Abstract

Traditionally, microglia have been considered to act as macrophages of the central nervous system. While this concept still remains true it is also becoming increasingly apparent that microglia are involved in a host of non-immunological activities, such as monitoring synaptic function and maintaining synaptic integrity. It has also become apparent that microglia are exquisitely sensitive to perturbation by environmental challenges. The aim of the current review is to critically examine the now substantial literature that has developed around the ability of acute, sub-chronic and chronic stressors to alter microglial structure and function. The vast majority of studies have demonstrated that stress promotes significant structural remodelling of microglia, and can enhance the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines from microglia. Mechanistically, many of these effects appear to be driven by traditional stress-linked signalling molecules, namely corticosterone and norepinephrine. The specific effects of these signalling molecules are, however, complex as they can exert both inhibitory and suppressive effects on microglia depending upon the duration and intensity of exposure. Importantly, research has now shown that these stress-induced microglial alterations, rather than being epiphenomena, have broader behavioural implications, with the available evidence implicating microglia in directly regulating certain aspects of cognitive function and emotional regulation.

Keywords: Acute stress, chronic stress, depression, glia, inflammation, microglia, mood disturbance, neuroinflammation, neuroplasticity, remodelling

INTRODUCTION

How exposure to stressful events, both acute and chronic in nature, promotes remodelling of the brain has been an area of intense interest for well over five decades. While this effort has been motivated in part by a basic desire to understand how the brain responds to challenging phenomena, a more substantial driver has been the link between exposure to stressful events and the emergence of serious cognitive and mood disturbance in humans [1]. Impressively, it has now been discovered that exposure to stress profoundly disrupts the release of multiple neurotransmitters systems; including serotonin, glutamate, GABA [2] and orexin, [3] while simultaneously inducing profound remodelling of neuronal architecture particularly within the amygdala, hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (PFC) [2, 4, 5]. Each of these discoveries, in addition to many others, has fundamentally reshaped our thinking about the neurobiological mechanisms we consider to be critical drivers of stress-linked psychopathology. Gradually, however, an increasing number of studies are reporting that stress, in addition to programming neuronal alterations, is at least as capable of disrupting glial networks [6-8]. Recognition of the ability of stress to modify glial function has also come at time when glia, and in particular microglia, have been shown to play a critical role in directly modulating neuronal architecture and function [9, 10]. The objective of the current review is to synthesise the evidence concerning the ability of both acute and chronic stressors to alter microglial structure and function and to outline the impact that these alterations appear to exert on the behaviour of the animal.

STRESS: A BIOLOGICAL MECHANISM TO ASSIST THE ORGANISM IN DEALING WITH UNCONTROLLABLE AND/OR UNPREDICTABLE THREATS

Given the focus of the current article on the effects of stress on glia, it will be useful to begin with a brief overview of what we mean by the term ‘stress’. As is widely recognised, the mammalian body has evolved in an environment in which it has been forced to deal with challenges on a moment-by-moment basis, with some being routine (e.g. temperature fluctuation) while others are life-threatening (e.g. predatory attack). Selye, was the first to explicitly formulate the idea that the body, in response to any serious challenge, can engage a non-selective response involving the reorientation of almost all of the organism’s cognitive and physiological systems to deal with the impending challenge [11]. The theoretical foundation established by Selye has now been substantially elaborated to differentiate between the event that causes a response in the body, and the body’s actual response to it. Specifically, it is now accepted that a ‘stressor’ is any stimulus (real or imagined) that threatens the body’s homeostatic balance, while by extension the stress response (often just shortened to stress) is the reaction of the body aimed at re-establishing homeostatic balance [11]. More recently, it has been proposed that this conceptualisation be extended to consider environmental events as stressors only if they are uncontrollable and/or unpredictable in nature [12] and are considered to be salient [13]. The magnitude of the stress response is determined by the intensity of these three combined factors and the biological history of the organism.

In terms of signalling it is now well established that two of the most significant systems engaged by the stress response are the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system and the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis [14]. In terms of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), the best-described action of stress is in initiating the release of epinephrine and norepinephrine (E/NE). These signalling molecules are renowned for their rapid physiological actions, and their release has been associated with the concept of the “fight or flight” response. Consistent with this concept, E/NE are associated with substantial increases heart rate, force of heart contractions, peripheral vasoconstriction, blood pressure and energy mobilisation. In contrast to the speed of the SNS response, the HPA axis response is muted, initiating a slow-rising surge of cortisol (CORT) that endures over the course of several hours. CORT is highly pleiotropic with respect to its effects and is known to modulate multiple immune functions, including cytokine expression, immune cell trafficking, immune cell maturation, and the production of chemoattractants. Additionally, CORT can influence glucose metabolism, blood pressure, lipid metabolism, deposition of glycogen, neurotransmission, renal activity, and muscle function [15]. In most situations, the actions of stress-induced CORT, like the effects E/NE are catabolic, the ultimate purpose of which is hypothesised to be the provision of sufficient resources to deal with a perceived stressor. Finally, on a cautionary note, while E/NE and CORT are without question the major contributors to the biological effects induced by exposure to stress they are very unlikely to account for all of the observed biological changes.

From an evolutionary standpoint, the benefit of a biological mechanism that can acutely and rapidly provide the body with sufficient resources to deal with serious and immediate challenges appears self-evident. Stress, however, is not always ‘good’. Serious problems can arise when the stress response is repeatedly engaged and/or inadequately terminated [15]. With respect to humans, it is now well established that chronic stress is a major risk factor for a variety of diseases, including diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, autoimmune diseases and cancer. At present, however, the strongest relationship between chronic stress and pathology has been the one that exists between stress and mood disorders, notably depression [1, 16].

MICROGLIA: A BRIEF PRIMER

Unlike other cell types in the central nervous system (CNS), microglia are hematopoietically derived cells of a monocyte/macrophage lineage, and have been extensively referred to as the macrophages of the CNS [17]. Estimates of microglial number within the brain vary considerably, however, it is currently estimated that approximately 10% of the brain’s cells are microglia [18, 19]. Under non-pathological conditions the full repertoire of activities that microglia are involved in are only just beginning to be understood. Despite this, the seminal studies of Nimmerjahn et al. [20] and Davalos et al. [21] have revealed the extraordinarily active nature of microglial processes in the healthy brain. Other recent work has indicated that, rather than being random, microglial process movement is preferentially directed towards synapses, with the apparent purpose of monitoring and regulating their activity [10, 22]. In contrast to the healthy brain, microglia involvement in initiating and regulating pro-inflammatory and cytotoxic responses to tissue injury with the CNS has been extensively documented, particularly within the context of neurodegenerative conditions [23-25].

MICROGLIAL ‘ACTIVATION’ UNDER INFLAMMATORY AND NON-INFLAMMATORY CONDITIONS

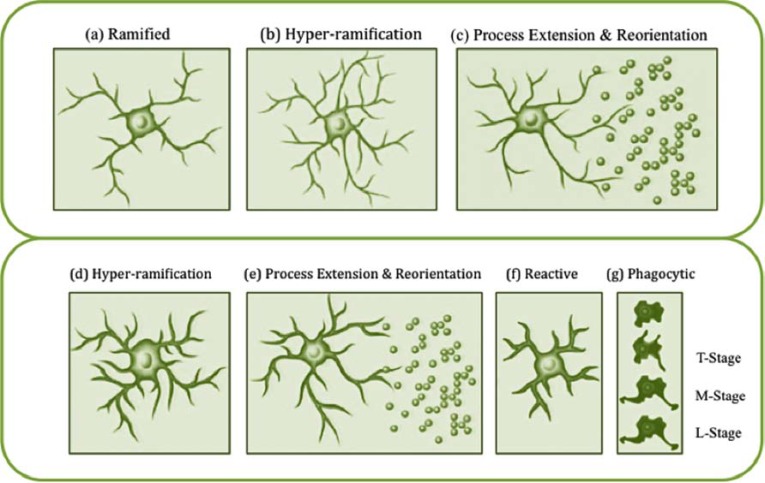

Despite the fact that the term microglial ‘activation’ is widely used in the literature, what is precisely meant by the term varies widely. Historically, the concept of activation referred to the fact that microglial cells had become engaged in some way with a neuroinflammatory response. Typically, ‘activated’ cells were considered to release significant levels of pro-inflammatory molecules, including pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and free radicals such as nitric oxide [26]. Microglia engaged in these responses were also routinely found to exhibit greater expression of molecules such as CD68 (otherwise known as ED1 or macrosialin) [27], which is a low-density lipoprotein associated with microglial phagocytosis, and MHC-II, associated with antigen presentation [28]. In addition to these proteomic changes, the morphology of classically activated microglia is recognised to change substantially. Specifically, microglia involved in inflammatory responses have been noted to often undergo a highly stereotyped morphological transformation in which the fine processes that extend from the cell’s soma partially retract and thicken before fully retracting, leaving the cell with an amoeboid or macrophage-like appearance [29]. Microglial cells in this state are often found to be capable of locomotion and active proliferation. The consistency with which this response has been noted has resulted in morphological change extensively used as a surrogate index of ‘activation’ state (see [30] Fig. 1).

Fig. (1).

Morphological remodelling of microglia in response to pathological (classic) and non-pathological signals. (a) Typically ramified quiescent microglial cell within the grey matter of the adult rat brain. (b) It is thought that morphological alterations in response to nonpathological stimuli (experience-dependent modifications) can be quite diverse. Fontainhas et al. [32] recently described hyper-ramification of microglia after ionotropic glutamatergic neurotransmission led to increased microglial process length and branching. (c) Tremblay et al. [22] have further demonstrated that marked changes in the level of light can induce microglial processes to make more frequent contacts with synapses within the visual cortex, a finding that suggests that hyper-ramified microglia possess the ability to reorientate processes in response to changes in neuronal activity. (d) Morphological alterations in response to injury or inflammation have been extensively described and appear to be highly stereotyped [9, 33-35]. (e) It appears that the initial response of microglia to injury appears to be rapid process extension and reorientation towards the site of injury [20, 21]. (f) Microglia are often reported to enter a reactive phase involving retraction and thickening of processes. (g) Following this, evidence suggests that reactive microglia then transition into phagocytic, amoeboid cells. Stence et al. [36] suggested that this cell type can be further differentiated into transitional (T-stage), motile (M-stage) and locomotor (L-stage) microglia. One open question with respect to changes in microglial morphology in response to injury is the degree to which these signals promote hyperramification. Several groups have previously described hyper-ramification occurring in injury-based models [35, 37] but in one of the only quantitative studies to date, Stence et al. [36] found no evidence of microglial hyper-ramification occurring in response to slice preparation as an injury model. Image adapted from Beynon and Walker [30].

More recently, it has become apparent that microglia undergo significant structural alterations, not only in response to damage but also in response to standard environmental challenges. For instance, Hinwood et al. [6] have recently shown that exposure to chronic psychological stress, in the absence of any evidence of injury or neurodegeneration, increases the extent of secondary branching of microglia within the prefrontal cortex. Consistent findings have also been reported by Tynan et al. [7] and Sugama et al. [31]. Similarly, Fontainhas et al. [32] demonstrated that microglial process motility is significantly increased in response to ionotropic glutamatergic neurotransmission, and Tremblay et al. [22] have shown that light deprivation increases the number of microglial processes making contact with synaptic elements. Together these recent findings have greatly expanded the absolute range over which microglia activation occurs – ranging from mild non-inflammatory linked structural alterations, through to major structural changes that are linked to pro-inflammatory cytokine and free radical production, phagocytosis and apoptosis.

THE EFFECT OF ACUTE AND CHRONIC STRESS EXPOSURE ON MICROGLIA

Modulation of Microglial Function by Acute Stressors

For well over a decade it has been known that acute stress in rats could significantly increase the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines within the brain, most notably interleukin-1β (IL-1β) [38]. While it was recognised at the time that microglia were the most likely cellular source of centrally released pro-inflammatory cytokines, evidence to support this supposition did not emerge for several years (see Table 1). In the first compelling study to link stress-induced release of IL-1β in the brain to microglia, Blandino et al. [39] evaluated the effect of a single exposure to footshock, which had been shown to elicit a marked increased in hypothalamic IL-1β mRNA, in animals also administered minocycline. Minocycline is a second-generation tetracycline derivative that has been extensively used to restrict pro-inflammatory cytokine release from microglia [40]. The results from this study clearly demonstrated that minocycline (40mg/kg) abolished the stress-induced increase IL-1β, thus implicating microglia as the most likely source of production.

Table 1.

Effects of Acute Stress on Microglia

| Acute (1 day or session) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Author | Stressor | Results |

| Blandino et al., 2006 [39] | Footshock, 80 over 2hrs | Stress exposure significantly increased hypothalamic IL-1β relative to non-stressed controls. Minocycline (microglial inhibitor) completely blocked the stress-induced increase in hypothalamic IL-1β suggesting that microglia is a source of central IL-1β in response to stress. |

| Sugama et al., 2007 [31] | Restraint + water immersion, 2hrs | Robust increase in CD-11b (CR3 marker) immunoreactive cells in the thalamus, hypothalamus, hippocampus, substantia nigra and periaqueductal gray (PAG). Significant reduction of stress-induced CD-11b immunoreactivity in IL-18 KO mice. |

| Frank et al., 2007 [45] | Inescapable tail shock | Stress up-regulated MHC-II and down-regulated CD200, which functions to hold microglia in a quiescent state. Stress potentiated the pro-inflammatory response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) ex vivo 24h post-stress in isolated hippocampal microglia. |

| Sugama et al., 2009 [56] | Restraint + water immersion, 2hrs | Acute stress was followed by increased CD11b immunoreactivity proximal to c-fos positive neurons in the PAG. LPS treatment induced CD11b even in the absence of neuronal responses in the PAG as well as in the rest of the midbrain. |

| Blandino et al., 2009 [57] | Footshock, 80 over 2hrs | In the hypothalamus, mRNA for IL-1β and CD14 were significantly increased, CD200R mRNA was significantly decreased. Propranolol (β-AR antagonist) blocked this increase in IL-1β and CD14 mRNA, while the decrease in CD200R was unaffected. Inhibition of glucocorticoid (GC) synthesis increased basal IL-1β mRNA and augmented IL-1 and CD14 expression provoked by stress. Injection of minocycline blocked the IL-1β response to stress, while CD14 and CD200R were unaffected. |

| Frank et al. 2010 [58] | Corticosterone (2.5 mg/kg b.w.) | Prior corticosterone administration in vivo potentiated the increase in microglial IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) in response to LPS ex vivo. |

| Sugama et al., 2013 [55] | Corticosterone | Acute stress induced CD11b immunoreactivity in the hippocampus and hypothalamus; CD11b immunoreactivity was enhanced by adrenalectomy and reduced by corticosterone administration in adrenalectomised animals. |

| Frank et al., 2012 [59] | Inescapable tail-shock | Stress resulted in a potentiated pro-inflammatory cytokine response (IL-1b, IL-6, NFkBIα) to LPS in isolated hippocampal microglia. |

In addition to Blandino et al.’s study, three other notable studies were published in 2006 that described the ability of stress to modulate microglial function. In the first, Shimoda et al. [41] demonstrated that microglia obtained from mice exposed to restraint stress over a three day period produced significantly greater levels of the chemokine CCL2 and had higher levels of Toll-like 2 receptor (TLR2) mRNA expression than control animals. In the second, De Pablos et al. [42] demonstrated that animals exposed to 10 days of variable stress prior to receiving an intra-cortical injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), exhibited significantly greater levels of MHC-II expression, a protein that is expressed predominately on activated microglia. Finally, Nair and Bonneau [43], using a sub-chronic restraint model in mice for six days, examined changes in microglial proliferation using CD11b/CD45 based flow cytometry. Strikingly, the authors observed a three-fold surge in CD11bHI/CD45LO (i.e. microglia) cells at four days following commencement of restraint, but not on days five or six of the intervention. Why the surge present at day four did not persist was not resolved. Despite this, the authors did find that proliferation of CD11bHI/CD45LO cells was mediated by glucocorticoids, as metyraprone, an inhibitor of glucocorticoid synthesis, and RU486, a glucocorticoid receptor antagonist, both limited the observed proliferation. Following these early reports numerous studies have consistently confirmed the ability of both acute and chronic stress to significantly modulate microglial activity (see Tables 1-3).

Table 3.

Effect of Chronic Stress on Microglia

| Chronic (>6) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Author | Stressor | Results |

| Tynan et al., 2010 [7] | Restraint 1h/day for 14 days | Stressed animals showed an increase in Iba-1 immunoreactivity in 9 of 15 stress-responsive forebrain regions. |

| Hinwood et al., 2012 [6] | Restraint 6h/day for 21 days | Stress led to increases in microglial branching, number of processes, process length and convex hull area of microglia in the PFC. Minocycline attenuated these stress-induced effects. |

| Hinwood et al., 2012 | Restraint 6h/day for 21 days | Stressed animals had Iba-1 increases in the prelimbic and infralimbic regions of the mPFC |

| Bian et al., 2012 [51] | Various- chronic unpredictable stress daily for 40 days | Stressed animals had a significantly increased number of Iba1-positive cells in the hippocampus CA3 and prelimbic areas. |

| Bradeshi et al., 2009 [61] | Restraint +water immersion, 1h/day for 10 days | P-p38 (correlated with CD11b immunoreactivity), and CD11b immunoreactivity were increased in stressed rats and these increases were reversed by minocycline. |

| Farooq et al., 2012 [53] | Various- chronic mild stress for 9 weeks | Stress increased CD11b immunoreactivity in the infralimbic, cingulate and medial orbital cortices, nucleus accumbens, caudate putamen, amygdala and hippocampus as a function of unpredictable chronic mild stress. |

| Kopp et al., 2013 [54] | Restraint- 30min/day for 14 days or; Chronic variable stress 2x day for 14 days | Restraint stress led to an increase in Iba-1 immunoreacitivty in the pre-limbic cortex and infralimbic cortices. |

Modulation of Microglial Structure by Acute Stressors

While the work of Blandino et al., and others established that microglial activity could be altered by exposure to stress, the first direct evidence that stress could alter microglial morphology emerged somewhat later. Sugama et al. [31] was the first to identify that microglia from C57B/L6 mice that had been exposed to an acute stressor exhibited significantly higher levels of CD11b (a marker of the C3 complement receptor) immunoreacitivty in the hypothalamus, and hippocampus. The authors further demonstrated that stress resulted in a significant increase in CD11b immunoreactivity for at least 2 hours following termination of the stressor, and that these changes largely resolved within six hours.

Of some interest, given the observations of Blandino et al. [39], Sugama et al. [31] reported that they could not find any significant increase in the expression of IL-1β or interleukin-6 (IL-6) mRNA, nor detect any appreciable increase in MHC-II or CD68 immunoreactivity. These later findings were taken to suggest that the changes in microglial CD11b expression were unlikely to be driven by locally produced inflammatory signalling molecules. Sugama et al. [44] did note, however, that exposure to cold-stress, rather than water immersion, could elicit an increase in CD11b immunoreactivity and an increase in the level of IL-1β. In a follow-up study the authors, using the same experimental approach, established that the CD11b immunoreactivity occurred proximal to c-fos positive neurons (i.e. recently activated neurons) within the periaqueductal gray (PAG). This pattern, however, was not observed for animals peripherally challenged with LPS, with LPS challenged animals displaying a marked change in CD11b but not c-fos immunoreactivity.

ACUTE STRESS-INDUCED PRIMING/ SENSITIZATION OF MICROGLIAL RESPONSES TO IMMUNE STIMULATION

Perhaps one of the most intriguing findings to emerge from research into the effects of acute stress on microglia concerns the ability of a single stressful experience to prime microglia to respond more vigorously to subsequent immune stimulation [45]. Johnson et al. [46] were amongst to first to note that if rats were exposed to a single session of inescapable footshock and subsequently exposed to a LPS challenge, they would produce significantly greater levels of IL-1β within the pituitary, hypothalamus, hippocampus, and cerebellum. Interestingly, Frank et al. [45], using an experimental paradigm closely aligned with that of Johnson et al.’s, could find no clear evidence for a change in IL-1β mRNA expression 24 h after the stress session in-vivo, a finding that is somewhat inconsistent with the earlier work Johnson et al., Blandino et al. and Nair and Bonneau. Despite this, Frank et al. also included an innovative experiment in which microglia from previously stressed animals were isolated using density gradient centrifugation and stimulated the cells ex-vivo with LPS. The results from this experiment clearly indicated that microglia from previously stressed animals produced significantly higher levels of IL-1β mRNA than controls stimulated with LPS.

SUB-CHRONIC AND CHRONIC STRESSORS

In parallel to studies investigating the acute effects of stress on microglia there have now also been several studies charting the effects of sub-chronic (≤ 6 sessions) and chronic stress (>6 sessions) (see Tables 2 & 3). In one of the first studies to examine the effects of chronic stress on microglia, Tynan et al. [7] examined changes in Iba-1 immunoreactivity in 15 nuclei involved in the regulation of stress response and mood state in animals exposed to 14 days of restraint stress (1h/day). The authors of this study found that chronic stress induced a significant increase in the density of Iba-1 immunoreactivity in nine of fifteen regions examined, including the prefrontal cortex (PFC) (see Fig. 2). Like the earlier study of Sugama et al., Tynan et al. could find no clear evidence of inflammatory or neurodegenerative changes.

Table 2.

Effects of Sub Chronic Stress on Microglia

| Sub Chronic (≤6) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Author | Stressor | Results |

| Nair & Bonneau., 2006 [43] | Restraint 15h/day 6 days | Four sessions of stress induced the proliferation of CD11b+/CD45Lo cells (microglia) through corticosterone-induced activation of the NMDA receptor within the CNS. The NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 prevented increases in CD11b+/CD45Lo cells following exogenous corticosterone administration to non-stressed mice. |

| Wohleb et al., 2012 [60] | Repeated social defeat 2h/day for 6 days | Stress significantly increased the number of Iba-1 cells in the hippocampus, PFC and amygdala. |

| Wohleb et al., 2011 [48] | Social defeat 2h/day for 6 days | Stress enhanced reactivity of microglia dependent on activation of β-adrenergic and IL-1 receptors. Stress increased inflammatory markers (CD14, TLR4, and CD86) on the surface of microglia, increased Iba-1 immunoreactivity of microglia in the medial amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus, Stress increased IL-1β and reduced levels of GC responsive genes. Microglia isolated from stressed mice and cultured ex vivo produced markedly higher levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 after stimulation with LPS. |

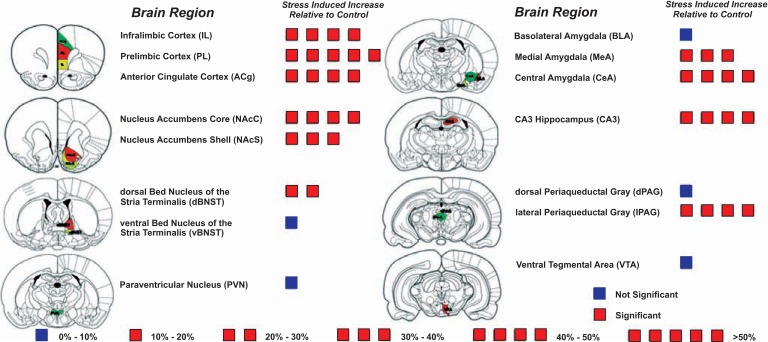

Fig. (2).

Regional specificity of microglial alterations following exposure to chronic restraint stress. The schematic shows the mean percentage difference in Iba1 immunoreactivity in chronically stressed animals relative to handled controls. A single box = 10 % increase from baseline. Red boxes indicate a significant difference and blue boxes indicate a difference that was not statistically significant. – Adapted from [7].

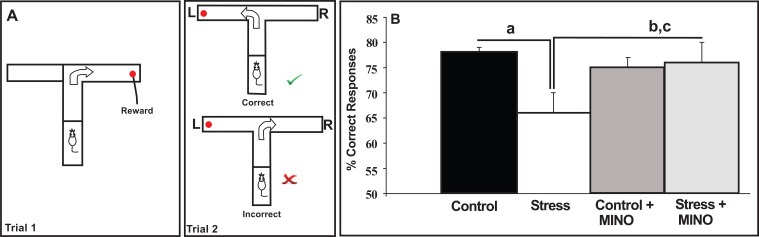

Building on the concept established by Tynan et al., Hinwood et al. [47] subsequently examined the relationship between chronic stress-induced microglial disturbance within the PFC and stress-induced working memory deficits. This relationship was of interest as chronic stress has long been recognised to disturb neuronal connectivity within the PFC, and these structural alterations are recognised to be associated with the emergence of working memory deficits. Accordingly, Hinwood et al. [47] examined the effects of chronic stress in adult rats exposed to chronic restraint stress (6h day/21days) in the presence or absence of minocycline. The authors observed, as expected from the work of Tynan et al., that chronic stress increased the density of Iba-1 immunoreactivity within layers II-VI of ventromedial PFC and that stressor exposure impaired spatial working memory using the delayed alternating T maze (see Fig. 3). The authors further demonstrated that minocycline significantly reduced Iba-1 immunoreactivity and substantially reduced the stress-induced working memory deficit (see Fig. 3). These findings were the first to suggest that microglia may play a role in mediating the deleterious effects of chronic stress on PFC neuronal function in PFC-regulated behaviour in the rat.

Fig. (3).

(A) Delayed alternating T-maze (DAT) assessment of working memory. To receive a food reward, and perform the task correctly in Trial 2 an animal needs to remember where it has been in Trial 1 and travel down the opposite arm. To test working memory, a 30s delay is introduced between the end of Trial 1 and the start of Trial 2. Once trained to do this correctly, animals were subjected to the chronic stress protocol for 3 weeks - but with half of them receiving minocycline in their drinking water. At the end of the protocol they underwent the DAT test again. As seen in (B), chronic stress exposure impaired working memory performance, but this was reversed by minocycline (MINO). a= Control > Stress; b= Control + MINO > Stress and c = Stress + MINO > Stress at p <0.05. Adapted from [47].

In the same year, Wohleb et al. [48] reported similar results in the context of anxiety in mice exposed to six days of social disruption stress. In this study the authors observed that social disruption stress in mice significantly increased Iba-1 immunoreactivity within the medial amygdala, hippocampus, PFC and paraventricular nucleus. Microglia from repeatedly stressed animals exhibited increased levels CD14, CD86 and TLR-4, and when isolated and subsequently stimulated, produced significantly higher levels of IL-1β mRNA. The authors further observed that these changes were associated with significantly higher levels of anxiety-like behaviour, an effect that could be abolished by treating the animals with propranolol, a non-selective β-adrenergic receptor antagonist. Strikingly, the authors noted that propranolol not only reduced anxiety-like behaviour in stressed animals but also reduced the observed increases in Iba-1 immunoreactivity. Together, the findings of Hinwood et al. and Wohleb et al. suggest that stress-induced microglial disturbances may be capable of regulating both complex cognitive functions and emotional states.

UNRAVELLING THE PRECISE EFFECTS OF CHRONIC STRESS ON MICROGLIAL MORPHOLOGY

While the studies of Tynan et al. [7], Hinwood et al. [47] and Wohleb et al. [48] clearly demonstrate the ability of chronic stress to modulate microglial morphology, the analytical approach used in these studies precluded any definitive conclusions being made about exactly how microglial morphology had been changed. To elaborate, all previous studies examining the impact of stress (both acute and chronic) on microglial morphology made use of a technique commonly referred to as image thresholding. The essence of this procedure involves quantifying the overall level of immunoreactive material identified by microglial specific immunolabelling procedures. As a quantitative approach ‘thresholding’ offers several advantages in that it is sensitive to global changes in labelling, it is objective (when imaging and analyses are conducted under identical conditions) and can, in principle, be undertaken in a relatively short period of time. Historically, when a difference (most commonly an increase) in the overall level of thresholded material is observed, it is described as reflecting ‘microglial activation’ [49]. Unfortunately, this term provides very little clarity in terms of characterizing this ‘activation’. Indeed, the term activation could, in most instances, simply be substituted with the term ‘changed’ as it does not (and cannot) reveal what type of microglial transformation has occurred (see also [50]). For instance, it is impossible to know from a global change in the intensity of thresholded material whether the length of microglial processes has increased, whether process length is maintained and a greater number of processes have been added (i.e. become hyper-ramified) or whether the cell has transitioned between a ramified and amoeboid state.

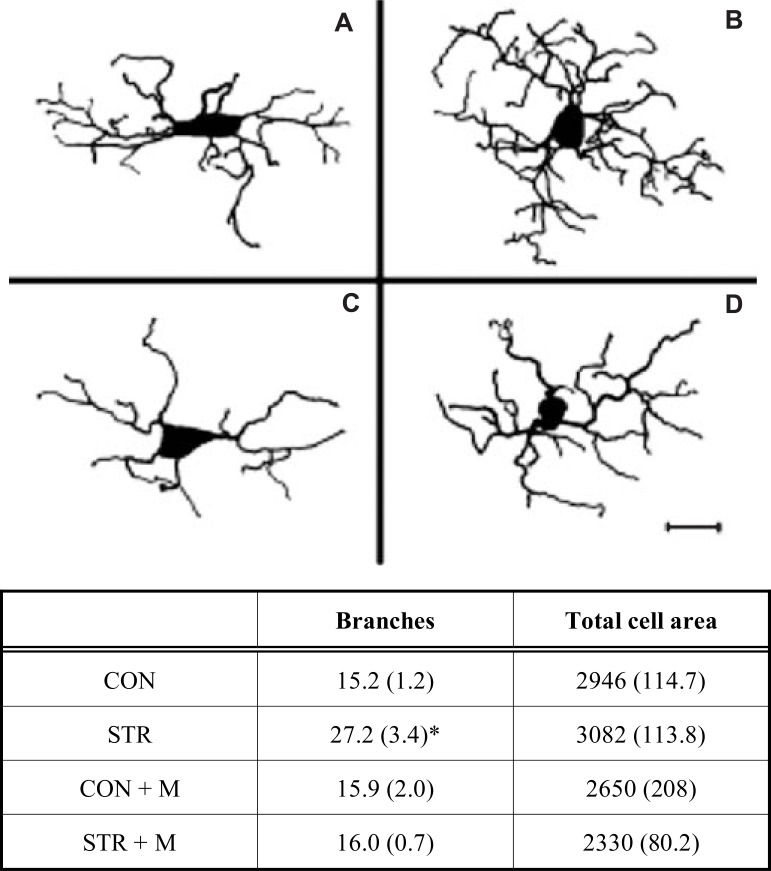

In an effort to address the limitations associated with thresholding-based assessments of microglia, Hinwood et al. [6] undertook a detailed morphological analysis of microglia from animals that had undergone a 21 day restraint stress paradigm. Specifically, in this study the authors created digital reconstructions of microglia cells at high magnification from stress and control animals as well as animals that were exposed to stress and minocycline. The analysis of these reconstructions revealed that restraint stress induced a highly specific form of remodelling involving significant increases in the secondary process branching without increasing the overall area (μm2) occupied by the cell (see Fig. 4). This result suggests that chronic stress does not make microglia larger, as might reasonably be inferred from previous thresholding data, but rather increases the structural complexity of the cell. Hinwood et al. further observed that the stress-induced enhancement in ramification was robustly inhibited in animals also given minocycline (See Fig. 4). With respect to identifying mechanisms that may drive greater ramification in stressed animals, the authors could not find any definitive evidence of increased levels of IL-1β, MHC-II or CD68, again suggesting that neuroinflammatory changes may not be a necessary requirement for changes in microglial morphology.

Fig. (4).

Reconstruction of PFC microglia demonstrating stressinduced remodelling. Microglia reconstructed from (A) control (CON); (B) chronically stressed animals (STR); (C) control animals given minocycline (CON + M); and (D) stress animals given minocycline (STR + M). Key quantitative comparisons between groups are described in the table beneath (mean ± SE). Note that stress alters only branch number and not the total area occupied by the cell (* = STR > all groups, p<0.05). Accordingly, stress increases the overall branching complexity of microglia, and this effect can be significantly attenuated by minocycline. Adapted from [6]. Scale bar = 20 µm

Several additional studies from independent groups (in addition to Tynan et al. [7], Hinwood et al. [6, 47], and Wohleb et al. [48]) have now established the ability of chronic stress to produce marked changes in microglial morphology [51-54]. Most recently, Kopp et al. [54], in a head-to-head comparison of the repeated restraint stress paradigm versus the chronic variable stress (CVS) paradigm, observed that while repeated restraint was capable of eliciting a robust change in microglial morphology, the chronic variable paradigm was not. At first this finding would seem somewhat counter-intuitive given that chronic variable stressors are known to elicit persistently higher levels of corticosterone release [26-28]. In accounting for this finding the authors propose that the higher levels of corticosterone in CVS animals may actually inhibit changes in microglial morphology. This proposal interdigitates perfectly with a recent study by Sugama et al. [55]. In this report the authors examined whether corticosterone exerts a permissive or inhibitory role on microglial morphology. Using changes in CD11b immunoreactivity as the primary index of microglial disturbance, Sugama et al., investigated how adrenalectomy (a procedure that eliminates the animal’s ability to produce corticosterone) influenced microglial alterations in stressed animals. Interestingly, Sugama et al., noted that adrenalectomised (ADX) mice exhibited robust increases in CD11b immunoreactivity, and that this increase was not appreciably different to that seen in intact stressed animals. Sugama et al. further observed that CD11b immunoreactivity remained significantly higher in ADX following stress; an effect that they found could be blocked by administration of exogenous corticosterone. This finding is perhaps the first compelling evidence to suggest that corticosterone does not always function as a primary trigger for stress-induced microglial alterations.

MECHANISMS THROUGH WHICH STRESS ENGAGE MICROGLIA

At present, glucocorticoid and noradrenergic signalling represent the two best-understood pathways through which exposure to stress (both acute and chronic) can influence microglia. The available evidence for each of these mechanisms will be elaborated upon in the following section.

a. Glucocorticoid Dependent Modification of Microglial Structure and Function

Glucocortcoids have featured prominently in research directed at understanding how exposure to stress alters microglia structure and function. This line of research is well justified given the preponderance of evidence demonstrating the ability of stress in rodents to elicit significant increases in circulating corticosterone. The specifics of how stress induces and regulates corticosterone release have been covered in detail in a number of excellent reviews [14, 62, 63]. Importantly, for the present review there is strong in vivo and in vitro pharmacological evidence to suggest that stress-induced increases in corticosterone can exert direct effects on microglia. Central to this evidence, however, has been the discovery that microglia posses both mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors [64]. Indeed in a detailed study of steroid receptors possessed by microglia, Sierra et al. [64] identified in vivo that glucocorticoid receptors are the most abundantly expressed steroid hormone receptor within hippocampal microglia in mice. In vitro studies have also provided evidence for the presence of glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors in microglia in the rat forebrain [65] as have ex vivo studies in the gerbil hippocampus [66]. At present, the available data suggest that glucocorticoids can exert both suppressive and stimulatory effects on microglia, with the direction being determined primarily by the timing and duration of exposure.

Nair and Bonneau [43] were the first to provide evidence indicating that inhibiting the actions of glucocortcoids released in response to stress could modulate microglial activities. Specifically, Nair and Bonneau identified that both RU486 and metyraprone could inhibit stress-induced microglial proliferation. Frank et al. [59] later extended this work by demonstrating that the acute stress-induced increase in pro-inflammatory cytokine release from stimulated microglia could effectively be abolished by adrenalectomising the animals or by administering RU486. In addition to these studies, Woods et al. [67], has demonstrated that dexamethasone administration suppresses CD68 (ED-1) expression in animals subjected to hippocampal de-afferentation; Zhang et al. [68] reported that dexamethasone significantly reduced Iba-1 (AIF-1) expression in animals exposed to a traumatic brain injury; Jacobssen et al. [69] has demonstrated that corticosterone significantly reduces the expression of the excitatory amino acid transporter GLT-1 in microglia obtained from rats; Graber et al. [70] has demonstrated that addition of dexamethasone to microglial cultures significantly reduced LPS stimulated nitric oxide and pro-inflammatory cytokine production; and finally, Hinkerhoe et al. [71] found that the addition of dexamethasone to mixed microglial/astroglial cultures decreased expression of CD68 in LPS stimulated cells.

The ability of glucocorticoids to exaggerate microglial mediated neuroinflammatory responses has also been demonstrated in a number of studies that have examined the impact of stress in disease models (see Table 2). In one of the earliest studies De Pablos et al. [42] demonstrated that animals pre-exposed to nine days of chronic variable stress and then injected intracortically with LPS, exhibited significantly higher levels of MHC-II expression, a maker that is predominantly localised on microglia during neuroinflammatory responses. De Pablos et al. further demonstrated that daily administration of RU486 (20mg/kg) effectively abolished the observed increase in MHC-II expression. Similar findings of stress-induced injury exacerbation were later reported by Alexander et al. [72]. In this study animals were administered spared nerve injury after 60 minutes exposure to restraint stress. Stressed animals exhibited significantly higher levels of Iba-1 expression at one day following injury, and exhibited higher levels of CD11b and TLR4 at three days following injury. Strikingly, the stressed animals exhibited marked allodynia for the following seven days (to the end of the experiment), which could be effectively abolished by administering RU486.

The ability of corticosterone to exert both stimulatory and inhibitory effects on microglia has been elegantly addressed experimentally by Frank et al. [58]. In this study the authors demonstrate that when stress-like levels of corticosterone are delivered prior to a peripheral immune challenge (LPS) the subsequent immune response is potentiated. In contrast, when corticosterone was administered after (1h) the LPS challenge, the pro-inflammatory response was suppressed. These findings highlight that the temporal relationship, at least in acute contexts, between corticosterone elevations and immune challenge is critical in determining whether corticosterone will produce a pro- or anti-inflammatory response. The precise mechanisms that are responsible for these opposing effects have yet to fully resolved. Frank et al., [59] however, in a recent review of the stress-induced enhancement of the microglial inflammatory responses has suggested that there are a number of plausible explanations. For instance, exposure to corticosterone may up-regulate the expression of Toll-like receptors on microglia that allow them to subsequently make a more vigorous response to any encountered immune challenge. Alternatively, initial exposure to corticosterone may desensitize or decrease the number of glucocorticoid receptors so that the glucocorticoid rise that is elicited by LPS stimulation no longer exerts the same suppressive effects.

b. Noradrenergic Dependent Pathways to Modification of Microglial Structure and Function

While it has been recognised for some time now that microglia posses α1A, α2A, β1 and β2 adrenoceptors, [80] the first compelling evidence that these receptors and their ligands could contribute to the stress-induced release of pro-inflammatory cytokines within the brain emerged in 2005 [81]. In this study the authors evaluated whether pre-treating acutely stressed animals with adrenoceptor antagonists, could modulate the subsequent release of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the brain and periphery. In terms of the specific antagonists used, Johnson et al. [81] evaluated the effect of prazosin (alpha1-adrenoceptor antagonist), propranolol (beta-adrenoceptor antagonist) and labetol (α1- and β-adrenoceptor antagonist). The experimental utility of these particular antagonists lies in the fact that prazosin and propranolol both readily cross the blood brain barrier whereas labetol does not. The authors observed that while prazosin had no appreciable influence on the stress-induced increase in hypothalamic IL-1β release, it did significantly lower peripheral levels of IL-1β and IL-6. In contrast, propranolol, while having little effect on peripheral IL-1β and IL-6 levels, completely abolished the hypothalamic increase in IL-1β. Importantly, there was no observable reduction in hypothalamic IL-1β in animals pre-treated with labetol. Together, these findings strongly suggest that activation of the beta-adrenoceptor is one of the primary mechanisms contributing to the stress-induced released of pro-inflammatory cytokines within the brain. Aligning perfectly with these observations, McNamee et al. [82] recently demonstrated that administration of β-adrenoceptor agonists increased IL-1β receptor expression in the brain and, more recently, Johnson et al. [77], using an ex-vivo approach, confirmed that β-adrenoceptor stimulation is sufficient to prime microglial cytokine responses.

Using the work of Johnson et al. [81], as a starting point Blandino et al. [39] hypothesised that microglia were likely to be the principal cell involved in translating stress-induced elevations in central catecholamines into pro-inflammatory signals. To test this hypothesis, Blandino et al., in separate studies, evaluated the ability of propropanol and minocycline to inhibit the stress-induced increase in hypothalamic IL-1β. Consistent with Johnson et al.’s earlier work, Blandino et al. observed that acute stress enhanced hypothalamic IL-1β- an effect that could be blocked with propropanol. The authors also demonstrated that treating the animals with minocycline substantially reduced the levels of IL-1β observed after stress, and in doing so provided an important link between stress-induced neurotransmitter fluctuations and changes in central pro-inflammatory signalling. Somewhat later, Wohleb et al. [48] provided further evidence of the β-adrenoceptor-microglia axis by directly confirming in stressed animals that propranolol inhibited stress-induced changes in microglial morphology, as indexed by Iba-1 immunoreactivity. Of interest Wohleb et al. [48] also provided data indicating that mice in which the IL-1 receptor had been genetically deleted did not exhibit any changes in microglial morphology. This is an intriguing result as there is some evidence to suggest that microglia, at least in culture, do not respond to the presence of IL-1 [83]. As such these findings suggest that the while microglia may produce IL-1β they may need to interact with another, as yet unidentified, cell type that posses functional IL-1 receptors to transform, following stress exposure.

Despite the compelling nature of the existing evidence concerning the ability of β-adrenoceptor activation to initiate pro-inflammatory cytokine production from microglia, several studies have observed evidence to the contrary. As early as 1996, Colton and Chernyshev [84] demonstrated that treatment of microglial cultures with adrenergic agonists such as isoproterenol was capable of limiting superoxide anion production in phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) stimulated cultures. Somewhat later Mori et al. [80] observed that norepinephrine (NE), phenylephrine (an α1 agonist), dobutamine (a β1 agonist) and terbutaline (a β2 agonist), all suppressed the expression of mRNAs encoding IL-6 and TNF-α in LPS stimulated microglial cells. Indeed, these results have subsequently been replicated by at least three other groups in vitro [85-87] and at least once in vivo [88] (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Norepinephrine Influence on Stress-Induced Microglial Alterations

| Author | NE Stimulation |

|---|---|

| Results | |

| Blandino et al., 2006 [39] | Propranolol blocked, and desipramine (NE reuptake inhibitor) augmented, the IL-1β response to stress in the hypothalamus. Minocycline reversed the stress-induced increase in hypothalamic IL-1β suggesting that norepinephrine (NE) modulates the hypothalamic IL-1β response to stress, and that microglia may be a source of central IL-1β in response to stress. |

| Wohleb et al., 2011 [48] | Stress led to an increase in inflammatory markers on the surface of microglia (CD14, CD86, and TLR4) and Iba-1 immunoreactivity of in the medial amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus. The stress-dependent changes in microglia were prevented by propranolol. |

| Johnson et al. 2013 [77] | Isoproterenol (β-AR agonist) significantly enhanced IL-1β and IL-6 production in hippocampal microglia following LPS stimulation suggesting that central β-AR stimulation primes microglia cytokine responses. |

| NE Inhibition | |

| Colton et al., 1996 [84] | Acute and chronic exposure of cultured microglia to adrenergic agonists and GCs resulted in a down-regulation of microglial function (measured as superoxide anion production). |

| Mori et al., 2002 [80] | NE and terbutaline (β2 agonist) elevated intracellular cAMP level of microglial cells. NE, phenylephrine (α1 agonist), dobutamine (β1 agonist) and terbutaline suppressed the expressions of mRNAs encoding IL-6 and TNF-α. Release of TNF-α and NO was suppressed by NE, phenylephrine, dobutamine and terbutaline. Clonidine (α2 agonist) and dobutamine upregulated the expression of mRNA encoding catechol-O-methyl transferase, which degrades NE. NE, dobutamine and terbutaline up-regulated the expressions of mRNA encoding 3-phospshoglycerate dehydrogenase, an essential enzyme for synthesis of l- serine, and glycine, necessary for neuronal survival. |

| Dello Russo et al., 2004 [85] | NE and isoproterenol reduced microglial NOS2 expression and IL-1β production following LPS stimulation. These effects were reversed by propranolol or a selective β2-AR anagonist (ICI-118,55). |

| Farber et al., 2005 [86] | NE attenuated the LPS-induced release of TNF-α, IL-6 and NO by microglia. |

| O’Sullivan et al., 2009 [88] | NE reuptake inhibitors desipramine and atomoxetine reduced cortical gene expression IL-1β and TNF-α, the enzyme inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), CD11b and CD40 following LPS stimulation. |

| Tynan et al., 2012 [87] | NE potently inhibited LPS stimulated microglial. TNF-α and NO production. Propranolol attenuated the anti-inflammatory effect of NE. |

From the available evidence it appears that one of the major determinants of whether β-adrenoceptor activation exerts a stimulatory or inhibitory effect on microglial pro-inflammatory cytokine production in the brain is the timing of stimulation. This may help to explain the efficacy of NE reuptake inhibitors such as desipramine, reboxetine and venlafaxine as antidepressant agents, which have been reported to exert anti-inflammatory effects on microglia despite the suggestion that β-adrenoceptor stimulation acts to prime microglial cytokine responses [78, 89-91]. In the vast majority of microglial priming studies the initial noradrenergic signal (stress) is delivered prior to immune stimulation (e.g. LPS), with a delay of at least 24h. In contrast, those studies demonstrating the ability of adrenergic stimulation to inhibit pro-inflammatory responses typically involve the noradrenergic signal being delivered concomitantly with immune stimulation (e.g. LPS). The difference in the temporal patterning appears to have major implications for the downstream signalling mechanisms engaged. To elaborate, Tan et al. [92] has demonstrated that β-adrenoceptor stimulation in the absence of pro-inflammatory stimuli produced an 80 and 8-fold increase in IL-1β and IL-6 mRNA respectively in murine macrophages. The authors additionally observed that the increased production of pro-inflammatory transcripts was due, in part, to a PKA-independent increase in intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). Tan et al. finally demonstrated that the pro-inflammatory response was mediated primarily through ERK1/2 and p38 dependent activation of ATF-1 and ATF-2 transcription factors. In contrast, pro-inflammatory cytokine production elicited using LPS stimulation, involves activation of TLR4 that, through its actions of NF-κB, initiates the transcription of pro-inflammatory genes (e.g IL-1β). The point that is critical to understanding how β-adrenoceptor stimulation concomitant with LPS stimulation interferes with cytokine release is that the β-adrenoceptor rise in intracellular cAMP triggers multiple signalling pathways. Specifically, β-adrenoceptor stimulation increases cAMP and this can drive both PKA independent and dependent signalling processes. While PKA-independent signalling is associated with pro-inflammatory cytokine release, cAMP mediated PKA-dependent signalling can interfere with TLR-4/NF-κB signalling cascade and ultimately inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokine release [93].

SUMMARY AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

On the basis of the evidence obtained from pre-clinical experimental studies there appears to be little doubt that exposure to both acute and chronic stressors can modulate microglial structure and function. At present it is not entirely clear what the ‘primary’ molecular signals for these changes are. One obvious candidate would be stress-induced pro-inflammatory cytokines. Several studies have provided clear evidence that acute and sub-chronic stressors can elicit substantial microglial-mediated increases in pro-inflammatory cytokine production. Despite these findings several other studies have reported the ability of stress to produce marked morphological changes in the absence of any detectable disturbance in pro-inflammatory signalling. Other strong signalling candidates for driving microglial alterations are the traditional stress-linked signals, namely corticosterone and norepinephrine. Each of these molecules appears to be capable of exerting both inhibitory and stimulatory effects on microglia, with the specific direction apparently dependent upon the duration and intensity of their release. Another critical factor also appears to be whether exposure to stress co-occurs with the presentation of an inflammatory stimulus. Under these circumstances stress-induced corticosterone and norepinephrine appear to be stimulatory if delivered prior to the inflammatory stimulus and inhibitory if administered at the same time or after the stimulus.

Despite the substantial advances that have been made in relation to understanding the ability of stress to modulate microglia, there are numerous questions that remain completely open. Foremost amongst these, is how does stress alter the dynamic bi-directional signalling between astrocytes on microglia? Recent evidence has indicated that not only can astrocyte-released signals inhibit microglial generated inflammatory responses, but that microglia can reciprocate in kind with an ability to protect astrocytes against the harmful effects of oxidative stress [94, 95]. Whether exposure to chronic stress directly disrupts these mutually beneficial interactions remains to be determined. Given, however, that the impact of stress on astrocyte structure and function is at least as great as is it is for microglia [96, 97], a disruption in the normal bi-directional signalling would seem highly probable.

A second issue of considerable interest is the potential relationship between microglia and neurogenesis. Decreased hippocampal neurogenesis, as a result of exposure to chronic stress, has frequently been suggested to play an important role in the emergence and maintenance of mood related pathology. While several mechanisms have been suggested, the involvement of microglia has not yet widely being considered as a potential contributor. Research from outside the field, however, has shown that microglia can modulate proliferation, survival, migration and differentiation of neural progenitor cells (NPCs) within the hippocampus [98-100].

Finally, one of the most important questions for future research is the extent to which modifying microglial function can exert antidepressant activities. Certainly, it has already been shown that inhibiting stress-induced disturbances of microglia improves executive function and reduces anxiety in rodents [47, 48]. These results certainly point to the therapeutic potential of microglial modulation. An intriguing adjunct to this line of reasoning is evidence demonstrating that traditional selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been shown to moderately curb the release of pro-inflammatory molecules from inflamed microglia [87] and that the typical timeframe to the onset of therapeutic action for SSRIs (3-5wks) corresponds closely to the time taken for the levels in the brain to reach the concentration at which they can inhibit inflamed microglia [101, 102].

Over the last five years there is been an enormous growth in our understanding of how stressed perturbs microglia. It is now clear that both acute and chronic stress can produce substantial changes in microglial phenotype and function. Moreover, critical studies have now demonstrated that microglia are meaningfully involved in cognition and emotional regulation. Together, these facts highlight the potential relevance of microglia to stress-linked psychopathology, and suggest a completely novel way forward in the development of future therapeutics.

Table 4.

Stress Models of Disease State

| Author | Disease State | Stressor | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| De Pablos et al. 2006 [42] | PFC inflammation | Various- chronic stress for 9 days | LPS injection in the PFC produced increased CD74 immunoreactivity and TNF-α in stressed animals. These effects were reversed by RU486 (a GC receptor antagonist). |

| Shimoda et al., 2006 [41] | Cerebral cryptococcosis | Restraint 16hr/day for 3 days | Resistance of stressed mice exposed to cerebral cryptococcosis was diminished by CCL-2 produced by microglial cells. |

| Alexander et al. 2009 [72] | Spared nerve injury | Restraint, 60 mins | Stressed animals exhibited significantly higher levels of Iba-1 expression at one day post injury, and higher levels of CD11b and the TLR4 at 3 days following injury. Stressed animals exhibited marked allodynia for the following seven days, which could be effectively abolished by RU486. |

| Yoo et al. 2011 [73] |

Cerebral ischaemia | Restraint 5hr/day 21 days | Iba-1-immunoreactive microglia were detected in resting form in the CA1 region in shams. From 12 h after ischemia/ reperfusion, Iba-1 immunoreactivity was increased in the CA1 region, microglia were hypertrophied, and many activated microglia were gathered in the stratum pyramidale of the CA1 region. In the stressed-sham group, Iba-1 immunoreactivity in the CA1 region was higher than that in the sham group. In all the stressed-ischemia groups, intensity of Iba-1 immunoreactivity was not changed in the CA1 region, however, microglia were activated. |

| Giovanoli, S. et al. 2013 [74] | Psychiatric disorder | Peri-pubertal variable sub-chronic stress protocol, five distinct stressors applied on alternate days starting from PND 30. | Combined immune activation and stress led to a 2.5-3-fold increase in hippocampal and prefrontal expression of CD68 and CD11b at post-natal day 41. The hippocampal microglia response was accompanied by the presence of elevated levels of IL-1β and TNF-α. Exposure to an acute stressor was sufficient to severely impair hippocampal and prefrontal expression of CD200, CD200R, and CD47 specifically in prenatally immune-challenged animals. |

Table 5.

Glucocorticoid Influence on Stress-Induced Microglial Alterations

| GC Enhancement | |

|---|---|

| Author | Results |

| Espinosa-Oliva et al., 2011 [75] | In stressed rats, CD74 immunoreactivity was dramatically increased following LPS injection. Treatment with RU486 significantly protected animals against the deleterious effects observed in LPS-stressed animals. |

| Frank et al., 2010 [58] | Corticosterone (delivered to simulate stress) potentiated central (hippocampus) pro-inflammatory response (TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6) to prior (2h) LPS exposure. Prior exposure (24 h) to GCs also potentiated the pro-inflammatory response of hippocampal microglia to LPS ex vivo. When GCs were administered after a peripheral immune challenge, GCs suppressed the pro-inflammatory response (TNFα and IL-1β) to LPS. Corticosterone reduced TLR2 3 h post, but increased TLR2 6 and 28 h post. LPS decreased hippocampal TLR4, but CORT 24 h before LPS increased TLR4 mRNA. |

| Frank et al., 2012 [59] | Stress exposure resulted in a potentiated pro-inflammatory cytokine response (IL-1β, IL-6, NFkBIα) to LPS in isolated microglia. Treatment in vivo with RU486 and adrenalectomy (ADX) inhibited or completely blocked this stress-induced sensitization of the microglial pro-inflammatory response. |

| Wohleb et al., 2012 [60] | Peripheral LPS caused an extended sickness response and amplified mRNA expression of IL-1β, TNF-α, iNOS, and CD14 in enriched CD11b+ cells isolated from stressed mice. IL-1β mRNA levels in enriched CD11b+ cells remained elevated in stressed mice 24 h and 72 h after LPS. Microglia and CNS macrophages isolated from stressed mice had the highest CD14 expression after LPS injection. Both stress and LPS increased the percentage of CD11b+/CD45high macrophages in the brain and the number of inflammatory macrophages (CD11b+/CD45high/CCR2+) was highest in stress-LPS mice. |

| Frank et al., 2013 [76] | Blocking TLR 2 & 4 signalling during a stressor prevents stress-induced priming of neuroinflammatory responses to a subsequent immune LPS challenge. |

| Johnson et al., 2013 [77] | β-AR (beta-adrenergic receptor) agonist administration significantly enhanced hippocampal IL-1β and IL-6, but not TNF-α production following LPS stimulation. |

| Johnson et al., 2012 [78] | Repeated stressor exposure regionally enhanced β-AR receptor-mediated brain IL-1β production. |

| GC Inhibition | |

| Chao et al., 1992 [79] | TNF-α and IL-6 release from microglia was inhibited by dexamethasone (synthetic GC). |

| Jacobsson et al., 2006 [69] | LPS-stimulated microglial TNF-α release and glutamate uptake of microglia were inhibited by corticosterone. This inhibition was reversed by mifepristone (GC receptor antagonist). |

| Tanaka et al., 1997 [65] | GC receptor and mineralocorticoid receptor mediated opposing effects of corticosterone on the functions of microglial cells; acting as an inhibitor through GC receptors and a stimulator through mineralocorticoid receptors. |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank Professors John Johnson (Kent State University) and Jonathon Godbout (Ohio State University) for their useful comments in regard to the content of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McEwen BS. The neurobiology of stress: from serendipity to clinical relevance. Brain Res. 2000;886(1-2 ):172–89. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02950-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winsky-Sommerer R, Yamanaka A, Diano S, et al. Interaction between the Corticotropin-Releasing Factor System and Hypocretins (Orexins): A Novel Circuit Mediating Stress Response. J Neurosci. 2004;24(50 ):11439–48. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3459-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vyas A, Mitra R, Rao BS, Chattarji S. Chronic stress induces contrasting patterns of dendritic remodeling in hippocampal and amygdaloid neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22(15 ):6810–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06810.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shansky RM, Morrison JH. Stress-induced dendritic remodeling in the medial prefrontal cortex: Effects of circuit. hormones and rest. Brain Res. 2009;1293:108–13. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.03.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hinwood M, Tynan RJ, Charnley JL, Beynon SB, Day TA, Walker FR. Chronic Stress Induced Remodeling of the Prefrontal Cortex: Structural Re-Organization of Microglia and the Inhibitory Effect of Minocycline. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23(8 ):1784–97. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tynan RJ, Naicker S, Hinwood M, et al. Chronic stress alters the density and morphology of microglia in a subset of stress-responsive brain regions. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24(7 ):1058–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jauregui-Huerta F, Ruvalcaba-Delgadillo Y, Gonzalez-Castañeda R, Garcia-Estrada J, Gonzalez-Perez O, Luquin S. Responses of glial cells to stress and glucocorticoids. Curr Immunol Rev. 2010;6(3 ):195. doi: 10.2174/157339510791823790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graeber M, Streit W. Microglia: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119(1 ):89–105. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0622-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wake H, Moorhouse AJ, Jinno S, Kohsaka S, Nabekura J. Resting microglia directly monitor the functional state of synapses in vivo and determine the fate of ischemic terminals. J Neurosci. 2009;29(13 ):3974–80. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4363-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Day TA. Defining stress as a prelude to mapping its neurocircuitry: no help from allostasis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29(8 ):1195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koolhaas JM, Bartolomucci A, Buwalda B, et al. Stress revisited: a critical evaluation of the stress concept. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35(5 ):1291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Day TA, Walker FR, et al. More appraisal please: a commentary on Pfaff et al.(2007) "Relations between mechanisms of CNS arousal and mechanisms of stress". Stress. 2007;10(4 ):311–3. doi: 10.1080/10253890701638204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ulrich-Lai YM, Herman JP. Neural regulation of endocrine and autonomic stress responses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(6):397–409. doi: 10.1038/nrn2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walker F, Nalivaiko E, Day TA. Stress an Inflammation: An Emerging Story. Nutrition & Physical Activity in Inflammatory Diseases. Cab International. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Checkley S. The neuroendocrinology of depression and chronic stress. Br Med Bull. 1996;52(3 ):597–617. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tremblay M- , Stevens B, Sierra A, et al. The Role of Microglia in the Healthy Brain. J Neurosci. 2011;31(45):16064–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4158-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawson LJ, Perry VH, Dri P, Gordon S. Heterogeneity in the distribution and morphology of microglia in the normal adult mouse brain. Neuroscience. 1990;39(1):151–70. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90229-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mittelbronn M, Dietz K, Schluesener H, Meyermann R. Local distribution of microglia in the normal adult human central nervous system differs by up to one order of magnitude. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2001;101(3):249–55. doi: 10.1007/s004010000284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nimmerjahn A, Kirchhoff F, Helmchen F. Resting microglial cells are highly dynamic surveillants of brain parenchyma in vivo. Science. 2005;308(5726):1314–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1110647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davalos D, Grutzendler J, Yang G, et al. ATP mediates rapid microglial response to local brain injury in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(6):752–8. doi: 10.1038/nn1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tremblay M- , Lowery RL, Majewska AK. Microglial Interactions with Synapses Are Modulated by Visual Experience. PLoS Biol. 2010;8(11):e1000527. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imamura K, Hishikawa N, Sawada M, et al. Distribution of major histocompatibility complex class II-positive microglia and cytokine profile of Parkinson's disease brains. Acta neuropathologica. 2003;106(6):518–26. doi: 10.1007/s00401-003-0766-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kreutzberg GW. Microglia: a sensor for pathological events in the CNS. Trends in Neurosciences. 1996;19(8):312–8. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)10049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Streit WJ, Mrak RE, Griffin WST. Microglia and neuroinflammation: A pathological perspective. J Neuroinflammation. 2004;1:14. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu B, Hong J-S. Role of Microglia in Inflammation-Mediated Neurodegenerative Diseases: Mechanisms and Strategies for Therapeutic Intervention. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304(1):1–7. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.035048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holness CL, Simmons DL. Molecular cloning of CD68. a human macrophage marker related to lysosomal glycoproteins. Blood. 1993;81(6):1607–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Streit WJ, Graeber MB, Kreutzberg GW. Peripheral nerve lesion produces increased levels of major histocompatibility complex antigens in the central nervous system. J Neuroimmunol. 1989;21(2):117–23. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(89)90167-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stence N, Waite M, Dailey ME. Dynamics of microglial activation: A confocal time-lapse analysis in hippocampal slices. Glia. 2001;33(3):256–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beynon SB, Walker FR. Microglial activation in the injured and healthy brain: What are we really talking about?.Practical and theoretical issues associated with the measurement of changes in microglial morphology. Neuroscience. 2012;225:162–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sugama S, Fujita M, Hashimoto M, Conti B. Stress induced morphological microglial activation in the rodent brain: involvement of interleukin-18. Neuroscience. 2007;146(3):1388–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fontainhas AM, Wang M, Liang KJ, et al. Microglial Morphology and Dynamic Behavior Is Regulated by Ionotropic Glutamatergic and GABAergic Neurotransmission. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(1):e15973. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davis EJ, Foster TD, Thomas WE. Cellular forms and functions of brain microglia. Brain Res Bull. 1994;34(1):73–8. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kettenmann H, Hanisch U-K, Noda M, Verkhratsky A. Physiology of Microglia. Physiol Rev. 2011;91(2):461–553. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Streit WJ, Walter SA, Pennell NA. Reactive microgliosis. Prog Neurobiol. 1999;57(6):563–81. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stence N, Waite M, Dailey ME. Dynamics of microglial activation: A confocal time-lapse analysis in hippocampal slices. Glia. 2001;33(3):256–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson MA, Molliver ME. Microglial response to degeneration of serotonergic axon terminals. Glia. 1994;11(1):18–34. doi: 10.1002/glia.440110105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Connor KA, Hansen MK, RachalPugh C, et al. Further characterization of high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) as a proinflammatory cytokine central nervous system effects. Cytokine. 2003;24(6):254–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blandino JrP, Barnum CJ, Deak T. The involvement of norepinephrine and microglia in hypothalamic and splenic IL-1ß responses to stress. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;173(1):87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tikka T, Fiebich BL, Goldsteins G, Keinänen R, Koistinaho J. Minocycline a Tetracycline Derivative Is Neuroprotective against Excitotoxicity by Inhibiting Activation and Proliferation of Microglia. J Neurosci. 2001;21(8):2580–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-08-02580.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shimoda M, Jones VC, Kobayashi M, Suzuki F. Microglial cells from psychologically stressed mice as an accelerator of cerebral cryptococcosis. Immunol Cell Biol. 2006;84(6):551–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2006.01466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DePablos R, Villaran R, Argüelles S, et al. Stress increases vulnerability to inflammation in the rat prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2006;26(21):5709–19. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0802-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nair A, Bonneau RH. Stress-induced elevation of glucocorticoids increases microglia proliferation through NMDA receptor activation. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;171(1):72–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sugama S, Takenouchi T, Fujita M, Kitani H, Hashimoto M. Cold stress induced morphological microglial activation and increased IL-1ß expression in astroglial cells in rat brain. J Neuroimmunol. 2011;233(1):29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frank MG, Baratta MV, Sprunger DB, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Microglia serve as a neuroimmune substrate for stress-induced potentiation of CNS pro-inflammatory cytokine responses. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21(1):47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson JD, O'Connor KA, Deak T, et al. Prior stressor exposure sensitizes LPS-induced cytokine production. Brain Behav Immun. 2002;16(4):461–76. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2001.0638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hinwood M, Morandini J, Day TA, Walker FR. Evidence that Microglia Mediate the Neurobiological Effects of Chronic Psychological Stress on the Medial Prefrontal Cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2012;22(6):1442–54. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wohleb ES, Hanke ML, Corona AW, et al. ß-Adrenergic receptor antagonism prevents anxiety-like behavior and microglial reactivity induced by repeated social defeat. J Neurosci. 2011;31(17):6277–88. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0450-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burguillos MA, Deierborg T, Kavanagh E, et al. Caspase signalling controls microglia activation and neurotoxicity. Nature. 2011;472(7343):319–24. doi: 10.1038/nature09788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beynon SB, Walker FR. Microglial activation in the injured and healthy brain: what are we really talking about?.Practical and theoretical issues associated with the measurement of changes in microglial morphology. Neuroscience. 2012;00:0. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bian Y, Pan Z, Hou Z, et al. Learning. meory.and glial cell changes following recovery from chronic unpredictable stress. Brain Res Bull. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Couch Y, Anthony DC, Dolgov O, et al. Microglial activation. increased TNF and SERT expression in the prefrontal cortex define stress-altered behaviour in mice susceptible to anhedonia. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;29:136–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Farooq RK, Isingrini E, Tanti A, et al. Is unpredictable chronic mild stress (UCMS) a reliable model to study depression-induced neuroinflammation?. Behav Brain Res. 2012;00:0. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kopp BL, Wick D, Herman JP. Differential Effects of Homotypic vs.Heterotypic Chronic Stress Regimens on Microglial Activation in the Prefrontal Cortex. Physiol Behav. 2013;00:0. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sugama S, Takenouchi T, Fujita M, et al. Corticosteroids limit microglial activation occurring during acute stress. Neuroscience. 2013;232:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sugama S, Takenouchi T, Fujita M, Conti B, Hashimoto M. Differential microglial activation between acute stress and lipopolysaccharide treatment. J Neuroimmunol. 2009;207(1 ):24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blandino JrP, Barnum CJ, Solomon LG, et al. Gene expression changes in the hypothalamus provide evidence for regionally-selective changes in IL-1 and microglial markers after acute stress. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23(7 ):958–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Frank MG, Miguel ZD, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Prior exposure to glucocorticoids sensitizes the neuroinflammatory and peripheral inflammatory responses to E.coli lipopolysaccharide. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24(1 ):19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frank MG, Thompson BM, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Glucocorticoids mediate stress-induced priming of microglial pro-inflammatory responses. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26(2 ):337–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wohleb ES, Fenn AM, Pacenta AM, et al. Peripheral innate immune challenge exaggerated microglia activation increased the number of inflammatory CNS macrophages and prolonged social withdrawal in socially defeated mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(9 ):1491–505. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bradesi S, Svensson CI, Steinauer J, et al. Role of spinal microglia in visceral hyperalgesia and NK1R up-regulation in a rat model of chronic stress. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(4 ):1339–48. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Herman JP, Cullinan WE. Neurocircuitry of stress central control of the hypothalamo pituitary adrenocortical axis. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20(2 ):78–84. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Herman JP, Ostrander MM, Mueller NK, Figueiredo H. Limbic system mechanisms of stress regulation: hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29(8 ):1201–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sierra A, Blackmore A, Milner TA, McEwen BS, Bulloch K. Gottfried- Steroid hormone receptor expression and function in microglia. Glia. 2008;56(6 ):659–74. doi: 10.1002/glia.20644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tanaka J, Fujita H, Matsuda S, et al. Glucocorticoid-and mineralocorticoid receptors in microglial cells: The two receptors mediate differential effects of corticosteroids. Glia. 1997;20(1 ):23–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hwang IK, Yoo K-Y, Nam YS, et al. Mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptor expressions in astrocytes and microglia in the gerbil hippocampal CA1 region after ischemic insult. Neurosci Res. 2006;54(4 ):319–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Woods A, Poulsen F, Gall C. Dexamethasone selectively suppresses microglial trophic responses to hippocampal deafferentation. Neuroscience. 1999;91(4 ):1277–89. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00685-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang Z, Zhang Z, Artelt M, Burnet M, Schluesener HJ. Dexamethasone attenuates early expression of three molecules associated with microglia/macrophages activation following rat traumatic brain injury. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;113(6 ):675–82. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jacobsson J, Persson M, Hansson E, Rönnbäck L. Corticosterone inhibits expression of the microglial glutamate transporter GLT-1 in vitro. Neuroscience. 2006;139(2 ):475–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Graber DJ, Hickey WF, Stommel EW, Harris BT. Anti-inflammatory efficacy of dexamethasone and Nrf2 activators in the CNS using brain slices as a model of acute injury. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2012;7(1 ):266–78. doi: 10.1007/s11481-011-9338-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hinkerohe D, Smikalla D, Schoebel A, et al. Dexamethasone prevents LPS-induced microglial activation and astroglial impairment in an experimental bacterial meningitis co-culture model. Brain Res. 2010;1329:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alexander JK, DeVries AC, Kigerl KA, Dahlman JM, Popovich PG. Stress exacerbates neuropathic pain via glucocorticoid and NMDA receptor activation. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23(6 ):851–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]