Abstract

The importance of tissue transglutaminase (TG2) in angiogenesis is unclear and contradictory. Here we show that inhibition of extracellular TG2 protein crosslinking or downregulation of TG2 expression leads to inhibition of angiogenesis in cell culture, the aorta ring assay and in vivo models. In a human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) co-culture model, inhibition of extracellular TG2 activity can halt the progression of angiogenesis, even when introduced after tubule formation has commenced and after addition of excess vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). In both cases, this leads to a significant reduction in tubule branching. Knockdown of TG2 by short hairpin (shRNA) results in inhibition of HUVEC migration and tubule formation, which can be restored by add back of wt TG2, but not by the transamidation-defective but GTP-binding mutant W241A. TG2 inhibition results in inhibition of fibronectin deposition in HUVEC monocultures with a parallel reduction in matrix-bound VEGFA, leading to a reduction in phosphorylated VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2) at Tyr1214 and its downstream effectors Akt and ERK1/2, and importantly its association with β1 integrin. We propose a mechanism for the involvement of matrix-bound VEGFA in angiogenesis that is dependent on extracellular TG2-related activity.

Keywords: tissue transglutaminase, angiogenesis, crosslinking, tubule and VEGF

Blood vessel formation, also known as angiogenesis, is well-regulated by a complex growth factor network, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF),1 fibroblast growth factor1 and platelet-derived growth factor.2 Physiological angiogenesis is essential to bring oxygen and nutrition to the organs during development, while pathological angiogenesis takes place in different organs and tissues, including eye (cornea and retina), muscle and joints and so on, among which tumour angiogenesis is probably the most widely reported. Strategies to inhibit the progression of pathological angiogenesis have therefore mainly been targeted towards these different key growth factors and their receptors or their downstream signalling molecules. Examples include anti-VEGF therapy using small inhibitors or monoclonal antibodies.3 Unfortunately, this approach has only shown limited success in tumour angiogenesis and vascular mimicry, with non-specificity and toxicity arising from the anti-VEGF treatments.4, 5, 6 As such, there is an urgency to identify other biomarkers and major factors involved in regulating angiogenesis, so that alternative therapeutic antagonists and inhibitors with more specificity and less side effects can be developed.

There have been a number of reports to suggest the importance of the multifunctional Ca2+-dependent protein-crosslinking enzyme tissue transglutaminase (TG2) in the angiogenic process.7 In the extracellular environment, TG2 can mediate both the deposition of the extracellular matrix (ECM) components, such as fibronectin (FN), and also act as a cell adhesion protein via its binding to cell surface syndecan-4 and β integrins.7, 8 However, even though research has been directed to studying the role of TG2 in angiogenesis, the actual mechanism of how this multifunctional enzyme functions in the angiogenic process is still not fully understood. Moreover, reports from different groups are in contradiction with one another as to the mechanism of action of TG2 and whether the enzyme is inhibitory or stimulatory. A recent study from Jones et al.9 demonstrated a role for TG2 in vascular mimicry, a special type of vasculogenesis undertaken by carcinoma cells with endothelial like cell properties,10 which can be independent of VEGF and often associated with highly aggressive tumours.6 In this work, using the bladder carcinoma ECV304, it was shown that the activity of TG2 was essential for the tubular formation by a process involving matrix deposition, actin cytoskeleton organisation and focal adhesion (FA) formation, which in turn regulate cell migration.9

Here we further study the role of TG2 in angiogenesis using a series of different models and show that the inhibition of TG2 activity by site-directed irreversible inhibitors or by downregulation of its expression by short hairpin (shRNA) prevents the development of angiogenesis in cell culture, the aorta ring assay and in vivo models. We describe how TG2 function is important in angiogenesis and propose that VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2) signalling mediated by matrix-bound VEGFA is dependent on a mechanism involving extracellular TG2-related activity.

Results

Inhibition of extracellular TG2 crosslinking activity blocks tubule formation in vitro and ex vivo models

Site-directed irreversible TG2 inhibitors, including R294, R283 and Z-DON, were used to block TG2 activity in both cell and tissue models of angiogenesis. R283 and Z-DON are cell-permeable, whereas R294 is impermeable to cells and acts extracellularly. R294 has greater specificity (IC50, 5 μM) for TG2 than for Factor XIIIa (IC50 >200 μM).11, 12 R283 has equal potency for both enzymes.13, 14 The commercial TG2 inhibitor Z-DON inhibits TG2 with high specificity, while displaying less effect on the TG1 and TG3 isoforms.15 None of the inhibitors showed any toxicity toward human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) or fibroblasts upto 750 μM during a 72-h culture period (Supplementary Figures 1a and 2).

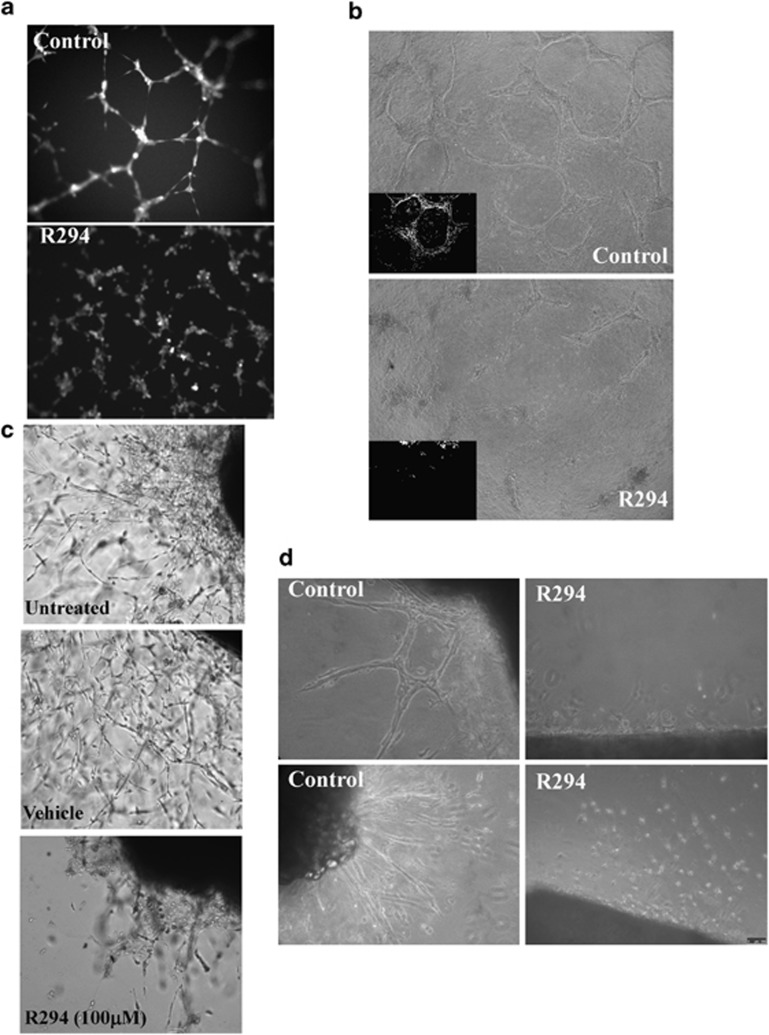

R294 was first applied to HUVECs seeded in Matrigel (Figure 1a), resulting in a reduced capacity of the HUVECs to align and form cord-like structures. A similar reduction in HUVEC tubule formation by R294 was also found in the HUVECs embedded in 3D collagen gels (Figure 1b). The effect of the TG2 inhibitor R294 on the aorta ring ex vivo model of angiogenesis was also undertaken. Explants were placed into either Matrigel or a collagen thin layer gel and outgrowth of vessel-like structures was monitored. TG2 inhibition by R294 led to inhibition of the tubule outgrowth from the embedded aorta in both the Matrigel and collagen (Figures 1c and d, and Supplementary Figure S3). In contrast in the DMSO vehicle control groups, outgrowth of well-formed endothelial tubule structures took place, which was confirmed by using fluorescence staining for the endothelial marker CD31, in the tubule structures (Supplementary Figure S4).

Figure 1.

Effect of TG2 inhibitor R294 on endothelial tubule formation. (a) Inhibition of endothelial cord formation on Matrigel by R294. Representative image from three separate experiments. HUVECs seeded at a concentration of 15 000 cells per well in 12-well plates containing Matrigel and induced to form tubule like structures in EGM complemented medium in the presence of 100 μM R294 or vehicle control (0.01% DMSO) for 6 h. Cells were labelled with 2 μM Calcein AM for 15 min and were photographed using 484 nm excitation and 520 nm emission filter on a fluorescent microscope. (b) Inhibitory effect of R294 on HUVEC in collagen 3D culture. HUVECs (1 × 105/well, in 48-well plates) were mixed with rat tail collagen solution (final concentration 1.5 mg/ml) with 50 μM TG2 inhibitor R294 or the vehicle control (0.01% DMSO) and allowed to gelify at 37 °C for 30 min. Endothelial culture medium in the presence or absence of 100 μM R294 or vehicle was added to the well. Following a 4-day culture period, representative images with and without R294 are shown using a bright-field microscope (n=3). (c and d) Endothelial vessel outgrowth from rat aorta ring in Matrigel or thin layer collagen. Rat aorta rings (n=4) were embedded in Matrigel (c) or a thin layer of rat tail collagen (d) and incubated with endothelial cell medium for 7 days in the presence of 100 μM R294 or vehicle (0.01% DMSO) as described in the Materials and Methods. The representative images were taken using a bright-field microscope

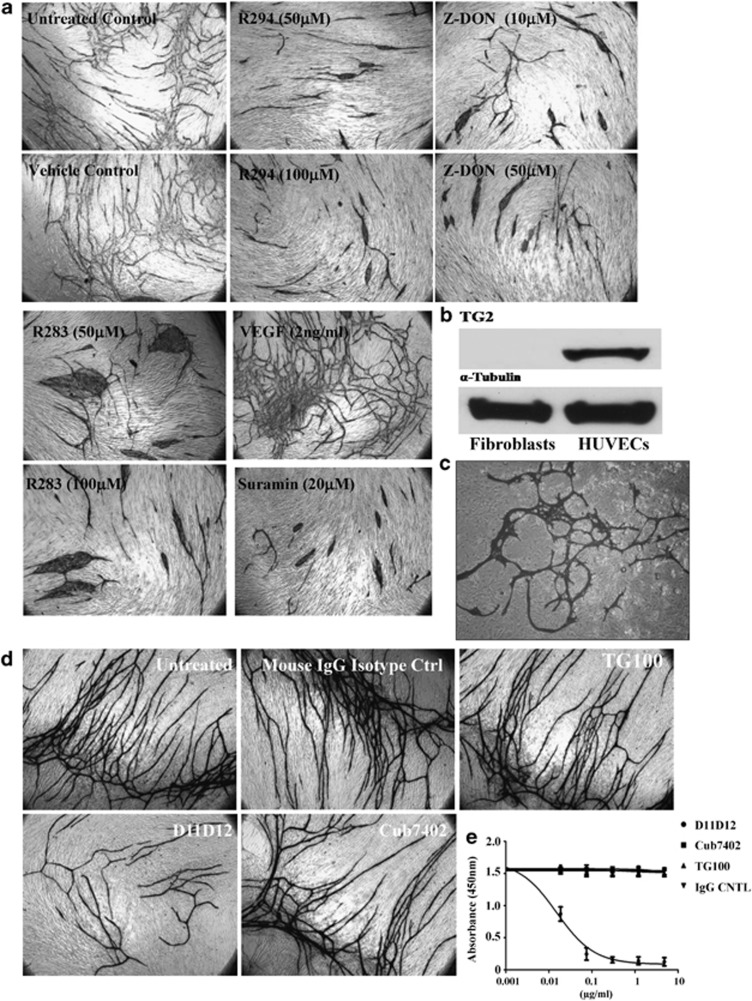

To extend our discovery for the involvement of TG2 during tubule formation, a co-culture model was used whereby HUVECs are seeded with human fibroblasts, resulting in HUVEC tubule formation over 14 days.16 As shown in Figure 2a, the addition of TG2 inhibitors led to a significant inhibition of tubule growth over a 14-day period (Supplementary Table S1). The ability of compounds to affect tubule formation, including the cell-impermeable inhibitor R294, suggests a prominent role for the TG2 at the cell surface or in the ECM.

Figure 2.

Effect of TG2 inhibition on endothelial tubule formation in fibroblasts and EC co-cultures. (a) After incubating the V2a AngioKit co-culture for 24 h, V2a Growth medium was introduced (day 1) in the absence or presence of either the irreversible inhibitors Z-DON, R294 or R283 at the concentrations shown, and replaced in fresh medium every other day for 12 days. Controls contained either complete growth media alone (untreated), or the respective inhibitor vehicle (DMSO, 0.01%). Suramin or VEGF was used for the negative and positive control, respectively. Cells were fixed in ethanol at day 12 and stained for CD31 antigen using an anti-mouse IgG secondary AP-conjugated antibody and visualised as described in the Materials and Methods. The tubule like structures were analysed by the TCS Cellworks AngioSys Image Analysis Software (ZHA-1800) (Supplementary Table S1), as described in the Materials and Methods. (b) The presence of TG2 in human fibroblasts and HUVECs. Western blotting was performed to detect the presence of TG2 in fibroblasts and HUVECs, separately. α-Tubulin was used as the equal loading control. (c) Co-culture of HUVEC and TG2−/− MEF. HUVECs were induced to undergo microtubule formation in the presence of TG2−/− fibroblasts using the growth media from the angiogenesis V2a Kit. Shown is the appearance of endothelial cell microtubules at day 14 revealed by immunostaining for CD31 antigen using anti-mouse IgG secondary alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated antibody and visualised as described in the Materials and Methods.(d) Effect of different TG2-specific antibodies on endothelial cell tubule formation in the co-culture assay. Culture medium was supplemented with either the mouse monoclonal TG2 activity neutralising antibody (D11D12, 0.1 μg/ml), the commercial anti-TG2 antibodies Cub7402 (0.5 μg/ml) or TG100 (0.5 μg/ml) added to the co-culture system from day 1 (24 h after seeding). Controls consisted of either untreated cultures or isotype-matched IgG. After 12 days, the tubule formation was analysed as described in (a) (see Supplementary Table S1). (e) The effect of the antibodies D11D12, Cub7402 and TG100 on the extracellular crosslinking activity of TG2 in the co-culture angiogenesis assay. Cells at day 9 were incubated with various concentrations of the antibodies or isotype-matched control for 1 h at 37 °C in a 96-well microplate. Following this pre-incubation period, biotinylated cadaverine incorporation was measured as described in the Materials and Methods. Data show mean value±S.D. after background correction (n=3) for assays that contained 10 mM EDTA

Previous data using the HUVEC co-culture assay indicated the majority of in situ TG2 activity was associated with fibrous structures around the endothelial cell tubules.14 Analysing the presence of the enzyme via western blotting revealed that TG2 is majorly present in the HUVECs, but not detectable in human fibroblasts (Figure 2b). Moreover, in a co-culture containing TG2-/-MEF cells with HUVECs, tubule like structures were still able to form (Figure 2c). TG2 and CD31 were found co-localised in the tubule like structures (Supplementary Figure S5), confirming that TG2 is predominantly in the endothelial cells and indicating that tubule formation is dependent on the TG2 present in the HUVECs.

To confirm the extracellular importance and specificity of TG2 in the formation of HUVEC tubules, co-cultures were incubated with the TG2-specific transamidating inactivating monoclonal antibody D11D12. Incubation with this antibody led to a significant reduction of tubule formation (around 50%) (Figure 2d, Supplementary Table S1) and a significant reduction in extracellular TG2 activity (Figure 2e). The other monoclonal antibodies Cub7402 and TG100 (which bind to TG2, but do not adversely affect transamination activity (Figure 2e)) had no significant effect on tubule growth (Figure 2d). The antibodies were shown to have no adverse effect on HUVEC growth (Supplementary Figure S1B).

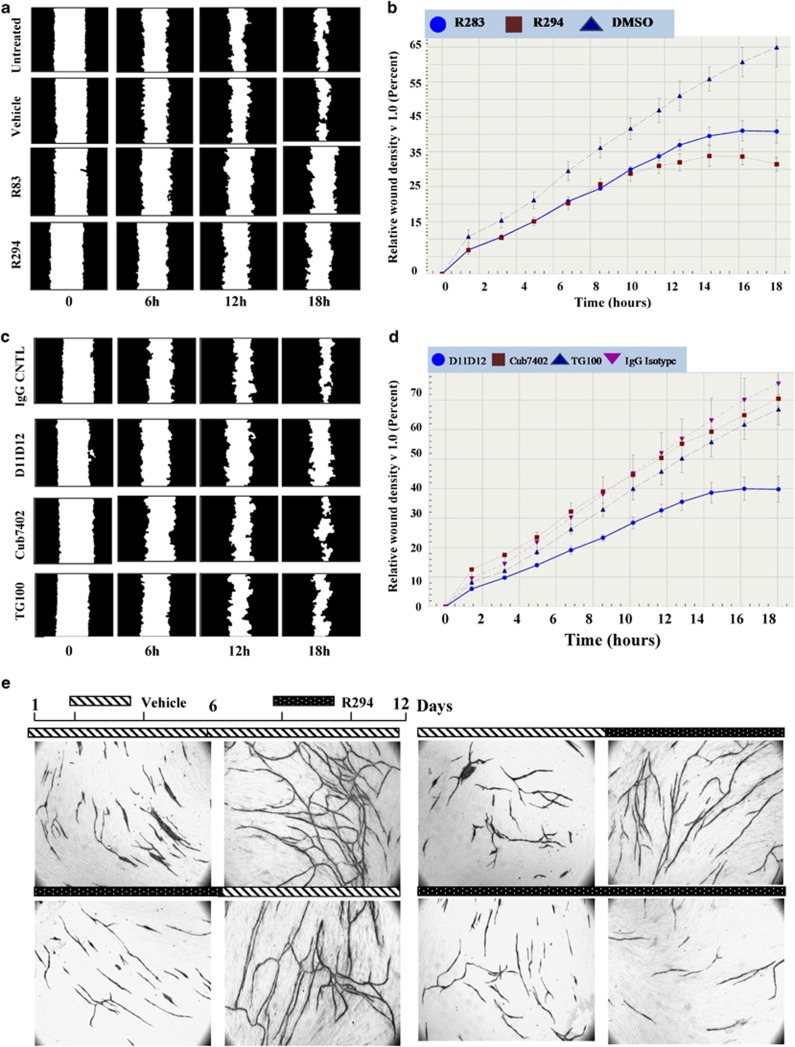

Inhibition of extracellular TG2 activity affects endothelial cell migration

As the migration of endothelial cells is important for tubule formation, the migratory response of endothelial cells to TG2 inhibitors and TG2-targeted antibodies was determined. A scratch-wound assay was performed on HUVEC monolayers cultured on FN pre-coated surfaces. Both R294- and R283-treated cells were unable to close the wound in a time frame comparable to that of untreated cells or cells that only received the inhibitor vehicle (Figures 3a and b, Supplementary Movies 1–4). Wound assays with added TG2-specific antibodies – Cub7402 and TG100 (which do not inhibit transamidation activity) – led to non-significant changes in the cells ability to close the wound. In contrast with the transamidation-inactivating antibody D11D12, wound closure was significantly slower (Figures 3c and d).

Figure 3.

Migration of HUVECs on fibronectin in the presence of either TG2-specific inhibitors or specific antibodies. (a) HUVECs were seeded onto graduated 96-well plates pre-coated with fibronectin (5 μg/ml) and allowed to reach 90–95% confluence in the presence of EGM media. Following the different treatments, as indicated in the figure, cells were stimulated to migrate in the absence or presence of the TG2 inhibitor R294 (100 μM) and R283 (100 μM), with a net scratch using a multi-well wound healing devise to prevent direct damage to the coated surface. Cell migration was continuously monitored over a period of 18 h in the ESSEN IncuCyte instrument as shown in the graph below. The masked images are representative of the cell migration towards the wounded area at different time intervals, as indicated. (c) The same experiment as in (a) except the inactivating antibody (D11D12, 0.1 μg/ml) or the commercial anti-TG2 antibody Cub7402 or TG100 (0.5 μg/ml) or their isotype controls was added to the culture medium. (b and d) Cell migration was continuously monitored over a period of 18 h in the ESSEN IncuCyte instrument and the cell migration was quantified as the density of the wounded area over the time, using the ESSEN IncuCyte software. (e) Staged effect of TG2 inhibition on tubule formation in the co-culture assay. HUVEC co-cultures cultured for 12 days after adding of V2a Growth medium and treated with inhibitor vehicle (0.01% DMSO) used as the control (upper panels) or TG2 inhibitor R294. Treatments consisted of the addition of the R294 (50 μM) from day 1 to 12, added with fresh medium every other day, or addition of the inhibitor only during the first stage of the co-culture (from day 1 to 6), or only during the late stage (from day 6 to 12). Tubule formation was visualised and analysed as described in Figure 3 (Supplementary Table S1)

Inhibition of TG2 can slow down growth of newly established tubules

To examine whether the inhibition of extracellular TG2 has a reversible or irreversible effect on tubule formation, staged addition of inhibitor to the co-culture was undertaken. Exposure to R294 during the first 6 days resulted in cells acquiring a similar morphology to the non-inhibited co-cultures when the inhibitor was removed and cells cultured for a further 6 days without inhibitor. However, there was a significantly lower amount (∼33%) of tubular junctions (Figure 3e and Supplementary Table S2). The withdrawal of R294 at day 6 resulted in a partial recovery of the total anastomosis reached at day 12, when compared with the untreated cells, with tubule formation being significantly lower than that observed in untreated co-cultures (∼25%). When addition of R294 was limited to the late stage of the co-culture (from day 6 to 12), a reduction (∼20%) in the total area of tubules and a reduction (∼30%) in tubule junctions was found. Both staged treatments led to a significant reduction in the number of tubule junctions, suggesting that the inhibitor may be destabilising endothelial cell outgrowth at the junction points (Figure 3e and Supplementary Table S2).

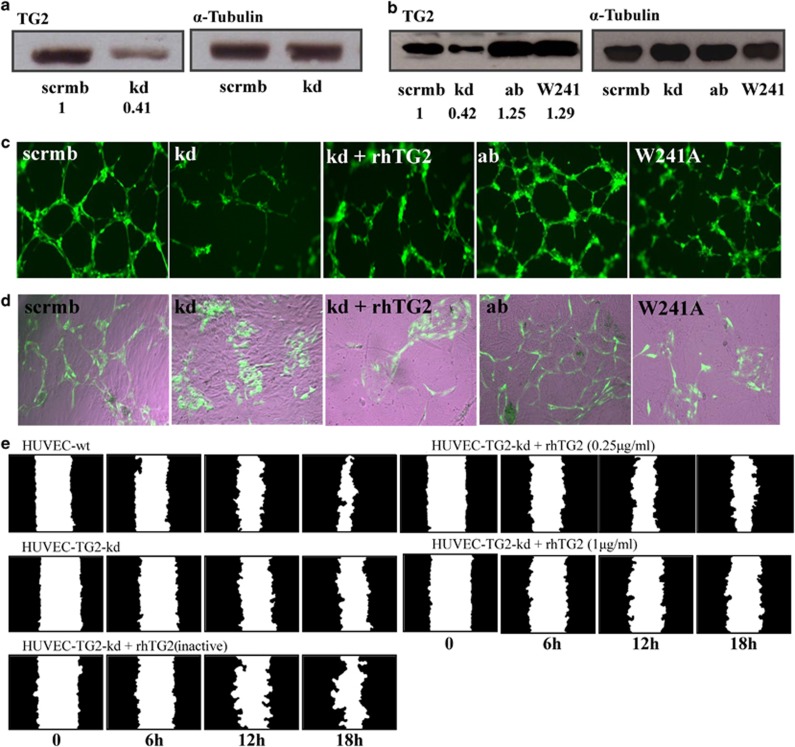

Decreased tubule formation and migration after TG2 knockdown in HUVECs

TG2 was downregulated using viral transduction with shRNA (knockdown; kd), resulting in a 58.5±0.5% decrease in the HUVEC TG2 protein (Figure 4a) and a comparable reduction in transamidation activity, when compared with control cells containing scrambled shRNA (scrmb) (Supplementary Figure S6a). Restoring the expression of the active enzyme (ab) and the W241A mutant (W241) into the TG2 kd cells using lentiviral particles resulted in the high expression of the target protein (Figure 4b). In both Matrigel cord formation and the EC-fibroblast co-cultures, the TG2kd cells demonstrated reduced tubule formation (Figures 4c and d, Supplementary Table S3). This reduced angiogenesis caused by reduced expression of TG2 could not be reversed by addition of exogenous active recombinant human (rh) TG2, but was nearly restored when HUVEC-TG2kd cells were virally transduced with the active form of the isoenzyme (ab) (Figures 4c and d). The W241A mutant protein, which does not have protein-crosslinking activity but intact GTP-binding function, failed to compensate the kd of the active enzyme, suggesting that the transamidating activity of TG2, but not the GTP-binding activity, is essential during tubule formation.

Figure 4.

Manipulating TG2 expression in HUVECs affects tubule formation and cell migration. (a) Western blot analysis of TG2 expression levels in lysates of HUVEC-TG2wt and HUVEC-TG2kd (HUVECs transduced with TG2 scrambled or targeted shRNA) and (b) TG2 add back, either the active wt enzyme or the W241A mutant in the kd HUVECs. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control and ratio of band intensity for TG2 is shown below taken from three separate experiments. (c and d) Tubule formation of HUVECs expressing wt TG2, TG2kd or the TG2 mutants after reintroduction into the TG2kd cells. HUVEC-TG2wt, -TG2kd, -TG2ab, -TG2kd/W241A or TG2kd in the presence of exogenously added rhTG2 (0.25 μg/ml), induced to form tubule structures on Matrigel in complete EGM-2 medium as described in the Materials and Methods, for 6 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Cells (GFP, green) were photographed using an epifluorescent microscope as described in the Materials and Methods. (d) HUVECs as described in (c) (GFP, green), co-cultured with human dermal fibroblast as feeder cells in the enriched EGM medium for 12 days as described in the Materials and Methods. Images were taken as in (c). The tubule like structures shown were analysed by the TCS Cellworks AngioSys Image Analysis Software (ZHA-1800) (Supplementary Table S3), as described in the Materials and Methods using a bright-field microscope. (e) Scratch assay for migration of HUVEC-TG2wts and HUVEC-TG2kd on FN, in the absence or presence of exogenously added rhTG2 at different concentrations, analysed as in Figure 3

Reducing TG2 expression in HUVECs also resulted in the reduced mobility of cells on FN (Figure 4e and Supplementary Figure S7), but had no effect on cell proliferation (Supplementary Figure S6b), confirming the importance of TG2 in HUVEC migration. Interestingly, the reduced mobility of HUVEC-TG2kd was not improved by the exogenous addition of either the inactive or the active TG2 isoenzyme. Moreover, the active enzyme becomes inhibitory at higher concentration (1 μg/ml), which agrees with previously published results for its effect on tubule formation.14

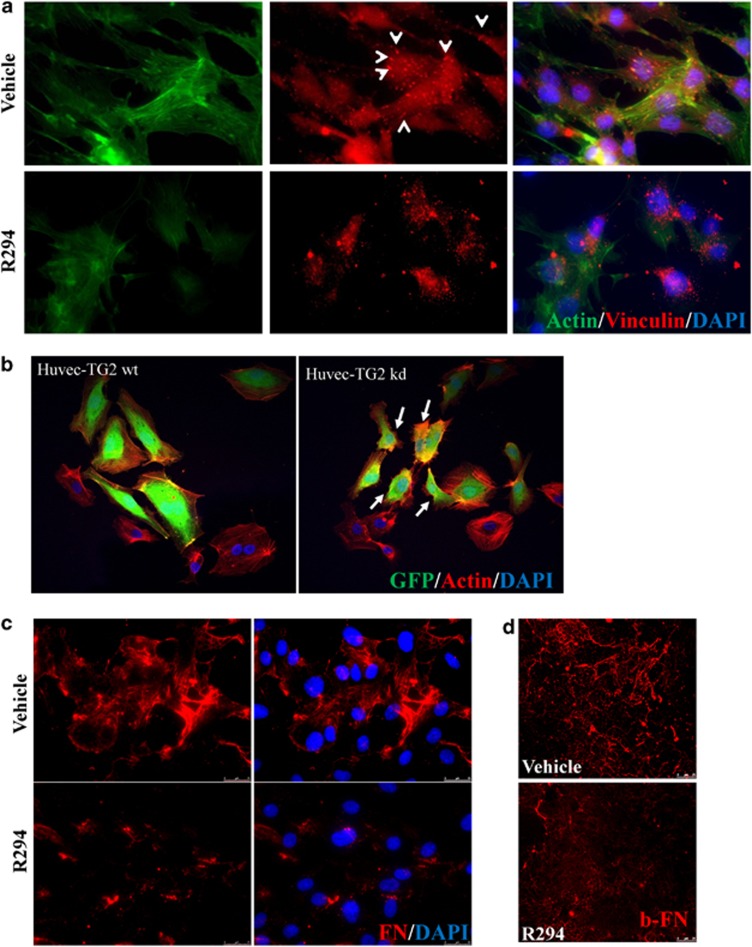

The inhibition of TG2 activity results in a disrupted HUVEC morphology and FN deposition

The cell mobility is regulated by the formation of an intracellular actin cytoskeleton and FA formation.17 Figure 5a shows that R294 treatment disrupted the actin cytoskeleton and FAs in the HUVECs. This result was further confirmed in the TG2 kd cells (Figure 5b), in which low expression of intracellular TG2 resulted in a reduced spreading ability of cells on FN with small disorganised actin fibres present in 83±4% of the shRNA-GFP containing cells. As FA is required during ECM FN fibril deposition, to confirm the importance of HUVEC TG2 in FN deposition, isolated HUVEC cells were cultured for 48 h in the presence and absence of TG2 inhibitor R294. Measurement of the whole population of FN deposited by immunofluorescence showed the deposition of dense FN fibrils in R294-treated cells was greatly reduced (Figure 5c). This was confirmed by the inhibition of the deposition of exogenous biotin-labelled FN by R294 (Figures 5d and 6a).

Figure 5.

The effect of TG2 inhibition of HUVEC morphology and FN deposition. (a) Representative images (n=3) from monolayer HUVECs treated with 100 μM R294 or vehicle for 48 h and the actin cytoskeleton (green) and FAs (vinculin, red, as pointed out by the arrow heads) staining was performed and visualised as described in the Materials and Methods. Nuclear counterstaining of cells used 4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue). (b) Cytoskeletal organisation of HUVEC-TG2wt and HUVEC-TG2kd. Morphological comparison of the spreading ability of HUVEC-TG2wt and HUVEC-TG2kd, when assessed for actin stress fibre formation. HUVECs expressing the viral constructs (GFP, green colour) were plated on FN-coated cover slips in the presence of EGM complemented medium. TRITC-labelled phalloidin (red) was used to stain actin fibres and then examined by confocal microscopy as described in the Materials and Methods. (c) The effect of TG2 on ECM FN deposition by HUVECs. Representative image from HUVECs treated with 100 μM TG2 inhibitor R294 or vehicle for 48 h before immunostaining for extracellular FN as described in the Materials and Methods. Cells were counter stained with DAPI. The ECM FN was visualised using fluorescence microscopy as described in the Materials and Methods. (d) The inhibition of biotin-labelled FN deposition by R294 in HUVECs. Biotin-labelled FN 50 nM was added into HUVEC mono-cell layer as described in the Materials and Methods with 100 μM R294 or with the vehicle control. After a 48-h incubation period, the presence of biotin-labelled FN was detected using Cy5-conjugated Strep-Avidin and the fluorescence signal was visualised via confocal microscopy. Bar, 25 μm

Figure 6.

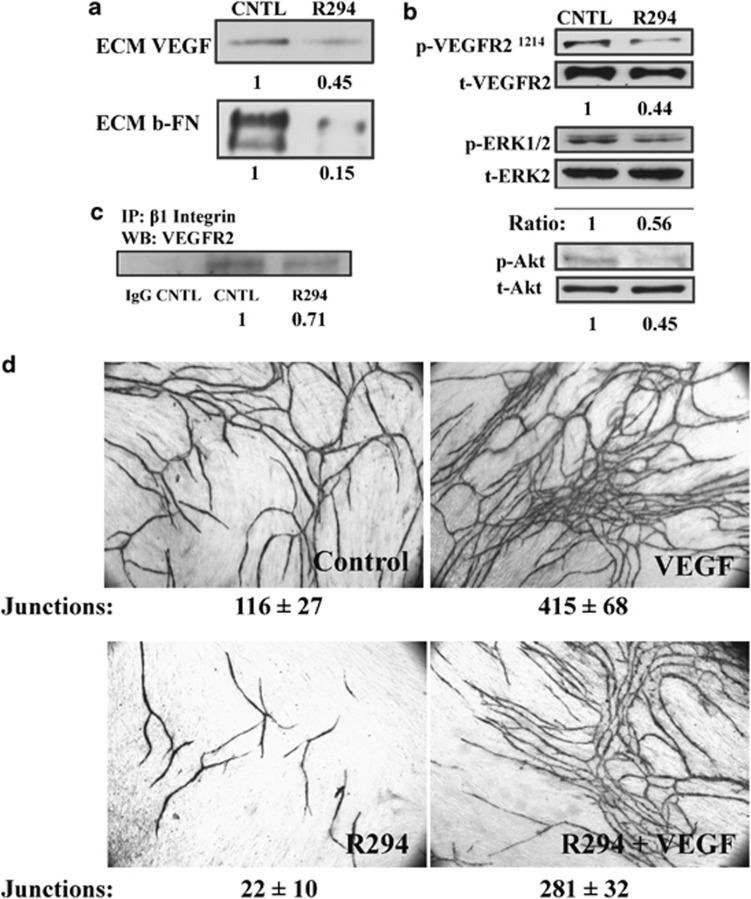

The effect of TG2 inhibition on VEGF deposition and signalling. (a) Reduction of matrix VEGF and FN by inhibition of TG2. HUVECs mono-cell culture treated with 100 μM R294 or 0.01% DMSO vehicle control for 48 h. The ECM fractions from HUVECs culture were collected and western blotted for VEGF, using a specific anti-VEGF antibody as described in the Materials and Methods. The deposition of biotin-labelled FN in the ECM after western blotting was detected by using HRP-conjugated Extr-Avidin and the ratio of the bands taken from three separate experiments is as shown.(b) The phosphorylation of VEGFR2, ERK1/2 and Akt in HUVECs is regulated by TG2. HUVECs mono-cell culture treated with R294 or DMSO vehicle were isolated after 48 h growth and the cell lysates used in western blotting to detect the phosphorylated VEGFR2 at Tyr1214, ERK1/2 (p-ERK1/2) and Akt (p-Akt). Total VEGFR2, ERK1/2 and Akt was used as the loading control as described in the Materials and Methods. The ratio of the bands taken from three separate experiments is as shown. (c) The inhibitory effect of R294 on the direct interaction between VEGFR2 and β1 integrin via co-immunoprecipitation. Anti-β1 integrin antibody was used to pull down the β1 integrin immuno-complex in the HUVECs with or without R294 treatment for 48 h, the presence of VEGFR2 was detected via western blotting by using anti-VEGFR2 antibody, while the rabbit IgG was used as the negative control. The ratio of the bands taken from three separate experiments. (d) Effect of R294 on VEGF-stimulated angiogenesis. Co-cultures were grown for 12 days either untreated, or in the presence of VEGF (2 ng/ml) or R294 (100 μM), or VEGF (2 ng/ml) plus R294 (100 μM). Shown is the appearance of endothelial cell tubes at day 12 revealed by the immunostaining for CD31, which was analysed by image analysis as in Figure 2 (Supplementary Table S1)

Inhibition of TG2 activity leads to a reduction in matrix-bound VEGF and inhibition of its downstream signalling pathway

Matrix-bound VEGF is reported to be more important than localised VEGF secretion for induction of endothelial cell angiogenesis and this process is highly sensitive to the abundance of deposited FN.18 In parallel experiments, measurement of matrix-bound VEGF by western blotting showed it to be greatly reduced by TG2 inhibition in cell free matrix extracts, accompanied by a reduction ECM FN (Figure 6a).

Once deposited into the ECM, VEGF can trigger the activation of VEGFR2. Western blotting using a specific antibody to phosphorylated-Tyr1214 VEGFR2 in HUVECs indicated that a significant reduction in the phosphorylation at this site was found in R294-treated HUVECs, compared with the vehicle control samples (Figure 6b). In addition, the reduced levels of matrix-bound VEGF and phosphorylated-Tyr1214 VEGFR2 in the TG2 inhibited cells correlated with significantly reduced levels of phosphorylated Akt and ERK1/2, the downstream effector molecules of matrix-bound VEGF signalling (Figure 6b). Interestingly, R294 also reduced the direct interaction between VEGFR2 and β1 integrin in the HUVEC cultures (Figure 6c), further confirming the involvement of TG2 in VEGFR2-related signalling.

Our hypothesis for the relationship between TG2 and VEGF was further tested in the co-culture model where increased VEGF is added to the medium. The combination of increased VEGF with R294 resulted in less tubules of longer length and with less junctions with respect to the tubules formed with VEGF alone. When quantified, there is a significant (∼30%) less junctions and a significant (∼30%) reduction in tubules formed in co-cultures receiving R294, compared with increased VEGF-treated co-cultures alone (Figure 6d and Supplementary Table S1).

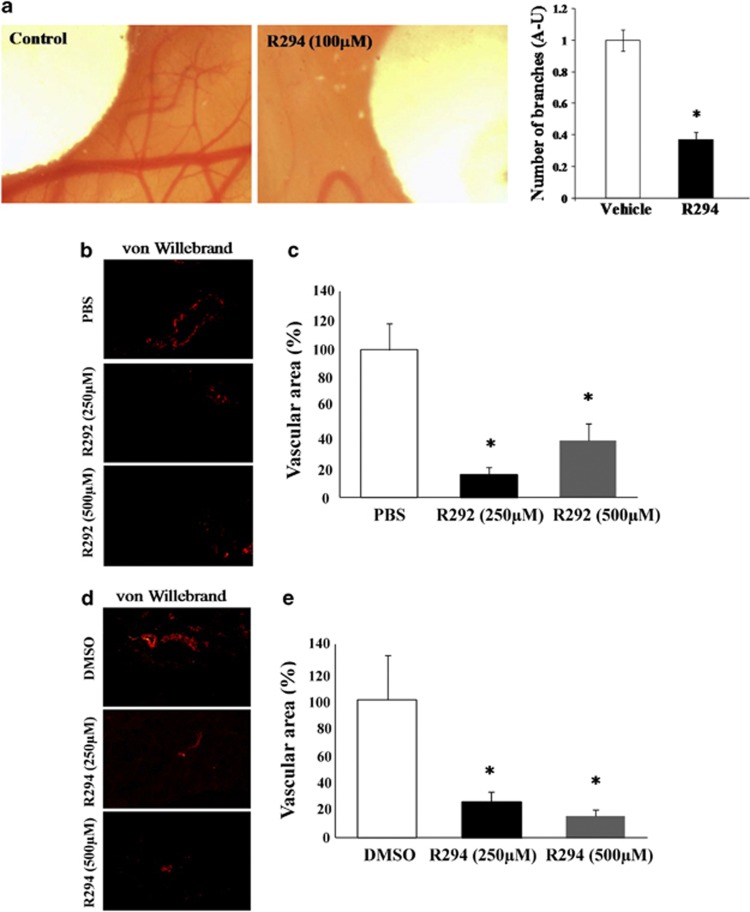

Inhibition of TG2 in two separate in vivo models leads to reduced angiogenesis

The chick allantoic membrane (CAM) model of angiogenesis was used as the first in vivo model to study the involvement of TG2 in angiogenesis. Incubation of the TG2 inhibitor R294 on the vascular area around the chick embryo at 100 μM led to a significant reduction in angiogenesis compared with the adjacent areas treated with the DMSO vehicle control (Figure 7a). In the second model, Matrigel containing 10 μg/kg of erythropoietin (EPO) to induce angiogenesis as well as inhibitors for TG2 (at 250 μM or 500 μM) or their respective vehicle controls (PBS or DMSO) were injected subcutaneously into the rear quarter of mice. After 8 days, the Matrigel was excised and analysed for vasculogenesis following staining with von Willebrand factor for vessel formation and quantified using ImageJ software (Bethesda, MD, USA). Both R292 (Figures 7b and c) and R294 (Figures 7d and e), which show increased specificity for TG2 over Factor XIIIa and which act extracellularly, significantly inhibited blood vessel formation in the Matrigel plug. No significant difference between the DMSO and the PBS control treatments was found.

Figure 7.

(a) Effect of TG2 inhibitor R294 on angiogenesis using the in vivo CAM assay. Chick embryo after 6 days of growth in the presence of R294 at100 μM or vehicle (0.01% DMSO) applied on disks in the same egg, as described in the Material and Methods. The accompanying histogram represents quantification of the vascular branches in presence or absence of the inhibitor R294. Bars represent the mean number of vascular branches in arbitrary units (AU)±S.D. (n=5 per group). Quantification was assisted by computer assisted analysis using ImageJ. *P<0.05.indicates difference from vehicle control (b–e). The effect of TG2 inhibition on in vivo angiogenesis in a mice Matrigel plug model. (b and d) Show the immunostaining of blood vessels using Von Willebrand as the angiogenesis marker in the presence of TG2 inhibitors R292 (b) and R294 (d) at the concentrations of 250 μM and 500 μM. The area of the blood vessels was quantified using Image J software and expressed as mean value±S.D. (n=5). (c and e) PBS and DMSO (0.01%) were used at the vehicle controls treatments for TG2 inhibitors R292 and R294, respectively. *P<0.05 indicates difference from vehicle control

Discussion

TG2 is reported to have both pro- and anti-angiogenic effects. Haroon et al.19 using a window flap model showed that addition of exogenous TG2 inhibited tumour growth by a mechanism involving collagen deposition and inhibition of tumour angiogenesis. Jones et al.14 also demonstrated that increased TG2 led to inhibition of angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo and inhibition of tumour progression by crosslinking the surrounding ECM.14 More recently, Martucciello et al.20 showed that the anti-angiogenic effects of TG2-targeted coeliac antibodies were due to the stimulation of TG2 activity.

Reports also suggest that TG2 is downregulated in endothelial cells undergoing capillary morphogenesis,21 while Greenberg and colleagues19 demonstrated that TG2 was pro-angiogenic after finding that its addition to a window flap model of dermal wounding promoted angiogenesis. The pro-angiogenic effect of TG2 has also been shown through its binding to endostatin in a cation-dependent manner, which under hypoxic conditions leads to stimulation of angiogenesis.22

In this study using HUVECs plated onto Matrigel and submerged in collagen, we first demonstrate that growth of the tubule like structures is reduced by the cell impermeable irreversible TG2 inhibitor R294,12 which preferentially targets TG2 over Factor XIIIa,11 the other TG that might be present in culture serum. Importantly, we also show that this TG2 inhibitor blocks tubule formation in aorta rings embedded either in either Matrigel or collagen. To explore TG2 involvement in angiogenesis further, we next used the well-established co-culture model whereby dermal human fibroblast are cultured over 12–14 days with HUVEC cells resulting in highly branched tubule formation.16 We show that a number of TG2 inhibitors block tubule formation and that the specific TG2-transamidating activity-inactivating antibody D11D12 is also inhibitory, confirming that the major role of TG2 is extracellular. Using HUVECs, we also demonstrate that one of TG2s extracellular roles in angiogenesis is in endothelial cell migration as this could be reduced when HUVEC cells were allowed to migrate on FN in the presence of either small molecule TG2 inhibitors or the inactivating TG2 antibody. This result was further confirmed using TG2 shRNA where only reconstitution into the cells of the wt TG2, but not inactive TG2, restored the migratory ability of cells.

One of the most important tasks in blocking angiogenesis is halting the growth of existing blood vessels and prohibiting new blood vessels from occurring. We demonstrate that TG2 inhibition slows down tubule formation even after 6 days of culture with a significant reduction in both the total area of tubules formed and of particular note the number of junctions established, resulting in longer tubules without junctions.

Confirmation that TG2 is the target enzyme was shown using knockdown of TG2 expression in HUVECs by shRNA. In both the co-culture and Matrigel models, HUVECs lost their ability to form tubule/cord-like structures. Loss of TG2 could not be compensated by add back of the active exogenous enzyme into the culture system, suggesting a regulated export of TG2 to the cell surface and binding to its cell surface-binding partners, such as syndecan-4 and FN, in order for it to function appropriately.8, 23, 24 In support of this adding back of TG2 by viral transduction, unlike the exogenous addition of TG2, restored the ability of HUVECs transduced with TG2 shRNA to form tubules. Downregulation of TG2 could not be compensated in a comparable manner with the mutant (W241A) form of the enzyme, which has impaired transamidating activity but GTP-binding activity, indicating that TG2 protein-crosslinking activity, but not GTP-binding activity, is required in endothelial tubule formation. The effect of TG2 shRNA on angiogenesis raised the question why TG2 knockout animals show no large phenotype changes compared with the wild-type (wt) animals.25 A series of articles from different groups demonstrated that a compensatory mechanism is taking place in TG2 knockout mice. In a recent study it was shown that there is a tissue-specific mechanism taking place by other TGs to compensate the loss of the TG2.26 Moreover, it has been reported that in TG2 knockout macrophages, increased expression of β3 integrins was found.27 These observations may therefore provide a valid explanation for the phenotype found in TG2 knockout animals.

We next turned our attention to the extracellular crosslinking roles of TG2 that might account for our observations. In T24/38 (ECV304) cells, we demonstrated that TG2 inhibitors blocked both cell migration and FN deposition, both of which were key to formation of tubular structures.9 The importance of TG2 crosslinking in FN deposition has been reported,7, 8 whereas the major role for TG2 in cell adhesion is generally related to its non-transamidating roles via binding to cell surface syndecan-424 and β1 and 3 integrins.28 The crosslinking activity of TG2 is essential in ECM deposition and stabilisation, both of which are necessary for cell migration. However, FN deposition in endothelial cells is also reported to be important for the binding and amplification of the activity of the angiogenic growth factor VEGF.29 VEGFR2 activation can be mediated by VEGF when in association with matrix proteins, and importantly this activation is likely be relevant to the establishment of the tip cell phenotype during the formation of a vascular sprout.30 We show that inhibition of TG2 transamidation activity led to reduced levels of FN deposition in HUVECs and in parallel with this, a reduced level of matrix-bound VEGF was detectable in these cells, when TG2 was inhibited with R294. This may account for the observed inhibition of tubule junctions and tubule formation by R294 even in the presence of excess VEGF. It has been reported that once deposited into the ECM, VEGF binds to its receptor VEGFR2, which can trigger the phosphorylation of VEGFR2 at Tyr1214 the activation of Akt and the activation of ERK1/2, important downstream signalling events, which require association of VEGFR2 with β1 integrin.30 Here we show that the reduction of ECM-bound VEGF by the TG2 inhibition reduces the phosphorylation of VEGFR2 at Tyr1214, the phosphorylation of Akt and the activation of ERK1/2. Importantly, TG2 inhibition also reduces the association of VEGFR2 with β1 integrin. One of the major effects of this signalling transduction and association of VEGFR2 with β1 integrin is to regulate cell migration by stimulating FA formation,30, 31 thus explaining our observation of reduced migration, reduced actin cytoskeleton formation and FA assembly in TG2 inhibited or TG2 downregulated HUVECs.

To extend our observations for the importance of TG2 in angiogenesis, we studied the effects of TG2 inhibition in two in vivo models – one observing vessel growth in the CAM assay and the other using the degree of vascular growth into a subcutaneously implanted Matrigel plug. TG2 inhibition using cell impermeable inhibitors led to a significant reduction in vascular growth in these two in vivo models. To sum up, our data indicate that endothelial TG2 may be a key factor in the angiogenic process. Importantly, its function is dependent on protein crosslinking directed to the extracellular space. This crosslinking function of TG2 is in part exerted through its effect on ECM/FN deposition, which in turn facilitates the deposition of matrix-bound VEGF and activation of VEGFR2 signalling. Inhibition of TG2 activity therefore ultimately leads to a reduction in VEGFR2 signalling leading to the inhibition of angiogenesis. Importantly, these inhibitor studies undertaken both in vitro and in vivo suggest that inhibition of TG2 could be a potential therapeutic target in the treatment of angiogenic pathologies.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and antibodies

The general reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Dorset, UK), unless stated below. Recombinant human TG2 (rhTG2), Z-DON-Val-Pro-Leu-OMe (Z-DON) and biotinylated cadaverine (BTC) were from Zedira (Carmstadt, Germany). The monoclonal TG2 activity neutralising antibody D11D12 (patent filing GB1209096.5, May 2012) was a kind gift of Dr. Tim Johnson (Sheffield University, UK). The mouse IgM anti-fibroblast surface protein antibody 1B1032 was a kind gift of Dr. Lindsay Marshall (Aston University, UK). The TG2 inhibitors 1, 3-dimethyl-2-imidazolium derivative R283 (Freund et al.13) and the peptidic TG2 inhibitors R294 and R292 were synthesised at Aston University.12 The antibodies used in this work were listed in Supplementary Table S4.

Cell lines

HUVECs (Promocell, Heidelberg, Germany) were cultured in endothelial growth medium (EGM) containing endothelial cell basal medium, 2% FBS, hydrocortisone, bFGF, VEGF, hEGF, ascorbic acid, R3-IGF, heparin and GA-100 (Lonza, Verviers, Belgium). Human dermal foreskin fibroblasts were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS. HEK/293TN cells (ATCC) were cultured in DMEM/F12 with 10% Fetalclone II and 2 mM L-glutamine. Co-cultures of virally infected HUVECs and human fibroblasts were cultured according to Bishop et al.16 to optimise tubule growth. TG2−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were a kind gift of Dr. Gerry Melino (University of Rome, Tor Vergata, Italy) and cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 1% non-essential amino acids and 2 mM L-glutamine.

Lentiviral constructs

The GFP-tagged lentiviral vectors including TG2 shRNA, scrambled shRNA, wt TG2, the W241A mutant TG2 were previously described.33 For the ‘add-back' experiments, the conserve mutation of wt TG2 and the W241A mutant TG2 constructs were generated by using the Stratagene QuickChange II XL, to avoid the effect of the shRNA.

Forward: 5′-GAT CCA GGG TGA CAA GAG TGA AAT GAT TTG GAA CTT CCA CTG CTG GGT GG-3′

Reverse: 5′-CCA CCC AGC AGT GGA AGT TCC AAA TCA TTT CAC TCT TGT CAC CCT GGA TC-3′

Production of lentiviral particles and infection of HUVECs

HEK-293TN were grown to 50% confluency in DMEM/F12 with 10% Fetalclone II in 150 mm culture dishes. Cells were transfected with the following viral vectors using Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Paisley, UK). Before transfection, the medium was changed to DMEM/F12 with 2% Fetalclone II. The ratio of pPAX, VSV-G and target vector for the transfection was 9 μg : 4.5 μg : 6 μg. The cells were then placed in a 33 °C incubator and after a 48-h incubation, the medium containing the viral particles was filtered through a 0.2-μM PES syringe filter and aliquoted. The aliquots were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at 80 °C until use.

HUVECs were transduced with the viral particles for 5–6 days to allow for expression of the constructs. The media was half-replaced with fresh media every 3 days. Expression of the constructs was confirmed by fluorescence microscopy or western blotting.

Angiogenesis assay using a V2a Angiokit angiogenesis co-culture system

The V2a AngioKit assay a pre-frozen form of the AngioKit assay (TCS Cellworks, Buckingham, UK) was used to study tubule formation in co-cultures of HUVECs and primary human fibroblasts.16 Following seeding, medium was replaced at day 2 by fresh growth medium and changed every 2 days over 9–14 days. At day 2, treatments were introduced to the cells as further described in the figures and figure legends. To visualise the tubule structures, cells were fixed in cold ethanol (70%) at room temperature for 30 min and stained with the anti-human CD31 primary antibody for 1 h at 37 °C and detected using the goat anti-mouse IgG alkaline phosphatise (ALP)-conjugate secondary antibody. Suramin, an inhibitor of angiogenesis, was used as the negative control. Increased addition of VEGF was used as the positive control as supplied by the manufacture. Tubules were quantified by ELISA using ALP soluble substrate p-nitrophenol phosphate. Tubules were finally stained using BCIP/NBT substrate for 15–20 min at 37 °C. The images were photographed with a × 4 objective using bright-field microscopy (Nikon, Surrey, UK) and tubule formation quantified using the TCS Cellworks AngioSys Image Analysis Software (ZHA-1800). Addition of suramin, an inhibitor of angiogenesis, and extra VEGF both supplied by the manufacturer were used as the negative and positive controls, respectively.

Matrigel endothelial cord formation assay

Phenol red-free basement membrane Matrigel (BD, Oxford, UK) with reduced grown factors was defrosted at 4 °C and used to coat 12-well plates, 100 μl/well. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min to allow the basement membrane to form a thin layer of gel. HUVECs, wt or cells transduced with lentiviral particles (1.5 × 105 in complete EGM medium), were plated in the matrigel-coated well and incubated with or without further treatment. After incubation, HUVECs were labelled with 2 μM Calcein AM for 15 min and photographed using a fluorescent inverted microscope fitted with a × 10 objective.

HUVEC 3D culture models

Well-established 3D culture models34 were used in the angiogenesis study with small modifications. In all, 1 × 105/well of HUVEC cells in endothelial cell basal medium (ECBM) were re-suspended in 50 μl collagen I (to reach a final concentration of 2.5 mg/ml) and then added to 96-well plates. After forming the gels by incubation at 37 °C, ECBM containing 10 ng/ml of VEGF was added to the wells with or without TG2 inhibitor R294 at a concentration of 100 μM, while DMSO was used as the vehicle control treatment. Fresh medium was replaced every day during the 7-day culture period. The images were taken using a bright-field microscope fitted with a × 10 objective.

Toxicity assay

The cytotoxic effect of the in-house inhibitors was evaluated using the Cell Proliferation Kit II (XTT) (Roche, West Sussex, UK) as described previously.35

In situ ECM TG2 activity assay

The HUVEC co-culture was cultured for 9 days, media was removed and cells incubated in serum-free EGM medium containing various concentrations of the antibodies D11D12, TG100 (Thermo, Loughborough, UK), Cub7402 (Thermo) or the corresponding isotype-matched control for 1 h at 37 °C. Subsequently, 100 μM biotin-cadaverine and 1 mM DTT was added to cells for an additional 2 h at 37 °C. A 10 mM EDTA containing treatment was used as the negative control. The reaction was stopped by adding 2 mM EDTA in PBS, pH 7.4 and the cells lifted from the ECM using 0.1% (w/v) deoxycholate in PBS (pH 7.4) containing 2 mM EDTA. The incorporated biotin-cadaverine was revealed using streptavidin-HRP at 37 °C for 1 h and the signal detected using OPD substrate.

Aorta ring assay

Four- to six–week-old female Swiss rats were euthanised by carbon dioxide and the aorta was removed. Aortas were cleaned and divided in two pieces and placed onto 100 μl of gelled Matrigel in 24-well plates then covered with another 100 μl of Matrigel. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 20 min before addition of culture medium, EGM-2 containing 50 μM or 100 μM of the TG2 inhibitor R294, or vehicle control (0.01% DMSO) or PBS. Aortas were cultured for 8 days and every 48 h media was replaced with fresh medium containing the different treatments. At the end of this period, pictures of the vascular areas around the aorta were taken in a random manner using a bright-field microscope fitted with × 10 (matrigel) or × 20 (collagen) objective. Maximum outgrowth and vascular density was analysed in five random fields and the pixel area measured in every field using ImageJ software. All data were normalised using the control group.

For 3D work, the method of Zhu et al.36 was followed 4–6-week-old female Swiss rats were euthanised by carbon dioxide and the aorta was removed. Aortas were cleaned and divided into pieces and placed into 24-well plates 25 μl of rat tail collagen I solution was placed onto the aorta ring so it formed a ∼8-mm thin disc. After forming gels at 37 °C for 5 min, 300 μl of serum-free ECBM containing 10 ng/ml VEGF (with 0.01% DMSO or 100 μM R294) was added to each culture and replaced with fresh medium during the culture period. At the end of this period, pictures of the vascular areas around the aorta were taken using a bright-field microscope in a random manner using a × 10 objective.

To stain the endothelial cells in the 3D culture, the collagen gels were fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin for 20 min and gently detached from the dishes with a transfer pipette. After washing three times with dH2O, the collagen gels were stored in the last wash for 16 h. The gels were then transferred into 35 mm petri dishes with a bent spatula. The whole-staining process was performed on a rotating platform to ensure the uniform exchange of reagents. The fixed gels were blocked with 5% rabbit serum in PBS, pH 7.4 (blocking buffer) for 1 h and then washed once with PBS, pH 7.4 (5 min). After incubating with the primary anti-CD31 antibody in blocking buffer (1 : 100 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature, the gels were washed three times with PBS, pH 7.4 (10 min/wash). FITC-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse secondary antibody in blocking buffer (1 : 100 dilution) was incubated with the collagen gels for 1 h at room temperature, followed by another set of washes with PBS, pH 7.4 (three times, 10 min/wash). The fluorescence signal from the mounted samples was visualised under a fluorescence microscope with a × 20 objective.

Migration and proliferation assays via IncuCyte system

The experiment was performed using the ESSEN IncuCyte system. Graduated 96-well plates from ESSEN were pre-coated with FN and used to seed HUVECs. When reaching 90–95% confluency, a wound was made on every well using the Wound Maker 96 instrument (ESSEN instruments). For inhibition experiments, HUVECs were pre-treated for 3 h before wounding and then allowed to migrate into the wound area at 37 °C for 18 h after the wound was introduced. Cell migration was monitored and analysed by the IncuCyte software.

After incubation for 96 h at 37 °C, the proliferation of HUVEC-TG2wt or HUVEC-TG2kd cells (5 × 103 cells/well in complete EGM medium) was studied by measuring the fluorescence in two different fields per well was measured every 3 h. The mean of the data was calculated and plotted in using the ESSEN IncuCyte software.

Western blot and fluorescence staining

SDS–PAGE and western blotting was performed by using specific antibodies listed in Supplementary Table S4 as described previously, while the membranes were re-probed with α-tubulin as the loading control. For the ECM VEGF, the matrix fraction was collected from HUVECs cultured in either 60 mm petri dishes (1 × 106 cells/dish) for 48 h with treatments. Following lifting the cells with 2 mM EDTA in PBS, pH 7.4, the remaining matrix was incubated with 0.1% deoxycholate in 2 mM EDTA in PBS, pH 7.4 for 10 min. After washing twice with PBS, pH 7.4, the remaining matrices were collected and denatured in Laemmli buffer for western blotting.

For actin cytoskeleton and FA staining, cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS, pH 7.4, permeabilised with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS, pH 7.4 and blocked with 3% BSA in PBS, pH 7.4 (blocking buffer) at 37 °C for 30 min. Cells were then incubated 1 h at 37 °C with FITC or TRITC-conjugated phalloidin for F-actin in blocking buffer. Anti-vinculin antibody and TRITC-conjugated secondary antibody were used for detecting the FAs.

To detect FN deposited by HUVECs, cells (7 × 104/chamber in complete EGM medium) were cultured for 48 h in chamber slides. Live cells were cultured with anti-FN antibody for 2 h and then fixed, permeabilised and incubated with TRITC-conjugated secondary antibody for 2 h at 37 °C, as described above. Cells were finally mounted with Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK) and the fluorescence signals visualised using a Leica epifluorescent microscope (Milton Keynes, UK). For the biotin-labelled FN deposition, the cells were cultured with biotin-labelled FN (50 nM) for 48 h and the presence of the labelled FN in the remaining ECM was detected using Cy5-conjugated Strep-Avidin and Extr-Avidin via confocal microscopy and western blotting, respectively, as described previously.8

Co-immunoprecipitation

The co-immunoprecipitation was performed as introduced previously (Wang et al.8). Briefly, HUVECs were treated with TG2 inhibitor R294 (100 μM) or 0.01% DMSO (the vehicle control) for 48 h and lysed in the co-immunoprecipitation buffer (0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1% (v/v) protein inhibitor mixture). Following pre-clearing the cell lysates, 200 μg of cell lysates were incubated with 0.5 μg of anti-β1 integrin antibody for 90 min and subsequently incubated with 50 μl of Protein A beads for 2 h. The β1 integrin complex was extracted from the beads via boiling the sample with Laemmli buffer for 5 min and the presence of VEGFR2 was detected via western blotting as described above.

The CAM assay

One day fertilised eggs were incubated for 4 days at 37.5 °C and 60–70% humidity. At day 4, ∼2 ml of albumin was removed from the egg and a small window made on the upper part of the egg. Two disks of 0.5 mm pre-soaked in R294 (100 μM) or the vehicle 0.01% DMSO were then introduced around the embryo on the vascular area. After 6 days, pictures were taken of the disk areas and the number of vascular branches were counted both in the disk area and in the invading branches to the disk area as described previously.37 All data were normalised to their own control in the same egg, and expressed as arbitrary units. Statistical analysis was then undertaken by the Kruskal–Wallis test.

Angiogenesis induction in mice using Matrigel plug assay

Balb/C female mice of 4–6 weeks old (Harlan Laboratories Inc, Horst, the Netherlands) were housed at 22 °C, with water and food freely available and with a 12 h light/dark cycle. The animals were cared for and used in accordance with the regulations in Finland (62/2006 and 36/EEo/2006) and the European Union (86/609/EC). In addition, the protocol was approved by the Finnish authorities and the Turku Central Animal Laboratory, Turku University, Finland.

Matrigel containing 10 μg/kg of EPO to induce angiogenesis as well as inhibitors for TG2 (at 250 or 500 μM) or their respective vehicle control (PBS or DMSO) were injected subcutaneously in the right flank of Balb/C mice. Mice were then injected on a daily basis with 500 μl of inhibitor (250 and 500 μM) or vehicle at the site of the Matrigel plug. After 8 days, the skin containing the Matrigel plugs was excised and snap-frozen. Frozen sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and analysed by immunofluorescence first using an anti-von Willebrant factor antibody and a secondary antibody labelled with Alexa 488. Sections were counter stained with 4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Samples were visualised using an Olympus BX60 epifluorescent microscope (Southend-on-Sea, UK) quantitative data were obtained by counting the number of von Willebrant-positive blood vessels and the total number of positively staining cells in five randomly chosen separate areas in digitalised images covering the whole Matrigel area, using ImageJ software. Data shown are normalised to the control group and expressed in arbitrary units.

Statistical analysis

Unless stated otherwise, all values are presented as the mean±S.D. Data analyses were performed using either the Turkey and Dunnet test or the Student's t-test. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance, which is indicated in the text. For in vivo angiogenesis assays in mice, the statistical analysis used was the Kruskal–Wallis test.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work was mainly from the EC Marie Curie IAPP TRANSCOM (Contract No PIA-GA-2010-251506). We would like to thank Dr. Gail Johnson for providing the Lentiviral vectors and Dr. Soner Gundemier for the kind help with the preparation of the lentiviral particles and Dr. Russell Collighan for helpful discussions.

Glossary

- TG2

tissue transglutaminase

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- FN

fibronectin

- EC

endothelial cells

- rh

recombinant human

- EPO

erythropoietin

- HUVECs

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- VEGFR

VEGF receptor

- MEF

mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- Z-DON

Z-DON-Val-Pro-Leu-OMe

- wt

wild-type

- kd

knockdown

- CAM

chick chorioallantoic membrane

- DAPI

4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Disease website (http://www.nature.com/cddis)

Edited by A Stephanou

Supplementary Material

References

- Lieu C, Heymach J, Overman M, Tran H, Kopetz S. Beyond VEGF: inhibition of the fibroblast growth factor pathway and antiangiogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:6130–6139. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellberg C, Ostman A, Heldin CH. PDGF and vessel maturation. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2010;180:103–114. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-78281-0_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemerink MJ, Augustin AJ, Schlingemann RO. Mechanisms of ocular angiogenesis and its molecular mediators. Dev Ophthalmol. 2010;46:4–20. doi: 10.1159/000320006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn RS, Zhu AX. Targeting angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma: focus on VEGF and bevacizumab. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:503–509. doi: 10.1586/era.09.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roodhart JM, Langenberg MH, Witteveen E, Voest EE. The molecular basis of class side effects due to treatment with inhibitors of the VEGF/VEGFR pathway. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2008;3:132–143. doi: 10.2174/157488408784293705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graeven U, Rodeck U, Karpinski S, Jost M, Philippou S, Schmiegel W. Modulation of angiogenesis and tumorigenicity of human melanocytic cells by vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7282–7290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin M, Casadio R, Bergamini CM. Transglutaminases: nature's biological glues. Biochem J. 2002;368:2002. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Collighan RJ, Gross SR, Danen EH, Orend G, Telci D, et al. RGD-independent cell adhesion via a tissue transglutaminase-fibronectin matrix promotes fibronectin fibril deposition and requires syndecan-4/2 and {alpha}5{beta}1 integrin co-signaling. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:40212–40229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.123703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RA, Wang Z, Dookie S, Griffin M. The role of TG2 in ECV304-related vasculogenic mimicry. Amino Acids. 2013;44:89–101. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-1214-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suda K, Rothen-Rutishauser B, Gunthert M, Wunderli-Allenspach H. Phenotypic characterization of human umbilical vein endothelial (ECV304) and urinary carcinoma (T24) cells: endothelial versus epithelial features. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2001;37:505–514. doi: 10.1290/1071-2690(2001)037<0505:PCOHUV>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badarau E, Mongeot A, Collighan R, Rathbone D, Griffin M. Imidazolium-based warheads strongly influence activity of waster-soluble peptidic transglutmainase inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2013;66:526–530. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin M, Mongeot A, Collighan R, Saint RE, Jones RA, Coutts IG, et al. Synthesis of potent water-soluble tissue transglutaminase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:5559–5562. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund KF, Doshi KP, Gaul SL, Claremon DA, Remy DC, Baldwin JJ, et al. Transglutaminase inhibition by 2-[(2-oxopropyl)thio]imidazolium derivatives: mechanism of factor XIIIa inactivation. Biochemistry. 1994;33:10109–10119. doi: 10.1021/bi00199a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RA, Kotasakis P, Johnson TS, Chau DY, Ali S, Melino G, et al. Matrix changes induced by transglutaminase 2 lead to inhibition of angiogenesis and tumor growth. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1442–1453. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConoughey SJ, Basso M, Niatsetakays ZV, Sleiman SF, Smirnova NA, Langley BC, et al. Inhibition of transglutaminase 2 mitigates transcriptional dysregulation in models of Huntington disease. EMBO Mol Med. 2010;2:349–370. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201000084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop ET, Bell GT, Bloor S, Broom IJ, Hendry NF, Wheatley DN. An in vitro model of angiogenesis: basic features. Angiogenesis. 1999;3:335–344. doi: 10.1023/a:1026546219962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries JD, Wang P, Streuli C, Geiger B, Humphries MJ, Ballestrem C. Vinculin controls focal adhesion formation by direct interactions with talin and actin. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:1043–1057. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Sauze S, Grall D, Cseh B, Van Obberghen-Schilling E. Regulation of fibronectin matrix assembly and capillary morphogenesis in endothelial cells by Rho family GTPases. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:2092–2104. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haroon ZA, Hettasch JM, Lai TS, Dewhirst MW, Greenberg CS. Tissue transglutaminase is expressed, active, and directly involved in rat dermal wound healing and angiogenesis. FASEB J. 1999;13:1787–1795. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.13.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martucciello S, Lavric M, Toth B, Korponay-Szabo I, Nadalutti C, Myrsky E, et al. RhoB is associated with the anti-angiogenic effects of celiac patient transglutaminase 2-targeted autoantibodies. J Mol Med. 2012;90:817–826. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0853-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell SE, Mavila A, Salazar R, Bayless KJ, Kanagala S, Maxwell SA, et al. Differential gene expression during capillary morphogenesis in 3D collagen matrices: regulated expression of genes involved in basement membrane matrix assembly, cell cycle progression, cellular differentiation and G-protein signaling. J Cell Sci. 2011;114:2755–2773. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.15.2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faye C, Inforzata A, Bignon M, Hartmann DJ, Muller L, Ballut L, et al. Transglutaminase-2: a new endostatin partner in the extracellular matrix of endothelial cells. Biochem J. 2010;427:467–475. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Collighan RJ, Pytel K, Rathbone DL, Li X, Orend G, et al. Characterization of heparin-binding site of tissue transglutaminase: its importance in cell surface targeting, matrix deposition, and cell signaling. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:13063–13083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.294819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Griffin M. TG2, a novel extracellular protein with multiple functions. Amino Acids. 2012;42:939–949. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-1008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iismaa SE, Mearns BM, Lorand L, Graham RM. Transglutaminases and disease: lessons from genetically engineered mouse models and inherited disorders. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:991–1023. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deasey S, Shanmugasundaram S, Nurminskaya M. Tissue-specific responses to loss of transglutaminase 2. Amino Acids. 2013;44:179–187. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-1183-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth B, Sarang Z, Vereb G, Zhang AL, Tanaka S, Melino G, et al. Over-expression of integrin beta 3 can partially overcome the defect of integrin beta 3 signaling in transglutaminase 2 null macrophages. Immunol Lett. 2009;126:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akimov SS, Krylov D, Fleischman LF, Belkin AM. Tissue transglutaminase is an integrin-binding adhesion coreceptor for fibronectin. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:825–838. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.4.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy H, Bhardwaj S, Yla-Herttuala S. Biology of vascular endothelial growth factors. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:2879–2887. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.03.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TT, Juque A, Lee S, Anderson SM. Segura and Iruela-Arispe ML. Anchorage of VEGF to the extracellular matrix conveys differential signaling responses to endothelial cells. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:595–609. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200906044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta RR, Yamada T, Taylor BN, Christov K, King ML, Majumdar D, et al. A cell penetrating peptide derived from azurin inhibits angiogenesis and tumor growth by inhibiting phosphorylation of VEGFR-2, FAK and Akt. Angiogenesis. 2011;14:355–369. doi: 10.1007/s10456-011-9220-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaoz E, Okcu A, Gacar G, Saglam O, Yurucker S, Kenar H. A comprehensive characterization study of human bone marrow mscs with an emphasis on molecular and ultrastructural properties. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:1367–1382. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colak G, Keillor JW, Johnson GV. Cytosolic guanine nucledotide binding deficient form of transglutaminase 2 (R580a) potentiates cell death in oxygen glucose deprivation. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16665. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh W, Stratman AN, Sacharidou A, Davis GE. In vitro three dimensional collagen matrix models of endothelial lumen formation during vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. Methods Enzymol. 2008;443:83–101. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)02005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotsakis P, Wang Z, Collighan RJ, Griffin M. The role of tissue transglutaminase (TG2) in regulating the tumour progression of the mouse colon carcinoma CT26. Amino Acids. 2011;41:909–921. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0790-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Nicosia RF. The thin prep rat aortic ring assay: a modified method for the characterization of angiogensis in whole mounts. Angiogenesis. 2002;5:81–86. doi: 10.1023/a:1021509004829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deryugina EI, Quigley JP.Chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane models to quantify angiogenesis induced by inflammatory and tumor cells or purified effector moleculesChapter 2Methods Enzymol 200844421–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.