Abstract

The evolutionarily conserved process of programmed cell death, apoptosis, is essential for development of multicellular organisms and is also a protective mechanism against cellular damage. We have identified dynein light chain 1 (DLC-1) as a new regulator of germ cell apoptosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. The DLC-1 protein is highly conserved across species and is a part of the dynein motor complex. There is, however, increasing evidence for dynein-independent functions of DLC-1, and our data describe a novel dynein-independent role. In mammalian cells, DLC-1 is important for cellular transport, cell division and regulation of protein activity, and it has been implicated in cancer. In C. elegans, we find that knockdown of dlc-1 by RNA interference (RNAi) induces excessive apoptosis in the germline but not in somatic cells during development. We show that DLC-1 mediates apoptosis through the genes lin-35, egl-1 and ced-13, which are all involved in the response to ionising radiation (IR)-induced apoptosis. In accordance with this, we show that IR cannot further induce apoptosis in dlc-1(RNAi) animals. Furthermore, we find that DLC-1 is functioning cell nonautonomously through the same pathway as kri-1 in response to IR-induced apoptosis and that DLC-1 regulates the levels of KRI-1. Our results strengthen the notion of a highly dynamic communication between somatic cells and germ cells in regulating the apoptotic process.

Keywords: dynein light chain 1, apoptosis, DNA damage, C. elegans

Apoptosis is the process in which external or internal cues induce self-elimination of the cell. Apoptosis is an evolutionarily conserved key process in the development of multicellular organisms and is also implicated in the aetiology of several diseases such as cancer and neurodegeneration.1, 2 In Caenorhabditis elegans, invariably, 131 somatic cells undergo apoptosis during development (developmental apoptosis) of the hermaphrodite,3, 4 and in the adult half of the germ cells are eliminated by apoptosis (physiological germ cell apoptosis).5 These types of apoptosis in C. elegans depend on the core apoptotic machinery comprising the caspase CED-3,6 the adaptor protein Apaf-1 homologue CED-47 and the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 homologue CED-9.8 Strong loss-of-function mutations in ced-3 or ced-4 as well as a gain-of-function (gf) mutation in ced-9 completely inhibit apoptosis.5, 9 DNA damage can also induce germ cell apoptosis (DNA damage-induced apoptosis) in the hermaphrodite germline.10 In addition to the core apoptotic machinery, DNA damage-induced apoptosis also depends on the tumour-suppressor p53 homologue CEP-111, 12 and the BH3-only proteins EGL-1 and CED-13.13, 14 All of these genes are functioning inside the dying cells to regulate the killing process. However, the genes vab-1 (ephrin receptor) and kri-1 (ankyrin-repeat protein orthologous to the human KRIT1/CCM1) have been shown to cell nonautonomously regulate physiological and ionising radiation (IR)-induced germ cell apoptosis, respectively.15, 16

Apoptotic cells are removed by engulfment, and in the germline engulfment is carried out by the surrounding sheath cells.17 Two partially redundant pathways regulate engulfment.18 One pathway consists of the transmembrane receptor ced-1, the adaptor protein ced-6 (GULP) and ced-7 (ABC1).19, 20, 21, 22 The other pathway comprises the adaptor protein ced-2 (CrkII), the guanine nucleotide-exchange factors ced-5 (DOCK180) and ced-12 (ELMO) and ced-10 (RAC1).23, 24, 25, 26 Mutations in several engulfment genes impair the removal of dead cells, which consequently persist longer.18

Cytoplasmic dyneins are multisubunit motor protein complexes associated with microtubules. Large heavy chains comprise the bulk of the dynein complexes and confer motor activity, whereas the intermediate and light chains are accessory subunits that bind cargo.27, 28 The mammalian dynein light chain DYNLL1 is highly conserved with 95% homology to the C. elegans homologue DLC-1. DYNLL1 is implicated in dynein-regulating processes such as vesicular and protein transport, cell division, mitotic spindle formation and nuclear migration.29, 30 DYNLL1 binds to a variety of proteins besides dynein including the following: the pro-apoptotic protein BimL,31 p53-binding protein 132, 33 and the cell cycle regulators Cdk2 and Ciz1.34 There is increasing evidence that DYNLL1 can act independent of its association with microtubules.35, 36 Several interaction partners of DYNLL1 regulate cell viability,31, 33, 34 and DYNLL1 is overexpressed in breast tumours.37 In accordance with a high evolutionary conservation, the C. elegans homologue DLC-1 affects germ cell proliferation, and inactivation of dlc-1 by RNA interference (RNAi) in a tumour-promoting background results in hyperproliferating and polyploid germ cells.38

We previously conducted a whole-genome RNAi screen with a view of identifying genes conferring resistance to the chemotherapeutic drug hydroxyurea (HU) (unpublished). The genes identified in the screen were analysed for germ cell apoptosis, and RNAi against dynein light chain 1 (dlc-1) caused a significant increase in the number of apoptotic germ cells. In this study, we describe a novel role of dlc-1 in regulating IR-induced germ cell apoptosis by a cell-nonautonomous function via kri-1. We show that DLC-1 is functioning via egl-1 and ced-13 independently of cep-1.

Results

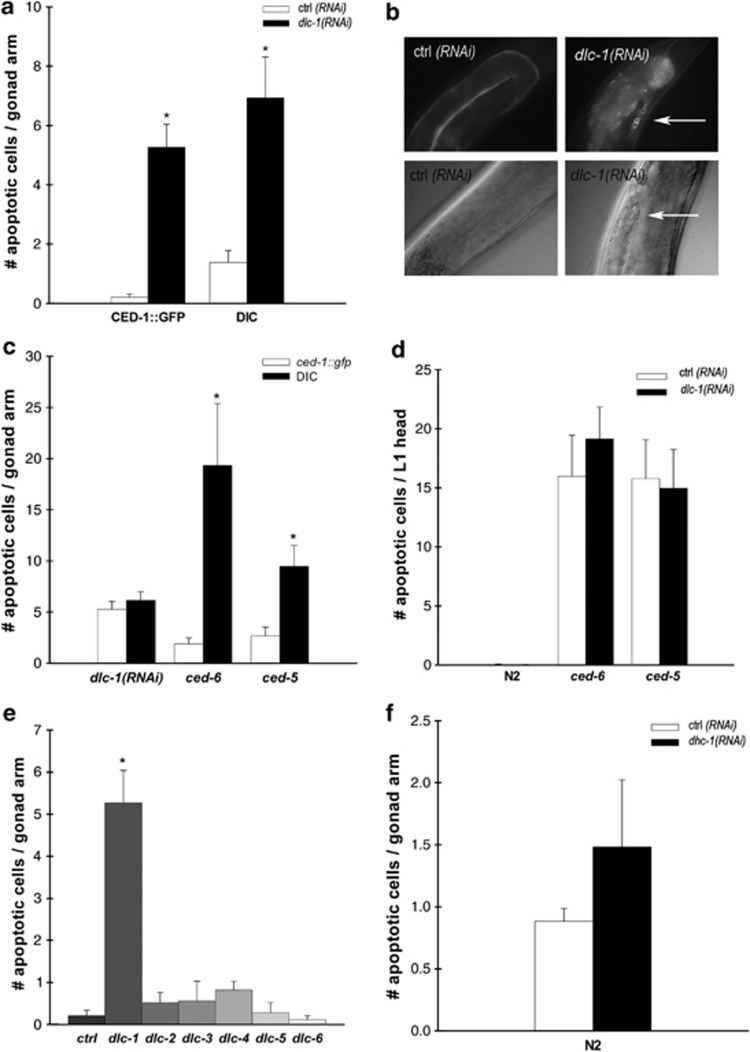

Lack of dlc-1 induces germ cells to undergo apoptosis

To investigate the effect of dlc-1 inactivation on germ cell apoptosis, we treated worms with RNAi against dlc-1 and quantified apoptosis using differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy and the CED-1::GFP (green-fluorescent protein) reporter. During the engulfment process, the transmembrane receptor CED-1 expressed in sheath cells clusters around apoptotic cells.19 CED-1::GFP (Plim-7::ced-1::gfp, bcIs39) can therefore be used to quantify apoptotic germ cells undergoing engulfment. The dlc-1(RNAi) animals had significantly more GFP-positive cells than the controls (Figures 1a and b). A significant increase in the number of apoptotic cells following RNAi against dlc-1 was also seen using DIC microscopy (Figures 1a and b). The RNAi treatment reduced the expression of dlc-1 with 80–90% compared with controls (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Inactivation of dlc-1 results in increased germ cell apoptosis independent of the dynein motor complex. (a) Mean number of apoptotic cells per gonad arm after RNAi against dlc-1, scored with both CED-1::GFP and DIC. (b) Epifluorescence ( × 40) and DIC ( × 40) pictures of ctrl and dlc-1(RNAi) gonads. Arrows point to apoptotic cells. (c) Comparison between apoptosis scored with DIC and CED-1::GFP in dlc-1(RNAi), ced-6(tm1826) and ced-5(tm1950) animals. (d) Mean number of apoptotic cells in the head of freshly hatched L1 larvae in N2, ced-5(tm1950) and ced-6(tm1826) mutants treated with ctrl of dlc-1 RNAi, scored with DIC. (e) Mean number of apoptotic cells per gonad arm after RNAi against dlc-1–6, scored with CED-1::GFP. (f) Mean number of apoptotic cells per gonad arm in dhc-1(RNAi)-treated animals. All graphs are mean (±S.D.) of at least three independent experiments. N=20–40 gonad arms for each experiment. *P<0.05

We reasoned that the increased number of apoptotic cells in the dlc-1(RNAi) animals could be because of excessive germ cells undergoing apoptosis or an engulfment defect preventing their removal. The CED-1::GFP marker can only be used if proper internalisation of the dead cells is taking place during the engulfment process; consequently, the CED-1::GFP marker does not detect apoptotic cells in the engulfment-defective mutants ced-5 and ced-6.39 We confirmed that persistent cell corpses observable with DIC in ced-5(tm1950) and ced-6(tm1826) mutants could not be seen with the CED-1::GFP marker (Figure 1c). Therefore, as the apoptotic cells in dlc-1(RNAi) animals could be observed equally well with DIC and CED-1::GFP, RNAi against dlc-1 did not result in an engulfment defect. Thus, dlc-1(RNAi) animals do not phenocopy engulfment-defective mutants.

To investigate whether dlc-1 is also involved in somatic apoptosis during development, we analysed L1 larvae for the presence of persistent cell corpses in the head with DIC microscopy. Wild-type N2 larvae have no visible cell corpses, whereas engulfment mutants, such as ced-5(tm1950) and ced-6(tm1826), have many persistent cell corpses18 (and Figure 1d). Inactivation of dlc-1 in wild-type N2 worms did not result in persistent cell corpses, indicating that dlc-1 does not affect engulfment during development. Increased apoptosis during development can be seen in engulfment-defective mutant backgrounds, as the extra dead cells are not as efficiently removed as in wild-type worms. However, RNAi against dlc-1 had no effect on the number of corpses observed in ced-5 or ced-6 mutants (Figure 1d). This suggests that RNAi against dlc-1 does not affect somatic cell death or engulfment but specifically increases germ cell apoptosis.

DLC-1 affects apoptosis independently of the dynein motor complex

In addition to dlc-1, the C. elegans genome encodes five other light chains (dlc-2–6). We speculated whether the observed apoptotic phenotype was specific for the inactivation of dlc-1 or whether it was a general phenotype for all the dynein light chains. Following their inactivation, none of the other five light chains resulted in an increased number of apoptotic germ cells (Figure 1e). Furthermore, we also investigated the effect on apoptosis after knockdown of the main dynein heavy chain, dhc-1. As RNAi against dhc-1 causes developmental arrest, we treated N2 wild-type worms with RNAi against dhc-1 from the L4 stage and scored apoptosis 48 h later using DIC, but no effect on germ cell apoptosis was observed (Figure 1f). This indicates that the increase in apoptotic cells is specific for dlc-1 and is not a general phenotype from a disrupted dynein complex.

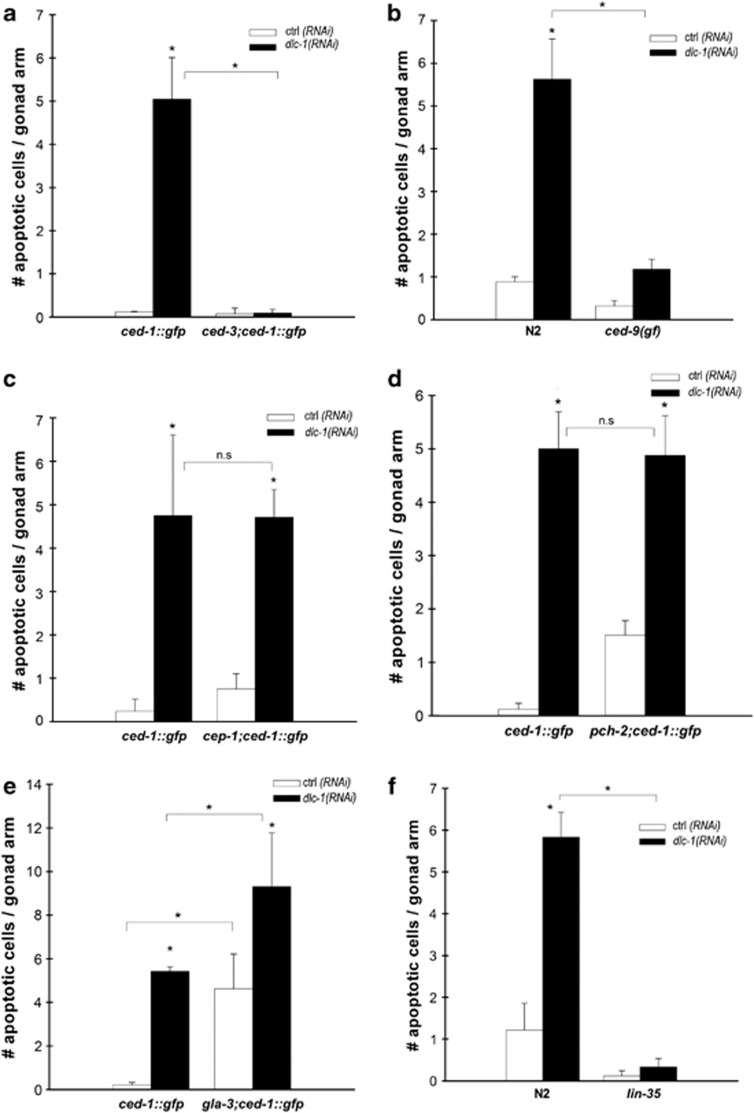

Lack of dlc-1 induces apoptosis through CED-3, CED-9 and LIN-35

Strong loss-of-function mutations in ced-3 or ced-4 completely inhibit both somatic and germ cell apoptosis. We inactivated dlc-1 in a mutant harbouring the strong loss-of-function allele ced-3(n717) and expressing the CED-1::GFP marker. The ced-3(n717) mutation completely suppressed apoptosis because of RNAi against dlc-1 (Figure 2a). ced-3-independent apoptosis has been reported following RNAi against the inhibitor of cell death-1 (icd-1) gene, which encodes the beta-subunit of the nascent polypeptide-associated complex (bNAC).40 Therefore, as an additional control we treated ced-3(n717) mutants with icd-1 RNAi. In agreement with the previous report, we observed that ced-3 could not completely suppress apoptosis induced by RNAi against icd-1 (Supplementary Figure S2). Thus, inactivation of dlc-1 increases the number of apoptotic germ cells exclusively through the ced-3 pathway. As almost all types of apoptosis in C. elegans require the core apoptotic machinery, we next decided to use an epistasis analysis approach to determine the subtype of apoptosis influenced by RNAi against dlc-1.

Figure 2.

dlc-1(RNAi) induces apoptosis through CED-3, CED-9 and LIN-35 (a). Mean number of apoptotic cells per gonad arm after RNAi against dlc-1 in a ced-3(n717) mutant, scored with CE-1::GFP. (b) Mean number of apoptotic cells per gonad arm after RNAi against dlc-1 in a ced-9(n1950) mutant, scored with DIC. (c) Mean number of apoptotic cells per gonad arm after RNAi against dlc-1 in cep-1(gk138) mutants, scored with CED-1::GFP. (d) Mean number of apoptotic cells per gonad arm after RNAi against dlc-1 in pch-2(tm1458) mutants, scored with CED-1::GFP. (e) Mean number of apoptotic cells per gonad arm after RNAi against dlc-1 in gla-3(ok2684) mutants, scored with CED-1::GFP. (f) Mean number of apoptotic cells per gonad arm after RNAi against dlc-1 in lin-35(n745) mutants, scored with DIC. All graphs are mean (±S.D.) of at least three independent experiments. N=20–40 gonad arms for each experiment. *P<0.05

Physiological germ cell death is independent of the core apoptotic machinery gene ced-9.5 We tested whether dlc-1(RNAi)-induced apoptosis was independent of a ced-9 gf mutation (n1950). However, dlc-1(RNAi)-induced apoptosis was completely abolished in the ced-9(gf) mutant, indicating that ced-9 was required for dlc-1(RNAi) to induce apoptosis (Figure 2b). Thus, dlc-1 is not involved in physiological germ cell death.

Inactivation of dlc-1 results in a tumorous germline and unpaired chromosomes in the oocytes.38 Therefore, we hypothesised that these phenotypes might lead to DNA damage-induced apoptosis through CED-9. In C. elegans, DNA damage-induced apoptosis is dependent on the p53 homologue cep-1.11 Hence, we investigated whether dlc-1(RNAi) could induce apoptosis in cep-1(gk138) mutants. RNAi against dlc-1 induced apoptosis in the cep-1 mutants to the same extent as in wild-type N2 animals (Figure 2c). Thus, dlc-1(RNAi) does not result in apoptosis because of an increased level of DNA damage. Unpaired chromosomes can trigger a synapsis checkpoint independent of the DNA-damage checkpoint, which requires the activity of PCH-2, the C. elegans homologue of PCH2, a budding yeast pachytene checkpoint gene.41 We found that inactivation of dlc-1 induced apoptosis in pch-2 mutants to a similar extent as seen in wild-type N2 animals (Figure 2d). Thus, dlc-1(RNAi) does not induce apoptosis because of unpaired chromosomes.

Several pathways have been shown to feed into the core apoptotic machinery through CED-9, such as the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and retinoblastoma (RB) tumour-suppressor pathways.5, 42 Overactivation of MAPK – for example, by loss of the inhibitor GLA-3 – causes excessive germ cell apoptosis.43 gla-3 mutants and dlc-1(RNAi) animals had approximately equal levels of apoptosis, whereas the gla-3(ok2684);dlc-1(RNAi) animals had significantly higher levels of germ cell apoptosis than either of the single mutant/RNAi animals (Figure 2e), consistent with gla-3 and dlc-1 functioning in separate pathways to induce apoptosis. LIN-35, the C. elegans ortholog of the RB tumor-suppressor p105Rb, is involved in both physiological and DNA damage-induced germ cell apoptosis; however, contrary to gla-3, loss of lin-35 inhibits apoptosis.42 In lin-35(n745) mutants, RNAi against dlc-1-induced apoptosis was completely suppressed (Figure 2f). Thus, we conclude that normally DLC-1 acts upstream of LIN-35 to protect against apoptosis. LIN-35 represses the transcription of ced-9;42 hence, we hypothesised that DLC-1 could directly or indirectly affect the activity of LIN-35 and thereby the transcription of ced-9. We analysed the expression of lin-35 and ced-9 in dlc-1(RNAi) animals but observed no changes in their expression (Supplementary Figure S3), demonstrating that dlc-1 does not affect lin-35 and ced-9 activity at the transcriptional level.

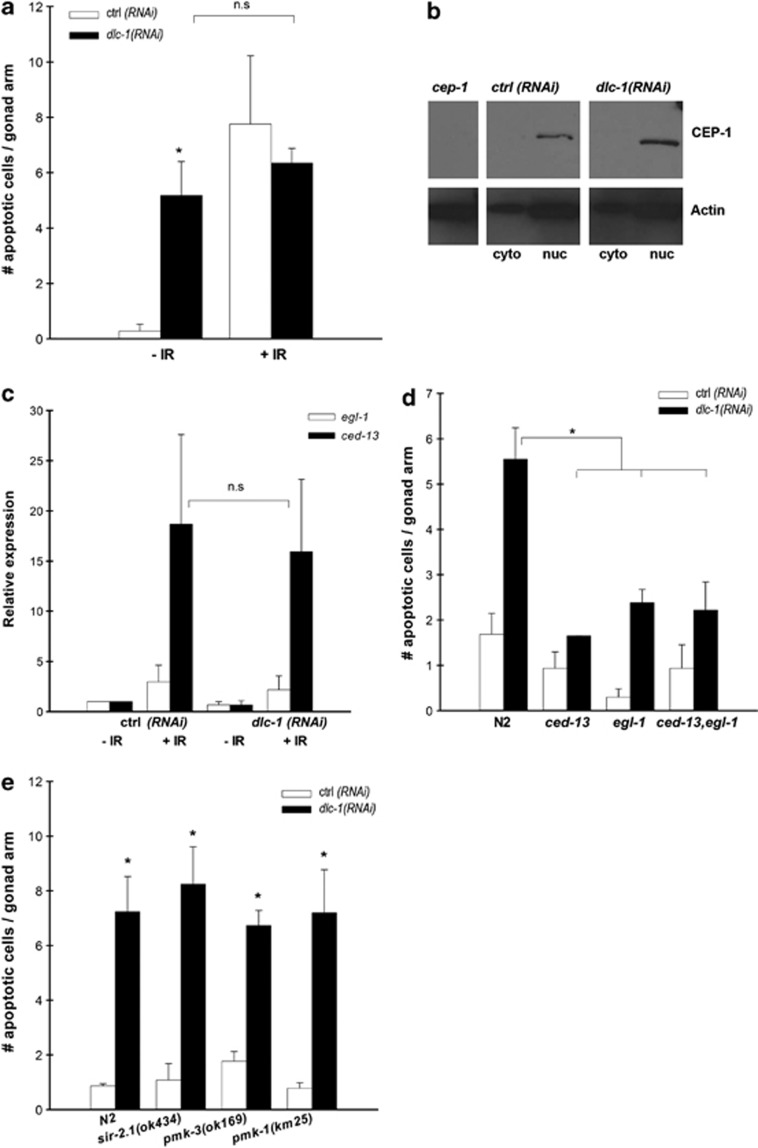

DLC-1 is a part of the response to IR-induced apoptosis

As dlc-1(RNAi)-induced apoptosis was independent of cep-1 but dependent on lin-35, both of which are involved in response to DNA damage, we evaluated how dlc-1(RNAi) animals responded to DNA damage induced by IR. Interestingly, IR did not increase the number of apoptotic cells in dlc-1(RNAi) animals (Figure 3a), indicating that IR and dlc-1 function in a common pathway.

Figure 3.

DLC-1 is acting upstream of EGL-1 and CED-13 in response to IR. (a) Mean number of apoptotic cells per gonad arm after IR in ctrl and dlc-1 RNAi worms, scored with CED-1::GFP. (b) Western blot of CEP-1 localisation in nuclear (nuc) and cytoplasmic (cyto) extractions from worms fed ctrl or dlc-1 RNAi. First lane is whole-worm extract form cep-1 mutants. Actin is used as loading control. (c) qPCR of egl-1 and ced-13 transcription after IR in worms fed ctrl or dlc-1 RNAi. Relative expression is calculated by the Pfaffl method and compared with ctrl without IR. (d) Mean number of apoptotic cells per gonad arm after RNAi against dlc-1 in N2, ced-13(tm536), egl-1(n1084n3082) and ced-13(tm536);egl-1(n1084n3082) mutants, scored with DIC. (e) Mean number of apoptotic cells per gonad arm in sir-2.1(ok434), pmk-3(ok169) and pmk-1(km25) treated with dlc-1 RNAi, scored with DIC. All graphs are mean (±S.D.) of at least three independent experiments. For the apoptosis assays, N=20–40 gonad arms for each experiment. *P<0.05

In human cells, DLC-1 facilitates the transport of p53 to the nucleus in response to DNA damage.32, 33 The lack of response to IR in dlc-1(RNAi) animals could arise from the mislocalisation or malfunction of CEP-1. Using western blotting with an antibody against the C-terminal of CEP-1, no difference in CEP-1 localisation was observed between control and dlc-1(RNAi) animals; in both CEP-1 was accumulated exclusively in the nucleus (Figure 3b). Furthermore, to evaluate the activity of CEP-1 in dlc-1(RNAi) animals, we used quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) to measure the expression levels of the CEP-1 target genes egl-1 and ced-13, which are upregulated after exposure to IR.14 In both the control and dlc-1(RNAi) animals, the expression levels of egl-1 and ced-13 were upregulated after exposure to IR, suggesting that CEP-1 functions correctly in dlc-1(RNAi) animals (Figure 3c). In contrast, cep-1 mutants could not induce egl-1 transcription in response to IR (Supplementary Figure S4).

We then investigated whether DLC-1 acted in the DNA-damage response pathway downstream or in parallel to cep-1. We quantified germ cell corpses using DIC in egl-1(n1084n3082);dlc-1(RNAi), ced-13(tm536);dlc-1(RNAi) and egl-1(n1084n3082);ced-13(tm536);dlc-1(RNAi) animals and found that dlc-1 RNAi-induced apoptosis was strongly reduced in these mutant backgrounds compared with RNAi against dlc-1 in a wild-type background (Figure 3d). Thus, both functional CED-13 and EGL-1 are required for RNAi against dlc-1 to induce apoptosis. However, RNAi against dlc-1 did not regulate the transcription of egl-1 and ced-13 in the absence of DNA damage (Figure 3c), suggesting that DLC-1 might regulate egl-1 and ced-13 at the protein level.

Other cep-1-independent apoptotic regulators have been described, including sir-2.1,44 pmk-145, 46 and pmk-3.47 Therefore, we investigated the epistatic relationship between dlc-1 and these three genes. SIR-2.1 is a member of the Sirtuins family of NAD+-dependent protein deacetylases shown to regulated IR-induced apoptosis. The p38 homologues of mitogen-activated protein kinase, pmk-1 and pmk-3, are necessary for bacterial and copper-induced germ cell apoptosis, respectively. Neither sir-2.1, pmk-1 nor pmk-3 could suppress dlc-1(RNAi)-induced apoptosis, indicating that they act through different pathways (Figure 3e).

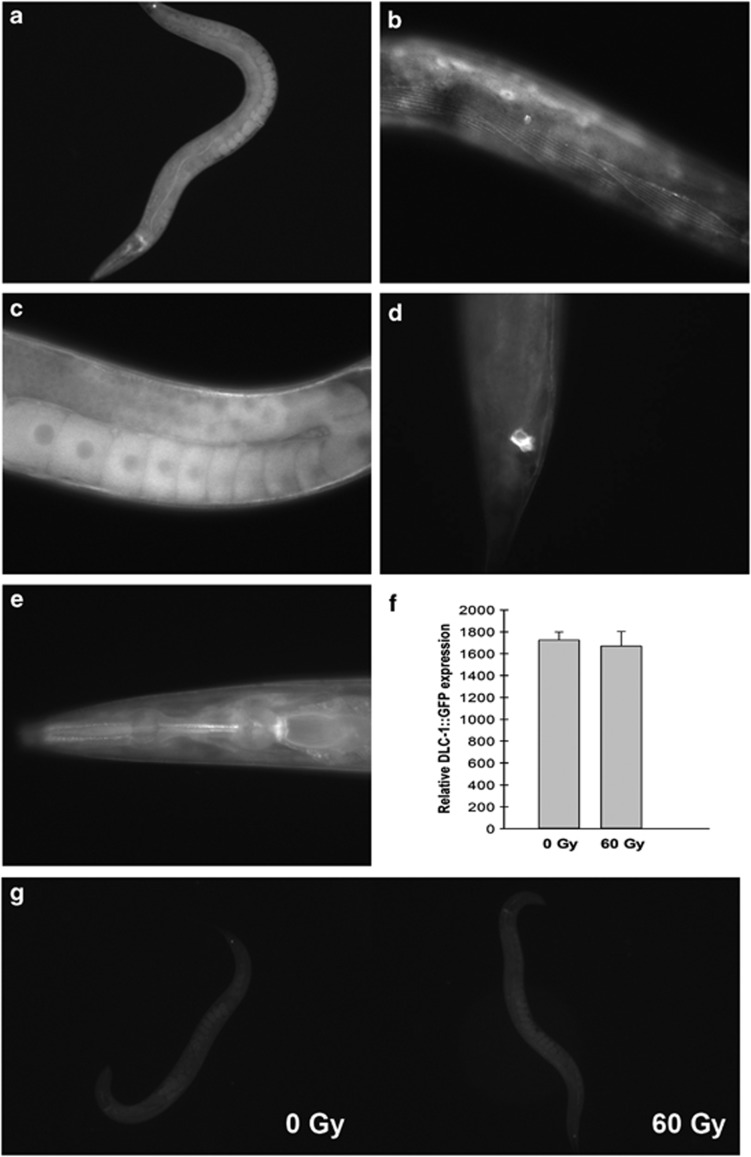

DLC-1 is functioning cell nonautonomously through kri-1

To study the expression and localisation of DLC-1, we generated two independent transgenic lines (Pdlc-1::dlc-1::gfp) expressing GFP-tagged DLC-1 under the regulation of the dlc-1 promotor (Figure 4). We found DLC-1 to be expressed in numerous tissues including those of the intestine (Figure 4a), body wall muscles (Figure 4b), germ cells and oocytes (Figure 4c), the rectal valve cell (Figure 4d) and unidentified cells in the head (Figure 4e). DLC-1 was expressed at all developmental stages from the one-cell embryo. To validate that the transgenic strain was expressing wild-type DLC-1, we treated it with RNAi against dlc-1 and observed that the GFP level was significantly reduced (Supplementary Figure S5), and we used western blotting to confirm that the full-length fusion protein was being expressed (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Transgenic worm expressing Pdlc-1,dlc-1::gfp. (a) Expression of DLC-1::GFP under control of the dlc-1 promoter. (b) Expression of DLC-1::GFP in body wall muscles. (c) DLC-1::GFP is expressed in germ cells and oocytes. (d) DLC-1::GFP is expressed in the rectal valve cells. (e) DLC-1::GFP expression in unidentified cells in the head. (f) Quantification (by ImageJ) of DLC-1::GFP expression after exposure to 0 and 60 Gy. (g) Expression of DLC-1::GFP 24 h after exposure to 60 Gy

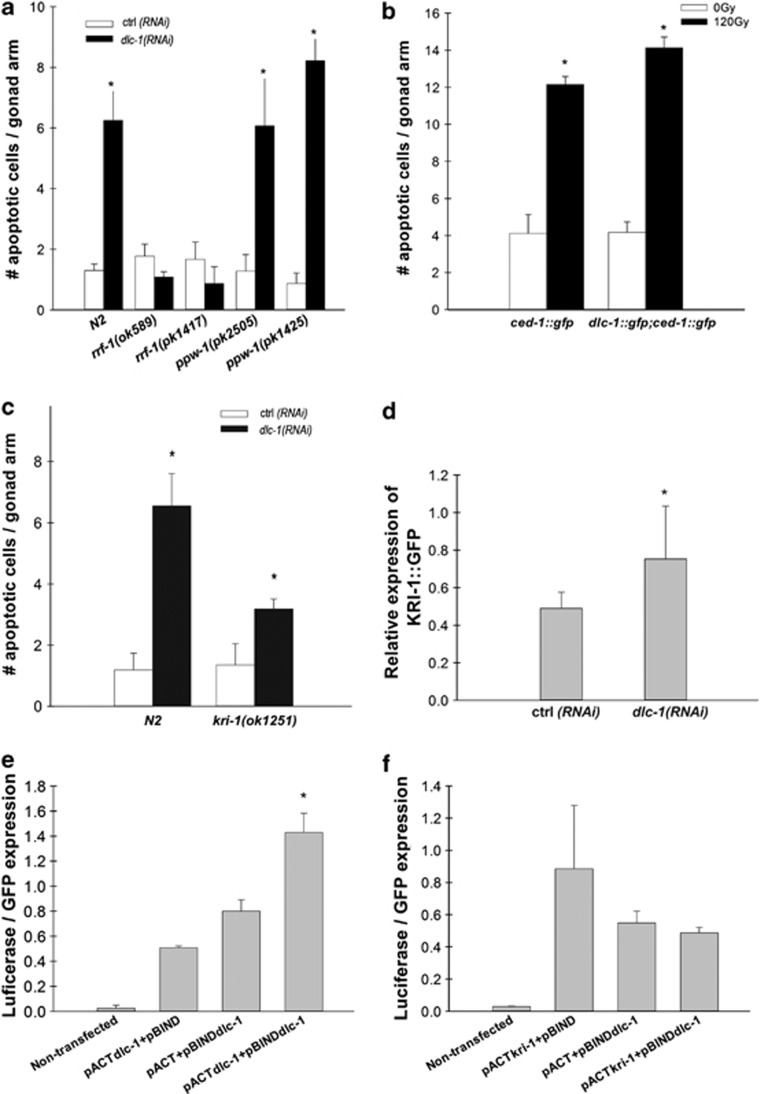

As DLC-1 was expressed both in the germ cells and in somatic tissues, we investigated in which of these tissues inactivation of dlc-1 resulted in increased germ cell apoptosis. The ppw-1 gene encodes a member of the argonaute family of proteins and is required for efficient RNAi in germ cells.48 The rrf-1 gene encodes an RNA-directed RNA polymerase required for activation of the RNAi pathway in somatic cells.49 We treated two different alleles of rrf-1 (pk1417 and ok589) and ppw-1 (pk2505 and pk1425) with RNAi against dlc-1 and quantified the number of apoptotic cells using DIC. We observed that the increase in apoptotic cells caused by dlc-1 RNAi was completely abolished in the rrf-1 mutants but not affected in the ppw-1 mutants (Figure 5a). Therefore, inactivation of dlc-1 only in somatic cells gives rise to the increase in apoptotic cells. To verify the specificity of the rrf-1 and ppw-1 mutants, we treated them with ced-1 RNAi, which induces an engulfment defect. CED-1 functions in the somatic sheath cells but not in the germ cells. As expected, ced-1(RNAi) only induced an engulfment defect in ppw-1 mutants but not in rrf-1 mutants (Supplementary Figure S6).

Figure 5.

DLC-1 is functioning cell nonautonomously through kri-1. (a) Mean number of apoptotic cells per gonad arm after RNAi against dlc-1 in N2, ppw-1(pk2505) and rrf-1(pk1417) mutants, scored with DIC. (b) Mean number of apoptotic cells per gonad arm in Pdlc-1,dlc-1::gfp 24 h after treatment with 120 Gy, scored with CED-1::GFP. (c) Mean number of apoptotic cells per gonad arm after RNAi against dlc-1 in N2 and kri-1(ok1251) mutants. All graphs for apoptosis are mean (±S.D.) of at least three independent experiments. For the apoptosis assays, N=20–40 gonad arms for each experiment. *P<0.05. (d) Expression of KRI-1::GFP after treatment with dlc-1 RNAi for 3 days. Quantified by ImageJ. Representative of three independent experiments. (e) DLC-1–DLC-1 interaction by the use of mammalian two-hybrid system. Representative of three independent experiments (f). DLC-1–KRI-1 interaction by use of mammalian two-hybrid system

As dlc-1 functions in the response to IR, we investigated whether IR regulates dlc-1 at the transcriptional or translational level. However, using qPCR no changes in dlc-1 transcription in response to IR was observed (data not shown). Likewise, we did not observe any changes in the levels of DLC-1::GFP after IR in whole animals (Figure 4f). We also examined the localisation of DLC-1::GFP after IR, but changes were observed neither in whole animals (Figure 4g) nor in sheath cells (Supplementary Figure S7). We also hypothesised that overexpression of DLC-1 might protect against IR-induced apoptosis. However, we observed no difference in the number of apoptotic cells between wild-type N2 and DLC-1::GFP animals when treated with 120 or 60 Gy (Figure 5b and Supplementary Figure S8).

The clear involvement of DLC-1 in somatic tissues in regulating germ cell apoptosis led us to investigate a possible involvement of kri-1. The KRI-1 ankyrin-repeat protein is orthologous to the human KRIT1/CCM1, and it is required for IR-induced apoptosis in a novel pathway acting in somatic cells.16 We examined the epistatic relationship between dlc-1 and kri-1 by treating kri-1(ok1251) mutants with RNAi against dlc-1. kri-1 mutants fed dlc-1 RNAi had significantly fewer apoptotic germ cells than wild-type N2 animals treated with RNAi against dlc-1 (Figure 5c). This indicates that kri-1 is necessary for dlc-1(RNAi)-induced apoptosis. Next, we used a strain expressing the functional KRI-1::GFP protein to examine whether dlc-1 could regulate the expression or localisation of KRI-1. We treated KRI-1::GFP animals with dlc-1 RNAi for 3 days and scored the expression of GFP compared with animals grown on control RNAi. Our results show that dlc-1 RNAi increases the expression of KRI-1::GFP on average with 57% (Figure 5d), demonstrating that dlc-1 can regulate KRI-1. We did not observe any change in localisation of KRI-1::GFP because of RNAi against dlc-1 (Supplementary Figure S9). To test the possibility that DLC-1 and KRI-1 might interact directly, we expressed C. elegans DLC-1 and KRI-1 in a mammalian two-hybrid system using luciferase as readout. As DLC-1 is known to bind to itself in mammalian cells, we used this interaction as a positive control (Figure 5e). However, we did not observe any interaction between DLC-1 and KRI-1 (Figure 5f). Based upon our results we propose that DLC-1 is regulating KRI-1 in response to IR-induced apoptosis to mediate a pro-apoptotic signal from somatic cells to germ cells (Figure 6).

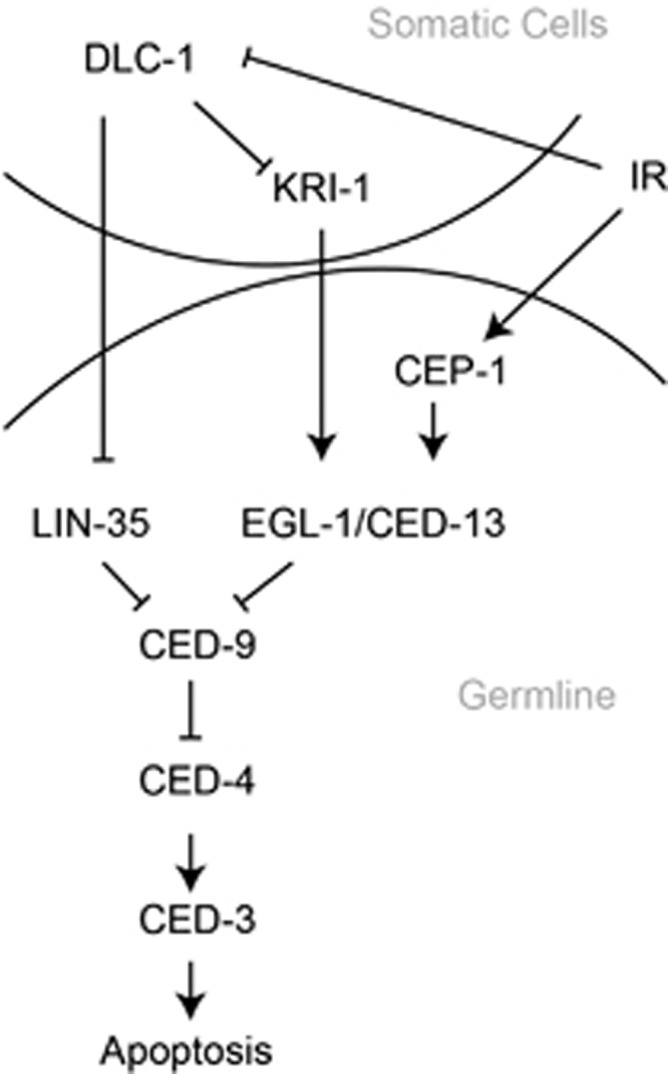

Figure 6.

Model for the role of DLC-1 in regulation of germ cell apoptosis. Our data demonstrate that DLC-1 acts cell nonautonomously through the kri-1 pathway in response to IR by indirectly regulating the activity of the proteins EGL-1, CED-13 and LIN-35 to induce germ cell apoptosis

Discussion

We have identified DLC-1 as a new gene required for proper apoptotic signalling between somatic cells and germ cells in response to IR acting through KRI-1. Our study is thus adding to the knowledge of the recently described KRI-1-mediated response to IR. Firstly, we find that KRI-1 is required for CED-3-dependent apoptosis induced by RNAi against dlc-1. Secondly, our data show that DLC-1 regulates the level of KRI-1. Thirdly, we show that the DLC-1/KRI-1 signalling pathway operates via EGL-1 and CED-13. Based upon these results we propose a model in which DLC-1 is part of the response to IR-induced apoptosis through a cell-nonautonomous pathway depending on kri-1 and independent of cep-1 (Figure 6). Consistent with this model we found that IR did not induce additional apoptosis in dlc-1(RNAi) animals. Our results strongly support that intercellular communication between somatic cells and germ cells is required for proper regulation of the cell-killing process.

Our model raised the possibility that dlc-1 was directly regulated by IR at the transcriptional or translational level. However, we did not observe any changes in expression or localisation of DLC-1::GFP in response to IR. Instead, IR may induce post-translational modifications to DLC-1. In mammalian cells, DLC-1 can be phosphorylated on Ser88 that inactivates DLC-1 by disrupting the homodimer.50 This phosphorylation can be carried out by the p21-activated kinase, Pak-1.37

We have demonstrated that dlc-1(RNAi)-induced apoptosis is dependent on EGL-1 and CED-13; however, DLC-1 is not involved in transcriptional regulation of egl-1 and ced-13. Rather our model predicts a second layer of regulation of the proteins involved in IR-induced apoptosis; CEP-1 regulates the transcription of egl-1 and ced-13, whereas DLC-1 indirectly regulates their activity at the protein level through a cell-nonautonomous pathway, giving a tighter and more fine-tuned regulation of IR-induced apoptosis.

At the molecular level, several mechanisms may explain how DLC-1 regulates apoptosis. One possible underlying molecular mechanism could be that DLC-1 normally binds a pro-apoptotic signal/protein. dlc-1 inactivation or exposure to IR then leads to the release of inhibition of such pro-apoptotic signal that is then transmitted to the germ cells to induce apoptosis by activating the EGL-1 and CED-13 proteins. A similar cell-autonomous mechanism has been described in mammalian cells where DLC-1 binds to the BH3-only protein BimL and sequesters it to the dynein complex. Upon apoptotic stimuli, the DYNLL1–BimL dimer is released and translocated to the mitochondria to induce apoptosis.31 The cell-nonautonomous system that we are describing must contain an intermediate regulating protein, as DLC-1 and EGL-1/CED-13 are functioning in separate cells. This is not unlikely because mammalian BH3-only proteins have been shown to be regulated post-translationally.51 Our data show that KRI-1 is one protein mediating the signalling from DLC-1 to EGl-1 and CED-13. We did not find experimental support for a direct interaction between DLC-1 and KRI-1; however, DLC-1 does regulate the level of KRI-1. Further studies will be required to determine how and where DLC-1 is regulating KRI-1, and which downstream targets are employed in transmitting the apoptotic signal from the somatic cells to the germ cells. Interestingly, it has previously been shown that KRI-1 is expressed in the intestine and pharynx and that it mediates a signal between the reproductive system and the intestine required for longevity because of reduced germline signalling.52 As dlc-1 is also expressed in these tissues, it is tempting to speculate that they might be the site of interaction between DLC-1 and KRI-1, although their interaction also could be purely genetic and cell-nonautonomous.

Our results may also explain why DLC-1 is overexpressed in human breast cancers.37 It is possible that overexpression of DLC-1 could potentially protect cancer cells from undergoing apoptosis. Furthermore, our observation that DLC-1 mediates apoptotic signalling between somatic cells and germ cells validates the importance for cell-nonautonomous signalling. This intertissue communication also has vital roles in other C. elegans life history traits, such as lifespan52 and proliferation and differentiation of the germline.53 Decoding pathways for intertissue communication is also of crucial importance in higher organism such as humans to better understand the interplay and regulation of individual organs required to maintain an intact organism.

Materials and Methods

Strains and culture conditions

All strains were maintained at 20 °C on standard nematode growth medium (NGM) spotted with Escherichia coli strain OP50. The following strains were used: Wild-type N2, MD701 (bcIs39[P(lim-7)ced-1::GFP +lin-15(+)]), MT1522 ced-3(n717), ced-6(tm1826), MT4770 ced-9(n1950), FX536 ced-13(tm536), NL2098 rrf-1(pk1417), RB798 rrf-1(ok589), NL2550 ppw-1(pk2505), NL3511 ppw-1(pk1425), TJ1 cep-1(gk138), CA388 pch-2(tm1458), MT10430 lin-35(n745), RB2026 gla-3(ok2684), MT8735 egl-1(n1084n3082), ced-5(tm1950), egl-1(n1084n3082);ced-13(tm536), EG6699 (ttTi5605 II; unc-119 (ed3) III; oxEx1578), pmk-3(ok169), pmk-1(km25), sir-2.1(ok434), CF2052 kri-1(ok1251), muEx353[Pkri-1::kri-1::gfp; odr-1::rfp], OLS400 aarSi1[Pdlc-1::DLC-1::GFP cb-unc-119(+)] II and OLS401 aarSi2[Pdlc-1::DLC-1::GFP cb-unc-119(+)] II.

Double mutants were made by crossing MD701 males with hermaphrodites of the desired phenotype. For cep-1;ced-1::GFP, pch-2;ced-1::GFP and gla-3;ced-1::GFP, the homozygous F2s were selected by using standard PCR (see Supplementary Table S1 for primers) and GFP expression. ced-3;ced-1::GFP was made by using the marker unc-26(e1196). The marker was first crossed to MD701, and F2s were selected by their Unc phenotype and GFP expression. This strain was then crossed to ced-3, and F2s were selected for GFP expression and non-Unc phenotypes. To validate the cep-1 mutant, we used IR to introduce DNA damage-induced apoptosis. As expected, the cep-1 mutant had no apoptotic cells in the germline after IR (Supplementary Figure S10).

Generation of transgenic strains by MosSCI

The plasmid containing Pdlc-1::dlc-1::gfp was generated by using standard Gateway techniques (Invitrogen, Naerum, Denmark). pENTRY clones for the dlc-1 promoter and open reading frame (ORF) were generated by using PCR products amplified with Gateway and gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table S1). The vector pJA256 (Addgene, Cambridge, MA, USA) was used as pENTRY clone for GFP. The Gateway destination vector was pCFJ150 (Addgene) containing an unc-119 rescue fragment.

MosSCI was performed as described54 using direct insertion based on injection of unc-119 animals (EG6699 strain) with an injection mix comprised of the plasmids (all from Addgene): pCFJ150 containing Pdlc-1::dlc-1::gfp (final conc. 15 ng/μl), pCFJ601 (final conc. 50 ng/μl), pMA122 (final conc. 10 ng/μl), pGH8 (final conc. 10 ng/μl), pCFJ90 (final conc. 2.5 ng/μl) and pCFJ104 (final conc. 5 ng/μl). Selection was based on peel-1 toxin, wild-type movement, absence of mCherry markers and presence of GFP.

Two independent lines OLS400 and OLS401 were created, and expression of full-length DLC-1 was confirmed by using western blotting with an antibody against GFP. The lines were subsequently back-crossed to wild-type N2 four times to eliminate background mutations.

RNAi

The RNAi clone against dlc-1(T26A5.9) was from the OpenBiosystems RNAi Library (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RNAi clones against dlc-2, dlc-3, dlc-4, dlc-5 and dlc-6 were generated by standard cloning techniques and inserted into pL4440 and expressed by HT115 cells. All RNAi clones were verified by sequencing (See Supplementary Table S1 for primers). RNAi was performed by feeding on NGM plates containing 1 mM isopropyl thiogalactoside and ampicillin (100 μg/ml).55 Worms feed HT115 bacteria containing an empty pL4440 vector (ctrl RNAi) were used as controls.

In all germline apoptosis assays following RNAi against dlc-1, apoptosis was scored in the first generation on RNAi. For assays with RNAi against dlc-2–6, apoptosis was scored both in first and second generation on RNAi to eliminate maternal rescue. For dhc-1 RNAi, animals were treated with RNAi from L4 and apoptosis was scored 48 h later.

For developmental apoptosis in the head of L1 larvae on dlc-1 RNAi, eggs were picked onto dlc-1 RNAi plates and their progeny was scored for apoptosis.

Quantification of apoptosis

Cells undergoing apoptosis were distinguished from normal cells as refractile, button-like discs by using DIC microscopy (Zeiss Axiophot Microscope equipped with a Micropublisher 3.3 RTV Qimaging camera) as described.56 Alternatively, the CED-1::GFP (Plim-7ced-1::GFP, bcIs39) reporter was used to score apoptotic cells using fluorescence microscopy (Leica DNI300B microscope equipped with an Olympus DP72 camera) as previously described.19 Briefly, worms were synchronized as eggs and apoptosis was scored after 72 and 96 h using Plim-7ced-1::GFP and/or DIC. Worms for DIC were grown at 20 °C, whereas Plim-7ced-1::GFP worms were grown at 25 °C to obtain stronger expression of GFP. Worms were anesthetised in 5 mM levamisole in S-basal (0.1 M NaCl, 0.05 M H2PO4 (pH 6)) and mounted on 2% agarose pads. For DNA damage-induced apoptosis, hermaphrodites were synchronised as L4 and exposed to 60, 90 or 120 Gy using a 137Cs source (dose rate: 2 Gy/min). Germ cell apoptosis was scored 24-h post treatment. For quantification of developmental apoptosis, freshly hatched L1 larva was anaesthetised in 100 mM levamisole in S-basal and mounted on 2% agarose pads.

Quantification of KRI-1::GFP expression Pictures of individual worms were taken with equal exposure time for ctrl and dlc-1(RNAi) worms. Pictures were converted to grey-scale and analysed by mean grey value in ImageJ (Rasband, W. S., Image J, US NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). Twenty worms were analysed for each experiment and condition.

Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts and detection of CEP-1

Extracts with minor modifications were prepared as described.57 Approximately 10 000 rrf-3 worms were grown from eggs to adulthood on dlc-1 or empty vector RNAi plates. Worms were washed three times in S-basal. Three microlitre Extraction Buffer (10 mM Hepes, pH 7.1, 5 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), Complete Protease inhibitor Cocktail Tablets (Roche Applied Science, Hvidover, Denmark)) was added before the worms were pelleted by centrifugation. The pellet was resuspended in 0.5 volumes of Extraction Buffer and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. The frozen worms were grinded in liquid nitrogen in a pre-chilled mortar and dissolved in 3 ml Extraction Buffer and homogenised (10 strokes) in a Wheaton stainless steel tissue grinder (24–7). Samples were spun 10 min, 18 000 g in 50 ml tubes. The supernatant (cytoplasmic fraction) was frozen in liquid nitrogen. The pellet was washed twice in 500 μl Extraction buffer and then dissolved in 300 μl Nuclear Extraction Buffer (Extraction Buffer with 500 mM NaCl) and incubated for 30 min, at 4 °C on a roller table. After centrifugation for 10 min, at 18 000 g in 50 ml tubes at 4 °C, the supernatant (nuclear fraction) was frozen in liquid nitrogen. Bio-Rad (Copenhagen, Denmark) sample buffer and reducing agent were added to 15 μl of the samples, boiled for 5 min before being fractionated on Bio-Rad CriterionXT precast gels (12%) and electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane using a Bio-Rad Trans-blot cell and subsequently incubated with 2% skim milk in 1 × phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Membranes were probed with primary antibody followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody. HRP was visualised using Amersham ECL plus detection systems (GE Healthcare, Brøndby, Denmark). Presence of CEP-1 in the extracts was detected with western blotting (standard protocol) using a rabbit anti-cep-1 (cN-18) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) and HRP-conjugated swine anti-rabbit antibody (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) as secondary antibody. An anti-actin antibody (JLA20, Calbiochem, Merck Chemicals, Hellerup, Denmark) was used as control for equal loading.

Ionising radiation

Hermaphrodites were synchronized at the L4 stage and irradiated with 90 Gy using a 137Cs source (dose rate: 2 Gy/min). After radiation, the worms were transferred to fresh plates. Twenty-four hours post radiation, worms were washed in S-basal and then snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at −80 °C.

Quantitative real-time PCR

For RNA isolation, Trizol (Invitrogen) and chloroform extraction were performed using Phase Lock Gel Heavy 2 ml spin columns (5prime, VWR) followed by isopropanol precipitation. The quality of the RNA was assessed using gel electrophoresis and the concentration was measured using a NanoDrop 1000 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). One microgram of total RNA was reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-rad) following the manufacturer's protocol. Gene-specific qRT-PCR using cDNA, appropriate primers and Power SYBRGreen PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Naerum, Denmark), was performed on a Stratagene MX3000P machine (La Jolla, CA, USA). All samples were run in technical triplicates. Water was used as negative control. All primers were designed to span exon–exon boundaries (See Supplementary Table S1 for primers). Test gene CT values were normalised to either act-1 (dlc-1, egl-1 and ced-13) or pmp-2 (lin-35 and ced-9) CT values. Relative expression levels were calculated by using the Pfaffl method.58

Mammalian two-hybrid system

Experiments were performed based on the Checkmate Mammalian Two-Hybrid system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). C. elegans KRI-1 (isoform a) and DLC-1 were cloned from whole-worm cDNA using standard cloning techniques (See Supplementary Table S1 for primers). KRI-1 was inserted into the pACT vector, and DLC-1 was inserted into both the pACT and pBIND vectors. HEK293T cells were seeded in 24-well plates with a density of 1.4 × 105 cells per well. Next day the cells were transfected at 70–90% confluence with 50 ng GFP vector, 150 ng pG5luc, 150 ng pACT (with appropriate insert), 150 ng pBIND (with appropriate insert) and 1 μl lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies, Naerum, Denmark) in 50 μl DMEM serum-free medium (Life Technologies) per well. After 24 h, the medium was refreshed. Fourty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were lysed, and 50 μl of lysate were transferred to 96-well plates. GFP fluorescence was measured using a Perlkin Elmer Universal Microplate Analyzer Fusion-Alpha FPHT. Fourty microlitre luciferase (Promega) was added to each well, and fluorescence was measured in an Enspire 2300 Multi label Reader. Background levels from empty cells were subtracted and luciferase/GFP was plotted as binding efficiency. All measurements were run in technical triplicates. Non-transfected cells, cells transfected with either pACT or pBIND without insert or both were used as negative controls.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Olsen lab, Dr. MK Lund, Dr. MK Larsen and Dr. M Hansen for their helpful discussions and feedback on the manuscript. For help with the mammalian two-hybrid system, we thank Dr. D Bhaumik. ced-5(tm1950) was obtained from Professor Mitani (Tokyo, Japan). egl-1(n1084n3082);ced-13(tm536) was kindly provided by Professor Shaham (The Rockefeller University, New York, NY, USA). muEx353[Pkri-1,kri-1::gfp; odr-1::rfp] was kindly provided by Professor Kenyon (UCSF, CA, USA). All other nematode strains used in this work were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the NIH National Center for Research Resources (NCRR). THM was supported by GSST, AO was supported by the Danish Research Council FNU (272–07–0162), The Danish Agency for Science, Technology and Innovation (2136–08–0007), The Interdisciplinary Research Consortium on Geroscience (UL1 RR024917), The Novo Nordic Foundation and The Lundbeck Foundation (R9-A968).

Glossary

- C. elegans

Caenorhabditis elegans

- DLC-1

dynein light chain 1

- IR

ionising radiation

- RNAi

RNA interference

- GFP

green-fluorescent protein

- DIC

differential interference contrast

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- gf

gain-of-function

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- Gy

grey

- Unc

uncoordinated

- ORF

open reading frame

- NGM

nematode growth medium

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- DMEM

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Disease website (http://www.nature.com/cddis)

Edited by M Piacentini

Supplementary Material

References

- Fadeel B, Orrenius S. Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in human disease. J Intern Med. 2005;258:479–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipfner DR, Cohen SM. Connecting proliferation and apoptosis in development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:805–815. doi: 10.1038/nrm1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston JE, Schierenberg E, White JG, Thomson JN. The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1983;100:64–119. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston JE, Horvitz HR. Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1977;56:110–156. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumienny TL, Lambie E, Hartwieg E, Horvitz HR, Hengartner MO. Genetic control of programmed cell death in the Caenorhabditis elegans hermaphrodite germline. Development. 1999;126:1011–1022. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.5.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J, Shaham S, Ledoux S, Ellis HM, Horvitz HR. The C. elegans cell death gene ced-3 encodes a protein similar to mammalian interleukin-1 beta-converting enzyme. Cell. 1993;75:641–652. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90485-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J, Horvitz HR. The Caenorhabditis elegans cell death gene ced-4 encodes a novel protein and is expressed during the period of extensive programmed cell death. Development. 1992;116:309–320. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengartner MO, Horvitz HR. C. elegans cell survival gene ced-9 encodes a functional homolog of the mammalian proto-oncogene bcl-2. Cell. 1994;76:665–676. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90506-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis HM, Horvitz HR. Genetic control of programmed cell death in the nematode C. elegans. Cell. 1986;44:817–829. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartner A, Boag PR, Blackwell TK.Germline Survival and Apoptosis (September 4, 2008), WormBook (ed.) The C. elegans Research Community, WormBook,doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.145.1 , http://www.wormbook.org . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Derry WB, Putzke AP, Rothman JH. Caenorhabditis elegans p53: role in apoptosis, meiosis, and stress resistance. Science. 2001;294:591–595. doi: 10.1126/science.1065486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher B, Hofmann K, Boulton S, Gartner A. The C. elegans homolog of the p53 tumor suppressor is required for DNA damage-induced apoptosis. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1722–1727. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00534-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartner A, Milstein S, Ahmed S, Hodgkin J, Hengartner MO. A conserved checkpoint pathway mediates DNA damage--induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in C. elegans. Mol Cell. 2000;5:435–443. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80438-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher B, Schertel C, Wittenburg N, Tuck S, Mitani S, Gartner A, et al. C. elegans ced-13 can promote apoptosis and is induced in response to DNA damage. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:153–161. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Johnson RW, Park D, Chin-Sang I, Chamberlin HM. Somatic gonad sheath cells and Eph receptor signaling promote germ-cell death in C. elegans. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:1080–1089. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S, Greiss S, Gartner A, Derry WB. Cell-nonautonomous regulation of C. elegans germ cell death by kri-1. Curr Biol. 2010;20:333–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumienny TL, Hengartner MO. How the worm removes corpses: the nematode C. elegans as a model system to study engulfment. Cell Death Differ. 2001;8:564–568. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RE, Jacobson DM, Horvitz HR. Genes required for the engulfment of cell corpses during programmed cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1991;129:79–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/129.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Hartwieg E, Horvitz HR. CED-1 is a transmembrane receptor that mediates cell corpse engulfment in C. elegans. Cell. 2001;104:43–56. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu QA, Hengartner MO. Candidate adaptor protein CED-6 promotes the engulfment of apoptotic cells in C. elegans. Cell. 1998;93:961–972. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81202-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su HP, Nakada-Tsukui K, Tosello-Trampont AC, Li Y, Bu G, Henson PM, et al. Interaction of CED-6/GULP, an adapter protein involved in engulfment of apoptotic cells with CED-1 and CD91/low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP) J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11772–11779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109336200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YC, Horvitz HR. The C. elegans cell corpse engulfment gene ced-7 encodes a protein similar to ABC transporters. Cell. 1998;93:951–960. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddien PW, Horvitz HR. CED-2/CrkII and CED-10/Rac control phagocytosis and cell migration in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:131–136. doi: 10.1038/35004000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YC, Tsai MC, Cheng LC, Chou CJ, Weng NY. C. elegans CED-12 acts in the conserved crkII/DOCK180/Rac pathway to control cell migration and cell corpse engulfment. Dev Cell. 2001;1:491–502. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Caron E, Hartwieg E, Hall A, Horvitz HR. The C. elegans PH domain protein CED-12 regulates cytoskeletal reorganization via a Rho/Rac GTPase signaling pathway. Dev Cell. 2001;1:477–489. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YC, Horvitz HR. C. elegans phagocytosis and cell-migration protein CED-5 is similar to human DOCK180. Nature. 1998;392:501–504. doi: 10.1038/33163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallee RB, Sheetz MP. Targeting of motor proteins. Science. 1996;271:1539–1544. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5255.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison A, King SM. The molecular anatomy of dynein. Essays Biochem. 2000;35:75–87. doi: 10.1042/bse0350075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaisberg EA, Koonce MP, McIntosh JR. Cytoplasmic dynein plays a role in mammalian mitotic spindle formation. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:849–858. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.4.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzbaur EL, Vallee RB. DYNEINS: molecular structure and cellular function. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1994;10:339–372. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.10.110194.002011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puthalakath H, Huang DC, O'Reilly LA, King SM, Strasser A. The proapoptotic activity of the Bcl-2 family member Bim is regulated by interaction with the dynein motor complex. Mol Cell. 1999;3:287–296. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80456-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannakakou P, Sackett DL, Ward Y, Webster KR, Blagosklonny MV, Fojo T. p53 is associated with cellular microtubules and is transported to the nucleus by dynein. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:709–717. doi: 10.1038/35036335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo KW, Kan HM, Chan LN, Xu WG, Wang KP, Wu Z, et al. The 8-kDa dynein light chain binds to p53-binding protein 1 and mediates DNA damage-induced p53 nuclear accumulation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8172–8179. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411408200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Hollander P, Kumar R. Dynein light chain 1 contributes to cell cycle progression by increasing cyclin-dependent kinase 2 activity in estrogen-stimulated cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5941–5949. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapali P, Radnai L, Süveges D, Harmat V, Tölgyesi F, Wahlgren WY, et al. Directed evolution reveals the binding motif preference of the LC8/DYNLL hub protein and predicts large numbers of novel binders in the human proteome. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18818. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbar E. Dynein light chain LC8 is a dimerization hub essential in diverse protein networks. Biochemistry. 2008;47:503–508. doi: 10.1021/bi701995m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadlamudi RK, Bagheri-Yarmand R, Yang Z, Balasenthil S, Nguyen D, Sahin AA, et al. Dynein light chain 1, a p21-activated kinase 1-interacting substrate, promotes cancerous phenotypes. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:575–585. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsett M, Schedl T. A role for dynein in the inhibition of germ cell proliferative fate. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:6128–6139. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00815-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almendinger J, Doukoumetzidis K, Kinchen JM, Kaech A, Ravichandran KS, Hengartner MO. A conserved role for SNX9-family members in the regulation of phagosome maturation during engulfment of apoptotic cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18325. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloss TA, Witze ES, Rothman JH. Suppression of CED-3-independent apoptosis by mitochondrial betaNAC in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2003;424:1066–1071. doi: 10.1038/nature01920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla N, Dernburg AF. A conserved checkpoint monitors meiotic chromosome synapsis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2005;310:1683–1686. doi: 10.1126/science.1117468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schertel C, Conradt B. C. elegans orthologs of components of the RB tumor suppressor complex have distinct pro-apoptotic functions. Development. 2007;134:3691–3701. doi: 10.1242/dev.004606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kritikou EA, Milstein S, Vidalain PO, Lettre G, Bogan E, Doukoumetzidis K, et al. C. elegans GLA-3 is a novel component of the MAP kinase MPK-1 signaling pathway required for germ cell survival. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2279–2292. doi: 10.1101/gad.384506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiss S, Hall J, Ahmed S, Gartner A. C. elegans SIR-2.1 translocation is linked to a proapoptotic pathway parallel to cep-1/p53 during DNA damage-induced apoptosis. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2831–2842. doi: 10.1101/gad.482608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aballay A, Drenkard E, Hilbun LR, Ausubel FM. Caenorhabditis elegans innate immune response triggered by Salmonella enterica requires intact LPS and is mediated by a MAPK signaling pathway. Curr Biol. 2003;13:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01396-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei B, Wang S, Guo X, Wang J, Yang G, Hang H, et al. Arsenite-induced germline apoptosis through a MAPK-dependent, p53-independent pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:1530–1535. doi: 10.1021/tx800074e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Wu L, Wang Y, Luo X, Lu Y. Copper-induced germline apoptosis in Caenorhabditis elegans: the independent roles of DNA damage response signaling and the dependent roles of MAPK cascades. Chem Biol Interact. 2009;180:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tijsterman M, Okihara KL, Thijssen K, Plasterk RH. PPW-1, a PAZ/PIWI protein required for efficient germline RNAi, is defective in a natural isolate of C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1535–1540. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijen T, Fleenor J, Simmer F, Thijssen KL, Parrish S, Timmons L, et al. On the role of RNA amplification in dsRNA-triggered gene silencing. Cell. 2001;107:465–476. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00576-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song C, Wen W, Rayala SK, Chen M, Ma J, Zhang M, et al. Serine 88 phosphorylation of the 8-kDa dynein light chain 1 is a molecular switch for its dimerization status and functions. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:4004–4013. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704512200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puthalakath H, Strasser A. Keeping killers on a tight leash: transcriptional and post-translational control of the pro-apoptotic activity of BH3-only proteins. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:505–512. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman JR, Kenyon C. Germ-cell loss extends C. elegans life span through regulation of DAF-16 by kri-1 and lipophilic-hormone signaling. Cell. 2006;124:1055–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killian DJ, Hubbard EJ. C. elegans pro-1 activity is required for soma/germline interactions that influence proliferation and differentiation in the germ line. Development. 2004;131:1267–1278. doi: 10.1242/dev.01002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frokjaer-Jensen C, Davis MW, Hopkins CE, Newman BJ, Thummel JM, Olesen SP, et al. Single-copy insertion of transgenes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1375–1383. doi: 10.1038/ng.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmons L, Fire A. Specific interference by ingested dsRNA. Nature. 1998;395:854. doi: 10.1038/27579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedgecock EM, Sulston JE, Thomson JN. Mutations affecting programmed cell deaths in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1983;220:1277–1279. doi: 10.1126/science.6857247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tops BB, Tabara H, Sijen T, Simmer F, Mello CC, Plasterk RH, et al. RDE-2 interacts with MUT-7 to mediate RNA interference in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:347–355. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.