Abstract

Subcellular localization is emerging as an important mechanism for mTORC1 regulation. We report that the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) signaling node, TSC1, TSC2 and Rheb, localizes to peroxisomes, where it regulates mTORC1 in response to reactive oxygen species (ROS). TSC1 and TSC2 were bound by PEX19 and PEX5, respectively, and peroxisome-localized TSC functioned as a Rheb GAP to suppress mTORC1 and induce autophagy. Naturally occurring pathogenic mutations in TSC2 decreased PEX5 binding, abrogated peroxisome localization, Rheb GAP activity, and suppression of mTORC1 by ROS. Cells lacking peroxisomes were deficient in mTORC1 repression by ROS and peroxisome-localization deficient TSC2 mutants caused polarity defects and formation of multiple axons in neurons. These data identify a role for TSC in responding to ROS at the peroxisome, and identify the peroxisome as a signaling organelle involved in regulation of mTORC1.

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is a hereditary hamartoma syndrome caused by defects in either the TSC1 or TSC2 genes1, 2. The TSC tumor suppressor is a heterodimer comprised of tuberin (TSC2), a GTPase activating protein (GAP), and its activation partner hamartin (TSC1), which localizes the TSC tumor suppressor to endomembranes and protects TSC2 from proteasomal degradation3, 4. TSC inhibits the activity of the small GTPase Rheb to repress mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling, a negative regulator of autophagy5–12. mTORC1 is regulated by a variety of cellular stimuli including amino acids, mitogens such as insulin, glucose, and energy stress13–15. In the case of amino acids, which do not signal through TSC-Rheb pathway15, mTORC1 activity is regulated by the Rag GTPases, which form the Ragulator complex that localizes mTORC1 to the late endosome or lysosome compartment of cells13–18. We recently reported that TSC functions in a signaling node downstream of ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) to repress mTORC1 in response to reactive oxygen species (ROS)19. However, identification of the specific subcellular compartment(s) in which the TSC tumor suppressor functions to regulate mTORC1 in response to ROS has heretofore remained elusive.

Peroxisomes, carry out key metabolic functions in the cell including β-oxidation of fatty acids, and are a major source of cellular ROS20, 21. Like mitochondria, peroxisomes are autonomously replicating organelles. Peroxisome biogenesis requires peroxin (PEX) proteins, which are essential for assembly of functional peroxisomes22. Specific PEX proteins, such as PEX5, function as import receptors that recognize peroxisome targeting signals (PTS) in proteins to target them to the peroxisome22.

Here we show that TSC1 and TSC2 associate with PEX proteins and are localized to peroxisomal membranes, where they regulate mTORC1 signaling in response to ROS. Activation of TSC2 and repression of mTORC1 by peroxisomal ROS induces autophagy, and in cells lacking peroxisomes, TSC2 is unable to repress mTORC1 in response to ROS. Disease-associated point mutations in the TSC2 gene result in loss of PEX5 binding, abrogate peroxisomal localization, TSC2 GAP activity for Rheb, and ROS-induced repression of mTORC1. Our data reveal a previously unknown role for the peroxisome as a signaling organelle involved in regulation of mTORC1 by TSC, and suggest that this TSC signaling node functions as a cellular sensor for ROS to regulate mTORC1 and autophagy.

RESULTS

The TSC tumor suppressor localizes to peroxisome

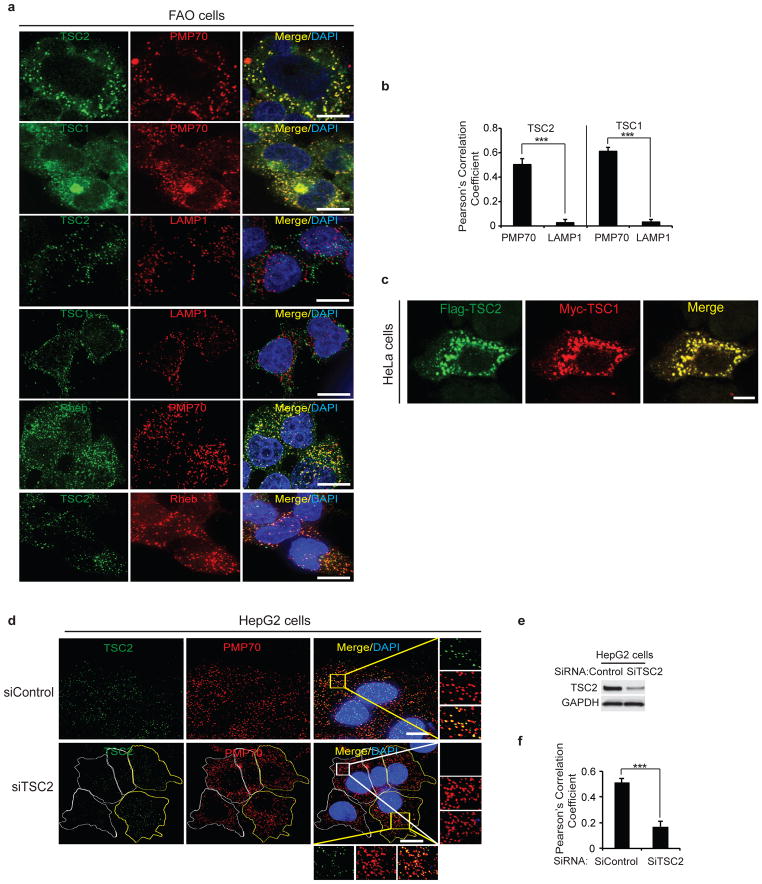

In rat liver (FAO) cells, endogenous TSC1, TSC2 and Rheb localized to discrete vesicular structures, the majority of which co-localized with the peroxisomal marker, peroxisomal membrane protein 70 (PMP70) (Fig. 1a). Quantitative analysis of these images revealed a correlation between TSC and PMP70 colocalization when compared with the lysosomal marker LAMP1 (lysosome associated membrane protein=LAMP1) (Fig. 1b). As expected, TSC1 and TSC2 also co-localized with each other in discrete vesicular structures (Fig. 1c). Endogenous TSC2 colocalization with Rheb (which also co-localized with PMP70) was also observed (Fig. 1a, bottom panels). Controls demonstrating the absence of co-localization with markers for other cellular organelles including mitochondria (mitochondrial cox 2=MTCO2) and endosomes (early endosome antigen 1=EEA1) (Supplementary Fig. S1a). Specificity for the antibody used to detect endogenous TSC2 was confirmed using siRNA knockdown of TSC2 (Fig. 1d–f), and TSC2-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (Supplementary Fig. S1b).

Figure 1.

TSC1 and TSC2 localization to peroxisomes. (a) Representative images of FAO cells immunostained with TSC2, TSC1 or Rheb (green) and PMP70 (peroxisome marker) or LAMP1 (lysosome marker) (red) antibodies. (Scale bar - 10μm). (b) Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient for TSC1 or TSC2 co-localization with PMP70 or LAMP1 calculated using Imaris software. Quantification was performed on 8–12 cells from each of the 4 independent experiment giving rise to a total of 40 cells. All error bars represent s.e.m., *** p < 0.001. (c) Representative images using HeLa cells transfected with Myc-TSC1 and Flag-TSC2 wild type (WT) and stained with anti-Flag (green) and anti-Myc (red) antobodies. (Scale bar - 10μm). (d) Representative images of HepG2 cells transfected with control (siControl) or TSC2 (siTSC2) siRNA immunostained for TSC2 (green) and PMP70 (red). Individual boundaries were shown to identify cells with TSC2 knockdown (white) versus cells that retain TSC2 (yellow). (Scale bar - 10μm). (e) Corresponding immunoblots for HepG2 cells transfected with control (siControl) or TSC2 (siTSC2) siRNA showing extent of knockdown (average over population of cells). (f) HepG2 cells from Fig. 1d were analyzed for Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient of TSC2 co-localization with PMP70 using Imaris software. Quantification was performed on 8–12 cells from each of the 4 independent experiment giving rise to a total of 40 cells. All error bars represent s.e.m., *** p < 0.001. Uncropped images of western blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. S6. Source data of statistical analysis are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

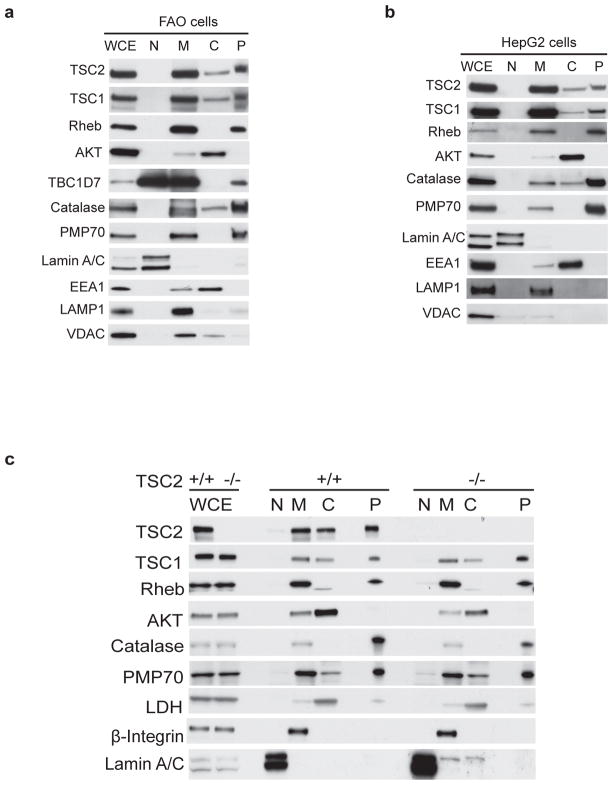

Cell fractionation confirmed the TSC signaling node (endogenous TSC1, TSC2 and Rheb) in the peroxisome fraction, which contained negligible amounts of other organelles (Fig. 2a,b). Loss of TSC2 (but not TSC1 or Rheb) from the peroxisome fraction was observed in TSC2−/− MEFs (Fig. 2c). TBC1D7 (a third subunit of the TSC1-TSC2 complex23) was also found in the peroxisome fraction (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. S1c), whereas AKT was detected in cytosolic (primarily) compartments (Fig. 2a–c and Supplementary Fig. S1c,d). Endogenous TSC2 was detected in both the membrane and cytosolic fractions (Fig. 2a,b and Supplementary Fig. S1c,d), consistent with what is known about membrane localization of active, and cytosolic sequestration of inactive, forms of this tumor suppressor, respectively24–26. Peroxisome localization of the TSC signaling node was also observed in HEK 293 (Supplementary Fig. S1c) and HeLa (Supplementary Fig. S1d), confirming the generalizability to other cell types.

Figure 2.

Cell fractionation demonstrating the TSC signaling node at the peroxisome. (a and b) Subcellular fractionation of FAO (a) or HepG2 (b) cells demonstrated the localization of TSC2, TSC1, Rheb, TBC1D7 (FAO, Fig. 2a) and AKT in various subcellular compartments. Catalase, PMP70 and Lamin A/C were used as subcellular markers for the peroxisome (P) and nuclear (N) fractions, respectively. EEA1, LAMP1 and VDAC were used as markers for endosomes, lysosomes, and mitochondria, respectively. WCE – whole cell extracts, M-membrane, C-cytosol. (c) Subcellular fractionation of TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs demonstrating the localization of TSC2, TSC1, Rheb and AKT. PMP70, catalase (peroxisome fraction - P), LDH (cytosolic fraction - C), β-integrin (membrane fraction - M) and lamin A/C (nuclear fraction - N) were used as subcellular markers. WCE – whole cell extracts. Uncropped images of western blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. S6.

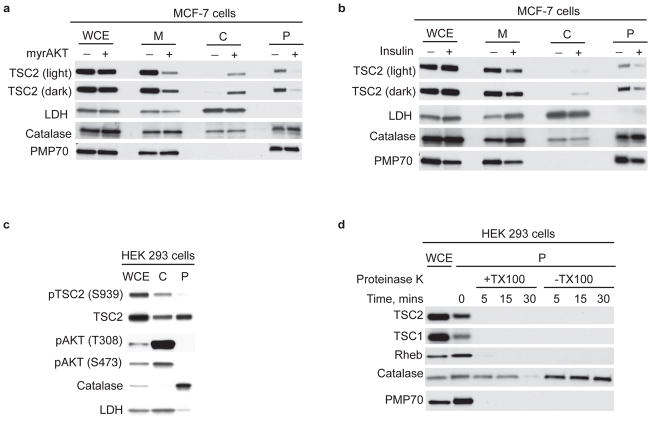

The TSC tumor suppressor is on the cytosolic surface of the peroxisome

TSC2 tumor suppressor activity occurs via membrane dissociation and cytosolic binding of this tumor suppressor by 14-3-3 proteins, sequestering it away from its activation partner TSC1 and its GAP target Rheb24. In MCF-7 cells expressing constitutively active myristoylated AKT (myr-AKT), AKT phosphorylation inactivates TSC2, with loss of TSC2 from the membrane and peroxisomal fractions and increased TSC2 in the cytosol (Fig. 3a). As predicted, TSC2 was released from peroxisome and membrane compartments into the cytosol with mitogenic stimulation by insulin (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, TSC2 phosphorylated by AKT at S939 was abundant in the cytosolic, but absent or barely detectable in the peroxisomal fraction of cells (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3.

Active TSC signaling node resident at peroxisome membrane. (a) Western analysis of whole cell extracts (WCE), membrane (M), cytosolic (C) and peroxisome (P) fractions from parental and MCF-7 cells stably expressing constitutively active myristoylated AKT (myr-AKT) immunoblotted for TSC2, LDH, catalase and PMP70. Light and dark represent short and long autoradiographic exposures, respectively. (b) Western analysis of whole cell extracts (WCE), membrane (M), cytosolic (C) and peroxisome (P) fractions from MCF-7 cells stimulated with insulin (200 nM) for 30 min after 1h of serum starvation and immunoblotted for TSC2, LDH, catalase and PMP70. Light and dark represent short and long autoradiographic exposures, respectively. (c) Representative western analysis of HEK 293 whole cell extracts (WCE), cytosolic (C), and peroxisome (P) fractions, immunoblotted for phospho-TSC2 (S939) (inactive), TSC2, and phospho-AKT (S473 and T308) (activated). LDH and catalase were used as markers for the cytosolic (C) and peroxisome (P) fractions, respectively. (d) Proteinase K protection assays performed in the presence or absence of Triton X-100 to disrupt peroxisomess on equal masses of peroxisome (P) fractions (HEK 293 cells) collected at the indicated time points. The lysates were immunoblotted for TSC2, TSC1, Rheb, catalase and PMP70. WCE –whole cell extract. Uncropped images of western blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. S6.

Correlative data that TSC2 resided at the peroxisomal membrane were supported with direct evidence from a protease protection assay, where peroxisomes were proteinase K treated in the absence or presence of membrane disrupting detergent (Triton X-100). The peroxisomal membrane protein PMP70 and TSC1, TSC2 and Rheb were degraded in both the absence and presence of detergent, indicating that they were membrane-associated (Fig. 3d), while catalase, a matrix protein control was resistant to proteinase K, confirming the TSC signaling node resides in peroxisomal membranes (Fig. 3d).

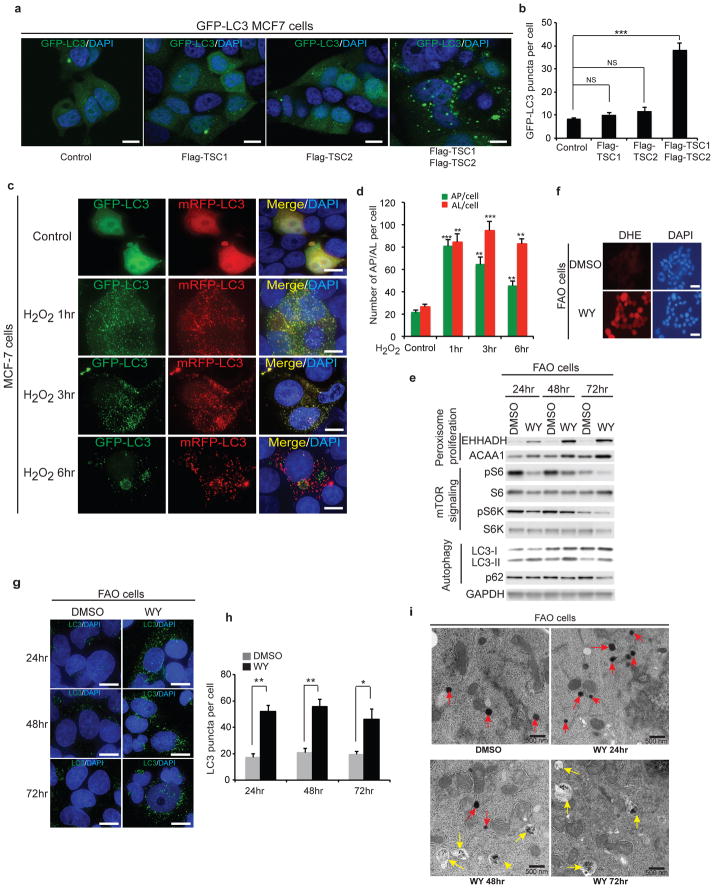

The TSC signaling node functions at the peroxisome to induce autophagy in response to ROS

As a major site of ROS generation, we hypothesized TSC at the peroxisome might induce autophagy, which is regulated by both mTORC16–8, 11 and ROS27, 28. Consistent with this hypothesis, overexpression of both Flag-TSC1 and TSC2 increased autophagosome formation relative to overexpression of either Flag-TSC1 or Flag-TSC2 alone (Fig. 4a,b). In these cells, exogenous ROS (H2O2), induced rapid (<1 hr) suppression of mTORC1, decreased p62 by 24 hrs, and increased ratio of LC3 II/Actin (Supplementary Fig. S2a,b). The decrease in p62 was significantly inhibited by Bafliomycin A1 (Baf A1), as was the increase in LC3 II (Supplementary Fig. S2c,d). Similarly, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S2e, decreased p62 in response to H2O2 occurred only in autophagy-proficient (Atg5+/+ MEFs) but not in autophagy-deficient cells (i.e. Atg5−/− MEFs29). Finally, increased autophagic flux in response to H2O2 was also demonstrated by accelerated degradation of GFP-LC3 relative to RFP-LC39, 10, which is less stable in the acidic pH of the autolysosomes (Fig. 4c,d), confirming the ability of TSC to response to ROS to regulate autophagy.

Figure 4.

The TSC signaling node at the peroxisome induces autophagy in response to ROS. (a) Representative merged images using GFP-LC3 MCF-7 cells expressing Flag-TSC1, Flag TSC2 or both Flag-TSC1 and Flag-TSC2 showing GFP-LC3 (green) puncta. (Scale bar - 10μm). (b) Quantification of GFP-LC3 puncta was performed and the results are represented as the average puncta fluorescence per cell (±s.e.m., n = 3 independent experiments) from 100 cells per experiment as shown in Fig. 4a. *** p < 0.001, NS, not significant. (c) Representative immunocytochemistry images using MCF-7 cells transfected with an mRFP-GFP-LC3 construct. Cells treated with 0.4 mM H2O2 were analyzed at 0hr (Control), 1hr, 3hr and 6hr. (Scale bar - 10μm). (d) Quantification of autophagosomes (AP, GFP-LC3) and autolysosomes (AL, RFP-LC3) per cell in different conditions as shown in Fig. 4c. The results are represented as the average puncta fluorescence per cell (±s.e.m., n = 3 independent experiments) from 100 cells per experiment. ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. (e) Western analysis of FAO cells treated with 50 μM WY-14643 (WY) or vehicle (DMSO) for PPAR-alpha-inducible proteins (EHHADH and ACAA1), mTORC1 signaling proteins [(pS6 (S235/236), S6, pS6K (T389) and S6K)] and autophagy markers (LC3 and p62). (f) Representative images of FAO cells treated with vehicle (DMSO) or 50 μM WY-14643 (WY) for 1hr, with superoxide production detected using dihydroethidium (DHE). (Scale bar - 30μm). (g) Representative images of LC3 puncta (green) in FAO cells following treatment of 50 μM WY-14643 (WY) or vehicle (DMSO) for indicated time period. (Scale bar - 10μm). (h) Quantification of LC3 puncta per cell in response to WY-14643 (WY) or vehicle (DMSO). The results are represented as the average LC3 puncta fluorescence per cell (±s.e.m., n = 3 independent experiments) from 100 cells per experiment as shown in Fig. 4a. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01. (i) Transmission electron microscopy of FAO cells treated with vehicle (DMSO) or 50 μM WY-14643 (WY) for 24, 48 and 72 hr. Peroxisomes and autophagosomes are indicated with red and yellow arrows, respectively. (Scale bar - 500nm). Uncropped images of western blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. S6. Source data of statistical analysis are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Drugs such as fibrates (e.g., Wy-14643), activate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPAR-alpha), to induce peroxisome proliferation in rodent liver cells30, 31, and increase levels of peroxisomal ROS20. FAO cells were treated with Wy-14643, which induced the expected increase in PPAR-alpha-inducible proteins peroxisomal bifunctional enzyme (EHHADH) and peroxisomal thiolase (ACAA1) (Fig. 4e), and increased superoxide radical production shown by dihydroethidium (DHE) staining (Fig. 4f). Fibrate-induced ROS suppressed mTORC1 (Fig. 4e), to induce autophagy, as confirmed by increased LC3 puncta and electron microscopy (Fig. 4g–i).

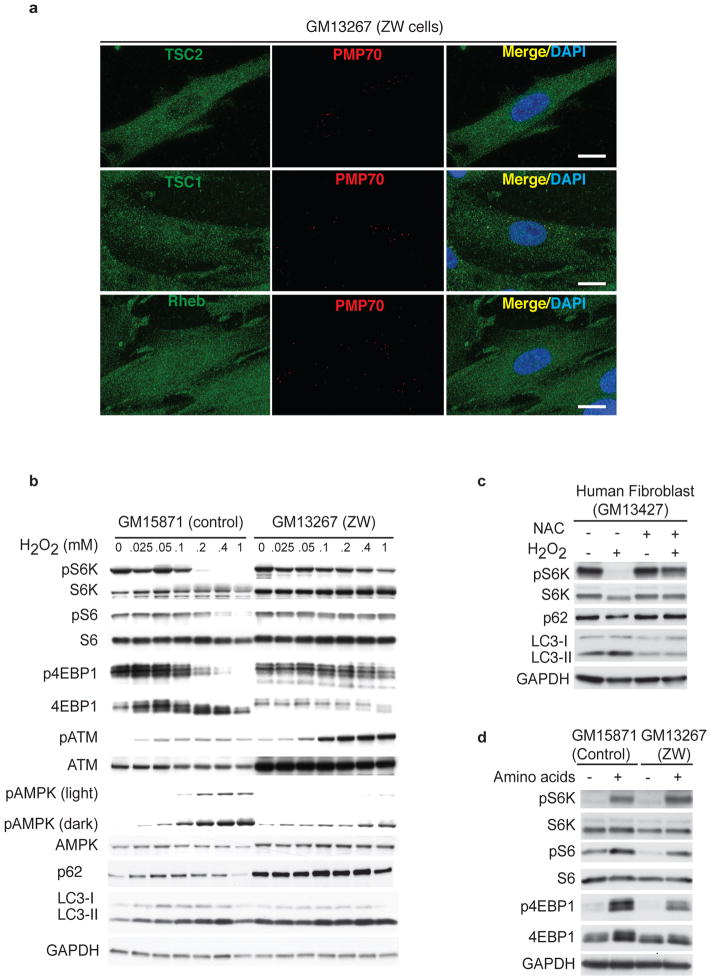

Peroxisome biogenesis disorders (PBDs) are caused by genetic defects in key proteins that participate in this process21, 32, with Zellweger syndrome being the most severe32. PBD-associated disease mutations result in an absence of functional peroxisomes. Co-localization with PMP70 for TSC2 and Rheb was lost in peroxisome-deficient human Zellweger cells (Fig. 5a). These cells are deficient in PEX5-mediated protein import but can still assemble peroxisomal membrane proteins, accounting for the occasional PMP-positive puncta, which interestingly also show colocalization with TSC1 (Fig. 5a). Peroxisome-deficient Zellweger (untransformed GM13267) cells were deficient in mTORC1 repression in response to H2O2 relative to control peroxisome-proficient (untransformed GM15871) cells (Fig. 5b). H2O2 activated ATM, AMPK and TSC2 to repress mTORC1 and induce autophagy in control fibroblasts, whereas Zellweger fibroblasts lacking peroxisomes were resistant to mTORC1 repression by H2O2 (Fig. 5b). These data were confirmed in two other control (GM13427) and Zellweger (GM13269) cell cultures (Supplementary Fig. S3a). As predicted19, in peroxisome-proficient cells, repression of mTORC1 by H2O2 was rescued with N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) (Fig. 5c), and decreased p62 was inhibited by Baf A1 (Supplementary Fig. S3b,c).

Figure 5.

TSC’s ability to suppress mTORC1 is abrogated in peroxisome-deficient Zellweger cells. (a) Representative images of Zellweger cells (GM13267) showing endogenous TSC2, TSC1 and Rheb (green) co-localization with PMP70 (red). (Scale bar - 15μm). (b) Western analysis of human fibroblasts obtained from Zellweger (GM13267) or corresponding control patient with [Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (GM15871)] treated with indicated doses of H2O2 for 1hr. mTORC1 signaling was assessed by western analysis for pS6K (T389), S6K, pS6 (S235/236), S6, p4EBP1 (T37/46), 4EBP1, pATM (S1981), ATM, pAMPK (T172), AMPK, p62 and LC3. (c) Western analysis of human fibroblast (GM13427) cells pre-incubated with 3 mM NAC (ROS scavenger) for 1hr before treated with 0.4 mM H2O2 for 1hr using anti-pS6K (T389), S6K, p62 and LC3 antibodies. (d) Representative western analysis using cell extracts from human fibroblasts obtained from a Zellweger patient (GM13267) or control fibroblasts (GM15871) treated with amino acid free media for 60 min, and stimulated with mixture of amino acid for 10 min. mTOR signaling was monitored using anti-pS6K (T389), S6K, pS6 (S235/236), S6, p4EBP1(T37/46), and 4EBP1 antibodies. Uncropped images of western blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. S6.

In contrast to ROS repression of mTORC1, which is TSC2-dependent, activation of mTORC1 by amino acids does not signal through TSC-Rheb13, 15. This predicts that Zellweger cells would still activate mTORC1 in response to stimulation with amino acids. As shown in Fig. 5d, mTORC1 signaling was activated by amino acids to an equivalent degree in both peroxisome-deficient Zellweger fibroblasts (GM13267) and control peroxisome-proficient fibroblasts (GM15871), which was confirmed in two other control (GM13427) and Zellweger (GM13269) cell (Supplementary Fig. S3d).

TSC1 and TSC2 bind peroxins PEX19 and PEX5

PEX proteins mediate localization of peroxisomal proteins and enzymes. We observed by co-immunoprecipitation of both endogenous and Flag-tagged proteins that TSC2 was bound by PEX5 (Fig. 6a,d). PEX5 is known to import proteins into the peroxisomal matrix22, whereas TSC2 localizes to endomembranes (our data and reference33), therefore additional experiments were performed to confirm that TSC2 was a bona fide target for the PEX5 import receptor.

Figure 6.

TSC1 and TSC2 interact with PEX19 and PEX5. (a) Immunoprecipitation was performed with anti-PEX5 (left panel), anti-PEX19 (right panel) in HEK 293 cells and immunoblotted for endogenous TSC1, TSC2, mTOR (negative control) and PMP70, and PEX1 (PEX19 cargo) or catalase (PEX5 cargo). (b) Schematic of TSC2 C-terminus (aa1517 – aa1807) showing the GAP and PEX5 binding sequence (PxBS), naturally occurring mutations and the re-introduced SKL sequence. (c) Representative images of FAO cells transfected with DsRed-Del-ARL (deleted ARL sequence) (red) and GFP-PTS1 (green) (top panel). FAO cells were also transfected with DsRed-ARL (red) and stained for PMP70 or catalase (green) as indicated. (Scale bar - 10μm). (d) HEK 293 cells expressing Flag-TSC2 wild type (WT) or Flag-TSC2 mutants (RQ, RW, and RG) were co-immunoprecipitated using anti-Flag or anti-PEX5, and blotted for PEX5 and Flag-TSC2. (e) Representative experiment showing subcellular fractionation of HEK 293 cells overexpressing Flag-TSC2 wild type (WT) and Flag-TSC2 mutants (RQ, RW and RG). Lysates from peroxisome (P) or membrane (M) fractions and whole cell extracts (WCE) were immunoblotted with Flag or PMP70 antibodies. (f) Co-immunoprecipitation of HEK 293 cells overexpressing Flag-TSC2 wild type (WT), or Flag-TSC2 mutants (RQ) or Flag-TSC2 rescue mutant (RQ-9NT) using anti-Flag antibody or control IgG and immunoblotted with anti-Flag and anti-PEX5 antibodies. (g) Subcellular fractionation of TSC2−/− MEFs transfected with Flag-TSC2 wild type (WT), or Flag-TSC2 mutants (RQ or RQ-9NT). β-integrin and catalase were used as subcellular markers for membrane (M) and peroxisome (P) fractions, respectively. WCE – whole cell extract. The arrow indicates the position of overexpressed Flag-TSC2. (h) HEK 293 cells co-transfected with Flag-TSC1 and Flag-TSC2 wild type (WT) or Flag-TSC2 G294E mutant (TSC2 mutant that cannot bind TSC1). Lysates were immunoprecipitated using anti-PEX19 and blotted for PEX19 and Flag. (i) Representative blots from subcellular fractionation of HEK 293 cells overexpressing wild type (WT) or mutant (CaaX mutant) Flag-Rheb. LDH, Lamin A/C and catalase were used as subcellular markers for the cytoplasmic (Cp), nuclear (N), and peroxisome (P) fractions, respectively. WCE – whole cell extracts. Uncropped images of western blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. S6.

In silico analysis of the TSC2 [http://peroxisomedb.org34] identified a region of homology with known PTS1 sequences. This ARL motif 1739KWIARLRHIKR1749 was located 63 amino acids from the C-terminal of TSC2 protein (Fig. 6b). Although the majority of PEX5 targets identified to date contain a PTS1 at their extreme C-terminus22, internal sequences may mediate some peroxisomal targeting35–37. To demonstrate this ARL sequence functioned as a PTS1, we substituted the ARL sequence for an SKL PTS1 motif in a DsRed-SKL fusion protein that localizes to the peroxisome. The DsRed-ARL fusion protein co-localized with a GFP fusion protein containing the SKL PTS1, and peroxisome marker PMP70 and catalase (Fig. 6c), whereas deletion of the inserted ARL sequence in this DsRed fusion protein (DsRed-Del-ARL) resulted in loss of cytoplasmic staining (Fig. 6c, top panel), indicating that a C-terminal ARL motif was capable of targeting proteins to the peroxisome in mammalian cells.

Importantly, several pathogenic TSC2 mutations were identified in this ARL site (Table 1). To determine whether TSC2 localization to the peroxisome was impaired by these mutations, we introduced three naturally occurring mutations into a wild-type TSC2 (WT) expression construct at amino acid position 1743, R1743Q (RQ), R1743G (RG) and R1743W (RW) (Table 1 and Fig. 6b). All three TSC2 mutants reduced PEX5 import receptor association with TSC2 (Fig. 6d), identifying this ARL sequence as a PEX5 binding sequence (PxBS) in TSC2. Peroxisomal localization of all three PxBS mutants was greatly diminished (Fig. 6e and Supplementary Fig. S4a); the PxBS TSC2 mutants, co-localized with neither lysosome (Supplementary Fig. S4b), nor endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Calnexin) nor mitochondria (voltage-dependent anion channel=VDAC) markers (Supplementary Fig. S4c). Importantly, introduction of nine nucleotides encoding an exogenous SKL PTS1 into the TSC2-RQ mutant, just before the C-terminal stop codon (TSC2-RQ-9NT) (Fig. 6b) restored PEX5 binding to TSC2-RQ-9NT (Fig. 6f) and peroxisome localization of TSC2-RQ-9NT (Fig. 6g).

Table 1.

Disease causing mutations of TSC2 PEX5 binding sequence (PxBS) disrupts TSC2’s peroxisome localization

| Exon/Intron | Mutation | # Reported | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exon 40 | 5227 c>g, 1743 R>G | 1 | Probably pathogenic |

| Exon 40 | 5227 c>t, 1743 R>W | 28 | Pathogenic |

| Exon 40 | 5228 g>a, 1743 R>Q | 18 | Pathogenic |

| Exon 40 | 5228 g>c, 1743 R>P | 1 | Pathogenic |

| Exon 40 | 5228 g>t, 1743 R>L | 1 | Probably pathogenic |

Consistent with the proposed function of TSC1 as the membrane “tether” for TSC226, 38, endogenous TSC1 co-immunoprecipitated with PEX19, which localizes proteins to peroxisomal membranes, but not PEX5 (Fig. 6a), and we identified a potential PEX19 binding site in TSC1 at the amino terminal (129LTTGVLvLIt138) [http://peroxisomedb.org34]. While a very small amount of Flag-TSC2 was associated with the PEX19-TSC1 complex (Fig. 6h), this association was abrogated with the TSC2-G294E mutant (a TSC1 binding-deficient mutant39), indicating the little TSC2 detected in this complex was likely associated with TSC1, rather than directly bound to PEX19 (Fig. 6h). As a control we demonstrated that mTOR (another large protein), did not co-immunoprecipitated with either PEX5 or PEX19 (Fig. 6a). Rheb did not contain predicted PTS sequences, however, farnesylation of the C-terminal CaaX (Cysteine aliphatic aliphatic any) motif has been previously shown to localize Rheb to endomembranes and be required for Rheb activation of mTORC13. We found that in contrast to WT-Rheb, CaaX defective Rheb was not detected in the peroxisomal fraction of cells (Fig. 6i).

TSC functions at the peroxisome to suppress mTORC1

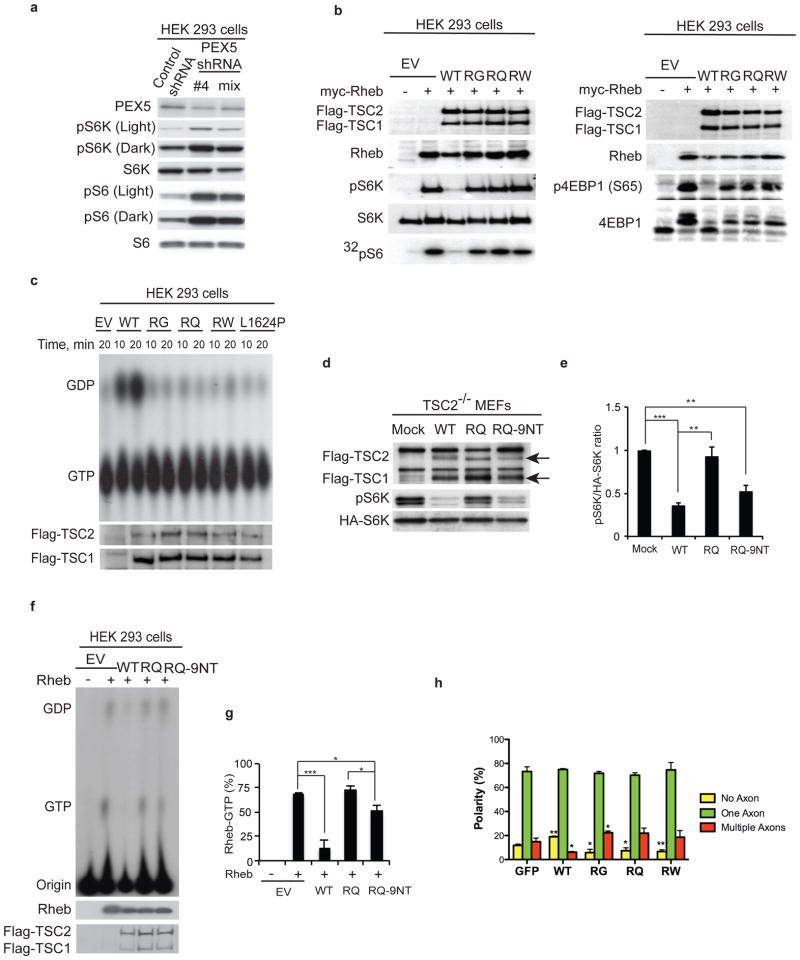

Inactivating PEX5 using shRNA to inhibit delivery of TSC2 to the peroxisome increased mTORC1 signaling (Fig. 7a), suggesting that localization to the peroxisome played a role in TSC GAP activity for Rheb and suppression of mTORC1 signaling. Functional assays in cells expressing Flag-tagged WT-TSC2 or PxBS TSC2 mutants (RQ, RW, and RG) co-transfected with Flag-TSC1, myc-Rheb and either HA-S6K (Fig. 7b, left panel) or HA-4E-BP1 (Fig. 7b, right panel) showed that while WT-TSC2 suppressed Rheb activation of mTORC1 (evidenced by decreased phosphorylation of S6K1 and 4E-BP1 and [32P]-radiolabeled-S6), all three pathogenic PxBS TSC2 mutants were deficient in mTORC1 repression (Fig. 7b). Inability to suppress mTORC1 signaling was not due to inability to bind TSC1, as control experiments revealed equivalent binding to TSC1 of WT-TSC2 and mutants (RQ, RG, and RW) (Supplementary Fig. S4d).

Figure 7.

TSC2 functions at the peroxisome to repress mTORC1. (a) HEK 293 cells were transfected with either control shRNA or a PEX5 targeting shRNA, and lysates were blotted using pS6K (T389), S6K, pS6 (S235/236) and S6 antibodies. (b) TSC2 functional assay was performed in HEK 293 cells co-expressing myc-Rheb, Flag-TSC1 and Flag-TSC2 wild type (WT), or Flag-TSC2 mutants (RG, RQ and RW) and HA-S6K (left panel) or HA-4EBP1 (right panel). Cells transfected with empty vector (EV) with or without myc-Rheb were used as controls. Lysates were further analyzed for phospho-S6K (T389), S6K, phospho-4EBP1 (S65), 4EBP1 and 32P-incorporation into S6. (c) Rheb GTPase activity assays was performed by co-immunoprecipitating TSC heterodimers from HEK 293 cells expressing Flag-TSC1 and Flag-TSC2 wild type (WT), Flag-TSC2 mutants (RG, RQ and RW), or Flag-TSC2 GAP-mutant (L1624P) performed for the indicated time. (d) TSC2 functional assay was performed using TSC2−/− MEFs co-transfected with Flag-TSC1, HA-S6K, and Flag-TSC2 wild type (WT) or Flag-TSC2 mutants (RQ or RQ-9NT), with mock transfected cells as controls. Arrows denote the positions of Flag-TSC1 and Flag-TSC2. (e) Quantitation of the ratio of phospho-S6K to total HA-S6K from Fig 7d. (±s.e.m., n = 3 independent experiments). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. (f) In vivo guanine nucleotide loading assays of Rheb was measured using HEK 293 cells overexpressing Flag-TSC1 and Flag-TSC2 wild type (WT), or Flag-TSC2 mutants (RQ and RQ-9NT) with or without Rheb as indicated. (g) Graph shows quantitation of the percentage of Rheb bound to GTP (indicative of Rheb GTPase activity, ±s.e.m., n = 4 independent experiments). *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. (h) Quantification of axon number in hippocampal neurons co-transfected with GFP, Flag-TSC1 and Flag-TSC2 WT or Flag-TSC2 mutants (RG, RQ, and RW). No axons = yellow, one axon = green, and multiple axons = red. Quantification was performed on 150–250 neurons from each of the 3 independent experiment and the results are represented as polarity (%). All error bars represent s.e.m., *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 compared to GFP only transfected control. Uncropped images of western blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. S6. Source data of statistical analysis are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

To determine directly whether inability to localize to the peroxisome compromised the Rheb GAP activity of PxBS mutants, we compared their GTPase activity with WT-TSC2, using immunoprecipitated TSC heterodimers against GST-Rheb preloaded with [α-32P]-GTP. In this in vitro assay, WT-TSC2 promoted the intrinsic GTPase activity of Rheb as observed by accumulation of [α-32P]-GDP bound Rheb, while none of the PxBS mutants functioned as a Rheb GAP, similar to what was observed in control experiments with the TSC2 GAP domain mutant (L1624P) protein (Fig. 7c). This suggests that TSC2 GAP activity depends on the delivery of TSC2 to the peroxisome. However, addition of the SKL PTS1 to the TSC2-RQ mutant restored significant repression of mTORC1 signaling (Fig. 7d,e and Supplementary Fig. S4e). This was confirmed in the in vivo Rheb guanine nucleotide binding assay, which demonstrated that TSC2-RQ-9NT had regained significant Rheb GAP activity (Fig. 7f,g), indicating a significant proportion of loss of activity in this mutant was attributable to loss of peroxisome localization, rather than loss of intrinsic GAP activity.

Overexpression of TSC1and TSC2 inhibits axon growth, resulting in an increased proportion of neurons with no axon, while loss of TSC1 and TSC2 results in an aberrant neuronal morphology with multiple axons extending out of the cell body, a phenotype dependent on hyperactivation of mTORC140. Expression of WT-TSC2 resulted in a significant increase in the number of neurons with no axon and a significant decrease in neurons with multiple axons, compared to controls expressing GFP alone (Fig. 7h). In comparison, all three of the PxBS TSC2 mutants when transfected with TSC1 had the opposite effect, significantly reducing the fraction of cells with no axons and increasing the number of cells with multiple axons (Fig. 7h), providing a functional link between loss of TSC signaling at the peroxisome and the neuronal pathophysiology of TSC.

DISCUSSION

Here we describe an intimate and previously unappreciated, relationship between the TSC signaling node and the peroxisome. We found TSC1 and TSC2 bound to PEX19 and PEX5, respectively, and an ARL sequence required for PEX5 binding and localization to peroxisomal membranes was identified. Missense mutations within the TSC2 ARL sequence are pathogenic41, 42, and TSC2’s ability to suppress mTORC1 in response to ROS is abrogated by these mutations. Neuronal expression of PxBS mutant TSC2 causes the formation of multiple axons, indicating that peroxisomal TSC2 localization is crucial for proper neuronal morphology and polarity, and providing a link between aberrant TSC signaling and brain pathophysiology. This suggests a model (Supplementary Fig. S5), where the TSC tumor suppressor resides on the exterior of peroxisomal membranes, in proximity to its GAP target Rheb, and where it can be negatively regulated by cytosolic kinases such as AKT and 14-3-3 binding, and activated by peroxisomal ROS to repress mTORC1 and induce autophagy.

PTS1 sequences located at the extreme C-terminus of cargo proteins, interact with the C-terminal region of PEX5 via the seven tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domains22. The ARL sequence in TSC2 that functions as a PEX5-binding domain is 63 amino acids internal from the C-terminus. While an ARL sequence at the C-terminus can function as a PTS1 to target proteins to the peroxisome in yeast43, plants44 and as we demonstrated with a DsRed-ARL fusion protein in mammalian cells, for an internal ARL to act as a true PTS1, the protein loop containing this ARL sequence must be accommodated in the well-characterized ring-like structure formed by the PEX5-TPR domains36. However, an increasing number of PEX5 dependent targets have been discovered where a PTS1 motif is not essential or even absent36, 37, and internal sequences that mediate PEX5 binding have been proposed37. For example, yeast Acyl-CoA oxidase (Pox1p) interacts directly with PEX5 but does not contain any recognizable PTS1, and C-terminal deletions of Pox1p do not affect PEX5 interaction45.

Current dogma dictates that PEX5 cargo is delivered to the matrix of the peroxisome. We demonstrated that TSC2 is part of the PEX5 import complex, but is localized to the peroxisomal membrane facing the cytosol. We considered two possibilities to potentially explain this conundrum: 1) TSC2 docks with TSC1 to be retained at the cytosolic membrane, abrogating import by PEX5; 2) TSC2 is delivered into the matrix and then recycles out to the cytosolic membrane. If the TSC2-TSC1 heterodimer is more stable than TSC2-PEX5 complex, peroxisomal TSC1 may function as an “attractor” or “anchor” to capture TSC2 at the cytosolic peroxisomal membrane, abrogating PEX5-mediated import of TSC2 into the matrix. Alternatively, the TSC2-PEX5 complex may enter the peroxisome matrix via PEX14 peroxisomal translocation machinery and then recycle out to interact with peroxisomal membrane-localized TSC1. Such peroxisomal protein recycling is well described for PEX522, and also occurs with rotavirus VP4 protein46, 47.

Specific localization of TSC and mTOR to several subcellular compartments has been reported, including lysosome or endosome13–18, 23, cytosol26, 48, 49, Golgi apparatus50 and nucleus48, 51. Interesting, Rheb was recently localized to mitochondrial membranes, where it was shown to regulate mitophagy52. While shuttling between these compartments is likely to occur, TSC1, TSC2 and mTOR resident in these various compartments may respond to specific stimuli. For example, mTOR is localized to the late endosome or lysosome compartment by the Ragulator complex in response to amino acids13, 16–18, and the TSC1-TSC2-TBC1D7 “Rhebulator” complex has been reported to be regulated by growth factors and energy stress in lysosomes23. Our finding of a TSC signaling node resident in peroxisome that responds to ROS identifies a subcellular compartment in which TSC functions to repress mTORC1 and induce autophagy in response to oxidative stress. Induction of autophagy is one of many cellular responses to oxidative stress, with superoxide (which is produced by peroxisomes) being the major ROS regulating autophagy27. Cytoplasmic ATM, which responds to ROS to activate AMPK and TSC219, has been previously localized to peroxisomes and a putative PTS1 sequence identified at its C-terminus53. ATM is directly activated by reactive oxygen species (ROS), with the oxidized form of this kinase forming an active di-sulfide cross-linked dimer54. Localization of ATM and the TSC signaling node to the peroxisome sets up the intriguing possibility that direct activation of ATM by peroxisomal ROS is the proximal signal that engages TSC to repress mTORC1, indicating characterization of this, and elucidation of other signaling cascades resident at the peroxisome, now merit further study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Gordon Mills and Yiling Lu (University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX) for the MCF7 cell line stably expressing GFP-LC3, and RIKEN BRC for providing the ATG5+/+ MEFs and ATG5−/−MEFs. We are also grateful for the assistance of Mr. Kenneth Dunner in electron microscopy image acquisition and analysis and Tia Berry, Xuefei Tong, and Sean Hensley for technical assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R01 CA143811 to C.L.W., NIH R01CA157216 to M.B.K., NIH R01NS058956, John Merck Fund, Children’s Hospital Boston Translational Research Program to M.S. A.R.T. was supported by the Association for International Cancer Research Career Development Fellowship [No. 06-914/915].

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.Z., J.K. and C.L.W designed research; J.Z., J.K., A.A., S.C., D.N.T., R.D., A.R.T., J.T.-M., A.D.N., J.M.H., E.K., E.A.D. and K.M.D., performed research; J.Z., J.K., A.R.T., R.D.F., P.L.F., M.B.K., M.S. and C.L.W analyzed data; J.Z., J.K. and C.L.W wrote the paper.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Crino PB, Nathanson KL, Henske EP. The tuberous sclerosis complex. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1345–1356. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra055323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gomez MR, Sampson JR, Whittemore VH. Tuberous sclerosis complex. 3. Oxford University Press; New York; Oxford: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aspuria PJ, Tamanoi F. The Rheb family of GTP-binding proteins. Cell Signal. 2004;16:1105–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang J, Manning BD. The TSC1-TSC2 complex: a molecular switchboard controlling cell growth. Biochem J. 2008;412:179–190. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He C, Klionsky DJ. Regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:67–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102808-114910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hosokawa N, et al. Nutrient-dependent mTORC1 association with the ULK1-Atg13-FIP200 complex required for autophagy. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1981–1991. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung CH, et al. ULK-Atg13-FIP200 complexes mediate mTOR signaling to the autophagy machinery. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1992–2003. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan KL. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:132–141. doi: 10.1038/ncb2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klionsky DJ, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy. 2012;8:445–544. doi: 10.4161/auto.19496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Levine B. Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell. 2010;140:313–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nazio F, et al. mTOR inhibits autophagy by controlling ULK1 ubiquitylation, self-association and function through AMBRA1 and TRAF6. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:406–416. doi: 10.1038/ncb2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu L, et al. Termination of autophagy and reformation of lysosomes regulated by mTOR. Nature. 2010;465:942–946. doi: 10.1038/nature09076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sancak Y, et al. The Rag GTPases bind raptor and mediate amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Science. 2008;320:1496–1501. doi: 10.1126/science.1157535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sengupta S, Peterson TR, Sabatini DM. Regulation of the mTOR complex 1 pathway by nutrients, growth factors, and stress. Mol Cell. 2010;40:310–322. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jewell JL, Russell RC, Guan KL. Amino acid signalling upstream of mTOR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:133–139. doi: 10.1038/nrm3522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flinn RJ, Yan Y, Goswami S, Parker PJ, Backer JM. The late endosome is essential for mTORC1 signaling. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:833–841. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-09-0756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korolchuk VI, et al. Lysosomal positioning coordinates cellular nutrient responses. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:453–460. doi: 10.1038/ncb2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sancak Y, et al. Ragulator-Rag complex targets mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface and is necessary for its activation by amino acids. Cell. 2010;141:290–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexander A, et al. ATM signals to TSC2 in the cytoplasm to regulate mTORC1 in response to ROS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4153–4158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913860107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schrader M, Fahimi HD. Peroxisomes and oxidative stress. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:1755–1766. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wanders RJ, Waterham HR. Biochemistry of mammalian peroxisomes revisited. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:295–332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma C, Agrawal G, Subramani S. Peroxisome assembly: matrix and membrane protein biogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2011;193:7–16. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201010022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dibble CC, et al. TBC1D7 is a third subunit of the TSC1-TSC2 complex upstream of mTORC1. Mol Cell. 2012;47:535–546. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai SL, et al. Activity of TSC2 is inhibited by AKT-mediated phosphorylation and membrane partitioning. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:279–289. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inoki K, Guan KL. Tuberous sclerosis complex, implication from a rare genetic disease to common cancer treatment. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:R94–100. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plank TL, Yeung RS, Henske EP. Hamartin, the product of the tuberous sclerosis 1 (TSC1) gene, interacts with tuberin and appears to be localized to cytoplasmic vesicles. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4766–4770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Y, Azad MB, Gibson SB. Superoxide is the major reactive oxygen species regulating autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:1040–1052. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scherz-Shouval R, et al. Reactive oxygen species are essential for autophagy and specifically regulate the activity of Atg4. Embo J. 2007;26:1749–1760. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuma A, et al. The role of autophagy during the early neonatal starvation period. Nature. 2004;432:1032–1036. doi: 10.1038/nature03029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duclos S, Bride J, Ramirez LC, Bournot P. Peroxisome proliferation and beta-oxidation in Fao and MH1C1 rat hepatoma cells, HepG2 human hepatoblastoma cells and cultured human hepatocytes: effect of ciprofibrate. Eur J Cell Biol. 1997;72:314–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scotto C, Keller JM, Schohn H, Dauca M. Comparative effects of clofibrate on peroxisomal enzymes of human (Hep EBNA2) and rat (FaO) hepatoma cell lines. Eur J Cell Biol. 1995;66:375–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weller S, Gould SJ, Valle D. Peroxisome biogenesis disorders. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2003;4:165–211. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.4.070802.110424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harrington LS, Findlay GM, Lamb RF. Restraining PI3K: mTOR signalling goes back to the membrane. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schluter A, Real-Chicharro A, Gabaldon T, Sanchez-Jimenez F, Pujol A. PeroxisomeDB 2.0: an integrative view of the global peroxisomal metabolome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D800–805. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freitas MO, et al. PEX5 protein binds monomeric catalase blocking its tetramerization and releases it upon binding the N-terminal domain of PEX14. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:40509–40519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.287201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stanley WA, Wilmanns M. Dynamic architecture of the peroxisomal import receptor Pex5p. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:1592–1598. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Klei IJ, Veenhuis M. PTS1-independent sorting of peroxisomal matrix proteins by Pex5p. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:1794–1800. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamamoto Y, Jones KA, Mak BC, Muehlenbachs A, Yeung RS. Multicompartmental distribution of the tuberous sclerosis gene products, hamartin and tuberin. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;404:210–217. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00300-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hodges AK, et al. Pathological mutations in TSC1 and TSC2 disrupt the interaction between hamartin and tuberin. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:2899–2905. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.25.2899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choi YJ, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex proteins control axon formation. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2485–2495. doi: 10.1101/gad.1685008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coevoets R, et al. A reliable cell-based assay for testing unclassified TSC2 gene variants. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:301–310. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones AC, et al. Comprehensive mutation analysis of TSC1 and TSC2-and phenotypic correlations in 150 families with tuberous sclerosis. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:1305–1315. doi: 10.1086/302381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Szewczyk E, Andrianopoulos A, Davis MA, Hynes MJ. A single gene produces mitochondrial, cytoplasmic, and peroxisomal NADP-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase in Aspergillus nidulans. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37722–37729. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105645200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tilbrook K, Gnanasambandam A, Schenk PM, Brumbley SM. Efficient targeting of polyhydroxybutyrate biosynthetic enzymes to plant peroxisomes requires more than three amino acids in the carboxyl-terminal signal. J Plant Physiol. 2010;167:329–332. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klein AT, van den Berg M, Bottger G, Tabak HF, Distel B. Saccharomyces cerevisiae acyl-CoA oxidase follows a novel, non-PTS1, import pathway into peroxisomes that is dependent on Pex5p. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25011–25019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203254200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lazarow PB. Viruses exploiting peroxisomes. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2011;14:458–469. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mohan KV, Som I, Atreya CD. Identification of a type 1 peroxisomal targeting signal in a viral protein and demonstration of its targeting to the organelle. J Virol. 2002;76:2543–2547. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.5.2543-2547.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosner M, Freilinger A, Hengstschlager M. Akt regulates nuclear/cytoplasmic localization of tuberin. Oncogene. 2007;26:521–531. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Slegtenhorst M, et al. Interaction between hamartin and tuberin, the TSC1 and TSC2 gene products. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1053–1057. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.6.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wienecke R, et al. Co-localization of the TSC2 product tuberin with its target Rap1 in the Golgi apparatus. Oncogene. 1996;13:913–923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang X, Shu L, Hosoi H, Murti KG, Houghton PJ. Predominant nuclear localization of mammalian target of rapamycin in normal and malignant cells in culture. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:28127–28134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202625200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Melser S, et al. Rheb regulates mitophagy induced by mitochondrial energetic status. Cell Metab. 2013;17:719–730. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Watters D, et al. Localization of a portion of extranuclear ATM to peroxisomes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34277–34282. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.34277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guo Z, Kozlov S, Lavin MF, Person MD, Paull TT. ATM activation by oxidative stress. Science. 2010;330:517–521. doi: 10.1126/science.1192912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.