Background: The soluble SNARE Vam7p is recruited to membranes to form trans-SNARE complexes for fusion.

Results: Membrane recruitment is mediated through the Vam7p affinities for a tethering complex, phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate, and acidic lipids.

Conclusion: Several receptor interactions of modest affinity contribute to the high affinity binding of Vam7p to the membrane for fusion.

Significance: Vam7p targeting requires peripheral and integral vacuolar proteins, a phosphoinositide, and acidic lipids.

Keywords: Fusion Protein, Lipids, Membrane Fusion, SNARE, Yeast, Vacuole

Abstract

Vam7p, the vacuolar soluble Qc-SNARE, is essential for yeast vacuole fusion. The large tethering complex, homotypic fusion and vacuole protein sorting complex (HOPS), and phosphoinositides, which interact with the Vam7p PX domain, have each been proposed to serve as its membrane receptors. Studies with the isolated organelle cannot determine whether these receptor elements suffice and whether ligands or mutations act directly or indirectly on Vam7p binding to the membrane. Using pure components that are active in reconstituted vacuolar fusion, we now find that Vam7p binds to membranes through its combined affinities for several vacuolar membrane constituents: HOPS, phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate, SNAREs, and acidic phospholipids. Acidic lipids allow low concentrations of Vam7p to suffice for fusion; without acidic lipids, the block to fusion is partially bypassed by high concentrations of Vam7p.

Introduction

Targeted and regulated membrane fusion is the basis of neurotransmission, hormone secretion, cell growth, and subcellular compartmentation. Conserved lipids and proteins catalyze this process. These include the Rab family GTPases (1, 2); large multimeric tethering complexes that selectively bind to Rab:GTP (3); SNARE proteins from each membrane, which “snare” each other in 4-helical coiled coil complexes before fusion (4–7); SNARE chaperones, such as the Sec1/Munc18 (SM) family of proteins (8, 9); and the SNARE complex disassembly chaperones Sec18p/N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor and Sec17p/α-SNAP (soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein) (10, 11). Although fusion catalysts have been studied extensively in isolation or during their action in vivo or on isolated organelles that fuse in vitro, the paucity of reconstituted fusion reactions that require each of these catalysts (12–15) has limited our understanding of how they cooperate during fusion.

We study membrane fusion mechanisms with yeast vacuoles. Vacuoles undergo an initial reversible tethering that helps bring membranes into apposition, followed by the enrichment of fusion-specific factors around the edge of the apposed membrane domain (16). This leads to trans-SNARE complex formation. Fusion can be assayed by content mixing between the fused vacuoles (17). The small vacuolar Rab GTPase Ypt7p is required for fusion (1). It binds its effector complex, HOPS2 (3), a large multisubunit tethering factor. Together they mediate the initial membrane contact, which is required for SNARE complex assembly (18). The Sec17p/Sec18p SNARE chaperone system disassembles cis-SNARE complexes, providing free SNAREs for the formation of fusion competent trans-SNARE complexes (6). Certain lipids are important for fusion, including phosphoinositides (19–21), ergosterol (22), and diacylglycerol (23, 24). We have reconstituted this complex process of yeast vacuole fusion in vitro (12, 13) using purified vacuolar components, the SNAREs, SNARE chaperones, HOPS, Ypt7p, and lipids of vacuolar compositions in reconstituted proteoliposomes.

Vam7p is a soluble Qc-SNARE (25) that interacts with several other fusion proteins and lipids and thus offers a powerful vantage point for studies of fusion factor interactions. Its SNARE domain engages in SNARE complex formation with the other SNAREs on the vacuole, but Vam7p also makes other vital interactions (19, 20, 26, 27). Its in vivo membrane localization depends on the affinity of its N-terminal PX domain for phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate (PI(3)P) (20). This domain also has a direct affinity for the tethering complex HOPS, which, by itself, has a direct affinity for several phosphoinositides (26). Studies with purified vacuoles have suggested that the Vam7p receptor on this organelle may be phosphoinositides (20), other SNAREs (27), or the HOPS complex (26). Further definition of the Vam7p membrane receptor is inherently limited by the chemical complexity of the organelle and by the possibility that other factors will also be required, either indirectly or directly. We now show that Vam7p can be brought to the membrane through the combination of its moderate affinities for phosphoinositides, SNAREs, acidic lipids, and HOPS. The “true” receptor is actually a cooperating set of binding interactions with other fusion factors, both peripheral membrane proteins (HOPS) and integral membrane proteins (other SNAREs) as well as specific lipids (PI(3)P and acidic lipids).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Reagents

The HOPS complex (28); the SNAREs Vti1p, Nyv1p, and Vam3p (12); GST-Vam7p (29); Ypt7p (29); and Vam7p (30) were purified as described. Anti-Vps33p (3), anti-Vam7p (31), anti-Vti1p (30), and anti-Nyv1p (32) were also purified as described.

Fluorescein-labeled Vam7p

Purified Vam7p (2.8 mg/ml in 300 mm NaCl, 20 mm HEPES·NaOH, pH 7.4, 10% glycerol, 50 mm DTT) was gel-filtered using a Sephacryl-300 column to remove DTT. The protein was concentrated to 2.5 mg/ml using Amicon Ultra 20,000 molecular weight cut-off filters (3200 rpm, 10 min, 4 °C) in a Thermo Scientific CL-2 centrifuge. Ellman's test (33) was performed to confirm the complete removal of DTT. To the pooled, DTT-free Vam7p, a 10-fold molar excess of both fluorescein 5-maleimide and tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine was added while vortexing. Incubation at 25 °C for 4 h caused virtually complete derivatization. The sample was then gel-filtered through Sephadex G-25 to separate free fluorescein from tagged Vam7p. Fractions containing both fluorescence (λex = 485 nm, λem = 525 nm; emission cut-off, none; SpectraMAX Gemini XPS fluorescence plate reader) and protein (42) were pooled. Aliquots were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Derivatized proteins and control proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (19-cm height, 10% acrylamide, 4 °C) and Coomassie-stained. This long gel allowed the resolution of derivatized and underivatized Vam7p.

To assay SNARE complex formation, purified recombinant Nyv1p, Vam3p, and MBP-Vti1p, each lacking their transmembrane anchor domain (34), and Vam7p or Vam7p-F5M were mixed at 10 μm each in Buffer A (20 mm HEPES·NaOH, pH 7.4, 10% glycerol, 125 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, and 0.1% Triton X-100) and incubated for 6 h at 4 °C. SNARE complex reactions with either Vam7p or Vam7p-F5M were added to amylose beads (100 μl) equilibrated in soluble SNARE buffer SSB (20 mm HEPES·NaOH, pH 7.4, 10% glycerol, 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100) and mixed on a rocking table overnight at 4 °C. Beads were suspended three times in 1 ml of radioimmune precipitation buffer (25 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% SDS) and collected by centrifugation (8000 rpm, 2 min, 4 °C). Bound proteins were eluted with 2% SDS sample buffer at room temperature. Eluates were analyzed by immunoblot.

Proteoliposomes

Reconstituted proteoliposomes of mixed sizes were prepared for binding assays as described (12) from a mixture of lipids that mimic the vacuolar composition. Lipid stocks (2 μmol), stored under argon at −80 °C in chloroform, were warmed to room temperature and transferred with glass micropipettes into glass vials with Teflon-lined caps. Specific lipid compositions are indicated in Table 1. Lipid mixtures were swirled and then dried under a stream of nitrogen at room temperature and SpeedVac-dried for 2 h. Dried lipid films were covered with parafilm and placed on ice. Buffer A (0.5 ml of 150 mm NaCl, 20 mm HEPES·NaOH, pH 7.4, 10% glycerol) with 40 mm β-octyl glucoside was added to each vial of dried lipids and then gently vortexed until all of the lipids were in suspension. Vials were placed on ice between vortex mixings to maintain a temperature of ∼4 °C. Purified Ypt7p in β-octyl glucoside was added to a 1:2000 protein/lipid molar ratio, with a final concentration of 2 mm lipids in 1 ml of solution. When SNAREs were included, they were added at a molar ratio of 1:1000 SNARE protein/lipid, and the final concentration of the detergent was kept at a minimum of 30 mm. Following the addition of proteins, the vials were incubated at 4 °C with gentle mixing for 2 h. Mixed micellar solutions (1 ml) were transferred to 20,000 molecular weight cut-off dialysis cassettes (Slide-A-Lyzer, Pierce) using syringes and needles and then dialyzed against three 1-liter portions of Buffer A at 4 °C for 3 h, overnight, and 3 h. In some preparations, a single dialysis solution was used with 1 g of BioBeads SM-2 (Bio-Rad). Proteoliposomes were harvested from the cassettes, transferred to ultracentrifuge tubes on ice, and mixed with an equal volume of 80% Histodenz in Buffer A. This was overlaid with 30% Histodenz in Buffer A and then with a small volume of Buffer A. After centrifugation (55,000 rpm, Beckman SW60Ti, 4 °C, 1 h), proteoliposomes at the transition between 30% Histodenz and Buffer A were harvested with a micropipette, portioned into small aliquots, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C.

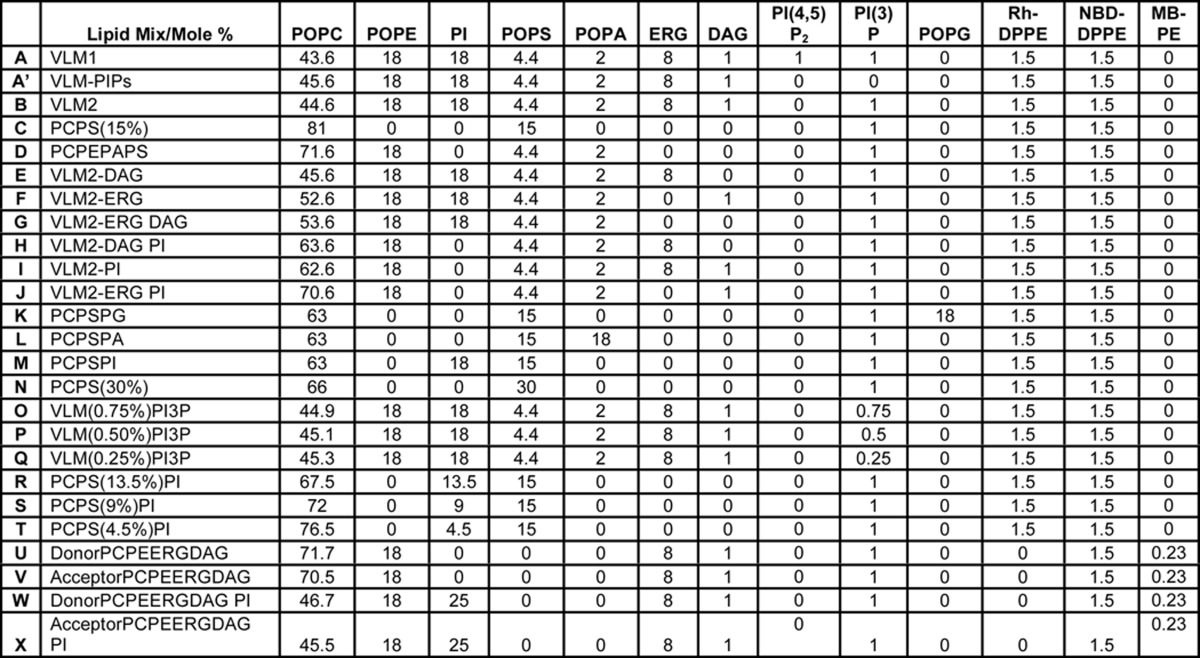

TABLE 1.

Detailed lipid compositions of proteoliposomes used in this study

Specific lipid compositions, in mol % lipid, of reconstituted proteoliposomes used in this study are presented. Lipid mixes are labeled using letters and recalled in the text as such. A minus sign in the described name of a lipid mix signifies deletion of the lipid or lipids identified after it. POPC, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine; POPE, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylethanolamine; POPS, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidyl-l-serine; POPA, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidic acid; ERG, ergosterol; DAG, diacylglycerol; POPG, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylglycerol; DPPE, dipalmitoyl-phosphatidylethanolamine.

Fluorescent lipids (NBD-PE, Rh-PE, and dansyl-PE) were from Molecular Probes. Non- fluorescent lipids were from Avanti Polar Lipids except that ergosterol was from Sigma, and phosphoinositides were from Echelon. Lipid concentrations were determined using lipid phosphate assays (35). When Ypt7p was omitted from proteoliposomes, an equal volume of Ypt7p buffer was added to the lipid/protein/detergent mixture before dialysis.

Binding Analysis

Sedimentation assays were performed to examine the associations of Vam7p. Mixtures containing 2.5 nm Vam7p, 10 nm HOPS, and 200 μm proteoliposomal lipid in buffer (150 mm NaCl, 20 mm HEPES·NaOH, pH 7.4, 10% glycerol, 2 mg/ml fatty acid-free BSA) were prepared at 4 °C. Aliquots (45 μl) were overlaid with 90 μl of light paraffin oil (Fisher, catalog no. O1211) and centrifuged at 50,000 rpm in a TLS55 rotor in a Beckman Optima TLX tabletop ultracentrifuge (4 °C, 10 min). The top 35 μl of the aqueous phase was harvested from each tube, mixed with 5× SDS sample buffer, and analyzed on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel and immunoblotted for Vam7p and HOPS. HOPS was assayed with an antibody to the subunit Vps11p. Error bars in each figure indicate the S.D. values for at least three replicate experiments.

RESULTS

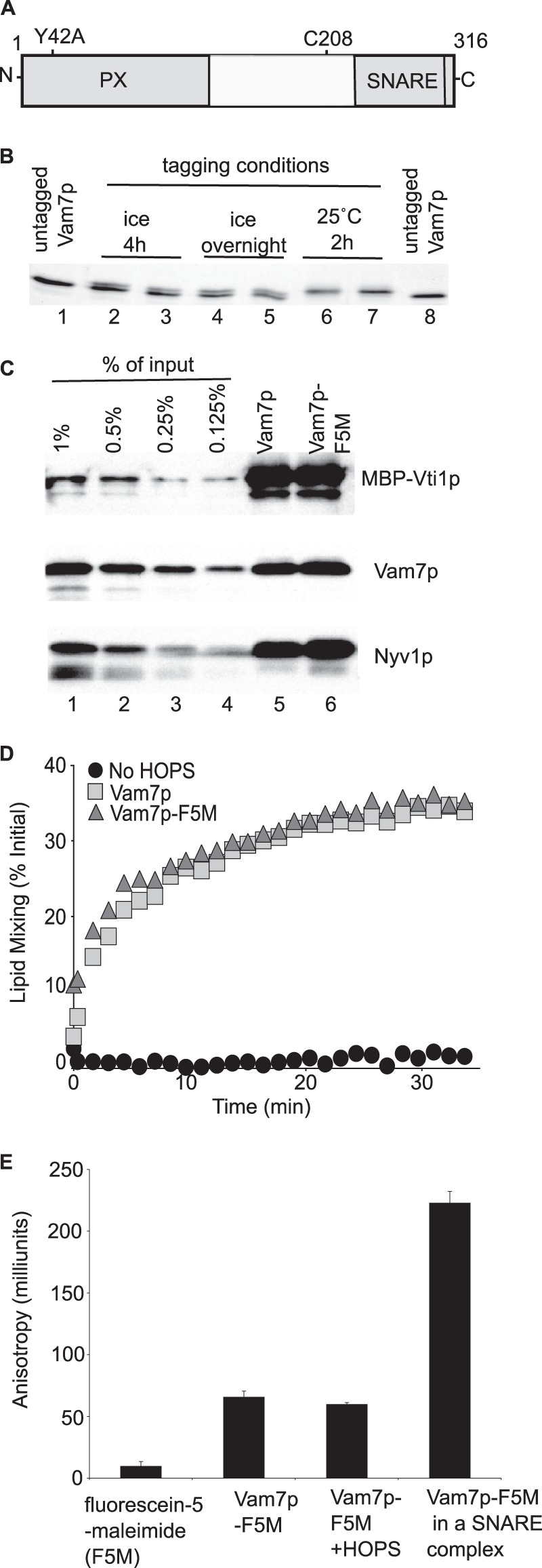

Vam7p was derivatized with fluorescein 5-maleimide at its unique cysteine (Fig. 1A) to study its interactions by measuring changes in fluorescence anisotropy. A nearly complete derivatization of Vam7p with fluorescein-5-maleimide (F5M) was achieved by incubating the protein with F5M for 4 h at 25 °C (Fig. 1B, lanes 6 and 7). We tested whether derivatized Vam7p-F5M had preserved its important functional activities. Vam7p enters into a SNARE complex in vitro with the other vacuolar SNAREs: two Q-SNAREs (Vti1p and Vam3p) and one R-SNARE (Nyv1p) (36). We judged the efficiency of Vam7p and Vam7p-F5M assembly into complexes with the other vacuolar SNAREs using an in vitro pull-down assay. Vam7p-F5M was comparable with underivatized Vam7p in its ability to enter into 4-SNARE complexes (Fig. 1C, lanes 5 and 6). Recruitment of Vam7p into a 4-SNARE complex on membranes leads to lipid mixing, which can be monitored in an in vitro reconstituted lipid mixing fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) assay (12, 36, 37). We compared the activity of Vam7p-F5M to underivatized Vam7p in this assay (Fig. 1D). Vam7p-F5M showed activity that was comparable with that of underivatized Vam7p.

FIGURE 1.

A fluorescence anisotropy assay of Vam7p complex formation. A, Vam7p has two major domains, a SNARE domain and a PX domain, which binds PI(3)P (20) and HOPS (26). The locations of the unique cysteine at position 208 and of the point mutation Y42A are identified. B, derivatizing Vam7p with fluorescein 5-maleimide (F5M). See “Experimental Procedures.” C, comparable incorporation of Vam7p and Vam7p-F5M into 4-SNARE complexes. See “Experimental Procedures.” D, the fusion activity of Vam7p-F5M. Proteoliposomes were prepared with vacuolar lipids and SNAREs (see “Experimental Procedures”) (41). Lipid mixing assays contained fluorescent donor 1R-SNARE proteoliposomes (50 μm lipids) and 2Q-SNARE acceptor proteoliposomes (400 μm lipids), 1 mm ATP, 1 mm MgCl2, 1.2 μm Sec17p, 1.4 μm Sec18p, 50 nm HOPS, and 2 mg/ml BSA. Reaction mixtures (15 μl) were prepared on ice and preincubated for 10 min at 27 °C in 384-well Corning black plates in a SpectraMAX Gemini XPS plate reader. Vam7p or Vam7p-F5M (6.25 nm) was added where indicated. NBD fluorescence (λex = 460 nm; λem = 538 nm; emission cut-off λ, 515 nm) was measured immediately after mixing at 1-min intervals on the “high” PMT setting (arbitrary units). At the end of the assay, 100 mm β-octyl glucoside was added to each well to fully dequench NBD fluorescence. Maximal NBD fluorescence (%) is calculated as (F − F0)/Fmax, where F0 is the average of signals at 0 min and Fmax is an average of signals after detergent addition. E, Vam7p-F5M incorporated in the SNARE complex shows an increased anisotropy, whereas Vam7p-F5M incubated with HOPS does not. SNARE complexes formed as in Fig. 1C and eluted from amylose beads in Buffer B (300 mm NaCl, 20 mm HEPES·NaOH, pH 7.4, 10% glycerol, 10 mm maltose) were used to assay binding of Vam7p in a complex. Reactions had 62.5 nm free F5M, 62.5 nm Vam7p-F5M, and 125 nm HOPS in black 96-well HE microplates (Molecular Devices). Fluorescence anisotropy was recorded at 25 °C in a Tecan Infinite M1000 fluorimeter at a gain setting of 37, calculated G-factor of ∼0.8, λex = 470 nm and λem = 525 nm, settle time of 300 ms, and z-position of 24,819 μm. Error bars, S.D.

Vam7p-F5M showed an increase in fluorescence anisotropy when compared with fluorescein 5-maleimide alone (Fig. 1E). Vam7p-F5M incorporated in a 4-SNARE complex shows an ∼4-fold further increase in anisotropy (Fig. 1E). However, the addition of HOPS to Vam7p-F5M did not enhance its anisotropy (Fig. 1E). This was unexpected, because HOPS is a large (632 kDa) tethering complex that has been shown to have a direct affinity for Vam7p (26).

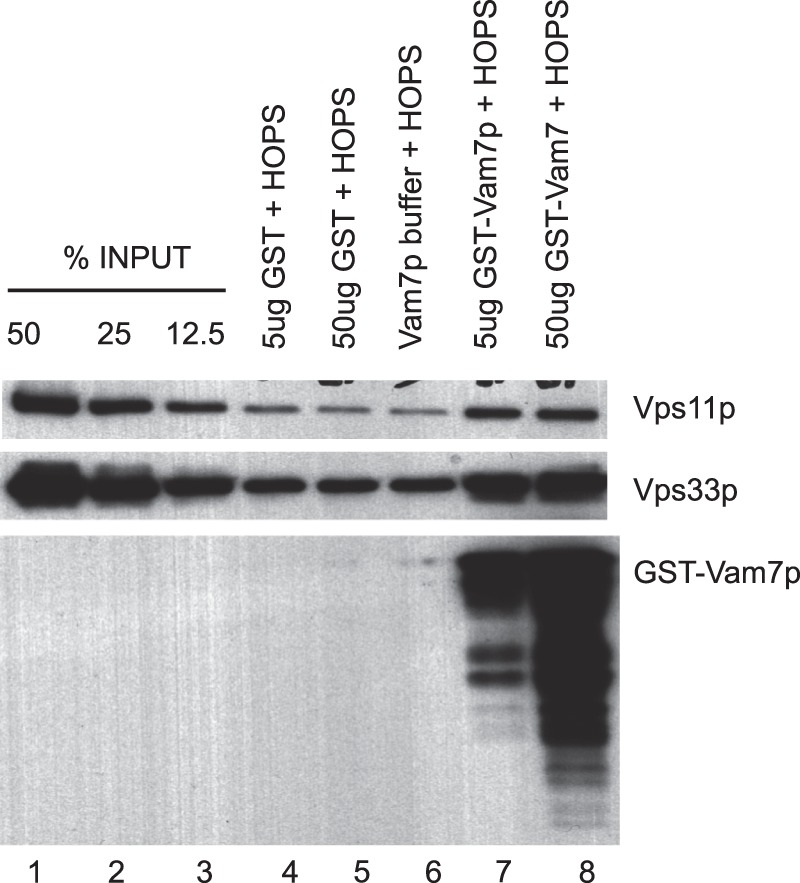

Purified HOPS has been reported to bind to GST-tagged Vam7p when the GST-Vam7p was itself bound to glutathione-Sepharose 4B (26). Although we also observe that more HOPS associates with glutathione-Sepharose-4B beads when they bear GST-Vam7p (Fig. 2, lanes 4–6 versus lanes 7 and 8), the beads-only controls also showed considerable background HOPS binding (Fig. 2, lanes 4–6). This suggests that HOPS may bind through the product of its modest affinities for Vam7p and for the resin. In an in vitro fusion environment, the multiplicative affinities of other membrane factors, including lipids, may fulfill the binding function of the glutathione beads in this study. A modest affinity of Vam7p for HOPS could underlie the observed lack of increase in anisotropy (Fig. 1E). However, the simple addition of reconstituted proteoliposomes to anisotropy assays was not practical for measurements of high affinity Vam7p binding, because the liposomes distorted the fluorescence signal by light scattering (not shown). We therefore turned to sedimentation analysis to evaluate the associations of Vam7p with HOPS and other membrane factors.

FIGURE 2.

HOPS binds to glutathione beads as well as to Vam7p. Glutathione-Sepharose-4B beads (15 μl of beads/reaction) were washed three times in 1 ml of Buffer C (100 mm NaCl, 20 mm HEPES·NaOH, pH 7.4, 2 mm EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 20% glycerol, 1 mm DTT) at 4 °C by sedimentation (2000 rpm, 4 °C, 2 min; microcentrifuge) and then suspended in 500 μl of this buffer. Purified GST-Vam7p or GST (5 μg or 50 μg of each, in 5 μl in 20 mm HEPES·NaOH, pH 7.4, 300 mm NaCl) was added and incubated with beads at 4 °C for 1 h. HOPS (4 nm) was added, and incubation continued for another 1 h at 4 °C. Following washes in Buffer B at 4 °C by sedimentation (2000 rpm, 4 °C, 2 min each; microcentrifuge), bound proteins were eluted (2% SDS, 100 μl) at 90 °C for 15 min. Portions (20 μl) of the eluates were analyzed on an SDS-12% polyacrylamide gel followed by immunoblotting (26) for HOPS subunits Vps11p and Vps33p and for GST-Vam7p.

Binding Analysis by Sedimentation

Recombinant Vam7p was mixed with HOPS and proteoliposomes bearing Ypt7p and vacuolar lipids (composition A, Table 1), including the phosphoinositides PI(3)P and PI(4,5)P2. Proteoliposomes prepared in this manner were of mixed sizes, averaging from 120 to 170 nm in diameter (12, 38). The suspension was centrifuged, and the supernatant solution was assayed for remaining Vam7p and HOPS by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot. Vam7p is a monomeric, soluble 37-kDa protein; in the absence of other potential binding partners, almost all of the Vam7p (Fig. 3, A and B, lane 1) and ∼70% of the HOPS (lane 2) was recovered in the supernatant. In contrast, this centrifugation removed 95% of the proteoliposomal lipid (Fig. 3C). Vam7p only sediments rapidly when it associates with HOPS and/or proteoliposomes. During sedimentation, proteoliposome-bound Vam7p is therefore in the constant presence of the same concentration of free Vam7p as in the starting mixture. The Vam7p that remains in the supernatant after centrifugation is thus a faithful reflection of the initial partition of Vam7p into that which is bound to HOPS and proteoliposomes and that which remains free.

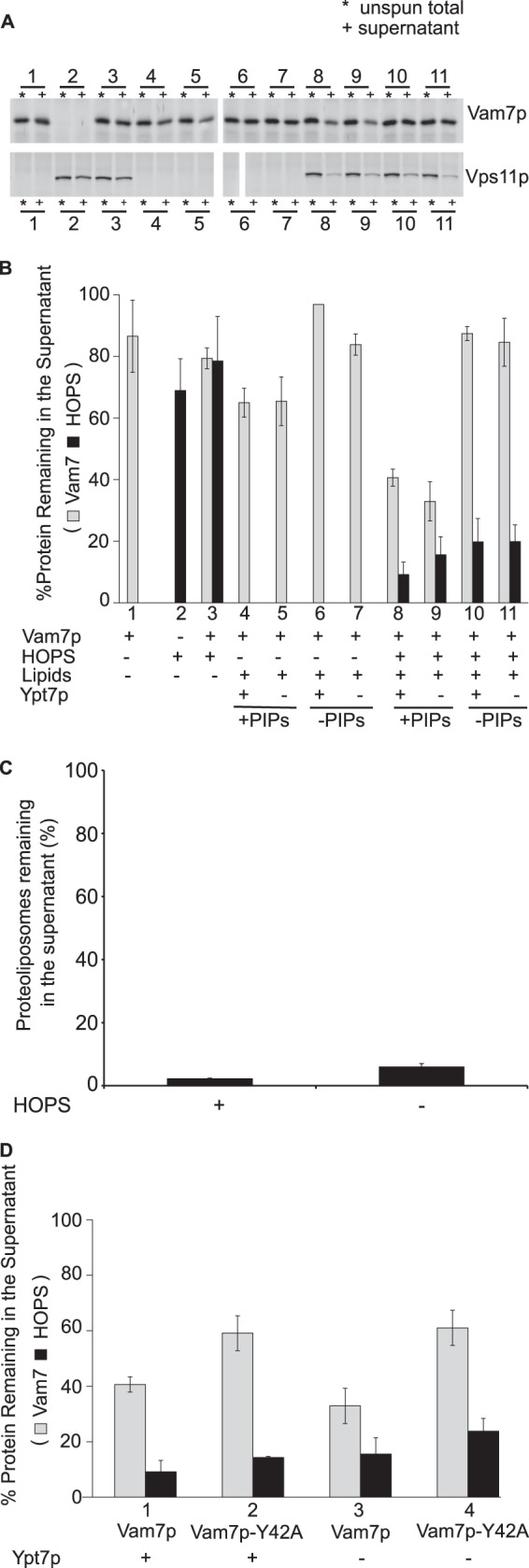

FIGURE 3.

HOPS and phosphoinositides are required for stable membrane association of Vam7p. A, sedimentation assays were performed with proteoliposomes (composition A, Table 1) bearing different combinations of HOPS and Ypt7p, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Where indicated, both phosphoinositides were omitted, and the PC was increased by 2%. Maximal Vam7p sedimentation depends on the presence of HOPS and phosphoinositides but not Ypt7. B, means and S.D. values are shown for triplicate experiments performed as in A. C, the proteoliposomes are thoroughly removed by sedimentation. Total phosphorus remaining in the supernatant was assayed after proteoliposome sedimentation. D, the requirement for phosphoinositides for Vam7p membrane association is mediated through the Vam7p PX domain and not through HOPS-phosphoinositide interaction. The point mutant Vam7p-Y42A that is incapable of binding to phosphoinositides (20) sediments poorly in comparison with Vam7p. HOPS sedimentation behavior remained the same throughout. Error bars, S.D.

In the presence of HOPS, proteoliposomes of vacuolar lipid composition, which bear phosphoinositides, bind over half of the Vam7p (Fig. 3, A and B, lanes 8 and 9). Optimal binding requires HOPS (lanes 4 and 5, no HOPS) and phosphoinositides (lanes 10 and 11, no phosphoinositides). Mutation of the Vam7p tyrosine at residue 42 to alanine, which has been shown to abolish the affinity of Vam7p for phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate (20), diminishes Vam7p clearance (Fig. 3D). HOPS and Ypt7p do not simply function by enhancing the sedimentation of proteoliposomes, because almost all of the proteoliposomes sediment in the absence of HOPS (Fig. 3C). Ypt7p is not essential for HOPS association with membranes (Fig. 3, A and B, lane 8 versus lane 9), as noted previously (12, 39). We conclude that phosphoinositides and HOPS, each with a direct affinity for Vam7p (20, 26), are central to the recruitment of Vam7p to the membrane. Although PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3)P have both been reported to stimulate fusion (40), PI(4,5)P2 does not stimulate the association of Vam7p with membranes (Fig. 4). Vam7p depends on only PI(3)P, and recognition of this phosphoinositide depends on the Vam7p PX domain (Fig. 3D).

FIGURE 4.

PI(4,5)P2 is not needed for Vam7p membrane recruitment. Sedimentation assays comparing proteoliposomes made with PI(3)P and with or without PI(4,5)P2 (composition A or B, Table 1) show indistinguishable Vam7p sedimentation. Error bars, S.D.

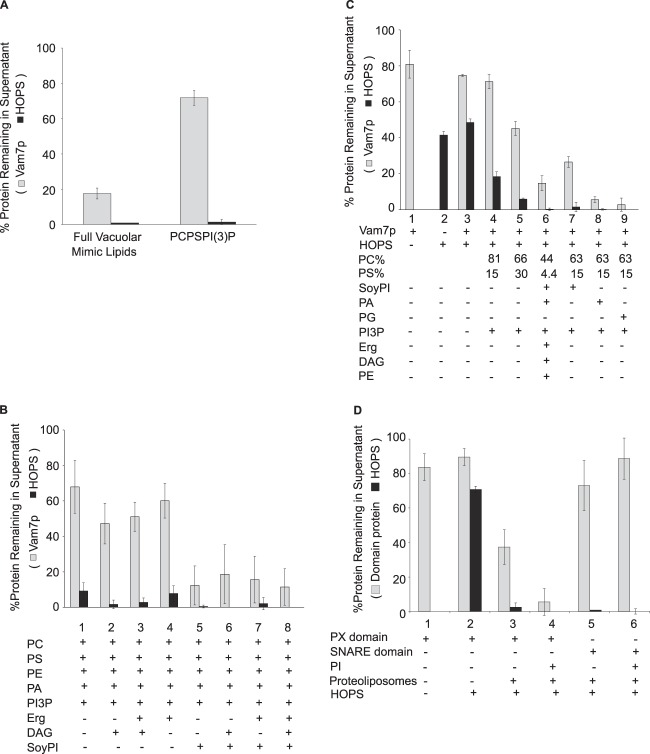

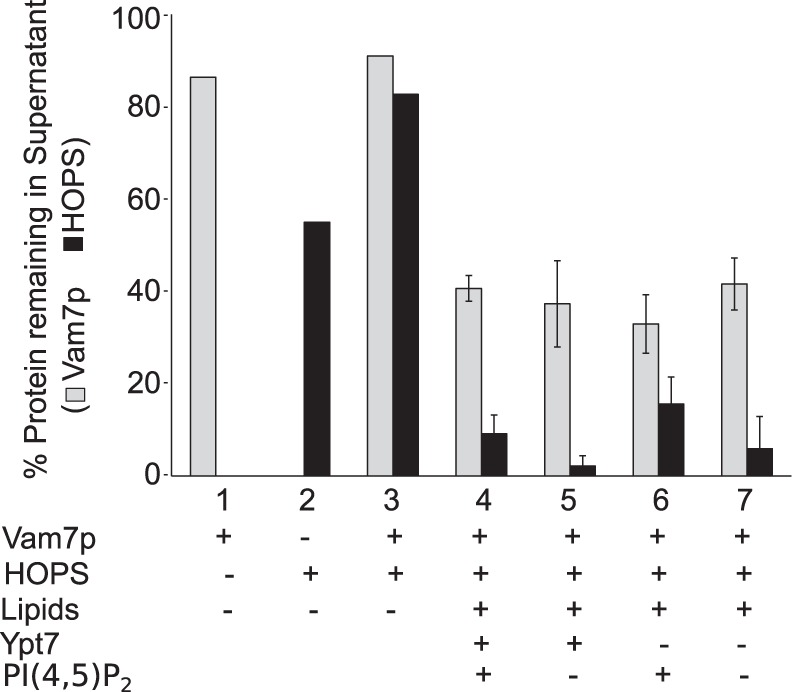

PI(3)P is not the only lipid contributing to Vam7p membrane association. Vam7p will bind to proteoliposomes of a full vacuolar lipid mixture, but Vam7p will not bind to proteoliposomes of PC/PS and PI(3)P (Fig. 5A) or even of PC, PE, PA, PS, ergosterol, and PI(3)P (Fig. 5B, lane 4), although these proteoliposomes bear Ypt7p and bind HOPS. Supplementation with the acidic lipid PI restores full Vam7p binding (Fig. 5B, lanes 5–8) independent of the presence or absence of diacylglycerol and ergosterol. This reflects a need for an acidic lipid rather than a specific requirement for PI, because substitution of PG or PA for PI still allows full Vam7p binding; PC/PS proteoliposomes without PI yield little Vam7p clearance (Fig. 5C, lane 3), whereas the addition of just PI, PA, or PG yields substantial Vam7p clearance (lanes 7–9), comparable with that seen with the full vacuolar mix (lane 6). PS, although acidic, contributes little to Vam7p membrane binding, because even 30% PS (lane 5) is not as effective as PI, PA, or PG (lanes 7–9). Acidic lipid is not required for HOPS association with proteoliposomes, because simply PC/PS proteoliposomes bearing Ypt7p bind HOPS efficiently (Fig. 5A), suggesting that the acidic lipids either activate the bound HOPS for Vam7p binding or contribute directly to Vam7p membrane association. Recombinant PX domain of Vam7p depends on acidic lipids for its high affinity binding to proteoliposomes (Fig. 5D, lane 3 versus lane 4), whereas the SNARE domain does not exhibit high affinity binding (lanes 5 and 6). Thus, Vam7p membrane association requires interactions with acidic lipid, HOPS, and PI(3)P, reflecting the product of its affinities for more than one membrane element. Each of these three components were present at limiting concentrations in our binding assays, because reduction in their concentrations (Fig. 6) caused proportional reduction in Vam7p binding to the proteoliposomes.

FIGURE 5.

Lipids with major roles in Vam7p membrane interactions. A, sedimentation assays showed that HOPS and Ypt7p proteoliposomes with a full complement of vacuolar lipids (B in Table 1) bind Vam7p, but those of a PC/PS/PI(3)P minimal lipid mixture (C in Table 1) do not. B, proteoliposomes bearing Ypt7p were made with the indicated lipids. Proteoliposomes of PC/PE/PA/PS/PI(3)P (lane 1; composition D, Table 1) fail to sediment Vam7p. The further addition of one acidic lipid, PI, to this mix (lane 5; composition G, Table 1) restores binding and sedimentation of Vam7p to levels supported by the full vacuolar mix (lane 8; composition B). Proteoliposomes in lanes 1–8 have compositions D, J, I, H, G, F, E, and B from Table 1, respectively. C, any of several acidic lipids will promote the membrane association of Vam7p. Reconstituted proteoliposomes with Ypt7p and varying acidic lipid contents were prepared as described under “Experimental Procedures” but without Histodenz flotation (to avoid aggregation) and were assayed as described for binding of HOPS and Vam7p. Each lipid, when present (indicated by a plus sign) was at its molar percentage in the vacuolar lipid mix (lane 6 shows the vacuolar lipid mix), with compensatory variation of the percentage of PC. Proteoliposomes used in lanes 4–9 had compositions C, N, B, M, L, and R in Table 1, respectively. Erg, ergosterol; DAG, diacylglycerol. D, the PX domain of Vam7p mediates the effect of acidic lipids on Vam7p sedimentation. Reconstituted proteoliposomes with, or without, PI were prepared as in C and mixed with purified recombinant Vam7p domains prior to sedimentation. GST-tagged PX and SNARE domains were isolated as described (38). Each construct included a thrombin cleavage site between the tag and the protein domain. GST tags were cleaved with a 1:2 molar ratio of enzyme to substrate in 300 mm NaCl, 20 mm HEPES·NaOH, pH 7.4, 10% glycerol by incubation at room temperature for 30 min. Protease cleavage was stopped by the addition of 5 mm PMSF. The extent of protease cleavage and the recovery of cleaved product were verified by SDS-PAGE analysis (not shown). Completely cleaved protein domains were used for sedimentation analysis. Lanes 1 and 2, no proteoliposomes. The proteoliposomes in lanes 3 and 5 had composition C (Table 1), and those in lanes 4 and 6 had composition M. Error bars, S.D.

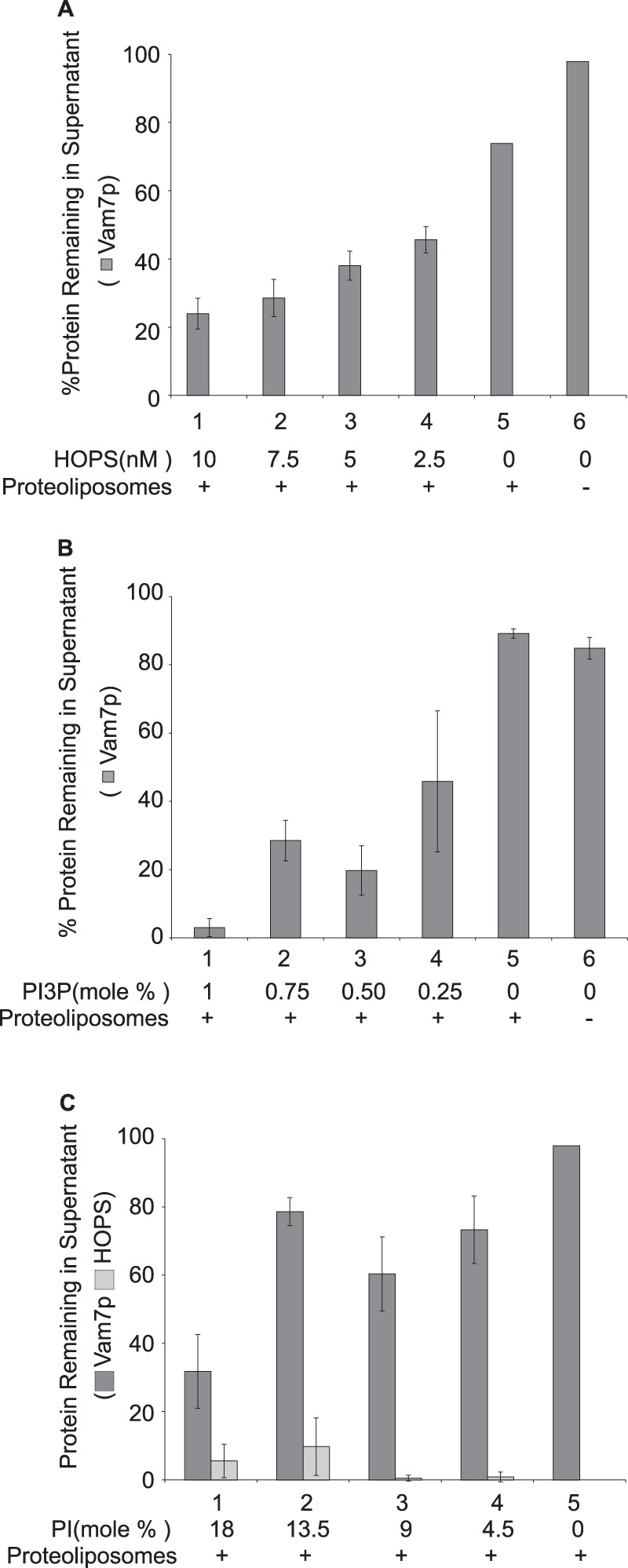

FIGURE 6.

The concentrations of HOPS, PI(3)P, and PI that are needed for Vam7p association with proteoliposomes. A, reactions bear reconstituted proteoliposomes (lanes 1–5; composition A, Table 1). Decreasing HOPS within the reaction has a direct effect on the sedimentation of Vam7p. B, reconstituted proteoliposomes were prepared with the indicated molar percentages of PI(3)P (lanes 1–5; compositions A, O, P, Q, and A′, Table 1). The sedimentation of Vam7p in the presence of HOPS and reconstituted proteoliposomes bearing no PI(3)P (lane 5) is comparable with the sedimentation of Vam7p alone (lane 6). C, reconstituted proteoliposomes were made with the indicated molar percentages of PI (lanes 1–4; compositions M, R, S, and T, Table 1). Error bars, S.D.

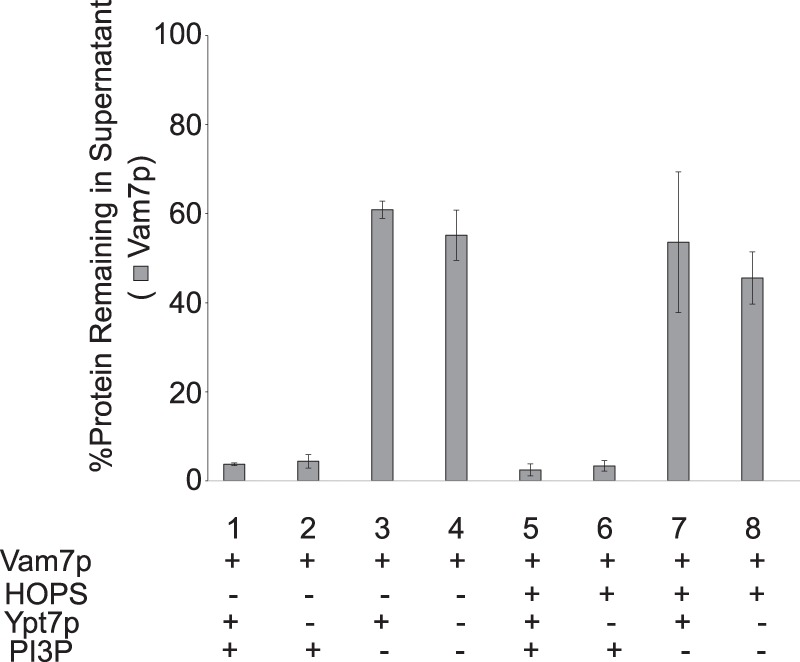

The four vacuolar SNAREs can spontaneously but slowly assemble into 4-helical complexes (12, 28, 36). When proteoliposomes were prepared with a vacuolar lipid mixture and the other three vacuolar SNAREs, the membrane binding of Vam7p required PI(3)P but not HOPS or Ypt7p (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 7.

Vam7p membrane recruitment in the presence of SNAREs only requires PI(3)P. Sedimentation assays were performed with proteoliposomes bearing the full vacuolar complement of lipids without PI(4,5)P2 (composition B, Table 1) and the three transmembrane SNAREs Vam3p, Vti1p, and Nyv1p. In reaction mixtures where HOPS was included, it sedimented to completion (data not shown). Error bars, S.D.

Acidic Lipids Promote Efficient Participation of Vam7p in Fusion

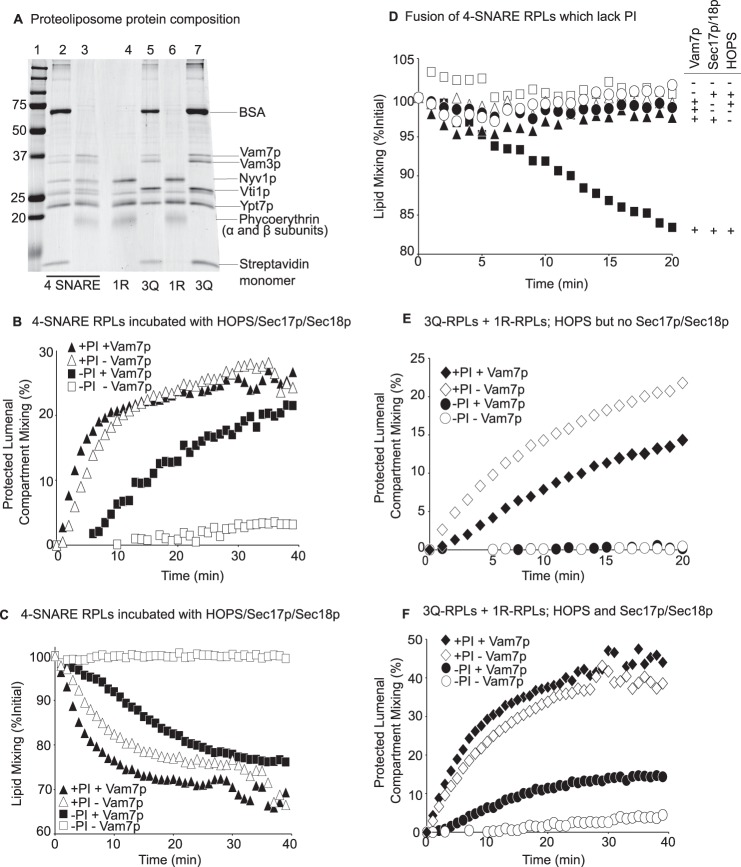

The multiplicity of acidic lipids and their ubiquitous distribution make it impractical to measure their physiological role in Vam7p membrane association in vivo or with isolated vacuoles. However, vacuolar fusion has been reconstituted with defined lipids and a physiological set of all purified recombinant vacuolar proteins (12, 13). Although the vacuole bears several acidic lipids, a recent study3 has shown that a single acidic lipid, phosphatidylinositol, can suffice for fusion. We therefore prepared proteoliposomes (38) using a mixture of PC, PE, diacylglycerol, and ergosterol, either with PI as its sole acidic lipid (compositions W and X, Table 1) or without PI or any other acidic lipid (compositions U and V). These proteoliposomes, prepared by dialysis of detergent mixed micelles, bore the vacuolar Rab GTPase Ypt7p, the four vacuolar SNAREs, and either of two fluorescent lipids, Marina Blue-PE or NBD-PE. A colloidal Coomassie-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel of these proteoliposomes, prepared with or without PI (Fig. 8A, lanes 4 and 5, without PI; lanes 6 and 7, with PI), showed that PI had no effect on the reconstituted protein composition. In addition, either biotinylated phycoerythrin or Cy5-derivatized streptavidin was added to the initial detergent mixed micellar solutions, allowing their entrapment during proteoliposome formation. Proteoliposomes were separated from unincorporated components by flotation. As described (38), lumenal compartment mixing during fusion allows the biotin-phycoerythrin to bind to Cy5-streptavidin, which can be assayed by the resulting FRET. This assay was performed with a large molar excess of external nonfluorescent streptavidin to block any association between leaked fluorescent proteins. At the same time, lipid mixing places rhodamine-PE in the same membrane as Marina Blue-PE, allowing the fluorescence of the Marina Blue to be quenched. Each of these FRET signals was measured simultaneously in a plate-reading fluorimeter.

FIGURE 8.

A high concentration of Vam7p (4 μm) partially bypasses the requirement for acidic lipids when the proteoliposomal SNAREs are disassembled to allow new SNARE complex formation. A, colloidal Coomassie-SDS-PAGE analysis of reconstituted proteoliposomes, prepared as described (38) except with the indicated (compositions U–X, Table 1) lipid compositions and with each SNARE at molar ratios to lipids of 1:5000. Lane 1, molecular weight marker proteins; lanes 2 and 3, 4-SNARE/Ypt7p proteoliposomes with compositions W and X (Table 1). Lanes 4–7, 3Q proteoliposomes (lane 5, lipid composition V; lane 7, lipid composition X) and 1R proteoliposomes (lane 4, lipid composition U; lane 6, lipid composition W). B, fusion, assayed as protected lumenal compartment mixing, for Ypt7p/4-SNARE proteoliposomes that either have PI (triangles) or lack acidic lipids (squares). Fusion incubations (38) had 111 nm Sec17p, 557 nm Sec18p, and 127 nm HOPS. Half of the fusion reactions received 4 μm Vam7p (filled symbols), and the others received the corresponding buffer (open symbols). In each panel, each data point is the average from three replicate experiments; S.D. values were all less than 10%. C, lipid mixing in the very same four reactions. The quenching of Marina Blue-PE fluorescence by NBD-PE was assayed as described (38). D, fusion reactions bearing 4 μm Vam7p were performed as described (38) with 4-SNARE/Ypt7p proteoliposomes prepared without PI and assayed by lipid mixing. The complete reaction (filled squares) had 4 μm Vam7p as well as HOPS, Sec17p, and Sec18p; where indicated, there was omission of the added Vam7p (open squares), of HOPS (filled triangles), of Sec17p and Sec18p (open triangles), or of HOPS and Sec17p/Sec18p (filled circles). E, 3Q and 1R proteoliposome fusion in the presence of added 127 nm HOPS, but without Sec17 or Sec18p, was assayed by protected lumenal content mixing; proteoliposomes either had PI (diamonds) or no acidic lipids (ovals). Half of the fusion reactions received 4 μm Vam7p (filled symbols), and the others received the corresponding buffer (open symbols). F, as in E but in the presence of Sec17p and Sec18p.

These Ypt7p/4-SNARE proteoliposomes introduce a 0.12 μm concentration of each SNARE into our standard assay incubations. In the presence of HOPS, Sec17p, and Sec18p, proteoliposomes bearing PI underwent rapid lumenal compartment mixing, which does not require additional Vam7p (Fig. 8B, triangles). Although fusion was abolished by the omission of PI from the proteoliposomes (open squares), there was a partial restoration of fusion by the addition of 4 μm Vam7p (filled squares). In these same reactions, lipid mixing did not require additional Vam7p when PI was present (Fig. 8C, triangles), but lipid mixing in the absence of PI was partially restored by the addition of 4 μm Vam7p (squares). The fusion that was restored to PI-free proteoliposomes by this high level of Vam7p still required HOPS and Sec17p/Sec18p (Fig. 8D), showing that it employed the authentic reaction catalysts.

Does Vam7p also stimulate fusion when SNARE complexes are preformed, precluding Vam7p participation in the formation of additional SNARE complexes? Proteoliposomes were prepared with Ypt7p and with or without PI as above but bearing either the R-SNARE Nyv1p alone or bearing the 3Q-SNAREs in preformed complex (36). After Ypt7p/HOPS-mediated tethering, these proteoliposomes, which do not require Sec17p/Sec18p-catalyzed cis-SNARE complex disassembly for their R-SNARE and three Q-SNAREs to pair in trans and mediate fusion (12), showed no fusion in the absence of PI and no stimulation of fusion by added Vam7p (Fig. 8E). Fusion remained dependent on PI when these proteoliposomes were incubated with Sec17p and Sec18p in addition to HOPS (Fig. 8F), but the addition of high concentrations of Vam7p drove a partial restoration of fusion (open versus filled ovals), as seen with 4-SNARE proteoliposomes (Fig. 8B). Although acidic lipids clearly have other important functions for fusion in addition to contributing to Vam7p binding, the partial bypass of the requirement for the acidic lipid PI by a high concentration of Vam7p (4 μm) is only seen when the SNAREs are all disassembled and capable of de novo complex formation. Thus, acidic lipids and disassembled SNAREs are required for low levels of Vam7p (0.025 μm) to participate in SNARE complex formation for fusion, and the capacity of high levels of Vam7p (4 μm) to partially bypass the acidic lipid requirement is in full accord with a role of acidic lipid in functional Vam7p membrane association.

DISCUSSION

Prior to fusion, SNAREs and other fusion proteins and lipids become highly enriched in a “vertex” ring-shaped microdomain, which surrounds the apposed membranes of docked vacuoles. Vam7p, lacking an apolar membrane anchor domain, relies on its affinities for HOPS, PI(3)P, and SNAREs, which are each vertex-enriched, for its membrane association. Our current findings, with purified proteins and lipids, are in full accord with earlier studies, but the chemical definition inherent in a reconstituted system has allowed us to discover a novel role for acidic lipid, which could not have been detected in studies in vivo or with the isolated organelle. The PX domain of Vam7p has been shown to be required for the in vivo vacuolar association of this SNARE (20). Our results suggest that the affinity of Vam7p for PI(3)P, although necessary for its membrane binding, is not sufficient. In accord with this, we noted (26) that vacuoles from cells bearing a thermosensitive mutation in the Vps11p subunit of HOPS were inactive for in vitro fusion and that the addition of wild-type HOPS alone was insufficient to restore fusion without the concurrent addition of nanomolar levels of Vam7p. This striking synergy suggests that, in the absence of HOPS function, these vacuoles bore insufficient Vam7p, in agreement with our current findings with reconstituted reactions bearing pure components.

An unexpected finding from our current studies is that acidic lipids are important for Vam7p membrane association (Fig. 5) and that the acidic lipid function in fusion can be partially bypassed by high concentrations of Vam7p (Fig. 8). Among the possible mechanisms for acidic lipid function is a direct association with Vam7p, an allosteric effect on membrane-bound HOPS that might enhance its affinity for Vam7p, or an effect of acidic lipids on the distribution or properties of PI(3)P. If Vam7p directly binds to acidic lipids, substantial further studies will be needed to define the contact aminoacyl residues in Vam7p. Although further studies will be needed to define the precise mechanism, acidic lipids are also required for the membrane affinity of the Vam7p N-terminal targeting domain (Fig. 5D). The exact contributions of HOPS, PI(3)P, and acidic lipids toward the binding of Vam7p are not yet defined. However, with 2.5 nm Vam7p and 10 nm HOPS, proteoliposomes bearing acidic lipids and PI(3)P allow us to reconstitute binding of over half of the Vam7p, suggesting that HOPS that is bound to such membranes has an apparent binding affinity for Vam7p that is in the low nanomolar range.

Acknowledgments

We thank Amy Orr, Deborah Douville, and Holly Jakubowski for expert assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM23377-37.

M. Zick and W. Wickner, manuscript in preparation.

- HOPS

- homotypic fusion and vacuole protein sorting complex

- F5M

- fluorescein-5-maleimide

- PC

- phosphatidylcholine

- PS

- phosphatidylserine

- PE

- phosphatidylethanolamine

- PG

- phosphatidylglycerol

- PI

- phosphatidylinositol

- PA

- phosphatadic acid

- PI(3)P

- phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate

- PI(4,5)P2

- phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- NBD

- 12-(N-methyl-N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)).

REFERENCES

- 1. Haas A., Scheglmann D., Lazar T., Gallwitz D., Wickner W. (1995) The GTPase Ypt7p of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is required on both partner vacuoles for the homotypic fusion step of vacuole inheritance. EMBO J. 14, 5258–5270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Grosshans B. L., Andreeva A., Gangar A., Niessen S., Yates J. R., 3rd, Brennwald P., Novick P. (2006) The yeast lgl family member Sro7p is an effector of the secretory Rab GTPase Sec4p. J. Cell Biol. 172, 55–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Seals D. F., Eitzen G., Margolis N., Wickner W. T., Price A. (2000) A Ypt/Rab effector complex containing the Sec1 homolog Vps33p is required for homotypic vacuole fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 9402–9407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jahn R. (2006) Neuroscience. A neuronal receptor for botulinum toxin. Science 312, 540–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nichols B. J., Ungermann C., Pelham H. R., Wickner W. T., Haas A. (1997) Homotypic vacuolar fusion mediated by t- and v-SNAREs. Nature 387, 199–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ungermann C., Nichols B. J., Pelham H. R., Wickner W. (1998) A vacuolar v-t-SNARE complex, the predominant form in vivo and on isolated vacuoles, is disassembled and activated for docking and fusion. J. Cell Biol. 140, 61–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ungermann C., von Mollard G. F., Jensen O. N., Margolis N., Stevens T. H., Wickner W. (1999) Three v-SNAREs and two t-SNAREs, present in a pentameric cis-SNARE complex on isolated vacuoles, are essential for homotypic fusion. J. Cell Biol. 145, 1435–1442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carr C. M., Grote E., Munson M., Hughson F. M., Novick P. J. (1999) Sec1p binds to SNARE complexes and concentrates at sites of secretion. J. Cell Biol. 146, 333–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Scott B. L., Van Komen J. S., Irshad H., Liu S., Wilson K. A., McNew J. A. (2004) Sec1p directly stimulates SNARE-mediated membrane fusion in vitro. J. Cell Biol. 167, 75–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Söllner T., Whiteheart S. W., Brunner M., Erdjument-Bromage H., Geromanos S., Tempst P., Rothman J. E. (1993) SNAP receptors implicated in vesicle targeting and fusion. Nature 362, 318–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Haas A., Wickner W. (1996) Homotypic vacuole fusion requires Sec17p (yeast α-SNAP) and Sec18p (yeast NSF). EMBO J. 15, 3296–3305 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mima J., Hickey C. M., Xu H., Jun Y., Wickner W. (2008) Reconstituted membrane fusion requires regulatory lipids, SNAREs and synergistic SNARE chaperones. EMBO J. 27, 2031–2042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stroupe C., Hickey C. M., Mima J., Burfeind A. S., Wickner W. (2009) Minimal membrane docking requirements revealed by reconstitution of Rab GTPase-dependent membrane fusion from purified components. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 17626–17633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ohya T., Miaczynska M., Coskun U., Lommer B., Runge A., Drechsel D., Kalaidzidis Y., Zerial M. (2009) Reconstitution of Rab- and SNARE-dependent membrane fusion by synthetic endosomes. Nature 459, 1091–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ma C., Su L., Seven A. B., Xu Y., Rizo J. (2013) Reconstitution of the vital functions of Munc18 and Munc13 in neurotransmitter release. Science 339, 421–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang L., Ungermann C., Wickner W. (2000) The docking of primed vacuoles can be reversibly arrested by excess Sec17p (α-SNAP). J. Biol. Chem. 275, 22862–22867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Haas A., Conradt B., Wickner W. (1994) G-protein ligands inhibit in vitro reactions of vacuole inheritance. J. Cell Biol. 126, 87–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Markgraf D. F., Peplowska K., Ungermann C. (2007) Rab cascades and tethering factors in the endomembrane system. FEBS Lett. 581, 2125–2130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Boeddinghaus C., Merz A. J., Laage R., Ungermann C. (2002) A cycle of Vam7p release from and PtdIns 3-P-dependent rebinding to the yeast vacuole is required for homotypic vacuole fusion. J. Cell Biol. 157, 79–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cheever M. L., Sato T. K., de Beer T., Kutateladze T. G., Emr S. D., Overduin M. (2001) Phox domain interaction with PtdIns(3)P targets the Vam7 t-SNARE to vacuole membranes. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 613–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mayer A., Scheglmann D., Dove S., Glatz A., Wickner W., Haas A. (2000) Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate regulates two steps of homotypic vacuole fusion. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 807–817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kato M., Wickner W. (2001) Ergosterol is required for the Sec18/ATP-dependent priming step of homotypic vacuole fusion. EMBO J. 20, 4035–4040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jun Y., Fratti R. A., Wickner W. (2004) Diacylglycerol and its formation by phospholipase C regulate Rab- and SNARE-dependent yeast vacuole fusion. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 53186–53195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fratti R. A., Jun Y., Merz A. J., Margolis N., Wickner W. (2004) Interdependent assembly of specific regulatory lipids and membrane fusion proteins into the vertex ring domain of docked vacuoles. J. Cell Biol. 167, 1087–1098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fasshauer D., Sutton R. B., Brunger A. T., Jahn R. (1998) Conserved structural features of the synaptic fusion complex. SNARE proteins reclassified as Q- and R-SNAREs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 15781–15786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stroupe C., Collins K. M., Fratti R. A., Wickner W. (2006) Purification of active HOPS complex reveals its affinities for phosphoinositides and the SNARE Vam7p. EMBO J. 25, 1579–1589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ungermann C., Wickner W. (1998) Vam7p, a vacuolar SNAP-25 homolog, is required for SNARE complex integrity and vacuole docking and fusion. EMBO J. 17, 3269–3276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hickey C. M., Wickner W. (2010) HOPS initiates vacuole docking by tethering membranes before trans-SNARE complex assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 2297–2305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fratti R. A., Collins K. M., Hickey C. M., Wickner W. (2007) Stringent 3Q.1R composition of the SNARE 0-layer can be bypassed for fusion by compensatory SNARE mutation or by lipid bilayer modification. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 14861–14867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Merz A. J., Wickner W. T. (2004) Trans-SNARE interactions elicit Ca2+ efflux from the yeast vacuole lumen. J. Cell Biol. 164, 195–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Eitzen G., Will E., Gallwitz D., Haas A., Wickner W. (2000) Sequential action of two GTPases to promote vacuole docking and fusion. EMBO J. 19, 6713–6720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thorngren N., Collins K. M., Fratti R. A., Wickner W., Merz A. J. (2004) A soluble SNARE drives rapid docking, bypassing ATP and Sec17/18p for vacuole fusion. EMBO J. 23, 2765–2776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tsukamoto Y., Wakil S. J. (1988) Isolation and mapping of the β-hydroxyacyl dehydratase activity of chicken liver fatty acid synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 16225–16229 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jun Y., Thorngren N., Starai V. J., Fratti R. A., Collins K., Wickner W. (2006) Reversible, cooperative reactions of yeast vacuole docking. EMBO J. 25, 5260–5269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rouser G., Fkeischer S., Yamamoto A. (1970) Two dimensional thin layer chromatographic separation of polar lipids and determination of phospholipids by phosphorus analysis of spots. Lipids 5, 494–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fukuda R., McNew J. A., Weber T., Parlati F., Engel T., Nickel W., Rothman J. E., Söllner T. H. (2000) Functional architecture of an intracellular membrane t-SNARE. Nature 407, 198–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Struck D. K., Hoekstra D., Pagano R. E. (1981) Use of resonance energy transfer to monitor membrane fusion. Biochemistry 20, 4093–4099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zucchi P. C., Zick M. (2011) Membrane fusion catalyzed by a Rab, SNAREs, and SNARE chaperones is accompanied by enhanced permeability to small molecules and by lysis. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 4635–4646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hickey C. M., Stroupe C., Wickner W. (2009) The major role of the Rab Ypt7p in vacuole fusion is supporting HOPS membrane association. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 16118–16125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mima J., Wickner W. (2009) Complex lipid requirements for SNARE- and SNARE chaperone-dependent membrane fusion. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 27114–27122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mima J., Wickner W. (2009) Phosphoinositides and SNARE chaperones synergistically assemble and remodel SNARE complexes for membrane fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 16191–16196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Compton S. J., Jones C. G. (1985) Mechanism of dye response and interference in the Bradford protein assay. Anal. Biochem. 151, 369–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]