Abstract

There is variability in home visiting program impacts on the outcomes achieved by high risk families. An understanding of how effects vary among families is important for refining service targeting and content. The current study assessed whether and how maternal attributes, including relationship security, moderate short- and long-term home visiting impacts on maternal psychosocial functioning. In this multisite RCT of home visiting in a population-based, ethnically-diverse sample of families at risk for maltreatment of their newborns (n = 643), families were randomly assigned to home visited (HV) and control groups. HV families were to receive intensive services by trained paraprofessionals from birth-3 years. Outcome data were collected when children were 1, 2, and 3 years old and 7, 8, and 9 years old. Overall, short- and long-term outcomes for HV and control mothers did not differ significantly. Demographic attributes, a general measure of overall maternal risk, and partner violence did not moderate program impact on psychosocial functioning outcomes. Maternal relationship security did moderate program impact. Mothers who scored high on relationship anxiety but not on relationship avoidance showed the greatest benefits, particularly at the long-term follow-up. Mothers scoring high for both relationship anxiety and avoidance experienced some adverse consequences of home visiting. Further research is needed to determine mediating pathways and to inform and test ways to improve the targeting of home visiting and the tailoring of home visit service models to extend positive home visiting impacts to targeted families not benefiting from current models.

Keywords: Home visiting, Attachment style, Psychosocial outcomes

There is wide dissemination of home-based family support and parenting programs nationally—driven largely by the deepening appreciation of the importance of early child development across prevention fields (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine 2000). This growth is made possible by substantial and increasing public investment in home visiting. One example is federal funding to develop infrastructure for the adoption, expansion, and enhancement of evidence-based home visiting models (Administration on Children, Youth and Families 2008). Another is the federal Maternal, Infant and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program, which was established in 2010 as part of health care reform and which invests $1.5 billion in state expansion of evidence-based early home visiting (U.S. Congress 2010).

At the same time, implementation science has deepened the field’s understanding of the challenge of engaging families in home visiting and in achieving intended benefits. Sweet and Appelbaum’s (2004) meta-analysis found evidence of statistically significant impacts of home visiting in several domains. However, that study also revealed that effect sizes were small and that program impact varied considerably across studies. Since then, the home visiting literature has continued to document diversity in home visiting program models, implementation systems, and impacts on outcomes. The growing number of program sites and the variability in impacts across programs underscore the need to understand factors for program impact.

One widely disseminated home visiting model is Healthy Families America (HFA), for which the prototype was Hawaii’s Healthy Start Program (HSP). In 1991, the U.S. Advisory Board on Child Abuse and Neglect reported that home visiting along the lines of Hawaii’s model was the most promising strategy for child abuse prevention (United States Advisory Board on Child Abuse and Neglect 1991). In 1992, Prevent Child Abuse America launched the Healthy Families Initiative to provide training and technical assistance to communities interested in adopting this model of home visiting. Today, HFA programs serve families in 430 programs in 35 states and the District of Columbia (Healthy Families America 2011).

Like HFA, many home visiting models use standardized assessment protocols to identify eligible families on the basis of demographic and psychosocial attributes associated with poor parenting, such as poverty, inexperience, poor mental health, and intimate partner violence.

There is evidence that baseline family attributes moderate home visiting impacts on outcomes of HFA and other models. For example, HFA impacts have been found to be greater for mothers with less experience and fewer psychological resources (DuMont et al. 2006). This is similar to reports of greater Nurse Family Partnership (NFP) impacts for mothers with fewer psychological resources (Olds et al. 1986). Partner violence has been shown to attenuate impacts of both the NFP model (Eckenrode et al. 2000) and the HFA model (Duggan et al. 2004, 2004, 2007).

Maternal attachment security is another potential moderator of home visiting impact. Attachment security is typically measured either via the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI; George et al. 1996) or via an adult attachment questionnaire (Mikulincer and Shaver 2007). Both approaches are thought to tap an adult’s “internal working models of attachment,” that guide perception and behavior in close relationships (Bowlby 1973). An adult’s internal working models guide his or her thinking about providing and receiving emotional support in close relationships. People with secure attachments tend to exhibit significantly less anxiety and avoidance in close relationships than people with insecure attachments. Thus, maternal attachment security might influence the quality of a mother’s relationship with her home visitor and, in turn, the program’s impact on outcomes.

At least three studies report a link between maternal attachment security and engagement in home visiting. Korfmacher et al. (1997) found that mothers with secure attachment per the AAI were more engaged in visits and accepted more forms of treatment, while those with avoidant attachment were less emotionally engaged and those with insecure-unresolved attachment had a crisis orientation to the program. Spieker et al. (2005) found greater Early Head Start participation among mothers classified as secure on the AAI and lower levels of participation among mothers classified as insecure-unresolved. McFarlane et al. (2010) found maternal attachment anxiety, as measured by the Attachment Style Questionnaire, was positively associated with visit frequency and home visitor response to poor maternal mental health. Also, maternal and home visitor attachment security interacted as factors for maternal trust in the home visitor. Mothers with high attachment anxiety gave less favorable ratings to home visitors with high versus low attachment anxiety.

These findings are concordant with attachment theory and with the results of research on mental health treatment services showing the association of adult attachment security with self-disclosure (Dozier 1990; Mikulincer and Nachshon 1991) and with service content and the relationships that clients form with therapists (Dozier et al. 2001).

A few studies have examined maternal attachment security as a moderator of home visiting outcomes. Heinicke et al. (2006), using the AAI with pregnant women, found that secure mothers in the treatment group had better parenting and child outcomes than did insecure mothers. However, another study found that maternal attachment, as measured by the AAI, did not moderate Early Head Start program impacts (Spieker et al. 2005). Robinson and Emde (2004) found that Early Head Start program impacts on observed parent–child interaction were greatest for mothers who reported both depression and an insecure attachment style. One study limitation was that it did not distinguish between subtypes of adult attachment insecurity. Duggan et al. (2009) examined the interaction of maternal depression and attachment security as a moderator of program impacts on psychosocial and parenting outcomes of HFA home visiting programs in Alaska. For several outcomes, impacts were greatest for two subsets of mothers—mothers scoring high on depressive symptoms, but only if they scored low on discomfort trusting others, and those scoring low moderate-to-high on discomfort trusting others but only if they scored low on depressive symptoms.

In the current study, we used an adult attachment style questionnaire to measure two dimensions of attachment insecurity. The first dimension pertains to the strength of one’s desire for interpersonal closeness and one’s concern about how invested others are in a close relationship. High scores on this dimension are characteristic of adults described as having “attachment anxiety” or being “preoccupied with attachment” (Mikulincer and Shaver 2007). We refer to this dimension as relationship anxiety. The second dimension pertains to one’s level of comfort with interpersonal closeness and with trusting and depending on others. High scores on this dimension are characteristic of adults described as “avoidant” or “dismissing” of attachment (Mikulincer and Shaver 2007). In this study, we refer to this dimension as relationship avoidance.

Each dimension may moderate home visiting impacts. It may be that mothers who are anxious to be close to others are particularly open to developing a close relationship with the home visitor, and thereby particularly likely to benefit from the intervention. Individuals’ relationship avoidance may also moderate program impacts. In home visiting, a mother’s distancing behavior may make it uncomfortable for her to develop trust in the home visitor and to express family needs. This, in turn, would make it hard for the home visitor to recognize and provide supportive services in response to family needs. In this way, maternal relationship avoidance may dampen home visiting effects.

The present study draws on data from a randomized trial of Hawaii’s HSP The original study was comprehensive in scope; it aimed to test overall program impacts on the full range of intended outcomes, to assess changes in impacts over time, and to identify attributes of families and home visitors that moderated service delivery and impacts on outcomes. As reported earlier, HSP program sites varied substantially in adherence to the home visiting model (Duggan et al. 2000), and both home visitor and maternal relationship security moderated service delivery (McFarlane et al. 2010). Furthermore, aside from decreased frequency of physical partner assault (Bair-Merritt et al. 2010), there was little evidence of HSP impact on maternal psychosocial functioning in the child’s first 3 years of life (Duggan et al. 2004).

The present analyses’ primary objectives were to build on our earlier reports by assessing overall HSP impacts on maternal psychosocial functioning when children were 7 to 9 years old and by testing maternal attributes, including maternal relationship security, as moderators of short- and longer-term program impacts. We focus on the same outcomes as in our earlier report of short-term impacts (Duggan et al. 2004). We describe baseline maternal attributes and maternal relationship anxiety and avoidance in the targeted families. We then report the overall short- and longer-term impacts of home visiting on maternal psychosocial outcomes. We conclude by testing maternal attributes, including relationship anxiety and avoidance, as moderators of home visiting impacts on these outcomes in both time periods.

Methods

Healthy Start Program Model

Hawaii’s HSP model has been described elsewhere (Duggan et al. 2004a, 2004b). HSP targets at-risk families of newborns through population-based screening and assessment using the Family Stress Checklist (FSC; Korfmacher 2000); families scoring ≥25 are eligible. Home visiting is voluntary and is intended to continue for 3 to 5 years, with weekly visits early on and less frequent visits as family functioning improves.

Home visitors are trained paraprofessionals working under professional supervision. They are expected to engage and establish a trusting relationship with families, to promote supportive parent–child interaction and parental empathy through parenting education, role modeling, reinforcement and referral to community resources. Within programs, home visitors have a great deal of autonomy in the selection of content for visits. Services are to be directed to the mother and, as possible, to the father and other family members. With supervisory support, home visitors are to encourage parents to seek professional help for psychosocial risks for poor parenting. Supervisors, in weekly reflective one-on-one supervision, are to use the home visit record as the context for discussing home visitor observations, actions, and plans.

Setting and Sample

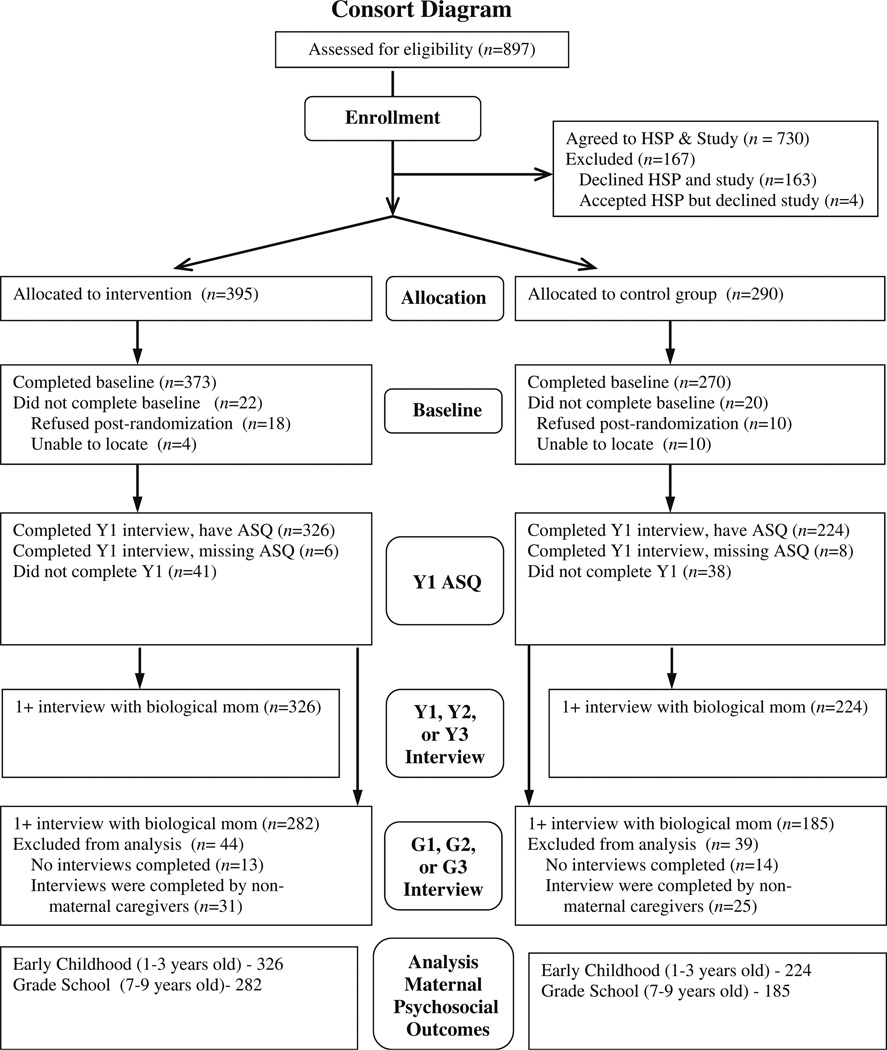

The study was carried out in six HSP program sites on Oahu, Hawaii. These six sites were operated by three community-based agencies, each with two programs. A total of 54 home visitors provided services to families. HSP staff identified at-risk families following the usual HSP protocol (Duggan et al. 2000). From November 1994 through December 1995, they identified 1,803 families as at-risk for child abuse. Of these, 1,520 families were eligible for the study because the mother understood English well enough to be interviewed and the family was not currently enrolled in the HSP. Of these, 897 families were identified on days when families could be randomly assigned to the HSP because intake at the family’s community site was open (Fig.1). Of the 897 families, 163 declined the HSP; four accepted HSP but declined the evaluation, and 730 (81 %) agreed to both the HSP and the evaluation. These 730 families were randomized to HSP and control groups, which were comparable at baseline on most demographic variables.

Fig. 1.

Consort diagram of study sample from eligibility to outcomes

At the start of the study, the Principal Investigator created study enrollment log sheets that were prepopulated with group assignment using a table of random numbers. When eligible participants were identified, HSP program staff called the fieldwork study director with the participants’ contact information. The fieldwork study director entered this information into the next available slot in the log sheet and informed the HSP staff person of the participant’s group assignment. Subjects were randomized within program site. There were three initial study groups: the HSP and main control groups (followed annually through age 3 years and again at ages 7, 8, and 9, and a testing control group (followed at age 3 as well as at ages 7, 8, and 9). By design, more families were assigned to the HSP group (n = 395) than to the main control (n =290) and testing control (n = 45) groups. The testing control group was excluded from this analysis because it did not have the same follow-up assessment schedule as the other two groups.

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, the Hawaii Department of Health and the hospitals where families were recruited.

Data Collection

Trained research staff collected baseline and follow-up data. Research staff were kept unaware of family group assignment and were independent of the HSP. They were trained in study procedures and monitored to prevent measurement bias and drift.

Research staff conducted a baseline interview with the mother at the hospital before discharge or at home within a month of delivery if a hospital interview was not possible. Overall, 684 (94 %) of those randomized were interviewed at baseline. Baseline maternal interviews measured demographics, maternal mental health, maternal substance use, and intimate partner violence. Follow-up maternal interviews measured maternal mental health, maternal substance use, and intimate partner violence.

We decided to measure maternal attachment security in the year one follow-up interview when, toward the end of sample selection, we became aware of published research showing the association of attachment security with mental health services delivery. We hypothesized that attachment security might similarly influence maternal engagement in home visiting.

Measures

Relationship Anxiety and Avoidance

The Attachment Style Questionnaire (ASQ; Feeney et al. 1994) was used to assess attachment anxiety and avoidance. The ASQ has 40 items rated on a scale of 1 (totally disagree) to 6 (totally agree). The items are distributed among five subscales: discomfort with closeness, confidence in self, need for approval, preoccupation with relationships and relationships as secondary. Strong psychometric properties have been reported, with good internal consistency (α’s for the original five subscales = 0.76 to 0.84) and short-term test-retest reliabilities (α’s = 0.67 to 0.78) (Feeney et al. 1994). To reduce respondent burden, we opted not to administer the relationships as secondary subscale.

Because of the considerable evidence of two major dimensions of adult attachment (attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance), we conducted exploratory factor analysis using a maximum likelihood algorithm and a two-factor solution to identify these factors. In the first step, all items were included; items with factor loadings ≥ 0.40 were retained. The model was rerun and again items with factor loadings ≥ 0.40 were retained. This process was repeated until all remaining items had loadings ≥ 0.40. Items with equal loadings > 0.40 on both factors were dropped. We refer to the two resulting factors as relationship anxiety and relationship avoidance.

Because the factors could be correlated, both varimax orthogonal rotation and promax (oblique) rotation were used. The two approaches generated similar factor structures; we report the promax rotation results. The relationship anxiety factor had 16 items with loadings ranging from 0.46 to 0.76 and the relationship avoidance factor had four items with loadings from 0.40 to 0.74. Reliability analyses revealed high internal consistency on both the relationship anxiety factor (α = 0.80) and the relationship avoidance factor (α = 0.88).

As reported elsewhere (McFarlane et al. 2010), maternal scores for relationship anxiety and avoidance spanned nearly the full possible range and the mean scores were above the midpoint of the possible range. We categorized mothers into four groups defined by whether their relationship anxiety and avoidance scores fell above or below the mid-point on each continuum. The four categories were: secure (both scores below the mid-point); anxious (anxiety score only above the mid-point); avoidant (avoidance score only above the mid-point); and anxious-avoidant (both scores above the mid-point).

Maternal Mental Health

The Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff 1977) and the Mental Health Index 5-Item Short Form (MHI-5; McHorney and Ware 1995) were administered to measure maternal mental health. The CES-D is a 20 item, self-report instrument widely used to measure depressive symptoms in community-based studies. Concurrent and construct validity, high internal consistency (α’s 0.85 to 0.90) and test-retest reliability (r’s = 0.51 to 0.67 in 2- to 8-week intervals) have been reported (Radloff 1977). In this sample, internal consistency (α) was 0.87. A commonly-used cutoff for high depressive symptoms is a score ≥ 16 (McDowell and Newell 1996; Radloff 1977). Because higher cut points have been recommended to reduce false positives (McDowell and Newell 1996), we used a cutoff of ≥ 24 as indicative of clinically significant depression.

The MHI5 gives an overall measure of anxiety and depressive symptoms (McHorney and Ware 1995). Items were summed and scores standardized to a scale of 0–100. Internal-consistency reliability coefficients range from 0.67 to 0.95 (Ware et al. 1993). A cutoff of <67 was used to define poor mental health (Berwick et al. 1991).

Parenting Stress

The Parenting Stress Index-Short Form (PSI-SF; Abidin 1990) is a 36-item self-report measure of parenting stress. A mother was considered positive for severe parenting stress if she scored positive for personal adjustment problems, child abuse potential or high child abuse potential as defined by Abidin (1990).

Substance Use

The CAGE (Mayfield et al. 1974) and the Addiction Severity Index (ASI; McLellan et al. 1992) have good internal consistency (median α = 0.74 across 22 samples; Shields and Caruso 2004) in addition to test-retest reliability after 7 days (0.95 in a community sample; Teitelbaum and Carey 2000). Using two or more positive responses to denote problem alcohol use, the CAGE has reported sensitivities of 43 % to 94 % and specificities of 70 % to 97 % (Fiellin et al. 2000). In this study, problem alcohol use was defined as self-reported alcohol use in the previous year and a CAGE score ≥ 2.

The ASI is a semi-structured measure of illicit substance use and resulting problems. Concurrent validity has been reported (Alterman et al. 2000), as well as strong internal consistency (α = 0.69–0.84 on the substance use domains) (Leonhard et al. 2000); and test-retest reliability (kappa= 0.83; McLellan et al. 1992). We defined illicit drug use as any such use in the past year. A mother was defined as positive for substance use problems if she was positive for problem alcohol use or illicit drug use.

Intimate Partner Violence

The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus 2007) is a widely-used instrument with strong evidence of content and construct validity (Straus 2007), good internal consistency (subscale α’s = 0.79–0.95; Straus 1990), and subscale test-retest correlations of 0.49 to 0.90 (Straus 2007). A family was considered positive for partner psychological abuse if the mother reported that either she or her partner committed acts of psychological abuse toward the other ≥ 12 times in the preceding year. A family was considered physically violent if the mother reported that either she or her partner had sustained an injury requiring medical care in the preceding year as a result of a violent act by the other. Second, a family was considered physically violent if the mother reported that either she or her partner had committed acts of physical violence toward the other on three or more occasions in the preceding year. Mothers without a partner were grouped with mothers in a non-violent relationship.

Analysis

Analysis was limited to families in the HSP and main control groups in which the biologic mother completed the interview when the child was a year old, including the ASQ, and and at least one interview when the child was 7 to 9 years old. Student’s t-test and chi-square were used to assess the baseline comparability of the treatment groups overall and within each of the four sample sub-groups defined by maternal relationship anxiety and avoidance.

All tests of overall program impact controlled for baseline covariates on which the HSP and control groups included in the analysis differed significantly (p<.05). Population average generalized estimating equations (GEE) modeling was used to assess program impact on psychosocial functioning indicators controlling for agency, year of follow-up and baseline characteristics on which the study groups varied significantly (Diggle et al. 1996). We repeated the analyses to test the moderating effects of five baseline attributes: parity (first versus higher order birth), maternal age at index child’s birth (teen versus adult), poverty status (household income at or above versus below the poverty level), maternal baseline risk (Family Stress Checklist (FSC) ≥ 25 versus <25), physical partner violence at baseline (positive versus negative, including women without a partner as negative). We tested for interactions between study group and each of these baseline attributes (p<.05). Where we found evidence of an interaction, we tested for program impact (p<.05) within each subset of families defined by the moderator. We also repeated the analyses within each of the four relationship security subgroups (secure; anxious; avoidant; and anxious-avoidant). In all analyses, two-tailed tests of significance were used.

Results

Maternal Relationship Security

Mothers varied widely on both relationship anxiety (range= 16 to 91, M=51.2, SD=11) and relationship avoidance (range=6 to 24, M =15.0, SD =3). Home visited and control mothers had similar anxiety scores (M =51.4 SD = 11.3 vs. M= 50.9 SD =11.0,p =48) and avoidance scores (M = 15.0 SD 3.2 vs. M =15.0 SD 3.3,p =.61). Overall, 44 % of mothers were classified as secure, 16 % were high on relationship anxiety but not avoidance, 22 % were high on avoidance but not anxiety, and 18 % were high on both anxiety and avoidance. Home visited and control mothers had nearly identical distributions (p=.90) across relationship classifications.

Samples in Early Childhood and in Grade School

When children were 1 to 3 years old, 94 % of biologic mothers completed at least one follow-up interview, 88 % completed at least two interviews and 78 % completed all three. Follow-up rates did not differ significantly by study group. Biological mothers with at least one follow-up interview did not differ significantly from those not followed.

When children were 7 to 9 years old, 83 % of biologic mothers completed at least one follow-up interview, 75 % completed at least two interviews and 63 % completed all three. Follow-up rates did not differ significantly by study group. Biological mothers with at least one follow-up interview were less likely to be Asian (26 % vs. 40 %, p<.01), more likely to be Caucasian (13 % vs. 6 %, p =.03), more likely to have worked at baseline (50 % vs. 40 %,p =.04), and older (23.8±5.8 vs. 22.3±5.3,P =.02) than those not followed. For both the early childhood and grade school samples, HSP and control groups were comparable at baseline on most demographic variables (Table 1). Poor maternal general mental health, substance use and physical partner violence were common in both groups. Significant treatment group differences were observed for baseline maternal general mental health and partner violence; both differences favored the HSP group. We assessed the baseline equivalence of the treatment groups within each relationship security subgroup in the early childhood and grade school samples (Tables 2 and 3, respectively). As for the full samples in each follow-up period, the treatment groups were comparable on most characteristics. Where baseline differences were found, they favored the home visited group.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of Healthy Start Program (HSP) and control groups

| Early childhood sample |

Grade school sample |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSP Group (N =326) |

Control Group (N =224) |

p | HSP Group (N =282) |

Control Group (N =185) |

p | |

| Maternal age in years (SD) | 23.6 (5.8) | 23.1 (5.6) | .30 | 23.9 (5.9) | 23.2 (5.7) | 0.22 |

| Teen mother | 30% | 33% | 0.48 | 28% | 31 % | 0.49 |

| Mother worked in year prior to delivery | 52% | 46% | 0.13 | 54% | 46% | 0.14 |

| Household income below poverty level | 64% | 64% | 0.91 | 64% | 62% | 0.57 |

| Index child is first birth | 42% | 48% | 0.17 | 42% | 47% | 0.27 |

| Mother at-risk per Family Stress Checklist | 91 % | 91 % | 0.91 | 90% | 90% | 0.90 |

| Mother’s primary ethnicity | ||||||

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 34% | 31 % | 0.52 | 34% | 29% | 0.51 |

| Asian or Filipino | 28% | 28% | 26% | 26% | ||

| Caucasian | 10% | 14% | 11 % | 16% | ||

| No primary ethnicity or unknown | 28% | 27% | 29% | 29% | ||

| Parents’ relationship | ||||||

| None | 10% | 11 % | 0.67 | 11 % | 11 % | 0.52 |

| Friends or going together | 35% | 38% | 34% | 37% | ||

| Living together | 30% | 31 % | 28% | 31 % | ||

| Married | 24% | 20% | 27% | 20% | ||

| Poor maternal general mental health | 43% | 52% | 0.03 | 42% | 52% | 0.03 |

| Maternal substance use | 19% | 23% | 0.21 | 18% | 23% | 0.24 |

| Physical partner violence | 43% | 54% | 0.01 | 43% | 53% | 0.03 |

Maternal risk, FSC Score≥25; Poor general mental health, MHI-5 score<67; Maternal substance use, either used illicit drugs in past year or drank alcohol in past year with a lifetime positive CAGE; Partner violence, three or more incidents of partner violence in past year (mothers without partners categorized as negative for partner violence)

Table 2.

Early childhood sample- baseline characteristics of healthy start program and control groups, by relationship security

| Secure |

Anxious only |

Avoidant only |

Anxious/Avoidant |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSP (n =147) |

Control (n =98) |

p | HSP (n =49) |

Control n =39) |

p | HSP (n =72) |

Control (n =48) |

p | HSP (n =58) |

Control (n =39) |

p | |

| Maternal age in years (SD) | 23.5 (5.6) | 23.1 (5.1) | 0.59 | 24.9 (6.8) | 23.9 (7.0) | 0.52 | 23.8 (5.8) | 22.3 (5.5) | 0.16 | 22.8 (5.5) | 23.4 (5.0) | 0.60 |

| Teen mother | 31 % | 30% | 0.86 | 24% | 36% | 0.24 | 26% | 38% | 0.20 | 36% | 31 % | 0.58 |

| Mother worked in year prior to delivery | 54 % | 51 % | 0.60 | 47% | 51 % | 0.69 | 46% | 35 % | 0.26 | 59% | 38% | 0.05 |

| Household income below poverty level | 59% | 62% | 0.63 | 80% | 69% | 0.26 | 64% | 65 % | 0.94 | 62% | 64% | 0.84 |

| Index child is first birth | 45% | 52% | 0.27 | 39% | 38% | 0.98 | 33 % | 44% | 0.25 | 50% | 54% | 0.71 |

| Mother at-risk per FSC | 86% | 85 % | 0.71 | 88% | 100 % | 0.03F | 97% | 94% | 0.39F | 97% | 95 % | 1.0F |

| Mother’s primary ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 36% | 33 % | 0.62 | 43 % | 23% | na1 | 24% | 32% | 0.142 | 33% | 32% | na3 |

| Asian or Filipino | 25% | 28% | 22% | 49% | 33 % | 15 % | 31 % | 26% | ||||

| Caucasian | 10% | 14% | 10% | 10% | 14% | 21 % | 9% | 10% | ||||

| No primary ethnicity or unknown | 30% | 26% | 24% | 18% | 29% | 32% | 28% | 32% | ||||

| Parents’ relationship | ||||||||||||

| None | 12% | 6% | 0.38 | 10% | 8% | na3 | 6% | 15 % | na3 | 14% | 20% | 0.71 |

| Friends or going together | 35% | 43 % | 22% | 26% | 43% | 40% | 36% | 36% | ||||

| Living together | 29% | 29% | 33 % | 31 % | 29% | 42% | 33% | 26% | ||||

| Married | 25% | 22% | 35 % | 36% | 22% | 4% | 17% | 18% | ||||

| Poor maternal general mental health | 32% | 35 % | 0.66 | 49% | 72% | 0.03 | 46% | 48% | 0.82 | 60% | 82% | 0.02 |

| Maternal substance use | 18% | 16% | 0.81 | 16% | 21 % | 0.57 | 21 % | 23 % | 0.79 | 22% | 44% | 0.03 |

| Physical partner violence | 42% | 54% | 0.07 | 33 % | 54% | 0.04 | 47% | 58% | 0.23 | 48% | 49% | 0.97 |

Fisher’s Exact Test;

At least one cell has less than the expected count, unable to report overall significance level. When tested individually, those in the HSP group were significantly less likely to be Asian or Filipino and more likely to be Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander than those in the Control group (both p<.05).

While the overall significance is >0.10, those in the HSP group were significantly more likely to be Asian or Filipino than those in the Control group (p<.05).

At least one cell has less than the expected count, unable to report the overall significance level. When tested individually, there were no group differences

Table 3.

Grade School Sample—Baseline Characteristics of Healthy Start Program and Control Groups, by Relationship Security

| Secure |

Anxious only |

Avoidant only |

Anxious/Avoidant |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSP (n = 132) |

Control (n =82) |

p | HSP (n =42) |

Control (n =31) |

p | HSP (n = 57) |

Control (n =38) |

p | HSP (n =51) |

Control (n =34) |

p | |

| Maternal age in years (SD) | 23.8 (5.6) | 23.0 (5.0) | 0.29 | 25.3 (7.1) | 24.2 (7.2) | 0.51 | 24.1 (5.8) | 22.8 (5.8) | 0.30 | 22.9 (5.7) | 23.4 (5.8) | 0.68 |

| Teen mother | 29% | 29% | 0.94 | 24% | 36% | 0.28 | 23% | 32% | 0.34 | 37% | 32% | 0.64 |

| Mother worked in year prior to delivery | 54% | 51 % | 0.64 | 50% | 45% | 0.68 | 47% | 45 % | 0.80 | 61 % | 38% | 0.04 |

| Household income below poverty level | 61 % | 60% | 0.90 | 76% | 71 % | 0.62 | 65% | 60% | 0.66 | 63 % | 59% | 0.72 |

| Index child is first birth | 43 % | 48% | 0.53 | 38% | 36% | 0.82 | 33% | 47% | 0.17 | 51 % | 56% | 0.66 |

| Mother at-risk per FSC | 86% | 83% | 0.49 | 86% | 100 % | 0.04F | 96% | 92% | 0.39F | 96% | 94% | 1.0F |

| Mother’s primary ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 37% | 35% | 0.66 | 43 % | 23% | na1 | 25% | 21 % | 0.232 | 29% | 30% | na3 |

| Asian or Filipino | 24% | 22% | 17% | 48% | 35% | 18% | 29% | 24% | ||||

| Caucasian | 10% | 16% | 12% | 10% | 16% | 24% | 10% | 12% | ||||

| No primary ethnicity or unknown | 29% | 27% | 29% | 19% | 25% | 37% | 31 % | 33% | ||||

| Parents’ relationship | ||||||||||||

| None | 12% | 6% | 28 | 12% | 10% | na3 | 5% | 16% | na3 | 14% | 21 % | 0.81 |

| Friends or going together | 34% | 43% | 19% | 26% | 42% | 37% | 37% | 35% | ||||

| Living together | 26 % | 29% | 31 % | 26% | 28% | 42 % | 33 % | 26% | ||||

| Married | 28% | 22% | 38% | 39% | 25% | 5 % | 16% | 18% | ||||

| Poor maternal general mental health | 32% | 37% | 0.47 | 50% | 68% | 0.13 | 42% | 45 % | 0.80 | 63 % | 85% | 0.02 |

| Maternal substance use | 17% | 17% | 0.98 | 14% | 23% | 0.32 | 19% | 18% | 0.92 | 24% | 41 % | 0.08 |

| Physical partner violence | 40% | 54% | 0.05 | 36% | 45% | 0.42 | 44% | 60% | 0.11 | 53 % | 50% | 0.79 |

Fisher’s Exact Test

At least one cell has less than the expected count, unable to report overall significance level. When tested individually, those in the HSP group were significantly less likely to be Asian or Filipino and more likely to be Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander than those in the Control group (both p<.05).

While the overall significance is >0.10, those in the HSP group were significantly more likely to be Asian or Filipino than those in the Control group (p<.05).

At least one cell has less than the expected count, unable to report the overall significance level. When tested individually, there were no group differences

Overall Short- and Long-term Program Impact on Prevalence of Risks for Poor Parenting

Overall, there was little evidence of short- or long-term overall program impact on maternal psychosocial functioning (Table 4). Mothers in the HSP group were significantly less likely than control mothers to score positive for poor general mental health when children were 1 to 3 years old (AOR 0.75, p =0.04). There were no significant overall impacts on any of the outcomes when children were 7 to 9 years old.

Table 4.

Program impact on outcomes when children were 1–3 years old and 7–9 years old

| Children 1–3 Years Old |

Children 7–9 Years Old |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSP | Control | AOR (95 % CI) | p | HSP | Control | AOR (95 % CI) | p | |

| Poor maternal mental health | ||||||||

| Depressive symptoms | 16% | 17% | 0.94(0.68, 1.30) | 0.72 | 9% | 11 % | 0.76 (0.52, 1.21) | 0.20 |

| Severe parenting stress | 8% | 8% | 1.01 (0.63, 1.62) | 0.97 | 8% | 10% | 0.82 (0.50, 1.52) | 0.49 |

| Poor general mental health | 31 % | 37% | 0.75 (0.58, 0.98) | 0.04 | 23% | 23 % | 0.97 (0.72, 1.39) | 0.86 |

| Maternal substance use | ||||||||

| Illicit drug use | 9% | 9% | 1.03 (0.67, 1.57) | 0.90 | 9% | 11 % | 0.81 (0.52, 1.42) | 0.41 |

| Problem alcohol use | 7% | 10% | 0.77(0.49, 1.02) | 0.25 | 8% | 11 % | 0.70(0.43, 1.13) | 0.14 |

| Partner violence | ||||||||

| Psychological abuse | 47% | 52% | 0.82(0.65, 1.03) | 0.08 | 42% | 38% | 1.15 (0.86, 1.57) | 0.36 |

| Physical abuse | 32% | 37% | 0.81 (0.62, 1.06) | 0.12 | 16% | 17% | 0.91 (0.65, 1.33) | 0.59 |

| Incident resulting in injury | 17% | 20% | 0.78(0.57, 1.07) | 0.13 | 8% | 10% | 0.86 (0.57, 1.37) | 0.50 |

The models control for agency, time of follow-up and the characteristics for which the treatment and control groups differed at baseline (maternal mental health and intimate partner violence). HSP group N: 326. Control Group N: 224;

The models control for agency, time of follow-up and the characteristics for which the treatment and control groups differed at baseline (maternal mental health and intimate partner violence). HSP group N: 282. Control Group N: 185

Moderating Effects of Baseline Family Attributes on Short-term Program Impacts

We tested the moderating effects of parity, maternal age, poverty, maternal risk status as measured by the FSC, and physical intimate partner violence on program impact when children were 1–3 years old. There was no evidence that any of these attributes moderated program impacts on any of the eight maternal psychosocial functioning outcomes.

Moderating Effect of Maternal Relationship Security on Short-term Program Impacts

Maternal relationship security moderated program impacts on mental health and substance use (Table 5). Poor mental health was common among anxious mothers in the control group; their home visited counterparts were less likely to experience severe parenting stress (AOR 0.40, p =.04) and poor general mental health (AOR 0.50, p =.03). Depressive symptoms and poor general mental health were common also among control mothers scoring high for both relationship anxiety and avoidance, but home visiting did not impact outcomes for this subgroup. Few secure and avoidant mothers scored positive on indicators of poor mental health, even in the control group, leaving little room for home visiting impact. Few mothers in any subgroup scored positive on indicators of substance use. Partner violence was common among control families in all four relationship security subgroups. For secure mothers, home visiting significantly reduced psychological abuse (AOR 0.60, p<.0l) and physical abuse (AOR 0.61,P =.03).

Table 5.

Program impact on outcomes when children were 1–3 years old, by maternal relationship security

| Securea |

Anxious onlyb |

Avoidant onlyc |

Anxious/Avoidantd |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSP | Control | AOR (95 % CI) | P | HSP | Control | 1 AOR (95 % CI) | P | HSP | Control | AOR (95 % CI) | P | HSP | Control | AOR (95 % CI) | P | |

| Poor maternal mental health | ||||||||||||||||

| Depressive symptoms | 10% | 9% | 1.17(0.62,2.18) | 0.63 | 26% | 32% | 0.76(0.38, 1.54) | 0.45 | 13% | 10% | 1.26(0.61,2.60) | 0.52 | 28% | 26% | 1.06(0.55,2.03) | 0.86 |

| Severe parenting stress | 4% | 2% | 2.62 (0.90, 7.63) | 0.08 | 12 % | 25 % | 0.40 (0.17, 0.95) | .04 | 9% | 4% | 2.09 (0.54, 8.01) | 0.28 | 11 % | 6% | 1.67(0.60,4.66) | 0.32 |

| Poor general mental health | 18% | 23% | 0.73 (0.45, 1.18) | 0.20 | 43% | 60% | 0.50 (0.26, 0.94) | 0.03 | 28% | 30% | 0.88(0.50, 1.57) | 0.68 | 54% | 53 % | 1.08 (0.59, 1.97) | 0.80 |

| Maternal substance use | ||||||||||||||||

| Illicit drug use | 7% | 8% | 0.94 (0.42, 1.78) | 0.88 | 8% | 5 % | 1.62(0.45, 5.79) | 0.46 | 12% | 10% | 1.22(0.51,2.94) | 0.66 | 9% | 11 % | 0.74 (0.31, 1.80) | 0.51 |

| Problem alcohol use | 5% | 5% | 1.06 (0.43, 2.44) | 0.90 | 7% | 8% | 0.84 (0.28, 2.56) | 0.77 | 8% | 10% | 0.86 (0.32, 2.30) | 0.76 | 8% | 12% | 0.59 (0.24, 1.46) | 0.25 |

| Partner violence | ||||||||||||||||

| Psychological abuse | 42% | 55% | 0.60 (0.42, 0.86) | <.01 | 51 % | 43 % | 1.40(0.77,2.56) | 0.27 | 53% | 60% | 0.74(0.44, 1.26) | 0.27 | 48% | 48% | 1.00 (0.55, 1.81) | 0.99 |

| Physical abuse | 24% | 34% | 0.61 (0.40, 0.94) | 0.03 | 33 % | 37% | 0.80(0.39, 1.64) | 0.55 | 39% | 40% | 0.97(0.54, 1.74) | 0.92 | 44% | 34% | 1.37(0.72,2.59) | 0.33 |

| Incident resulting in injury | 14% | 21 % | 0.62(0.35, 1.11) | 0.11 | 17% | 26% | 0.59(0.29, 1.23) | 0.16 | 25% | 25 % | 0.99 (0.52, 1.88) | 0.97 | 22% | 17% | 1.24(0.62,2.49) | 0.55 |

Models control for agency, time of follow-up and group differences on baseline intimate partner violence. HSP group N: 147. Control Group N: 98

Models control for agency, time of follow-up and group differences on baseline mental health, race, maternal risk status, and intimate partner violence. HSP group N: 49. Control Group N: 39

Models control for agency, time of follow-up, and group differences on race. HSP group N: 72. Control Group N: 48

Models control for agency, time of follow-up and group differences on baseline employment status, mental health, and substance use. HSP group N: 58. Control Group N: 39

Moderating Effects of Baseline Maternal Attributes on Long-term Program Impacts

There was little evidence that the five baseline attributes moderated program impacts on maternal psychosocial functioning outcomes. Intimate partner violence moderated home visiting impact on severe parenting stress; home visiting reduced the prevalence of this outcome only for mothers not in a violent relationship at baseline (AOR 0.50, p =.05). Overall baseline risk as measured by the FSC moderated home visiting impact on psychological abuse; home visiting reduced the prevalence of this outcome only in families where the mother did not score above 25 on the FSC (AOR 0.65,P =.02).

Moderating Effects of Maternal Relationship Security on Long-term Program Impacts

Maternal relationship security moderated program impacts on maternal mental health and partner violence (Table 6). Poor mental health was common among anxious mothers in the control group; anxious mothers in the home visited group were less likely to experience depressive symptoms (AOR 0.28, p<.0l), severe parenting stress (AOR 0.24, p =.03) and poor general mental health (AOR 0.47, p =.04). Parenting stress and poor general mental health were common also among control mothers scoring high for both anxiety and avoidance, but home visiting did not impact these outcomes for this subgroup. Few secure and avoidant mothers scored positive on indicators of poor mental health, even in the control group, leaving little room for home visiting impact. Similarly, few mothers in any subgroup scored positive on indicators of substance use. Psychological abuse was common in control mothers across all relationship security subgroups; among anxious-avoidant mothers, home visiting increased its prevalence (AOR 2.79, p<.0l). The prevalence of physical abuse was relatively low among control mothers in all but the anxious group. Among anxious-avoidant mothers, home visiting increased the odds of reported physical abuse (AOR 3.30, p<.0l). Violence resulting in injury was uncommon among control mothers except those in the anxious group; for this subgroup, the prevalence of injury was significantly lower for home visited mothers (AOR 0.27, p =.02).

Table 6.

Program impact on outcomes when children were 7–9 Years old, by maternal relationship security

| Securea |

Anxious onlyb |

Avoidant onlyc |

Anxious/Avoidantd |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSP | Control | AOR (95 % CI) | P | HSP | Control | AOR (95 % CI) | P | HSP | Contro | 1 AOR (95 % CI) | P | HSP | Control | AOR (95 % CI) | P | |

| Poor maternal mental health | ||||||||||||||||

| Depressive symptoms | 6% | 8% | 0.66(0.31, 1.41) | 0.28 | 8% | 25 % | 0.28 (0.12,0.70) | <.01 | 6% | 5 % | 1.21 (0.31,4.63) | 0.78 | 17% | 11 % | 1.69(0.74,3.83) | 0.21 |

| Severe parenting stress | 4% | 1 % | 3.09(0.65,14.68) | 0.16 | 10% | 31 % | 0.24 (0.07,0.85) | 0.03 | 10% | 5 % | 2.20(0.42,11.65) | 0.35 | 17% | 17% | 1.02(0.37,2.77) | 0.97 |

| Poor general mental health | 14% | 15% | 0.90(0.50, 1.61) | 0.72 | 26% | 44% | 0.47 (0.22,0.98) | 0.04 | 22% | 16% | 1.41 (0.65, 3.06) | 0.39 | 36% | 31 % | 1.19(0.61,2.34) | 0.61 |

| Maternal substance use | ||||||||||||||||

| Illicit drug use | 7% | 8% | 0.96 (0.40, 2.28) | 0.92 | 8% | 11 % | 0.62(0.17,2.27) | 0.47 | 10% | 12% | 0.81 (0.26, 2.52) | 0.72 | 10% | 9% | 1.14(0.36,3.62) | 0.82 |

| Problem alcohol use | 5% | 11 % | 0.46(0.21, 1.01) | 0.05 | 3% | 12% | 0.22(0.05,1.01) | 0.05 | 12% | 14% | 0.81 (0.30,2.16) | 0.67 | 13% | 8% | 1.72(0.60,4.90) | 0.31 |

| Partner violence | ||||||||||||||||

| Psychological abuse | 41 % | 37% | 1.15(0.71, 1.86) | 0.57 | 30% | 41 % | 0.60(0.26,1.36) | 0.22 | 40% | 41 % | 0.98 (0.47, 2.04) | 0.97 | 56% | 30% | 2.79 (1.36, 5.70) | <.01 |

| Physical abuse | 12% | 15% | 0.78(0.43, 1.40) | 0.40 | 14% | 27% | 0.43 (0.17, 1.08) | 0.07 | 15 % | 15 % | 0.98 (0.42, 2.28) | 0.97 | 26% | 9% | 3.30 (1.45, 7.51) | <.01 |

| Incident resulting in injury | 6% | 7% | 1.01 (0.45,2.24) | 0.98 | 7% | 22% | 0.27 (0.09,0.80) | 0.02 | 7% | 4% | 1.77 (0.43, 7.24) | 0.43 | 14% | 9% | 1.58(0.68,3.69) | 0.29 |

Models control for agency, time of follow-up and group differences on baseline intimate partner violence. HSP group N: 132. Control Group N: 82

Models control for agency, time of follow-up and group differences on race and baseline maternal risk status. HSP group N: 42. Control Group N: 31

Models control for agency, time of follow-up and group differences on race. HSP group N: 57. Control Group N: 38

Models control for agency, time of follow-up and group differences on baseline employment status, mental health, and substance use. HSP group N: 51. Control Group N: 34

Discussion

This report emanates from a randomized trial of Hawaii’s Healthy Start Program, the prototype for HFA. HFA is one of the seven models of early home visiting recently designated by HHS as evidence-based; the national Maternal, Infant and Early Childhood Home Visiting program created as part of the Affordable Care Act (US Congress 2010) requires that the majority of funds be for evidence-based home visiting models.

One important issue is whether and how effect sizes vary across subgroups of the families targeted for home visiting. If impacts vary across family subgroups, it suggests the need to refine home visiting models. One possible strategy would be to redefine eligible families, to target home visiting more narrowly to the family subgroups shown to benefit from current service models. Another strategy would be to enhance existing service models to improve effectiveness among subgroups found not to benefit from existing models. A third strategy would be to enhance existing program implementation systems to equip home visitors to work more effectively with subgroups who do not benefit from existing models. All three strategies require an understanding of how and why home visiting effect sizes vary across family subgroups.

There was little evidence of overall positive impacts on maternal psychosocial functioning. There was a significant program impact on only one outcome indicator when children were 1–3 years old, and no significant impacts when children were 7–9 years old. These findings are concordant with results of other randomized trials of HFA home visiting (Duggan et al. 2007; Landsverk et al. 2002; Mitchell-Herzfeld et al. 2005).

There was substantial variability in maternal relationship security among at-risk families enrolling in Hawaii’s HSP This heterogeneity is concordant with the results of our study of HFA program sites in Alaska (Duggan et al. 2009). It is also concordant with the variability in relationship security of participants in other home-based services, as measured by the AAI to measure maternal attachment status (Korfmacher et al. 1997) or by self-report measures of attitudes toward relationships (Robinson and Emde 2004).

The current study also found that baseline demographic attributes—maternal age, parity and household poverty—did not moderate short- or long-term HSP impacts on maternal psychosocial functioning. We found similar results when testing these variables as moderators of HFA impact on maternal depression and parenting stress in the Alaska trial. Mitchell-Herzfeld et al. (2005) also found similar results when testing for moderation of Healthy Families New York impacts on maternal depression and substance use.

Neither overall maternal risk per the FSC nor physical partner violence moderated impacts on most outcomes. In the two instances of moderation, impacts were limited to families at lower risk. These findings are concordant with the results of our Healthy Families Alaska study (Duggan et al. 2009) and Mitchell-Herzfeld et al.’s (2005) study of Healthy Families New York programs.

In contrast, the current study found that maternal relationship security did moderate short- and long-term program impacts on maternal psychosocial functioning. When children were 1 to 3 years old, HSP home visiting significantly decreased partner violence among secure mothers and parenting stress and poor general mental health in anxious mothers. When children were 7 to 9 years old, significant program impacts were found among anxious mothers for four of the eight outcomes studied. However, mothers who were both anxious and avoidant appeared to experience adverse consequences of intervention for psychological and physical abuse. However, the prevalence of these outcomes was very low for control families, and so it is possible that the apparent adverse effects of home visiting are really a reflection of greater self-disclosure among home visited mothers who were both anxious and avoidant.

Our Alaska HFA study (Duggan et al. 2009) assessed the interaction of relationship security and maternal depression as moderators of impact on maternal psychosocial functioning when children were 2 years old. Relationship anxiety was associated with stronger program impacts; relationship avoidance attenuated program impacts, especially among mothers who were depressed. Baseline depression and relationship anxiety were strongly associated. Thus, the attenuating effects of relationship avoidance in the presence of depression might be similar to the current study’s finding of attenuated effects for those scoring high on both relationship avoidance and anxiety.

The finding of greater program impact among mothers high on relationship anxiety but not avoidance is concordant with attachment theory, which suggests that relationship avoidance would make it harder to earn a mother’s trust. The results are also compatible with empirical evidence that relationship avoidance impairs maternal engagement in home visiting (Korfmacher et al. 1997) but that relationship anxiety promotes engagement (McFarlane et al. 2010).

The finding of adverse home visiting impacts for mothers scoring high on both relationship anxiety and avoidance underscores the need to consider not only the potential benefits of home visiting but also potential harm for subsets of targeted families.

Limitations

The study used a self-report measure of relationship security rather than the AAI, considered the gold standard for measuring attachment status. We did not administer all five scales of the original full instrument. Possibly as a result of this, only four items were retained in the relationship avoidance subscale. Research is needed to establish valid and reliable measures of relationship security for both research and practice.

Relationship security was assessed at 1 year instead of at baseline. Thus, it is possible that home visiting services influenced the resulting scores. Theory and empirical evidence would suggest that relationship security is a relatively stable construct. As part of the HSP randomized trial, we administered the ASQ more than once to both home visitors and mothers. As reported elsewhere, we found scores to be stable for both home visitors (Burrell et al. 2009) and mothers (McFarlane et al. 2008). Even so, it would have been preferable to test for moderation by relationship security measured at baseline.

Our measure of avoidant attachment had only four items that reflected discomfort with trust and depending on others. A more complete measure of avoidance would incorporate items reflecting a devaluing of the importance of relationships. This limitation impairs confidence in interpreting the suggested iatrogenic effects of home visiting for avoidant-anxious mothers. Further research is needed using more refined measures of avoidant attachment.

We did not measure maternal depressive symptoms at baseline. Thus, we could not assess the interaction of depressive symptoms and relationship security as moderators. Future research should assess both constructs at baseline.

We used only binary outcome measures, thus restricting study power. Future research should explore the use of continuous outcome measures.

Despite a robust sample size, the subgroup analyses required to test for moderation effects by maternal relationship security raises the risk of multiplicity and the potential for Type 1 errors. Notwithstanding this limitation, the present study reports several significant findings that are concordant with empirical evidence that relationship avoidance impairs maternal engagement in home visiting (Korfmacher et al. 1997) but that relationship anxiety promotes engagement (McFarlane et al. 2010).

Implications

This study expands existing knowledge of the effects of paraprofessional home visitation among family subgroups defined by maternal relationship security. The findings are strengthened by the consistency of the results. The findings suggest the potential value of assessing maternal relationship security in identifying and differentiating among sub-groups of at-risk families as a part of home visiting practice. The differences in maternal psychosocial functioning between program and control groups favored the HSP program for those mothers with the combination of high anxiety and low avoidance. The differences favor the control group for those mothers with a combination of high anxiety and high avoidance. Thus, it appears that the home visiting program studied was a good match for this subgroup of targeted families. However, the adverse impacts of home visiting for mothers who scored high on both relationship anxiety and avoidance suggest the need to adapt the home visiting service model for this important subgroup of at-risk families. Further research across a range of home visiting models is needed to confirm and assess the generalizability of our findings.

Families eligible for HSP and similar home visiting programs have multiple risks for poor parenting but are heterogeneous in terms of their specific constellations of needs, risks, and strengths. Maternal relationship security appears to be an important factor for how families engage in home visiting and the benefits derived. Research is needed to determine if the findings reported here are replicated in different populations and across home visiting models. If so, this knowledge could be used to design and test strategies to tailor home visiting service models to subsets of atrisk families defined by maternal relationship security. Strategies could be to augment the service model with activities to assess maternal relationship security and to provide services to build maternal reflective capacity, either directly or through referrals to community services. The substantial and increasing national investment in a range of evidence-based home visiting models underscores the importance of such work.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth McFarlane, Email: emcfarl2@jhmi.edu, Hawaii Research Offices, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 677 Ala Moana Blvd., Suite 1009, Honolulu, Hawaii 96813, USA.

Lori Burrell, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Sarah Crowne, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Fallon Cluxton-Keller, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Loretta Fuddy, Hawaii State Department of Health, Honolulu, HI, USA.

Philip J. Leaf, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA

Anne Duggan, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

References

- Abidin RR. Parenting Stress Index Short Form test manual. Charlottesville, VA: Pediatric Psychology Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. Supporting evidence-based home visitation programs to prevent child maltreatment, funding opportunity number: HHS-2 —8-ACF-ACYF-CA-130. Washington, DC: Author; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Alterman AI, McDermott PA, Cook TG, Cacciola JS, McKay JR, McLellan AT, Rutherford MJ. Generalizability of the clinical dimensions of the Addiction Severity Index to nonopioid-dependent patients. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14:287–294. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bair-Merritt MH, Jennings JM, Chen R, Burrell L, McFarlane E, Fuddy L, Duggan A. Reducing maternal intimate partner violence after the birth of a child. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 2010;164:16–23. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berwick DM, Murphy JM, Goldman PA, Ware JE, Barsky AJ, Weinstein MC. Performance of a five-item mental health screening test. Medical Care. 1991;29:169–176. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199102000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation. New York: Basic Books; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Burrell L, McFarlane E, Tandon SD, Fuddy L, Leaf P, Duggan AK. Home visitor relationship security: Association with perceptions of work, satisfaction and turnover. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2009;19:592–610. [Google Scholar]

- Diggle PJ, Liang KY, Zeger SL. The analysis of longitudinal data. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M. Attachment organization and treatment use for adults with serious psychopathological disorders. Development and Psychopathology. 1990;2:47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Lomax L, Tyrrell CL, Lee SW. The challenge of treatment for clients with dismissing states of mind. Attachment & Human Development. 2001;3:62–76. doi: 10.1080/14616730122704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan AK, Berlin LD, Cassidy J, Burrell L, Tandon SD. Examining maternal depression and attachment insecurity as moderators of the impacts of home visiting for at-risk mothers and infants. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:788–799. doi: 10.1037/a0015709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan AK, Caldera D, Rodriguez K, Burrell L, Rohde C, Crowne SS. Impact of a statewide home visiting program to prevent child abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31:829–852. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan AK, Fuddy L, Burrell L, Higman SM, McFarlane E, Windham A, Sia C. Randomized trial of a statewide home visiting program to prevent child abuse: Impact in reducing parental risk factors. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004a;28:623–643. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan AK, McFarlane E, Fuddy L, Burrell L, Higman SM, Windham A, Sia C. Randomized trial of a statewide home visiting program to prevent child abuse: Impact in preventing child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004b;28:597–622. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan AK, Windham A, McFarlane E, Fuddy L, Rohde C, Buchbinder S, Sia C. Hawaii’s Healthy Start Program of home visiting for at-risk families: Evaluation of family identification, family engagement and service delivery. Pediatrics. 2000;105:250–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuMont K, Mitchell-Herzfeld S, Greene R, Lee E, Lowenfels A, Rodriguez M. Healthy Families New York (HFNY) randomized trial: Impacts on parenting after the first two years. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2006;32:295–315. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckenrode J, Ganzel B, Henderson CR, Smith E, Olds DL, Powers J, Cole R, Sidora K. Preventing child abuse and neglect with a program of nurse home visitation: The limiting effects of domestic violence. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:1385–1391. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.11.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney JA, Noller P, Hanrahan M. Assessing adult attachment. In: Sperling MB, Berman WH, editors. Attachment in adults: Clinical and developmental perspectives. New York: Guilford; 1994. pp. 128–152. [Google Scholar]

- Fiellin DA, Reid MC, O’Connor PG. Screening for alcohol problems in primary care: A systematic review. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160:1977–1989. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.13.1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George C, Kaplan N, Main M. Adult Attachment Interview protocol. 3rd edition. University of California at Berkeley; 1996. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Healthy Families America. Frequently asked questions. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.healthyfamiliesamerica.org/about_us/faq.shtml.

- Heinicke CM, Goorsky M, Levine M, Ponce V, Ruth G, Silverman M, Sotelo C. Pre- and postnatal antecedents of a home-visiting intervention and family developmental outcome. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2006;27:91–119. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korfmacher J. The Kempe Family Stress inventory: A review. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2000;24:129–140. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korfmacher J, Adam E, Ogawa J, Egeland B. Adult attachment: Implications for the therapeutic process in a home visitation intervention. Applied Developmental Science. 1997;1:43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Landsverk J, Carrilio T, Connelly CD, Ganger W, Slymen D, Newton R, Jones C. Healthy Families San Diego clinical trial: Technical report. San Diego, CA: The Stuart Foundation, California Wellness Foundation, State of California Department of Social Services: Office of Child Abuse Prevention; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Leonhard C, Mulvey K, Gastfriend DR, Shwartz M. Addiction Severity Index: A field study of internal consistency and validity. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2000;18:129–135. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(99)00025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield D, McLeod G, Hall P. The CAGE questionnaire: Validation of a new alcoholism screening instrument. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1974;131:1121–1123. doi: 10.1176/ajp.131.10.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell I, Newell C. Depression. In: McDowell I, Newell C, editors. Measuring health: A guide to rating scales and questionnaires. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. pp. 238–286. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane E, Burrell L, Derauf DC, Fuddy L, Duggan AK. Home visiting for at-risk families of newborns: Home visitor and maternal attachment security as factors for engagement; San Francisco, CA. Poster session presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Prevention Research.2008. May, [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane E, Burrell L, Fuddy L, Tandon SD, Derauf DC, Leaf P, Duggan AK. Association of home visitors’ and mothers’ attachment style with family engagement. Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;38:541–556. [Google Scholar]

- McHorney C, Ware JE. Construction and validation of an alternate form general mental health scale for the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 36-Item Health Survey. Medical Care. 1995;33:15–28. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199501000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, Pettinati H, Argeriou M. The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Nachshon O. Attachment styles and patterns of self-disclosure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:321–332. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. New York: Guilford; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell-Herzfeld S, Izzo C, Greene R, Lee E, Lowenfels A. Evaluation of Healthy Families New York (HFNY): First year program impacts. Albany, NY: University at Albany, Center for Human Services Research; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Henderson CR, Chamberlin R, Tatelbaum R. Preventing child abuse and neglect: A randomized trial of nurse home visitation. Pediatrics. 1986;78:65–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JL, Emde RN. Mental health moderators of Early Head Start on parenting and child development: Maternal depression and relationship attitudes. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2004;4:73–97. [Google Scholar]

- Shields AL, Caruso JC. A reliability induction and reliability generalization study of the CAGE questionnaire. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2004;64:254–270. [Google Scholar]

- Spieker S, Nelson D, DeKlyen M, Staerkel F. Enhancing early attachments in the context of Early Head Start: Can programs emphasizing family support improve rates of secure infant-mother attachments in low-income families? In: Berlin LJ, Ziv Y, Amaya-Jackson L, Greenberg MT, editors. Enhancing early attachments: Theory, research, intervention and policy. New York: Guilford; 2005. pp. 250–275. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. The Conflict Tactics Scales and its critics: An evaluation and new data on validity and reliability. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, editors. Physical violence in American families: Risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families. New Brunswick: Transaction; 1990. pp. 49–73. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Conflict tactics scales. In: Jackson NA, editor. Encyclopedia of domestic violence. New York: Routledge; 2007. pp. 190–197. [Google Scholar]

- Sweet MA, Appelbaum MI. Is home visiting an effective strategy? A meta-analytic review of home visiting programs for families with young children. Child Development. 2004;75:1435–1456. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelbaum LM, Carey KB. Temporal stability of alcohol screening measure in a psychiatric setting. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14:401–404. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.4.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Advisory Board on Child Abuse and Neglect. Creating caring communities. Blueprint for an effective federal policy on child abuse and neglect. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1991. Report Number 9–1991. [Google Scholar]

- United States Congress. Patient protection and affordable care act. 2010 Mar 23; Public Law No. 111–148, Government Publications Office. Retrieved from http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgibin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=111_cong_bills&docid=f:h359oenr.txt.pdf.

- Ware JE, Snow K, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and interpretation guide. Boston: Health Institute; 1993. [Google Scholar]