Abstract

Cytosolic DNA sensing via the STING adaptor incites autoimmunity by inducing type I IFN (IFNαβ). Here we show that DNA is also sensed via STING to suppress immunity by inducing indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase (IDO). STING gene ablation abolished IFNαβ and IDO induction by dendritic cells (DCs) after DNA nanoparticle (DNP) treatment. Marginal zone macrophages, some DCs and myeloid cells ingested DNPs but CD11b+ DCs were the only cells to express IFNβ, while CD11b+ non-DCs were major IL-1β producers. STING ablation also abolished DNP-induced regulatory responses by DCs and regulatory T cells (Tregs), and hallmark regulatory responses to apoptotic cells were also abrogated. Moreover, systemic cyclic diguanylate monophosphate (c-diGMP) treatment to activate STING induced selective IFNβ expression by CD11b+ DCs and suppressed Th1 responses to immunization. Thus, previously unrecognized functional diversity amongst physiologic innate immune cells regarding DNA sensing via STING is pivotal in driving immune responses to DNA.

Introduction

Innate immune cells sense pathogen-specific molecules and rapid production of IFNαβ is a common host signature of microbial sensing. Pathogen DNA is sensed by TLR9 in endosomes and by cytosolic sensors, including DAI, IFI16/P202, DDX41 and cyclic-GMP-AMP synthase (1–5). Cytosolic DNA sensors activate the STimulator of INterferon Genes (STING) adaptor to induce IFNαβ (6). Mice lacking the DNA nucleases Trex-1 or DNaseII developed lethal hyper-inflammatory and autoimmune syndromes due to sustained DNA sensing via STING that incited constitutive IFNαβ expression (7, 8). These findings revealed a critical need to regulate DNA sensing in the absence of infection, and suggested that defective cellular DNA processing at sites of infection, inflammation or tissue remodeling where cells die may lower self-tolerance thresholds due to sustained STING activation driving constitutive IFNαβ production.

Previously, we reported that nanoparticle cargo DNA was sensed in murine lymphoid tissues to induce IFNαβ, which stimulated IDO enzyme activity in DCs to activate Tregs, suppress T cell responses and protect mice from antigen-induced arthritis, though cargo DNA sensing to induce IDO was not TLR9 dependent (9). Here we show that nanoparticle cargo DNA is sensed selectively by myeloid DCs via the STING-IFNαβ pathway to induce IDO in DCs, which activate Tregs to promote dominant T cell regulation.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Mice were bred under SPF conditions and procedures were approved by the IACUC at GRU. IFNAR-KO, STING-KO, CD11cDTR and CD169DTR transgenic mice were described (10–12). To deplete DCs or MZ MΦs CD11cDTR or CD169DTR mice (respectively) were treated with DT (i/p, 10µg/kg) 24hrs. and 6hrs. before DNP treatment as described (12, 13).

DNPs and c-diGMP

DNPs were prepared by mixing polyethylenimine (PEI) or rhodamine-conjugated PEI (VWR, Suwanee, GA) with CpGfree pGiant (Invivogen, San Diego, CA) (9). Mice were injected (i/v) with 30µg pDNA (N:P=10:1) or c-diGMP. YoYo-1 labeled DNA (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was prepared by adding equal volumes of DNA and YoYo-1 in saline and vortexing. The ratio of YoYo-1 to deoxynucleotide pairs was 1:200; for 30µg DNA, 2.2 µl 100 µM YoYo-1 was used.

Immunofluorescence

Fixed frozen sections (7µm) were incubated with CD11c (N418), CD11b (M1–70) (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) and Dylight-488-conjugated goat-anti-hamster or goat anti-rat Abs (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) as described (9).

Cytokines

IFNαβ bioactivity was assessed using a viral interference assay as described (9). Spleen IL-1β was measured by ELISA (eBioscience, San Diego, CA).

IDO enzyme activity

Cell-free spleen homogenates were added to IDO enzyme cocktails and kynurenine generated (after 2hrs) was measured by HPLC as described (14).

Flow cytometry

Spleen cells were stained with CD11c and CD11b mAbs (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) and sorted using a Mo-Flo cell sorter into RNA protection reagent (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA). For analysis, spleen cells were incubated with mAbs and analyzed on a LSRII cytometer (BD). Data were analyzed using FACS DIVA (BD Bioscience) or FlowJo (Tree Star, Ashland, OR) software. mAbs were from eBioscience or BioLegend.

DC and Treg suppression assays

Assays were performed as described (15, 16). In brief, MACS-enriched splenic DCs (or Tregs) were cultured with responder OT-1 T cells and OVA peptide (or responder A1 T cells, APCs and H-Y peptide) for 72 hours and [3H]-thymidine incorporation was measured. 1MT (100µM) was added to parallel DC cultures to block IDO-mediated suppression.

In vivo T cell suppression assays

B6 mice harboring marked (Thy1.1) OVA-specific OT-2 T cells (i/v) were immunized with Act-mOVA splenocytes (106/mouse, i/v or s/c) and OT-2 expansion and Th1 differentiation (intracellular IFNγ) was assessed after 120hrs in spleen or inguinal lymph nodes, respectively (9). c-diGMP was administered (100µg, i/v) 6hr before and 48hr after OVA immunization.

qRT-PCR

RNA was purified using HP total RNA kits (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA), reverse-transcribed using a random hexamer cDNA RT kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA), and qRT-PCR was performed using a iQ5 system and SsoFast Evagreen supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Primers for murine β-actin were (forward) TACGGATGTCAACGTCACAC, (reverse) AAGAGCTATGAGCTGCCTGA. Validated qPCR primer sets for IFNβ1 and IL-1β were purchased (realtimeprimers.com and Qiagen, Germantown, MD). Threshold cycle (Ct) values were set in the early linear phase of amplification; relevant expression was calculated as 2Ct(β-actin)−Ct(target gene).

Statistical analysis

The unpaired Student’s t test (Graphpad Prism) was used for statistical analyses.

Results and Discussion

DCs sense nanoparticle cargo DNA via STING

Treatment (i/v) with DNPs containing PEI and plasmid DNA lacking TLR9 ligands (CpGfree pDNA) stimulated IFNαβ and IL-1β (by 3hrs) and IDO activity by 24 hours (Table 1). DNPs did not induce IFNαβ or IDO but still induced IL-1β in STING-deficient (STING-KO) mice (Table 1). Moreover, IL-1β and IFNαβ expression peaked ~3 and ~6hrs after treatment in DNP-treated B6 mice, respectively (data not shown), indicating that IFNαβ and IL-1β were induced via distinct pathways. IFNαβ and IDO induction was also abolished in diphtheria toxin (DT) treated CD11cDTR mice expressing human diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR) under control of CD11c promoters to deplete DCs (Table 1). DT-mediated depletion of marginal zone (MZ, CD169+) MΦs in CD169DTR mice did not block IFNαβ or IDO induction (Table 1). Systemic treatment with c-diGMP (200µg, i/v), a microbial second messenger sensed by STING (17), induced IFNαβ, IDO and to a lower extent IL-β, and these responses were STING dependent (Table 1). Thus cargo DNA was sensed via STING to induce IDO and DCs mediated this response, while MZ MΦs that mediated regulatory responses to apoptotic cells via IDO (12, 13) were not required to induce IDO after DNP treatment.

Table 1.

DCs sense DNA via STING to induce IFNαβ and IDO

| Mice | DNPs (c-diGMP) |

IFNαβ1 (U/µl) |

IL-1β2 (ng/ml) |

IDO activity3 (pmol/hr/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B6 (9) | − | <0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 9.6 ± 1.4 |

| B6 (10) | + | 2.9 ± 0.4*** | 5.2 ± 0.9** | 25.9 ± 2.5*** |

| STING-KO (5) | − | <0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 6.4 ± 1.6 |

| STING-KO (3) | + | <0.1 | 3.3 ± 0.4** | 7.6 ± 2.3 |

| CD11cDTR +DT (1) | − | <0.1 | nt | 5.1 |

| CD11cDTR +DT (2) | + | 0.2 ± 0.1# | nt | 7.3 ± 2.1 |

| CD169DTR +DT (2) | − | <0.1 | nt | 5.7 ± 0.5 |

| CD169DTR +DT (3) | + | 2.0 ± 0.3* | nt | 26.3 ± 4.4* |

| B6 (4) | c-diGMP4 | 7.8 ± 0.8*** | 0.9 ± 0.2* | 16.3 ± 3.3* |

| STING-KO (2) | c-diGMP4 | <0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.04 | 6.5 ± 0.3 (3) |

Notes.

serum bioactivity (24hr);

spleen (3hr);

spleen (Kyn ex vivo, 24hr);

200µg (i/v);

p<0.0001,

p<0.01,

p<0.05;

, not significant; nt, not tested.

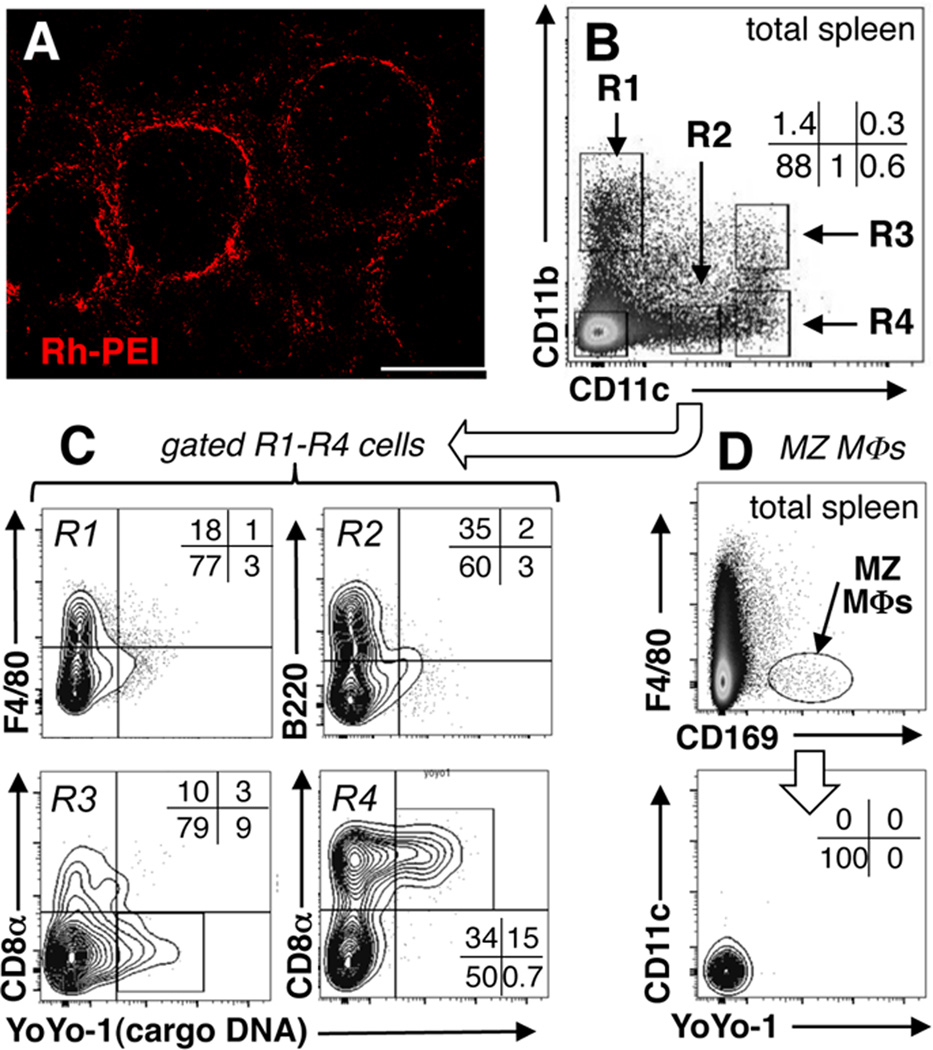

Discrete populations of MZ DCs ingest DNPs rapidly

Rhodamine-conjugated polyethylenimine (Rh-PEI) containing CpGfree cargo DNA was used to identify cells that ingested DNPs rapidly. After brief treatment with Rh-DNPs (i/v, 3hrs) Rh-PEI staining was concentrated in splenic marginal zone (MZ, Fig. 1A), and Rh staining associated strongly with the MZ macrophage (MΦ) marker CD169 and to lesser extents with MZ DCs (CD11c) and myeloid (CD11b) cells (Supplemental Fig. S1A). Cultured cells ingest DNPs containing PEI by non-specific endocytosis (18), though uptake mechanisms in physiologic cells remain poorly defined.

Figure 1. Identifying spleen cells that ingest DNPs.

A. B6 mice were treated with Rhodamine (red)-PEI DNPs (Rh-DNPs, i/v) and after 3hrs spleen sections were examined to detect stained cells; original magnification, ×100; scale bar, 200µm. B–D. Nanoparticles containing YoYo-1 labeled cargo pDNA were injected into B6 mice (i/v, 3hrs), and myeloid (CD11c+, CD11b+) cells (B, C) and CD169+ MZ MΦs (D) were analyzed to detect cargo DNA (YoYo-1+). Data are representative of experiments using >3 mice.

To identify cells containing ingested cargo DNA B6 mice were treated with DNPs containing PEI and CpGfree cargo DNA labeled with a fluorescent dye (YoYo-1). After 3hrs, small numbers of DCs (CD11c+) and non-DCs contained YoYo-1+ DNA relative to untreated mice (Supplemental Fig. S1BC). Myeloid cells were analyzed to detect cargo DNA (Fig. 1BC, R1–R4), which was present in ~10% of myeloid DCs (R3, CD8αneg) and ~15% of other DCs (R4, CD8α+), while no cargo DNA was detected in MΦs (R1, F4/80+) or plasmacytoid DCs (R2, B220+). Surprisingly, MZ MΦs (CD169+, F4/80neg) that ingested DNPs rapidly contained no detectable cargo DNA (Fig. 1D), suggesting that cargo DNA was degraded soon after DNP uptake. Most gated YoYo-1+ DCs expressed the integrin CD103, a marker of regulatory DCs (19) and F4/80 (Supplemental Fig. S1DE). Some myeloid (CD8αneg) DCs expressed the immune activating marker 33D1 (20), but CD8α+ DCs did not (Supplemental Fig. S1DE). Thus cargo DNA accumulated rapidly and selectively in small populations of DCs and non-DCs located in splenic MZ.

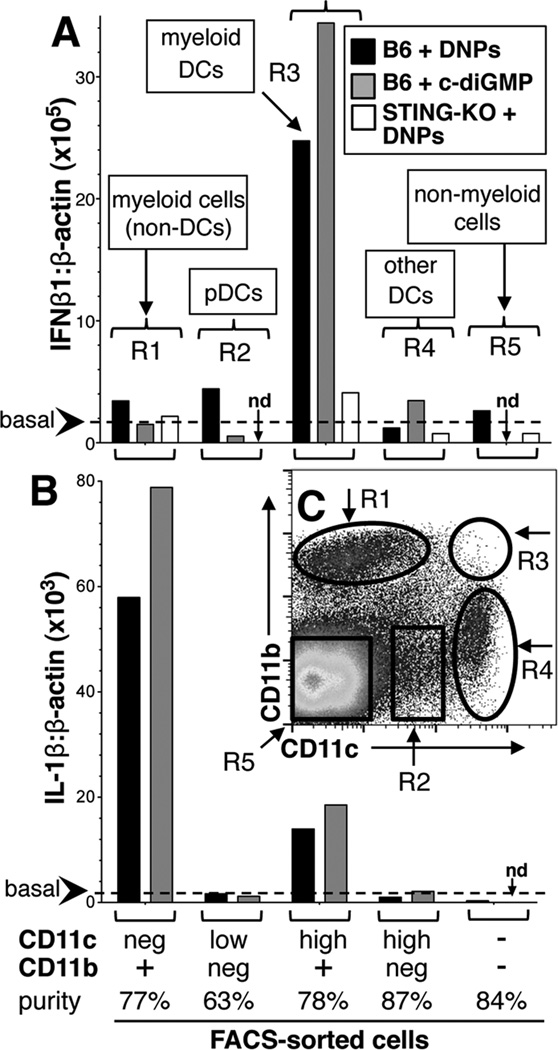

CD11b+ DCs respond selectively to nanoparticle cargo DNA and c-diGMP

To identify cells that sensed and responded rapidly to cargo DNA B6 mice were treated with DNPs (3hrs) and IFNβ1 transcription was assessed in FACS-sorted (Mo-Flo) splenocytes expressing CD11c and/or CD11b. IFNβ1 was selected as STING activates IRF3, a potent IFNβ inducer (21), and the FACS sorting strategy is shown in Fig. 2C (R1–R4). IFNβ1 transcription was elevated only in sorted myeloid CD11b+ DCs relative to basal levels in untreated mice (Fig. 2A, black bars), relative to basal levels in untreated mice (Fig 2A, dotted line). Selective IFNβ1 induction in CD11b+ DCs was also observed in mice treated with c-diGMP (Fig. 2A, gray bars); as expected DNPs did not induce IFNβ1 in STING-KO mice (Fig 2A, white bars). Cell-type specific responses to DNPs and c-diGMP also manifested when IL-1β transcription was assessed but myeloid non-DCs were the major source of IL-1β (Fig. 2B). Thus, CD11b+ DCs ingested and sensed DNPs and c-diGMP via STING to stimulate IFNβ. In contrast, non-DC myeloid cells sensed these reagents to induce IL-1β but not IFNαβ via a STING-independent pathway (Table 1). Functional diversity regarding DNA responsiveness amongst physiologic innate immune cells has not been described previously. Our findings suggest that splenic CD11b+ DCs may occupy a distinct functional niche, potentially acting as sentinels to detect blood borne sources of DNA such as microbes and apoptotic cells. Consistent with this notion, intra-vital analyses of lymph nodes revealed that CD11b+ DCs were the major cell type that ingested immunizing antigens rapidly (22). Their counterparts in splenic MZ may also ingest and sense DNA selectively to induce rapid regulatory responses via IDO that lower the risk of autoimmunity. Hence functional dichotomy amongst innate immune cells may be pivotal in elaborating diametric responses to DNA that incite or suppress immunity. Disparate DNA sensitivity may arise due to differential ability to ingest, degrade or respond to DNA amongst innate immune cells. Thus, most CD169+ MZ MΦs and some CD8α+ DCs ingested DNPs but did not respond, suggesting that cargo DNA was degraded rapidly or did not enter the cytosolic compartment, or that cytosolic DNA sensing via STING is defective in these cell types.

Figure 2. Nanoparticle cargo DNA and c-diGMP induce selective IFNβ1 expression by myeloid DCs.

B6 mice were treated with DNPs or c-di-GMP (i/v, 3hrs). Splenocytes from treated mice were stained with CD11c and CD11b mAbs and cells were FACS-sorted using gates shown in panel C (R1–R5). AB. qRT-PCR analysis was performed on RNA from sorted cells to detect IFNβ1, IL-1β and β-actin transcripts. Data show IFNβ1:β-actin (A) and IL-1β:β-actin (B) ratios for each sorted cell population and are representative of experiments using 2 or more mice. Dotted lines indicate basal IFNβ1:β-actin or IL-1β:β-actin ratios in RNA from untreated mice (<2 × 105 & <2 × 103, respectively); nd, not done.

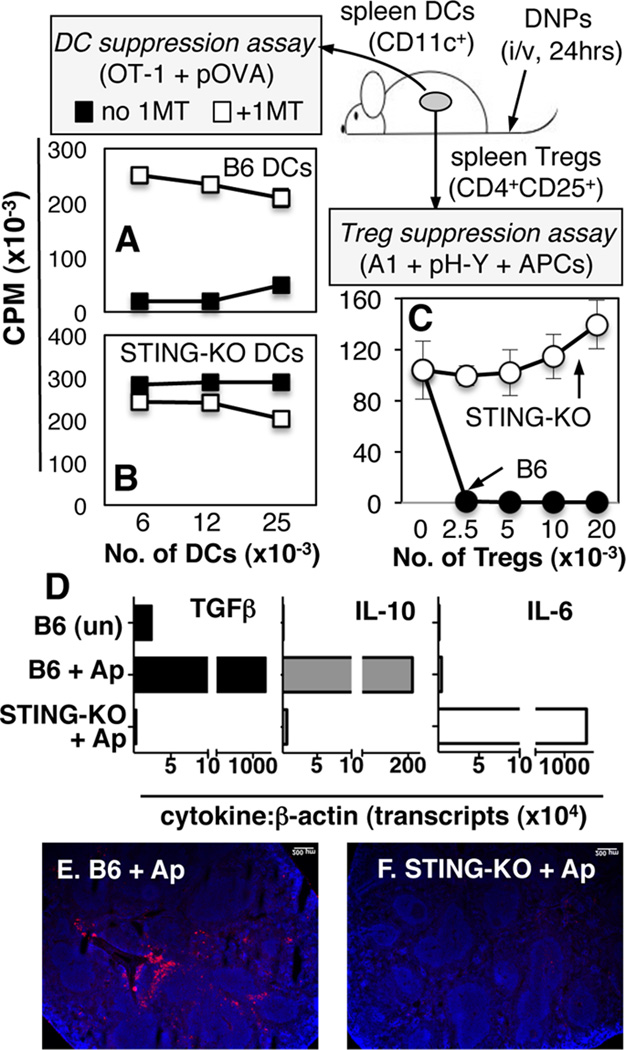

STING mediates dominant regulatory responses to DNPs

DCs and Tregs acquired potent T cell regulatory phenotypes soon after DNP treatment (9). To test if intact STING was required for regulatory responses to DNPs splenic DCs or Tregs from DNP-treated mice were cultured with responder T cells as described (9). Splenic DCs from DNP-treated STING-KO mice stimulated robust OVA-specific (OT-1) T cell responses in the presence of OVA peptide (Fig. 3B, closed symbols) and adding the IDO-specific inhibitor 1-methyl-[D]-tryptophan (1MT) did not enhance responses (Fig. 3B, open symbols). As expected, DCs from DNP-treated B6 mice suppressed OT-1 responses via IDO (Fig. 3A). Moreover, FACS-sorted CD19+ DCs but not conventional (CD19neg) DCs from DNP-treated B6 mice mediated suppression via IDO (Supplemental Fig. S2AB). Splenic Tregs from DNP-treated STING-KO mice did not suppress male (H-Y)-specific (A1) T cell responses elicited ex vivo (Fig. 3C, open symbols); as expected, Tregs from DNP-treated B6 mice suppressed A1 T cell proliferation (Fig. 3C, closed symbols). Thus, cargo DNA sensing via STING was essential for DCs and Tregs to acquire potent regulatory phenotypes after DNP treatment.

Figure 3. STING mediates regulatory responses to DNPs and dying cells.

B6 (A, C) or STING-KO (B, C) mice were treated with DNPs (i/v, 24hrs). AB. Graded numbers of MACS-enriched DCs from treated mice were cultured with OT-1 T cells, OVA peptide (pOVA), +/− 1MT, and T cell proliferation was assessed by measuring 3H-Thy incorporation after 72hrs. C. Graded numbers of MACS-enriched Tregs from treated mice were cultured with H-Y-specific (A1) CD4 T cells, APCs (CBA), H-Y-peptide (pH-Y), and T cell proliferation was assessed as before. Data are the means (+/−1sd) of triplicate cultures and are representative of at least 2 experiments. D–F. B6 or STING-KO mice were treated with apoptotic thymocytes (Ap, 107, i/v). After 8hrs RNA was made from FACS-sorted splenic DCs (CD11c+) and qRT-PCR was used to detect cytokine gene transcripts (D). Data are cytokine:β-actin transcript ratios (×10−4) for each RNA sample. EF. Immunofluorescence staining to detect IDO in spleens of mice treated (i/v) with apoptotic cells for 24hrs.

To evaluate if STING ablation modified responses to dying (apoptotic) cells B6 and STING-KO mice were treated with apoptotic thymocytes (107, i/v) as described (12). STING ablation abolished hallmark TGFβ and IL-10 regulatory cytokine induction by apoptotic cells and pro-inflammatory IL-6 was expressed instead (Fig. 3D); moreover, apoptotic cells did not induce IDO expression in spleens of STING-KO mice (Fig. 3F). These outcomes suggest that DNA from dying cells is sensed via STING to induce regulatory responses via IDO analogous to regulatory responses induced by DNPs.

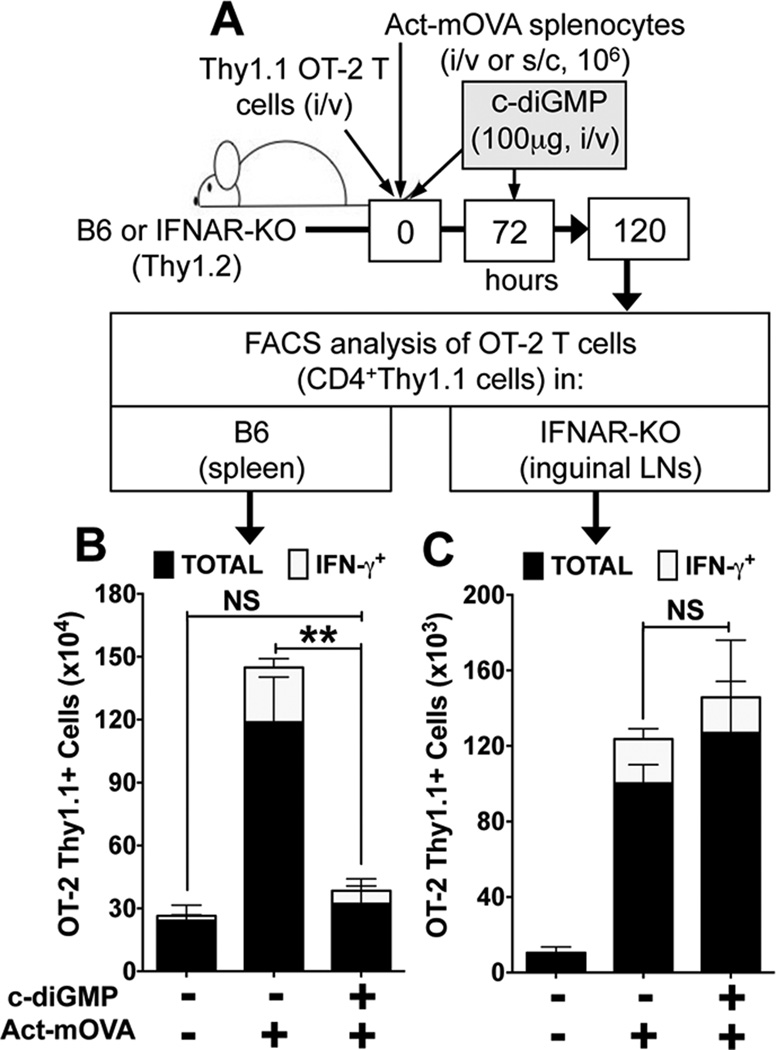

c-diGMP inhibits antigen-specific Th1 responses

DNPs suppressed Th1 responses by OVA-specific (OT-2) T cells to OVA immunization via IDO (9) and we hypothesized that STING activation mediates regulatory responses in this model. As OT-2 T cell adoptive transfer is not feasible, since STING-KO mice do not have pure B6 backgrounds, we instead used c-diGMP to activate STING during OVA immunization and monitored the impact on responses by marked (Thy1.1) OT-2 T cells (Fig. 4A). Systemic c-diGMP treatment suppressed OT-2 clonal expansion and Th1 (IFNγ+, white bars) differentiation significantly relative to controls (Fig. 4A and Supplemental Fig. S2C). Moreover, c-diGMP treatment did not inhibit OVA-specific Th1 responses in IFNαβ receptor deficient (IFNAR-KO) mice (Fig. 4C), indicating that the STING-IFNαβ pathway mediated regulatory responses in this model. These outcomes contrast with reports that c-diGMP exhibited immune activating (adjuvant) properties when administered to mice subcutaneously (23). Thus the route of c-diGMP delivery to activate STING is a critical factor influencing immune outcomes.

Figure 4. c-diGMP suppresses OVA-specific Th1 effector responses.

A. B6 or IFNAR-KO (Thy1.2) mice harboring OVA-specific OT-2 CD4 T cells (Thy1.1) were immunized (i/v, B6 or s/c, IFNAR-KO) with spleen cells from Act-mOVA mice and treated with c-diGMP (100µg, i/v) as indicated. 120hrs after OVA immunization spleen (B) or inguinal (draining) LN (C) cells were analyzed to detect total OT-2 T cells (CD4+Thy1.1, black bars) and OT-2 Th1 cells (CD4+Thy1.1IFNγ+, white bars). Data are the mean numbers of OT-2 T cells in spleen or LNs from two combined experiments (n=6). ** p<0.004, NS, not significant.

In summary, the findings we report here show for the first time that selective nanoparticle cargo DNA uptake and DNA sensing via STING in discrete populations of myeloid DCs mediates potent T cell regulatory responses. Consistent with these findings, systemic c-diGMP treatment to activate STING also induced IDO and suppressed Th1 responses to OVA immunization. Moreover, regulatory responses induced by apoptotic cells were STING dependent. These findings contradict the emerging paradigm that DNA sensing via the STING-IFN αβ pathway incites immunity and autoimmunity (7, 8). We hypothesize that discrete populations of myeloid DCs in mouse lymphoid tissues function as sentinel cells that suppress pro-inflammatory and autoimmune responses to DNA by ingesting, sensing and responding rapidly to cellular, microbial or viral DNA entering the cytosolic compartment, as well as cyclic dinucleotides made by infectious pathogens such as Listeria (24). Further, we hypothesize that IFNαβ released selectively by CD11b+ DCs in response to these stimuli induces selective IDO expression by MZ CD19+ DCs in spleen, which activate Tregs to promote dominant regulatory responses. Thus DNA sensing via STING inhibits or incites immunity, and different routes of DNA exposure, acute or chronic DNA exposure, and differential uptake, degradation and sensing of DNA by specific innate immune or other cell types are pivotal factors that influence immune responses to DNA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jeanene Pihkala and William King for technical help with FACS sorting and analysis. A.L.M. and D.H.M. serve as consultants to NewLink Genetics Inc. and receive income from this source.

Footnotes

This study was supported by grants to A.L.M. from the Carlos and Marguerite Mason Trust and the NIH (AI083005).

References

- 1.Choubey D. DNA-responsive inflammasomes and their regulators in autoimmunity. Clinical immunology. 2012;142:223–231. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Z, Yuan B, Bao M, Lu N, Kim T, Liu YJ. The helicase DDX41 senses intracellular DNA mediated by the adaptor STING in dendritic cells. Nature immunology. 2011;12:959–965. doi: 10.1038/ni.2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Unterholzner L, Keating SE, Baran M, Horan KA, Jensen SB, Sharma S, Sirois CM, Jin T, Latz E, Xiao TS, Fitzgerald KA, Paludan SR, Bowie AG. IFI16 is an innate immune sensor for intracellular DNA. Nature immunology. 2010;11:997–1004. doi: 10.1038/ni.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts TL, Idris A, Dunn JA, Kelly GM, Burnton CM, Hodgson S, Hardy LL, Garceau V, Sweet MJ, Ross IL, Hume DA, Stacey KJ. HIN-200 proteins regulate caspase activation in response to foreign cytoplasmic DNA. Science. 2009;323:1057–1060. doi: 10.1126/science.1169841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Civril F, Deimling T, de Oliveira Mann CC, Ablasser A, Moldt M, Witte G, Hornung V, Hopfner KP. Structural mechanism of cytosolic DNA sensing by cGAS. Nature. 2013;498:332–337. doi: 10.1038/nature12305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barber GN. STING-dependent signaling. Nature immunology. 2011;12:929–930. doi: 10.1038/ni.2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahn J, Gutman D, Saijo S, Barber GN. STING manifests self DNA-dependent inflammatory disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:19386–19391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215006109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gall A, Treuting P, Elkon KB, Loo YM, Gale M, Jr, Barber GN, Stetson DB. Autoimmunity initiates in nonhematopoietic cells and progresses via lymphocytes in an interferon-dependent autoimmune disease. Immunity. 2012;36:120–131. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang L, Lemos HP, Li L, Li M, Chandler PR, Baban B, McGaha TL, Ravishankar B, Lee JR, Munn DH, Mellor AL. Engineering DNA Nanoparticles as Immunomodulatory Reagents that Activate Regulatory T Cells. Journal of immunology. 2012;188:4913–4920. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishikawa H, Ma Z, Barber GN. STING regulates intracellular DNA-mediated, type I interferon-dependent innate immunity. Nature. 2009;461:788–792. doi: 10.1038/nature08476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung S, Unutmaz D, Wong P, Sano G, De los Santos K, Sparwasser T, Wu S, Vuthoori S, Ko K, Zavala F, Pamer EG, Littman DR, Lang RA. In vivo depletion of CD11c(+) dendritic cells abrogates priming of CD8(+) T cells by exogenous cell-associated antigens. Immunity. 2002;17:211–220. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00365-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ravishankar B, Liu H, Shinde R, Chandler P, Baban B, Tanaka M, Munn DH, Mellor AL, Karlsson MC, McGaha TL. Tolerance to apoptotic cells is regulated by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:3909–3914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117736109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyake Y, Asano K, Kaise H, Uemura M, Nakayama M, Tanaka M. Critical role of macrophages in the marginal zone in the suppression of immune responses to apoptotic cell-associated antigens. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007;117:2268–2278. doi: 10.1172/JCI31990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoshi M, Saito K, Hara A, Taguchi A, Ohtaki H, Tanaka R, Fujigaki H, Osawa Y, Takemura M, Matsunami H, Ito H, Seishima M. The absence of IDO upregulates type I IFN production, resulting in suppression of viral replication in the retrovirus-infected mouse. Journal of immunology. 2010;185:3305–3312. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mellor AL, Baban B, Chandler PR, Manlapat A, Kahler DJ, Munn DH. Cutting Edge: CpG Oligonucleotides Induce Splenic CD19+ Dendritic Cells to Acquire Potent Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase-Dependent T Cell Regulatory Functions via IFN Type 1 Signaling. Journal of immunology. 2005;175:5601–5605. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.5601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baban B, Chandler PR, Johnson BA, 3rd, Huang L, Li M, Sharpe ML, Francisco LM, Sharpe AH, Blazar BR, Munn DH, Mellor AL. Physiologic Control of IDO Competence in Splenic Dendritic Cells. Journal of immunology. 2011;187:2329–2335. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burdette DL, Monroe KM, Sotelo-Troha K, Iwig JS, Eckert B, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Vance RE. STING is a direct innate immune sensor of cyclic di-GMP. Nature. 2011;478:515–518. doi: 10.1038/nature10429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kircheis R, Wightman L, Wagner E. Design and gene delivery activity of modified polyethylenimines. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2001;53:341–358. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaensson E, Uronen-Hansson H, Pabst O, Eksteen B, Tian J, Coombes JL, Berg PL, Davidsson T, Powrie F, Johansson-Lindbom B, Agace WW. Small intestinal CD103+ dendritic cells display unique functional properties that are conserved between mice and humans. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2008;205:2139–2149. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dudziak D, Kamphorst AO, Heidkamp GF, Buchholz VR, Trumpfheller C, Yamazaki S, Cheong C, Liu K, Lee HW, Park CG, Steinman RM, Nussenzweig MC. Differential antigen processing by dendritic cell subsets in vivo. Science. 2007;315:107–111. doi: 10.1126/science.1136080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barnes B, Lubyova B, Pitha PM. On the role of IRF in host defense. Journal of interferon & cytokine research : the official journal of the International Society for Interferon and Cytokine Research. 2002;22:59–71. doi: 10.1089/107999002753452665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerner MY, Kastenmuller W, Ifrim I, Kabat J, Germain RN. Histo-cytometry: a method for highly multiplex quantitative tissue imaging analysis applied to dendritic cell subset microanatomy in lymph nodes. Immunity. 2012;37:364–376. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gray PM, Forrest G, Wisniewski T, Porter G, Freed DC, Demartino JA, Zaller DM, Guo Z, Leone J, Fu TM, Vora KA. Evidence for cyclic diguanylate as a vaccine adjuvant with novel immunostimulatory activities. Cellular immunology. 2012;278:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sauer JD, Sotelo-Troha K, von Moltke J, Monroe KM, Rae CS, Brubaker SW, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Woodward JJ, Portnoy DA, Vance RE. The N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea-induced Goldenticket mouse mutant reveals an essential function of Sting in the in vivo interferon response to Listeria monocytogenes and cyclic dinucleotides. Infection and immunity. 2011;79:688–694. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00999-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.