Abstract

Previously authors have recently described an association between nilotinib therapy for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and severe peripheral artery disease, coronary artery disease and sudden death. We present a case report of a male patient with CML who received nilotinib therapy. He developed bilateral renal artery stenosis and renovascular hypertension. He had no history of hypertension, cardiovascular disease, or diabetes, and he was a nonsmoker. Together, these observations indicated that obtaining further understanding of the effects is necessary and that extreme caution is warranted when considering second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors for first-line therapy in CML.

Keywords: Renal artery stenosis, Leukemia, Tyrosine kinase inhibitor, Renovascular hypertension

We present a case report of a patient with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) who developed bilateral renal artery stenosis during tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy. Only a few reports associate TKIs with acute renal failure,1,2 and renovascular hypertension has not been previously described. Reports on peripheral artery occlusive disease occurring during nilotinib therapy have recently been published.3,4

A 58-yr-old, nonsmoking, nondiabetic male patient with no history of cardiovascular disease or hypertension was diagnosed with CML in 2001. He was secondarily refractory to imatinib as a result of ABL mutations and developed a myeloid blast crisis in May 2006. Induction therapy with dasatinib was successful, leading to a major molecular remission, but in 2008, the patient had recurrent pleural effusions. The therapy was switched to 400 mg nilotinib twice daily in April 2008.

The patient was hospitalized in August 2009 after a 6-month period of tinnitus, dizziness, headache, and vision disturbance. At the time of admission, his blood pressure was 260/140 mmHg. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed no signs of left ventricular hypertrophy, and an x-ray of the chest was normal. Ophthalmoscopy did not show hypertensive retinopathy. An echocardiography did not indicate any signs of left ventricular hypertrophy. A urinary dipstick was negative for protein.

Examination of the blood tests showed slightly decreased glomerular function with creatinine increasing from 104 μmol/l to 160 μmol/l (reference range 60–105 μmol/l) in the first 5 days following admission. The patient started treatment with alpha and beta inhibitors, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor and calcium antagonists.

During hospitalization, the patient experienced dysarthria, hemianopsia and right-sided facialis nerve paresis. His blood pressure was 185/100 mmHg. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the cerebrum showed an old infarction in the caudate nucleus and the internal capsula but no recent bleedings or infarctions. The patient started treatment with aspirin, dipyridamole and simvastatin.

Captopril renography showed that the relative uptakes in the right and left kidneys were 35% and 65%, respectively, and showed delayed excretion from the right kidney.

The antihypertensive treatment was optimized with diuretics. An ultrasound of the kidney was normal except for thickening of the bladder wall due to a known hypertrophy of the prostate gland.

A renography was performed after 2 weeks without ACE inhibitor treatment. The renography demonstrated that the right kidney had a low relative uptake, accounting for only 11% of the renal function. CT angiography showed bilateral renal artery stenosis, which was more severe on the right side. No atherosclerosis was found in the renal artery or in the aorta.

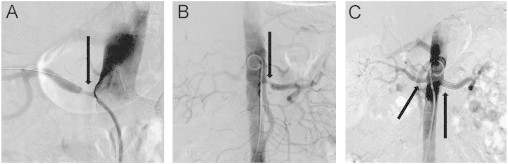

The patient was treated with endovascular stents in both renal arteries. There were no complications (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

CT angiography with contrast. (a) Renal artery stenosis on the right side. (b) Renal artery stenosis on the left side. (c) After treatment with bilateral percutan transluminal renal angioplasty.

The patient has been followed as an out-patient, and the most recent blood pressure measurement was 140/50 mmHg (May 2012), although he reported a lower measurement at home. The creatinine level was 119 μmol/l. Nilotinib has been continued at the same dosage, and the patient remains stable in complete molecular remission.

Chronic myeloid leukemia is a myeloproliferative disorder characterized by the occurrence of the fusion gene BCR-ABL located on the derivative chromosome 22 (Philadelphia chromosome), which results from a translocation between chromosome 9 and 22. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) targeted against the BCR-ABL kinase have revolutionized CML treatment by reducing the number of patients progressing to an accelerated phase or a blast crisis.5 TKIs are generally well tolerated.

The most frequent nonhematological side effects of TKIs are fluid retention, rash, pruritus, nausea, fatigue and headache. Biochemically, the elevation of pancreatic enzymes, fasting glucose, and cholesterol levels has been reported in some patients. Congestive heart failure and left ventricular dysfunction have been observed.6

Among unselected hypertension patients, the frequency of renal artery stenosis is 0.5%, but the frequency is as high as 10%–20% in patients with severe hypertension.7

Renal artery stenosis is common in elderly patients with general atherosclerosis. Renal artery stenosis due to fibromuscular dysplasia in the renal artery is most commonly observed in younger women. Renovascular hypertension can be treated medically or by surgery and endovascular procedures.

In our case, the patient showed no signs of long-lasting hypertension, and there were no signs of significant atherosclerosis. We find that the renal artery stenosis was most likely caused by nilotinib.

There are only a few reports on renal dysfunction in patients treated with TKIs. Less than 1% of patients with normal baseline renal function developed renal failure.1 The renal excretion of TKIs is low. Two different possible mechanisms responsible for TKI-associated renal failure have been suggested: tumor lysis syndrome and toxic tubular damage caused by the drug. Mouse and rat models of accelerated diabetic nephropathy, renal fibrogenesis, autoimmune glomerulonephritis or lupus nephritis have associated TKI therapy with renal injury. These studies suggested that interstitial fibrosis is a common mechanism for renal injury and that signaling pathways mediated by tyrosine kinases play a role in the pathogenesis of this injury.2 To our knowledge, there are no reports on nilotinib leading to renal artery stenosis, but recent reports of peripheral and coronary artery occlusive disease3,4 have drawn attention to this potentially serious side effect. Long-term safety data for nilotinib are not available yet. It has been described that it increases the fasting glucose level and thereby provokes diabetes mellitus.8 Recent data suggest that nilotinib bind to key kinase targets such as discoidin domain receptor 1 (DDR1). This receptor has been implicated in plaque formation in atherosclerosis.9 Nilotinib is a blocker of the receptor kinase KIT which is found to be a major regulator of mast cells which regulates molecules as histamine and heparine.10 This could also contribute to depressed vascular repair system and thereby predispose to thromboembolic and arterostenotic events. Maybe multiple mechanisms are responsible for these vascular events.

The frequency of nilotinib-induced renal artery stenosis is uncertain. In the present case, it is tempting to hypothesize that the occlusive renal artery disease has the same pathogenesis as the peripheral artery occlusive disease. The patient was in a deep molecular response at the onset of the hypertension, and tumor lysis syndrome was not a consideration.

While disorders related to atherosclerotic and fibromuscular diseases are the most common causes of renal artery stenosis, it should be recognized that any structural disorder reducing renal perfusion to kidney tissue is capable of producing endovascular hypertension.

TKIs are a highly targeted class of therapeutics for CML. It is becoming increasingly clear that off-target side effects may be clinically relevant. Further understanding of the effects is necessary, and extreme caution is warranted when considering second-generation TKIs for first-line therapy in CML.

Contribution

All authors contributed to the writing and preparation of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Sten Langfeldt, Department of Radiology, Aarhus University Hospital, Skejby, for his radiological expertise.

Tilde Kristensen and Else Randers have no disclosures with regard to financial support. Jesper Stentoft has been the national primary investigator for studies of imatinib, dasatinib, and nilotinib, sponsored and financed by Novartis and Bristol-Myers-Squibb, has served as a member of advisory boards for both companies, and has received honoraria for participation in postgraduate educational activities related to chronic myeloid leukemia.

References

- 1.Gafter-Gvil A., Ram R., Gafter U., Shpilberg O., Raanani P. Renal failure associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors—case report and review of the literature. Leukemia Research. 2010;34:123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holstein S., Stokes J., Hohl R. Renal failure and recovery associated with second-generation Bcr-Abl kinase inhibitors in imatinib-resistant chronic myelogenous leukemia. Leukemia Research. 2009;33:344–347. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aichberger K.J., Herndlhofer S., Schernthaner G.-H., Schillinger M., Mitterbauer-Hohendanner G., Sillaber C. Progressive peripheral occlusive disease and other vascular events during nilotinib therapy in CML. American Journal of Hematology. 2011;86:533–539. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tefferi A., Letendre L. Nilotinib treatment-associated peripheral artery disease and sudden death: yet another reason to stick to imatinib as front-line therapy for chronic myelogenous leukemia. American Journal of Hematology. 2011;86(7):610–611. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Druker B., Guilhot F., O'Brien S., Garthmann I., Kantarjian H., Gattermann N. Five-year follow-up of patients receiving Imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355:2408–2417. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartmann J., Haap M., Kopp H., Lipp H. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors—a review on pharmacology, metabolism and side effects. Current Drug Metabolism. 2009;10:470–481. doi: 10.2174/138920009788897975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Textor S. Current approaches to renovascular hypertension. Medical Clinics of North America. 2009;93:717–732. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breccia M., Muscaritoli M., Gentilini F., Latagliata R., Carmosino I., Rossi Fanelli F. Impaired fasting glucose level as metabolic side effect of nilotinib in non-diabetic chronic myeloid leukemia patients resistant to imatinib. Leukemia Research. 2007;31:1765–1772. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2007.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franco C., Britto K., Wong E., Hou G., Zhu S., Chen M. Discoidin domain receptor 1 on bone marrow-derived cells promotes macrophage accumulation during atherogenesis. Circulation Research. 2009;105:1141–1148. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.207357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valent P., Baghestanian M., Bankl H.C., Sillaber C., Sperr W.R., Wojta J. New aspects in thrombosis research: possible role of mast cells as profibrinolytic and antithrombotic cells. Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2002;87:786–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]