Abstract

Objective

To explore possible factors which might impact a patient’s choice to pursue endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) or continue with medical management for treatment of refractory chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS).

Study Design

Cross-sectional evaluation of a multi-center, prospective cohort

Methods

242 subjects with CRS were prospectively enrolled within four academic, tertiary care centers across North America with ongoing symptoms despite prior medical treatment. Subjects either self-selected continued medical management (n=62) or ESS (n=180) for treatment of sinonasal symptoms. Differences in demographics, comorbid conditions, and clinical measures of disease severity between subject groups were compared. Validated metrics of social support, personality, risk aversion, and physician-patient relationships were compared using bivariate analyses, predicted probabilities, and receiver operating characteristic curves at the 0.05 alpha level.

Results

No significant differences were found between treatment groups for any demographic characteristic, clinical cofactor, or measure of social support, personality, or the physician-patient relationship. Subjects electing to pursue sinus surgery did report significantly worse average quality-of-life (QOL) scores on the 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test (SNOT-22; p<0.001) compared to those electing continued medical therapy (54.6±18.9 vs. 39.4±17.7), regardless of surgical history or polyp status. SNOT-22 score significantly predicted treatment selection (OR=1.046; 95% CI: 1.028,1.065; p<0.001) and was found to accurately discriminate between subjects choosing endoscopic sinus surgery and those electing medical management 72% of the time.

Conclusion

Worse patient-reported disease-severity, as measured by the SNOT-22, was significantly associated with the treatment choice for CRS. Strong consideration should be given for incorporating CRS-specific QOL measures into routine clinical practice.

Keywords: Chronic disease, sinusitis, decision making, general surgery, drug therapy, therapeutics

Introduction

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is a common health condition characterized by diffuse inflammation of the sinonasal mucosa. The health states described by patients with CRS are often equal to or worse than other chronic diseases such as congestive heart failure, angina, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.1,2 A recent multi-institutional cohort study examined long-term outcomes in patients with ongoing disease despite prior medical management.3 The cohort who underwent sinus surgery experienced significantly greater improvements in disease-specific quality-of-life (QOL) as compared to patients continuing solely with medical management. Similar gains were seen in a cohort who later crossed-over from the medical management to the surgical treatment arm.4

To date, there has been little investigation of what determines a patient’s choice to pursue sinus surgery. One might hypothesize that this decision could be multifactorial and influenced by demographics, economic resources, patient personality, the physician-patient relationship, and overall disease severity. A thorough understanding of these influences has important clinical and research implications, particularly given the differential outcomes reported between medical and surgical treatments. The goal of this study was to comprehensively explore those factors which might impact a patient’s choice to pursue endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) or to continue with medical management of CRS.

Methods

Study Enrollment

Adult patients (≥18 years) with CRS were enrolled into a prospective, observational cohort study from 4 medical centers across North America: the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), University of Calgary (Calgary), Stanford University (Stanford), and Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU). All patients met diagnostic criteria for CRS according to the 2007 Adult Sinusitis Guideline endorsed by the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery.5 Each patient had ongoing CRS-specific symptoms, evidence of inflammation on either sinonasal endoscopy or computed tomography (CT) imaging, and had been treated with a minimum of oral antibiotics (≥2 weeks duration) and topical nasal steroids (≥3 weeks duration). In each instance, the treating physician determined the patient to be an appropriate candidate for ESS and offered the patient the option to pursue ESS or continue with ongoing medical management. Those patients electing to continue with medical therapy constituted the medical cohort and those undergoing ESS comprised the surgical cohort. Informed consent was obtained from each participant and study protocols were monitored and approved by the Institutional Review Board at each enrollment site.

Data collection

Demographics and Medical Comorbidities

Patient-reported data was collected by a study coordinator at the conclusion of their clinic visit using standardized forms. Demographic data included age, gender, and race/ethnicity. The presence of medical comorbidities was determined by patient history and clinical examination, including sinonasal polyposis, prior sinus surgery, allergic rhinitis, asthma, acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) intolerance, smoking status, and depression.

Economic Factors

Economic measures included household income in dollars/year (Canadian or United States (U.S.) dollars). Type of medical payment coverage was also assessed and categorized as self-pay, private/employer provided insurance, Medicaid, Medicare (Canadian or U.S.), and Veteran’s Administration benefits.

Social Support, Personality, Risk Aversion, and Physician-Patient Relationship

Social support was assessed using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS).6 The MSPSS consists of 12 questions divided into 3 subscales (Family, Friends, and Significant Other). Higher mean scores for each subscale reflect greater perceived social support for the patient (score range: 1–7). Patient personality profile was assessed using the Big Five Inventory-10 Short Version (BFI-10S).7 This 10-item model evaluates five major personality dimensions, including extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience. Higher mean scores indicate a greater level of that particular personality trait. Four questions were adapted from the Jackson Personality Inventory (JPI) to assess a subject’s willingness to accept risk.8 Categorical responses to each question were recorded based on whether they “Disagreed strongly”, “Disagreed somewhat”, “Agreed somewhat”, “Agreed strongly”, or were “Not sure” to the questions in Table 1.

Table 1.

Supplemental questions used to assess a subject’s willingness to accept physical risk.

| 1. “Taking risks does not bother me if the gains involved are high.” |

| 2. “I enjoy taking risks.” |

| 3. “People have told me that I seem to enjoy taking chances.” |

| 4. “I will not risk having surgery for any reason whatsoever.” |

Lastly, the physician-patient relationship was evaluated using the Trust in Physician Scale (TPS).9 The TPS is an 11-item survey scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). A summary measure of trust is obtained by taking the un-weighted mean of each response and transforming the value to a 0–100 score range, with higher scores reflecting greater trust. Respondents were instructed to consider the physician providing rhinologic treatment of their CRS.

Disease Severity Measures

Baseline CT and endoscopy scores were recorded for each subject utilizing the scoring systems of Lund-Mackay (score range: 0–24) and Lund-Kennedy (score range: 0–20).10,11 Sinus-specific QOL was measured using the Sinonasal Outcomes Test 22 (SNOT-22; score range: 0–120).12 Discriminative olfactory ability was measured using the 12-item Brief Smell Identification Test (B-SIT; score range: 0–12; Sensonics Inc., Haddon Heights, NJ).13

Data Analysis

The overall CRS cohort was divided into medical and surgical management arms as elected during the initial enrollment period. Differences in demographics, medical comorbidities, disease severity, economic factors, social support, personality traits, risk aversion, and trust in physician were compared between treatment groups. Means of normally-distributed, continuous measures were compared using two-sided, independent sample t-tests, whereas categorical variables were compared using chi-square (χ2) tests. Non-normally distributed categorical data was analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. For any diagnostic factor found to be significantly different between groups, the ability of each measure to accurately predict choice of treatment strategy was assessed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves with corresponding areas under the curve (AUC), as well as predicted probability estimates using simple logistic regression. For all analyses, frequencies, means ± standard deviations (SD) are provided where appropriate and a p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. Given the large number of statistical tests employed, significant values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Bonferonni method where appropriate.

Results

A total of 242 patients with ongoing CRS were prospectively enrolled into the study and offered the option to pursue ESS or continue with medical management (OHSU=151; Stanford=47; Calgary=24; MUSC=20). Just under half of the patients had a history of prior sinus surgery (116/242=47.9%). All patients had previously received at least 2 weeks of oral antibiotics and 3 weeks of topical nasal steroids per inclusion criteria. The vast majority of patients had taken more than one course of oral antibiotics (95.9%) and received at least 5 days of systemic corticosteroid therapy (95.9%). Sixty-two patients elected to continue with medical management while 180 patients chose to undergo ESS as their next treatment option.

Demographics and Medical Comorbidities

Demographic factors were compared between the medical and surgical cohorts and there were no significant differences in age (p=0.369), gender (p=0.232), race (p=0.772), or ethnicity (p=0.454) between those electing to continue with medical treatment and those pursuing surgery. Similarly, there was no significant difference in medical comorbidities, including presence of nasal polyposis, allergic rhinitis, asthma, ASA intolerance, smoking status, depression, or prior sinus surgery (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comorbid factors for medical management and sinus surgery treatment cohorts (n=242)

| Medical management cohort (n=62) |

Endoscopic sinus surgery cohort (n=180) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidity: | n (%) | n (%) | X2 | p |

| Nasal polyposis | 22 (35.5) | 59 (32.8) | 0.152 | 0.697 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 15 (24.2) | 47 (26.1) | 0.089 | 0.765 |

| Asthma | 18 (29.0) | 64 (35.6) | 0.876 | 0.349 |

| ASA Intolerance | 5 (8.1) | 10 (5.6) | 0.499 | 0.480 |

| Current smoker | 0 (0.0) | 12 (6.7) | 4.349 | 0.081 |

| Depression | 8 (12.9) | 37 (20.6) | 1.784 | 0.182 |

| Prior sinus surgery | 31 (50.0) | 85 (47.2) | 0.143 | 0.706 |

Economic Factors

The majority of patients in both the medical management and surgical treatment groups reported yearly household incomes in excess of $50,000/year (64.5% and 66.7%, respectively). An equal distribution reported incomes in excess of $100,000/year (25.8% and 26.1%, respectively). Household income was further analyzed after categorizing the data into $25,000 increments; however, no significant differences were noted between groups. The majority of both medical and surgical patients had employer provided insurance (58.1% and 57.2%, respectively). No significant differences were noted in types of medical insurance coverage between those continuing with medical therapy and those choosing surgery (p=0.660).

Social Support, Personality, Risk Aversion, and Physician-Patient Relationship

Patients with CRS in this study reported overall high mean social support as measured by the MSPSS instrument (5.8±1.8; score range: 1–7). There was no difference in total mean MSPSS scores between patients continuing with medical therapy and those choosing to undergo surgery (5.8±1.1 vs. 5.8±1.1; p=0.940). Similarly there was no difference in subscales of the MSPSS between groups, including perceived social support from friends, family members, and special persons (p>0.140 for all; Table 3A).

Table 3a–c.

Mean comparisons between both medical management and sinus surgery treatment cohorts for responses to the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, the Big Five Inventory-10 Short Version survey, and clinical measures of disease severity (n=231).

| Medical management cohort (n=60) |

Endoscopic sinus surgery cohort (n=171) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| A. MSPSS Subscales: | mean ± SD | mean ± SD | p |

| Friends | 5.4 ± 1.3 | 5.7 ± 1.3 | 0.140 |

| Family Members | 6.0 ± 1.1 | 5.8± 1.4 | 0.475 |

| Special Persons | 6.2 ± 1.2 | 6.1 ± 1.3 | 0.550 |

| B. BFI Traits: | mean ± SD | mean ± SD | p |

| Conscientiousness | 4.4 (0.8) | 4.3(0.8) | 0.450 |

| Extraversion | 3.2 (1.0) | 3.3 (1.1) | 0.519 |

| Agreeableness | 3.8 (0.9) | 3.8 (0.9) | 0.770 |

| Openness | 3.7 (1.0) | 3.6 (1.0) | 0.412 |

| Neuroticism | 2.4 (1.1) | 2.6 (1.1) | 0.076 |

| C. Disease Severity Measures: | mean ± SD | mean ± SD | p |

| Endoscopy score | 6.9 ± 4.3 | 6.4 ± 3.7 | 0.372 |

| Computed tomography score | 12.3 ± 6.6 | 12.3 ± 5.8 | 0.955 |

| B-SIT Olfactory score | 9.0 ± 3.2 | 9.4 ± 3.0 | 0.414 |

A total of 231 patients provided data regarding personality traits according to the BFI-10S. Across all patients, highest mean scores were seen for the conscientious personality trait (4.3±0.8; score range: 2–5) and lowest scores for neuroticism (2.6±1.1; score range: 1–5). When comparing medical and surgical cohorts, no differences were seen for any of the five traits, including conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, openness, or neuroticism (p>0.076 for all; Table 3B).

Categorical responses to four questions from the JPI related to risk were compared between medical and surgical groups. No significant differences were found for three of four risk-related questions. Differential responses were seen for the statement “I will not risk having surgery for any reason whatsoever”, with more patients in the surgical cohort disagreeing (90.0% vs 78.3%; p=0.044). However, this difference was no longer significant after multiple comparisons adjustment.

Using the TPS scale as a summary measure of physician trust, both medical (n=61) and surgical (n=170) groups indicated high levels of trust with their treating physician, with no significant difference based on choice of treatment strategy at enrollment (68.8±12.2 vs. 69.6±13.5; p=0.690).

Disease Severity Measures

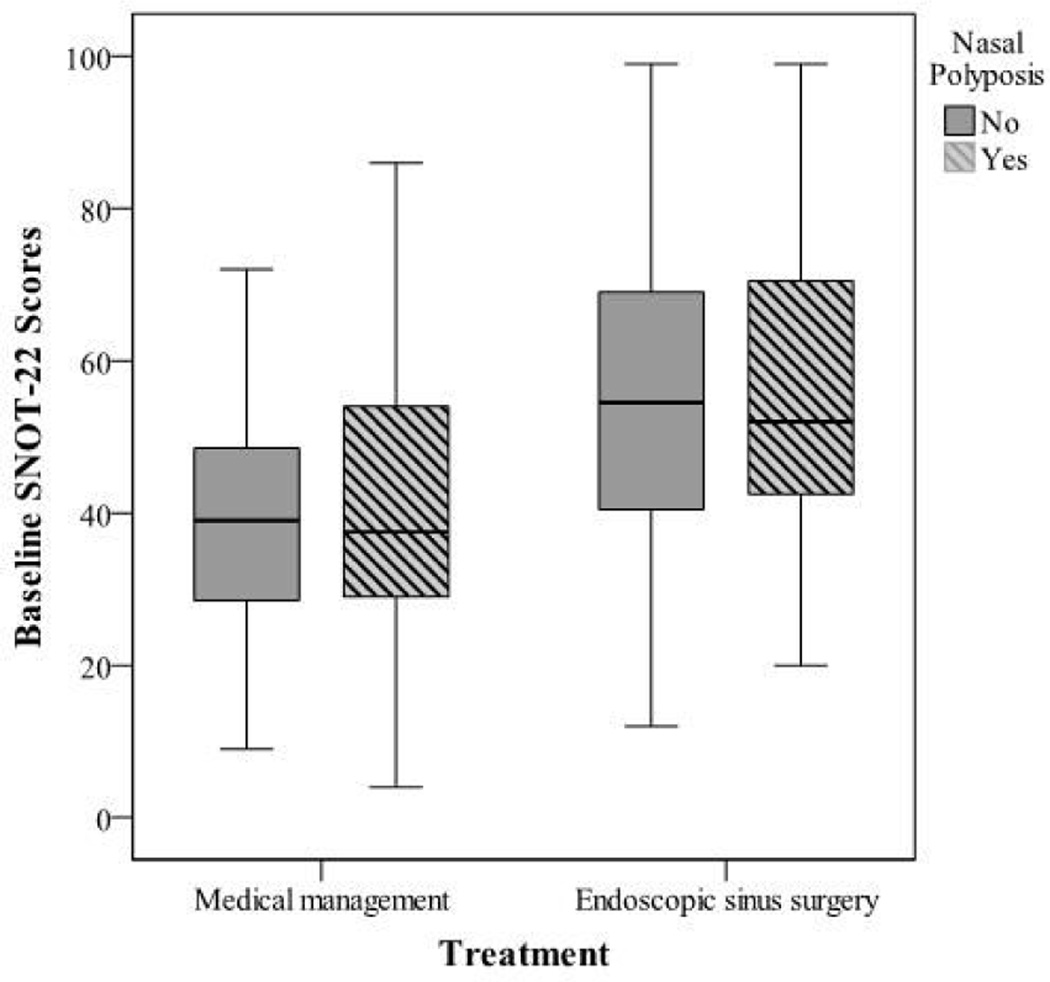

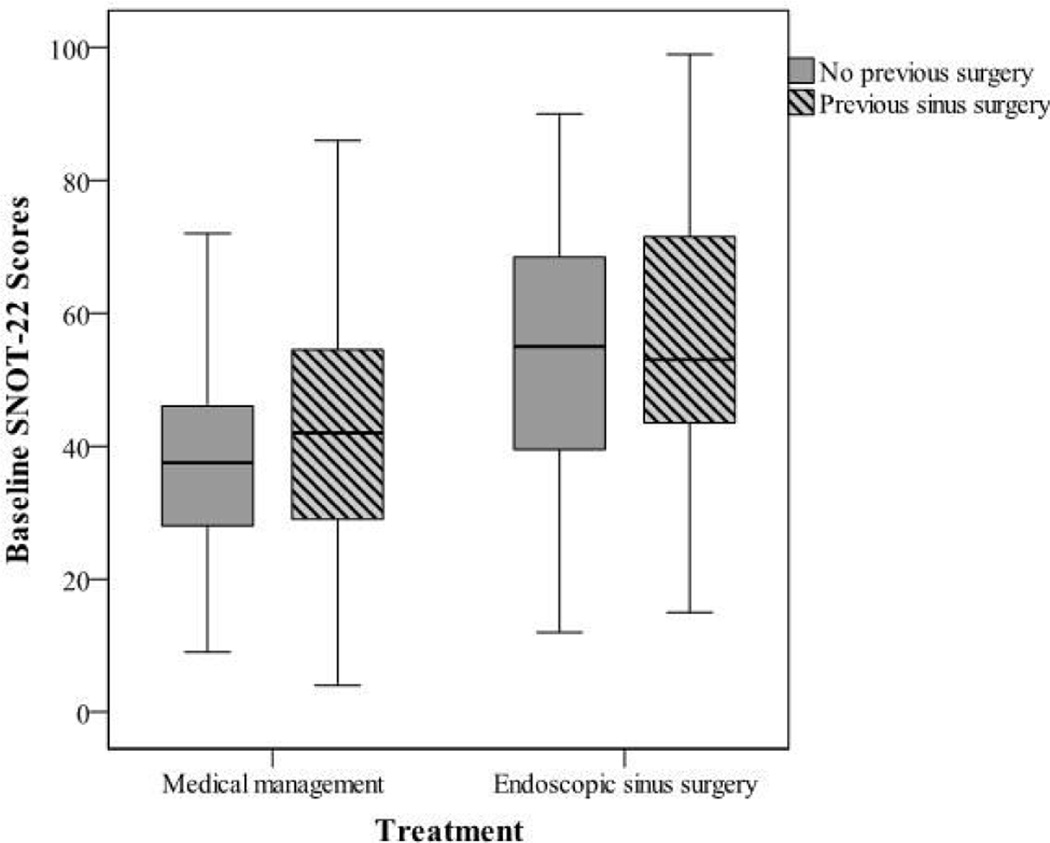

Severity of disease as measured by CT score did not differ between those choosing medical management and those electing sinus surgery (Table 3C). Similarly, there was no difference in sinonasal endoscopy scores or olfactory function as measured by B-SIT score between groups. Those electing to pursue sinus surgery did report significantly worse mean scores on the SNOT-22 QOL instrument as compared to those continuing with medical therapy (54.6±18.9 vs 39.4±17.7; p<0.001). This difference in disease-specific QOL between treatment arms was robust enough to survive Bonferonni multiple comparisons adjustment and would be considered clinically significant based on the published minimal clinically-important difference (MCID) for the SNOT-22 instrument.12 Patients choosing surgery were more symptomatic (higher SNOT-22 scores) regardless of prior surgery or the presence of polyps (p<0.001 for all; Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

SNOT-22 survey scores for treatment cohorts with and without nasal polyposis

Figure 2.

SNOT-22 survey scores for treatment cohorts with and without prior sinus surgery

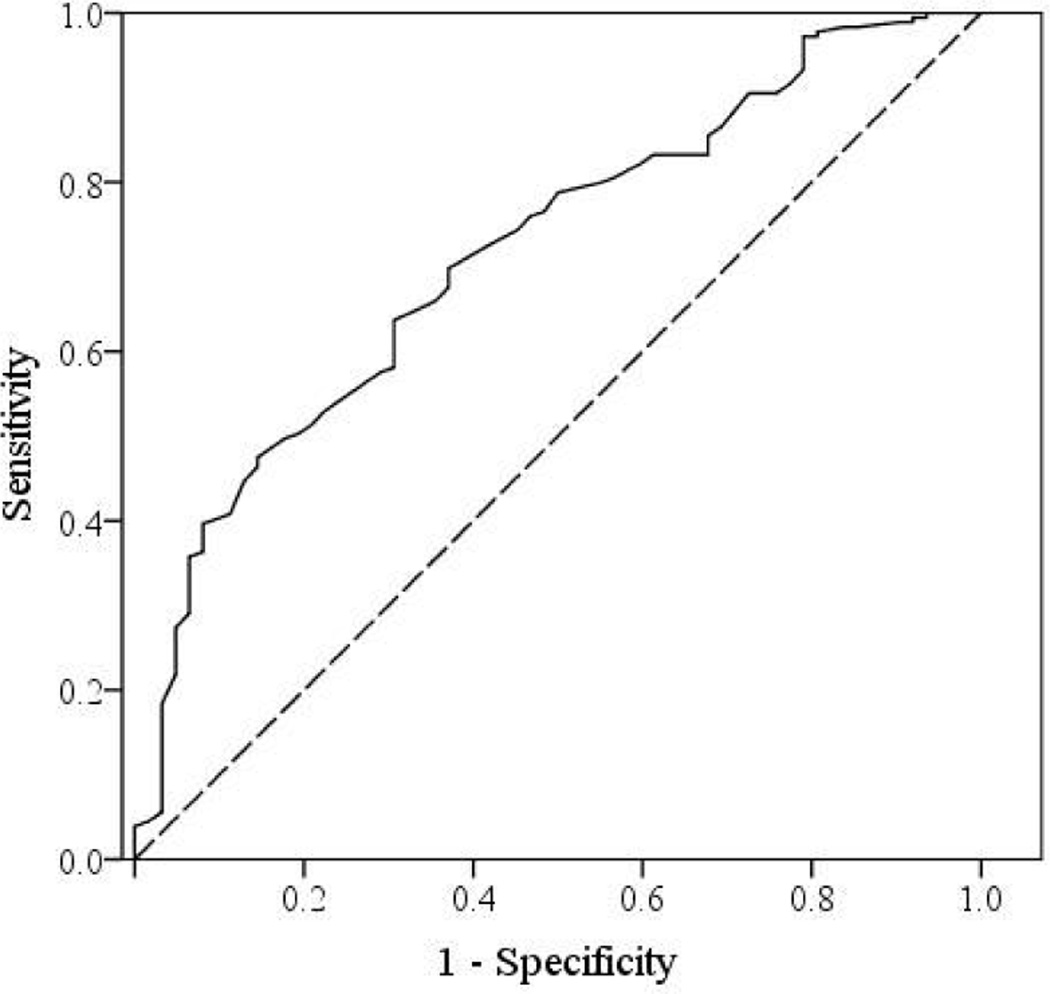

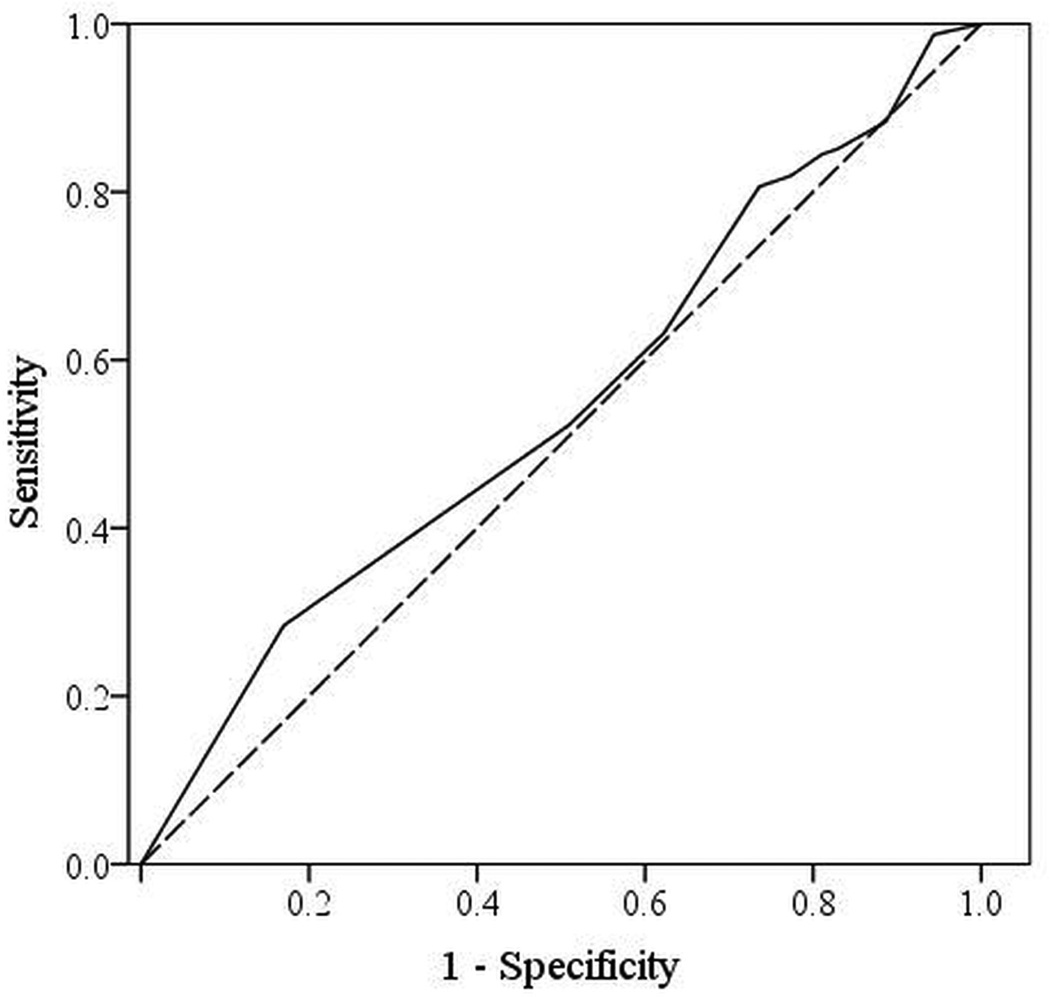

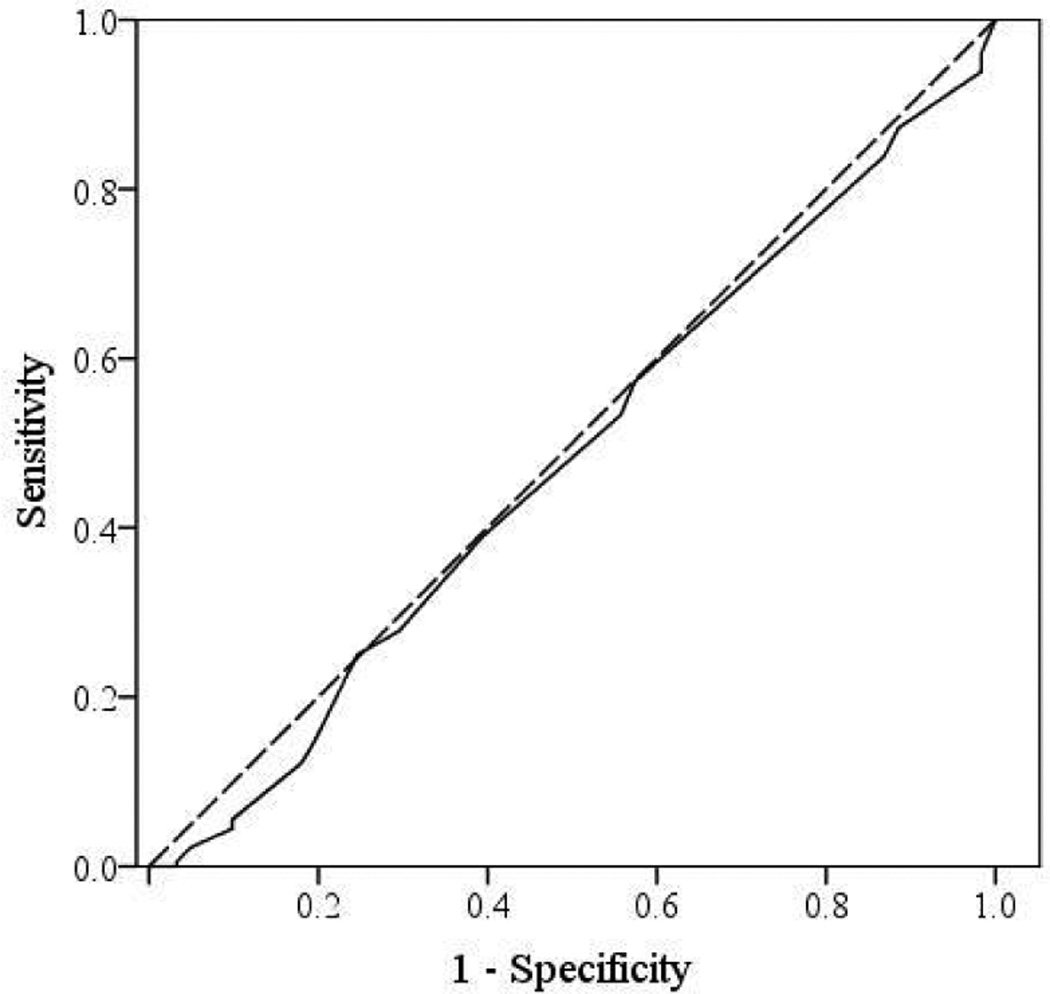

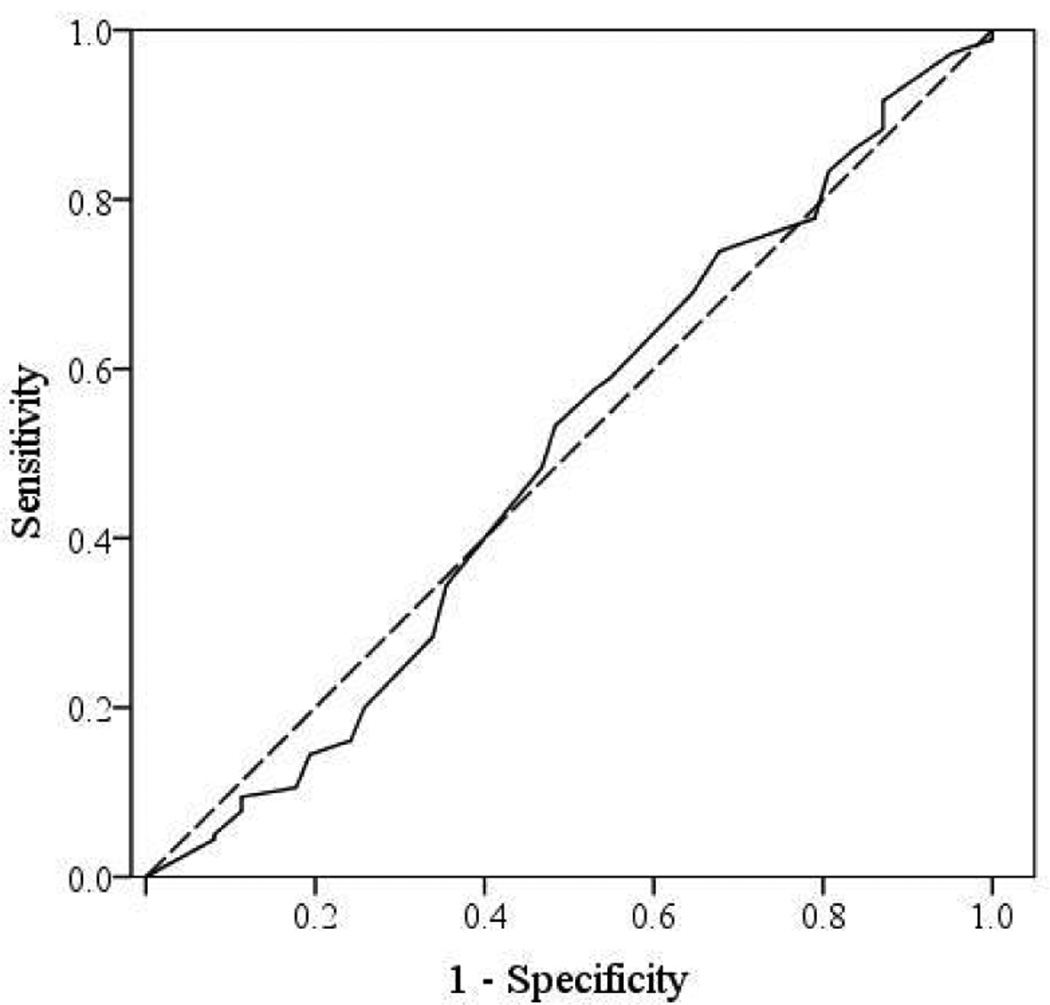

ROC curves for each disease severity measure are shown in Figure 3–6 for comparison. Only findings from the SNOT-22 QOL instrument were found to significantly predict a patient’s choice to pursue sinus surgery (AUC=0.718; 95%CI: 0.647–0.789; p<0.001). For these findings, SNOT-22 scores accurately discriminate between those choosing endoscopic sinus surgery and those electing medical management 72% of the time. Without adjustment for any other clinical cofactors, the predicted probability of choosing sinus surgery based purely on baseline SNOT-22 scores was also generated from this cohort via simple logistic regression. Overall model fit was adequate via the Hosmer & Lemeshow test (χ2 = 8.87, p=0.354), while SNOT-22 score was a significant independent predictor of treatment selection (OR=1.046; 95% CI: 1.028, 1.065; p<0.001). Available SNOT-22 scores in increments of 10 were identified within the dataset and presented in Table 4 with corresponding unadjusted probabilities of selecting sinus surgery.

Figure 3.

ROC curve for SNOT-22 survey scores. ROC=receiver operating characteristic curve.

Figure 6.

ROC curve for Brief Modified Smell Identification Test scores

Table 4.

Predicted probability of treatment selection using SNOT-22 survey scores

| Baseline SNOT-22 Score: | Predicted Probability of Sinus Surgery: |

|---|---|

| 20 | 46.4% |

| 30 | 57.6% |

| 40 | 68.0% |

| 50 | 77.0% |

| 60 | 84.0% |

| 70 | 89.1% |

| 80 | 92.8% |

| 90 | 95.3% |

Discussion

This is the first study to comprehensively explore factors which might impact a patient’s choice to pursue sinus surgery or continue with medical management in an ambulatory, tertiary care setting. To our surprise, economic factors, patient personality profiles, social support structures, and a patient’s trust in their physician had little impact on their choice of treatment strategy. CRS-specific QOL, as measured by the SNOT-22, was the only robust determinant of whether a patient chose one management strategy or the other. These findings have several important clinical and research-related implications.

At present, many consider disease-specific QOL to be the gold standard clinical outcome metric for CRS. This assertion is based in part on the inconsistent correlation between CRS-specific QOL and other objective measures such as CT or endoscopy scores.14,15 Data from this study show that CRS-specific QOL is the main driver of patient-focused clinical decision-making; whereas, the severity of CT scores, endoscopy findings, and objective olfactory function had essentially no impact on a patient’s choice of management strategy. These findings suggest that the severity of disease as measured by CT and endoscopy should have a limited role in clinical decision-making, at least insofar as they are currently graded. This concept is further supported by a study from Rudmik et al. wherein CT scores failed to predict QOL outcomes after sinus surgery.16 It should be kept in mind that all patients required visible disease on either CT scan or endoscopy in order to satisfy diagnostic criteria for CRS and entry into this study. Therefore, at minimum, CT and endoscopy serve a role as dichotomous measures supporting the accurate diagnosis of CRS and presence of ongoing inflammation.

Outcomes research related to CRS treatment has evolved over time from primarily single institution, retrospective case series to prospective, multi-institutional cohort studies.17 Although randomized clinical trials comparing medical to surgical treatment are considered most rigorous, their feasibility is questionable given the inherent difficulty randomizing patients to a treatment strategy that might include surgery. Without randomization, however, comparison studies may be biased by confounding factors which influence both treatment allocation and ultimate outcomes after a given treatment. In this study, we hypothesized that many factors would affect a patient’s choice of treatment strategy and thus could serve as potential confounding factors in future observational outcomes studies. As measured in this study, demographics, economic factors, social support structures, personality-profiles, and the physician-patient relationship did not affect treatment allocation and thus would not be expected to confound future outcome measures. The multi-institutional nature of this study, large sample size, and use of validated measures suggests that these findings are robust; however, the possibility always exists that confounding by these covariates exists but was simply not detected by the metrics used in this study. It certainly remains possible that other factors not assessed in this study could affect patient decision-making, such as other medical comorbidities or as yet unknown CRS subtypes.

The ROC curve analysis and predictive probability estimates suggest that the SNOT-22 score alone can be used to determine with reasonable accuracy the likelihood that a patient chooses surgery. Although this is true for our cohort of patients, clinicians should be careful extrapolating this data to their individual clinical practices. Patients in this study were recruited from tertiary rhinology clinics across North America and may not fully represent all patients with CRS; therefore, specific probabilities may not be externally generalizable to the community setting or to patients from other countries and cultures. We do feel that this data argues strongly that disease-specific QOL is the preeminent disease-severity measure for CRS and efforts should be made by clinicians to incorporate this metric into routine clinical practice.

Conclusion

Patients with ongoing CRS despite prior medical therapy often face the decision to continue with medical treatment or pursue sinus surgery. Most factors examined in this study were not found to impact this decision, including demographics, economic factors, social support structures, personality-profiles, the physician-patient relationship, or most disease-severity measures. Worse disease-specific QOL, as measured by the SNOT-22, was the only factor significantly associated with the choice of sinus surgery. Strong consideration should be given to incorporating CRS-specific QOL measures into routine clinical practice.

Figure 4.

ROC curve for Lund-Kennedy endoscopy scores.

Figure 5.

ROC curve for Lund-Mackay computed tomography scores

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosure: Zachary M. Soler, MD, MSc, Peter H. Hwang, MD, Jess C. Mace, MPH, and Timothy L. Smith, MD, MPH are supported by a grant from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), one of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. (2R01 DC005805; PI: T.L. Smith). Public clinical trial registration (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov) ID#NCT01332136. Timothy L. Smith, MD is also a consultant for Intersect ENT (Palo Alto, CA.) which is not affiliated in any way with this investigation.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

Submitted for oral presentation at the 116th Annual Meeting of the Triological Society within the Combined Otolaryngology Spring Meetings in Orlando, Florida in April 10–14, 2013.

References

- 1.Soler ZM, Wittenberg E, Schlosser RJ, Mace JC, Smith TL. Health state utility values in patients undergoing endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 2011;121(12):2672–2678. doi: 10.1002/lary.21847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gliklich RE, Metson R. The health impact of chronic sinusitis in patients seeking otolaryngologic care. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;113(1):104–109. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989570152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith TL, Kern RC, Palmer JN, et al. Medical therapy vs surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis: a prospective, multi-institutional study. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2011;1(4):235–241. doi: 10.1002/alr.20063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith TL, Kern R, Palmer JN, et al. Medical therapy vs surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis: a prospective, multi-institutional study with 1-year follow-up. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2012 doi: 10.1002/alr.21065. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, et al. Clinical practice guideline. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(Suppl):S1–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.06.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52:30–41. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rammstedt B, John OP. Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. J Res Pers. 2007;41:203–212. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson DN. Interpreter’s guide to the Jackson Personality Inventory. In: McReynolds P, editor. Advances in Psychological Assessment. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1978. pp. P1–P41. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson LA, Dedrick RF. Development of the trust in physician scale: a measure to assess interpersonal trust in patient-physician relationships. PsycholRep. 1990;67(3 Pt 2):1091–1100. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1990.67.3f.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lund VJ, Kennedy DW. Staging for rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117(3 Pt 2):S35–S40. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989770005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lund VJ, Mackay IS. Staging in rhinosinusitis. Rhinology. 1993;31(4):183–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopkins C, Gillett S, Slack R, et al. Psychometric validity of the 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test. Clin Otolaryngol. 2009;34(5):447–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2009.01995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doty RL, Marcus A, Lee WW. Development of the 12-item cross-cultural smell identification test (CC-SIT) Laryngoscope. 1996;106(3 Pt 1):353–356. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199603000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng Y, Zhao Y, Lv D, Liu Y, Qiao X, An P, Wang D. Correlation between computed tomography staging and quality of life instruments in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2010;24(1):e41–e45. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2010.24.3430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wabnitz DA, Nair S, Wormald PJ. Correlation between preoperative symptom scores, quality-of-life questionnaires, and staging with computed tomography in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol. 2005;19(1):91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rudmik L, Mace J, Smith T. Low-stage computed tomography in chronic rhinosinusitis: what is the role of endoscopic sinus surgery? Laryngoscope. 2011;121(2):417–421. doi: 10.1002/lary.21382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soler ZM, Smith TL. Quality of life outcomes after functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2010 Jun;43(3):605–612. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]