Abstract

Information on the association between alcohol use and Latino sexual risk behavior prior to immigrating to the United States is scarce. Given this population's rapid growth, documenting the influence of alcohol use on Recent Latino Immigrants’ (RLI) sexual risk behaviors is essential. Data prior to immigration were retrospectively collected from 527 RLI ages 18-39. Quantity and frequency of alcohol use during the 90 days prior to immigration and pre-immigration sexual risk behaviors were measured. Structural equation modeling was used to examine the relationships. Males, single participants, and participants with higher incomes reported more alcohol use. Higher alcohol use was associated with lower condom use frequency, having sex under the influence, and more sexual partners among all participants. Results point to the importance of creating interventions targeting adult RLI men, given their likelihood to engage in alcohol consumption, sex under the influence of alcohol, and sex with multiple partners without condoms.

Keywords: alcohol use, Hispanic, Latinos, recent immigrants, sexual risk behavior

During the past two decades, HIV researchers have documented multiple behavioral risk factors associated with HIV infection (Cashman, Eng, Simán, & Rhodes 2011; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010). This research has recently expanded to include social and cultural determinants associated with HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases among Latino immigrants. Most research concerning Latino immigrants has primarily focused on exploring HIV risk behaviors after they have immigrated to the United States and lived there for many years (Shedlin & Shulman, 2006; Zsembik & Fennell, 2005). However, understanding pre-immigration behaviors and investigating if recent immigrants engaged in risky sexual behaviors prior to immigrating will provide health practitioners with an opportunity to plan appropriate and more effective prevention interventions for foreign born immigrants. This type of pre-immigration data can inform the literature and future interventions as pre-immigration lifestyle behaviors may affect post-immigration health behaviors. Findings from extant research have indicated that immigrant Latino males in the United States and their counterparts in Latin America associate condom use with casual sex (Ibanez, Van Oss Marin, Villareal, & Gomez, 2005). Another significant factor is the use of commercial sex workers (CSW) among the Mexican immigrant male population in Durham, NC; use of CSW among this population was shown to increase during the first year of arrival to the United States and continued to increase before peaking at 4 years after arrival (Parrado & Flippen, 2010a). The risky sexual behavior continued for approximately one decade before declining and stabilizing back to the level at the initial time of immigration (Parrado & Flippen, 2010b). Knowledge regarding pre-immigration risky sexual behaviors will assist health care providers in determining how immigration and cultural norms affect sexual health behaviors.

Furthermore, investigating the alcohol use behavior of recent Latino immigrants, most of whom are relatively young and thus at high risk for alcohol abuse, may yield important information on the health status of these immigrants given the deleterious health and social consequences associated with alcohol abuse, including the risk of engaging in unprotected sex (Malow et al., 2012). Documenting the alcohol use and risky sexual behaviors of young adult Latinos will begin to address a gap in the literature; the limited extant literature suggests that the longer Latino immigrants reside in the United States the higher their rates of alcohol abuse (Caetano & Clark, 2003).

Data on pre-immigration condom use among recent Latino immigrants (RLI) from countries other than Mexico is lacking. Parrado and Flippen (2010a) found Mexican migrant workers in the United States to be 10 times more likely to report use of a CSW in the previous year in comparison to their counterparts in Mexico; this behavior could be addressed by understanding social and economic pre-immigration factors. Limited education has been found to be associated with RLI males having less knowledge about HIV. Furthermore, RLI males perceive themselves as having less risk of acquiring HIV and are less likely to use condoms; increases in education and self-efficacy have been associated with increased condom use (Albarracin, Albarracin, & Durantini, 2008). Research on condom use among Latino women in Latin America and the United States has indicated low condom use due to cultural stigma associated with condoms, low levels of education, and being in a stable relationship (Freitas da Silveira et al., 2005).

Research on White non-Latino samples has indicated that alcohol significantly influenced risky sex practices among men and women (sex without condoms, sex with multiple partners, sex for money; CDC, 2010), and alcohol use has been associated with neurological impairment and poor condom use skills (Malow et al., 2012). However, the association between alcohol use and sexual risk behaviors among Latinos prior to immigrating to the United States has rarely been investigated (Shedlin & Shulman, 2006). The scarce research that exists has measured the significance of pre-immigration alcohol use primarily among Mexicans. In fact, among several correlates studied, pre-immigration alcohol use was most consistently associated with post immigration alcohol use in the United States among low-acculturated Mexican immigrants (Loury & Kulbok, 2007). However, acculturation levels among Central Americans have also been significantly associated with alcohol use (Marin & Posner, 1995).

Acculturation is a byproduct of immigration; it is the intersection of two independent cultural environments and is the process by which immigrants change their behaviors, attitudes, and cultures to match those of the host society (Rogler, Cortes, & Malgady, 1991). Latinos with low acculturation tend to embrace their traditional cultural values and beliefs more devoutly (Loury & Kulbok, 2007). Therefore, low-acculturated Latinos, such as RLIs, are more likely to maintain many of the alcohol use and health risk behaviors exhibited prior to immigration. HIV behavioral risk factors have been shown to differ by place of birth (CDC, 2009). Given the varying prevalence of alcohol use in Latin American countries, including the Caribbean, documenting the influence of alcohol use on the sexual risk behaviors of RLI from countries other than Mexico may help create better and better-targeted prevention interventions.

Recent research on Latino immigrants has indicated that long-term separation from family is a major factor influencing problem drinking (Albarran & Nyamathi, 2011), and research with recent Latino immigrants has found that time spent in the United States and education influence sexual behaviors (Cashman et al., 2011). Most studies on Latino sexual risk behaviors and alcohol use examine behavior after U.S. immigration, where acculturation becomes a factor (Zsembik & Fennell, 2005). Our study, guided by a theoretical structural equation model based on the extant literature, hypothesized the correlation among pre-immigration high use of alcohol with multiple sexual partners and lower rates of condom use. Research that focuses on pre-immigration factors affecting alcohol use and HIV risk behaviors is needed to obtain more effective methods to complete health profiles on recent Latino immigrants. These data can then be used to develop and enhance culturally sensitive and effective HIV prevention programs in areas such as Miami-Dade County, where 49% of the population was born outside of the United States and 65% of the population is of Latino descent (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010).

The study of recent immigrants’ risky sexual behaviors in South Florida is relevant due to the large number of foreign-born individuals in Miami-Dade County who were born in the Caribbean, a region with the highest HIV seroprevalence rate in the Western Hemisphere (Caribbean Epidemiology Centre, 2007). Recent immigrants may have pre-immigration assets that can protect them from engaging in risky sexual behaviors and vice versa. Knowledge about pre-immigration protective assets and how these factors may interact with the acculturation process has a public health impact for communities that have large populations of immigrants and migrants.

Exploring the influence of alcohol consumption on risky sexual behaviors in RLI is significant because drinking is socially acceptable and encouraged as part of manhood in Latin America (Kunitz, Levy, McCloskey, & Gabriel, 1998). Cultural acceptance of alcohol use has major consequences that may be under documented due to the lack of a monitoring infrastructure in Latin America. For example, in Latin America and the Caribbean, 4.5% of all deaths are attributed to alcohol use compared to 1.3% in industrialized regions of the world (Kunitz et al., 1998). Additionally, alcohol use has been associated with high levels of domestic violence experienced by Latin American women and their children (Kunitz et al., 1998). Hence, the goal of our study was to examine the correlates of pre-immigration HIV risk behaviors in RLI. Specifically, the study examined how illegal drug use, alcohol use, and other social determinant correlates influenced RLI sexual risk behaviors. It was hypothesized that higher frequency of alcohol use would be associated with lower rates of condom use and more sexual partners during the 12 months prior to emigration (see Conceptual Model, Figure 1). Additionally, it was expected that exchanging sex for money (paying or receiving money or drugs) prior to immigration would be associated with higher levels of alcohol use.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model

Methods

Participants

Data for our study originated from an investigation of the influence of pre-immigration factors on health behaviors of RLI in South Florida (De La Rosa, Babino, Rosario, Martinez, & Aijaz, 2011). Our analyses used the baseline data of a 3-year longitudinal study. In accordance with our study's inclusion criteria, participants were 18-34 years of age and had recently (less than 1 year) immigrated to the United States from a Latin American country. The study was approved by, and conducted in compliance with, the institutional review board (IRB) at a large university in Miami, Florida. Participants were recruited through electronic bulletin boards/Websites, community health fairs, neighborhood events, and announcements posted at several community-based agencies providing services to refugees, asylum seekers, and other documented/undocumented immigrants.

Undocumented Latino immigrants in the United States are a hidden population due to their legal status. Therefore, respondent-driven sampling (RDS) was the primary recruitment strategy chosen for the study. RDS is effective when recruiting participants from hidden or difficult-to-reach populations (Salganik & Heckathorn, 2004). Given South Florida's demographics and that Latinos represent a large portion of the nation's undocumented immigrant population, RDS was the most appropriate sampling method. Each initial participant (the seed) was asked to refer three eligible individuals in his or her social network. The procedure was followed for seven legs for each initial participant, and then a new seed would begin, thus limiting the number of participants who were socially interconnected (Salganik & Heckathorn, 2004).

All interviews were conducted in Spanish at locations convenient for participants (61% in homes, and 25% in local restaurants/coffee shops). Interviewers were bilingual male and female Latinos with undergraduate or graduate degrees. The sample included 527 RLI. The average age was 27 (M = 26.9, SD = 4.98 years). Men comprised 54.6% of the sample; women comprised 45.4%. More than half (53.5%) were single; 33.8% were married or in common law/living as married relationships; and 12.7% were separated, divorced, or widowed. In terms of highest education level reached, the majority of the sample had earned a high school diploma (18.4%) or had some college education (33.7%). Fifty-two percent were unemployed. Participants’ average income during the 12 months prior to U.S. immigration was approximately $4,840 (USD; SD = $10,236).

Participants’ length of time in the United States ranged from 1 month to 12 months (M = 6.73 months, SD = 3.10 months). The motives for immigration were economic reasons (58.8%), reuniting with family members (23%), political issues (8%), and other reasons (10.2%). Approximately 69.7% of participants had documented immigration status; the remaining 30.3% were undocumented.

Cubans and Colombians represented the majority of the sample at 42.1% and 17.6%, respectively. Participants from Guatemala, Venezuela, and Peru each comprised approximately 8.9%. Participants from Argentina, El Salvador, and the Dominican Republic each represented less than 2% of the sample.

Measures

Sociodemographic variables

A demographic form was used to assess participants’ gender, age, country of origin, marital status, length of time in the United States, education level (1 = less than high school, 2 = high school, 3 = some training/college after high school, 4 = bachelor's degree, 5 = graduate/professional studies), and participants’ income during the 12 months prior to immigrating to the United States. The income variable was transformed into U.S. dollars utilizing the official exchange rate and converted into quartiles to facilitate analyses (i.e., 0 = $0 to $240, 1 = $248 to $1,200, 2 = $1,266 to $5,000, 3 = greater than $5,184).

Alcohol use

The Timeline Follow-Back Interview (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1992) was administered to document quantity and frequency of alcohol use during the 90 days prior to immigration. TLFB data is collected using a calendar format to provide temporal cues (e.g., holidays, special occasions) to assist in recall of days when substances were used. The TLFB Spanish version is considered a reliable and valid measure with Latino populations (Dillon, Turner, Robbins, & Szapocznik, 2005). Frequency of alcohol use was indicated by alcohol use events during 90 days prior to immigration. Quantity of alcohol use was represented by the average number of drinks reported per drinking day during the 90-day assessment window.

The Alcohol Use Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders, & Monteiro, 2001) was used to measure problems related to alcohol consumption, abuse, and dependence during the 12 months prior to immigration (hazardous/harmful alcohol use). A psychometrically sound (Cronbach's alpha coefficient of .95) Spanish version of the AUDIT was used; total score was calculated by summing all 10 items of the scale (Babor et al., 2001).

A latent construct of alcohol use was hypothesized to consist of three observed measures, including TLFB measurements of (a) frequency, (b) quantity, and (c) AUDIT total scores. A latent construct of alcohol use was preferred over separate analyses of alcohol-use indicators because these indicators were correlated and a parsimonious analytic model was needed.

Pre-immigration sexual risk behavior

Pre-immigration sexual risk behavior was measured using an IRB-approved translated Risk Behavior Assessment Scale (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1993). Participants were asked to report their sexual risk behaviors during both the previous 90 days and the last 12 months prior to immigration. Four variables were selected as outcome variables to explore pre-immigration sexual risk behavior in this sample: (a) number of sexual partners 90 days prior to migration, (b) whether sex was exchanged for money or drugs, (c) whether sex was performed under the influence of drugs or alcohol, and (d) whether condoms were used during sex during the 90 days prior to migration.

Participants reported if sex was exchanged for drugs or money during the 12 months prior to immigration (During 12 months prior to coming to the U.S., did you give drugs in exchange for sex or receive drugs in exchange for sex? During 12 months prior to coming to the U.S., did you give alcohol in exchange for sex or receive alcohol in exchange for sex?). The responses were merged and coded as one dichotomous variable to reflect if the participant ever gave or received drugs or alcohol in exchange for sex (coded 1 = exchanged drugs or alcohol for sex; or 0 = did not exchange drugs or alcohol for sex).

For sex under the influence, participants were asked two separate questions: During sex with your primary partner in the 12 months prior to immigration, were you (a) ever under the influence of drugs and (b) ever under the influence of alcohol? These responses were merged and coded as one dichotomous variable (coded 1 = had sex under the influence of drugs/alcohol; or 0 = did not have sex under the influence of drugs/alcohol).

Higher rates of unprotected sex (sexual acts without a condom 90 days prior to immigration) represented high-risk sexual behavior. Similar to the alcohol use variable, a latent construct was hypothesized to consist of three observed indicators for condom use: condom use during (a) anal, (b) vaginal, and (c) oral sex.

Data Analyses

Data analysis consisted of three steps. First, continuous variables were analyzed to determine whether they violated the assumption of normality (Kline, 2005). A positively skewed distribution was found for alcohol use quantity and number of sexual partners. A square-root data transformation was used to arrive at an approximately normal distribution for both variables and used in subsequent analyses.

Second, confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted to test if hypothesized indicators adequately represented the latent constructs of alcohol use and condom use. Researchers evaluated the measurement model (and the overall structural model, see Figure 1) using the comparative fit index (CFI) with values above .95 representing excellent fit and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), where values below .08 represent adequate fit and values below .05 represent excellent fit (Hancock & Freeman, 2001).

Third, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine whether and how pre-immigration alcohol use was associated with pre-immigration sexual risk behaviors. SEM was used because it is a data analytic technique that simultaneously estimates associations between observed and latent variables in models involving multiple dependent variables (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, 2005). The theoretical model in our study had two latent variables: (a) alcohol use, which was a combined score of alcohol frequency, alcohol quantity, and the AUDIT score; and (b) condom use, which was a combined score from the number of anal, vaginal, and oral sexual acts performed with a condom (see Figure 1). Additionally, one of the primary advantages of SEM over multiple regression techniques is that SEM models control for measurement error (Frazier, Tix, & Barron, 2004). SEM also allows the researcher to simultaneously account for the role of sociodemographic variables (gender, age, marital status, annual income, and education) as covariates in the construct. For this reason, Multiple Indicators, Multiple Causes (MIMIC) modeling was used to include covariates in the model (Bollen, 1989). Through MIMIC modeling, sexual risk behavior and alcohol use were regressed on each covariate.

Results

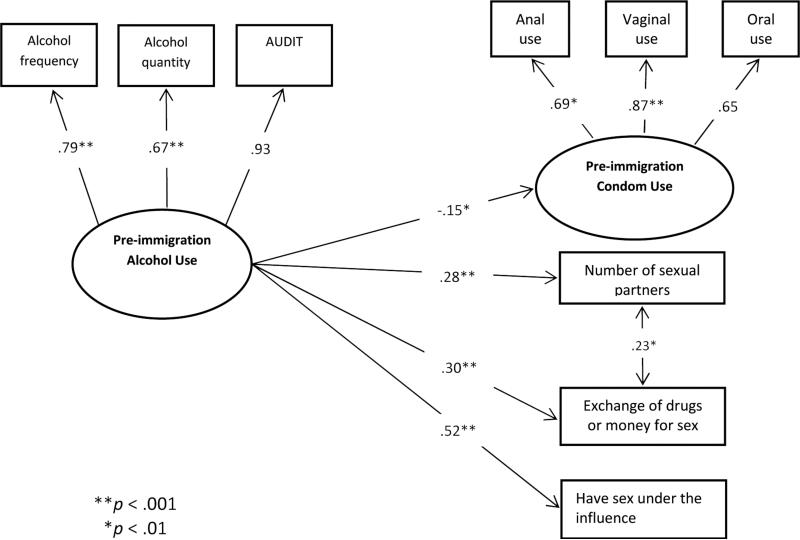

During the 12 months prior to immigration, 2.4% of women reported having more than three sexual partners, in contrast to 33% of men. Three months prior to immigration, the number of sexual partners for both men and women decreased: 2.1% of women and 9.9% of men reported having more than three partners. Only 15 (2.8%) of the participants reported exchanging sex for money. During the last sexual encounter with a primary partner prior to immigration, 4.2% of women and 12.2% of men reported having sex under the influence of alcohol, while 0.8% of women and 7.3% of men reported drug use prior to the encounter. For vaginal sex, 39.2% of respondents reported never using condoms and 33.6% always used condoms with primary as well as casual partners. During oral sex, 66.2% never used condoms compared to 10.2% who always used condoms; for anal sex, 49.7% never used condoms compared to 27.3% who always used condoms. The SEM model (Figure 2) demonstrated adequate model fit, χ2 (28, N = 525) = 46.24, p = .016; CFI = .978; RMSEA = .04. Results from SEM analysis are found below.

Figure 2.

Path Model Results

Pre-immigration alcohol use

Because three indicators were included in the alcohol-use measurement model, it was just-identified (Figure 2). Fit statistics are not available for such models. Factor loadings suggested that three indicators loaded strongly onto the latent construct (β estimates ranging from .67 to .93). AUDIT total scores explained 86% of variability in alcohol use. Sixty-six percent was explained by quantity of alcohol use and 41% of variability was explained by frequency of alcohol use.

Pre-immigration condom use

The condom use measurement model was just-identified as well (Figure 2). Factor loadings suggested that three indicators loaded strongly onto the latent construct (β estimates ranging from .65 to .87). Seventy-four percent of variability in condom use was explained by condom use during anal sex. Sixty-six percent was explained by condom use during vaginal sex. Thirty-eight percent of variability in condom use was explained by condom use during oral sex.

Alcohol use and sexual risk behavior

In relation to condom use, higher levels of pre-immigration alcohol use was associated with lower condom use frequency [β = (-.15), p < .01], more sexual partners (β = .28, p < .001), more frequent exchanges of sex for money or drugs (β = .30, p < .001), and more sexual acts under the influence (β = .52, p < .001; Figure 2). As expected, exchanging sex for money or drugs was positively related with number of sexual partners (β = .23, p < .01). No other sexual risk behaviors were significantly correlated.

High-risk sexual behavior and alcohol use by sociodemographic covariates

Age and marital status were associated with condom use (Table 1). Older participants and participants who were married reported less condom use frequency (β = [-.22] and [-.18], respectively, p < .01). In regard to gender, men had a higher risk of having multiple partners and having sex under the influence (β = .24 and .19 respectively, p < .05). Lastly, education was associated with having a higher number of partners (β =.09, p < .01). Participants who reported higher levels of education indicated more sexual partners. Gender, marital status, and annual income were associated with alcohol use (β = .33, [-.16], and .24, respectively, p < .05). Males, single participants, and participants with higher incomes reported more alcohol use.

Table 1.

Covariates of High Risk Sexual Behavior

| Risk Behavior (Standardized Estimate, p) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condom use | Number of partners | Exchanging sex for drugs or money | Sex under the influence | Alcohol Use | |

| Gendera | .06 | .24** | .23 | .19** | .33* |

| Age | (-.22)* | .02 | (-.04) | (-.03) | .00 |

| Marital Statusb | (-.18)* | .01 | (-.09) | (-.06) | (-.16)* |

| Annual Incomec | .05 | (-.08) | .12 | .08 | .24* |

| Educationd | .01 | .09* | (-.15) | .12 | .05 |

Note.

p < .01

p < .05

0 = female, 1 = male

1 = married, 2 = separated, 3 = common law/living as married, 4 = divorced, 5 = single/never married, 6 = widowed

0 = $0 to $240, 1 = $248 to $1,200, 2 = $1,266 to $5,000, 3 = $5,184+.

1 = less than high school, 2 = high school, 3 = some training/college after high school, 4 = bachelor's degree, 5 = graduate/professional studies.

Discussion

Results from our study suggested that pre-immigration alcohol use was more prevalent among Latino men than among Latina women. This finding could be due to the cultural beliefs of machismo and acceptance of social drinking among males (Loury & Kulbok, 2007). Our study also illustrated the relationship between alcohol use and multiple sexual-partners among Latino men before immigration to the United States. This association points to the importance of targeting adult RLI men, given their likelihood to engage in alcohol-consumption and sex with multiple partners without using condoms. Additionally, among Latino immigrants, alcohol has been reported to be the drug of choice because there is low stigma associated with alcohol consumption by men (Shedlin & Shulman, 2006). The results of the study suggest that by targeting RLI males and their potentially risky health behaviors, public health practitioners may have a significant impact in this community. Early intervention is critical, particularly because Latino men and women are both more likely to engage in multiple sexual relationships while in the United States in comparison to their home countries (CDC, 2010).

Condom use appeared to be associated with whether the partner was casual or permanent (Ibanez et al., 2005). Therefore, condom use in non-committed relationships may be lower to avoid revealing to partners that the relationship is casual. These findings suggest that there is a need to target men and women to educate them about the link between alcohol use and the probability of engaging in unprotected sex. Although it is not possible to make broad generalizations from this study given that most participants were of Caribbean descent, our data indicated that men were more likely to engage in sex with multiple partners, particularly if they reported high socioeconomic status. Our results are important for prevention programs targeting RLI and their HIV vulnerability in the United States. The relatively low use of condoms among participants was congruent with rates reported in other studies. Due to the stigma of condom use in Latin America, men and women with low education and men and women in stable relationships are less likely to use condoms; because condom use is culturally associated with sex with CSWs, Latino men and women may not use condoms with permanent partners (Freitas da Silveira et al., 2005).

Sex with partners who had HIV or had engaged in illicit drug use were not considered in this analysis as HIV prevalence and drug use were low in this population (4% and 13%, respectively). Furthermore, although condom use was related to relationship status in our study, the overall rate of condom use among men and women was relatively low during the last 12 months before immigrating. Our study suggests that HIV infection among Latinos pre-immigration may be associated with unprotected heterosexual sex and having unprotected sex with multiple sexual partners. Despite a small percentage of this sample engaging in sex for money or drugs during the 12 months pre-migration, women in particular may have exchanged sex for goods or room and board for themselves or their children (Freitas da Silveira et al., 2005) and may also have been at high risk of acquiring HIV from their male partners.

In our study, men were more likely than women to engage in alcohol use and have multiple sexual partners prior to immigration; however, the literature has suggested that time spent in the United States, for women in particular, increased alcohol use among Latina immigrants (Marin & Posner, 1995). Researchers may want to consider further examining the protective pre-immigration factors of Latinas and how these factors can be promoted among large Latino communities in the United States. However, according to our study, this may not necessarily be true for men. Future longitudinal analysis of the data will provide evidence on whether there is an association between HIV risk behaviors, HIV infection, and time spent in the United States for male RLI.

Findings from this cross-sectional analysis of data from a non-representative Latino sample are not generalizable because Latinos from different geographic regions may have dissimilarities in some cultural measures such as acculturation and immigration status. Thus, these findings need to be confirmed or refuted by future research. Additionally, this study has limitations typical of others that use self-reported data on socially non-desirable behaviors, including possible recollection bias from the 12-month period examined. Moreover, participants, particularly women, may have underreported having multiple partners.

Findings reported in our study provide a starting point for future research that can further explore the trajectories of risky sexual behaviors among Latinos prior to immigrating to the United States. These results also contribute to the limited literature and knowledge on patterns of risky sexual behavior of Latino immigrants prior to U.S. immigration. Forthcoming research on pre- and post-immigration risky sexual behaviors will provide valuable longitudinal information for nurses, health care providers, and public health practitioners in community settings on factors that influence the risky sexual patterns of Latino immigrants in comparison to their U.S.-born counterparts. This research has public health ramifications as it can inform future prevention and education programs for a large ethnic minority group in the United States.

Clinical Considerations.

Community health care providers and community nurses can solicit information and evaluate recent immigrant pre-immigration health behaviors in order to facilitate more tailored interventions to this population.

Culturally relevant and culturally sensitive trainings with immigrants for nurses and health care providers should include information regarding norms and beliefs that can have an effect on sexual behaviors.

Soliciting alcohol use (frequency and quantity) information from recent Latino immigrant patients may provide nurses and health care professionals with awareness of the likelihood that these patients may also exhibit other health risk behaviors associated with alcohol use (e.g., sex under the influence of alcohol). Approaching male Latinos is particularly important due to their socially acceptable use of alcohol.

Effective HIV risk behavior prevention programs for recent Latino immigrants hinge upon the abilities of community health workers, such as community nurses and other health care practitioners, to identify risky health behaviors during contact with patients.

Acknowledgements

The project described was supported by Award Number P20MD002288 from National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Albarracin J, Albarracin D, Durantini M. Effects of HIV-prevention interventions for samples with higher and lower percent of Latinos and Latin Americans: A meta-analysis of change in condom use and knowledge. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12(4):521–543. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9209-8. doi:10.1007/s10461-007-9209-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albarran CR, Nyamathi A. HIV and Mexican migrant workers in the United States: A review applying the vulnerable populations conceptual model. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2011;22(3):173–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2010.08.001. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The alcohol use disorders identification test. (2nd ed.) 2001 Retrieved from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2001/who_msd_msb_01.6a.pdf.

- Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. John Wiley and Sons; New York, NY: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Clark CL. Acculturation, alcohol consumption, smoking, and drug use among Hispanics. In: Marin G, editor. Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2003. pp. 223–239. [Google Scholar]

- Caribbean Epidemiology Centre The Caribbean HIV/AIDS epidemic and the situation in member countries of the Caribbean Epidemiology Centre, February, 2007. 2007 Retrieved from http://www.carec.org/data/caribbean-population-distribution-pyramids/2005.

- Cashman R, Eng E, Simán F, Rhodes SD. Exploring the sexual health priorities and needs of immigrant Latinas in the Southeastern United States: A community-based participatory research approach. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2011;23(3):236–248. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.3.236. doi:10.1521/aeap.2011.23.3.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Diagnosis of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States and dependent areas, HIV Surveillance Report, Vol. 21. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2009report/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV among Hispanics/Latinos, 2010. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/hispanics/resources/factsheets/pdf/hispanic.pdf.

- De La Rosa M, Babino R, Rosario A, Martinez NV, Aijaz L. Challenges and strategies in recruiting, interviewing, and retaining recent Latino immigrants in substance abuse and HIV epidemiologic studies. American Journal of Addictions. 2011;21(1):11–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00193.x. doi:10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon FR, Turner CW, Robbins MS, Szapocznik J. Concordance among biological, interview, and self-report measures of drug use among African American and Hispanic adolescents referred for drug abuse treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19(4):404–413. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.404. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier PA, Tix AP, Barron KE. Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;15(1):115–134. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.51.1.115. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas da Silveira M, Silva dos Santos I, Béria JU, Horta BL, Tomasi E, Victora CG. Factors associated with condom use in women from an urban area in southern Brazil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2005;21(5):1557–1564. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2005000500029. doi:10.1590/S0102-311X2005000500029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE, Tatham RL. Multivariate data analysis. 6th ed. Pearson Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 2005. Structural equation modeling: An introduction. pp. 705–769. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock GR, Freeman MJ. Power and sample size for the root mean square error of approximation test of not close fit in structural equation modeling. Educational Psychology Measurement. 2001;61(5):741–758. doi:10.1177/00131640121971491. [Google Scholar]

- Ibanez GE, Van Oss Marin B, Villareal C, Gomez CA. Condom use at last sex among unmarried Latino men: An event level analysis. AIDS and Behavior. 2005;9(4):433–441. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9015-0. doi:10.1007/s10461-005-9015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kunitz SJ, Levy JE, McCloskey J, Gabriel KR. Alcohol dependence and domestic violence as sequelae of abuse and conduct disorder in childhood. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1998;22(11):1079–1091. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(98)00089-1. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(98)00089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loury S, Kulbok P. Correlates of alcohol and tobacco use among Mexican immigrants in rural North Carolina. Family Community Health. 2007;30(3):247–256. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000277767.00526.f1. doi:10.1097/01.FCH.0000277767.00526.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malow RM, Dévieux JG, Stein JA, Rosenberg R, Lerner BG, Attonito J, Villalba K. Neurological function, information-motivation-behavioral skills factors, and risk behaviors among HIV-positive alcohol users. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16(8):2297–308. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0246-6. doi:10.1007/s10461-012-0246-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, Posner SF. The role of gender and acculturation on determining the consumption of alcoholic beverages among Mexican-Americans and Central Americans in the United States. International Journal of Addictions. 1995;30(7):779–794. doi: 10.3109/10826089509067007. doi:10.3109/10826089509067007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse . Risk behavior assessment. 3rd ed. Author; Rockville, MD: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Parrado EA, Flippen CA. Migration and sexuality: A comparison of Mexicans in sending and receiving communities. Journal of Social Issues. 2010a;66(1):175–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01639.x. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01639.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrado EA, Flippen CA. Community attachment, neighborhood context, and sex worker use among Hispanic migrants in Durham, North Carolina, USA. Social Science & Medicine. 2010b;70:1059–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.017. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogler LH, Cortes DE, Malgady RG. Acculturation and mental health status among Hispanics: Convergence and new directions for research. American Psychologist. 1991;46(6):585–597. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.46.6.585. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.46.6.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salganik MJ, Heckathorn DD. Sampling and estimation in hidden populations using respondent driven sampling. Sociological Methodology. 2004;34(1):193–240. doi:10.1111/j.0081-1750.2004.00152.x. [Google Scholar]

- Shedlin MG, Shulman LC. New Hispanic migration and HIV risk in New York. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies. 2006;4(1):47–58. doi:10.1300/J500v04n01_04. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen J, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biological methods. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau State and county quick facts. 2010 Retrieved from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/12/12086.html.

- Zsembik BA, Fennell D. Ethnic variation in health and the determinants of health among Latinos. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61(1):53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.040. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]