Abstract

In phosphorothioate containing dsDNA-oligomers (S-oligomers), one of the two non-bridging oxygen atoms in the phosphate moiety of sugar-phosphate backbone is replaced by sulphur. In this work, electron spin resonance (ESR) studies of one-electron oxidation of several S-oligos by Cl2•− at low temperatures are investigated. Electrophilic addition of Cl2•− to phosphorothioate with elimination of Cl− leads to the formation of a 2-center three-electron σ2σ*1 bonded adduct radical (-P-S∸Cl). In AT S-oligomers with mutiple phosphorothioates, i.e., d[ATATAsTsAsT]2, -P-S∸Cl reacts with a neighboring phosphorothioate to form the σ2σ*1 bonded disulphide anion radical ([-P-S∸S-P-]−). With AT S-oligomers with a single phosphorothioate, i.e., d[ATTTAsAAT]2, reduced levels of conversion of -P-S∸Cl dsDNA [-P-S∸S-P-]− are found. For guanine containing S-oligomers containing one phosphorothioate, -P-S∸Cl results in one-electron oxidation of guanine base but not of A, C, or T thereby leading to selective hole transfer to G. The redox potential of -P-S∸Cl is thus higher than that of G but is lower than those of A, C, and T. Spectral assignments to -P-S∸Cl and [-P-S∸S-P-]− are based on reaction of Cl2•− with the model compound diisopropyl phosphorothioate. The results found for d[TGCGsCsGCGCA]2 suggest that [-P-S∸S-P-]− undergoes electron transfer to the one-electron oxidized G healing the base but producing a cyclic disulfide bonded backbone with a substantial bond strength (50 kcal/mol). Formation of -P-S∸Cl and its conversion to [-P-S∸S-P-]− is found to be unaffected by O2 and this is supported by the theoretically calculated electron affinities and reduction potentials of [-P-S-S-P-] and O2.

Introduction

Ionizing radiation is known to induce frank DNA-strand breaks – particularly, of double strand breaks (dsbs) that are associated with cell death, mutation, aging, and transformation.1 – 4 One electron oxidation of the sugar-phosphate backbone creates an electron loss center (hole) which upon deprotonation forms a sugar radical and these are the immediate precursors of radiation-induced frank DNA-strand breaks produced via the electron-loss (oxidative) pathway.1, 4 – 13 Hole transfer from the sugar-phosphate backbone to a DNA base creates a base cation radical which prevents formation of sugar radicals via deprotonation (scheme 1).5 – 7, 11, 12, 14 – 19 Our recent work 14 has shown that, for successful formation of a sugar radical (for example, C5′•), a very rapid (< 10-12 s) deprotonation must occur from the one-electron oxidized sugar-phosphate backbone before a competitive backbone-to-base hole transfer can occur (scheme 1). This work has also shown that in both ion-beam and γ-irradiated DNA, C5′• is formed by fast deprotonation at 77 K, even though longer lived holes and electrons trapped on DNA bases are successfully scavenged at 77 K.14 Measurement of unaltered base release is considered a monitor of sugar radical formation from irradiated DNA.4 – 7 Yields of unaltered base release in DNA pellets γ-irradiated at 77 K, have suggested that considerable backbone-to-base hole transfer occurs after ionization of the sugar-phosphate DNA backbone20 – 22 with a majority of the holes from the ionized sugar-phosphate backbone transferring to the bases at 77 K. Thus, the rate and extent of hole transfer from the sugar-phosphate backbone to the base is critically controlled by fast proton transfer processes from the nascent electron deficient radical (scheme 1). 14 If the lifetime of the hole in the sugar-phosphate backbone could be increased, ESR spectroscopy could be employed to study directly the processes involved in backbone-to-base hole transfer (scheme 1).

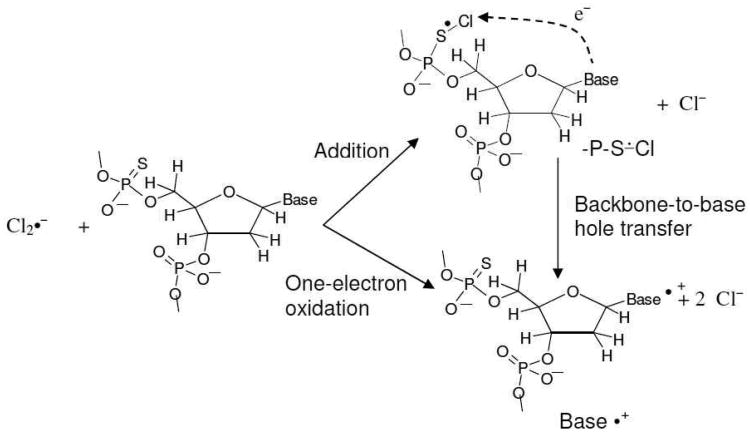

Scheme 1.

Competition between Backbone-to-base hole transfer (ht) and sugar radical formation (e.g., C5′•) via deprotonation of the one-electron oxidized sugar-phosphate.

S-oligos are being actively pursued as antisense DNA-oligomers to regulate gene expression.23 – 25 Recent work has established that the phosphorothioate modification observed in an S-oligo is a naturally occurring product of dnd genes found in bacteria and archea.26 Substitution of one of the oxygen atoms in the phosphate moiety of DNA backbone by sulphur (i.e., phosphorothioate) causes minimum perturbation of DNA base stacking and DNA conformation.27, 28 In S-oligomers, the negative charge on the phosphate moiety is retained and owing to the substitution of one of phosphate oxygen atoms by a sulphur atom it can be expected that the ionization potential as well as the one-electron oxidation potential of the phosphorothioate moiety in the S-oligomer should be lower than those for the phosphate moiety in the unmodified oligomer. As a result, the holes formed either via ionization or via one-electron oxidation of the phosphorothioate moiety in the S-oligomers could be more stabilized allowing time to investigate backbone-to-base transfer. In this work, ESR spectroscopic studies have been carried out on S-oligomers to look for one-electron oxidation of the phosphorothioate backbone by Cl2•− and possible backbone-to-base hole transfer.

Employing diisopropyl phosphorothioate as a model compound of phosphorothioate and S-oligomers of GC and AT sequences and Cl2•− as one-electron oxidant in the glassy system (7.5 M LiCl in D2O at low temperatures), evidence regarding formation of the three electron bonded adduct radical (-P-S∸Cl) is presented in this work. Upon temperature-dependent progressive annealing, this work shows that the -P-S∸Cl results in one-electron oxidation of G but not A, C, or T. Thus, the one-electron redox potential of -P-S∸Cl is bracketed between that of G and that of A. Moreover, the -P-S∸Cl radical also reacts with a second phosphorothioate to form the dimer disulfide anion radical [-P-S∸S-P-]− in model systems and in DNA oligomers. The number as well as the proximity of phosphorothioate moieties dictate the nature (unimolecular or bimolecular) formation of [-P-S∸S-P-]−. In S-oligomers having GC sequences with two phosphorothioate moieties in close proximity, ESR studies have provided the evidence of electron transfer from [-P-S∸S-P-]− to one-electron oxidized guanine. Radical identities are confirmed by density functional theory (DFT) calculations of hyperfine coupling constants of both -P-S∸Cl and [-P-S∸S-P-]− in the model compound and in S-oligomers. Experiment and theory provide for the prediction of electron affinities and one-electron redox potentials of -P-S∸Cl and [-P-S-S-P-]. Theoretical calculations have been carried out to estimate the adiabatic ionization energies of dimethyl-phosphorothioate and dimethyl-phosphate as well as the bond dissociation energy of the 2-center 3-electron σ2σ*1 bonded -P-S∸Cl and [-P-S∸S-P-]− systems.

Materials and Methods

Compounds

The phosphorothioate model compound diisopropyl phosphorothioate (DIP), and Lithium chloride (99% anhydrous, Sigma Ultra) were procured from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO). Potassium persulfate (crystal) was obtained from Mallinckrodt, Inc. (Paris, KY). Deuterium oxide (99.9 atom % D) was obtained from Aldrich Chemical Company Inc. (Milwaukee, WI).

Double stranded (ds) DNA S-oligomers such as, d[TGCGsCGCGCA]2, d[TGCGsCsGCGCA]2, d[ATTTAsAAT]2, d[ATTTAsAsAsT]2, and d[ATATAsTsAsT]2 have been obtained from SynGen, Inc. (Hayward, CA). In all these sequences, the symbol “s” denotes substitution of phosphate by phosphorothioate moiety. These S-oligomers have been lyophilized, desalted, and column-purified. The modified column purification protocol with extended wash steps have been applied by SynGen, Inc. to ensure the complete removal of reported organic contaminants such as “Benzoyl” 29 from these ds S-oligomers.

All compounds were used without any further purification.

Preparation of solutions

(a) DIP solution preparations

Following our previous works with the monomeric model compounds of DNA and RNA,5 – 7, 14, 17, 18, 30 – 43 homogeneous solutions of DIP have been prepared by dissolving ∼2 mg of DIP in 1 ml of 7.5 M LiCl in D2O (pH ca. 5) in the presence of 6 mg K2S2O8 as the electron scavenger.

(b) ds DNA S-oligomer solution preparations

As per our continuing efforts using DNA and RNA oligomers, 5 – 7, 14, 17, 18, 30 – 43 homogeneous solutions of these S-oligomers are prepared by dissolving 1.1 to 1.6 mg of a S-oligomer in 1 ml of 7.5 M LiCl/D2O with occasional vortexing. Thereafter, 8 to 10 mg K2S2O8 has been added as the electron scavenger.

We have already shown that the ds DNA 8-mer d[TGCGCGCA]2 remains double stranded in 7.5 M LiCl in D2O up to 48oC.42 The dsDNA oligomers in homogeneous aqueous (H2O) glasses (10 M LiCl) have been reported to be in the B-conformation.44 It has already been mentioned (see Introduction) that the crystal structures of unmodified and phosphorothioate-modified ds DNA-oligomers have been found to be very similar.27, 28 Thus, it can be concluded that in our system (homogeneous solutions of an S-oligomer in 7.5 M LiCl in D2O), S-oligomers are double stranded.

Employing K2S2O8 as the electron scavenger, only the formation of one-electron oxidized radicals and their reactions are studied in our system.

Preparation of glassy samples and their storage

Homogenous solutions of DIP were thoroughly bubbled with nitrogen to remove oxygen. For oxygen reaction studies, matched DIP solutions are saturated with oxygen. The homogeneous solutions of ds S-oligomers are thoroughly bubbled with nitrogen to remove oxygen.

Thereafter, as per our previous efforts, 5 – 7, 14, 17, 18, 30 – 43 these homogeneous solutions of DIP and the ds DNA S-oligomers are drawn into 4 mm Suprasil quartz tubes (Catalog no. 734-PQ-8, WILMAD Glass Co., Inc., Buena, NJ). Subsequently, these tubes containing these solutions are rapidly cooled to 77 K. This rapid cooling of these liquid solutions results into the transparent glassy solutions which are later used for the irradiation and subsequent progressive annealing experiments. All samples are stored at 77 K in teflon containers in the dark.

γ- irradiation of glassy samples and their storage

Following our works,37, 45 the glassy samples in teflon containers were placed in a 400 ml styrofoam dewar under liquid nitrogen (77 K). The styrofoam dewar was then placed into the 109 – GR 9 irradiator that contains a properly shielded 60Co gamma source so that the γ irradiation of the glassy samples were performed at 77 K to an absorbed dose of 1.4 kGy. These γ-irradiated samples are stored at 77 K in the dark in teflon containers for ESR analyses.

Annealing of the samples

As per our work with ds DNA-oligomers,42, 43 annealing ESR studies of these γ-irradiated glassy samples are carried out in the range 155 to 175 K.

Employing a variable temperature assembly (Air products) via cooled nitrogen gas in the dark which regulated the gas temperature within 4 K, annealing studies for these samples are carried out.

The annealing of the sample softens the glass thereby allowing matrix radicals, e.g., Cl2•− to migrate and react with solute (either DIP or ds S-oligomer). Formation of sulfur-centered adduct radical (-P-S∸Cl) in DIP and S-oligomers are produced by reaction with Cl2•− on annealing in the temperature range, 100-160 K (see Results). Subsequent reactions of -P-S∸Cl are followed by ESR spectroscopy upon further annealing these samples in the temperature range,155-180 K, for 15 to 20 min (see Results). After annealing, these samples were immersed in liquid nitrogen (77 K) and stored.

Electron Spin Resonance

Following γ-irradiation and annealing, these glassy samples are immersed immediately in liquid nitrogen, and an electron spin resonance (ESR) spectra are recorded at 77 K and at 40 dB (20 μW) power as well as 30 dB (0.2 mW) for the -P-S∸Cl radical which is less prone to power saturation than other DNA radicals. Fremy's salt (with g (center) = 2.0056, AN = 13.09 G) has been used for field calibration.22, 37, 45 We have recorded these ESR spectra using a Varian Century Series ESR spectrometer operating at 9.3 GHz with an E-4531 dual cavity, 9-inch magnet and with a 200 mW klystron. 22, 37, 45 Following our works,30, 37 the simulated spectra are obtained to fit the experimentally recorded spectra employing anisotropic simulations. These simulations have been carried out by WIN-EPR and SimFonia (Bruker) programs. All the ESR spectra reported in this work have been recorded at 77 K.

Calculations based on Density Functional Theory (DFT)

Becke's three parameter exchange functionals (B3)46, 47 with Lee, Yang, and Parr's correlation functional (LYP)48 and 6-31G* basis set has been designated as the B3LYP/6-31G* method. Our works 5 – 7, 14, 17, 18, 30 – 43 along with the works of others 49 – 52 have shown that the the B3LYP method with the compact basis set 6-31G* is quite appropriate to obtain reliable hyperfine coupling constant (HFCC) values for radicals that are comparable to experimentally determined HFCCs. Therefore, the B3LYP/6-31G* method has been used in this work to study the optimized geometries, spin density and charge distributions, and the HFCC values of -P-S∸Cl and [-P-S∸S-P-]− in DIP (reactions 4 and 5) in the gas phase. The geometry of the adenine dinucleoside diphosphorothioate, AsAs, has been fully optimized employing the M06-2×/6-31G** method because B3LYP is not suitable for stacked systems.53 Spin density distributions along with the HFCC values of [-P-S∸S-P-]− in AsAs are calculated at the B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory in the gas phase. The 6-31++G(d) basis set was used to calculate the reduction potentials, adiabatic electron affinity (AEA), bond dissociation energy (BDE), and the adiabatic ionization energies (see section (B)). All calculations reported in this work have been performed using Gaussian 09 suite of programs. 54 GaussView 55 and IQMOL56 programs have been used to plot the spin densities, molecular orbitals and molecular structures.

Results and Discussion

(A) Experimental

1. Diisopropyl phosphorothioate (DIP) – the model compound

Formation of -P-S∸Cl followed by formation of disulfide anion radical ([-P-S∸S-P-]−) in DIP

The ESR spectrum (black) of a γ-irradiated glassy (7.5 M LiCl/D2O) sample of DIP (2 mg/ml) is shown in Figure 1A. When this spectrum (400 G scan) is compared with the central part of the total 880 G wide multiplet Cl2•− spectrum,37, 43 it is observed that the black spectrum contains only the expected two low field resonances from Cl2•− and a sharp singlet due to SO4•−. Formation of Cl2•− results from radiation-produced holes (reaction 1), whereas, the reaction of radiation-produced electrons with S2O82– leads to the formation of SO4•− (reaction 2).2–5 Formation of additional Cl2•− occurs on the reaction of SO4•− with Cl− upon annealing to 140 K (data not shown) as per our previous work (reaction 3).5 – 7, 31, 57

Figure 1.

ESR spectra (black) of (A) γ-irradiated glassy sample of DIP (2 mg/ml in 7.5 M LiCl/D2O) in the presence of electron scavenger K2S2O8 (6 mg/ml) at pH ca. 5. (B-D) Spectra found after annealing to (B) 153 K for 15 min, (C) 160 K for 15 min, (D) 165 K for 20 min. The blue spectra in 1B and 1D are the simulated spectra of -P-S∸Cl and [-P-S∸S-P-]− respectively. See text for details of simulation. The spectra in red are of a matched sample of DIP (2 mg/ml) in which oxygen was bubbled for 30 s are superimposed on the corresponding black spectra in (A), (B), (C), and (D) for comparison (all other conditions the same as black). (E) shows the position of three Fremy's salt resonances with the central one at g = 2.0056. Each of these lines is separated from each other by 13.09 G.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Annealing of this sample at 153 K for 15 min allows for the migration of the only remaining reactant species, Cl2•–, which reacts with the solute (DIP) producing the black spectrum in Figure 1B showing formation of a chlorine atom adduct radical species (-P-S-Cl) whose three electron bonding is σ2σ*1 in nature. This spectrum has a characteristic quartet owing to a single anisotropic Cl atom with an A‖ Cl of ca. 67 G along with the central doublet due to an isotropic a-P atom coupling of ca. 23 G (see Table 2). An anisotropic simulation of this spectrum has been carried out. The simulated spectrum (blue) is an overlap of the spectra from two Cl isotopes (A‖ (35Cl (75%) of 67 G and 37Cl (25%) of 56 G) and A⊥ = 0) along with a mixed Lorentzian/Gaussian (1/1) isotropic linewidth of 10 G and g‖ = 2.0028 and g⊥ =2.0014. The simulated spectrum (blue) matches the black spectrum quite well and supports our assignment of this black spectrum to -P-S∸Cl. Formation of this σ2σ*1 bonded adduct radical -P-S∸Cl occurs as shown in the following reaction (4):

Table 2.

HFCCs values in Gauss (G) obtained by theory and experiment. B3LYP/6-31G* method has been used for the calculation.

| Molecule | Radical | Atoms | HFCC (G) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Theory | Expa | |||||

|

|

||||||

| AIso | AAniso | Total | ||||

|

| ||||||

| P | -12.31 | -0.47 | -12.78 | ca. 23 | ||

| -P-S∸Cl | 0.05 | -12.26 | ||||

| 0.42 | -11.89 | |||||

|

|

||||||

| 35Cl | 22.41 | -24.25 | -1.84 | 0 | ||

| -24.20 | -1.79 | 0 | ||||

| 48.46 | 70.87 | 67b | ||||

|

|

||||||

| DMP | P1 | -8.92 | -0.88 | -9.80 | (6.0, 9.0, | |

| -0.27 | -9.19 | 7.0) | ||||

| [-P-S∸S-P-]- | 1.15 | -7.77 | ||||

|

|

||||||

| P2 | -11.33 | -0.56 | -11.89 | (16.0, | ||

| -0.22 | -11.56 | 16.0, 17.0) | ||||

| 0.77 | -10.56 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| P1 | -0.14 | -1.87 | -2.01 | (2.0, 4.0, | ||

| -1.09 | -1.23 | 4.0) | ||||

| (AsAs)c | [-P-S∸S-P-]- | 2.96 | 2.82 | |||

|

|

||||||

| P2 | -13.47 | -0.90 | -14.37 | (14.0, | ||

| -0.25 | -13.72 | 16.0, 14.0) | ||||

| 1.15 | -12.32 | |||||

Experiment gives the magnitude but not the sign of the coupling.

The5 Cl isotope has 75% abundance.

Geometry was fully optimized using the M06-2×/6-31G** method.

|

(4) |

Upon further annealing of this sample to 160 K, the experimentally recorded spectrum (black) is shown in Figure 1C. Comparison of this spectrum in Figure 1C with that in Figure 1B shows that the line components due to -P-S∸Cl are still present while new line components assigned to the disulphide anion radical ([-P-S∸S-P-]−) (vide infra) produced via bimolecular reaction of -P-S∸Cl with an unreacted DIP molecule (reaction 5):

|

(5) |

The experimentally recorded spectrum (black) found on annealing to 165 K shown in Figure 1D is assigned to [-P-S∸S-P-].− The spectrum shows two anisotropic couplings assigned to two alpha P-atoms. A simulation of this spectrum employing two anisotropic α-P-atom couplings of (16.0, 16.0, 17.0) G and (6.0, 9.0, 7.0) G (see Table 2) along with a mixed Lorentzian/Gaussian (1/1) anisotropic linewidth (3.5, 4.5, 3.5) G and g-values (1.99939, 2.0046, 2.0270) shows a good match between the simulated (blue) and experimentally obtained (black) spectra.

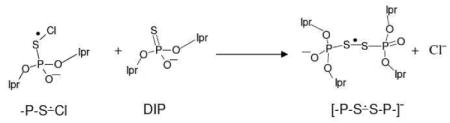

Previous ESR work 58 with methionine, methionine peptides and model compounds has shown the reaction of Cl2•− also lead to formation of Cl-S adduct radical formation (-S∸Cl). In this previous work,58 -S∸Cl adducts reacted with methionine to form disulfide cation radicals ([-S∸S-]+). In the current work, evidence of formation of the anion radical, [-P-S∸S-P-]− via reaction 5 is presented. The assignment of [-P-S∸S-P-]− is justified by theoretical calculations (see section B). While methionine resulted in the disulfide cation radical and the phosphorothioate resulted in the disulfide anion radical both are the products of one-electron oxidation and subsequent reaction with the parent compound.

The spectra (red) of a matched sample of DIP (2 mg/ml) in which oxygen was bubbled for 30 s are superimposed on the corresponding black spectra for comparison. The virtually identical nature of the black and red spectra show that oxygen had no effect on the formation of the adduct radical -P-S∸Cl or of [-P-S∸S-P-]−. Thus, contrary to various disulphide anion radical [R-S∸S-R]−,59 Figure 1 shows that [-P-S∸S-P-]− does not transfer an electron to oxygen (reaction 6) and thus, no observable decrease of ESR signal intensity of [-P-S∸S-P-]− is observed resulting from the formation of neutral and diamagnetic [-P-S-S-P-].

|

(6) |

This result is in keeping with the theoretically calculated electron affinity value of [-P-S∸S-P-]− which is found to be higher than that of molecular oxygen (see section B). Thus, one-electron reduction of dioxygen by [-P- S∸S-P-]− is not expected.

2. S-oligomers

In this part of our experimental investigations of phosphorothioates, the reaction of Cl2•− with S-oligomers have been investigated. Here we investigate two competitive reactions: (a) one-electron oxidation of DNA bases by Cl2•− and (b) electrophilic addition of Cl2•− to the S atom of the phosphorothioate moiety followed by elimination of Cl− to form -P-S∸Cl (reaction (4) and scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Competitive reactions of Cl2•− with an S-oligomer to form base cation radical via backbone-to-base hole transfer or to produce -P-S∸Cl.

Once formed, we find that -P-S∸Cl in an S-oligomer can undergo several competitive reactions (i) -P-S∸Cl can result in one-electron oxidation of the DNA base moiety (backbone-to-base hole transfer, schemes 1 and 2). Formation of [-P-S∸S-P-]− can take place via reaction of -P-S∸Cl with an unreacted phosphorothioate moiety (reaction 5) in the same strand or in the opposite strand of the same S-oligomer molecule. Intermolecular formation of [-P-S∸S-P-]− can also occur via reaction of -P-S∸Cl formed in an S-oligomer molecule with an unreacted phosphorothioate moiety of a second S-oligomer (scheme 3). The rate and extent of these reactions depend on the number and proximity of the phosphorothioate backbone moieties.

Scheme 3.

Competitive reactions of -P-S∸Cl in a ds S-oligomer.

We have investigated these reactions in S-oligomers composed of only AT (d[ATTTAsAAT]2, d[ATATAsTsAsT]2, d[ATATAsAsAsT]2) (section 2a) and S-oligomers composed of predominantly GC (d[TGCGsCGCGCA]2, d[TGCGsCsGCGCA]2) (section 2b). These results are described below.

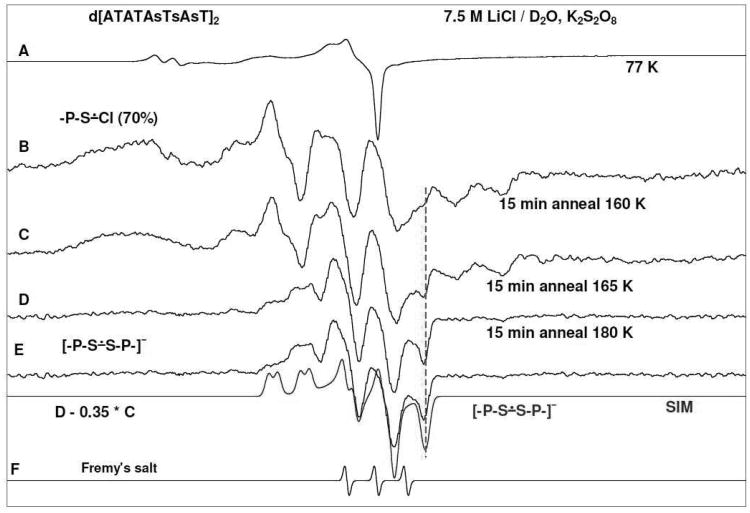

(a) AT ds S-oligos with consecutive phosphorothioates

Results obtained employing d[ATATAsTsAsT]2 are found to be similar to those from d[ATATAsAsAsT]2 (shown in supporting information Figure S1). Spectra of -P-S∸Cl and [-P-S∸S-P-]− are found to be similar in these S-oligomers though d[ATATAsAsAsT]2 has an AT mismatch. Hence, only the results of d[ATATAsTsAsT]2 are shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2.

ESR spectra (black) of (A) γ-irradiated glassy sample of d[ATATAsTsAsT]2 (1.5 mg/ml in 7.5 M LiCl/D2O) in the presence of electron scavenger K2S2O8 (9 mg/ml) at pH ca. 5. (B-D) Spectra found after annealing to (B) 160 K for 15 min, (C) 165 K for 15 min, (D) 180 K for 15 min. (E) The black spectrum obtained by subtracting 35% of spectrum (C) from spectrum (D), is the isolated spectrum of [-P-S∸S-P-]− in the ds S-oligomer. A line component from [-P-S∸S-P-]− that develops on annealing is indicated by the red dotted line. The blue spectrum in Figure (E) is the simulated spectrum of [-P-S∸S-P-]−. See text for details of simulation.

In Figure 2A, the ESR spectrum of a γ-irradiated glassy sample of d[ATATAsTsAsT]2 is presented. As found for spectrum 1A, this spectrum contains only the low field resonances from Cl2•− and a sharp component at g=2 from SO4•−. On annealing to 140K the SO4•− reacts with Cl− to form additional Cl2•− and Cl2•− is the only reacting species with the solute in this system.

Further annealing of this sample resulted in the spectra shown in 2B at 160 K, 2C at 165 K and. 2D at 170 K. Using the black spectrum in Figure 1B as benchmark spectrum for -P-S∸Cl and the black spectrum in Figure 2E for the benchmark for [-P-S∸S-P-]− in a ds S-oligomer (vide infra), analyses of these spectra show that they result from two radicals, viz. -P-S∸Cl formed early and [-P-S∸S-P-]− produced on prolonged annealing. Spectral analyses show that, on annealing, -P-S∸Cl decreased from ca. 70% at 160 K to ca. 35% at 180 K along with the concomitant increase of [-P-S∸S-P-]− from ca. 30% at 160 K to ca. 65% at 180 K. While the total signal decreased, the absolute intensity of [-P-S∸S-P-]− has increased and this is easily seen for the high field component of [-P-S∸S-P-]− which is marked with the red dotted line. These results provide evidence that -P-S∸Cl results in the formation of [-P-S∸S-P-]− (scheme 3 and reaction 5) but does not cause one-electron oxidation of either A or T.

Subtraction (ca. 35%) of spectrum of 2C from spectrum 2D results in spectrum 2E which has been assigned to [-P-S∸S-P-]− in a ds S-oligomer. This spectrum shows two α P-atom anisotropic couplings, one large and one small. A simulation of this spectrum employing two anisotropic α P-atom couplings of (14.0, 16.0, 14.0) G and (2.0, 4.0, 4.0) G (see Table 2) along with a mixed Lorentzian/Gaussian (1/1) isotropic 3.0 G linewidth and g-values (1.9965, 2.0079, 2.0303) shows a good match between the simulated (blue) and experimentally obtained (black) spectra.

(b) AT S-oligomers with one phosphorothioate

Here we investigate the extent of interstand and/or biomolecular formation of [-P-S∸S-P-]− from -P-S∸Cl for the case of a ds S-oligomer with a single phosphorothioate, d[ATTTAsAAT]2.

Figure 3A shows the ESR results found for a matched sample of d[ATTTAsAAT]2 that was γ-irradiated at 77 K and subsequently annealed to 160 K for 15 min. The spectrum in Figure 3B is obtained upon further annealing of this sample to 175 K. Spectra 3A and 3B are also found to result from two radicals, viz. -P-S∸Cl and [-P-S∸S-P-]−.

Figure 3.

ESR spectra of (A) γ-irradiated (77 K) glassy sample of d[ATTTAsAAT]2 (1.5 mg/ml in 7.5 M LiCl/D2O) in the presence of electron scavenger K2S2O8 (9 mg/ml) and found after annealing to 160 K for 15 min in the dark and (B) 175 K for 15 min.

Using the same benchmark spectra as used in the analyses of the spectra in Figure 2 (vide supra), the extent of -P-S∸Cl conversion to [-P-S∸S-P-]− (ca. 35%) found on annealing is far less than that found for the S-oligomer with adjacent phosphorothioates in Figure 2 (65%).

Comparison of results found in Figures 1, 2, and 3 leads to the following salient findings:

The rate and extent of conversion of -P-S∸Cl to [-P-S∸S-P-]− decreases considerably in ds S-oligomers than that in the monomeric model compound, DIP. In DIP, this conversion is complete at 165 K in our glassy system, while in ds S-oligomers, complete conversion of -P-S∸Cl to [-P-S∸S-P-]− is not observed even upon annealing to 180 K. The decrease in the kinetics of conversion of -P-S∸Cl to [-P-S∸S-P-]− from DIP to ds S-oligomers is attributed to steric factors associated with DNA structure which hinder dimerization.

The nature and extent of conversion of -P-S∸Cl to [-P-S∸S-P-]− are critically dependent on the number and proximity of phosphorothioate moieties in the S-oligomer. The far lower conversion of -P-S∸Cl to [-P-S∸S-P-]− in d[ATTTAsAAT]2 than that in d[ATATAsTsAsT]2 under identical conditions indicates that the formation of [-P-S∸S-P]− shows a preference for reaction between near neighbor phosphorothioates over between phosphorothiotes on opposite DNA strands in the same dsDNA molecule or inter-molecularly between separate dsDNA molecules (scheme 3).

Absence of formation of adenine and thymine cation radicals or their deprotonated forms shows that -P-S∸Cl cannot one-electron oxidize A and T and hence no backbone-to-base hole transfer (scheme 2) is possible in S-oligomers with A and T.

ESR line components resulting from sugar radical(s) has not been observed on annealing in S-oligomers.

The mismatch in the S-oligomer d[ATATAsAsAsT]2 did not affect formation of [-P-S∸S-P-]− from -P-S∸Cl.

(c) ds S-oligomers containing predominantly G and C: Backbone-to-base hole Transfer

ESR investigations were carried out employing d[TGCGsCGCGCA]2 to test for hole transfer from P-S∸Cl to G as well as [-P-S∸S-P-]−formation (schemes 2 and 3). These results are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

ESR spectra of (A) γ-irradiated (77 K) glassy sample of d[TGCGsCGCGCA]2 (1.1 mg/ml in 7.5 M LiCl/D2O) in the presence of electron scavenger K2S2O8 (8 mg/ml) and found after annealing to 160 K for 15 min in the dark, (B) 170 K for 20 min, and (C) 175 K for 20 min.

The ESR spectrum obtained using a sample of d[TGCGsCGCGCA]2 that has been γ-irradiated at 77 K and subsequently been annealed to 160 K for 15 min, is presented in Figure 4A. The ESR spectra found upon further annealing of this sample to 170 K and then to 175 K, are shown in Figures 4B and 4C, respectively.

The spectrum in Figure 4A is composed of the-P-S∸Cl radical and a singlet spectrum. ESR characteristics of the singlet (g value at the center, g⊥, the total width, and the lineshape which shows some poorly resolved hyperfine structure) matches very well with already published ESR spectrum of (G(N1-H)•:C(N3H)+) found in ds oligomers 38, 42, 43 recorded under the same conditions (at 77 K at the native pD (ca. 5) in 7.5 M LiCl/D2O). Hence, the singlet found at the center of all spectra in Figure 4 is assigned to G(N1-H)•:C(N3H)+ as the guanine moiety carries the hole (unpaired spin). The spectrum at 175 K shows that only the spectrum of G(N1-H)•:C(N3H)+ is observed in a ds S-oligomer containing GC (Figure 4C). As a result, the bimolecular formation of [-P-S∸S-P-]− is not observed in d[TGCGsCGCGCA]2 as found in d[ATTTAsAAT]2 samples (Figure 3).

The spectra in Figure 4 have been analyzed employing the black spectrum in Figure 1B as benchmark spectrum for -P-S∸Cl in a ds S-oligomer and the already published spectrum of G(N1-H)•:C(N3H)+ from our previous work 38, 42, 43 as benchmark spectrum for G(N1-H)•:C(N3H)+. These analyses confirm that the spectra in Figures 4A to 4C are due to two radicals, viz. -P-S∸Cl and G(N1-H)•:C(N3H)+.

Under the same conditions (constant gain and constant microwave power), the line components due to -P-S∸Cl progressively decrease on annealing (by a factor of ca. 4) while the singlet at the center due to G(N1-H)•:C(N3H)+ increases by a factor of 2. This is a clear evidence for thermally activated hole transfer from -P-S∸Cl to G(N1-H)•:C(N3H)+ which occurs along with the usual radical-radical recombination that reduce the overall signal intensity. Thus, this work isolates the backbone-to-base hole transfer pathway (schemes 1 and 2). Our work shows that -P-S∸Cl results in one-electron oxidation of G only and not of A, C, or T. This brackets the redox potential of -P-S∸Cl between that of G (1.29 V) and that of A (1.42 V) at pH7.43, 60

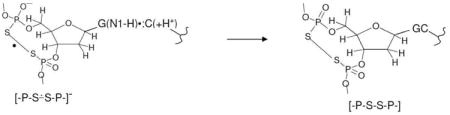

(d) Electron transfer from [-P-S∸S-P-]− to G(N1-H)•:C(N3H)+

Employing d[TGCGsCsGCGCA]2 as a model of a ds S-oligomer consisting of predominantly G and C but with two phosphorothioates, we investigate the competition of the formation of G(N1-H)•:C(N3H)+ by thermally activated hole transfer from -P-S∸Cl (see Figure 4) with the unimolecular production of [-P-S∸S-P-]− (see Figure 2).

The ESR spectrum of a γ-irradiated sample of d[TGCGsCsGCGCA]2 at 77 K after annealing to 160 K for 15 min, is shown in Figure 5A. In Figure 5B, the ESR spectrum (black) results from further annealing of this sample to 170 K.

Figure 5.

ESR spectra of (A) γ-irradiated (77 K) glassy sample of d[TGCGsCsGCGCA]2 (1.6 mg/ml in 7.5 M LiCl/D2O) in the presence of electron scavenger K2S2O8 (9 mg/ml) and found after annealing to 160 K for 15 min in the dark and (B) 170 K for 15 min. The blue spectrum in Figure 5B is the isolated spectrum of [-P-S∸S-P-]− in d[ATATAsTsAsT]2 shown in Figure 2E.

The benchmark spectra -P-S∸Cl and G(N1-H)•:C(N3H)+ used to analyze the spectra in Figure 4, have been employed in the analyses of spectra 5A and 5B.

Comparison of spectrum in Figure 4A with that in Figure 5A shows that in d[TGCGsCGCGCA]2 and in d[TGCGsCsGCGCA]2 samples, -P-S∸Cl formation dominates over the formation of one-electron oxidized G (scheme 2). From the ratio of -P-S∸Cl to G(N1-H)•:C(N3H)+, the rate of reaction of Cl2•− with G appears to be about an order of magnitude lower that of Cl2•− with the >P=S moiety in the phosphorothioate group.

The analyses show that on annealing, -P-S∸Cl decreases from 160 K to 170 K whereas G(N1-H)•:C(N3H)+ also decreased slightly. The isolated spectrum (blue) of [-P-S∸S-P-]− in d[ATATAsTsAsT]2 (already shown in Figure 2E) is shown under Figure 5B and makes up only a very small fraction of the overall signal of 5B (ca. 10 – 15%). Thus, the extent of formation of [-P-S∸S-P-]− is significantly lower than found for the AT S-oligomer in Figure 2. Moreover, the extent of formation of G(N1-H)•:C(N3H)+ in Figure 5B is far less than found in Figure 4.

We find that a significant loss of the total radical signal from -P-S∸Cl, [-P-S∸S-P-]− and G(N1-H)•:C(N3H)+ occurs on annealing from 160 K to 170 K. This was not found in previous samples and suggests a reaction such as electron transfer from [-P-S∸S-P-]− to G(N1-H)•:C(N3H)+ thereby leading to formation of neutral and diamagnetic [-P-S-S-P-] and GC (reaction 7):

|

(7) |

As found in Figures 1 to 4, no observable line components due to sugar radicals are found in the spectra shown in Figure 5.

(B) Theoretical Results

1. Model compound – dimethyl phosphorothioate (DMP)

Calculations using the B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory for dimethyl phosphorothioate (DMP) and di-isopropylphosphorothioate (DIP) show very similar results (see Supporting Information Table T1). The results for DMP are presented below for ease of description.

In order to test the extent of the decrease in ionization energy (IE) in phosphorothioate that would be expected due to the substitution of oxygen atom of the >P=O moiety in the sugar-phosphate backbone by a sulfur atom, DFT calculations have been performed employing the ωB97x/6-31++G(d) method which is known to provide accurate estimates of IE 61. The gas phase adiabatic ionization energies (AIE) of DMP as a model system of the phosphorothioate backbone and AIE of dimethyl phosphate as the model system of the phosphate backbone have been calculated. DMP has been charge neutralized by protonating the negatively charged oxygen atom and this was compared to the corresponding analogous dimethyl phosphate also protonated at its negatively charged oxygen (see supporting information Figure S2). The zero point-corrected (ZPC) AIE of phosphate backbone was calculated to be 10.02 eV while the corresponding ZPC-AIE of phosphorothioate was calculated to be 8.71 eV, respectively. The lowering of the AIE in DMP by 1.29 eV is consistent with the decrease in IE expected from the literature which shows that sulfur atom substitution for oxygen in a molecule lowers the ionization energy (IE) by about 1.2 to 1.5 eV. For example, the experimentally determined IE of formaldehyde is 10.9 eV 62 whereas that of CH2S is found to be 9.4 eV 63; the IEs of ethanol (10.5 eV) vs. ethanethiol (9.3 eV) and dimethylether (10.0 eV) vs. dimethylsuphide (8.7 eV) have been reported 64. The 1.29 eV decrease in gas phase AIE in the phosphorothioate places it in between those of the purines (G, A) and the pyrimidines (C,T).

The bonding (σ) and antibonding (σ*) molecular orbitals (MOs) for -P-S∸Cl result from electrophilic addition of Cl atom to the sulfur in DMP calculated using the B3LYP/6-31G* method are shown in Figure 6. From Figure 6, it is evident that on the formation of the σ2σ*1 bond the bonding σ2 MO(38) stabilizes strongly and located at 2.87 eV below the anti-bonding σ*1 MO(46) which is designated as singly occupied molecular orbital (SOMO).

Figure 6.

MOs for -P-S∸Cl resulting from electrophilic Cl atom addition to sulfur on dimethylphosphorothioate (DMP): (A) The doubly occupied bonding σ-MO (38). (B) The antibonding σ* singly occupied molecular orbital (SOMO) (46) calculated using the B3LYP/6-31G* optimized structure in the gas phase.

The spin density distributions of -P-S∸Cl and [-P-S∸S-P-]− for DMP calculated at the B3LYP/6-31G* level in the gas phase are shown in Figure 7. In -P-S∸Cl (Figure 7A), the unpaired spin is localized to the antibonding σp* orbitals (see Figure 6B) on the S and Cl atoms In [-P-S∸S-P-]− the spin is localized on the two S-S atoms (Figure 7B) and are very similar to those obtained for -P-S∸Cl.

Figure 7.

Spin density distributions in -P-S∸Cl and [-P-S∸S-P-]− of DMP employing the B3LYP/6-31G* method in the gas phase.

The adiabatic electron affinity (AEA), and bond dissociation energy (BDE) of -P-S∸Cl, [-P-S∸S-P-]−, and [-P-S-S-P-] for DMP, [CH3-S∸S-CH3]−, and [CH3-S-S-CH3] have been calculated employing the B3LYP/6-31++G(d) method. These values are presented in Table 1 and have been compared with those available in the literature.65 These values lead to the following conclusions:

The BDE value of [-P-S∸S-P-]− for DMP is only slightly smaller than that of [CH3-S∸S-CH3]−. Also, [-P-S-S-P-] for DMP and [CH3-S-S-CH3] have similar BDE values. As expected for addition of an antibonding electron to [-P-S-S-P-] and to [CH3-S-S-CH3] forming [-P-S∸S-P-]− and [CH3-S∸S-CH3]− the bond strength decreases almost by a factor of 2 and the S-S bond lengths of the optimized structures of anion radicals increase (2.83Å, 2.87 Å) over the diamagnetic neutral species (2.10 Å, 2.10 Å).

The gas phase AEA values of [-P-S-S-P-] and [CH3-S-S-CH3] (Table 1) are in accord with their reduction potential values (Table 3) calculated using the B3LYP/6-31++G(d) method.

Table 1.

B3LYP/6-31++G(d) calculated values of AEA, and BDE of -P-S∸Cl, [-P-S∸S-P-]−, and [-P-S-S-P-] for DMP, [CH3-S∸S-CH3]−, and [CH3-S-S-CH3] in the gas phase.

Table 3. Calculated reduction potentials of [CH3-P-S-S-P-CH3], [CH3-S-S-CH3], and O2.

| Redox couple | Eo Theory (V) a | Eo Experiment (V) |

|---|---|---|

| CH3-P-S-S-P- CH3]/[CH3-P-S∸S-P-CH3]− | -0.31 (-0.25) | - |

| [CH3-S-S-CH3]/[CH3-S∸S- CH3]− | -1.95 (-1.68) | -1.5 (Cystine) 67

-1.47 (dithiothreitol) 68 |

| O2/O2•− | -0.53 (-0.39) | -0.33 67 |

Reduction potentials calculated using the ωB97×/6-31++G(d) and B3LYP/6-31++G(d) methods incorporating the polarized continuum model (PCM) for solvation. B3LYP results are presented in parenthesis.

The experimentally obtained A‖ HFCC value for 35Cl in -P-S∸Cl from DIP is 67 G (Table 2). From this value and the value of 204 G is that expected for a full spin on Cl58 an estimate of the spin density on the Cl atom in -P-S∸Cl can be calculated as (67 G/204 G) = 0.33. The theoretically calculated spin density values of S and Cl atoms of -P-S∸Cl from DMP are obtained as 0.55 and 0.40, respectively. Thus, the experimentally found spin density value of Cl atom in -P-S∸Cl for DIP is a reasonable match with that found for DMP obtained by theory. As found by experiment and theory, the predominant spin density is on the S atom in -P-S∸Cl.

The theoretically calculated anisotropic components of HFCC values of the α P atom in -P-S∸Cl of DMP are found to be very small which predict that the α P atom in -P-S∸Cl should have a near isotropic hyperfine coupling. This is supported by experiment (see Figure 1 and Table 2). However, the theoretically calculated HFCC value of the α P atom in -P-S∸Cl is found to be ca. 10 G smaller than that of its experimentally obtained value (Table 2) and this is a common issue with DFT calculations of phosphorous couplings.66 We note here that the good agreements of the spin density value and HFCC value of the α Cl atom of -P-S∸Cl supports our assignment of the spectra in Figure 1B to -P-S∸Cl.

Employing the B3LYP/6-31G* DFT method, the spin density distribution calculated for [-P-S∸S-P-]− in DMP (Figure 7B) shows an equal distribution of spins on both the S atoms as expected. Calculations also predict roughly equal distribution of spins on both on the α P atoms (Figure 7B), and hence, the HFCC values of these α P atoms are found to have a small difference (ca. 2 G) from each other (Table 2). Theoretically calculated anisotropic components of HFCC values of both α P atoms in [-P-S∸S-P-]− are found to be very small (Table 2). Thus, calculations suggest that both α P atoms in [-P-S∸S-P-]− have near isotropic hyperfine coupling. This lack of anisotropy in the α P-atom HFCCs is also found in our experimental results (section (A)). However, the experimentally obtained HFCC values of α P atoms in [-P-S∸S-P-]− substantially differ with couplings of ca. 16 G and ca. 7.5 G. Moreover, the theoretically calculated maximum HFCC value of the α P atom (P2) in [-P-S∸S-P-]− is found to be ca. 4 to 5 G smaller than that of its experimentally obtained value (Table 2). Again this underestimation of P-atom HFCC values by DFT is expected from the literature 66.

2. Model S-oligomer (AsAs)

Because the B3LYP method was found to be unsuitable for stacked systems,53 the M06-2×/6-31G** method has been employed for finding the optimized structure (Figure 8B) of [-P-S∸S-P-]− in AsAs. Thereafter, B3LYP/6-31G* method has been employed to calculate the spin density distributions (Figure 8A) and HFCC values in [-P-S∸S-P-]− in AsAs using the M06-2×/6-31G** optimized geometries. Comparison of spin density distribution of [-P-S∸S-P-]− in DMP (Figure 7B) with that of [-P-S∸S-P-]− in AsAs (Figure 8A) shows that the S-atoms in both radicals have almost equal spin densities.

Figure 8.

(A) M06-2×/6-31G** fully optimized structure of [-P-S∸S-P]− in AsAs in the gas phase. The two α-P atoms are indicated by P1 and P2 and of (B) The spin density distribution for the structure in (A).

The B3LYP/6-31G* calculated HFCC values of [-P-S∸S-P-]− in AsAs are shown in Table 2. For DMP where the theoretically predicted HFCC values of two α-P atoms are almost equal (Figures 6B, Table 2), the theoretically calculated HFCC values of the two α-P atoms of [-P-S∸S-P-]− for AsAs are not equal – a dominant α-P atom HFCC (shown as P2 in Figure 8B) and a much smaller α-P atom HFCC (shown as P1 in Figure 8B). In Table 2, we present a comparison of the calculated and experimentally obtained HFCC values of these two α-P atoms of [-P-S∸S-P-]− for AsAs. There is a good agreement between the calculated and experimental HFCC values of [-P-S∸S-P-]− for AsAs in contrast to DMP or DIP where the theoretically calculated HFCC values of [-P-S∸S-P-]− are found to be larger than those obtained by experiments.

3. Calculated values of reduction potentials of [CH3-P-S-S-P-CH3]−, [CH3-S-S-CH3]−, and O2

Estimates of the reduction potentials of the various [-P-S-S-P-]− radicals studied in this work are of interest as these species result from the one-electron oxidation of vicinal phosphorothioates in S-oligomers. Thus, the reduction potential of [CH3-P-S-S-P-CH3]− has been calculated and compared to two other species. We have found in this work that contrary to disulphide anion radicals [R-S-S-R]-, 59 [-P-S-S-P-]− does not cause one-electron reduction of O2. Therefore, the reduction potentials of [CH3-S-S-CH3]− and O2 have also been calculated. The coB97×/6-31++G(d) method is employed for these calculations as it has provided quite accurate values of ionization potentials of the DNA bases61. We note here that the reduction potentials of these three species have been calculated employing the B3LYP/6-31++G(d) method as well for comparison. These results are presented in Table 3 below.

The experimental reduction potential for O2 is known (Table 3). Although the value of the reduction potential of [CH3-S∸S-CH3]− is not available in the literature, the corresponding value for the similar structures, cystine and glutathione disulphide anion radicals (-1.5 V) 67 as well as another disulphide anion radical from dithiothreitol, -1.47 V 68 that have been reported.

The calculated results in Table 3 clearly predict that [CH3-S∸S-CH3]− is much more reducing than O2•− while O2•− is somewhat more reducing than [CH3-P-S∸S-P-CH3]− (see Table 1 for AEA values). Hence, the calculated reduction potentials indicate that [-P-S∸S-P-]− should not undergo electron transfer to O2 as found in this work (Figure 5); however, as predicted R-S∸S-R− does transfer its excess electron to O2 as this is well-established in previous works.59 Experiment shows that the reduction potential of [-P-S∸S-P-]− must be higher than that of O2 (-0.33 V 67). The calculated reduction potential values -0.53(-0.39) V for O2 vs. -0.31(-0.25) V for [CH3-P-S∸S-P-CH3]− support this experimental observation.

Conclusions

The present work on one-electron oxidation reactions of phosphorothioate groups in S-oligmers and model compounds leads to the following salient points:

1. Formation of σ 2 σ*1 -bonded -P-S-Cl

ESR and theoretical studies presented in this work provide clear evidence of electrophilic reaction of Cl2•− with phosphorothioates (DIP and ds S-oligomers) producing the chlorine atom adduct, -P-S∸Cl with the elimination of Cl− (reaction (4) and scheme 2). The spin density distributions of S and Cl atom in -P-S∸Cl and the molecular orbital nature for σ2 bonding MO and the σ*1 antibonding SOMO is as expected for the formation of 2-center 3-electron σ2 σ*1 -bond between S and Cl atom in -P-S∸Cl.

As expected, ESR spectra of P-S-Cl in both DIP and A-T S-oligos clearly show the line components of 35Cl and 37Cl isotopes of Cl along with a single α-P atom isotropic hyperfine coupling. Experimental HFCC values of Cl and of P and spin density calculations show that the unpaired spin is mainly, ca. 67%, located on the S atom of -P-S-Cl.

2. Formation of σ2 σ*1 -bonded [-P-S-S-P-]- in DIP and in ds S-oligomers

For the small molecular species, DIP, we find complete bimolecular formation of σ2 σ*1 -bonded [-P-S-S-P-]− via reaction 5 upon annealing to 165 K. For the far larger ds S-oligomers the reaction to disulfide anion radicals is incomplete and varies in extent with the nature of the S-oligomer. In ds S-oligomers of AT with multiple phosphorothioates at close proximity, substantial but not complete unimolecular formation of only [-P-S-S-P-]− has been observed (scheme 3) via annealing 175 to 180 K. On the other hand, for ds S-oligomers of AT with one phosphorothioate on each strand a lower extent of [-P-S-S-P-]− formation likely from inter strand reaction is found. Clearly, the rate and extent of formation of [-P-S-S-P-]− is governed by the number and proximity of phosphorothioates within the DNA structure (scheme 3).

3. Backbone-to-base hole transfer process found in ds S-oligos with G

Annealing of samples of ds S-oligomers containing one or more G in the range 160 to 175 K results in the one-electron oxidation of G forming G(N1-H)•:C(N3H)+ via thermally activated hole transfer from -P-S-Cl. This is direct evidence of backbone-to-base hole transfer process. Furthermore, -P-S∸Cl induces one-electron oxidation of G only and not of A, C, or T. Thus, the redox potential of -P-S∸Cl is higher than G but is lower than those of A, C, and T. The reported redox potentials of G, A, C, and T,60 bracket the redox potential of -P-S∸Cl between the redox potentials of G and A, i.e., between 1.29 and 1.42 V. This is a relatively small range and gives a good estimate of the redox potential for -P-S∸Cl as 1.35 ± 0.07 V.

4. [-P-S∸S-P-]− does not undergo an electron transfer reaction with O2

Our ESR studies as well as the calculated values of AEA and reduction potentials in this work, clearly point out that unlike the disulphide anion radicals [R-S∸S-R]− such as cystine, glutathione disulphide anion radicals59, 68 [-P-S∸S-P-]− does not undergo an electron transfer reaction to O2. Further, ESR studies show that formation of -P-S∸Cl is not affected by the presence of oxygen. Oxygen would therefore not affect the backbone-to-base hole transfer process in ds S-oligomers.

5. Electron transfer from [-P-S∸S-P-]− to G(N1-H)•:C(N3H)+ in ds S-oligomers

Our ESR studies in ds S-oligomers containing G and with more than one phosphorothioate group present clear evidence of electron transfer from [-P-S∸S-P-]− to G(N1-H)•:C(N3H)+. Since [-P-S∸S-P-]− does not undergo electron transfer reaction with molecular oxygen, G(N1-H)•:C(N3H)+ is chemically repaired back to the GC pair even in the presence of oxygen. Thus, in these ds S-oligomers the subsequent reactions of G(N1-H)•:C(N3H)+ to form molecular products, such as 8-hydroxy-7,8-dihydroguanine and 2,6-diamino-4-hydroxy-5-formamidopyrimidine 4, 45, 69 would be prevented at the expense of formation of the neutral diamagnetic product [-P-S-S-P-] (reaction (7) and scheme 3).

The phosphorothioate disulfide link, [-P-S-S-P-], is predicted to have a stable disulphide bond of 50 kcal/mol and thus once formed in the DNA backbone would be a significant impediment to DNA replication or transcription.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (Grant RO1CA45424) for support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Supporting information contains the following: (i) comparison of the theoretically calculated HFCC values of the radicals found in DMP and in DIP (Table T1); (ii) formation of [-P-S∸S-P-]− from -P-S∸Cl in the AT mismatch in the S-oligomer d[ATATAsAsAsT]2 (Figure S1). (iii) Fully optimized structures (ωB97×/6-31++G(d)) of neutral parent molecule and cation radical of protonated dimethyl phosphate and of protonated DMP in the gas phase. This information is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.

References

- 1.Ward JF. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2000;65:377–382. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2000.65.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanaar R, Hoeijmakers JH, van Gent DC. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:483–489. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01383-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frankenberg D, Frankenberg-Schwager M, Blöcher D, Harbich R. Radiat Res. 1981;88:524–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.von Sonntag C. Free-Radical-Induced DNA Damage and Its Repair. Springer-Verlag; Germany, Heidelberg: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker D, Adhikary A, Sevilla MD. In: Charge Migration in DNA: Physics, Chemistry and Biology Perspectives. Chakraborty T, editor. Springer-Verlag; Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: 2007. pp. 139–175. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker D, Adhikary A, Sevilla MD. In: Recent Trends in Radiation Chemistry. Rao BSM, Wishart J, editors. World Scientific Publishing Co; Singapore, New Jersey, London: 2010. pp. 509–542. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker D, Adhikary A, Sevilla MD. In: Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter - Recent Advances, Applications, and Interfaces. Hatano Y, Katsumura Y, Mozumder A, editors. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group; Boca Raton, London, New York: 2010. pp. 503–541. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pogozelski WK, Tullius TD. Chem Rev. 1998;98:1089–1108. doi: 10.1021/cr960437i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenberg MM. Org Biomol Chem. 2007;5:18–30. doi: 10.1039/b612729k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dedon PC. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:206–219. doi: 10.1021/tx700283c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernhard WA. In: Radical and Radical Ion Reactivity in Nucleic Acid Chemistry. Greenberg MM, editor. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; New Jersey: 2009. pp. 41–68. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Close DM. In: Radiation-induced Molecular Phenomena in Nucleic Acids: A Comprehensive Theoretical and Experimental Analysis. Shukla MK, Leszczynski J, editors. Springer-Verlag; Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: 2008. pp. 493–529. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chatgilialoglu C. In: Radical and Radical Ion Reactivity in Nucleic Acid Chemistry. Greenberg MM, editor. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; New Jersey: 2009. pp. 99–133. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adhikary A, Becker D, Palmer BJ, Heizer AN, Sevilla MD. J Phys Chem B. 2012;116:5900–5906. doi: 10.1021/jp3023919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Close DM. Radiat Res. 1997;147:663–673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar A, Sevilla MD. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:13374–13380. doi: 10.1021/jp9058593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khanduri D, Collins S, Kumar A, Adhikary A, Sevilla MD. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:2168–2178. doi: 10.1021/jp077429y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adhikary A, Khanduri D, Kumar A, Sevilla MD. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:15844–15855. doi: 10.1021/jp808139e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar A, Sevilla MD. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:24181–24188. doi: 10.1021/jp064524i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swarts SG, Sevilla MD, Becker D, Tokar CJ, Wheeler KT. Radiat Res. 1992;129:333–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swarts SG, Becker D, Sevilla MD, Wheeler KT. Radiat Res. 1996;145:304–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Becker D, Adhikary A, Tetteh ST, Bull AW, Sevilla MD. Radiat Res. 2012;178:524–537. doi: 10.1667/RR3066.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eckstein F. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 2000;10:117–121. doi: 10.1089/oli.1.2000.10.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dias N, Stein CA. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:347–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan JHP, Lim S, Wong WSF. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2006;33:533–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2006.04403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang L, Chen S, Xu T, Taghizadeh K, Wishnok JS, Zhou X, You D, Deng Z, Dedon PC. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;11:709–710. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cruse WBT, Salisbury SA, Brown T, Cosstick R, Eckstein F, Kennard O. J Mol Biol. 1986;192:891–905. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ozaki H, McLaughlin LW. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5205–5214. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.19.5205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Black PJ, Bernhard WA. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115:8009–8013. doi: 10.1021/jp202280g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adhikary A, Kumar A, Becker D, Sevilla MD. In: Encyclopedia of Radicals in Chemistry, Biology and Materials. Chatgilialoglu C, Struder A, editors. John Wiley & Sons Ltd; Chichester, UK: 2012. pp. 1371–1396. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adhikary A, Malkhasian AYS, Collins S, Koppen J, Becker D, Sevilla MD. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5553–5564. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adhikary A, Becker D, Collins S, Koppen J, Sevilla MD. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:1501–1511. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adhikary A, Kumar A, Becker D, Sevilla MD. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:24171–24180. doi: 10.1021/jp064361y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adhikary A, Khanduri D, Kumar A, Sevilla MD. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:15844–15855. doi: 10.1021/jp808139e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Becker D, Adhikary A, Khanduri D, Sevilla MD. AIP Conference Proceedings. 2009;1197:201–208. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adhikary A, Khanduri D, Pottiboyina V, Rice CT, Sevilla MD. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:9289–9299. doi: 10.1021/jp103403p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adhikary A, Kumar A, Heizer AN, Palmer BJ, Pottiboyina V, Liang Y, Wnuk SF, Sevilla MD. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:3121–3135. doi: 10.1021/ja310650n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.(a) Adhikary A, Khanduri D, Sevilla MD. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:8614–8619. doi: 10.1021/ja9014869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Adhikary A, Sevilla MD. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115:8947–8948. doi: 10.1021/jp202664j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adhikary A, Kumar A, Khanduri D, Sevilla MD. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:10282–10292. doi: 10.1021/ja802122s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adhikary A, Kumar A, Sevilla MD. Radiat Res. 2006;165:479–484. doi: 10.1667/rr3563.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adhikary A, Collins S, Khanduri D, Sevilla MD. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:7415–7421. doi: 10.1021/jp071107c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adhikary A, Kumar A, Munafo SA, Khanduri D, Sevilla MD. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2010;12:5353–5368. doi: 10.1039/b925496j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khanduri D, Adhikary A, Sevilla MD. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:4527–4537. doi: 10.1021/ja110499a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O'Neill M, Barton JK. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:13234–13235. doi: 10.1021/ja0455897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.(a) Shukla LI, Adhikary A, Pazdro R, Becker D, Sevilla MD. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:6565–6574. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shukla LI, Adhikary A, Pazdro R, Becker D, Sevilla MD. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Becke AD. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:1372–1377. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stephens PJ, Devlin FJ, Frisch MJ, Chabalowski CF. J Phys Chem. 1994;98:11623–11627. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG. Phys Rev B. 1988;37:785–789. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hermosilla L, Calle P, García, de la Vega JM, Sieiro C. J Phys Chem A. 2005;109:1114–1124. doi: 10.1021/jp0466901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hermosilla L, Calle P, García, de la Vega JM, Sieiro C. J Phys Chem A. 2006;110:13600–13608. doi: 10.1021/jp064900z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barone V, Cimino P. Chem Phys Lett. 2008;454:139–143. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Close DM. J Phys Chem A. 2010;114:1860–1187. doi: 10.1021/jp906963f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao Y, Truhlar DG. Theor Chem Acc. 2008;120:215–241. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman MA, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Montgomery JA, Jr, Vreven T, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam JM, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas O, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ. Gaussian 09. Gaussian, Inc; Wallingford CT: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 55.GaussView. Gaussian, Inc; Pittsburgh, PA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 56.IQmol: Free open-source molecular editor and visualization package. available at http://www.iqmol.org.

- 57.Yu XY, Bao ZC, Barker JR. J Phys Chem. 2004;108:295–308. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Champagne MH, Mullins MW, Colson AO, Sevilla MD. J Phys Chem. 1991;95:6487–6493. [Google Scholar]

- 59.von Sonntag C. The Chemical Basis of Radiation Biology. Taylor & Francis; London, New York: 1987. p. 366. and the references therein. [Google Scholar]

- 60.The reduction potential at pH 7 (i.e., midpoint potential (E7)) values of the DNA components at room temperature in aqueous solutions are: E7 (dG(-H)•/dG) = 1.29 V, E7 (dA(-H)•/dA) = 1.42 V, E7 (dT•/dT) = 1.7 V, E7 (dC•/dC) =1.6 V, and E7 (dR•/dR) ≫ 1.8 V (dR = 2′-deoxyribose). The pKa of the guanine cation radical (G•+) being 3.9, the reduction potential of G•+ is reported as (E° =1.58 V) – seeSteenken S, Jovanovic SV. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:617–618. and Ref. 43.

- 61.Kumar A, Pottiboyina V, Sevilla MD. J Phys Chem B. 2012;116:9409–9416. doi: 10.1021/jp3059068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.NIST. website: http://cccbdb.nist.gov/ie2.asp?casno=50000.

- 63.Ruscic B, Berkowitz J. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:2568–2579. [Google Scholar]

- 64.NIST Chemistry Webbook. 2002 http://webbook.nist.gov/

- 65.Carles S, Lecomte F, Schermann JP, Desfrancüois C, Xu S, Nilles JM, Bowen K, Bergès J, Houée-Levin C. J Phys Chem A. 2001;105:5622–5626. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nguyen MT, Creve S, Vanquickenborne LG. J Phys Chem A. 1997;101:3174–3181. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Buettner GR. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;300:535–543. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Surdhar PS, Armstrong DA. J Phys Chem. 1987;91:6532–6537. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cadet J, Douki T, Gasparutto D, Ravanat JL, Wagner JR. In: Radical and Radical Ion Reactivity in Nucleic Acid Chemistry. Greenberg MM, editor. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; New Jersey: 2009. pp. 69–99. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.