Abstract

The active metabolite of vitamin A, retinoic acid (RA), is a powerful regulator of gene transcription. RA is also a therapeutic drug. The oxidative metabolism of RA by certain members of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) superfamily helps to maintain tissue RA concentrations within appropriate bounds. The CYP26 family—CYP26A1, CYP26B1, and CYP26C1—is distinguished by being both regulated by and active toward all-trans-RA (at-RA) while being expressed in different tissue-specific patterns. The CYP26A1 gene is regulated by multiple RA response elements. CYP26A1 is essential for embryonic development, whereas CYP26B1 is essential for postnatal survival as well as germ cell development. Enzyme kinetic studies have demonstrated that several CYP proteins are capable of metabolizing at-RA; however, it is likely that CYP26A1 plays a major role in RA clearance. Thus, pharmacological approaches to limiting the activity of CYP26 enzymes may extend the half-life of RA and could be useful clinically in the future.

Keywords: embryonic development, enzyme kinetics, germ cell development, P450 oxidative metabolism, retinoid-drug interactions, vitamin A

INTRODUCTION

Vitamin A, through metabolism to all-trans-retinoic acid (at-RA), plays a crucial role in cellular proliferation and differentiation. The physiological actions of RA begin early in development and continue throughout life. RA also is a clinically useful drug (16, 23, 106). At-RA functions as an endogenous ligand for nuclear retinoic acid receptors (RARα, β, and γ), which dimerize with retinoid X receptors (RXRα, β, and γ) and bind to specific DNA sites, known as retinoic acid response elements (RAREs), usually located in the promoter regions of the genes that are direct transcriptional targets of RA (6, 7, 22, 115). Although altogether more than 500 genes are regulated by RA under various physiological conditions, the mode of regulation has been discovered for relatively few of them (5).

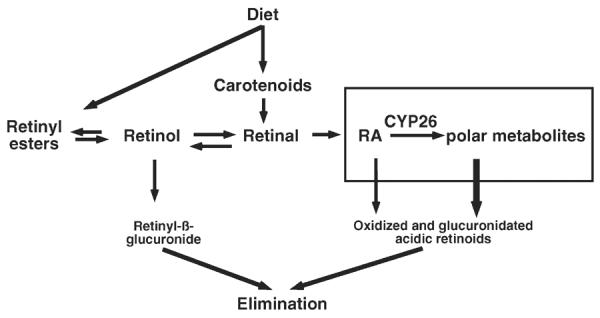

The need for close regulation of RA concentrations at the cellular and tissue levels is well demonstrated by the observations that both a deficiency and an excess of RA, during critical developmental periods, are teratogenic to the embryo (15, 95). Tissue levels of RA are regulated both by synthesis from retinol and by catabolism (15, 62) (Figure 1). In recent years, studies have provided new insight into the processes by which RA is catabolized and the means through which catabolism is markedly increased in response to nutritional or pharmacological situations in which the concentration of RA rises. This review focuses on mechanisms that regulate RA through the process of oxidative metabolism, and particularly on the gene family cytochrome P450 (CYP)26, for which at-RA is often a strong inducer at the level of gene transcription as well as the substrate for the gene product at the level of enzyme activity.

Figure 1.

Metabolism of vitamin A, showing production and metabolism of retinoic acid (RA) (boxed). CYP, cytochrome P450.

Initial Studies on Retinoic Acid Oxidation

In the 1960s, original studies by Roberts and DeLuca (18, 83) reported on the metabolism of 14C-radiolabeled RA, prepared with the label in various positions, including at carbon positions 6 and 7, 14, and 15, which were administered to intact vitamin A–deficient rats. On the basis of the presence of labeled metabolites in the feces and urine, they speculated that RA might be metabolized through at least three pathways. One of these pathways, which accounted for nearly two-thirds of RA metabolism, involved the excretion of the retinoid with an intact isoprenoid side chain, which they assumed to include retinoyl-β-glucuronic acid (18), which had been characterized earlier as a metabolite in the bile of RA-treated rats (20, 48). The remaining two pathways apparently involved oxidative loss of the C-14 and C-15 positions. Further studies, after the advance of techniques in retinoid analysis, reported the identification of metabolites formed in vivo, in cells, or in cell-free membrane systems (17, 24, 25, 30, 31, 57, 58, 63, 84–86). From these early studies, the principal oxidative reaction in RA metabolism was postulated to be catalyzed by an enzyme or enzymes with properties similar to cytochrome P450–mediated monooxgenase systems, based on the localization of activity to the microsomal fraction, the requirement for oxygen and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) for catalysis, and the inhibition of RA metabolism by carbon monoxide (84, 85). Second, the enzymatic reaction system deduced from these studies is also apparently sensitive to the vitamin A status of the animal, because pretreatment in vivo with vitamin A or RA boosted the system for the metabolism of at-RA to polar metabolites, including 4-hydroxyand 4-oxo-RA (46). Later, various CYP450 isozymes purified from human (47), rat (96), and rabbit (87) liver were shown to have significant RA hydroxylation activity in the presence of NADPH, whereas imidazole-based reagents such as ketoconazole were able to reduce the oxidative metabolism of RA in vitro and increase the half-life of RA in vivo (111, 112). Other studies suggested that several cytochrome P450 members including CYP2C8 (47) and CYP3A (55) exhibit RA hydroxylase activity. However, it was not until 1996 that the first member of the cytochrome P450 family, known as CYP26, was cloned and shown to be not only specific toward the enzymatic oxidation of at-RA but also highly induced by its own substrate (117). The CYP26 family is now recognized as a major contributor to the oxidative metabolism of RA under nutritional and pharmacologic conditions. A schematic of the phase 1 (oxidation) and phase 2 (conjugation) metabolism of RA, as mediated sequentially by CYP26 and uridine 5′-diphospho (UDP)-glucuronosyl transferase enzymes, is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schema of the metabolism of retinoic acid (RA) to 4-hydroxy and 4-oxo metabolites (phase 1 metabolism) followed by glucuronidation to form water-soluble metabolites (phase 2 metabolism). Carbon positions where RA metabolism occurs are numbered; * indicates positions that were labeled in metabolic studies in rats in vivo (18, 83). CYP, cytochrome P450; UDP, uridine 5'-diphospho.

CHARACTERIZATION OF CYP26 FAMILY MEMBERS

Cloning of the Individual Members of the CYP26 Family

Based on knowledge from the studies above, White et al. (117) used a differential display approach to identify genes that are responsive to RA, using zebrafish as a model organism. They tested for genes expressed during regeneration of the amputated caudal fin of zebrafish, in the absence or presence of at-RA. By this approach an RA-responsive cDNA fragment was isolated, which was then used to clone P450RAI (for RA inducible) from a cDNA library from zebrafish embryo. Similar to all cytochrome P450 superfamily members, the predicted protein from this clone contains a conserved heme-binding domain motif located in the C-terminal part of the protein. This domain consists of a cysteine residue at the center, involved in the heme binding, surrounded by a series of conserved amino acid residues. However, the predicted cytochrome P450 protein was found to have less than 40% amino acid identity to other known cytochrome P450s, and therefore the gene was classified as a member of a new cytochrome P450 gene family, designated CYP26 (80, 116), with P450RAI becoming CYP26A1 (66). After transfection of CYP26A1 cDNA into COS-1 cells, the expressed CYP26A1 protein catalyzed the conversion of at-RA to 4-hydroxy-RA, 4-oxo-RA, and 18-hydroxy-RA (117). A year later, the same authors reported the human cDNA ortholog of CYP26A1 (116), and at the same time two independent groups cloned the mouse cDNA version of CYP26A1 (26, 80). CYP26A1 cDNA has now been reported for several other species including chicken, xenopus, rat, and cow (32, 40, 99, 114).

The gene for CYP26B1 was identified on the basis of an in silico search using the sequence alignment available for CYP26A1 and available ESTs in the Genbank database, from both human and zebrafish (66). This gene was also cloned, as P450RAI2 (CYP26B1), by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from a human retina cDNA library (118). The third member of the CYP26 family, CYP26C1, was discovered through searching the high-throughput genomic sequences database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information using the amino acid sequences of human CYP26A1 and CYP26B1. The information on the sequence of an available bacterial artificial chromosome clone containing the CYP26C1 gene was used for PCR-based cloning from human adrenal gland (101). This strategy yielded the nucleotide region corresponding to the open reading frame (ORF) of the third novel member of the CYP26 family, CYP26C1. A zebrafish gene that was reported as CYP26D1 is 99% similar to CYP26C1 and thus should be classified as CYP26C2 according to the nomenclature for the cytochrome P450 superfamily (65). On the basis of available sequence information in the Genbank database for human, mouse, and rat CYP26 family genes, it appears likely that the CYP26A1, CYP26B1, and CYP26C genes complete the CYP26 gene family, although additional protein variants may exist through either alternative RNA splicing or alternative usage of promoters.

The three human CYP26 proteins are predicted to range from 497 to 522 amino acids in length, which may correspond to about a molecular mass of 50 to 60 kDa with possible glycosylation, which is typically observed in other cytochrome P450s. Each protein is predicted to contain several membrane-spanning regions (101). Upon alignment of all three human CYP26 proteins, less than 55% of the amino acids are identical: CYP26A1 and CYP26B1 share only 43% amino acid identity, CYP26A1 and CYP26C1 45%, and CYP26B1 and CYP26C1 51%. Similar patterns of identity have been observed in other species. However, for each of the three genes, the CYP26 proteins from human, rat, mouse, and zebrafish are closely related, suggesting there has been strong pressure for amino acid sequence preservation throughout vertebrate evolution (33). Of the three proteins, CYP26B1 is the most highly conserved and CYP26C1 the least conserved. The greater conservation observed for CYP26B1 might be related to its essential role in germ cell development, as discussed further below in this review.

Expression Patterns

In general, cytochromes P450 comprise a superfamily of membrane-bound oxidative hemoprotein enzymes, which are expressed in many tissues in vivo but most often are present at the highest level in mammalian liver. These enzymes have been found to be the principal route of metabolism for many hormones, drugs, and other xenobiotics. The patterns of expression for each of the three CYP26 genes differ both in the adult and in embryonic tissues (the latter are discussed in the section titled Role of Vitamin A in Embryonic Development) and have much broader expression patterns than many cytochrome P450s. In the adult, CYP26A1 is mostly highly expressed in the liver, but less in brain and testis (80, 114, 120) (see examples in Figure 3). In the adult human liver, comparative studies found the level of CYP26A1 expression to be highly variable among individuals (105). This might be attributable to the variability among individuals in vitamin A intake, since CYP26A1 is highly regulated by vitamin A in the liver, and/or genetic background, as discussed further below. CYP26A1 is also expressed in cell lines from several tissue origins. For CYP26A1, cell lines tend to fall into two groups. One group expresses the gene at a very low level but exhibits a high response to vitamin A or RA; these include HepG2 and MCF-7 cells (49, 50, 116, 124). The other group expresses the CYP26A1 gene at a higher basal level but is less regulated by vitamin A or RA; this includes HEK293T and SK-LC6 (116, 124). Human epidermal keratinocytes, on the other hand, express only low basal levels of CYP26A1 and do not exhibit induction by RA (78).

Figure 3.

Relative abundance of CYP26A1 mRNA in rat tissues and CYP26A1 promoter regulation in HepG2 hepatocytes. (A) CYP26A1 mRNA is much more abundant in the liver compared with lung, small intestine, and testis of rats and is down-regulated in vitamin A deficiency. Northern blot analysis from (114). (B) Diagram of the CYP26A1 promoter showing three RAREs and a half site (RARE4), R1, R2, R3, and R4. Distances from the transcription start site are marked. Promoter activity (relative luciferase activity) in HepG2 cells for the full-length (FL) wild-type promoter sequence and response elements (R), and for sequences mutated (M), at M1, M2, M3, or M4. Whereas RA increased activity ~20 fold for the FL promoter, mutation of any one of the RARE sites reduced luciferase activity by 80% to 90%, indicating that all of these RAREs are necessary for the RA-induced expression of CYP26A1. Data from (124). Abbreviations: CYP, cytochrome P450; RARE, retinoic acid response element; VAD, vitamin A deficient; VAS, vitamin A sufficient.

By comparison, CYP26B1 is expressed mainly in brain tissue, but also at low levels in other tissues (118, 120). For human adult cerebellum, CYP26B1 mRNA levels were approximately twofold higher than in adult whole-brain tissue (102, 107). CYP26B1 is also expressed in adult liver tissue as well as immune cells (102, 107). In lung, CYP26B1 appears to be the predominant CYP26 gene (119). CYP26B1 is expressed in T-cells in the gut, apparently to control RA signaling by regulating the concentrations of RA originated from the synthesis in the dendritic cells of the gut-related organs (102). Among cell lines, HepG2 cells, MCF-7 cells, and aortic smooth muscle cells all express CYP26B1 at higher levels when treated with RA (71, 104, 118).

In contrast, the CYP26C1 gene is expressed mainly during embryonic development (81, 82, 90, 100), although it is detectable at low levels in several adult tissues including adrenal gland, lung, spleen, testis, and brain (120). CYP26C1 is expressed in keratinocyte cell lines treated with either 9-cis-RA or at-RA (101). However, 9-cis-RA was much more effective than at-RA in inducing expression of the gene (101). It is not known whether such difference in induction might be related to the preference of this isozyme for 9-cis-RA as the substrate.

Finally, numerous genomic polymorphisms have been reported for each of the three members of the CYP26 family (for more information, see http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/). For CYPA1 member, two mutant alleles that result in coding changes (F186L and C358R) were found to have 40% to 80% lower activity toward RA metabolism as compared with the wild-type proteins (45). Since CYP26A1 as well as CYP26B1 have been shown to be nonredundant and indispensable during development, as discussed further below in this review, significant contributions of all of these genomic polymorphisms could be important in determining RA metabolism and signaling.

PHYSIOLOGICAL AND MOLECULAR REGULATION OF CYP26 GENE EXPRESSION

That at-RA is not only the specific substrate for CYP26A1 and CYP26B1 isozymes but also a potent inducer of these genes is particularly evident for CYP26A1 in liver (26, 80, 89, 105, 114, 121, 125) (see also Figure 3) and for CYP26B1 in lung tissue (12, 119). In liver, CYP26A1 mRNA is present at a low but detectable level in the vitamin A–adequate state, whereas in the vitamin A–deficient state, CYP26A1 mRNA falls to a nearly undetectable level (114). In a nutritional study in which rats were fed graded doses of vitamin A (marginal, adequate, and supplemented), both liver total retinol concentration, an indicator of vitamin A status, and CYP26A1 mRNA levels exhibited dose-dependent responses to dietary vitamin A (14). A similar graded response to dietary vitamin A was observed in the liver of rats fed vitamin A–adequate and vitamin A–supplemented diets across their entire life span, from young to old age (121). CYP26A1 mRNA increased progressively with age for each level of dietary vitamin A, which also correlated with age-related increases in liver vitamin A content in rats fed either a vitamin A–adequate or vitamin A–supplemented diet. Thus, under steady state conditions, differences in the intake of vitamin A and the duration of exposure to vitamin A correlate well with CYP26A1 mRNA levels. However, although the CYP26A1 gene is responsive to differences in dietary intake of vitamin A, the most dramatic response is observed after administration of at-RA and, again, especially in the liver. CYP26A1 mRNA levels increased some 2,000-fold 6 hours after vitamin A–deficient rats were treated with ~100 μg of at-RA and then declined to near basal levels by 72 hours (89, 114). These results suggest that a continuous presence of RA is necessary to maintain elevated expression of CYP26A1. The rapid decrease in the level of CYP26A1 mRNA after reaching its peak, in the absence of additional RA, also suggests that the half-life of the message is relatively short. In metabolic studies, the conversion of 3H-RA to 3H-labeled polar metabolites in the liver and level of CYP26 mRNA increased concomitantly in the same animals (14, 89). The CYP26A1 gene also exhibits moderate regulation by retinoid treatment in other tissues including testis, lung, kidney, and small intestine (12, 114, 124) (Figure 3A). Similar to the response of CYP26A1 in the liver of intact animals, CYP26A1 mRNA also increases rapidly in hepatocyte cell lines, such as HepG2 cells, after treatment with at-RA or its analogs (104, 116, 124). Like in liver, the concentration of vitamin A is nil in the extrahepatic tissues of vitamin A–deficient rats, including testis, lung, kidney, and small intestine; however, upon treatment with RA the CYP26A1 mRNA level increased significantly, but not more than 10-fold after 10 hours (114).

Comparatively, CYP26B1 mRNA also increased nearly linearly with RA dose in the liver, but by not more than 10- to 15-fold within ten hours after treatment and then, similar to CYP26A1, it decreased to basal levels by 72 hours (125; R. Zolfaghari & A.C. Ross, unpublished data). In the lung, CYP26B1 may be the predominantly responsive form of CYP26 mRNA (119). In the lungs of neonatal rats treated with vitamin A, RA, or a combination of both, CYP26B1 mRNA increased rapidly and, relative to CYP26A1, to a higher level, and the increase was also more persistent (119). In T cells from gut-related lymphoid organs, CYP26B1 has been shown to be upor down-regulated by at-RA and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), respectively (102). Additionally, CYP26B1 is expressed in the postnatal mouse ovary, where it is down-regulated by activin, a member of the TGF-β family. In this tissue, CYP26B1 is proposed to function in the control of granulosa cell proliferation (38).

Regarding CYP26C1, which appears to be a minor CYP26 in adult tissues, little is known about its physiological expression of CYP26C1 under dietary or pharmacological conditions. However, whereas both CYP26A1 and CYP26B1 genes are induced by vitamin A and RA, the CYP26C1 gene is either up-regulated or down-regulated by RA dependent on tissues or cell types (81, 101). At present, CYP26C1 stands apart as an atypical member of this gene family due to its relatively low expression in adult tissues, wider substrate utilization, and preference for 9-cis-RA, and down-regulation as well as up-regulation of its mRNA in response to retinoid treatment.

For all three CYP26 genes, even where their tissue distribution has been defined, there is limited information on their cell-type-specific expression. By in situ hybridization analysis, CYP26A1 is located in liver hepatocytes (89). CYP26B1 has been localized to brain regions but not cell types. For CYP26C1, no cell-level information is available for adult tissues. Additional studies are needed to clarify in greater detail the cellular distribution of these genes and, for CYP26B1 and CYP26C1, how they are regulated.

Transcriptional Regulation of CYP26A1 in Cell Lines and Liver

Research to understand the mechanism of regulation of CYP26 genes has focused to date on CYP26A1 because of its rapid and high level of response in vivo and in cells. Originally, CYP26A1 transcriptional activation by RA was shown to be controlled by a conserved RARE element present in a reversed direction located in the proximal region of CYP26A1 putative promoter close to the transcription start site of the gene (49). This element region in cooperation with the nearby guanine-guanine-rich region representing SP1/SP3 binding sites was found to increase the promoter activity in response to RA in a few cell lines, including F9 and P19 cells of embryonic origin. Since the magnitude of the response of the promoter to RA was still far less than the endogenous response of the gene, it was speculated that there should be another additional element(s) acting in control of the promoter in response to RA. Later, another conserved RARE element, RARE2 (Figure 3B), located in the distal region of the CYP26A1 gene, was found to be active in cooperation with the proximal RARE1 region in response to at-RA in P19 cells as well as in MCF-7 breast carcinoma cells (50).

As mentioned above, the induction of CYP26A1 is particularly strong in the liver. Physiologically, hepatocytes are likely to be the first cells to sense the concentration of RA entering the liver via the portal vein from the intestines, via the splanchic circulation, and via the hepatic vein from the systemic circulation, and CYP26A1 in concert with UDP-glucuronidyl transferases (92), as liver-expressed phase II enzymes, are ideally situated to convert excess RA into polar metabolites and then to further convert them to water-soluble compounds for elimination from the body as biliary metabolites (Figures 1 and 2). Among liver-expressed genes, none have exhibited a larger response to dietary vitamin A and exogenous RA than CYP26A1 (89). As analyzed by nuclear run-on assay in the liver of intact rat, almost the entire induction of CYP26A1 mRNA by retinoids is due to the activation of the transcriptional process (125).

Sequence analysis indicates that at least four RAREs are present within about 2.2 kbp region upstream of the transcription start site of the CYP26A1 gene; one (RARE1, as discussed above) is present in the proximal region and the other three (RARE2, RARE3, and a half-site, RARE4) in a cluster in the distal region about 2.0 kbp away from the proximal element (Figure 3B). These elements together with the distances between them are highly conserved, at least between human and rodent CYP26A1 promoter regions. The promoter is highly responsive to RA in HepG2 cells (124). Like CYP26A1 mRNA, the promoter of the CYP26A1 gene is perhaps the most responsive promoter to RA, as compared to any other gene promoters reported in the literature. In fact, the response of the CYP26A1 promoter has been proposed as a tool for analyzing RA concentrations in biological systems (50). Each of the four individual elements in both the distal and proximal regions is essential for full activity of the promoter in response to RA in HepG2 cells because deletion or mutation of any one of these elements significantly blunted or abrogated the promoter response to at-RA (124) (Figure 3B). In comparison, HEK293 cells, used as a model for nonhepatic cells in which CYP26A1 expression is less responsive to RA than in liver cells and as also observed for kidney and other peripheral tissues in vivo (114, 124), did not exhibit the same dependency on all four RAREs for maximal expression (124). Although the group of distal response elements is relatively far away from RARE1 and the transcription start site, it is possible that the distal region is brought into proximity to the proximal region by chromatin looping, resulting in the increased transcriptional response of the gene to elevations in vitamin A in vivo and RA concentration in vivo and in cultured cells. By chromatin immunoprecipitation assay using chromatin from RA-treated and untreated HepG2 cells, DNA-dependent RNA polymerase II (Pol-II) occupied not only the region around RARE1 but also the more distal region after RA treatment (124), suggesting that the binding of RA to RARs on these elements may facilitate interaction between these regions and with the basal transcriptional machinery. In the future, additional studies to map changes in chromatin conformation may help to further clarify how CYP26A1 is regulated by its multiple and essential RAREs.

Unlike for CYP26A1, the mechanism of regulation of gene expression for CYP26B1 is not understood. The proximal regulatory region of the CYP26B1 gene lacks the retinoid response elements found in CYP26A1. From an analysis of hundreds of retinoid responsive genes, Balmer & Blomhoff (5) concluded that for only a few dozen has a direct mechanism been defined, although indirect regulation may be more common.

As mentioned above, the CYP26C1 gene is either induced or suppressed by RA depending upon tissue and cell types. Like CYP26B1, the upstream region of the CYP26C1 gene, as a possible regulatory region, lacks any RARE. However, as the CYP26C1 gene is located just upstream of the CYP26A1 gene, it is not known whether the regulatory region of CYP26A1 gene could have any influence on the expression of the CYP26C1 gene.

CATALYTIC ACTIVITY OF THE CYP26 FAMILY

Like other cytochrome P450 family members, CYP26 proteins are endoplasmic reticulum (microsomal) proteins. They are difficult to isolate and apparently require a membrane environment for activity. Thus, studies of enzymatic activity of the CYP26 proteins have relied on assays in microsomal fractions prepared from cultured cells and tissue samples (105, 117, 118, 121), especially from liver, or supersome assemblies as a source of cDNA-expressed enzymes (51). In general, similar oxidized products have been reported for microsomal extracts from liver of mice and rats treated in vivo with at-RA (89, 121) as compared to those observed in transfected cells (101, 117, 118).

The substrate specificity of both CYP26A1 and CYP26B1 appears to be similar based on studies in transfected COS-1 cells. Each of them exhibits very high catalytic activity toward at-RA but a much lower activity toward other retinoids, including 9-cis-RA, retinal, and retinol (101, 117, 118). Although the activity of CYP26C1 was similar to that of CYP26A1 and CYP26B1 for oxidation of at-RA, CYP26C1 catalyzed equally the oxidation of 9-cis-RA (101). Thus, whereas all three members of the CYP26 family are able to convert at-RA to 4-hydroxy- and 4-oxo-at-RA and 18-hydroxy-at-RA as the primary products (51, 101, 117, 118), the major oxidative metabolites of 9-cis-RA by CYP26C1 are the corresponding 4-hydroxy-9-cis-RA and 4-oxo-9-cis RA (101). Recombinant CYP26A1 protein catalyzed the oxidative conversion of at-RA efficiently in a reaction supplemented with P450 oxidoreductase and NADPH but was independent of cytochrome b5 (51). The catalytic activity of all three CYP26 enzymes is blocked by compounds, such as ketoconazole (101, 117, 118), which function as general inhibitors of cytochrome P450 enzymes; however, CYP26C1 activity is inhibited only at a much higher concentration of ketoconazole as compared to CYP26A1 and CYP26B1 (101), another distinction between CYP26C1 and the other two CYP26s.

The functional activity of the products of RA metabolism has been a subject of some debate. Results from several studies showed that some of the oxidative products of at-RA metabolism such as 4-oxo-RA and 5,6 epoxy-RA may have some biological activity. These activities include the induction of differentiation and subsequent proliferation of growth-arrested A spermatogonia in vitamin A–deficient mice testis (27), modulation of positional specification in early embryo in Xenopus (77), good growth response in vitamin A–deficient rats as compared to retinyl acetate (36), and epithelial differentiation (58). However, based on genetic evidence, at-RA—but not the oxidative derivatives of at-RA metabolism—is involved in embryonic development (67). Thus, the data currently are inconsistent, and no firm conclusion can be drawn regarding the biological activity of oxidized retinoids. Whether these metabolites are active or inactive could be context specific, according to where they are produced and available.

CYP26 AND EMBRYOGENESIS

Role of Vitamin A in Embryonic Development

Vitamin A is essential for reproduction in both the male and female. During embryonic development, RA plays a pivotal role in pattern formation both in the early embryo and during the period of organogenesis. Vitamin A deficiency at the time of mating and during pregnancy results in a collection of defects and malformations in the fetus, referred to as vitamin A–deficiency syndrome (15, 60, 93). On the other hand, an excess intake of vitamin A, RA, or acidic retinoid analogs is highly teratogenic and induces abnormalities that are not very different from those that result from deficiency, including defects in craniofacial, central nervous, and cardiovascular systems (15, 60, 95). Nearly all of the cells of the embryo are capable of RA signaling, as isoforms of each of the retinoid nuclear receptors are expressed during embryonic development (10). Because RA molecules can easily diffuse across distances or be transported by proteins such as albumin and are rapidly taken up by cells, it is presumed that the proper regulation of local concentrations of RA is essential for normal development (76). Tissue RA concentrations are regulated both by enzymes that generate RA—retinol and retinal dehydrogenases—and by enzymes that metabolize RA to less active metabolites, including all members of the CYP26 family (19, 68). All members of the CYP26 family are expressed in human, rodent, and chicken embryos, but their special and temporal regulation is highly specific (76).

Role of Retinoic Acid in Germ Cell Development

During germ cell development, whether germ cells develop as oocytes or spermatogonia depends on the time at which the cells enter meiosis. Although germ cells in the embryonic ovary progress to meiosis, those in the embryonic testis are retarded, and meiosis does not occur until puberty (9). In an expression screen to detect genes expressed sex-specifically during mouse gonadogenesis, CYP26B1 was identified as a gene that becomes essentially male specific by 12.5 days postcoitum (dpc) (8). Whereas RA, which is known to stimulate meiosis (39), is produced in the mesonephros adjacent to the developing gonads of both sexes, as demonstrated by expression of an RA-sensitive reporter gene, by 13.5 dpc only the male gonad expresses CYP26B1, apparently in Sertoli cells, and the relative amount of RA in the male gonad is reduced to 25% of that in the female gonad. Moreover, in male gonadal organ cultures the addition of ketoconazole to reduce RA oxidation resulted in elevated expression of Scp3 and Dmc1, genes that normally are higher in the female. Similarly in other studies, CYP26B1 together with an unknown secreted “meiosis inhibitory factor” inhibited meiosis specifically in male germ cells (29). However, conversely, in CYP26B1-null mouse embryos, the levels of Stra8 and Scp3, considered markers of female germ cells, were up-regulated in XY gonads, and meiosis progressed earlier than normal (8, 9). It also may be that CYP26B1 expression at an earlier stage of female germ cell development serves as an inhibitory signal to prevent premature induction of meiosis by RA, with the inhibition then being released when CYP26B1 gene expression is extinguished from 11.5–13.5 dpc (8). Bowles et al. (8, 9) concluded that CYP26B1 in Sertoli cells, acting as a meiosis-inhibiting factor in males, holds the key to the appropriate timing of male germ cell maturation by retarding meiosis in the male fetal testis. Recently, studies have indicated that sex-specific timing of meiotic initiation is regulated by the expression of CYP26B1, similar to findings of the work cited above, but that RA is not required for the induction of Stra8 in the female, since increased Stra8 expression was observed in the ovaries of mice lacking genes involved in RA production (41). Further studies are needed to elucidate how CYP26B1 expression is turned on in a sex-specific manner in the fetal Sertoli cells and extinguished in female germ cells and whether RA is required for meiotic progression in the female embryo.

Expression of CYP26 During Embryonic Development and Stem Cell Differentiation

During murine embryonic development, all three CYP26 family isozymes are distinctly expressed in relatively nonoverlapping regions, which are particularly sensitive to the teratogenic effects of RA (19, 68). CYP26A1 is present at an earlier stage of embryonic development as compared to CYP26B1 and CYP26C1. Whereas CYP26A1 is expressed as early as embryonic day (E)6.0 in extraembryonic and embryonic endoderm (26), just before gastrulation stage and presumably to protect the embryo from excess maternal vitamin A or RA, the expression of CYP26B1 is initiated at E8.0 in the hindbrain (52), in distinctive rhombomeric regions that differ from those that express either CYP26A1 or CYP26C1 at the same stage of development. During human prenatal development, CYP26B1 mRNA expression is much higher in cephalic tissues than hepatic tissues (107), and in the early gestation period, CYP26B1 expression in cephalic tissue is about ten times higher than at later gestational stages (107). CYP26C1 starts to be expressed as early as E7.5 in the amnion (100). As development progresses, whereas the CYP26 family members each continue to be expressed in distinctive rhombomeres of the hindbrain, CYP26A1 is strongly expressed in the tail bud, and CYP26B1 is detectable in the limb buds (26, 52). At later stages during the development of the eye, CYP26A1 alone is expressed in the developing neural retina, whereas both CYP26A1 and CYP26B1 are coexpressed in the retinal pigment epithelium (2). In developing visceral organs, CYP26A1 is expressed only in the diaphragm and outer stomach mesenchyme, whereas CYP26B1 transcripts are detected in the developing lung, kidney, spleen, thymus, testis, and specifically in dermis surrounding the developing hair follicles (2). At the same stages, CYP26C1 expression is found in the inner ear and tooth buds (100).

As CYP26 isozymes function to catalyze the oxidation of RA to less active metabolites, any ablation of these enzymes may result in abnormalities similar to those observed in RA or vitamin A toxicity. Whereas null mutations of the genes for CYP26A1 (1, 91) and CYP26B1 (123) are lethal, the CYP26C1 gene seems to be nonessential because CYP26C1-null mice lack any particular phenotype and appear to behave like wild-type mice (108). CYP26A1-null mouse fetuses die at mid-late gestation, with multiple organ defects similar to those observed in excess RA signaling resulting from excessive intake of vitamin A or use of RA (1, 91). Abnormalities include spina bifida, caudal regression patterning, hindbrain defects, and embryonic transformations. CYP26B1-null mice that are born alive die right after birth due to respiratory defects (123). CYP26B1 is normally expressed during limb bud development (52), and limb bud development is defective in CYP26B1-null mutants (123). Consistent with a critical role of CYP26B1 in normal male germ cell development (9), CYP26B1-null mice have smaller testes and lack any germ cells, indicating that CYP26B1 not only acts as a meiotic inhibiting factor but also is essential for germ cell survival, apparently by preventing premature exposure to RA (9, 53, 76). Despite CYP26C1-null mouse mutants not showing a particular phenotype, the loss of this gene in combination with the other two members of CYP26 family exacerbated the teratogenic effects of RA on embryonic development (76, 108). Overall, the differences among CYP26A1, CYP26B1, and CYP26C1 in their expression patterns, timing of expression, and consequences of gene deletion, together with the conservation of all three genes in all vertebrates studied, imply that CYP26A1 and CYP26B1 are essential for survival, but in different ways, while CYP26C1 confers a protective advantage against excessive RA signaling that may be tissue specific.

CYP26A1 expression and potential function has also been studied in embryonic stem (ES) cells undergoing differentiation. In undifferentiated ES cells, removal of leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), which functions to prevent differentiation, resulted in increased CYP26A1 expression and increased conversion of all-trans-retinol to 4-oxo-retinol; however, neither RA nor 4-oxo-RA were detected (43). In another study using AB1 ES cells, the disruption of both alleles of the CYP26A1 gene by homologous recombination resulted in an 11-fold higher concentration of intracellular RA in cells treated 48 hours earlier with RA together with reduced expression of RA-responsive genes involved in cell differentiation (44). Thus, the expression of CYP26A1, through regulation of retinoid concentrations in undifferentiated pluripotent ES cells, is important for their differentiation, which may involve CYP26-produced metabolites of retinol as well as of RA.

OTHER CYP FAMILIES WITH RETINOIC ACID–METABOLIZING ACTIVITY

Well before the CYP26 family was identified, at-RA-4-hydroxylation activity was known (24, 46, 47, 55). Most of the research on at-RA-4-hydroxylation has focused on the liver owing to its major role in the cytochrome P450–mediated detoxification of many bioactive metabolites. In human liver, the capacity for hepatic at-RA-4-hydroxylation activity seems to vary among individuals. For example, RA-4-hydroxylation activity measured in microsomal samples from 19 different liver transplantation donors ranged about sevenfold (61), and, comparatively, in a recent study testing hepatic microsomal activity among 37 individuals the variation was ~100-fold (105). Substrate affinity (Km values for at-RA) and maximum velocity also differed considerably among individuals within studies (59, 61). At present, little information exists on the reasons for this variation. Activities have also differed among studies, which may be attributable to differences in substrate concentrations used or other assay factors.

As liver is the major site of at-RA-4-hydroxylation, several hepatic CYP isoforms have been analyzed so far for their relative contributions, using assays of liver microsomes, transfected lymphoid or HEK293 cells, or enzymes in supersome assembly. Among them, significant RA-4-hydroxylation activity was observed for CYP3A4, 3A5, 3A7, 2C8, 2C9, 2C22, and 2C39 (3, 46, 54, 59, 61, 79, 105). In two separate studies using either microsomes from insect cells transformed with cDNA of human CYPs (61) or microsomal fractions of lymphoid cells transfected with individual human CYP cDNA (59), CYP2C8 was shown to be more efficient than either CYP2C9 or CYP3A4 isozymes in at-RA-4-hydroxylation. However, the total contribution of CYP3A4 in at-RA-4-hydroxylation in liver may not be greatly different from CYP2C8 because CYP3A4 represents about 20% to 30% of the total CYP in the liver, whereas CYP2C8 constitutes only 2% (59). In a study comparing CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, and CYP3A7 in the microsomal fraction of lymphoblasts and HEK293 cells transfected with human CYP cDNAs, CYP3A7 was the most active isoform for the formation of all three metabolites of at-RA oxidation including 4-hydroxy-RA, 4-oxo-RA, and 18-hydroxy-RA (54).

Recently, a kinetic comparison of CYP26 isoforms to other CYPs with the potential for RA-4-hydoxylation has been reported (105). First, in a comparison study of 12 different purified CYP450 isoforms tested in supersome form for oxidative conversion of at-RA to 4-hydroxy-RA as the primary product, in a reaction containing NADPH, P450 reductase, and 10 μM at-RA, CYP2C8, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, and CYP3A7 had significant 4-hydroxylase activity and therefore were further evaluated kinetically (105). The Km values for at-RA-4-hydroxylation for all four of these CYPs were similar, in the range of 11.1 to 19.4 μM, and Vmax values equaled 2.3 to 4.9 pmol/min/pmol P450. Comparatively, the Km and Vmax values for at-RA 4-hydroxylation by purified CYP26A1 in supersomes were 9.4 nM, nearly three orders of magnitude lower than those above, and 11.3 pmol/min/pmol P450, respectively. On the basis of these results, CYP2C8, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, and CYP3A7 were calculated to have similar clearance activities to each other, all in the range of 0.2 to 0.4 μl/min/pmol P450. These rates are much lower than the clearance rate of 1.2 ml/min/pmol P450 calculated for CYP26A1. Based on the concentrations of individual CYPs in the liver and these kinetic data, CYP26A1 was predicted to be the primary CYP for the hepatic clearance of at-RA at both endogenous and therapeutic concentrations (105). In the absence of CYP26A1, however, CYP3A isoforms, and specifically CYP3A4, are proposed to be the primary enzyme responsible for RA hydroxylation for clearance (105).

The oxidative metabolism of RA has also been studied in rodent models. Among rodent CYP2C subfamily members, CYP2C7, CYP2C22, and CYP2C39 exhibit catalytic activity toward RA oxidation (3, 46, 79). Mouse CYP2C39 expressed in Escherichia coli has a relatively high affinity for at-RA with a Km of 0.8 μM, but a low Vmax of 48 fmol/min/pmol P450, as compared to other CYP2C subfamily members (3). Apparently, the expression of the enzyme is repressed in the liver of mice lacking the aryl hydrocarbon receptor gene (3), indicating that the expression of the gene may be controlled by xenobiotics. The rat CYP2C22, an ortholog of human CYP2C8 and CYP2C9, is expressed nearly exclusively in the liver and was recently reported to metabolize at-RA when expressed in HEK293 cells (79). Like CYP26A1, CYP2C22 mRNA is increased in the liver by vitamin A and exogenous RA (89). The CYP2C22 promoter region contains a DR-5 RARE located about 2 kbp upstream of the transcription start site (79). Under normal dietary conditions, the relative level of CYP2C22 mRNA expression exceeds that of CYP26A1 by about 100 fold (89). Thus, CYP26A1, due to its strong and rapid induction by at-RA in the liver, as discussed above, may function as an “emergency CYP” that responds most dynamically to an increase in hepatic RA concentration, whereas CYP2C22 could be important in maintaining a low level of RA under basal conditions. Kinetically, CYP26A1, CYP26B1, and CYP2C22 mRNAs all increased rapidly in the liver in response to treatment with RA, as early as 30 minutes after RA administration, and reached a maximum at about 6–10 hours. However, the CYP2C22 mRNA level stayed elevated longer than either CYP26A1 or CYP26B1 mRNA. These results imply that multiple CYP activities are present in the liver and are regulated simultaneously in response to an influx of RA. In vitro, microsomes from HEK293T cells transfected with CYP2C22 metabolized 3H-at-RA to polar retinoids (79). Interestingly, the metabolism of 3H-at-RA was effectively inhibited by 9-cis-RA and certain long-chain fatty acids, although 3H-9-cis-RA itself was poorly metabolized. These results suggest that 9-cis-RA and long-chain fatty acids could function as inhibitors or competitors of this CYP isoform.

EFECTS OF BIOLOGICAL AGENTS AND DISEASE STATES ON CYP EXPRESSION AND RETINOIC ACID METABOLISM

CYP enzymes in general are often affected by many factors besides compounds that are considered to be their specific inducers or substrates. A limited number of studies have examined whether the oxidative metabolism of RA is affected by the use of bioactive compounds or drugs and whether agonists for other nuclear receptors, such as PPARs, might alter the induction of CYP26 gene expression by retinoids.

Metabolic Stress

The ability of vitamin A and RA to induce CYP26 expression, as studied mainly in the liver, is influenced by the health status of the organism and also by the presence of certain bioactive compounds. The metabolism of vitamin A is disturbed during inflammation and infection, as evidenced by reductions in plasma retinol and plasma retinol–binding protein during infection and inflammation (88, 97, 113). Originally, it was found that the induction of CYP26A1 mRNA expression by at-RA was highly suppressed in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-treated THP-1 human monocytic cells (13), and similar studies in intact rats showed that the induction of CYP26A1 and CYP26B1 mRNA expression by orally administered RA is greatly attenuated in the liver of rats treated with LPS (125). However, no significant change was observed in the mRNA levels of either CYP26A1 or CYP26B1 in the liver of control rats treated only with LPS. This may be due to the low levels of expression of these genes in the liver under normal dietary regimens.

Drug-Retinoid Interactions

Apparently, smoking and alcohol use do not significantly affect the RA-4-hydroxylation activity as measured in human liver specimens (61), although chronic alcohol use influences the storage of vitamin A in the liver. However, these factors have not been specifically evaluated regarding effects on the CYP26 family.

RA-4-hydroxylation activity in hepatic microsomes was inhibited by more than 75% by parathion, a potent insecticide; by 50% by quinidine, a heart antiarrhythmic drug; and by 30% by ketoconazole, a general inhibitor of cytochrome P450 enzymes (61). The inhibitory effects of drugs on RA metabolism appears to be consistent with findings of lower serum concentration of at-RA and 13-cis-RA (21) and their metabolites, including 13-cis-4-oxo-RA (64) in patients using anticonvulsant drugs, such as phentoin, carbamazepine, and valporate, and antiepileptic drugs.

Although the contributions of CYP2C and CYP3A subfamily members to the hepatic clearance of RA may be less than for CYP26A1 (105), they may have an influence on the metabolism of therapeutic levels of RA. As the CYP2C and CYP3A isoforms have apparently wider specificity in the metabolism of drugs, an important question is whether the coadministration of RA during therapy with some drugs may cause some kind of drug-RA interaction. CYP2C8 is involved in biotransformation of several widely used drugs such as taxol, tolbutamide, and warfarin, and RA has been shown to be a potent inhibitor of this reaction (122). The CYP3A subfamily is involved in the biotransformation of tamoxifen (34), a commonly used anticancer drug. These CYP3A isozymes were highly induced by RA, which may cause enhanced catabolism of the drug (37).

Other bioactive compounds may also alter the regulation of CYP26 genes or the metabolism of RA. In a study of Caco-2 human colon carcinoma cells, treatment with phytanic acid and docosahexaenoic acid, activators of PPARα and agonists for RXRα, together with either at-RA or Am580, the specific agonist for RARα, increased CYP26A1 mRNA more than did treatment with either at-RA or Am580 alone (42). Recently, clofibrate, a specific PPARα agonist, was shown to suppress the mRNA expression of both CYP26A1 and CYP26B1 in HepG2 cells incubated with low concentration of at-RA (104). In the same report, however, ligands for both PPARγ (rosiglitazone and pioglitazone) and PPARβ/δ (L-165,041) dramatically and dose-dependently increased CYP26B1 mRNA in HepG2 cells incubated with at-RA. These ligands had much lower effect on CYP26A1 than on CYP26B1 (104). In parallel to these results, the CYP26B1, but not CYP26A1, transcript was higher in individual donors positive for fatty liver than in donors negative for fatty liver (104). In contrast to the latter results, a separate study showed that CYP26A1 transcripts were about seven to nine times higher in the individuals with simple and nonalcoholic fatty liver steatosis disease than in normal individuals (4).

Ischemia, as another factor, may also affect the expression of CYP26A1 but not CYP26B1 (104). The CYP26A1 mRNA transcript has been shown to be significantly lower in the livers of ischemic versus nonischemic individual livers.

A deficiency of vitamin A has long been associated with carcinogenesis, and several studies have shown an up-regulation of CYP26A1 mRNA expression in cancer cell types and tumors in vivo (94, 110). A concomitant decrease in the level of RA and increase in CYP26A1 mRNA has been shown in Barrett's associated dysplasia and esophagus adenocarcinoma, both in vitro and in vivo (11). CYP26A1 mRNA was elevated in 42% of primary breast cancer specimens (72). The enhanced expression of CYP26A1 suppressed cellular responses to anoikis and consequently resulted in promotion of anchorage-independent growth, whereas suppression of CYP26A1 by a specific siRNA reversed the oncogenicity, suggesting a direct link between RA signaling and tumorigenicity.

Inhibition of the Catalytic Activity of CYP26 by Specific Compounds

The antiproliferative properties of RA make it a drug of choice for the treatment of various disorders including leukemia, skin disorders such as psoriasis and acne, as well as an emerging therapy for conditions such as atherosclerosis (16, 23, 35, 103). Because RA is a specific substrate and a potent inducer for both CYPA1 and CYPB1, the long-term use of RA may result in the development of resistance to RA therapy. Therefore, a better therapeutic approach for those disorders could be to inhibit the catalytic actions of CYP26 enzymes. Such an idea has led to the development of RA metabolism–blocking agents (RAMBAs). A number of RAMBAs have been developed with high potency for inhibiting the metabolism of at-RA (for comprehensive reviews, see 56, 69). Among them, for example, are compounds R116010 and R115866. R116010 enhances the biological activity of at-RA and exhibited antitumor activity in a mouse mammary carcinoma model (109), whereas a single oral dose of R115866 in intact rats resulted in increases in endogenous tissue RA levels in plasma, skin, fat, kidney, and testis, and as a result R115866 exerted retinoidal activities (98). Compound R115866 has also been shown to be effective in treating skin disorders, to potentially increase the endogenous level of RA in the keratinocytes and epidermis (28, 74), and to increase retinoid signaling in intimal smooth muscle cells, which is postulated to offer potential new therapeutic ways to treat vascular proliferative disorders (70). In organotypic organ cultures of human skin, the addition of the cytochrome P450 inhibitors liarozole and talarozole in the presence of a very low concentration of RA (1 nM) increased CYP26A1 expression (73), which may be due to the build up of RA to a sufficient level to activate nuclear receptors and thus increase transactivation of the CYP26A1 gene.

SUMMARY POINTS

The mode of regulation has been discovered for relatively few of the more than 500 genes that have shown to be regulated by RA under various physiological conditions. Of these few, CYP26A1 is the most responsive to at-RA, at least in liver and certain cell types, and its mode of regulation through RAREs has been partially defined. It is also likely to be a major player in the clearance of RA, based on studies of RA-4-hydroxylase by expressed human CYP enzymes.

CYP26A1 and CYP26B1 exhibit nutritional regulation according to vitamin A status. They are both strongly regulated by at-RA in cells and the intact organism.

The CYP26 family plays critical roles in development. Studies in knockout mice have demonstrated that CYP26A1 is essential for the development of the embryo, CYP26B1 is essential for postnatal survival, and CYP26C1 can be eliminated without causing a major phenotype, but it still appears to contribute positively by reducing the sensitivity of the embryo to excessive RA. CYP26B1 also plays a unique role in male germ cell development, serving to restrain RA signaling in embryonic testis and thus to prevent premature meiosis.

CYP2C22, a liver-specific gene in the rat that is orthologous to human CYP2C8 and possibly CYP2C9, also responds physiologically to increases in at-RA concentration and possesses an RARE through which its expression is induced. 9-cis-RA and long-chain fatty acids inhibit its activity, suggesting potential interactions.

Interactions between the metabolism of RA and that of medically important drugs are suggested by a variety of studies, but little is yet known of the pathways through which drugs may affect retinoid homeostasis. When RA is used pharmacologically, it could potentially alter the expression of CYPs (such as CYP2C8) that also metabolize other drugs. Thus, further studies on interactions are needed.

Cancer cell studies in which suppressing CYP26A1 expression has reduced tumorigenicity, as well as studies using RAMBAs, suggest that strategies to limit the ability of CYP26 enzymes to clear RA may have an important place in retinoid therapy in the future.

FUTURE ISSUES

For CYP26A1, although important DNA elements have been mapped and tested for functionality, the regulation of the gene at the level of complex chromatin structure has not been determined. Given the very strong regulation of this gene by at-RA, CYP26A1 appears to be an ideal model for future studies at the chromatin level.

Evidence suggests that CYP26A1, CYP26B1, and CYP26C1 fulfill different functions, based on developmental studies and on nonidentical tissue distributions in the adult vertebrate, but their specific functions are not well defined. The discovery that CYP26B1 is essential in germ cell development provides strong evidence that CYP26B1 serves a different purpose from the other CYP26 family genes including CYP26A1, even though enzyme studies have demonstrated similar catalytic activities of CYP26A1 and CYP26B1 toward at-RA, and they are coexpressed in some tissues (e.g., liver, lung). Moreover, studies of gene expression have been conducted mainly at the organ/tissue level. Future research is needed to understand the cell-specific expression and regulation of the CYP26 genes.

CYP26 genes typically show not only a rapid increase in mRNA in response to treatment with RA in vivo or in cells, but also a rapid decrease in mRNA after induction. Currently, there is little understanding of the regulation of the CYP genes at the post-mRNA levels. Similarly, although progress has been made in better understanding the catalysis of RA oxidation, there is still inadequate understanding of what controls protein levels and none on the process of CYP protein translation and any possible translational or post-translational control of CYP proteins.

Many members of the cytochrome P450 superfamily have been shown to utilize substrates other than those for which they are named, and it cannot be concluded that the CYP26 family exclusively metabolizes RA; thus, additional enzyme studies using other substrates as competitors, especially structurally similar substrates such as long-chain fatty acids, should be conducted.

Evidence suggests there is considerable person-to-person variability in the ability of liver microsomes to oxidize at-RA. Polymorphisms are known, but population-genetic studies and the effects of polymorphisms on vitamin A requirements or RA used pharmacologically should be conducted. And since RA is used clinically, and CYP2C genes (e.g., human CYP2C8) are well known to metabolize many clinically important drugs and can also oxidize RA, the potential for RA–drug interactions seems imminent. Thus, additional studies with patient samples and/or in vitro studies to investigate retinoid–drug interactions and the effects of CYP26 gene polymorphisms are likely to yield important new information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant CA-90214. The authors wish to thank the members of their laboratory who have contributed to research cited in this review.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

Glossary

- Retinoic acid receptor (RAR)

a family of three nuclear receptor genes, RARα, β, and γ, that are expressed differentially in a wide variety of cells. Of the three types, RARα has the widest tissue distribution. All three bind at-RA as ligand. The binding of an RAR protein to an RXR protein forms a heterodimeric receptor complex that binds to specific elements in DNA, termed retinoic acid response elements. [See (5, 6, 10, 22, 115) for further details on RAR proteins and genes regulated by RARs]

- Retinoid X receptor (RXR)

the retinoid X receptor family comprises three nuclear receptor genes, RXRα, β, and γ, that are expressed differentially in a wide variety of cells. RXRα has the widest distribution. Their physiological ligand, which is still debatable, may be 9-cis-RA or a long-chain fatty acid, or they may not require a ligand. The RXRs form heterodimers not only with RAR proteins, but also with several other nuclear receptor proteins including peroxisome proliferator-activator receptors

- Retinoic acid response element (RARE)

a specific DNA sequence to which RAR-RXR heterodimers bind in a manner that regulates gene transcription. The canonical RARE consists of two hexameric sequences, (A/G)G(G/T)TCA, also known as half sites, that are spaced by 2 or 5 intervening nucleotides [this type of RARE is referred to as direct repeat (DR), e.g., DR-2 or DR-5]. However, sequences differing from this have also been shown to act in a functional manner as an RARE

- CYP

cytochrome P450 gene or protein

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Abu-Abed S, Dollé P, Metzger D, Beckett B, Chambon P, Petkovich M. The retinoic acid-metabolizing enzyme, CYP26A1, is essential for normal hindbrain patterning, vertebral identity, and development of posterior structures. Genes Dev. 2001;15:226–40. doi: 10.1101/gad.855001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abu-Abed S, MacLean G, Fraulob V, Chambon P, Petkovich M, Dollé P. Differential expression of the retinoic acid-metabolizing enzymes CYP26A1 and CYP26B1 during murine organogenesis. Mech. Dev. 2002;110:173–77. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00572-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreola F, Hayhurst GP, Luo G, Ferguson SS, Gonzalez FJ, et al. Mouse liver CYP2C39 is a novel retinoic acid 4-hydroxylase. Its down-regulation offers a molecular basis for liver retinoid accumulation and fibrosis in aryl hydrocarbon receptor-null mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:3434–38. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305832200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashla AA, Hoshikawa Y, Tsuchiya H, Hashiguchi K, Enjoji M, et al. Genetic analysis of expression profile involved in retinoid metabolism in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatol. Res. 2010;40:594–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2010.00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balmer JE, Blomhoff R. Gene expression regulation by retinoic acid. J. Lipid Res. 2002;43:1773–808. doi: 10.1194/jlr.r100015-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bastien J, Rochette-Egly C. Nuclear retinoid receptors and the transcription of retinoid-target genes. Gene. 2004;328:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blomhoff R, Blomhoff HK. Overview of retinoid metabolism and function. J. Neurobiol. 2006;66:606–30. doi: 10.1002/neu.20242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowles J, Knight D, Smith C, Wilhelm D, Richman J, et al. Retinoid signaling determines germ cell fate in mice. Science. 2006;312:596–600. doi: 10.1126/science.1125691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Provides novel insight into the role of CYP26B1 expression in delaying male germ cell maturation (see also Reference 36).

- 9.Bowles J, Koopman P. Retinoic acid, meiosis and germ cell fate in mammals. Development. 2007;134:3401–11. doi: 10.1242/dev.001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chambon P. A decade of molecular biology of retinoic acid receptors. FASEB J. 1996;10:940–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang CL, Hong E, Lao-Sirieix P, Fitzgerald RC. A novel role for the retinoic acid-catabolizing enzyme CYP26A1 in Barrett's associated adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. 2008;27:2951–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapman JS, Weiss KL, Curley RWJ, Highland MA, Clagett-Dame M. Hydrolysis of 4-HPR to atRA occurs in vivo but is not required for retinamide-induced apoptosis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2003;419:234–43. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Q, Ma Y, Ross AC. Opposing cytokine-specific effects of all trans-retinoic acid on the activation and expression of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)-1 in THP-1 cells. Immunology. 2002;107:199–208. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01485.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cifelli CJ, Ross AC. Chronic vitamin A status and acute repletion with retinyl palmitate are determinants of the distribution and catabolism of all-trans-retinoic acid in rats. J. Nutr. 2007;137:63–70. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clagett-Dame M, DeLuca HF. The role of vitamin A in mammalian reproduction and embryonic development. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2002;22:347–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.010402.102745E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Thé H, Chen Z. Acute promyelocytic leukaemia: novel insights into the mechanisms of cure. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2010;10:775–83. doi: 10.1038/nrc2943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeLuca HF. Retinoic acid metabolism. Fed. Proc. 1979;38:2519–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeLuca HF, Roberts AB. Pathways of retinoic acid and retinol metabolism. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1969;22:945–52. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/22.7.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duester G. Retinoic acid synthesis and signaling during early organogenesis. Cell. 2008;134:921–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunagin PEJ, Zachman RD, Olson JA. The identification of metabolites of retinal and retinoic acid in rat bile. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1966;124:71–85. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(66)90314-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fex G, Larsson K, Andersson A, Berggren-Söderlund M. Low serum concentration of all-trans and 13-cis retinoic acids in patients treated with phenytoin, carbamazepine and valproate. Possible relation to teratogenicity. Arch. Toxicol. 1995;69:572–74. doi: 10.1007/s002040050215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fields AL, Soprano DR, Soprano KJ. Retinoids in biological control and cancer. J. Cell Biochem. 2007;102:886–98. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher GJ, Voorhees JJ. Molecular mechanisms of retinoid actions in skin. FASEB J. 1996;10:1002–13. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.9.8801161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frolik CA, Roberts AB, Tavela TE, Roller PP, Newton DL, Sporn MB. Isolation and identification of 4-hydroxy- and 4-oxoretinoic acid. In vitro metabolites of all-trans-retinoic acid in hamster trachea and liver. Biochemistry. 1979;18:2092–97. doi: 10.1021/bi00577a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frolik CA, Tavela TE, Sporn MB. Separation of the natural retinoids by high-pressure liquid chromatography. J. Lipid Res. 1978;19:32–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujii H, Sato T, Kaneko S, Gotoh O, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, et al. Metabolic inactivation of retinoic acid by a novel P450 differentially expressed in developing mouse embryos. EMBO J. 1997;16:4163–73. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.14.4163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaemers IC, van Pelt AM, van der Saag PT, de Rooij DG. All-trans-4-oxo-retinoic acid: a potent inducer of in vivo proliferation of growth-arrested A spermatogonia in the vitamin A-deficient mouse testis. Endocrinology. 1996;137:479–85. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.2.8593792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giltaire S, Herphelin F, Frankart A, Hérin M, Stoppie P, Poumay Y. The CYP26 inhibitor R115866 potentiates the effects of all-trans retinoic acid on cultured human epidermal keratinocytes. Br. J. Dermatol. 2009;160:505–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guerquin M-J, Duquenne C, Lahaye J-B, Tourpin S, Habert R, Livera G. New testicular mechanisms involved in the prevention of fetal meiotic initiation in mice. Dev. Biol. 2010;346:320–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hänni R, Bigler F. Isolation and identification of three major metabolites of retinoic acid from rat feces. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1977;60:881–87. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19770600317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hänni R, Bigler F, Meister W, Englert G. Isolation and identification of three urinary metabolites of retinoic acid in the rat. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1976;59:2221–27. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19760590636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hollemann T, Chen Y, Grunz H, Pieler T. Regionalized metabolic activity establishes boundaries of retinoic acid signalling. EMBO J. 1998;17:7361–72. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.HomoloGene Release 65 Statistics. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/homologene.

- 34.Jacolot F, Simon I, Dreano Y, Beaune P, Riche C, Berthou F. Identification of the cytochrome P450 IIIA family as the enzymes involved in the N-demethylation of tamoxifen in human liver microsomes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1991;41:1911–19. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90131-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang SJ, Campbell LA, Berry MW, Rosenfeld ME, Kuo C. Retinoic acid prevents Chlamydia pneumoniae-induced foam cell development in a mouse model of atherosclerosis. Microbes Infect. 2008;10:1393–97. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.John KV, Lakshmanan MR, Cama HR. Preparation, properties and metabolism of 5,6-monoepoxyretinoic acid. Biochem. J. 1967;103:539–43. doi: 10.1042/bj1030539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jurima-Romet M, Neigh S, Casley WL. Induction of cytochrome P450 3A by retinoids in rat hepatocyte culture. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 1997;16:198–203. doi: 10.1177/096032719701600407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kipp JL, Golebiowski A, Rodriguez G, Demczuk M, Kilen SM, Mayo KE. Gene expression profiling reveals Cyp26b1 to be an activin regulated gene involved in granulosa cell proliferation. Endocrinology. 2011;152:303–12. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koubova J, Menke DB, Zhou Q, Capel B, Griswold MD, Page DC. Retinoic acid regulates sex-specific timing of meiotic initiation in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:2474–79. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510813103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Provides novel insight into the role of CYP26B1 expression in delaying male germ cell maturation (see also Reference 8).

- 40.Krüger KA, Blum JW, Greger DL. Expression of nuclear receptor and target genes in liver and intestine of neonatal calves fed colostrum and vitamin A. J. Dairy Sci. 2005;88:3971–81. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)73083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumar S, Chatzi C, Brade T, Cunningham TJ, Zhao X, Duester G. Sex-specific timing of meiotic initiation is regulated by Cyp26b1 independent of retinoic acid signaling. Nat. Commun. 2011;2:151. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lampen A, Meyer S, Nau H. Phytanic acid and docosahexaenoic acid increase the metabolism of all-trans-retinoic acid and CYP26 gene expression in intestinal cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1521:97–106. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(01)00305-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lane MA, Chen AC, Roman SD, Derguini F, Gudas LJ. Removal of LIF (leukemia inhibitory factor) results in increased vitamin A (retinol) metabolism to 4-oxoretinol in embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:13524–29. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Langton S, Gudas LJ. CYP26A1 knockout embryonic stem cells exhibit reduced differentiation and growth arrest in response to retinoic acid. Dev. Biol. 2008;315:331–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Provides genetic evidence that CYP26-regulated RA levels can modulate the phenotype of cancer cells

- 45.Lee SJ, Perera L, Coulter SJ, Mohrenweiser HW, Jetten A, Goldstein JA. The discovery of new coding alleles of human CYP26A1 that are potentially defective in the metabolism of all-trans retinoic acid and their assessment in a recombinant cDNA expression system. Pharmacogenet. Genomics. 2007;17:169–80. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32801152d6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leo MA, Iida S, Lieber CS. Retinoic acid metabolism by a system reconstituted with cytochrome P-450. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1984;234:305–12. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(84)90353-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leo MA, Lasker JM, Raucy JL, Kim CI, Black M, Lieber CS. Metabolism of retinol and retinoic acid by human liver cytochrome P450IIC8. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1989;269:305–12. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(89)90112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lippel K, Olson JA. Biosynthesis of beta-glucuronides of retinol and of retinoic acid in vivo and in vitro. J. Lipid Res. 1968;9:168–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Loudig O, Babichuk C, White J, Abu-Abed S, Mueller C, Petkovich M. Cytochrome P450RAI(CYP26) promoter: a distinct composite retinoic acid response element underlies the complex regulation of retinoic acid metabolism. Mol. Endocrinol. 2000;14:1483–97. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.9.0518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Loudig O, Maclean GA, Dore NL, Luu L, Petkovich M. Transcriptional co-operativity between distant retinoic acid response elements in regulation of Cyp26A1 inducibility. Biochem. J. 2005;392:241–48. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Provides evidence that the CYP26A1 promoter is “autoregulated” by RA through the interaction of proximal and distal RAREs.

- 51.Lutz JD, Dixit V, Yeung CK, Dickmann LJ, Zelter A, et al. Expression and functional characterization of cytochrome P450 26A1, a retinoic acid hydroxylase. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2009;77:258–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.MacLean G, Abu-Abed S, Dollé P, Tahayato A, Chambon P, Petkovich M. Cloning of a novel retinoic-acid metabolizing cytochrome P450, Cyp26B1, and comparative expression analysis with Cyp26A1 during early murine development. Mech. Dev. 2001;107:195–201. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00463-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.MacLean G, Li H, Metzger D, Chambon P, Petkovich M. Apoptotic extinction of germ cells in testes of Cyp26b1 knockout mice. Endocrinology. 2007;148:4560–67. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marill J, Cresteil T, Lanotte M, Chabot GG. Identification of human cytochrome P450s involved in the formation of all-trans-retinoic acid principal metabolites. Mol. Pharmacol. 2000;58:1341–48. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.6.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martini R, Murray M. Participation of P450 3A enzymes in rat hepatic microsomal retinoic acid 4-hydroxylation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1993;303:57–66. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCaffery P, Simons C. Prospective teratology of retinoic acid metabolic blocking agents (RAMBAs) and loss of CYP26 activity. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2007;13:3020–37. doi: 10.2174/138161207782110534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McCormick AM, Napoli JL, Deluca HF. High-pressure liquid chromatographic resolution of vitamin A compounds. Anal. Biochem. 1978;86:25–33. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90315-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCormick AM, Napoli JL, Schnoes HK, DeLuca HF. Isolation and identification of 5, 6-epoxyretinoic acid: a biologically active metabolite of retinoic acid. Biochemistry. 1978;17:4085–90. doi: 10.1021/bi00612a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McSorley LC, Daly AK. Identification of human cytochrome P450 isoforms that contribute to all-trans-retinoic acid 4-hydroxylation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2000;60:517–26. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00356-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Means AL, Gudas LJ. The roles of retinoids in vertebrate development. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1995;64:201–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.001221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nadin L, Murray M. Participation of CYP2C8 in retinoic acid 4-hydroxylation in human hepatic microsomes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999;58:1201–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Napoli JL. Retinoic acid: its biosynthesis and metabolism. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 1999;63:139–88. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60722-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Napoli JL, McCormick AM, Schnoes HK, DeLuca HF. Identification of 5,8-oxyretinoic acid isolated from small intestine of vitamin A-deficient rats dosed with retinoic acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1978;75:2603–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.6.2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nau H, Tzimas G, Mondry M, Plum C, Spohr HL. Antiepileptic drugs alter endogenous retinoid concentrations: a possible mechanism of teratogenesis of anticonvulsant therapy. Life Sci. 1995;57:53–60. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00242-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nebert DW, Russell DW. Clinical importance of the cytochromes P450. Lancet. 2002;360:1155–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nelson DR. A second CYP26 P450 in humans and zebrafish: CYP26B1. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999;371:345–47. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Niederreither K, Abu-Abed S, Schuhbaur B, Petkovich M, Chambon P, Dollé P. Genetic evidence that oxidative derivatives of retinoic acid are not involved in retinoid signaling during mouse development. Nat. Genet. 2002;31:84–88. doi: 10.1038/ng876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Niederreither K, Dollé P. Retinoic acid in development: towards an integrated view. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008;9:541–53. doi: 10.1038/nrg2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Njar VC, Gediya L, Purushottamachar P, Chopra P, Vasaitis TS, et al. Retinoic acid metabolism blocking agents (RAMBAs) for treatment of cancer and dermatological diseases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006;14:4323–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Reviews progress in the development of RAMBAs to inhibit RA metabolism and enhance treatment effects of RA.

- 70.Ocaya P, Gidlöf AC, Olofsson PS, Törmä H, Sirsjö A. CYP26 inhibitor R115866 increases retinoid signaling in intimal smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007;27:1542–48. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.106.138602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ocaya PA, Elmabsout AA, Olofsson PS, Törmä H, Gidlöf AC, Sirsjö A. CYP26B1 plays a major role in the regulation of all-trans-retinoic acid metabolism and signaling in human aortic smooth muscle cells. J. Vasc. Res. 2010;48:23–30. doi: 10.1159/000317397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Osanai M, Sawada N, Lee GH. Oncogenic and cell survival properties of the retinoic acid metabolizing enzyme, CYP26A1. Oncogene. 2010;29:1135–44. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pavez Loriè E, Chamcheu JC, Vahlquist A, Törmä H. Both all-trans retinoic acid and cytochrome P450 (CYP26) inhibitors affect the expression of vitamin A metabolizing enzymes and retinoid biomarkers in organotypic epidermis. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2009;301:475–85. doi: 10.1007/s00403-009-0937-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pavez Loriè E, Cools M, Borgers M, Wouters L, Shroot B, et al. Topical treatment with CYP26 inhibitor talarozole (R115866) dose dependently alters the expression of retinoid-regulated genes in normal human epidermis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2009;160:26–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pavez Loriè E, Li H, Vahlquist A, Törmä H. The involvement of cytochrome p450 (CYP) 26 in the retinoic acid metabolism of human epidermal keratinocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1791:220–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pennimpede T, Cameron DA, MacLean GA, Li H, Abu-Abed S, Petkovich M. The role of CYP26 enzymes in defining appropriate retinoic acid exposure during embryogenesis. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2010;88:883–94. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Reviews progress in understanding the roles of RA and the CYP26 enzymes during embryogenesis.

- 77.Pijnappel WW, Hendriks HF, Folkers GE, van den Brink CE, Dekker EJ, et al. The retinoid ligand 4-oxo-retinoic acid is a highly active modulator of positional specification. Nature. 1993;366:340–44. doi: 10.1038/366340a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Popa C, Dicker AJ, Dahler AL, Saunders NA. Cytochrome P450, CYP26AI, is expressed at low levels in human epidermal keratinocytes and is not retinoic acid-inducible. Br. J. Dermatol. 1999;141:460–68. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.03039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Qian L, Zolfaghari R, Ross AC. Liver-specific cytochrome P450 CYP2C22 is a direct target of retinoic acid and a retinoic acid-metabolizing enzyme in rat liver. J. Lipid Res. 2010;51:1781–92. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M002840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ray WJ, Bain G, Yao M, Gottlieb DI. CYP26, a novel mammalian cytochrome P450, is induced by retinoic acid and defines a new family. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:18702–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Reijntjes S, Blentic A, Gale E, Maden M. The control of morphogen signalling: regulation of the synthesis and catabolism of retinoic acid in the developing embryo. Dev. Biol. 2005;285:224–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Reijntjes S, Gale E, Maden M. Generating gradients of retinoic acid in the chick embryo: Cyp26C1 expression and a comparative analysis of the Cyp26 enzymes. Dev. Dyn. 2004;230:509–17. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Roberts AB, DeLuca HF. Pathways of retinol and retinoic acid metabolism in the rat. Biochem. J. 1967;102:600–5. doi: 10.1042/bj1020600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Roberts AB, Frolik CA. Recent advances in the in vivo and in vitro metabolism of retinoic acid. Fed. Proc. 1979;38:2524–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]