Abstract

Structure determination of proteins and other macromolecules has historically required the growth of high-quality crystals sufficiently large to diffract x-rays efficiently while withstanding radiation damage. We applied serial femtosecond crystallography (SFX) using an x-ray free-electron laser (XFEL) to obtain high-resolution structural information from microcrystals (less than 1 micrometer by 1 micrometer by 3 micrometers) of the well-characterized model protein lysozyme. The agreement with synchrotron data demonstrates the immediate relevance of SFX for analyzing the structure of the large group of difficult-to-crystallize molecules.

Elucidating macromolecular structures by x-ray crystallography is an important step in the quest to understand the chemical mechanisms underlying biological function. Although facilitated greatly by synchrotron x-ray sources, the method is limited by crystal quality and radiation damage (1). Crystal size and radiation damage are inherently linked, because reducing radiation damage requires lowering the incident fluence. This in turn calls for large crystals that yield sufficient diffraction intensities while reducing the dose to individual molecules in the crystal. Unfortunately, growing well-ordered large crystals can be difficult in many cases, particularly for large macromolecular assemblies and membrane proteins. In contrast, micrometer-sized crystals are frequently observed. Although diffraction data of small crystals can be collected by using microfocus synchrotron beamlines, this remains a challenging approach because of the rapid damage suffered by these small crystals (1).

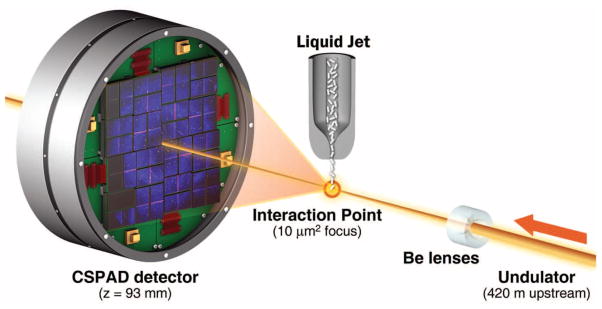

Serial femtosecond crystallography (SFX) using x-ray free-electron laser (XFEL) radiation is an emerging method for three-dimensional (3D) structure determination using crystals ranging from a few micrometers to a few hundred nanometers in size and potentially even smaller. This method relies on x-ray pulses that are sufficiently intense to produce high-quality diffraction while of short enough duration to terminate before the onset of substantial radiation damage (2–4). X-ray pulses of only 70-fs duration terminate before any chemical damage processes have time to occur, leaving primarily ionization and x-ray–induced thermal motion as the main sources of radiation damage (2–4). SFX therefore promises to break the correlation between sample size, damage, and resolution in structural biology. In SFX, a liquid microjet is used to introduce fully hydrated, randomly oriented crystals into the single-pulse XFEL beam (5–8), as illustrated in Fig. 1. A recent low-resolution proof-of-principle demonstration of SFX performed at the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) (9) using crystals of photosystem I ranging in size from 200 nm to 2 μm produced interpretable electron density maps (6). Other demonstration experiments using crystals grown in vivo (7), as well as in the lipidic sponge phase for membrane proteins (8), were recently published. However, in all these cases, the x-ray energy of 1.8 keV (6.9 Å) limited the resolution of the collected data to about 8 Å. Data collection to a resolution better than 2 Å became possible with the recent commissioning of the LCLS Coherent X-ray Imaging (CXI) instrument (10). The CXI instrument provides hard x-ray pulses suitable for high-resolution crystallography and is equipped with Cornell-SLAC Pixel Array Detectors (CSPADs), consisting of 64 tiles of 192 pixels by 185 pixels each, arranged as shown in Fig. 1 and figs. S1 and S2. The CSPAD supports the 120-Hz readout rate required to measure each x-ray pulse from LCLS (11, 12).

Fig. 1.

Experimental geometry for SFX at the CXI instrument. Single-pulse diffraction patterns from single crystals flowing in a liquid jet are recorded on a CSPAD at the 120-Hz repetition rate of LCLS. Each pulse was focused at the interaction point by using 9.4-keV x-rays. The sample-to-detector distance (z) was 93 mm.

Here, we describe SFX experiments performed at CXI analyzing the structure of hen egg-white lysozyme (HEWL) as a model system by using microcrystals of about 1 μm by 1 μm by 3 μm (4, 11). HEWL is an extremely well-characterized protein that crystallizes easily. It was the first enzyme to have its structure determined by x-ray diffraction (13) and has since been thoroughly characterized to very high resolution (14). Lysozyme has served as a model system for many investigations, including radiation damage studies. This makes it an ideal system for the development of the SFX technique. Microcrystals of HEWL in random orientation were exposed to single 9.4-keV (1.32 Å) x-ray pulses of 5- or 40-fs duration focused to 10 μm2 at the interaction point (Fig. 1). The average 40-fs pulse energy at the sample was 600 μJ per pulse, corresponding to an average dose of 33 MGy deposited in each crystal. This dose level represents the classical limit for damage using cryogenically cooled crystals (15). The average 5-fs pulse energy was 53 μJ. The SFX-derived data were compared to low-dose data sets collected at room temperature by using similarly prepared larger crystals (11). This benchmarks the technique with a well-characterized model system.

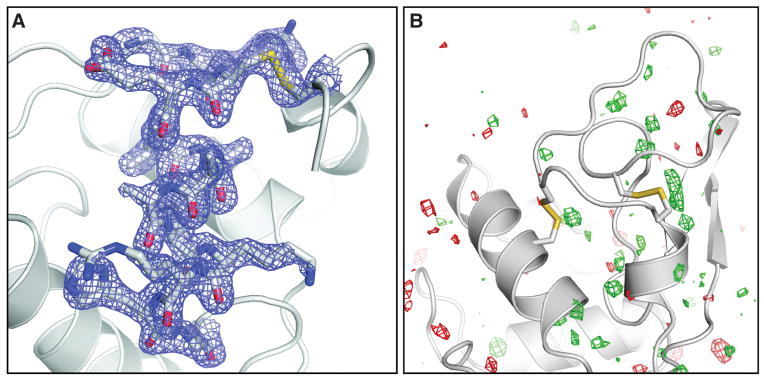

We collected about 1.5 million individual “snapshot” diffraction patterns for 40-fs duration pulses at the LCLS repetition rate of 120 Hz using the CSPAD. About 4.5% of the patterns were classified as crystal hits, 18.4% of which were indexed and integrated with the CrystFEL software (14) showing excellent statistics to 1.9 Å resolution (Table 1 and table S1). In addition, 2 million diffraction patterns were collected by using x-ray pulses of 5-fs duration, with a 2.0% hit rate and a 26.3% indexing rate, yielding 10,575 indexed patterns. The structure, partially shown in Fig. 2A, was determined by molecular replacement [using Protein Data Bank (PDB) entry 1VDS] and using the 40-fs SFX data. No significant differences were observed in an Fobs(40 fs) − Fobs (synchrotron) difference electron density map (Fig. 2B). The electron density map shows features that were not part of the model (different conformations of amino acids and water molecules) and shows no discernible signs of radiation damage. Also, when the data were phased with molecular replacement by using the turkey lysozyme structure as a search model (PDB code 1LJN), the differences between the two proteins were immediately obvious from the maps (fig. S3).

Table 1.

SFX and synchrotron data and refinement statistics. Highest resolution shells are 2.0 to 1.9 Å. Rsplit is as defined in (16): . SLS room temperature (RT) data 3 statistics are from XDS (20). B factors were calculated with TRUNCATE (21). R and rmsd values were calculated with PHENIX (22). n.a., not applicable. The diffraction patterns have been deposited with the Coherent X-ray Imaging Data Bank, cxidb.org (accession code ID-17).

| Parameter | 40-fs pulses | 5-fs pulses | SLS RT data 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelength | 1.32 Å | 1.32 Å | 0.9997 Å |

| X-ray focus (μm2) | ~10 | ~10 | ~100 × 100 |

| Pulse energy/fluence at sample | 600 μJ/4 × 1011 photons per pulse | 53 μJ/3.5 ×1010 photons per pulse | n.a./2.5 × 1010 photons/s |

| Dose (MGy) | 33.0 per crystal | 2.9 per crystal | 0.024 total |

| Dose rate (Gy/s) | 8.3 × 1020 | 5.8 × 1020 | 9.6 × 102 |

| Space group | P43212 | P43212 | P43212 |

| Unit cell length (Å), α = β = γ = 90° | a = b =79, c = 38 | a = b = 79, c = 38 | a = b = 79.2, c = 38.1 |

| Oscillation range/exposure time | Still exp./40 fs* | Still exp./5 fs* | 1.0°/0.25 s |

| No. collected diffraction images | 1,471,615 | 1,997,712 | 100 |

| No. of hits/indexed images | 66,442/12,247 | 40,115/10,575 | n.a./100 |

| Number of reflections | n.a. | n.a. | 70,960 |

| Number of unique reflections | 9921 | 9743 | 9297 |

| Resolution limits (Å) | 35.3–1.9 | 35.3–1.9 | 35.4–1.9 |

| Completeness | 98.3% (96.6%) | 98.2% (91.2%) | 92.6% (95.1%) |

| I/σ(I) | 7.4 (2.8) | 7.3 (3.1) | 18.24 (5.3) |

| Rsplit | 0.158 | 0.159 | n.a. |

| Rmerge | n.a. | n.a. | 0.075 (0.332) |

| Wilson B factor | 28.3 Å2 | 28.5 Å2 | 19.4 Å2 |

| R-factor/R-free | 0.196/0.229 | 0.189/0.227 | 0.166/0.200 |

| Rmsd bonds, Rmsd angles | 0.006 Å, 1.00° | 0.006 Å, 1.03° | 0.007 Å, 1.05° |

| PDB code | 4ET8 | 4ET9 | 4ETC |

Electron bunch length

Fig. 2.

(A) Final, refined 2mFobs − DFcalc (1.5σ) electron density map (17) of lysozyme at 1.9 Å resolution calculated from 40-fs pulse data. (B) Fobs(40 fs) − Fobs (synchrotron) difference Fourier map, contoured at +3 σ (green) and −3 σ (red). No interpretable features are apparent. The synchrotron data set was collected with a radiation dose of 24 kGy.

Even though the underlying radiation damage processes differ because of the different time scales of the experiments using an XFEL and a synchrotron or rotating anode (femtoseconds versus seconds or hours), no features related to radiation damage are observed in difference maps calculated between the SFX and the low-dose synchrotron data (Fig. 2B). In addition to local structural changes, metrics like I/I0 [the ratio of measured intensities (I) to the ideal calculated intensities (I0)] and the Wilson B factor are most often used to characterize global radiation damage in protein crystallography (17). I/I0 is not applicable to the SFX data. However, the Wilson B factors of both SFX data sets show values typical for room-temperature data sets and do not differ significantly from those obtained from synchrotron and rotating anode data sets collected with different doses, using similarly grown larger crystals kept at room temperature and fully immersed in solution (11) (Table 1 and table S1). The R factors calculated between all collected data sets do not show a dose-dependent increase (fig. S4). However, higher R factors are observed for the SFX data, indicating a systematic difference. This is not caused by nonconvergence of the Monte Carlo integration, because scaling the 40- and 5-fs data together does not affect the scaling behavior. Besides non-isomorphism or radiation damage, possible explanations for this difference could include suboptimal treatment of weak reflections, the difficulties associated with processing still diffraction images, and other SFX-specific steps in the method. SFX is an emerging technique, and data processing algorithms, detectors, and data collection methods are under continuous development.

A simple consideration shows the attainable velocities of atoms in the sample depend on the deposited x-ray energy versus the inertia of those atoms: , where m is the mass of a carbon atom, for example, T is temperature, and kB is Boltzmann’s constant. For an impulse absorption of energy at the doses of our LCLS measurements, we predict average velocities less than 10 Å/ps, which gives negligible displacement during the FEL pulses. On the time scale of femtoseconds, radiation damage is primarily caused by impulsive rearrangement of atoms and electron density rather than the relatively slow-processes of chemical bond breaking typical in conventional crystallography using much longer exposures at much lower dose rates (the dose rate in this experiment was about 0.75 MGy per femtosecond). Neither the SFX electron density maps nor the Wilson B factors suggest obvious signs of significant radiation damage. Very short pulses (5-fs electron bunch) are not expected to produce observable damage, according to simulations (3). Furthermore, it has been reported that the actual x-ray pulses are shorter than the electron bunches for XFELs, making the pulse duration possibly shorter than the relevant Auger decays (18). The agreement between the SFX results using 40-fs pulses and 5-fs pulses suggests similar damage characteristics for the two pulse durations on the basis of the available data. Our results demonstrate that under the exposure conditions used, SFX yields high-quality data suitable for structural determination. SFX reduces the requirements on crystal size and therefore the method is of immediate relevance for the large group of difficult-to-crystallize molecules, establishing SFX as a very valuable high-resolution complement to existing macromolecular crystallography techniques.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Portions of this research were carried out at the LCLS, a National User Facility operated by Stanford University on behalf of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Basic Energy Sciences (OBES) and at the Swiss Light Source, beamline X10SA, Paul Scherrer Institute, Villigen, Switzerland. The CXI instrument was funded by the LCLS Ultrafast Science Instruments (LUSI) project funded by DOE, OBES. We acknowledge support from the Max Planck Society, the Hamburg Ministry of Science and Research, and the Joachim Herz Stiftung, as part of the Hamburg Initiative for Excellence in Research (LEXI); the Hamburg School for Structure and Dynamics in Infection; the U.S. NSF (awards 0417142 and MCB-1021557); the NIH (award 1R01GM095583); the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (grants 01KX0806 and 01KX0807); the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Cluster of Excellence EXC 306; AMOS program within the Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences Division of the OBES, Office of Science, U.S. DOE; the Swedish Research Council; the Swedish Foundation for International Cooperation in Research and Higher Education. We thank A. Meinhart and E. Hofmann for collecting the synchrotron data set, M. Gebhart for help preparing the crystals, and M. Hayes and the technical staff of SLAC and the LCLS for their great support in carrying out these experiments. Special thanks to G. M. Stewart, T. Anderson, and SLAC Infomedia for generating Fig. 1. The structure factors and coordinates have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank (accession codes 4ET8, 4ET9, 4ETA, 4ETB, 4ETC, 4ETD, and 4ETE). The diffraction patterns have been deposited with the Coherent X-ray Imaging Data Bank cxidb.org (accession code ID-17). The Arizona Board of Regents, acting for and on behalf of Arizona State University and in conjunction with R.B.D., U.W., D.P.D., and J.C.H.S., has filed U.S. and international patent applications on the nozzle technology applied herein.

Footnotes

References and Notes

- 1.Holton JM, Frankel KA. Acta Crystallogr. 2010;D66:393. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neutze R, Wouts R, van der Spoel D, Weckert E, Hajdu J. Nature. 2000;406:752. doi: 10.1038/35021099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barty A, et al. Nat Photonics. 2011;6:35. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2011.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lomb L, et al. Phys Rev B. 2011;84:214111. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.84.214111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DePonte DP, et al. J Phys D. 2008;41:195505. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapman HN, et al. Nature. 2011;470:73. doi: 10.1038/nature09750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koopmann R, et al. Nat Methods. 2012;9:259. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johansson LC, et al. Nat Methods. 2012;9:263. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emma P, et al. Nat Photonics. 2010;4:641. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boutet S, Williams GJ. New J Phys. 2010;12:035024. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Materials and methods are available as supplementary materials on Science Online.

- 12.Philipp HT, Hromalik M, Tate M, Koerner L, Gruner SM. Nucl Instrum Methods A. 2011;649:67. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blake CCF, et al. Nature. 1965;206:757. doi: 10.1038/206757a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J, Dauter M, Alkire R, Joachimiak A, Dauter Z. Acta Crystallogr. 2007;D63:1254. doi: 10.1107/S0907444907054224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Owen RL, Rudiño-Piñera E, Garman EF. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600973103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White TA, et al. J Appl Cryst. 2012;45:335. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Southworth-Davies RJ, Medina MA, Carmichael I, Garman EF. Structure. 2007;15:1531. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young L, et al. Nature. 2010;466:56. doi: 10.1038/nature09177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Read RJ. Acta Crystallogr. 1986;A42:140. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kabsch W. J Appl Cryst. 1993;26:795. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Acta Crystallogr. 2005;D61:458. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905001617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams PD, et al. Acta Crystallogr. 2010;D66:213. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.