Abstract

Background

Imaging myocardial activation from noninvasive body surface potentials promises to aid in both cardiovascular research and clinical medicine.

Objective

This study investigates the ability of a noninvasive 3-dimensional cardiac electrical imaging (3DCEI) technique for characterizing the activation patterns of dynamically changing ventricular arrhythmias during drug-induced QT prolongation in rabbit.

Methods

Simultaneous body surface potential mapping and 3-dimensional intra-cardiac mapping were performed in a closed-chest condition in eight rabbits. Data analysis was performed on premature ventricular complexes, couplets, and torsades de pointes (TdP) induced during i.v. administration of clofilium and phenylephrine with combinations of various infusion rates.

Results

The drug infusion led to significant increase of QT interval (175±7ms to 274±31ms) and rate-corrected QT interval (183±5ms to 262±21ms) during the first dose cycle. All the ectopic beats initiated by a focal activation pattern. The initial beat of TdPs arose at focal site, whereas the subsequent beats were due to focal activity from different sites or two competing focal sites. The imaged results captured the dynamic shift of activation patterns and were in good correlation with the simultaneous measurements with a correlation coefficient of 0.65±0.02 averaged over 111 ectopic beats. Sites of initial activation were localized to be ~5mm.

Conclusion

The 3DCEI technique could localize the origin of activation and image activation sequence of TdP during QT prolongation induced by clofilium and phenylephrine in rabbit. It offers the potential to non-invasively investigate the proarrhythmic effects of drug infusion and assess the mechanisms of arrhythmias on a beat-to-beat basis.

Keywords: cardiac imaging, electrocardiography, cardiac mapping, torsades de pointes, QT prolongation, rabbit model

Introduction

Torsades de pointes (TdP)1 is a life-threatening arrhythmia that might degenerate into ventricular fibrillation and cause sudden cardiac death. TdP can occur during QT prolongation, as a consequence of genetic alteration or drug administration. Various investigations have been made to examine the potential of drugs to prolong QT interval and cause TdP, which usually exhibits a characteristic twisting of QRS complexes around the isoelectric axis.1 TdP has a continuously changing QRS morphology and thus requires single-beat mapping techniques to characterize the dynamic activation patterns within the heart. Three-dimensional (3D) intra-cardiac mapping technique emerges as an important tool to investigate the electrophysiological mechanism underlying the ventricular arrhythmias associated with QT prolongation in in vivo animal models.2–5

Noninvasive cardiac electrical imaging techniques represent a novel means which offer the potential to help define the underlying arrhythmia mechanisms and facilitate therapeutic treatments in clinical medicine.6–8 By estimating the equivalent cardiac sources from body surface potential maps (BSPMs), such techniques could provide noninvasive information with regard to the global cardiac activation pattern in a single beat and thus may be used to study the proarrhythmic effects of drug infusion. In this study, we apply a novel 3D cardiac electrical imaging (3DCEI) technique8–10 to study the activation patterns of TdP during drug-induced QT prolongation in rabbit. We performed simultaneous body surface potential mapping and 3D intra-cardiac mapping11–13 in a closed-chest condition8,14 in rabbits. The class III antiarrhythmic drug clofilium15 and phenylephrine were infused in the in vivo rabbit model to prolong QT interval and induce ventricular arrhythmias16 including premature ventricular complex (PVC), couplet, and TdP. The imaged activation sequence was also compared with the simultaneously measured activation sequence from 3D intra-cardiac mapping.

Methods

Experimental Procedures

Eight healthy New Zealand white rabbits of either sex (3.6 to 4.3 kg) were studied under a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Minnesota and the University of Alabama at Birmingham. The animal preparation and surgical procedure were as described in reference.8 Up to 64 repositionable BSPM electrodes were uniformly placed to cover the anterior-lateral chest up to the mid-axillary line, and up to 27 transmural plunge-needle electrodes were inserted in the left ventricle (LV) and right ventricle (RV) of the rabbits. Each LV plunge-needle electrode contains 8 bipolar electrode-pairs with an inter-electrode distance of 500 μm, while each RV electrode contains 2 bipolar electrode-pairs with an inter-electrode distance of 500 μm. The chest and skin were then carefully closed with silk suture. Bipolar electrograms were continuously recorded from all electrode-pairs together with body surface potentials from surface electrodes. At the completion of the mapping study, post-operative ultra fast computed tomography (UFCT) scans were performed on the living rabbit to build realistic geometry model and localize the plunge-needle electrodes within the myocardium.8 We performed pre-operative UFCT scans on all animals. However, the pre-operative UFCT images were only used when the post-operative UFCT images were unavailable. For all rabbits, the plunge-needle electrodes were carefully localized by replacing each with a labeled pin. The heart was then fixed in formalin and underwent an ex vivo UFCT scan to further facilitate precise 3D localization of the transmural electrodes.

Drug Infusion Protocol

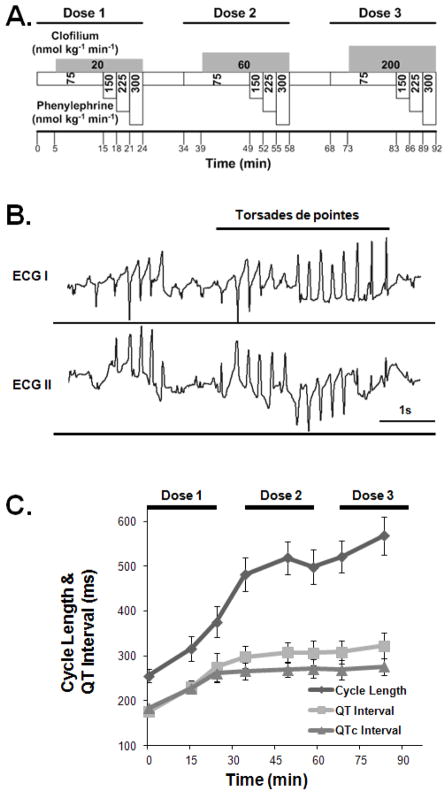

Ventricular arrhythmias including PVCs, couplets, and TdPs were induced by i.v. administration of clofilium and phenylephrine in combinations of various infusion rates in the in vivo normal rabbit heart using an established protocol.16 Figure 1.A shows the protocol for drug infusion. For the first dose cycle, the phenylephrine infusion rate was begun at 75 nmol kg−1 min−1, and gradually increased to 150, 225 and 300 nmol kg−1 min−1 for every 3 min, while clofilium was infused at 20 nmol kg−1 min−1 5 min after the infusion of phenylephrine. This protocol was repeated at higher doses of clofilium at 60 and 200 nmol kg−1 min−1 with the same infusion rate for phenylephrine for the second and third dose cycles. There were 10 min intervals between different dose cycles.16

Figure 1.

(A) The drug infusion protocol. (B) Example of torsades de pointes. (C) The change of cycle length, QT interval, and rate-corrected QT (QTc) interval during the drug infusion.

Principles of 3DCEI

The cardiac electrical activity throughout the ventricular myocardium was represented by a distributed equivalent current density model. Derived from bidomain theory,17,18 potentials measurable over the body surface were linearly related to the equivalent current density distribution. A spatiotemporal regularization technique and lead-field normalized weighted minimum norm estimation10,19 were used to reconstruct the time course of local equivalent current density at each myocardial site. The activation time at each myocardial site was determined as the instant when the time course of the estimated local equivalent current density reached its maximum magnitude.10

Data Analysis

Post-experiment data analysis was performed for the recorded ECG data. The QT interval was manually annotated from the beginning of Q wave to the end of the T wave using ECG lead I and lead II, as well as body surface ECGs. The rate-corrected QT (QTc) interval was calculated according to Carlsson’s formula: QTc = QT − 0.175(RR - 300).20

The measured activation sequence was constructed in the method previously described in8,9 when the post-operative UFCT scans were available. When post-operative UFCT scans were unavailable (rabbits 3, 4, and 8), the pre-operative UFCT images were used to build the in vivo heart-torso model. An alternative ex vivo heart model was built based on the ex vivo UFCT images of the isolated heart. The plunged-needle electrodes were localized and each needle was represented by a line in this ex vivo heart model. A registration process was used by shifting and rotating the ex vivo heart model to minimize the distance error of the anatomical landmarks (e.g., apex, outflow tract, and atria appendages) between the in vivo heart model and ex vivo heart model. After registration, each line representing the needle was extended and the intersection point between the line and the surface of the in vivo heart model was identified. Based on this intersection point, the direction of the line, and the structure information of each needle, the locations of the plunge-needle electrodes in the in vivo heart model were estimated. The corresponding activation time of each recording electrode was assigned on the basis of peak criteria,13,14,15,21 and then an interpolation algorithm as described in8 was applied to obtain the complete 3D measured activation sequence throughout the ventricular myocardium.

Numerical data are presented as mean ± SEM. The correlation coefficient (CC) was computed to quantify the overall agreement between the measured and imaged activation sequences. The localization error (LE), which is defined as the distance between site of earliest activation from 3D intra-cardiac measurements and the center of mass of the myocardial region with the earliest imaged activation time was computed to evaluate the performance of 3DCEI in localizing the origin of activation. Statistical significance of differences was evaluated by Student’s t-test, and a P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Experimentation and Modeling

After insertion of plunge electrodes, closure of the chest did not alter heart rate or mean arterial blood pressure (232 ± 6 vs 238 ±6 bpm and 62±4 vs 62±3 mm Hg, respectively, P=NS vs pre-closure) or total activation times (TATs) of sinus beats (31±1ms vs 29±1ms, P=NS vs pre-closure), which were consistent with previously published data in control rabbits.8 The infusion of clofilium and phenylephrine led to significant increase of the RR interval (255±14ms to 376±34ms, P<0.05), the QT interval (175±7ms to 274±31ms, P<0.05), and the QTc interval (183±5ms to 262±21ms, P<0.05) during the first dose cycle, as shown in Figure 1.C. The change of QT interval and QTc interval was greater in the first dose cycle, as compared to the other two cycles. Table 1 summarizes the ventricular arrhythmias induced during the infusion of clofilium and phenylephrine. Ectopic activities in terms of multiform PVCs were observed in all animals. TdPs were induced in four rabbits (See Figure 1.B for an example of TdP on ECG). Rabbit 3 degenerated into ventricular fibrillation. Rabbits 4 and 8 degenerated into ventricular asystole during the last dose cycle.

Table 1.

Ventricular arrhythmias induced during the infusion of clofilium and phenylephrine.

| Rabbit No. | Sex | PVC | Couplet | TdP | Sites of Initiation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RVOT | LV | |||||

|

| ||||||

| 1 | F | + | + | + | Basal anterior. | Basal anterior. |

| 2 | F | + | + | + | Basal inferior, basal lateral. | Basal anterior, apical inferior. |

| 3 | M | + | + | + | Basal lateral, basal anterior. | Basal anterior, middle inferior. |

| 4 | F | + | + | − | Basal anterior. | Middle antero-lateral, apical inferior. |

| 5 | F | + | + | + | Middle anterior, middle septum. | Apical lateral. |

| 6 | F | + | + | − | Middle anterior | Middle antero-septal, apical anterior. |

| 7 | F | + | + | − | Basal lateral | Basal antero-septal, basal anterior, basal infero-lateral. |

| 8 | F | + | − | − | Basal lateral. | Apex. |

Note: PVC, premature ventricular complex; TdP, torsades de pointes; RVOT, right ventricle outflow tract; LV, left ventricle.

The realistic geometry rabbit heart-torso model was constructed for each animal from the UFCT images. The rabbit ventricular myocardium was tessellated into 6987±330 evenly-spaced grid points. The spatial resolution of the ventricle models was 1 mm. There were 151±7 intramural bipolar electrodes during 3D intra-cardiac mapping and 59±1 BSPM electrodes on the body surface.

PVCs and Couplets

Data analysis using 3DCEI and 3D intra-cardiac mapping performed on a total of 31 isolated PVCs and 7 couplets from all rabbits suggests that these ectopic beats initiated in the subendocardium by focal activation. For each rabbit, the PVCs were observed to continuously initiate at several myocardial sites. The initiation sites covered both LV and RV outflow tract (RVOT). PVCs initiated with a cycle length (CL) of 407±18ms and conducted with a TAT of 53±2ms, while the CL and TAT for couplets were 387±32ms and 56±2ms respectively, as shown by 3D intra-cardiac mapping.

Figure 2.A and Figure 2.B show the comparison between the measured and imaged activation sequences for two PVC beats in rabbit 1. The first PVC initiated at basal anterior RVOT, and the wavefront then propagated over the septum and terminated at middle lateral LV. The second PVC initiated at the basal anterior LV and terminated at posterior RV. The imaged results resembled the measured counterparts with respect to the overall activation patterns. Furthermore, the initiation sites were reconstructed at basal anterior RVOT and basal anterior LV respectively. Multiple PVCs and beats from TdPs in rabbit 1 were observed to be continuously firing at these two sites. Figure 3 shows a couplet in rabbit 7. The first beat in Figure 3.A initiated at basal lateral wall of RVOT and terminated at middle left wall. The second beat of this couplet initiated at the basal anterior septum of LV and terminated at RV lateral wall. The imaged results captured the overall activation patterns for this couplet and the initial sites were identified respectively.

Figure 2.

Comparison between the measured and imaged activation sequences for two premature ventricular contractions (A) and (B) in rabbit 1. The activation sequence is color coded from red to blue, corresponding to earliest and latest activations. ECG lead I is shown with red boxes indicating the beats analyzed. The activation sequence is displayed on epicardial and endocardial surfaces, respectively, in an anterior view. The measured initial site and the estimated initial site of activation are marked by a black asterisk and a purple arrow.

Figure 3.

Comparison between measured and imaged activation sequences for a couplet (A) and (B) in rabbit 7. The epicardial and endocardial surfaces are displayed in a right anterior view for the beat in (A) and in a left top view for the beat in (B), respectively.

Figure 4 shows PVC beat in rabbit 8 that degenerated into the ventricular asystole. The ECG suggested there was no ventricular electrical activity after two ventricular ectopic beats. These two ventricular ectopic beats had the same activation pattern, with a focal initiation at basal lateral of RVOT. The imaged activation sequence captured the overall activation pattern and identified the initiation site at basal lateral wall of RVOT for the beat indicated in the red box of ECG.

Figure 4.

Comparison between measured and imaged activation sequences for a premature ventricular complex preceding ventricular asystole in rabbit 8. The epicardial and endocardial surfaces are displayed respectively in an anterior view.

TdPs

TdPs were induced in four rabbits. The QT interval and QTc interval of sinus beats right before the onset of first TdPs were increased as compared with those of sinus beats before drug infusion (285±29ms vs 180±14ms, P<0.05 for QT interval and 258±22ms vs 188±9ms, P<0.05 for QTc interval). Data analysis was performed on a total of 73 beats from 10 episodes of TdPs (three to twenty-two beats for each episode). The averaged CL was 263±10ms and TAT was 52±1ms. All these ectopic beats had focal initiation.

Figure 5.A and Figure 5.B show the simultaneous recordings of ECG tracings (CH1-CH9) in 3DCEI and bipolar electrograms of a ten-beat TdP in rabbit 2. The ECG morphology exhibited twisted QRS complexes around the isoelectric axis in lead I. More negative QRS-complexes turned into more positive complexes with an intervening transition zone. The averaged CL was 195±8ms and TAT was 52±5ms for this TdP. Figure 5.B suggests the focal activation pattern for the first two beats of this TdP, based on the selected bipolar electrograms throughout the ventricles. Figure 5.C, Figure 5.D, and Figure 5.E show the activation sequences for beat 2, beat 7, and beat 9 respectively. At the beginning of this TdP, activation initiated from a subendocardial site of the basal LV (site “L”). From there, it spread to the basal lateral wall of RVOT. This activation pattern did not change significantly for the first 6 ectopic beats and the site of latest activation during an ectopic beat was far from the site of earliest activation of the following beat. Beat 9 and beat 10 demonstrated another typical activation pattern, with initiation located at the RV base (site “R”), as shown in Figure 5.E. The mapping results further suggested that in the middle of this TdP, there was simultaneous early activation at two sites, with one site located at basal lateral RVOT and another site located at basal LV, indicating the fusion beats with two completing foci (sites “L+R”), as shown in Figure 5.D for beat 7 and beat 8. The imaged activation sequences clearly captured such dynamic transition of activation patterns and identified two initiation sites for this TdP. Besides, the two initiation sites of this TdP were well localized from the imaged activation maps.

Figure 5.

(A) Selected channels of ECG tracings (CH1-CH9) in body surface potential mapping for 3DCEI and ECG lead I for a ten-beat torsades de pointes (TdP) in rabbit 2. “L” indicates the initiation site located in the left ventricle and “R” indicates the initiation site located in the right ventricle. (B) Selected bipolar electrograms for the first two beats of this TdP. In the left column, red dots and letters from a to j represent the locations for the selected plunge-needle electrodes in the heart. In the middle and right columns, the activation time for each bipolar electrogram is displayed in red for the first two beats of this TdP. Panels (C), (D), and (E) show the comparison between measured and imaged activation sequences for beat 2, beat7, and beat 9 of this TdP, respectively. The epicardial and endocardial surfaces are displayed in an anterior view.

Figure 6 shows another example of a 6-beat TdP in rabbit 3. In Figure 6.A, the first ectopic beat had an initiation site at anterior RVOT, and then the initiation site shifted to anterior middle wall of LV for the second ectopic beat (Figure 6.B). The last four ectopic beats had continuously been firing at the same site at post-lateral wall of middle RV (Figure 6.C). The averaged CL was 220±8ms and TAT was 48±2ms for this TdP. The imaged activation sequence clearly captured such shift of initial activation sites and the overall activation patterns were in good agreement with the measurements.

Figure 6.

Comparison between measured and imaged activation sequences for a six-beat TdP in rabbit 3. Panels (A), (B), and (C) show the activation sequence for the first three beats, respectively. The epicardial and endocardial surfaces are displayed in an anterior view (A), a left anterior view (B), and a right posterior view (C) respectively.

The quantitative comparison was also performed between imaged and measured activation sequences. Averaging 111 ectopic beats from PVCs, couplets, and TdPs with single focal initiation site, the CC was 0.65±0.02, suggesting good agreement between the imaged results and the simultaneous measurements. Furthermore, the origin of arrhythmias was estimated to be 5.9±0.3mm from the measured site, implying the reasonably good localization accuracy.

Discussion

The present study reports the use of a novel 3DCEI technique to non-invasively investigate the global activation pattern of cardiac arrhythmias during drug-induced QT-prolongation in the in vivo rabbit heart. We showed that the infusion of clofilium and phenylephrine led to QT prolongation and induced different forms of ventricular arrhythmias during simultaneous body surface potential mapping and 3D intra-cardiac mapping. The data analysis suggested that the ectopic beats including PVCs, couplets, and TdPs were all initiated by a focal mechanism and the TdPs were then maintained with the dynamical shift of initiation sites or two completing foci. The imaged activation sequences were in good correlation with the simultaneous intra-cardiac measurements with an averaged CC of 0.65±0.02 and LE of ~5mm over 111 ectopic beats with single initiation site. These findings imply that 3DCEI is feasible in reconstructing global activation pattern and imaging dynamically changing arrhythmias on a beat-to-beat basis.

Much effort has been devoted to the development of noninvasive cardiac electrical imaging techniques to estimate the equivalent cardiac sources from BSPMs.6–10,14,22–33 The current imaging method has a notable feature of imaging cardiac activation sequence throughout the ventricular myocardium, which represents an important alternative over other heart surface-based imaging techniques. The present study has used a novel in vivo experimental design in which BSPMs were obtained simultaneously with intramural electrical recordings from plunge-needle electrodes in a closed-chest protocol, and thus enabled quantitative assessments of the 3DCEI approach in animal models with clinically relevant cardiac diseases. This work extended our previous study in the control rabbits8 into investigating the 3DCEI technique for imaging activation sequence in the setting of drug-induced prolongation of action potential and QT interval in rabbits. This also represented an important effort to define the potential role of this method in facilitating clinical diagnosis and management of cardiac arrhythmias. The imaging performance was consistent with our previous findings in the control rabbits8 in terms of CC and LE. The close match between the imaged activation sequence and the direct measurement suggests that significant information regarding ventricular excitation (e.g., global activation pattern and regions with earliest and latest activation) has been preserved in the imaged activation maps in this animal model of human disease.

In this study, post-operative UFCT scans were unavailable in three rabbits. Therefore the pre-operative UFCT images were used to build the in vivo heart model and the registration process was used to estimate the locations of the plunge-needle electrodes in this pre-operative in vivo heart model. In our previous study, we have shown that similar activation pattern was obtained between the registration-based procedure and the 3D activation mapping procedure using hand drawing on templates of axial slices of the rabbit heart.14 In this study, we further evaluated the accuracy of the registration process in two rabbits in which the post-operative in vivo CT images were available to directly localize the plunge-needle electrodes in the in vivo heart model. The averaged CC between the activation sequence from directly localized plunged-needle electrodes and the activation sequence from registration-based plunged-needle electrodes was 0.91±0.04 (ranged from 0.86 to 0.97) from ectopic beats with six different initiation sites. We believed that the registration error was modest and registration process would not affect significantly the characterization of activation pattern in arrhythmias, which is the key focus of this study.

The results suggest the potential clinical role of 3DCEI in diagnosing arrhythmia mechanisms and complementing cardiac mapping techniques. Different ventricular arrhythmias including PVCs, couplets, and TdPs were induced during the infusion of clofilium and phenylephrine in the in vivo rabbit heart. The mechanism of TdP perpetuation is still not clear. Two possible mechanisms have been suggested: focal activity due to triggered activity and reentry. Both arrhythmogenic mechanisms have been documented during cardiac mapping studies.2–5,34,35 In the present study, both the 3D intra-cardiac mapping results and the noninvasive imaging results suggested a focal mechanism for the initiation of TdPs that were recorded. The results also found two competing foci, which provided the underlying electrophysiological mechanism for the twisted QRS morphology in ECG in the episodes of TdP. It is noted that the focal mechanism is found particularly in this animal model and the current study cannot provide a clear cut answer to explain the discrepancies between focal and reentry mechanisms for the termination of TdP especially for human or other animal models. Nevertheless, the findings imply the potential role of 3DCEI for characterizing the activation patterns of dynamically-changing ventricular arrhythmias and studying the proarrhythmic effects during drug infusion.

In this study, we defined nonreentrant activation as has been done in a number of previous studies.11,12,13 We have found that mapping from ~200 sites in the rabbit heart (which is equivalent to mapping from over 2600 sites in the canine heart) provides adequate resolution to assess arrhythmia mechanism. We realize that we cannot completely rule out microreentry, but for a small reentrant circuit to occur between electrodes would require a conduction velocity that is at least an order of magnitude slower than the slowest conduction velocity we observed, making reentry extremely unlikely. It is also likely that multi-cellular early afterdepolarizations (EADs) might lead to the fluctuations in body surface potentials. However, in order to provide a more definitive answer to EADs, the experimental protocol needs to be refined to record EADs by some other means (monophasic action potentials catheters or other action potential recordings), in addition to body surface potentials for 3DCEI and intra-cardiac mapping. This is beyond the scope of the current study and needs further investigation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study suggests the capability of 3DCEI to dynamically characterize the 3D ventricular activation patterns and localize the origin of activation during ventricular arrhythmias with drug-induced QT prolongation, as evaluated by 3D intra-cardiac mapping in rabbit. The findings imply the potential application of 3DCEI to aid in studying the proarrhythmic effects of drug infusion and understanding the arrhythmia mechanisms associated with QT prolongation in the clinical setting.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health [HL080093 to B.H., HL073966 to S.M.P.], and the National Science Foundation [CBET-0756331 to B.H.], and by the Institute for Engineering in Medicine of the University of Minnesota. C.H. was supported in part by a Predoctoral Fellowship from the American Heart Association, Midwest Affiliate.

List of Abbreviations

- 3D

3-dimensional

- 3DCEI

3-dimensional cardiac electrical imaging

- ECG

Electrocardiography

- LV

Left ventricle

- PVC

Premature ventricular complex

- RV

Right ventricle

- RVOT

Right ventricle outflow tract

- TdP

Torsades de pointes

- UFCT

Ultra fast computed tomography

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Bin He is an inventor of a US Patent for the imaging technique used in this study.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dessertenne F. La tachycardie ventriculaire a deux foyers opposes variables (in French) Arch Mal Coeur. 1966;59:263–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Sherif N, Caref EB, Yin H, Restivo M. The electrophysiological mechanism of ventricular arrhythmias in the long QT syndrome. Tridimensional mapping of activation and recovery patterns. Circ Res. 1996;79:474–492. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.3.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murakawa Y, Sezaki K, Yamashita T, Kanese Y, Omata M. Three-dimensional activation sequence of cesium-induced ventricular arrhythmias. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H1377–1385. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.3.H1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schreiner KD, Kelemen K, Zehelein J, et al. Biventricular hypertrophy dogs with chronic AV block: effects of cyclosporin A on morphology and electrophysiology. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H2891–H2898. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01051.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boulaksil M, Jungschleger JG, Antoons G, et al. Drug-induced torsade de pointes arrhythmias in the chronic AV block dog are perpetuated by focal activity. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:566–576. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.958991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y, Cuculich PS, Zhang J, et al. Noninvasive electroanatomic mapping of human ventricular arrhythmias with electrocardiographic imaging. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:98ra84. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berger T, Pfeifer B, Hanser FF, et al. Single-beat noninvasive imaging of ventricular endocardial and epicardial activation in patients undergoing CRT. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han C, Pogwizd SM, Killingsworth CR, He B. Noninvasive imaging of three-dimensional cardiac activation sequence during pacing and ventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:1266–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han C, Pogwizd SM, Killingsworth CR, He B. Noninvasive reconstruction of the three-dimensional ventricular activation sequence during pacing and ventricular tachycardia in the canine heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H244–H252. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00618.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Z, Liu C, He B. Noninvasive reconstruction of three-dimensional ventricular activation sequence from the inverse solution of distributed equivalent current density. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2006;25:1307–1318. doi: 10.1109/tmi.2006.882140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pogwizd SM. Focal mechanisms underlying ventricular tachycardia during prolonged ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1994;90:1441–1458. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.3.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pogwizd SM. Nonreentrant mechanisms underlying spontaneous ventricular arrhythmias in a model of nonischemic heart failure in rabbits. Circulation. 1995;92:1034–1048. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.4.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pogwizd SM, McKenzie JP, Cain ME. Mechanisms underlying spontaneous and induced ventricular arrhythmias in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1998;98:2404–2414. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.22.2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang X, Ramachandra I, Liu Z, Muneer B, Pogwizd SM, He B. Noninvasive three-dimensional electrocardiographic imaging of ventricular activation sequence. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H2724–H2732. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00639.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlsson L, Abrahamsson C, Drews L, Duker G. Antiarrhythmic effects of potassium channel openers in rhythm abnormalities related to delayed repolarization. Circulation. 1992;85:1491–1500. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.4.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Batey AJ, Coker SJ. Proarrhythmic potential of halofantrine, terfenadine and clofilium in a modified in vivo model of torsade de pointes. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135:1003–1012. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller WT, Geselowitz DB. Simulation studies of the electrocardiogram. I. The normal heart. Circ Res. 1978;43:301–315. doi: 10.1161/01.res.43.2.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tung L. PhD dissertation. Massachusettes Institute of Technology; Cambridge, MA: 1978. A bidomain model for describing ischemic myocardial D.C. potentials. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang JZ, Williamson SJ, Kaufman L. Magnetic source images determined by a lead-field analysis: the unique minimum-norm least-squares estimation. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1992;39:665–675. doi: 10.1109/10.142641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carlsson L, Abrahamsson C, Andersson B, Duker G, Schiller-Linhardt G. Proarrhythmic effects of the class III agent almokalant: importance of infusion rate, QT dispersion, and early afterdepolarisations. Cardiovasc Res. 1993;27:2186–93. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.12.2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Durrer D, van der Tweel LH. Spread of activation in the left ventricular wall of the dog. II. Activation conditions at the epicardial surface. Am Heart J. 1954;47:192–203. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(54)90249-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Armoundas AA, Feldman AB, Mukkamala R, Cohen RJ. A single equivalent moving dipole model: an efficient approach for localizing sites of origin of ventricular electrical activation. Ann Biomed Eng. 2003;31:564–576. doi: 10.1114/1.1567281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barr RC, Ramsey M, Spach MS. Relating epicardial to body surface potential distributions by means of transfer coefficients based on geometry measurements. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1977;24:1–11. doi: 10.1109/TBME.1977.326201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greensite F, Huiskamp G. An improved method for estimating epicardial potentials from the body surface. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1998;45:98–104. doi: 10.1109/10.650360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gulrajani RM, Roberge FA, Savard P. Moving dipole inverse ECG and EEG solutions. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1984;31:903–910. doi: 10.1109/TBME.1984.325257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He B, Wu D. Imaging and visualization of 3-D cardiac electric activity. IEEE Trans Inf Tech Biomed. 2001;5:181–186. doi: 10.1109/4233.945288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He B, Li G, Zhang X. Noninvasive imaging of cardiac transmembrane potentials within three-dimensional myocardium by means of a realistic geometry anisotropic heart model. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2003;50:1190–1202. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2003.817637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li G, He B. Localization of the site of origin of cardiac activation by means of a heart-model-based electrocardiographic imaging approach. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2001;48:660–669. doi: 10.1109/10.923784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu C, Skadsberg N, Ahlberg S, Swingen C, Iaizzo PA, He B. Estimation of global ventricular activation sequences by noninvasive 3-dimensional electrical imaging: validation studies in a swine model during pacing. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:535–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.01066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mirvis DM, Keller FW, Ideker RE, Cox JW, Jr, Dowdie RF, Zettergren DG. Detection and localization of multiple epicardial electrical generators by a two-dipole ranging technique. Circ Res. 1977;41:551–557. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.4.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohyu S, Okamoto Y, Kuriki S. Use of the ventricular propagated excitation model in the magnetocardiographic inverse problem for reconstruction of electrophysiological properties. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2002;49:509–519. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2002.1001964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skipa O, Nalbach M, Sachse F, Werner C, Dössel O. Transmembrane potential reconstruction in anisotropic heart model. Int J Bioelectromagn. 2002;4:17–18. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pullan AJ, Cheng LK, Nash MP, Bradley CP, Paterson DJ. Noninvasive electrical imaging of the heart: theory and model development. Ann Biomed Eng. 2001;29:817–836. doi: 10.1114/1.1408921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akar FG, Yan GX, Antzelevitch C, Rosenbaum DS. Unique topographical distribution of M cells underlies reentrant mechanism of torsade de pointes in the long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2002;105:1247–1253. doi: 10.1161/hc1002.105231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Asano Y, Davidenko JM, Baxter WT, Gray RA, Jalife J. Optical mapping of drug-induced polymorphic arrhythmias and torsade de pointes in the isolated rabbit heart. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:831–842. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00588-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]