Abstract

This review article focuses on the impact that the presence of pain has on drug self-administration in rodents, and the potential for using self-administration to study both addiction and pain, as well as their interaction. The literature on the effects of noxious input to the brain on both spinal and supraspinal neuronal activity is reviewed, as well as the evidence that human and rodent neurobiology is affected similarly by noxious stimulation. The convergence of peripheral input to somatosensory systems with limbic forebrain structures is briefly discussed in the context of how the activity of one system may influence activity within the other system. Finally, the literature on how pain influences drug-seeking behaviors in rodents is reviewed, with a final discussion of how these techniques might be able to contribute to the development of novel analgesic treatments that minimize addiction and tolerance.

Introduction

There are two important concepts to consider regarding the importance of studying drug self-administration in the presence of chronic pain. One is the concept that the presence of pain alters the reinforcing effects of drugs, particularly opioids. Drug reinforcement mechanisms have been studied using a variety of approaches, including several behavioral paradigms and pharmacological as well as non-pharmacological methods. Documenting the ability of pathological or neurobiological manipulations to produce alterations in self-administered drug intake is typically a crucial experiment in establishing relevance to drug reinforcement. One possible ramification of pain producing a distinct pharmacology of opioid self-administration is that strategies to limit opioid intake in pain patients might be best studied using such methods, rather than conventional experimenter-delivered strategies. The other concept is that pain has various sensory components that are distinguished into two broad categories based upon the requirement of an external stimulus, typically referred to as elicited and spontaneous pain. Clinically, it has been shown that elicited pain and spontaneous pain possess unique characteristics and distinct pharmacotherapies (Backonja and Stacey, 2004; Eisenach et al, 2003, 1995). The chief complaint that brings chronic pain patients to the clinic is spontaneous rather than elicited pain (Backonja and Stacey, 2004; Martin and Eisenach, 2001). In addition, opioids are effective against spontaneous pain and treatment of spontaneous pain is a primary goal of opioid therapy with chronic pain (Mogil and Crager, 2004). It is this second type of pain that is very difficult to model in laboratory animals and this review will present evidence that elective opioid intake through self-administration may provide an avenue through which to explore the treatment of spontaneous pain in rodents.

Patient-controlled analgesia

Patient-controlled analgesia permits individuals to regulate their dosing intervals through operant behavior. This technique has been used extensively since the early 1980’s, principally for treatment of post-operative pain with opioids. Although variations exist, most PCA paradigms consist of the same basic features: an initial loading dose administered by staff, a demand dose self-administered by the patient, a lockout interval following each infusion (e.g., a time-out), and hourly limits on the number of infusions available (for historical review, see Grass 2005). This contrasts with a more conventional approach to administration of analgesics in the clinic, in which patients are provided medication by staff at predetermined intervals, and do not have ready access to additional medication as needed without assistance from the staff. Marks and Sachar (1973) found that this type of treatment resulted in a large proportion of patients being under treated for pain and led to a philosophically different approach to treatment of pain, namely providing analgesics on demand through self-administration, or PCA. The guiding principles for currrent PCA use and refinement were largely developed from the work of Austin and colleagues (1980), demonstrating the relationships between dosing intervals, plasma concentrations, and pain scores in post-operative patients. Similar studies have been conducted for a number of opioids and provide the basis for their successful use with PCA technologies (Dahlstrom et al., 1982; Tamsen et al., 1982; Lehman et al., 1988, 1991).

The improved analgesic efficacy or increased patient satisfaction of therapy with PCA compared to conventional delivery of opioids for analgesia has been debated, an issue that Walder and colleagues (2001) address in a systematic review of 32 randomized controlled trials. These authors conclude that PCA of IV opioids is slightly more analgesic and is more preferred by patients versus conventional opioid analgesia. Meanwhile, opioid-related side effects are similar and there is no evidence that either method is more cost-effective. Hudcova and colleagues (2006) came to very similar conclusions in their systematic review, in which they describe PCA as having better pain control and higher patient satisfaction. These authors found that PCA patients consumed more opioids and had a higher incidence of pruritus (itching). Both reviews concluded that PCA with IV opioids was beneficial relative to conventional therapy chiefly as a result of increased patient satisfaction in the post-operative period.

Pharmacology of self-administration compared to experimenter-delivered paradigms

Self-administration paradigms can be used to ask questions that do not lend themselves to other procedures. Whether a drug will be electively administered, the preferred rate of drug intake, or the rate and extent of escalation of drug intake are parameters that cannot be determined using experimenter-delivered dosing schemes. However it has also become apparent over nearly 3 decades of research that the neurobiological and neurochemical consequences of drug intake can differ depending upon whether the animal self-administers the drug or if the drug is passively administered. These studies have utilized a yoking procedure in which one animal actively self-administers the drug while another yoked subject is passively infused with the same drug, dose, and temporal pattern of infusion (Smith et al., 2004, 2003, 1984, 1982, 1980).

Laboratory studies measuring the antinociceptive effects of opioids in animals rely heavily on noncontingent drug delivery. However, drugs produce different effects on the brain when animals are allowed to control delivery through self-administration compared with experimenter-delivered paradigms. Our understanding of these differences became possible in the 1960’s with the inception of drug-reinforced operant conditioning paradigms (review, Ator and Griffiths, 2003). Utilizing these techniques, Smith and colleagues provide definitive evidence that alterations in brain neurochemistry are different when opioids and psychostimulants are self-administered versus passively delivered to yoked rats (Smith et al., 2004, 2003, 1984, 1982, 1980). Rats have higher increases in dopamine in the nucleus accumbens during cocaine self-administration compared to yoked-infused rats, in agreement with the neurotransmitter turnover studies (Hemby et al., 1997). The turnover studies cited above produced a wealth of neurochemical data, typically measuring several different neurotransmitters in a myriad of brain structures. However, it is noteworthy that rats self-administering morphine experience decreases in norepinephrine turnover and increases in GABA and glutamate turnover in the amygdala when compared to rats receiving passive infusions of morphine (Smith et al., 1982). The relevance of the amygdala in reinforcement and pain circuitry is presented below.

The effects of self-administered and passively infused drugs differ not only in neurochemical measures, but produce differences in drug-induced gene expression changes as well (Jacobs et al., 2005, 2003). In particular, morphine self-administration, when compared to passive morphine injections in rats, is associated with an increase in protein kinase C in the amygdala, an enzyme that phosphorylates mu-opioid receptors and produces receptor desensitization (Rogriquez Parkitna et al., 2004). These findings are potentially important since the amygdala serves to integrate sensory input from the periphery with activity from limbic forebrain structures that are influenced by drug self-administration, as will be described in greater detail below. Behavioral effects of drugs are likely mediated through the ability of compounds to alter brain neurochemistry. Therefore if the neurochemical actions of drugs are altered by some means, self-administration versus passive infusion for example, then the behavioral effects will be altered in a correlative manner.

The study of chronic drug effects related to abuse liability necessitates the use of drug self-administration. Unlike passive infusions, self-administration incorporates many features of drug abuse, one of which is motivation, a feature that Stefanski and colleagues explore in a series of experiments. Comparing self-administering rats versus those receiving passive infusions, these researchers demonstrate a decrease in D2 receptors in the ventral tegmental area and D1 receptors in the nucleus accumbens selectively in rats self-administering methamphetamine, suggesting that tolerance to the reinforcing effects may occur selectively in rats that have control over drug intake (Stefanski et al., 1999). In contrast, chronic passive administration of cocaine, but not self-administration, reduces D2 receptor levels in striatum and nucleus accumbens of rats (Stefanski et al., 2007). Since most preclinical work assessing analgesic efficacy of opioids involves passive drug infusions, it would be worthwhile to assess the interaction between self-administration and the presence of pain on the pharmacology, neurochemistry and gene expression changes that occur throughout the brain.

Pain and imaging studies in humans and rodents: similar regions increase activity with noxious input

Numerous studies have described the brain areas activated or altered during acute and chronic pain in humans using in vivo imaging techniques. The primary brain areas that are involved appear to be the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), amygdala, thalamus and several brainstem nuclei such as the peri-aqueductal gray (PAG) and the rostroventromedial medulla (RVM) (for review, Porro, 2003; Peyron et al., 2000). Capsaicin-induced pain decreases [11C]-carfentanil binding in the medial thalamus, indicative of increased endogenous opioid peptide release (Bencherif et al., 2002). Sustained experimental pain increases endogenous opioid release in ipsilateral amygdala and contralateral thalamus in humans as measured using [11C]-carfentanil (Zubieta et al., 2001). Therefore, noxious stimulation increases neuronal activity in both somatosensory and limbic regions, and these effects are modulated by opioids in humans. Cold pain induces an increase in blood flow to medial thalamus, somatosensory and insular cortices and this effect is reduced by an analgesic dose of fentanyl (Casey et al., 2000). Thermal pain increases regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) in the caudal ACC and medial thalamus, whereas opioid analgesia increases rCBF in the brainstem and rostral anterior cingulate cortex and modulates the increases in other regions (Petrovic et al., 2002). In laboratory animals, both in vivo and in vitro imaging techniques have identified similarities in the brain areas involved in pain signaling between humans and rodents. A number of techniques have been employed such as 2-deoxyglucose uptake (2-DG), regional blood flow analysis (RBF) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). These techniques have all generally identified similar brain regions in rodents as those found in the citations above in humans. Noxious electrical stimulation of the sciatic nerve in rats induces an increase in activation of the ACC, medial thalamus and somatosensory cortex as measured by fMRI and these effects are reversed by morphine (Chang and Shyu, 2001). Noxious electrical stimulation of the sciatic nerve increases both cFOS expression and rCBF in the medial thalamus (Erdos et al., 2003). Forepaw injections of formalin in rats induce an increase in 2-DG uptake in most structures associated with both the spinothalamic tract and in limbic forebrain and associated cortical areas (Porro et al., 1999). Morphine will reverse the effects of acute footshock on 2-DG uptake in a number of pain-related structures, however is less effective when the footshock is applied daily for 15 days (Gescuk et al., 1995). Metabolic activity changes in a number of brain areas following chronic constriction of the sciatic nerve (Mao et al., 1999). These regions include numerous areas associated with the spinothalamic sensory discriminative system (cortical hind limb area, ventroposteriolateral thalamus) as well as those associated with affective responses to pain (cingulate cortex, amygdala, PAG, parabrachial nuclei, hypothalamic nuclei). Since these responses are similar to those produced by acute noxious stimulation, these authors conclude that nerve injury may produce spontaneous, ongoing pain even in the absence of peripheral nerve stimulation. Modulation of activity within these structures by noxious stimulation, particularly those associated with the limbic forebrain, supports the idea that the presence of pain would alter the pharmacology and neurochemistry of drug self-administration.

Peripheral nerve injury changes neuronal activity in both ascending and descending spinothalamic and spinomesencephalic tract neurons

Neuronal changes at the spinal level

Hypersensitivity following peripheral nerve injury is thought to be due to synaptic plasticity and reorganization in the spinal cord, and numerous studies have documented important changes that occur spinally following peripheral nerve injury. Opioid peptide mRNA is increased following excitotoxic spinal cord injury in the dorsal horn (Abraham et al., 2000). Partial sciatic nerve ligation increases RGS4, a protein that downregulates G-protein function (Garnier et al., 2003). Clonidine produces analgesia following nerve injury that is dependent on cholinergic fibers and occurs through m4 muscarinic receptors (Kang and Eisenach, 2003; Pan et al., 1999). Spinal nerve ligation (SNL) increases phosphorylation of CREB in ipsilateral spinal cord, and the hypersensitivity following SNL is diminished by intrathecal CREB antisense administration (Ma et al., 2003; Miletic et al., 2002; Ma and Quirion, 2001). Intrathecal administration of antisense for beta-arrestin2 also diminishes mechanical hypersensitivity following sciatic nerve injury (Przwelocka et al., 2002). SNL induces an increase in phosphorylation of mu-opioid receptors in ipsilateral spinal cord, an effect thought to limit the analgesic efficacy of spinally administered opioids in this model (Narita et al., 2004). The relevance of these spinal changes to the modulation of opioid analgesia following nerve injury continues to be investigated. Whether altered spinal input to the brain is responsible for differential behavioral effects of opioids following nerve injury other than reversal of hypersensitivity is not known. Ascending fibers from the spinal dorsal horn influence higher brain structures, including the amygdala as outlined below, and a tonic increase in the firing of these neurons is likely to influence the activity of supraspinal sites. The interaction of the peripheral nervous system with central sites that modulate drug self-administration through ascending spinal systems has not been documented, however given the convergence of ascending sensory systems with limbic forebrain structures it is likely that spinal input indirectly modifies limbic activity and thereby influences drug reinforcement.

Neuronal changes that occur supraspinally

It is postulated that the behavioral effects of peripheral nerve injury occur at least in part due to an alteration in the supraspinal nociceptive processing system, since consistent changes have been found in brains of both humans and laboratory animals using in vivo imaging techniques as described above. Numerous neurochemical and biochemical changes in supraspinal sites occur following peripheral nerve injury. Opioid peptide mRNA is increased in anterior cingulate cortex following spinal cord injury (Abraham et al., 2001). There is an increase in cFOS expression in the gracile nucleus following spinal nerve injury, a region that receives input from dorsal horn neurons and projects to the medial thalamus (Shortland and Molander, 1998; Noguchi et al., 1995; Persson et al., 1993). SNL induces an increase in the firing of descending facilitory pathways arising in the RVM of the brainstem, and destruction of these neurons by an opioid linked to a neurotoxin (dermorphin-saporin) or injection of lidocaine into the RVM reverses the allodynia resulting from nerve injury (Porreca et al., 2001). It is not known which of these changes are responsible for the behavioral effects of nerve injury or the differential pharmacology of opioids following nerve injury. Alterations in supraspinal brain sites induced by peripheral nerve injury continues to be a fervent research topic, both in laboratory animals and humans, and these changes likely underlie many of the affective symptoms of chronic pain, such as depression and anxiety (Gureje, 2008, 2007; Von Korff et al., 2005).

The role of the amygdala in pain transmission: control of descending modulation

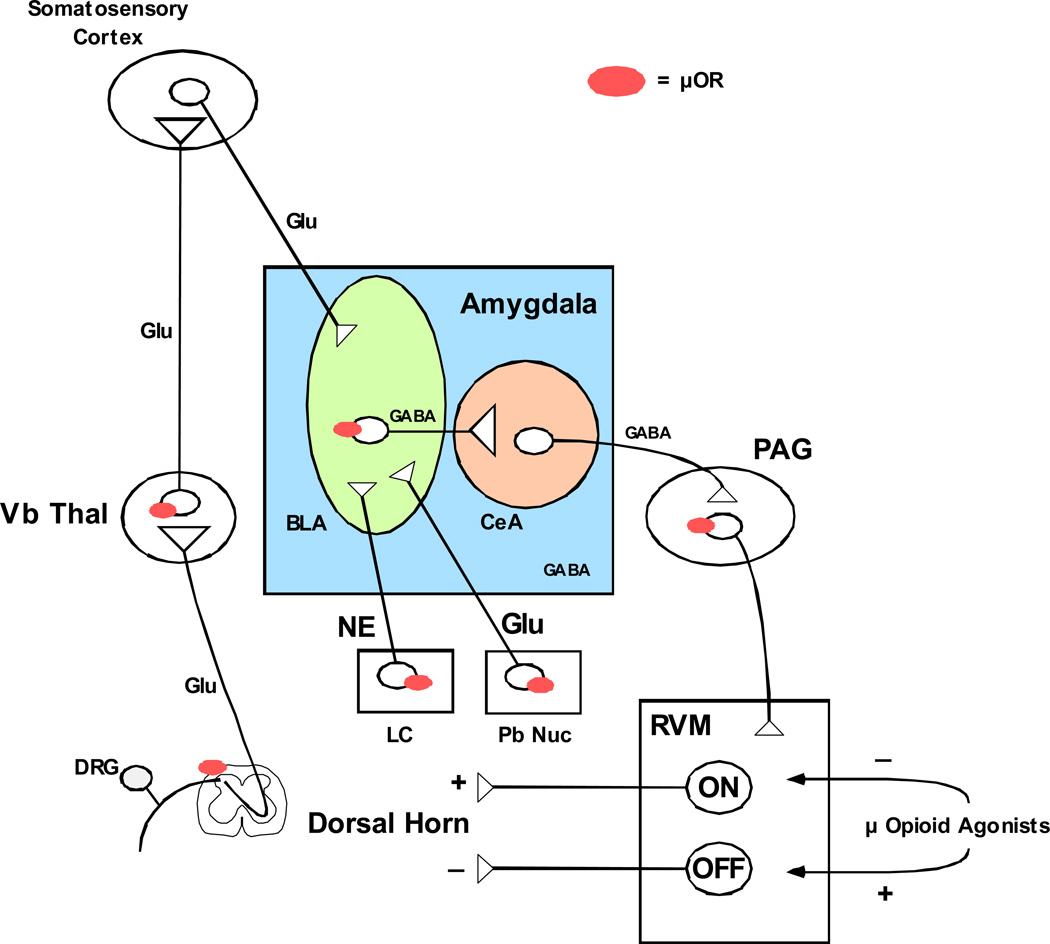

The amygdala produces descending modulation of pain circuits through projections to the peri-aqueductal gray (PAG) and rostroventral medulla (RVM) and opioid analgesia produced by direct injection into the amygdala is dependent upon this descending modulation (Figure 1) (Tershner and Helmstetter, 2000; Helmstetter et al., 1998). Mu-opioids appear to induce analgesia in the amygdala by inhibiting GABAergic projection neurons from the basolateral nucleus to the central nuclei, which in turn send projection neurons to the PAG and RVM (Finnegan et al., 2005). Amygdala neurons display plasticity associated with persistent pain, including an increase in firing rate and alterations in glutamatergic receptor subunit expression (Han and Neugebauer, 2005; Neugebauer et al. 2003). Experimental arthritis induces an upregulation of glutamatergic activity in parabrachial neurons projecting to the central amygdala, resulting in an increase in PKA mediated phosphorylaton of glutamatergic NR1 subunits, an effect that is blocked by administration of NMDA antagonists (Bird et al., 2005). The amygdala also receives noradrenergic input from the locus coeruleus, a region that has a dense mu-opioid population and these inputs are modulated by stress (Morilak et al., 2005). Although the influence of noradrenergic mechanisms on fear-conditioning learning and memory has been well established (review, McGaugh, 2000), and noradrenergic hyperactivity of the locus coeruleus in opioid withdrawal states is known to have a role in physical withdrawal symptoms, the influence of this circuit in chronic pain states, particularly regarding addiction and tolerance has not been investigated.

Figure 1. Descending modulation of pain transmission by Amyg-PAG-RVM circuit.

The amygdala has a key role in the descending modulation of pain transmission (review Fields, 2000). Glutamatergic (Glu) inputs from cortical areas are numerous in the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala (BLA), which sends GABAeregic projections to the central nucleus (CeA). GABAergic efferents from the CeA synapse in the periaqueductal gray (PAG), which in turn send excitatory output to the rostroventral medulla (RVM). The RVM contains two distinct cell types delineated largely based on their firing patterns and their effect on dorsal horn neurons. ON cells stimulate the firing of neurons in superficial laminae of the dorsal horn, which stimulate pain transmission through the spinothalamic tract. OFF cells inhibit the firing of neurons in the superficial laminae of the dorsal horn. Opioids injected directly into the RVM inhibit ON cells and stimulate OFF cells, and these actions are thought to be particularly important for opioid analgesia. Chronic neuropathic pain is thought to arise in part through disruption of descending inhibition of dorsal horn through the Amyg-PAG-RVM pathway, but the specific mechanisms are not understood. The role of this pathway in modulating opioid self-administration in the presence of chronic neuropathic pain is unknown, as well as how this pathway is affected by chronic opioid self-administration.

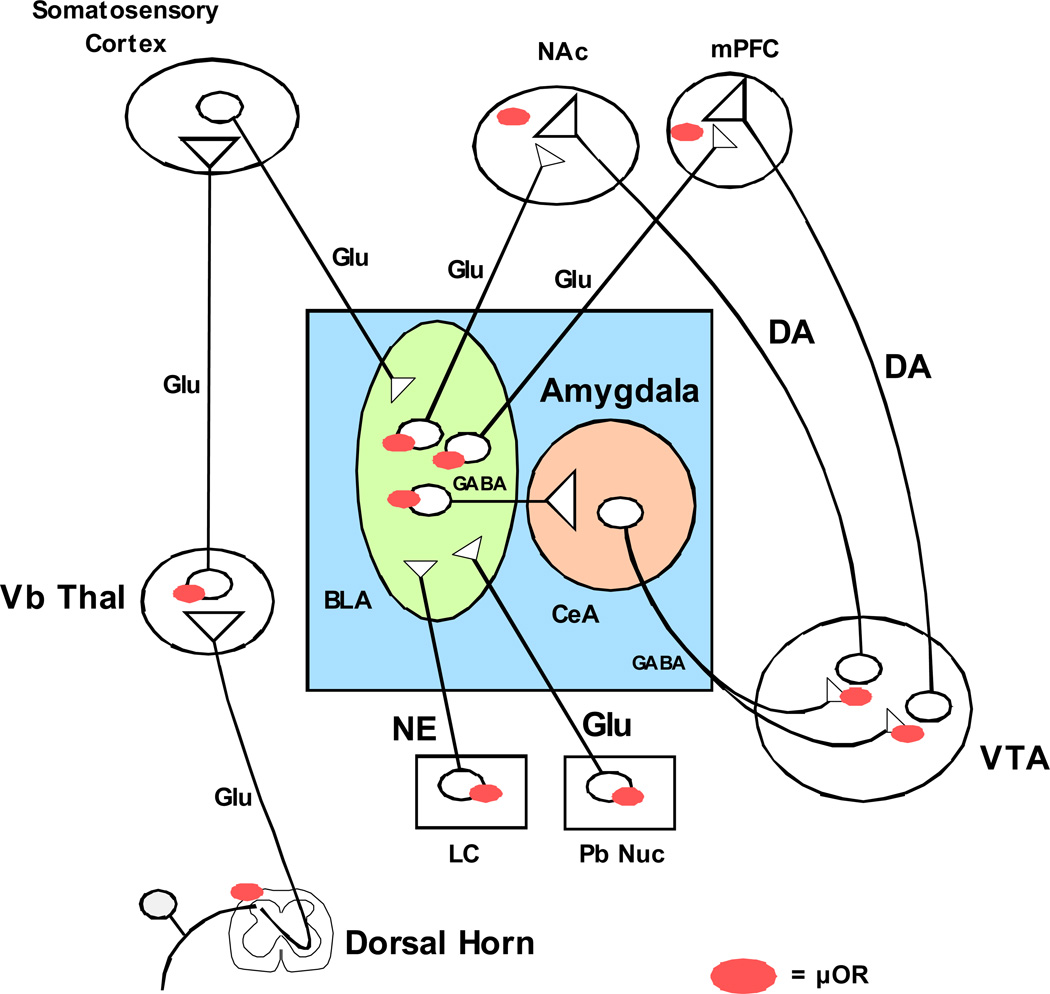

The amygdala has a key role in the interactions between pain pathways and the limbic system

Since pain processing systems and reinforcing systems overlap substantially as outlined above, it is likely that the activation or suppression of both pain and reinforcement systems produce salient alterations in the activity and neurobiology of each other. The amygdala has numerous connections with limbic, midbrain and brainstem structures and is positioned to modulate complex interactions between somatosensory systems, memory and reinforcement systems (Figure 2) (Pitkanen et al., 2003; Price et al., 2003). The basolateral amygdala sends excitatory glutamatergic projections to the NAc and mPFC which synapse directly on dopaminergic nerve endings (Brog et al., 1993; Wright et al., 1996). The central nucleus sends inhibitory GABAergic fibers to the VTA, which synapse on the cell bodies of the DAergic neurons that project to the NAc and VP (Everitt et al., 1999; 2000). Therefore, the amygdala can either positively or negatively modulate these two important limbic regions. Peripheral nerve injury diminishes conditioned place preference to morphine in mice, and this effect is associated with a decrease in neuronal activity in both the NAc and VTA as measured by cFOS immunohistochemistry (Narita et al., 2003). The loss in reinforcing efficacy of morphine following nerve injury is accompanied by an increase in GRK2 levels in the VTA, suggesting that an increase in mu-opioid receptor phosphorylation may underlie the diminished effects of opioids following nerve injury (Ozaki et al., 2002). The mechanism of the diminished activity of the limbic system following nerve injury is not known, but could occur through activation of the GABAergic fibers from the central amydgaloid nuclei. Noxious stimulation selectively depresses dopaminergic neurons within the VTA through an unknown mechanism, which likely results in diminished activity in forebrain projection neurons (Ungless et al., 2004). The amygdala, NAc and VTA all contain mu-opioid receptors that modulate behavior and neuronal activity, but the relative importance of each region in modulating the reinforcing effects of opioids in the presence of pain is not known.

Figure 2. Amygdala circuitry with limbic forebrain and ascending spinothalamic pain pathways.

The basolateral amygdala (BLA) receives glutamatergic (Glu) input from multiple cortical regions, including somatosensory cortex and from the parabrachial nucleus (Pb Nuc). The primary noradrenergic (NE) input comes from the locus coeruleus (LC). The BLA sends GABAergic afferents to the central amygdala nucleus (CeA) and glutamatergic fibers to the limbic forebrain regions nucleus accumbens (NAc) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) that synapse directly on ascending dopaminergic (DA) nerve endings that originate from the ventral tegmental area (VTA). The CeA sends GABAergic fibers to the VTA that synapse directly on the DA cells that project to limbic forebrain. The regulation of glutamate, GABA and NE release in the amygdala during opioid self-administration is poorly understood, particularly in the presence of chronic pain. Mu opioid receptors are located at numerous sites within these regions, however the regulation of neurons within these regions during opioid self-administration in an underlying chronic pain state is not known.

What is pain? Going beyond flicks and flinches

Most of the pharmacology of opioids and other analgesics has been developed in preclinical settings using relatively simple reflexive withdrawal assays of nociception, such as tail flick, paw withdrawal, paw flinching or other assays of simple limb withdrawal from a noxious stimulus. While these studies have proven invaluable in developing an appreciation of the neurobiology and pharmacology of nociceptive pathways, they fail to measure many clinically important aspects of pain (reviews, Vierck et al., 2008; Negus et al., 2006). Pain produces a number of behavioral modifications other than withdrawal from noxious stimuli, such as avoidance of normal activities including walking, household chores and social interactions (Ostelo and de Vet, 2005). In laboratory animals, post-operative pain suppresses a number of behaviors including spontaneous locomotion, feeding and social interaction (Flecknell, 1994; Karas, 2002). Intraperitoneal injection of the irritant acetic acid will suppress consumption of a palatable liquid in diet in mice, an effect reversed by morphine (Stevenson et al., 2002). Similarly, post-operative pain reduces locomotor activity and operant responding for sucrose pellets in rats, effects that are reversed by both opioid and non-opioid analgesics (Martin et al., 2004). These procedures differ from reflexive withdrawal assays in that analgesics increased pain-suppressed behaviors rather than reduce reflexive withdrawal, and additionally the range of effective doses of analgesics in the studies cited above are comparable to clinically-effective doses. In addition to suppression of normal social behavior, a troublesome symptom to treat pharmacologically is pain at rest, or spontaneous pain that occurs in the absence of an external noxious stimulus (Backonja and Stacey, 2004). This is the symptom that many patients report to the clinic for treatment and for which opioids are particularly effective. In the clinic, pain at rest is typically assessed using visual analog scales or similar devices. The challenge for basic scientists is to develop laboratory methods that display a pharmacology consistent with relief of spontaneous pain clinically, as test subjects in the laboratory are non-verbal.

The presence of pain alters conditioned place-preference with opioid administration

Conditioned place-preference is a laboratory procedure that indirectly assesses the reinforcing effects of drugs. This procedure involves pairing one of two distinct environments with passive drug injections during conditioning sessions, and allowing the animal to choose between the two environments during test sessions. Injection of reinforcing drugs typically results in a conditioned preference for the drug-paired environment. Using such methods, induction of inflammation in the hindpaw of rats with formalin or carrageenan diminishes the place preference produced by morphine, suggesting that morphine becomes less reinforcing with inflammatory pain (Suzuki et al., 2001). Similar findings were reported in rats following partial sciatic nerve ligation and were associated with an attenuation of morphine-stimulated dopamine release in limbic forebrain (Ozaki et al., 2002). Sciatic nerve ligation produces similar behavioral effects in mice, and the reduction in morphine’s ability to engender place-preference conditioning is associated with an increase in G-protein-receptor-coupled kinase 2 and a decrease in p38 signaling in the ventral tegmental area of the limbic system (Ozaki et al., 2003, 2004). These studies indicate that the presence of pain alters the indirect reinforcing effects of morphine in rodents, and suggests potential supraspinal mechanisms.

Pharmacology of opioid self-administration in the presence of pain

There have been relatively few studies that have assessed the influence of pain on opioid intake through self-administration. Equivocal findings have been reported for the effects of chronic arthritis on opioid intake in rats. Induction of arthritis reduces self-administration of morphine in rats relative to sham treatment, and effect that persists for several days consistent with the arthritic response (Lyness et al., 1989). Others found that adjuvant-induced arthritis increased oral fentanyl self-administration in a manner consistent with the disease progression and suggested that fentanyl intake could be used as an indicator of nociceptive pain in this model (Colpaert et al., 2001). One problem with adjuvant-induced arthritis is the duration of the pain model, which may be too limited to test long-term therapies designed to alter opioid tolerance with time.

In our laboratory, we sought to determine if stable neuropathic pain would alter opiate self-administration (Martin et al., 2007). We utilized the spinal nerve ligation model of Kim and Chung (1992) because this model produces long-lasting hypersensitivity to mechanical and thermal stimuli and also produces behavioral symptoms in rats thought to be related to the presence of spontaneous pain. The pharmacology of many clinically useful drugs has also been studied fairly extensively in this model using simple assays of reflexive withdrawal. Not all opioids were found to be equally efficacious in nerve-injured rats, both in reversing hypersensitivity and in maintaining self-administration. Of several opioids examined, heroin and methadone were found to be relatively more efficacious in reversing hypersensitivity of the hindpaw to mechanical stimulation and in maintaining self-administration in nerve-injured rats. An interesting finding was that only doses of these two drugs that produced significant reversal of hypersensitivity would maintain self-administration following nerve injury, while lower doses of both drugs maintained self-administration in normal rats. This suggests that in the presence of chronic pain, reversal of nociception may be the primary stimulus modulating opioid intake.

Another issue related to opioids and neuropathic pain is how to model spontaneous pain in non-verbal laboratory subjects, and whether opioid self-administration may be mediated in part by inhibition of spontaneous pain in spinal nerve-ligated rats. To test this hypothesis, clonidine or adenosine were administered intrathecally to rats trained to self-administer heroin. Clinically, intrathecal clonidine but not adenosine relieves spontaneous neuropathic pain while both drugs are effective against tactile hypersensitivity (Eisenach et al., 2003, 1995). Interestingly clonidine but not adenosine decreased heroin self-administration, and only in nerve-ligated rats. Although clonidine can produce sedation, it’s administration produced no change in the behavior of sham-ligated rats, suggesting that diminished opioid intake was not due to sedation. These data suggest that rats with neuropathic pain trained to self-administer heroin are titrating analgesia, and primarily to a stimulus related to spontaneous pain. Another conclusion could be that chronic pain, if left untreated or under treated, will result in an increase in opioid-seeking behaviors in patients. It is our hope that this model will prove useful for identifying novel strategies to minimize opioid dose requirements for the treatment of chronic pain and thereby diminish the problems associated with long term use of high doses of opioids clinically.

Intrathecal drug self-administration in the presence of pain

There have been recent reviews that indicate PCEA (patient-controlled epidural anesthesia) is a potentially more efficacious and equally safe mode of pain management as PCA (Misaskowski, 2005; Alon et al., 2003). Intrathecal self-administration of morphine increases when noxious stimulation is applied to rats and responding maintained by morphine is greater than that with saline (Dib, 1985). In our laboratory, we were interested to see if intrathecal self-administration could be studied in spinal nerve-ligated rats (Martin et al., 2006). Clonidine maintained self-administration intrathecally in spinal nerve ligated rats only over a range of doses that reversed tactile hypersensitivity in these animals (Martin et al., 2006). Responding maintained by intrathecal infusions of clonidine extinguished over a few days when either saline or clonidine with the alpha2 adrenergic receptor antagonist idazoxan was substituted for clonidine alone (Martin et al., 2006). The total dose of clonidine self-administered daily rapidly increased over the first 2–3 days of access, which could indicate either the development of tolerance or acquisition of conditioned operant behavior. The total dose of clonidine self-administered was significantly higher than would be expected based upon the time course of reversal of hypersensitivity in nerve-injured rats however, suggesting that rats are either becoming tolerant quickly or that operant responding is maintained by some other subjective effect of clonidine. In separate studies with Dr. Steven Childers’ laboratory, we have found that exposure to clonidine self-administration produces rapid desensitization of alpha2 adrenergic receptors in spinal cord, consistent with the idea that tolerance to intrathecal clonidine develops rapidly and results in substantial dose escalation (unpublished observations).

Future directions

The literature cited above generally speaks to the concept that the presence of pain alters both spinal and supraspinal neuronal activity, and provides proof of principle that these changes translate into a unique pharmacology of drug self-administration in rats in the presence of pain. The challenge is to synthesize this wealth of electrophysiological, neurochemical and pharmacological information into a cohesive strategy for investigating ways to improve conventional opioid or non-opioid therapy for chronic pain. The chief clinical challenge for chronic pain treatment, particularly pain of neuropathic origin, is to find efficacious alternatives to high doses of opioids. The incentives include minimizing side effects, reducing the development of tolerance, and providing less opportunity for diversion of medication for recreational use.

Proper use of drug self-administration techniques in rodents potentially has some advantages in accomplishing these goals over typical reflexive withdrawal assays of hypersensitivity or nociception. One advantage is that it appears that opioid self-administration is responsive to treatments that alleviate both spontaneous and elicited pain in the clinic, while mechanical allodynia is solely a measure of elicited hypersensitivity. Another advantage is that tolerance can be assessed using drug self-administration, while allowing the animal to escalate their drug intake at their own preferred rate rather than forcing tolerance by a predetermined dosing schedule (Martin et al., 2007). Another question that can be asked is whether the presence of pain alters the neuronal substrates that modulate drug-seeking behavior, such that it may be possible to develop novel treatments that minimize opioid usage selectively in chronic pain patients. The issue of addiction with chronic treatment of opioids continues to be a concern for clinicians and patients alike. The use of drug self-administration techniques have been used to assess addiction liability in normal rodents for decades, and in combination with chronic pain models can hopefully be used as a tool to develop novel therapies with less abuse liability and potential for producing physical dependence. Future studies using drug self-administration in laboratory animals in the presence of chronic pain will hopefully determine the ultimate utility of these methods as tools for drug development and investigation of novel treatment strategies.

Acknowledgments

TJM supported in part by NIDA grant DA-022599. EE supported by NIDA training grant T32-DA-007246 (SR Childers, PI).

References

- Abraham KE, McGinty JF, Brewer KL. Spinal and supraspinal changes in opioid mRNA expression are related to the onset of pain behaviors following excitotoxic spinal cord injury. Pain. 2001;90:181–190. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00402-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alon E, Jaquenod M, Schaeppi B. Post-operative epidural versus intravenous patient-controlled analgesia. Minerva Anesthesiol. 2003;69:443–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin KL, Stapleton JV, Mather LE. Relationship between blood meperidine concentrations and analgesic response: a preliminary report. Anesthesiol. 1980;53:460–466. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198012000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ator NA, Griffiths RR. Principles of drug abuse liability assessment in laboratory animals. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;70:S55–S72. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backonja MM, Stacey B. Neuropathic pain symptoms relative to overall pain rating. J. Pain. 2004;5:491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bencherif B, Fuchs PN, Sheth R, Dannals RF, Campbell JN, Frost JJ. Pain activation of human supraspinal opioid pathways as demonstrated by [11C]-carfentanil and positron emission tomography (PET) Pain. 2002;99:589–598. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00266-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird GC, Lash LL, Han JS, Zou X, Willis WD, Neugebauer V. Protein kinase A-dependent enhanced NMDA receptor functionin pain-related synaptic plasticity in rat amygdala neurones. J. Physiol. 2005;564:907–921. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.084780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brog JS, Salyapongse A, Deutch AY, Zahm DS. The pattern of afferent innervation of the core and shell in the “accumbens” part of the ventral striatum: immunohistochemical detection of retrogradely transported fluoro-gold. J. Comp. Neurol. 1993;338:255–278. doi: 10.1002/cne.903380209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey KL, Svensson P, Morrow TJ, Raz J, Jone C, Minoshima S. Selective opiate modulation of nociceptive processing in the human brain. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:525–533. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.1.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C, Shyu BC. An fMRI study of brain activations during non-noxious and noxious electrical stimulation of the sciatic nerve of rats. Brain Res. 2001;897:71–81. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colpaert FC, Tarayre JP, Alliaga M, Bruins Slot LA, Attal N, Koek W. Opiate self-administration as a measure of chronic nociceptive pain in arthritic rats. Pain. 2001;91:33–45. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00413-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colpaert FC, Meert T, De Witte P, Schmitt P. Further evidence validating adjuvant arthritis as an experimental model of chronic pain in the rat. Life Sci. 1982;31:67–75. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90402-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlstrom B, Tamsen A, Paalzow L, Hartvig P. Patient-controlled analgesic therapy, part IV: Pharmacokinetics and analgesic plasma concentrations of morphine. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1982;7:266–279. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198207030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dib B. A study of intrathecal self-injection of morphine by rats, and the difficulties entailed. Pain. 1985;23:177–185. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(85)90058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenach JC, Rauck RL, Curry R. Intrathecal, but not intravenous adenosine reduces allodynia in patients with neuropathic pain. Pain. 2003;105:65–70. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenach JC, DuPen S, Dubois M, Miguel R, Allin D. Epidural clonidine analgesia for intractable cancer pain. The Epidural Clonidine Study Group. Pain. 1995;61:391–399. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00209-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdos B, Lacza Z, Toth IE, Szelke E, Mersich T, Komjati K, Palkovits M, Sandor P. Mechanisms of pain-induced local cerebral blood flow changes in the rat sensory cortex and thalamus. Brain Res. 2003;960:219–222. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03890-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Cardinal RN, Hall J, Parkinson JA, Robbins TW. Differential involvement of amygdala subsystems in appetitive conditioning and drug addiction. In: Aggleton JP, editor. The amygdala: Ed. 2, A functional analysis. New York: Oxford Univ Press; 2000. pp. 353–390. [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Parkinson JA, Olmstead MC, Arroyo M, Robledo P, Robbins TW. Associative processes in addiction and reward: the role of amygdala-ventral striatum subsystems. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1999;877:412–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields HL. Pain modulation: expectation, opioid analgesia and virtual pain. Prog. Brain Res. 2000;122:245–253. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)62143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan TF, Chen SR, Pan HL. Mu-opioid receptor activation inhibits GABAergic inputs to the basolateral amygdala neurons through Kv1.1/1.2 channels. J. Neurophysiol. 2006;95:2032–2041. doi: 10.1152/jn.01004.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flecknell PA. Refinement of animal use – assessment and alleviation of pain. Lab. Anim. 1994;28:222–231. doi: 10.1258/002367794780681660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnier M, Zaratin PF, Ficalora G, Valente M, Fontanella L, Rhee M-H, Blumer KJ, Scheideler MA. Up-regulation of regulator of G protein signaling 4 expression in a model of neuropathic pain and insensitivity to morphine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003;304:1299–1306. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.043471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gescuk BD, Lang S, Kornetsky C. Chronic escapable footshock causes a reduced response to morphine in rats as assessed by local cerebral metabolic rates. Brain Res. 1995;701:279–287. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grass JA. Patient-controlled analgesia. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2005;101:S44–S61. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000177102.11682.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gureje O. Comorbidity of pain and anxiety disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2008;10:318–322. doi: 10.1007/s11920-008-0051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gureje O. Psychiatric aspects of pain. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2007;20:42–46. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328010ddf4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JS, Li W, Neugebauer V. Critical role of calcitonin gene-related peptide 1 receptors in the amygdala in synaptic plasticity and pain behavior. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:10717–10728. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4112-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmstetter FJ, Tershner SA, Poore LH, Bellgowan PS. Antinociception following opioid stimulation in the basolateral amygdala is expressed through the periaqueductal gray and rostral ventromedial medulla. Brain Res. 1998;779:104–118. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemby SE, Co C, Koves TR, Smith JE, Dworkin SI. Differences in extracellular dopamine concentrations in the nucleus accumbens during response-dependent and response-independent cocaine administration in the rat. Psychopharmacol. 1997;133:7–16. doi: 10.1007/s002130050365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudcova J, McNicol E, Quah C, Lau J, Carr DB. Patient controlled opioid analgesia versus conventional opioid analgesia for postoperative pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006;4:CD003348. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003348.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs EH, Smith AB, de Vries TJ, Schoffelmeer AN. Neuroadaptive effects of active versus passive drug administration in addiction research. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2003;24:566–573. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs EH, Smith AB, de Vries TJ, Schoffelmeer AN. Long-term gene expression in the nucleus accumbens following heroin administration is subregion-specific and depends on the nature of drug administration. Addiction Biol. 2005;10:91–100. doi: 10.1080/13556210412331284748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang YJ, Eisenach JC. Intrathecal clonidine reduces hypersensitivity after nerve injury by a mechanism involving spinal m4 muscarinic receptors. Anesth. Analg. 2003;96:1403–1408. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000060450.80157.FF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karas AZ. Postoperative analgesia in the laboratory mouse, Mus musculus. Lab Anim. (NY) 2002;31:49–52. doi: 10.1038/5000175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Chung JM. An experimental model for peripheral neuropathy produced by segmental spinal nerve ligation in the rat. Pain. 1992;50:355–363. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman KA, Gerhard A, Horrichs-Haermeyer G, Grond S, Zech D. Postoperative patient-controlled analgesia with sufentanil: analgesic efficacy and minimum effective concentrations. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 1991;35:221–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1991.tb03277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman KA, Heinrich C, van Heiss R. Balanced anesthesia and patient-controlled postoperative analgesia with fentanyl: minimum effective concentrations, accumulation and acute tolerance. Acta Anaesthesiol. Belg. 1988;39:11–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyness WH, Smith FL, Heavner JE, Iocano CU, Garvin RD. Morphine self-administration in the rat during adjuvant-induced arthritis. Life Sci. 1989;45:2217–2224. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(89)90062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W, Hatzis C, Eisenach JC. Intrathecal injection of cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) antisense oligonucleotide attenuates tactile allodynia caused by partial sciatic nerve ligation. Brain Res. 2003;988:97–104. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03348-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W, Quirion R. Increased phosphorylation of cyclic AMP response element-binding protein (CREB) in the superficial dorsal horn neurons following partial sciatic nerve ligation. Pain. 2001;93:295–301. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00335-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao J, Mayer DJ, Price DD. Patterns of increased brain activity indicative of pain in a rat model of peripheral mononeuropathy. J. Neurosci. 1999;13:2689–2702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-06-02689.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks RM, Sachar EJ. Undertreatment of medical inpatients with narcotic analgesics. Ann. Intern. Med. 1973;78:173–181. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-78-2-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin TJ, Kim SA, Buechler NL, Porreca F, Eisenach JC. Opioid self-administration in the nerve-injured rat: relevance of antiallodynic effects to drug consumption and effects of intrathecal analgesics. Anesthesiol. 2007;106:312–322. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200702000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin TJ, Kim SA, Eisenach JC. Clonidine maintains intrathecal self-administration in rats following spinal nerve ligation. Pain. 2006;125:257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin TJ, Eisenach JC. Pharmacology of opioid and nonopioid analgesics in chronic pain states. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001;299:811–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin TJ, Buechler NL, Kahn W, Crews JC, Eisenach JC. Effects of laparotomy on spontaneous exploratory activity and conditioned operant responding in the rat: a model for postoperative pain. Anesthesiol. 2004;101:191–203. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200407000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaugh JL. Memory-a century of consolidation. Science. 2000;287:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5451.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miaskowski C. Patient-controlled modalities for acute post-operative pain management. J. Perianesth. Nurs. 2005;20:255–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miletic G, Pankratz MT, Miletic V. Increases in the phosphorylation of cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREB) and decreases in the content of calcineurin accompany thermal hyperalgesia following chronic constriction injury in rats. Pain. 2002;99:493–500. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00242-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogil JS, Crager SE. What should we be measuring in behavioral studies of chronic pain in animals? Pain. 2004;112:12–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morilak DA, Barrera G, Echevarria DJ, Garcia AS, Hernandez A, Ma S, Petre CO. Role of brain norepinephrine in the behavioral response to stress. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29:1214–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita M, Kuzumaki N, Suzuki M, Narita M, Oe K, Yamazaki M, Yajima Y, Suzuki T. Increased phosphorylated-mu-opioid receptor immunoreactivity in the mouse spinal cord following sciatic nerve ligation. Neurosci. Lett. 2004;354:148–152. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.09.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita M, Ozaki S, Narita M, Ise Y, Yajima Y, Suzuki T. Change in the expression of c-fos in the rat brain following sciatic nerve ligation. Neurosci. Lett. 2003;352:231–233. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negus SS, Vanderah TW, Brandt MR, Bilsky EJ, Becerra L, Borsook D. Preclinical assessment of candidate analgesic drugs: recent advances and future challenges. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006;319:507–514. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.106377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer V, Li W, Bird GC, Bhave G, Gereau RW., 4th Synaptic plasticity in the amygdala in a model of arthritic pain: differential roles of metabotropic glutamate receptors 1 and 5. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:52–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-01-00052.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi K, Kawai Y, Fukuoka T, Senba E, Miki K. Substance P induced by peripheral nerve injury in primary afferent sensory neurons and its effect on dorsal column nucleus neurons. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:7633–7643. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-11-07633.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostelo RW, de Vet HC. Clinically important outcomes in low back pain. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2005;19:593–607. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki S, Narita M, Narita M, Ozaki M, Khotib J, Suzuki T. Role of extracellular signal-regulated kinase in the ventral tegmental area in the suppression of the morphine-induced rewarding effect in mice with sciatic nerve ligation. J. Neurochem. 2004;88:1389–1397. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki S, Narita M, Narita M, Iino M, Miyoshi K, Suzuki T. Suppression of the morphine-induced rewarding effect and G-protein activation in the lower midbrain following nerve injury in the mouse: involvement of G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 2. Neurosci. 2003;116:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00699-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki S, Narita M, Narita M, Iino M, Sugita J, Matsumura Y, Suzuki T. Suppression of the morphine-induced rewarding effect in the rat with neuropathic pain: implication of the reduction in mu-opioid receptor functions in the ventral tegmental area. J. Neurochem. 2002;82:1192–1198. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan HL, Chen SR, Eisenach JC. Intrathecal clonidine alleviates allodynia in rats: interaction with spinal muscarinic and nicotinic receptors. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:509–514. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199902000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson JK, Hongpaisan J, Molander C. C-fos expression in gracilothalamic tract neurons after electrical stimulation of the injured sciatic nerve in the adult rat. Somatosens. Mot. Res. 1993;10:475–483. doi: 10.3109/08990229309028852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic P, Kalso E, Petersson KM, Ingvar M. Placebo and opioid analgesia-imaging a shared neuronal network. Science. 2002;295:1737–1740. doi: 10.1126/science.1067176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron R, Laurent B, Garcia-Larrea L. Functional imaging of brain responses to pain. A review and meta-analysis. Neurophysiol. Clin. 2000;30:263–288. doi: 10.1016/s0987-7053(00)00227-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkanen A, Savander M, Nurminen N, Ylinen A. Intrinsic synaptic circuitry of the amygdala. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2003;985:34–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porreca F, Burgess SE, Gardell LR, Vanderah TW, Malan TP, Jr, Ossipov MH, Lappi DA, Lai J. Inhibition of neuropathic pain by selective ablation of brainstem medullary cells expressing the mu-opioid receptor. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:5281–5288. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05281.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porro CA, Cavazzuti M, Lui F, Giuliani D, Pellegrini M, Baraldi P. Independent time courses of supraspinal nociceptive activity and spinally mediated behavior during tonic pain. Pain. 2003;104:291–301. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porro CA, Cavazzuti M, Baraldi P, Giuliani D, Panerai AE, Corazza R. Central nervous system pattern of metabolic activity during tonic pain: evidence for modulation by beta-endorphin. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999;11:874–888. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price JL. Comparative aspects of amygdala connectivity. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2003;985:50–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przewlocka B, Sieja A, Starowicz K, Maj M, Bilecki W, Przewlocki R. Knockdown of spinal opioid receptors by antisense targeting β-arrestin reduces morphine tolerance and allodynia in rat. Neurosci. Lett. 2002;325:107–110. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00246-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez Parkitna JM, Bilecki W, Mierzejewski P, Stefanski R, Ligeza A, Bargiela A, Ziolkowska B, Kostowski W, Przewlocki R. Effects of morphine on gene expression in the rat amygdala. J. Neurochem. 2004;91:38–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortland P, Molander C. The time-course of abeta-evoked c-fos expression in neurons of the dorsal horn and gracile nucleus after peripheral nerve injury. Brain Res. 1998;810:288–293. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00940-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JE, Vaughan TC, Co C. Acetylcholine turnover rates in rat brain regions during cocaine self-administration. J. Neurochem. 2004;88:502–512. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JE, Koves TR, Co C. Brain neurotransmitter turnover rates during intravenous cocaine self-administration. Neurosci. 2003;117:461–475. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00819-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JE, Co C, Lane JD. Limbic acetylcholine turnover rates correlated with rat morphine-seeking behaviors. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1984;20:429–442. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(84)90282-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JE, Co C, Freeman ME, Lane JD. Brain neurotransmitter turnover correlated with morphine-seeking behavior of rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1982;16:509–519. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(82)90460-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JE, Co C, Freeman MH, Sands MP, Lane JD. Neurotransmitter turnover in rat striatum is correlated with morphine self-administration. Nature. 1980;287:152–154. doi: 10.1038/287152a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanski R, Ziolkowska B, Kusmider M, Mierzejewski P, Wyszogrodzka E, Kolomanska P, Dziedzicka-Wasylewska M, Przewlocki R, Kostowski W. Active versus passive cocaine administration: differences in the neuroadaptive changes in the brain dopaminergic system. Brain Res. 2007;1157:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.04.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanski R, Ladenheim B, Lee SH, Cadet JL, Goldberg SR. Neuroadaptations in the dopaminergic system after active self-administration but not after passive administration of methamphetamine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999;439:123–135. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson GW, Bilsky EJ, Negus SS. Targeting pain-suppressed behaviors in preclinical assays of pain and analgesia: effects of morphine on acetic acid-suppressed fedding in C57BL/6J mice. J. Pain. 2006;7:408–416. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.01.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Kishimoto Y, Ozaki S, Narita M. Mechanism of opioid dependence and interaction between opioid receptors. Eur. J. Pain. 2001;(5) suppl A:63–65. doi: 10.1053/eujp.2001.0282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamsen A, Hartvig P, Fagerlund C, Dahlstrom B. Patient-controlled analgesic therapy, part II: Individual analgesic demand and analgesic plasma concentrations of pethidine in postoperative pain. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1982;7:164–175. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198207020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tershner SA, Helmstetter FJ. Antinociception produced by mu opioid receptor activation in the amygdala is partly dependent on activation of mu opioid and neurotensin receptors in the periaqueductal gray. Brain Res. 2000;865:17–26. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02179-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungless MA, Magill PJ, Bolam JP. Uniform inhibition of dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area by aversive stimuli. Science. 2004;303:2040–2042. doi: 10.1126/science.1093360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vierck CJ, Hansson PT, Yezierski RP. Clinical and pre-clinical pain assessment: are we measuring the same thing? Pain. 2008;135:7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff M, Crane P, Lane M, Miglioretti DL, Simon G, Saunders K, Stang P, Brandenburg N, Kessler R. Chronic spinal pain and physical-mental comorbidity in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Pain. 2005;113:331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walder B, Schafer M, Henzi I, Tramer MR. Efficacy and safety of patient-controlled opioid analgesia for acute postoperative pain. Acta. Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2001;45:795–804. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2001.045007795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright CI, Beiger AVJ, Groenewegen HJ. Basal amygdaloid complex afferents to the rat nucleus accumbens are compartmentally organized. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:1877–1893. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01877.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubieta J-K, Smith YR, Bueller JA, Xu Y, Kilbourn MR, Jewett DM, Meyer CR, Koeppe RA, Stohler CS. Regional mu opioid receptor regulation of sensory and affective dimensions of pain. Science. 2001;293:311–315. doi: 10.1126/science.1060952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]