Abstract

GSK961081 is a bifunctional molecule demonstrating both muscarinic antagonist and β-agonist activities.

This was a 4-week, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, placebo and salmeterol controlled parallel group study. Doses ranging across three twice-daily doses and three once-daily doses were assessed in moderate and severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients. Trough forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) at day 29 was the primary end-point. At days 1 and 28, 12-h FEV1 spirometry was performed in all patients. A subset of patients underwent complete 24-h spirometry at day 28.

The study recruited 436 patients. GSK961081 showed statistically and clinically significant differences from placebo in all doses and regimens for trough FEV1 on day 29 (155–277 mL). The optimal total daily dose was 400 μg, either as 400 μg once daily or as 200 μg twice daily, with an improvement in day 29 trough FEV1 of 215 mL and 249 mL, respectively. Other efficacy end-points also showed improvement. No effects were observed on glucose, potassium, heart rate, blood pressure and no dose–response effect was seen on corrected QT elongation.

This study showed that GSK961081 is an effective bronchodilator in COPD and appeared to be safe and well tolerated.

Short abstract

Phase IIb study results showed the muscarinic antagonist–β-agonist GSK961081β is an effective bronchodilator in COPD http://ow.ly/lh7mU

Introduction

Pharmacological management of chronic, stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is primarily aimed at improving symptoms and quality of life, optimising lung function, reducing exacerbations and improving exercise tolerance [1, 2]. Inhaled bronchodilators, including β2-agonists and antimuscarinics, are the mainstays of therapy in patients diagnosed with COPD [1].

While the mechanism of dual bronchodilators is not fully understood, addition of a β2- agonist to an antimuscarinic results in greater bronchodilation in the airways than either component alone. Mechanistically it is thought that the addition of a β2-agonist decreases the release of acetylcholine (ACh) through the modulation of cholinergic neurotransmission by pre-junctional β2-adrenergic receptors (β2-ARs), amplifying the bronchial smooth muscle relaxation induced by the muscarinic antagonist. Secondly, the addition of a muscarinic antagonist reduces the bronchoconstrictor effects of ACh, whose release has been modified by the β2-agonist, and thereby amplifies the bronchodilation elicited by the β2-agonist through the direct stimulation of smooth muscle β2-ARs [3].

Clinical research confirms that addition of β2-agonist to a muscarinic antagonist is more effective at improving lung function and patient-centred outcomes than either of the components alone and that there are no untoward safety issues [4–9]. In studies evaluating the combined use of tiotropium with formoterol or salmeterol, the number and type of reported adverse events were similar when comparing co-administration of monotherapies with individual treatments for up to 1 year [6–10].

As of 2012 there is currently no licensed combination of long-acting β-agonist/long-acting muscarinic antagonist, either as two separate drugs in the same device or as a single molecule. Compounds with both muscarinic antagonist and β-agonist activity offer a single pharmacokinetic profile for both pharmacological activities, potential for maximising the synergy between the two mechanisms, and a simpler technical and clinical development pathway compared to coformulation of two compounds [11]. GSK961081 is a bifunctional molecule and has muscarinic antagonist activity at one end of the molecule, separated from β2-agonist activity by an inert linker portion. The bifunctional nature of GSK961081 has been demonstrated in vitro [12] and in vivo in a guinea pig bronchoprotection model [13]. In a study in healthy volunteers with and without propranolol (β2-adrenergic receptor blockade) GSK961081 showed activity at both receptors, with the β2-agonist effect being longer lasting than the antimuscarinic activity [14]. In a small, 14-day crossover study in 50 moderate COPD patients, GSK961081 was found to be safe and well tolerated and showed bronchodilation versus placebo that was comparable to tiotropium plus salmeterol [15].

This study was designed to determine the bronchodilator effects of GSK961081, the dose and dosing interval (using trough FEV1 at day 29 as the primary outcome), as well as safety and tolerability in moderate and severe COPD patients. The study evaluated three once-daily doses and three twice-daily doses, a placebo arm and an active comparator, salmeterol.

Methods

Study design

This was a 4-week, phase IIb, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, placebo- and active-controlled, parallel-group, dose-interval and dose-ranging study. After the screening visit and a 7-day run-in period, eligible patients were randomised and entered a 28-day treatment period. Clinic visits were on days 1, 2, 14, 28 and 29, plus two telephone contacts on day 7 and 7 days after the last clinic visit.

Patients enrolled at centres with overnight accommodation had 24-h serial spirometry assessed on day 28.

Sample size calculations

Sample size calculations were based on the primary efficacy end-point and the assumptions are shown in the online supplementary material S1. Eligible patients were randomised to one of eight arms, with once-daily doses of 100 μg, 400 μg or 800 μg or twice-daily doses of 100 μg, 200 μg or 400 μg of GSK961081, 50 μg salmeterol twice daily or placebo (table 1), in a ratio of 2:2:2:2:2:2:2:3. Patients were provided with two Diskus inhalers (GlaxoSmithKline, Ware, UK and Stevenage, UK), one for morning use and one for evening use. For the once-daily regimen the evening inhaler was a placebo. The study was stratified by reversibility to salbutamol and inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) use.

Table 1– Patient demographics and clinical characteristics at screening.

| Placebo | Salmeterol | GSK961081 | ||||||

| Twice daily | Once daily | |||||||

| 100 μg | 200 μg | 400 μg | 100 μg | 400 μg | 800 μg | |||

| ITT subjects n | 81 | 47 | 52 | 50 | 54 | 50 | 50 | 52 |

| Age years | 63±7 | 61±7 | 62±9 | 61±9 | 63±8 | 63±9 | 62±8 | 61±9 |

| Male % | 70 | 62 | 71 | 64 | 70 | 64 | 52 | 67 |

| BMI kg·m−2 | 26±4 | 26±4 | 26±4 | 26±4 | 26±4 | 26±4 | 27±4 | 26±4 |

| Current smoker % | 44 | 62 | 54 | 66 | 46 | 40 | 54 | 48 |

| Concurrent ICS use % | 59 | 55 | 58 | 60 | 56 | 60 | 54 | 56 |

| Reversible to salbutamol# % | 33 | 36 | 33 | 34 | 37 | 32 | 26 | 31 |

| FEV1 L¶ | 1.56±0.53 | 1.48±0.47 | 1.55±0.50 | 1.59±0.46 | 1.62±0.47 | 1.63±0.49 | 1.53±0.45 | 1.56±0.42 |

| FEV1 % pred¶ | 49±11 | 48±10 | 50±10 | 51±10 | 51±10 | 53±10 | 52±10 | 51±10 |

| FEV1 % reversibility | 12±11 | 12±16 | 12±14 | 13±13 | 14±11 | 11±12 | 12±12 | 13±13 |

| FEV1/FVC ratio¶ | 0.49±0.10 | 0.50±0.10 | 0.51±0.09 | 0.50±0.09 | 0.50±0.10 | 0.50±0.10 | 0.52±0.10 | 0.51±0.09 |

Data are presented as mean±sd, unless otherwise stated. ITT: intent-to-treat; BMI: body mass index; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; % pred: % predicted; FVC: forced vital capacity. #: reversibility to salbutamol defined as increase in FEV1 of 200 mL and 12% following salbutamol administration; ¶: post-salbutamol measurements.

Study patients

This study included both current and former smokers aged ≥40 years, who had a smoking history of ≥10 pack-years. Patients had a clinical diagnosis of moderate-to-severe stable COPD (post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) <70% and FEV1 ≥30% and ≤70% predicted), according to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III [16]. Patients on a stable dose of ICS were allowed to participate in the study.

A current diagnosis of asthma was exclusionary. Due to the presence of vocal fold erosions in dogs given high doses of GSK961081, patients who were symptomatic (or had a documented history of) laryngopharyngeal reflux, extraoesophageal reflux, posterior laryngitis or laryngopharyngeal ulcerations and erosions were also excluded. This was to ensure that patients with pre-existing throat problems would not confound the potential to identify any new instances of throat irritation during the study. Further characteristics of the COPD population are shown in the online supplementary material (S2).

The study was approved by the medical ethical committees of the participating centres, and all patients gave their written informed consent. The study was conducted according to the declaration of Helsinki using Good Clinical Practice.

Study assessments

Efficacy

Spirometry was carried out using the Vitalograph (Biomedical Systems (BMS), Brussels, Belgium) (online supplementary material (S3)). Over-reading of traces was also performed by BMS. A subject was reversible if they increased their pre-salbutamol FEV1 by ≥200 mL and ≥12% 15 min after the administration of 400 μg of salbutamol at the screening visit.

Safety assessments

The incidence and severity of all adverse events was recorded in the electronic case report form. Details for ECGs, blood chemistry and vital signs are in the online supplementary material (S4). Data were collected for any patients who reported throat symptoms for 7 days or longer, including hoarseness of voice, sore throat, lump in throat, difficulty in swallowing or any abnormal sensations in the throat. These patients also underwent a protocol-defined flexible laryngoscopy examination by a specialist.

End-points

The primary end-point for the study was the change from baseline in trough FEV1 at day 29. Trough was defined as the mean of 11- and 12-h measurement after the evening dosing on day 28.

Secondary end-points included the weighted mean for 0–24-h serial FEV1 measurements in the subset of patients with overnight spirometry, serial FEV1 on day 28 at each time-point up to 24 h post-dose in the subgroup of patients undergoing overnight spirometry and serial morning post-dose FEV1 0–12 h on day 1 and day 28 in the whole cohort.

Statistical analysis

The primary end-point was analysed using a repeated measures model, with fixed effects for baseline FEV1, reversibility, concurrent ICS use, sex, age, smoking status (at screening), treatment, study day, treatment by study day interaction and whether or not the patient participated in 24-h spirometry assessments. In order to preserve an overall α level of 5% inference versus placebo a closed sequential testing procedure was used within each dosing regimen at a significance level of 2.5%, initially comparing the highest dose with placebo. Subsequent comparisons at lower doses continued in a step-down manner only if the preceding comparison was significant. Inferences for secondary end-points were not adjusted for multiplicity. A post hoc analysis was carried out to provide inferences between all groups and salmeterol.

Results

Cohort characteristics

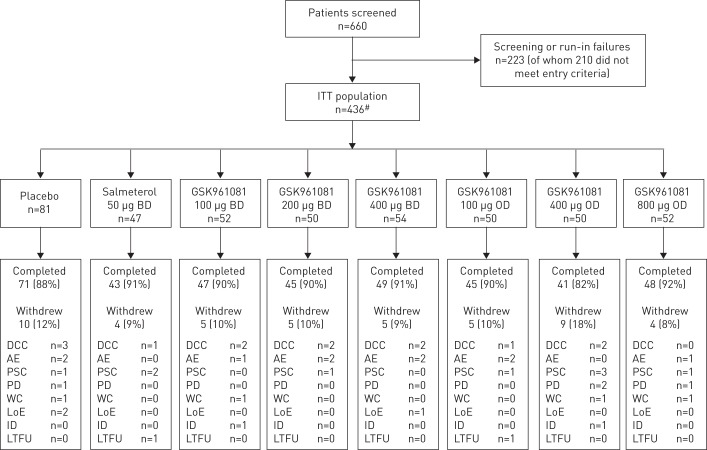

437 patients were randomised into the study. One patient received no investigational product and was withdrawn, giving a modified intent-to-treat population of 436 patients from nine countries and 49 sites, with 46% of patients in the overnight cohort. Demographic characteristics of the study population can be found in table 1 and the disposition of patients in figure 1.

Figure 1–

Subject disposition consort diagram. ITT: intent-to-treat; BD: twice daily; OD: once daily; DCC: did not meet continuation criteria; AE: adverse event; PSC: protocol-defined stopping criteria; PD: protocol deviation; WC: withdrew consent; LoE: lack of efficacy; ID: investigator discretion; LTFU: lost to follow-up. #: 437 subjects were randomised, but one subject did not receive any randomised medication, leaving 436 for the ITT population.

For the primary end-point (morning trough FEV1 at day 29), GSK961081 at all doses was significantly different from placebo (p<0.001) (table 2). Differences for the once daily doses ranged from 155 mL (100 μg) to 277 mL (800 μg) and differences for the twice daily doses ranged from 173 mL (100 μg) to 258 mL (400 μg). When looking at treatment effects versus placebo within the pre-defined strata, FEV1 improvements were generally greater for patients who were reversible to salbutamol and greater for patients who were not concurrent ICS users (online supplementary table S1). During the study the trough FEV1 increased over the first 14 days and remained constant to 28 days (online supplementary table S2).

Table 2– Results for least squares mean change from baseline trough forced expiratory volume in 1 s on day 29.

| Treatment | Subjects n | Change from baseline mL | Difference from placebo mL | p-value versus placebo | Difference from salmeterol mL# | p-value versus salmeterol# |

| Placebo | 71 | -7 | ||||

| Salmeterol | 43 | 71 | 77 (1–153) | 0.046# | ||

| GSK961081 | ||||||

| Twice daily | ||||||

| 100 μg | 47 | 167 | 173 (100–247) | <0.001 | 96 (14–179) | 0.023 |

| 200 μg | 46 | 243 | 249 (175–323) | <0.001 | 172 (89–255) | <0.001 |

| 400 μg | 49 | 251 | 258 (185–330) | <0.001 | 181 (98–263) | <0.001 |

| Once daily | ||||||

| 100 μg | 45 | 148 | 155 (80–229) | <0.001 | 78 (-7–162) | 0.071 |

| 400 μg | 41 | 209 | 215 (139–291) | <0.001 | 138 (53–223) | 0.002 |

| 800 μg | 48 | 270 | 277 (204–350) | <0.001 | 200 (117–282) | <0.001 |

Data are presented as least squares mean or least squares mean (95% CI), unless otherwise stated. For the primary end-point, p-values for GSK961081 doses were compared to placebo at α=0.025 due to separate closed step-down procedures. Least squares means were adjusted for age, sex, smoking status, reversibility stratum, overnight site stratum, concurrent inhaled corticosteroid use, baseline and treatment. #: inferences involving salmeterol were post hoc analyses.

The active comparator salmeterol was compared against all treatments in a post hoc analysis. In this analysis, there was a nominal statistical difference in favour of salmeterol compared to placebo (77 mL difference, p=0.046). Differences between GSK961081 doses and salmeterol ranged from 78 mL (100 μg once daily) to 200 mL (800 μg once daily), with statistically significant differences in favour of GSK961081 for all doses except 100 μg once daily (table 2).

Secondary end-points

For the subset of overnight patients (n=18–23), the 24-h weighted mean FEV1 differences from baseline at day 28 were statistically significant compared to placebo (p<0.001) for all doses and regimens over the 24-h time period, ranging from 226 mL (100 μg twice daily) to 335 mL (800 μg once daily) (table 3). Salmeterol had a weighted mean improvement of 85 mL, but the difference from placebo was not statistically significant.

Table 3– Weighted mean 0–24-h forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) on day 28, trough forced vital capacity (FVC) on day 29 and salbutamol use during the study.

| Weighted mean FEV1 (0–24 h) on day 28 | Trough FVC on day 29 | Salbutamol use | ||||

| Subjects | Difference mL | Subjects | Difference mL | Subjects | Difference mL | |

| Placebo | 34 | 71 | 78 | |||

| Salmeterol | 19 | 85 (-21–191)# | 43 | 120 (-3–244)# | 43 | -0.39 (-0.73– -0.05)* |

| GSK961081 | ||||||

| Twice daily | ||||||

| 100 μg | 22 | 226 (125–327)*** | 47 | 310 (190–430)*** | 50 | -0.57 (-0.89– -0.25)*** |

| 200 μg | 21 | 325 (222–428)*** | 46 | 374 (253–496)*** | 48 | -0.56 (-0.88– -0.23)*** |

| 400 μg | 24 | 307 (209–405)*** | 49 | 328 (210–446)*** | 52 | -0.74 (-1.05– -0.42)*** |

| Once daily | ||||||

| 100 μg | 18 | 246 (139–353)*** | 45 | 153 (31–275)* | 48 | -0.45 (-0.78– -0.12)** |

| 400 μg | 18 | 300 (192–407)*** | 41 | 310 (185–435)*** | 45 | -0.65 (-0.99– -0.32)*** |

| 800 μg | 23 | 335 (236–434)*** | 48 | 381 (261–500)*** | 51 | -0.62 (-0.94– -0.30)*** |

Data are presented as n or least squares mean (95% CI). Inference between salmeterol and placebo was part of a post hoc analysis. Least squares means were adjusted for age, sex, smoking status, reversibility stratum, overnight site stratum, concurrent inhaled corticosteroid use, baseline and treatment. #: not significant; *: p<0.05; **: p<0.01; ***: p<0.001.

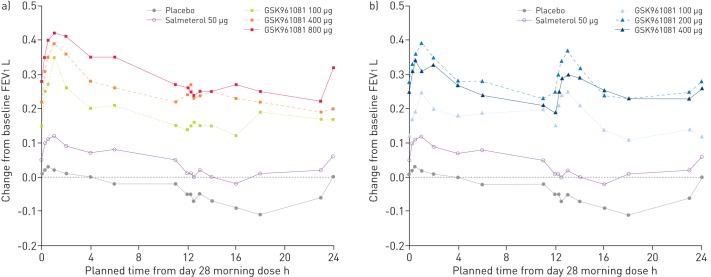

The 0–24-h FEV1 profile on day 28 (n=18–23) indicated that patients on placebo showed a reduction in FEV1 following their evening dose from 11 h onwards (fig. 2). Salmeterol also mirrored the evening drop in FEV1, as did the GSK961081 once daily doses of 100 μg and 400 μg, dropping the mean change from baseline <200 mL by the following morning. The twice daily doses of 200 μg and 400 μg induced the extra peak at 12–14 h, which ensured that the mean change from baseline remained >200 mL overnight until the following morning.

Figure 2–

Serial forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) profile over 0–24 h on day 28 in the subset of overnight subjects. a) Once daily dosage regimen; b) twice daily dosage regimen.

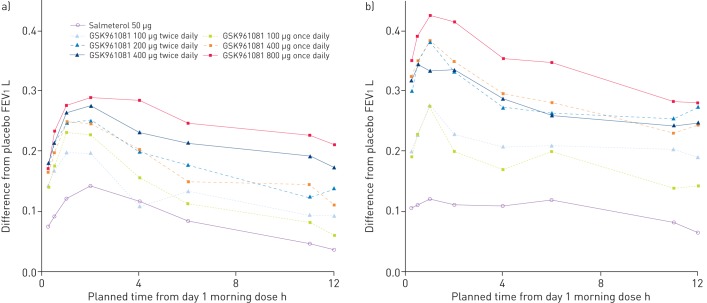

On day 1, all GSK961081 treatments gave differences over placebo which exceeded 100 mL at all time-points from 0 h to 12 h post-morning dose, with the exception of 100 μg twice daily and 100 μg once daily at 11 h and 12 h post-dose (fig. 3a). On day 28, the 200 μg twice daily, 400 μg twice daily, 400 μg once daily and 800 μg once daily GSK961081 treatments had differences over placebo which exceeded 200 mL at all time-points from 0 h to 12 h post-morning dose (fig. 3b).

Figure 3–

Serial forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) profile over 0–12 h on a) day 1 and b) day 28, in all subjects.

Other end-points

The proportion of patients showing an improvement of 100 mL within 15 min on day 1 was between 60% and 81% for GSK961081 doses (table 4), compared with 43% of patients who were treated with salmeterol. The peak FEV1 response increased from day 1 to day 28 for all doses of GSK961081, except the 100 μg once daily dose, as shown in table 4.

Table 4– Summary of onset of effect and peak forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1).

| Subjects | 15-min onset# | Peak FEV1¶ mL | ||

| Day 1 | Day 28 | |||

| Placebo | 81 | 11 (14) | 117±117 | 73±200 |

| Salmeterol | 47 | 20 (43) | 229±134 | 170±170 |

| GSK961081 | ||||

| Twice daily | ||||

| 100 μg | 52 | 34 (65) | 281±159 | 317±221 |

| 200 μg | 50 | 34 (68) | 339±188 | 399±239 |

| 400 μg | 54 | 44 (81) | 344±144 | 384±205 |

| Once daily | ||||

| 100 μg | 50 | 30 (60) | 293±176 | 279±229 |

| 400 μg | 50 | 34 (68) | 295±161 | 368±201 |

| 800 μg | 52 | 34 (65) | 392±250 | 436±300 |

Data are presented as n, n (%) or mean±sd. #: defined as achieving a 100-mL improvement from pre-dose trough to the first post-dose measurement; ¶: defined as the highest FEV1 value from 0 h to 6 h post-dose.

Trough FVC measurements for all doses of GSK961081 showed nominal statistical differences compared to placebo (p=0.014 for 100 μg once daily and p<0.001 for all other GSK961081 doses) and varied from 153 mL for GSK961081 100 μg once daily to 381 mL for the 800-μg once daily dose (table 3). Salmeterol (120 mL difference from placebo on day 29) was not statistically different from placebo.

The mean number of occasions per day of salbutamol use prior to treatment was 1.49. During the study, there was a nominal statistical difference (p<0.01) for the reduction in the number of occasions per day for the GSK961081 doses, ranging from 0.45 occasions for the 100-μg once daily dose to 0.74 for the 400-μg twice daily dose (table 3). Salmeterol showed a nominal statistical difference (p=0.026) with a reduction of 0.39 occasions per day over the study period.

Safety

One nonfatal serious adverse event was reported during treatment and required hospitalisation. This was an incident of biliary colic which was reported in a patient with a suspected past history of gallstones, in the 400-μg once daily GSK961081 treatment group, and was not considered to be related to the study drug. The incidence of adverse events is shown in table 5. GSK961081 was well tolerated, with headache, cough, dysgeusia (bad taste) and nasopharyngitis being the most common adverse events. Drug-related adverse events were reported more frequently in the GSK961081 groups than in the placebo or salmeterol arms. The most frequently reported events were cough and dysgeusia. Six exacerbations of COPD occurred during the study: four in the placebo group, and one each in the 100-μg once daily and twice daily GSK961081 groups; none required hospitalisation. There were four post-dose ECG abnormalities. One was a tachycardia in the 100-μg twice daily group, which was judged to be unrelated to the study drug by the investigator and did not lead to withdrawal. The other three were deemed treatment-related and led to withdrawal of GSK961081. A left bundle branch block and a case of Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome were diagnosed on day 1 post-dose ECGs, although review of ECGs indicated that both these abnormalities were present on ECGs obtained before dosing. In addition, a patient was withdrawn for first-degree atrioventricular block (PR 244 ms) and had a normal ECG at screening (PR 177 ms) but had a day-1, pre-dose PR interval of 215 ms.

Table 5– Most common on-treatment adverse events (≥3% incidence in any treatment group).

| Placebo | Salmeterol | GSK961081 | ||||||

| Twice daily | Once daily | |||||||

| 100 μg | 200 μg | 400 μg | 100 μg | 400 μg | 800 μg | |||

| Subjects | 81 | 47 | 52 | 50 | 54 | 50 | 50 | 52 |

| Any adverse event | 20 (25) | 8 (17) | 12 (23) | 12 (24) | 16 (30) | 16 (32) | 15 (30) | 13 (25) |

| Headache | 5 (6) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | 5 (9) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | 2 (4) | |

| Cough | 2 (2) | 2 (4) | 4 (8) | 1 (2) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | 4 (8) | |

| Dysgeusia | 2 (4) | 3 (6) | 3 (6) | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | |||

| Nasopharyngitis | 3 (4) | 1 (2) | 3 (6) | 3 (6) | 1 (2) | |||

| Back pain | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | |||||

| Dysphonia | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | |||||

| Muscle spasms | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | ||||

| Nausea | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | |||||

| Myalgia | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | |||||

| Palpitations | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | ||||||

Data are presented as n or n (%).

Heart rate and systolic and diastolic blood pressure showed little response to GSK961081. Changes in glucose and potassium were also minimal when on treatment with GSK961081. There was a pharmacological effect with GSK961081 on QT interval corrected for heart rate (QTc(F)) with a 3–4-ms increase compared to placebo on day 28. However, no dose–response relationship was apparent.

Discussion

This study was designed to assess the efficacy and safety of the novel dual bronchodilator GSK961081, in moderate and severe COPD patients. The study showed robust clinically and statistically significant improvements in trough FEV1 after 28 days of treatment and reduced the use of rescue medication. A comparison of the dosing intervals with the same total daily dose of GSK961081 at 400 μg and 800 μg demonstrated that there were no significant differences between once-daily and twice-daily dosing with respect to trough FEV1, FVC trough, rescue medication usage and safety parameters. There was a small increase in trough FEV1 as the total daily dose increased from 400 μg to 800 μg. Increases in trough FEV1 greater than the widely accepted minimal clinically important difference of 100 mL [17] for a single bronchodilator were observed for doses of 100 μg once daily and 100 μg twice daily; however, increases in trough FEV1 >200 mL (as expected for a dual bronchodilator) were not observed for these doses. Therefore, compared with a total daily dose of 400 μg, the lower daily doses would be considered as suboptimal. Using the safety data there was no clear increase in safety parameters of concern as the dose increased. Therefore we conclude that the optimum total daily dose would be 400 μg, either as a 200-μg twice-daily dose or a 400-μg once-daily dose in moderate-to-severe COPD patients.

Over the 28 days of the study, a post hoc analysis showed that GSK961081 was consistently better in improving lung function than the active comparator salmeterol. GSK961081 produced improvements of trough FEV1 by day 29, with mean differences (compared to placebo) which exceeded 150 mL for all doses, and specifically exceeded 200 mL at total daily doses ≥400 μg.

The 24-h spirometric profiles at day 28 in the subset of patients at overnight sites showed in the placebo-treated patients a diurnal variation, with a FEV1 decrease of approximately 100 mL overnight. Despite the fluctuations due to diurnal effect, all active treatment arms at least tracked the changes and maintained the differences achieved in lung function compared to placebo. There is a suggestion that doses of GSK961081 ≥200 μg twice daily or ≥400 μg once daily had a reduced diurnal variation, resulting in greater differences in mean lung function compared to placebo during the evening period. Patients showed sustained bronchodilation over the 24-h period with all doses of GSK961081, although less so with the 100 μg once daily or the 100 μg twice daily doses.

The 12-h spirometric profiles of all patients showed that there was an increase in improvement of trough FEV1 versus placebo from day 1 to day 28. The trough FEV1 increased up to day 14 and then remained constant for the remainder of the study (online supplementary table S1).

GSK961081 onset was rapid, with ≥60% of patients across all GSK961081 doses reaching 100-mL improvement in FEV1 by the first post-dose assessment (15 min), with the majority of patients reaching peak bronchodilation between 1 h and 2 h. GSK961081 also showed nominal statistical improvements compared to placebo for trough FVC and rescue medication use.

In general, GSK961081 was well tolerated. The most common adverse events were headache, cough, dysgeusia and nasopharyngitis. Treatment with GSK961081 was associated with prolongation of various QTc intervals ranging from 3 to 5 ms more compared to placebo or salmeterol. However, there was no apparent dose–response relationship, and in a previous study [15], where a dose of 1200 μg once daily was used, there was no prolongation of the QT interval seen. In pre-clinical studies in dogs, high doses of GSK961081 showed the development of vocal fold erosions in the larynx. Two patients were excluded at screening due to pre-existing laryngopharyngeal reflux or oesophageal reflux. Throat symptoms were monitored throughout the study. On treatment there were two reported incidents of throat symptoms lasting longer than 7 days, but laryngoscopy showed no evidence of vocal fold erosions.

The main limitation of this phase IIb study was that it used a selected population of moderate and severe COPD patients. Whether the effect sizes seen in this study would be maintained for a longer period of time in a broader COPD population will need to be addressed in future studies.

COPD treatment guidelines recommend the use of a single bronchodilator initially. Single bronchodilators such as salmeterol, in moderate or severe COPD patients provide ∼80 mL improvement in trough FEV1 versus placebo whereas tiotropium and indacaterol show ∼100 mL improvement [18–20]. If patients remain symptomatic, guidelines suggest adding a bronchodilator with a different mechanism [1]. Clinical studies provide the evidence for this [3–10]. When tiotropium was added to indacaterol in a moderate-to-severe COPD population in two separate studies an improvement of 60–90 mL versus tiotropium alone was seen [21]. In a double-blind 26-week study with moderate-to-severe COPD patients taking the fixed dose dual bronchodilator QVA149, there was a 200-mL (p<0.001) improvement versus placebo [20]. Therefore, the expectation was that a bronchodilator with two mechanisms of action would provide a trough improvement of ∼200 mL. The improvement in trough FEV1 of ≥200 mL was achieved by the 800-μg once-daily, 400-μg once-daily, 200-μg twice-daily and 400-μg twice-daily GSK961081 regimens versus placebo. The 100-μg once-daily and 100-μg twice-daily regimens, while an improvement over single bronchodilators, are sub-optimal in terms of the 200 mL trough FEV1 expectation for a bronchodilator with two mechanisms. Although the improvements in lung function at total daily doses ≥400 μg for GSK961081 appear similar to current combinations, direct comparisons need to be carried out in randomised controlled trials.

In conclusion, GSK961081 is bifunctional, having both muscarinic antagonist and β2-agonist activities in the same molecule. This study showed that a total daily dose of 400 μg GSK961081 was optimal given either as 400 μg once daily or 200 μg twice daily. GSK961081 had a rapid onset of action, was a potent bronchodilator in moderate and severe COPD patients and appeared to be safe and well tolerated.

Acknowledgments

The GlaxoSmithKline study team including: Helen Griffiths and Ginny Norris (GlaxoSmithKline, Uxbridge, UK) and Dmitriy Galkin (GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA). The investigators: I. Abdullah (South Africa), K. Arpasova (Slovakia), Z. Aisanov (Russian Federation), T. Bantje (The Netherlands), E. Bateman (South Africa), L. Bjermer (Sweden), V. Blazhko (Ukraine), A. Bruning (South Africa), D. De Munck (The Netherlands), M. Dzurilla (Slovakia), Y. Feshchenko (Ukraine), K. Foerster (Germany), V. Gavrysiuk (Ukraine), M. Goossens (The Netherlands), M. Hajkova (Slovakia), H. Hukelova (Slovakia), L. Iashyna (Ukraine), E. Irusen (South Africa), R. Jogi (Estonia), J. Joubert (South Africa), O. Kornmann (Germany), E.M. Kuulpak (Estonia), I. Leshchenko (Russian Federation), A. Lindberg (Sweden), A. Linnhoff (Germany), M. Löfdahl (Sweden), B. Lundback (Sweden), A. Ludwig-Sengpiel (Germany), T. Mihaescu (Romania), S. Mihaicuta (Romania), Y. Mostovoy (Ukraine), R. Nemes (Romania), L. Ogorodova (Russian Federation), M. Ostrovskyy (Ukraine), T. Pertseva (Ukraine), E. Pribulova (Romania), A. Rascu (Romania), D. Richter (South Africa), P. Samaruutel (Estonia), I. Schenkenberger (Germany), W. Schroeder-Babo (Germany), H. Sinninghe Damste (The Netherlands), E. Sooru E (Estonia), R. Stallaert (The Netherlands), V. Sushko (Ukraine), V. Trofimov (Russian Federation), P. Wielders (The Netherlands), J. Wuerziger (Germany), V. Zorin (Ukraine). The patients themselves, without whom this research could not be conducted. Editorial support (in the form of assembling, copy-editing and graphic services) was provided by Ian Grieve at Gardiner-Caldwell Communications (Macclesfield, UK) and was funded by GlaxoSmithKline.

Footnotes

For editorial comments see page 885.

This article has supplementary material available from www.erj.ersjournals.com

Clinical trial: This study is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov with identifier number NCT01319019 and www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu with identifier number MAB115032.

Support statement: This study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline. Editorial support was funded by GlaxoSmithKline.

Conflict of interest: Disclosures can be found alongside the online version of this manuscript at www.erj.ersjournals.com

References

- 1.Global InitiativeforChronicObstructiveLungDisease(GOLD) Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, 2011. www.goldcopd.org/guidelines-global-strategy-for-diagnosis-management.html Date last accessed: October 10, 2012. Date last updated: February 2013

- 2.Celli BR, MacNee WATS/ERS Task Force Standards of the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J 2004; 23: 932–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cazzola M, Molimard M. The scientific rationale for combining long-acting β2-agonists and muscarinic antagonists in COPD. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2010; 23: 257–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cazzola M, Centanni S, Santus P, et al. The functional impact of adding salmeterol and tiotropium in patients with stable COPD. Respir Med 2004; 98: 1214–1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cazzola M, Noschese P, Salzillo A, et al. Bronchodilator response to formoterol after regular tiotropium or to tiotropium after regular formoterol in COPD patients. Respir Med 2005; 99: 524–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Noord JA, Aumann JL, Janssens E, et al. Comparison of tiotropium once daily, formoterol twice daily and both combined once daily in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J 2005; 26: 214–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Noord JA, Aumann JL, Janssens E, et al. Effects of tiotropium with and without formoterol on airflow obstruction and resting hyperinflation in patients with COPD. Chest 2006; 129: 509–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tashkin DP, Littner M, Andrews CP, et al. Concomitant treatment with nebulized formoterol and tiotropium in subjects with COPD: a placebo-controlled trial. Respir Med 2008; 102: 479–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van derMolen T, Cazzola M. Beyond lung function in COPD management: effectiveness of LABA/LAMA combination therapy on patient-centred outcomes. Prim Care Respir J 2012; 21: 101–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Fergusson D, et al. Tiotropium in combination with placebo, salmeterol, or fluticasone-salmeterol for treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2007; 146: 545–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobsen JR, Aiyar J, Hegde S, et al. Dual-pharmacology bronchodilators for the treatment of COPD. : M. Hansel TT, Barnes PJ, et al., New Drugs and Targets for Asthma and COPD. Progress in Respiratory Research. Vol. 39. Basel, Karger, 2010; pp. 39–45 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aiyar J, Steinfeld T, Pulido-Rios MT, et al. In vitro characterization of TD-5959: a novel bi-functional molecule with muscarinic antagonist and β2-adrenergic agonist activity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009; 179: A4552 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pulido-Rios MT, McNamara A, Kwan K, et al. TD-5959: a novel bi-functional muscarinic antagonist–β2-adrenergic agonist with potent and sustained in vivo bronchodilator activity in guinea pigs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009; 179: A6195 [Google Scholar]

- 14.GSK Clinical Trials Register A study to investigate the relative pharmacological activity of an inhaled β2-agonist/anticholinergic dual pharmacophore in healthy volunteers. www.gsk-clinicalstudyregister.com/quick-search-list.jsp?item=MAB110553&type=GSK+Study+ID&studyId=MAB110553 Date last updated: April 21, 2009

- 15.Norris V, Zhu C, Ambery C. The pharmacodynamics of GSK961081 in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J 2011; 38: Suppl. 55, 138s [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nh3data.htm Date last accessed: October 10, 2012.

- 17.Donohue JF. Minimal clinically important differences in COPD lung function. COPD 2005; 2: 111–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donohue JF, van Noord JA, Bateman ED, et al. A 6-month, placebo-controlled study comparing lung function and health status changes in COPD patients treated with tiotropium or salmeterol. Chest 2002; 122: 47–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buhl R, Dunn LJ, Disdier C, et al. Blinded 12-week comparison of once-daily indacaterol and tiotropium in COPD. Eur Respir J 2011; 38: 797–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bateman E, Ferguson GT, Barnes N, et al. Benefits of dual bronchodilation with QVA149 once daily versus placebo, indacaterol, NVA237 and tiotropium in patients with COPD: the SHINE study. Eur Respir J 2012; 40: Suppl. 56, 509s [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahler DA, D'Urzo A, Bateman E, et al. Concurrent use of indacaterol plus tiotropium in patients with COPD provides superior bronchodilation compared with tiotropium alone: a randomised, double-blind comparison. Thorax 2012; 67: 781–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]