Abstract

Prescription opioid (PO) misuse represents a major health risk for many service members and veterans. This paper examines the pathways to misuse among a sample of US veterans who recently returned from Iraq and Afghanistan to low-income, predominately minority sections of New York City. Recreational PO misuse was not common on deployment. Most PO misusers initiated use subsequent to PO use for pain management, an iatrogenic pathway. However, most PO users did not misuse them. Veterans that misused POs were more likely to have other reintegration problems including drug and alcohol use disorders, traumatic brain injury (TBI), unemployment, and homelessness.

Keywords: drug use disorder, minority, pain management, military personnel, veterans, reintegration, mental health

INTRODUCTION

Widespread prescription opioid (PO) misuse among military personnel, veterans, and the broader civilian has raised great concern (Bray & Hourani, 2007; Bray et al., 2010; CDCP, 2011; Institute of Medicine, 2012; Larance, Degenhardt, Lintzeris, Winstock & Mattick, 2011; Manchikanti, 2007; Manchikanti et al., 2012; Manchikanti & Singh, 2008; ONDCP, 2011). PO misuse is of particular concern among service members and veterans because it is linked to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and heavy alcohol use and because of its association with drug dependence, overdose, suicides, and accidents (Bohnert, Roeder, & Ilgen, 2010; Bray, Olmsted, & Williams, 2012; U.S. Army, 2012; Wu, Lang, Hasson, Linder, & Clark, 2010). Ongoing research now suggests that some service men and women develop drug use disorders involving POs while in the military or soon after discharge to cope with injuries sustained during combat and psychological and physical ailments that can be exacerbated during the civilian readjustment process (Bray & Hourani, 2007; Bray et al., 2006; Finley, 2011; Goebel et al., 2011; Heltemes, Dougherty, MacGregor, & Galarneau, 2011). The risk of PO misuse may be heightened for veterans due to the challenges posed by the readjustment experience, the lack of formal military controls, greater access to diverted opioids (Goebel et al., 2011), and the lack of routine drug testing or demotion or dishonorable discharge which may be consequences of substance misuse for military personnel.

This paper examines the initiation of PO use and misuse in the military as well as use, misuse, and associated reintegration problems after separation of veterans recently returned from the US conflicts occurring since 9/11/2001 known as Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF, primarily taking place in Afghanistan) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF). Participants were recruited using Respondent-Driven Sampling (RDS), an innovative procedure that allows researchers to calculate unbiased estimates of the characteristics of a target population. This analysis is part of a larger study of the reintegration challenges faced by OEF/OIF veterans returning to low-income primarily minority neighborhoods in New York City. Accordingly, the estimates in this paper are not representative of all recent veterans but are representative of a particular subpopulation of veterans, the target population, who are of particular interest due to the specific challenges they face.

We conceptualize three potential pathways to PO misuse for members of our sample: iatrogenic, opportunistic, and recreational. In our conceptualization, each of these pathways emphasizes distinct elements of the drug use experience that Norman Zinberg referred to as drug, set, and setting (Zinberg, 1986). These three nested and comprehensive domains operate together and affect the substance use experiences and potential pathways to dependence. Zinberg explained that the action of a “drug” describes the properties that affect an individual’s body. Today, we understand that much of this effect is manifest across the dopamine pathway. “Set” is a user’s expectations or mindset surrounding the consumption of a drug that further influences the experience. A user’s set is influenced by their personality and internal states of mind and brings into consideration such psychological elements as depression, happiness, stress, and anxiety. “Setting” includes the environmental, social, and cultural context in which substance use takes place. The substances available and the significance society and the individual come to attach to the substances both influence a person’s experience or relationship with a substance. In this manner, drug experiences are context-dependent.

As regards the recreational pathway, for many, the military experience is associated with masculine values of extremes, partying hard and consuming large quantities of alcohol regularly, a consumption pattern reinforced by a military culture that promotes shared norms and behaviors such as drinking large quantities of alcohol (Barrett, 2007; Finley, 2011; Holyfield, 2011; Poehlman et al., 2011). While on deployment, access to alcohol can be limited and stress is high. The omnipresent threat of roadside bombs, improvised explosive devices, and the potential of being shot by people in the local population permeates the boredom of waiting and otherwise routine tedious activities (Ender, 2009; Madaus, Miller II, & Vance, 2009). Many of the prescription drugs available as medical supplies while on deployment such as POs have psychoactive properties and can be diverted for recreational use. This perspective suggests that the initiation of PO misuse for some service members may be associated with the setting and the prevailing sociocultural activity.

Alternatively, there is the potential for iatrogenic initiation of PO use with potential for misuse. POs are effective pain relievers and are widely used in the military today to deal with injuries. This usage and the resulting problems are reminiscent of the experiences surrounding morphine use during the US Civil War of the 1860s (Bennett & Golub, 2012; Bergen-Cico, 2011; Courtwright, 2001; Skidmore & Roy, 2011). The use of morphine had become popular during the 19th Century, especially with the invention of the hypodermic needle that speeds drugs into the bloodstream. Morphine was widely used during the Civil War as part of the treatment for battlefield injuries. However, morphine use can lead to dependence and did during the late 1900s—especially among Civil War veterans. Similarly, OxyContin, the long-acting and potent extended-release formulation of the opioid oxycodone, hit US markets in the late 1990s and became the best-selling nongeneric pain reliever by 2001 (International Narcotics Control Board, 2009). The time-release coating on the product was designed to limit the psychoactive properties of the drug and reduce its potential for dependence and misuse. However, PO-related problems still increased dramatically among civilians and service members. As of 2008, poisoning exceeded motor vehicle accidents as the leading cause of injury deaths in the US civilian population; most of the deaths were drug-related and most of the rapid increase in drug poisonings in the 2000s is attributable to POs (Warner, Chen, Makuc, Anderson, & Miniño, 2011). As of 2009, more OEF/OIF veterans had died at their own hands from suicide and lethal drug overdoses than from combat itself (U.S. Army, 2010). POs have been one major contributor to this tragedy. Liberal practices of prescribing opioids such as OxyContin, Percocet, and Vicodin for pain management have led some service members to problematic use and subsequent dependence. This iatrogenic pathway to PO misuse emphasizes the drug itself and its characteristics in the initiation of PO use and subsequent misuse and dependence. Bray et al. (2012) recently documented that active duty military service members who are prescribed prescription pain relievers are the most likely to misuse POs, as are those manifesting PTSD, or are heavy drinkers.

The opportunistic pathway to PO misuse represents a hybrid pathway. As Bray et al. (2012) have shown, PO misuse may be more likely for veterans who sustained injuries and were prescribed POs for pain management than for those service members who were not injured and thus did not receive POs. But not all veterans who had been prescribed POs misused them indicating there were other factors involved. One possibility would be a prior predisposition for recreational use that might be indicated by prior involvement with partying and heavy use of drugs and alcohol. Potentially, injured personnel with such a disposition may come to enjoy the opportunity associated with the added high available from the medicines prescribed to them, especially when mixed with alcohol or another prescription drug. This pathway represents a hybrid in that the initiation is iatrogenic (rooted in medical use), however, recreational interest in the drug is the predisposing factor distinguishing those that become misusers from those that limit their use to the prescribed purpose.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

Data for this study comes from the Veteran Reintegration, Mental Health, and Substance Abuse in the Inner-City Project sponsored by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). This study is examining the experiences of OEF/OIF veterans returning to low-income predominately minority sections of NYC. Participants were required to have been discharged within the past two years although some had been separated slightly longer. The project recruited 269 veterans between February 2011 and April 2012.

The project used RDS so that unbiased estimates for the target population could be obtained. RDS is similar to but represents a major advancement over snowball sampling (Heckathorn, 1997, 2002). Both RDS and snowball sampling are network-based approaches that start with a few members of the target population (in this case veterans returning to innercity New York) called seeds. The seeds are then asked to recruit other members of the target population that are called referrals. In this study, participants were provided with a $20 incentive payment for each referral they provided who completed an interview. The referrals of the initial seeds are referred to as wave 1. The wave 1 referrals were then asked to recruit more respondents (wave 2) and so forth. As the process continues, the number of recruits can potentially snowball, i.e., increase exponentially. Through this process, the researcher uses the respondents’ own networks to efficiently access members of the target population which greatly reduces time searching for potential subjects. The approach is particularly useful when a complete enumeration of a sampling frame is not readily available.

The RDS procedure is particularly appropriate when the target population is highly networked and social. A major requirement of the network for the target population is irreducibility, that all potential participants know some other members of the target population and that network chains exist that eventually link any participant to any other participant. Thus, RDS could not be used to study every topic. Ideally, membership in the target population should be broadly known at least among members of the target population and possibly serve as a basis for social interaction. To date, RDS has mostly been used to study specific sex and drug use behaviors (Abdul-Quadar et al., 2006; Heckathorn, 1997; Iguchi et al., 2009; Johnson et al., 2009; Lansky et al., 2007; Rusch et al., 2009; Shahmanesh et al., 2009; Wang, Falck, Li, Rahman, & Carlson, 2007; Wattana et al., 2007) but has also been used to study jazz musicians (Jeffri, 2003) and Cornell University undergraduate students (Wejnert & Heckathorn, 2008). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to use RDS to study veterans.

Potential participants completed an informed consent procedure where the benefits and possible risks of participation were discussed prior to an interview. Interviews were held in person in a mutually convenient private location. Participants were paid $40 for completing an interview. All recruitment, interview, and data management procedures were approved by the project’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Participants were asked about legal and illegal substance use during four periods across the military-veteran life course: just before entering the military, while in the military but not on the most recent deployment, during the last deployment, and in the past 30 days which would be after separation from the military. Participants were asked to report how frequently they used each substance during each period: never, rarely (once or twice), occasionally (from time-to-time, but not all the time), or regularly (every day or nearly every day). Questions were patterned after those appearing in the NSDUH (SAMHSA, 2010). Participants were asked about the use of prescription drugs that were not prescribed or that were taken for the experience or feeling it caused. Participants were also asked about prescription drug use while deployed and after separation for any of the following purposes: pain, anxiety/stress, sleep, alertness, to enjoy the effect with others, or to maintain a habit (to feel normal). The most common prescription painkillers reported were the POs Percocet and Vicodin. Accordingly, we use the term PO use to refer to taking opioid painkillers for pain and the term PO misuse to refer to recreational use of opioid painkillers.

Binge drinking was defined as having five or more drinks on a single occasion for a male and four or more for a female. Heavy drinking was defined as binge drinking on five or more out of 30 days as used in the National Survey on Drug use and Health or NSDUH (SAMHSA, 2010). Alcohol use disorder (AUD) and drug use disorder (DUD) were assessed using questions from the NSDUH which are based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition or DSM-IV (SAMHSA, 2010). Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) was assessed using the same screener employed by the U.S. Military on their Post-Deployment Health Assessment or PDHA that identifies a traumatic event and related memory consequences (U.S. Department of Defense, 2008). We did not differentiate between mild and more severe TBI. Graham and Cardon (2008) found that mild TBI was more likely to be associated with chronic substance abuse and that there was a direction of causality that went both ways. PTSD was assessed using the PTSD Checklist designed for use for the military or PCL-M using a standard cut point of 50 and including at least one intrusion, three avoidance, and two hyperarousal items (Blanchard, Jones-Alexander, Buckley, & Forneris, 1996; Karney, Ramchand, Osilla, Caldarone, & Burns, 2008). Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) was assessed using the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire screener or PHQ-9 (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001). MDD was identified as having at least five of the nine symptoms occurring on at least half of the past 30 days and one of the symptoms so identified was either anhedonia or depressed mood. In addition, functional impairment was also required to classify a person as having MDD.

Analyses

RDS assumes that the referral probabilities within a population form a Markov chain (Heckathorn, 1997). That is that once steady state is achieved after several rounds of referral that there is a steady probability that a participant with one characteristic (e.g., male) will refer a participant with another characteristic (e.g., female). The Markov property requires that the probability of referral depends solely on the characteristics of the referring participant and not on any other characteristic of the referral chain leading up to that point. Presuming the Markov property holds and that the network is irreducible, the referral probability data can be used to estimate the prevalence of persons with a given characteristic within the target population. This study used the RDS Analysis Tool or RDSAT version 6.0.1 available from the RDS website (Heckathorn, 2007, 2012). RDSAT estimates the prevalence of characteristics and uses a bootstrap procedure to estimate standard errors (SEs). The SEs were used in a conventional z-test to examine whether differences of interest were statistically significant.

RESULTS

Participant Demographics

Table 1 presents both the sample characteristics and the target population estimates calculated using RDSAT. The table indicates that the two sets of estimates often differed. Blacks were underrepresented in the sample by 13% (1 –61.0 ÷ 70.2), veterans age 19–29 were overrepresented by 14%, members of the reserves/guards were overrepresented by 115%, and veterans with three or more deployments were overrepresented by 54%. However, the only statistically significant difference was associated with military component. So, it is possible that with a larger sample the differences between the sample characteristics and the target population would be smaller. Most of the target population was male (88%), Black (70%), age 19–29 (51%), had served in the army (64%), deployed only once (59%), and last served in Iraq (75%).

TABLE 1.

A comparison of sample characteristics with RDS estimates of prevalence rates for the target population

| Demographics | Sample characteristics as % (conventional) | Target population estimates as % (using RDSAT) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 85.1 | 87.8 |

| Female | 14.9 | 12.2 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Black | 61.0 | 70.2 |

| White (non-Hisp) | 19.0 | 13.0 |

| Hispanic (non-AA) | 16.0 | 9.5 |

| Other | 4.1 | 7.3 |

| Age | ||

| 19–29 | 58.4 | 51.4 |

| 30–39 | 30.5 | 34.9 |

| 40+ | 11.2 | 13.6 |

| Military branch | ||

| Army | 62.1 | 64.4 |

| Marines | 17.8 | 18.9 |

| Navy | 15.2 | 12.6 |

| Air Force/Coast Guard | 4.8 | 4.1 |

| Component | ||

| Active duty | 78.1 | 89.8** |

| Reserves/Guard | 21.9 | 10.2** |

| Last deployment | ||

| OEF (Afghanistan) | 19.0 | 17.9 |

| OIF (Iraq) | 71.0 | 75.0 |

| Other | 10.0 | 7.1 |

| No. of deployments | ||

| 0 | 2.2 | 3.6 |

| 1 | 54.3 | 58.9 |

| 2 | 28.6 | 28.2 |

| 3+ | 14.5 | 9.4 |

Difference between sample characteristic and estimate significant at α = .01 level.

Substance Use Over the Military-Veteran Career

Table 2 identifies how substance use varied substantially over the military-veteran career for the target population. Prior to entering the military, PO misuse (0.4%) was exceeding uncommon among members of the target population. Heroin and injection drug use were even less common. The majority of the target population (55%) smoked marijuana. This is consistent with previous studies that found that persons coming of age during the 2000s were members of the Marijuana/Blunts Generation and avoided crack cocaine and heroin which had been common among those coming of age decades earlier (Golub, Johnson, Dunlap, & Sifaneck, 2004). None of the members of the target population used crack (0%) and almost none used heroin (0.2%). A substantial portion reported using powder cocaine, but only 2 out of 22 study participants reported using it regularly. (Note: The count of participants is provided here because there were too few regular powder cocaine users to estimate the prevalence for the target population with RDSAT.) Alcohol use (68%) was more popular than marijuana use, although only 16% of the target population were heavy drinkers.

TABLE 2.

Variation in use of various substances over the military-veteran life course

| Before military | Percent that used during perioda

|

Past 30 days | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In military | Last deployment | |||

| Substances used recreationally | ||||

| Painkillers | 0.4 | 1.6 | 6.3b | 7.3c |

| Heroin | 0.2 | 0.0† | 0.0† | 0.7† |

| Injected | 0.1 | 0.0† | 0.4† | 0.7† |

| Alcohol | 68.4 | 80.0* | 28.3** | 60.2** |

| Binge drinking | 41.9 | 61.9** | 20.2** | 35.7** |

| Heavy drinking | 16.2 | 42.6** | 5.6** | 15.7** |

| Marijuana | 54.9 | 20.0** | 8.8* | 33.7** |

| Powder cocaine | 10.0 | 5.0 | 1.5 | 3.8 |

| Heroin | 0.2 | 0.0† | 0.0† | 0.7† |

| Injected | 0.1 | 0.0† | 0.4† | 0.7† |

| Prescription drug use for pain | 33.1 | 30.1 | ||

| Types of PO users (as a % of all PO users) | ||||

| For pain only | 87.3† | 77.5 | ||

| For pain + misuse | 9.3† | 15.2 | ||

| For misuse only | 3.4† | 7.3 | ||

Difference with previous time period significant at agr; = .05 level.

Difference with previous time period significant at agr; = .01 level.

All percentages were calculated using RDSAT, except where explicitly noted.

RDSAT could not estimate this proportion due to nonconnectivity. The sample percentage is provided instead.

The difference from before the military to deployment was significant at agr; = .05 level.

The difference from before the military to past-30-days was significant at agr; = .01 level.

Once in the military, PO misuse (1.6%) was only slightly more common. Alcohol was clearly the drug of choice. Marijuana use plunged to 20% of the target population. Alcohol use increased moderately to 80%, but heavy alcohol use increased substantially to 43%.

Alcohol and illegal drug use decreased substantially while deployed. Marijuana use decreased to 9%. Any alcohol use decreased to 28% and heavy drinking to a low of 6% while deployed. While deployed, 6% of the target population misused POs. This represents a substantial number of members of the target population involved with an illegal activity that could have health consequences. However, in other respects, the rate of PO misuse was lower than might have been expected. One possible pathway to PO misuse hypothesized was the recreational pathway, as a substitute for heavy drinking. The 6% of the target population that misused POs while deployed was much lower than the 42% that drank heavily in the military prior to deployment. The iatrogenic and opportunistic pathways hypothesized that service members receiving POs for pain while deployed would be at potential risk for misuse. The rate of misuse (6%) was much lower than the rate of use for pain (33%). Indeed, most PO users (87%) used their drugs for pain management only; 9% used them for pain and also misused them; and only 3% misused POs and did not take them for pain.

About as many veterans (7%) reported misusing POs after separation as while deployed. After separation, many members of the target population appeared to return to their premilitary substance use. Many more (34%) smoked marijuana than used while in the military, but not as many as prior to entering the military. Heavy drinking (16%) also decreased from the high levels in the military to the same level as prior to entering the military.

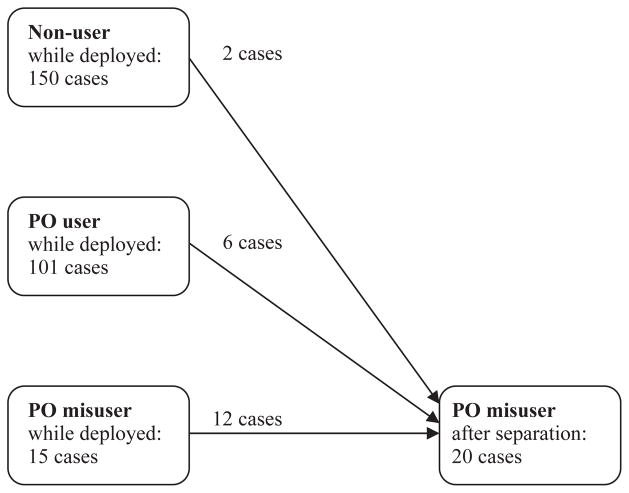

Pathways to PO Misuse

Figure 1 examines the three alternative pathways to PO misuse. The recreational pathway starts with having been a partier in the military. A respondent’s report of heavy drinking in the military was used as a proxy for partying because alcohol was the most common substance reported during this period. The recreational pathway differs from the opportunistic pathway by whether a service member received POs for pain prior to misusing them. The iatrogenic pathway involves PO use for pain leading to eventual misuse. This analysis uses participants’ reports of any PO use and misuse while deployed. For those that had used POs for pain, it was assumed that this experience preceded misuse. However, it is possible that misuse preceded use; a service member who had been misusing POs without a prescription could have subsequently sustained an injury or alternatively complained of a nonexistent injury as a plausible excuse in order to receive POs for pain. To the extent that this was the case, some of the participants identified as having followed the opportunistic and iatrogenic pathways may have actually followed the recreational pathway.

FIGURE 1.

Potential pathways to prescription opioid misuse on deployment.

Figure 1 indicates the number of participants that followed each pathway. (Because of the small number of cases involved, we present the count of cases for this diagram as opposed to percentages.) Overall, 15 participants reported PO misuse. Most of them (11 cases) had used POs for pain: six followed the opportunistic pathway and five followed the iatrogenic pathway. This strongly suggests that PO misuse was rooted in obtaining POs for pain as opposed to primarily for partying. Very few participants followed the recreational pathway. Only two participants followed the pure pathway involving first heavy drinking in the military and then PO misuse on deployment. An additional two participants reported PO misuse without having first been a heavy drinker. We hypothesize two possible explanations for these exceptions: either they became partiers after they were on deployment or our proxy measure of being a partier (heavy drinking) did not capture these two cases who may have used somewhat less frequently or used other substances such as marijuana for partying.

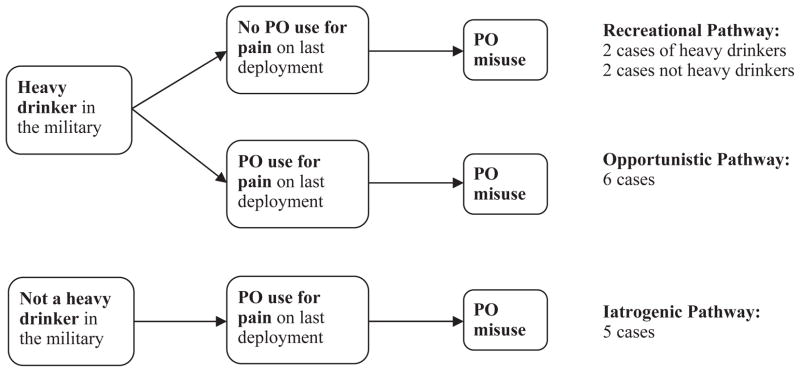

Continuity of PO Misuse From Deployment to Civilian Life

Figure 2 illustrates the continuity of PO misuse from while deployed to the time after separation. Most of the service members that misused POs while deployed continued to misuse them after separation (12 of 15). Only three discontinued misuse. This finding is consistent with the possibility that most PO misusers had developed a habit that was not limited to their deployment experience and that some may have become physically dependent and continued practices of PO misuse. Not all of the PO misusers after separation had started while deployed. Six participants had been using POs for pain while deployed and started misusing them after separation. Their experiences are consistent with the iatrogenic pathway to PO misuse (see Figure 1). Two additional participants who had not used POs while deployed became PO misusers after separation.

FIGURE 2.

Continuity of PO misuse from deployment to beyond separation.

PO Misuse and Reintegration

Table 3 presents the association between PO use and misuse after separation with mental health and social reintegration. Overall, PO misuse was associated with various problems, whereas PO use for pain was less problematic. About two thirds of PO misusers (66%–68%) screened positive for both DUD and AUD compared with 16%–27% for nonusers and even lower rates for PO users (8%–20%). Thus, most PO misusers were not just enjoying partying or getting high, they were experiencing a substance use disorder.

TABLE 3.

Covariates of PO use and misuse among veterans

| Percentage with condition by type of PO usera

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonuser | Pain-only | Misuser | |

| DUD | 15.7 | 7.6 | 66.5** |

| AUD | 27.4 | 19.9 | 68.3* |

| TBI | 10.6 | 40.4** | 55.2** |

| PTSD | 15.1 | 32.6 | 19.6 |

| Depression | 15.9 | 37.2* | 8.3 |

| Unemployedb | 51.6 | 48.1 | 78.8** |

| Homeless | 19.8 | 26.7 | 63.0 |

| No partnerc | 86.9 | 80.3 | 96.7* |

Difference from nonusers significant at agr; = .05 level.

Difference from nonusers significant at agr; = .01 level.

All estimates were calculated using RDSAT.

Neither employed nor in school.

Not living with spouse or unmarried partner.

PO users and misusers also had higher rates of TBI. PO users also had higher rates of depression, whereas PO misusers did not. PTSD did not vary significantly with PO use or misuse. PO misuse was associated with major reintegration problems, while use of POs for pain was not. PO misusers (79%) were more likely to be unemployed than nonusers (52%). PO misusers (63%) were much more likely to be homeless than nonusers (20%), although this difference was not statistically significant. Most of the veterans were living without a partner. However, almost all the PO misusers (97%) had no partner compared to 87% of nonusers.

CONCLUSION

Some members of the military develop patterns of PO misuse while deployed in Iraq or Afghanistan and may continue to misuse POs after returning to civilian life. This paper provides insight into the most common patterns observed among veterans returning to low-income predominately minority sections of NYC. The first finding is that PO use was most often initiated during deployment. Few participants had misused POs prior to their last deployment and none had misused POs prior to entering the military. We presented three potential pathways to PO misuse that emphasize the different domains in Zinberg’s framework of drug, set, and setting. It would appear that the setting or sociocultural context is not heavily pronounced in regards to initiation. The findings strongly suggest that initiation of PO misuse typically started with medical use for pain. Use of POs while deployed was not widespread which indicates that POs were not being broadly misused as a group recreational activity. At the same time, relatively few of the participants that received POs for pain management misused these drugs.

This raises the question of which characteristics (or set factors) are most associated with initiating PO misuse among those who received POs for pain. We hypothesized that there might be an opportunistic pathway, such that heavy drinkers would be the ones to become PO misusers. However, this pathway was not common either. Most heavy drinkers who received POs for pain did not become misusers. Moreover, many of the service members who became PO misusers had not been heavy drinkers. Thus, there may be other factors associated with the initiation of PO use and subsequent misuse. Further research is needed with a larger sample of PO misusers to identify these differentiating factors. The current study included only 15 participants that misused POs while deployed and 20 after separation. The project is performing qualitative interviews with a subsample of participants which should provide insight into individuating experiences and the mechanisms underlying the pathway to PO misuse among service members and veterans.

One possibility is that PO misuse among military veterans may be a strategy for coping with emerging mental health and social problems. Of note, most participants who initiated PO misuse while deployed continued to misuse POs after separation. Moreover, those veterans who misused POs after separation exhibited elevated rates of some mental health and reintegration problems, particularly DUD as well as AUD, TBI, unemployment, and homelessness. The direction of causation between mental health problems, social problems, and PO misuse cannot be established with the data presented here for a variety of reasons including the limited number of PO misusers in our sample, a lack of information about mental health and social stressors prior to separation, and the retrospective nature of the present data. However, the complex of correlated mental health and reintegration problems associated with PO misuse is consistent with mutual causation and reinforcement and suggests the presence of severe underlying multidimensional problems among some service members and veterans.

The analysis found that whereas 33% of military personnel from the target population studied received POs for pain management only a fraction (6%) misused them. This is positive and suggests that military doctors are working with patients to monitor and manage pain and drug misuse effectively. On the other hand, it is a serious problem that 6%–7% of veterans returning to low-income minority communities are returning with a drug use problem (or disorder) that they developed while in the military. Our findings suggest that resolving this problem will not be simple. If PO misuse was primarily rooted in a party culture then reducing misuse would likely result from simply reining in partying. Alternatively, if the risk of iatrogenic addiction to POs was extremely high, then use of these drugs and prescribing practices should be monitored closely. However, neither of these scenarios matches the data presented. The findings suggest that PO misuse is interconnected with other mental health and social problems. Even if we could eliminate PO misuse, it might not reduce the other problems. Our findings suggest that PO misuse should be viewed as a fiag for individuals likely experiencing complex difficulties. An extensive case management intervention that simultaneously addresses mental health, reintegration, and substance misuse problems might be most appropriate. Moreover, recent mandates by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to curtail prescriptions for opioid painkillers have been endorsed by the Departments of Defense (DoD) and Veterans Affairs (VA), creating an environment in which some primary care physicians at VA medical centers may be unwilling to continue prescribing POs to recent veterans experiencing chronic noncancer pain. While this will reduce the misuse of POs among some veterans, it also has the potential to lead some veterans to turn to diverted POs or street opiates to maintain their pain management regimen, particularly individuals who had been prescribed strong POs while deployed (Harocopos, Goldsamt, Kobrak, Jost, & Clatts, 2009; Sherman, Smith, Laney, & Strathdee, 2002). Thus, the problems associated with PO misuse are multidimensional and complex. Interventions need to recognize the real pain many veterans endure and the need for effective, long-term pain management programs as well as the potential for misuse.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01 AA020178) and from the Peter F. McManus Charitable Trust. Points of view expressed in this paper do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Government, NIAAA, the McManus Trust or NDRI. The authors express their deep appreciation to the project interviewers—Mr. Gary Huggins (U.S. Marines, retired), Mr. Atiba Marson-Quinones (U.S. Navy Reserves), and Ms. Morgan Cooley (U.S. Army, retired)—to the data manager, Dr. Peter Vazan, and all of the veterans who participated in the study.

Biographies

Andrew Golub, Ph.D., is a Principal Investigator at National Development and Research Institutes, Inc. (NDRI). He received his Ph.D. in Public Policy Analysis from Carnegie Mellon University in 1992. His work seeks to improve social policy and programs through research. His studies have examined trends in drug use, the larger context of use, causes, and consequences of use, and the efficacy of policies and programs as well as associated issues related to violence, crime, policing, poverty, and families. Dr. Golub is currently the Principal Investigator of the Veteran Reintegration, Mental Health and Substance Abuse in the Inner-City Project funded by NIAAA that examines the challenges faced by veterans returning from Afghanistan and Iraq to New York’s low-income predominately-minority neighborhoods. This mixed methods study focuses on the significance of substance misuse and its relationship with other mental health problems, and reintegration into family, work, and community life within the complex of problems prevailing in low-income communities.

Dr. Alex S. Bennett is a Principal Investigator at National Development and Research Institutes (NDRI). He received his Ph.D. in History and Policy from Carnegie Mellon University in 2009. His current work focuses on veterans, overdose prevention and response, and drug use and misuse more broadly. He started work on overdose prevention and outreach services in 2002 with Prevention Point Pittsburgh, an early model for many of the overdose prevention programs that came later. Dr. Bennett continued this work on substance misuse and overdose prevention and response both in an academic and community-based setting doing research, needs assessment, program development, service delivery, and evaluation work. Dr. Bennett currently serves on the Board of Directors of the New York Harm Reduction Educators. In 2012, Dr. Bennett organized a Community Advisory Board (CAB) that includes diverse NYC organizations with a common purpose of addressing veterans substance misuse that includes veterans groups, public health agencies, drug treatment providers, academic researchers, and advocacy groups. This CAB promotes awareness and personal connection between organizations and veterans, facilitates information exchange, and supports collaboration across agencies on local initiatives.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

References

- Abdul-Quadar AS, Heckathorn DD, McKnight C, Bramson H, Nemeth C, et al. Effectiveness of respondent-driven sampling for recruiting drug users in New York city: Findings from a pilot study. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;9:403–408. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9052-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett FJ. The organizational construction of hegemonic masculinity: The case of the US navy. Gender, Work and Organization. 2007;3(3):129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett AS, Golub A. Sociological factors and addiction. In: Shaffer HJ, LaPlante DA, Nelson SE, editors. Addiction syndrome handbook. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2012. pp. 195–210. [Google Scholar]

- Bergen-Cico DK. War and drugs: The role of military confiict in the development of substance abuse. Boulder, CO: Paradigm; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL) Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34(8):669–673. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert AS, Roeder K, Ilgen MA. Unintentional overdose and suicide among substance users: A review of overlap and risk factors. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;110(3):183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray RM, Hourani LL. Substance use trends among active duty military personnel: Findings from the United States Department of Defense Health Related Behavior Surveys, 1980–2005. Addiction. 2007;102(7):1092–1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray RM, Hourani LL, Rae Olmsted KL, Witt M, Brown JM, Pemberton MR, et al. 2005 Department of Defense Survey of Health Related Behaviors Among Active Duty Military Personnel. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bray RM, Olmsted KR, Williams J. Misuse of prescription pain medications in US active duty service members. In: Wiederhold BK, editor. Pain Syndromes–From Recruitment to Returning. Amsterdam: IOS Press; 2012. pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bray RM, Pemberton MR, Lane ME, Hourani LL, Mattiko MJ, Babeu LA. Substance use and mental health trends among U.S. military active duty personnel: Key findings from the 2008 DoD Health Behavior Survey. Military Medicine. 2010;175(6):390–399. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-09-00132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDCP. Prescription painkiller overdoses in the US: Vital signs. 2011 Retrieved August 28, 2012, from http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/painkilleroverdoses/

- Courtwright DT. Dark paradise: A history of opiate addiction in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2001. Enl. [Google Scholar]

- Ender MG. American soldiers in Iraq: McSoldiers or innovative professionals? New York: Routledge; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Finley EP. Fields of combat: Understanding PTSD among veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. Ithaca, NY: Cornell; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Goebel JR, Compton P, Zubkoff L, Lanto A, Asch SM, Sherbourne CD, et al. Prescription sharing, alcohol use, and street drug use to manage pain among veterans. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2011;41(5):848–858. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub A, Johnson BD, Dunlap E, Sifaneck S. Projecting and monitoring the life course of the marijuana/blunts generation. Journal of Drug Issues. 2004;34(2):361–388. doi: 10.1177/002204260403400206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham DP, Cardon AL. An update on substance use and treatment following traumatic brain injury. Annals of the New York Academy of Science. 2008;1141:148–162. doi: 10.1196/annals.1441.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harocopos A, Goldsamt LA, Kobrak P, Jost JJ, Clatts MC. New injectors and the social context of injection initiation. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2009;20(4):317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Social Problems. 1997;44(2):174–199. [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling II: Deriving valid population estimates from chain-referral samples of hidden populations. Social Problems. 2002;49(1):11–34. [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD. Extensions of respondent-driven sampling: Analyzing continuous variables and controlling for differential recruitment. Sociological Methodology. 2007;37(1):151–207. [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD. Respondent driven sampling. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9531.2011.01244.x. Retrieved August 24,2012, from www.respondentdrivensampling.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Heltemes KJ, Dougherty AL, MacGregor AJ, Galarneau MR. Alcohol abuse disorders among U.S. service members with mild traumatic brain injury. Military Medicine. 2011;176(2):147–150. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-10-00191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holyfield L. Veterans’ journeys home: Life after Afghanistan and Iraq. Boulder, CO: Paradigm; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Iguchi M, Ober A, Berry S, Fain T, Heckathorn D, Gorbach P, et al. Simultaneous recruitment of drug users and men who have sex with men in the United States and Russia using respondent-driven sampling: Sampling methods and implications. Journal of Urban Health. 2009;86:5–31. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9365-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Substance use disorders in the US armed forces. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Narcotics Control Board. Report of the International Narcotics Control Board for 2008. New York: United Nations; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffri J. Changing the beat a study of the worklife of jazz musicians (Vol. III: Respondent-Driven Sampling. Washington, DC: National Endowment for the Arts; 2003. Social networks of jazz musicians; pp. 48–61. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CV, Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, Tetu AM, Cranston K, Bertrand T, et al. Health care access and sexually transmitted infection screening frequency among at-risk Massachusetts men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health. 2009:S187–S192. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.127464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Ramchand R, Osilla KC, Caldarone LB, Burns RM. Invisible wounds: Predicting the immediate and long-term consequences of mental health problems in veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The phq-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansky A, Abdul-Quader AS, Cribbin M, Hall T, Finlayson TJ, Garfein RS, et al. Developing an HIV behavioral surveillance system for injecting drug users: The National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System. Public Health Reports. 2007;122:48–55. doi: 10.1177/00333549071220S108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larance B, Degenhardt L, Lintzeris N, Winstock A, Mattick R. Definitions related to the use of pharmaceutical opioids: Extramedical use, diversion, non-adherence and aberrant medication-related behaviours. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2011;30(3):236–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madaus JW, Miller WK, II, Vance ML. Veterans with disabilities in postsecondary education. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability. 2009;22(1):10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Manchikanti L. National drug control policy and prescription drug abuse: Facts and fallacies. Pain Physician. 2007;10(3):399–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manchikanti L, Helm S, Fellows B, Janata J, Pampati V, Grider J, et al. Opioid epidemic in the United States. Pain Physician. 2012;15(3):ES9–ES38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manchikanti L, Singh A. Therapeutic opioids: A ten-year perspective on the complexities and complications of the escalating use, abuse, and nonmedical use of opioids. Pain Physician. 2008;11(2 Suppl):S63–S88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ONDCP. Epidemic: Responding to America’s prescription drug abuse crisis. 2011 Retrieved August 28, 2012, from http://www.whitehouse.gov/ondcp/

- Poehlman JA, Schwerin MJ, Pemberton MR, Isenberg K, Lane ME, Aspinwall K. Socio-cultural factors that foster use and abuse of alcohol among a sample of enlisted personnel at four navy and marine corps installations. Military Medicine. 2011;176(4):397–401. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-10-00240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusch ML, Lozada R, Pollini RA, Vera A, Patterson TL, Case P, et al. Polydrug use among IDUs in Tijuana, Mexico: Correlates of methamphetamine use and route of administration by gender. Journal of Urban Health. 2009;86(5):760–775. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9377-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health Public Use Codebook. 2010 Retrieved March 16, 2012, from http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/SAMHDA/

- Shahmanesh M, Wayal S, Cowan F, Mabey D, Copas A, Patel V. Suicidal behavior among female sex workers in Goa, India: The silent epidemic. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(7):1239–1246. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.149930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SG, Smith L, Laney G, Strathdee SA. Social influences on the transition to injection drug use among young heroin sniffers: A qualitative analysis. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2002;13(2):113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Skidmore WC, Roy M. Practical considerations for addressing substance use disorders in veterans and service members. Social Work in Health Care. 2011;50(1):85–107. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2010.522913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Army. Army health promotion, risk reduction and suicide prevention report. Washington, DC: U.S. Army; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Army. Army 2020: Generating health & discipline in the force ahead of the strategic reset. Washington, DC: U.S. Army; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Defense. Enhanced postdeployment health assessment process (dd form 2796) 2008 Retrieved October 9, 2012, from http://www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/infomgt/forms/eforms/dd2796.pdf.

- Wang J, Falck RS, Li L, Rahman A, Carlson RG. Respondent-driven sampling in the recruitment of illicit stimulant drug users in a rural setting: Findings and technical issues. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;(32):924–937. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner M, Chen LH, Makuc DM, Anderson RN, Miniño AM. Drug poisoning deaths in the United States, 1980–2008. NCHS Data Brief. 2011 Retrieved February 27 2013, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db81.htm. [PubMed]

- Wattana W, van Griensven F, Rhucharoenpornpanich O, Manopaiboon C, Thienkrua W, Bannatham R, et al. Respondent-driven sampling to assess characteristics and estimate the number of injection drug users in Bangkok Thailand. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;90:228–233. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wejnert C, Heckathorn DD. Web-based network sampling: Efficiency and efficacy of respondent-driven sampling for online research. Sociological Methods and Research. 2008;37(1):105–134. [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Lang C, Hasson N, Linder S, Clark D. Opioid use in young veterans. Journal of Opioid Management. 2010;6(2):133–139. doi: 10.5055/jom.2010.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinberg NE. Drug, set, and setting: The basis for controlled intoxicant use. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]