Abstract

Alkylating agents introduce cytotoxic and/or mutagenic lesions to DNA bases leading to induction of adaptive (Ada) response, a mechanism protecting cells against deleterious effects of environmental chemicals. In Escherichia coli, the Ada response involves expression of four genes: ada, alkA, alkB, and aidB. In Pseudomonas putida, the organization of Ada regulon is different, raising questions regarding regulation of Ada gene expression. The aim of the presented studies was to analyze the role of AlkA glycosylase and AlkB dioxygenase in protecting P. putida cells against damage to DNA caused by alkylating agents. The results of bioinformatic analysis, of survival and mutagenesis of methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) or N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG) treated P. putida mutants in ada, alkA and alkB genes as well as assay of promoter activity revealed diverse roles of Ada, AlkA and AlkB proteins in protecting cellular DNA against alkylating agents. We found AlkA protein crucial to abolish the cytotoxic but not the mutagenic effects of alkylans since: (i) the mutation in the alkA gene was the most deleterious for MMS/MNNG treated P. putida cells, (ii) the activity of the alkA promoter was Ada-dependent and the highest among the tested genes. P. putida AlkB (PpAlkB), characterized by optimal conditions for in vitro repair of specific substrates, complementation assay, and M13/MS2 survival test, allowed to establish conservation of enzymatic function of P. putida and E. coli AlkB protein. We found that the organization of P. putida Ada regulon differs from that of E. coli. AlkA protein induced within the Ada response is crucial for protecting P. putida against cytotoxicity, whereas Ada prevents the mutagenic action of alkylating agents. In contrast to E. coli AlkB (EcAlkB), PpAlkB remains beyond the Ada regulon and is expressed constitutively. It probably creates a backup system that protects P. putida strains defective in other DNA repair systems against alkylating agents of exo- and endogenous origin.

Introduction

Alkylating agents of endogenous (by-products of cellular metabolism) and exogenous (environmental chemicals) origin introduce a variety of damages to DNA. The major products of alkylation include N 7-methylguanine (7meG), N 3-methyladenine (3meA) and O 6-methylguanine (O 6meG) with smaller amounts of N 1-methyladenine (1meA), N 3-methylcytosine (3meC), O 4-methylthymine (O 4meT), and methylphosphotriesters (MPTs). SN2 type alkylating agents, such as methyl methanesulfonate (MMS), predominantly produce N-methylation, whereas the SN1 type, such as N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG), create both N- and O-methylation [1]. Methylated bases can be toxic to the cell by blocking replication (e.g. 3meA, 1meA, 3meC, 3meG), can induce mutations (e.g. O 6meG, 3meC, 3meA, 1meA) or are innocuous (e.g. 7meG). Additionally, the purines methylated at N3 or N7 position can be easily hydrolyzed creating abasic (AP) sites that, if not repaired, are toxic or mutagenic to the cell [2-4].

Organisms are well equipped with mechanisms protecting cells against harmful effects of lesions introduced by alkylating agents. In E. coli, these defense systems involve the tag and ogt genes, expressed constitutively, and ada, alkA, alkB, and aidB, expressed after induction of the adaptive response (Ada response) [5-7]. A crucial role in this process is played by ada-encoded Ada methyltransferase, functioning as a transcriptional activator inducing expression of the ada-alkB operon and the alkA and aidB genes. Ada protein is composed of two major domains: the 19 kDa C-terminal AdaA domain (C-Ada19), directly demethylating O 6meG and O 4meT and transferring the methyl groups onto its own cysteine 321 (Cys-321) [8], and the 20 kDa N-terminal AdaB domain, demethylating Sp-diastereoisomers of MPTs in DNA by transferring the methyl groups onto its cysteine 38 (Cys-38). Self-methylation at Cys-38 results in transcriptional activation of Ada protein and in an increase in specific DNA binding affinity to genes containing the sequence of ada operator in their promoters. High concentration of unmethylated Ada protein (>200 molecules per cell) inhibits transcriptional activation [9], whereas MPTs act as molecular sensors for changing the levels of DNA alkylation in bacteria [5]. Induced within the Ada response AlkA and expressed constitutively Tag proteins are, respectively, 3meA DNA glycosylase II and I. By removing 3meA, these glycosylases create AP sites in DNA, subsequently repaired by excision of the damaged fragment, re-synthesis and ligation of the DNA breaks. The specificity of AlkA is much broader than that of Tag. Besides 3meA, AlkA also removes 7-methyladenine (7meA), 3-methylguanine (3meG), 7meG, products of nitrosation, e.g. xanthine and oxanine [10], and some other types of alkylated bases [11]. It has also been found that AlkA (but not Tag) can remove normal bases (mainly G) from DNA [12]. Recently, it has been proven that AlkAs from Archaeoglobus fulgidus [13] and Deinococcus radiodurans [14] additionally show activity towards the main substrates of AlkB dioxygenase, 3meC and 1meA.

AlkB dioxygenase directly regenerates unmodified bases from the N1 position of adenine and N3 of cytosine [15,16]. Using non-heme Fe(II) and co-substrates, 2-oxoglutarate (2OG) and oxygen (O2), it initiates oxidative demethylation of DNA/RNA bases [17]. E. coli AlkB (EcAlkB) in the presence of O2 converts 2OG to succinate and CO2. The initial hydroxylation of the methyl group results in cleavage of the C-N bond restoring unmodified A and C bases both, in DNA and RNA. N1 of A and N3 of C are much more susceptible to methylation in single-stranded (ss) than in double-stranded (ds) DNA and, consequently, AlkB repairs lesions in ssDNA more efficiently than in dsDNA [18]. Similarly, AlkB oxidizes ethyl, propyl, hydroxyethyl and hydroxypropyl modifications. Recently, it has been found that it repairs also exocyclic adducts that may arise as a consequence of endocellular oxidative stress or environmental pollution – ethano- (3,N 4-α-hydroxyethanocytosine, HEC), etheno- (1,N 6-ethenoadenine, εA and 3,N 4-ethenocytosine, εC) and hydroxypropano- (3,N 4-α-hydroxypropanocytosine, HPC) groups added to DNA bases [19-22]. 3-methylthymine (3meT) and 1-methylguanine (1meG) are also repaired by AlkB but much less efficiently than 1meA or 3meC [20,21].

Our bioinformatic analysis has shown the presence of E. coli AlkB homologs in almost all organisms [23]. Higher eukaryotes possess several dioxygenases (e.g. nine in human [24,25], 13 in Arabidopsis thaliana [23]) of different cell localization, biological functions and substrate specificity.

The role of AidB, the fourth member of the Ada response, remains unclear. The protein preferentially binds AT-rich transcription enhancer sequences (UP elements), found upstream of many highly expressed genes, and seems to protect DNA from damage by alkylating agents [26].

The Ada response is conserved among many bacterial species although domains of Ada and AlkA proteins occur in diverse combinations in different prokaryotes. In the present study we investigated the organization of Ada response in Pseudomonas putida. The genus Pseudomonas constitutes a large diverse group of mostly saprophytic bacteria inhabiting soil, water, plants and animals, and playing an important role in community of soil microorganisms. These bacteria are able to metabolize toxic organic materials and are tolerant to antibiotics, organic solvents and heavy metals [27-29].

Here, we report in silico, in vitro and in vivo studies on the role of P. putida AlkA and AlkB proteins in protecting cellular DNA against alkylation lesions. In P. putida cells AlkA peremptorily plays a crucial role in repairing MMS and MNNG induced lesions in DNA, as evidenced by: (i) lack of AlkA glycosylase resulting in strong cytotoxic effect in MMS/MNNG-treated P. putida alkA mutant; (ii) wider than for E. coli AlkA substrate specificity probably including typical AlkB substrates, 1meA and 3meC (iii) the highest among P. putida Ada genes activity of alkA promoter in the presence of Ada protein. We have found P. putida and E. coli AlkB proteins to be similar in substrate specificity but differently regulated. The results of promoter activity allow to predict constitutive expression of PpalkB, suggesting its supportive role in protecting cells against exo- and endogenous alkylating agents.

Results

The genomes of P. putida species code more putative proteins dealing with alkyl-DNA damages than E. coli

In E. coli, the adaptive response results in increased expression of four genes, ada, alkB, alkA and aidB [5,6]. In order to establish whether a similar response occurs in pseudomonads, we searched for the presence of E. coli Ada regulon orthologs in P. putida genome and examined the ability of alkylating agents to induce transcription of these genes. The orthologs for E. coli Ada regulon genes are present in the genome of P. putida KT2440 (genome analysis, NCBI database). However, the organization of alkA (PP_0705), ada (PP_0706) and alkB (PP_3400) orthologs in P. putida differs from that of E. coli. In E. coli, the ada and alkB genes comprise one operon, separated by 160 kbp from alkA, whereas in P. putida, the alkA and ada genes are located together (and are most probably transcribed in the direction alkA-ada), and the alkB gene is located about 3 Mbp apart (Figure 1A and B).

Figure 1. The genes encoding proteins involved in the repair of alkylation damage to DNA in (A) P. putida (tag1 – locus tag: PputGB1_0078, alkA – PputGB1_0739, ada – PputGB1_0740, tag2 – PputGB1_1244, alkA2 – PputGB1_2545, alkB – PputGB1_2549, ogt – PputGB1_2805, gcdH – PputGB1_3505, atl – PputGB1_4493, aidB – PputGB1_4834, aag – PputGB1_4865, adap – promoter region containing putative Ada box, hp – hypothetical protein) and (B) E. coli species (atl – ECDH10B_0410, ogt – ECDH10B_1455, alkA – ECDH10B_2218, alkB – ECDH10B_2369, ada – ECDH10B_2370, tag – ECDH10B_3728, aidB – ECDH10B_4382).

The CLANS protein clustering of P. putida and E. coli AlkA, Tag, and Aag sequences (C) indicates that PpAlkA2s are 3meA glycosylases most closely related to EcAlkA proteins. The CLANS clustering of P. putida and E. coli AidB protein sequences (family cd01154, NCBI) (D) clearly shows that the P. putida acyl-CoA dehydrogenases represented by P. putida KT2440 locus PP_4780 are most closely related to E. coli AidB proteins but the subfamily of PpGcdH, comprising other acyl-CoA dehydrogenases represented by P. putida KT2440 locus PP_0158, preserve perfect Ada boxes in their promoter regions (see Figure 3).

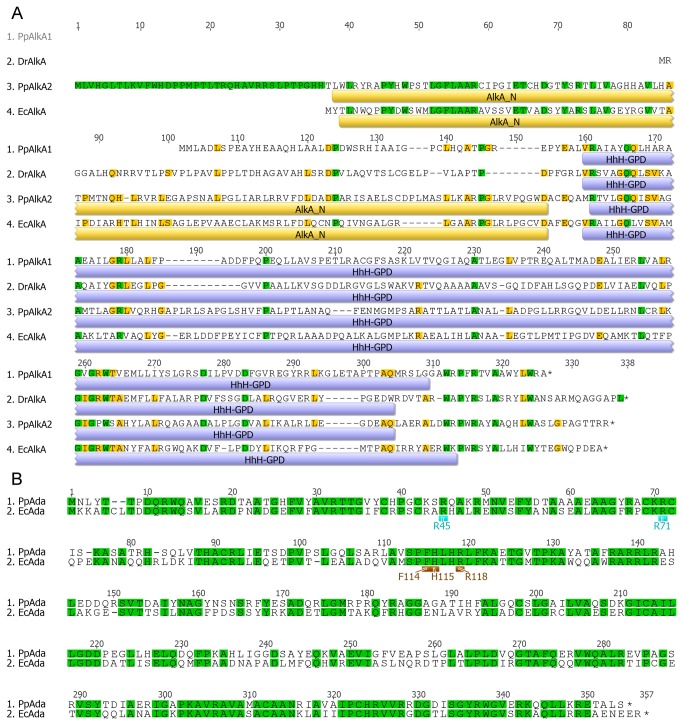

The predicted amino acid sequences of P. putida KT2440 and E. coli K12 DH10B Ada proteins exhibited 54.6% of identity (Figure 2B) and those of AlkB 56% identity. PpAda sequence contains all of the amino acids homologous to the EcAda residues responsible for the sequence-specific DNA binding to the E. coli ada regulon promoters, R45 and R71, for the binding to the conserved A box (AAT), and F114, H115 and R118, for the specific interactions with the B box (GCAA) of these promoters [30]. This indicated that the mechanisms of transcriptional activation by Ada proteins are conserved between E. coli and P. putida.

Figure 2. The multiple protein alignment of E. coli K-12 DH10B EcAlkA (locus tag: ECDH10B_2218), P. putida KT2440 PpAlkA (PP_0705), P. putida GB-1 PpAlkA2 (PputGB1_2545), and D. radiodurans DrAlkA (DR_2584) generated with ClustalW (A).

Yellow and blue bars represent Pfam domains corresponding to the above sequence: AlkA_N – the N-terminal domain of 3meA glycosylase AlkA proteins; HhH-GPD – helix-hairpin-helix domain with Gly/Pro rich loop followed by a conserved aspartate residue. The multiple protein alignment of P. putida KT2440 PpAda (PP_0706) and E. coli K-12 DH10B EcAda (ECDH10B_2370) proteins (B) shows the perfect conservation of residues responsible for the specific interaction with the conserved nucleotide sequences of the ada regulon promoters: R45 and R71 (light blue) binding to the A box and F114, H115, and R118 (brown) binding to the B box.

PpAlkB protein contains all of the amino acid residues required for including this protein into the dioxygenase superfamily. Our latest clustering image allowed to place PpAlkB into the first subgroup, together with EcAlkB and other proteobacterial AlkBs [23].

Unlike Ada and AlkB proteins, EcAlkA and PpAlkA sequences are largely different. The predicted amino acid sequence identity between these proteins equals only 17.2% (Figure 2A). Furthermore, PpAlkA is shorter by 61 amino acid residues at its N-terminus. Consequently, it lacks the N-terminal α/β domain present in EcAlkA. Nevertheless, the PpAlkA protein still consists of the C-terminal glycosylase domain and the vital catalytic aspartate residue. Moreover, it resembles Deinococcus radiodurans AlkA (DrAlkA) with 33.5% identity [14], which could determine the different mechanism of action and/or substrate specificity of this protein in comparison to EcAlkA. Interestingly, several other analyzed P. putida genomes (e.g., P. putida strains GB-1, S16, HB326, and NBRC14164) contain additional alkA, named here alkA2 (Figure 1A and B). The PpAlkA2 proteins are full-length putative 3meA glycosylases composed of two AlkA domains and are mostly similar to EcAlkA (Figure 1C) exhibiting about 34% of identity (Figure 2A).

The AidB family (cd00540) contains the mean number of 15 and 4 AidB proteins for P. putida and E. coli species, respectively. Since the acyl-CoA dehydrogenases are highly similar, it is difficult to precisely identify putative functional P. putida AidB gene. The protein clustering of P. putida and E. coli acyl-CoA dehydrogenases shows that the proteins represented by P. putida KT2440 PP_4780 locus belong to the subfamily of functional E. coli AidB proteins (Figure 1D), but, as shown below, the promoter regions of these genes do not contain putative Ada boxes. Instead, other proteins of P. putida acyl-CoA dehydrogenases subfamily represented by P. putida KT2440 PP_0158 locus (Figure 1D) are coded by genes with perfectly preserved Ada box sequences in their promoter regions (Figure 3B). Moreover, this locus was obtained as a result of genomic context search in MicrobesOnline database using E. coli aidB as a query. These proteins are annotated as glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenases and named here GcdH. Since the precise function of AidB is unknown, we focused our functional studies only on alkA, ada, and alkB orthologs.

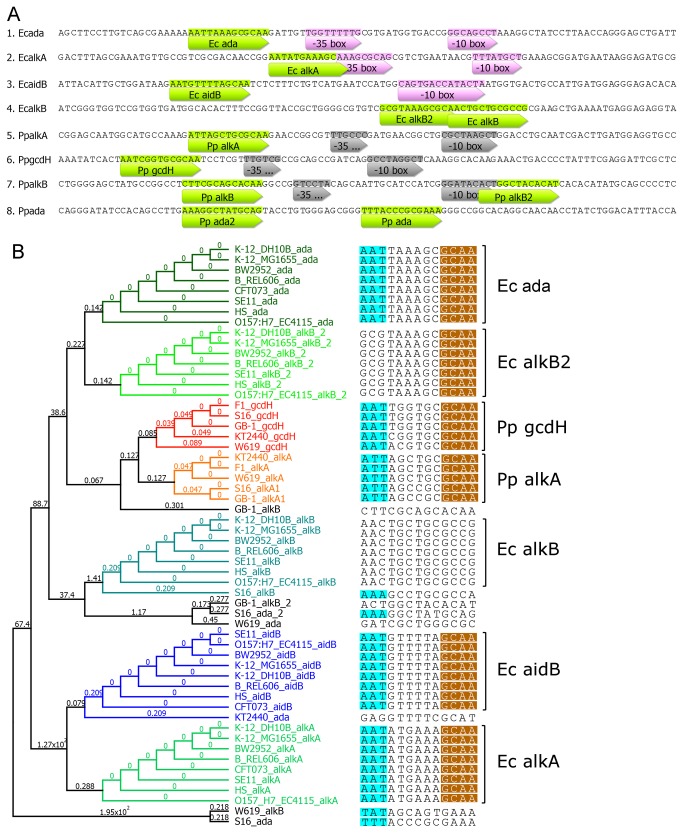

Figure 3. The consensus sequences responsible for Ada protein specific interaction (A) located in promoter sequences (up to -100 nucleotide residues relative to ATG start codons) of E. coli ada, alkA, and aidB.

Additionally, the predicted consensuses in promoter regions of E. coli alkB and P. putida alkA, gcdH, alkB, and ada genes are shown (green bars). Also, the putative -35 and -10 boxes responsible for RNA polymerase interaction are marked in pink (retrieved from RegulonDB, http://regulondb.ccg.unam.mx) or grey (SoftBerry BPROM prediction tool, http://linux1.softberry.com). The phylogenetic tree (B) shows relative conservation between depicted consensus sequences based on UPGMA Geneious Tree Builder, A box – light blue, B box – brown, numbers indicate substitutions per site (for details see Materials and Methods).

In addition to the potential ada regulon genes, all of the analyzed P. putida genomes show the presence of the second tag gene, named here as tag2. The protein clustering of putative repair glycosylases coping with alkyl-DNA damages shows that the additional copies of 3meA glycosylases of P. putida species – Tag2 and AlkA2 are mostly related to EcTag and EcAlkA proteins, respectively (Figure 1C). The above list of P. putida genes can be widened by aag -3-alkylated purines and hypoxanthine DNA glycosylase (Figure 1A). Notably, both P. putida and E. coli genomes encode for Atl proteins, which have recently been identified as alkyltransferase-like proteins taking part in the repair of O 6-alkyl-guanines [31].

P. putida alkA and gcdH Gene Promoters Contain Canonical Ada Boxes

Particular nucleotide sequences in E. coli ada, alkA and aidB promoter regions responsible for specific interaction with Ada transcriptional activator were identified at the structural level [30]. To identify putative Ada boxes in the P. putida Ada regulon genes, motif searching and database scanning were performed (MEME Server, see Materials and Methods). The most conserved consensus sequences in P. putida were identified in the gcdH and alkA promoter regions. Both sequences contain canonical A and B boxes, AAT/ATT and GCAA, respectively, located at a similar distance from the -35/-10 RNA polymerase consensus, as in E. coli ada promoter region (Figure 3A). As expected, E. coli alkB promoter does not contain a fully preserved Ada box although the FIMO search identified two fragments with quite high similarity to E. coli and P. putida Ada box motifs. The same concerns P. putida putative alkB and ada promoter regions. Thus, degraded Ada box consensus can be speculated in PpalkB promoter since it consists of putative -35/-10 RNA polymerase interaction sites. Actually, the P. putida S16 and W619 A boxes contain the demanded A/T base pairs. On the other hand, the B boxes show single nucleotide polymorphism with the GCCA and GAAA sequences in above mentioned strains, respectively (Figure 3B). Additionally, the alkA2 genes of P. putida GB-1 and S16 strains do not show the Ada box motifs below the P-value of 0.01. The promoter regions of all 15 putative P. putida KT2440 acyl-CoA dehydrogenases were also tested for the presence of Ada box motifs with negative results (data not shown) except for the above mentioned gcdH.

P. putida alkA promoter activity is higher than that of alkB and ada promoters

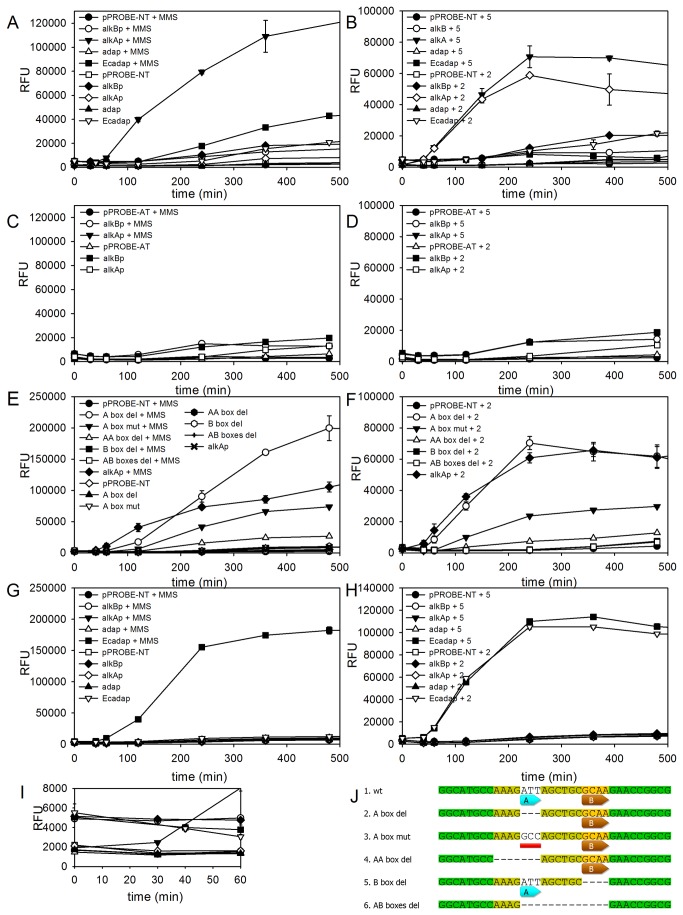

In order to examine whether in P. putida the transcription of the alkB gene and the putative alkA-ada operon is inducible by alkyl damage to DNA, the promoter activities of these genes were monitored with the use of a GFP reporter (expressed from the pPROBE-NT vector, see Materials and Methods). The fluorescence levels detected in P. putida plasmid-free cells or in cells carrying the pPROBE-NT empty vector expressed at the values of about 1-2 × 103 RFU independently of MMS treatment (Figure 4). Similar basal level of fluorescence was detected in cells carrying the gfp transcriptional fusion with 100-bp DNA region derived upstream from the coding sequence of the ada gene, thereby implying that this DNA region does not contain any promoter for ada gene transcription. The transcriptional fusion with the DNA sequences located upstream of the alkA gene exhibited an increased level of fluorescence in the presence of MMS and MNNG. In MMS- or MNNG-treated cells carrying this construct, the level of fluorescence increased rapidly reaching 110 × 103 or 70 × 103 RFU, respectively, after 6 h of induction (Figure 4A and B). In non-treated control, the level of fluorescence did not exceed 8-10 × 103 RFU staying almost uninduced in the course of the experiment. These results indicated the inducibility of a promoter located upstream of the alkA gene by DNA methylating agents. In order to find whether this activation is Ada-dependent, the expression of the PpalkA promoter was measured in MMS/MNNG treated P. putida ada‾ strain. In ada‾ background, no significant induction of PpalkA promoter was observed (Figure 4C and D).

Figure 4. Promoter induction based on fluorescence intensities of GFP protein for the P. putida wt (A, B), P. putida .

ada‾ (C, D) or E. coli AB1157 (G, H) strains treated with 20 mM MMS (A, C, G) or 2 or 5 µg/ml MNNG (B, D, H), also the graph for (A) showing the basal induction is included (I). The promoter activity for deletion or mutation derivatives of P. putida alkA promoter in the presence 20 mM MMS (E) or 2 µg/ml MNNG (F), with sequences changed as shown (J).

On the other hand, at the start of the experiment, cells harboring the putative PpalkB promoter fusion with the gfp reporter gene exhibited RFU level of about 5 × 103, which is 2.6-fold higher than that in cells bearing other constructs. After 6 h, the level of RFU increased up to 20 × 103 RFU regardless of MMS/MNNG treatment (Figure 4A, B, and I) reaching about 5.7-fold higher induction in comparison to cells with pPROBE-NT alone. Thus, in P. putida, the alkB promoter does not respond to DNA alkyl damage. P. putida cells carrying the pPROBE-NT vector lacking PpalkB nucleotides -68 to -18 showed only a basal level of RFU (data not shown), probably because of the removal of the putative -35/-10 RNA polymerase boxes (Figure 3A). These results indicate that the DNA region lying between the indicated nucleotide positions comprises sequences of the PpalkB promoter. Taken together, our results indicate that transcription regulation of Ada regulon in P. putida differs from the E. coli orthologs; only the expression of the alkA-ada operon is inducible by methylating agents and requires Ada for transcriptional activation, whereas the alkB gene is expressed constitutively.

To investigate the importance of putative A and B boxes in the PpalkA promoter, particular deletion mutations were constructed (Figure 4J). Deletion of the B box as well as the entire fragment ranging from A to B box (13 nucleotides) in the PpalkA promoter region completely diminished its inducible property regardless of MMS or MNNG treatment (Figure 4E and F). Quite opposite effect applies to the A box where the removal of ATT bases led to even stronger induction: after MMS treatment and 8 h of incubation it reached about 200 × 103 RFU (Figure 4E). Nevertheless, the induction of transcription from this deletion mutant was delayed in comparison to the wild-type promoter. At the same time, the induction profile of this mutant promoter did not differ from that of the wild-type promoter in MNNG-treated cells (Figure 4F). Surprisingly, changing the ATT to GCC in the A box did not abolish the induction which reached about half of the value obtained for the wild-type alkA promoter (Figure 4E and F). Moreover, the complete lack of inducibility can be achieved by the deletion of additional AAAG bases upstream of the A box.

The E. coli ada promoter showed very strong induction in E. coli cells reaching about 180 and 110 × 103 RFU after MMS or MNNG treatment, respectively. On the other hand, we have found that the P. putida alkA promoter cannot be induced in MMS- or MNNG-treated E. coli cells (Figure 4G and H). These results indicated that either the EcAda protein is not able to induce transcription from the P. putida alkA promoter or the activation of transcription from this promoter requires additional factors that are absent in E. coli. At the same time, the E. coli ada promoter was inducible in P. putida MMS-treated cells. However, the maximum level of induction of this promoter in P. putida was about 3-fold lower (40 × 103 RFU) in comparison to that in E. coli cells (compare Figure 4A and G).

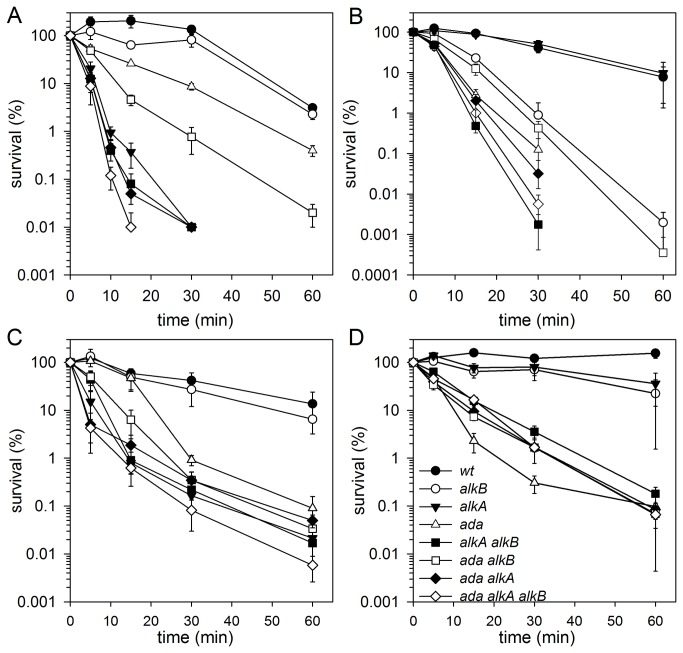

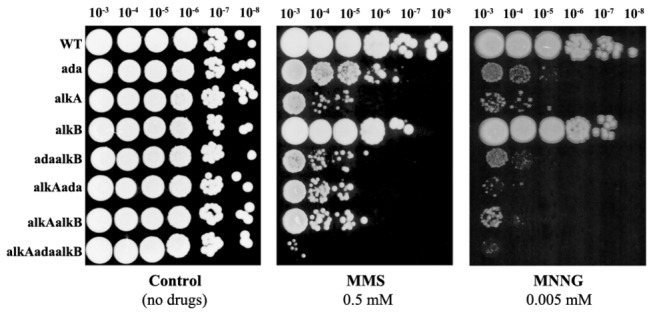

AlkA protein allows P. putida survival in the presence of alkylating agents

In order to recognize the impact of AlkA, AlkB and Ada on protection of P. putida cells against alkylating agents, P. putida wild-type strain and its derivatives lacking alkA, alkB or ada genes separately (single mutants) or in combinations (double and triple mutants) were compared for survival after MMS or MNNG treatment. Since MMS methylates mainly N atoms and MNNG N and O atoms in DNA bases [1], we could expect differences in sensitivity of P. putida mutants to these alkylating agents. At first, we performed a drop test with serial dilutions (10-3 to 10-8) of bacterial cultures spotted on agar plates containing (or not, for the control) 0.5 mM MMS or 0.74 µg/ml MNNG. These concentrations of MMS and MNNG did not affect significantly the survival of the wild-type P. putida and its AlkB-deficient derivative (Figure 5). The absence of AlkA strongly affected survival of bacteria on MMS and MNNG plates; moreover, the alkA - bacteria were more sensitive to MNNG than to MMS. The Ada-deficient P. putida was only slightly more sensitive to MMS than the wild-type, but there was a dramatic reduction in the survival of bacteria on MNNG plates. Requirement for AlkB became evident only in P. putida alkA‾ and ada‾alkA‾ mutants. This meant that the survival of the ada‾alkB‾ double mutant was reduced in comparison to the ada‾ single mutant, and the survival of the ada‾alkA‾alkB‾ triple mutant was reduced in comparison to the ada‾alkA‾ double mutant.

Figure 5. Sensitivity of P. putida AlkA-, AlkB-, and Ada-deficient mutants to alkylating chemicals MMS and MNNG.

The serial dilution drop test of P. putida mutants: 1 – wild-type, 2 – alkB‾, 3 – alkA‾, 4 – ada‾, 5 – alkB‾ada‾, 6 – alkA‾ada‾, 7 – alkA‾alkB‾, 8 – alkA‾alkB‾ada‾ on the medium containing the indicated concentrations of MMS (A) or MNNG (B). The vertical arrow shows the direction of dilution: from 10-1 to 10-8.

To monitor more precisely the dynamics of the survival of P. putida wild-type strain and its Ada-, AlkA-, and AlkB-deficient derivatives, the bacteria in liquid cultures were treated with MMS or MNNG and samples were taken at different time points to monitor cell survival. In this assay, P. putida alkB‾ mutant survived MMS treatment similarly as the wild-type strain, and mutation in the ada gene decreased cell survival only slightly (Figure 6A), thereby confirming the results of the drop test. Importantly, the lack of AlkA protein was extremely harmful: after 5 min of treatment with 20 mM MMS the survival of P. putida alkA‾ mutant decreased already to 10%, and after 10 min of treatment to less than 1%. Similar survival dynamics appeared in the case of the ada‾alkA‾ double mutant. The ada‾alkA‾alkB‾ triple mutant was the most sensitive to MMS: after 15 min of MMS treatment only 0.01% cells survived (Figure 6A). The absence of AlkA showed the strongest effect on the survival of MNNG-treated P. putida, whereas the absence of AlkB increased the sensitivity of P. putida cells to MNNG only in the absence of AlkA or Ada (Figure 6C), which confirms the results of the drop test (Figure 5). Thus, taken together, the results of the MMS and MNNG sensitivity studies suggested that among the three studied DNA alkyl repair enzymes, the AlkA is the major player in protecting P. putida against alkyl damage. The presence of AlkB is required only in the absence of other repair mechanisms.

Figure 6. Survival of P. putida (A, C) and E. coli (B, D) mutants defective in alkA, alkB, and ada genes treated with 20 mM MMS (A, B) or 5 µg/ml MNNG (C, D) for the indicated time.

Entirely different results of sensitivity to MMS and MNNG were obtained with E. coli strains. E. coli alkA‾ mutant, like the wild-type strain, was not sensitive to 15 min treatment with 20 mM MMS (Figure 6B), but the survival of the alkB‾ and ada‾ mutants decreased to 23 and 3%, respectively. Survival of double ada‾alkA‾ mutant decreased to the level of 2% under such conditions (Figure 6B).

Ada protein is crucial for MMS/MNNG-induced mutagenesis in P. putida and E. coli

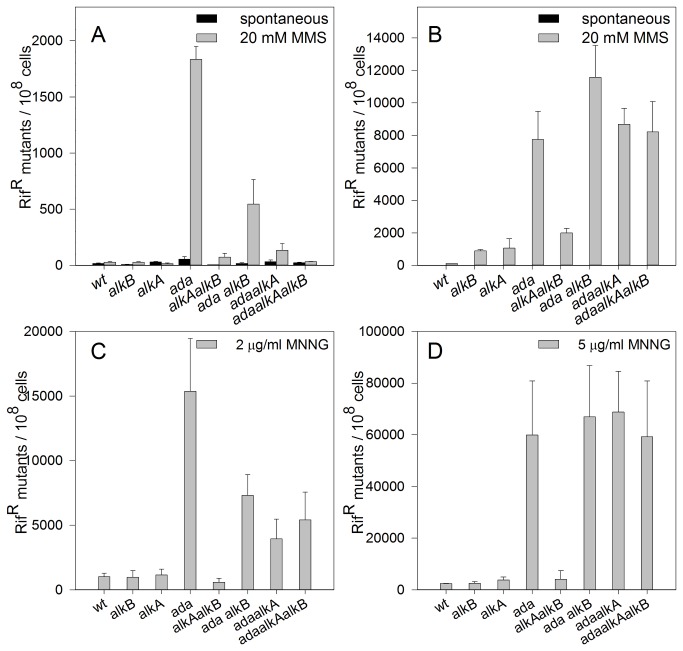

The results of survival assay after MMS/MNNG treatment indicated DNA repair proteins essential for protection of bacteria against cytotoxic action of alkylating agents. For P. putida, we have found AlkA protein to be crucial in this respect. On the other hand, the results of mutagenesis assay clearly indicate the key role of Ada protein in protecting P. putida cells against the mutagenic action of alkylating agents. P. putida strains defective in the ada gene showed the highest, among other mutants, level of MMS- and MNNG-induced RifR mutations, namely, about 1800 and 15,000 RifR/108 cells, respectively (Figure 7A and C). These results indicate that MMS/MNNG-induced O 6meG, if not directly demethylated by Ada methyltransferase, is a powerful source of mutations.

Figure 7. Frequency of MMS (A, B) or MNNG (C, D)-induced RifR mutations in P. putida (A, C) and E. coli (B, D) strains.

In P. putida ada‾ strains additionally mutated in alkA and/or alkB genes, the frequency of MNNG-induced RifR mutations was 2-3-fold lower than in the single ada‾ mutant (Figure 7C). In the case of P. putida alkA‾ mutant, the cytotoxic effect of MMS was so strong that the level of RifR mutations was not measurable under standard conditions. This observation concerns all the alkA mutants tested, namely, double ada‾alkA‾ and alkA‾alkB‾ and triple ada‾alkA‾alkB‾. Considering the strong cytotoxic effect of MMS on these mutants, we decided to shorten the time of MMS treatment to that resulting in about 30% of survival for each tested strain (note that in Figure 7A the frequency of mutations for alkA - strains represents the shorter time of MMS treatment). However, this approach did not influence the level of MMS-induced mutagenesis, indicating the key role of AlkA protein in protection of P. putida cells against cytotoxic but not mutagenic action of alkylating agents.

In E. coli, as in P. putida, the Ada protein was responsible for MNNG/MMS-induced mutagenesis. Thus, MNNG-treated bacteria mutated in the ada gene showed about 60,000 RifR/108 cells in comparison to 3000, 2000, and 4000 Rif R/108 cells in alkA‾, alkB‾, and alkA‾alkB‾ strains, respectively (Figure 7C and D). The frequency of MMS-induced RifR mutations in E. coli ada‾ strain was also the highest among single mutants (about 8000 versus 100 and 1000 Rif R/108 cells in alkA‾ and alkB‾ strains, respectively). However, in ada‾alkA‾, ada‾alkB‾, and ada‾alkA‾alkB‾ it remains on the high level of about 8700, 11,600 and 8200 Rif R/108 cells, respectively (Figure 7D). These results are dramatically different from those for the P. putida counterparts, e.g. in E. coli alkB‾ and alkA‾alkB‾ strains the frequencies of RifR mutations were, respectively, 30- and 36-fold higher in comparison to analogous P. putida mutants (Figure 7A and B). This indicates that, although EcAlkB and PpAlkB belong to the same subgroup of dioxygenases [23], their roles in the protection of E. coli and P. putida against alkylating agents are different. Similarly as in P. putida alkA‾, in E. coli alkA‾ strain, we observed an extremely low level of MMS-induced RifR mutations (about 55 Rif R/108 cells). However, in the presence of MMS, in contrast to P. putida, the E. coli alkA‾ mutant exhibited the same survival kinetics as the wild-type strain (Figure 6B).

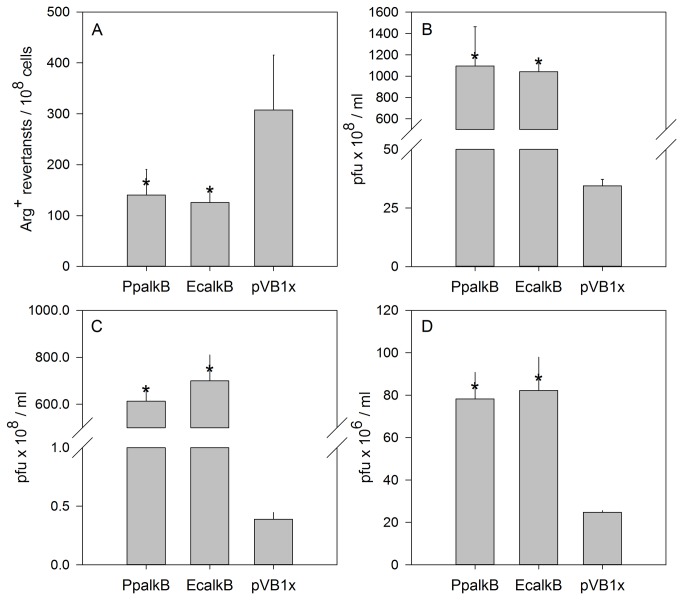

It has been demonstrated that EcAlkB preferentially binds to single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) and repairs lesions produced in it [18]. AlkB dioxygenase also repairs methylation damage in RNA [32,33]. Therefore, PpAlkB ability to repair alkylation lesions in ssDNA and ssRNA was tested with the use of phage survival assays involving, respectively, M13 and MS2 phages. Two alkylating agents, the methylating MMS inducing 1meA and 3meC lesions (Figure 8B and D) and ethylating chloroacetaldehyde (CAA) inducing etheno adducts (Figure 8C) were tested. In E. coli alkB‾ strain, MMS-treated M13 phage survived at a level of about 3 × 109 PFU/ml which is 30-fold lower than in E. coli alkB‾ but harboring the pVB1x plasmid expressing the EcalkB gene (Figure 8B).

Figure 8. Complementation assay for EcAlkB protein.

Frequency of MMS-induced Arg+ revertants in the E. coli alkB‾ strains harboring pVB1x plasmids expressing EcAlkB or the PpAlkB homolog (‘“empty”’ vector served as control) (A). Survival of MMS (B, D) or CAA (C) treated M13 (B, C) or MS2 (D) phages in the same strains.

CAA-treated M13 phage survived almost 20,000-fold better in E. coli alkB‾ harboring pVB1x EcalkB or pVB1x PpalkB than in the strain bearing an “empty” pVB1x plasmid (about 7.2 × 108 and 6.4 × 108 versus. 3.7 × 104 PFU/ml) (Figure 8C). However, the survival of MMS-treated RNA phage MS2 was only 4-fold elevated in E. coli alkB‾ expressing EcalkB or pVB1x PpalkB compared to cells bearing an empty plasmid (about 20 versus 80 × 106 PFU/ml). These results indicate similar substrate specificity of EcAlkB and PpAlkB proteins.

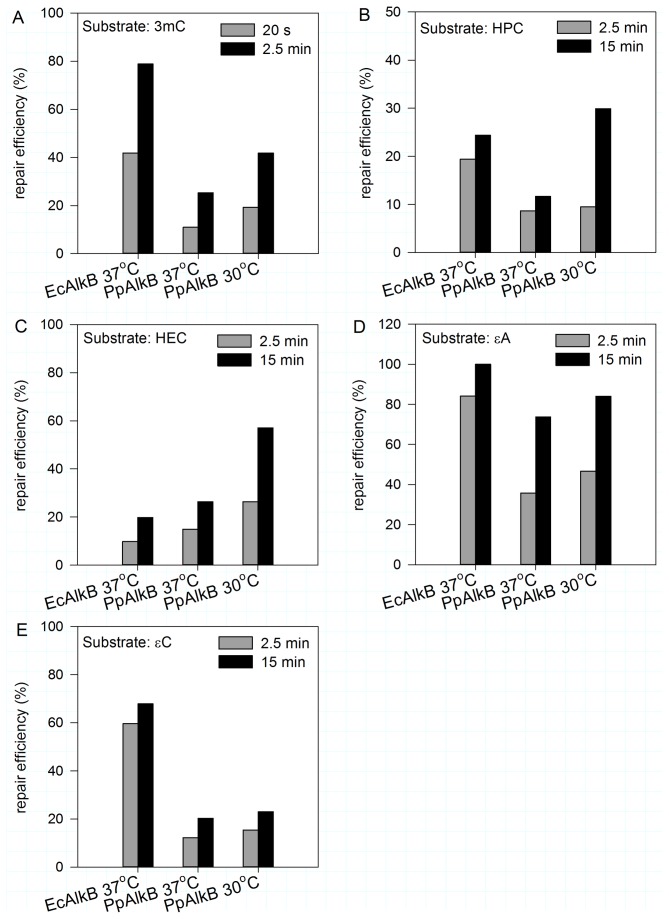

Substrate specificity of P. putida AlkB protein and optimal conditions for in vitro reaction

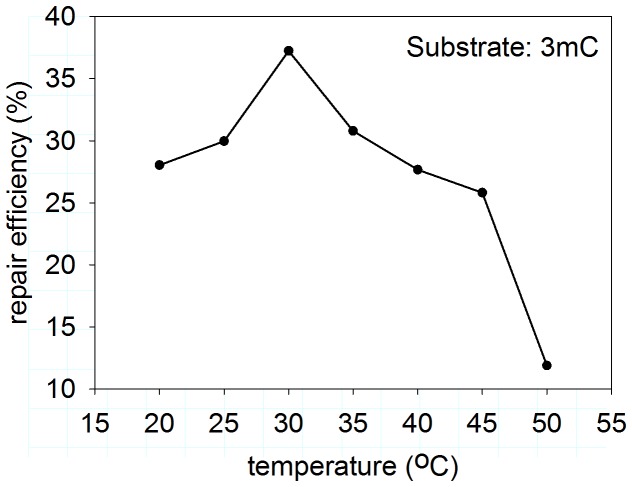

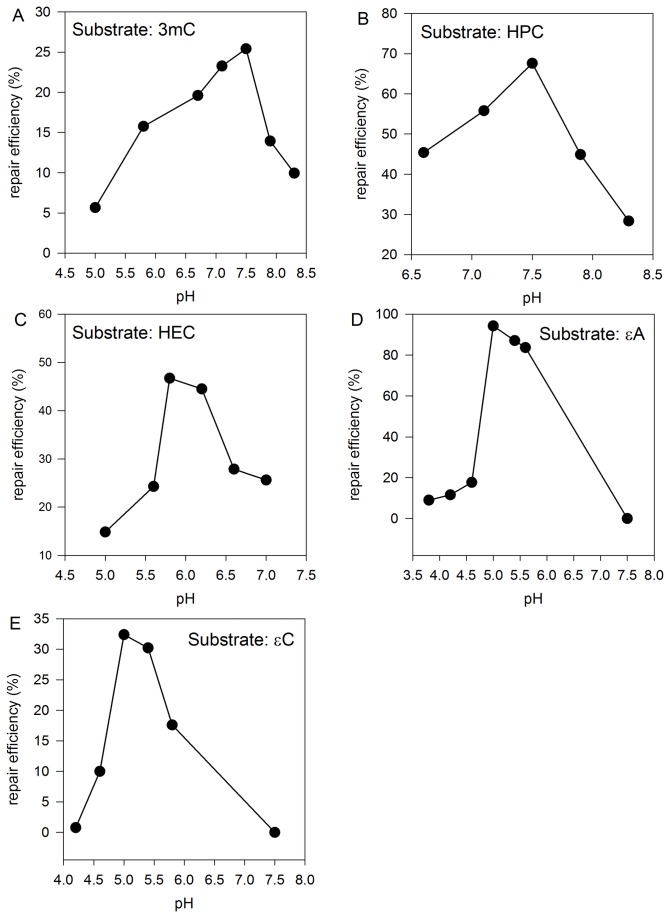

For more precise characterization of PpAlkB, we overexpressed and purified this protein in a heterologous system. Pentamers containing modified bases: 3meC, HPC, HEC, εC or εA were studied as potential substrates for PpAlkB. Using HPLC to separate the modified and unmodified (repaired) oligomers, we found that all the modifications were repaired. Since P. putida is a soil bacterium, the PpAlkB tolerance to temperature was tested. As shown in Figure 9, the optimal temperature for 3meC repair was 30°C. Optimal pH for 3meC and HPC repair was 7.5, for HEC -5.8, for εA and εC – pH 5.0 (see Figure 10 for details). This is in agreement with our previous findings concerning pH dependence of adduct repair rates by EcAlkB [22]; however, in case of PpAlkB, εA and εC were best repaired at higher pH in comparison to EcAlkB (see Discussion). Parallel experiments at optimal pH for each adduct compared Pp and Ec AlkB repair efficiencies. Reactions conducted at various temperatures confirmed that PpAlkB is more active at 30°C than 37°C, suggesting that, in spite of several noticeable differences, the adducts studied are repaired by both dioxygenases with comparable efficiency (Figure 11). Nevertheless, it is worth noting that 3meC, the best substrate for both enzymes, was repaired by PpAlkB about twice less efficiently.

Figure 9. Dependence of 3meC repair by PpAlkB on the reaction temperature.

Samples were assayed for extent of repair at marked temperature values.

Figure 10. The pH dependence of repair rates of the studied adducts by PpAlkB protein.

Samples were assayed for extent of repair at marked pH values at 30°C. The adducts and the conditions applied for their repair were as follows: 3meC (pKa 8.7; Ueda et al. (1963) J Amer Chem 85: 4024), 100 µM Fe(II) 5 pmol PpAlkB, 5 min reaction (A) HPC (pKa 8.6; Borys-Brzywczy et al. (2005) Acta Biochim Pol 52: 149), 100 µM Fe(II) 20 pmol PpAlkB, 15 min reaction (B); HEC (pKa 5.8; Krzyzosiak et al. (1979) Polish J Chem 53: 243), 1 mM Fe(II) 20 pmol PpAlkB, 15 min reaction (C) ;εA (pKa 3.9; Secrist et al. (1972) Biochemistry 11: 3499), 3mM Fe(II) 40 pmol PpAlkB, 15 min reaction (D); and εC (pKa 3.7; Krzyzosiak et al. (1979) Polish J Chem 53: 243), 50 µM Fe(II) 80 pmol PpAlkB, 15 min reaction (E).

Figure 11. The time course of repair of the studied adducts at the pH optimal for each substrate.

Comparison of repair efficiency between EcAlkB at 37°C and PpAlkB at 30 and 37°C. Reactions for each substrate (0.5 nmol) were performed in parallel and differ only in the protein added. The adducts and the conditions applied for their repair were as follows: 3meC, pH 7.5, 100 µM Fe(II), 5 pmol of the studied enzyme (A); HPC pH 7.5, 100 µM Fe(II), 10 pmol of the studied enzyme (B); HEC pH 5.8, 1 mM Fe(II), 10 pmol of the studied enzyme (C); εA pH 5.0 for PpAlkB and 4.6 for EcAlkB, 3 mM Fe(II) 40 pmol of the studied enzyme (D); and εC pH 5.0 for PpAlkB and 4.6 for EcAlkB, 5 mM Fe(II), 80 pmol of the studied enzyme (E).

Discussion

The role of Ada response in protection of P. putida cells against alkylating agents

The aim of this work was to assign the role of Ada, AlkA, and AlkB proteins to the repair of alkylation lesions in P. putida DNA. In silico and in vivo studies disclosed fundamental differences between P. putida and E. coli Ada operon organization and AlkA protein structure as well as different reactions of these bacteria to alkylating agent treatment. Ada operon of P. putida encodes for AlkA and Ada, but not for AlkB, whereas in E. coli ada and alkB comprise one operon and alkA is situated separately, although stays under control of ada promoter. The P. putida genome encodes for three additional repair enzymes: PpTag2, PpAlkA2 and Aag (Figure 1). However, alkA2 is not equally distributed among P. putida isolates. For example, P. putida strain KT2440, used as a model organism in this study, lacks this gene. Among the 11 analyzed P. putida genomes only four carry alkA2.

P. putida and E. coli strains mutated in the ada gene are diametrically opposed in response to alkylating agents, MMS and MNNG (see Table 1 and Results). On the basis of this sensitivity three groups of mutants have been distinguished: insensitive, moderately and highly sensitive. Deletion of the alkA gene in P. putida results in extreme sensitivity to both alkylating agents. In contrast, the E. coli alkA‾ mutant is not more sensitive to them than the wild-type strain. These observations indicate the crucial role of AlkA protein (alkA-encoded 3meA DNA glycosylase II) in protecting P. putida cells against the cytotoxicity of the alkylating agents. However, mutagenicity test revealed that AlkA did not protect P. putida cells against the mutagenic action of MMS/MNNG. Instead, the Ada protein fulfills an anti-mutagenic function (P. putida ada‾ mutants showed an increased frequency of MMS/MNNG-induced RifR mutations, Figure 7A and C). In E. coli alkB‾ strain, MMS-induced mutagenesis measured in argE3→Arg+ reversion system increased about 8-fold in comparison to the wild-type strain [34]. Moreover, the presence of DNA polymerase V (PolV) is indispensable to process 1meA/3meC lesions in an error-prone manner [35]. The lack of this type of response to alkylating agents in P. putida alkB‾ is probably due to different importance of SOS responses and PolV-directed DNA repair in these two bacterial species. Importantly, the majority of bacteria, including pseudomonads, lack chromosomal umuC and umuD genes encoding PolV but carry instead a multiple gene cassette encoding DnaE2, a second copy of the α subunit of DNA polymerase III, and ImuB, a protein related to the Y-family of DNA polymerases [36-38]. Similarly to umuDC, these genes are induced by DNA damage [37]. The fact that the presence of dnaE2 and imuB genes coincides with the lack of umuDC genes in the bacterial genome has suggested that in these species the gene cassette functionally replaces PolV in translesion synthesis [38]. Current studies in our laboratories might elucidate the role of DnaE2 in P. putida tolerance to DNA alkyl damage.

Table 1. Sensitivity of P. putida and E. coli mutants to MNNG and MMS exposure.

| Sensitivity | MNNG |

MMS |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. putida | E. coli | P. putida | E. coli | |

| Survival like wild-type | alkB | alkA | alkB | alkA |

| alkB | ||||

|

|

|

tag

|

|

|

| Moderately sensitive | ada | ada | ada | alkB |

|

|

ada alkB

|

|

ada alkB

|

ada alkB

|

| Very sensitive | alkA alkB | alkA alkB | alkA alkB | alkA alkB |

| alkA | ada alkA | alkA | ada | |

| ada alkA | ada alkB | ada alkA | ada alkA | |

| ada alkA alkB | ada alkA alkB | ada alkA alkB | ada alkA alkB | |

The comparison of sequences of AlkA from P. putida, E. coli, and D. radiodurans (DrAlkA) revealed great similarity of PpAlkA to DrAlkA but not to EcAlkA (Figure 3). Both enzymes consist of two helical domains separated by a wide DNA-binding cleft but devoid of the third N-terminal α/β domain present in EcAlkA [12]; hence, the activity towards 3meC and 1meA, the most efficiently repaired canonical substrates of AlkB dioxygenase, characterizes both PpAlkA and DrAlkA enzymes. Of noted, species lacking the AlkB homolog developed AlkA proteins capable of repair of its canonical substrates [13,30]. Thus, it can be proposed that P. putida (at least KT2440) is on the developmental path that would eventually results in complete lack of the alkB gene.

The alkA but Not alkB Gene Is Induced by the Ada Response in P. putida

The Ada response has been comprehensively studied in Enterobacteria [39,40]. In spite of the high conservation of its function, the Ada regulon is diversely organized [41,42], as confirmed by our results. We have shown that in P. putida the level of transcription from the promoter located upstream of alkA is induced significantly after exposure to MMS (Figure 4). Its expression elevated about 60-fold, whereas in E. coli the increase was only 10-fold [39]. In contrast, the P. putida alkB gene was not induced after MMS treatment although it exhibited a constantly significant level of expression, regardless of the presence of the alkylating agent (Figure 4).

In E. coli, two promoter regions, ada and alkA, show highly similar nucleotide fragments responsible for the interaction with the Ada protein, respectively, AAAGCGCA and AAAGCAA [43,44]. The alkA promoter region of P. putida seems to preserve the E. coli Ada box core in the form of ATT(N) 6GCAA (Figure 3). Additionally, the consensus sequence of this promoter lies from -35/-10 boxes in the distance similar to that of E. coli ada and aidB promoters, which implies the interaction with RNA polymerase through the CTD domain of Ada protein [45]. The ada promoter consensus is highly conserved among bacteria. In Salmonella typhimurium, it is in the form of GAATTAAAACGCA although the Ada protein shows lower transcription factor activity than the E. coli protein [42]. On the other hand, the ada and aidB promoters of E. coli interact with the Ada protein through the core of AAT(N) 6GCAA sequence [46], which is perfectly preserved in the putative aidB promoter of P. putida (Figure 4).

Motif identification shed more light on the Ada box occurrence. He and co-workers [30] showed that the promoter structure required for Ada binding in E. coli consists of box A (AAT) and B (GCAA), both being responsible for specific sequence interactions. Two Arg residues, 45 and 71, of E. coli Ada protein form a net of hydrogen bonding with thymine residues. The A box in P. putida alkA promoter can be considered as conserved in the form of (-79)-5’-ATT-3’-(-77), allowing for interaction with the Ada protein (Figure 4). The well conserved B box is separated by 6 nucleotides. There is no doubt that in P. putida strains Ada boxes are preserved in promoter regions of alkA and aidB genes with three A/T base pair in A box and GCAA in B box (Figure 3).

The Ada box cannot be identified with high fidelity in the promoter regions of the alkB gene in P. putida species (it was found only in three of them with P-value below 0.01); nevertheless, all of these promoter regions contain putative -35/-10 boxes (Figure 3). This suggests that the basal expression of the alkB genes in P. putida does not depend on the Ada regulator (the basal expression was also increased in P. putida ada‾ strain and in E. coli) or any other transcriptional factor.

It has been established that in E. coli basal expression of the ada gene results in about 1-2 molecules of Ada [41]. This seems not to be true for P. putida Ada regulon since the promoter for alkA-ada operon producing the Ada protein did not show any basal expression. Thus, at the moment, the initiation of Ada response in P. putida cannot be explained.

Although the Ada motifs are almost identical in promoter regions of PpalkA and Ecada, exchanging these motifs between the two species did not result in proper functioning in both backgrounds. This surprising phenomenon can be explained as follows: i) the spaces between Ada and -35 boxes are different in these two promoters potentially affecting the interaction with RNA polymerases; ii) in spite of perfect conservation of P. putida Ada residues responsible for specific interaction with the Ada box, tiny differences between E. coli and P. putida Ada boxes prevent cross-species GFP induction. The PpAda protein seems to rely less on the interaction with the A box since removal of this box and additional four bases upstream of it still resulted in slight induction by the methylating agents (Figure 4). It appears as if even one A base can establish some interaction with PpAda, provided that the B box is present.

The PpalkA and PpGcdH promoters could be considered to be strongly regulated by the Ada protein since C is the base 5’-adjacent to the B box. Landini and Volkert [46] have shown that the difference in this position between ada and alkA/aidB E. coli promoters, consisting of C and A base, respectively, renders the Ada protein with about 10-fold higher affinity for the ada promoter.

The majority of earlier induction experiments on the E. coli Ada regulon genes were conducted using episomal multicopy vectors. A similar approach was undertaken in the present study on P. putida Ada regulon. Nevertheless, these experiments should be considered preliminary. A more reliable and trustworthy experimental approach would be to test the induction from single copy chromosome constructs. To summarize, the results presented in this study indicate that the P. putida alkA-ada operon is strongly induced in the course of Ada response to alkylating agents, interacting not only with E. coli AlkA substrates but also with 1meA and 3meC, considered to be the most efficiently repaired AlkB substrates. Moreover, the promoter sequence of P. putida alkB gene is active at moderate levels independently of the presence of any exogenous alkylating agent, indicating that, unlike in E. coli, in P. putida the AlkB protein is expressed constitutively and is not under control of the Ada response.

Characterization of P. putida AlkB protein – substrate specificity and optimal conditions for in vitro reaction

E. coli AlkB protein has been described as a single-protein repair system protecting cellular DNA and RNA against the cytotoxic and mutagenic activities of alkylating agents, tumorigenic chemicals and also those used in anticancer therapy. EcAlkB homologs exist in almost all organisms. Our in silico analysis allowed identification of 1943 sequences of different AlkB family members and eight novel subfamilies of AlkB homologs [23]. In the present work we characterized the AlkB protein of P. putida (PpAlkB) to compare its activity and substrate specificity to that of E. coli AlkB.

Recently, we have characterized the substrate specificity and some aspects of molecular mechanism of action of E. coli AlkB, and established that EcAlkB repair efficiency is pH- and Fe(II)-concentration dependent, which correlates with the substrate pKa. The experimental data and molecular modeling revealed that E. coli AlkB dioxygenase preferentially recognizes and repairs protonated substrates. Crucial for this recognition is the negatively charged carboxylic group of Asp135 side chain in the enzyme active center [22]. E. coli and P. putida AlkB sequences alignment showed that the organization of active centers is identical, including Asp135 (Asp136 in the case of P. putida KT2440 strain). The screening experiments performed here confirmed all of our previous findings. For 3meC, HPC, and HEC substrates, the optimal pH of the repair reaction was about one unit below their pKa where the adducts existed in the cationic form (Figure 11). For adducts with low pKa values, εA and εC, the optimal pH is a compromise between the substrate protonation and other factors determining the efficiency of repair (discussed in details in [22]). The optimal pH for εA and εC repair by PpAlkB is 5.0, slightly higher than the 4.6 for EcAlkB [22], suggesting that the former may be more susceptible to unfolding under acidic conditions. Similarly as in the case of EcAlkB, the etheno adducts were less efficiently repaired by PpAlkB than the hydroxyethano and hydroxypropano adducts. The presence of AlkB dioxygenase in P. putida cells, in spite of the extended substrate specificity of P. putida AlkA, suggests PpAlkB role in repair of still other cytotoxic/mutagenic substrates.

In conclusion, the results presented here indicate different organization of P. putida and E. coli Ada response and also quite different functions of the individual proteins induced by Ada. The AlkA protein plays a crucial role in protecting P. putida cells against cytotoxic but not mutagenic action of alkylating agents, whereas the Ada protein shows a strong anti-mutagenic function. We have not been able to connect any of these functions to PpAlkB, in spite of its enzymatic activity identical to that of EcAlkB. Ada regulon organization and promoter activity studies indicate, apart from the Ada response, constitutive expression of PpAlkB. This discovery, in spite of the similarity of P. putida and E. coli AlkB sequences, shows a different role of PpAlkB in protecting P. putida cells against alkylating agents of endo- or exogenous origin. On the basis of analogy to organization of anti-alkylating agent defense system in E. coli, we suppose that PpAlkB plays its role together with constitutively expressed Tag and Ogt proteins. Regulation of P. putida, but not of E. coli, AlkB resembles the situation in higher organisms where ALKBHs are widely expressed in normal tissues. Therefore, P. putida can serve as a model organism for establishing novel ALKBHs functions in higher eukaryotes. The regulation of ALKBHs expression is essential for understanding the basis of this system since upregulation of ALKBHs underlies tumor formation and its resistance to alkylating chemotherapy.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 2. Liquid media used were Luria-Bertani broth (LB) [47], M9 minimal medium [48], and E medium composed of C salts [49], glucose (0.5%), casamino acids (0.2%), and thiamine (10 µg/ml). The solid media contained 1.5% Difco agar. LCA medium (1% trypton, 0.5% yeast extract, 1% NaCl, 0.25% MgSO4 × 7H2O, 2.5 mM CaCl2) was solidified with Difco agar at 0.6% [47]. Antibiotics were added at the following concentrations: rifampicin at 100 µg/ml, carbenicillin at 100 µg/ml for E. coli and 2 mg/ml for P. putida, kanamycin at 50 µg/ml, and gentamicin at 10 µg/ml. Bacteria were grown on agar plates or in liquid cultures with shaking (250 rpm), E. coli at 37°C, and P. putida at 30°C. E. coli was electrotransformed as described by Sharma and Schimke [50] and P. putida as in ref [51]. . E. coli strains DH5α (Invitrogen), and CC118 λpir [52] were used for DNA cloning, and HB101 [53] as a host for helper plasmid pRK2013 [54], necessary for mobilization of non-conjugative plasmids.

Table 2. Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or construction | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169 (Φ80 lacZΔM15) recA1 endA1 hsdR17 thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | Invitrogen |

| HB101 | subE44 subF58 hsdS3 (rB- mB-) recA13 ara-14 proA2 lacY1 galK2 rpsL20 | [53] |

| xyl-5 mtl-1 | ||

| CC118 λpir | Δ(ara-leu) araD ΔlacX74 galE galK phoA20 thi-1 rpsE rpoB argE (Am) | [52] |

| recA1 λpir phage lysogen | ||

| BL21(DE3)pLysS | F- ompT gal dcm lon hsdSB(rB- mB-) λ(DE3) pLysS(cmR) | Invitrogen |

| AB1157 | thr-1, araC14, leuB6(Am), Δ(gpt-proA)62, lacY1, tsx-33, qsr’-0, glnV44(AS) | [71] |

| galK2(Oc), LAM-, Rac-0, hisG4(Oc), rfbC1, mgl-51, rpoS396(Am) rpsL31(strR), | ||

| kdgK51, xylA5, mtl-1, argE3(Oc), thi-1 | ||

| AB1157alkA | As AB1157 but ∆alkA::km | This study |

| DM12 | As AB1157 but ∆alkB::km | [23] |

| AB1157ada | As AB1157 but ada10::Tn10 ; constructed by P1 phage transduction | This study |

| BS87 | As AB1157 but ∆alkB::ap | [72] |

| BS87alkA | BS87 but ∆alkA::km; constructed by P1 phage transduction | This study |

| AB1157alkAada | As AB1157 but ∆alkA::km; ada10::Tn10 | This study |

| AB1157alkBada | As AB1157 but ∆alkB::km; ada10::Tn10 | This study |

| BS87alkAada | As BS87 but ∆alkA::km; ada10::Tn10 | This study |

| UC978 | araD8l Δ(uvrB-bio) ∆ogt1::km ada10::Tn10; used as a donor of ada10::Tn10 | [73] |

| P. putida | ||

| PaW85 | Wild-type, isogenic to KT2440 | [55,56] |

| PaWAlkB | PaW85, ∆alkB::gm | This study |

| PaWAda | PaW85, Δada::km | This study |

| PaWAlkA | PaW85, ∆alkA | This study |

| PaWAdaAlkB | PaW85, Δada::km; ΔalkB::gm | This study |

| PaWAlkAAlkB | PaW85, ∆alkA; ΔalkB::gm | This study |

| PaWAlkAAda | PaW85, ∆alkA; ∆ada::km | This study |

| PaWAlkAAdaAlkB | PaW85, ΔalkA; ∆ada::km; ΔalkB::gm | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescript KS (+) | Cloning vector (Apr) | Stratagene |

| pUTmini-Tn5 Km2 | Delivery plasmid for mini-Tn5 Km2 (Apr Kmr) | [59] |

| pBK-miniTn7-ΩGm | pUC19-based delivery plasmid for miniTn7-ΩGm (Gmr, Apr) | [58] |

| pGP704 L | Delivery plasmid for homologous recombination (Apr) | [57] |

| pRK2013 | Helper plasmid for conjugal transfer of pGP704 L (Kmr) | [54] |

| pEMG | Cloning vector (Kmr), oriR6K, lacZα with two flanking I-SceI sites | [61] |

| pSW (I-SceI) | The I-SceI-expression plasmid (Apr) | [62] |

| pKSalkB | pBluescript KS (+) containing the PCR-amplified sequence of the alkB gene | This study |

| in SacI and Acc65I restriction sites | ||

| pKSΔalkB::gm | alkB in pKSalkB is interrupted with the Gmr gene from pBK-miniTn7-ΩGm | This study |

| by replacing SacII and HindIII-generated fragment from alkB by the Gmr gene | ||

| pGP704ΔalkB::gm | pGP704 L with SacI-Acc65I fragment of ΔalkB::gm from pKS∆alkB::gm | This study |

| in vector plasmid opened with the same restrictases | ||

| pKSada | pBluescript KS(+) containing the PCR-amplified sequence of the ada gene in SacI | This study |

| and XbaI restriction sites | ||

| pKSΔada::km | ada in pKSada is interrupted with the Kmr gene from pUTmini-Tn5 Km2 by | This study |

| replacing Cfr42I and NcoI-generated fragment from ada by the Kmr gene | ||

| pGP704Δada::km | pGP704 L with SacI-XbaI fragment of Δada::km from pKSΔada::km in vector | This study |

| plasmid opened with the same restrictases | ||

| pEMGalkA | pEMG containing PCR-amplified sequence of alkA in SacI and XbaI sites | This study |

| pVB1x | A low copy number vector (~6 copies/cell) with a toluic acid inducible | Vectron Biosolutions |

| promoter (Apr) | ||

| pVB1x:EcalkB | As pVB1x but expressing EcalkB | This study |

| pVB1x:PpalkB | As pVB1x but expressing PpalkB | This study |

| pET28a(+) | Expression vector (Kmr) | Invitrogen |

| pET28a::PpalkB | As pET28a(+) but expressing PpalkB | This study |

| pPROBE-NT | Promoterless vector with gfp reporter (Kmr) | [63] |

| pPROBE-AT | Promoterless vector with gfp reporter (Apr) | [63] |

| pPROBE-NT:alkAp | As pPROBE-NT with P. putida alkA promoter (-100, -1) | This study |

| pPROBE-NT:alkBp | As pPROBE-NT with P. putida alkB promoter (-100, -1) | This study |

| pPROBE-NT:alkBpΔ(-68,-18) | As pPROBE-NT with P. putida alkB promoter (-100, -1) | This study |

| with deletion of (-68,-18) nucleotides | ||

| pPROBE-NT:adap | As pPROBE-NT with P. putida ada promoter (-100, -1) | This study |

| pPROBE-NT:Ecadap | As pPROBE-NT with E. coli ada promoter (-100, -1) | This study |

| pPROBE-AT:alkAp | As pPROBE-AT with P. putida alkA promoter (-100, -1) | This study |

| pPROBE-AT:alkBp | As pPROBE-AT with P. putida alkB promoter (-100, -1) | This study |

| pPROBE-KT:kanp | As pPROBE-KT but with kanamycin resistance gene promoter | Prof. S. E. Lindow |

| Berkeley, California |

Construction of P. putida Ada and AlkB-Deficient Strains

The sequences of alkB gene encoding for oxidative demethylase (PP_3400) and ada gene encoding for methyltransferase (PP_0706) of P. putida strain KT2440 were obtained from The Comprehensive Microbial Resource website of the J. Craig Venter Institute (http://cmr.jcvi.org). These genes were amplified by PCR from the genomic DNA of P. putida strain PaW85 [55] which is isogenic to KT2440 [56]. Thereafter, the internal sequences of the amplified genes were replaced with antibiotic resistance marker genes and the DNA fragments carrying the antibiotic resistance gene and sequences from 5´- and 3´- ends of the alkB or ada gene were inserted into plasmid pGP704L [57] unable to replicate in hosts other than E. coli CC118λpir [52]. The wild-type sequences of the alkB and ada genes present in the chromosome of P. putida strain PaW85 were replaced with the interrupted ones by homologous recombination. Derivatives of the plasmid pGP704L carrying replacement cassettes were conjugatively transferred into P. putida PaW85 using helper plasmid pRK2013 [54]. The integration of whole delivery plasmid into a target site was excluded by testing the transconjugants for resistance to carbenicillin (only those unable to grow in the presence of 3 mg/ml carbenicillin were considered to be true recombinants, generated as a result of double recombination events). PaW85 derivatives with the desired deletions were verified by PCR analysis.

For the construction of P. putida strain lacking alkB (PaWAlkB), the 648-bp alkB gene was amplified by PCR from the genomic DNA of P. putida with primers ppalkBFwSacuus and ppalkBRevAccuus (see Table S1). The amplified 1275-bp DNA fragment containing the alkB gene was cleaved with SacI and Acc65I restriction enzymes (restriction sites in primers are underlined) and inserted into the vector plasmid pBluescript KS (+) opened with the same restrictases to obtain plasmid pKSalkB. The Gmr gene was amplified by PCR from plasmid pBK-miniTn7-ΩGm [58] using primers GmY and GmA. The 771-bp PCR fragment containing the Gmr gene was subsequently inserted into plasmid pKSalkB cleaved with SacII- and HindIII, and replaced the 850-bp fragment in the alkB gene in plasmid pKSalkB to obtain plasmid pKS∆alkB::gm. The SacII and HindIII-ends were blunt-ended before ligation. The SacI- and Acc65I-generated DNA fragment containing the ∆alkB::gm sequence from plasmid pKS∆alkB::gm was inserted into plasmid pGP704 L cleaved with the same enzymes. The resulting plasmid pGP704∆alkB::gm was selected in E. coli strain CC118 λpir. The PaW85 ΔalkB::gm knockout mutant PaWAlkB was verified by PCR analysis using primers ppalkBlookusuus and GmA.

For the construction of P. putida strain lacking ada (PaWAda), the 1053-bp ada gene was amplified by PCR from the genomic DNA of P. putida with primers ppadaFwSac and ppadaRevXba. The amplified 1098 bp DNA fragment containing the ada gene was cleaved with SacI and XbaI restriction enzymes and inserted into the vector plasmid pBluescript KS (+) opened with the same restrictases to obtain plasmid pKSada. The Kmr gene was amplified by PCR from plasmid pUTmini-Tn5 Km2 [59] by using the primer KmSac [60]. The Ecl136II-cleaved DNA fragment containing the Kmr gene was used to replace the Cfr42I- and NcoI-generated 734-bp fragment in the ada gene in plasmid pKSada to obtain plasmid pKS∆ada::km. The Cfr42I and NcoI-ends were blunt-ended before ligation. The SacI- and XbaI-generated DNA fragment containing the Δada::km sequence from plasmid pKS∆ada::km was inserted into plasmid pGP704 L cleaved with the same enzymes. The resulting plasmid pGP704∆ada::km was selected in E. coli strain CC118 λpir. The PaW85 Δada::km knockout mutant PaWAda was verified by PCR analysis using primers ppadalookus and KmH.

Construction of P. putida AlkA-deficient strain

For the construction of P. putida strain lacking the sequence of the alkA gene coding for DNA 3meA glycosylase, we used an adaptation of the protocol for P. putida [61]. The alkA gene (PP_0705) was amplified by PCR from the genomic DNA of P. putida. Two pairs of PCR primers that each span 500 bp of either upstream or downstream sequence of the alkA gene were designated ppAlkA1SacIFw and ppAlkA1Rev, and ppAlkA2Fw and ppAlkA2XbaIRev, respectively. SacI and XbaI restriction sites were included in the primers. Firstly, the 573 bp PCR product generated by primers ppAlkA1SacIFw and ppAlkA1Rev, and the 623 bp PCR product generated by primers ppAlkA2Fw and ppAlkA2XbaIRev were prepared. Then, the second PCR reaction was performed with 1 µl of each of the reaction products of the first PCR as a template using primers ppAlkA1SacIFw and ppAlkA2XbaIRev. After purification the second PCR product was cleaved with SacI and XbaI enzymes and inserted into the vector plasmid pEMG [61] cut with the same restrictases to obtain plasmid pEMGalkA selected in E. coli strain CC118 λpir. Plasmid pEMGalkA was then electroporated into the recipient strain of P. putida PaW85. Several colonies were then streaked and primers ppAlkA1SacIFw and ppAlkA2XbaIRev were used to check for cointegration. The plasmid pSW (I-SceI) [62] was electroporated into the P. putida PaW85 strain carrying the cointegrated alkA gene The presence of pSW (I-SceI) plasmid was verified by PCR analysis using primers pSW-F and pSW-R [61]. To obtain separate colonies several P. putida clones carrying the alkA gene and pSW (I-SceI) were streaked onto plates containing carbenicillin 3 mg/ml. To check for loss of the cointegrated plasmid pEMGalkA, single colonies were then streaked onto LB and LB kanamycin plates. Selected kanamycin sensitive clones were further analyzed by PCR using primers ppAlkA1SacIFw and ppAlkA2XbaIRev. In the next step, the potential clone bearing the alkA deletion was grown overnight with shaking, in LB medium without antibiotics, and dilutions in LB media were plated to obtain separate colonies. Several colonies were then restreaked in LB and LB carbenicillin media. The loss of the pSW (I-SceI) plasmid in carbenicillin sensitive clones was checked by PCR analysis using primers pSW-F and pSW-R. The PaW85 ΔalkA knockout mutant PaWAlkA was verified by PCR analysis using primers ppAlkAKI and ppAlkAKII.

Construction of P. putida double and triple mutants

To isolate double mutants of PaW85 lacking both AlkB function and either alkyltransferase Ada (strain PaWAdaAlkB) or 3meA glycosylase activity encoded by the alkA gene (strain PaWAlkAAlkB), the existing PaWAda and PaWAlkA strains were used as recipients. ∆alkB::gm sequence from the plasmid pGP704∆alkB::gm was used to delete the original alkB sequence from these strains. To verify that the sequence of the original alkB gene was replaced by the modified one, we examined all the constructed double knockout strains by PCR analysis using the primers described above. To isolate double mutant of PaW85 lacking both the AlkA and Ada functions (strain PaWAlkAAda), the existing PaWAda strain was used as a recipient and the alkA gene was deleted as described above. To isolate the triple mutant of PaW85 lacking AlkA, Ada and AlkB function (strain PaWAlkAAdaAlkB), the existing PaWAdaAlkB strain was used as a recipient, and the alkA gene was deleted using the same method as for construction of PaWAlkA.

Plasmid construction for PpAlkB overexpression/complementation and for promoter induction assays

The pET28(a) and pVB1x plasmids were used to insert P. putida alkB gene PCR product produced with Pputup/Pputdn primers (Table S2). Selected primers allowed for the addition of NdeI and XhoI restriction sites to the PCR product and subsequent digestion and ligation with plasmids digested in the same way.

The pPROBE-NT plasmid [63] allowing the insertion of the promoter sequence upstream of the gene coding for the GFP protein was used to monitor the activity of P. putida alkA, alkB, and ada promoters. The PCR products obtained with PpalkAH1/PpalkAdE, PpalkBH1/PpalkBdE, PpadauH1/PpadadnE primer pairs on P. putida genomic DNA allowed cleavage with HindIII and EcoRI and subsequent insertion into pPROBE-NT. The DNA sequences locating at the positions -100 to -1 from the ATG start codons of alkB, ada and alkA genes were inserted into the promoter probe vector to obtain the plasmids pPROBE-NT:alkBp (alkBp), pPROBE-NT:adap (adap), and pPROBE-NT:alkAp (alkAp). Additionally, the promoter sequence for the alkB gene with region deleted for -68 to -18 nucleotides was used to confirm the putative sequences (pPROBE-NT:alkBpΔ). To investigate the induction of alkA and alkB promoters in P. putida ada‾ strain which harbors kanamycin resistance, the pPROBE-AT vector (carbenicillin resistance) was used in place of pPROBE-NT. Also the pPROBE-NT construct with E. coli ada promoter (-100, -1) was prepared. The pPROBE-KT:kanp construct expressing GFP under the strong kanamycin resistance gene promoter was used to verify the experimental protocol [63]. Primers are listed in Table S2.

The deletion/mutation constructs of pPROBE-NT:alkAp were prepared by site directed mutagenesis with the following primers: A box del – AalkAup/AalkAdn; B box del – BalkAup/BalkAdn; AB boxes del – ABalkAup/ABalkAdn; A box mut – AmalkAup/AmalkAdn; AA box del – AaalkAup/AAalkAdn (for details see Figure 4).

All the constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Survival and mutagenesis assays

To estimate the survival of tested strains, bacteria were grown in E medium to OD600 = 0.5-0.6, treated with MMS (20 or 50 mM) or MNNG (2 or 5 µg/ml) for indicated times (5 to 60 min), centrifuged, washed, suspended in the same volume of fresh medium, diluted, and plated on LB plates. After one day of incubation, the colonies of viable cells were counted and the percent of survivors calculated.

The sensitivity of bacteria to MMS and MNNG was also examined by employing the drop test. P. putida strains were grown overnight or until mid-exponential phase in liquid LB medium. Bacterial cultures were then serially diluted into M9 medium, and diluted cultures (1µl) were spotted onto agar plates containing LB or LB supplemented with MMS (0.5 mM) or MNNG (0.74 µg/ml). Images were taken after two days of incubation of bacteria at 30°C.

To test for mutagenicity, MMS (20 mM)- or MNNG (2 µg/ml for P. putida and 5 µg/ml for E. coli)-treated bacteria and non-treated controls were diluted 1:10 in E medium, grown overnight to express the mutations, and plated on LB plates for viable cells and on LB plates containing rifampicin for RifR mutants after one day of incubation at 30°C. Following the counts, the frequencies of RifR mutants (number of RifR mutants per 108 cells) were calculated.

For complementation assays, E. coli AB1157 alkB‾ strain DM12 harboring the pVB1x plasmid expressing P. putida or E. coli alkB (“empty” pVB1x plasmid served as a control) were treated for 15 min with 20 mM MMS, centrifuged, washed with C salts, resuspended and then diluted 1:10 in E medium, grown overnight, and plated on LB plates for viable cells (one day of incubation) and on E-Arg plates for Arg+ revertants (two days of incubation). Following the counts, the frequencies of Arg+ reversions (number of Arg+ revertants per 108 cells) were calculated.

Phage survival assay

For the phage survival test, M13 (ssDNA) and MS2 (ssRNA) phages were used. The E. coli alkB‾ F+ strain bearing the pVB1x “empty” plasmid as a control or the plasmid expressing EcAlkB or PpAlkB was grown to stationary phase in E-Pro medium supplemented with kanamycin (50 µg/ml) and carbenicillin (100 µg/ml), and diluted 30-fold in fresh medium. At OD600 = 0.2 and 0.8, 2 mM toluic acid and 5 mM MgCl2 were added, respectively. Then, 150 µl of bacteria was mixed with 100 µl of phage preparation, incubated for 10 min at 37°C, mixed with 3 ml LCA prewarmed to 45°C and poured onto LB plates. Plaques were counted after 5-8 h (MS 2) or 18-24 h (M13) of incubation at 37°C and PFUs (Plaque Forming Units per ml) were calculated. To modify the phages, M13 or MS2 suspensions in C salts were treated with 15 mM MMS or 20 mM CAA for 30 min at 30°C.

Expression, purification, and in vitro activity assays of PpAlkB protein

PpAlkB expression and purification

The pET28(a):PpalkB construct was introduced into E. coli BL21 pLysS strain. The bacteria were grown in 1 L of LB supplemented with kanamycin (100 µg/ml) and chloramphenicol (20 µg/ml) at 37°C. At the OD600 of ~ 0.6, the culture was cooled to 16°C and expression of PpAlkB was induced with 0.1 mM IPTG. After overnight at 16°C, bacteria were spun down (15 min, 6000 rpm, 4°C) and sonicated in 45 ml of Lysis Buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazol, 100 µM PMSF, 1 mM DTT, and 0.1% Triton X-100). The lysate was centrifuged (45 min, 12,000 rpm, 4°C) and the supernatant incubated with 400 µl of 50% His-Select-Nickel Affinity Gel (Sigma-Aldrich). The resin was washed with Lysis Buffer and the protein eluted with Elution Buffer (Lysis Buffer supplemented with 300 mM imidazol). Protein was dialyzed against Dialysis Buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 300 mM NaCl, 100 µM PMSF, 1 mM DTT, and 25% glycerol).

Preparation of AlkB substrates

Substrates were prepared as in ref [20,22]. . Briefly, pentadeoxynucleotides, TTXTT, where X is cytosine (C) or adenine (A), were reacted with chloroacetaldehyde (CAA), acrolein (ACR) or methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) obtaining derivatives containing modified cytosines: HEC, εC, 3meC, and HPC or adenine: εA. After HPLC purification, the modified pentamers were used as AlkB substrates.

AlkB assay

The 20 µL of reaction mixtures contained 50 mM appropriate buffer, 1 mM DTT, different concentrations of Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2, 50 µM 2-oxoglutarate, and 0.5 nmol of the substrate. Reactions were started by the addition of purified Pp or EcAlkB protein or the studied component, allowed to proceed at various temperatures (as indicated in the text and figure legends), stopped by the addition of 230 µl ice-cold water, frozen at -20°C to deactivate the enzyme, and then analyzed by HPLC. The Fe(II) ion concentrations were adjusted [22] according to concentrations of H+ and Fe(II) cations optimal for the repair of the studied adducts by the EcAlkB protein.

Promoter induction assay

To study the activity of P. putida ada, alkB and alkA as well as E. coli ada promoters, the pPROBE-NT:adap, pPROBE-NT:alkBp pPROBE-NT:alkAp and pPROBE-NT:Ecadap constructs were introduced into P. putida KT2440 wild-type cells by electrotransformation. The pPROBE-NT (promoterless) and pPROBE-KT:kanp (kanamycin promoter) were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Two isolates were tested for promoter induction. The overnight LB cultures of P. putida strains harboring selected plasmids were used to inoculate E medium and were grown to OD600 0.5-0.6. At this point, 20 mM MMS or 2 or 5 µg/ml MNNG was added. After 15 min of incubation, bacteria were spun down (5000 rpm, 4 min), suspended in fresh E medium (supplemented with kanamycin if needed) and cultured at 30°C with shaking. The fluorescence level of synthesized GFP was measured in 100 µl of bacterial culture placed in 96-well plates in triplicate. Fluorescence was induced at 485/20 nm and detected at 528/20 nm (sensitivity set at 50), whereas cell density was measured by absorbance at 600 nm using Synergy HTI Microplate Reader (Biotech). Additionally, the above constructs were tested analogously in E. coli AB1157 strain. For P. putida ada‾ strain, the pPROBE-AT backbone was used instead of pPROBE-NT.

To normalize the fluorescence, the absolute fluorescence (Fa) was divided by absorbance value (OD600), giving Relative Fluorescence Units: RFU = Fa/OD600. To eliminate the impact of MMS and MNNG (methylation reaction) on GFP fluorescence level, the fluorescence of recombinant eGFP protein (Clontech) was measured in the presence of 50 mM MMS or 5 µg/ml MNNG, with no change in fluorescence levels.

Sequence alignments and analysis of the P. putida Ada regulon

Ada regulon organization

The genome sequences of E. coli K-12 DH10B (NC_010473), K-12 MG1655 (NC_000913), BW2952 (NC_012759), B REL606 (NC_012967), CFT073 (NC_004431), HS (NC_009800), O157:H7 EC4115 (NC_011353), and SE11 (NC_011415) and P. putida KT2440 (NC_002947) [64], F1 (NC_009512), GB-1 (NC_010322), S16 (NC_015733), BIRD-1 (NC_017530), ND6 (NC_017986), DOT-T1E (NC_018220), HB3267 (NC_019905), H8234 (NC_021491), NBRC 14164 (NC_021505), and W619 (NC_010501) were retrieved from NCBI database. The particular genes were identified by BLAST [65] as well as with Conserved Domain databases [66] at NCBI (AlkB: COG3145; AlkA: COG0122; AlkA-N: cl05528; Tag: COG2818; Aag: cd00540; AidB: cd01154). All manipulations were done and pictures prepared with Geneious 6.1.5 (Biomatters, http://www.geneious.com).

P. putida and E. coli alkyl damage glycosylases and acyl-CoA dehydrogenases proteins clustering

To analyze the relationship between P. putida AlkA2 and Tag2 proteins, the CLANS [67] protein clustering of P. putida and E. coli glycosylases coping with alkyl damages was performed with Aag Representatives (family cd00540, NCBI) using the sequences in File S1.

To identify putative aidB genes in P. putida KT2440 genome, the acyl-CoA dehydrogenases of P. putida and E. coli species were retrieved from the protein family cd01154 (NCBI). This family consists of mean number of 15 and 4 AidB sequences for each P. putida and E. coli species, respectively. These sequences were grouped into fasta file (File S2) and CLANS [67] analysis was performed. Additionally, the search in MicrobesOnline database (http://www.microbesonline.org [64]) was undertaken using as a query the E. coli K-12 DH10B aidB genomic context, giving as a result the P. putida KT2440 PP_0158 locus – putative gcdH dehydrogenase.

Sequence alignment of AlkA and Ada proteins

P. putida KT2440 (PP_0705; Gene ID: 1044536), Deinococcus radiodurans R1 (DR_2584; Gene ID: 1797538) and E. coli K-12 DH10B (ECDH10B_2218; Gene ID: 6059665) AlkAs were aligned with P. putida GB-1 (PputGB1_2545; Gene ID: 5870334) AlkA2 using ClustalW [68] with the following parameters: Cost matrix – ID, Gap open cost -15, Gap extend cost -0.5. Domain searches were performed with InterProScan and Pfam domains were visualized. The ClustalW alignment and InterProScan search tools are implemented in Geneious Pro 6.1.5, and were used as such. Also the P. putida and D. radiodurans alkA with genetic context 500 bp upstream and downstream were checked for the presence of longer ORFs and the lengths of current ORFs were confirmed.

The P. putida (PP_0706; Gene ID: 1044537) and E. coli K-12 DH10B (ECDH10B_2370; Gene ID: 6059404) Ada proteins were aligned with ClustalW [68] with the following parameters: Cost matrix – ID, Gap open cost -10, Gap extend cost -0.1.

Analysis of promoter regions of ada, alkA, alkB, and aidB genes

The promoter sequences (-100, -1) of ada, alkA, alkB and aidB, genes of above mentioned 8 E. coli and 5 P. putida strains were retrieved from genomic sequences and grouped into one file (File S3). Additionally, the P. putida GB-1 (PputGB1_2545; Gene ID: 5870334) and S16 (PPS_2874; Gene ID: 10938506) alkA2 promoter sequences were added. Although alkA2 genes are annotated as alcohol dehydrogenases, the protein sequence Conserved Domain search [66] shows AlkA domain architecture (COG0122), additionally, the BLAST search [65] against E. coli K-12 DH10B proteome reveals the identity of P. putida GB-1 and S16 AlkA2 proteins with the E. coli AlkA at the level of 36 and 37%, respectively.

The motif files (Files S4 and S5) were generated with MEME tool [69] with E. coli K-12 DH10B ada, alkA, and aidB promoter consensus sequences used as inputs. These were subsequently used as inputs for the FIMO tool [70], allowing the search in File S3 database with P-value better than 0.01. Thus, the obtained output files (Files S6 and S7) were fused, the same sequences removed, and formatted for fasta file format (File S8). Subsequently, this file was used to generate phylogenetic tree with Geneious Tree Builder with the following parameters: Cost Matrix – Identity (1.0/0.0), Gap open penalty -12, Gap extension penalty -3, Alignment type – Global alignment, Genetic Distance Model – Tamura-Nei, Tree build Method – UPGMA. All the sequence alignments and tree manipulations were performed in Geneious 6.1.5 (Biomatters, http://www.geneious.com).

The borders of the consensus sequences in Ada regulon promoters responsible for Ada protein specific interaction were established according to ref [30]. . Additionally, the positions of -35 and -10 boxes for RNA polymerase in E. coli ada, alkA, and aidB promoters were retrieved from RegulonDB (http://regulondb.ccg.unam.mx) or predicted for P. putida alkA, aidB, and alkB promoters according to SoftBerry BPROM prediction tool (http://linux1.softberry.com).

Statistical analysis

Survival and mutagenesis experiments were repeated 4-10 times, each in duplicate, and standard deviation (± SD) was calculated. Statistically important differences were tested on the basis of Student t-test (P < 0.05, two-sided, implication of different variances). Counts were computed and graphs were constructed using SigmaPlot (Systat Software, San Jose, CA). Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4 were prepared with GIMP 2.8 image manipulation software.

Supporting Information

The fasta file of P. putida and E. coli alkyl damage glycosylases with Aag Representatives (family cd00540, NCBI).

(FASTA)

The fasta file of P. putida and E. coli acyl-CoA dehydrogenase sequences retrieved from AidB family cd01154 (NCBI).

(FASTA)

The fasta file of P. putida KT2440, F1, S16, GB-1, and W619 and E. coli K-12 DH10B, K-12 MG1655, B REL606, BW2952, CFT073, HS, O175:H7 EC4115, and SE11 strains of ada, alkA, aidB, and alkB promoter sequences (from -100 to -1 relative to ATG start codons).

(FASTA)

The MEME output file for E. coli K-12 DH10B ada, alkA, and aidB promoter consensus sequences used as input.

(TXT)

The MEME output file for P. putida KT2440, F1, and W619 alkA and KT2440, F1, GB-1, and GB-1 aidB promoter consensus sequences used as input.

(TXT)

The FIMO output search results with File S4 as motif file and File S3 as database input file.

(TXT)

The FIMO output search results with File S5 as motif file and File S3 as database input file.

(TXT)

The fasta file of FIMO outputs (Files S6 and S7) with the sequences redundant at 100% removed.

(FASTA)

Primers used in the study for the preparation of P. putida deletion strains.

(DOCX)

Primers used in the study for PpalkB (Pputup, Pputdn) and promoter sequences cloning (PpalkAH1, PpalkAdE; PpalkBH1, PpalkBdE; PpadauH1, PpadadnE; Ecadaru, Ecadard) or used for PpalkA promoter deletion/mutation (AalkAup, AalkAdn; BalkAup, BalkAdn; ABalkAup, ABalkAdn; AmalkAup, AmalkAdn; AAalkAup, AAalkAdn).

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Pawel Siedlecki for his helpful discussion on the analysis of promoter sequences.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by National Center of Science, Poland, grant number UMO-2012/05/B/NZ1/00693 to AS, DM, MW, and EG; by Estonian Science Foundation, grant number 9114 to MK, and by Estonian Ministry of Research Targeted Financing Project SF0180031s08 to MK. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Beranek DT (1990) Distribution of methyl and ethyl adducts following alkylation with monofunctional alkylating agents. Mutat Res 231: 11-30. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(90)90173-2. PubMed: 2195323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]