeLa cells (NT). Values obtained in cells expressing disease-causing Rab7a mutant proteins were found to be significantly different from the values obtained in control (NT) cells (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

Fig. 6.

Vimentin phosphorylation is decreased in Rab7a-silenced cells. (A–B) Total extracts of Hela cells treated with control RNA (scr) or with Rab7a siRNA, as indicated, were subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-phospho Ser38 (A) or Ser55 (B), anti-tubulin and anti-Rab7a. (C) Total extracts of Hela cells treated with control RNA (scr) or with Rab7a siRNA and transfected with HA-Rab7a, as indicated, were subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-phospho Ser38 and anti-phospho Ser55 vimentins, anti-Rab7a, anti-HA and anti-α-tubulin antibodies.

These data indicate that Rab7a regulates vimentin assembly triggering phosphorylation of vimentin at two different sites, and that disease-causing Rab7a mutant proteins induce stronger vimentin phosphorylation.

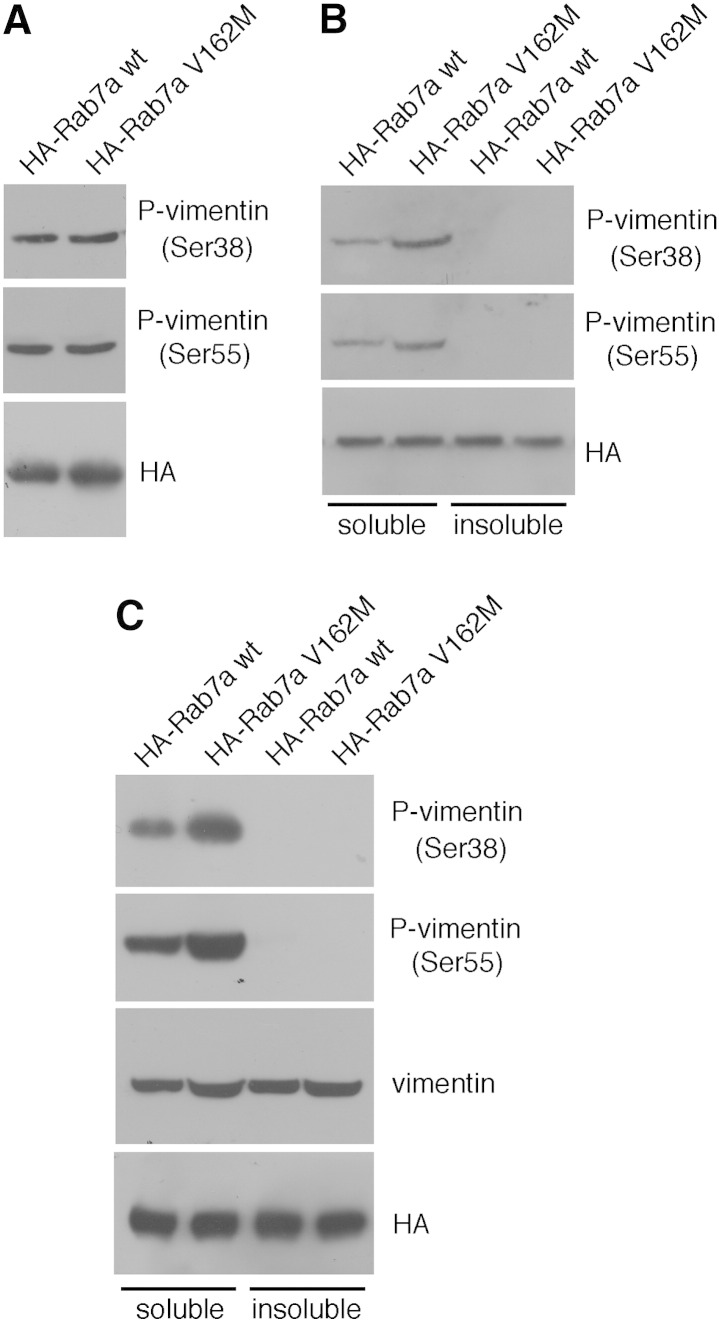

3.6. Rab7 interacts with soluble and filamentous vimentin

The interaction between the bacterially expressed Rab7a and vimentin proteins (Fig. 1D) indicates that Rab7 is able to interact with unphosphorylated vimentin. In order to establish if Rab7a is able to interact also with phosphorylated forms of vimentin we immunoprecipitated HA-tagged Rab7a wt and Rab7a V162M from total extracts of transfected HeLa cells. Both proteins were able to co-immunoprecipitate Ser38 phospho-vimentin and Ser55 phospho-vimentin (Fig. 7A) thus indicating that Rab7a is able to interact also with vimentin phosphorylated at positions 38 and 55. Western blot analysis on total extracts confirmed that, as previously published [46,47], Ser38 and Ser55 phospho-vimentins are present only in the soluble fraction (Fig. 7B). Thus, in order to establish if Rab7 was binding only to soluble or also to filamentous vimentin we separated soluble and insoluble fractions of HA-tagged Rab7a wt and Rab7a V162M expressing HeLa cells and, subsequently, we did a co-immunoprecipitation experiment (Fig. 7C). Rab7a wt and Rab7a V162M were able to co-immunoprecipitate vimentin from both soluble and insoluble fractions while, as expected, Ser38 and Ser55 phospho-vimentins were immunoprecipitated only from the soluble fraction (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7.

Rab7a is able to interact with the phosphorylated form of vimentin. (A) Total extract of HeLa cells expressing HA-tagged Rab7a wt or Rab7a V162M were subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-HA resin. Western blot analysis of immunoprecipitates was made using anti-HA, anti-phospho-vimentins Ser55 and Ser 38. (B) Soluble and insoluble fractions of Hela cells expressing HA-tagged Rab7a wt or Rab7a V162M were subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-phospho-vimentins Ser55 and Ser 38. (C) Soluble and insoluble fractions of HeLa cells expressing HA-tagged Rab7a wt or Rab7a V162M were immunoprecipitated using anti-HA resin. Immunoprecipitates were subjected to WB analysis using anti-phospho-vimentins Ser38 and Ser55, anti-vimentin and anti-HA antibodies.

These data indicate that Rab7 is able to interact with soluble and filamentous vimentin and also with the S38 and S55 phosphorylated forms.

4. Discussion

Vimentin is a key cytoskeletal protein that, through its highly dynamic disassembly/assembly and spatial reorganization, participates in adhesion, migration survival, membrane trafficking and cell signaling processes [48].

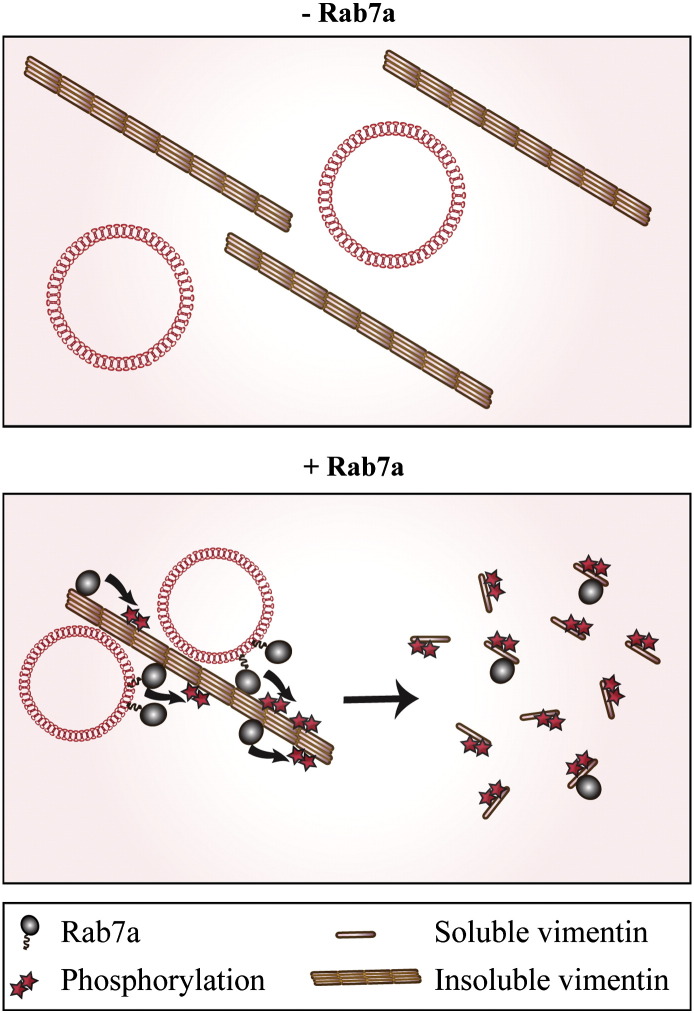

Here, we demonstrated for the first time that the small GTPase Rab7a interacts directly with vimentin and regulates its assembly. Indeed, overexpression of Rab7a increases the soluble/insoluble vimentin ratio raising the pool of free, disassembled and phosphorylated vimentin that can be used to reorganize vimentin filaments (Fig. 8). Consistently, in Rab7a-depleted cells vimentin soluble/insoluble ratio is decreased indicating that more vimentin is present in its filamentous form and less is available for filament reorganization (Figs. 4–6). In addition, we demonstrated that overexpression of Rab7a wt and mutant proteins increases phosphorylation of Ser38 and Ser55 amino acids (Fig. 5) suggesting that Rab7a controls, directly or indirectly, vimentin phosphorylation. Thus we report for the first time the discovery of a new regulatory mechanism for vimentin filament organization mediated by the small GTPase Rab7a.

Fig. 8.

A model for the role of Rab7a in vimentin assembly. Rab7a induces vimentin phosphorylation at different sites and this, in turn, causes vimentin disassembly. Rab7a is able to bind both to the soluble and filamentous forms of vimentin.

Both dominant negative and active mutants interact with vimentin having similar effects. This fact, in contrast with the proposed role of Rab proteins as molecular switches, has been reported for several other Rab proteins. For instance, both dominant negative and constitutively active Rab17 mutants stimulate transcytosis and apical recycling [49]. Also, both forms of Rab10 and Rab21 exhibit similar effect on lipid droplet size [50], and HOPS complex seems to work equally well with GDP- and GTP-bound Ypt7, the yeast counterpart of mammalian Rab7 [51]. Furthermore, in plants both forms of Rab11b negatively impact pollen tube growth properties and male fertility [52]. A possible explanation is that a proper ratio of inactive (GDP-bound) and active (GTP-bound) forms of the protein is necessary for the correct regulation of downstream processes. In addition, in the case of Rab7 and vimentin, although both kinds of mutants show similar effects, GTP-bound mutants seem to display higher binding to vimentin and affect more its assembly leading to suppose that small differences in vitro may have a larger impact in vivo.

The discovery of the interaction between Rab7 and vimentin is of importance for several reasons.

First of all, recent evidence indicates that intermediate filaments are important for organelle positioning, movement and function [4]. In particular, vimentin filaments have a fundamental role in endocytic membrane traffic, being required for correct positioning of endosomes and lysosomes, for transport to late endosomes and lysosomes, and for maturation of autophagosomes [9,10]. As these functions are shared with Rab7a, it is tempting to speculate that Rab7a and vimentin act in concert to regulate some or all of these processes. In support of this hypothesis, our data demonstrate a tight relationship between Rab7a, a protein involved in the regulation of membrane traffic, and vimentin, strongly supporting the idea that intermediate filaments have a key role in membrane traffic, as previously suggested [4]. Notably, also another Rab GTPase localized to late endosomes, Rab9, has been found to interact with vimentin and this interaction is altered by lipid accumulation in Niemann–Pick type C1 disease suggesting a concerted role of Rab9 and vimentin in the regulation of intracellular lipid transport [43].

Second, it has been demonstrated that neurons possess an evolutionary conserved damage-response program that recapitulates the developmental stages required for neuronal differentiation (as neurite outgrowth and synapses formation) and expression of vimentin is part of this program [53]. Indeed, vimentin is normally not expressed or expressed at very low levels in mature neurons, but its expression is induced during axonal regeneration after injury [54]. As an example, neuronal expression of vimentin has been demonstrated in Alzheimer's disease as part of damage-response mechanism [53]. Furthermore, in neurons of teleost fish, which show a much higher regenerative ability compared to mammals, a strong up-regulation of vimentin has been reported during regeneration [55].

Rab7a mutations cause the peripheral CMT2B neuropathy [22,24,25,56]. Others and we have demonstrated that these mutations alter neurite outgrowth and neurotrophin trafficking and signaling [30,32,33]. As the onset of CMT2B is in the second-third decade of life and thus development is not affected, these mutant proteins could, besides being responsible for neuronal degeneration, also affect axonal regeneration. Hence, altered interaction of the CMT2B-causing Rab7a mutant proteins with vimentin could result in variations of vimentin distribution and function that might in turn, impair the damage-response program, compromising axonal regeneration. In addition vimentin has been found to co-assemble with the light neurofilament and the corresponding NEFL gene is mutated in several forms of the CMT disease suggesting that alterations of vimentin cytoskeleton could affect also neurofilament organization [57–61].

Third, vimentin is an important factor for tumorigenesis. Tissues going through “epithelial to mesenchymal transition” express vimentin, and vimentin seems to contribute heavily to the acquisition of tumorigenic and metastatic properties to the point that it has been demonstrated that vimentin expression correlates with poor outcome for epithelial cancers [48,62–66]. In addition, in tumor cells the amount of free soluble vimentin is significantly higher than in normal cells suggesting that vimentin could be a novel target for therapeutical tools against cancer cells [48,67]. Rab proteins are also involved in signal transduction and in particular Rab7a has been demonstrated to prevent growth factor-independent survival and to control EGFR endocytic trafficking, whose alterations have been linked to tumorigenesis [68–71]. The discovery of a tight relationship between Rab7a and vimentin supports the notion that Rab7a is implicated in tumorigenesis and indicates that modulation of Rab7a function could be useful to alter vimentin assembly and thus might represent a targeted therapy for epithelial tumors.

In addition, it has recently been reported that endocytosis is important for neuronal migration and a number of endocytic Rab have been shown to participate in this process [72]. For instance, inhibition of Rab7a mediated transport to endocytic degradative compartments affects the final phase of neuronal migration and maturation [72]. It is tempting to speculate that Rab7a could act in this process by regulating vimentin.

5. Conclusions

The findings that Rab7a interacts with vimentin and controls vimentin phosphorylation state and assembly suggest a close connection between membrane traffic regulatory proteins and intermediate filaments. Furthermore, the discovery of the interaction between Rab7a and vimentin opens new scenarios on the cellular role of Rab7 that will have to be further investigated.

Acknowledgements

We thank Claudia Donno for technical help with some two-hybrid experiments. The financial support of AIRC (Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro, Investigator Grant N. 10213 to C. B.), of Telethon-Italy (Grant N. GGP09045 to C.B.) and of MIUR (PRIN 2010–2011 and ex60% to C.B.) is gratefully acknowledged. The authors declare that they have no conflicting financial interest.

References

- 1.Minin A.A., Moldaver M.N. Intermediate vimentin filaments and their role in intracellular organelle distribution. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2008;73:1453–1466. doi: 10.1134/s0006297908130063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herrmann H., Strelkov S.V., Burkhard P., Aebi U. Intermediate filaments: primary determinants of cell architecture and plasticity. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:1772–1783. doi: 10.1172/JCI38214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarke E.J., Allan V. Intermediate filaments: vimentin moves in. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:R596–R598. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Styers M.L., Kowalczyk A.P., Faundez V. Intermediate filaments and vesicular membrane traffic: the odd couple's first dance? Traffic. 2005;6:359–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ivaska J., Pallari H.M., Nevo J., Eriksson J.E. Novel functions of vimentin in cell adhesion, migration, and signaling. Exp. Cell Res. 2007;313:2050–2062. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sihag R.K., Inagaki M., Yamaguchi T., Shea T.B., Pant H.C. Role of phosphorylation on the structural dynamics and function of types III and IV intermediate filaments. Exp. Cell Res. 2007;313:2098–3109. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzales M., Weksler B., Tsuruta D., Goldman R.D., Yoon K.J., Hopkinson S.B., Flitney F.W., Jones J.C. Structure and function of a vimentin-associated matrix adhesion in endothelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:85–100. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kreis S., Schonfeld H.J., Melchior C., Steiner B., Kieffer N. The intermediate filament protein vimentin binds specifically to a recombinant integrin alpha2/beta1 cytoplasmic tail complex and co-localizes with native alpha2/beta1 in endothelial cell focal adhesions. Exp. Cell Res. 2005;305:110–121. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Styers M.L., Salazar G., Love R., Peden A.A., Kowalczyk A.P., Faundez V. The endo-lysosomal sorting machinery interacts with the intermediate filament cytoskeleton. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:5369–5382. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-03-0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holen I., Gordon P.B., Seglen P.O. Protein kinase-dependent effects of okadaic acid on hepatocytic autophagy and cytoskeletal integrity. Biochem. J. 1992;284:633–636. doi: 10.1042/bj2840633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Progida C., Cogli L., Piro F., De Luca A., Bakke O., Bucci C. Rab7b controls trafficking from endosomes to the TGN. J. Cell Sci. 2010;123:1480–1491. doi: 10.1242/jcs.051474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Progida C., Nielsen M.S., Koster G., Bucci C., B. O. Dynamics of Rab7b-dependent transport of sorting receptors. Traffic. 2012;13:1273–1285. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2012.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bucci C., Frunzio R., Chiariotti L., Brown A.L., Rechler M.M., Bruni C.B. A new member of the ras gene superfamily identified in a rat liver cell line. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:9979–9993. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.21.9979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bucci C., Thomsen P., Nicoziani P., McCarthy J., van Deurs B. Rab7: a key to lysosome biogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2000;11:467–480. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.2.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrison R., Bucci C., Vieira O., Schroer T., Grinstein S. Phagosomes fuse with late endosomes and/or lysosomes by extension of membrane protrusions along microtubules: role of Rab7 and RILP. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:6494–6506. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.18.6494-6506.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jager S., Bucci C., Tanida I., Ueno T., Kominami E., Saftig P., Eskelinen E.L. Role for Rab7 in maturation of late autophagic vacuoles. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:4837–4848. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cantalupo G., Alifano P., Roberti V., Bruni C.B., Bucci C. Rab-interacting lysosomal protein (RILP): the Rab7 effector required for transport to lysosomes. EMBO J. 2001;20:683–693. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.4.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Progida C., Spinosa M., De Luca A., Bucci C. RILP interacts with the VPS22 component of the ESCRT-II complex. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;347:1074–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Progida C., Malerød L., Stuffers S., Brech A., Bucci C., Stenmark H. RILP is required for proper morphology and function of late endosomes. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120:3729–3737. doi: 10.1242/jcs.017301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang T., Hong W. RILP interacts with VPS22 and VPS36 of ESCRT-II and regulates their membrane recruitment. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;350:413–423. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manganelli F., Pisciotta C., Provitera V., Taioli F., Iodice R., Topa A., Fabrizi G.M., Nolano M., Santoro L. Autonomic nervous system involvement in a new CMT2B family. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2012;17:361–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2012.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meggouh F., Bienfait H.M., Weterman M.A., de Visser M., Baas F. Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease due to a de novo mutation of the RAB7 gene. Neurology. 2006;67:1476–1478. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000240068.21499.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verhoeven K., De Jonghe P., Coen K., Verpoorten N., Auer-Grumbach M., Kwon J.M., FitzPatrick D., Schmedding E., De Vriendt E., Jacobs A., Van Gerwen V., Wagner K., Hartung H.P., Timmerman V. Mutations in the small GTP-ase late endosomal protein RAB7 cause Charcot–Marie–Tooth type 2B neuropathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;72:722–727. doi: 10.1086/367847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cogli L., Piro F., Bucci C. Rab7 and the CMT2B disease. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2009;37:1027–1031. doi: 10.1042/BST0371027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Houlden H., King R.H., Muddle J.R., Warner T.T., Reilly M.M., Orrell R.W., Ginsberg L. A novel RAB7 mutation associated with ulcero-mutilating neuropathy. Ann. Neurol. 2004;56:586–590. doi: 10.1002/ana.20281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saxena S., Bucci C., Weis J., Kruttgen A. The small GTPase Rab7 controls the endosomal trafficking and neuritogenic signaling of the nerve growth factor receptor TrkA. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:10930–10940. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2029-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deinhardt K., Salinas S., Verastegui C., Watson R., Worth D., Hanrahan S., Bucci C., Schiavo G. Rab5 and Rab7 control endocytic sorting along the axonal retrograde transport pathway. Neuron. 2006;52:293–305. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spinosa M.R., Progida C., De Luca A., Colucci A.M.R., Alifano P., Bucci C. Functional characterization of Rab7 mutant proteins associated with Charcot–Marie–Tooth type 2B disease. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:1640–1648. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3677-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCray B.A., Skordalakes E., Taylor J.P. Disease mutations in Rab7 result in unregulated nucleotide exchange and inappropriate activation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19:1033–1047. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cogli L., Progida C., Lecci R., Bramato R., Krüttgen A., Bucci C. CMT2B-associated Rab7 mutants inhibit neurite outgrowth. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120:491–501. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0696-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Luca A., Progida C., Spinosa M.R., Alifano P., Bucci C. Characterization of the Rab7K157N mutant protein associated with Charcot–Marie–Tooth type 2B. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;372:283–287. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.BasuRay S., Mukherjee S., Romero E., Wilson M.C., Wandinger-Ness A. Rab7 mutants associated with Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease exhibit enhanced NGF-stimulated signaling. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamauchi J., Torii T., Kusakawa S., Sanbe A., Nakamura K., Takashima S., Hamasaki H., Kawaguchi S., Miyamoto Y., Tanoue A. The mood stabilizer valproic acid improves defective neurite formation caused by Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease-associated mutant Rab7 through the JNK signaling pathway. J. Neurosci. Res. 2010;88:3189–3197. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chien C.T., Bartel P.L., Sternglanz R., Fields S. The two-hybrid system: a method to identify and clone genes for proteins that interact with a protein of interest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1991;88:9578–9582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bartel P., Chien C.T., Sternglanz R., Fields S. Elimination of false positives that arise in using the two-hybrid system. Biotechniques. 1993;14:920–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bartel P.L., Fields S. Analyzing protein–protein interactions using two-hybrid system. Methods Enzymol. 1995;254:241–263. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)54018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colucci A.M.R., Campana M.C., Bellopede M., Bucci C. The Rab-interacting lysosomal protein, a Rab7 and Rab34 effector, is capable of self-interaction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;334:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiariello M., Bruni C.B., Bucci C. The small GTPases Rab5a, Rab5b and Rab5c are differentially phosphorylated in vitro. FEBS Lett. 1999;453:20–24. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00686-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bucci C., Parton R.G., Mather I.H., Stunnenberg H., Simons K., Hoflack B., Zerial M. The small GTPase rab5 functions as a regulatory factor in the early endocytic pathway. Cell. 1992;70:715–728. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90306-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bucci C., Wandinger-Ness A., Lutcke A., Chiariello M., Bruni C., Zerial M. Rab5a is a common component of the apical and basolateral endocytic machinery in polarized epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994;91:5061–5065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.5061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meriane M., Mary S., Comunale F., Vignal E., Fort P., Gauthier-Rouviere C. Cdc42Hs and Rac1 GTPases induce the collapse of the vimentin intermediate filament network. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:33046–33052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001566200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Valgeirsdottir S., Claesson-Welsh L., Bongcam-Rudloff E., Hellman U., Westermark B., Heldin C.H. PDGF induces reorganization of vimentin filaments. J. Cell Sci. 1998;111:1973–1980. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.14.1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walter M., Chen F.W., Tamari F., Wang R., Ioannou Y.A. Endosomal lipid accumulation in NPC1 leads to inhibition of PKC, hypophosphorylation of vimentin and Rab9 entrapment. Biol. Cell. 2009;101:141–152. doi: 10.1042/BC20070171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bucci C., Bakke O., Progida C. Rab7b and receptors trafficking. Commun. Integr. Biol. 2010;3:401–404. doi: 10.4161/cib.3.5.12341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Inagaki M., Nishi Y., Nishizawa K., Matsuyama M., Sato C. Site-specific phosphorylation induces disassembly of vimentin filaments in vitro. Nature. 1987;328:649–652. doi: 10.1038/328649a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chou Y.H., Opal P., Quinlan R.A., Goldman R.D. The relative roles of specific N- and C-terminal phosphorylation sites in the disassembly of intermediate filament in mitotic BHK-21 cells. J. Cell Sci. 1996;109:817–826. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.4.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eriksson J.E., He T., Trejo-Skalli A.V., Härmälä-Braskén A.S., Hellman J., Chou Y.H., Goldman R.D. Specific in vivo phosphorylation sites determine the assembly dynamics of vimentin intermediate filaments. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:919–932. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lahat G., Zhu Q.S., Huang K.L., Wang S., Bolshakov S., Liu J., Torres K., Langley R.R., Lazar A.J., Hung M.C., Lev D. Vimentin is a novel anti-cancer therapeutic target; insights from in vitro and in vivo mice xenograft studies. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10105. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 49.Zacchi P., Stenmark H., Parton R.G., Orioli D., Lim F., Giner A., Mellman I., Zerial M., Murphy C. Rab17 regulates membrane trafficking through apical recycling endosomes in polarized epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 1998;140:1039–1053. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.5.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang C., Liu Z., Huang X. Rab32 is important for autophagy and lipid storage in Drosophila. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32086. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zick M., Wickner W. Phosphorylation of the effector complex HOPS by the vacuolar kinase Yck3p confers Rab nucleotide specificity for vacuole docking and fusion. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2012;23:3429–3437. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-04-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Graaf B.H., Cheung A.Y., Andreyeva T., Levasseur K., Kieliszewski M., Wu H.M. Rab11 GTPase-regulated membrane trafficking is crucial for tip-focused pollen tube growth in tobacco. Plant Cell. 2005;17:2564–2579. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.033183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Levin E.C., Acharya N.K., Sedeyn J.C., Venkataraman V., D'Andrea M.R., Wang H.Y., Nagele R.G. Neuronal expression of vimentin in the Alzheimer's disease brain may be part of a generalized dendritic damage-response mechanism. Brain Res. 2009;1298:194–207. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Toth C., Shim S.Y., Wang J., Jiang Y., Neumayer G., Belzil C., Liu W.Q., Martinez J., Zochodne D., Nguyen M.D. Ndel1 promotes axon regeneration via intermediate filaments. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clint S.C., Zupanc G.K. Up-regulation of vimentin expression during regeneration in the adult fish brain. Neuroreport. 2002;13:317–320. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200203040-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Verhoeven K., Timmerman V., Mauko B., Pieber T.R., De Jonghe P., Auer-Grumbach M. Recent advances in hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathies. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2006;19:474–480. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000245370.82317.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Monteiro M.J., Cleveland D.W. Expression of NF-L and NF-M in fibroblasts reveals coassembly of neurofilament and vimentin subunits. J. Cell Biol. 1989;108:579–583. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.2.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Abe A., Numakura C., Saito K., Koide H., Oka N., Honma A., Kishikawa Y., Hayasaka K. Neurofilament light chain polypeptide gene mutations in Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease: nonsense mutation probably causes a recessive phenotype. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;54:94–97. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2008.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jordanova A., De Jonghe P., Boerkoel C.F., Takashima H., De Vriendt E., Ceuterick C., Martin J.J., Butler I.J., Mancias P., Papasozomenos S.C., Terespolsky D., Potocki L., Brown C.W., Shy M., Rita D.A., Tournev I., Kremensky I., Lupski J.R., Timmerman V. Mutations in the neurofilament light chain gene (NEFL) cause early onset severe Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease. Brain. 2003;126:590–597. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shin J.S., Chung K.W., Cho S.Y., Yun J., Hwang S.J., Kang S.H., Cho E.M., Kim S.M., Choi B.O. NEFL Pro22Arg mutation in Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease type 1. J. Hum. Genet. 2008;53:936–940. doi: 10.1007/s10038-008-0333-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yum S.W., Zhang J., Mo K., Li J., Scherer S.S. A novel recessive NEFL mutation causes a severe, early-onset axonal neuropathy. Ann. Neurol. 2009;66:759–770. doi: 10.1002/ana.21728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kalluri R., Weinberg R.A. The basics of epithelial–mesenchymal transition. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:1420–1428. doi: 10.1172/JCI39104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang J., Mani S.A., Donaher J.L., Ramaswamy S., Itzykson R.A., Come C., Savagner P., Gitelman I., Richardson A., Weinberg R.A. Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell. 2004;117:927–939. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kang Y., Massague J. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: twist in development and metastasis. Cell. 2004;118:277–279. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sabo E., Miselevich I., Bejar J., Segenreich M., Wald M., Moskovitz B., Nativ O. The role of vimentin expression in predicting the long-term outcome of patients with localized renal cell carcinoma. Br. J. Urol. 1997;80:864–868. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1997.00489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim M.A., Lee H.S., Lee H.E., Kim J.H., Yang H.K., Oh D.Y., Bang Y.J., Kim W.H. Prognostic importance of epithelial–mesenchymal transition-related protein expression in gastric carcinoma. Histopathology. 2009;54:442–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kokkinos M.I., Wafai R., Wong M.K., Newgreen D.F., Thompson E.W., Waltham M. Vimentin and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human breast cancer—observations in vitro and in vivo. Cells Tissues Organs. 2007;185:191–203. doi: 10.1159/000101320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Edinger A.L., Cinalli R.M., Thompson C.B. Rab7 prevents growth factor-independent survival by inhibiting cell-autonomous nutrient transporter expression. Dev. Cell. 2003;5:571–582. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00291-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vitelli R., Santillo M., Lattero D., Chiariello M., Bifulco M., Bruni C., Bucci C. Role of the small GTPase Rab7 in the late endocytic pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:4391–4397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grandal M.V., Madshus I.H. Epidermal growth factor receptor and cancer: control of oncogenic signalling by endocytosis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2008;12:1527–1534. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00298.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bucci C., Chiariello M. Signal transduction gRABs attention. Cell. Signal. 2006;18:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kawauchi T., Sekine K., Shikanai M., Chihama K., Tomita K., Kubo K., Nakajima K., Nabeshima Y., Hoshino M. Rab GTPases-dependent endocytic pathways regulate neuronal migration and maturation through N-cadherin trafficking. Neuron. 2010;67:588–602. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]