Abstract

Changes at the invariable donor splice site + 1 guanine, relatively frequent in human genetic disease, are predicted to abrogate correct splicing, and thus are classified as null mutations. However, their ability to direct residual expression, which might have pathophysiological implications in several diseases, has been poorly investigated. As a model to address this issue, we studied the IVS6 + 1G > T mutation found in patients with severe deficiency of the protease triggering coagulation, factor VII (FVII), whose absence is considered lethal. In expression studies, the IVS6 + 1G > T induced exon 6 skipping and frame-shift, and prevented synthesis of correct FVII transcripts detectable by radioactive/fluorescent labelling or real-time RT-PCR. Intriguingly, the mutation induced the activation of a cryptic donor splice site in exon 6 and production of an in-frame 30 bp deleted transcript (8 ± 2%). Expression of this cDNA variant, lacking 10 residues in the activation domain, resulted in secretion of trace amounts (0.2 ± 0.04%) of protein with appreciable specific activity (48 ± 16% of wt-FVII). Altogether these data indicate that the IVS6 + 1G > T mutation is compatible with the synthesis of functional FVII molecules (~ 0.01% of normal, 1 pM), which could trigger coagulation. The low but detectable thrombin generation (352 ± 55 nM) measured in plasma from an IVS6 + 1G > T homozygote was consistent with a minimal initiation of the enzymatic cascade. In conclusion, we provide experimental clues for traces of FVII expression, which might have reverted an otherwise perinatally lethal genetic condition.

Keywords: Aberrant splicing, Residual gene expression, Human genetic disease, Coagulation factor deficiency

Highlights

► + 1G donor splice site mutations virtually suppress correct gene expression. ► Complete deficiency of coagulation factor VII (FVII) is lethal. ► The F7 IVS6 + 1G/T induces exon skipping and use of an in-frame cryptic 5'ss. ► The latter transcript encoded a protein lacking 10 residues in the activation domain. ► The residual activity of this variant might have reverted a lethal condition.

1. Introduction

The relationship between genotype and phenotype in severe forms of human genetic disease is often elusive because of methodological limitations in the quantitative evaluation of very low gene expression levels. While homozygous or compound heterozygous large gene deletions are unequivocally associated to null genetic conditions, the large majority of molecular defects can potentially account, through a variety of mechanisms, for residual function.

The process of spontaneous ribosome readthrough over nonsense mutations, in which the stop codon is mis-recognized by an aminoacyl-tRNA instead of termination factors [1], can partially restore full-length protein synthesis and function. This has been shown by us in coagulation factor VII (FVII) deficiency [2] and by Pacho and co-workers in LAMA3 deficiency [3].

Mutations at the completely conserved guanine at the intronic + 1 position (Fig. 1A, top) of donor splice sites (5'ss), a relatively frequent cause of severe human genetic diseases [4], are also generally considered null mutations as they are predicted to disrupt the splicing process [5]. However, for most of them, the complete loss-of-function feature has not been demonstrated. As a matter of fact, pre-mRNA splicing is a finely orchestrated process involving many exonic and intronic regulatory elements, whose interplay depends on the specific gene context [6,7]. Therefore, even mutations at the + 1 guanine might be associated to residual expression levels, as it has been shown for a + 1G > T in intron 2 of Fanconi Anemia C gene [8].

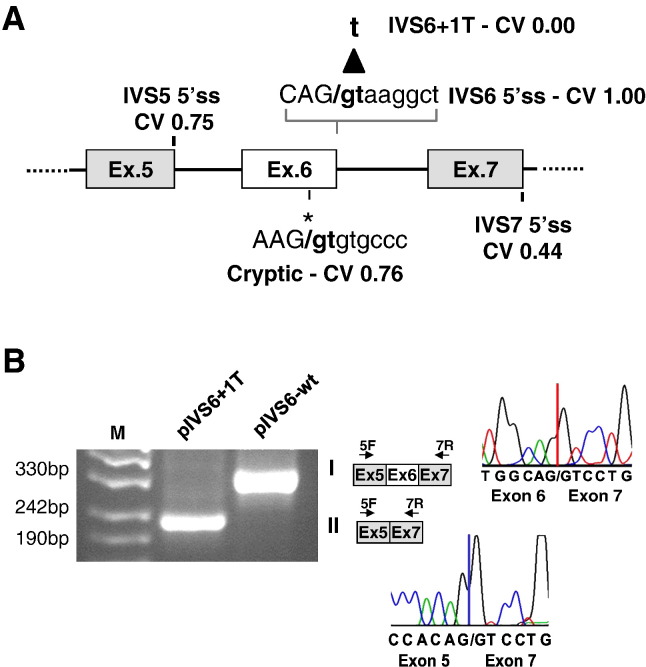

Fig. 1.

Characterization of the IVS6 + 1G > T mutation.

(A) Schematic representation of the F7 gene region interested by the IVS6 + 1G > T mutation, and cloned as F7 minigene into pcDNA3. The nucleotide sequence of the normal F7 IVS6 5'ss is reported above together with the donor splice site (5'ss) consensus. The G to T transversion is indicated by the arrow. The CV of the normal, mutated and exonic cryptic 5'ss, as well as of the IVS5 and IVS7 5'ss, are reported. (B) Separation on 2% agarose gel of RT-PCR products obtained from total RNA of cells expressing pIVS6-wt or the pIVS6 + 1T. The fragment sizes of the normal (I) and exon 6 skipped (II) transcript forms were 324 bp and 214 bp, respectively. The scheme of transcripts and of primers (arrows) is reported on the right together with the sequences.

M, molecular weight marker.

As a disease model to address this issue, we chose the inherited deficiency of FVII [9], which triggers blood coagulation, has the shortest half-life (3–5 h) and lowest plasma concentration (10 nM) among plasma serine proteases [10]. The absence of homozygotes for large F7 gene deletions (http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk; http://www.isth.org/default/index.cfm/publications/registries-databases/mutations) and the fatal perinatal bleeding in F7 knock-out mice [11] suggest that minimal levels of FVII are indispensable for life, thus rendering residual expression levels associated to mutations of crucial pathophysiological importance. Not surprisingly, the unique homozygous change affecting the intronic + 1G nucleotide of F7 gene so far described was found to be responsible for a lethal condition [12].

In this study, we demonstrate that the F7 IVS6 + 1G > T mutation (c.681 + 1G > T; NM-019616.1), found in two homozygous FVII-deficient patients with life-threatening bleeding symptoms, abrogates correct FVII mRNA processing but also activates an exonic cryptic 5'ss in cellular models. This accounts for the secretion of trace amounts of functional FVII molecules, which could trigger the enzymatic amplification pathway of coagulation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients and functional assays in plasma

F7 mutational screening [13] in FVII-deficient patients referred to Ramathibodi Hospital in Bangkok identified two homozygotes (PFVII-T3, PFVII-T4) for the IVS6 + 1G > T mutation (Fig. 1A).

PFVII-T3 (female, 21 years old) manifested gastrointestinal and intracranial bleeding at the age of 1 and 3 months, respectively. Subsequently, she exhibited several intracranial hemorrhages. She is under prophylaxis with fresh frozen plasma (FFP) since 1 year of age.

PFVII-T4 (male, 7 year old), presented with severe gastrointestinal bleeding at 4 and 6 months of age. He is receiving prophylaxis of FFP three times a week.

Plasma samples, withdrawn upon a five day wash out replacement therapy period, was available for PFVII-T3.

FVII activity and antigen [14], and thrombin generation [15,16] levels in plasma were assessed as described.

Formal informed consent for this study was obtained.

2.2. Expression vectors, cell culture and transfection

Expression vectors for the wild-type (pIVS6-wt) and mutant (pIVS6 + 1T) minigenes were obtained by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the human F7 gene region spanning exons 5 through 7 (1902 bp) from genomic DNA of a IVS6 + 1G > T carrier and subsequent cloning into the pcDNA3 plasmid (Fig. 1A).

Expression vector for the FVII-Δ218-227 variant was obtained by mutagenesis of the human FVII cDNA cloned in pcDNA3 vector [2,14] by using oligonucleotides 5′ATTGTGGGGGGCAAGGTCCTGTTGTTGGTG3′ and 5′CACCAACAACAGGACCTT GCCCCCCACAAT3′.

The U1 + 1T snRNA expression vector was prepared as previously described [17].

All vectors were validated by direct sequencing.

Cell culture and transient transfection of Baby Hamster Kidney (BHK) cells were conducted as described [2,14].

2.3. Reverse transcription (RT), PCR and quantitative RT-PCR

Reverse transcription (RT), PCR and quantitative RT-PCR, were conducted as described [13,17,18] using the forward primers 5F (5′GAGAACGGCGGCTGTGAG3′) and 6F (5′GTTCCTCCAGTTCTTGATTTTGTCG3′) and the reverse primers 7R (5′GTTCCTCCAGTTCTTGATTTTGTCG3′) or 7R-FAM (5′cgacaCCAGTTCTTGATTTT GTcG3′).

For quantitative PCR (qPCR), primers 5F and 7R were used to amplify all FVII transcripts whereas primers 5F and 6/7R (5′ACCAACAACAGGACCTGCCA3′), targeting the exon 6–7 junction, were exploited to amplify those including exon 6.

2.4. Measurement of secreted FVII protein and activity levels in conditioned media

Evaluation of secreted FVII protein levels by ELISA was conducted as described [2,14]. Besides the standard curve with a serial dilution of pooled normal plasma (PNP), a reference curve with a serial dilution of recombinant Wt-FVII in conditioned media was made. The detection limit of the ELISA was 1 ng/ml FVII.

For Western blotting analysis, conditioned medium was incubated 5 min at 95 °C and run on 4–12% SDS-PAGE (NuPAGE Bis-Tris gel, Invitrogen ®; Carlsbad, CA). Proteins were transferred onto a 0.2 μm nitrocellulose membrane (Whatman®, Dassel, Germany), which was blocked overnight with PBS buffer supplemented with 0.1% Tween-20 (PBS-T) and 5% low fat dry milk (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Membranes were then incubated for 4 h at room temperature with the anti-human FVII HRP-conjugated antibody (Pierce® Factor VII (HRP) Polyclonal Sheep, 2 mg/ml, Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) diluted 1:2500 in blocking buffer. The Supersignal® West Femto reagent (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) was exploited for detection. The FVII protein purified from human plasma (pdFVII) was purchased from Haematologic Technologies Inc (Essex Junction, VT, USA) at the concentration of 2.6 mg/ml. Upon dilution, it was used as reference in our experiments.

The activity of FVII variants toward its natural FVII substrate, factor X (FX), was evaluated in plasma systems by adding recombinant FVII to FVII-deficient plasma (George King, Bio-Medical Inc., USA). Generation of activated FX (FXa) was monitored over time by exploiting a specific FXa fluorogenic substrate (MeSO2-D-CHA-Gly-Arg-AMCAcOH; American Diagnostica Inc., Greenwich, CT, USA)[14].

Serial dilutions of rFVII-wt were used to optimize the assay that, in our hand, enabled the detection of the activity produced by as low as 0.15 ng/ml of Wt-FVII.

Media from cells transiently transfected with the empty pcDNA3 vector were used as negative control in all assays.

3. Results and discussion

In this study, we investigated the IVS6 + 1G > T mutation in the 5'ss of F7 intron 6 (Fig. 1A), which was found to be associated to life-threatening bleeding in two homozygous patients (PFVII-T3, PFVII-T4).

The IVS6 + 1G > T mutation was also found in doubly heterozygous condition with the W424X nonsense mutation [2], in a severe patient who experienced intracranial bleeding, or the C389G substitution, in a mildly affected patient.

The IVS6 + 1G > T mutation in PFVII-T3 and PFVII-T4 was associated to a very severe coagulation phenotype characterized by undetectable FVII protein plasma levels (< 0.5% of pooled normal plasma), which did not correspond to any measurable coagulant activity.

Altogether these data in vivo are consistent with the extreme deficiency of circulating FVII caused by the IVS6 + 1G > T change.

3.1. Aberrant FVII splicing patterns associated to the IVS6+1G>T mutation

To investigate the residual FVII expression associated to the IVS6 + 1G > T mutation, if any, we focused the study on the mRNA level, which takes advantage of highly sensitive amplification techniques. Since investigation of FVII splicing patterns in patient's liver, the physiological site of expression, or in extra-hepatic tissues, was not feasible, splicing mechanisms were sought by expressing the normal (pIVS6-wt) and mutated (pIVS6 + 1T) F7 minigenes in mammalian cells. This approach has been successfully exploited to study splicing mutations in F7 [13,19] as well as in many other human disease genes [8,20,21]. The splicing patterns observed in vitro mirrored those detected in available patient's tissues [8,13,20].

While the expression of pIVS6-wt produced correctly processed FVII transcripts, the pIVS6 + 1T drove the synthesis of a FVII mRNA lacking exon 6 (Fig. 1B, form II), frame-shifted from codon 190 and not compatible with measurable FVII levels in plasma.

The presence of correct FVII transcripts associated to the IVS6 + 1G > T mutation were evaluated by labelling of RT-PCR products (Fig. 2A). Denaturing capillary electrophoresis of fluorescently labelled RT-PCR fragments, even upon column overloading, did not reveal normal FVII mRNA forms (form I, 324 bp).

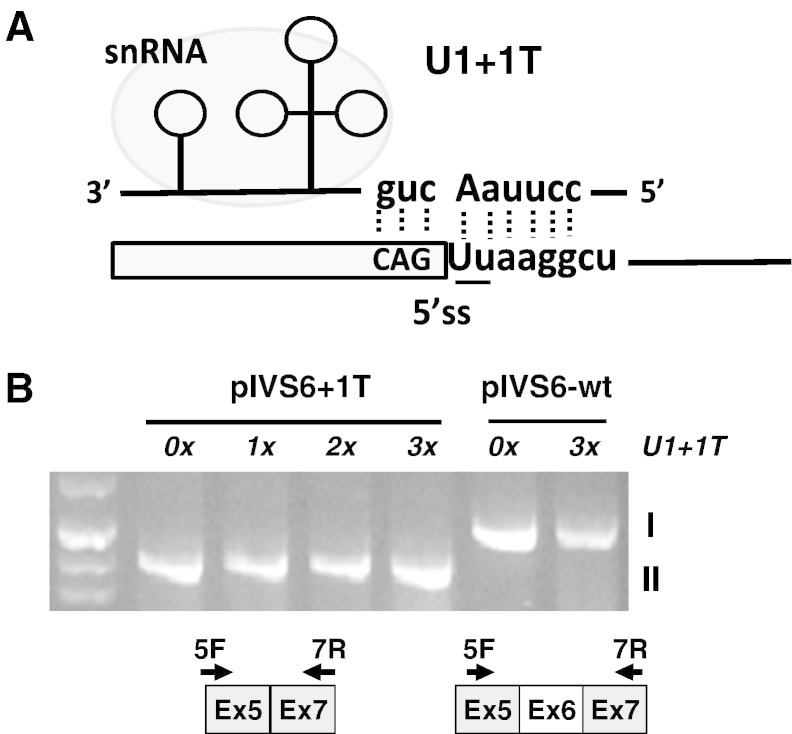

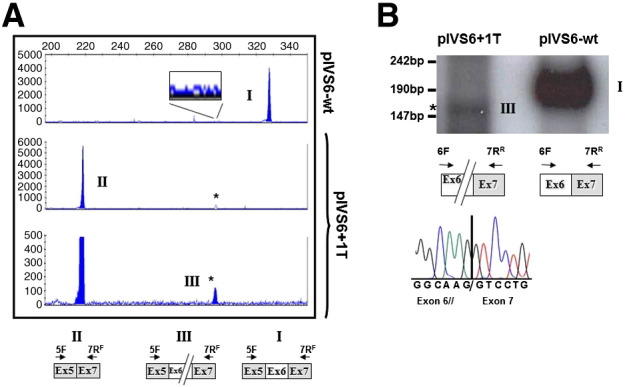

Fig. 2.

Investigation of residual levels of correct mRNA forms.

(A) Separation on a denaturing capillary system (automated ABI-3100) of fluorescently labelled RT-PCR products (1 μl of 1:100 diluted reaction) obtained from total RNA of cells expressing pIVS6-wt (top) or the pIVS6 + 1T. The fragment sizes of the normal (I) and exon 6 skipped (II) transcript forms were 324 bp and 214 bp, respectively.

The magnified lower panel highlights the 30 bp deleted FVII transcript (III; asterisk).

The inset in the upper panel reports a magnified view of the chromatogram.

The scheme of transcripts and of primers (arrows) is depicted at the bottom.

(B) Radioactively labelled RT-PCR products (12% polyacrylamide gel).

The normal (I) and the 30 bp deleted (III; asterisk) FVII transcripts are indicated. The scheme of transcripts and of primers (arrows) is reported at the bottom together with the sequence of the 30 bp deleted transcript.

Neither radioactive labelling of RT-PCR products (Fig. 2B) nor qRT-PCR revealed normal transcripts. Remarkably, the exon 6 skipped transcripts were still detectable upon a 1:10,000 dilution, thus suggesting that, if present, the levels of correct FVII transcripts associated to the mutation were below the 0.01% of the aberrant ones.

In the earliest splicing step, the donor splice site is recognized by the spliceosomal small nuclear ribonucleoprotein U1-snRNP [22], and particularly by its RNA component (U1-snRNA). It has been demonstrated that U1-snRNA variants engineered to restore the complementarity with defective donor splice sites can re-direct splicing to the correct junction [17,21,23]. Although mutations that disrupt the invariant GT dinucleotide of 5'ss are usually not rescued [23], the c.165 + 1G > T mutation in the FANCC gene was successfully treated [8]. It must be noticed that in the latter case, the + 1G > T change does not completely abrogate splicing and it is compatible with synthesis of correct transcripts.

To further exclude the possibility that the IVS6 + 1G > T in F7 gene also creates a leaky 5'ss, we designed and created a modified U1-snRNA (U1 + 1T) targeting the mutated IVS6 5'ss (Fig. 3A). Even upon over-expression, the U1 + 1T failed to produce traces of normal FVII mRNA (Fig. 3B). Since the mutation-specific U1 + 1T did not restore normal splicing, we infer that the IVS6 + 1G > T mutation likely affects subsequent steps of the splicing process.

Fig. 3.

Effect of the mutation-specific U1 + 1 T snRNA on FVII mRNA splicing.

(A) Schematic representation of the exon 6–intron 6 splicing junction and of the U1-snRNA secondary structure. The 5′ tail of U1-snRNAs was engineered to bind to the mutated IVS6 5'ss, and their sequence complementary is shown.

(B) RT-PCR products from cells expressing the pIVS6-wt and pIVS6 + 1T upon cotransfection with increasing molar amounts (0–3 ×) of the mutation-specific pU1 + 1T (2% agarose gel).

The scheme of transcripts (I, II and III as in Fig. 1C), and of primers (arrows), is depicted at the bottom.

Although the production of trace levels of correct transcripts in patients’ liver cannot be completely excluded, the overall data support the abrogation of the IVS6 donor splice site by the IVS6 + 1G > T change.

We sought for the presence of alternative splicing patterns, able to rescue FVII expression and prevent perinatal lethality. Chromatograms (Fig. 2A) and films (Fig. 2B) identified an additional FVII transcript (8 ± 2% of exon 6 skipped forms) in pIVS6 + 1T expressing cells. Sequencing of nested-PCR products, with primers 6F and 7R, to avoid amplification of the abundant exon 6 skipped forms (Fig. 2B) revealed the presence of a 30 bp deleted mRNA originating from usage of a cryptic 5'ss in exon 6 (Fig. 1A). Differently, the cryptic site was silent in the pIVS6-wt context, as indicated by the undetectable levels of the 30 bp deleted mRNA either by denaturing capillary electrophoresis (Fig. 2A, inset) or radioactive labelling (Fig. 2B). These results were consistent with the consensus value (CV) of F7 5'ss predicted by computational analysis (www.fruitfly.org). In particular, the cryptic site in exon 6 (CV 0.76) was used when the canonical 5'ss, the strongest (CV 1.0) among all canonical 5'ss of F7 gene (average CV 0.86), is abrogated by the IVS6 + 1G > T mutation (CV 0.0) (Fig. 1A). Noticeably, the CV of the exon 6 cryptic 5'ss is, within the mutated allele, the highest in the F7 gene region spanning exon 5 through 7. Computational analysis also revealed an additional potential 5'ss (CV 0.56) in intron 6 at position + 92, which was not used in any of the experimental conditions tested.

3.2. Expression of the in-frame deleted FVII mRNA accounts for residual function

The 30 bp in-frame deleted FVII mRNA would encode for a protein lacking 10 residues (Val218-Gln227; chymotrypsin numbering 21–30) in the activation domain of the serine protease (Fig. 4A). The deletion removes an intra-chain disulphide bridge (Cys219–Cys224), but not the Arg212-Ile213 activation site. Remarkably, in the zymogen (PDB ID: 1JBU) or in the activated (PDB ID: 1QFK) FVII crystallographic structures the deleted residues belong to a surface exposed loop (Fig. 4B) that is present in all serine proteases [24]. However, its primary sequence is, with the exception of the proline 225 (c23), moderately degenerated. Expression studies were undertaken to assess whether the deletion of this region was compatible with FVII secretion and function. Upon an 8X concentration of conditioned medium, the recombinant FVIIΔ218-227 variant was detectable by ELISA (2 ng/ml) and Western blotting (Fig. 4C).

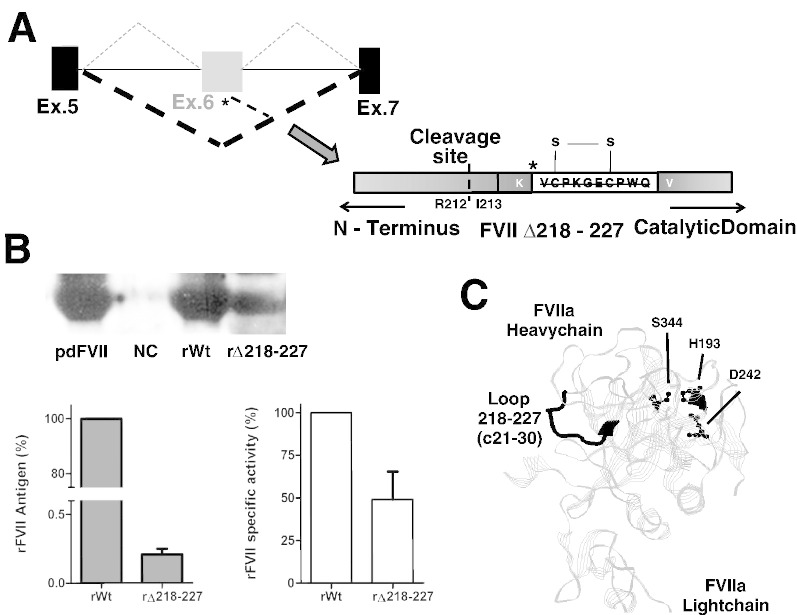

Fig. 4.

Residual protein and activity levels of the FVII Δ218-227 variant.

(A) Schematic representation of (upper panel) the splicing events observed in the wt (dotted line) or in the IVS6 + 1G > T mutant (bold dotted line), and of (lower panel) the deleted FVII Δ218-227 variant. The asterisk indicates the 5'ss cryptic site or the in-frame K217-V228 junction.

(B) Strand diagram showing three-dimensional structure of human activated FVII.

The deleted region of the activation domain is highlighted in black whereas the catalytic triad is reported in ball-and-stick. This is a RasMol presentation of file1QFK from the Brookhaven Protein Data Bank.

(C) FVII protein (WB, left panel), antigen (ELISA, middle panel) and specific activity (right panel) levels in conditioned medium from cells expressing the rFVII-wt or the rFVII Δ218-227 variants, or transfected with the empty pcDNA3 (NC).

Conditioned media were concentrated through the Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter devices (cut-off 30 kDa, Millipore, Carrigtwohill, County Cork, Ireland).

For Western blotting analysis, the rFVII-wt was loaded at a concentration (4 ng/ml) comparable to that of the rFVIIΔ218-227 variant. The plasma derived FVII (pdFVII) was loaded as control at the concentration of 4 ng/ml.

To assess the specific activity, fluorogenic FXa generation assays were conducted in FVII depleted plasma supplemented with rFVII-wt or of rFVIIΔ218-227. Results, obtained in three independent experiments conducted in duplicate, are expressed as % of the relative rFVII-wt.

The assessment of its activity, which is essential to evaluate the residual coagulant properties, was carried out by functional assays with the recombinant protein added to FVII-deficient plasma, to better mimic the physiological conditions. In these assays, we measured the activity of FVII toward its physiologic substrate, factor X (FX), by exploiting a fluorogenic substrate for activated FX, which permits high sensitivity to very low activity levels [2,14]. Interestingly, the specific activity of the deleted FVII resulted to be approximately half of that of the rFVII-wt (48 ± 16%) (Fig. 4C), thus indicating that the deletion in the activation domain is compatible with FVII activation and catalytic function. Among the over 250 mutations so far reported in FVII deficiency (http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk), none was identified in this region, thus further supporting our observation.

3.3. Residual coagulation function in plasma from the IVS6+1G>T homozygous patient

A thumbnail calculation based on the results from the mRNA (~ 8% of skipped transcript) and functional protein (~ 0.1% of normal) studies predicts that the IVS6 + 1G > T mutation produces approximately 0.01% of functional FVII as compared to the normal. Both empirical and mathematical modelling studies suggested that this concentration should be sufficient to induce coagulation [25]. Therefore, we evaluated the coagulation cascade efficiency in plasma from the IVS6 + 1G > T homozygote (PFVII-T3) by the real-time measurement of the generation of thrombin, the last effector of the coagulation cascade [15]. This assay, albeit with the limitations of a global assay in testing the influence of a single protein, takes advantage of the amplification features of the pathway and might unravel the functional impact of even very low FVII activity, far below the direct detection limit in plasma.

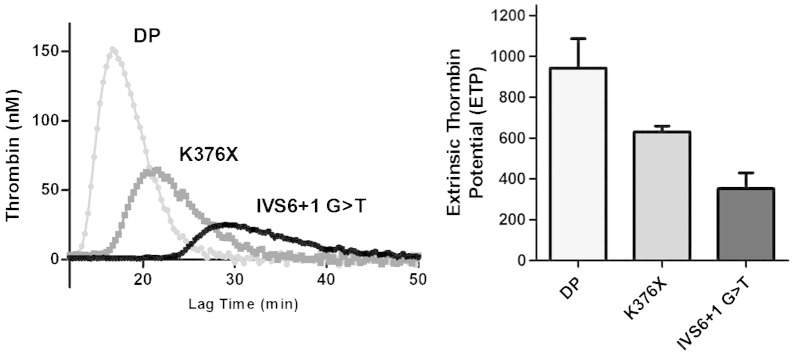

Intriguingly, upon coagulation triggering with tissue factor, the obligatory cofactor of FVII [26], the thrombin generation activity in plasma from patient PFVII-T3 was appreciable (352 ± 55 nM)(Fig. 5). This extent of thrombin generation was smaller than in plasma from a patient homozygous for the nonsense mutation K376X (630 ± 20 nM) that accounts for residual FVII function by the mechanism of ribosome readthrough [2].

Fig. 5.

Thrombin generation activity in plasma from the PFVII-T3.

Thrombin generation curves in plasma from the IVS6 + 1G > T (PFVII-T3) and the K376X homozygotes, and in the commercial FVII-deficient plasma (DP, George King, Bio-Medical Inc., USA).

The Extrinsic Thrombin Potential in the different plasma samples is reported in the histogram and is expressed as nM thrombin.

Taken together these data support the association of the IVS6 + 1G > T mutation with the lowest FVII function ever described in FVII deficiency.

3.4. Conclusions

Overall data at the mRNA and protein level highlight poorly recognized mechanisms and effects of aberrant splicing. The IVS6 + 1G > T change, because of the favourable gene sequence context—i.e. presence of an in-frame cryptic donor splice site—abrogates correct splicing but also induces the synthesis of an in-frame alternative FVII transcript. This mRNA encodes for a protein that is scarcely secreted but, due to a favourable protein context—a poorly conserved sequence in the activation domain of serine proteases—possesses a remarkable catalytic activity. The in silico splicing pattern prediction, the coherent results from expression studies and thrombin generation in patient's plasma make this aberrant splicing event likely to occur in vivo. These mechanistic features are compatible with traces of FVII expression, among the lowest levels reported in human diseases. Being FVII the enzyme triggering the amplification cascade process, its residual expression might ensure a minimal hemostasis and reverted an otherwise perinatally lethal genetic condition.

Contributors

N.C., D.B, A.B., performed functional assays in plasma and expression studies; I.M, performed denaturing capillary electrophoresis analyses; A.C., W.S., visited the patients, performed coagulation assays and sampled the patients; G.M., analyzed data and revised the paper; F.P., conducted experiments with modified U1-snRNA; F.B., M.P., designed the experimental strategies, analyzed results and wrote the paper.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The financial support of Telethon-Italy (GGP09183) (N.C., D.B., A.B, F.P., M.P.), Ministero dell'Università e della Ricerca (MIUR)-Progetti di Ricerca di Interesse Nazionale (PRIN) (D.B., M.P.), AIFA (AIFA 2008—Bando per le malattie rare—Progetto RF-null-2008-1235892) (M.P., F.B.), University of Ferrara (N.C., D.B., F.B.) and Fondazione CARIFE (M.P., A.B., F.B.) is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Rospert S., Rakwalska M., Dubaquié Y. Polypeptide chain termination and stop codon readthrough on eukaryotic ribosomes. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2005;155:1–30. doi: 10.1007/3-540-28217-3_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinotti M., Rizzotto L., Pinton P., Ferraresi P., Chuansumrit A., Charoenkwan P., Marchetti G., Rizzuto R., Mariani G., Bernardi F., International Factor VII Deficiency Study Group Intracellular readthrough of nonsense mutations by aminoglycosides in coagulation factor VII. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2006;4:1308–1314. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pacho F., Zambruno G., Calabresi V., Kiritsi D., Schneider H. Efficiency of translation termination in humans is highly dependent upon nucleotides in the neighbourhood of a (premature) termination codon. J. Med. Genet. 2011;48:640–644. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2011.089615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krawczak M., Thomas N.S., Hundrieser B., Mort M., Wittig M., Hampe J., Cooper D.N. Single base-pair substitutions in exon–intron junctions of human genes: nature, distribution, and consequences for mRNA splicing. Hum. Mutat. 2007;28:150–158. doi: 10.1002/humu.20400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aebi M., Hornig H., Weissmann C. 5′ cleavage site in eukaryotic pre-mRNA splicing is determined by the overall 5′ splice region, not by the conserved 5′ GU. Cell. 1987;50:237–246. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90219-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen M., Manley J.L. Mechanisms of alternative splicing regulation: insights from molecular and genomics approaches. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:741–754. doi: 10.1038/nrm2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tazi J., Bakkour N., Stamm S. Alternative splicing and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1792:14–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartmann L., Neveling K., Borkens S., Schneider H., Freund M., Grassman E., Theiss S., Wawer A., Burdach S., Auerbach A.D., Schindler D., Hanenberg H., Schaal H. Correct mRNA processing at a mutant TT splice donor in FANCC ameliorates the clinical phenotype in patients and is enhanced by delivery of suppressor U1 snRNAs. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;87:480–493. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mariani G., Herrmann F.H., Dolce A., Batorova A., Etro D., Peyvandi F., Wulff K., Schved J.F., Auerswald G., Ingerslev J., Bernardi F., International Factor VII Deficiency Study Group Clinical phenotypes and factor VII genotype in congenital factor VII deficiency. Thromb. Haemost. 2005;93:481–487. doi: 10.1160/TH04-10-0650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furie B., Furie B.C. Molecular and cellular biology of blood coagulation. N. Engl. J. Med. 1992;326:800–806. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199203193261205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosen E.D., Chan J.C., Idusogie E., Clotman F., Vlasuk G., Luther T., Jalbert L.R., Albrecht S., Zhong L., Lissens A., Schoonjans L., Moons L., Collen D., Castellino F.J., Carmeliet P. Mice lacking factor VII develop normally but suffer fatal perinatal bleeding. Nature. 1997;390:290–294. doi: 10.1038/36862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McVey J.H., Boswell E.J., Takamiya O., Tamagnini G., Valente V., Fidalgo T., Layton M., Tuddenham E.G. Exclusion of the first EGF domain of factor VII by a splice site mutation causes lethal factor VII deficiency. Blood. 1998;92:920–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinotti M., Toso R., Redaelli R., Berrettini M., Marchetti G., Bernardi F. Molecular mechanisms of FVII deficiency: expression of mutations clustered in the IVS7 donor splice site of factor VII gene. Blood. 1998;92:1646–1651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinotti M., Etro D., Bindini D., Papa M.L., Rodorigo G., Rocino A., Mariani G., Ciavarella N., Bernardi F. Residual factor VII activity and different hemorrhagic phenotypes in CRM(+) factor VII deficiencies (Gly331Ser and Gly283Ser) Blood. 2002;99:1495–1497. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.4.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemker H.C., Giesen P., Al Dieri R., Regnault V., de Smedt E., Wagenvoord R., Lecompte T., Béguin S. Calibrated automated thrombin generation measurement in clotting plasma. Pathophysiol. Haemost. Thromb. 2003;33:4–15. doi: 10.1159/000071636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marchetti G., Caruso P., Lunghi B., Pinotti M., Lapecorella M., Napolitano M., Canella A., Mariani G., Bernardi F. Vitamin K-induced modification of coagulation phenotype in VKORC1 homozygous deficiency. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2008;6:797–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.02934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinotti M., Rizzotto L., Balestra D., Lewandowska M.A., Cavallari N., Marchetti G., Bernardi F., Pagani F. U1-snRNA-mediated rescue of mRNA processing in severe factor VII deficiency. Blood. 2008;111:2681–2684. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-117440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bertolucci C., Cavallari N., Colognesi I., Aguzzi J., Chen Z., Caruso P., Foá A., Tosini G., Bernardi F., Pinotti M. Evidence for an overlapping role of CLOCK and NPAS2 transcription factors in liver circadian oscillators. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008;28:3070–3075. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01931-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borensztajn K., Sobrier M.L., Fischer A.M., Chafa O., Amselem S., Tapon-Bretaudiere J. Factor VII gene intronic mutation in a lethal factor VII deficiency: effects on splice-site selection. Blood. 2003;102:561–563. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsuji-Wakisaka K., Akao M., Ishii T.M., Ashihara T., Makiyama T., Ohno S., Toyoda F., Dochi K., Matsuura H., Horie M. Identification and functional characterization of KCNQ1 mutations around the exon 7-intron 7 junction affecting the splicing process. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1812:1452–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Susani L., Pangrazio A., Sobacchi C., Taranta A., Mortier G., Savarirayan R., Villa A., Orchard P., Vezzoni P., Albertini A., Frattini A., Pagani F. TCIRG1-dependent recessive osteopetrosis: mutation analysis, functional identification of the splicing defects, and in vitro rescue by U1 snRNA. Hum. Mutat. 2004;24:225–235. doi: 10.1002/humu.20076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horowitz D.S., Krainer A.R. Mechanisms for selecting 5′ splice sites in mammalian pre-mRNA splicing. Trends Genet. 1994;10:100–106. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(94)90233-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pinotti M., Dal Mas A., Bernardi F., Pagani F. RNA-based therapeutic approaches for coagulation factor deficiencies. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2011;9:2143–2152. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greer J. Comparative modeling methods: application to the family of the mammalian serine proteases. Proteins. 1990;7:317–334. doi: 10.1002/prot.340070404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawson J.H., Kalafatis M., Stram S., Mann K.G. A model for the tissue factor pathway to thrombin. I. An empirical study. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:23357–23366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rapaport S.I., Rao L.V. The tissue factor pathway: how it has become a "prima ballerina". Thromb. Haemost. 1995;74:7–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]