Background: Understanding of the self-renewal and differentiation of dental epithelial stem cells (DESCs) is important for tooth regeneration therapies.

Results: Depletion of FGF signaling suppressed self-renewal and led to differentiation of DESCs.

Conclusion: FGF signaling is essential for maintenance of DESCs.

Significance: The finding sheds new light on the mechanism by which the homeostasis, expansion, and differentiation of DESCs are regulated.

Keywords: Development, Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF), Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor (FGFR), Stem Cells, Tooth, Wnt Signaling

Abstract

A constant supply of epithelial cells from dental epithelial stem cell (DESC) niches in the cervical loop (CL) enables mouse incisors to grow continuously throughout life. Elucidation of the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying this unlimited growth potential is of broad interest for tooth regenerative therapies. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling is essential for the development of mouse incisors and for maintenance of the CL during prenatal development. However, how FGF signaling in DESCs controls the self-renewal and differentiation of the cells is not well understood. Herein, we report that FGF signaling is essential for self-renewal and the prevention of cell differentiation of DESCs in the CL as well as in DESC spheres. Inhibiting the FGF signaling pathway decreased proliferation and increased apoptosis of the cells in DESC spheres. Suppressing FGFR or its downstream signal transduction pathways diminished Lgr5-expressing cells in the CL and promoted cell differentiation both in DESC spheres and the CL. Furthermore, disruption of the FGF pathway abrogated Wnt signaling to promote Lgr5 expression in DESCs both in vitro and in vivo. This study sheds new light on understanding the mechanism by which the homeostasis, expansion, and differentiation of DESCs are regulated.

Introduction

Understanding the self-renewal and differentiation of stem cells (SCs)6 and the contribution of their microenvironment, designated as the “niche,” is a key issue for tissue engineering and regeneration therapies. Although the niche varies in nature and location in different tissue types (1, 2), it provides a protective environment to nurture SCs; it prevents SC reserves from undergoing differentiation and apoptosis, as well as preventing SCs from excessive propagation, to maintain tissue homeostasis (2). The cervical loop (CL) of mouse incisors is an SC niche where a population of self-renewing dental epithelial SCs (DESCs) resides that is responsive for the continuous growth and regenerative potential of mouse incisors throughout life (3–7). The CL is formed at the apical end of the developing tooth and is composed of the inner and outer enamel epithelia, stellate reticulum, and stratum intermedium (8). We recently reported that the CL contains both label-retaining and Lgr5-expressing cells, which represent slow-cycling and active DESCs, respectively (9). These Lgr5-expressing active DESCs highly express CD49f, form DESC spheres containing both quiescent and active SCs, and have the potential to differentiate into multiple lineages of tooth epithelial cells. Furthermore, the DESCs can be enriched by CD49fBright-based cell sorting and maintained and expanded in vitro by the Matrigel-based sphere culture system (9). However, how cell signaling between DESCs and adjacent dental stromal cells controls DESC self-renewal and expansion and the generation of ameloblasts or other lineages of tooth epithelial cells is not well understood.

The fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and FGF receptor (FGFR) families have been shown to constitute reciprocal regulatory communication loops between the epithelial and mesenchymal compartments, playing important roles in tooth formation and regeneration (10–14). The FGF family consists of 18 receptor-binding members that regulate a broad spectrum of cellular activities (15). The FGF has been implicated in tooth morphogenesis via the activation of FGFR tyrosine kinases encoded by four highly homologous genes. In the tooth, the FGF and its cognate FGFR isoforms are expressed in a highly spatiotemporal-specific manner and constitute a directional regulatory axis between the mesenchymal and epithelial compartments. On the one hand, FGF4, -8, and -9 are expressed in the epithelium and function redundantly in regulating adjacent mesenchymal cell proliferation and/or preventing apoptosis (16). On the other hand, Fgf3 and Fgf10 are exclusively expressed in dental mesenchymal cells and promote proliferation of dental epithelial cells in the CL (5, 10, 17). Mice deficient in FGF10 fail to develop incisor CL (11); however, it is not clear whether FGF10 is specifically required to maintain DESCs or the DESC niche. Recent lineage tracing experiments in vivo show that the Sox2-positive DESCs give rise to multiple lineages of tooth epithelial cells. Interestingly, FGF8, instead of FGF10, is required for Sox2 expression in the CL (18). The cognate receptors for FGF3 and FGF10, Fgfr1IIIb and Fgfr2IIIb isoforms, are expressed in the dental epithelium (19). Ablation of Fgfr1 in dental epithelial cells affects enamel formation without disrupting ameloblast differentiation (20). Disruption of Fgfr2IIIb stops tooth development at the budding stage (21). Suppression of FGFR2 signaling during embryonic stages leads to abnormal development of the labial CL and the inner enamel epithelial layer. However, expression of the same mutant in the postnatal stage impairs incisor enamel formation, accompanied by decreased proliferation of the transit amplifying cells, and leads to degradation of the incisors in a reversible manner (14). Loss-of-function mutation of Sprouty, a negative feedback regulator of FGFR and other receptor tyrosine kinases, leads to an increase in tooth numbers, ectopic ameloblast differentiation, and enamel formation in lingual CLs (12, 22–24). All of these results demonstrate the importance and tight regulation of FGF signaling in tooth development. However, how FGF signaling regulates the self-renewal and differentiation of DESCs is not well understood.

We reported earlier that tissue-specific ablation of Fgfr2 in dental epithelial cells leads to severe defects in maxillary incisors that lack ameloblasts and enamel, as well as having poorly developed odontoblasts (13). Although the CL in Fgfr2 conditional null maxillary incisors is formed initially, it fails to continue to develop and gradually diminishes soon after birth, suggesting that FGFR2 signaling is essential for maintaining the DESC niche required for incisor development and lifelong growth. Here we further report that using the newly developed DESC sphere culture method (9), it was found that FGF signaling was critical for the sphere forming capacity of the DESCs, which is normally used to evaluate the self-renewal activity of SCs (25–27). FGF2 promoted the sphere forming activity of the DESCs, and suppression of FGFR, MEK, and PI3K inhibited sphere formation and promoted differentiation of DESCs. In addition, inhibiting FGFR or its downstream signal transduction pathways diminished Lgr5-expressing cells in the CL without affecting label-retaining cells and disabled the activity of Wnt signaling in promoting Lgr5 expression in the CL and DESC spheres. As Lgr5 expression and label retention are widely used to mark active and slow-cycling SCs, respectively (28), the results suggest that FGF signaling is required for maintaining active cycling Lgr5+ DESCs. These studies provide new evidence for how FGF signaling regulates the self-renewal and differentiation of DESCs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All animals were housed in the Program for Animal Resources of the Institute of Biosciences and Technology at Texas A&M University and were handled in accordance with the principles and procedures of that institution's Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals; all experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The mice carrying Fgfr1flox, Fgfr2flox, Frs2αflox, Nkx3.1Cre, K5rtTA-H2BGFP, and Lgr5LacZ alleles were bred and genotyped as described (4, 29–33). Activation of tetracycline-regulated K5rtTA-H2BGFP expression was achieved by administration of regular chow containing 0.0625% doxycycline (Teklad, Harlan Laboratories).

Cell and Organ Culture

For tooth or CL organ culture, incisors were dissected from maxilla. The apical end of the incisors were further separated from the rest of other tissues and placed in a 24-well cell culture plate containing 1 ml of high glucose DMEM with l-glutamate (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 IU of penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. The tissues were cultured at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator for the time specified for each experiment. The Wnt3a conditioned medium or the control L-cell conditioned medium was collected according to the ATCC protocol. The medium conditioned either by Wnt3a-overexpressing or control L-cells was added to the culture medium at a ratio of 1:10; LiCl (100 ng/ml), NaCl (100 ng), and FGF1 (20 ng/ml) or FGF2 (20 ng/ml) was added as a supplement where indicated. An ERK inhibitor (SL327, EMD Millipore), PI3K inhibitor (LY294002, EMD Millipore), or FGFR inhibitor (341608, EMD Millipore) was added to the medium to a final concentration of 50 μm unless otherwise specified. For DESC sphere cultures, the CLs were dissected from postnatal day 7 (P7) pups and digested with dispase and collagenase to obtain single cell suspensions as described (9). The cells were resuspended in 50 μl of oral epithelial progenitor medium (CnT-24, CELLnTEC Advanced Cell Systems, Bern, Switzerland) and mixed with Matrigel (BD Biosciences) at a 1:1 ratio. About 0.1 ml of the cell/Matrigel mixture (containing 50,000 cells) was seeded around the rims of wells in a 12-well tissue culture plate and cultured in a CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 10–14 days. The aforementioned FGFR, ERK, and PI3K inhibitors were added to the medium to a final concentration of 10 μm or as otherwise specified. Adenovirus-GFP and adenovirus-GFP-Cre were purchased from the Vector Development Laboratory of the Baylor College of Medicine. The infections were carried out by incubating 3.2 × 1011 pfu/ml virus/1 × 106 cells at 37 °C for 16 h. The cells were then washed twice with PBS and cultured in oral epithelial progenitor medium (CnT-24) at 37 °C. At least three independent experiments with at least three samples in each group were performed. Representative whole-mount and section staining of the same experiments were shown.

Histology Analyses

DESC spheres were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution for 30 min at 4 °C. The dissected incisors, or the apical end of the incisors, which contains the CLs, were fixed in 4% PFA at 4 °C overnight. Fixed tissues were dehydrated serially with ethanol, embedded in paraffin, and completely sectioned according to standard procedures. Immunohistochemical analyses were performed on paraffin sections or frozen sections mounted on Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific). Antigen retrieval was performed by boiling samples in citrate buffer (10 mm) for 20 min or as suggested by the manufacturers. All sections were incubated at 4 °C overnight with primary antibodies diluted in PBS. The sources and concentrations of the primary antibodies were: rabbit anti-amelogenin (1:1000 for tissue section staining and 1:2000 for sphere and cell staining; a generous gift from Dr. Jan C. C. Hu, University of Michigan School Dentistry), mouse anti-CK14 (1:400 for tissue section and cells), and anti-phosphohistone H3 (1:500, from Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Specifically bound antibodies were detected with FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) and visualized on a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope. For LacZ staining, the dissected incisors or CLs were first fixed lightly with 0.2% glutaraldehyde for 45 min and then incubated overnight with 1 mg/ml X-Gal at room temperature. After washing with PBS for 10 min, the tissues were post-fixed with 4% PFA for 1 h, dehydrated, and paraffin-embedded for subsequent analyses. The dissected CLs were completely sectioned, and the most intensive LacZ-stained sections are shown.

Quantitative RT-PCR Analyses

Total RNA was extracted from freshly dissected or in vitro cultured tissues with the RiboPure kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). Reverse transcription was carried out with SuperScript III enzymes (Invitrogen) and random primers according to the manufacturer's protocols. Real-time PCR was carried out with the SYBR Green RT-PCT kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) or TaqMan gene expression assays (Invitrogen) with pairs of primers specific for each transcript and following the manufacturer's protocol. Relative mRNA abundance was calculated using the comparative threshold (CT) cycle method and normalized with β-actin. Data derived from at least three independent experiments are expressed as -fold difference between experimental and control samples. The primer sequences are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Nucleotide sequences of primers

| Genes | Primers |

|---|---|

| Lgr5 | 5′-CCTCTGCTTCCTAGAAGAGTTAC-3′ |

| 5′-CTAGTTCCTTAAGGTTGGAGAGT-3′ | |

| CK14 | 5′-GACTTCCGGACCAAGTTTGA-3′ |

| 5′-CTTGAGGCTCTCAATCTGC-3′ | |

| Amg | 5′-CCTGCCTCCTGGGAGCAGCTT-3′ |

| 5′-CACGGGCTGTTGAGCTGGCA-3′ | |

| FRS2α | 5′-GAGCTGGAAGTCCCTAGGACACCT-3′ |

| 5′-GCTCTCAGCATTAGAAACCCTTGC-3′ | |

| β-Actin | 5′-GCACCAAGGTGTGATGGTG-3′ |

| 5′-GGATGCCACAGGATTCCATA-3′ | |

| Wnt3a | 5′-CGATCTGGTGGTCCTTGGCTGT-3′ |

| 5′-AGCGGAGGCGATGGCATGGA-3′ | |

| Wif1 | 5′-GCTGCGGGGCAGGCAGAATAC-3′ |

| 5′-TCGACACCCTCCGGGACACTC-3′ | |

| sFRP1 | 5′-GCCTCTAAGCCCCAAGGTACAACC-3′ |

| 5′-TTGTCCAGCTGGTGGCAGGGA-3′ | |

| sFRP4 | 5′-GAGCCTGGCCTGCGATGAGC-3′ |

| 5′-TTGCACCGATCAGGGCTCAGAC-3′ | |

| Dkk1 | 5′-GGCACGCTATGTGCTGCCCC-3′ |

| 5′-GCAGACGGAGCCTTCTTGTCCTTTG-3′ | |

| FGFR2IIIb | 5′-GCACTCGGGGATAAATAGCTC-3′ |

| 5′-TGTTACCTGTCTCCGCAG-3′ | |

| FGFR2IIIc | 5′-AGCTGCCGGTGTTAACACCAC-3′ |

| 5′-TGTTACCTGTCTCCGCAG-3′ | |

| FGFR1IIIb | 5′-AGCATCAACCACACCTACCAGCT-3′ |

| 5′-GGAGAGTCCGATAGAGTTACCCG-3′ | |

| FGFR1IIIc | 5′-TGAGCCACGCAGACTGGTTA-3′ |

| 5′-GGAGAGTCCGATAGAGTTACCCG-3′ | |

| Axin2 | 5′-TTCCTGACCAAACAGACGACGAAG-3′ |

| 5′-TAACATCCACTGCCAGACATCCTG-3′ |

Western Blotting Analysis

Dissected CLs or cultured cells were homogenized in lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100/PBS) with 1 mm PMSF and a 1:100 dilution of proteinase inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor mixture I and II (Sigma). The protein extracts were harvested by centrifugation. Western blot analyses were done as described previously (34). Rabbit anti-ERK (1:3,000), rabbit anti-pERK (1:3,000), rabbit anti-amelogenin (1:2,000), and mouse anti-β-actin (1:3,000) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Rabbit anti-AKT (1:1000) and anti-pAKT (1:1000) were from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA). The intensity of bands was quantitated by using NIH ImageJ software.

TUNEL Assays

For TUNEL assays, spheres were fixed with 4% PFA for 30 min, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned. Apoptotic cells in the sections were detected with the DeadEnd Fluorometric TUNEL system from Promega (Madison, WI).

Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting Analysis

Dissociated DESCs were labeled with allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-CD49f (integrin α6) (BioLegend; clone GoH3, 20 μl/100 ul) or anti-CD44 (eBioscience; clone IM7, 1 mg/ml). Antibody labeling was conducted by a 20-min incubation at 4 °C with cell sorting buffer (1× PBS and 2% FBS) containing antibodies at the manufacturer's suggested dilution in a volume of 100 μl/1 million cells. The cells were washed in 1 ml of cold cell sorting buffer, resuspended in 0.5 ml of cell sorting buffer, and analyzed. Dissociated K5-H2BGFP CLs were resuspended in cell sorting buffer for analysis. Analyses were conducted on a BD FACSAria I (Special Order Research Product program) or BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer, and a minimum of 10,000 cells was acquired for each experimental condition. Proper isotype controls were used according to the manufacturer's suggestions.

Statistical Analyses

Western blots were scanned for quantitation with the ImageJ software. All quantitative data were expressed as the means ± S.D. from three independent experiments. A t test was used to determine whether the differences were statistically significant, and p values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

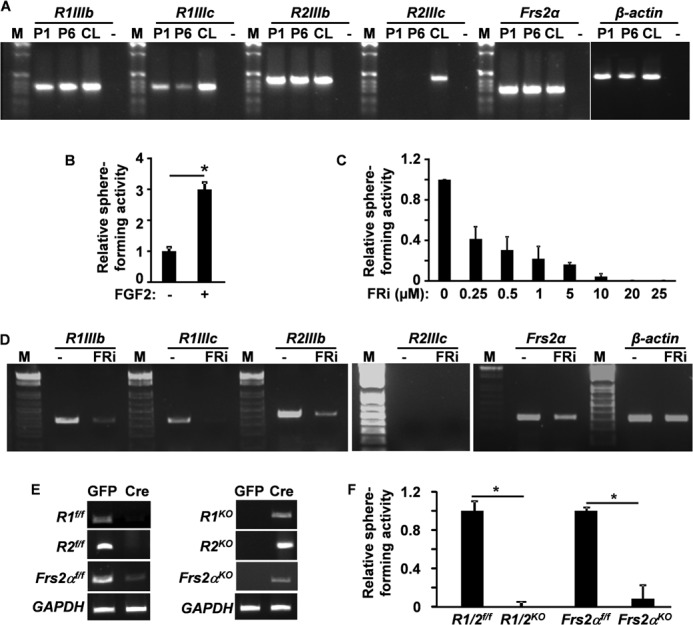

FGF Signaling in DESCs Is Required for Sphere Formation and Prevents Differentiation of the Cells

FGF signaling plays a role in SC self-renewal and differentiation (35–38). We first employed RT-PCR analyses to characterize the expression of Fgfr genes in the CLs and in DESC spheres (Fig. 1A). The results revealed that both the IIIb and IIIc isoforms of Fgfr1 and Frs2α were expressed in the CLs and in DESC spheres. The IIIb isoform of Fgfr2 was expressed in both CLs and DESC spheres; however, the IIIc isoform of Fgfr2 was detectable only in the CLs. To investigate the role of FGF signaling in DESCs, the cells were cultured in Matrigel for sphere formation analyses as described (9) with or without supplementation with FGF2, at a final concentration of 5 ng/ml. The sphere forming efficiency of DESCs grown in the presence of FGF2 was about 3 times that of those grown in the absence of FGF2 (Fig. 1B). Because low levels of endogenous FGFs from cells or Matrigel might contribute to sphere forming activity, an FGFR inhibitor (341608) was added to the medium to block FGF signaling in order to reveal the role of FGF signaling in DESCs. The results showed that the FGFR inhibitor suppressed sphere forming activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, the expression of Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 in DESC spheres was significantly reduced by FGFR inhibitor at a dose of 1 μm (Fig. 1D), implying an autoregulatory mechanism of FGF signaling in DESC spheres. To determine whether FGFR1, FGFR2, and FRS2α were required for sphere forming activity, DESCs bearing floxed Fgfr1, Fgfr2, or Frs2α alleles were infected with adenovirus-Cre virus to ablate Fgfr1, Fgfr2, or Frs2α (Fig. 1E). The results showed that ablation of either Fgfr1 or Fgfr2 only partially affected the sphere forming activity of DESCs (data not shown). However, double ablation of Fgfr1 and Fgfr2, or ablation of Frs2α, abrogated the sphere forming activity of DESCs (Fig. 1F). Infecting the cells with GFP-bearing adenovirus did not inhibit the sphere forming activity of DESCs, indicating that virus infection per se did not affect the self-renewal activity of DESCs (Fig. 1F). The results suggest that FGFR1 and FGFR2 redundantly regulate the sphere forming activity of DESCs.

FIGURE 1.

FGF signaling in DESCs is required for sphere forming activity. A, RT-PCR analyses of FGFR isoform expression in DESC spheres and CLs. B and C, CL cells dissected from postnatal day 7 pups were inoculated in Matrigel in the presence or absence of 5 ng/ml FGF2 or FGFR inhibitors at the indicated concentrations. Sphere numbers were assessed and presented as the relative sphere forming index with the non-FGF-treated group in B and the DMSO-treated group in C, respectively, as 1. D, RT-PCR analyses of Fgfr1 or Fgfr2 expression in DESC spheres treated with FGFR inhibitors. E, genotyping showing in vitro ablation efficiencies of adenovirus-GFP-Cre (Cre column). Adenovirus-GFP (GFP column) was used as a negative control. F, sphere forming activities of adenovirus-treated CL cells bearing the indicated alleles. Data are means ± S.D. of triplicate samples. R1f/f, R2f/f, Frs2αf/f, indicate floxed Fgfr1, Fgfr2, and Frs2α alleles; R1KO, R2KO, Frs2αKO, indicate Fgfr1, Fgfr2, and Frs2α conditional knock-out alleles; R1/2f/f, indicates Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 double foxed alleles; R1/2KO, indicates Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 double conditional knock-out alleles; R1IIIb, FGFR1IIIb isoform; R1IIIc, FGFR1IIIc isoform; R2IIIb, FGFR2IIIb isoform; R2IIIc, FGFR2IIIc isoform; P1 and P6, passages 1 and 6 of DESC spheres; FRi, FGFR inhibitor 341608; −, no RT for negative control; M, DNA molecular weight markers; *, p < 0.05.

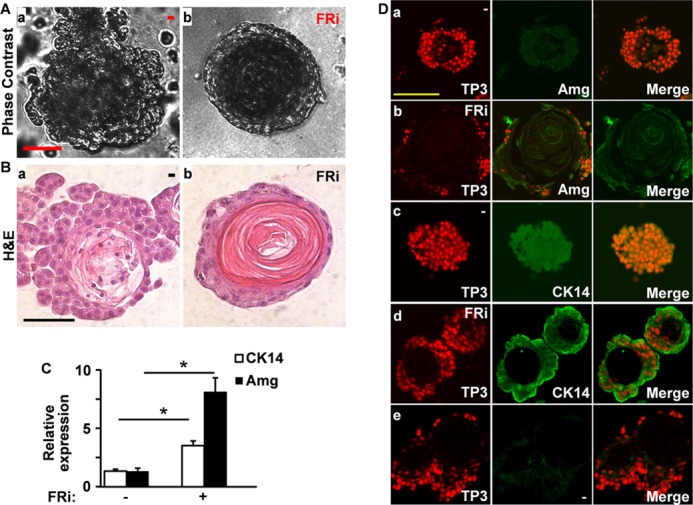

To further investigate the role of FGF signaling in regulating DESC sphere formation and differentiation, we then cultured DESC spheres in the presence or absence of FGFR inhibitors at a final concentration of 1 μm. At this intermediate concentration, the DESCs were viable and still formed spheres at a low efficiency. Phase contrast microscopy and H&E staining of sphere sections revealed that the DESC spheres formed a prominent, concentric, noncellular structure in the presence of FGFR inhibitors (Fig. 2, A and B). Real-time RT-PCR analyses demonstrated that expression of the differentiation markers, amelogenin and CK14, was increased in the FGFR inhibitor-treated groups (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, immunostaining revealed that suppression of FGFR activity significantly increased amelogenin and CK14 expression in the spheres (Fig. 2D). These results suggest that suppressing FGF signaling inhibits sphere formation and promotes differentiation of DESCs. Together, the results indicate that FGF signaling is required to maintain self-renewal and prevent the differentiation of DESCs.

FIGURE 2.

FGF signaling in DESCs is required to prevent differentiation. A, phase contrast images of DESC sphere untreated or treated with 1 μm FGFR inhibitors as indicated. B, H&E-stained section of paraffin-embedded DESC spheres cultured in the presence or absence of 1 μm FGFR inhibitors as indicated, showing the sphere morphology. C, real-time RT-PCR analyses of amelogenin (Amg) and CK14 in DESC spheres with or without FGFR inhibitor treatment. D, sections of paraffin-embedded DESC spheres were immunostained with antibodies against amelogenin or CK14. Data were normalized to β-actin housekeeping genes with DMSO groups as 1. FRi, FGFR inhibitor 341608. *, p < 0.05. TP3, To-PRO-3 staining; FRi, FGFR inhibitor 341608.

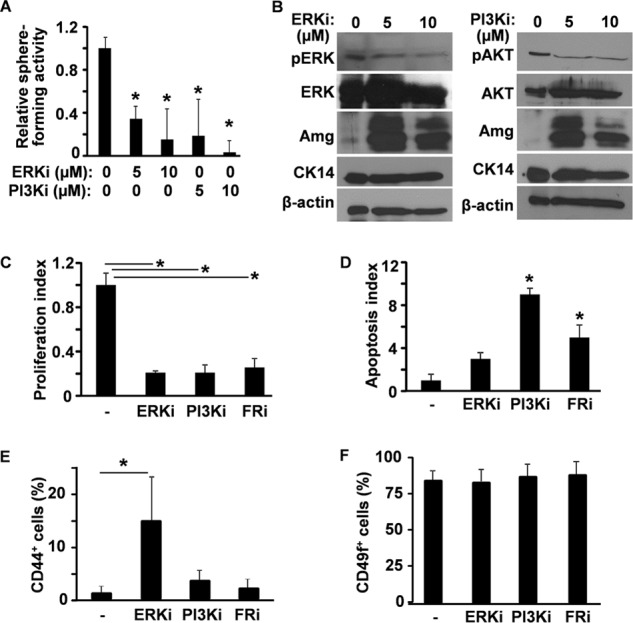

Both MAPK and AKT Pathways Are Required for Sphere Formation in DESCs

MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways are the two major downstream transducers in the FGF signaling cascade. To determine whether the MAPK or PI3K pathways are required for the sphere forming ability of DESCs, DESC sphere cultures were treated with either an ERK inhibitor (SL327) or a PI3K inhibitor (LY294002). Similar to FGFR inhibitors, both the ERK and the PI3K inhibitor suppressed the sphere forming activity of DESCs in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A). Western blot analyses revealed that suppressing either the ERK or PI3K pathway significantly increased amelogenin expression in DESC spheres (Fig. 3B). The expression level of amelogenin was reduced in the presence of a high dose of either the ERK or PI3K inhibitor, likely due to increased cell death occurring under such conditions. The data were consistent with results showing that treating the DESC spheres with FGFR inhibitors increased DESC differentiation (Fig. 1), indicating that both pathways were required for FGFR to prevent differentiation of DESCs. In addition, the number of phosphorylated histone H3-positive cells was significantly reduced by treating the cells with FGFR, ERK, or PI3K inhibitor, indicating that the treatments reduced cell proliferation in DESC spheres (Fig. 3C). TUNEL assays further revealed that apoptosis in DESC spheres was increased by suppressing the PI3K and FGFR kinase activities (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, inhibiting ERK, but not PI3K or FGFR kinase, significantly increased the CD44+ cell population, which likely represented progenitors for ameloblasts (Fig. 3E), although no obvious difference was detected in the CD49f (integrin α6)+ population using the same treatment (Fig. 3F). Together, the results suggest that both the ERK and PI3K pathways promote DESC proliferation and prevent DESC differentiation, whereas the PI3K pathway also prevents cells from undergoing apoptosis.

FIGURE 3.

Both the ERK and PI3K pathways are required to maintain the sphere forming activity of DESCs. A, cells from postnatal day 7 CLs were inoculated in Matrigel in the presence or absence of inhibitors to ERK or PI3K at the indicated concentrations. Sphere numbers were assessed and presented as the relative sphere forming index using the untreated group as 1. B, DESC spheres were cultured in the presence of ERK or PI3K inhibitors at the indicated concentrations for 14 days, and the expressions of amelogenin (Amg) and CK14 were assessed by Western blot analyses. β-Actin was used as an internal loading control. C and D, DESC spheres were cultured in the presence or absence of ERK, PI3K, or FGFR inhibitors for 14 days. Cell proliferation (C) and apoptosis (D) were assessed by immunostaining of phosphorylated histone H3 and TUNEL assay, respectively. E and F, ratios of CD49f (integrin α6)- or CD44-expressing cells were assessed by fluorescence-assisted cell sorting. Data are means ± S.D. of triplicate samples. ERKi, ERK inhibitor SL327; PI3Ki, PI3K inhibitor LY294002; FRi, FGFR inhibitor 341608; pERK, phosphorylated ERK; pAKT, phosphorylated AKT. *, p < 0.05.

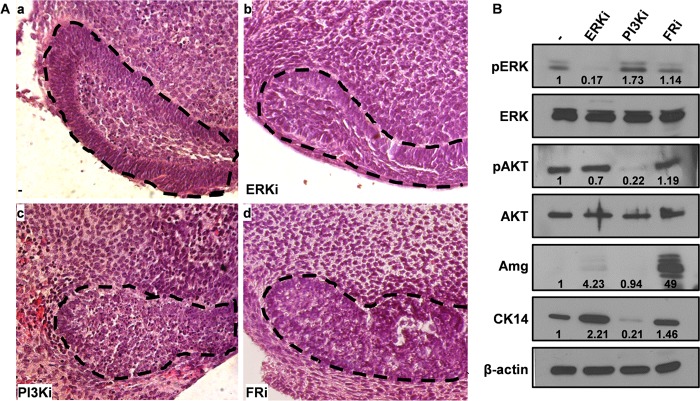

Blocking FGF Signaling Promotes Cell Differentiation in the CL

We reported previously that ablation of Fgfr2 in the tooth epithelium leads to diminishment of the CL (13). To further study the roles of FGFR and its two major downstream pathways in the CL, the CL was dissected from incisors at the P7 stage for ex vivo tissue culture analyses. Treatment with the PI3K or FGFR inhibitors significantly disrupted the morphology of the CL (Fig. 4A). Unlike the DMSO-treated control group, where the epithelial cells were polarized and well aligned to form a CL, the epithelial cells in the PI3K or FGFR inhibitor-treated groups were poorly organized and the boundary between epithelial and stromal cells was poorly defined. Western blot analyses revealed that inhibiting ERK, but not PI3K, significantly increased expression of the epithelial marker CK14 (Fig. 4B). Treatment with the FGFR inhibitor significantly enhanced expression of amelogenin, the characteristic ameloblast matrix protein (Fig. 4B). Notably, suppressing the FGFR kinase only lightly impacted the activation of ERK and PI3K, likely due to the existence of multiple upstream activators of ERK and PI3K in the CL. Because the effects of these inhibitors were different in CL organ cultures and DESC sphere cultures, a more detailed characterization is needed for resolving this discrepancy. Possible factors include the existence of both epithelial and mesenchymal components in the CL organ cultures, different media used in CL organ and DESC sphere cultures, and the short CL organ culture time (3 days) compared with the DESC sphere culture (10–14 days).

FIGURE 4.

FGF signaling is required to maintain the integrity of the CL. A, incisors were cultured in the presence of the indicated inhibitors for 3 days using DMSO as the solvent control. H&E staining of paraffin sections shows distorted CLs in the inhibitor-treated group. Dotted lines outline the CL. ERKi, ERK inhibitor SL327; PI3Ki, PI3K inhibitor LY294002; FRi, FGFR inhibitor 341608. B, Western blot analyses demonstrate that amelogenin (Amg) expression in the CL was induced by FGFR inhibitors. β-Actin was used as an internal loading control. Numbers indicate quantitative analyses of the bands using NIH ImageJ.

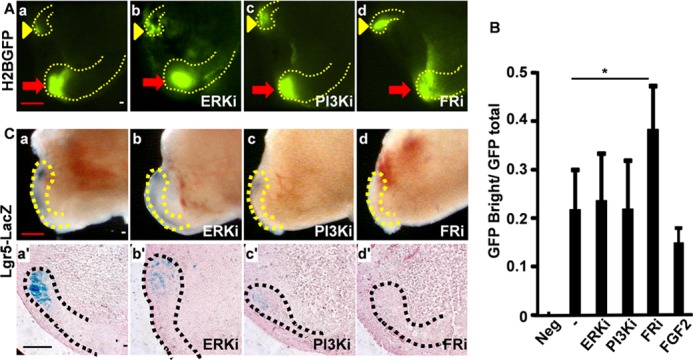

Blocking FGF Signaling Increases Slow-cycling Cells but Diminishes Lgr5-expressing Cells in the CL

To further investigate whether inhibiting FGF signaling affected slow-cycling or Lgr5-expressing cells in the CL, mice bearing the K5rtTA-H2BGFP reporter allele were treated with doxycycline to inactivate H2BGFP expression for 7 days. The teeth were then dissected and cultured in the presence of doxycycline to continue blocking H2BGFP expression. As the abundance of H2BGFP was reduced after each cell division, the quiescent cells would remain GFPBright, the fast-cycling cells would be GFP-negative, and the slow-cycling cells would be somewhat GFP-positive. Treating the tooth cultures with inhibitors of ERK, PI3K, or FGFR kinase did not affect the presence of H2BGFP-retaining cells in the CL region (Fig. 5A), suggesting that suppressing these pathways did not reduce slow-cycling DESCs. However, flow cytometry analyses revealed that the ratio of GFPBright (representing slow-cycling cells) to total GFP+ cells was increased, suggesting that inhibiting FGFR signaling prevented slow-cycling cells from entry into the cell cycle in the CL (Fig. 5B). Treatment with FGF2 somewhat reduced the ratio, although statistical significance was lacking because of the large variation in the nature of the assay methods. On the other hand, treating the cultured teeth bearing the Lgr5LacZ reporter allele with ERK, PI3K, or FGFR inhibitors diminished Lgr5LacZ-expressing cells in the CL, suggesting that these signaling pathways were important for the maintenance of Lgr5-expressing cells in the CL (Fig. 5C).

FIGURE 5.

Blocking FGF signaling increases slow-cycling cells but diminishes Lgr5-expressing cells in the CL. A, the incisors dissected from postnatal day 28 K5-H2BGFP mice after doxycycline treatment for 7 days were cultured in the presence of the indicated inhibitors and tetracycline for 3 days. The H2BGFP-retaining cells in the CL region were visualized under a fluorescent microscope. Red arrows indicate labial CLs; yellow arrowheads indicate lingual CLs. ERKi, ERK inhibitor SL327; PI3Ki, PI3K inhibitor LY294002; FRi, FGFR inhibitor 341608. B, the GFP-expressing cells were analyzed with a fluorescence-assisted cell sorter. The ratio of GFPBright to total GFP+ cells was presented. Data are means ± S.D. of seven samples. C, whole-mount LacZ staining of teeth cultured in the presence of the indicated inhibitors demonstrates the Lgr5LacZ-expressing DESCs in the CLs (upper panels). Lower panels, sections of the same whole-mount LacZ-stained tissues. a′–d′ are sections of the same tissues shown in a–d. The dotted lines outline the CLs. *, p < 0.05.

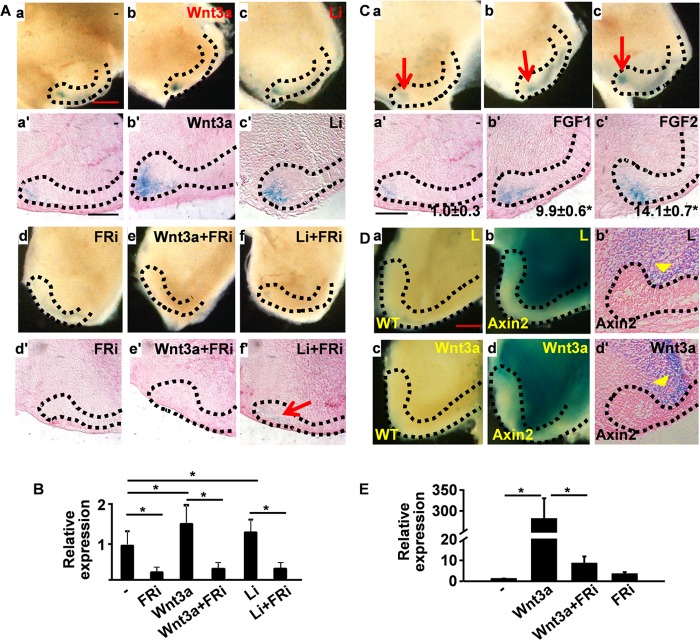

FGF Signaling Is Required for Wnt Signaling to Up-regulate Lgr5 Expression in the CL

Lgr5 is a target gene of the Wnt signaling pathway in multiple organs, including the small intestine, hair follicles, and cochlea (3, 39, 40). Consistently, expression of the Lgr5LacZ reporter in the CL was up-regulated by treatment with Wnt3a-enriched conditioned medium or LiCl, a commonly used Wnt signaling activator (Fig. 6A), but not by the medium conditioned by nontransfected L-cells or NaCl. As FGFR inhibitors diminished Lgr5LacZ expression in the CL, we then further investigated whether inhibition of FGFR would abrogate the activity of Wnt signaling to enhance Lgr5 expression. The results clearly demonstrated that activation of Lgr5LacZ expression by either Wnt3a or LiCl was blocked by FGFR inhibitors. However, residual Lgr5LacZ expression was still noticeable in the LiCl- and FGFR inhibitor-treated CL (Fig. 6A). In line with the Lgr5LacZ reporter assays, treating the ex vivo cultured CLs with the Wnt3a-enriched conditioned medium or LiCl increased endogenous Lgr5LacZ expression at the mRNA level (Fig. 6B). Moreover, both FGF1 and FGF2 promoted expression the Lgr5LacZ reporter in the CL (Fig. 6C). Together, the results suggest that FGF pathway is required for the Wnt pathway to activate Lgr5 expression in the CL of ex vivo cultured tooth. However, whether Wnt signaling regulated Lgr5 expression in the CL cells either directly or indirectly mediated by the stromal cells adjacent to the CL remained unknown. To address the issue, ex vivo cultures of incisors carrying the Wnt signaling reporter allele Axin2LacZ were used to track cells that had Wnt signaling activity. Similar to previous reports (7, 18), Axin2LacZ expression was not detected in the dental epithelium (Fig. 6D). However, the stromal cells in both control and Wnt3a-treated samples were highly LacZ-positive. The Wnt3a-treated samples appeared to have more intensive staining than that of the controls (Fig. 6D). Quantitative RT-PCR analyses further demonstrated that Wnt3a treatment significantly increased Axin2 expression (Fig. 6E). The results suggest that the regulation of Lgr5 expression by Wnt3a in the CL is likely mediated by stromal factors.

FIGURE 6.

FGF signaling is required for the Wnt pathway to up-regulate Lgr5 expression. A, whole-mount LacZ staining of teeth cultured in the presence or absence of Wnt3a, LiCl, or FGFR inhibitor (FRi) as indicated. a′–f′ are sections of the same tissues shown in a–f. B, total RNA was extracted from the CL regions cultured in the presence or absence of Wnt3a, LiCl, or FGFR inhibitor as indicated for RT-PCR analyses of endogenous Lgr5 expression. C, whole-mount LacZ staining of teeth cultured in the presence or absence of FGF1 or FGF2 as indicated. a′–c′ are sections of the same tissues shown in a–c. The areas and intensities of LacZ staining in all sections were quantitated by NIH ImageJ. The data were normalized to the untreated group and expressed as -fold increase. Numbers in a′–c′ are means ± S.D. of two replicated samples. D, whole-mount LacZ staining of teeth bearing the Axin2LacZ reporter allele cultured in the presence of control (L, L-cell) or Wnt3a-conditioned medium. b′ and d′ are sections of the same tissue shown in b and d. Arrowheads indicate the LacZ+ stromal tissues. Representative data from three independent experiments are shown. E, total RNA was extracted from the CL regions cultured in the presence or absence of Wnt3a or FGFR inhibitor as indicated for RT-PCR analyses of axin2 expression. The dotted lines outline the CLs. *, p < 0.05. Data are means ± S.D. of triplicate samples.

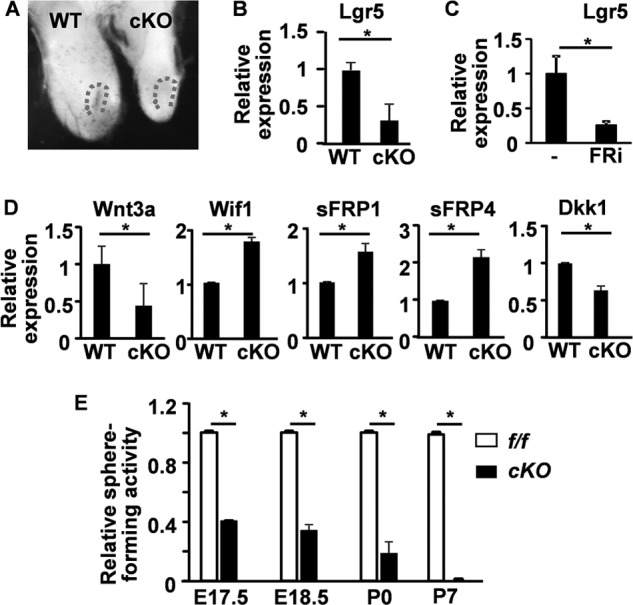

Ablation of Fgfr2 in the tooth epithelium with Nkx3.1Cre diminishes the CL (13). Consistently, Lgr5LacZ expression in the Fgfr2 conditional knock-out CL was dramatically reduced (Fig. 7A). Real-time RT-PCR analyses demonstrated that endogenous Lgr5 expression in the Fgfr2 mutant CL areas was reduced to 30% of that in the wild type control (Fig. 7B), which was consistent with the decreased Lgr5 expression in spheres treated with FGFR inhibitor (Fig. 7C). Interestingly, expression of several inhibitors of the Wnt receptor Frizzled, including sFRP1, sFRP4, and Wif1, was increased in Fgfr2 mutant CLs (Fig. 7D). However, expression of Wnt3a was reduced in Fgfr2 mutant CLs. Of further note was the expression of Dkk1, an Lrp5/6 inhibitor, which was reduced in Fgfr2 mutant CLs. Interestingly, the changes in expression of these genes were less than 2-fold, implying that Wnt signaling in the CL was delicately regulated. Together, the results indicated that the Wnt signaling pathway is suppressed in Fgfr2 mutant CLs. Cells isolated from the CL regions of Fgfr2 mutant had a significantly decreased sphere forming activity under the same conditions over time (Fig. 7E), indicating a decrease in DESCs in the degenerated CL of Fgfr2 mutant incisors.

FIGURE 7.

Ablation of Fgfr2 suppresses Wnt signaling in the CLs. A, whole-mount LacZ staining showing Lgr5LacZ expression in the CL at postnatal day 0. Dotted lines indicate the CL. B–D, total RNAs extracted from the CL regions (B and D) at postnatal day 0 or DESC spheres (C) untreated or treated with 1 μm FGFR inhibitors were subjected to RT-PCR analyses of the indicated genes. E, sphere forming analyses of the CL cells harvested at the indicated stages. Data are means ± S.D. of triplicate samples. f/f, homozygous Fgfr2 floxed alleles; cKO, Fgfr2 conditional knock-out with Nkx3.1Cre; WT, wild type Fgfr2 alleles; E, embryonic; P, postnatal. *, p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Progress in studying the isolation and propagation of DESCs has been slow due to lack of reliable surface markers suitable for identifying and enriching DESCs, as well as the limited understanding of the molecular mechanisms governing DESC self-renewal and differentiation. Herein, we report, using newly developed methods of sphere culture, identification, and enrichment of DESCs (9), that FGF signaling is critical for maintaining the sphere forming capacity of DESCs and the homeostasis of Lgr5-expressing DESCs. Suppressing FGF signaling by inhibiting either FGFR kinase activity or its two major downstream pathways, ERK and PI3K, induced differentiation, decreased proliferation, and increased apoptosis in DESC spheres. Interestingly, inhibiting FGF signaling did not exhaust slow-cycling DESCs but diminished Lgr5 expression in the CL. In addition, inhibiting FGFR or its downstream ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways also diminished Lgr5 expression in the CL. It abrogated the activities of Wnt signaling to promote Lgr5 expression in the CL both in vivo and in vitro. As sphere forming capacity is normally used to evaluate the self-renewal activity of SCs, label retention for slow-cycling SCs, and Lgr5 expression for active cycling SCs (25–28), our results reveal that FGF signaling is required for maintaining active DESCs in the CL and preventing DESC differentiation.

Mouse incisors are organs that grow continuously through life and thus, require a constant supply of dental epithelial cells derived from DESCs residing in the CL. FGF signaling constitutes a reciprocal regulatory communication loop between the epithelial and mesenchymal compartments regulating tooth formation and regeneration (10–14). The FGF10-FGFR2IIIb signaling axis has been proposed as essential for the CL (5, 11). We reported previously that ablation of Fgfr2 in the tooth epithelium causes loss of the CL in maxillary incisors, likely due to loss of active DESCs in the CL (13). Our data here further demonstrate that FGF signaling is required for maintaining Lgr5-expressing but not label-retaining DESCs. This finding is consistent with the data that the sphere forming units were reversibly reduced by treatment with FGFR inhibitors and supports the report that expression of a dominant negative FGFR2 construct in postnatal tooth epithelial cells reversibly suppresses mouse incisor growth (14).

Suppressing FGFR kinase activity only slightly reduced the activation of ERK or PI3K (Fig. 4B), suggesting that both ERK and PI3K/AKT have multiple upstream regulatory pathways in the CL. Interestingly, suppressing the ERK pathway increased CK14 and amelogenin expression, whereas PI3K inhibition blocked the expression. However, suppressing FGFR kinase only slightly increased CK14 expression, whereas it dramatically increased amelogenin expression (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that activation of these two pathways favors commitment of different lineages and that FGFR signaling inhibits ameloblast differentiation either via combinatory effects of the two pathways or other pathways independent of ERK and PI3K. Further rigorous characterization is needed to clarify this issue.

Wnt are secreted ligands that elicit receptor-mediated signals regulating the development, regeneration, and maintenance of progenitor cell pools, both via the canonical β-catenin-dependent and non-canonical β-catenin-independent pathways (41–47). Although it plays essential roles in early tooth development (48–50), the role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in DESC maintenance and differentiation is controversial. In situ hybridization experiments show that DESCs do not have the active Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (7), which is confirmed by using the three classic Wnt/β-catenin signaling reporters TOPGAL, BATGAL, and Axin2 in mice (18). However, expression of constitutively active β-catenin (51–53) or ablation of adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), a Wnt/β-catenin inhibitor (54), consistently demonstrates that activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the odontogenic epithelium, at either the embryonic or postnatal stages, results in generation of supernumerary teeth. In addition, lizards and snakes, which also have life-long tooth growth activity, also exhibit strong Wnt signals in DESCs (55, 56). Moreover, multiple Wnt signaling inhibitors are expressed in the CL region (18). These results suggest the importance and tight regulation of Wnt signaling in DESC homeostasis. Consistently, recent reports show that FGF8 is required to maintain Sox2+ SCs in the CL (18) and is a direct target gene of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the dental epithelium (54). Our data further demonstrate the cross-talk between the Wnt and FGF pathways in regulating DESC homeostasis.

In summary, we report here that FGF signaling prevents differentiation and promotes the self-renewal and survival of DESCs. This study suggests a novel mechanism for manipulating the maintenance, expansion, and differentiation of DESCs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Allan Prejusa and Jonathan Lei for FACS cell sorting and data analysis; Drs. Juha Patanen and David Ornitz, Elaine Fuchs, Adam Glick, Hans Clevers, and Michael M. Shen for generously sharing the Fgfr1-floxed, Fgfr2-floxed, H2B-GFP, K5rtTA, Lgr5LacZ, and Nkx3.1Cre mice, respectively; and Dr. Stefan Siwko for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants K08DE020883 (to J. Y. F. C.), T32DE018380 (R. N. D.), CA096824 (to F. W.), and CA140388 (to W. L. M. and F. W.). This work was also supported by the John S. Dunn Research Foundation (to W. L. M.) and the Cancer Prevention and Research Institution of Texas Grant CPRIT 110555 (to F. W. and W. L. M.).

- SC

- stem cell

- CL

- cervical loop

- DESC

- dental epithelial stem cell

- FGFR

- fibroblast growth factor receptor

- PFA

- paraformaldehyde

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- CK14

- cytokeratin 14.

REFERENCES

- 1. Li L., Xie T. (2005) Stem cell niche: structure and function. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 605–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moore K. A., Lemischka I. R. (2006) Stem cells and their niches. Science 311, 1880–1885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barker N., van Es J. H., Kuipers J., Kujala P., van den Born M., Cozijnsen M., Haegebarth A., Korving J., Begthel H., Peters P. J., Clevers H. (2007) Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature 449, 1003–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tumbar T., Guasch G., Greco V., Blanpain C., Lowry W. E., Rendl M., Fuchs E. (2004) Defining the epithelial stem cell niche in skin. Science 303, 359–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Harada H., Kettunen P., Jung H. S., Mustonen T., Wang Y. A., Thesleff I. (1999) Localization of putative stem cells in dental epithelium and their association with Notch and FGF signaling. J. Cell Biol. 147, 105–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Seidel K., Ahn C. P., Lyons D., Nee A., Ting K., Brownell I., Cao T., Carano R. A., Curran T., Schober M., Fuchs E., Joyner A., Martin G. R., de Sauvage F. J., Klein O. D. (2010) Hedgehog signaling regulates the generation of ameloblast progenitors in the continuously growing mouse incisor. Development 137, 3753–3761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Suomalainen M., Thesleff I. (2010) Patterns of Wnt pathway activity in the mouse incisor indicate absence of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the epithelial stem cells. Dev. Dyn. 239, 364–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tucker A., Sharpe P. (2004) The cutting edge of mammalian development; how the embryo makes teeth. Nat. Rev. Genet. 5, 499–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chang J. Y., Wang C., Jin C., Yang C., Huang Y., Liu J., McKeehan W. L., D'Souza R. N., Wang F. (2013) Self-renewal and multilineage differentiation of mouse dental epithelial stem cells. Stem Cell Res. 11, 990–1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kettunen P., Laurikkala J., Itäranta P., Vainio S., Itoh N., Thesleff I. (2000) Associations of FGF-3 and FGF-10 with signaling networks regulating tooth morphogenesis. Dev. Dyn. 219, 322–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harada H., Toyono T., Toyoshima K., Yamasaki M., Itoh N., Kato S., Sekine K., Ohuchi H. (2002) FGF10 maintains stem cell compartment in developing mouse incisors. Development 129, 1533–1541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Klein O. D., Lyons D. B., Balooch G., Marshall G. W., Basson M. A., Peterka M., Boran T., Peterkova R., Martin G. R. (2008) An FGF signaling loop sustains the generation of differentiated progeny from stem cells in mouse incisors. Development 135, 377–385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lin Y., Cheng Y. S., Qin C., Lin C., D'Souza R., Wang F. (2009) FGFR2 in the dental epithelium is essential for development and maintenance of the maxillary cervical loop, a stem cell niche in mouse incisors. Dev. Dyn. 238, 324–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Parsa S., Kuremoto K., Seidel K., Tabatabai R., Mackenzie B., Yamaza T., Akiyama K., Branch J., Koh C. J., Al Alam D., Klein O. D., Bellusci S. (2010) Signaling by FGFR2b controls the regenerative capacity of adult mouse incisors. Development 137, 3743–3752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McKeehan W. L., Wang F., Luo Y. (2009) The Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) Signaling Complex. Handbook of Cell Signaling, (Bradshaw R., Dennis E., eds.) 2nd Ed., pp. 253–259, Academic/Elsevier Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kettunen P., Thesleff I. (1998) Expression and function of FGFs-4, -8, and -9 suggest functional redundancy and repetitive use as epithelial signals during tooth morphogenesis. Dev. Dyn. 211, 256–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang X. P., Suomalainen M., Felszeghy S., Zelarayan L. C., Alonso M. T., Plikus M. V., Maas R. L., Chuong C. M., Schimmang T., Thesleff I. (2007) An integrated gene regulatory network controls stem cell proliferation in teeth. PLoS Biol. 5, e159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Juuri E., Saito K., Ahtiainen L., Seidel K., Tummers M., Hochedlinger K., Klein O. D., Thesleff I., Michon F. (2012) Sox2+ stem cells contribute to all epithelial lineages of the tooth via Sfrp5+ progenitors. Dev. Cell 23, 317–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kettunen P., Karavanova I., Thesleff I. (1998) Responsiveness of developing dental tissues to fibroblast growth factors: expression of splicing alternatives of FGFR1, -2, -3, and of FGFR4; and stimulation of cell proliferation by FGF-2, -4, -8, and -9. Dev. Genet. 22, 374–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Takamori K., Hosokawa R., Xu X., Deng X., Bringas P., Jr., Chai Y. (2008) Epithelial fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 regulates enamel formation. J. Dent. Res. 87, 238–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. De Moerlooze L., Spencer-Dene B., Revest J. M., Hajihosseini M., Rosewell I., Dickson C. (2000) An important role for the IIIb isoform of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) in mesenchymal-epithelial signalling during mouse organogenesis. Development 127, 483–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Klein O. D., Minowada G., Peterkova R., Kangas A., Yu B. D., Lesot H., Peterka M., Jernvall J., Martin G. R. (2006) Sprouty genes control diastema tooth development via bidirectional antagonism of epithelial-mesenchymal FGF signaling. Dev. Cell 11, 181–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Charles C., Hovorakova M., Ahn Y., Lyons D. B., Marangoni P., Churava S., Biehs B., Jheon A., Lesot H., Balooch G., Krumlauf R., Viriot L., Peterkova R., Klein O. D. (2011) Regulation of tooth number by fine-tuning levels of receptor-tyrosine kinase signaling. Development 138, 4063–4073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tummers M., Thesleff I. (2009) The importance of signal pathway modulation in all aspects of tooth development. J. Exp. Zool. B Mol. Dev. Evol. 312B, 309–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reynolds B. A., Rietze R. L. (2005) Neural stem cells and neurospheres: re-evaluating the relationship. Nat. Methods 2, 333–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dontu G., Abdallah W. M., Foley J. M., Jackson K. W., Clarke M. F., Kawamura M. J., Wicha M. S. (2003) In vitro propagation and transcriptional profiling of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Genes Dev. 17, 1253–1270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Xin L., Lukacs R. U., Lawson D. A., Cheng D., Witte O. N. (2007) Self-renewal and multilineage differentiation in vitro from murine prostate stem cells. Stem Cells 25, 2760–2769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li L., Clevers H. (2010) Coexistence of quiescent and active adult stem cells in mammals. Science 327, 542–545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Weng J., Luo J., Cheng X., Jin C., Zhou X., Qu J., Tu L., Ai D., Li D., Wang J., Martin J. F., Amendt B. A., Liu M. (2008) Deletion of G protein-coupled receptor 48 leads to ocular anterior segment dysgenesis (ASD) through down-regulation of Pitx2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 6081–6086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lin Y., Zhang J., Zhang Y., Wang F. (2007) Generation of an Frs2α conditional null allele. Genesis 45, 554–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Trokovic R., Trokovic N., Hernesniemi S., Pirvola U., Vogt Weisenhorn D. M., Rossant J., McMahon A. P., Wurst W., Partanen J. (2003) FGFR1 is independently required in both developing mid- and hindbrain for sustained response to isthmic signals. EMBO J. 22, 1811–1823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yu K., Xu J., Liu Z., Sosic D., Shao J., Olson E. N., Towler D. A., Ornitz D. M. (2003) Conditional inactivation of FGF receptor 2 reveals an essential role for FGF signaling in the regulation of osteoblast function and bone growth. Development 130, 3063–3074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Diamond I., Owolabi T., Marco M., Lam C., Glick A. (2000) Conditional gene expression in the epidermis of transgenic mice using the tetracycline-regulated transactivators tTA and rTA linked to the keratin 5 promoter. J. Invest. Dermatol. 115, 788–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhang Y., Zhang J., Lin Y., Lan Y., Lin C., Xuan J. W., Shen M. M., McKeehan W. L., Greenberg N. M., Wang F. (2008) Role of epithelial cell fibroblast growth factor receptor substrate 2α in prostate development, regeneration and tumorigenesis. Development 135, 775–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Levenstein M. E., Ludwig T. E., Xu R. H., Llanas R. A., VanDenHeuvel-Kramer K., Manning D., Thomson J. A. (2006) Basic fibroblast growth factor support of human embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Stem Cells 24, 568–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yu P., Pan G., Yu J., Thomson J. A. (2011) FGF2 sustains NANOG and switches the outcome of BMP4-induced human embryonic stem cell differentiation. Cell Stem Cell 8, 326–334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Levenstein M. E., Berggren W. T., Lee J. E., Conard K. R., Llanas R. A., Wagner R. J., Smith L. M., Thomson J. A. (2008) Secreted proteoglycans directly mediate human embryonic stem cell-basic fibroblast growth factor 2 interactions critical for proliferation. Stem Cells 26, 3099–3107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen G., Gulbranson D. R., Yu P., Hou Z., Thomson J. A. (2012) Thermal stability of fibroblast growth factor protein is a determinant factor in regulating self-renewal, differentiation, and reprogramming in human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells 30, 623–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Haegebarth A., Clevers H. (2009) Wnt signaling, lgr5, and stem cells in the intestine and skin. Am. J. Pathol. 174, 715–721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shi F., Kempfle J. S., Edge A. S. (2012) Wnt-responsive Lgr5-expressing stem cells are hair cell progenitors in the cochlea. J. Neurosci. 32, 9639–9648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Clevers H. (2006) Wnt/β-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell 127, 469–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hoppler S., Kavanagh C. L. (2007) Wnt signalling: variety at the core. J. Cell Sci. 120, 385–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ille F., Sommer L. (2005) Wnt signaling: multiple functions in neural development. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62, 1100–1108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nusse R. (2005) Wnt signaling in disease and in development. Cell Res. 15, 28–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stoick-Cooper C. L., Weidinger G., Riehle K. J., Hubbert C., Major M. B., Fausto N., Moon R. T. (2007) Distinct Wnt signaling pathways have opposing roles in appendage regeneration. Development 134, 479–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. van Amerongen R., Berns A. (2006) Knockout mouse models to study Wnt signal transduction. Trends Genet. 22, 678–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Veeman M. T., Axelrod J. D., Moon R. T. (2003) A second canon. Functions and mechanisms of β-catenin-independent Wnt signaling. Dev. Cell 5, 367–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fujimori S., Novak H., Weissenböck M., Jussila M., Gonçalves A., Zeller R., Galloway J., Thesleff I., Hartmann C. (2010) Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the dental mesenchyme regulates incisor development by regulating Bmp4. Dev. Biol. 348, 97–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chen J., Lan Y., Baek J. A., Gao Y., Jiang R. (2009) Wnt/β-catenin signaling plays an essential role in activation of odontogenic mesenchyme during early tooth development. Dev. Biol. 334, 174–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kratochwil K., Galceran J., Tontsch S., Roth W., Grosschedl R. (2002) FGF4, a direct target of LEF1 and Wnt signaling, can rescue the arrest of tooth organogenesis in Lef1(−/−) mice. Genes Dev. 16, 3173–3185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Järvinen E., Salazar-Ciudad I., Birchmeier W., Taketo M. M., Jernvall J., Thesleff I. (2006) Continuous tooth generation in mouse is induced by activated epithelial Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 18627–18632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Liu F., Chu E. Y., Watt B., Zhang Y., Gallant N. M., Andl T., Yang S. H., Lu M. M., Piccolo S., Schmidt-Ullrich R., Taketo M. M., Morrisey E. E., Atit R., Dlugosz A. A., Millar S. E. (2008) Wnt/β-catenin signaling directs multiple stages of tooth morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 313, 210–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Liu F., Dangaria S., Andl T., Zhang Y., Wright A. C., Damek-Poprawa M., Piccolo S., Nagy A., Taketo M. M., Diekwisch T. G., Akintoye S. O., Millar S. E. (2010) β-Catenin initiates tooth neogenesis in adult rodent incisors. J. Dent. Res. 89, 909–914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wang X. P., O'Connell D. J., Lund J. J., Saadi I., Kuraguchi M., Turbe-Doan A., Cavallesco R., Kim H., Park P. J., Harada H., Kucherlapati R., Maas R. L. (2009) Apc inhibition of Wnt signaling regulates supernumerary tooth formation during embryogenesis and throughout adulthood. Development 136, 1939–1949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Handrigan G. R., Leung K. J., Richman J. M. (2010) Identification of putative dental epithelial stem cells in a lizard with life-long tooth replacement. Development 137, 3545–3549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Handrigan G. R., Richman J. M. (2010) A network of Wnt, hedgehog, and BMP signaling pathways regulates tooth replacement in snakes. Dev. Biol. 348, 130–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]