Abstract

Background

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is a prevalent condition with underexplored risk factors.

Objectives

To determine CRS incidence and evaluate associations with a range of pre-morbid medical conditions for CRS without nasal polyps (CRSsNP) and CRS with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) using real-world clinical practice data.

Methods

Electronic health record (EHR) data from 446,480 Geisinger Clinic primary care patients was used for a retrospective longitudinal cohort study for data from 2001–2010. Using logistic regression, newly diagnosed CRS cases between 2007-2009 were compared to frequency-matched controls on pre-morbid factors in the immediate (0-6 months), intermediate (7-24 months) and entire observed timeframes prior to diagnosis.

Results

: The average incidence of CRS was 83 (±13) CRSwNP cases per 100,000 person-years and 1048 (±78) CRSsNP cases per 100,000 person-years. Between 2007-2009, 595 patients with incident CRSwNP and 7523 patients with incident CRSsNP were identified and compared to 8118 controls. Compared to controls and CRSsNP, CRSwNP patients were older and more likely to be male. Prior to diagnosis, CRS patients had a higher prevalence of acute rhinosinusitis, allergic rhinitis, chronic rhinitis, asthma, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), adenotonsillitis, sleep apnea, anxiety and headaches (all p < 0.001). CRSsNP had a higher pre-morbid prevalence of infections of the upper and lower airway, skin/soft tissue and urinary tract (all p < 0.001). In the immediate and intermediate timeframes analyzed, patients who developed CRS had more outpatient encounters and antibiotic prescriptions (p < 0.001) but guideline-recommended diagnostic testing was performed in a minority of cases.

Conclusions

Patients who are diagnosed with CRS have a higher pre-morbid prevalence of anxiety, headaches, GERD, sleep apnea and infections of the respiratory system and some non-respiratory sites that results in higher antibiotic, corticosteroid and health care utilization. The use of guideline-recommended diagnostic testing for confirmation of CRS remains poor.

Keywords: epidemiology, incidence, sinusitis, nasal polyps, risk factors, asthma, rhinitis, nested case-control study, antibiotics, diagnosis

Background

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is a prevalent inflammatory condition of the paranasal sinuses that encompasses two clinically distinct entities: chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyposis (CRSsNP) and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis (CRSwNP)(1, 2). In this paper, “CRS” refers to both the CRSsNP and CRSwNP entities. Current estimates using patient self-reported histories (NHIS survey data) of “sinusitis” report a prevalence of 13% in the US(3) and chronicity is defined by the American and European consensus statements as the presence of paranasal sinus inflammation for a minimum of 3-months(4, 5). Prior epidemiologic evidence suggests that CRS is prevalent among patients with asthma, immunodeficiency and cystic fibrosis(6, 7) but it remains unclear whether CRSsNP and CRSwNP are distinct conditions with unique epidemiologic characteristics. Currently proposed etiologies for both forms include genetic predisposition, innate immune deficits, acquired pathogens, inhaled allergens or irritants, or systemic adaptive immune dysregulation(8, 9).

Surprisingly, the epidemiology and pre-morbid conditions that may be associated with the diagnosis of CRS remain underexplored with most prior relevant studies limited by small sample size, utilization of specialty-specific patient populations, short observation periods, use of self-reported “sinusitis”, failure to distinguish acute and chronic forms of sinusitis, and lack of comparison subjects(6, 10, 11). Thus, the incidence of CRS and associations of a range of pre-morbid conditions before diagnosis of CRS and their relative strengths of associations remain unknown. While a prospective, longitudinal study examining childhood and adult determinants of CRS would be ideal, challenges to such an approach include the variable latency period of CRSsNP and CRSwNP, the current lack of knowledge about which specific exposures or populations with high prevalence may be most suitable to study, and time and cost considerations.

The widespread adoption of EHR by large health-care delivery systems facilitates the ability to longitudinally evaluate health care utilization of CRS patients prior to and following diagnosis. In this study, we analyzed data from the Geisinger Clinic that serves a large primary care population. The population is representative of the real world of clinical practice in primary care and of the general population in the region. The Geisinger Clinic, in particular, has up to 10 years of longitudinal data in the EHR. The goal of this study was to evaluate whether patients who eventually received a diagnosis of CRSsNP or CRSwNP were more likely to have a history of specific pre-morbid illnesses when compared to control patients without chronic sinonasal disease. If such a pattern of pre-morbid illness exists, the nature of the pre-morbid diseases, impact and magnitude of each risk factor could be instructive in improving our understanding of causes and mechanisms and allow for the development of preventive interventions targeted toward at-risk populations. More generally, we also evaluated patterns of healthcare utilization and treatment before diagnosis and approaches to diagnosis in this population.

Methods

Study overview

We used longitudinal data from the EHR of patients with a Geisinger Clinic primary care provider, and first calculated annual incidence rates from 2001 to 2009 then completed a nested case-control analysis. The goals were to: (1) describe the epidemiology of CRS; (2) compare the prevalence and timing of pre-morbid illnesses preceding incident CRSwNP and CRSsNP compared to controls; (3) compare healthcare and antibiotic utilization among patients with CRSwNP and CRSsNP compared to controls; and (4) evaluate CT and nasal endoscopy utilization in these general population-representative primary care patients. The control group was group-matched on age, gender and visit frequency to the combined CRS populations. Institutional Review Boards (IRB) at both the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the Geisinger Health System approved this study.

Study population and design

Data were obtained for 446,480 patients of the Geisinger Clinic, who had a Geisinger primary care provider, from January 1, 2001 to February 9, 2010. EHR outpatient encounter records were available over this full time frame, while inpatient records were only available after July 1, 2003. The Geisinger Clinic provides primary care and specialty services via 41 community practice clinics and four hospitals in a 31-county region of central and northeastern Pennsylvania. The general population in this area is stable. Census data indicate that with the exception of two counties, the out-migration rate is less than 1% per year. The primary care population is representative of the region's population (in an analysis comparing Geisinger Clinic patients with NHANES subjects on sociodemographic characteristics, unpublished data).

Data Sources

EHR data were obtained on demographics, clinical measures, problem list, medical history, and medication history; encounters (e.g. office visits, hospitalizations, nurse encounters, telephone inquiries and specialty consultations); orders (e.g. medications, imaging and procedures); imaging (e.g. MRI, CT, X-ray); and associated International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9) codes (and when used, Geisinger system [EP] codes). Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes were used to record encounters and procedures.

Identification of CRSsNP cases, CRSwNP cases and controls

For the longitudinal study, diagnosed cases occurring between the years 2001 and 2009 were identified for chronic rhinosinusitis (CRSsNP, ICD-9 473.X) and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP, ICD-9 471.X). A patient was defined as having an incident diagnosis of CRS during the first year a CRS ICD-9 code was recorded in the patient's outpatient/inpatient/emergency department records. Incident cases of CRSwNP were included regardless of prior presentation with CRSsNP and recorded only in the first year CRSwNP was diagnosed. CRSsNP patients could not have a prior, or subsequent, CRSwNP diagnosis throughout the observed duration of the study. For the case-control study, newly diagnosed incident cases of CRSwNP (595 cases) and CRSsNP (7,523 cases) were defined using ICD-9 codes within the Geisinger Clinic EHR for the years 2007-2009. The analysis was constrained to the post 2007 period to allow for the potential existence of a full five (5) years of patient records within the EHR before the patients first presentation with CRS. A comparison control group of 8118 outpatient encounters was frequency matched to the combined CRSsNP and CRSwNP group on age strata, sex and visit year.

Analysis of pre-morbid conditions and health utilization variables

A committee comprised of four otolaryngologists and four allergist-immunologists identified a list of conditions and corresponding ICD-9 codes relevant to CRSsNP and CRSwNP patients, along with several comparison conditions (See Table 2 for codes identified). Pre-morbid conditions were analyzed for three separate time periods before CRS diagnosis or the matched control visit: the total duration under observation (2001-2009), the immediate (0-6 months) and intermediate (7-24 months) time periods before the CRS diagnosis. Pre-morbid diagnoses entered during the observed period were identified by their ICD-9 codes. Since this dataset was analyzed retrospectively and examines health care utilization at a population level, professional-society criteria were not used to define symptom complexes like asthma and GERD.

Table 2.

Associations of provider coded diagnoses with CRS case status during the entire observed duration prior to diagnosis of CRSwNP (471.X) and CRSsNP (473.X)

|

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICD-9 Codes used | CRSwNP | CRSsNP | Controls | CRSwNP vs Controls | CRSsNP vs Controls | |

| Pre-morbid condition | N | N | N | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

|

|

||||||

| Upper airway (conbined)† | 486 (81.7) | 6,451 (85.8) | 5,627 (69.3) | 2.2 (1.8-2.8)* | 2.7 (2.5-2.9)* | |

| Acute rhinosinusitis (%) | 461.X | 339 (57.0) | 5,061 (67.3) | 3,191 (39.3) | 2.2 (1.8-2.6)* | 3.2 (3.0-3.4)* |

| Otitis media (%) | 382.X | 102 (17.1) | 1,871 (24.9) | 1,364 (16.8) | 1.8 (1.4-2.2)* | 1.8 (1.6-1.9)* |

| Acute upper respiratory tract infection (%) | 460, 462, 463, 464.X, 465.X | 266 (44.7) | 4,247 (56.5) | 3,609 (44.5) | 1.3 (1.1-1.5) | 1.6 (1.5-1.8)* |

| Allergic rhinitis (%) | 477.X | 254 (42.7) | 3,071 (40.8) | 1,841 (22.7) | 2.6 (2.2-3.1)* | 2.4 (2.2-2.5)* |

| Chronic rhinitis (%) | 472.0 | 124 (20.8) | 1,325 (17.6) | 578 (7.1) | 3.5 (2.8-4.4)* | 2.8 (2.5-3.1)* |

| Post nasal drip/wheeze/cough (%) | 784.91, 786.05,07,2 | 175 (29.4) | 2,786 (37.0) | 1,946 (24.0) | 1.5 (1.2-1.8)* | 1.9 (1.8-2.0)* |

| Adenotonsillitis (%) | 474.0X, 474.1X | 11 (2.9) | 227 (3.0) | 100 (1.2) | 2.6 (1.3-4.9)* | 2.5 (1.9-3.1)* |

| Sleep apnea | 327.2X | 22 (3.7) | 156 (2.1) | 110 (1.4) | 2.2 (1.4-3.5)* | 1.6 (1.2-2.0)* |

| Lower aerodigestive tract (combined)† | 342 (57.5) | 4,656 (61.9) | 3,848 (47.4) | 1.5 (1.2-2.7)* | 1.8 (1.7-2.0)* | |

| Asthma (%) | 493.X | 142 (23.9) | 1,369 (18.2) | 916 (11.3) | 2.8 (2.3-3.5)* | 1.7 (1.6-1.9)* |

| Cystic fibrosis (%) | 277.0X | 6 (1.0) | 4 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | NC | NC |

| Pneumonia (%) | 480-6, EP458-9, 770 | 44 (7.4) | 761 (10.1) | 505 (6.2) | 1.3 (0.9-1.7) | 1.7 (1.5-1.9)* |

| Bronchitis (%) | 466.X, 490, EP275, | 212 (35.6) | 3,334 (44.3) | 2,509 (30.9) | 1.2 (1.0-1.4) | 1.7 (1.6-1.8)* |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease (%) | 530.81, EP699 | 176 (29.6) | 2,220 (29.5) | 1,666 (20.5) | 1.5 (1.2-1.8)* | 1.7 (1.6-1.8)* |

| Influenza (%) | 487.X, 488.X | 26 (4.4) | 292 (3.9) | 239 (2.9) | 1.6 (1.1-2.4) | 1.3 (1.1-1.6) |

| Epithelial conditions (combined)† | 192 (32.3) | 2,700 (35.9) | 2,410 (29.7) | 1.2 (1.0-1.4) | 1.3 (1.2-1.4)* | |

| Conjunctivitis (%) | 372.0-2X | 29 (4.9) | 471 (6.3) | 314 (3.9) | 1.6 (1.0-2.3) | 1.6 (1.4-1.9)* |

| Urinary tract infection (%) | 599 | 70 (11.8) | 941 (12.5) | 796 (9.8) | 1.3 (1.0-1.7) | 1.3 (1.2-1.5)* |

| Atopic dermatitis (%) | 691.8 | 25 (4.2) | 369 (4.9) | 291 (3.6) | 1.7 (1.1-2.5) | 1.4 (1.2-1.6)* |

| Psoriasis (%) | 696.1 | 14 (2.4) | 145 (1.9) | 131 (1.6) | 1.2 (0.7-2.2) | 1.2 (1.0-1.5) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease (%) | 555.X, 556.X | 8 (1.3) | 101 (1.3) | 83 (1.0) | 1.1 (0.5-2.3) | 1.3 (1.0-1.7) |

| Skin/soft tissue infections (%) | 035, 680.X, 681.X, 682.X, 684, 686.9 | 99 (16.6) | 1,370 (18.2) | 1,301 (16.0) | 1.0 (0.8-1.3) | 1.2 (1.1-1.3)* |

| Systemic autoimmune disease (combined)† | 9 (1.5) | 145 (1.9) | 100 (1.2) | 1.2 (0.6-2.4) | 1.6 (1.2-2.1)* | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosis (%) | 710.0, EP212-7, EP611,EP621 | 3 (0.5) | 26 (0.3) | 13 (0.2) | 3.6 (1.0-12.8) | 2.2 (1.1-4.3) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (%) | 714.X | 7 (1.2) | 121 (1.6) | 89 (1.1) | 1.0 (0.5-2.2) | 1.5 (1.1-2.0) |

| Other selected general medical conditions (combined)† | 162 (27.2) | 1,887 (25.1) | 2,066 (25.5) | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | |

| Diabetes Mellitus (%) | 250.X, EP205,206 | 64 (10.8) | 741 (9.8) | 862 (10.6) | 0.8 (0.6-1.0) | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) |

| Obesity (%) | 278.01-2; EP8902V85.3x,4,5x; 649.1x, | 90 (15.1) | 947 (12.6) | 954 (11.8) | 1.2 (1.0-1.6) | 1.0 (0.9-1.2) |

| Tobacco use (%) | 305.1X, 649.0-4, 989.84 | 29 (4.9) | 329 (4.4) | 271 (3.3) | 1.2 (0.8-1.9) | 1.3 (1.1-1.6) |

| Pregnancy (%) | 650, 651.x, V22.x,V23.x,V27.x | 17 (2.9) | 325 (4.3) | 431 (5.3) | 0.6 (0.4-1.0) | 0.7 (0.6-0.9)* |

| Selected neuropsychiatric conditions (combined)† | 192 (32.3) | 2,229 (29.6) | 1,573 (19.4) | 1.9 (1.6-2.3)* | 1.8 (1.7-1.9)* | |

| Anxiety (%) | 300.0X | 42 (7.1) | 482 (6.4) | 316 (3.9) | 1.7 (1.2-2.4) | 1.7 (1.5-2.0)* |

| Depression (%) | 311 | 32 (5.4) | 400 (5.3) | 354 (4.4) | 1.1 (0.8-1.6) | 1.3 (1.1-1.5) |

| Headache (%) | 339.X, 346.X, 784.0 | 162 (27.2) | 1,846 (24.5) | 1,235 (15.2) | 2.1 (1.7-2.6) | 1.8 (1.7-2.0)* |

| Other comparison conditions (combined)† | 235 (39.6) | 2,511 (33.4) | 2,681 (33.0) | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) | 1.1 (1.0-1.2) | |

| Hypothyroidism (%) | 244.X | 67 (11.3) | 830 (11.0) | 788 (9.7) | 1.1 (0.8-1.4) | 1.1 (1.0-1.3) |

| Colon cancer (%) | 153.X | 6 (1.0) | 30 (0.4) | 48 (0.6) | 1.3 (0.5-3.1) | 0.7 (0.4-1.1) |

| Essential hypertension (%) | 401.X | 198 (33.3) | 2,086 (27.7) | 2,255 (27.8) | 0.9 (0.7-1.1) | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) |

| Heart Failure (%) | 428.0 | 19 (3.2) | 206 (2.7) | 213 (2.6) | 0.9 (0.5-1.5) | 1.1 (0.9-1.3) |

p < 0.0005. Logistic regression was used to derive adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals controlling for race/ethnicity, sex, and age.

Contains the combined prevalence and aOR of all diagnoses listed under each category‥ NC indicates models did not converge.

For these time periods, the number of outpatient, inpatient and emergency room encounters for any indication were compared between cases and controls. For medications, a list of orally administered antibiotics, nasally administered corticosteroids and orally administered corticosteroids was created and the indications associated with each prescribed antibiotic were compared. The use of sinus computed tomography (CT)-scans and airway endoscopy for diagnosis was evaluated. We defined the use of airway endoscopy as any patient who had a diagnostic nasal endoscopy (CPT 31231), flexible laryngoscopy (CPT 31575) or an endoscopic nasopharyngoscopy (CPT 92511) for any indication. Sinus CT scan was identified with CPT code 70486. For these diagnostic tests, we evaluated from one year before to three months after CRS diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

For incidence data, any patient with an inpatient or outpatient encounter in a given calendar year contributed one person-year to the incidence rate denominator. Rates are presented as the number of incident cases per 100,000 person-years. In unadjusted analyses, the two case groups and controls were compared on demographics, healthcare utilization, pre-morbid conditions, and antibiotic use. SPSS (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) was used for contingency tables (chi-square test) for categorical variables and one-way ANOVA (F-test) for continuous variables. To adjust for potential confounding variables in evaluating associations with pre-morbid conditions, polytomous logistic regression was used to compare CRSwNP and CRSsNP cases to controls. For the latter, we adjusted for age (< 18, 40 to < 50, 50 to < 60, 60 to < 70 and 70 years and older), sex, and race/ethnicity (white, non-white). To evaluate effect modification by age on associations of pre-morbid conditions with CRS status, additional logistic regression models were used to analyze the entire CRS group with a dummy variable in the model for age < 14 years, continuous age, and cross-products with the co-morbidities. Comorbidities were added to the base model one at a time and adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are provided. Due to the large number of comparisons in this study, we considered a conservative p-value of < 0.0005 to define statistical significance, but did not adjust p-values for multiple comparisons. Logistic regression was carried out using Stata version 11.2 (Statacorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Description of study population and annual incidence

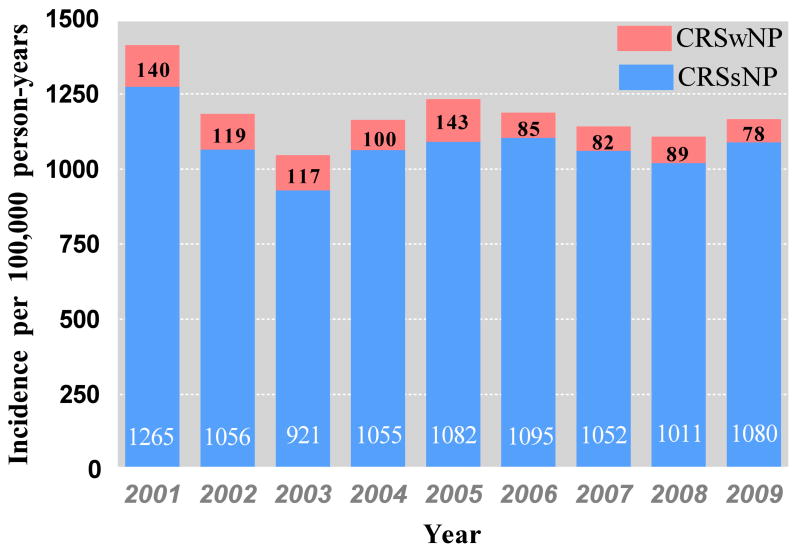

Data on 307,381 patients who received care at any time in the years 2007, 2008 and 2009 were analyzed to identify 595 incident CRSwNP cases, 7523 incident CRSsNP cases and 8118 matched controls (Table 1). The average incidence rate from 2007–2009 was 83 (±13) CRSwNP cases per 100,000 person-years and 1048 (±78) CRSsNP cases per 100,000 person-years. Comparing the study time period between 2007-2009 to the years 2001-2006, the incidence of CRSsNP was stable while the incidence of CRSwNP appeared to decline (p=0.04) (Figure1). However, since 2001 was the first year the EHR was utilized widely in the Geisinger Clinic, the incidence data presented in the earlier years likely represents both incident and prevalent CRS cases. The CRSwNP cases were older, and more likely to be male, compared to CRSsNP cases and control patients (all p < 0.0005). Season was not associated with CRSwNP onset but was highly significant for CRSsNP: adjusted odds ratios (95% CI) relative to winter for spring summer and fall were 1.2(0.9-1.4), 0.8 (0.6-1.0) and 1.0 (0.8-1.3) respectively for CRSwNP and 0.8 (0.7-0.9), 0.6 (0.5-0.6) and 0.9 (0.8-1.0) for CRSsNP. Consistent with the general population in the region, patients were predominantly white; there were no significant differences in race/ethnic composition by group. The average duration, from first encounter in the Geisinger Clinic to CRS diagnosis or index visit, among cases and controls was approximately five years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the subjects with CRSwNP (471.X), CRSsNP (473.X) and controls

|

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | CRSwNP | CRSsNP | Controls | P Value† | Eligible Patients |

|

|

|||||

| N | 595 | 7523 | 8,118 | 307,381 | |

| Age at diagnosis, years, mean (SD) | 48.4 (19.1) | 40.3 (22.9) | 41.0 (23.0) | < 0.0005 | 37.9 (24.0) |

| Age distribution, N(%) | |||||

| 0-14, N (%) | 25 (4.2) | 1,358 (18.1) | 1,426 (17.6) | < 0.0005 | 70,157 (22.8) |

| 15-24, N (%) | 52 (8.7) | 739 (9.8) | 748 (9.2) | 0.353 | 42,448 (13.8) |

| 25-34, N (%) | 67 (11.3) | 861 (11.4) | 928 (11.4) | 0.991 | 30,846 (10.0) |

| 35-44, N (%) | 100 (16.8) | 1,186 (15.8) | 1,286 (15.8) | 0.799 | 37,073 (12.1) |

| 45-54, N (%) | 137 (23.0) | 1,265 (16.8) | 1,402 (17.3) | 0.001 | 41,609 (13.5) |

| 55-64, N (%) | 81 (13.6) | 983 (13.1) | 1,064 (13.1) | 0.93 | 35,385 (11.5) |

| 65-74, N (%) | 80 (13.5) | 636 (8.5) | 636 (7.8) | < 0.0005 | 24,321 (7.9) |

| >75, N (%) | 53 (8.9) | 595 (5.6) | 628 (7.7) | 0.577 | 25,542 (8.3) |

| Gender | |||||

| Female, N (%) | 271 (45.5) | 4,377 (58.2) | 4,648 (57.3) | < 0.0005 | 164,820 (53.6) |

| Male, N (%) | 324 (54.5) | 3,146 (41.8) | 3,470 (42.7) | < 0.0005 | 142,545 (46.4) |

| Race/ethnicity (% white) | 96.3 | 94.6 | 94.3 | 0.12 | 93.1 |

| Year of diagnosis | |||||

| 2007 (%) | 186 (31.2) | 2,390 (31.7) | 2,576 (31.7) | 225,433 | |

| 2008 (%) | 212 (35.6) | 2,411 (32.0) | 2,623 (32.3) | 237,127 | |

| 2009 (%) | 197 (33.1) | 2,722 (33.1) | 2,919 (36.0) | 250,866 | |

| Observed duration (days), mean (SD) | 1,847 (954) | 1,775 (970) | 1,816 (940) | ||

For continuous variables, P values are based on one-way ANOVA for differences between the means; for categorical variables, P-values are based on Pearson's chi-square test for association.

The observed duration was the number of days between the first encounter in the Geisinger Clinic system and the date of the diagnosis.

Figure 1.

Incidence of CRSwNP and CRSsNP from 2001-2009 in the Geisinger Clinic of patients with a Geisinger primary care provider

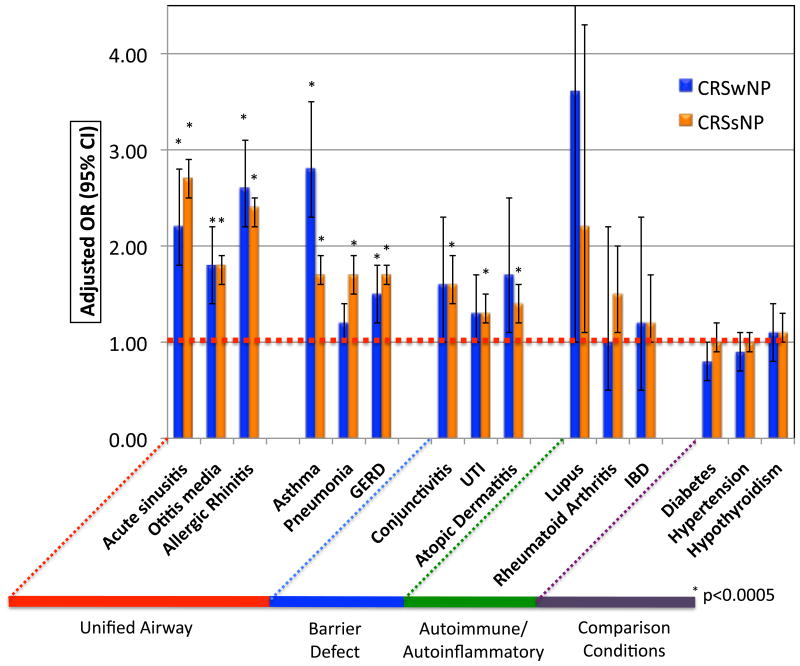

Associations of pre-morbid conditions with CRS diagnosis

After adjusting for age, sex and race, there were large differences in the occurrence of a variety of pre-morbid conditions among the three patient groups, but especially for airway diseases (Figure 2 and Table 2). Additional analysis adding season of diagnosis into the model was performed but this did not change the reported associations and these data are not further discussed. Acute rhinosinusitis, allergic rhinitis, chronic rhinitis and symptoms of post nasal drip/wheeze/cough/shortness of breath were each associated with subsequent diagnosis of CRS (all p < 0.0005). Asthma was strongly associated with subsequent diagnosis of both CRSsNP and CRSwNP, but the association was strongest with CRSwNP. Additionally, both gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), adenotonsillitis, sleep apnea and otitis media were associated with a subsequent CRS diagnosis, while upper respiratory tract infections (URI), influenza, pneumonia and bronchitis were each associated with subsequent diagnosis of CRSsNP (all p < 0.0005). Interestingly, conjunctivitis, atopic dermatitis, urinary tract infections (UTI), and skin and soft tissue infections (SSTI) were similarly associated with subsequent diagnosis of CRSsNP (all p < 0.0005).

Figure 2.

Adjusted associations comparing CRSwNP and CRSsNP with control patients (represented by the dotted red line) using selected provider coded diagnoses for the entire observed duration prior to CRS diagnosis.

In adjusted models, individual systemic or regional autoimmune or autoinflammatory diseases were not associated with subsequent diagnosis of CRS although, in combination, CRSsNP was associated with autoimmune conditions. Similarly, diabetes and obesity were not associated with subsequent CRS diagnosis. Interestingly, even after adjusting for age and sex, pregnancy (using its ICD-9 code) was associated with decreased odds of CRS diagnosis. Anxiety and headache disorders were associated with increased odds of CRS diagnosis (all p < 0.0005), but depression was not. None of our comparison conditions that were not hypothesized to be risk factors for CRS – hypertension, hypothyroidism or heart failure – were associated with its subsequent diagnosis.

Timing of pre-morbid illness

Since CRS is symptomatically defined by the persistence of symptoms for more than three months, we analyzed the timing of pre-morbid illness to separate the symptomatic prodrome expected for CRS. We compared associations in two separate periods: the immediate (0-6 months) and intermediate (7-24 month) periods preceding CRS diagnosis (Table 3). Expected and definitional diagnoses of conditions such as rhinitis, acute rhinosinusitis and URI, as well as component symptoms such as headaches, post nasal drip, were acutely elevated in the immediate period preceding CRS diagnosis (all p<0.0005). However, similar associations were also consistently observed for these conditions, in addition to, asthma, atopic dermatitis, otitis media, and GERD in the intermediate time frame preceding diagnosis (all p<0.0005). Significant associations between CRSsNP and adenotonsillitis, bronchitis, pneumonia, conjunctivitis, UTI and tobacco were also found in the intermediate time frame preceding diagnosis (all p<0.0005).

Table 3.

Associations of pre-morbid conditions with CRS case status in two time windows (7-24 months and 0-6 months) prior to diagnosis.

|

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRSwNP vs Controls | CRSsNP vs Controls | ||||

| Pre-morbid condition | 7-24 Months | 0-6 Months | 7-24 Months | 0-6 Months | |

|

|

|||||

| Upper airway | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Acute rhinosinusitis | 2.4 (2.0-2.8)* | 4.6 (3.8-5.7)* | 2.9 (2.7-3.1)* | 7.5 (6.8-8.2)* | |

| Otitis media | 2.2 (1.6-3.0)* | 3.0 (2.1-4.5)* | 1.9 (1.7-2.1)* | 3.4 (2.9-3.9)* | |

| Acute upper respiratory tract infection | 1.5 (1.2-1.9)* | 2.0 (1.5-2.7)* | 1.8 (1.7-1.9)* | 2.9 (2.6-3.2)* | |

| Allergic rhinitis | 3.0 (2.4-3.7)* | 5.4 (4.4-6.8)* | 2.3 (2.1-2.5)* | 3.7 (3.3-4.)* | |

| Chronic rhinitis | 3.0 (2.1-4.3)* | 8.0 (5.5-11.7.)* | 2.8 (2.4-3.3)* | 6.1 (4.8-7.6)* | |

| Post nasal drip | 1.7 (1.3-2.2)* | 2.1 (1.5-2.8)* | 2.0 (1.8-2.2)* | 3.2 (2.9-3.6)* | |

| Adenotonsillitis | 4.0 (1.5-10.5) | 3.2 (0.7-14.4) | 2.6 (1.7-4.0)* | 3.7 (2.2-6.4)* | |

| Sleep apnea | 1.7 (0.8-3.2) | 2.9 (1.5-5.7) | 1.5 (1.1-2.0) | 1.8 (1.3-2.7)* | |

| Lower aerodigestive tract | |||||

| Asthma | 3.2 (2.5-4.0)* | 4.4 (3.4-5.6)* | 1.8 (1.6-2.0)* | 2.5 (2.2-2.9)* | |

| Pneumonia | 1.6 (0.9-2.7) | 0.8 (0.3-2.1) | 1.9 (1.6-2.4)* | 2.7 (2.1-3.5)* | |

| Bronchitis | 1.4 (1.1-1.8) | 1.6 (1.2-2.3) | 1.8 (1.6-1.9)* | 2.8 (2.4-3.2)* | |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 1.5 (1.2-1.9)* | 1.5 (1.1-2.0) | 1.7 (1.6-1.9)* | 1.8 (1.6-2.0)* | |

| Influenza | 1.7 (0.4-7.5) | 1.5 (0.6-3.5) | 1.5 (1.0-2.1) | 2.7 (1.5-4.7)* | |

| Epithelial conditions | |||||

| Conjunctivitis | 1.5 (0.8-2.7) | 2.5 (1.2-5.2) | 1.7 (1.4-2.1)* | 2.0 (1.5-2.7)* | |

| Urinary tract infection | 1.3 (0.8-2.0) | 1.2 (0.6-2.1) | 1.5 (1.3-1.8)* | 1.4 (1.1-1.8) | |

| Atopic dermatitis | 3.2 (1.7-6.0)* | 4.2 (1.6-11.1) | 1.7 (1.3-2.2)* | 2.9 (1.9-4.5)* | |

| Psoriasis | 1.9 (1.0-3.8) | 0.3 (0.0-2.6) | 1.0 (0.7-1.5) | 1.3 (0.8-2.0) | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 0.5 (0.1-2.1) | 1.2 (0.4-4.1) | 1.4 (1.0-2.1) | 1.7 (1.1-2.8) | |

| Skin/Soft Tissue Infections | 1.1 (0.8-1.5) | 1.1 (0.7-1.9) | 1.1 (1.0-1.3) | 1.4 (1.2-1.7) | |

| Systemic autoimmune disease | |||||

| Systemic lupus eythematosis | 1.7 (0.2-13.5) | 1.3 (0.6-3.0) | 2.1 (0.9-4.7) | 1.4 (1.0-2.0) | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 0.7 (0.2-2.2) | 1.2 (0.5-3.0) | 1.5 (1.1-2.1) | 1.2 (0.9-1.9) | |

| Other selected general medical conditions | |||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.8 (0.6-1.0) | 0.7 (0.5-1.0) | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | |

| Obesity | 1.4 (1.0-1.9) | 1.5 (1.0-2.1) | 1.1 (1.0-1.3) | 1.1 (0.9-1.3) | |

| Tobacco use | 1.3 (0.8-2.1) | 1.4 (0.8-2.7) | 1.6 (1.3-1.9)* | 1.4 (1.0-1.8) | |

| Pregnancy | 0.4 (0.1-1.1) | 0.1 (0.0-1.0) | 0.6 (0.5-0.8)* | 0.3 (0.2-0.5) | |

| Selected neuropsychiatric conditions | |||||

| Anxiety | 1.8 (1.2-2.7) | 2.3 (1.4-4.0) | 1.8 (1.5-2.2)* | 1.7 (1.3-2.2)* | |

| Depression | 0.9 (0.5-1.6) | 1.6 (0.9-2.8) | 1.2 (1.0-1.5) | 1.4 (1.1-1.8) | |

| Headache | 2.0 (1.5-2.6)* | 5.3 (3.9-6.9)* | 1.7 (1.5-1.9)* | 3.0 (2.5-3.5)* | |

| Other miscellaneous conditions | |||||

| Hypothyroidism | 1.1 (0.8-1.5) | 1.3 (1.0-1.9) | 1.2 (1.0-1.3) | 1.3 (1.1-1.4) | |

| Colon cancer | 0.6 (0.0-2.8) | 1.0 (0.3-3.2) | 0.7 (0.4-1.2) | 0.5 (0.3-1.0) | |

| Essential hypertension | 0.9 (0.7-1.1) | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | 1.2 (1.1-1.3)* | |

| Heart failure | 1.1 (0.6-2.0) | 1.0 (0.5-1.9) | 1.2 (0.9-1.5) | 1.2 (0.9-1.6) | |

p < 0.0005. Logistic regression was used to derive adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals, controlling for race/ethnicity, sex, and age. NC indicates models did not converge.

Comparison of pre-morbid associations in children and adults

We next examined effect modification by age (< 14 years vs. 14 or more years) on the associations of pre-morbid conditions with CRS case status. During the entire observed period, there was only evidence that age modified the association of preceding asthma with CRS case status (p < 0.0005), with a stronger association in the younger group; for persons younger than 14 years the OR (95% CI) was 2.62 (2.09, 3.17) and for persons 14 and older the OR (95% CI) was 1.67 (1.52, 1.84). When effect of age was examined in the immediate (0-6 months) timeframe preceding CRS diagnosis, the association of asthma strengthened in both groups but particularly in the pediatric age<14 group (p<0.0005); for persons younger than 14 years the OR (95% CI) was 4.72 (3.40, 6.56) and for persons 14 and older the OR (95% CI) was 2.32 (2.02, 2.67). In the intermediate timeframe (7-24 months before CRS), there was evidence that age modified the association of a GERD diagnosis with a much stronger association in the younger group; for persons younger than 14 years the OR (95% CI) was 3.67 (2.51, 5.38) and for persons 14 and older the OR (95% CI) was 1.62 (1.47, 1.78). The associations of other analyzed conditions, including adenotonsillitis, headache and otitis media did not show significant modification by age during any of the observed timeframes.

Health care visit utilization

Given the pattern of pre-morbid conditions observed, we next evaluated the patterns of health care utilization in CRSwNP, CRSsNP and control patients (Table 4). In the intermediate timeframe preceding their diagnosis, CRSwNP patients and CRSsNP patients respectively utilized an average of 5.8 and 6.6 outpatient visits compared with 5.1 visits in controls (all p < 0.0005). In the immediate timeframe preceding their diagnosis, they utilized 2.6 and 2.9 outpatient visits compared to 1.8 in control patients (each p < 0.0005). CRSsNP patients also utilized more inpatient and ED visits than control patients during both the 6 months preceding their diagnosis as well as the prior intermediate interval.

Table 4.

Outpatient, inpatient, and emergency department encounters in two time periods before CRS diagnosis or matched visit in CRS patients and controls respectively.

|

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-6 Months Prior | 7-24 Months Prior | |||||||

| CRSwNP | CRSsNP | Controls | P-value | CRSwNP | CRSsNP | Controls | P-value | |

|

|

||||||||

| Median outpatient visits | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 4 | ||

| Mean (SD) outpatient visits | 2.6 (2.8) | 2.9 (3.0) | 1.8 (2.5) | < 0.0005 | 5.8 (6.1) | 6.6 (6.9) | 5.1 (5.7) | < 0.0005 |

| Mean (SD) inpatient visits | 0.05 (0.3) | 0.08 (0.8) | 0.05 (0.4) | 0.003 | 0.2 (1.1) | 0.3 (1.7) | 0.2 (0.8) | < 0.0005 |

| Mean (SD) emergency visits | 0.01 (0.2) | 0.03 (0.3) | 0.02 (0.2) | 0.04 | 0.05 (0.3) | 0.08 (0.8) | 0.05 (0.4) | 0.006 |

P-values are for a one-way ANOVA of the three groups.

Medication utilization

Patients who subsequently received a diagnosis of CRS were more likely than control patients to have received an antibiotic both in the immediate and intermediate time frame preceding diagnosis (Table 5). CRSsNP patients received an average of 2.7 orders for antibiotics, CRSwNP patients received 2.4 courses of antibiotics while control patients received 1.2 courses of antibiotics in the 24-months prior to the index visit (p < 0.0005). The CRSwNP and CRSsNP patients were significantly more likely than controls to receive an antibiotic in both time frames examined (respectively, for 0-6 months: 43.0%, 54.0%, and 22.3%, and for 7-24 months: 53.8%, 59.5% and 42.3%; all p < 0.0005). The number of nasal and systemic corticosteroid orders was higher among patients who developed CRSwNP and CRSsNP patients in both time frames (both p<0.0005). It is interesting to note that the number of antibiotic orders was more than twice that of systemic or nasal corticosteroids in all timeframes analyzed.

Table 5.

Utilization, prevalence and indication of medication orders (by physician) in two time windows before CRS diagnosis or control visit.

|

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7-24 Months Before CRS Diagnosis | 0-6 Months Before CRS Diagnosis | |||||||

| CRSwNP | CRSsNP | Controls | P-value* | CRSwNP | CRSsNP | Controls | P-value* | |

|

|

||||||||

| Overall antibiotic utilization | ||||||||

| Number of orders, mean (SD) | 1.5 (2.4) | 1.7 (2.3) | 0.9 (1.7) | < 0.0005 | 0.9 (1.7) | 1.1 (1.5) | 0.4 (1.0) | < 0.0005 |

| Antibiotic for any indication | 53.8% | 59.5% | 42.3% | < 0.0005 | 43.0% | 54.0% | 22.3% | < 0.0005 |

| Most common indications for antibiotic prescription | ||||||||

| (% of patients who received medication for indication) | ||||||||

| Acute rhinosinusitis | 29.1% | 35.5% | 16.3% | < 0.0005 | 24.9% | 35.8% | 7.2% | < 0.0005 |

| Bronchitis | 10.9% | 13.6% | 8.3% | <0.0005 | 5.9% | 8.1% | 3.2% | <0.0005 |

| Upper respiratory tract | ||||||||

| infection | 7.7% | 9.6% | 5.7% | < 0.0005 | 3.7% | 4.8% | 1.6% | < 0.0005 |

| Other selected indications | ||||||||

| Otitis media | 5.7% | 10.8% | 6.3% | < 0.0005 | 3.2% | 6.9% | 2.2% | < 0.0005 |

| Skin/soft tissue infection | 5.2% | 5.2% | 4.5% | 0.091 | 1.5% | 2.4% | 1.8% | 0.041 |

| Urinary tract infection | 2.9% | 3.4% | 2.3% | < 0.0005 | 1.7% | 1.6% | 1.1% | < 0.0005 |

| Pneumonia | 0.7% | 2.0% | 0.9% | < 0.0005 | 0.8% | 1.7% | 0.6% | < 0.0005 |

| Overall nasal steroid utilization | ||||||||

| Number of orders, mean (SD) | 0.3 (1.0) | 0.3 (1.0) | 0.2 (0.7) | < 0.0005 | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.0 (0.2) | < 0.0005 |

| Nasal steroid for any indication | 20.8% | 18.3% | 7.3% | < 0.0005 | 18.6% | 14.6% | 3.1% | < 0.0005 |

| Most common indications for nasal steroid prescription | ||||||||

| (% of patients who received medication for indication) | ||||||||

| Allergic rhinitis | 12.8% | 9.4% | 3.8% | < 0.0005 | 11.6% | 7.0% | 1.8% | < 0.0005 |

| Acute rhinosinusitis | 4.8% | 5.7% | 1.5% | < 0.0005 | 3.7% | 4.8% | 0.7% | < 0.0005 |

| Chronic rhinitis | 4.0% | 3.3% | 1.3% | < 0.0005 | 3.2% | 2.5% | 0.5% | < 0.0005 |

| Overall systemic steroid utilization | ||||||||

| Number of orders, mean (SD) | 0.4 (0.9) | 0.3 (0.7) | 0.1 (0.4) | < 0.0005 | 0.2 (0.7) | 0.2 (0.6) | 0.1 (0.4) | < 0.0005 |

| Systemic steroid for any indication | 14.8% | 11.6% | 5.5% | < 0.0005 | 10.6% | 11.1% | 2.4% | < 0.0005 |

| Indication for systemic steroid prescription | ||||||||

| (% of patients who received medication for indication) | ||||||||

| Asthma | 5.9% | 2.9% | 1.2% | < 0.0005 | 3.2% | 2.8% | 0.6% | < 0.0005 |

| Bronchitis | 3.5% | 2.7% | 1.6% | < 0.0005 | 1.7% | 2.5% | 0.6% | < 0.0005 |

| Acute rhinosinusitis | 2.5% | 1.7% | 0.5% | < 0.0005 | 2.5% | 2.4% | 0.2% | < 0.0005 |

For continuous variables, P values are based on F-test from ANOVA for differences between the means; for categorical variables, P values are based on Pearson's chi-square test for association.

The most common indication for antibiotic prescription in all three groups, regardless of time frame, was acute rhinosinusitis. Even in the control group, 7.2% and 16.3% of all patients had received an antibiotic for acute rhinosinusitis in the immediate and intermediate precedent time frames respectively. This was significantly higher than for the second and third most common indications, specifically otitis media (2.2% and 6.3% in the immediate and intermediate periods) and bronchitis (3.2% and 8.3% in the same two periods). In the immediate period prior to the CRS diagnosis, the odds ratios (95% CI), compared to controls, for receiving an antibiotic for acute rhinosinusitis were 4.6 (3.8-5.7) in CRSwNP and 7.5 (6.2-8.2) in CRSsNP patients. In the intermediate period, these associations for acute rhinosinusitis were 2.4 (2.0-2.8) in CRSwNP patients and 2.9 (2.7-3.1) in CRSsNP patients. In addition to acute rhinosinusitis, CRS patients were also more likely to have received an antibiotic for bronchitis, acute pharyngitis and acute URI.

Use of diagnostic testing

We further evaluated the use of recommended confirmatory diagnostic tests (nasal endoscopy or a sinus CT scan) (Table 6)(4, 5). The use of these diagnostic modalities was evaluated in three time intervals: 1) “ever” if the modality had ever been used; 2) 0-12 months before diagnosis; and 3) up to 3 months after diagnosis. CRSwNP patients were more likely than CRSsNP patients and controls to have been evaluated using nasal endoscopy or a sinus CT scan (51.8%, 24.2%, 3.6% respectively, all p < 0.0005). Patients were more frequently evaluated using endoscopy or a CT scan in the 3 months after diagnosis rather than in the 1-year prior.

Table 6.

Prevalence of confirmatory diagnostic test use in patients diagnosed with CRSwNP, CRSsNP and controls in time windows before or after diagnosis

|

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPT Codes | CRSwNP | CRSsNP | Controls | P-value | |

|

|

|||||

| Sinus CT Ever (%) | 70486 | 195 (32.8%) | 1,274 (16.9%) | 93 (1.2%) | <0.0005 |

| Up to 1 year before | 11.6% | 2.5% | 0.3% | ||

| Within 3 months after diagnosis | 15.3% | 11.0% | 0% | ||

| Upper Airway Endoscopy Ever (%) | 31231, 31575, 92511 | 371 (37.7%) | 1,014 (13.5%) | 212 (2.6%) | <0.0005 |

| Up to 1 year before | 6.9% | 1.4% | 0.4% | ||

| Within 3 months after diagnosis | 19.5% | 4.1% | 0.1% | ||

| Endoscopy or CT Ever (%) | 308 (51.8%) | 1,820 (24.2%) | 294 (3.6%) | <0.0005 | |

| Endoscopy and CT Ever (%) | 111 (18.7%) | 468 (6.2%) | 11 (0.1%) | <0.0005 | |

Discussion

In this study, we utilized 10 years of data from a large cohort of primary care patients from the EHR of the dominant healthcare provider serving an expansive geographic region to evaluate the epidemiology of CRS, test several previously proposed hypotheses regarding the pathobiology of CRS and examine how CRS is being treated and diagnosed in the community. To our knowledge, this study has provided the first estimate of the incidence of physician-diagnosed CRS. Our study shows a remarkable pattern of episodic and chronic airway illnesses preceding diagnosis of both CRS subtypes lending support to the notion of the unified airway linked by common physiologic and pathologic responses in both the upper and lower airway. While the association of airway diseases with subsequent diagnosis of CRS was strongest in the 0-6 months immediately before diagnosis, this pattern extended to the prior 7-24 months before diagnosis. These findings further suggest that acute episodic respiratory diseases may modify host susceptibility to CRS, perhaps similar to the relationship between rhinovirus and respiratory syncytial virus infections and subsequent asthma development(12, 13). Additionally, we show that there are modest, but highly significant, associations between pre-morbid infections at other non-respiratory sites, GERD and sleep apnea, anxiety and headache disorders among patients subsequently diagnosed with CRS. While there was a strong magnitude of association between autoinflammatory/autoimmune conditions, our study may still be underpowered to study the associations with relatively rare conditions like autoimmunity. In our analysis of healthcare practice patterns preceding CRS diagnosis, we find that CRS patients used antibiotics, nasal and systemic corticosteroids and outpatient and inpatient healthcare services more frequently than controls and that CRS is commonly diagnosed without the use of confirmatory diagnostic testing such as nasal endoscopy or sinus imaging.

Strengths of this study include the use of physician-coded diagnoses, entered at the time of encounter. This is likely a more accurate record of pre-morbid illness than patient recall typically used in most previous studies of pre-morbid risk factors in CRS(7, 14, 15). This study was performed in an area of remarkable population stability and encompassed patients receiving care in a variety of settings and is less susceptible to referral bias than most specialty-based studies of CRS. Furthermore, patients in this study had been under observation for a median duration of approximately five years and included a precedent timeframe well in excess of the symptomatic prodrome expected for CRS. The length of observation also enabled us to examine for associations and utilization trends preceding CRS that could not be examined in prior epidemiologic studies utilizing the episode-based sampling methodology of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) to study CRS(16, 17). Finally, we were also able to compare our findings to an age, sex and visit-matched population to evaluate associations, and their magnitude, with the pre-morbid illnesses studied. While interpretation of epidemiological data is dependent on both the magnitude of association and the precision of the estimate, we choose to focus discussion on results significant at a very conservative p-value (<0.0005). To our knowledge, this study represents the first non-specialty care based, population representative, case-control study examining the pre-morbid diagnoses and health utilization of CRS patients. Our study was able to re-demonstrate previously known demographic risk factors for CRSwNP-namely, male gender and increased age(18, 19). Our study also expands on previous findings that CRS patients have more frequent exacerbations in winter(20), and demonstrates that winter and fall seasons were strongly associated with incident CRSsNP diagnosis but not with CRSwNP. We affirm diseases previously thought to be risk factors for the development of CRS such as asthma(21) and allergic rhinitis(22) have a large and significant association with subsequent diagnosis and further show that asthma, in particular, is a stronger risk factor in children compared to adults. This supports previous studies that have shown that between 70-88% of asthmatics report sinonasal symptoms(23) and CRSwNP patients are more likely to have concurrent asthma(24, 25). While atopy is frequently cited as a risk factor for CRS(22), the relationship between atopy and CRS is underexplored at the population level and is complicated by factors including an intrinsic bias among patients getting tested for atopy, the uncertain significance of individual skin test or RAST test positivity, and variation in the panels used for atopic testing(26). Nonetheless, high rates of atopy are detected among patients with CRS(19), there are parallels between the gene transcription program of nasal polyps and skin from atopic dermatitis(27), and there does appear to be a physiologic relationship between positive nasal challenge and sinus inflammation(28). Similarly, a longitudinal case-control study of Navy aircrew also demonstrated that there was a statistically significant increase in the number of cases of CRS in subjects who had a history of allergic rhinitis(29).

Our study finds dramatic associations between expected conditions of the upper airway, such as chronic rhinitis, acute sinusitis and post nasal drip, but also finds an elevated pre-morbid risk of several acute and chronic inflammatory conditions of the middle ear and lower airway. Otitis media, adenotonsillitis, pneumonia, and bronchitis were each modestly, but significantly, associated with subsequent diagnosis of CRSsNP in both adults and children. Similar associations were observed for CRSwNP patients, but results did not achieve statistical significance possibly due to the substantially smaller size of the CRSwNP group. These findings provide strong support for a unified airway concept in which the mucosal surfaces of the upper and lower airway, including the middle ear and Waldeyer's ring, likely share common pathogens and mechanisms of inflammation and innate immunity(30, 31). Given the success of vaccinations for the prevention of pneumonia and influenza, these findings raise the possibility that prophylactic vaccinations may find efficacy in the prevention of CRS.

In addition to airway conditions, our study finds a relatively strong and significant association between sleep apnea and GERD in both groups of CRS patients. The association between GERD was significant across all timeframes preceding diagnosis while for sleep apnea, separating the analysis into two separate time periods reduced the power to detect a significant association. When the effect of age on the association of GERD and CRS was analyzed, we found age strengthened the association between GERD and CRS diagnosis, particularly in children. The relationship between GERD and sinusitis is controversial but several large epidemiologic case-controlled studies of adults and children have consistently demonstrated an association between GERD and sinusitis(32, 33). Furthermore, the European Community Respiratory Health Study (ECRHS). a multinational longitudinal study have suggested that GERD, particularly nocturnal GERD, is strongly associated with the development of lower respiratory disease such as asthma but have not specifically examined its impact on sinusitis(34, 35). These studies have similarly found that nocturnal GERD is frequently co-morbid with sleep apnea while more recent analyses suggest that the GERD precedes the onset of both sleep apnea and the respiratory symptoms(36). Together with our findings, these studies may suggest that GERD, possibly in parallel with co-morbid sleep apnea, may play an important, but under-recognized, role in the pathogenesis of CRS- perhaps via direct mucosal injury from refluxed or aerosolized acid. Evidence for anti-reflux therapy in treating CRS is limited but has been studied in several small series previously reviewed by Debaise (37) and represents a possible preventive option that requires further study. Unfortunately, since the ICD-9 codes for laryngopharyngeal reflux and other extraesophageal manifestations of GERD are shared with other non-specific diagnoses, we were limited in our ability to assess the impact of these condition on CRS.

A significant association between CRS and infectious and inflammatory conditions outside the airway has not been reported for immunocompetent individuals (pre-morbid diagnosis of an acquired ICD-9 042 and 043 or primary ICD-9 279.X immunodeficiency were rare in this population, <10 individuals total per ICD-9 code), but our study shows a modest, but significant,, association between conjunctivitis, atopic dermatitis, SSTI and UTI among CRS patients. While these relatively modest associations may reflect our high study power, we believe that these findings do reflect a biologically meaningful association between an impaired host epithelial barrier or innate immune system and the development of CRS as has been suggested by studies from our laboratory and others(38, 39). These disparate epithelial sites share some common epithelial structural elements, pathogens, innate immune responses and pathways of inflammation with the nasal mucosa and this study provides the first population-based epidemiologic evidence to suggest that CRS patients may suffer from elevated rates of infections at epithelial sites outside the airway. We are further reassured by our use of a very conservative p-value and the many prevalent general medical conditions, like hypertension, hyperthyroidism, obesity and diabetes, which are present at similar rates across groups.

Our study also suggests that there is a strong association between pre-morbid headaches and anxiety with CRS. In fact, the magnitude of these associations was almost similar to that or asthma and allergic rhinitis. While it is well described that self-diagnosed sinus headaches are frequently manifestations of migraine(40), and migraineurs are frequently told by their physicians they have “sinus headaches”(41), we are unaware of studies that associate headache disorders with a subsequent CRS diagnosis. While autonomic manifestations of migraine are known, it is unclear if these autonomic manifestations result in ostial occlusion and inflammation of sinuses. More likely, the autonomic manifestations of migraine result in a symptom complex clinically indistinguishable from CRS, resulting in misdiagnosis as suggested in multiple prior studies(42-44). The significant and relatively large association with anxiety, but not depression, in subsequent CRS diagnosis is interesting since both are frequently co-morbid and are components of negative affect (NA) in psychosomatic theory(45). Extensive literature suggests NA increases reporting of physical symptoms in the presence and absence of physical illness(46). However, more recent studies suggest that anxiety and depression affect symptom reporting in different ways with anxiety being more longitudinally stable(47) and that anxious individuals report higher levels of experienced symptoms than ones with a depressive affect(48). Thus, in a disease like CRS where symptoms are central to diagnosis and objective testing is still underutilized, symptom reporting can substantially alter the likelihood of diagnosis.

In our study, only 24% of patients diagnosed with CRSsNP and 52% of patients receiving a diagnosis of CRSwNP were documented to have received nasal endoscopy or a sinus CT for confirmatory diagnostic testing. Testing was usually performed after diagnosis, and presumably, treatment and our study highlights the low rates of guideline recommended confirmatory diagnostic testing for CRS in the primary care setting. Despite low rates of confirmatory testing, CRS patients receive between 2-3 times the number of antibiotic prescriptions received by age and sex matched control patients. Few previous studies examine antibiotic usage in relation to the specific site of acute URI(49) but a NAMCS-based study by Steinman el al estimates that antibiotic usage for rhinosinusitis is the single most common indication for ambulatory antibiotic use, accounting for approximately 8 million antibiotic prescriptions annually(50). Similarly, a recent study suggested that symptom duration was the most heavily weighted variable in the community practitioner's decision to prescribe an antibiotic for a URI(51). Thus, our study emphasizes the importance of CRS care in overall antibiotic stewardship and suggests the need for vigorous dissemination of specialty guideline recommendations to the primary-care setting.

Limitations of this study were that these observations were made using retrospective analysis of practitioner coded ICD-9 codes and subsequently, the adherence to professional society guidelines for the diagnosis of each condition could not be assured. Furthermore, given the low rates of utilization of confirmatory testing for CRS, especially in CRSsNP, accurate differentiation of CRSwNP patients from the CRSsNP patients may not be possible using our current methodology. Since there exists considerable overlap in the symptoms of the two CRS phenotypes as well as non-CRS diseases with overlapping symptoms, a non-specialist physician diagnosis of CRS may be insufficient to accurately define this disease(52, 53). Inaccurate differentiation between CRS phenotypes and non-CRS diseases with similar symptoms may potentially explain the few differences we find in the pre-morbid patterns of illness among CRSwNP and CRSsNP patients. However, we believe these concerns are mitigated by our large longitudinal dataset that is sampled from a population with low attrition that is served by a single primary care focused healthcare organization. Together, these data reflect likely reflect the current state of CRS care as practiced in the real-world, primary care setting.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants K23DC012067 (B.K.T), R01 HL068546, R01 HL078860 and R01 AI072570 as well as the Ernest S. Bazley Trust (R.P.S).

Abbreviations

- aOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- CRS

Chronic rhinosinusitis

- CRSsNP

Chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps

- CRSwNP

Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps

- CPT

Current Procedural Terminology

- CT

Computed tomography

- EHR

Electronic health record

- GERD

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision

- NAMCS

National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- NHIS

National Health Interview Survey

- URI

Upper respiratory tract infection

- UTI

Urinary tract infection

- SSTI

Skin/soft tissue infection

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: The authors have declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Capsule summary: This study estimates the incidence of CRS. We further demonstrate that patients diagnosed with CRS have an elevated pre-morbid prevalence of episodic and chronic diseases of the airway, sleep apnea, GERD, anxiety and headaches.

Clinical Implications: Patients who develop CRS have an increased pre-morbid prevalence of inflammatory and infectious conditions of the airway and other epithelial barriers, GERD and sleep apnea. Compliance with guideline recommendations for accurate diagnosis of CRS is low.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Mullol J, Bachert C, Alobid I, Baroody F, et al. EPOS 2012: European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2012. A summary for otorhinolaryngologists. Rhinology. 2012;50(1):1–12. doi: 10.4193/Rhino12.000. Epub 2012/04/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meltzer EO, Hamilos DL, Hadley JA, Lanza DC, Marple BF, Nicklas RA, et al. Rhinosinusitis: establishing definitions for clinical research and patient care. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(6 Suppl):155–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.09.029. Epub 2004/12/04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pleis JR, Lucas JW, Ward BW. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2008. Vital Health Stat. 2009;10(242):1–157. Epub 2010/09/09. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, Cheung D, Eisenberg S, Ganiats TG, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(3 Suppl):S1–31. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.06.726. Epub 2007/09/28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas M, Yawn BP, Price D, Lund V, Mullol J, Fokkens W. EPOS Primary Care Guidelines: European Position Paper on the Primary Care Diagnosis and Management of Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2007 - a summary. Prim Care Respir J. 2008;17(2):79–89. doi: 10.3132/pcrj.2008.00029. Epub 2008/04/29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamilos DL. Chronic rhinosinusitis: Epidemiology and medical management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.08.004. Epub 2011/09/06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryan MW. Diseases associated with chronic rhinosinusitis: what is the significance? Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;16(3):231–6. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e3282fdc3c5. Epub 2008/05/14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan BK, Schleimer RP, Kern RC. Perspectives on the etiology of chronic rhinosinusitis. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;18(1):21–6. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e3283350053. Epub 2009/12/08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomassen P, Van Zele T, Zhang N, Perez-Novo C, Van Bruaene N, Gevaert P, et al. Pathophysiology of chronic rhinosinusitis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2011;8(1):115–20. doi: 10.1513/pats.201005-036RN. Epub 2011/03/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Y, Dales R, Lin M. The epidemiology of chronic rhinosinusitis in Canadians. Laryngoscope. 2003;113(7):1199–205. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200307000-00016. Epub 2003/07/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Min YG, Jung HW, Kim HS, Park SK, Yoo KY. Prevalence and risk factors of chronic sinusitis in Korea: results of a nationwide survey. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1996;253(7):435–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00168498. Epub 1996/01/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carroll KN, Wu P, Gebretsadik T, Griffin MR, Dupont WD, Mitchel EF, et al. The severity-dependent relationship of infant bronchiolitis on the risk and morbidity of early childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(5):1055–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.02.021. 61 e1. Epub 2009/04/14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James KM, Peebles RS, Jr, Hartert TV. Response to infections in patients with asthma and atopic disease: an epiphenomenon or reflection of host susceptibility? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(2):343–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.05.056. Epub 2012/08/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gelincik A, Buyukozturk S, Aslan I, Aydin S, Ozseker F, Colakoglu B, et al. Allergic vs nonallergic rhinitis: which is more predisposing to chronic rhinosinusitis? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101(1):18–22. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60829-0. Epub 2008/08/07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reh DD, Lin SY, Clipp SL, Irani L, Alberg AJ, Navas-Acien A. Secondhand tobacco smoke exposure and chronic rhinosinusitis: a population-based case-control study. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2009;23(6):562–7. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3377. Epub 2009/12/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mattos JL, Woodard CR, Payne SC. Trends in common rhinologic illnesses: Analysis of U.S. healthcare surveys 1995–2007. International Forum of Allergy & Rhinology. 2011;1(1):3–12. doi: 10.1002/alr.20003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith WM, Davidson TM, Murphy C. Regional variations in chronic rhinosinusitis, 2003-2006. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141(3):347–52. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.05.021. Epub 2009/09/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munoz del Castillo F, Jurado-Ramos A, Fernandez-Conde BL, Soler R, Barasona MJ, Cantillo E, et al. Allergenic profile of nasal polyposis. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2009;19(2):110–6. Epub 2009/05/30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan BK, Zirkle W, Chandra RK, Lin D, Conley DB, Peters AT, et al. Atopic profile of patients failing medical therapy for chronic rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2011;1(2):88–94. doi: 10.1002/alr.20025. Epub 2011/07/07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rank MA, Wollan P, Kita H, Yawn BP. Acute exacerbations of chronic rhinosinusitis occur in a distinct seasonal pattern. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(1):168–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.03.041. Epub 2010/07/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joe SA, Thakkar K. Chronic rhinosinusitis and asthma. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2008;41(2):297–309. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2007.11.001. vi. Epub 2008/03/11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marple BF. Allergic rhinitis and inflammatory airway disease: interactions within the unified airspace. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2010;24(4):249–54. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2010.24.3499. Epub 2010/09/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bresciani M, Paradis L, Des Roches A, Vernhet H, Vachier I, Godard P, et al. Rhinosinusitis in severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107(1):73–80. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.111593. Epub 2001/01/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hedman J, Kaprio J, Poussa T, Nieminen MM. Prevalence of asthma, aspirin intolerance, nasal polyposis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a population-based study. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28(4):717–22. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.4.717. Epub 1999/09/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johansson L, Akerlund A, Holmberg K, Melen I, Bende M. Prevalence of nasal polyps in adults: the Skovde population-based study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003;112(7):625–9. doi: 10.1177/000348940311200709. Epub 2003/08/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fokkens W, Lund V, Bachert C, Clement P, Helllings P, Holmstrom M, et al. EAACI position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps executive summary. Allergy. 2005;60(5):583–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00830.x. Epub 2005/04/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plager DA, Kahl JC, Asmann YW, Nilson AE, Pallanch JF, Friedman O, et al. Gene transcription changes in asthmatic chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps and comparison to those in atopic dermatitis. PloS one. 2010;5(7):e11450. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011450. Epub 2010/07/14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baroody FM, Mucha SM, Detineo M, Naclerio RM. Nasal challenge with allergen leads to maxillary sinus inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(5):1126–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.02.010. e7. Epub 2008/03/28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker C, Williams H, Phelan J. Allergic rhinitis history as a predictor of other future disqualifying otorhinolaryngological defects. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1998;69(10):952–6. Epub 1998/10/17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braunstahl GJ. United airways concept: what does it teach us about systemic inflammation in airways disease? Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6(8):652–4. doi: 10.1513/pats.200906-052DP. Epub 2009/12/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braunstahl GJ, Hellings PW. Nasobronchial interaction mechanisms in allergic airways disease. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;14(3):176–82. doi: 10.1097/01.moo.0000193186.15440.39. Epub 2006/05/27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El-Serag HB, Gilger M, Kuebeler M, Rabeneck L. Extraesophageal associations of gastroesophageal reflux disease in children without neurologic defects. Gastroenterology. 2001;121(6):1294–9. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.29545. Epub 2001/12/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.el-Serag HB, Sonnenberg A. Comorbid occurrence of laryngeal or pulmonary disease with esophagitis in United States military veterans. Gastroenterology. 1997;113(3):755–60. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70168-9. Epub 1997/09/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emilsson OI, Janson C, Benediktsdottir B, Juliusson S, Gislason T. Nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux, lung function and symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea: Results from an epidemiological survey. Respiratory medicine. 2012;106(3):459–66. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.12.004. Epub 2011/12/27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gislason T, Janson C, Vermeire P, Plaschke P, Bjornsson E, Gislason D, et al. Respiratory symptoms and nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study of young adults in three European countries. Chest. 2002;121(1):158–63. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.1.158. Epub 2002/01/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emilsson OI, Bengtsson A, Franklin KA, Toren K, Benediktsdottir B, Farkhooy A, et al. Nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux, asthma and symptoms of obstructive sleep apnoea: a longitudinal, general population study. Eur Respir J. 2012 doi: 10.1183/09031936.00052512. Epub 2012/09/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dibaise JK, Sharma VK. Does gastroesophageal reflux contribute to the development of chronic sinusitis? A review of the evidence. Dis Esophagus. 2006;19(6):419–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2006.00616.x. Epub 2006/10/31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kern RC, Conley DB, Walsh W, Chandra R, Kato A, Tripathi-Peters A, et al. Perspectives on the etiology of chronic rhinosinusitis: an immune barrier hypothesis. Am J Rhinol. 2008;22(6):549–59. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3228. Epub 2008/09/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schleimer RP, Kato A, Peters A, Conley D, Kim J, Liu MC, et al. Epithelium, inflammation, and immunity in the upper airways of humans: studies in chronic rhinosinusitis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6(3):288–94. doi: 10.1513/pats.200808-088RM. Epub 2009/04/24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eross E, Dodick D, Eross M. The Sinus, Allergy and Migraine Study (SAMS) Headache. 2007;47(2):213–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00688.x. Epub 2007/02/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lipton RB, Diamond S, Reed M, Diamond ML, Stewart WF. Migraine diagnosis and treatment: results from the American Migraine Study II. Headache. 2001;41(7):638–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.041007638.x. Epub 2001/09/14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stankiewicz JA, Chow JM. A diagnostic dilemma for chronic rhinosinusitis: definition accuracy and validity. American journal of rhinology. 2002;16(4):199–202. Epub 2002/09/12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tan BK, Chandra RK, Conley DB, Tudor RS, Kern RC. A randomized trial examining the effect of pretreatment point-of-care computed tomography imaging on the management of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis symptoms. International Forum of Allergy & Rhinology. 2011;1(3):229–34. doi: 10.1002/alr.20044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mehle ME, Kremer PS. Sinus CT scan findings in “sinus headache” migraineurs. Headache. 2008;48(1):67–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00811.x. Epub 2008/01/11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watson D, Clark LA. Negative affectivity: the disposition to experience aversive emotional states. Psychological bulletin. 1984;96(3):465–90. Epub 1984/11/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Neuroticism, somatic complaints, and disease: is the bark worse than the bite? Journal of personality. 1987;55(2):299–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1987.tb00438.x. Epub 1987/06/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wetherell JL, Gatz M, Pedersen NL. A longitudinal analysis of anxiety and depressive symptoms. Psychology and aging. 2001;16(2):187–95. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.16.2.187. Epub 2001/06/19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Howren MB, Suls J. The symptom perception hypothesis revised: depression and anxiety play different roles in concurrent and retrospective physical symptom reporting. Journal of personality and social psychology. 2011;100(1):182–95. doi: 10.1037/a0021715. Epub 2011/01/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roumie CL, Halasa NB, Grijalva CG, Edwards KM, Zhu Y, Dittus RS, et al. Trends in antibiotic prescribing for adults in the United States--1995 to 2002. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(8):697–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0148.x. Epub 2005/07/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steinman MA, Gonzales R, Linder JA, Landefeld CS. Changing use of antibiotics in community-based outpatient practice, 1991-1999. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(7):525–33. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-7-200304010-00008. Epub 2003/04/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wigton RS, Darr CA, Corbett KK, Nickol DR, Gonzales R. How do community practitioners decide whether to prescribe antibiotics for acute respiratory tract infections? J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1615–20. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0707-9. Epub 2008/07/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dietz de Loos DAE, Hopkins C, Fokkens WJ. Symptoms in chronic rhinosinusitis with and without nasal polyps. The Laryngoscope. 2013;123(1):57–63. doi: 10.1002/lary.23671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hsueh WD, Conley DB, Kim H, Shintani-Smith S, Chandra RK, Kern RC, et al. Identifying clinical symptoms for improving the symptomatic diagnosis of chronic rhinosinusitis. International forum of allergy & rhinology. 2012 doi: 10.1002/alr.21106. Epub 2012/11/07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]