Abstract

Diabetes often leads to a number of complications involving brain function, including cognitive decline and depression. In addition, depression is a risk factor for developing diabetes. A loss of hippocampal neuroplasticity, which impairs the ability of the brain to adapt and reorganize key behavioral and emotional functions, provides a framework for understanding this reciprocal relationship. The effects of diabetes on brain and behavioral functions in experimental models of type 1 and type 2 diabetes are reviewed, with a focus on the negative impact of impaired hippocampal neurogenesis, dendritic remodeling and increased apoptosis. Mechanisms shown to regulate neuroplasticity and behavior in diabetes models, including stress hormones, neurotransmitters, neurotrophins, inflammation and aging, are integrated within this framework. Pathological changes in hippocampal function can contribute to the brain symptoms of diabetes-associated complications by failing to regulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-axis, maintain learning and memory and govern emotional expression. Further characterization of alterations in neuroplasticity along with glycemic control will facilitate the development and evaluation of pharmacological interventions that could successfully prevent and/or reverse the detrimental effects of diabetes on brain and behavior.

Keywords: diabetes, hippocampus, neurogenesis, neuroplasticity, depression, cognition

1. Introduction

Diabetes is a chronic metabolic disorder characterized by abnormally high plasma glucose levels, also known as hyperglycemia. According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2011), over 220 million people around the world have diabetes. In the United States, approximately 25.8 million children and adults have diabetes, a statistic that represents 8.3% of the population (ADA, 2011). Moreover, the number of people suffering from diabetes has been estimated to likely double by the year 2030 due to urbanization, obesity and aging (Wild et al., 2004).

Two main forms of diabetes exist in humans: diabetes mellitus type 1 (T1D) and diabetes mellitus type 2 (T2D). The two classifications differ based on the etiology of the hyperglycemia and the person's response to insulin. T1D, a disease characterized by insulin deficiency, results from autoimmune destruction of the insulin-producing pancreatic beta cells. With onset typically during childhood or early adulthood, T1D is fatal in the absence of insulin replacement therapy. T1D represents approximately 5-10% of all diagnosed cases of diabetes. T2D, on the other hand, accounts for 90-95% of cases (NDIC, 2011) and is characterized by decreased insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues and resultant perturbation of insulin secretion. This derangement is commonly associated with other metabolic disturbances like hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and obesity.

Diabetes can lead to a number of secondary complications affecting multiple organs in the body including the eyes, kidney, heart, and brain. The most common diabetic brain complications include cognitive decline and depression. The incidence of cognitive decline, measured by behavioral testing, may be as high as 40% in people with diabetes (Dejgaard et al., 1991), and as many as 39% of a sample of people with diabetes in one study indicated having a subjective feeling of cognitive decline (Brismar et al., 2007). A systematic review of longitudinal studies reported an overall 50-100% increase in the incidence of dementia in people with diabetes (Biessels et al., 2006). Two more recent meta-analyses also concluded that diabetes is associated with lower cognitive performance and increased risk for dementia (Gaudieri et al., 2008; Lu et al., 2009). A recent review reported impaired cognition with effect sizes of 0.3-0.8 SD units in people with T1D compared to non-diabetic controls and 0.25-0.5 SD units in people with T2D compared to non-diabetic controls (McCrimmon et al., 2012).

In addition to symptoms of cognitive decline, both T1D and T2D are associated with a higher prevalence of depression. A recent review reported that the prevalence of depression in T1D was 12% versus 3.2% in the non-diabetic population (range 5.8-43.3% versus 2.7-11.4%). Similarly, the prevalence of depression in T2D was 19.1% versus 10.7% in the general population (range 6.5-33% versus 3.8-19.4%) (Roy and Lloyd, 2012). The relationship between diabetes and depression is reciprocal as depression is also considered a risk factor for the development of diabetes (Renn et al., 2011). Comorbid depression and diabetes is associated with poor self-care, lack of exercise, and nonadherence to dietary or medication routines, leading to inadequate glycemic control. The treatment of depressive symptoms alone may produce benefits but, nevertheless, still not necessarily improve glycemic control (Petrak and Herpertz, 2009).

Although the mechanisms responsible for producing the high rates of depression and dementia in diabetes are not well understood, the overlap of numerous physiological and non-physiological factors likely account for the pathogenesis of their comorbidity (Ismail, 2010). Non-physiological factors, such as sedentary lifestyle, diet, lack of self-care and history of substance abuse, contribute to the development of diabetes. There is also an emotional burden related to managing diabetes that is stressful for many patients. Insulin resistance in the brain, in addition to the periphery, has emerged as a potential physiological link for T2D with both depression and dementia (Silva et al., 2012). Inadequate signaling from the absence of insulin may produce a similar set of physiological disturbances in T1D (Korczak et al., 2011). Diabetes and depression are also associated with hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (Champaneri et al., 2010). Whether HPA axis hyperactivity in diabetes might cause depression, or exacerbate certain depressive behaviors is unclear, but abnormal HPA responses have been proposed as a biomarker that is ameliorated by antidepressant treatment in patients that recover from depression (Ising et al., 2007). Likewise, increased inflammation has been associated with the pathogenesis of both diabetes and depression (Haroon et al., 2012; Osborn and Olefsky, 2012; Stuart and Baune, 2012). Diabetes, and the effects of insulin, have been associated with alterations of the same neurotransmitters (dopamine and serotonin), neurotrophins (brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)) and cell signaling mechanisms (alpha serine-threonine protein kinase (Akt); insulin growth factor-1 (IGF-1)) that have been implicated in depression (Duman and Monteggia, 2006) and the effects of antidepressants (Hoshaw et al., 2005). Even though the common occurrence of depression and diabetes is expected from many overlapping predisposing physiological and non-physiological factors, it is still unclear which mechanisms are most important or which patients will develop comorbid complications.

Evidence from animal studies can help elucidate mechanisms responsible for depression in humans with diabetes leading to identifying biomarkers and new treatments. However, studying models of depression in animals differs greatly from studying clinical depression in humans. The diagnosis of depression in humans requires meeting DSMIV-TR criteria for depression, which includes subjective report of feeling sad and/or decreased interested in pleasurable activities. Animals, on the other hand, cannot be diagnosed with depression. Instead, scientists can only measure symptoms or behaviors that represent animal analogs or from which they can infer similarity to symptoms of depression in humans.

The key to understanding the link between diabetes with cognitive deficits and mood disorders may lie in the process of neuroplasticity, or the structural remodeling of the brain after exposure to stress or disease. Prolonged exposure to stress has been shown to lead to a series of neuroplastic changes in brain regions that are especially sensitive to stress, such as the hippocampus. Structural remodeling engages neuroplasticity in response to environment, diet, immune and endocrine stimuli. Neuroplasticity is protective and initially promotes adaptations but when adaptive changes become prolonged, they produce a continuous burden that could lead to disease vulnerability called allostatic overload (McEwen, 2006). Morphologically, stress reduces the expression of dendritic spines and synaptic proteins and increases markers of apoptosis in the hippocampus. Electrophysiological evidence of diminished hippocampal function is obtained from studies showing reduced or absent long-term potentiation, a putative model of learning and synaptic plasticity. Clinically, reduced volume of the hippocampus from structural magnetic resonance imaging studies in depression and diabetes has provided evidence of similar deteriorating brain morphology as shown in animals exposed to stress (Eker and Gonul, 2010; McIntyre et al., 2010; Tata and Anderson, 2010).

An important function of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus is in neurogenesis. The dentate gyrus is one of two established neurogenic zones in the brain, in addition to the subventricular zone, that continuously generates new neuronal cells throughout life (Leuner and Gould, 2010). Hippocampal neurogenesis is diminished by exposure to environmental stress, HPA axis hyperactivity and increased inflammation (Schoenfeld and Gould, 2012; Song and Wang, 2011; Zunszain et al., 2011). On the other hand, chronic exposure to antidepressant treatments increases hippocampal neurogenesis and may be responsible for the emergence of abnormal emotional behaviors in animals exposed to models of depression (Airan et al., 2007; Dranovsky and Hen, 2006; Jayatissa et al., 2008). Changes in neurogenesis alter a number of key functions of the hippocampus, such as learning and memory, affective expression and regulation of the HPA axis (Koehl and Abrous, 2011; Snyder et al., 2011). In the non-diabetic literature, extensive evidence supports the role of hippocampal neurogenesis in various types of learning and memory, including pattern separation (Bekinschtein et al., 2011; Clelland et al., 2009) and spatial memory (Goodman et al., 2010; Snyder et al., 2005). Further, “effortful learning” as well as learning spaced over a longer period of time improves memory as well as increases the survival of new hippocampal neurons (Shors et al., 2012; Sisti et al., 2007).

Hippocampal neuro genesis and neuroplasticity appears to be sensitive to many pathogenic and treatment factors that are associated with the comorbidity between diabetes and depression. A growing preclinical literature provides ample evidence that diabetes negatively affects the morphological integrity of the hippocampus and that reduced hippocampal neurogenesis, in concert with deficits of other forms of neuroplasticity, may contribute to comorbid cognitive and mood symptoms in diabetes. The goal of this review is to: 1) integrate existing information about the effects of diabetes on hippocampal neurogenesis and how altered neurogenesis may affect behavior, 2) review the effects of treatments in rodent models of diabetes that impact both hippocampal neurogenesis and behavioral outcomes, and 3) determine the necessary steps to move forward towards translation of the basic science research into humans.

2. Search methods

The keywords “diabet* neurogen*” were searched in PUBMED, MEDLINE, andEMBASE databases with the following limits: English language and published in the last 10years (2001 to 2012). Article titles and abstracts were screened and potentially relevant articleswere retrieved and evaluated. This review included published studies that examined the effect ofdiabetes on hippocampal neurogenesis (see Table 1), and it summarizes and synthesizes thehighlights of selected articles. Other forms of hippocampal neuroplasticity (i.e. apoptosis,dendritic branching, long term potentiation) and translation of research into humans are alsobriefly discussed. Most of the behavioral studies reviewed involved the evaluation of hippocampal neurogenesis in a model of experimental diabetes.

Table 1. Effects of Experimental Diabetes Models on Hippocampal Neurogenesis.

| Mod. | Spec. | Proliferation | Differentiation | Survival | Assoc. Behavior | Treatments | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1D Models | |||||||

| STZ | Mice | Decreased | Imp. Cog. | Alvarez et al. (2009) | |||

| STZ | Mice | Decreased | Balu et al. (2009) | ||||

| STZ | Mice | Decreased | Decreased | Fluoxetine | Beauquis et al. (2006) | ||

| STZ | Mice | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased | EE | Beauquis et al. (2010) | |

| STZ | Mice | Decreased | Imp. Cog. | Mifepristone | Revsin et al. (2009) | ||

| STZ | Mice | Decreased | Estradiol | Saravia et al. (2004) | |||

| STZ | Mice | Decreased | Estradiol | Saravia et al. (2006) | |||

| STZ | Rat | Decreased | Jackson-Guilford et al. (2000) | ||||

| STZ | Rat | Decreased | Imp. Cog. | EE | Piazza et al. (2010) | ||

| STZ | Rat | Decreased | No change | Decreased | Imp. Cog. | HPA Mod. | Stranahan et al. (2008) |

| STZ | Rat | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased | Dep. Beh. | Aminoguan. | Wang et al. (2009) |

| STZ | Rat | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased | Zhang et al. (2008) | ||

| NOD | Mice | Decreased | No change | Decreased | Beauquis et al. (2008) | ||

| T2D Models | |||||||

| db/db | Mice | Decreased | No change | Decreased | Imp. Cog. | HPA Mod. | Stranahan et al. (2008) |

| db/db | Mice | Increased | No change | GLP-1 anal. | Hamilton et al. (2011) | ||

| GK | Rat | Increased | Increased | No Change | Beauquis et al. (2010) | ||

| GK | Rat | Increased | Decreased | Lang et al. (2009) | |||

| ZD | Rat | Decreased | Decreased | Exercise | Yi et al. (2009) | ||

| HFD | Rat | Decreased | Lindqvist et al. (2006) | ||||

| HFD | Mice | Decreased | Decreased | Hwang et al. (2008) | |||

| HFD | Mice | Decreased | Park et al. (2010) | ||||

| HFD | Rat | No effect | CB1 inv. agonist | Rivera et al. (2011) | |||

| HFD | Mice | Decreased | Age | Boitard et al. (2012) | |||

| HFD | Mice | Increased | GLP-1 anal. | Hamilton et al. (2011) | |||

Abbreviations: Mod., model; Spec., species; Assoc., associated; STZ, streptozotocin; NOD, non-obese diabetic; GK, Goto-Kakizaki; ZD, Zucker Diabetic; Imp. Cog., impaired cognition; Dep. Beh., depressive behavior; EE, environmental enrichment; HPA Mod., HPA modulation; Aminoguan., aminoguanidine

3. An overview of neurogenesis and measurement methods

Just a few years ago, neurogenesis was believed to occur only in the developing mammalian brain. However, with advances in cell labeling techniques, it was confirmed and accepted that neurogenesis is maintained and continues throughout adulthood in high abundance in specific brain regions, such as the hippocampus and the subventricular zone serving the olfactory bulbs (Elder et al., 2006; Taupin, 2006). Reports of neurogenesis in other areas of the brain exist, but the presence of constitutive and normally-occurring adult neurogenesis in brain regions other than the hippocampus and olfactory bulb is not well established (Balu and Lucki, 2009). Due to the hypothesized role of the hippocampus in diabetes-related complications, like cognitive decline and depression, this paper will focus specifically on hippocampal neurogenesis rather than neurogenesis in the olfactory bulb.

The process of neurogenesis consists of proliferation of new cells from progenitors, differentiation into astrocytes, oligodendrocytes or neurons, and survival and incorporation of newborn cells into target regions. Newly proliferated cells were typically measured using incorporation of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) or the Ki-67 antigen and results between the two methods have been comparable (Beauquis et al., 2006; Stranahan et al., 2008). Many studies measured rates of differentiation using double-labeling techniques with a protein specific for neurons or glial cells to confirm that the newborn cells possessed a particular phenotype. In the hippocampus, approximately 80% of BrdU-labeled proliferating cells will mature into neurons (Malberg et al., 2000a). However, diabetic models can potentially alter the survival of the multi-potent quiescent progenitor cells or change the proportion of new cells that differentiate into neurons. This paper will review the effect of various diabetes models on the component processes of hippocampal neurogenesis, cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival.

4. Effects of diabetes on hippocampal neurogenesis and behavior

Since T1D and T2D have similar but distinct metabolic differences that could contribute to altered hippocampal neurogenesis and behavior in different ways, animal studies that model each type of diabetes will be discussed separately. First reviewed will be the literature examining the effects of experimental T1D and this will be followed by studies on the effects of experimental T2D. For each category or type of diabetes, the paper will discuss topics in the following order 1) effects of diabetes (either T1D or T2D) on hippocampal neurogenesis, 2) resultant behavioral changes due to altered neurogenesis (if any), and 3) potential treatments that can prevent alterations in either neurogenesis and/or behavior.

5. Experimental models of T1D

5.1. Hippocampal neurogenesis

Over half of the rodent studies reviewed used a T1D model to study the effects of diabetes on the hippocampus (see Table 1). Investigators have studied experimental T1D using rodent models involving either administration of streptozotocin (STZ), a toxin that damages the pancreas, or the non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse model, a genetic model that develops T1D.

5.1.1. STZ-induced diabetes

Most studies used the pharmacological compound, STZ, to induce experimental T1D in rodents. STZ is a glucosamine-nitrosourea compound that destroys the insulin secreting pancreatic beta cells by uptake through the highly expressed glucose transporter (GLUT)-2 and causes toxicity through deoxyribonucleic acid methylation (Lenzen, 2008). Pancreatic cell death causes chronic hypoinsulinemia and subsequent hyperglycemia and increased corticosterone levels develop within 2 weeks of treatment. STZ-induced diabetes consistently decreased hippocampal cell proliferation in both mice (Balu et al., 2009; Beauquis et al., 2006; Revsin et al., 2009; Saravia et al., 2006a; Saravia et al., 2004; Saravia et al., 2006b) and rats (Jackson-Guilford et al., 2000; Kang et al., 2006; Piazza et al., 2011; Stranahan et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009a; Wang et al., 2009b; Zhang et al., 2008a), despite many procedural differences noted across studies. For instance, the dose of STZ used in the reviewed studies varied between 170-200 mg/kg, intraperitoneal (i.p.) for mice and 45-70 mg/kg, i.p. or intravenous for rats. The duration of diabetes also varied from a few days (Jackson-Guilford et al., 2000) to as long as 8 weeks (Wang et al., 2009a). Yet, despite these differences, STZ-induced diabetes consistently decreased hippocampal cell proliferation.

In terms of early neuronal differentiation, the earliest time point that investigators could detect differences between the STZ-induced diabetic group and control group was at seven days post BrdU injection (Beauquis et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2008b). Saravia et al. measured co-localization of BrdU and anti-β-III tubulin two hours post BrdU and found no differences between the STZ and control groups (Saravia et al., 2006a; Saravia et al., 2004). At seven days post BrdU injection, Zhang et al. reported that STZ resulted in a 47% decrease in immature neuronal differentiation (cells double labeled with BrdU and doublecortin) (Zhang et al., 2008b). Also at seven days post initial BrdU injection (animals received BrdU, 65 ug/g body weight, once daily for seven days), Beauquis et al. (Beauquis et al., 2006) found the same result as Zhang et al. (Zhang et al., 2008b) using a different neuronal marker, anti-β-III tubulin. At 10 days post BrdU injection, STZ continued to significantly decrease the number of cells co-staining with BrdU and anti-β-III tubulin (control versus STZ, p < 0.01). In summary, STZ-induced diabetes resulted in lower numbers of immature neurons compared to control groups, detectable as early as seven days post BrdU injection (Beauquis et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2008b).

The proportion of cells that matured into neurons after STZ-induced diabetes in rats either decreased (Wang et al., 2009a; Zhang et al., 2008b) or did not change (Stranahan et al., 2008). Newly proliferated cells in diabetic rats showed a reduced rate of survival, measured by co-labeling of markers for mature neurons calbindin (Zhang et al., 2008b) or NeuN (Wang et al., 2009a) with BrdU at 21 days post injection. However, another group found no difference in neuronal survival despite using the same NeuN marker and time frame (Stranahan et al., 2008).

Some studies also measured the co-localization of BrdU with glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), a marker for astrocytes. The majority of studies reported no effect of STZ-induced diabetes on astrocyte proliferation in the hippocampus (Beauquis et al., 2006; Stranahan et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009a), while other studies reported increased levels of proliferation (Revsin et al., 2009; Saravia et al., 2006a). In summary, STZ-induced diabetes consistently decreased hippocampal cell proliferation and survival, while some investigators found that this T1D model also negatively affected neuronal differentiation.

5.1.2. NOD mouse model of diabetes

NOD mice spontaneously develop T1D by 12-15 weeks of age through autoimmune destruction of the pancreatic beta cells (Giarratana et al., 2007). Unlike humans, the NOD mouse appears susceptible to other types of autoimmune disorders and NOD females develop autoimmune diabetes at higher rates than males. Despite these differences from the human condition, the NOD mouse simulates human T1D better than any other mouse model (Giarratana et al., 2007).

Female NOD mice were studied for hippocampal neurogenesis before and after the development of diabetes and in comparison to nondiabetic C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice as control strains (Beauquis et al., 2008). At time points before diabetes (5 and 8 weeks of age) and after development of diabetes (12 weeks of age), NOD mice showed decreased hippocampal cell proliferation compared to the C57BL/6 and BALB/c control strains. The survival of cells was measured when labeled with BrdU injection at 12 weeks of age and harvested 3 weeks later. Non-diabetic and diabetic NOD mice showed significantly lower levels of cell survival than the C57BL/6 control strain. Further, the NOD mice that did not become diabetic had higher levels of neuronal survival than NOD mice that became diabetic by 15 weeks of age, but the proportion of cells that became neurons did not differ between the non-diabetic and diabetic NOD mouse groups (Beauquis et al., 2008). This suggests that the NOD mouse has a pre-existing disposition towards decreased hippocampal neurogenesis long before conversion into a diabetic state and mice that eventually manifest diabetes will experience even greater reductions of neurogenesis. Even though the NOD female mouse has elevated levels of estrogen in the blood (Gowri et al., 2007), and estrogen increases hippocampal neurogenesis (Saravia et al., 2006a; Saravia et al., 2004), the NOD female mice continues to show decreased hippocampal neurogenesis at all stages, pre-diabetes and diabetes. Regardless of the model, experimental T1D, thus far, consistently decreases both hippocampal cell proliferation and survival.

5.2. Behavior changes associated with decreased neurogenesis in diabetic models

To further elucidate the functional significance of hippocampal neurogenesis, some studies also examined the consequences of decreased hippocampal neurogenesis in STZ-induced diabetic mice using behavioral tests for cognition or depressive behavior. Please refer to Table 2 for a brief summary of all behavioral tests used in the studies reviewed in this paper.

Table 2. Behavioral Tests Used to Study the Effects of Diabetes on Behavior.

| Test | Assessment | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conditioned Active Avoidance Test | Associative Learning and Memory | Rodents learn that a particular cue signals them to relocate to a different compartment of the cage in order to avoid negative reinforcement (shock). Measures the number of avoidance trials and latency to escape. | Increase in the number of avoidance trials and decreased latency to escape indicates successful learning (Alvarez et al., 2009). |

| Forced Swim Test | Vulnerability to Stress-Induced Depression/Antidepressant Efficacy | Rodents are placed in a cylinder of water. Initially rodents attempt to escape with climbing or explore with swimming behaviors, but then develop immobility. Measures the duration of immobility or active behaviors. | Increased immobility (decreased struggling) suggests increased display of passive stress coping and vulnerability to stress-induced depression-like behavior. Antidepressant medications consistently decrease immobility (Cryan et al., 2005). |

| Morris Water Maze | Spatial Learning and Memory | Rodents are placed in a large pool of water and learn the location of a hidden platform. Measures the latency to find the platform and the length of path taken to find the platform. | Spatial learning is measured by the decreased latency to find the hidden platform and the decreased length of the path taken to find the platform over trials (Sharma et al., 2010b). |

| Novel Object-Placement Recognition Task | Spatial Memory | Rodents are allowed to explore two objects. After a delay, rodents are given a second opportunity to explore the objects but one object is moved to a different location. The time spent sniffing the relocated object is the primary measure. | When a rodent spends more time sniffing the relocated object (usually calculated as a percent), it suggests the rodent remembers or knows the object was moved (Revsin et al., 2009). |

| Novel Object Recognition/Preference Test | Recognition Memory | Rodents are allowed to explore two objects. After a delay, rodents are given a second opportunity to explore the objects but one object is replaced with a novel object. The time spent sniffing the novel object is the primary measure. | When a rodent spends more time sniffing the novel object (usually calculated as a percent), it suggests the rodent remembers the previously presented object (Gandal et al., 2008). |

| Sucrose Preference/Consumption Test | Affective State | This test makes use of the natural preference that rodents have for sweet foods. Typically after food and water deprivation, experimenter presents water and a sucrose solution for animals to drink. Document amounts of solutions consumed. | Decreased consumption of the sucrose solution suggests the solution is not as rewarding or pleasurable. This change represents increased anhedonic behavior (Wang et al., 2009a). |

| Y-Maze | Memory | This test uses rodents' natural preference to explore new places. There are three arms to the maze and rodents are allowed to explore the maze freely. Arm entries are recorded. | Rodents ordinarily prefer to alternate between the three arms. A rodent with impaired memory will re-enter an arm that it just explored (Iwai et al., 2009). |

5.2.1. Behavioral tests of cognition

Several studies have suggested that decreased hippocampal neurogenesis after STZ-induced diabetes is accompanied by deficits in behavioral tasks involving spatial learning and memory, such as performance in the Morris water maze and novel object recognition (Piazza et al., 2011; Revsin et al., 2009; Stranahan et al., 2008). As these cognitive tasks are mediated by the hippocampus, they were expected to be the most easily disrupted behaviors by decreased hippocampal neurogenesis.

Significant deficits of learning in the Morris Water Maze were reported in diabetic rats (Stranahan et al., 2008). Furthermore, diabetic rats showed learning deficits only in the hippocampal dependent version of the Morris water maze test. In a non-hippocampal dependent version of the maze, using a visible instead of submerged platform, diabetic rats displayed similar escape latencies as controls. In the novel object recognition test, diabetic rats spent less time exploring the novel object, supporting a deficit of memory processing (Stranahan et al., 2008).

Decreased hippocampal cell proliferation in diabetic mice also resulted in cognitive deficits in the novel object-placement recognition task (Revsin et al., 2009). Although the novel object-placement recognition task and Morris water maze both assess spatial memory, mice did not show deficits in the Morris water maze within the same time frame of when mice began to show deficits in the novel object-placement recognition task (Revsin et al., 2009). These conflicting data were reconciled by the explanation that the novel object-placement recognition test can detect mild cognitive disturbances while deficits in the Morris water maze might require more severe hippocampal dysfunction (Dere et al., 2005; Li et al., 2004; Revsin et al., 2009).

Although not a task involving the hippocampus exclusively, mice were also tested for associative learning and memory in a conditioned active avoidance test. This test measures whether a mouse can learn that a particular cue signals for them to relocate to a different compartment in order to avoid negative stimuli (Alvarez et al., 2009). Twenty days after diabetes induction and subsequent decrease in neurogenesis, STZ-diabetic mice showed learning and memory deficits in the conditioned active avoidance test when compared to control mice (Alvarez et al., 2009). Taken together, it appears that decreased neurogenesis in T1D rodents may contribute to impaired learning and memory based on the results from a number of cognitive tests.

5.2.2. Behavioral tests associated with depression

Since not all diabetic patients develop depression, it would be important to identify pathogenic mechanisms responsible for triggering depression in diabetic patients. In order to develop a rodent model of predisposition to depression, daily sucrose intake was evaluated in a large group of rats as a measure of anhedonia, and groups were divided into low and high levels of anhedonia prior to the induction of diabetes by STZ (Wang et al., 2009a). Anhedonia, a core symptom of depression in humans, refers to the inability to experience pleasure (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) and reduced preference and/or consumption of sucrose is frequently used to measure anhedonia in rodents (Lucki, 2010; Pollak et al., 2010). After induction of diabetes, the investigators were able to confirm that variations in sucrose intake predicted depressive behavior measured by increased immobility in the rat forced swim test. They found that diabetes with and without depressive behavior led to additional physiological differences in hippocampal neurogenesis (Wang et al., 2009a). STZ reduced hippocampal cell proliferation by 56% in rats with diabetes plus depressive behavior versus 27% in rats with diabetes without depressive behavior. Neuronal differentiation was also reduced more in rats with diabetes plus depressive behavior, by 38% versus 21%, respectively. Finally, cell survival was reduced more in rats with diabetes plus depressive behavior by 44 versus 15%, respectively. This may indicate that depressive behavior only manifests when hippocampal neurogenesis levels fall below a certain threshold. Hence, diabetes may increase vulnerability to depressive symptoms by lowering hippocampal neurogenesis, but only a certain portion of the group will have hippocampal neurogenesis levels below a certain threshold; and it is this subgroup that will develop symptoms of depressive behavior. A model like this may explain why not everyone who has diabetes develops depression, even though depression is more prevalent in the diabetic population (Adili et al., 2006; Astle, 2007; Hood et al., 2006; Iosifescu, 2007; Musselman et al., 2003).

Another study examined whether restoration of glycemic control with insulin treatment was able to reverse the changes in hippocampal neurogenesis and affective behavior induced by STZ-induced diabetes in C57BL/6 mice (Ho et al., 2011). STZ-induced diabetes caused depressive-like behavior by increasing immobility in the tail suspension test, decreased the efficacy of rewarding intracranial self-stimulation, decreased hippocampal cell proliferation and increased corticosterone levels. Insulin treatment, given 1-4 weeks after diabetes, reduced hyperglycemia, reduced immobility in the tail suspension test, reversed the reduced thresholds of self-stimulation behavior, and returned hippocampal cell proliferation and corticosterone to levels comparable to the control group. In contrast, reductions of locomotor activity and BDNF levels in the frontal cortex were not reversed by insulin treatment. Thus, this study showed that some phenotypes related to depressive behavior can be potentially reversed by insulin therapy initiated shortly after the induction of diabetes (Ho et al., 2011). In contrast, insulin treatment was unable to restore deficits in water maze learning and hippocampal LTP in rats when initiated 10 weeks after STZ induction (Biessels et al., 1998). Since diabetes may be incompletely controlled in different patients, whether insulin treatment would reverse the effects on depressive or cognitive behaviors after exposure to long periods of untreated diabetes is a practical concern.

5.3. Treatments that prevent deficits in neurogenesis and behavior in T1D and possible contributing mechanisms

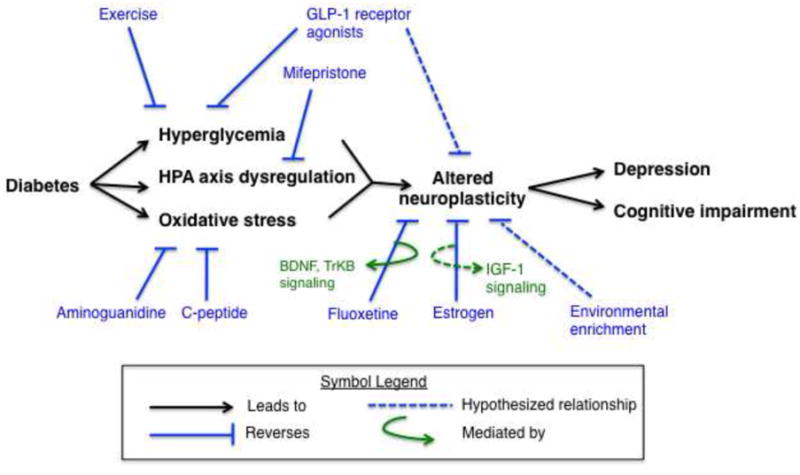

Potential pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies for diabetic complications may be identified or evaluated by studying the reversal of decreased hippocampal neuroplasticity and pathology in rodent models of diabetes. These models could also examine the physiological mechanisms through which these therapies work. This next section will discuss potential therapeutic targets and possible mechanisms contributing to altered hippocampal neurogenesis and behavior in STZ-induced diabetic rodents. These mechanisms are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Caption The diabetic milieu showing pathological mechanisms contributing to neurobehavioral complications and examples of pathways that have been examined as therapeutic approaches. Diabetes leads to hyperglycemia, HPA axis dysregulation, and increased oxidative stress causing altered neuroplasticity in the brain resulting in symptoms such as depression and cognitive impairment. Various pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions targeted at different pathological processes are depicted in the figure and discussed in the text. For instance, targeting the primary pathological mechanisms such as improved glycemic control (insulin, GLP-1 agonists), reversal of HPA axis dysregulation (mifepristone or ADX with CORT replacement), or oxidative stress can improve brain structure and function (neuroplasticity) and lead to improved behaviors (mood and cognition). GLP-1 agonists may improve behavior by combining two mechanisms, directly facilitating glycemic control and improving neuroplasticity. Fluoxetine is thought to produce antidepressant effects and counteract the impairing effects of stress on neuroplasticity through BDNF and TrKB signaling. Hypothesized relationships are described with a dotted line, while solid lines support relationships that have been demonstrated by scientific evidence.

5.3.1. Fluoxetine

Few studies have evaluated the effects of antidepressant treatments on neuroplasticity-related alterations in the hippocampus after STZ-induced diabetes, especially since antidepressants can produce a modest increase of neurogenesis in rats without diabetes (Malberg et al., 2000b). C57BL/6 mice given the serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine (10 mg/kg for 10 days) prevented the loss of neurogenesis in STZ-induced diabetic mice (Beauquis et al., 2006). The diabetic mice demonstrated a 30% reduction of cell proliferation, but showed a complete reversal of this deficit after fluoxetine whereas fluoxetine did not alter neurogenesis in the control animals (Beauquis et al., 2006). In addition, chronic fluoxetine preferentially reversed the loss of cells with a neuronal phenotype. Most of the literature indicated that antidepressants increase hippocampal neurogenesis through mediation of BDNF and its receptor TrkB (Castren and Rantamaki, 2010; Pinnock et al., 2010). However, these pharmacological effects of antidepressants were measured in normal animals. The effects of fluoxetine may differ in diabetic rats because increased circulating corticosterone and exogenously administered glucocorticoids potentiate the ability of fluoxetine to increase hippocampal neurogenesis (Bilsland et al., 2006; Huang and Herbert, 2006). Increased corticosterone secretion is a clinical feature of both diabetes and depression (Champaneri et al., 2010). Although consistent with the general view that chronic antidepressant treatments increase hippocampal neurogenesis, it is unclear whether the effects of antidepressants on hippocampal neurogenesis in diabetic animals involve the same pharmacological mechanisms as normal animals. Nevertheless, distinguishing the mechanisms would be important for understanding the use of antidepressant therapies in T1D.

5.3.2. Estrogen

Treatments not necessarily targeted at managing hyperglycemia can prevent deficits in hippocampal neurogenesis and behavior caused by STZ-induced diabetes. Ten days of estrogen treatment, initiated 10 days after STZ injection, brought hippocampal cell proliferation back to control levels (Saravia et al., 2004; Saravia et al., 2006b). Estrogen exerted effects on the hippocampus without affecting systemic glucose values. Hence, glucose regulation was not responsible for the therapeutic effects of estrogen on hippocampal neurogenesis. As an alternative mechanism, it was proposed that activation of estrogen receptors on stem cells in the dentate gyrus activated insulin-like growth factor-1 signaling to promote neurogenesis (Garcia-Segura et al., 2010), but insulin-like growth factor-1 was not measured in these studies (Saravia et al., 2004; Saravia et al., 2006b). Estrogen has not been evaluated for the cognitive or depressive outcomes of diabetes in humans.

5.3.3. Adrenalectomy/CORT replacement and mifepristone

The HPA axis regulates the secretion of adrenal steroids, corticosterone (CORT) in animals and cortisol in humans. Stranahan and colleagues showed that maintenance of normal CORT levels, with low-dose CORT replacement after adrenalectomy, prevented altered hippocampal neurogenesis and cognitive impairments in STZ-induced diabetic rats (Stranahan et al., 2008). A more recent study showed that it is not merely the presence of CORT, but the ability for CORT to act on glucocorticoid receptors, that drives hippocampal brain changes in STZ-induced diabetic rodents (Revsin et al., 2009). Treatment of diabetic mice with mifepristone, a glucocorticoid receptor antagonist as well as a progesterone receptor antagonist, produced similar results as adrenalectomy with low-dose CORT replacement in rats. Just four days of mifepristone treatment in diabetic mice prevented hippocampal cell proliferation changes and prevented cognitive deficits in a hippocampal dependent task. Since mifepristone blocks receptor activity, it did not affect systemic CORT levels. Thus, even with high circulating CORT levels, mifepristone still prevented hippocampal dysfunction suggesting that glucocorticoid receptor activation rather than the presence of CORT contributed to structural and functional hippocampal changes.

5.3.4. Aminoguanidine

The rate of cell proliferation ordinarily decreases in adults with increasing age (Lazarov et al., 2010). Several studies have proposed that acceleration of the normal brain aging process in diabetes could explain the observed decreases in hippocampal neurogenesis. For example, decreased hippocampal neurogenesis in STZ-induced diabetic rats coincided with elevated serum levels of advanced glycation end products. Four weeks of aminoguanidine treatment, an advanced glycation end product formation inhibitor, lowered serum advanced glycation end product levels and prevented diabetes-related alterations in hippocampal cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival (Wang et al., 2009a). In addition, STZ-induced diabetic rodents also had increased lipofuscin deposits (Alvarez et al., 2009), a morphological structural entity accumulating in the aging brain due to increased lipid peroxidation (Baquer et al., 2009). An increase in these deposits signifies the presence of oxidative stress, abnormal protein turnover, and accelerated aging (Alvarez et al., 2009; Saravia et al., 2007). Together, data from these studies show that accelerated brain aging in diabetes may be partly responsible for decreased hippocampal neurogenesis in diabetic rodents.

5.3.5. Environmental enrichment

Environmental enrichment (EE) has been shown to increase hippocampal neurogenesis and can prevent the reduction of neurogenesis and diminished indication of structure and function induced by experimental diabetes in mice and rats (Beauquis et al., 2010b; Piazza et al., 2011).

Exposure to EE for 10 days, studied by housing groups of mice in a larger cage with toys, extra nesting, plastic houses, and tubes, increased hippocampal cell proliferation and cell survival in mice made diabetic by STZ (Beauquis et al., 2010b). Further, EE increased the complexity of dendritic branching of new neuronal cells and strengthened the surrounding hippocampal vascular network in diabetic mice (Beauquis et al., 2010b). However, exposure to EE also reduced glucose levels in the diabetic group, although glucose values did not return completely to control levels (Beauquis et al., 2010b). A less severe form of diabetes experienced by the diabetic EE group could also explain prevention of cellular brain changes and behavior.

The effects of EE on hippocampal cell proliferation and cognition was studied in STZ-induced diabetic rats assigned to housing 40 days prior to the induction of diabetes and then maintained for the duration of the study (Piazza et al., 2011). Rats housed under EE conditions lived in groups of eight in a larger cage with multiple floors containing toys, balls, tunnels, and running wheels, while rats in standard housing had a smaller cage with standard bedding and lived in groups of two. STZ-induced diabetes impaired cognition, measured with the novel object-placement recognition test, and EE ameliorated the cognitive deficits. Diabetes lowered cell proliferation but EE did not return cell proliferation back to control levels (Piazza et al., 2011). Exact glucose measurements after EE were not reported, though, so it is unclear if EE significantly lowered glucose levels in the STZ-EE group. Nevertheless, Piazza et al. (2011) showed that EE could restore a measure of cognitive function impaired by diabetes, independent of modifying hippocampal cell proliferation.

5.4. Summary of findings

Numerous studies (Table 1) have shown that experimental T1D consistently decreases both hippocampal cell proliferation (Balu et al., 2009; Beauquis et al., 2006; Beauquis et al., 2008; Jackson-Guilford et al., 2000; Kang et al., 2006; Piazza et al., 2011; Revsin et al., 2009; Saravia et al., 2006a; Saravia et al., 2004; Stranahan et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009a; Wang et al., 2009b; Zhang et al., 2008a) and survival (Beauquis et al., 2008; Stranahan et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009a; Zhang et al., 2008b) regardless of the particular model. Some investigators also found that STZ-induced diabetes negatively affects the proportion of cells that differentiate into neurons (Beauquis et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2008b). Decreased neurogenesis in T1D rodents may contribute to impaired learning and memory (Piazza et al., 2011; Revsin et al., 2009; Stranahan et al., 2008). However, amelioration of cognitive deficits may not always require restoration of neurogenesis to control levels (Piazza et al., 2011). Further, rats with suggestive evidence of anhedonia had lower levels of neurogenesis and increased expression of depressive-like behavior after developing diabetes (Wang et al., 2009a). This suggests that some behavioral characteristics prior to developing diabetes could predict which rodents were likely to develop depressive behaviors after becoming diabetic.

A number of pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies not necessarily targeted at managing hyperglycemia can reverse the detrimental effects of T1D on hippocampal pathology (see Figure 1). The diabetic brain exhibits evidence of accelerated aging (Alvarez et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2009a) and HPA axis dysregulation are factors that contribute to hippocampal pathology in T1D-like rodents (Revsin et al., 2009; Stranahan et al., 2008). Treatment with fluoxetine (Beauquis et al., 2006), estrogen (Saravia et al., 2006a; Saravia et al., 2004), mifepristone (Revsin et al., 2009), aminoguanidine (Wang et al., 2009a), and EE (Beauquis et al., 2010b; Piazza et al., 2011) all showed promising effects against diabetic brain complications. These studies have provided some insight on different physiological mechanisms that could alter deficits of neurogenesis in diabetes.

6. Experimental models of T2D

6.1. Hippocampal neurogenesis

Hippocampal neurogenesis has been studied in a number of animal models of T2D (see Table 1). These models include genetic models in mice and rats, the db/db mouse, Zucker diabetic rat, and the Goto-Kakizaki rat. An environmental model of T2D that has been used commonly with rodents is prolonged exposure to a high fat diet or diet-induced obesity.

6.1.1. Zucker Diabetic rat and db/db mouse

A leptin receptor mutation, on chromosome five, in the Zucker rat (fa/fa) eventually led to the discovery of the Zucker diabetic rat. A similar spontaneous mutation was also noted in db/db mice, a splice mutation on chromosome four, which is the region of conserved synteny with chromosome 5 of rats (Sone and Osamura, 2001). Both the Zucker diabetic rat and db/db mouse express metabolic symptoms similar to those seen in humans with T2D. Without the appetite suppressing effects of leptin, these animals exhibit obesity with glucose intolerance, hyperinsulinemia, and hyperlipidemia. These animals also display the three classic symptoms of diabetes: polyphagia, polydipsia, and polyuria. Furthermore, the syndrome develops in a manner similar to human T2D. Early in development, the animals have insulin resistance with euglycemia. Overt hyperglycemia tends to manifest between 7-12 weeks of age in Zucker diabetic rats (Leonard et al., 2005) and between 4-8 weeks of age in db/db mice (Allen et al., 2004). Rats and mice heterozygous for the leptin receptor mutation, on the other hand, do not develop symptoms of diabetes.

Zucker diabetic rats have decreased hippocampal cell proliferation and lower levels of neuronal differentiation compared to their lean, non-diabetic counterparts (Yi et al., 2009). In the mouse equivalent model, db/db mice demonstrated decreased hippocampal cell proliferation in diabetic mice compared to the control group (Stranahan et al., 2008). When BrdU was administered three weeks prior to tissue collection, db/db mice also showed reduced survival rate for the newborn hippocampal cells but the proportion of cells that differentiated into neurons did not differ from the control group. In contrast, another research group showed increased cell proliferation in db/db mice compared to lean counterparts (Hamilton et al., 2011). The reason for these different reports has not been reconciled.

6.1.2. Goto-Kakizaki rat

In contrast to the Zucker Diabetic rat, the Goto-Kakizaki rat is not obese. The Goto-Kakizaki T2D-like model was generated from selective inbreeding of multiple generations of Wistar-Kyoto rats with glucose tolerance at the upper limit of the normal distribution so that diabetes became a stable trait (Portha, 2005). Goto-Kakizaki rats have decreased pancreatic beta cell number and beta cell dysfunction, which results in hyperglycemia beginning at 1-4 months of age. Similar to humans with T2D, these rats show insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and hypercholesterolemia but do not express overt obesity (Beauquis et al., 2010a). Coincidentally, Wistar-Kyoto rats are also used as a genetic model of depression and exaggerated stress responses (Crowley and Lucki, 2005; Rittenhouse et al., 2002).

In the pre-diabetes stage, Goto-Kakizaki rats showed normal levels of hippocampal cell proliferation and neuronal differentiation compared to the control group (Lang et al., 2009). Unlike most of the other diabetes models, adult Goto-Kakizaki rats showed increased hippocampal cell proliferation and an increased number of immature neurons (Beauquis et al., 2010a). Survival of newly proliferated hippocampal cells in the Goto-Kakizaki rat was either decreased (Lang et al., 2009) or unchanged from Wistar controls (Beauquis et al., 2010a). It is unclear what factors accounted for the different rates of cell survival because both studies used similarly aged rats and methods to measure hippocampal cell survival, except for their BrdU dosing regimen. Behavioral studies have not been done with the Goto-Kakizaki rat.

The increased cell proliferation and either decreased or unchanged cell survival in the Goto-Kakizaki rat has been interpreted as a pattern of compensation for the increased neuronal cell death accompanying diabetes. In the Beauquis et al. study (Beauquis et al., 2010a), diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats may have compensated successfully and showed cell survival rates similar to Wistar controls. In the Lang et al. study (Lang et al., 2009), on the other hand, diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats may not have compensated completely for losses in hippocampal cell survival despite the increase in cell proliferation.

6.1.3. High fat diet

Exposure of rodents to a high fat diet produces obesity and physiological signs of T2D-like diabetes, including increased insulin and corticosterone secretion, and causes measurable deficits in cognitive performance. Male rats showing a slight but significant weight gain after exposure to a high fat diet for 4 weeks demonstrated fewer cells in the hippocampus surviving 2 weeks after BrdU labeling possibly due to increased serum corticosterone levels (Lindqvist et al., 2006). In contrast, female rats exposed to the diet showed no changes in weight gain, corticosterone levels or cell proliferation. Male mice fed a high fat diet for 7 weeks showed increased body weight gain and serum cholesterol levels and reduced proliferation of neuroprogenitor cells in the hippocampus without altering neuronal differentiation (Park et al., 2010). A reduction of BDNF levels in the hippocampus by the high fat diet was suggested to explain the reduction of neurogenesis. The effects of exposure to a high fat diet on neurogenesis were also shown to vary in different strains of mice (Hwang et al., 2008). C57BL/6 mice showed a reduction of neurogenesis at both 4 and 12 weeks, as measured by Ki67 or doublecortin immunoreactivity, whereas C3H/He mice showed reduced neurogenesis only at 4 weeks.

Other groups have found more equivocal results on hippocampal neurogenesis from exposure to a high fat diet. The effects of exposure to a high fat diet for a total of 17 weeks were compared between juvenile (3 weeks old) and adult (12 weeks old) C57BL/6 mice (Boitard et al., 2012). The high fat diet increased body weight and plasma levels of leptin, insulin, corticosterone, and cholesterol in both age groups. However, the high fat diet reduced hippocampal neurogenesis (cells labeled with doublecortin) only in mice given the diet as juveniles but not as adults. Another study induced obesity in rats by exposure to a high fat diet for 12 weeks (Rivera et al., 2011). Although calorie intake and body weight were higher with the high fat diet, serum cholesterol, insulin and leptin were unchanged and hippocampal cell proliferation was unaffected by the high fat diet. Male Swiss TO mice placed on a high fat diet for 5 months showed increased body weight gain, hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia (Hamilton et al., 2011). Exposure to the high fat diet increased hippocampal cell proliferation compared to lean controls as measured by BrdU incorporation; however, the high fat diet reduced the number of immature cells as measured by doublecortin. Thus, although a number of studies have shown that exposure to a high fat diet can reduce hippocampal cell proliferation, a number of variables, including the age of exposure, duration of treatment, genetic strain, relative weight gain, magnitude of diabetic parameters and method of measuring neuroplasticity, can moderate these effects.

6.2. Behavior changes associated with decreased neurogenesis in diabetes

The db/db mice may be useful for examining the comorbidity between diabetes and cognition and depression because they have been reported to show both cognitive impairments and increased depressive behavior. Spatial memory in the Morris water maze was impaired in db/db mice along with decreased hippocampal neurogenesis (Stranahan et al., 2008). The db/db mice did not explore novel objects in the novel object preference test as much as controls but spent more time exploring objects in general, a pattern that may be consistent with impaired recognition memory. Also, db/db mice showed other behavioral changes, increased immobility in the forced swim test, reduced locomotor activity and increased exploration of the open arms of the elevated zero maze, when tested as juveniles or adults but working memory deficits in the y-maze and disrupted prepulse inhibition only when tested as adults (Sharma et al., 2010).

Mice exposed to a high fat diet as juvenile showed significantly impaired spatial learning and memory in a radial arm maze (Boitard et al., 2012). This pattern agreed in part with reduced hippocampal cell proliferation measured after juvenile exposure to the high fat diet. However, the mice experienced a change in housing and food-deprivation conditions in order to conduct the behavioral testing and these procedures may also have impacted the effects of high fat diet exposure in the older animals.

6.3. Treatments that prevent deficits in neurogenesis and behavior

Several investigators have explored the effects of possible treatments for diabetes on hippocampal neurogenesis in T2D-like models. These treatments provide further insight into the diabetic mileu contributing to neurobehavioral complications (see Figure 1). The long-term effects of exercise (Yi et al., 2009), the benefits of controlling HPA activity (Stranahan et al., 2008) and the value of glycogen-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists on glycemic control and behavior (Hamilton et al., 2011) have been demonstrated in animal models.

6.3.1. Exercise

In a study on the effects of exercise, Zucker Diabetic rats showed significantly increased hyperglycemia and decreased neurogenesis compared to the non-diabetic Zucker Lean Control rats. Exercising five days a week over a five-week period significantly increased hippocampal neurogenesis in both Zucker Diabetic and Zucker Lean Control rats, but the increase was not as robust in the Zucker Diabetic group (Yi et al., 2009). Nevertheless, exercised Zucker Diabetic rats showed a non-diabetic metabolic profile with glucose levels and body weight similar to the Zucker Lean Control group. It appears that for Zucker Diabetic rats, exercise completely prevented hippocampal brain pathology by ameliorating diabetes. Other benefits of exercise besides improved glycemic control could have contributed to increased neurogenesis, such as lowering blood pressure, improving brain perfusion, and increasing growth factors like BDNF, insulin-like growth factor-1, and vascular endothelial growth factor (van Praag, 2008; Yi et al., 2009), but these were not measured in this interesting model.

6.3.2. Adrenalectomy/CORT replacement

Stranahan et al. (Stranahan et al., 2008) demonstrated the role of HPA activity and CORT in mediating the effects of diabetes on hippocampal neurogenesis and cognition in db/db mice. Maintenance of normal levels of CORT in db/db mice prevented learning deficits and restored hippocampal cell proliferation back to control levels. Further, administration of high-dose CORT replacement in adrenalectomized db/db mice reestablished learning and memory deficits. These results clearly demonstrate the involvement of CORT and glucocorticoid receptor activation in mediating these cognitive complications in diabetic rats. It also suggests that decreased hippocampal neurogenesis can lead to cognitive deficits while prevention of altered hippocampal neurogenesis can prevent cognitive decline.

6.3.3. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists

Several GLP-1 receptor agonists, such as extendin-4 and liraglutide, have been developed recently to more effectively manage glucose regulation in T2D. These GLP-1 analogs were examined for the ability to regulate hippocampal neurogenesis and behavior in rodent models of diabetes. Treatment of ob/ob mice for 6 weeks and db/db mice for 10 weeks with extendin-4 or liraglutide produced an increase in hippocampal cell proliferation compared to vehicle-treated controls (Hamilton et al., 2011). Administration of the GLP-1 analogs to Swiss mice, fed a high fat diet for 5 months to cause significant body weight gain, hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia, also showed increased cell proliferation in the hippocampus (Hamilton et al., 2011). In separate studies, chronic administration of extendin-4 and liraglutide restored compromised performance in the novel object recognition test, rescued hippocampal LTP and improved glycemic control in Swiss mice exposed to a high-fat diet for 28 days (Gault et al., 2010; Porter et al., 2010).

GLP-1 is a hormone secreted primarily by L-cells from the distal intestine and neurons in the nucleus tractus solitaries (NTS) of the caudal brainstem. Both peripheral and central GLP-1 systems modulate plasma glucose concentrations by stimulating insulin secretion and promoting beta cell proliferation (Drucker and Nauck, 2006; Hayes, 2012). While GLP-1 is produced in the NTS, its receptor is distributed throughout the brain, including the hippocampus (Drucker and Nauck, 2006). GLP-1 analogs have been reported to produce neuroprotective effects, enhance cell survival, reduce apoptosis, and increase hippocampal neurogenesis when given to nondiabetic mice. It is possible that GLP-1 analogs may independently improve neuroplasticity in diabetes by neurotrophic or neuroprotective effects exerted directly in the brain. This intriguing possibility underlies the importance of determining the mechanism of action of GLP-1 analogs on hippocampal neuroplasticity and behavior in diabetic animals.

6.4. Summary of findings

Both genetic and environmental approaches have been used to study the effects of T2D-like animal models on hippocampal neurogenesis and behavior. The Zucker Diabetic rat (Yi et al., 2009) and the db/db mouse (Stranahan et al., 2008) models led to decreased hippocampal cell proliferation and survival. In contrast, diabetes in the Goto-Kakizaki rat increased hippocampal cell proliferation and neuronal differentiation (Beauquis et al., 2010a) and did not change (Beauquis et al., 2010a) or decreased (Lang et al., 2009) cell survival. The observed increase in hippocampal cell proliferation and neuronal differentiation may have been an attempt to compensate for neurons that did not survive. It is interesting that the Goto-Kakizaki rat displayed elevated cell proliferation despite significant increases in CORT (Beauquis et al., 2010a). This rat model for T2D demonstrated that interpreting changes of hippocampal cellular plasticity in a diabetic milieu can be quite complex.

The effects of feeding rodents a high fat diet are of special importance because this may simulate the etiology of diabetes for many individuals. Exposure to a high fat diet produced the most variable effects on measures of hippocampal neuroplasticity between studies, although reductions of hippocampus and cognitive behavior were reported. The variability may be due to differences in genetic strain, age of exposure, treatment duration, degree of obesity and magnitude of diabetic parameters obtained between studies.

The existence of several rodent models of T2D should encourage examination of the effects of current and prospective treatments for diabetes on hippocampal neurogenesis and behavior. The long-term effects of exercise (Yi et al., 2009), the benefits of controlling HPA activity (Stranahan et al., 2008) and the value of GLP-1 analogs (Hamilton et al., 2011) on reversing the deficits of neurogenesis and behavior in diabetes and restoring glycemic control have been demonstrated in animal models. Although several promising demonstrations have been produced for these treatments, studies in the field have not yet distinguished the challenging mechanisms underlying their effects. In addition, the effects of some treatments for diabetes and depression (antidepressants) have not yet been studied in rodent models for T2D. Recommendations for future studies are provided in a subsequent section.

7. Experimental diabetes and other forms of hippocampal neuroplasticity

Neuroplasticity refers to the ability of the brain to adapt, change and reorganize throughout life. Hippocampal neurogenesis represents only one form of hippocampal neuroplasticity affected by diabetes. Other forms of hippocampal neuroplasticity include changes in hippocampal dendritic branching, long-term potentiation, and apoptosis. Their relevance to rodent models of diabetes will be discussed in the next section.

7.1. Contraction of hippocampal dendrites and loss of spines

Neurons connect to other neurons within the brain through a rich network of dendritic projections. Dendrites make up about 95% of a neuron's total volume (Malone et al., 2008) and decreased dendritic branching likely contributes to the overall decrease in hippocampal volume (Czeh and Lucassen, 2007) frequently observed in diabetic and depressed patients (McIntyre et al., 2010). Dendrites receive electrical input from upstream neurons and structural changes in dendrites could alter the way in which the neuron process afferent signals.

Studies of both T1D and T2D models in rodents have consistently shown decreased dendritic branching and density of spines (see Table 3). Several treatments successfully reversed pathological changes in hippocampal dendrites. Implantation of pig islet cells, which released insulin, ameliorated severe hyperglycemia and reversed the detrimental effects of diabetes on dendritic remodeling (Magarinos et al., 2001). Other treatments, like wheel running, caloric restriction (Stranahan et al., 2009), and environmental enrichment (Beauquis et al., 2010b), also improved spine density. Only a few diabetes studies attempted to identify the mechanisms responsible for these changes. Similar to decreased hippocampal neurogenesis, hippocampal dendritic alterations were associated with decreased BDNF levels (Stranahan et al., 2008), while elevating BDNF levels through exercise and/or caloric restriction improved dendritic spine density (Stranahan et al., 2009). Remodeling of dendrites was associated with impaired learning and memory in the Morris water maze (Malone et al., 2008; Stranahan et al., 2008). However, these studies did not include a treatment component in the experimental design, so it is unknown whether or not treatments that successfully reverse dendritic remodeling could also improve cognitive function.

Table 3. Effects of Diabetes on Hippocampal Dendritic Branching/Density/Complexity.

| Model | Species | Effect on Dendritic Branching | Associated Behavior | Treatments that Reversed Changes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STZ | Mice | Decreased | Environmental Enrichment | Beauquis et al. (2010) | |

| STZ | Rat | Decreased | Impaired Cognition | Malone et al. (2008) | |

| STZ | Rats | Decreased | Magarinos et al. (2000) | ||

| STZ | Rats | Decreased | Porcine Islets | Magarinos et al. (2001) | |

| STZ | Rats | Decreased | Martinez-Tellez et al. (2005) | ||

| High Fat | Rat | Decreased | Impaired Cognition | Stranahan et al. (2008) | |

| db/db | Mouse | Decreased | WR and/or CR | Stranahan et al. (2009) |

Abbreviations: STZ, streptozotocin; WR, wheel running; CR, caloric restriction

7.2. Long-term potentiation and depression

The electrophysiological properties of hippocampal neurons, including membrane potential, membrane input resistance, and membrane time constant, remain unaffected in diabetes (Artola et al., 2002; Gardoni et al., 2002; Liang et al., 2006; Trudeau et al., 2004). The effect of diabetes on basal synaptic transmission remains inconclusive. However, investigators consistently report that diabetes, especially for T1D and most T2D models in rodents, impaired long-term potentiation (LTP) of hippocampal CA1 neurons (see Table 4). LTP is a major cellular mechanism that underlies learning and memory and is a measure of the synapse strength between connecting neurons.

Table 4. Effects of Diabetes on Hippocampal Long-Term Potentiation.

| Model | Species | Effect on LTP | Effect on LTD | Associated Behavior | Treatments that Reversed Changes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STZ | Rat | Decreased | Nimodipine (PR) | Biessels et al. (2005) | ||

| STZ | Rat (j) | No Change | Decreased | Imp. Cog. | GLP-1 Amide | Iwai et al. (2009) |

| STZ | Rat | Decreased | Insulin | Izumi et al. (2003) | ||

| STZ | Rat (f) | Decreased | Imp. Cog. | Electroacupuncture | Jing et al. (2008) | |

| STZ | Rat | Decreased | Increased | Imp. Cog. | Kamal et al. (2000) | |

| STZ | Rat | Decreased | Kamal et al. (2005) | |||

| STZ | Rat | Decreased | Imp. Cog. | Enalapril (PR) | Manschot et al. (2002) | |

| STZ | Rat | Decreased (DG) | None | Aldosterone | Stranahan et al. (2010) | |

| High Fat | Mice | Decreased | Imp. Cog. | Exendin 4 | Gault et al. (2010) | |

| High Fat | Rat | Decreased | Imp. Cog. | Stranahan et al. (2008) | ||

| High Fat | Mice | Decreased | Imp. Cog. | (d-Ala2)GIP | Porter et al. (2011) | |

| ZD | Rat | Decreased, No Change (DG) | Alzoubi et al. (2005) | |||

| ZD | Rat | No Change | No Imp. Cog | Belanger et al. (2004) |

Abbreviations: f, females; j, juvenile; STZ, streptozotocin; ZD, Zucker Diabetic; LTP, long-term potentiation; LTD, long-term depression; Imp. Cog., impaired cognition; PR, partial reversal

Note. All studies were conducted in adult male rodents unless noted otherwise. Additionally, all LTP and LDP recordings were conducted in the CA1 region unless noted otherwise.

When studying the effects of STZ-induced diabetes on LTP, the duration of diabetes ranged from 3 weeks up to 8 months (Stranahan et al., 2008; Stranahan et al., 2010). The impairment of LTP worsened with the increasing age of the animal (Kamal et al., 2000), duration of the diabetes (Kamal et al., 2005), and severity of the diabetes (Artola et al., 2002). While STZ-induced diabetes decreased LTP, it also increased long-term depression (LTD) of CA1 neurons (Artola et al., 2002; Kamal et al., 2000). These changes in hippocampal LTP and LTD, in T1D-like rodents, have consistently been associated with impaired spatial learning and memory in the Morris water maze (Jing et al., 2008; Kamal et al., 2000; Manschot et al., 2003). Impaired LTP in T1D-like rodents led to cognitive impairment in other types of tests as well such as the conditioned active avoidance test (Jing et al., 2008). Juvenile T1D, also caused cognitive impairment, as measured by the Y-Maze, but the properties of juvenile hippocampal neurons exposed to diabetes differed from that of adult hippocampal neurons exposed to hyperglycemia (Iwai et al., 2009). STZ administered to 17 day old rats resulted in no change in LTP and decreased LTD (Iwai et al., 2009), which is the opposite of what occurred in T1D-like adult rats (Kamal et al., 2000). Since T1D results in cognitive impairment in both young and adult rats, this suggests that LTP and LTD contribute differently to cognitive function in juvenile onset versus adult onset diabetes. Insulin reversed the impairment of LTP if initiated shortly after STZ administration but only partially restored deficits if initiated after 10 weeks of diabetes (Biessels et al., 1998).

T2D in rodents, induced by high fat diet, also consistently decreased LTP in CA1 neurons (see Table 4). These diabetic rodents also had impaired cognition in the Morris water maze (Stranahan et al., 2008) and novel object recognition test (Gault et al., 2010; Porter et al., 2011). The Zucker Diabetic rat showed preserved hippocampal function with normal induction of LTP in CA1 neurons and performance in the Morris water maze (Belanger et al., 2004). However, another study of LTP in the Zucker Diabetic rat showed decreased LTP in CA1 neurons, similar to other diabetes models (Alzoubi et al., 2005).

Demonstrations of treatments for diabetic-impaired LTP have involved a number of different pathways. There have been promising effects of drugs that target glucocorticoids (Stranahan et al., 2010), GLP-1 (Gault et al., 2010; Iwai et al., 2009), glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (Porter et al., 2011), and glucose control (Izumi et al., 2003). Initiation of treatment shortly after diabetes induction with enalapril, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, and nimodipine, a calcium channel blocker, prevented diabetes-induced alterations in LTP but delayed treatment was not able to reverse already existing hippocampal damage (Biessels et al., 2005; Manschot et al., 2003). The results of these studies imply that there may be a window of opportunity to reverse neurobehavioral complications from diabetes. More studies are needed to explore different treatments that can prevent and/or reverse these deficits.

7.3. Apoptosis and cell death

Apoptosis is a process of programmed cell death. Preclinical literature consistently report that the hippocampal environment of diabetic animals favors apoptosis, as evidenced by significant elevations in apoptotic markers (see Table 5). Hippocampal apoptosis in both T1D and T2D was associated with cognitive impairment in the Morris water maze (Jafari Anarkooli et al., 2008; Kuhad et al., 2009). Ten weeks of treatment with an anti-oxidant, tocotrienol, decreased neuroinflammation and improved cognition in STZ diabetic rats (Kuhad et al., 2009). Furthermore, STZ-treated rats that received eight weeks of fish oil treatment, another supplement with anti-oxidant properties, also had a significant decrease in the number of neurons with apoptotic markers (Cosar et al., 2008).

Table 5. Effects of Diabetes on Hippocampal Apoptosis.

| Model | Species | Effect on Apoptosis | Associated Behavior | Treatments that Reversed Changes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STZ | Rat | Increased | Impaired Cognition | Anarkooli et al. (2008) | |

| STZ | Rat | Increased | Fish oil n-3 Essential Fatty Acid | Cosar et al. (2008) | |

| STZ | Rat | Increased | Duarte et al. (2007) | ||

| STZ | Rat | Increased | Radiation Therapy | Kang et al. (2005) | |

| STZ | Rat | Increased | Impaired Cognition | Tocotrienol | Kuhad et al. (2008) |

| STZ | Rat | Increased | dl-3-n-butylphthalide | Zhang et al. (2010) | |

| BB/Wor | Rat | Increased | C-peptide Replacement | Li et al. (2002) | |

| BB/Wor | Rat | Increased | Li et al. (2005) | ||

| BB/Wor | Rat | Increased | C-Peptide Replacement | Sima et al. (2005) | |

| BBZDR/Wor | Rat | Increased | Impaired Cognition | Li et al. (2002) |

Abbreviations: STZ, streptozotocin

Although direct comparisons are difficult, a T1D-like rat model affected hippocampal apoptosis with a greater degree of neuronal loss and through different mechanisms than a T2D-like rat model (Li et al., 2005). The T1D-like model had apoptosis resulting from both caspase-dependent and PARP-mediated caspase-independent mechanisms, while the T2D-like model only expressed apoptosis resulting from the PARP-mediated mechanism (Li et al., 2005).

A critical difference between T1D and T2D is the availability of insulin. T1D results from hypoinsulinemia while T2D has hyperinsulinemia with decreased insulin receptor sensitivity. The differences in pathology could lead to different treatments for neurobehavioral complications from T1D and T2D. When the body makes insulin, it cleaves proinsulin to insulin and releases C-peptide. Thus, T1D lacks not only insulin, but also C-peptide, a peptide with established neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects (Luppi et al., 2011). Replacement of C-peptide in rodents with T1D significantly improved cognition (Sima and Li, 2005), lowered neuronal apoptosis and reversed hippocampal damage by lowering oxidative stress without altering plasma glucose levels (Li et al., 2002; Sima and Li, 2005). Rodents with T2D had elevated levels of C-peptide, due to hyperinsulinemia, yet still resulted in hippocampal damage, raising the question of whether resistance to C-peptide has been developed in T2D as well. Alternatively, there might be a therapeutic range for C-peptide levels since it has not yet been determined if lowering C-peptide levels could restore hippocampal structure and function in T2D or whether further elevating C-peptide in T1D would reinstate hippocampal deficits. Nevertheless, T1D and T2D can lead to impaired hippocampal neuroplasticity through different mechanisms and may sometimes benefit from different treatment approaches.

8. Measuring hippocampal neurogenesis in humans

Most research examining hippocampal neurogenesis would be expected to remain at the preclinical level primarily because techniques for measuring neurogenesis require post-mortem brain tissue. Further, patients with other illnesses, in addition to diabetes, may complicate findings relevant to neurogenesis. Nevertheless, human studies are necessary to move the science forward. Brain banks may provide access to a population of people who had diabetes and few other illnesses. Large scale clinicopathological study programs of aging frequently include tissues from people with and without diabetes and may allow direct testing of neurogenesis and other mechanisms that have only been investigated in animal models so far. If brain tissue in humans is obtained, one can then compare hippocampal neurogenesis using methods similar to those used in animals (Crews et al., 2010). Other methods, such as cell culture, may be used to see how the cells from different populations respond to various conditions and treatments (Paradisi et al., 2010).

Non-invasive imaging and indirect measures are currently being used to estimate hippocampal neurogenesis in humans. In the past, some human magnetic resonance imaging studies of patients with diabetes showed evidence for hippocampal atrophy (Gold et al., 2007; Hershey et al., 2010). Rather than measuring the entire hippocampus, subfield analysis with high resolution magnetic resonance imaging may provide a way to specifically target the neurogenic regions of the hippocampus (Neylan et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2010) and may show different effects of diabetes on different parts of the hippocampus. A new imaging method was developed recently to study hippocampal neurogenesis in vivo by employing magnetic spectroscopy to visualize a potential biological marker for neural stem and progenitor cells (Manganas et al., 2007). This method has never been used to study the effects of diabetes on hippocampal neurogenesis and very few published studies have applied this method. Although requiring greater optimization, more technological advances such as these are needed and collaborating with other disciplines such as bioengineering can facilitate this process. Until the field develops better methods, human studies of neurogenesis will rely on indirect measures, like hippocampal volume and biomarkers.

9. Future directions

The results from the majority of preclinical studies indicate that diabetes negatively impacts hippocampal cell proliferation and survival. Diabetes also produces evidence for dysfunction on other morphological and functional measures of hippocampal neuroplasticity, including dendritic remodeling, decreased long-term potentiation, and increased apoptosis, indicating diminished function of this brain region. In many studies, altered hippocampal neuroplasticity in diabetic rodents was accompanied by behavioral evidence of cognitive deficits, as measured by tasks for associative and spatial learning, recognition and memory or alteration of behaviors associated with depression. Thus, the functional integration between hippocampal neurogenesis, neuroplasticity and performance in tests of cognitive and affective behaviors in diabetic rodents provides an experimental framework for studying neurobehavioral complications associated with diabetes. This framework would be most useful for: 1) understanding the mechanisms associated with the development of pathologies leading to cognitive and affective disturbances in diabetes and 2) investigating the utility and limitations of different approaches for treating behavioral changes associated with diabetes.

9.1. Pathological mechanisms leading to cognitive and affective loss in diabetes

Although the negative effects on hippocampal neuroplasticity from diabetes might explain the development of comorbid complications such as cognitive decline or depression, studies have not yet addressed the precise mechanisms underlying those developments. A number of risk factors have been identified from epidemiological studies that contribute susceptibility to depression and diabetes, such as childhood rearing, improper diet, sedentary lifestyle and history of substance abuse. Specific risk factors are likely to contribute to sex and age differences associated with the risk for depression and diabetes. Animal studies can model the extent and mechanisms of physiological contributors to diabetes in a controlled manner that informs and extends human epidemiological studies.