Background: Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), a target of coxibs, aspirin, and related drugs, is a sequence homodimer that functions as a conformational heterodimer.

Results: Kinetic and aspirin labeling studies indicate that COX-2 is composed of two equivalent, stable populations of conformational heterodimers.

Conclusion: COX-2 is processed and folds into a pre-existent conformational heterodimer.

Significance: COX-2 half-site functionality results from COX-2 folding into a stable conformational heterodimer.

Keywords: Arachidonic Acid, Cyclooxygenase (COX) Pathway, Drug Action, Eicosanoid, Protein Conformation

Abstract

Prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthase-2 (PGHS-2), also known as cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), is a sequence homodimer. However, the enzyme exhibits half-site heme and inhibitor binding and functions as a conformational heterodimer having a catalytic subunit (Ecat) with heme bound and an allosteric subunit (Eallo) lacking heme. Some recombinant heterodimers composed of a COX-deficient mutant subunit and a native subunit (i.e. Mutant/Native PGHS-2) have COX activities similar to native PGHS-2. This suggests that the presence of heme plus substrate leads to the subunits becoming lodged in a semi-stable Eallo-mutant/Ecat-Native∼heme form during catalysis. We examined this concept using human PGHS-2 dimers composed of combinations of Y385F, R120Q, R120A, and S530A mutant or native subunits. With some heterodimers (e.g. Y385F/Native PGHS-2), heme binds with significantly higher affinity to the native subunit. This correlates with near native COX activity for the heterodimer. With other heterodimers (e.g. S530A/Native PGHS-2), heme binds with similar affinities to both subunits, and the COX activity approximates that expected for an enzyme in which each monomer contributes equally to the net COX activity. With or without heme, aspirin acetylates one-half of the subunits of the native PGHS-2 dimer, the Ecat subunits. Subunits having an S530A mutation are refractory to acetylation. Curiously, aspirin acetylates only one-quarter of the monomers of S530A/Native PGHS-2 with or without heme. This implies that there are comparable amounts of two noninterchangeable species of apoenzymes, Eallo-S530A/Ecat-Native and Eallo-Native/Ecat-S530A. These results suggest that native PGHS-2 assumes a reasonably stable, asymmetric Eallo/Ecat form during its folding and processing.

Introduction

Prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases (PGHSs),2 also known as cyclooxygenases (COXs), catalyze the committed step in prostaglandin biosynthesis, i.e. the conversion of arachidonic acid (AA) plus two O2 molecules plus two electrons to PGH2 (1–4). There are two PGHS isoforms (PGHS-1 and -2) that are encoded by different genes. PGHS-1 is considered to be the constitutive isoform and produces prostaglandins in association with various “housekeeping” functions such as platelet aggregation and renal water reabsorption. PGHS-2 is the inducible isoform that generates prostaglandins in conjunction with cell division and differentiation.

PGHSs are important pharmacologic targets. Both PGHSs are inhibited by traditional, nonspecific nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (nsNSAIDs), including aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen (4, 5). Aspirin at low anti-inflammatory doses is used to prevent second heart attacks and unstable angina by targeting platelet PGHS-1 (6). Coxibs such as celecoxib and functionally related drugs such as diclofenac exhibit relatively greater specificity toward PGHS-2 (7). COX-2 overexpression is associated with colon cancer, and COX-2 inhibitors as well as nsNSAIDs appear to retard carcinogenesis (8–11). Unfortunately, fatal adverse cardiovascular side effects are associated with most COX inhibitors (7, 12–15).

PGHS catalysis involves sequential peroxidase (POX) and cyclooxygenase (COX) reactions. Details are presented in recent reviews (1, 3, 4). In brief, a peroxide oxidizes the heme group of PGHS to an oxyferryl heme radical cation plus water. The heme radical then oxidizes Tyr-385 generating a tyrosyl radical that abstracts the 13 pro-S hydrogen of AA to form an arachidonyl radical that reacts with O2 and undergoes a complex intramolecular rearrangement to produce PGG2. The 15-hydroperoxyl group of PGG2 undergoes a two-electron reduction to an alcohol group to form PGH2. This latter reaction involves the POX activity of PGHS and/or another peroxidase such as glutathione peroxidase.

The structure/function relationships of PGHSs have been studied in considerable detail (1–4). PGHSs are sequence homodimers. The PGHS-2 dimer is quite stable (16), and the monomers do not exchange among dimers (17, 18). Although PGHSs are sequence homodimers, they exhibit half-sites heme and inhibitor binding and function as conformational heterodimers composed of Eallo and Ecat partner monomers (17–25).

Previous studies have shown that certain recombinant heterodimers of human (hu) PGHS-2 composed of a COX-deficient mutant subunit and a native subunit have COX activities similar to native huPGHS-2; an example is G533A/Native huPGHS-2 (17, 18). We envisioned that ligand-induced stabilization enables such heterodimers to become lodged in a catalytically competent (Eallo-Mutant-FA/Ecat-Native-heme) form. Specifically, we hypothesized that the A and B monomers comprising a PGHS-2 dimer normally flux between two Eallo/Ecat forms (i.e. (Eallo-Native-A/Ecat-Native-B) ↔ (Ecat-Native-A/Eallo-Native-B)) and that heme and/or FAs that bind Eallo and/or Ecat stabilize the dimer and slow or prevent the flux. The studies reported here were initiated to test this hypothesis. In addressing this topic, we characterized a number of recombinant heterodimers. Studies of aspirin acetylation with one particular variant, S530A/Native huPGHS-2, led us to the conclusion that PGHSs assume a stable conformational heterodimeric form relatively early in their lifetimes, i.e. during their folding and processing.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Complete protease inhibitor was from Roche Applied Science. Nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid Superflow resin and nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid were from Qiagen. Palmitic acid (16:0), stearic acid (18:0),11-cis-eicosaenoic acid (20:1ω9), flurbiprofen, indomethacin, aspirin, naproxen, FLAG peptide, and FLAG affinity resin were from Sigma. Other nonradioactive fatty acids were from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Hemin was from Frontier Scientific, Logan, UT. Ibuprofen was from Tocris Bioscience. Celecoxib was from physician samples of CelebrexR. [1-14C]AA (1.85 GBq/mmol) and [acetyl-14C]acetylsalicylic acid (1.85 GBq/mmol) were from American Radiolabeled Chemicals. Hexane, isopropyl alcohol, and acetic acid were HPLC grade from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. Anti-PGHS-2 antibodies directed against the 18-amino acid insert unique to PGHS-2 were as described (26). Anti-FLAG antibodies were from LifeTein, South Plainfield, NJ. Horseradish POX-conjugated secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit IgG and goat anti-mouse IgG) were from Bio-Rad. Guanidine hydrochloride was from Invitrogen.

huPGHS-2 Mutagenesis, Expression, and Purification

A cDNA for huPGHS-2 containing an octahistidine (His8) tag at the N terminus was subcloned into pFastBac plasmid (Invitrogen) (17). The QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis protocol (Stratagene) was used to construct the mutants. The mutant heterodimer variants were constructed as described previously (17, 18, 23, 24) using the pFastBac dual vector. Native huPGHS-2, mutant huPGHS-2 homodimers, and heterodimeric huPGHS-2 variants were expressed and purified using procedures described previously (17, 18, 23, 24).

COX and POX Assays

COX activities were determined using measurements of O2 consumption essentially as detailed previously (24). POX reactions were conducted in 2 ml of filtered and degassed 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, containing 50 mm NaCl, 0.1 mm H2O2, 4.5 mm guaiacol, and the indicated concentrations of heme essentially as described previously (17, 27). Formation of the guaiacol oxidation product 3,3′-dimethoxydipheno-4,4′-quinone was monitored at 436 nm (ϵ436 = 6,390 m−1 cm−1).

Titration of huPGHS-2 with Heme

Difference absorption spectra of recombinant forms of apo-huPGHS-2 were obtained upon titration with heme, and Kd values for heme and heme binding stoichiometries were calculated as described previously (24, 28).

Quantification of Aspirin Acetylation

Recombinant native huPGHS-2 and mutant huPGHS-2 variants were incubated with 1 mm [1-14C]acetylsalicylate for 60 min at 37 °C. The 1 mm [1-14C]acetylsalicylate solution was prepared with unlabeled and radiolabeled aspirin in a 14:1 (w/w) ratio. The resulting mixture of huPGHS-2 was added to a 0.5-ml Millipore centrifuge column (30,000), and the unreacted [1-14C]acetylsalicylate was diluted with 50 mm acetylsalicylate in 15 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, containing 30 mm KCl, 25% ethanol, 3.75% glycerol, and 0.0075% C10E6; five wash cycles were used. The amount of labeled protein was quantified by liquid scintillation counting by measuring the counts in the protein bound to the centrifuge column. Acetyl groups per dimer were determined by dividing the moles of labeled aspirin determined by the radioactive counts by the moles of protein dimer determined by the Pierce BCA protein assay.

Quantification of huPGHS-2 Variants by Western Transfer Blotting and Aspirin Acetylation

To quantify aspirin acetylation using SDS-PAGE, huPGHS-2 variants were incubated for 60 min at 37 °C with 1 mm [14C]acetylsalicylate. Samples were denatured in the presence of dithiothreitol and separated on a NuPAGE® Novex® 7% Tris acetate gel with MOPS SDS Running Buffer. The radioactive buffer was collected and discarded. The gel was washed and stained with Coomassie Blue for 1 h and then exposed to a storage phosphor screen (GE Healthcare) for 24 h. The screen was imaged using photo-stimulatable storage phosphorimage acquisition at 200 μm with a Typhoon Trio+ Variable Mode Imager (Amersham Biosciences). The percentages of 14C-acetylated huPGHS-2 glycoforms with molecular masses estimated to be 70 or 72 kDa were quantified using ImageJ software. Anti-FLAG or anti-PGHS-2 antibodies were used to quantify huPGHS-2 variants by Western transfer blotting as described previously (17).

Effect of Guanidine Hydrochloride on Aspirin Acetylation

Native/Native huPGHS-2 and S530A/FLAG-Native were incubated with 1 mm [1-14C]acetylsalicylate for 30 min at room temperature. The resulting mixture was added to a 0.5-ml Millipore centrifuge column, and the column was washed with unlabeled acetylsalicylate. After washing, the labeled protein was diluted with 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, containing 40 mm KCl and 0.1% C10E6 detergent. Various amounts of guanidine hydrochloride were then added, and the samples were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. After centrifugation, the denaturant-treated proteins were incubated again with 1 mm [1-14C]acetylsalicylate for 30 min at room temperature. Total aspirin acetylation was quantified by liquid scintillation counting as described above.

Statistical Analyses

Student's t tests were performed in Microsoft Excel. If the experiments had the same numbers of repetitions, probabilities were calculated with a Student's paired t test, with a two-tailed distribution. If the experiments had different numbers of repetitions, probabilities were calculated with a Student's unequal variance t test, with a two-tailed distribution.

RESULTS

COX and POX Activities of PGHS-2 Dimers Having Y385F Substitutions

In the initial part of our study, we prepared several PGHS-2 variants having Y385F substitutions. The goal was to analyze enzyme forms in which the Eallo and Ecat monomers were clearly defined. A Tyr-385 radical is required to abstract a hydrogen atom from fatty acyl substrates in the first chemical step of COX catalysis (3, 4). In principle, a Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 heterodimer can assume either an (Eallo-Y385F/Ecat-Native) or an (Ecat-Y385F/Eallo-Native) form, but only the (Eallo-Y385F/Ecat-Native) version would, upon binding heme, be capable of COX catalysis (29).

Table 1 shows the kinetic constants for the recombinant huPGHS-2 variants examined in this study, including Y385F/Native huPGHS-2. In terms of Vmax values, we determined the Vmax for O2 consumption experimentally using an O2 electrode in all cases. This value was then normalized in some instances to a Vmax for AA consumption by correcting for differences in the ratios of products derived from PGG2 versus hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HPETEs). Two O2 molecules were consumed in forming PGG2, whereas only one O2 was utilized in the formation of HPETEs, and as discussed in more detail below, there were some differences in the product profiles among the enzyme variants. The product profiles were determined by quantifying the products formed during incubation of 100 μm [1-14C]AA with different enzyme variants. We did not determine product profiles for oxygenation of 2-arachidonylglycerol (2-AG) ether, an uncharged substrate.

TABLE 1.

Kinetic properties of various native and mutant forms of huPGHS-2

huPGHS-2 variants were prepared and purified, and COX and POX activities were assayed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Kinetic values are derived from the average of triplicate determinations ± S.D. except for His8-Y385F/FLAG-S530A huPGHS-2, which was done twice. Kd values for heme binding were from three separate experiments with Y385F/Y385F huPGHS-2 and single titrations with other huPGHS-2 variants. ND means not determined.

| huPGHS-2 variant | COX activity with arachidonic acid |

COX activity with 2-AG ether |

POX activity |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific activitya | Vmax a | Vmax b | Kma | Specific activitya | Vmax a | Kma | Specific activityc | Kd for heme | |

| O2 units/mg protein | O2 units/mg protein | FA units/mg protein | μm | O2 units/mg protein | O2 units/mg protein | μm | % | μm | |

| His8-Native/His8-Native | 36 ± 1.2 | 43 ± 1.7 | 47 | 9.3 ± 1.0 | 30 ± 0.4 | 31 ± 5.4 | 5.4 ± 0.8 | 100 ± 3 | 0.13 ± 0.03 |

| His8-Native/FLAG-Native | 38 ± 1.3 | 42 ± 2.0 | 45 | 12 ± 1.9 | 24 ± 0.8 | 28 ± 0.7d | 8.4 ± 0.7d | 93 ± 2.4 | 0.16 ± 0.05 |

| His8-Y385F/His8-Y385F | 0 | ND | ND | ND | 0 | ND | ND | 20 ± 2.5 | 1.6 ± 0.2 |

| His8-Y385F/FLAG-Native | 33 ± 2.5 | 37 ± 1.3 | 42 | 5.5 ± 0.8e | 23 ± 0.2 | 24 ± 1.2e | 3.6 ± 0.5e | 85 ± 4.5 | 0.37 ± 0.03 |

| His8-Y385F R120Q/FLAG-Native | 34 ± 1.1 | 36 ± 1.3 | ND | 6.2 ± 1.1 | 21 ± 0.2 | 25 ± 1.2 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | ND | ND |

| His8-Y385F R120A/FLAG-Native | 13 ± 0.8f | 16 ± 0.5f | 17 | 10 ± 1.0f | 23 ± 0.6 | 23 ± 0.6 | 8.7 ± 0.7f | 84 ± 2.6 | 0.62 ± 0.09 |

| His8-Y385F/FLAG-R120Q | 28 ± 0.9f | 31 ± 2.0 | ND | 44 ± 10f | 18 ± 0.4 | 24 ± 1.1 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | ND | ND |

| His8-Y385F/FLAG-R120A | 24 ± 0.6f | 34 ± 3.2 | ND | 55 ± 15f | 20 ± 1.2 | 29 ± 2.6 | 7.7 ± 1.6f | ND | ND |

| His8-R120Q/His8-R120Q | 27 ± 0.8d | 41 ± 4.1 | ND | 64 ± 13d | 21 ± 1.1 | 26 ± 1.2 | 12 ± 1.4d | 78 ± 0.3 | 0.22 ± 0.01 |

| His8-R120A/His8-R120A | 18 ± 0.4d | 24 ± 0.6d | 26 | 39 ± 2.8d | 21 ± 0.3 | 21 ± 2.0d | 10 ± 2.7d | 87 ± 5.1 | 0.75 ± 0.16 |

| His8-S530A/His8-S530A | 11 ± 0.5d | 14 ± 0.7d | 16 | 18 ± 3.0d | 4.6 ± 0.02d | 6.6 ± 0.3d | 12 ± 1.3 | 105 ± 0.6 | 0.19 ± 0.02 |

| His8-S530A/FLAG-Native | 21 ± 0.7e | 29 ± 2.3e | 30 | 12 ± 2.4 | 13 ± 0.3e | 17 ± 2.0e | 13 ± 3.4e | 92 ± 0.1 | 0.24 ± 0.05 |

| His8-Y385F S530A/FLAG-Native | 27 ± 1.9 | 30 ± 0.8f | 37 | 15 ± 1.3f | 16 ± 0.9f | 19 ± 1.0f | 5.7 ± 1.0 | ND | ND |

| His8-Y385F/FLAG-S530A | 8.6 ± 0.8f | 11 ± 0.9f | 12 | 6.9 ± 1.8 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

a Data were determined by measuring O2 consumption with an O2 electrode using either 100 μm AA or 50 μm 2-AG ether as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

b Data were calculated from experimentally determined Vmax values adjusting for differences in the ratios of PGG2-derived and monohydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid-derived products as described in the text.

c Data were determined by measuring guaiacol oxidation in the presence of H2O2 as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

d Significant differences from values with His8-Native/ His8-Native huPGHS-2 were determined by Student's t test (p < 0.05).

e Significant differences from values with His8-Native/ FLAG-Native huPGHS-2 were determined by Student's t test (p < 0.05).

f Significant differences from values with His8-Y385F/FLAG-Native huPGHS-2 were determined by Student's t test (p < 0.05).

First, it should be noted (Table 1) that native (i.e. Native/Native) forms of huPGHS-2 having an octahistidine (His8) tag on both monomers or a combination of a His8 tag and a FLAG tag on the individual monomers had quite similar levels of activity and similar Km values with AA and with 2-AG ether, respectively. Thus, the tags used for purification do not significantly affect COX kinetic parameters.

The Y385F/Y385F huPGHS-2 homodimer lacks COX activity, although Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 exhibits about 90% of the Vmax values for both O2 and FA consumption of Native/Native forms of huPGHS-2 with AA (Table 1). The Vmax value for O2 consumption by Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 was 80% of the value for Native/Native forms of huPGHS-2 with 2-AG ether as the substrate.

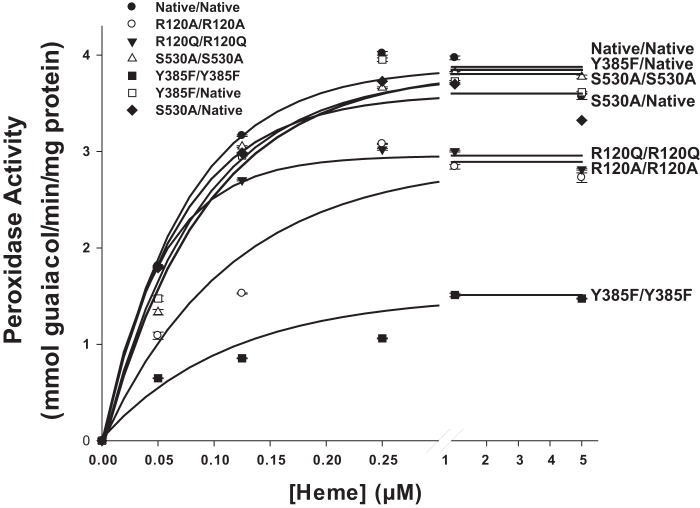

Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 exhibited Km values similar to those observed with Native/Native PGHS-2 when tested with either AA or 2-AG ether, respectively, as substrates. We also compared the COX-specific activities of Native/Native huPGHS-2 versus Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 with substrates other than AA and 2-AG (Fig. 1). There are only minor differences in the specificities for all the substrates tested except for 11,14-eicosadienoic acid, where Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 exhibits only ∼60% of the activity of the Native/Native huPGHS-2; the Km value for 11,14-eicosadienoic acid was the same (∼24 μm) with both Native/Native huPGHS-2 and Y385F/Native huPGHS-2.

FIGURE 1.

Oxygenation of different substrates by Native/Native huPGHS-2 homodimer and Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 heterodimer. Results are shown as rates of O2 consumption determined by measuring COX activity using an O2 electrode as described under “Experimental Procedures” with purified Native/Native huPGHS-2 or Y385F/Native huPGHS-2. Fatty acid substrates were tested at concentrations of 100 μm; 2-AG ether was tested at 50 μm. Experiments with each substrate were repeated with at least three different preparations of enzymes with similar results. The results are shown for a representative experiment involving triplicate determinations. The error bars indicate the average ± S.D. A significant difference from the value with Native/Native huPGHS-2 as determined by the Student's t test (p < 0.05) is indicated with an asterisk.

The Y385F/Y385F huPGHS-2 homodimer exhibits about 30% of the POX activity seen with either Native/Native huPGHS-2 or Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 when POX assays are performed in the presence of ≥1 μm heme (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Under similar assay conditions, Y385F/Y385F ovine PGHS-1 also exhibits about 30% of native PGHS-1 POX activity (30). When the recombinant huPGHS-2 variants were titrated with heme, maximal POX activity occurred at somewhat lower heme concentrations with Native/Native huPGHS-2 than with enzyme forms having Y385F mutations (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Effect of heme concentrations on the peroxidase activities of native and mutant huPGHS-2. Native or mutant versions of huPGHS-2 (70 nm) were mixed with 9 mm guaiacol, heme at the twice the heme concentration indicated in the figure, 100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and 100 mm NaCl in a 1.0-ml reaction volume at room temperature. The peroxidase reactions were initiated by adding an equal volume of 200 μm H2O2 and the absorbance due to oxidation of guaiacol monitored at 436 nm as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The initial rates of hydroperoxide substrate reduction were calculated from the rates of guaiacol oxidation. Each value is from a single determination in one representative experiment. The experiment was repeated three times with Native/Native, Y385F/Y385F, Y385F/Native, and R120A/R120A and two times with R120Q/R120Q and S530A/S530A huPGHS-2, and the same pattern of results was observed.

Previous studies have shown that there is one high affinity heme-binding site per Native/Native huPGHS-2 dimer and that maximum COX activity occurs with one heme per dimer (24). This same heme binding stoichiometry was observed with Y385F/Native huPGHS-2, Y385F/Y385F huPGHS-2, and other huPGHS-2 variants noted in Table 1. However, the affinities of Y385F variants for heme are typically less than that seen with Native/Native huPGHS-2 (Table 1). The Kd values determined for high affinity heme binding to Native/Native, Y385F/Native, and Y385F/Y385F huPGHS-2 were ∼0.15, 0.35, and 1.5 μm, respectively. This suggests that monomers having Y385F substitutions bind heme significantly less tightly than native monomers. These data and those in Fig. 2 also suggest that having a Y385F substitution in one monomer (e.g. Y385F/Native huPGHS-2) slightly attenuates heme binding to the partner monomer.

Overall, examination of COX and POX catalysis and heme binding by Y385F-containing huPGHS-2 variants establish that Mutant/Native PGHS-2 heterodimers can exhibit near native enzymatic activities when the native subunit binds heme efficiently relative to the mutant subunit. As shown and discussed below, some other active site mutants having attenuated heme binding (e.g. R120A) behave in a manner similar to Y385F mutants.

Effects of FAs, nsNSAIDs, and Coxibs on PGHS-2 Dimers Having a Y385F Mutation

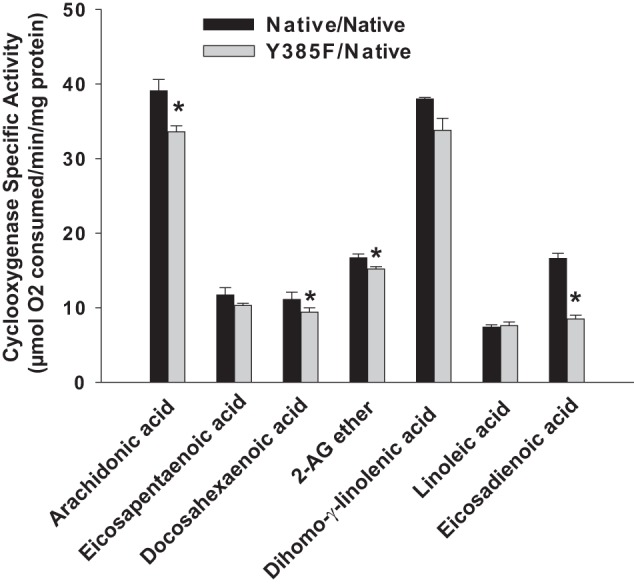

Native/Native huPGHS-2 is allosterically activated by some nonsubstrate FAs, most notably by palmitic acid (PA) (18, 24). As shown in Table 2, Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 is also activated by nonsubstrate FAs. The activation by different FAs shows an FA specificity that parallels that seen with native huPGHS-2, with PA being the most efficient activator among those FAs tested. However, the magnitude of the activation of Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 by various FAs averages about 40% less than that observed with Native/Native huPGHS-2 (Table 2). These observations indicate that a monomer having a Y385F substitution can function as an Eallo monomer when partnered with a native monomer acting as an Ecat monomer; however, with AA as the substrate, enzymes having an intact Tyr-385 in the Eallo subunit exhibit more efficient allosteric activation than an enzyme with a Y385F substitution. PA also stimulates the oxygenation of 2-AG ether by Native/Native and Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 (Fig. 3), but with 2-AG ether the effects of PA are similar with both enzyme forms.

TABLE 2.

Rates of oxygenation of AA by various native and mutant forms of huPGHS-2 in the presence and absence of nonsubstrate fatty acids

| huPGHS-2 varianta | Relative percent of O2 consumption with indicated FA (100 × (FA + AA)/(AA))a |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 16:0 | 12:0 | 18:0 | 18:1Δ9c | 20:1Δ11c | |

| % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| His8-Native/His8-Nativeb | 100 ± 2.3 | 183 ± 1.0c | 117 ± 3.5c | 113 ± 1.3 | 139 ± 0.7c | 136 ± 5.6c |

| His8-Y385F/FLAG-Native | 100 ± 6.8 | 146 ± 3.0c | 103 ± 5.7 | 99 ± 5.6 | 123 ± 2.3c | 126 ± 6.2c |

| His8-Y385F-R120Q/FLAG-Native | 100 ± 6.9 | 102 ± 1.1 | 93 ± 8.4 | 95 ± 5.7 | 94 ± 7.1 | 97 ± 2.5 |

| His8-Y385F-R120A/FLAG-Native | 100 ± 17 | 103 ± 10 | 85 ± 12 | 94 ± 8.4 | 106 ± 20 | 104 ± 8.7 |

| His8-Y385F/FLAG-R120Q | 100 ± 4.7 | 119 ± 8.6 | 107 ± 9.2 | 93 ± 4.9 | 109 ± 6.0 | 102 ± 3.1 |

| His8-Y385F/FLAG-R120A | 100 ± 6.4 | 122 ± 4.1c | 97 ± 6.7 | 92 ± 8.0 | 89 ± 11 | 92 ± 18.4 |

| His8-R120Q/His8-R120Qd | 100 ± 10 | 112 ± 8.3 | 85 ± 11 | 89 ± 13 | 107 ± 8.9 | 119 ± 11 |

| His8-R120A/His8-R120A | 100 ± 4.9 | 91 ± 6.6 | 93 ± 7.5 | 99 ± 9.2 | 92 ± 6.0 | 101 ± 6.3 |

| His8-S530A/His8-S530A | 100 ± 2.6 | 137 ± 7.2c | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| His8-S530A/FLAG-Native | 100 ± 5.9 | 144 ± 7.1c | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| His8-Y385F-S530A/FLAG-Native | 100 ± 7.2 | 106 ± 4.1 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| His8-Y385F/FLAG-S530A | 100 ± 7.9 | 146 ± 20c | ND | ND | ND | ND |

a Enzyme designations and preparations are as in Table 1. ND means not determined.

b Data are from Ref. 24.

c Results are shown as a percentage of the rate of O2 consumption determined using O2 electrode assays of COX activities of huPGHS-2 variants with nonsubstrate FAs (25 μm) in combination with AA (5 μm) versus AA (5 μm) alone except as indicated. Values are averages of triplicate determinations ± S.D. Significant differences from control values were determined using a Student's t test (p < 0.05).

d Nonsubstrate FAs (25 μm) were in combination with AA (2.5 μm) versus AA (2.5 μm) alone.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of palmitic acid on the oxygenation of 2-AG ether by huPGHS-2 variants. Measurements of COX activity were performed in a standard O2 electrode assay with 5 μm 2-AG ether as the substrate in the presence or absence of 25 μm PA as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The same amounts of enzyme protein were used in all assays, and values with No PA were normalized to 100% for the indicated individual huPGHS-2 variants; a comparison of the kinetic values for the different huPGHS-2 variants are presented in Table 1. Results are shown for a single experiment involving triplicate determinations. The error bars indicate the average ± S.D. A significant difference from the value with no PA as determined by the Student's t test (p < 0.05) is indicated with an asterisk.

In another test to compare the properties of Native/Native huPGHS-2 with Y385F/Native huPGHS-2, we examined AA binding to these two enzyme forms after incubations at high enzyme to substrate ratios (Table 3). The principle underlying this set of experiments is that AA binds with about a 20-fold higher affinity to Eallo than Ecat of Native/Native huPGHS-2 (24); therefore, at high enzyme to substrate ratios, the rate of catalysis drops to near zero as substrate is consumed, and at these low AA concentrations the unreacted AA remaining becomes effectively sequestered by Eallo (24). As shown in Table 3, the amounts of unreacted AA remaining bound to Native/Native huPGHS-2 and to Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 are similar under a series of different conditions, including in the presence and absence of PA. At relatively high PA/AA ratios, PA can displace AA from Eallo. We calculate from the data in Table 3 that the Kd values for binding of AA to Eallo of Native/Native huPGHS-2 and Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 are 0.41 and 0.89 μm, respectively; similarly, previous results with Native/Native huPGHS-2 indicated a Kd of 0.26 μm (24).

TABLE 3.

Oxygenation of AA by R120A- and R120Q-containing huPGHS-2 variants at high enzyme to AA ratios

[1-14C]AA (1 μm) was incubated with the indicated concentration of the huPGHS-2 variant form at 37 °C for 8 min; the reactions were stopped, and the radioactive products and unreacted AA were separated by radio-HPLC and quantified as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The results show the percentage of the original [1-14C]AA remaining. Values are averages ± S.D. from three reactions. ND means not determined.

| Reaction components | Unreacted [1-14C]arachidonic acid remaining after 8 min (% of starting radioactivity) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native/Native huPGHS-2 | Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 | Y385F-R120Q/Native huPGHS-2 | Y385F-R120A/Native huPGHS-2 | Y385F/R120Q | Y385F/R120A | R120Q/R120Q | R120A/R120A | |

| 1 μm AA, 0.1 μm enzyme | 4.0 ± 0.7 | 4.3 ± 1.2 | 4.7 ± 0.8 | 7.0 ± 0.9 | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 23 ± 4.2 | 2.4 ± 1.7 | ND |

| 1 μm AA, 1 μm enzyme | 12 ± 3.0a | 8.9 ± 0.8a | 9.9 ± 2.4a | 1.2 ± 0.4a | 30 ± 3.1a | 46 ± 3.3a | 29 ± 0.6a | 1.8 ± 1.2 |

| 1 μm AA, 1 μm enzyme, 5 μm PA | 3.5 ± 1.9b | 4.2 ± 0.5b,c | 6.3 ± 0.7b,d | ND | 9.9 ± 1.4b,d | 28 ± 2.7b,d | 20 ± 1.7b,d | ND |

| 1 μm AA, 1 μm enzyme, 60 μm unlabeled AA added after 4 min | 2.4 ± 0.5b | 2.5 ± 0.5b | 1.7 ± 1.3b | ND | ND | 2.0 ± 0.6b | 3.5 ± 0.2b | ND |

a Significant differences from values with 0.1 μm enzyme were determined using a Student's t test (p < 0.05).

b Significant differences from values with 1 μm enzyme were determined using a Student's t test (p < 0.05).

c 10 μm PA instead of 5 μm PA was used.

d 25 μm PA instead of 5 μm PA was used.

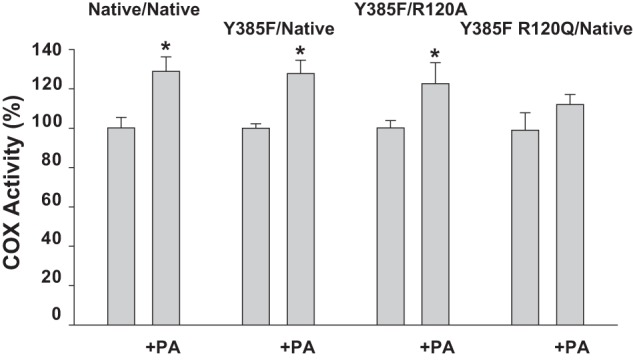

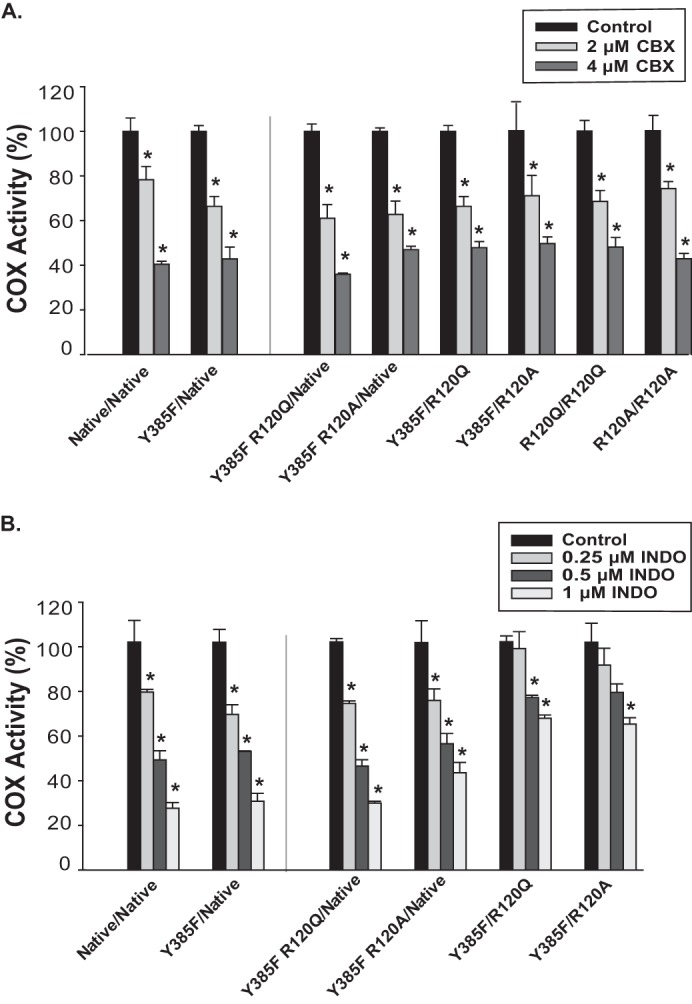

We next determined the responses of Native/Native huPGHS-2 versus Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 to several COX inhibitors that bind preferentially to either Eallo or Ecat. Flurbiprofen and naproxen bind to Eallo more tightly than to Ecat in the case of Native/Native huPGHS-2 and therefore can function as allosteric inhibitors (24). With both inhibitors, binding involves an interaction of the carboxylate group of the inhibitor with Arg-120 (5, 31). The potencies of both time-dependent (Fig. 4, A and B) and instantaneous (data not shown) COX inhibition were similar for both flurbiprofen and naproxen with both Native/Native huPGHS-2 and Y385F/Native huPGHS-2. PA binds to Eallo to potentiate AA and 2-AG ether oxygenation by Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 (Tables 2 and 3 and Fig. 3), and PA attenuated the effects of both flurbiprofen and naproxen (Fig. 5). These results indicate that flurbiprofen and naproxen inhibit Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 as well as Native/Native huPGHS-2 by binding to Eallo.

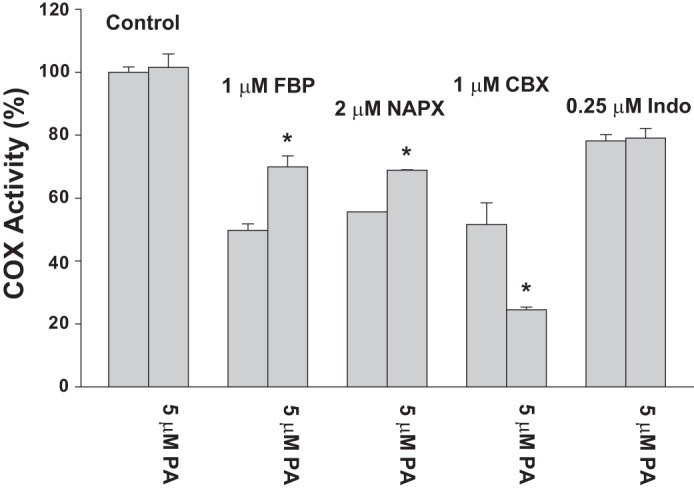

FIGURE 4.

Time-dependent inhibition of native and mutant huPGHS-2 variants by flurbiprofen and naproxen. A, indicated purified huPGHS-2 variants (2 μm) were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of flurbiprofen (FBP) at 37 °C for 15 min and then assayed for COX activity with 100 μm AA using an O2 electrode as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, experiments were performed as in A except using the indicated concentrations of naproxen (NAPX) instead of flurbiprofen. Dilution of the enzyme sample into the assay chamber was such that the concentrations of inhibitor had no effect on COX activity independent of the time-dependent inhibition. Results are shown for a single experiment involving triplicate determinations. The error bars indicate the average ± S.D. Control values for each enzyme variant are normalized to 100%. A significant difference from the value with the control with no inhibitor as determined by the Student's t test (p < 0.05) is indicated with an asterisk.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of PA on time-dependent inhibition of Y385F/Native huPGHS-2. Enzyme samples were incubated in the presence of the indicated inhibitor at the indicated concentration for 30 min at 37 °C in the presence or absence of 5 μm PA. Aliquots of the samples were then added to an O2 electrode assay chamber containing 100 μm AA and COX activity measured as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Dilution of the enzyme sample into the assay chamber was such that the concentrations of inhibitor or PA had no effect on COX activity independent of the time-dependent inhibition. Results are shown for a single experiment involving triplicate determinations. The error bars indicate the average ± S.D. A significant difference from the value with no PA as determined by the Student's t test (p < 0.05) is indicated with an asterisk. NAPX, naproxen; FBP, flurbiprofen; CBX, celecoxib; Indo, indomethacin.

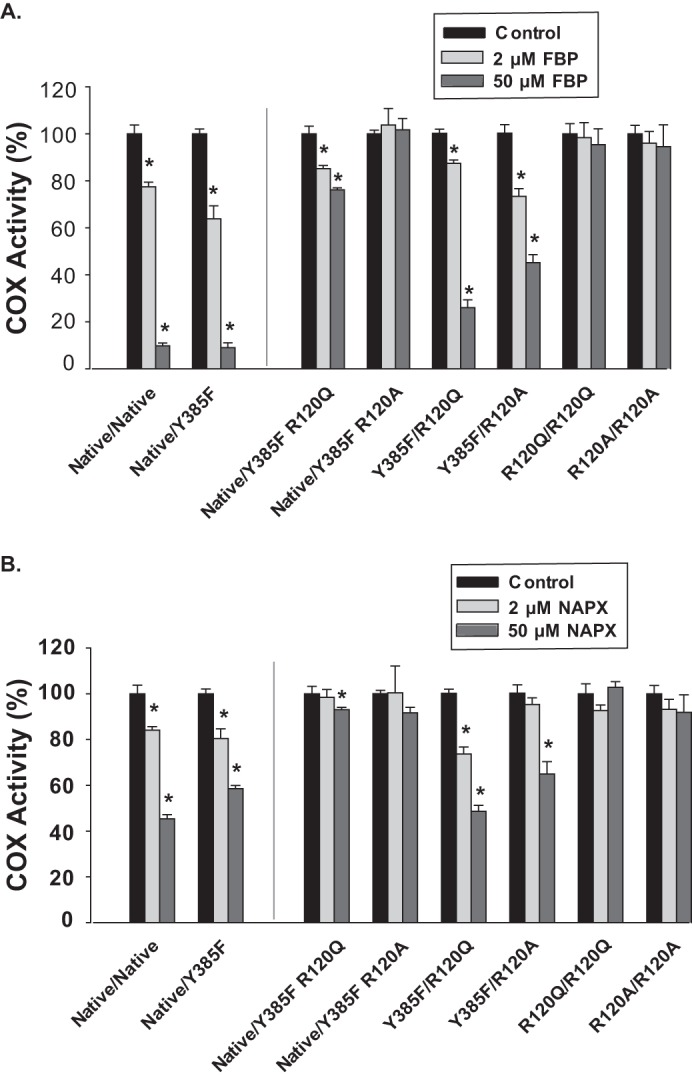

Celecoxib and indomethacin cause time-dependent COX inhibition of Native/Native huPGHS-2 by binding Ecat (24). Celecoxib binding to Ecat is not dependent upon an interaction with Arg-120 (32), whereas the carboxylate group of indomethacin binds via Arg-120 (33). Each of these inhibitors had similar effects on Native/Native huPGHS-2 and Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 (Fig. 6, A and B). Additionally, PA potentiated inhibition by celecoxib and had no effect on inhibition by indomethacin, respectively, with both Native/Native huPGHS-2 and Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 (Fig. 5). This latter result implies that both inhibitors function via Ecat of Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 (24).

FIGURE 6.

Time-dependent inhibition of native and mutant huPGHS-2 variants by celecoxib and indomethacin. A, purified huPGHS-2 variants (2 μm) were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of celecoxib (CBX) at 37 °C for 15 min and then assayed for COX activity with 100 μm AA using an O2 electrode as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, experiments were performed as in A except using the indicated concentrations of indomethacin (INDO) instead of celecoxib. Dilution of the enzyme sample into the assay chamber was such that the concentrations of inhibitor had no effect on COX activity independent of the time-dependent inhibition. Results are shown for a single experiment involving triplicate determinations. The error bars indicate the average ± S.D. Control values for each enzyme variant are normalized to 100%. A significant difference from the value with the control with no inhibitor as determined by the Student's t test (p < 0.05) is indicated with an asterisk.

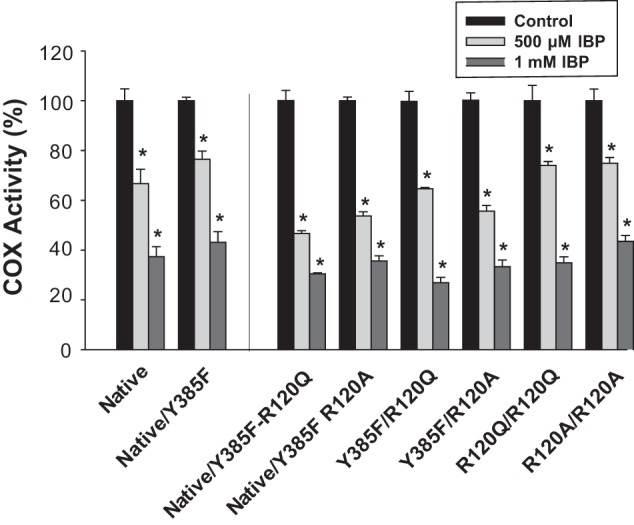

Ibuprofen has generally been considered to be a time-independent (i.e. instantaneous) inhibitor (4, 21, 34), although it does have a modest time-dependent effect on Native/Native huPGHS-2 (24). Ibuprofen had similar inhibitory effects on both Native/Native huPGHS-2 and Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 when tested as an instantaneous inhibitor of either AA (Fig. 7) or 2-AG ether oxygenation (data not shown). Ibuprofen is a somewhat more potent inhibitor of AA oxygenation than 2-AG ether oxygenation.

FIGURE 7.

Instantaneous inhibition of native huPGHS-2 and mutant huPGHS-2 by ibuprofen (IBP). A, indicated concentrations of ibuprofen were present in a standard O2 electrode assay mixture along with 100 μm AA, and purified enzyme was added to initiate AA oxygenation. In all cases O2 consumption was monitored as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Results are shown in each case for a single experiment involving triplicate determinations. The error bars indicate the average ± S.D. Control values for each enzyme variant are normalized to 100%. A significant difference from the value with the control with no inhibitor as determined by the Student's t test (p < 0.05) is indicated with an asterisk.

Finally, we tested the ability of [14C]acetylsalicylate to acetylate Native/Native huPGHS-2 versus Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 (Table 4). The hydroxyl group of Ser-530 is the site of aspirin acetylation in both PGHS-1 and PGHS-2. With each isoform, aspirin acetylates only one monomer (the Ecat monomer) of native PGHS (22–24, 28). In the case of PGHS-1, this leads to complete inhibition of COX activity (22), whereas with PGHS-2, the oxygenase activity is decreased by about 50%, and PGH2 and (15R)-HPETE are formed in comparable amounts (Table 4) (23, 24, 28, 35–37).

TABLE 4.

Acetylation of huPGHS-2 variants with aspirin

| huPGHS-2 variant | Stoichiometry of aspirin acetylation ([14C]acetyl/dimer)a | FA oxygenase activity remaining after aspirin treatmentb | Eicosanoid productsc |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGH2-derived | HETEs | |||

| % (FA units/mg) | % total products | % total products | ||

| His8-Native/His8-Native | 100 (45 units/mg) | 91 | 9 | |

| His8-Native/His8-Native + ASA | 0.94 ± 0.06 (n = 3) | 47 (21 units/mg) | 62 (53d) | 38 (47d) |

| His8-Y385F/FLAG-Native | 100 (42 units/mg) | 82 | 18 | |

| His8-Y385F/FLAG-Native + ASA | 0.80 ± 0.11 (n = 4) (p = 0.12) | 38 (16 units/mg) | 18 | 82 |

| His8-Y385F/His8-Y385F | 0 | 0 | ||

| His8-Y385F/His8-Y385F + ASA | 0.11 ± 0.09e (n = 2) | ND (0/0) | ND | ND |

| His8-R120A/His8-R120A | 100 (26 units/mg) | 86 | 14 | |

| His8-R120A/His8-R120A + ASA | 0.16 ± 0.04e (n = 2) | 91 (24 units/mg) | 84 | 16 |

| His8-Y385F-R120A/FLAG-Native | 92 | 8 | ||

| His8-Y385F-R120A/FLAG-Native + ASA | ND | ND | 19 | 81 |

| S530A/S530A | 100 (16 units/mg) | 79 | 21 | |

| S530A/S530A + ASA | 0.06 ± 0.01e (n = 2) | 100 (16 units/mg) | 87 | 13 |

| His8-Y385F/FLAG-S530A | 100 (12 units/mg) | 80 | 20 | |

| His8-Y385F/FLAG-S530A + ASA | −0.04 ± 0.05e (n = 2) | 110 (13 units/mg)) | 89 | 11 |

| His8-Y385F-S530A/FLAG-Native | 100 (37 units/mg) | 80 | 20 | |

| His8-Y385F-S530A/FLAG-Native + ASA | 0.74 ± 0.03e (n = 2) (p = 0.036) | 48 (18 units/mg) | 20 | 80 |

| S530A/Native | 100 (30 units/mg) | 97 | 3 | |

| S530A/Native + ASA | 0.47 ± 0.04e (n = 4) (p = 0.006) | 74 (22 units/mg) | 54 | 46 |

a Incorporation of [14C]acetyl group from [14C]acetylsalicylate was determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

b Oxygenase activity was determined using a standard COX assay with 100 μm AA, and the value for O2 consumption was corrected for FA turnover as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

c Eicosanoid products formed from 100 μm [1-14C]AA were analyzed by radio-HPLC as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

d Data are from Ref. 23.

e Significant difference from [14C]acetylsalicylate-treated His8-Native/His8-Native huPGHS-2 was determined by Student's t test (p < 0.05).

Aspirin acetylation can be used as a quantitative marker for Ecat of Native/Native huPGHS-2 (24). With apo-Native/Native huPGHS-2 and apo-Y385F/Native huPGHS-2, 0.94 and 0.80 monomers per dimer, respectively, were acetylated by aspirin (Table 4); 0.95 and 0.83 monomers per dimer of Native/Native huPGHS-2 and apo-Y385F/Native huPGHS-2, respectively, were acetylated in the presence of 1 μm heme. Thus, heme does not significantly affect acetylation of either Native/Native or Y385F/Native huPGHS-2. Y385F/Y385F huPGHS-2 was not acetylated by aspirin consistent with previous results with Y385F/Y385F murine PGHS-2 (38). Aspirin acetylation causes both Native/Native huPGHS-2 and Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 to convert more of the AA substrate to hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids, but the effect on the product profile was much more pronounced with the Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 heterodimer.

Our comparisons of Native/Native huPGHS-2 versus Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 with various FAs and COX inhibitors are consistent with the kinetic data on these variants in Table 1. Overall, the results indicate that the Y385F-containing monomer of Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 can function as Eallo in conjunction with the Native monomer functioning as Ecat. The ∼15% decrease in aspirin acetylation of Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 versus Native/Native huPGHS-2 trends with the 10–20% decrease in catalytic activity of Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 versus Native/Native huPGHS-2 with AA and 2-AG ether, respectively; moreover, Y385F/Y385F huPGHS-2 is refractory to aspirin acetylation. Although these differences are not statistically significant, they suggest that ∼15% of holo-Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 is in a catalytically inactive (Ecat-Y385F∼heme/Eallo-Native) form.

Functions of Arg-120 in Eallo and Ecat of huPGHS-2

Crystallographic studies of PGHS-1 and PGHS-2 have indicated that Arg-120 is involved in the binding of various FA substrates and many inhibitors to the COX active sites of both isoforms (5, 39–43), and Arg-120 is clearly important in PGHS-2 catalysis (44–46). We examined whether Arg-120 is important in the functioning of Eallo or Ecat or both. Having established that Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 can serve as a platform for an Eallo/Ecat huPGHS-2, we determined the effect of substitutions of Arg-120 in the Eallo (Y385F) and Ecat (Native) sites individually (Table 1). The results detailed below indicate that Arg-120 is important in the functioning of Ecat and most likely Eallo but that interactions between Arg-120 and its ligands differ somewhat between the two subunits.

R120Q or R120A substitutions in Ecat (i.e. Y385F/R120Q or Y385F/R120A huPGHS-2) lead to relatively small 10–15% decreases in the COX Vmax values with AA when compared with Y385F/Native huPGHS-2. More significantly, the Km values with AA as the substrate are increased 5–10-fold (Table 1). In contrast, substitutions of Arg-120 in Ecat did not affect the Vmax or Km values with 2-AG ether. These results indicate that the guanidino group of Arg-120 of Ecat of huPGHS-2 is important in ligating the carboxyl group of AA via an ionic interaction but that a direct interaction of Arg-120 with substrate is not important for the oxygenation of 2-AG ether. This is consistent with recent crystallographic results (42, 47).

An R120Q substitution in Eallo (i.e. Y385F R120Q/Native huPGHS-2) had no appreciable effect on the Vmax or Km values with AA when compared with Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 (Table 1). An R120A substitution in Eallo (i.e. Y385F R120A/Native huPGHS-2) reduced the Vmax by about 60% with AA as the substrate but had no significant effect on the Km. There were no major effects of either R120Q or R120A substitutions in Eallo on COX kinetics with 2-AG ether as the substrate (Table 1). This is consistent with 2-AG, and now apparently 2-AG ether, binding preferentially to the Ecat monomer of PGHS-2 (21).

We examined the effects of nonsubstrate FAs on the COX activity of heterodimers having an Arg-120 substitution only in Eallo (i.e. Y385F R120Q/Native huPGHS-2 and Y385F R120A/Native huPGHS-2) but did not observe any significant stimulation of AA oxygenation (Table 2). Similarly, PA had no significant effect on AA oxygenation by R120Q/R120Q huPGHS-2 or by R120A/R120A huPGHS-2 as reported previously for R120A/R120A murine PGHS-2 by Vecchio et al. (47). However, PA did cause a small stimulation of COX activity when 2-AG ether was tested as a substrate for Y385F R120Q/Native huPGHS-2 (Fig. 3).

In related experiments to further explore the role of Arg-120 in Eallo, we measured the binding of AA to Y385F-R120Q/Native huPGHS-2 at high enzyme to substrate ratios and the ability of PA to displace bound AA (Table 3). It can be seen that residual AA remains in the case of the Y385F-R120Q/Native huPGHS-2 and that this AA can be displaced by PA. In contrast, no binding of AA above background levels occurred with Y385F-R120A/Native huPGHS-2.

Overall, the results in Tables 2 and 3 and Fig. 5 suggest that nonsubstrate FAs bind weakly to Eallo subunits having an R120Q substitution but not at all to Eallo monomers having an R120A substitution. This implies that H-bonding of the carboxyl group of FAs to a residue at position 120 of Eallo is sufficient for a modest allosteric effect (e.g. by AA or by PA with AA or 2-AG ether as substrate) but that an intact Arg-120 in Eallo is important for significant allosteric activation of COX activity by nonsubstrate FAs. Clearly, one complication of interpreting experiments involving heterodimers containing an Eallo-Y385F subunit is that the Y385F substitution itself compromises the allosteric response to FAs.

We also examined the importance of Arg-120 in Eallo and Ecat on the effects of COX inhibitors on AA oxygenation. We focused on time-dependent inhibition because this provides a test of inhibitor/enzyme interactions in the absence of competing effects of substrates. We first examined flurbiprofen and naproxen, both of which, as described above, can function allosterically by binding to Eallo subunits of native huPGHS-2 and Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 (Figs. 4, A and B, and 5) (24). Arg-120 substitutions in Eallo (i.e. Y385F R120Q/Native huPGHS-2 and Y385F R120A/Native huPGHS-2) led to substantial attenuation of time-dependent inhibition of AA oxygenation by both flurbiprofen and naproxen as compared with Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 control (Fig. 4, A and B); indeed, there was no significant time-dependent inhibition of Y385F R120A/Native by either inhibitor. The time-dependent inhibitory effects of flurbiprofen and naproxen on AA oxygenation were diminished but not eliminated by substitutions of Arg-120 in Ecat (i.e. Y385F/R120Q huPGHS-2 and Y385F/R120A huPGHS-2); in the case of inhibition of Y385F/R120Q huPGHS-2 by naproxen, there was little or no effect. When Arg-120 substitutions were introduced into both Eallo and Ecat (i.e. R120Q/R120Q huPGHS-2 and R120A/R120A huPGHS-2), time-dependent inhibition by flurbiprofen and naproxen was abrogated. Collectively, these results indicate that time-dependent inhibition by flurbiprofen or naproxen, which involves inhibitor binding to Eallo, requires at least an H-bonding interaction between the residue at position 120 of Eallo and the inhibitor. It is not clear if the lack of time-dependent inhibition by naproxen with Y385F R120Q/Native huPGHS-2 and Y385F R120A/Native huPGHS-2 results from a lack of naproxen binding to Eallo in these mutant variants. In this regard, it should be noted that both flurbiprofen and naproxen can cause instantaneous inhibition of AA oxygenation by all the mutants tested (data not shown), including those with Arg-120 substitutions in Eallo; however, in the case of instantaneous inhibition, which is measured with high concentrations of inhibitors in the presence of substrate, the mechanism of inhibition is unclear and may involve binding of these inhibitors to both Eallo and Ecat.

As described above, celecoxib and indomethacin are time-dependent inhibitors that function via Ecat of Native/Native huPGHS-2 and Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 to inhibit COX activity (Figs. 5 and 6, A and B) (24). Substitutions of Arg-120 in Eallo or Ecat alone or simultaneously had no effect on inhibition by celecoxib (Fig. 6A). Celecoxib binding does not involve an important interaction with Arg-120 (48, 49), so this result was not surprising. Time-dependent inhibition by indomethacin was relatively unaffected by substitutions of Arg-120 in Eallo but was attenuated by substitutions of Arg-120 in Ecat. These results are consistent with a role for Arg-120 in Ecat in time-dependent inhibition by inhibitors that function via Ecat and bind to Arg-120 (50).

Ibuprofen causes a time-dependent inhibition of huPGHS-2 but one that is rapidly reversible relative to other common COX inhibitors, including indomethacin, flurbiprofen, and naproxen (24). For this reason, we examined instantaneous inhibition by ibuprofen. Again, for these experiments, huPGHS-2 variants were added to assay chambers containing both ibuprofen and a substrate (i.e. there is no preincubation with inhibitor). Only modest differences in sensitivities among huPGHS-2 variants were observed when AA was used as the substrate (Fig. 7). These latter results were not unexpected because both AA and ibuprofen contain carboxylate groups that can interact with Arg-120 (31).

Table 4 includes the results of studies performed to analyze the effect of aspirin on huPGHS-2 mutants having Arg-120 substitutions. Treatment of R120A/R120A huPGHS-2 with aspirin caused a small increase in protein acetylation as judged from incorporation of radioactivity into the protein from [14C]acetylsalicylate. Treatment of R120A/R120A huPGHS-2 with aspirin had a correspondingly small effect on enzyme activity and no apparent effect on the product profile. Aspirin treatment of Y385F R120A/Native huPGHS-2 shifted the product profile to a form closely resembling that seen with aspirin-treated Y385F/Native huPGHS-2; the level of acetylation was not directly determined. Detailed studies were not performed with Y385F/R120A huPGHS-2 because both Y385F/Y385F huPGHS-2 and R120A/R120A huPGHS-2 were unresponsive to aspirin treatment. Our results suggest that aspirin does not bind sufficiently well to Ecat subunits having substitutions of Arg-120 to permit efficient acetylation of the enzyme.

Functions of Ser-530 in Eallo and Ecat of huPGHS-2

As noted above, Ser-530 is the COX active site residue that is the target of acetylation by aspirin. We investigated the roles of Ser-530 in Eallo and Ecat using appropriate S530A substitutions. Key properties of Ser-530-containing mutants are presented in Tables 1, 2, 4, and 5. Note that the Kd value for heme binding to S530A/S530A huPGHS-2 is similar to that observed for native huPGHS-2 (Table 1). Because of this and our results with Y385F/Native huPGHS-2, we anticipated that a subunit containing only a S530A substitution would compete about equally well with a native subunit for heme in S530A/Native huPGHS-2 (Table 1). Y385F-containing subunits have significantly lower affinities for heme, so we expected that subunits containing a Y385F substitution (i.e. Y385F-S530A/Native huPGHS-2 and Y385F/S530A huPGHS-2) would be primarily in the Eallo form.

TABLE 5.

Oxygenation of AA by S530A-containing huPGHS-2 variants at high enzyme to AA ratios

[1-14C]AA (1 μm) was incubated with the indicated concentration of the huPGHS-2 variant form at 37 °C for 8 min, and the reactions were stopped, and the radioactive under “Experimental Procedures.” The results show the percentage of the original [1-14C]AA remaining. Values are averages ± S.D. from three reactions. ND means not determined.

| Reaction components | Unreacted [1-14C]arachidonic acid remaining after 8 min (% of starting radioactivity) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native/Native huPGHS-2 | Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 | S530A/S530A huPGHS-2 | S530A/Native huPGHS-2 | Y385F S530A/Native | Y385F/S530A | |

| 1 μm AA, 0.1 μm enzyme | 4.0 ± 0.7 | 4.3 ± 1.2 | 6.8 ± 1.1 | 3.2 ± 1.6 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 14 ± 1.3 |

| 1 μm AA, 0.5 μm enzyme | ND | ND | 1.2 ± 0.05 | ND | ND | 8.5 ± 1.9 |

| 1 μm AA, 1 μm enzyme | 12 ± 3.0a | 8.9 ± 0.8a | 4.3 ± 1.5b | 6.5 ± 0.6a | 5.2 ± 0.9a | 9.2 ± 2.8 |

| 1 μm AA, 2 μm enzyme | 27 ± 3.7a,c | ND | 11 ± 1.1b | 11 ± 1.7a | 11 ± 0.02a | 23 ± 5.5b |

| 1 μm AA, 2 μm enzyme, 25 μm PA | 3.5 ± 1.9d,e,f | 4.2 ± 0.5e,f,h, | 6.7 ± 1.6g | 2.4 ± 1.9g | 13 ± 1.4g | 12 ± 3.2g |

| 1 μm AA, 2 μm enzyme, 60 μm unlabeled AA added after 4 min | 2.4 ± 0.5d,f | 2.5 ± 0.5d,f | 1.5 ± 0.6g | 1.5 ± 0.5g | 3.4 ± 0.07g | 7.0 ± 1.0g |

a Significant differences from values with 0.1 μm enzyme were determined using a Student's t test (p < 0.05).

b Significant differences from values with 0.5 μm enzyme were determined using a Student's t test (p < 0.05).

c Data are from Ref. 24.

d 1 μm enzyme instead of 2 μm enzyme were used.

e 5 μm PA instead of 25 μm PA were used.

f Significant differences from values with 1 μm enzyme were determined using a Student's t test (p < 0.05).

g Significant differences from values with 2 μm enzyme were determined using a Student's t test (p < 0.05).

h 10 μm PA instead of 25 μm PA were used.

Consistent with previous results (23), S530A/S530A huPGHS-2 exhibited about 35% of the activity of Native/Native huPGHS-2 (Table 1). Y385F S530A/Native PGHS-2 and Y385F/S530A PGHS-2 exhibit about 85 and 25%, respectively, of the activity of Y385F/Native PGHS-2. Clearly, when the S530A substitution is in the Ecat monomer (i.e. with Y385F/S530A huPGHS-2 and S530A/S530A huPGHS-2), the Vmax values with AA and 2-AG ether are significantly decreased; the Km values are perhaps somewhat greater than those observed with Native/Native huPGHS-2 or Y385F/Native huPGHS-2. An important point is that the oxygenase activity of S530A/Native huPGHS-2 with both AA and 2-AG (Table 1) equals one-half of the sum of the activities of S530A/S530A huPGHS-2 plus Native/Native huPGHS-2. This is consistent with the S530A subunit and the native subunit contributing equally to the net activity of S530A/Native huPGHS-2.

To evaluate whether the S530A substitution affects allosteric regulation of huPGHS-2 by FAs, we examined the effects of PA on COX activities of variants having an S530A substitution in Eallo (Table 2). S530A/S530A huPGHS-2 was significantly stimulated by PA, although Y385F S530A/Native was not. The results with S530A/S530A huPGHS-2 establish that Ser-530 is not essential for allosteric regulation by FAs. However, having a combination of a Y385F and a S530A substitution in Eallo abrogates allosteric stimulation by PA.

We also performed related studies at high enzyme to substrate ratios to further explore the role of Ser-530 in allosteric regulation (Table 5). The results confirm that Ser-530 is not essential for allosteric regulation by FAs. Thus, with huPGHS-2 variants having an S530A but not a Y385F substitution in Eallo (e.g. S530A/S530A huPGHS-2), significant accumulation of unreacted [1-14C]AA occurred and was attributable to the binding of unreacted [1-14C]AA in the COX site of Eallo. [1-14C]AA was displaced from S530A/S530A huPGHS-2 by PA, but PA was unable to displace [1-14C]AA from Y385F S530A/Native huPGHS-2. Again, this is consistent with a lack of stimulation of this latter mutant heterodimer by PA. We interpret these results to mean that Ser-530 partners with Tyr-385 in the allosteric regulation of huPGHS-2 by nonsubstrate FAs. AA does appear to bind to the allosteric site of Y385F S530A/Native huPGHS-2 (Table 5). However, it is unclear whether binding of AA itself to this site causes activation of the Y385F S530A/Native huPGHS-2 mutant. Overall, the results of our analysis of S530A-containing dimers indicate that Ser-530 itself is not required for Eallo to exert its effects but that Ser-530 is needed in Ecat for efficient catalysis.

The results of our studies of [14C]acetylsalicylate acetylation of huPGHS-2 variants having S530A substitutions are presented in Table 4. As expected, S530A/S530A huPGHS-2 was refractory to aspirin acetylation. Because Y385F/Y385F huPGHS-2 is not efficiently acetylated by aspirin, it was also not surprising that Y385F/S530A huPGHS-2 was unreactive with aspirin. With Y385F S530A/Native huPGHS-2, 0.74 subunits/dimer were acetylated by aspirin indicating that compared with Native/Native huPGHS-2, 20% of the Ser-530 sites were unavailable for acetylation. This suggests that 20% of Y385F S530A/Native huPGHS-2 resides in an inactive Ecat-Y385F S530A/Eallo-Native form. This is consistent with the results shown in Table 1 indicating that Y385F S530A/Native huPGHS-2 has 20% less FA oxygenase activity than Native/Native PGHS-2. Aspirin acetylation of apo-S530A/Native huPGHS-2 leads to 50% less labeling than seen with Native/Native huPGHS-2, i.e. only one of every four subunits in the enzyme population was labeled, presumably only dimers with an Eallo-S530A/Ecat-Native structure. Overall, the aspirin labeling studies of S530A/Native huPGHS-2 suggest that the enzyme exists in two stable asymmetric forms (i.e. Eallo-S530A/Ecat-Native and Ecat-S530A/Eallo-Native).

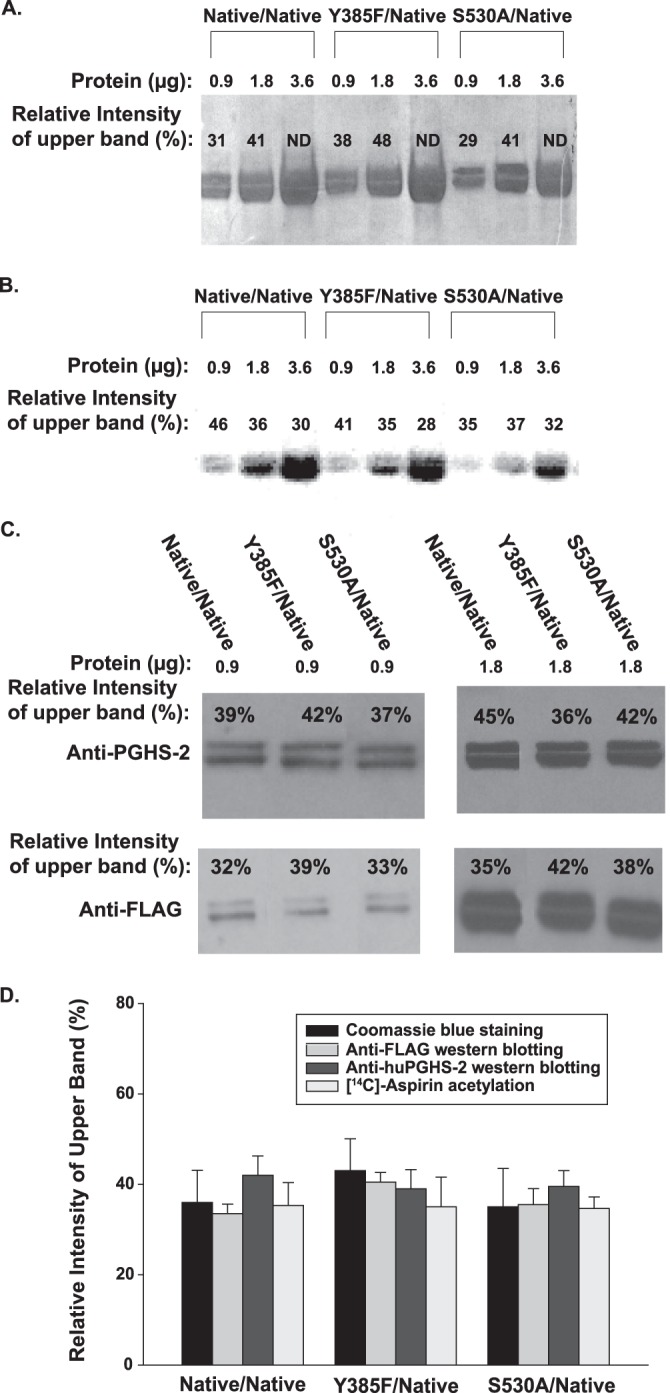

Electrophoretic Properties of huPGHS-2 Dimers

Our studies with S530A variants of huGPHS-2 led us to examine several of the purified enzyme forms for the presence of post-translational modifications that could lead to asymmetric folding and acetylation of huPGHS-2. Well known post-translational modifications of PGHS-2 are cleavage of the signal peptide and N-glycosylation (4, 51). Additionally, in the recombinant forms of huPGHS-2 used in most of our studies, one subunit has a His8 tag and one has a FLAG tag. The recombinant forms of huPGHS-2 that are summarized in Table 1 have an N594A substitution and thus lack the Asn-594 N-glycosylation site of native huPGHS-2 (24). Asn-594 is a site of post-translational N-glycosylation, but there are three sites of co-translational N-glycosylation at Asn-67, Asn-144, and Asn-410 (4, 26, 27, 52–54).

Three different heterodimeric huPGHS-2 variants were subjected to SDS-PAGE (Fig. 8A). Each of these proteins migrated as doublets having estimated molecular masses of 72 and 70 kDa. The distribution of staining in the 72-kDa upper and 70-kDa lower bands was ∼35 and ∼65%, respectively, as determined by staining with Coomassie Blue dye. As expected, treatment of the His8-Native/FLAG-Native huPGHS-2 with peptide:N-glycosidase F yielded a single species with an estimated molecular mass of 65 kDa upon SDS-PAGE (data not shown).

FIGURE 8.

SDS-PAGE, [14C]aspirin acetylation, and Western transfer blotting of Native/Native, Y385F/Native, and S530A/Native variants of huPGHS-2. A, indicated huPGHS-2 variants were expressed and treated with 1 mm [14C]acetylsalicylate for 60 min at 37 °C. The indicated amounts of each variant were then subjected to SDS-PAGE as detailed under “Experimental Procedures.” The gel was stained with Coomassie Blue; ImageJ software was used to estimate the relative amounts of protein in the 70- and 72-kDa bands. (ND, not determined because the ImageJ software could not discriminate between the 70 and 72 kDa bands.) B, phosphorimaging of the same gel as in A; ImageJ software was used to estimate the percentages of 14C radiolabel in the 70- and 72-kDa bands as described under “Experimental Procedures.” C, in an experiment separate from A and B, the purified huPGHS-2 variants (0.9 and 1.8 μg) were subjected to Western transfer blotting using an anti-huPGHS-2 or an anti-FLAG antibody, and the percentages of protein bands with estimated molecular masses of 70 and 72 kDa were quantified using ImageJ software (as indicated for the upper band). D, relative amounts of material in the 72-kDa upper band as quantified by Coomassie Blue staining (0.9 and 1.8 μg) using data from A, aspirin radiolabeling (0.9, 1.8, and 3.6 μg) using data from B, and Western blotting with anti-PGHS-2 (0.9 and 1.8 μg) or anti-FLAG (0.9 and 1.8 μg) antibodies using data from C. Values are averages ± S.D.

The proteins shown in Fig. 8A had been pretreated with [14C]acetylsalicylate prior to the SDS-PAGE, and the relative amounts of radioactivity in the nine upper and lower bands were subsequently quantified by phosphorimaging and densitometry (Fig. 8B). Importantly, the total amount of radiolabel incorporated into the huPGHS-2 variants decreased in going from His8-Native/FLAG-Native huPGHS-2 to His8-Y385F/FLAG-Native huPGHS-2 to His8-S530A/FLAG-Native huPGHS-2 in a ratio of 1.0 to 0.88 ± 0.06 to 0.61 ± 0.03, respectively. This ratio, which is based on densitometry measurements of the 18 bands in Fig. 8B, is quite consistent with the more direct measurements of [14C]acetylsalicylate radiolabeling in Table 4.

Finally, in an independent but related experiment, the relative amounts of anti-FLAG and anti-PGHS-2 immunoreactivity in the 72- and 70-kDa bands of the three huPGHS-2 variants was determined by Western transfer blotting with anti-FLAG or anti-PGHS-2 antibodies. The results are shown in Fig. 8C.

As summarized in Fig. 8D, the fractional levels of protein staining, aspirin labeling, anti-FLAG reactivity, and anti-PGHS-2 reactivity in the upper (and lower) band all paralleled one another with the three different huPGHS-2 variants examined. The results imply that aspirin acetylation occurs independent of N-glycosylation status or the His8 or FLAG purification tags. In short, the difference between Eallo versus Ecat does not appear to be a downstream consequence of the presence of the His8 versus FLAG tags, cleavage of the signal peptide, or the N-glycosylation pattern.

Treatment of huPGHS-2 Variants with Guanidine Hydrochloride

Examination of aspirin acetylation of His8-S530A/FLAG-Native huPGHS-2 suggested that this heterodimer is composed of two stable populations of conformers, one that is sensitive to aspirin (i.e. Eallo-S530A/Ecat-Native) and one that is not (i.e. Ecat-S530A/Eallo-Native). We determined whether treatment of His8-S530A/FLAG-Native huPGHS-2 with a mild denaturant would foster an interchange between these putative forms. We first tested both Native/Native huPGHS-2 and His8-S530A/FLAG-Native huPGHS-2 for their sensitivities to GdnHCl to choose a concentration that would cause only a slight decrease in activity. We then treated each enzyme with [14C]acetylsalicylate before and after treatment with an appropriate concentration of GdnHCl (Table 6). GdnHCl treatment had no appreciable effect on the level of aspirin acetylation. This result suggests that mild denaturant treatment does not foster an interchange between the Eallo and Ecat monomers comprising Native/Native huPGHS-2 dimers or the Eallo and Ecat monomers of S530A/Native huPGHS-2 dimers.

TABLE 6.

The effect of guanidine hydrochloride on cyclooxygenase activity and aspirin acetylation of huPGH-2 variants

Recombinant Native/Native and S530A/Native huPGHS-2 (6 μm) were prepared as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The enzymes were incubated with the indicated concentrations of GdnHCl for 30 min at room temperature, and COX activities were measured (as indicated in the table) with or without GdnHCl included in the assay mixture. In parallel experiments, Native/Native and S530A/Native huPGHS-2 (6 μm) were incubated with 1 mm [1-14C]acetylsalicylate for 30 min at room temperature; the labeled protein was then treated with the indicated concentration of GdnHCl at room temperature for 30 min. After filtration to remove GdnHCl, the proteins were incubated again with 1 mm [1-14C]acetylsalicylate for 30 min at room temperature, and the stoichiometry of acetylation was quantified as detailed under “Experimental Procedures.” Values for COX activities and aspirin acetylation represent the means ± S.D. Superscripts denote differences (p < 0.05) versus the appropriate control values as determined using a Student's t test.

| huPGHS-2 variant | GdnHCl | Cyclooxygenase activity | Stoichiometry of acetylation ([14C]acetyl/dimer) |

|---|---|---|---|

| m | % | ||

| His8-Native/His8-Native | 0 | 100.0 ± 3.0 (no GdnHCl in assay) | 0.83 ± 0.16 |

| 95 ± 2.0 (0.1 m GdnHCl in assay) | |||

| 0.125 m | 92 ± 3.3 (no GdnHCl in assay) | 0.88 ± 0.01 | |

| 76 ± 0.6a (0.10 m GdnHCl in assay) | |||

| 0.25 m | 76 ± 4.0b (no GdnHCl in assay) | 0.90 ± 0.09 | |

| 63 ± 8.3a (0.10 m GdnHCl in assay) | |||

| His8-S530A/FLAG-Native | 0 | 100 ± 3.4 (no GdnHCl in assay) | 0.58 ± 0.06 |

| 90 ± 3.1 (0.05 m GdnHCl in assay) | |||

| 0.05 m | 93 ± 0.3c (no GdnHCl in assay) | 0.59 ± 0.11 | |

| 82 ± 1.5d (0.05 m GdnHCl in assay) | |||

| 0.125 m | 75 ± 3.1c (no GdnHCl in assay) | 0.43 ± 0.01e | |

| 57 ± 5.3d (0.05 m GdnHCl in assay) |

a Data are different from Native/Native huPGHS-2 control sample treated without GdnHCl but with 0.1 m GdnHCl in assay (p < 0.05).

b Data are different from Native/Native control sample treated without GdnHCl and with no GdnHCl in assay (p < 0.05).

c Data are different from S530A/Native control sample treated without GdnHCl and with no GdnHCl in assay (p < 0.05).

d Data are different from S530A/Native control sample treated without GdnHCl and with 0.05 m GdnHCl in assay (p < 0.05).

e Data are different from S530A/Native control sample treated without GdnHCl (p < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

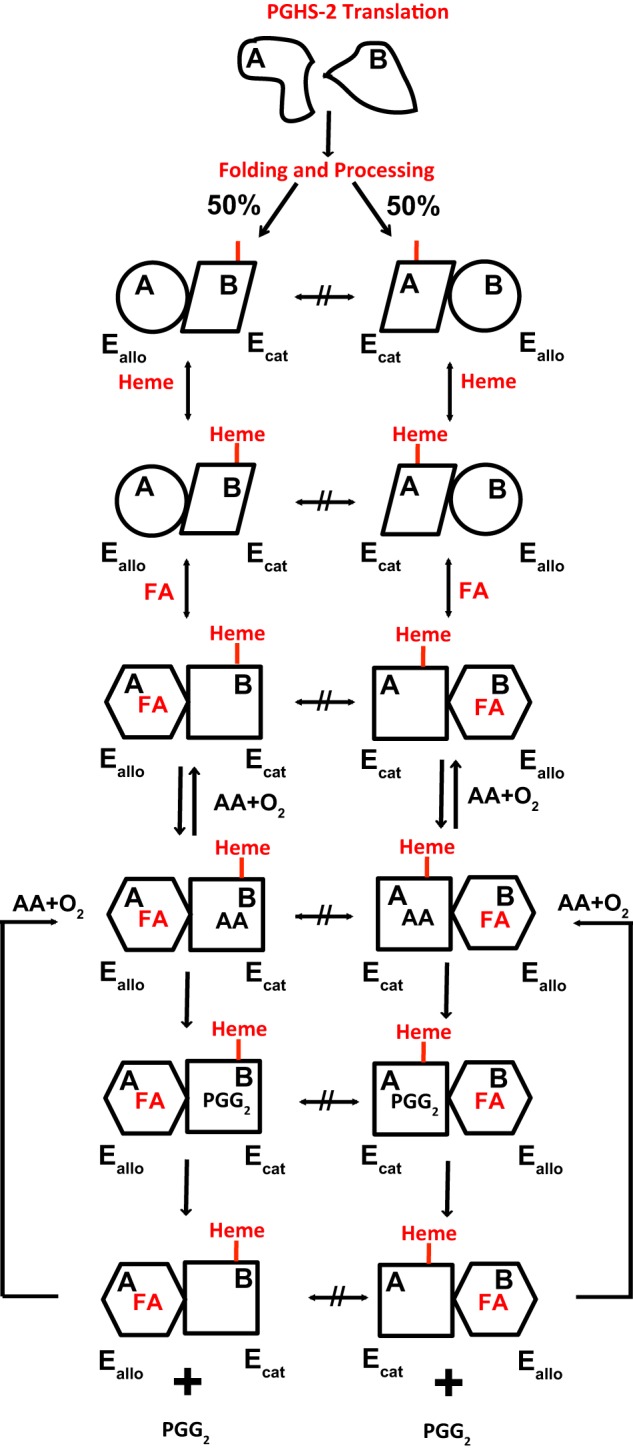

PGHS-2 as a Pre-existent Conformational Heterodimer

Our studies suggest that an early event in the life cycle of PGHS-2 is its translation, folding, and processing into a stable conformational heterodimer and that subsequently the individual monomers do not flux between Eallo and Ecat conformations (Fig. 9). Thus, the enzyme falls into the category of a pre-existent conformational heterodimer (55, 56). Secondary to the formation of PGHS-2 heterodimers, more subtle and reversible structural changes occur in the pre-existent Eallo and Ecat monomers in response to ligand binding (Fig. 9) (24). These latter changes underlie the allosteric regulation of the enzyme by nonsubstrate FAs and certain inhibitors as well as time-dependent inhibition of PGHS-2 by many COX inhibitors (24).

FIGURE 9.

Model for the folding and processing of Native/Native huPGHS-2 to yield two pre-existent conformational heterodimers that are allosterically regulated by fatty acids. Subunits A and B of Native/Native huPGHS-2 have identical primary structure folds but are processed so as to form a pair of stable conformational heterodimers. In one heterodimer, the A subunit is Eallo, and the B subunit is Ecat. In the other heterodimer, the A subunit is Ecat, and the B subunit is Eallo. Heme binds preferentially to Ecat subunits. The Eallo subunits have a relatively higher affinity for FAs, and the binding of FAs to Eallo allosterically influences the catalytic efficiency of the partner Ecat subunit. Once a conformational heterodimer is formed, the monomers comprising the dimer do not flux between Eallo and Ecat forms.

The results of our studies on aspirin acetylation of several recombinant huPGHS-2 heterodimers are inconsistent with our initial prediction that monomer pairs rapidly flux between two Eallo/Ecat forms. The results also fail to support the notion that ligand binding is causal in effecting an interconversion between the Eallo/Ecat pairs of recombinant Mutant/Native heterodimers.

The clearest example of a stable, pre-existent heterodimer is S530A/Native huPGHS-2. We had anticipated that incubating S530A/Native huPGHS-2 with [14C]acetylsalicylate in the absence of heme would lead to acetylation of all of the Native subunits as they fluxed between putative Eallo-S530A/Ecat-Native and Ecat-S530A/Eallo-Native forms. Instead, only about half of the Native subunits reacted with aspirin. The results indicate that in solution S530A/Native huPGHS-2 is a stable mixture of noninterchangeable Eallo-S530A/Ecat-Native and Ecat-S530A/Eallo-Native forms in approximately equal proportions. Measurements of heme binding suggested that heme binds with roughly equal affinities to both S530A-containing and Native subunits. Additionally, the experimentally determined Vmax value for S530A/Native huPGHS-2 is almost the same as the Vmax value calculated for S530A/Native huPGHS-2 from Vmax values for Native/Native and S530A/S530A huPGHS-2 with the assumption that the subunits are equally distributed between Eallo and Ecat forms.

In related experiments, aspirin labeling studies of Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 in the context of Vmax measurements suggest that about 90% of this heterodimer pre-exists in a catalytically competent (Eallo-Y385F/Ecat-Native) form. The decreases in both aspirin labeling and Vmax values for Y385F/Native versus Native/Native huPGHS-2 are small. However, the results are consistent with those obtained with S530A/Native huPGHS-2. Similarly, aspirin labeling studies of Y385F S530A/Native PGHS-2 suggest that ∼80% of this variant is in the catalytically active [Eallo-Y385F S530A/Ecat-Native] form. Again, this value is consistent with kinetic measurements that predict that 80% of the Native monomers of this variant are in the Ecat form.

The implication of both kinetic and aspirin labeling studies of several mutant huPGHS-2 heterodimers is that Native/Native huPGHS-2 also becomes lodged in two different Eallo/Ecat forms during the translation of PGHS-2 mRNA and the processing of newly formed PGHS-2 dimers (Fig. 9). Small molecular weight ligands (e.g. heme or PA) do not subsequently affect the relative proportions of the two types of dimer (i.e. Eallo-Native-A/Ecat-Native-B and Ecat-Native-A/Eallo-Native-B). GdnHCl also fails to effect an interconversion between forms.

After huPGHS-2 matures into a relatively immutable Ecat/Eallo structure, nuanced changes can occur in response to ligands in its environment that are important in the allosteric regulation of the enzyme. For example, the binding to Eallo of some nonsubstrate FAs promotes activity (Fig. 9) (24), whereas inhibitors such as flurbiprofen and naproxen inhibit activity by binding to Eallo (24). Moreover, some inhibitors that bind to Ecat and function in a time-dependent manner cause structural changes in the enzyme. We did not detect heme-induced structural changes in Ecat of huPGHS-2 (e.g. effects on aspirin acetylation) nor does heme affect trypsin cleavage of huPGHS (57), but we cannot rule out the possibility that such changes occur. Certainly, heme binding does alter the structure of PGHS-1 (58, 59).

The recombinant huPGHS-2 variants used in our studies are heterogeneous with respect to the following: (a) N-glycosylation; (b) presence of His8 and FLAG tags used for purification, and (c) mutations in selective monomers. The patterns of aspirin acetylation of Native/Native, Y385F/Native, and S530A/Native huPGHS-2 were found to be similarly independent of both gross N-glycosylation status and the distribution of purification tags. Although not proving the point, the aspirin labeling results with the His8-Native/FLAG-Native huPGHS-2 heterodimer in the context of the aspirin labeling studies of Y385F/Native and S530A/Native huPGHS-2 are not inconsistent with Native/Native huPGHS-2 folding into two equal and stable subpopulations (i.e. Eallo-Native-A/Ecat-Native-B and Eallo-Native-B/Ecat-Native-A) that do not readily interchange. This would put native PGHS-2 into the category of pre-existent stable conformational heterodimers of which there now are numerous examples (55, 56, 60, 61). Recent NMR studies have challenged the idea that there are structural differences in enzymes such as tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase, tryptophanyl- tRNA synthetase, and cAMP receptor protein (61); however, there is functional evidence that these three enzymes are pre-existent conformational heterodimers. In the case of PGHSs, there is crystallographic evidence that active site ligands bind differently to the two monomers comprising a dimer (24, 42, 43). There are ligand-induced structural changes in a loop involving residues 123–126 at the interface between the two monomers of PGHS-1 (22, 62). This loop is just downstream of Arg-120.

Our studies indicate that the monomers of the recombinant apo-PGHS-2 dimer are isolated as stable pre-existent Eallo/Ecat pairs. Although neither addition nor removal of heme from apo-PGHS-2 appears to affect this equilibrium, it is possible that the binding of heme to one monomer during folding and processing influences the Eallo versus Ecat distribution of individual monomers. When monomers having substitutions in certain COX active site residues (e.g. Ser-530, Arg-120, and Tyr-385) are co-expressed and co-fold with the native subunit, the proportion of monomers in the Ecat form does correlate with the relative heme binding affinity of the individual monomers. In short, heme could act as a co-chaperone during the folding and processing of PGHS-2 in the endoplasmic reticulum.

Finally, with respect to the effect of heme on PGHS-2 structure, it should be noted that it is possible that high concentrations of heme overextended periods could affect the Eallo/Ecat distribution between monomer partners. Most of the crystal structures of PGHSs have been determined after crystallization of the proteins at high heme concentrations, well above the Kd values for both high and low affinity heme binding. Heme is typically observed in both monomers (24, 42, 43, 62).

Different Roles of Active Site Residues in Ecat Versus Eallo of PGHS-2

For PGHSs to function as conformational heterodimers, at least some amino acids, including active site residues, must perform different roles in the two subunits. The clearest example occurs with Tyr-385. This residue is required by Ecat for COX catalysis but is not by itself essential in Eallo for allosteric potentiation of COX activity by FAs. Similarly, examination of Y385F/Native huPGHS-2 indicates that Tyr-385 in Eallo is not required for inhibitory responses to either flurbiprofen or naproxen, both of which function via Eallo. However, studies with Y385F S530A/Native huPGHS-2 suggest that Tyr-385 does partner with Ser-530 in the allosteric regulation by nonsubstrate FAs.

Many previous studies have implicated Arg-120 as an important residue in the oxygenation of AA (5, 39–41, 43–46) but not 2-AG (42, 63). We find that Arg-120 is particularly important in Ecat where it contributes to high affinity FA-substrate binding; lack of an ionic interaction of AA with Arg-120 in Ecat reduces its affinity for AA by 5–10-fold. It is known that residues in the hydrophobic groove of PGHS-2 also contribute importantly to AA binding (47). H-bonding interactions of FAs with Arg-120 in Eallo are sufficient for allosteric potentiation of COX activity; in vivo, given the relatively high FA concentrations, H-bonding interactions may be sufficient. It is certainly possible that yet to be identified lipids lacking a carboxylate group could also act as allosteric regulators of PGHSs.

Arg-120 in Eallo is important for time-dependent, allosteric inhibition by flurbiprofen and naproxen, which function by binding Eallo. In contrast, mutations of Arg-120 in Ecat do not have major effects on time-dependent inhibition by either flurbiprofen or naproxen. Consistent with previous reports (31, 33, 46, 48, 49, 64), time-dependent inhibition by celecoxib and related compounds is insensitive to mutations of Arg-120 in either Eallo or Ecat. Time-dependent inhibition by indomethacin was partially attenuated by mutations of Arg-120 in Ecat and unaffected by mutations of Arg-120 in Eallo. Indomethacin exhibits important interactions with Arg-120 in addition to other active site residues, including Val-349, that have been implicated in time-dependent inhibition (31, 33, 46, 50, 64).

Previous studies of PGHS dimers having Ser-530 mutations in both subunits have established that this residue is not essential for COX activity. Ser-530 does, however, contribute to the stereochemical efficiency of catalysis and the responses to certain inhibitors, notably diclofenac (23, 65–68). Our present results indicate that Ser-530 by itself in Eallo is not particularly important for allosteric potentiation by FAs but that Ser-530 does play an important role in Ecat in optimizing the kinetic efficiency of the enzyme. We presume that Ser-530 in Ecat is important in the deprotonation of Tyr-385 requisite for formation of the Tyr-385 radical (3, 69, 70) and/or that Ser-530 helps to appropriately juxtapose the Tyr-385 radical with the 13 pro-S hydrogen of AA (67).

Finally, we would point out that this study and other studies have indicated that some ligands have a preference for Ecat, including celecoxib, indomethacin, aspirin, and diclofenac. Other ligands have a preference for Eallo, including AA, nonsubstrate FAs, naproxen, flurbiprofen, and ibuprofen. It will be of interest to learn more about the biochemical basis for these preferences.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Bill Lands, Michael Malkowski, and Gilad Rimon for carefully reading and editing this manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM68848, CA130810, and HL117798. W. L. S. serves as a consultant for Cayman Chemical Co., products from which were used in this study.

- PGHS

- prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthase

- AA

- arachidonic acid

- FA

- fatty acid

- hu

- human

- HPETE

- hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid

- nsNSAID

- nonspecific nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- PA

- palmitic acid

- PG

- prostaglandin

- POX

- peroxidase

- GdnHCl

- guanidine hydrochloride

- 2-AG

- 2-arachidonylglycerol.

REFERENCES

- 1. Schneider C., Pratt D. A., Porter N. A., Brash A. R. (2007) Control of oxygenation in lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase catalysis. Chem. Biol. 14, 473–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rouzer C. A., Marnett L. J. (2009) Cyclooxygenases: structural and functional insights. J. Lipid Res. 50, S29–S34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tsai A. L., Kulmacz R. J. (2010) Prostaglandin H synthase: resolved and unresolved mechanistic issues. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 493, 103–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith W. L., Urade Y., Jakobsson P. J. (2011) Enzymes of the cyclooxygenase pathways of prostanoid biosynthesis. Chem. Rev. 111, 5821–5865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Duggan K. C., Walters M. J., Musee J., Harp J. M., Kiefer J. R., Oates J. A., Marnett L. J. (2010) Molecular basis for cyclooxygenase inhibition by the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug naproxen. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 34950–34959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Patrono C., García Rodríguez L. A., Landolfi R., Baigent C. (2005) Low-dose aspirin for the prevention of atherothrombosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 2373–2383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grosser T., Fries S., FitzGerald G. A. (2006) Biological basis for the cardiovascular consequences of COX-2 inhibition: therapeutic challenges and opportunities. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 4–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nakanishi M., Montrose D. C., Clark P., Nambiar P. R., Belinsky G. S., Claffey K. P., Xu D., Rosenberg D. W. (2008) Genetic deletion of mPGES-1 suppresses intestinal tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 68, 3251–3259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Uddin M. J., Crews B. C., Blobaum A. L., Kingsley P. J., Gorden D. L., McIntyre J. O., Matrisian L. M., Subbaramaiah K., Dannenberg A. J., Piston D. W., Marnett L. J. (2010) Selective visualization of cyclooxygenase-2 in inflammation and cancer by targeted fluorescent imaging agents. Cancer Res. 70, 3618–3627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fischer S. M., Hawk E. T., Lubet R. A. (2011) Coxibs and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in animal models of cancer chemoprevention. Cancer Prevention Research 4, 1728–1735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Taketo M. M. (2012) Roles of stromal microenvironment in colon cancer progression. J. Biochem. 151, 477–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Renda G., Tacconelli S., Capone M. L., Sacchetta D., Santarelli F., Sciulli M. G., Zimarino M., Grana M., D'Amelio E., Zurro M., Price T. S., Patrono C., De Caterina R., Patrignani P. (2006) Celecoxib, ibuprofen, and the antiplatelet effect of aspirin in patients with osteoarthritis and ischemic heart disease. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 80, 264–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grosser T., Yu Y., Fitzgerald G. A. (2010) Emotion recollected in tranquility: Lessons learned from the COX-2 saga. Annu. Rev. Med. 61, 17–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Trelle S., Reichenbach S., Wandel S., Hildebrand P., Tschannen B., Villiger P. M., Egger M., Jüni P. (2011) Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. BMJ 342, c7086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yu Y., Ricciotti E., Scalia R., Tang S. Y., Grant G., Yu Z., Landesberg G., Crichton I., Wu W., Pure E., Funk C. D., FitzGerald G. A. (2012) Vascular COX-2 modulates blood pressure and thrombosis in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 132ra154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xiao G., Chen W., Kulmacz R. J. (1998) Comparison of structural stabilities of prostaglandin H synthase-1 and -2. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 6801–6811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yuan C., Rieke C. J., Rimon G., Wingerd B. A., Smith W. L. (2006) Partnering between monomers of cyclooxygenase-2 homodimers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 6142–6147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]