Abstract

Introduction:

To determine emergency physician (EP) opinions of prehospital patient care reports (PCRs) and whether such reports are available at the time of emergency department (ED) medical decision-making.

Methods:

Prospective, cross-sectional, electronic web-based survey of EPs regarding preferences and availability of prehospital PCRs at the time of ED medical decision-making.

Results:

We sent the survey to 1,932 EPs via 4 American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) email lists. As a result, 228 (11.8%) of email list members from 31 states and the District of Columbia completed the survey. Most respondents preferred electronic prehospital PCRs as opposed to handwritten prehospital PCRs (52.2% [95% confidence interval (CI): 49.1, 55.3] vs. 17.1% [95%CI: 11.7, 22.5]). The remaining respondents (30.5% [95%CI: 26.0, 35.0]) had no preference or had seen only one type of PCR. Of the respondents, 45.6% [95%CI: 42.1, 48.7] stated PCRs were “very important” while 43.0% [95% CI: 39.3, 46.7] rated PCRs as “important” in their ED practice. Most respondents (79.6% [95%CI: 76.5, 82.7]) reported electronic prehospital PCRs were available ≤50% of the time for medical decision-making while 20.4% [95%CI: 9.2, 31.6] reported that electronic prehospital PCRs were available > 50% of the time (P=0.00). A majority of participants (77.6% [95%CI: 74.5, 80.7]) reported that handwritten prehospital PCRs were available ≥ 50% while 22.4% [95%CI: 11.8, 33.0] of the time for medical decision-making (P=0.00).

Conclusion:

EPs in this study felt that prehospital PCRs were important to their ED practice and preferred electronic prehospital PCRs over handwritten PCRs. However, most electronic prehospital PCRs were unavailable at the time of ED medical decision-making. Although handwritten prehospital PCRs were more readily available, legibility and accuracy were reported concerns. This study suggest that strategies should be devised to improve the overall accuracy of PCRs and assure that electronic prehospital PCRs are delivered to the receiving ED in time for consideration in ED medical decision-making.

INTRODUCTION

The prehospital patient care report (PCR) is an essential tool for communicating pertinent prehospital patient and demographic data to hospital-based healthcare providers. The appearance of the patient prior to hospital arrival, and the prehospital treatment provided, can help speed and guide subsequent emergency department (ED) care.1–2 Because of this, the accuracy and timeliness of the prehospital PCR is important. In trauma, failure of prehospital personnel to document basic measures of scene physiology has been associated with increased mortality.3

The prehospital PCR also plays an important role in research, quality improvement, and protocol development.4 Recently, there have been attempts to link prehospital and hospital datasets to better study the impact of prehospital care on patient morbidity and mortality.5–6 The need for standardized datasets, uniform and reliable data transmission, integrated information systems, and provision of feedback to prehospital providers was a recommendation in the Emergency Medical Services Agenda for the Future.7 With the advent of electronic prehospital PCRs, many of the goals stated in this document are now possible.8 Electronic prehospital PCRs are now widely available and commonly used in many emergency medical services (EMS) systems. Despite this change, there are still barriers to timely and accurate information delivery.9 Most modern electronic prehospital PCR systems use an internet-based network and/or telefacsimile (FAX) transmission to deliver the prehospital information to the receiving facility.

A recent transition from handwritten prehospital PCRs to electronic prehospital PCRs was completed in the Las Vegas, Nevada EMS system. Following that change, it was observed that the electronic prehospital PCR was less frequently available for ED medical decision-making when compared to the availability of the older handwritten PCRs. Because of this observation we sought to survey emergency physicians (EP) in regard to their opinion of PCRs and the timeliness of data delivery to other hospital EDs.

METHODS

We conducted a cross-sectional, prospective, electronic web-based survey (SurveyMonkey; Palo Alto, California) of EPs regarding prehospital PCRs. We established the protocol and developed a 23-question survey instrument. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of University Medical Center of Southern Nevada in Las Vegas, Nevada reviewed the protocol and granted exempt status.

The survey instrument was developed for EPs and contained 2 sections. The first section (12 questions) surveyed physician opinions regarding both electronic and handwritten PCRs. Of these 12 questions, 4 surveyed physician opinions of perceived benefits and limitations of PCRs based upon experience at our institution (University Medical Center of Southern Nevada; Las Vegas, Nevada). The remaining 11 questions surveyed physician demographics (state of residence, board certification, certifying board, years in practice, age range, practice setting, annual ED volume, gender, computer preference, type of ED recordkeeping). These questions were vetted by the researchers and uploaded to the SurveyMonkey system.

On April 12, 2012, a request to complete the survey was sent to the email lists of 3 state chapters (Arizona, Nevada, and Utah) and the email list of the EMS section of the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP). The study was limited to physicians. The email contained a brief overview of the study and a URL link to the survey document. Data collection continued for 1 month. Following the study period we gathered and analyzed the data using the worksheet and statistical functions of Microsoft Excel for Mac 2011 (Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, Washington). We determined significance between groups using Fisher’s exact test.

RESULTS

We sent the survey to 1,932 EPs via the 4 email lists. Two hundred twenty-eight self-identified EPs responded to the survey. The overall survey return rate, based upon the number of physicians on the 4 email lists, was 11.8%. Every respondent who returned the survey completed all of the core (PCR) questions (although 5 failed to list their state of residence).

Cohort Demographics

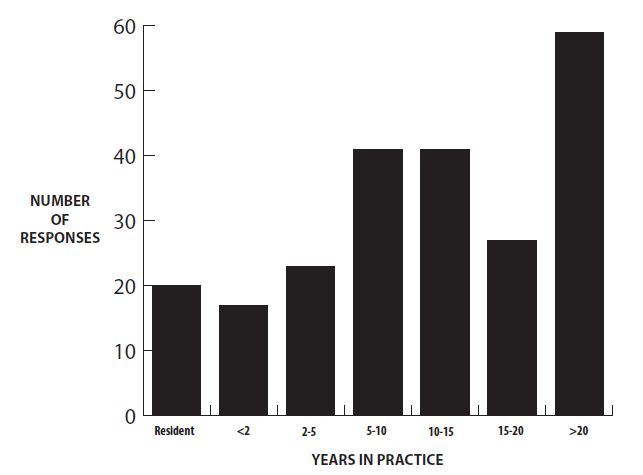

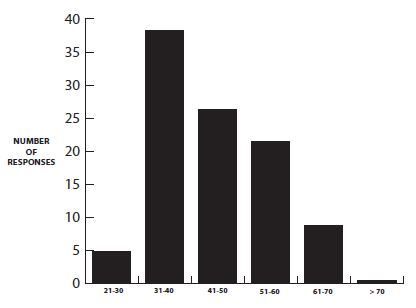

Of the 228 respondents, 173 (75.9%) were male and 55 (24.1%) were female. The respondents were from 31 states and the District of Columbia (Table 1). Respondents described their practice location as urban (61.8%), suburban (27.6%), rural (9.6%), or frontier (0.9%). Most of the respondents (88.6%) were board certified with most (97% of those board certified) reporting board certification in emergency medicine. Physician experience (years in practice) is detailed in Figure 1. Physician age range is detailed in Figure 2. Respondents listed their computer preference as Apple/Mac (43.4% [95% confidence interval (CI): 39.7, 47.1]), Windows/PC (38.6%; 95%CI: 34.6, 42.6), or no preference (18% [95% CI: 12.6, 23.4]).

Table 1.

Respondents by state.

| State | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Arkansas | 1 | 0.4% |

| Alabama | 1 | 0.4% |

| Arizona | 74 | 32.5% |

| California | 4 | 1.7% |

| Colorado | 4 | 1.7% |

| District of Columbia | 1 | 0.4% |

| Florida | 4 | 1.7% |

| Georgia | 1 | 0.4% |

| Illinois | 5 | 2.2% |

| Indiana | 1 | 0.4% |

| Massachusetts | 6 | 2.6% |

| Maryland | 3 | 1.3% |

| Maine | 1 | 0.4% |

| Michigan | 2 | 0.9% |

| Minnesota | 3 | 1.3% |

| Montana | 1 | 0.4% |

| North Carolina | 1 | 0.4% |

| New Hampshire | 1 | 0.4% |

| New Jersey | 7 | 3.1% |

| Nevada | 26 | 11.4% |

| New York | 5 | 2.2% |

| Ohio | 6 | 2.6% |

| Oklahoma | 1 | 0.4% |

| Oregon | 1 | 0.4% |

| Pennsylvania | 10 | 4.4% |

| South Carolina | 2 | 0.9% |

| Texas | 5 | 2.2% |

| Utah | 35 | 15.4% |

| Virginia | 4 | 1.7% |

| Wisconsin | 3 | 1.3% |

| West Virginia | 1 | 0.4% |

| Wyoming | 1 | 0.4% |

| Not available | 7 | 3.1% |

| Total | 228 | 99.4% |

Figure 1.

Physician experience by years in practice.

Figure 2.

Age range of physicians surveyed.

PCR Responses

In this study, 186 (81.6%) respondents reported encountering electronic prehospital PCRs in the course of their practice while 42 (18.4%) respondents had not. Two hundred (87.7%) respondents reported encountering handwritten prehospital PCRs in the course of their practice while 28 (12.3%) had not (See Table 2). Respondents preferred electronic prehospital PCRs to handwritten prehospital PCRs (52.2% [95% CI: 49.1, 55.3] vs. 17.1% [95% CI: 11.7, 22.5]). Some respondents (15.4% [95% CI: 9.9, 20.9]) had only encountered one type of prehospital PCR while others (15.4% [95% CI: 9.9, 20.9]) had no preference for electronic or handwritten PCRs.

Table 2.

Survey responses regarding prehospital patient care records

| Number | Question | Response rate | Responses | Respondents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Do you encounter electronic EMS patient care reports in the course of your emergency medicine practice? | 228 (100%) | Yes | 186 (81.6%) |

| No | 42 (18.4%) | |||

| 2 | Do you encounter handwritten EMS patient care reports in the course of your emergency medicine practice? | 228 (100%) | Yes | 200 (87.7%) |

| No | 28 (12.3%) | |||

| 3 | Which type of EMS patient care report do you prefer? | 228 (100%) | Electronic | 119 (52.2%) |

| Handwritten | 39 (17.1%) | |||

| Only one type encountered | 35 (15.4%) | |||

| No Preference | 35 (15.4%) | |||

| 4 | What benefits do you derive from electronic EMS patient care reports? | 228 (100%) | Accuracy | 25 (11.0%) |

| Ease of finding information | 68 (29.8%) | |||

| I don’t see ePCRs | 37 (16.2%) | |||

| Legibility | 171 (75.0%) | |||

| No benefits | 17 (7.5%) | |||

| Risk management | 29 (12.7%) | |||

| Standard format | 86 (27.7%) | |||

| Timeliness of report delivery | 29 (12.7%) | |||

| Other | 7 (3.1%) | |||

| 5 | What benefits do you derive from handwritten EMS patient care reports? | 228 (100%) | Accuracy | 31 (13.6%) |

| Ease of finding information | 39 (17.1%) | |||

| I don’t see hPCRs | 15 (6.6%) | |||

| Legibility | 2 (0.9%) | |||

| No benefits | 43 (18.9%) | |||

| Risk management | 6 (2.6%) | |||

| Standard format | 25 (11.0%) | |||

| Timeliness of report delivery | 148 (64.9%) | |||

| Other | 24 (10.5%) | |||

| 6 | What limitations do you see or dislikes do you have in regard to electronic EMS patient care reports? | 228 (100%) | Accuracy | 35 (15.4%) |

| Ease of finding information | 60 (26.3%) | |||

| I don’t see ePCRs | 34 (14.9%) | |||

| Legibility | 2 (0.9%) | |||

| No benefits | 17 (7.5%) | |||

| Risk management | 17 (7.5%) | |||

| Standard format | 19 (8.3%) | |||

| Timeliness of report delivery | 130 (57.0%) | |||

| Other | 49 (21.5%) | |||

| 7 | What limitations do you see or dislikes do you have in regard to handwritten EMS patient care reports? | 228 (100%) | Accuracy | 35 (15.4%) |

| Ease of finding information | 56 (24.6%) | |||

| I don’t see hPCRs | 11 (4.8%) | |||

| Legibility | 204 (59.5%) | |||

| No benefits | 6 (2.6%) | |||

| Risk management | 29 (12.7%) | |||

| Standard format | 39 (17.1%) | |||

| Timeliness of report delivery | 21 (9.2%) | |||

| Other | 12 (5.3%) | |||

| 8 | How important is the information in the prehospital patient care report to your practice as an emergency physician in caring for patients transported by EMS? | 228 (100%) | Very important | 105 (45.6%) |

| Important | 98 (43.0%) | |||

| Neutral | 17 (7.5%) | |||

| Not important | 3 (1.3%) | |||

| Rarely important | 6 (2.6%) | |||

| 9 | How frequently is the electronic prehospital patient care record available when emergency department (ED) medical decision-making occurs in your practice? | 228 (100%) | 100% of the time | 6 (2.6%) |

| 75% of the time | 34 (14.9%) | |||

| 50% of the time | 51 (22.4%) | |||

| 25% of the time | 69 (30.3%) | |||

| 0% of the time | 36 (15.8%) | |||

| Not applicable | 32 (14.0% | |||

| 10 | How frequently is the handwritten prehospital patient care record available when ED medical decision-making occurs in your practice? | 228 (100%) | 100% of the time | 34 (14.9%) |

| 75% of the time | 83 (38.4%) | |||

| 50% of the time | 42 (18.4%) | |||

| 25% of the time | 36 (15.8%) | |||

| 0% of the time | 10 (4.4%) | |||

| Not applicable | 23 (10.1%) | |||

| 11 | Do you feel that electronic EMS reports increase your medico-legal risk? | 228 (100%) | Yes | 50 (21.9%) |

| No | 83 (40.8%) | |||

| Neutral | 85 (37.3%) | |||

| 12 | Do you feel that handwritten EMS reports increase your medico-legal risk? | 228 (100%) | Yes | 52 (22.8%) |

| No | 101 (44.3%) | |||

| Neutral | 75 (32.9%) |

EMS, emergency medical services; ePCR, electronic patient care report; hPCR, handwritten patient care report

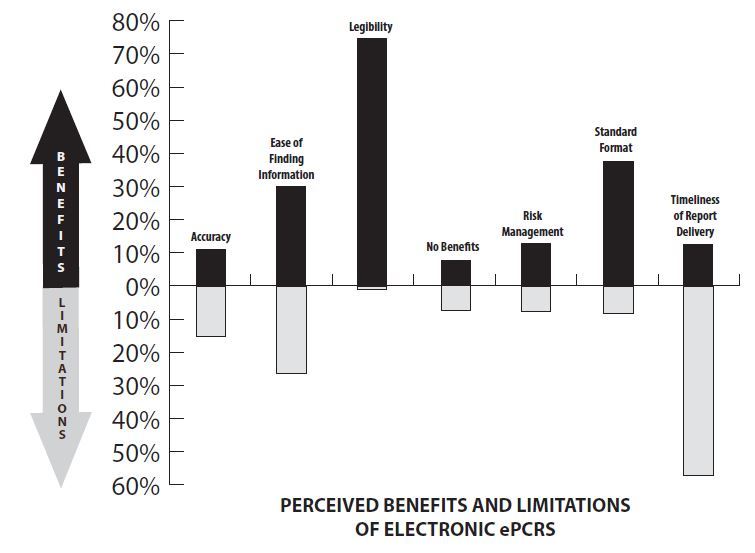

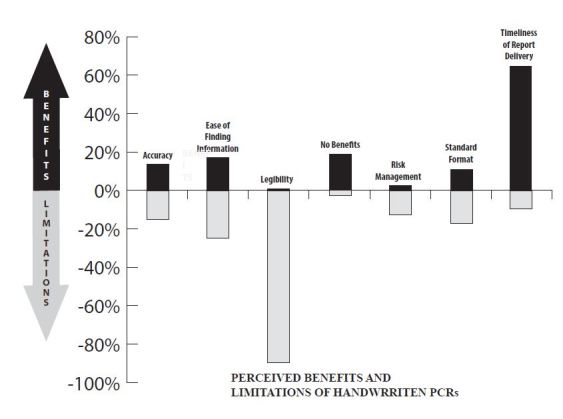

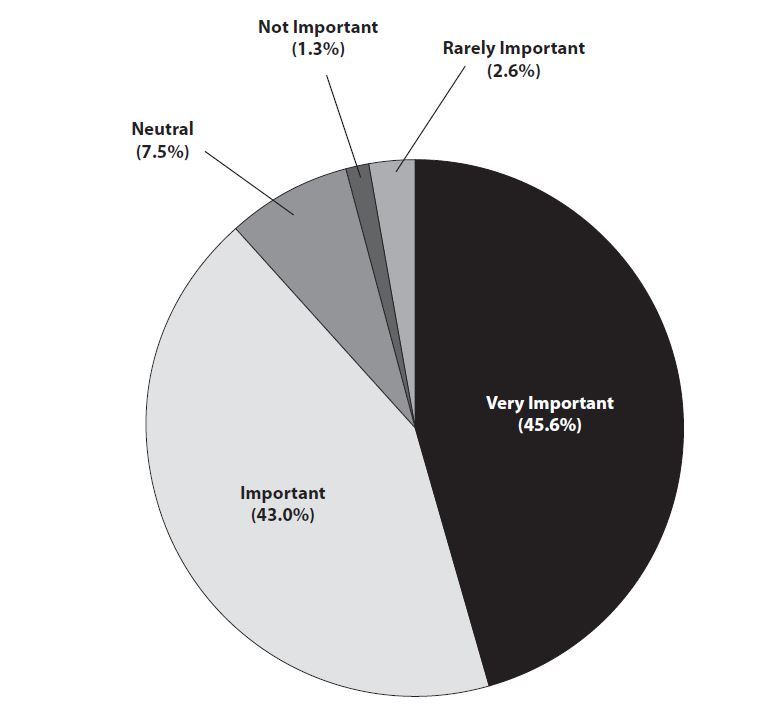

The respondents were also surveyed in regard to the perceived benefits and limitations of electronic prehospital PCRs (Figure 3). The perceived limitations of handwritten prehospital PCRs are detailed in Figure 4. Of the respondents, 104 (45.6% [95%CI: 42.1, 48.7]) stated prehospital PCRs were “very important,” while 98 (43.0% [95% CI: 39.3, 46.7]) respondents stated they were “important” in their practice. Twenty-six (11.4% [95%CI: 6.1, 16.7]) respondents stated prehospital PCRs were “not important,” “rarely important,” or were “neutral” in regard to the importance of PCRs in their practice (Figure 5). For 156 (79.6% [95%CI: 76.5, 82.7]) respondents, electronic prehospital PCRs were available ≤50% of the time for medical decision-making while 40 (20.4% [95%CI: 9.2, 31.6]) reported that electronic prehospital PCRs were available >50% of the time (P=0.00). A total of 169 (77.6% [95%CI: 74.5, 80.7]) respondents reported handwritten prehospital PCRs were available ≥50% of the time for medical decision-making while 45 (22.4% [95%CI: 11.8, 33.0]) were available <50% of the time (P=0.00) (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Respondents’ report of perceived benefits and limitations of electronic patient care reports.

Figure 4.

Respondents’ report of perceived benefits and limitations of handwritten patient care reports.

Figure 5.

Respondents’ opinion of the importance of prehospital patient care reports to their practice.

DISCUSSION

The demographics of our cohort, while primarily from western states, were similar to those of EPs in general in terms of gender, age, and years in practice.10 While prehospital PCRs are important to ED practice, problems with both types of PCRs (electronic and handwritten) were commonly reported in this survey. While handwritten prehospital PCRs were more frequently available for medical decision-making, respondents found legibility, accuracy, and ease of finding desired information problematic in this format. Most respondents preferred electronic prehospital PCRs because of legibility, standardized format, and ease of finding desired information. However electronic prehospital PCRs were often unavailable at the time of ED medical decision-making. Accuracy of prehospital data was a perceived problem in both report types.11

The communication of patient care data from the prehospital to hospital setting typically occurs in 3 steps: 1. Pre-arrival data (via radio or telephone), 2. Arrival data (handoff) at the time of patient arrival, and 3. Post-arrival delivery of summary medical and demographic data (either electronic or handwritten).12 Typically, pre-arrival data is limited.13 Most initial prehospital care information is obtained during the handoff of the patient from the EMS crew to the hospital staff. Studies have shown that much of the data transmitted at this point is not heard or remembered by physicians.14–16 Thus, when final medical decision-making occurs in the ED, the emergency physician often relies on the final prehospital PCR in addition to pre-arrival and arrival data.

The transition to electronic prehospital PCRs has allowed better integration of prehospital and hospital data.17–18 However, with this transition, additional technology is necessary to generate a report for the hospital (printers, internet interface, security framework). Presently, these technologies appear to be inadequate in delivering an accurate and legible report to receiving EDs in time for ED medical decision-making. Failure to provide essential prehospital patient care data to the treating ED staff can potentially adversely impact patient care. Strategies need to be devised to assure a more timely, if not contemporaneous, delivery of prehospital PCRs in time for ED medical decision-making. While such strategies are being developed, the present electronic prehospital PCR delivery system falls short of this goal.19

LIMITATIONS

There are numerous limitations to this study. First, cross-sectional surveys are subject to both sampling and non-sampling errors. Non-sampling errors include coverage errors, content and reporting errors, and non-reporting errors. There is the possibility of coverage error in this survey as most respondents were from western states (Arizona, Nevada, Utah). In addition, most respondents were from urban areas. Thus, findings from this survey may not have applicability to other geographic areas. The response rate was relatively low based upon the total number of email list members. It was impossible to determine exactly how many list members actually received the survey. There is also the possibility that some non-target subjects (e.g., non-physicians) completed the survey. While steps were taken to avoid this (e.g. questions about board certification and practice type), there is no way to assure that violations did not occur. Finally, the voluntary nature of surveys will result in some non-reporting from those with no interest in the survey topic. Likewise, this format may also foster a bias in those respondents with an interest or strong feelings regarding the nature of the survey questions. Thus, the information gained from this study may or may not be applicable to all EMS systems.

CONCLUSION

In this study, the surveyed EPs felt that PCRs are important to their ED practice and preferred electronic prehospital PCRs over handwritten PCRs. However, most electronic prehospital PCRs were unavailable at the time of ED medical decision-making. Although handwritten prehospital PCRs were more readily available, legibility and accuracy were reported concerns. This investigation suggests that strategies need to be devised to improve the overall accuracy of PCRs and assure that electronic prehospital PCRs are delivered to the receiving ED in time for consideration in ED medical decision-making.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Band RA, Gaieski DF, Hylton JH, et al. Arriving by emergency medical services improves time to treatment endpoints with severe sepsis or septic shock. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:934–940. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carr BG, Matthew Edwards R. Regionalized care for time-critical conditions: lessons learned from existing networks. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:1354–1358. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laudermilch DJ, Schiff MA, Nathens AB, et al. Lack of emergency medical services documentation is associated with poor patient outcomes: a validation of audit filters for prehospital trauma care. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cummins RO, Chamberlain DA, Abramson NS, et al. Recommended guidelines for uniform reporting of data from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: the Utstein Style. A statement for health professionals from a task force of the American Heart Association, the European Resuscitation Council, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, and the Australian Resuscitation Council. Circulation. 1991;84:960–975. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.2.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dawson DE. National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS) Prehosp Emerg Care. 2006;10:314–316. doi: 10.1080/10903120600724200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Figgis K, Slevin O, Cunningham JB. Investigation of paramedics’ compliance with clinical practice guidelines for the management of chest pain. Emerg Med J. 2010;27:151–155. doi: 10.1136/emj.2008.064816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emergency Medical Services Agenda for the Future. Washington DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landman AB, Lee CH, Sasson C, et al. Prehospital electronic patient care report systems: early experiences from emergency medical services agency leaders. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32692. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landman AB, Rokos IC, Burns K, et al. An open, interoperable, and scalable prehospital information technology network architecture. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2011;15:149–157. doi: 10.3109/10903127.2010.534235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cydulka RK, Korte R. Career Satisfaction on Emergency Medicine: The ABEM Longitudinal Study of Emergency Physicians. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:714–722. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brice JH, Friend KD, Delbridge TR. Accuracy of EMS-recorded patient demographic data. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2008;12:187–191. doi: 10.1080/10903120801907687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benner JP, Hilton J, Carr G, et al. Information transfer from prehospital to ED health care providers. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;6:233–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown E, Bleetman A. Ambulance alerting to hospital: the need for clearer guidance. Emerg Med J. 2006;23:811–814. doi: 10.1136/emj.2005.030858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carter AJ, Davis KA, Evans LV, et al. Information loss in emergency medical services handover of trauma patients. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2009;13:280–285. doi: 10.1080/10903120802706260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yong G, Dent AW, Weiland TJ. Handover from paramedics: observations and emergency department clinician perceptions. Emerg Med Australas. 2008;20:149–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2007.01035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scott LA, Brice JH, Baker CC, et al. An analysis of paramedic verbal reports to physicians in the emergency department trauma room. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2003;7:247–251. doi: 10.1080/10903120390936888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meislin HW, Spaite DW, Conroy C, et al. Development of an electronic emergency medical services patient care record. Prehosp Emerg Care. 1999;3:54–59. doi: 10.1080/10903129908958907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuisma M, Väyrynen T, Hiltunen T, et al. Effect of introduction of electronic patient reporting on the duration of ambulance calls. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:948–955. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giovanni MG, Shenvi R, Battles M, et al. Design of an eMonitor system to transport electronic patient care data (ePCR) information in unstable MobileIP wireless environment. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2008;6:1049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]