Abstract

Defense against attaching and effacing (A/E) bacteria requires the sequential generation of interleukin 23 (IL-23) and IL-22 to induce protective mucosal responses. While CD4+ and NKp46+ innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) are the critical source of IL-22 during infection, the precise source of IL-23 is unclear. We used genetic techniques to deplete specific subsets of classical dendritic cells (cDCs) and analyzed immunity to the A/E pathogen Citrobacter rodentium. We found that Notch2 controlled the terminal stage of cDC differentiation. Notch2-dependent intestinal CD11b+ cDCs, but not Batf3-dependent CD103+ cDCs, were an obligate source of IL-23 required to survive C. rodentium infection. These results provide the first demonstration of a non-redundant function of CD11b+ cDCs in response to pathogens in vivo.

Introduction

The cytokines interleukin-23 (IL-23) and IL-22 are critical for immune responses that maintain mucosal integrity against infections by A/E bacterial pathogens1,2. Isolated lymphoid follicles (ILFs) in the small and large intestine contain DCs, B cells and ILCs that orchestrate protection against these pathogens2-4. During A/E infections, ILCs produce IL-22, which promotes barrier integrity by inducing the production of anti-microbial peptides, including RegIIIβ and RegIIIγ, from epithelial cells2,5,6. The importance of IL-22 is highlighted by greatly increased susceptibility of Il22−/− mice to the A/E bacterium Citrobacter rodentium, a model for human enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli infections2,6,7.

IL-22-producing ILCs are heterogeneous and include a CD4+ subset5 and a CD4−NKp46+ subset8. Both subsets express the transcription factor RORγt, which is required for their development9,10. An important unresolved question is the identity of the cells that stimulate ILCs to produce IL-22. ILCs do not directly detect infection by A/E pathogens but instead appear to depend on IL-23 produced by other innate cells for their activation8. In responses against C. rodentium, it has been suggested that either macrophages or DCs may be the important source of IL-23 (refs. 11,12). A role for macrophages was proposed based on increased pathogen burden in Cx3cr1−/− mice as well as the increased susceptibility of CD11c-DTR mice treated with diphtheria toxin (DT), in which cells that express DT receptor (DTR) under the control of the CD11c promoter are selectively depleted12. Alternatively, a role for cDCs was proposed from the increased pathogen burden and reduced IL-23 production in mice lacking lymphotoxin β receptor (LTβR) in CD11c-expressing cells11, and by a separate observation that cDCs are the major source of IL-23 following TLR5 stimulation13.

The opposing conclusions of these studies highlight the difficulty in distinguishing the roles of macrophages and cDCs in vivo, particularly when relying on CD11c-based depletion methods14. Recently, Zbtb46 has been identified as a transcription factor that is expressed in cDCs but not macrophages, monocytes or plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs), and expression of DTR under the control of the Zbtb46 promoter allows for selective depletion of cDCs15,16. In addition, recently developed systems also allow selective depletion of individual cDCs subsets in vivo17-20. Mice deficient in the transcription factor Batf3 lack the CD8α+CD103+ cDC subset; as a result, these mice have defective CD8+ T cell responses against several viral pathogens17,21 and are highly susceptible to Toxoplasma gondii infection22. Similarly, mice with selective depletion of pDCs exhibit defects in type 1 interferon production and are susceptible to chronic infection by viruses such as lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV)19,23. Together, these systems of selective depletion have revealed non-redundant roles for CD8α+ cDCs and pDCs, but not for the third major subset of DCs, the CD11b+ cDCs.

A subset of CD11b+ cDCs in vivo expressing the adhesion molecule ESAM is depleted by conditional deletion of Notch2 (ref. 18). That study proposed that Notch2 signaling is selectively required for the development of splenic CD11b+ESAM+ cDCs and intestinal CD103+CD11b+ cDCs derived from the pre-cDC, analogous to the unique dependence of CD8α+ cDCs on Batf3 (ref. 17). However, CD11b+ESAM− cDCs persist in Notch2-deficient mice, prompting the question of how these cells are related to CD11b+ESAM+ cDCs and whether they provide compensatory functions. Furthermore, while that study implied that Notch2 specifically regulates the CD11b+ branch of cDCs, some evidence indicated a developmental defect in the CD8α+ branch as well, although this was not further analyzed18. Surprisingly, mice lacking CD11b+ESAM+ cDCs have only a 2-fold reduction in IL-17 produced by ex vivo-stimulated T cells, and responses during infection have not been examined to reveal a specific functional role for these cells in immune defense.

Here, we provide a demonstration of a selective function for CD11b+ cDCs in immune defense to pathogens. Using several genetic models that selectively deplete different subsets of cDCs in vivo, we found that Notch2-dependent intestinal CD103+CD11b+ cDCs, but not macrophages or Batf3-dependent CD103+CD11b− cDCs, provided non-redundant protection to A/E pathogen infection. Notch2-deficient mice were required for the generation of local IL-23-dependent anti-microbial responses early after infection. Developmentally, Notch2 regulated the terminal differentiation of both the CD8α+ and the CD11b+ branches of cDCs, which allowed for their subsequent homeostatic expansion mediated by LTβR signaling. These results demonstrate that intestinal CD103+CD11b+ cDCs detect A/E pathogen infection and secrete IL-23, which is critical for IL-22 production by ILCs and maintenance of mucosal integrity.

Results

Zbtb46+ cDCs mediate host defense against A/E pathogens

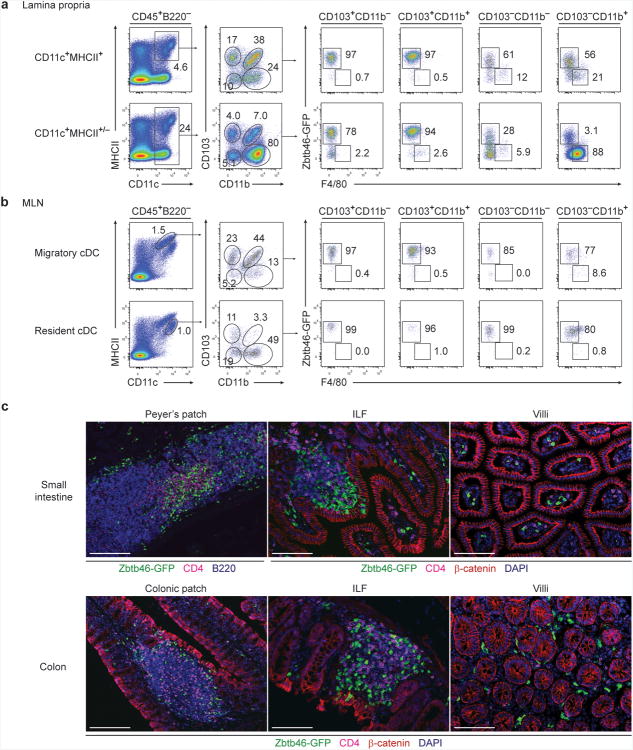

The generation of Zbtb46gfp and Zbtb46DTR mice has allowed for the selective visualization and depletion of cDCs, which can help to distinguish requirements for cDCs and macrophages in immune responses in vivo15,16. We asked whether expression of Zbtb46-GFP could distinguish cDCs from macrophages in the intestinal lamina propria and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) (Fig. 1a,b). Among MHCII+CD11c+ lamina propria cells, CD103+CD11b− and CD103+CD11b+ cells were uniformly GFP+, consistent with cDCs. Both CD103−CD11b+ and CD103−CD11b− cells also showed a substantial GFP+ fraction (Fig. 1a), in agreement with previous studies suggesting that cDCs may also reside within these gates16,24,25. In contrast, F4/80+ macrophages were contained predominantly within the MHCII−CD11c+ gate and did not express GFP (Fig. 1a). In MLNs, migratory cDCs26,27 were uniformly GFP+ and were predominantly within the CD103+CD11b− and CD103+CD11b+ gates (Fig. 1b), consistent with the ability of cDCs, but not macrophages, to migrate to MLNs28. Resident cDCs were also uniformly GFP+, but were predominantly within the CD103−CD11b− or CD103−CD11b+ gates. Thus, expression of Zbtb46 appears to distinguish cDCs from macrophages in the intestine independently of their expression of CD103 or CD11b. Histological assessment of the small intestine in Zbtb46gfp bone marrow (BM) chimeras revealed that GFP+ cDCs were present in organized lymphoid structures including Peyer's patches and ILFs, as well as at points of antigen encounter within intestinal villi (Fig. 1c). In the large intestine, GFP+ cDCs were also present in colonic patches, ILFs and surrounding villi (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1. Zbtb46-GFP identifies intestinal cDC populations.

(a,b) Lamina propria (a) and MLN (b) cells from Zbtb46gfp/+ mice were stained for expression of the indicated markers. Two-color histograms are shown for live cells pre-gated as indicated above the diagram. Numbers represent the percentage of cells within the indicated gate. Data are representative of three independent experiments (n = 9 mice). (c) Small intestine (top) and colon (bottom) sections from Zbtb46gfp/+ → wild-type (WT) BM chimeras were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy for expression of B220, CD4, β-catenin, Zbtb46-GFP and DAPI as indicated. Images are representative of two independent experiments (n = 5 mice). Scale bars, 200 μm (Peyer's patch and colonic patch), 100 μm (ILFs and villi). ILF, isolated lymphoid follicle.

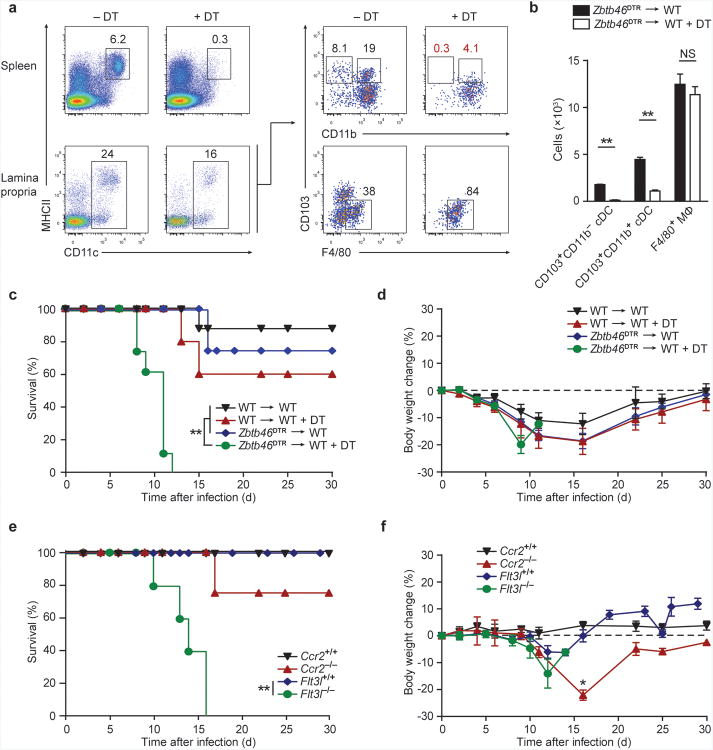

These results suggested that administration of DT to Zbtb46DTR mice should selectively eliminate cDCs but spare macrophages. Indeed, DT treatment of Zbtb46DTR BM chimeras significantly diminished the frequency of both CD103+CD11b− and CD103+CD11b+ cDCs in the lamina propria and the F4/80− populations of CD103−CD11b− and CD103−CD11b+ cDCs, but did not affect F4/80+ macrophages (Fig. 2a,b). In addition, lamina propria lymphocytes and ILCs were not depleted by DT treatment of Zbtb46DTR BM chimeras and did not express Zbtb46-GFP (Supplementary Fig. 1a-c). Thus, we used this system to determine whether cDCs are required for protection against a model A/E pathogen, C. rodentium. We found that Zbtb46DTR BM chimeras treated with DT were unable to recover following C. rodentium challenge and died within 8-12 days after infection (Fig. 2c). In contrast, wild-type chimeras and Zbtb46DTR BM chimeras not treated with DT survived beyond 15 days, showing some weight loss but recovering normal weight by 30 days after infection (Fig. 2c,d).

Figure 2. Zbtb46+ cDCs are essential for survival after C. rodentium infection.

(a, b) Zbtb46DTR → WT BM chimeras were treated with 40 ng/g DT at day -3 and day -1 and splenocytes or lamina propria cells were stained for expression of the indicated markers on day 0. (a) Two-color histograms are shown for live cells pre-gated as indicated. (b) Quantification of lamina propria cDC depletion in Zbtb46DTR → WT BM chimeras from [a]. Bars represent cDC or macrophage (MΦ) cell numbers per 1 × 106 lamina propria cells. Data are from two independent experiments (error bars, SEM; n = 4 mice, Student's t-test). (c,d) The indicated BM chimeras were treated with DT (20 ng/g) one day prior to infection and every third day (5 ng/g) for the remainder of the experiment. Mice were orally inoculated with 2 × 109 c.f.u. C. rodentium and followed for survival (c) and weight loss (d). Data are from two independent experiments (error bars, SEM; n = 8 mice per group, except WT+DT n = 5 mice, survival: log-rank Mantel-Cox test, weight loss: Student's t-test). (e,f) Survival (e) and weight loss (f) of mice infected with C. rodentium. Data are from two independent experiments (error bars, SEM; Flt3l+/+ n = 10, Flt3l−/− n = 10, Ccr2+/+ n = 5, Ccr2−/− n = 4, survival: log-rank Mantel-Cox test, weight loss: Student's t-test) * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.001, NS not significant.

To confirm a specific role for cDCs and to test for a role for monocyte-derived cells in protection from C. rodentium, we next analyzed Flt3l−/−29 and Ccr2−/− mice30. Flt3l−/− mice have decreased numbers of lamina propria cDCs but maintain normal numbers of macrophages and monocytes24,25. Similar to DT-treated Zbtb46DTR chimeras, Flt3l−/− mice succumbed to C. rodentium infection after 10-16 days (Fig. 2e,f). In contrast, Ccr2−/− mice have a specific defect in the recruitment of monocytes to the intestinal lamina propria, but maintain normal populations of cDCs31. Although Ccr2−/− mice exhibited substantial weight loss in comparison to wild-type controls, only 25% succumbed to infection. These results demonstrate that cDCs, rather than macrophages or monocyte-derived cells, are required for early innate defense against C. rodentium, but do not indicate whether a particular cDC subset is required.

Notch2-deficient mice lack CD11b+ cDCs in vivo

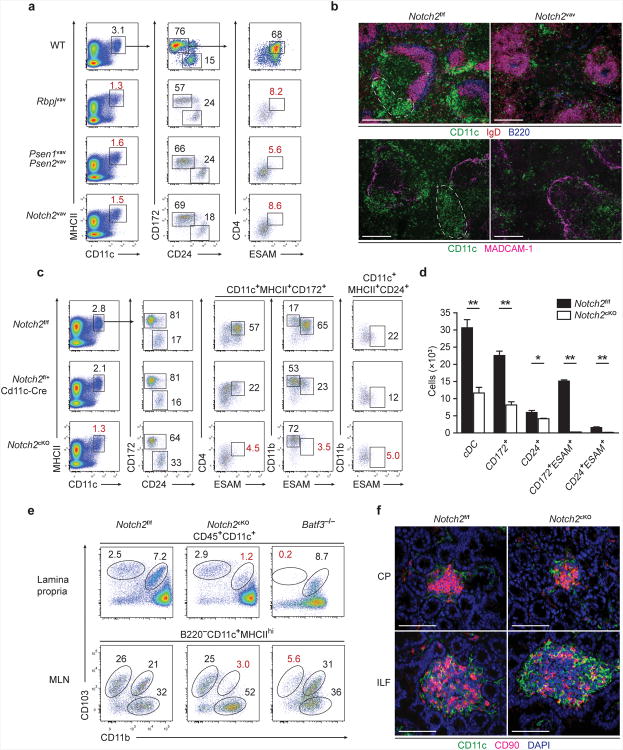

The transcription factor Notch2 is required for the development of the CD11b+ESAM+ cDC fraction18. However, the specific function of these cells has not been determined in vivo. To characterize how Notch2 signaling influences cDC development, we examined the requirement of Notch2, its transcriptional partner RBPJ and the γ-secretase complex composed of presenilin 1 (PSEN1) and PSEN2 for splenic CD8α+ and CD11b+ cDC development (Fig. 3a). Hematopoietic loss of either Rbpj or Notch2 mediated by Vav1-Cre (Rbpjvav and Notch2vav) caused a decrease in the frequency of CD11c+MHCII+ cDCs and CD8α+ cDCs (identified by expression of CD24), and eliminated CD11b+ESAM+CD4+ cDCs (also identifiable by expression of CD172 rather than CD11b) (Fig. 3a). Vav1-Cre-mediated deletion of Psen1 and Psen2 (Psen1vavPsen2vav) also caused similar reductions in CD11c+MHCII+ and CD8α+ cDCs and elimination of ESAM+CD4+ cDCs. These results indicate that deletion of RBPJ affected cDC development via loss of canonical Notch signaling, rather than via de-repression of non-Notch target genes. Histologically, deletion of Notch2 eliminated the characteristic clusters of CD11b+ cDCs in the marginal zone and bridging channels of the spleen32, leaving a distribution of cDCs loosely scattered throughout T cell zones and the red pulp (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3. Canonical Notch2 signaling is required for splenic and intestinal CD11b+cDC development.

(a) Splenocytes were stained for the indicated markers. Two-color histograms are shown for live cells pre-gated as indicated. Data are representative of three independent experiments (n = 6-8 mice per group). (b) Spleen sections from Notch2f/f and Notch2vav mice were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy for expression of CD11c, IgD and B220 (top) or CD11c and MadCAM-1 (bottom). Images are representative of two independent experiments (n = 4 mice). Scale bars, 200 μm. (c) Splenocytes were stained for the indicated markers. Data are representative of three independent experiments (n = 7 mice per group). (d) Quantification of cDC development in Notch2cKO mice from [c]. Bars represent cDCs per 1 × 106 splenocytes. Data are from three independent experiments (error bars, SEM; n = 7 mice per group, Student's t-test). (e) Lamina propria cells were stained for the indicated markers. Data are representative of three independent experiments (n = 3-5 mice per group). (f) Immunofluorescence images of CPs and ILFs from small intestine sections stained for CD11c, CD90 and DAPI. Images are representative of two independent experiments (n = 5 mice). Scale bars, 50 μm. CP, cryptopatch. * P < 0.01, ** P < 0.001.

Since loss of Notch2 also impacts the development of additional hematopoietic lineages33, we used CD11c-Cre in place of Vav1-Cre to restrict the impact of Notch2 deletion to myeloid lineages for analysis of cDC function during infection in vivo. Deletion of Notch2 by CD11c-Cre (Notch2cKO) generated identical defects in cDC development as seen in Vav1-Cre-induced Notch2 deletion (Fig. 3c,d), but prevented effects on other hematopoietic lineages (Supplementary Fig. 2). Splenic cDCs in Notch2cKO mice were decreased in number and ESAM+CD4+ cDCs were absent. A fraction of CD24+ cDCs also expressed ESAM and was dependent on Notch2 signaling (Fig. 3c), suggesting that Notch2 acts similarly, although to different extents, in the development of both the CD11b+ and CD8α+ branches of cDCs. Notch2-dependent ESAM+ cDCs were abundant not only in the spleen, but also in the resident cDC fraction in the MLN (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Similarly, a small fraction of resident ESAM+, Notch2-dependent cDCs was present in skin-draining lymph nodes (SLNs) (Supplementary Fig. 2a). In contrast, migratory dermal-derived cDCs in SLNs and peripheral tissue-resident cDCs in the lung and kidney were not affected by Notch2 deletion (Supplementary Fig. 2b)18. In the intestinal lamina propria, Notch2 deletion severely decreased the frequency of CD103+CD11b+ cDCs (Fig. 3e). By comparison, Batf3−/− mice selectively lacked the complementary lamina propria CD103+CD11b− cDC subset34 (Fig. 3e) but retained normal numbers of CD103+CD11b+ cDCs. Similarly, migratory CD103+CD11b+ cDCs in the MLNs were substantially reduced in Notch2cKO mice, and CD103+CD11b− cDCs were absent in Batf3−/− mice (Fig. 3e). The development of cryptopatches and ILFs containing CD11c+ cDCs and ILCs was unaffected in Notch2cKO mice (Fig. 3f, Supplementary Fig. 2d), consistent with a report that CD11b+ DCs are present within the lamina propria and not within ILFs35. Thus, Notch2cKO mice provide an in vivo system for analysis of CD11b+ cDC function in the presence of intact lymphoid structures.

Notch2 controls terminal differentiation of cDC subsets

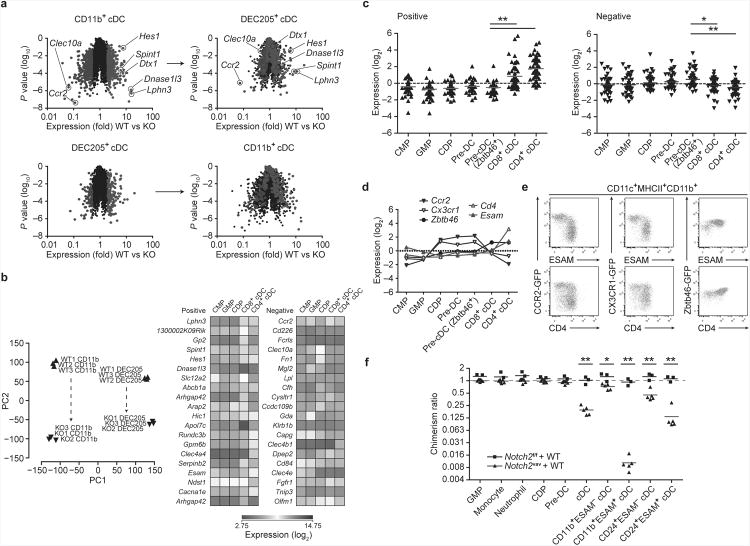

Although the role of Notch2 in cDC development was previously thought to be limited to the CD11b+ subset of cDCs18, we observed that Notch2cKO mice also showed defects in the CD8α+ cDC subset (Fig. 3c). Since CD8α expression can be altered upon manipulation of the Notch pathway36, we used CD24 and DEC205 expression to identify this subset of cDCs (Supplementary Fig. 3a). To examine the transcriptional effects of Notch2, we analyzed gene expression in both CD11b+ and DEC205+ cDCs from wild-type and Notch2cKO mice (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 3a). As expected, substantial changes were found between wild-type CD11b+ cDCs and Notch2cKO CD11b+ cDCs. In particular, known Notch targets such as Hes1 and Dtx1 were decreased in expression in Notch2cKO CD11b+ cDCs, as were cDC-specific genes such as Lphn3, Spint1 and Dnase1l3 (Fig. 4a). The majority of genes regulated by Notch2 in CD11b+ cDCs were also regulated by Notch2 in DEC205+ cDCs (Fig. 4a). In CD11b+ cDCs, Notch2 influenced gene expression in both ESAM+ and ESAM− fractions (Supplementary Fig. 3b), suggesting that Notch2 acts early following differentiation of the CD11b+ cDC subset from pre-cDCs, before induction of ESAM expression, and that its actions are not simply restricted to the development of an ESAM+ subset. Likewise, in DEC205+ cDCs, Notch2 regulated the same set of genes in both ESAM+ and ESAM− fractions, which largely overlapped with genes regulated in CD11b+ cDCs (Supplementary Fig. 3b).

Figure 4. Notch2 controls terminal differentiation of CD11b+ and DEC205+cDCs.

(a) Shown is microarray analysis of sorted cDC subsets from Notch2f/f (WT) and Notch2cKO (KO) mice. CD11b+ DCs were sorted as MHCII+CD11c+CD24−CD11b+ cells. DEC205+ DCs were sorted as MHCII+CD11c+CD24+CD11b−DEC205+ cells. Colored points represent genes increased more than 2-fold (red) or decreased more than 2-fold (blue) in the indicated cDC subset (left) and then plotted in the complementary subset (right). Data are from two independent experiments (n = 3 biological replicates per cell type in both WT and KO mice, Welch's t-test). (b) Left: PCA of WT and KO CD11b+ cDCs and DEC205+ cDCs, analyzed by individual replicate. Proportion of variance: PC1 54.0%, PC2 21.0%. Right: Heat map showing log-transformed expression values from progenitors and cDC subsets derived from the ImmGen database for probesets corresponding to the 20 most positive and negative loadings in PC2. (c) Shown are mean-centered, log-transformed expression values from DC progenitors and subsets for probesets corresponding to the 50 most positive and negative loadings in PC2. Each symbol represents a unique gene (bars, mean; Kruskal-Wallis test, Dunn's multiple comparison test). (d) Expression of selected loadings from [c] were analyzed by gene expression derived from the ImmGen database (left) and by flow cytometry of splenic CD11b+ cDCs in Ccr2gfp,Cx3cr1gfp, and Zbtb46gfp mice (right). Flow cytometry data are representative of three independent experiments (n = 5-6 mice per group). (e) Mixed BM chimeras were generated from CD45.2+Notch2vav BM and CD45.1+ WT BM or from CD45.2+Notch2f/f and CD45.1+ WT BM. Bone marrow progenitors and splenocytes were analyzed for donor contribution 8-10 weeks following lethal irradiation and transplant. Shown is the contribution of Notch2vav BM or Notch2f/f BM to each cell-type as a ratio of LSK chimerism in the same animal (% CD45.2+ contribution in cell-type/% CD45.2+ in LSK). Monocyte, neutrophil and cDC chimerism was analyzed in splenocytes. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. Data are from two individual experiments (bars, mean; n = 3-5 mice per group, Student's t-test). * P < 0.01, ** P < 0.001.

Principal component analysis (PCA) showed that similar genes were influenced by Notch2 deficiency in CD11b+ cDCs as in DEC205+ cDCs (Fig. 4b). PC1 segregated cDCs by lineage subset, distinguishing CD11b+ cDCs from DEC205+ cDCs. In contrast, PC2 segregated both cDC lineages by the presence or absence of Notch2 signaling, distinguishing wild-type cDCs from Notch2-deficient cDCs within each lineage (Fig. 4b). Next, we examined the expression of genes most heavily weighted in PC2 along the developmental pathway from common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) to splenic cDCs. Genes with the highest loadings in PC2, and thus induced by Notch2, were highly expressed in terminally differentiated cDCs but were expressed at low abundance in DC progenitors (Fig. 4c,d). Conversely, genes with the most negative loadings in PC2 were expressed highly in progenitors. Using knock-in GFP reporter mice for two such genes, Ccr2 and Cx3cr1, we found that CD11b+ESAM+ cDCs that are depleted in Notch2cKO mice were distinguished from CD11b+ESAM− cDCs on the basis of GFP expression (Fig. 4e, top). Similarly, two populations could also be distinguished on the basis of GFP and CD4 expression (Fig 4e, bottom). These subsets are likely to reflect true differences in CD11b+ cDC maturity since Zbtb46, which is expressed at intermediate abundance in cDC progenitors and upregulated in mature cDCs16, was more highly expressed in the ESAM+ fraction of CD11b+ cDCs (Fig. 4d,e). Accordingly, both ESAM+ and ESAM− cDCs developed from wild-type common dendritic cell progenitors (CDPs) and pre-DCs in vivo, supporting a model in which Notch2 influences terminal cDC differentiation of pre-DC-derived cells (Supplementary Fig. 4a,b).

To evaluate the stage at which Notch2 first affected cDC development, we analyzed competitive mixed BM chimeras generated from wild-type and Notch2vav donors, in the latter of which Notch2 is deleted at an early stage of hematopoietic development (Fig. 4f). We observed equal competition between wild-type and Notch2vav progenitors for cells in the LSK fraction and up to the pre-DC stage of DC development (Fig. 4f, Supplementary Fig. 5a). However, in the mature splenic cDC compartment, wild-type cells outcompeted Notch2vav cells (Fig. 4f, Supplementary Fig. 5b), indicating that Notch2 first affects development after the pre-DC. This effect was seen in both CD11b+ and CD8α+ subsets of mature cDCs, and further, in both ESAM+ and ESAM− fractions of each cDC subset. In summary, gene expression and competitive BM chimera analysis indicate that Notch2 acts in the terminal differentiation of CD11b+ and CD8α+ cDCs.

Expansion of Notch2-dependent cDCs is mediated by LTβR

Since Notch2 signaling controlled terminal cDC differentiation in the spleen and intestine, its effects should be subsequent to those of Flt3L signaling, which can be observed in the expansion of DC progenitors in the BM37. To test this hypothesis, we compared wild-type and Flt3l−/− mice for development of Notch2-dependent cDC subsets (Supplementary Fig. 6a,b). As expected, Flt3l−/− mice showed severe reductions in all subsets of cDCs, including CD11b+ESAM+ cDCs. However, treatment of wild-type mice with Flt3L caused a 25-fold increase in the number of CD11b+ESAM− cDCs, but only a 2.5-fold increase in the number of CD11b+ESAM+ cDCs (Supplementary Fig. 6c,d). Thus, Flt3L was necessary but not sufficient for development of CD11b+ESAM+ cDCs, suggesting that Notch2 regulates a step in cDC development subsequent to the actions of Flt3L.

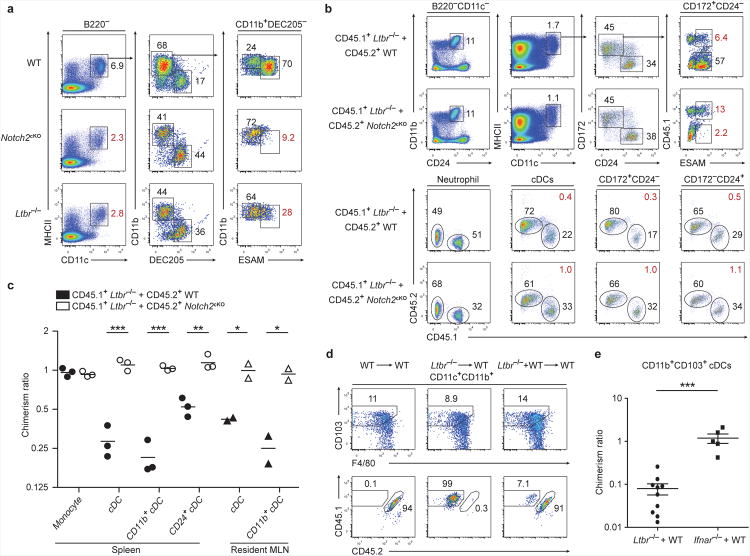

Because LTα1β2 is required for the proliferation of splenic CD8− cDCs located within the marginal zone and bridging channels38, we tested whether both Notch2 and LTβR signaling selectively influenced the same cDC subset. We compared wild-type, Notch2cKO and Ltbr−/− mice for the development of splenic cDC subsets. Ltbr−/− mice, similar to Notch2cKO mice, showed a decrease in CD11c+MHCII+ cDCs and CD8α+ cDCs and a substantial decrease in ESAM+CD4+ cDCs (Fig. 5a). Similarly, Nik−/− mice, which are deficient in non-canonical NF-κB activation downstream of LTβR signaling, and Nfkb1−/− mice, which lack the p105 NF-κB subunit, showed selective loss of ESAM+ cDCs but retained ESAM− cDCs (Supplementary Fig. 7a,b). These defects were not observed in mice lacking the tumor necrosis factor receptor family member CD40 (Supplementary Fig. 7a), which can also activate NF-κB39. Since Ltbr−/− mice lack lymph nodes and Peyer's patches40, we asked whether the loss of ESAM+ cDCs in these mice was cell-intrinsic by analyzing mixed BM chimeras generated from wild-type and Ltbr−/− BM. We observed that Ltbr−/− BM was markedly outcompeted by wild-type BM in the generation of splenic and MLN-resident CD11b+ cDCs (Fig. 5b,c), and further, that Ltbr−/− CD8α+ cDCs were also outcompeted by wild-type BM in this setting (Fig. 5b,c). Thus, Ltbr−/− BM and Notch2cKO BM showed a similar competitive disadvantage relative to wild-type BM in the generation of both branches of cDCs. To evaluate the epistatic relationship between Notch2 and LTβR signaling, we examined cDC development in mixed BM chimeras generated from Notch2cKO and Ltbr−/− BM. In these mixed chimeras, CD11b+ cDCs in the spleen and MLN developed equally from both Notch2cKO and Ltbr−/− BM (Fig. 5b,c). Similarly, CD8α+ cDCs from either donor also developed equally. These results suggest that Notch2 and LTβR act along a similar pathway in cDC development. Furthermore, in these mixed chimeras, Notch2cKO BM failed to generate any ESAM+ cDCs, whereas Ltbr−/− BM generated a small population of ESAM+ cDCs, suggesting that the requirement for Notch2 precedes the requirement for LTβR (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Fig. 7c). In this model, Ltbr−/− cDCs are able to activate Notch2 signaling and progress to an ESAM+ subset but are unable to undergo homeostatic expansion, resulting in decreased fitness relative to wild-type cDCs; in contrast, Notch2cKO cDCs are unable to progress to ESAM+ cells or undergo LTα1β2-mediated expansion. Given these results, we asked if LTβR also played a similar role in development of Notch2-dependent CD103+CD11b+ cDCs in the lamina propria. Indeed, Ltbr−/− BM was outcompeted by wild-type BM in mixed chimeras for the production of CD103+CD11b+ cDCs, unlike mice deficient in the IFN-αβ receptor (Ifnar−/−), which did not show defects in cDC development (Fig. 5d,e). Thus, LTβR signaling is required for the expansion of Notch2-dependent cDC subsets.

Figure 5. LTβR signaling mediates the homeostatic expansion of Notch2-dependent cDCs.

(a) Splenocytes were stained for the indicated markers. Two-color histograms are shown for live cells pre-gated as indicated. Data are representative of three independent experiments (n = 6 mice per group). (b,c) Mixed BM chimeras were generated with either Ltbr−/− and WT BM or with Ltbr−/− and Notch2cKO BM, and splenocytes or MLN cells were analyzed 8-10 weeks after lethal irradiation and transplant. (b) Shown are two-color histograms for live cells pre-gated as indicated above each diagram (neutrophil: CD11c− CD11b+CD24+). Lower plots indicate representative chimerism ratios (red values). (c) Quantification of mixed chimeras from [b]. Shown is the contribution of Ltbr−/− BM to each indicated cell-type as a ratio of neutrophil chimerism in the same animal (% CD45.1+Ltbr−/− contribution in cell-type/% CD45.1+Ltbr−/− in splenic neutrophils). Each symbol represents an individual mouse. Data are from two independent experiments (bars, mean; n = 2-3 mice per group, Student's t-test). (d) Lamina propria cells from the indicated BM chimeras were stained and the contribution of WT or Ltbr−/− BM to lamina propria CD103+CD11b+ cDCs was assessed (Ltbr−/− = CD45.1+, WT = CD45.1+CD45.2+). (e) Quantification of mixed chimeras generated with Ltbr−/− and WT BM from [d] and of chimeras generated with Ifnar−/− and WT BM. Chimerism ratio is calculated as (% contribution WT/KO in intestinal cDCs)/(% contribution WT/KO in splenic T cells). Each symbol represents an individual mouse. Data are from five independent experiments (bars, mean ± SEM; Ltbr−/− n = 10 mice, Ifnar−/− n = 5 mice, Student's t-test). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

CD11b+ cDCs orchestrate early immunity to A/E pathogens

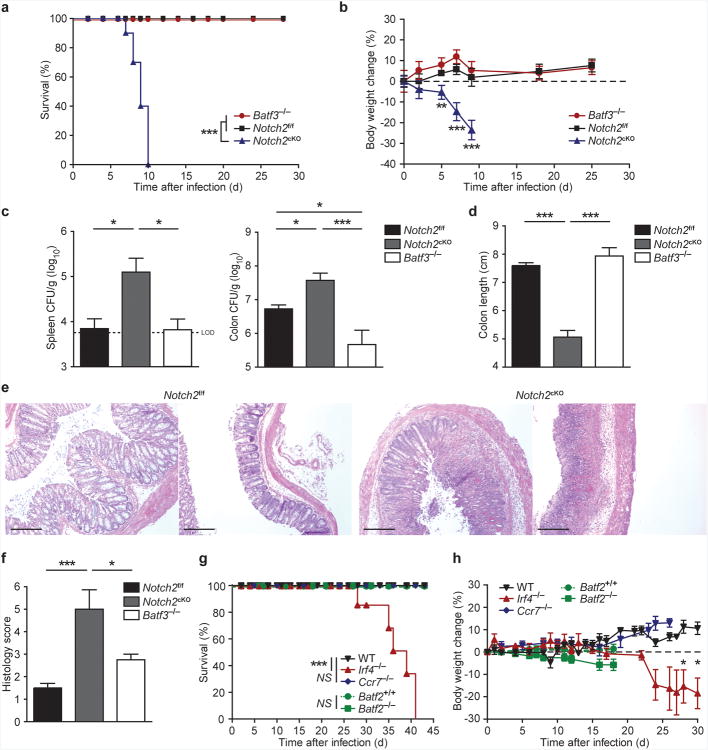

Since Notch2cKO and Batf3−/− mice lacked CD103+CD11b+ and CD103+CD11b− cDCs, respectively, we asked whether either subset was specifically required for host defense against an A/E bacterial pathogen. We compared the survival of wild-type, Batf3−/− and Notch2cKO mice following oral infection with C. rodentium (Fig. 6a). While wild-type and Batf3−/− mice were resistant to infection, Notch2cKO mice were highly susceptible to infection, which caused lethality within 7-10 days. Unlike wild-type or Batf3−/− mice, Notch2cKO mice showed rapid weight loss after infection, and when sacrificed at day 9, had significantly increased pathogen burden and shortened colonic length (Fig. 6b-d, Supplementary Fig. 8a,b). Colons of Notch2cKO mice showed higher inflammatory cellular infiltration and crypt elongation, scattered loss of mucosal architecture, and ulceration and coagulation necrosis, unlike wild-type mice (Fig. 6e,f). We recently identified Batf3-independent CD8α+ cDC development during infection by intracellular pathogens such as Listeria monocytogenes, which occurs due to compensation by the AP-1 factor Batf2 (ref. 41). However, CD103+CD11b− cDCs were not restored in Batf3−/− mice during infection by C. rodentium and Batf2−/− mice survived infection without substantial weight loss, suggesting that resistance to this A/E pathogen does not require compensatory CD8α+ cDC development (Fig. 6g,h).

Figure 6. Notch2-dependent CD11b+cDCs are essential for host defense against C. rodentium infection.

(a,b) Survival (a) and weight loss (b) of mice orally inoculated with 2 × 109 c.f.u. C. rodentium. Data are from three independent experiments (bars, SEM; n = 9-10 mice per group, Survival: log-rank Mantel-Cox test, weight loss: Student's t-test). (c)C. rodentium titers in the spleen and colon 9 days after inoculation. Data are from two independent experiments (bars, SEM; n = 6-7 mice per group, one-way ANOVA, Tukey's multiple comparison test) (d) Colon lengths 9 days after infection. Data are from two independent experiment (bars, SEM; n = 3 mice per group, one-way ANOVA, Tukey's multiple comparison test). (e) H&E staining of colon sections 9 days after infection. Data are representative of two independent experiments (n = 6-7 mice per group). Scale bars, 200 μm. (f) Quantification of histological scores from [e] (bars, SEM; Kruskal-Wallis test, Dunn's multiple comparison test). (g, h) Survival (g) and weight loss (h) of mice infected with C. rodentium. Data are from two independent experiments (bars, SEM; WT n = 8, Ccr7−/− n = 5, Irf4−/−n = 6, Batf2−/− and Batf2+/+ n = 5, survival: log-rank Mantel-Cox test, weight loss: Student's t-test). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, NS not significant.

To ask whether CD103+CD11b+ cDCs required migration to draining lymph nodes for protection against C. rodentium, we examined Irf4−/− and Ccr7−/− mice26,42. Irf4−/− mice exhibit a selective defect in CD11b+ cDC migration from tissues to draining lymph nodes42. We confirmed that migratory CD103+CD11b+ cDCs were absent in MLNs from Irf4−/− mice, whereas lamina propria CD103+CD11b+ cDCs were present but reduced in number (Supplementary Fig. 8c). Irf4−/− mice survived C. rodentium infection until at least day 28 (Fig. 6g,h), which excludes cDC migration as a requirement for early resistance. These mice did eventually succumb to C. rodentium by day 42 after infection, perhaps due to defects in antibody responses2,43. Next, we analyzed Ccr7−/− mice, which have a general defect in cDC migration26 but intact antibody responses. These mice were completely resistant to C. rodentium infection (Fig. 6g,h), suggesting that protection against C. rodentium infection can be provided by the local actions of CD103+CD11b+ cDCs.

To test whether defects in mucosal immunity in Notch2cKO mice were specific to infection by C. rodentium, we infected these mice with T. gondii. In contrast to Batf3−/− mice, which are highly susceptible and uniformly succumbed by 9 days after infection22, Notch2cKO mice survived infection and were indistinguishable from wild-type controls (Supplementary Fig. 8d). These results demonstrate that CD103+CD11b+ cDCs are not required for T. gondii resistance, and that the functionality of Batf3-dependent CD103+CD11b− cDCs appears to be unaffected in Notch2cKO mice.

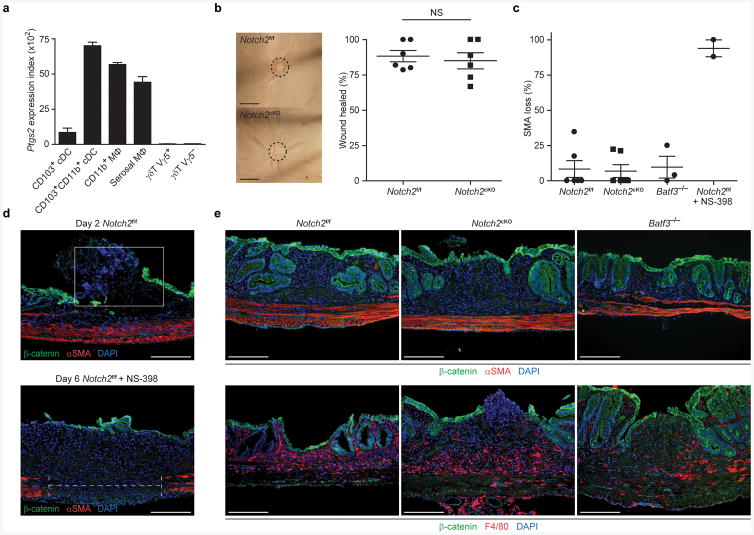

CD11b+ cDCs are not essential for healing mucosal wounds

We wondered whether the increased susceptibility to C. rodentium observed in Notch2cKO mice reflected local defects in colonic wound repair44 rather than in pathogen-specific immune defense. Colonic wound repair involves localized prostaglandin production by COX-2 (encoded by Ptgs2), which supports epithelial proliferation required for resolving inflammation45. We noted that both CD103+CD11b+ cDCs and macrophages in the intestine expressed Ptgs2 (Fig. 7a), suggesting that either cell type may be involved in supporting wound repair. Using endoscopy-guided mucosal excision to induce colonic injury, we found that Notch2cKO mice showed normal wound repair, as do wild-type and Batf3−/− mice, in contrast to wild-type mice treated with the COX-2 inhibitor NS-398 (Fig. 7b,c). COX-2 inhibition following mucosal excision resulted in failed regeneration of the β-catenin+ epithelial layer and impaired maintenance of the underlying α-SMA+ muscularis propria layer (Fig. 7d), as has been reported44. By contrast, wild-type, Notch2cKO and Batf3−/− mice showed normal epithelial regeneration and muscularis propria maintenance at day 6 following mucosal excision (Fig. 7e). Thus, cDCs were not required for prostaglandin production involved in wound repair, suggesting that susceptibility of Notch2cKO mice to C. rodentium infection is not due to defects in wound repair per se.

Figure 7. Notch2-dependent cDCs are dispensable for colonic wound repair.

(a) Shown are mean microarray expression values of Ptgs2 for the indicated cell types derived from the Immgen database55. Data are assembled from 2-4 replicate arrays (bars, SEM). (b) Whole mount images from colonic wounds 6 days after excision (left). Scale bars, 1 mm. Quantification of the percentage of wound bed sections with incomplete epithelial coverage at day 6 post-excision as measured by whole mount imaging (right). Data are from two independent experiments (bars, mean ± SEM; n = 6 mice per group, Student's t-test). Each symbol represents an individual mouse. (c) Shown is the percentage α-SMA loss underlying day 6 wound beds measured in histological sections (gap length/wound bed length). Data are from two independent experiments (bars, SEM; n = 3-6 mice per group). Each symbol represents an individual mouse. (d) Colonic sections from Notch2f/f or Notch2f/f mice treated with the COX-2 inhibitor NS-398 (5 μg/g) were stained for expression of β-catenin, α-SMA and DAPI on day 2 or day 6 post-excision. Data are representative of two independent experiments (n = 2-3 mice per group). Scale bars, 200 μm. (e) Colonic sections from Notch2f/f, Notch2cKO or Batf3−/− mice were stained for expression of β-catenin, α-SMA, DAPI and F4/80 6 days post-excision. Data are representative of two independent experiments (n = 3-6 mice per group). Scale bars, 200 μm. NS not significant.

CD11b+ cDCs regulate IL-23-dependent innate immunity

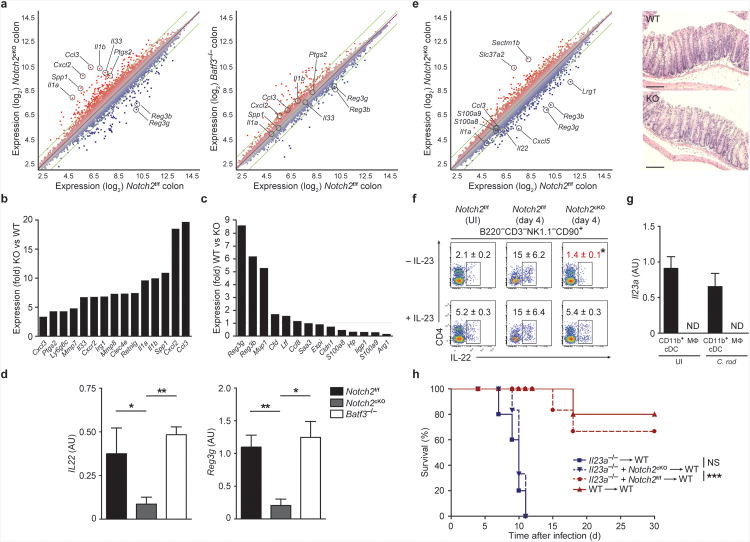

To determine the basis for susceptibility of Notch2cKO mice to C. rodentium infection, we analyzed gene expression changes in colonic cells isolated from wild-type, Batf3−/− and Notch2cKO mice 9 days after infection (Fig. 8a). Colonic gene expression in Notch2cKO mice showed a greater degree of change from wild-type mice than did colonic cells from Batf3−/− mice (Fig. 8a, Supplementary Table 1). Ptgs2 expression was not decreased in Notch2cKO mice 9 days after C. rodentium infection (Fig. 8a,b), consistent with intact wound healing demonstrated above (Fig. 7e). However, Notch2cKO mice showed upregulation of numerous inflammatory genes, including Il1a, Il1b, Il33, and Ccl3, and substantial downregulation of the antimicrobial peptide-encoding genes Reg3b and Reg3g (Fig. 8a-c). Notably, among the set of genes that were previously shown to be induced by IL-22 stimulation of colonic cells ex vivo, only Reg3b, Reg3g and Mup1 were decreased in colons of infected Notch2cKO mice, illustrating the importance of these molecules in defense to A/E pathogens2 (Fig. 8c). Genes encoding the antimicrobial peptides S100A8 and S100A9 were increased in Notch2cKO mice, consistent with a previous report indicating their insufficiency in defense against C. rodentium2. Consistent with these findings, IL-22 production was dramatically reduced in Notch2cKO mice, but not in Batf3−/− mice, 9 days after C. rodentium infection (Fig. 8d). To eliminate the impact of inflammation on gene expression, we also assessed changes in gene expression at day 4 after infection, a time at which no change in histology, pathogen dissemination, colonic length or lethality had occurred (Fig. 8e, Supplementary Fig. 8e,f). Again, Notch2cKO mice showed decreased expression of Il22 and the IL-22-responsive antimicrobial peptide genes Reg3b and Reg3g. ILCs isolated from Notch2cKO mice showed decreased intracellular expression of IL-22 protein at day 4; however, this effect was rescued by addition of IL-23 ex vivo, indicating that decreases in IL-22 production were extrinsic to ILCs in Notch2cKO mice (Fig. 8f).

Figure 8. Notch2-dependent CD11b+cDCs regulate IL-23-dependent antimicrobial responses to C. rodentium.

(a-c) Microarray analysis of colonic cells in mice infected with C. rodentium for 9 days. Shown are M-plots generated using ArrayStar software comparing gene expression between the indicated samples. (b,c) Shown is the average fold change of selected genes from [a]. Selected inflammatory genes increased in expression in Notch2cKO (KO) relative to Notch2f/f (WT) mice are shown (left). Expression of previously described IL-22-stimulated genes2 are shown (right). Data are from one independent experiment (n = 2-3 biological replicates per sample). (d) Shown is the normalized expression value of Il22 and Reg3g mRNA determined by qRT-PCR (mRNA/HPRT) for colons isolated from mice infected with C. rodentium for 9 days. Data are from three independent experiments (bars, SEM; n = 6-7 mice per group, one-way ANOVA, Tukey's multiple comparison test). (e) Microarray analysis of colonic cells in mice infected with C. rodentium for 4 days (left). Shown is an M-plot comparing gene expression between the indicated samples. Data are from one independent experiment (n = 2 biological replicates per sample). Shown are representative H&E staining of colons from mice infected for 4 days (right). Data are representative of two independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). Scale bars, 100 μm. (f) Intracellular IL-22 expression in MLN ILCs from uninfected (UI) or day 4 infected mice. Cells were stimulated ex vivo with PMA and ionomycin, with or without addition of IL-23. Shown are two color histograms for live cells pre-gated as indicated above each diagram. Data are representative of two independent experiments (n=4 mice per group). (g) Shown is the normalized expression value of Il23a mRNA determined by qRT-PCR (Il23a/HPRT) from lamina propria CD11b+ cDCs (CD11c+MHCII+CD103+CD11b+) and macrophages (Mac, CD11c+MHCII−CD11b+F4/80+) sorted from uninfected mice or mice infected with C. rodentium for 2 days (C. rod). Data are from two independent experiments (bars, SEM; n = 3 mice per group). (h) Survival of mixed bone marrow chimeras orally inoculated with 2 × 109 C. rodentium 8-10 weeks after lethal irradiation and transplant. Data are from two independent experiments (n = 5-6 per group, log-rank Mantel-Cox test). ND not detected, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, NS not significant.

Il23a−/− mice are susceptible to infection by C. rodentium1,2 and intestinal CD103+CD11b+ cDCs have been reported to produce IL-23 in vivo after TLR5 stimulation13. However, the requirement for these cells as an obligate source of IL-23 during A/E bacterial infections remains unclear. Functional IL-23 is a heterodimeric protein composed of p19 (encoded by Il23a) and p40 (encoded by Il12b). In the lamina propria, we found that Il23a was specifically expressed in CD11b+CD103+ cDCs in the steady state and 2 days after infection by C. rodentium, but this transcript was undetectable in macrophages in either setting (Fig. 8g). In addition, we found that intracellular expression of p40 was undetectable in CD11b+ cDCs at steady state but significantly increased upon activation (Supplementary Fig. 8g,h). The inducible expression of p40 or Il12b was not dependent on the presence of CD8α+ cDCs or on the transcription factors Batf, Batf2 and Batf3 (Supplementary Fig. 8g,h). Thus, expression of IL-23 was both inducible upon activation and restricted to the CD11b+ cDC subset.

To test whether Notch2-dependent cDCs were an obligate source of IL-23 during C. rodentium infection, we generated mixed BM chimeras with wild-type BM and Il23a−/− BM or with Notch2cKO BM and Il23a−/− BM and analyzed resistance to C. rodentium. In Notch2cKO:Il23a−/− mixed chimeras, intestinal CD103+CD11b+ cDCs develop only from the Il23a−/− BM, but all other hematopoietic populations are unaffected in their capacity to generate IL-23. Survival of wild-type:Il23a−/− chimeras upon infection by C. rodentium was similar to that of wild-type radiation chimeras; however, survival of Notch2cKO:Il23a−/− mixed chimeras was similar to that of Il23a−/− chimeras, which succumbed to C. rodentium 7-11 days after infection (Fig. 8h). The observation that Notch2cKO:Il23a−/− mixed chimeras were as susceptible to C. rodentium infection as Il23a−/− chimeras suggests that Notch2-dependent CD11b+CD103+ cDCs are the critical source of IL-23 required for protection.

Discussion

Efforts to distinguish the functions of macrophages and DCs have been limited by the availability of systems that selectively deplete each lineage in vivo46. Recently developed genetic models have led to the characterization of non-redundant roles for CD8α+ cDCs and for pDCs17-19, but a unique role for CD11b+ cDCs has not been studied using a selective depletion model in vivo. Here, we used the Notch2-dependence of CD11b+ cDCs to analyze their role in host defense. We observed that Notch2-dependent CD103+CD11b+ cDCs, but not Batf3-dependent CD103+CD11b− cDCs, were required for IL-23 production to protect the host from early susceptibility to C. rodentium infection. This role in innate defense was pathogen-specific, since CD103+CD11b+ cDCs were not necessary for resistance to T. gondii or for healing of intestinal mucosa following injury. Since CD103+CD11b+ cDCs in the villi did not appear to extend processes into the intestinal lumen, these cDCs may require mucosal breach for activation. These findings settle an unresolved question regarding the critical source of IL-23 required for driving IL-22-dependent antimicrobial responses to A/E infections2. Since IL-22 also acts in other host defense processes such as chronic inflammatory skin diseases6, it would be interesting to examine the requirement for CD11b+ cDCs in these settings as well.

Based on our observation that Notch2 also regulated gene expression in CD8α+ cDCs, we tested whether defects in these cDCs could account for early susceptibility to C. rodentium. However, Batf3−/− and Batf2−/− mice showed normal resistance to C. rodentium. We also excluded a role for other Notch2-independent cDCs. In the absence of Notch2, some CD11b+ cDCs developed in the spleen; likewise, Zbtb46-expressing CD103−CD11b+ cDCs may have also developed in the intestine. However, any Notch2-inexperienced CD11b+ cDCs remaining in Notch2cKO mice were insufficient for IL-23 production and protection against C. rodentium infection. Notch signaling also regulates development of IL-22-producing ILCs47,48, but we showed that ILC function was not impacted by CD11c-Cre-mediated deletion of Notch2. Nonetheless, this dual role of Notch signaling in defense against A/E infections might represent a coordinated immune strategy involving the intentional expression of Notch ligands within pathogen-responsive cellular niches.

Antibody blockade of LTβR in vivo has also been found to reduce IL-23 production during C. rodentium infection49, and conditional deletion of Ltbr by CD11c-Cre increases susceptibility to this pathogen11,50. In addition, a previous study reports a requirement for LTβR in CD4+ cDC homeostasis in the spleen38. These results suggested a possible relationship between Notch2 and LTβR signaling in cDC differentiation. Indeed, we found that LTβR, but not Flt3L, selectively influenced the development of splenic ESAM+ and intestinal CD103+CD11b+ cDCs. It was previously shown that loss of LTβR signaling directly impairs Il23a gene expression by DCs11. However, our results suggest that LTβR signaling may also control the development of CD103+CD11b+ cDCs, which are a source of IL-23, independent of any effects on Il23a expression.

The tissue-resident CD11b+ cDCs critical for early defense against C. rodentium are affected in Zbtb46DTR, Notch2cKO and Flt3l−/− mice, and so appear to derive from the pre-cDC, rather than monocytes. However, our demonstration that Notch2-dependent CD11b+ cDCs are required for IL-23-dependent protection against C. rodentium does not exclude important contributions from macrophages and monocyte-derived cells. Indeed, monocytes play a protective role in eradication of C. rodentium following their recruitment to the lamina propria during later stages of infection51. So while DC-derived IL-23 may be critical early, monocyte-derived Zbtb46+ cDCs31 can produce IL-6 (ref. 52), which could support CD4+ T cell-derived IL-22 production later in infection53. Our observation that Ccr2−/− mice, which had reduced lethality relative to Notch2cKO mice, yet still showed weight loss, agrees with a model in which monocytes are important in immune responses to C. rodentium. Thus, it will be important to characterize non-redundant functions of pre-cDC-derived and monocyte-derived cells in resistance to infection by A/E bacteria.

The role for cDCs in immune defense has been thought to reside primarily in their capacity for priming CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses54. The results presented here, along with the similar requirement for CD8α+ cDCs in IL-12 production for early innate protection against T. gondii, now demonstrate that both branches of cDCs are also critical for the initiation of innate immunity. These findings may indicate that the DC lineage separated from monocytes and macrophages before the emergence of adaptive immunity, and that it plays a dedicated role in orchestrating the reactions of the expanding family of ILCs3.

Online Methods

Mice

All animals were bred and maintained in a specific pathogen-free animal facility according to institutional guidelines and with protocols approved by the Animal Studies Committee at Washington University in St. Louis. The generation of Zbtb46gfp and Zbtb46DTR mice was described previously15,16. For cDC depletion in Zbtb46DTR mice, 40 ng/g DT (Sigma) was administered on day -3 and day -1 prior to analysis on day 0. For cDC depletion during C. rodentium infections, mice were injected with 20 ng/g DT one day prior to infection, and 5 ng/g doses were given every 2-3 days thereafter to maintain depletion. The following mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories: CD11c-cre (B6.Cg-Tg(Itgax-cre)1-1Reiz/J), Vav1-cre (B6.Cg-Tg(Vav1-cre)A2Kio/J), Notch2f/f (B6.129S-Notch2tm3Grid/J), Ccr2−/−(B6.129S4-Ccr2tm1Ifc/J), Cd40−/− (B6.129P2-Cd40tm1Kik/J), Nfkb1−/− (B6;129P-Nfkb1tm1Bal/J), Ccr7−/− (B6.129P2(C)-Ccr7tm1Rfor/J) and Cx3cr1gfp (B6.129P-Cx3cr1tm1Litt/J). The generation of Rbpjf/f, Psen1f/f and Psen2−/− mice was described previously56,57. Flt3l−/− (C57BL/6-flt3Ltm1Imx) mice were obtained from Taconic. Generation of Il23−/− mice was described previously2. Generation of Ltbr−/− mice was described previously40. Generation of Batf−/−, Batf2−/− and Batf3−/− mice was described previously17,41. Generation of Nik−/− mice was described previously58 and KO mice were a kind gift from B. Sleckman (Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO). Ifnar1−/− mice were a kind gift from T. Watts (University of Toronto, Toronto, ON). To generate Ccr2-eGFP KI mice, a targeting construct was designed to insert a DNA fragment encoding eGFP followed by a polyadenylation signal and a loxP-flanked neomycin resistance cassette at the translation start site of Ccr2. The construct was electroporated into LK-1 (C57BL/6J) ES cells59, and one correctly targeted cloned was identified by Southern blot analysis and used to generate chimeras. Chimeras were bred to CMV-Cre transgenic mice (B6.C-Tg(CMV-Cre)1Cgn/J, Jackson Laboratories)60 to remove the neomycin resistance cassette. To generate Irf4−/− mice, Irf4f/f mice (B6.129S1-Irf4tm1Rdf/J) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories and crossed to CMV-Cre mice. For BM chimera experiments, CD45.1+ B6.SJL (B6.SJL-PtprcaPepcb/BoyJ) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories. Unless otherwise indicated, experiments were performed with sex-matched littermate mice at 8-12 weeks of age. Unirradiated mice used for C. rodentium experiments weighed less than 20 g when infected unless otherwise specified.

DC preparation

Lymphoid organ and non-lymphoid organ DCs were harvested and prepared as previously described16. Briefly, spleens, MLNs, SLNs (inguinal) and kidneys were minced and digested in 5 ml Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s media + 10% FCS (cIMDM) with 250 μg/ml collagenase B (Roche) and 30 U/ml DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at 37 °C with stirring. Cells were passed through a 70-μm strainer before red blood cells were lysed with ACK lysis buffer. Cells were counted on a Vi-CELL analyzer (Beckman Coulter), and 5–10 × 106 cells were used per antibody staining reaction. Lung cell suspensions were prepared after perfusion with 10 ml Dulbecco's PBS (DPBS) via injections into the right ventricle after transection of the lower aorta. Dissected and minced lungs were digested in 5 ml cIMDM with 4 mg/ml collagenase D (Roche) for 1 h at 37°C with stirring. Small intestine cell suspensions were prepared after removal of Peyer's patches and fat. Intestines were opened longitudinally, washed of fecal contents, cut into 1 cm pieces and incubated in HBSS medium (Life Technologies) + 2 mM EDTA at 37 °C for 40 min while rotating at 1 g. Tissue pieces were washed in DPBS, minced and incubated in RPMI medium + 2% FBS with collagenase VIII (100U/ml, Sigma, C2139) at 37 °C for 90 min with stirring. Cell suspensions were pelleted, suspended in 40% Percoll (Sigma, P4937), overlaid on 70% Percoll and centrifuged for 20 min at 850g. Cells in the interphase were recovered, washed in DPBS and stained. For Flt3L-mediated expansion, 10 μg Flt3L was injected intraperitoneally for two consecutive days, and organs were harvested after 7 d. For p40 induction, splenocytes were enriched for CD11c+ expressing cells using MACS beads (Miltenyi). Enriched cells were stimulated ex vivo with 1 μg/ml LPS (Sigma, L2630) and 50 ng/ml IFN-γ (PeproTech, 315-05) for 24 h. 1 μg/ml brefeldin A was added for the last 4 h. Cells were then washed, stained for expression of surface markers, permeabilized with 0.25% saponin and stained for intracellular p40.

Antibodies and flow cytometry

Staining was performed at 4 °C in the presence of Fc Block (clone 2.4G2, BD Biosciences) in flow cytometry buffer (DPBS + 0.5% BSA + 2 mm EDTA). The following antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences: APC anti-CD4 (RM4-5), V450 anti-GR1 (RB6-8C5), FITC anti-CD3ε (145-2C11), FITC anti-CD45.1 (A20), FITC anti-CD21/CD35 (7G6), PE-Cy7 anti-CD24 (M1/69), PE-Cy7 anti-CD8α (53-6.7) and APC anti-CD172a/SIRPα (P84). The following antibodies were purchased from eBioscience: PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-CD11b (M1/70), APC anti-CD90.2 (53-2.1), APC-eFluor780 anti-CD11c (N418), PE anti-CD23 (B3B4), PE anti-RORγt (AFKJS-9), PE anti-IL22 (1H8PWSR), PE anti-IL12/23 p40 (C17.8), PE anti-ESAM (1G8), eFluor450 anti-MHCII (I-A/I-E; M5/114.15.2), PE anti-CD103 (2E7), PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-CD16/32 (93), APC anti-CD45.2 (104), APC-eFluor780 anti-CD117 (2B8), PE anti-CD135 (A2F10), V500 anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), APC anti-F4/80 (B-M8), Alexa700 anti-Sca1 (D7) and PerCP-eFluor710 anti-Siglec-H (eBio440C). PE and APC anti-CD205/DEC205 (NLDC-145) were purchased from Miltenyi. Biotin anti-CD127 (A7R34) was purchased from BioXCell. In general, all antibodies were used at a 1:200 dilution. Anti-DEC205 was used at a 1:20 dilution. Cells were analyzed on BD FACSCantoII or FACSAriaII flow cytometers, and data were analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar, Inc.). For immunofluorescence experiments, the following reagents were purchased from Invitrogen: rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP (Cat. No. A11122), Alexa488 anti-rabbit IgG (Cat. No. A11034) and streptavidin Alexa555 (Cat. No. S32355). From BioLegend: Alexa647 anti-CD11c (N418). From Caltag: biotin anti-F4/80 (BM8). From eBioscience: Alexa488 and biotin anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), biotin anti-IgD (11-26) and biotin anti-MADCAM-1 (MECA-367). From Sigma: rabbit polyclonal anti-β-catenin (Cat. No. C2206) and Cy3 anti-α-SMA (1A4).

Citrobacter rodentium

Mice were infected with an intraoral inoculation of 2 × 109 c.f.u. C. rodentium strain DBS100 (ATCC) as previously described2. Survival and weight loss were monitored for 30-45 d. Survival studies were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines and with protocols approved by the Animal Studies Committee at Washington University in St. Louis. Colon lengths were measured from mice infected for 4 or 9 days. For histology, distal colons were collected and fixed overnight at 25 °C in 10% buffered formalin phosphate (4% (w/w) formaldehyde, 0.4% (w/v) sodium phosphate (monobasic monohydrate), 0.65% (w/v) sodium phosphate (dibasic anhydrous) and 1.5% (w/v) stabilizer methanol; SF100-4, Fisher Scientific), embedded in paraffin, sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For c.f.u. measurements, spleens and colons from uninfected mice or mice infected for 4 or 9 days were weighed, homogenized and serial dilutions were plated for 24 h at 37 °C in duplicate onto MacConkey agar (Sigma, M7408) plates. The severity of colitis (by histology on single-blinded samples) was assigned a score on a scale from 1 to 7. Scores correspond to the following descriptions: (1) no evidence of inflammation, (2) low level of cellular infiltration in <10% of the field, (3) moderate cellular infiltration in 10-25% of the field, crypt elongation, bowel wall thickening and no evidence of ulceration, (4) high level of cellular infiltration in 25-50% of field, thickening of bowel wall beyond muscular layer and high vascular density, (5) marked degree of infiltration in >50% of field, crypt elongation and distortion and transmural bowel thickening with ulceration, (6) complete loss of mucosal architecture with ulceration and loss of mucosal vasculature, (7) coagulation necrosis. For IL-22 expression in ILCs, MLN cells isolated from mice infected for 4 days were stimulated for 4 h with 50ng/mL PMA (Sigma, P1585) and 1 μM ionomycin (Sigma, I0634), with or without 10 ng/mL rIL-23 (RD Systems, 1887-ML-010), in the presence of 1 μg/ml brefeldin A (Sigma, B6542). Cells were washed with DPBS and stained for surface expression of specified markers. Cells were then fixed in 2% methanol-free PFA, permeabilized with 0.25% saponin and stained for intracellular IL-22 expression.

Toxoplasma gondii

The type II Prugniaud strain of T. gondii expressing a firefly luciferase and GFP transgene (PRU-FLuc-GFP) was used (kindly provided by J. Boothroyd, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA). The parasites were grown in human foreskin fibroblasts cultures as previously described61. For infections, freshly egressed parasites were filtered, counted, and 100 tachyzoites were injected intraperitoneally into mice. Survival was monitored for 30 days.

Endoscopy-guided mucosal excision

Mice were anesthetized, and colon lumens were visualized with a high-resolution miniaturized colonoscope system. After inflating the colon with DPBS, 3F flexible biopsy forceps were inserted into the sheath adjacent to the camera. 3–5 full-thickness areas of the entire mucosa and submucosa were removed from along the dorsal side of the colon. For this study, wounds that averaged approximately 1 mm2 (equivalent to 250–300 crypts) were evaluated. Wounded mice were sacrificed 2 or 6 days after injury, and each wound was frozen individually in optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT). Sections were made and fixed in 4% PFA, boiled in 10 mmol/L citrate buffer, rinsed in DPBS, blocked in 3% bovine serum albumin/0.1% Triton X-100 for 20 min and incubated with primary antibodies for 1 h. Slides were then rinsed with DPBS, incubated with secondary antibody followed by bis-benzimide staining and mounted with Mowiol 4-88 (EMD Chemicals, Billerica, MA). Sections were viewed with a Zeiss (Oberkochen, Germany) Axiovert 200 microscope equipped with an Axiocam MRM camera. The selective COX-2 inhibitor NS-398 (Cayman Chem) was dissolved in DMSO to prepare the stock solution. Stocks were further diluted in 5% NaHCO3, and 5 mg/kg doses were administered intraperitoneally daily following wounding.

BM progenitor isolation and cell transfer

Bone marrow was harvested from femurs, tibiae, humeri and pelvises. Bones were fragmented by mortar and pestle, and debris was removed by gradient centrifugation using Histopaque 1119 (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were passed through a 70-μm strainer and red blood cells lysed with ACK lysis buffer. Cells were counted on a Vi-CELL analyzer, and 5-10 × 106 cells were stained for analysis or the entire BM was stained for sorting. Gates used to define CMPs, CDPs and pre-DCs are based on previous studies62,63. CMPs were identified as Lin−ckithiSca-1−CD11c−CD135+CD16/32−CD127− cells. CDPs were identified as Lin−ckitintSca-1−CD135+CD16/32−CD127− cells. Pre-DCs were identified as Lin−ckitloSca-1−CD11c+CD135+CD16/32−CD127− cells. cDC-restricted pre-cDCs were identified as Zbtb46-GFP+ cells within the pre-DC gate. For cell purification by sorting, we used a FACSAriaII (BD Biosciences). Cells were sorted into DPBS supplemented with 0.5% BSA and 0.02% EDTA. Cell purities of at least 95% were confirmed by post-sort analysis. For transfer experiments, purified cell populations were transferred retroorbitally to congenically marked mice (CD45.1) following sublethal irradiation with 600 rads whole body irradiation.

Expression microarray analysis

Total RNA was isolated from cells using the Ambion RNAqueous-Micro Kit. For Mouse Gene 1.0 ST Arrays, RNA was amplified with the WT Expression Kit (Ambion) and labeled, fragmented and hybridized with the WT Terminal Labeling and Hybridization Kit (Affymetrix). Data were processed using RMA quantile normalization, and expression values were modeled using ArrayStar software (DNASTAR version 4). For principal component analysis, microarray datasets were pre-processed by ArrayStar using quantile normalization and robust multichip average (RMA) summarization, then replicates grouped by sample. Either log-transformed expression values from each replicate or mean log-transformed expression values from each replicate group were exported in tabular format, imported into R (version 2.13.2), mean-centered by gene, root mean square (RMS)-scaled by sample, transposed and subjected to principal component analysis computed by singular value decomposition without additional centering or scaling. Scores were plotted in R.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Gene expression analysis used colonic cells isolated from mice infected with C. rodentium for 2, 4 or 9 days. Day 9 Flt3L (200 ng/ml) BMDC cultures were stimulated with LPS and IFN-γ as described above. RNA and cDNA were prepared with RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). For Il23a expression in cDCs and macrophages, CD11b+ cDCs (Aqua−CD45+B220−CD11c+MHCII+CD103+CD11b+) and macrophages (Aqua−CD45+B220−CD11c+MHCII−CD11b+F4/80+) from mice infected for 2 d were sorted to > 95% purity. Total RNA was isolated from sorted cells using the Ambion RNAqueous-Micro Kit. Real-time PCR and StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) were used according to manufacturer's instructions with the quantitation standard-curve method and HotStart-IT SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Affymetrix/USB). PCR conditions were 10 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 two-step cycles consisting of 15 s at 95 °C and 1 min at 60 °C. Primers used for measurement of Il22, Reg3g, Il23a, Il12a, and Il12b expression were as follows: IL22 qPCR F, 5′-tgacgaccagaacatccaga-3′; IL22 qPCR R, 5′-cgccttgatctctccactct-3′; HPRT-F, 5′-TCAGTCAACGGGGGACATAAA-3′; HPRT-R, 5′-GGGGCTGTACTGCTTAACCAG-3′; IL23a-F, 5′-AATAATGTGCCCCGTATCCA-3′; IL23a-R, 5′-GGATCCTTTGCAAGCAGAAC-3′; IL12a-F: 5′-GTGAAGACGGCCAGAGAAA-3′; IL12a-R, 5′-GGTCCCGTGTGATGTCTTC-3′; IL12b-F, 5′-AGCAGTAGCAGTTCCCCTGA-3′; IL12b-R, 5′-AGTCCCTTTGGTCCAGTGTG-3′; Reg3g-F, 5′-ATCATGTCCTGGATGCTGCT-3′; and Reg3g-R, 5′-AGATGGGGCATCTTTCTTGG-3′.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Spleens and intestines were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 8 h, incubated in 30% sucrose/H2O overnight, embedded in OCT compound and 7-micron cryosections produced. Following two washes in DPBS, sections were blocked in CAS Block (Invitrogen, 00-8120) containing 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min at 21 °C. Sections were stained with primary and secondary reagents diluted in CAS Block containing 0.2% Triton X-100 and mounted with ProLong Gold Antifade reagent containing DAPI (Invitrogen, P36935). For CD11c staining, spleens were frozen without fixation and fixed in acetone at 4 °C for 15 min prior to washing in DPBS. Four-color epifluorescence microscopy was performed using a Zeiss AxioCam MRn microscope equipped with an A×10 camera. Monochrome images were acquired with AxioVision software using either 10× or 20× objectives and exported into ImageJ software for subsequent color balancing and overlaying.

Bone marrow chimeras

BM cells from donor mice were collected as described above, and 5-10 × 106 total BM cells were transplanted by retroorbital injection into wild-type B6.SJL recipients. For developmental competition experiments, recipients received a single dose of 1200 rad whole body irradiation on the day of transplant, and mice were analyzed 8-10 weeks later. For infection experiments, recipients received a split dose of 2 × 525 rad whole body irradiation 4 h apart on the day of transplant, and mice were infected 8-10 weeks later. For mixed BM competitions, BM from two genotypes were counted and mixed at a 1:1 ratio, and LSK cells were analyzed by flow cytometry to confirm 1:1 chimerism prior to transplant. Il23a−/− BM was distinguished from Notch2f/f or Notch2cKO BM by GFP expression. Ltbr−/− BM was distinguished by expression of CD45.1.

Statistical analysis

In general, differences between groups were analyzed with unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-tests. Results with P-values less than or equal to 0.05 were considered significant (GraphPad Prism, GraphPad Software, Inc.). Survival studies were analyzed with log-rank Mantel-Cox tests. For multiple comparisons, data were analyzed with one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test. The appropriate nonparametric test was used when data failed to meet assumptions for parametric statistics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the US National Institutes of Health (AI076427-02 to K.M.M., R01 GM55479 to R.K., R01 DE021255-01 and U01 AI095542-01 to M.C., R01 DK071619 to T.S.S. and R01 DK064798 to R.D.N.), the US Department of Defense (W81XWH-09-1-0185 to K.M.M.), the American Heart Association (12PRE8610005 to A.T.S. and 12PRE1205041912 to W.K.), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP 67157 to J.L.G. and FRN 11530 to C.J.G.) and the National Cancer Institute (P30 CA91842 for the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center). We thank B. Sleckman for Nik−/− mice, T. Watts for Ifna1r−/− mice, J. Boothroyd for PRU-FLuc-GFP, the ImmGen consortium for use of the ImmGen database54 and the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center at Washington University School of Medicine for use of the Center for Biomedical Informatics and Multiplex Gene Analysis Genechip Core Facility.

Non-standard abbreviations used

- cDC

classical dendritic cell

- pDC

plasmacytoid dendritic cell

- CMP

common myeloid progenitor

- CDP

common dendritic cell progenitor

- Flt3L

fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand

- MLN

mesenteric lymph node

- SLN

skin draining lymph node

- ILF

isolated lymphoid follicle

- ILC

innate lymphoid cell

- LTβR

lymphotoxin β receptor

- LCMV

lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus

Footnotes

Accession Codes: All original microarray data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database under accession number GSE45698.

Author Contributions: A.T.S. and K.M.M designed the study. A.T.S., C.G.B., J.S.L. and C.S. carried out experiments related to C. rodentium infection with guidance from W.O., M.C., and K.M.M. A.T.S., C.G.B. and D.N. carried out experiments related to Ltbr−/− mice with guidance from C.J.G. and J.L.G. N.A.M. carried out experiments related to wound healing with guidance from T.S.S. A.T.S. and X.W. carried out microarray analysis. A.T.S., S.R.T., W.K., W.L.L., M.T., T.L.M and K.G.M. carried out experiments related to cDC development in Notch2-, Irf4-, and Batf3-deficient mice with guidance from R.K., R.D.N., and K.M.M. A.T.S., C.G.B. and M.M.M. carried out Zbtb46gfp and Zbtb46DTR experiments with guidance from M.C.N. and K.M.M. A.T.S. and K.M.M. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors.

Competing Financial Interests: W.O. is an employee of Genentech.

References

- 1.Mangan PR, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta induces development of the T(H)17 lineage. Nature. 2006;441:231–234. doi: 10.1038/nature04754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng Y, et al. Interleukin-22 mediates early host defense against attaching and effacing bacterial pathogens. Nat Med. 2008;14:282–289. doi: 10.1038/nm1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spits H, Di Santo JP. The expanding family of innate lymphoid cells: regulators and effectors of immunity and tissue remodeling. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:21–27. doi: 10.1038/ni.1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colonna M. Interleukin-22-producing natural killer cells and lymphoid tissue inducer-like cells in mucosal immunity. Immunity. 2009;31:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sonnenberg GF, et al. CD4(+) lymphoid tissue-inducer cells promote innate immunity in the gut. Immunity. 2011;34:122–134. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng Y, et al. Interleukin-22, a T(H)17 cytokine, mediates IL-23-induced dermal inflammation and acanthosis. Nature. 2007;445:648–651. doi: 10.1038/nature05505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mundy R, et al. Citrobacter rodentium of mice and man. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:1697–1706. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cella M, et al. A human natural killer cell subset provides an innate source of IL-22 for mucosal immunity. Nature. 2009;457:722–725. doi: 10.1038/nature07537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eberl G, et al. An essential function for the nuclear receptor RORgamma(t) in the generation of fetal lymphoid tissue inducer cells. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:64–73. doi: 10.1038/ni1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanos SL, et al. RORgammat and commensal microflora are required for the differentiation of mucosal interleukin 22-producing NKp46+ cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:83–91. doi: 10.1038/ni.1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tumanov AV, et al. Lymphotoxin controls the IL-22 protection pathway in gut innate lymphoid cells during mucosal pathogen challenge. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manta C, et al. CX(3)CR1(+) macrophages support IL-22 production by innate lymphoid cells during infection with Citrobacter rodentium. Mucosal Immunol. 2012;6:177–88. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kinnebrew MA, et al. Interleukin 23 production by intestinal CD103(+)CD11b(+) dendritic cells in response to bacterial flagellin enhances mucosal innate immune defense. Immunity. 2012;36:276–287. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett CL, Clausen BE. DC ablation in mice: promises, pitfalls, and challenges. Trends Immunol. 2007;28:525–531. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meredith MM, et al. Expression of the zinc finger transcription factor zDC (Zbtb46, Btbd4) defines the classical dendritic cell lineage. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1153–1165. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Satpathy AT, et al. Zbtb46 expression distinguishes classical dendritic cells and their committed progenitors from other immune lineages. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1135–1152. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hildner K, et al. Batf3 deficiency reveals a critical role for CD8alpha+ dendritic cells in cytotoxic T cell immunity. Science. 2008;322:1097–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1164206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis KL, et al. Notch2 receptor signaling controls functional differentiation of dendritic cells in the spleen and intestine. Immunity. 2011;35:780–791. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swiecki M, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell ablation impacts early interferon responses and antiviral NK and CD8(+) T cell accrual. Immunity. 2010;33:955–966. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hashimoto D, Miller J, Merad M. Dendritic cell and macrophage heterogeneity in vivo. Immunity. 2011;35:323–335. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torti N, et al. Batf3 transcription factor-dependent DC subsets in murine CMV infection: differential impact on T-cell priming and memory inflation. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:2612–2618. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mashayekhi M, et al. CD8a+ Dendritic Cells Are the Critical Source of Interleukin-12 that Controls Acute Infection by Toxoplasma gondii Tachyzoites. Immunity. 2011;35:249–259. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cervantes-Barragan L, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells control T-cell response to chronic viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:3012–3017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117359109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bogunovic M, et al. Origin of the lamina propria dendritic cell network. Immunity. 2009;31:513–525. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Varol C, et al. Intestinal lamina propria dendritic cell subsets have different origin and functions. Immunity. 2009;31:502–512. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohl L, et al. CCR7 governs skin dendritic cell migration under inflammatory and steady-state conditions. Immunity. 2004;21:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jakubzick C, et al. Lymph-migrating, tissue-derived dendritic cells are minor constituents within steady-state lymph nodes. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2839–2850. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Randolph GJ, Ochando J, Partida-Sanchez S. Migration of dendritic cell subsets and their precursors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:293–316. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKenna HJ, et al. Mice lacking flt3 ligand have deficient hematopoiesis affecting hematopoietic progenitor cells, dendritic cells, and natural killer cells. Blood. 2000;95:3489–3497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boring L, et al. Impaired monocyte migration and reduced type 1 (Th1) cytokine responses in C-C chemokine receptor 2 knockout mice. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2552–2561. doi: 10.1172/JCI119798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zigmond E, et al. Ly6C hi monocytes in the inflamed colon give rise to proinflammatory effector cells and migratory antigen-presenting cells. Immunity. 2012;37:1076–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dudziak D, et al. Differential antigen processing by dendritic cell subsets in vivo. Science. 2007;315:107–111. doi: 10.1126/science.1136080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radtke F, Fasnacht N, MacDonald HR. Notch signaling in the immune system. Immunity. 2010;32:14–27. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edelson BT, et al. Peripheral CD103+ dendritic cells form a unified subset developmentally related to CD8alpha+ conventional dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2010;207:823–836. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McDonald KG, et al. Dendritic cells produce CXCL13 and participate in the development of murine small intestine lymphoid tissues. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:2367–2377. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caton ML, Smith-Raska MR, Reizis B. Notch-RBP-J signaling controls the homeostasis of CD8- dendritic cells in the spleen. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1653–1664. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waskow C, et al. The receptor tyrosine kinase Flt3 is required for dendritic cell development in peripheral lymphoid tissues. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:676–683. doi: 10.1038/ni.1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kabashima K, et al. Intrinsic lymphotoxin-beta receptor requirement for homeostasis of lymphoid tissue dendritic cells. Immunity. 2005;22:439–450. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Summers deLucaL, Gommerman JL. Fine-tuning of dendritic cell biology by the TNF superfamily. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:339–351. doi: 10.1038/nri3193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Futterer A, et al. The lymphotoxin beta receptor controls organogenesis and affinity maturation in peripheral lymphoid tissues. Immunity. 1998;9:59–70. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80588-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tussiwand R, et al. Compensatory dendritic cell development mediated by BATF-IRF interactions. Nature. 2012;490:502–507. doi: 10.1038/nature11531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bajana S, et al. IRF4 promotes cutaneous dendritic cell migration to lymph nodes during homeostasis and inflammation. J Immunol. 2012;189:3368–3377. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klein U, et al. Transcription factor IRF4 controls plasma cell differentiation and class-switch recombination. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:773–782. doi: 10.1038/ni1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manieri NA, et al. Igf2bp1 is required for full induction of Ptgs2 mRNA in colonic mesenchymal stem cells in mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:110–121. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown SL, et al. Myd88-dependent positioning of Ptgs2-expressing stromal cells maintains colonic epithelial proliferation during injury. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:258–269. doi: 10.1172/JCI29159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Satpathy AT, et al. Re(de)fining the dendritic cell lineage. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:1145–1154. doi: 10.1038/ni.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Possot C, et al. Notch signaling is necessary for adult, but not fetal, development of RORgammat(+) innate lymphoid cells. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:949–958. doi: 10.1038/ni.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee JS, et al. AHR drives the development of gut ILC22 cells and postnatal lymphoid tissues via pathways dependent on and independent of Notch. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:144–151. doi: 10.1038/ni.2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ota N, et al. IL-22 bridges the lymphotoxin pathway with the maintenance of colonic lymphoid structures during infection with Citrobacter rodentium. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:941–948. doi: 10.1038/ni.2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Y, et al. Lymphotoxin beta receptor signaling in intestinal epithelial cells orchestrates innate immune responses against mucosal bacterial infection. Immunity. 2010;32:403–413. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim YG, et al. The Nod2 sensor promotes intestinal pathogen eradication via the chemokine CCL2-dependent recruitment of inflammatory monocytes. Immunity. 2011;34:769–780. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rivollier A, et al. Inflammation switches the differentiation program of Ly6Chi monocytes from antiinflammatory macrophages to inflammatory dendritic cells in the colon. J Exp Med. 2012;209:139–155. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Basu R, et al. Th22 cells are an important source of IL-22 for host protection against enteropathogenic bacteria. Immunity. 2012;37:1061–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Steinman RM. Decisions About Dendritic Cells: Past, Present, and Future. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;30:1–22. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-100311-102839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heng TS, Painter MW. The Immunological Genome Project: networks of gene expression in immune cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1091–1094. doi: 10.1038/ni1008-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Han H, et al. Inducible gene knockout of transcription factor recombination signal binding protein-J reveals its essential role in T versus B lineage decision. International Immunology. 2002;14:637–645. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]