Abstract

Background

Arginine vasopressin (AVP) levels are elevated in proportion to heart failure (HF) severity and are associated with higher cardiovascular mortality in ambulatory patients. However, the relationship between baseline and trends in AVP with outcomes in patients hospitalized for worsening HF with reduced ejection fraction (EF) is unclear.

Methods and Results

The EVEREST (Efficacy of Vasopressin Antagonism in Heart Failure Outcome Study with Tolvaptan) trial investigated the effects of tolvaptan in patients with worsening HF and EF≤40%. The present analysis examined baseline and follow-up AVP levels in 3,196 EVEREST patients with valid AVP measurements. Co-primary endpoints included all-cause mortality (ACM), and the composite of cardiovascular mortality or HF hospitalization (CVM/H). Median follow-up was 9.9 months. Times to events were compared with univariate log-rank tests and multivariable Cox regression models, adjusted for baseline risk factors. After adjusting for baseline covariates, elevated AVP levels were associated with increased ACM (hazard ratio [HR] 1.33, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.13 –1.55) and CVM/H (HR 1.23, 95% CI 1.08 –1.39). There was no interaction of baseline AVP with treatment assignment in terms of survival (p=0.515). Tolvaptan therapy increased the proportion of patients with elevated AVP (p<0.001), but this had no effect on mortality (HR 0.95, 95% CI 0.72 – 1.24).

Conclusions

Elevated baseline AVP level was independently predictive of mortality, but did not identify a group of patients who had improved outcomes with tolvaptan treatment. Tolvaptan treatment increased AVP levels during follow-up, but this incremental increase was not associated with worsened outcomes.

Keywords: heart failure, drugs, hormones, outcomes

Heart failure (HF) continues to be an enormous public health problem with over 670,000 new cases and 1 million hospitalizations annually in the United States alone.1 Neurohormonal activation, including increased levels of arginine vasopressin (AVP), is a hallmark of chronic HF2 and AVP levels have been correlated with disease severity3, 4 and increased cardiovascular mortality5. AVP is synthesized in the hypothalamus, stored in the posterior pituitary gland, and released by an increase in plasma osmolality and a variety of non-osmotic stimuli.6, 7 It interacts with several receptors including the V1a receptor on blood vessels and myocardium, and the V2 receptors in the kidney.8, 9 Important potential pathophysiologic effects of increased AVP levels include V1a-mediated vasoconstriction, myocellular protein synthesis, and V2-mediated water retention.10, 11

However, less is known regarding the importance of AVP levels in patients hospitalized with worsening HF and reduced ejection fraction (EF), particularly in the setting of contemporary neurohormonal-blocking therapies. Moreover, to what extent AVP activity is maladaptive in HF is still unresolved. Antagonism of the renal V2 receptors represents the only fully tested, effective and safe treatment for euvolemic and hypervolemic hyponatremia, including the hyponatremia seen in patients with HF.12–15 V2 and combined V1a/V2 antagonism also produce incremental fluid loss, even when added acutely to loop diuretic regimens.13, 16–18 However, when given chronically to HF patients hospitalized for acute exacerbation of their chronic disease, selective V2 antagonism did not improve outcomes.12 Whether AVP levels independently influence outcomes in this patient population is important since this information may determine the utility of further investigation with AVP antagonism in HF. This may be particularly relevant to further study of V1a and/or combined V1a/V2 antagonists since maximal V2 signaling occurs at relatively low levels of plasma AVP, while V1a effects are dose dependent.

The EVEREST (Efficacy of Vasopressin Antagonism in Heart Failure Outcome Study with Tolvaptan) outcomes trial, 12 which investigated the effect of tolvaptan (a selective V2 antagonist) in patients hospitalized for HF and reduced EF, included measurements of plasma AVP in the majority of patients and thus provides an opportunity to examine these questions. In the current study, we assessed the impact of baseline and post-randomization AVP levels on outcomes in EVEREST.

METHODS

The details of the EVEREST study design 19 and outcomes 12, 13 have been previously published. Briefly, EVEREST was an international, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study examining the short- and long-term efficacy and safety of tolvaptan added to background medical therapy in patients hospitalized for worsening HF. Patients were ≥18 years of age, and hospitalized for worsening chronic HF with left ventricular EF≤40% and signs of fluid overload. They were randomized within 48 hours of hospitalization to oral tolvaptan (30 mg/day) or matching placebo in addition to conventional HF therapy for a minimum of 60 days. Patients with <6 month life expectancy were excluded. Specific recommendations for guideline-based optimal medical therapy were included in the study protocol but background medical therapy was ultimately left to the discretion of the treating physicians. The trial was conducted in full accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, with Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee approval at all sites. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Measurement of AVP was part of the primary EVEREST protocol, and subgroup analysis based on baseline AVP was pre-specified. Assays for AVP were performed at Covance central laboratories in Geneva and Indianapolis using the Buhlmann radio-immunoassay method.20 Patients were subdivided into high (>8 pg/ml) and low (≤8 pg/ml) AVP groups based on this being the upper limit of normal for the core lab performing the testing. All subjects had samples drawn, but due to inherent instability of AVP and to maintain adequate reliability of testing, only those samples that arrived to the core lab frozen and within the proper timeframe to preserve the sample were further processed.

The present analysis utilized the two pre-specified primary EVEREST endpoints: all-cause mortality (ACM) and a composite of cardiovascular mortality or rehospitalization for HF (CVM/H). Additional endpoints included cardiovascular mortality and worsening HF (defined as death from HF, hospitalization for HF, or unscheduled medical office visit for HF). Specific causes of death and reasons for rehospitalization were determined by an independent and blinded adjudication committee.

Patients were categorized into AVP >8 pg/ml versus ≤8 pg/ml, as indicated above. The association of baseline AVP group with baseline characteristics was assessed using a χ2, t-test, or Kruskal-Wallis test as appropriate. Times to events were compared by AVP group (>8pg/ml versus ≤8pg/ml) using log-rank tests and Cox regression models with adjustment for important baseline characteristics. The tolvaptan and placebo arms were combined for analyses of baseline AVP with outcomes because there were no significant differences in terms of long-term safety and/or clinical outcomes between treatment groups in the EVEREST outcomes trial.12, 13

Covariates in the regression models were selected based on clinical and statistical significance. Initially a base model was constructed (age, gender, B-type natriuretic peptide [BNP], N-terminal pro-BNP, geographic region, EF, serum sodium, blood urea nitrogen, systolic blood pressure, and QRS duration on electrocardiogram). Additional domains of covariates were then added in certain analyses. First was comorbid conditions (diabetes, hypertension, and renal insufficiency), followed by medications (angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers, beta-blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, digoxin, and inotropic agents).

To test whether baseline AVP could identify a subset of patients that received outcome benefit from tolvaptan treatment, treatment assignment was examined using an interaction term (i.e., AVP*treatment), and stratified by AVP level (i.e., >8 pg/ml versus ≤ 8 pg/ml). Additionally, to assess the effect of change in AVP following randomization, and particularly the role of tolvaptan, patients in each treatment arm were categorized into four groups depending on whether baseline and day 7 or hospital discharge AVP levels (whichever came first) were >8 pg/ml or ≤8 pg/ml (i.e. low/low, low/high, high/low, and high/high). Time to ACM was assessed in the base Cox regression models described above. Within each treatment group, hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are presented for ≤8 pg/ml at baseline/>8 pg/ml at day 7/discharge relative to those ≤8 pg/ml at baseline who remained ≤8 pg/ml; and for those >8 pg/ml at baseline/>8 pg/ml at day 7/discharge relative to those with >8 pg/ml at baseline who decreased to ≤8 pg/ml at day 7/discharge. Interaction analysis was performed between treatment assignment and elevated day 7/discharge AVP (>8 pg/ml) for ACM.

P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The sponsor performed database management according to a pre-specified plan. Analysis was conducted using SAS software, version 8.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and R software (R Development Core Team, 2005).

RESULTS

A total of 4,133 patient subjects participated in the EVEREST outcomes trial, of which 3,196 had baseline AVP measured. The present study cohort was mostly male (75%) and Caucasian (85%), with an average age of roughly 65 years, reflecting the overall trial population. Among subjects with baseline AVP measurement, 59% had AVP levels below the lower detection limit of the assay, 19% had levels within the normal range, and 22% had levels which were elevated (i.e., >8 pg/ml). A total of 851 deaths occurred and there were 1,366 events for the composite endpoint. Baseline AVP was positively associated with a number of baseline characteristics including higher natriuretic peptide levels, higher heart rate, higher aldosterone, lower EF, and several others (Table 1). Higher AVP was not related to baseline serum sodium (p=0.227).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by baseline AVP category

| Characteristic | AVP ≤8 pg/ml (N=2502, 78%) | AVP >8 pg/ml (N=694, 22%) | p- value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AVP, pg/ml, median | 2.8 | 10.7 | -- | |

| Randomized to Tolvaptan, % | 50 | 49 | 0.623 | |

|

| ||||

|

Demographic Characteristics

| ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 65.9 (±12.0) | 64.7 (±12.0) | 0.016 | |

| Male, % | 75 | 75 | 0.975 | |

| Caucasian, % | 85 | 84 | 0.492 | |

|

| ||||

|

Physical Exam and Laboratory Findings

| ||||

| Weight, kg, mean (SD) | 83.7 (±18.8) | 81.0 (±19.1) | 0.001 | |

| Systolic BP, mmHg, mean (SD) | 120 ± 20 | 119 ± 19 | 0.057 | |

| Heart Rate, bpm, mean (SD) | 79 ± 15 | 82 ± 17 | <0.001 | |

| JVD ≥ 10 cm, % | 27 | 32 | 0.005 | |

| Ejection fraction, %, mean (SD) | 27.5 ± 8.1 | 26.6 ± 7.9 | 0.016 | |

| BUN, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 26 (19, 35) | 28 (22, 38) | <0.001 | |

| Creatinine, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.6) | 1.3 (1.1, 1.7) | <0.001 | |

| Sodium, meq/dL, median (IQR) | 140 (137, 142) | 140 (137, 143) | 0.227 | |

| Aldosterone, ng/dl, median (IQR) | 11 (5, 20) | 13 (6, 26) | <0.001 | |

| BNP, pg/mL, median IQR) | 672 (288, 1481) | 898 (394, 1835) | <0.001 | |

| NYHA class, % | III | 61 | 55 | 0.007 |

| IV | 38 | 45 | ||

|

| ||||

|

Admission Medications, %

| ||||

| ACEI/ARB | 83 | 82 | 0.383 | |

| Beta-blockers | 74 | 72 | 0.267 | |

| MRA | 57 | 61 | 0.057 | |

| Digoxin | 45 | 40 | 0.012 | |

| Intravenous inotropes | 1 | 2 | 0.152 | |

|

| ||||

|

Comorbid Conditions, %

| ||||

| Previous HF hospitalization | 79 | 80 | 0.391 | |

| Previous MI | 51 | 51 | 0.939 | |

| Hypertension | 72 | 68 | 0.050 | |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 51 | 46 | 0.024 | |

| Atrial arrhythmia | 51 | 50 | 0.500 | |

| Diabetes | 40 | 36 | 0.097 | |

| Previous CABG | 23 | 17 | <0.001 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 27 | 28 | 0.761 | |

| Previous stroke | 12 | 11 | 0.836 | |

| Severe COPD | 11 | 9 | 0.062 | |

Abbreviations: ACEI= angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB= angiotensin II receptor blocker; AVP= arginine vasopressin; BNP= B-type natriuretic peptide; BP= blood pressure; BPM= beats per minute; BUN= blood urea nitrogen; CABG= coronary artery bypass graft; COPD= chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HF= heart failure; IQR= interquartile range; JVD= jugular venous distention; MI= myocardial infarction; MRA= mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NYHA= New York Heart Association; SD= standard deviation.

Baseline AVP and Survival

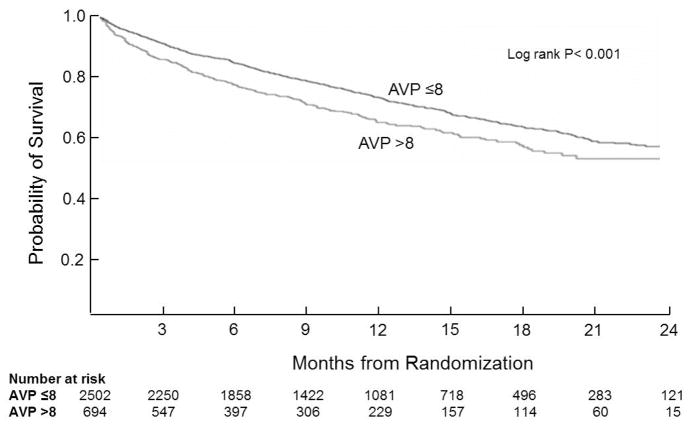

In univariate analysis, elevated baseline AVP was associated with reduced survival (Figure 1, p<0.001). In analyses adjusted for important baseline factors, high AVP was independently associated with increased ACM (HR 1.33, 95% CI 1.13 –1.55) and CVM/H (HR 1.23 95% CI 1.08 –1.39). Elevated AVP remained predictive of ACM when models were additionally adjusted for comorbidities and admission medications (Table 2).

Figure 1.

All-cause mortality by baseline AVP group. Times to events were compared using log-rank tests. Abbreviations: AVP= arginine vasopressin.

Table 2.

Analysis of co-primary endpoints by presence of baseline elevated AVP level (> 8 pg/ml)

| Models | Endpoint | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base* | All-Cause Mortality | 1.33 | 1.13, 1.55 |

| Base* | CVM/H | 1.23 | 1.08, 1.39 |

| Base* + Comorbidities† | All-Cause Mortality | 1.23 | 1.04, 1.46 |

| Base* + Comorbidities† +Medications‡ | All-Cause Mortality | 1.28 | 1.08, 1.52 |

Base model covariates: Age, gender, BNP, N-terminal Pro-BNP, geographic region, ejection fraction, serum sodium, blood urea nitrogen, systolic blood pressure, QRS duration on electrocardiogram.

Comorbidity covariates: Diabetes, hypertension, renal insufficiency

Medication covariates: Use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, beta-blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, digoxin, or intravenous inotropes at time of randomization.

Abbreviations: AVP= arginine vasopressin; BNP= B-type natriuretic peptide; CI= confidence interval; CVM/H= cardiovascular mortality or heart failure hospitalization.

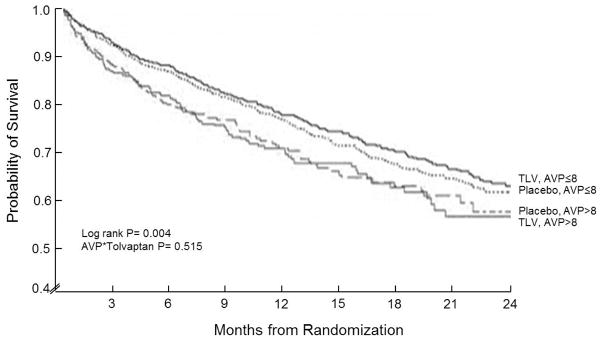

Baseline AVP and Long-Term Efficacy of Tolvaptan

When analyzing the entire cohort and using an AVP*Treatment interaction, there was no significant association (interaction p=0.515, Figure 2). We also examined tolvaptan effect in the high AVP group alone. Furthermore, among patients with AVP>8 pg/ml, there was no benefit of tolvaptan in terms of mortality, with 29% dying during follow-up in both treatment groups (p=0.76). The same was true for other endpoints examined, which included CVM/H, cardiovascular mortality, and worsening HF (all p>0.5).

Figure 2.

All-cause mortality by AVP group (>8 versus ≤8 pg/ml) and treatment (tolvaptan versus placebo). Times to events were compared using log-rank tests. Abbreviations: AVP= arginine vasopressin; TLV= tolvaptan.

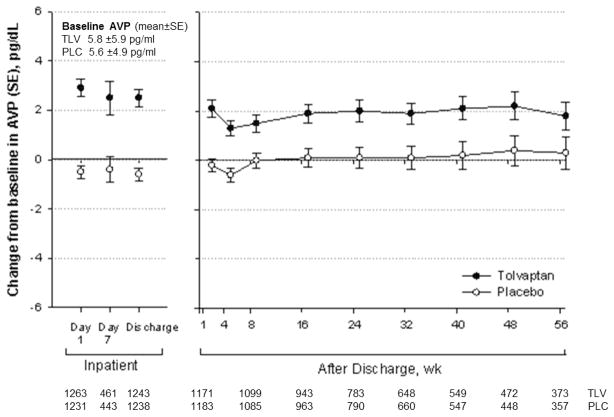

Changes in AVP due to Tolvaptan

Tolvaptan caused a clear increase in AVP levels as early as day 1 and persisting through at least 56 weeks of follow-up (Figure 3). At baseline, both the tolvaptan and placebo groups had 22% of subjects with elevated AVP (>8pg/ml). The mean baseline AVP levels for the placebo and tolvaptan groups were 5.6 pg/ml and 5.8 pg/ml, respectively. Among patients with normal baseline levels of AVP, a higher proportion of the patients on tolvaptan became >8pg/ml during their hospital stay (day 7 or discharge, which ever came first) relative to the placebo group (32% versus 9%, p<0.001). Similarly, among patients whose baseline AVP was >8pg/ml, those in the tolvaptan arm were more likely to remain elevated compared to placebo treated patients (73% versus 42%, p <0.001).

Figure 3.

In-hospital and post-discharge change in AVP level by treatment group. Abbreviations: AVP= arginine vasopressin; PLC= placebo; SE= standard error; TLV= tolvaptan; WK= weeks.

In adjusted models of patients receiving placebo, elevated AVP at day 7 or discharge (versus ≤8 pg/ml on day 7 or discharge) was associated with significantly increased risk of ACM regardless of baseline AVP level (baseline AVP ≤8 pg/ml HR 1.59, 95% CI 1.04, 2.43; baseline AVP >8pg/ml HR 2.25, 95% CI 1.37, 3.68) (Table 3). In contrast, there was no association observed with the risk of death among tolvaptan treated patients, and formal testing indicated a statistically significant interaction of treatment assignment with increased day 7/discharge AVP in terms of mortality (p=0.043).

Table 3.

Analysis of all-cause mortality for elevated Day 7/discharge AVP level (> 8 pg/ml) by baseline AVP level and treatment assignment*

| Baseline AVP group | Placebo Group Hazard Ratios (95% CI)†‡ | Tolvaptan Group Hazard Ratios (95% CI)†‡ | Interaction p-value§ |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤8 pg/ml (n=2132) | 1.59 (1.04, 2.43) | 0.95 (0.72, 1.24) | 0.043 |

| >8 pg/ml (n=562) | 2.25 (1.37, 3.68) | 1.06 (0.62, 1.81) |

AVP level was measured at day 7 following study randomization or on day of hospital discharge, whichever came first.

Results are reported as risk of AVP level > 8 pg/ml on day 7/discharge compared to AVP level ≤8 pg/ml on day 7/discharge.

Hazard ratios were derived from a single model adjusted for age, gender, BNP, N-terminal Pro-BNP, geographic region, ejection fraction, serum sodium, blood urea nitrogen, systolic blood pressure, and QRS duration on electrocardiogram.

Interaction term represents interaction between 4 AVP groups (≤8 at baseline, >8 at day 7/discharge; ≤8 at baseline, ≤8 at day 7/discharge; >8 at baseline, >8 at day 7/discharge; >8 at baseline, ≤8 at day 7/discharge) and treatment group (placebo or tolvaptan).

Abbreviations: AVP= arginine vasopressin; BNP= B-type natriuretic peptide; CI= confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

Our data demonstrate that elevated baseline AVP is correlated with many high-risk characteristics among patients hospitalized with worsening chronic systolic HF, and moreover, that baseline AVP is independently associated with longer term outcomes, including death. It is also clear that baseline AVP level did not help identify a subset of patients in whom tolvaptan was effective. Interestingly, tolvaptan administration significantly increased AVP levels, but this did not worsen outcomes.

Our data are consistent with previous reports but extend the pre-existing knowledge in multiple ways. High baseline AVP levels were not associated with any trend toward benefit due to tolvaptan, eliminating this as a possible strategy for therapeutic targeting with this agent. While this finding could be specific to tolvaptan, it may also indicate that AVP levels have limited importance in predicting the effectiveness of V2 antagonism in patients hospitalized with HF. This is consistent with previous observations that maximal V2 effects are seen at very modest levels of plasma AVP, as reflected in the robust urinary responses to tolvaptan in both normal subjects and patients with hyponatremia.15 While past studies have described a correlation between AVP level and HF severity,2–4 whether a relationship between AVP and outcomes would persist in the setting of exacerbation and hospitalization of chronic HF, where differing risk factors may be at play, was not known. These data demonstrate that elevated AVP is, at minimum, an independent prognostic factor. Since V2 antagonism alone with tolvaptan did not improve outcomes in EVEREST, our findings suggest potential value in the further development of either V1a antagonists or combined V1a/V2 antagonists for HF.

The fact that tolvaptan increased AVP levels without an observable adverse effect on long-term clinical outcomes is a notable point, but with an unclear mechanism. One potential explanation is that the incremental increase in V1a activation produced by tolvaptan was insufficient to produce additional detectable harm. Similarly, the degree of additional weight loss produced by tolvaptan was perhaps inadequate to decrease diastolic wall stress to the level necessary to promote reverse remodeling, as was shown in the METEOR trial.21 Alternatively, it may be that significant adverse effects from V1a stimulation were negated or obscured by beneficial effects from V2 antagonism.22 While this latter hypothesis remains possible since higher AVP levels were associated with adverse outcomes in both trial arms, to argue for offsetting effects (i.e., equal benefit and harm) which could not be specifically demonstrated in the present study seems unnecessarily strenuous. Additionally, it is possible that the potential deleterious effects of acutely increased V1a activity with tolvaptan were largely attenuated by concurrent use of HF therapies that modulate neurohormones such as beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. The majority of patients in the long-term EVEREST trial and in the present analysis were receiving standard evidence-based therapies (Table 1) and use of these agents may have neutralized the potential harms of increased V1a stimulation seen with tolvaptan.

There are several limitations that should be considered when interpreting these data. First, AVP has limited stability for laboratory testing and is less robust in terms of the sample handling required. This resulted in nearly one quarter of the total cohort not having adequate samples for testing. Our sample size was sufficiently large to provide adequate power despite this loss, but attempts to use AVP level clinically as a risk predictor are likely to be marred by this difficulty. There were also limitations in assay sensitivity (lower limit was 5.6 pg/ml) and as a result most patients had results below detection. This impaired the ability to analyze AVP as a continuous variable (especially in terms of the change from baseline), and necessitated using the cut-point analysis described, which could be less sensitive. Additionally, the present study is unable to definitively elucidate the mechanism underlying the differential effect of increases in AVP level on outcomes between the placebo and tolvaptan treatment arms. Furthermore, this study does not specifically address the utility of AVP pathway modulation as a treatment strategy for improving outcomes in patients hospitalized with HF. However, the goal of this study was to investigate AVP level as a prognostic marker and further studies are necessary to characterize AVP level as a potential therapeutic target for V1a antagonists, combined V1a/V2 antagonists, or other AVP pathway modifying agents. Finally, AVP is correlated to many other risk-associated variables, making it challenging to define its independent effect. Our data set is large with extensive and detailed collection of phenotypic data on the patient population, and our analytic approach performed extensive adjustment for covariates associated with AVP and thought to be important in HF outcomes. While we feel this was adequate and that our findings reflect the independent effect of AVP on HF outcomes, we cannot completely rule out all residual confounding.

In conclusion, this analysis of the EVEREST outcomes trial found elevated baseline AVP levels to be an independent predictor of mortality in patients hospitalized for worsening HF with reduced EF, but did not identify a patient subgroup where tolvaptan treatment improved clinical outcomes. Tolvaptan treatment was associated with a clear increase in AVP level without an associated worsening of outcomes, suggesting that any excess V1 stimulation which did occur due to this drug did not detectably impact long-term clinical outcomes in the setting of V2 blockade. These data should inform and encourage further investigation into potential beneficial methods of manipulating the AVP pathway for the treatment of HF.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SOURCES

Otsuka Inc. (Rockville, MD) provided financial and material support for the EVEREST trial. Database management was performed by the sponsor. AJK and MJK conducted all final analyses for this manuscript with funding from the Center for Cardiovascular Innovation (Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL). DEL is supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Lanfear HL085124, HL103871).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

MG has been a consultant for Abbott Laboratories, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer HealthCare AG, CorThera, Cytokinetics, DebioPharm S.A., Errekappa Terapeutici, GlaxoSmithKline, Ikaria, Johnson & Johnson, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis Pharma AG, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Palatin Technologies, Pericor Therapeutics, Protein Design Laboratories, Sanofi-Aventis, Sigma Tau, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Takeda Pharmaceutical and Trevena Therapeutics. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Makuc DM, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, Moy CS, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Soliman EZ, Sorlie PD, Sotoodehnia N, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2012 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2–e220. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldsmith SR, Francis GS, Cowley AW, Jr, Levine TB, Cohn JN. Increased plasma arginine vasopressin levels in patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1983;1:1385–1390. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(83)80040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benedict CR, Johnstone DE, Weiner DH, Bourassa MG, Bittner V, Kay R, Kirlin P, Greenberg B, Kohn RM, Nicklas JM, McIntyre K, Quinones MA, Yusuf S. Relation of neurohumoral activation to clinical variables and degree of ventricular dysfunction: a report from the Registry of Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction. SOLVD Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:1410–1420. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90385-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Francis GS, Benedict C, Johnstone DE, Kirlin PC, Nicklas J, Liang CS, Kubo SH, Rudin-Toretsky E, Yusuf S. Comparison of neuroendocrine activation in patients with left ventricular dysfunction with and without congestive heart failure. A substudy of the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) Circulation. 1990;82:1724–1729. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.5.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rouleau JL, Packer M, Moye L, de Champlain J, Bichet D, Klein M, Rouleau JR, Sussex B, Arnold JM, Sestier F, Parker JO, McEwan P, Bernstein V, Cuddy TE, Lamas G, Gottlieb SS, McCans J, Nadeau C, Delage F, Wun CC, Pheffer MA. Prognostic value of neurohormonal activation in patients with an acute myocardial infarction: effect of captopril. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;24:583–591. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ambrosy A, Goldsmith SR, Gheorghiade M. Tolvaptan for the treatment of heart failure: a review of the literature. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011;12:961–976. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2011.567267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldsmith SR, Cowley AW, Jr, Francis GS, Cohn JN. Reflex control of osmotically stimulated vasopressin in normal humans. Am J Physiol. 1985;248:R660–663. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1985.248.6.R660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldsmith SR, Gheorghiade M. Vasopressin antagonism in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1785–1791. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finley JJ, Konstam MA, Udelson JE. Arginine vasopressin antagonists for the treatment of heart failure and hyponatremia. Circulation. 2008;118:410–421. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.765289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Penit J, Faure M, Jard S. Vasopressin and angiotensin II receptors in rat aortic smooth muscle cells in culture. Am J Physiol. 1983;244:E72–82. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1983.244.1.E72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldsmith SR. Vasopressin receptor antagonists: mechanisms of action and potential effects in heart failure. Cleve Clin J Med. 2006;73 (Suppl 2):S20–23. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.73.suppl_2.s20. discussion S30–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Konstam MA, Gheorghiade M, Burnett JC, Jr, Grinfeld L, Maggioni AP, Swedberg K, Udelson JE, Zannad F, Cook T, Ouyang J, Zimmer C, Orlandi C. Effects of oral tolvaptan in patients hospitalized for worsening heart failure: the EVEREST Outcome Trial. JAMA. 2007;297:1319–1331. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.12.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gheorghiade M, Konstam MA, Burnett JC, Jr, Grinfeld L, Maggioni AP, Swedberg K, Udelson JE, Zannad F, Cook T, Ouyang J, Zimmer C, Orlandi C. Short-term clinical effects of tolvaptan, an oral vasopressin antagonist, in patients hospitalized for heart failure: the EVEREST Clinical Status Trials. JAMA. 2007;297:1332–1343. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.12.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orlandi C, Zimmer CA, Gheorghiade M. Tolvaptan for the treatment of hyponatremia and congestive heart failure. Future Cardiol. 2006;2:627–634. doi: 10.2217/14796678.2.6.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schrier RW, Gross P, Gheorghiade M, Berl T, Verbalis JG, Czerwiec FS, Orlandi C. Tolvaptan, a selective oral vasopressin V2-receptor antagonist, for hyponatremia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2099–2112. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gheorghiade M, Gattis WA, O’Connor CM, Adams KF, Jr, Elkayam U, Barbagelata A, Ghali JK, Benza RL, McGrew FA, Klapholz M, Ouyang J, Orlandi C. Effects of tolvaptan, a vasopressin antagonist, in patients hospitalized with worsening heart failure: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1963–1971. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.16.1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gheorghiade M, Niazi I, Ouyang J, Czerwiec F, Kambayashi J, Zampino M, Orlandi C. Vasopressin V2-receptor blockade with tolvaptan in patients with chronic heart failure: results from a double-blind, randomized trial. Circulation. 2003;107:2690–2696. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070422.41439.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pang PS, Konstam MA, Krasa HB, Swedberg K, Zannad F, Blair JE, Zimmer C, Teerlink JR, Maggioni AP, Burnett JC, Jr, Grinfeld L, Ouyang J, Udelson JE, Gheorghiade M. Effects of tolvaptan on dyspnea relief from the EVEREST trials. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2233–2240. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gheorghiade M, Orlandi C, Burnett JC, Demets D, Grinfeld L, Maggioni A, Swedberg K, Udelson JE, Zannad F, Zimmer C, Konstam MA. Rationale and design of the multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the Efficacy of Vasopressin antagonism in Heart Failure: Outcome Study with Tolvaptan (EVEREST) J Card Fail. 2005;11:260–269. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glick SM, Kagan A. Radioimmunoassay of arginine vasopressin. In: Jaffe BM, Behrman HR, editors. Methods of hormone radioimmunoassay. 2. New York: Academic Press; 1979. p. 1040. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Udelson JE, McGrew FA, Flores E, Ibrahim H, Katz S, Koshkarian G, O’Brien T, Kronenberg MW, Zimmer C, Orlandi C, Konstam MA. Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study on the effect of oral tolvaptan on left ventricular dilation and function in patients with heart failure and systolic dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2151–2159. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pitt B, Gheorghiade M. Vasopressin V1 receptor-mediated aldosterone production as a result of selective V2 receptor antagonism: a potential explanation for the failure of tolvaptan to reduce cardiovascular outcomes in the EVEREST trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:1261–1263. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]