Abstract

Objective

To assess differences between men and women in the prevalence of diabetes mellitus, impaired fasting glycaemia and impaired glucose tolerance in sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods

In September 2011, the PubMed and Web of Science databases were searched for community-based, cross-sectional studies providing sex-specific prevalences of any of the three study conditions among adults living in parts of sub-Saharan Africa (i.e. in Eastern, Middle and Southern Africa according to the United Nations subregional classification for African countries). A random-effects model was then used to calculate and compare the odds of men and women having each condition.

Findings

In a meta-analysis of the 36 relevant, cross-sectional data sets that were identified, impaired fasting glycaemia was found to be more common in men than in women (OR: 1.56; 95% confidence interval, CI: 1.20–2.03), whereas impaired glucose tolerance was found to be less common in men than in women (OR: 0.84; 95% CI: 0.72–0.98). The prevalence of diabetes mellitus – which was generally similar in both sexes (OR: 1.01; 95% CI: 0.91–1.11) – was higher among the women in Southern Africa than among the men from the same subregion and lower among the women from Eastern and Middle Africa and from low-income countries of sub-Saharan Africa than among the corresponding men.

Conclusion

Compared with women in the same subregions, men in Eastern, Middle and Southern Africa were found to have a similar overall prevalence of diabetes mellitus but were more likely to have impaired fasting glycaemia and less likely to have impaired glucose tolerance.

Résumé

Objectif

Évaluer les différences entre hommes et femmes en termes de prévalence du diabète sucré, de la glycémie à jeun anormale et de l'intolérance au glucose en Afrique subsaharienne.

Méthodes

En septembre 2011, on a recherché dans les bases de données PubMed et Web of Science des études communautaires transversales fournissant les prévalences spécifiques au sexe des trois maladies faisant l'objet de l'étude, chez des adultes vivant dans certaines régions d'Afrique subsaharienne (par exemple en Afrique orientale, centrale et australe, selon la classification sous-régionale des Nations Unies pour les pays africains). Un modèle à effets aléatoires a ensuite été utilisé pour calculer et comparer les cotes des hommes et des femmes affectés par chacune de ces maladies.

Résultats

Dans une méta-analyse des 36 séries de données transversales pertinentes identifiées, on a découvert que la glycémie à jeun anormale était plus fréquente chez les hommes que chez les femmes (RC: 1,56, intervalle de confiance de 95%, IC: 1,20 à 2,03), tandis que la tolérance au glucose s'est révélée moins fréquente chez les hommes que chez les femmes (RC: 0,84, IC de 95%: 0,72 à 0,98). La prévalence du diabète sucré - généralement semblable chez les deux sexes (RC: 1,01, IC de 95%: 0,91 à 1,11) - était plus élevée chez les femmes d'Afrique australe que chez les hommes de la même sous-région, et plus faible chez les femmes d'Afrique orientale et centrale et des pays à faible revenu d'Afrique subsaharienne que chez les hommes des mêmes pays.

Conclusion

Par rapport aux femmes des mêmes sous-régions, on a découvert que la prévalence globale du diabète sucré était similaire chez les hommes d'Afrique orientale, mais que ceux-ci étaient plus susceptibles de souffrir de glycémie à jeun anormale et moins susceptibles d'être affectés par une intolérance au glucose.

Resumen

Objetivo

Evaluar las diferencias entre hombres y mujeres respecto a la prevalencia de la diabetes mellitus, las alteraciones de la glucemia en ayunas y la intolerancia a la glucosa en África subsahariana.

Métodos

En septiembre de 2011, se realizaron búsquedas en las bases de datos de PubMed y Web of Science a fin de hallar estudios comunitarios transversales que proporcionaran datos sobre las prevalencias específicas de cada sexo de cualquiera de las tres enfermedades de estudio entre los adultos residentes en zonas de África subsahariana (es decir, en el Este, Centro y Sur de África, según la clasificación subregional de las Naciones Unidas para los países africanos). Se empleó un modelo de efectos aleatorios para calcular y comparar las probabilidades por parte de hombres y mujeres de padecer cada una de las enfermedades.

Resultados

En un metaanálisis de los 36 conjuntos de datos de carácter transversal pertinentes que se identificaron, se halló que las alteraciones de la glucemia en ayunas eran más comunes en hombres que en mujeres (OR: 1,56; intervalo de confianza del 95%, IC: 1,20 a 2,03), por el contrario, se descubrió que la intolerancia a la glucosa era menos común en los hombres que en las mujeres (OR: 0,84; IC del 95%: 0,72 a 0,98). La prevalencia de la diabetes mellitus (la cual fue, por lo general, similar en ambos sexos (OR: 1,01; IC 95%: 0,91 a 1,11) fue mayor entre las mujeres del Sur de África que entre los hombres de la misma subregión, y menor entre las mujeres del Este y Centro de África, así como en los países de ingresos bajos de África subsahariana, que entre los hombres correspondientes.

Conclusión

En comparación con las mujeres de las mismas subregiones, se halló que los hombres del Este, Centro y Sur de África tienen una prevalencia general similar de la diabetes mellitus, pero son más propensos a padecer alteraciones de la glucemia en ayunas y menos propensos a padecer intolerancia a la glucosa.

ملخص

الغرض

تقيمم الاختلافات بين الرجال والنساء في معدل انتشار داء السكري، واختلال سكر الدم مع الصيام واختلال تحمل الغلوكوز في أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء الكبرى.

الطريقة

في أيلول/سبتمبر 2011، تم البحث في قواعد بيانات PubMed وWeb of Science عن الدراسات المجتمعية متعددة القطاعات التي تقدم معدلات انتشار لأي من حالات الدراسة الثلاث بين البالغين الذين يسكنون مناطق من أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء الكبرى (أي في أفريقيا الشرقية والوسطى والجنوبية وفقاً لتصنيف المنطقة دون الإقليمية للبلدان الأفريقية حسب الأمم المتحدة). وتم استخدام نموذج التأثيرات العشوائية لحساب الاحتمالات بين الرجال والنساء في كل حالة.

النتائج

في تحليل وصفي لفئات البيانات متعددة القطاعات ذات الصلة التي تم تحديدها البالغ عددها 36 فئة، تم التوصل إلى أن اختلال سكر الدم مع الصيام أكثر شيوعاً لدى الرجال عنه لدى النساء (نسبة الاحتمال: 1.56؛ فاصل الثقة 95 %: من 1.20 إلى 2.03)، في حين تم التوصل إلى أن اختلال تحمل الغلوكوز أقل شيوعاً لدى الرجال عنه لدى النساء (نسبة الاحتمال: 0.84؛ فاصل الثقة 95 %: من 0.98 إلى 0.72) وكان معدل انتشار داء السكري – الذي تشابه عموماً في كلا الجنسين (نسبة الاحتمال: 1.01؛ فاصل الثقة 95 %: من 0.91 إلى 1.11) – أعلى بين النساء في أفريقيا الجنوبية عنه بين الرجال من نفس المنطقة دون الإقليمية وأقل بين النساء من أفريقيا الشرقية والوسطى ومن بلدان أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء الكبرى المنخفضة الدخل عنه بين الرجال المقابلين لهم.

الاستنتاج

مقارنة بالنساء من نفس المناطق دون الإقليمية، تم التوصل إلى أن الرجال في أفريقيا الشرقية والوسطى والجنوبية لديهم معدل انتشار عام مشابه لداء السكري غير أنه ازدادت لديهم احتمالية الإصابة باختلال سكر الدم مع الصيام في حين قلت لديهم احتمالية الإصابة باختلال تحمل الغلوكوز.

摘要

目的

评估撒哈拉以南非洲糖尿病、空腹血糖受损和糖耐量异常患病率的男女差异。

方法

在2011 年9 月,搜索PubMed和Web of Science数据库,查找基于社区、提供撒哈拉以南非洲区域(即根据联合国对非洲国家的亚区分类:东非、中非和南非)居住的成年人当中三种研究状况中任一种状况的特定性别患病率的横断面研究。然后使用随机效果模型计算和比较患有各种病情的男女差别。

结果

在所识别的36 个相关的横断面数据集的元分析中,较之女性,在男性中空腹血糖受损更常见(OR:1.56;95%置信区间,CI:1.20–2.03),而女性的糖耐量受损比男性更常见(OR:0.84;95% CI:0.72–0.98)。对于两性之间大致差不多(OR:1.01;95% CI:0.91–1.11)的糖尿病患病率,南非女性比同一亚区男性高,东非和中非以及撒哈拉以南非洲低收入国家则是男高女低。

结论

与同一亚区女性比较,东非、中非和南非的男性的糖尿病总体患病率相似,但是空腹血糖受损患病率更高,糖耐量受损患病率更低。

Резюме

Цель

Оценить различия между мужчинами и женщинами в распространенности сахарного диабета, нарушенной гликемии натощак и нарушенной переносимости глюкозы в Африке южнее Сахары.

Методы

В сентябре 2011 года был осуществлен поиск в базах данных PubMed и Web of Science территориальных поперечных исследований, предоставляющих данные в половом разрезе о распространенности любого из трех исследуемых заболеваний среди взрослых, живущих в Африке южнее Сахары (то есть в Восточной, Средней и Южной Африке, согласно субрегиональной классификации африканских стран Организацией Объединенных Наций). Затем для расчета и сопоставления риска мужчин и женщин подвергнуться каждому из заболеваний была использована модель случайных эффектов.

Результаты

Мета-анализ идентифицированных 36 релевантных поперечных наборов данных показал, что нарушение гликемии натощак чаще встречается у мужчин, чем у женщин (соотношение риска, СР: 1,56; 95% доверительный интервал, ДИ: 1,20–2,03), в то время как нарушенная переносимость глюкозы у мужчин встречается реже, чем у женщин (СР: 0,84; 95% ДИ: 0.72–0.98). Распространенность сахарного диабета, которая в целом была аналогична у обоих полов (СР: 1,01; 95% ДИ: 0,91–1,11), в Южной Африке была выше среди женщин, чем среди мужчин из того же субрегиона, и ниже среди женщин из стран Восточной и Центральной Африки, а также из малообеспеченных стран Африки южнее Сахары, чем среди мужчин из той же выборки.

Вывод

У мужчин в Восточной, Средней и Южной Африке была обнаружена аналогичная с женщинами в тех же субрегионах общая распространенность сахарного диабета, но чаще встречались нарушения гликемии натощак и реже – нарушенная толерантность к глюкозе.

Introduction

Increasing urbanization and the accompanying changes in lifestyle are leading to a burgeoning epidemic of chronic noncommunicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa.1,2 At the same time, the prevalence of many acute communicable diseases is decreasing.1,2 In consequence, the inhabitants of sub-Saharan Africa are generally living longer and this increasing longevity will result in a rise in the future incidence of noncommunicable diseases in the region.1–3

Diabetes mellitus is one of the most prominent noncommunicable diseases that are undermining the health of the people in sub-Saharan Africa and placing additional burdens on health systems that are often already strained.4,5 In 2011, 14.7 million adults in the African Region of the World Health Organization (WHO) were estimated to be living with diabetes mellitus.6 Of all of WHO’s regions, the African Region is expected to have the largest proportional increase (90.5%) in the number of adult diabetics by 2030.6

Sex-related differences in lifestyle may lead to differences in the risk of developing diabetes mellitus and, in consequence, to differences in the prevalence of this condition in women and men.3 However, the relationship between a known risk factor for diabetes mellitus – such as obesity – and the development of symptomatic diabetes mellitus may not be simple. For example, in many countries of sub-Saharan Africa, women are more likely to be obese or overweight than men and might therefore be expected to have higher prevalences of diabetes mellitus.3,7 Compared with the corresponding men, women in Cameroon8, South Africa9 and Uganda10 were indeed found to have higher prevalences of diabetes mellitus. However, women in Ghana,11 Nigeria,12 Sierra Leone13 and rural areas of the United Republic of Tanzania14 were found to have lower prevalences of diabetes mellitus than the men in the same study areas. No significant differences between men and women in the prevalence of diabetes mellitus were detected in studies in Guinea,15 Mali,16 Sudan17 and urban areas of the United Republic of Tanzania,18 or in a meta-analysis of data collected in several studies in West Africa.19 Although wide variations in the distribution of diabetes mellitus by sex have been documented in several review articles,3–5,7,20 the possible causes of this heterogeneity have never been examined in detail.

Like obesity, impaired fasting glycaemia and impaired glucose tolerance appear to be risk factors in the development of diabetes mellitus.21,22 According to the International Diabetes Federation, the estimated age-adjusted prevalence of impaired fasting glycaemia in WHO’s African Region was substantially higher in 2011 than the corresponding global mean value – 9.7% versus 6.5%, respectively – and is expected to have risen further by 2030.23

Impaired fasting glycaemia and impaired glucose tolerance are reported to be metabolically distinct entities that affect different subpopulations, albeit with some degree of overlap.22,24 In Mauritius, the prevalence of impaired fasting glycaemia was found to be significantly higher in men than in women, whereas the prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance was found to be higher in women than in men.24,25

Differences between men and women in the prevalence of diabetes mellitus, impaired fasting glycaemia and impaired glucose tolerance in much of sub-Saharan Africa have yet to be reviewed. Given the variation in health care, culture, environment, human behaviour and other determinants of health across sub-Saharan Africa,26 the conclusions drawn from a recent meta-analysis of data from West Africa19 should not be assumed to apply to the whole of sub-Saharan Africa. The sex-specific prevalence of at least one risk factor for diabetes mellitus – obesity – is known to differ across different parts of sub-Saharan Africa.7,27

The main aims of the present systematic review were to examine differences between men and women in the prevalence of three conditions – diabetes mellitus, impaired fasting glycaemia and impaired glucose tolerance – in Eastern, Middle and Southern Africa (i.e. all in sub-Saharan Africa according to the United Nations subregional classification for African countries),28 and to explore the possible causes of any variation observed. We followed the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group’s guidelines for the reporting of systematic reviews of observational studies.29

Methods

Data sources

In September 2011, we searched PubMed and Web of Science for studies that presented the sex-specific prevalences of diabetes mellitus, impaired fasting glycaemia and/or impaired glucose tolerance in Eastern, Middle and/or Southern Africa (Table 1). The medical subject headings (MeSH) and search terms we used are described in Box 1. We limited our search to human studies but placed no restrictions on the language of publication. We also used Google, Google Scholar and WHO’s InfoBase to search the “grey” literature for relevant studies and reports. The citations in articles that appeared to be relevant were examined for other articles that might hold useful data. When it seemed possible that relevant data had been recorded but not published, the authors of published study reports were contacted via e-mail to see if they could provide such data.

Table 1. Countries comprising sub-Saharan Africa, by African subregiona.

| Subregion | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern | Middle | Southern | Western |

| Burundi | Angola | Botswana | Benin |

| Comoros | Cameroon | Lesotho | Burkina Faso |

| Djibouti | Central African Republic | Namibia | Cape Verde |

| Eritrea | Chad | South Africa | Côte d’Ivoire |

| Ethiopia | Congo | Swaziland | Gambia |

| Kenya | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Ghana | |

| Madagascar | Equatorial Guinea | Guinea-Bissau | |

| Malawi | Gabon | Liberia | |

| Mauritius | Sao Tome and Principe | Mali | |

| Mozambique | Mauritania | ||

| Rwanda | Niger | ||

| Seychelles | Nigeria | ||

| Somalia | Senegal | ||

| Sudan | Sierra Leone | ||

| Uganda | Togo | ||

| United Republic of Tanzania | |||

| Zambia | |||

| Zimbabwe | |||

a As designated by the United Nations.28

Box 1. Strategy followed in searching PubMed and the Web of Science.

Various medical subject headings (MeSH) and search terms, including “prevalence”, “incidence”, “epidemiology”, “proportion”, “rate”, “diabetes mellitus”, “hyperglycaemia”, “abnormal* blood glucose”, “glucose intolerance”, “dysglycaemia”, “insulin resistance”, “metabolic* syndrome”, “insulin resistance syndrome X”, “cardiovascular syndrome”, “hypertension”, “increase* blood pressure”, “obesity”, “overweight”, “hypercholesterolaemia”, “hyperlipidaemia”, “dyslipidaemia”, “physical inactivity”, “smoking”, “cardiovascular diseases risk factors” and “Africa South of the Sahara” – and alternative spellings such as “hyperglycemia” were used. Searches were combined with the names of each country in Eastern, Middle and Southern Africa (Table 1) – except Cameroon, which was included in a previous study on West Africa19 – by using the Boolean operators “OR” or “AND”.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Data were included in the meta-analysis if they came from studies that fulfilled all of the following criteria:

community-based;

cross-sectional;

reported prevalence of diabetes mellitus, impaired fasting glycaemia and/or impaired glucose tolerance;

reported either odds ratios (ORs) for differences between men and women in the prevalence of diabetes mellitus, impaired fasting glycaemia and/or impaired glucose tolerance or data that allowed the computation of such ORs;

conducted in apparently healthy, non-pregnant subjects;

most subjects are adults (i.e. aged ≥ 15 years) and residing in the UN-designated Eastern, Middle or Southern subregions of Africa;

both men and women investigated;

employed any of WHO’s diagnostic criteria – or the equivalent criteria of the American Diabetic Association – for diabetes mellitus, impaired fasting glycaemia and/or impaired glucose tolerance;30–38

reported results either in English or in another language with an abstract in English.

When multiple reports of the same study were retrieved, only the most informative report was selected. Clinic-, hospital- and laboratory-based studies, anonymous reports, letters, commentaries, case studies and reviews were excluded.

Data abstraction

After reading each article that appeared relevant and met the inclusion criteria, one of the authors (EHH) made notes of the year of study and publication, sampling method, sample size, response rate, study design, diagnostic criteria, study area, mean age and/or age range of the subjects, mean blood glucose level, the recorded prevalences of diabetes mellitus, impaired fasting glycaemia and/or impaired glucose tolerance, and, if available, the OR and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) that indicated the type and significance of any differences in these prevalences by sex. When articles presented data separately for urban and rural subjects, information for these two groups of subjects was extracted separately. When articles presented data stratified by subject age, only the data for subjects aged 15 years or older were included in the analysis. All of the extracted data were independently reviewed by a second author (HY).

Quality appraisal

A checklist – adopted from one created by the University of Wisconsin39 – was used to assess the quality of the included studies. The checklist had eight questions relating to the research question, selection of study subjects, comparability of study groups, handling of withdrawals, measurement of outcomes, statistical analyses, results and conclusions, and funding or sponsorship. If the answers to five or more of these questions were positive, the study involved was categorized as “positive” and considered to be of good quality. If the answers to five or more of these questions were negative, the study involved was categorized as “negative” and considered to be of poor quality. All other studies were categorized as “neutral”.

Statistical analysis

ORs were used as “effect estimates” to quantify the relationship between sex and the prevalence of diabetes mellitus, impaired fasting glycaemia and impaired glucose tolerance. If no OR had been reported, it was calculated from the raw data. Since the studies included in the meta-analysis used different standard populations, crude prevalences were preferred to the age-adjusted values when both were available. The DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model was used to estimate the mean OR for all of the studies included in the meta-analysis.40

Statistical heterogeneity across the studies was evaluated using both the Q and I2 statistics.40 In the Q-tests, a P-value of < 0.1 was considered indicative of statistically significant heterogeneity. We performed subgroup analyses to assess the potential influence of the following study-level covariates on the OR for any sex-specific differences: area of residence (urban or rural), subregion of residence in sub-Saharan Africa (i.e. Eastern, Middle or Southern Africa), study year, ethnicity of the study subjects, and the World-Bank-determined income level of the study country.41 Random-effects univariate meta-regression analysis40 was also performed as an extension of the subgroup analyses.

The potential influence of each individual study on the overall summary estimates was assessed by rerunning the meta-analysis while omitting one study at a time. Sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the impact of the quality of the studies on the overall effect estimates. For those studies that reported both crude and age-adjusted prevalences, we also assessed if the effect estimates would have been substantially altered if the age-adjusted values had been used instead of the crude ones.

Publication bias40 was assessed using a funnel plot to examine the relationship between the effect size and study precision. Begg and Mazumdar’s rank-correlation test40 was then used to test this relationship statistically. Finally, Duval and Tweedie’s “trim and fill” analysis was used to assess the possible impact of publication bias on the effect size.40

Version 2 of the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software package (Biostat, Englewood, United States of America) was used for all of the statistical analyses. All statistical tests were two-sided. A P-value of < 0.05 was generally considered indicative of statistical significance.

Results

Literature search

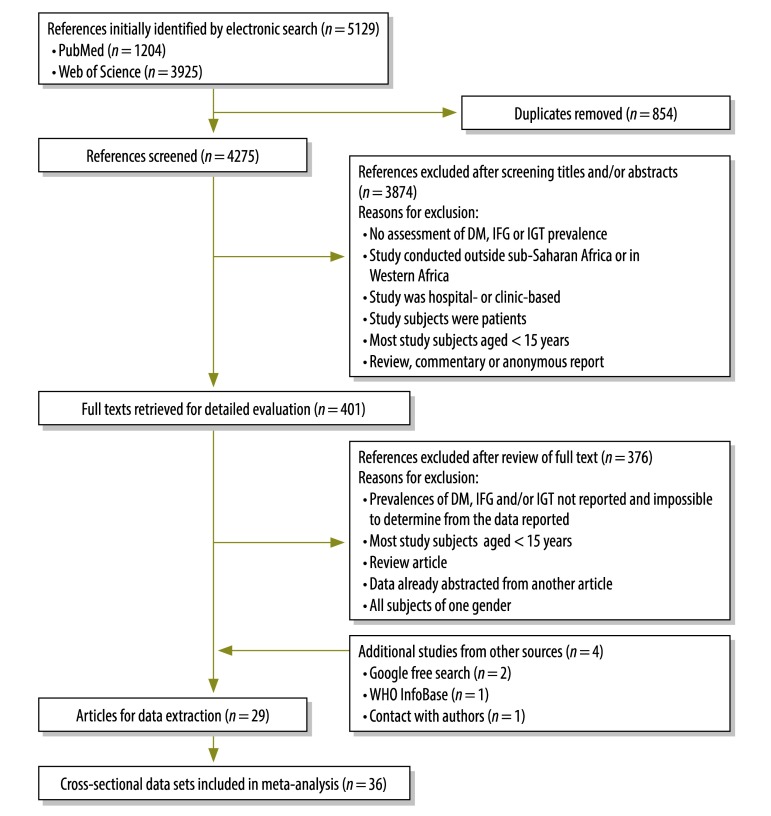

Although the PubMed and Web of Science searches revealed 5129 potentially useful reports, only 25 of these reports were found to satisfy all of the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Four additional reports that met all of the inclusion criteria were identified via a Google search (n = 2), a search of the WHO InfoBase (n = 1) or contact with authors (n = 1). The meta-analysis therefore included data from 29 reports that, together, covered 36 studies in which cross-sectional data were collected.14,17,42–68

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection procedure

DM, diabetes mellitus; IFG, impaired fasting glycaemia; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance.

Study characteristics

Table 2 (available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/91/9/12-113415) provides detailed descriptive information for the 36 studies included in the meta-analysis. These studies involved 75 928 subjects and were conducted between 1983 and 2009 in Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Seychelles, South Africa, Sudan, Uganda, the United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia or Zimbabwe. Most (92%) of the studies included in the meta-analysis employed probability- or census-sampling techniques and had response rates of 62–99%. Sex-specific prevalences of diabetes mellitus, impaired fasting glycaemia and impaired glucose tolerance were included in the reports of 35, 21 and 11 of the studies, respectively. Almost half (45%) of the studies were conducted in both urban and rural areas. The other studies were conducted exclusively in urban (26%), rural (23%) or periurban (6%) areas. In terms of quality, the studies were categorized as either “positive” (n = 31) or “neutral” (n = 5)42,49,58,61,63 (Appendix A, available at: http://www.med.nagoya-u.ac.jp/intnl-h/swfu/d/auto-UZzMJC.pdf).

Table 2. Descriptions of the cross-sectional data sets included in the meta-analysis.

| Authors | Year |

Study area |

Sampling method | Response rate (%) | Target population | Age (years) | No. of adults |

Mean agea (years) | Diagnosis |

Outcomes assessed | Prevalence (%)b |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publication | Study | Location | Type | Men | Women | Criteria | Method | Specimen | Men | Women | ||||||||

| Ahrén and Corrigan51 | 1984 | 1983 | Mwanza, URT | Urban | Cluster | 95 | All inhabitants | ≥ 20 | 161c | 215c | 35.4c | WHO 1980 | FBG and/or OGTT | cWB | DM | 1.87c | 1.86c | |

| Ahrén and Corrigan51 | 1984 | 1983 | Kahangala and Ndolage, URT | Rural | Cluster | 90 | All inhabitants | ≥ 20 | 360c | 489c | 43.3c | WHO 1980 | FBG and/or OGTT | cWB | DM | 1.1c | 1.84c | |

| Omar et al.46 | 1985 | NR | Durban, South Africa | Urban | Cluster | 77 | Adults | ≥ 15 | 368 | 498 | 42.5 | WHO 1985 | FBG and OGTT | VP | DM | 7.6 | 13.5 | |

| IGT | 7.1 | 4.8 | ||||||||||||||||

| Söderberg et al.43 | 2005 | 1987 | Mauritius | Combined | Multistage cluster | 86 | Adults | 25–74 | 2339 | 2652 | 43.3 | WHO 1999 | FBG and OGTT | VP | DM | 14.3 (13.0) | 13.7 (12.6) | |

| IFG | 5.1 (5.1) | 2.7 (2.6) | ||||||||||||||||

| IGT | 13.2 (12.7) | 19.4 (19.1) | ||||||||||||||||

| McLarty et al.14 | 1989 | 1988d | Morogoro and Kilimanjaro, URT | Rural | Random | 92.6 | Adults | ≥ 15 | 2623 | 3460 | 37 | WHO 1985 | FBG and/or OGTT | vWB | DM | 1.1 | 0.7 | |

| IGT | 7.3 | 8.0 | ||||||||||||||||

| Tappy et al.66 | 1991 | 1989 | Mahe, Seychelles | Urban | Stratified random | 86.4 | Adults | 25–64 | 511 | 567 | NR | ADA 1988 | FBG | vWB | DM | NR (3.4) | NR (4.6) | |

| Levitt et al.53 | 1993 | 1990 | Cape Town, South Africa | Urban | Cluster | 79 | Adults | > 30 | 210 | 504 | 45.1 | WHO 1985 | FBG and OGTT | VP | DM | 6.5 (6.9) | 6.4 (7.4) | |

| IGT | 6.0 | 5.9 | ||||||||||||||||

| Mollentze et al.68 | 1995 | 1990 | QwaQwa, South Africa | Rural | Random | 68 | Adults | ≥ 25 | 279 | 574 | 52.3 | WHO 1985 | FBG and OGTT | VP | DM | 5.4 | 6.6 | |

| Mollentze et al.68 | 1995 | 1990 | Mangaung, South Africa | Urban | Random | 62 | Adults | ≥ 25 | 290 | 468 | 48.6 | WHO 1985 | FBG and OGTT | VP | DM | 5.8 | 8.5 | |

| Söderberg et al.43 | 2005 | 1992 | Mauritius | Combined | Multistage cluster | 90 | Adults | ≥ 25 | 2986 | 3477 | 46 | WHO 1999 | FBG and OGTT | VP | DM | 19.3 (15.5) | 18.3 (15.0) | |

| IFG | 8.5 (8.2) | 4.1 (3.9) | ||||||||||||||||

| IGT | 13.0 (12.0) | 17.7 (16.3) | ||||||||||||||||

| Omar et al.64 | 1993 | NR | Umlazi, South Africa | Urban | Cluster | 78 | Adults | ≥ 15 | 141 | 338 | 32.9 | WHO 1985 | FBG and OGTT | VP | DM | 2.3 | 5.2 | |

| IGT | 11.5 | 5.5 | ||||||||||||||||

| Omar et al.59 | 1994 | NR | Durban, South Africa | Urban | Cluster | 92 | Adults | ≥ 15 | 1038 | 1441 | NR | WHO 1985 | FBG and OGTT | VP | DM | 8.6 (10.4) | 10.6 (15.0) | |

| IGT | 7.6 (8.9) | 4.5 (5.8) | ||||||||||||||||

| Elbagir et al.17 | 1996 | NR | Sudan | Combined | Multistage | NR | Adults | ≥ 25 | 461 | 823 | 46.1 | WHO 1985 | OGTT | cWB | DM | 3.5 | 3.4 | |

| IGT | 2.2 | 3.3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Levitt et al.52 | 1999 | 1996 | Mamre, South Africa | Periurban | Cluster | 64.5 | Adults | ≥ 15 | 428 | 545 | 37.6 | WHO 1985 | OGTT | VP | DM | 5.8 | 8.1 | |

| IGT | 6.5 | 9.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Erasmus et al.67 | 2001 | 1997d | Umtata, South Africa | Periurban | NR | 73 | Adults | 20–69 | 237 | 137 | 37.9 | WHO 1985 | FBG and OGTT | VP | DM | 2.1 | 2.9 | |

| IGT | 3.4 | 1.5 | ||||||||||||||||

| Aspray et al.45 | 2000 | 1997 | Ilala Ilala and Dar es Salaam, URT | Urban | Random | 73.25 | Adults | ≥ 15 | 332 | 438 | 30.6 | WHO 1998 | FBG | cWB | DM | 5.3 (5.9) | 4.0 (5.7) | |

| IFG | 4.0 (3.6) | 5.4 (4.7) | ||||||||||||||||

| Aspray et al.45 | 2000 | 1997 | Shari, URT | Rural | Random | 82.5 | Adults | ≥ 15 | 401 | 527 | 42.1 | WHO 1998 | FBG | cWB | DM | 1.5 (1.7) | 1.1 (1.1) | |

| IFG | 1.2 (0.8) | 1.5 (1.6) | ||||||||||||||||

| Charlton et al.61 | 2001 | 1997 | St Helena Bay and Velddrif, South Africa | Rural | Convenience | NR | Adults | > 55 | 46 | 106 | 65.4 | WHO 1985; ADA 1997 | FBG and OGTT | VP | DM | 15.8 | 28.9 | |

| IGT | 13.2 | 10.0 | ||||||||||||||||

| Alberts et al.56 | 2005 | 1997d | Limpopo, South Africa | Rural | Census | 66 | Adults | > 30 | 498 | 1608 | 57.5 | ADA 1997 | FBG | VP | DM | 9.9 (8.5) | 10.0 (8.8) | |

| Söderberg et al.43 | 2005 | 1998 | Mauritius | Combined | Multistage cluster | 87 | Adults | ≥ 20 | 2392 | 3000 | 48.8 | WHO 1999 | FBG and OGTT | VP | DM | 25.2 (18.3) | 23.8 (17.6) | |

| IFG | 5.7 (6.2) | 3.5 (2.9) | ||||||||||||||||

| IGT | 13.2 (11.2) | 17.2 (16.2) | ||||||||||||||||

| Elbagir et al.48 | 1998 | NR | Northern State, Sudan | Urban | Multistage | NR | Adults | ≥ 25 | 118 | 197 | 38 | WHO 1985 | OGTT | cWB | DM | NR (15.8) | NR (10.7) | |

| IGT | NR (4.5) | NR (13.5) | ||||||||||||||||

| Elbagir et al.48 | 1998 | NR | Northern State, Sudan | Rural | Multistage | NR | Adults | ≥ 25 | 43 | 126 | 39 | WHO 1985 | OGTT | cWB | DM | NR (2.8) | NR (8.3) | |

| IGT | NR (4.4) | NR (10.2) | ||||||||||||||||

| Motala et al.50 | 2008 | 2000d | Ubombo district, South Africa | Rural | Cluster | 78.9 | Adults | ≥ 15 | 200 | 799 | 46.9 | WHO 1998 | FBG and OGTT | VP | DM | 4.5 (3.5) | 4.6 (3.9) | |

| IFG | 4.5 (4.0) | 0.9 (0.8) | ||||||||||||||||

| IGT | 6.5 (4.0) | 6.4 (4.7) | ||||||||||||||||

| Faeh et al.55 | 2007 | 2004 | Seychelles | Urban | Stratified random | 80.2 | Adults | 25–64 | 568 | 687 | 45.2 | ADA 2004 | FBG and/or OGTT | VP | DM | NR (11.0) | NR (12.1) | |

| IFG | NR (30.4) | NR (18.0) | ||||||||||||||||

| IGT | NR (11.2) | NR (9.6) | ||||||||||||||||

| ZWMoH63 | 2005 | 2005 | Zimbabwe | Combined | Multistage cluster | 72.1 | Adults | ≥ 25 | 402 | 1264 | 48 | WHO 1999 | FBG and OGTT | VP | DM | 2.2 | 1.3 | |

| IGT | 5.3 | 5.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Kasiam Lasi On’Kin et al.57 | 2008 | 2005 | Kinshasa, DRC | Combined | Multistage cluster | 90.3 | All inhabitants | > 12 | 4580 | 5190 | 46 | WHO/ADA 2003 | FBG and OGTT | cWB | DM | NR (23.7) | NR (17.7) | |

| IFG | NR (9.5 | NR (9.2) | ||||||||||||||||

| IGT | NR (6.4) | NR (8.2) | ||||||||||||||||

| Silva-Matos et al.60 | 2011 | 2005 | Mozambique | Urbane | Cluster | 70.5 | Adults | 25–64 | NR | NR | 39 | WHO 1998 | FBG | cWB | DM | 5.5 | 4.9 | |

| IFG | 3.2 | 2.0 | ||||||||||||||||

| Silva-Matos et al.60 | 2011 | 2005 | Mozambique | Rurale | Cluster | 70.5 | Adults | 25–64 | NR | NR | 39 | WHO 1998 | FBG | cWB | DM | 2.4 | 1.2 | |

| IFG | 2.3 | 2.6 | ||||||||||||||||

| Nsakashalo-Senkwe et al.49 | 2011 | 2005 | Lusaka, Zambia | Urban | Multistage cluster | NR | Adults | 25–64 | 620 | 1260 | 42.1 | WHOf | FBG | cWB | DM | 2.1 | 3.0 | |

| IFG | 1.3 | 1.3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Christensen et al.47 | 2009 | 2006 | Luo, Kamba, Maasai and Nairobi, Kenya | Combined | Random | 98.2 | All inhabitants | ≥ 17 | 640 | 819 | 37.5 | WHO 1999 | FBG and OGTT | vWB | DM | NR (4.5) | NR (4.2) | |

| IGT | NR (6.1) | NR (13.1) | ||||||||||||||||

| Tibazarwa et al.42 | 2009 | 2007 | Soweto, South Africa | Urban | Convenience | 94 | Adults | NR | 594 | 1097 | 46 | WHO 1985 | RBG | cWB | DM | 3.5 | 3.0 | |

| Wanjihia et al.44 | 2009 | 2008d | Bondo and Kericho, Kenya | Rural | Random | 99.6 | All inhabitants | ≥ 18 | 134 | 165 | 43 | WHO 1999 | FBG and OGTT | cWB | IGT | 3.7 | 11.9 | |

| Mathenge et al.65 | 2010 | 2008 | Nakuru district, Kenya | Urban | Cluster | 88 | Adults | ≥ 50 | 707d | 730d | 60.8d | WHO 1985 | RBG | cWB | DM | 9.9 | 9.9 | |

| Mathenge et al.65 | 2010 | 2008 | Nakuru district, Kenya | Rural | Cluster | 88 | Adults | ≥ 50 | 1399d | 1560d | 64.7d | WHO 1985 | RBG | cWB | DM | 4.9 | 4.9 | |

| MWMoH54 | 2010 | 2009 | Malawi | Combined | Multistage cluster | 95.5 | Adults | 25–64 | 1690 | 3516 | 32.9 | WHO 1999 | FBG | cWB | DM | 6.5 | 4.7 | |

| IFG | 5.7 | 2.7 | ||||||||||||||||

| Evaristo-Neto et al.58 | 2010 | NR | Bengo, Angola | Rural | Multistage cluster | 97 | Adults | 30–69 | 126 | 295 | 49.6 | WHO 1985 | FBG and OGTT | cWB | DM | 3.2 | 2.7 | |

| IGT | 5.6 | 9.1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Maher et al.62 | 2011 | 2009 | South-western Uganda | Rural | Census | 65.6 | All inhabitants | ≥ 13 | 2719 | 3959 | 32.9 | WHO 2006 | RBG | VP | DM | NR (0.4) | NR (0.4) | |

ADA, American Diabetes Association; cWB, capillary whole blood; DM , diabetes mellitus; DRC, Democratic Republic of the Congo; FBG, fasting blood glucose; IFG, impaired fasting glycaemia; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; MWMoH, Malawi Ministry of Health; NR, not reported; OGTT, oral glucose-tolerance test; RBG, random blood glucose; URT, United Republic of Tanzania; VP, venous plasma; vWB, venous whole blood; WHO, World Health Organization; ZWMoH, Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Welfare.

a If never reported, estimated from the age distribution of subjects.

b Values shown are crude prevalences followed, in parentheses, by the age-adjusted values (when reported).

c Data for study subjects aged ≥ 20 years.

d Previously unpublished information, supplied by an author of the cited report.

e For the meta-analysis, pooled data for all of the study areas investigated by Silva-Matos et al.60 (i.e. those for urban and rural areas combined) were used.

f Year not reported.

Sex-specific prevalences

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus was 5.7% (95% CI: 4.8–6.8) overall, with a slight difference between the men (5.5%; 95% CI: 4.1–7.2) and women (5.9%; 95% CI: 4.6–7.6) included in the meta-analysis. The prevalence of impaired fasting glycaemia was 4.5% (95% CI: 3.3–6.1) overall – 5.7% (95% CI: 3.7–8.6) among the men and 3.5% (95% CI: 2.1–5.8) among the women – whereas the prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance was 7.9% (95% CI: 6.7–9.2) overall – 7.3% (95% CI: 6.0–8.8) among the men and 8.5% (95% CI: 6.7–10.7) among the women.

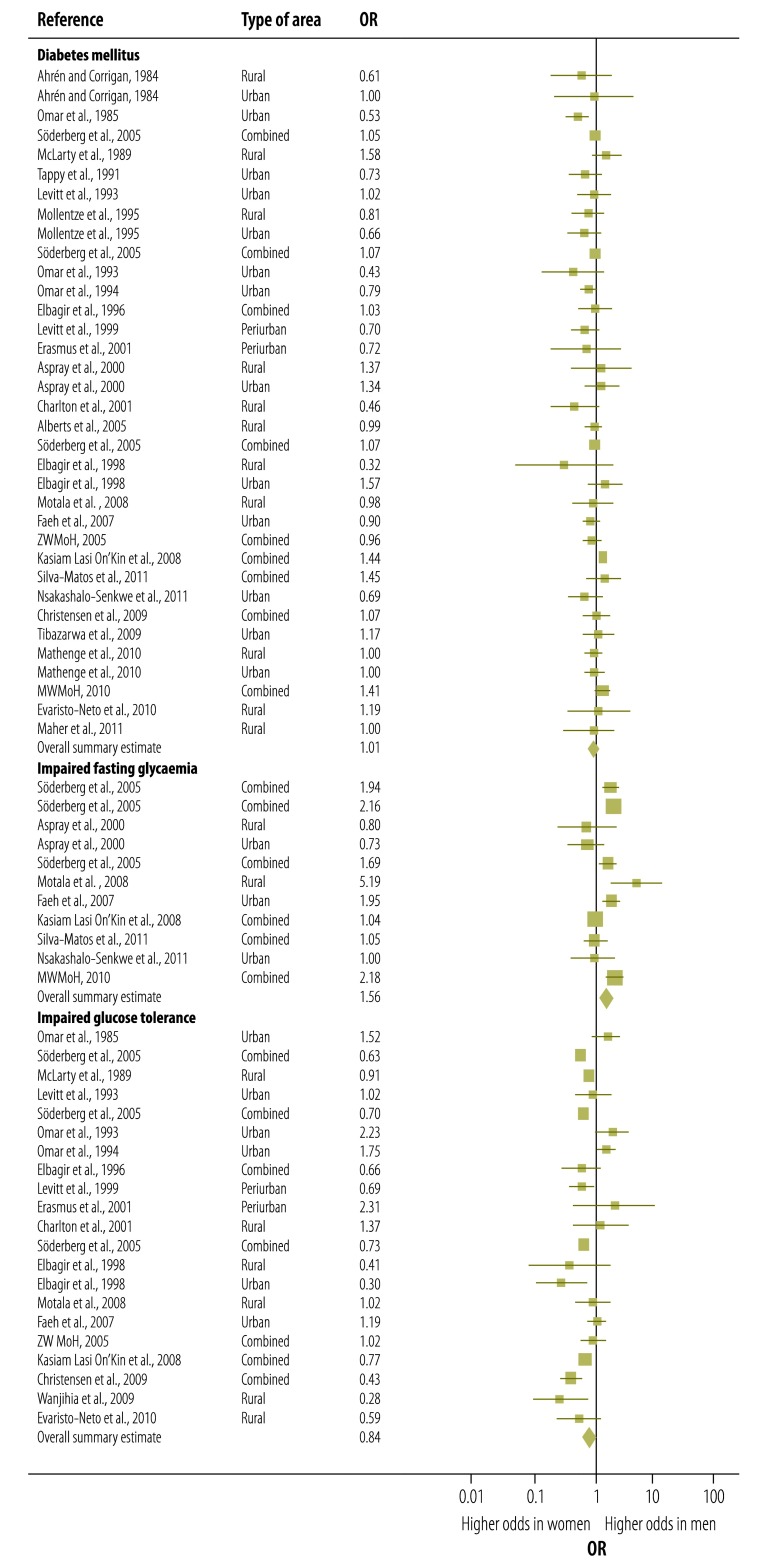

Odds ratios

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus among men was not significantly different from that among women (OR: 1.01; 95% CI: 0.91–1.11). However, impaired fasting glycaemia appeared to be significantly more common among men than among women (OR: 1.56; 95% CI: 1.20–2.03), whereas impaired glucose tolerance appeared to be significantly less common among men than among women (OR: 0.84; 95% CI: 0.72–0.98) (Fig. 2). These significant differences between the sexes were still observed when the analysis was restricted to those studies in which the prevalences of both impaired fasting glycaemia and impaired glucose tolerance were determined in the same study cohorts (data not shown). A moderate to substantial level of heterogeneity between studies was detected in the data for diabetes mellitus (I2 = 54.62%; P < 0.001 in Q-test), impaired fasting glycaemia (I2 = 85.38%; P < 0.001 in Q-test) and impaired glucose tolerance (I2 = 74.13%; P < 0.001 in Q-test).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of main meta-analysis results, showing sex-specific odds ratios for diabetes mellitus, impaired fasting glycaemia and impaired glucose tolerance in sub-Saharan Africa

DM, diabetes mellitus; IFG, impaired fasting glycaemia; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; MWMoH, Malawi Ministry of Health; OR, odds ratio; ZWMoH, Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Welfare.

Note: The ORs shown are for differences in prevalence between the sexes (i.e. odds in men versus odds in women). For each study, the plot indicates the mean OR (midpoint of the square), the corresponding 95% confidence interval (horizontal lines) and the weight given to the study (area of the square).

Subgroup analyses

Table 3 summarizes the results of the subgroup analyses. Significant heterogeneity in the OR for diabetes mellitus was observed by area of residence (i.e. urban or rural), subregion of residence in Africa, ethnicity of the study subjects, and country income level – each of which gave a P- value of < 0.05 in a Q-test. The prevalence of diabetes mellitus was found to be significantly higher in men than in women in studies conducted in a mix of urban and rural areas, in Middle or Eastern Africa or in low-income countries. However, in studies conducted in Southern Africa or among subjects of Indian ethnicity, the prevalence of diabetes mellitus was significantly higher among women than among the corresponding men.

Table 3. Pooled odds ratios (ORs)a for diabetes mellitus and two associated risk factors.

| Variable | Diabetes mellitus |

Impaired fasting glycaemia |

Impaired glucose tolerance |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nb | OR (95% CI) | Pc | nb | OR (95% CI) | Pc | nb | OR (95% CI) | Pc | |||

| All data sets | 35 | 1.01 (0.91–1.11) | 11 | 1.56 (1.20–2.03) | 21 | 0.84 (0.72–0.98) | |||||

| Area of residence | 0.009 | 0.56 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Combined | 9 | 1.17 (1.04–1.31) | 6 | 1.61 (1.14–2.26) | 7 | 0.69 (0.59–0.81) | |||||

| Periurban | 2 | 0.70 (0.42–1.18) | 2 | 0.79 (0.46–1.37) | |||||||

| Rural | 11 | 0.98 (0.80–1.20) | 2 | 2.21 (0.87–5.64) | 6 | 0.82 (0.61–1.09) | |||||

| Urban | 13 | 0.86 (0.73–1.01) | 3 | 1.24 (0.71–2.19) | 6 | 1.33 (1.03–1.72) | |||||

| Subregion of residence | < 0.001 | 0.019 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| Middle Africa | 2 | 1.44 (1.31–1.59) | 1 | 1.04 (0.65–1.65) | 2 | 0.73 (0.49–1.09) | |||||

| Eastern Africa | 21 | 1.08 (1.01–1.15) | 9 | 1.65 (1.35–2.02) | 11 | 0.71 (0.59–0.84) | |||||

| Southern Africa | 12 | 0.80 (0.69–0.92) | 1 | 5.19 (1.75–15.38) | 8 | 1.30 (0.99–1.70) | |||||

| Ethnicity of subjects | 0.012 | 0.066 | 0.002 | ||||||||

| African | 24 | 1.12 (1.00–1.25) | 7 | 1.30 (0.96–1.74) | 11 | 0.81 (0.66–0.99) | |||||

| Indian | 2 | 0.69 (0.52–0.94) | 2 | 1.66 (1.10–2.50) | |||||||

| Multi-ethnic | 9 | 1.00 (0.87–1.14) | 4 | 1.93 (1.42–2.62) | 8 | 0.73 (0.60–0.89) | |||||

| Study year | 0.125 | 0.81 | 0.61 | ||||||||

| Before 1991 | 9 | 0.90 (0.73–1.11) | 1 | 1.94 (0.84–4.48) | 4 | 0.90 (0.62–1.31) | |||||

| 1991–1999 | 13 | 0.96 (0.83–1.12) | 4 | 1.41 (0.88–2.27) | 10 | 0.90 (0.68–1.19) | |||||

| After 1999 | 13 | 1.13 (0.99–1.30) | 6 | 1.58 (1.09–2.30) | 7 | 0.74 (0.55–1.01) | |||||

| Country income level | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.028 | ||||||||

| Low | 14 | 1.21 (1.06–1.37) | 6 | 1.18 (0.89–1.57) | 5 | 0.70 (0.52–0.95) | |||||

| Lower middle | 4 | 1.16 (0.75–1.80) | 4 | 0.50 (0.29–0.87) | |||||||

| Upper middle | 17 | 0.93 (0.83–1.03) | 5 | 2.05 (1.56–2.69) | 12 | 0.99 (0.80–1.23) | |||||

CI, confidence interval.

a ORs represent the odds in men versus the odds in women.

b Number of data sets included in the analysis.

c P-value for the category, estimated in a Q-test.

Significant heterogeneity in the OR for impaired fasting glycaemia was observed by subregion of residence in Africa (P = 0.02) and country income level (P = 0.006). In studies conducted in Eastern Africa or upper-middle-income countries, impaired fasting glycaemia appeared to be significantly more common among men than among women.

With impaired glucose tolerance, significant heterogeneity in the OR was observed by area of residence (P < 0.001), subregion of residence in Africa (P = 0.001), ethnicity (P = 0.002), and country income level (P = 0.03). The odds of impaired glucose tolerance were found to be higher in men than in women in studies conducted on urban residents or subjects of Indian ethnicity.

Meta-regression

In general, the univariate random-effects meta-regression revealed similar associations – between the OR and study-level covariates – as seen in the subgroup analyses (Appendix A). For example, the OR for the sex-specific prevalences of diabetes mellitus appeared to be significantly affected by area of residence (rural versus urban; P = 0.018), subregion of residence in Africa (Southern and Middle Africa versus Eastern Africa; P < 0.001), ethnicity of the study subjects (multi-ethnic versus Indian; P = 0.013), study year (1990s versus 2000s; P = 0.039), and country income level (low versus upper middle; P < 0.001). Subregion of residence (Eastern versus Southern Africa; P = 0.047) and country income level (low versus upper-middle; P = 0.006) also had a significant effect on the OR for impaired fasting glycaemia, whereas subregion of residence (Eastern versus Southern Africa; P < 0.001), ethnicity of study subjects (multi-ethnic versus Indian; P < 0.001), country income level (low versus upper-middle; P < 0.001), and area of residence – both rural versus urban (P < 0.001) and rural versus urban and rural combined (P = 0.003) – had significant effects on the OR for impaired glucose tolerance.

Sensitivity and influence analyses

No meaningful change in the OR was evident when the meta-analysis was rerun either with the data from the five studies of “neutral” quality omitted or using age-adjusted prevalences instead of the crude values (data not shown).

The results of the influence analysis indicated that the omission of the data from any of seven studies – described in five reports43,44,47,48,57 – could eliminate the statistical significance of the overall differences between men and women in the prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance. However, even when the data from one of these studies were omitted, women still showed a higher prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance than the corresponding men, with a P-value of > 0.05 but < 0.1. The pooled results for diabetes or impaired fasting glycaemia were not substantially affected by the omission of the data from any one study.

Publication bias

The funnel plots for diabetes mellitus and impaired fasting glycaemia were asymmetric, indicating possible publication bias. However, the corresponding results from Begg and Mazumdar’s rank-correlation tests – P-values of 0.93 and 0.64, respectively – were not statistically significant. Duval and Tweedie’s “trim and fill” analysis indicated that the meta-analysis would have benefitted from the inclusion of data from more studies – nine for diabetes mellitus and one for impaired fasting glycaemia – and that, if the asymmetry seen in the funnel plots was the result of publication bias, the summary estimates of the sex-specific (i.e. men versus women) OR for diabetes mellitus and impaired fasting glycaemia should be 1.09 (95% CI: 0.98–1.20) and 1.65 (95% CI: 1.27–2.14), respectively (Appendix A).

There were no indications of publication bias in the data on impaired glucose tolerance.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first systematic review of possible associations between sex and the prevalences of impairments in glucose tolerance and fasting glycaemia in Eastern, Middle and Southern Africa. Previous narrative reviews have reported on the prevalence of diabetes mellitus and, briefly, on the variation in the sex distribution of this illness in sub-Saharan Africa.3–5,7,20 However, there appears to have been only one previous meta-analysis of data on the prevalence of diabetes mellitus in sub-Saharan Africa and that was limited to data collected in West Africa.19

The present results reveal considerable between-country variation in the prevalence of diabetes mellitus among adults. However, the relatively high value recorded for all of the studies combined (5.7%) is a reflection of the rapid transition – from a predominance of communicable disease to one of noncommunicable disease – that much of sub-Saharan Africa is facing. In this vast area of Africa, important risk factors for diabetes mellitus, such as impaired glucose tolerance, appear to be increasing in prevalence while humans are tending to live longer. The prevalence of diabetes mellitus in sub-Saharan Africa will therefore probably rise further unless prevention efforts are intensified. 23

In the present meta-analysis – as in most22,24,69 – but not all70 – previous studies on this risk factor for diabetes mellitus – impaired fasting glucose was found to be significantly more common among men than among women, irrespective of the subgroup that was investigated. One possible explanation for this difference is that men tend to have lower hepatic sensitivity to insulin and may, in consequence, have generally higher fasting levels of plasma glucose.69 Another possible explanation or contributing factor is that, within sub-Saharan Africa, men are more likely to smoke than women71 and smoking appears to increase the risk of impaired fasting glucose, by decreasing insulin sensitivity.72–74

In earlier research, impaired glucose tolerance has generally been found to be more common among women than among men.22,24,69 The same difference between the sexes was detected in most of the subgroups that were investigated in the present meta-analysis. In general, women have a smaller mass of muscle than men and therefore less muscle available for the uptake of the fixed glucose load (75 g) used in the oral glucose-tolerance test.69,75 Women also have relatively high levels of estrogen and progesterone, both of which can reduce whole-body insulin sensitivity.76 Physical inactivity77 and unhealthy diet78 have also both been associated with impaired glucose tolerance. In many countries in sub-Saharan Africa, women are more likely to be physically inactive than the corresponding men.79,80

The differences in the sex distribution of both impaired fasting glycaemia and impaired glucose tolerance in sub-Saharan Africa need to be considered in evaluating the probability that individuals will develop diabetes mellitus and in efforts to prevent the disease. Impairments in glucose tolerance and in fasting glycaemia are not metabolically equivalent, and the people classified as having each condition are different as well.22,81 If screening programmes were based only on the measurement of “fasting plasma glucose”, most individuals with impaired glucose tolerance would go undetected and the population identified as being at risk would probably be biased towards males. The glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) assay69 may offer a way of evaluating the risk of diabetes mellitus that is relatively sex-neutral, although this assay is currently too expensive for routine use in Africa and it can also be affected by disorders such as malaria.82 Screening for both impaired fasting glycaemia and impaired glucose tolerance might eliminate most of the sex bias in the identification of those who are at risk of developing diabetes mellitus. Even then, the dose of glucose used in the oral glucose-tolerance test may have to be made lower for women than for men – or tailored to the height of the individual to be tested – to allow for the lower mean muscle mass in women and so prevent the over-diagnosis of impaired glucose tolerance in women.72

In the present meta-analysis, despite the differences seen by sex in impaired fasting glycaemia and impaired glucose tolerance, the overall prevalence of diabetes mellitus in men was found to be very similar to that in women. However, subgroup analyses revealed that diabetes mellitus was more common in the men who lived in Middle and Eastern Africa than in the women who lived in the same African subregions, whereas the women who lived in Southern Africa were more likely to have diabetes mellitus than the corresponding men. Such differences between the sexes were not seen in the earlier study on diabetes mellitus in West Africa.19 Some of these differences may be related to differences between the sexes in the prevalence of central obesity, which, as a risk factor for diabetes mellitus, is more predictive than peripheral obesity.83 Central obesity has been found to be more common in men than in women in Eastern Africa84,85 and more common in women than men in Southern Africa.86 However, such obesity cannot be used to explain why the men of Middle Africa are more likely to have diabetes mellitus than the women, as central obesity is more common among the women in this area than among the men.87 Behavioural risk factors, such as smoking and alcohol use, which are more common among the men of sub-Saharan Africa than among the women,3,71 might contribute to the prevalence of diabetes mellitus among the men of Middle Africa.

In the present meta-analysis, the income level of the country of residence – a proxy indicator of the economic status of the people in the country – appeared to contribute to the heterogeneity seen in the association between sex and the prevalence of diabetes mellitus. Women of low socioeconomic status in Australia,88 Canada,89 Germany90 and the United States of America91 appear to be at markedly higher risk of diabetes mellitus than the corresponding men. In a recent meta-analysis, the incidence of Type 2 diabetes mellitus among adults with low socioeconomic status was found to be generally higher in women than in men; it was suggested that the women who lived in impoverished areas were more likely to be obese, physically inactive and under high levels of psychosocial stress than the men in the same areas.92 In contrast, the results of the present meta-analysis indicated that men who lived in the low-income countries of sub-Saharan Africa were more likely to be diagnosed with diabetes mellitus than the corresponding women. This difference between the sexes may be a consequence of differences between men and women in the distribution of risk factors for diabetes mellitus (e.g. obesity, physical inactivity, poor diet and smoking, etc.) in low-income countries. Another possibility is that women in low-income countries have particularly poor access to health-care services and therefore little chance of being diagnosed with diabetes.88,89,91,92 In addition, as Africa is one of the most inequitable parts of the world in terms of income,93 the income level recorded for an African country might not correlate with the socioeconomic status of a study cohort in that country. There appear to be no published data sets that would allow sex-based differences in the relationship between individual socioeconomic status and diabetes mellitus in sub-Saharan Africa to be investigated.

The present meta-analysis had several limitations. First, the studies that provided the data for the meta-analysis were conducted under different circumstances in different countries and the prevalences of diabetes mellitus, impaired fasting glycaemia and/or impaired glucose tolerance were not the primary outcomes of some of the studies. A random-effects model was therefore employed to embrace this considerable heterogeneity.40 Second, the studies had to be cross-sectional in design to be included in the meta-analysis and may therefore have been affected by confounding and biases. However, we attempted to minimize selection bias by employing predefined study selection criteria and a quality appraisal checklist. Potential sources of heterogeneity were also assessed in subgroup and meta-regression analyses. Third, since our subgroup and meta-regression analyses were entirely observational in nature, the relationships recorded – across all of the studies – between some study-level characteristics and the effect estimate could be subject to confounding by other study-level characteristics. Unfortunately, the studies included in the meta-analysis were too few to allow for a reasonable assessment of interactions between the study-level covariates. Fourth, we used the income levels of the countries of residence to stratify the studies because of a general lack of information on the socioeconomic status of study participants. The relationships that we observed between a country’s income level and the sex-specific prevalences of interest may therefore not reflect the relationships between the socioeconomic status of the subjects and their risks of impaired fasting glycaemia, impaired glucose tolerance or diabetes mellitus. Finally, our conclusions may have been affected by publication bias. The asymmetric funnel plots were indicative of possible publication bias in the data for diabetes mellitus and impaired fasting glucose. Furthermore, our study selection criteria excluded reports that did not have an abstract in English and may have excluded some reports that were not recorded in the PubMed or Web of Science databases, although we did try to search the “grey” literature for relevant data. The results of the “trim and fill” analyses indicated that the impact of any publication bias on our conclusions was probably trivial.

In summary, our meta-analysis demonstrated that, compared with the corresponding women, the men in Eastern, Middle and Southern Africa had a significantly higher prevalence of impaired fasting glycaemia and a lower prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance. Although the overall prevalence of diabetes mellitus did not significantly differ by sex, the prevalence of diabetes mellitus was found to be lower or higher in women than in men when analysed by African subregion. Sex-based differences in the relationship between individual socioeconomic status and impaired fasting glycaemia, impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes mellitus still need to be investigated in sub-Saharan Africa. Our observations may help in the targeting of appropriate – and perhaps sex-specific – interventions to prevent diabetes mellitus in sub-Saharan Africa.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the authors of the articles included in the meta-analysis, many of whom kindly provided us with additional information regarding their studies.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Dalal S, Beunza JJ, Volmink J, Adebamowo C, Bajunirwe F, Njelekela M, et al. Non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: what we know now. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:885–901. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maher D, Smeeth L, Sekajugo J. Health transition in Africa: practical policy proposals for primary care. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:943–8. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.077891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.BeLue R, Okoror TA, Iwelunmor J, Taylor KD, Degboe AN, Agyemang C, et al. An overview of cardiovascular risk factor burden in sub-Saharan African countries: a socio-cultural perspective. Global Health. 2009;5:10. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gill GV, Mbanya J-C, Ramaiya KL, Tesfaye S. A sub-Saharan African perspective of diabetes. Diabetologia. 2009;52:8–16. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuei VC, Maiyoh GK, Ha C-E. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity in sub-Saharan Africa. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2010;26:433–45. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whiting DR, Guariguata L, Weil C, Shaw J. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2011 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;94:311–21. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imoisili OE, Sumner AE. Preventing diabetes and atherosclerosis in sub-Saharan Africa: should the metabolic syndrome have a role? Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2009;3:161–7. doi: 10.1007/s12170-009-0026-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mbanya JC, Ngogang J, Salah JN, Minkoulou E, Balkau B. Prevalence of NIDDM and impaired glucose tolerance in a rural and an urban population in Cameroon. Diabetologia. 1997;40:824–9. doi: 10.1007/s001250050755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michael C, Edelstein I, Whisson A, MacCullum M, O’Reilly I, Hardcastle A, et al. Prevalence of diabetes, glycosuria and related variables among a Cape Coloured population. S Afr Med J. 1971;45:795–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lasky D, Becerra E, Boto W, Otim M, Ntambi J. Obesity and gender differences in the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Uganda. Nutrition. 2002;18:417–21. doi: 10.1016/S0899-9007(01)00726-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amoah AGB, Owusu SK, Adjei S. Diabetes in Ghana: a community based prevalence study in Greater Accra. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2002;56:197–205. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8227(01)00374-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ejim EC, Okafor CI, Emehel A, Mbah AU, Onyia U, Egwuonwu T, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in the middle-aged and elderly population of a Nigerian rural community. J Trop Med. 2011;2011:308687. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1997.d01-265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ceesay MM, Morgan MW, Kamanda MO, Willoughby VR, Lisk DR. Prevalence of diabetes in rural and urban populations in southern Sierra Leone: a preliminary survey. Trop Med Int Health. 1997;2:272–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1997.d01-265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLarty DG, Swai AB, Kitange HM, Masuki G, Mtinangi BL, Kilima PM, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in rural Tanzania. Lancet. 1989;1:871–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(89)92866-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baldé N-M, Diallo I, Baldé M-D, Barry I-S, Kaba L, Diallo M-M, et al. Diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in rural and urban populations in Futa Jallon (Guinea): prevalence and associated risk factors. Diabetes Metab. 2007;33:114–20. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisch A, Pichard E, Prazuck T, Leblanc H, Sidibe Y, Brücker G. Prevalence and risk factors of diabetes mellitus in the rural region of Mali (West Africa): a practical approach. Diabetologia. 1987;30:859–62. doi: 10.1007/BF00274794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elbagir MN, Eltom MA, Elmahadi EM, Kadam IM, Berne C. A population-based study of the prevalence of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in adults in northern Sudan. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:1126–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.10.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Njelekela MA, Mpembeni R, Muhihi A, Mligiliche NL, Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E, et al. Gender-related differences in the prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors and their correlates in urban Tanzania. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2009;9:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-9-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abubakari AR, Lauder W, Jones MC, Kirk A, Agyemang C, Bhopal RS. Prevalence and time trends in diabetes and physical inactivity among adult West African populations: the epidemic has arrived. Public Health. 2009;123:602–14. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mbanya JCN, Motala AA, Sobngwi E, Assah FK, Enoru ST. Diabetes in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet. 2010;375:2254–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60550-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nathan DM, Davidson MB, DeFronzo RA, Heine RJ, Henry RR, Pratley R, et al. American Diabetes Association Impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance: implications for care. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:753–9. doi: 10.2337/dc07-9920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Unwin N, Shaw J, Zimmet P, Alberti KGMM. Impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glycaemia: the current status on definition and intervention. Diabet Med. 2002;19:708–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.IDF Diabetes Atlas, 5th edition [Internet]. Africa (AFR). Brussels: International Diabetes Federation; 2012. Available from: http://www.idf.org/diabetesatlas/5e/africa [accessed 23 April 2013].

- 24.Williams JW, Zimmet PZ, Shaw JE, de Courten MP, Cameron AJ, Chitson P, et al. Gender differences in the prevalence of impaired fasting glycaemia and impaired glucose tolerance in Mauritius. Does sex matter? Diabet Med. 2003;20:915–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.01059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ, de Courten M, Dowse GK, Chitson P, Gareeboo H, et al. Impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance. What best predicts future diabetes in Mauritius? Diabetes Care. 1999;22:399–402. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De-Graft Aikins A, Marks D. Health, disease and healthcare in Africa. J Health Psychol. 2007;12:387–402. doi: 10.1177/1359105307076228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ, Danaei G, Lin JK, Paciorek CJ, et al. Global Burden of Metabolic Risk Factors of Chronic Diseases Collaborating Group (Body Mass Index) National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9·1 million participants. Lancet. 2011;377:557–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Composition of macro geographical (continental) regions, geographical sub-regions, and selected economic and other groupings [Internet]. New York: United Nations; 2011. Available from: http://unstats.un.org/unsd/methods/m49/m49regin.htm [accessed 23 April 2013].

- 29.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) Group Meta-analysis of observational studies: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.WHO Expert Committee on Diabetes Mellitus: second report Geneva: World Health Organization; 1980. Available from: whqlibdoc.who.int/trs/WHO_TRS_646.pdf [accessed 23 April 2031]. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diabetes mellitus: report of a WHO Study Group Geneva: World Health Organization; 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycemia: report of a WHO/IDF consultation Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15:539–53. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications, report of a WHO consultation. Part I: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus Geneva: World Health Organization; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Diabetes Data Group Classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and other categories of glucose intolerance. Diabetes. 1979;28:1039–57. doi: 10.2337/diab.28.12.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.American Diabetes Association Expert Committee Report of the Expert Committee on the Description of Diabetes Categories of Glucose. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(Suppl 1):S5–20. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.S5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(Suppl 1):S4–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1183–97. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.7.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quality criteria checklists [Internet]. Green Bay: University of Wisconsin; 2005. Available from: http://www.uwgb.edu/laceyk/NutSci486/EA%20Quality%20Criteria%20Checklists.doc [accessed 1 April 2013].

- 40.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to meta-analysis John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 41.World Bank list of economies (April 2012) [Internet]. Washington: World Bank; 2012. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications/country-and-lending-groups [accessed 1 April 2013].

- 42.Tibazarwa K, Ntyintyane L, Sliwa K, Gerntholtz T, Carrington M, Wilkinson D, et al. A time bomb of cardiovascular risk factors in South Africa: results from the Heart of Soweto Study “Heart Awareness Days”. Int J Cardiol. 2009;132:233–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Söderberg S, Zimmet P, Tuomilehto J, de Courten M, Dowse GK, Chitson P, et al. Increasing prevalence of Type 2 diabetes mellitus in all ethnic groups in Mauritius. Diabet Med. 2005;22:61–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wanjihia VW, Kiplamai FK, Waudo JN, Boit MK. Post-prandial glucose levels and consumption of omega 3 fatty acids and saturated fats among two rural populations in Kenya. East Afr Med J. 2009;86:259–66. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v86i6.54135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aspray TJ, Mugusi F, Rashid S, Whiting D, Edwards R, Alberti KG, et al. Essential Non-Communicable Disease Health Intervention Project Rural and urban differences in diabetes physical inactivity and urban living prevalence in Tanzania : the role of obesity, physical activity and urban living. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94:637–44. doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(00)90216-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Omar MA, Seedat MA, Dyer RB, Rajput MC, Motala AA, Joubert SM. The prevalence of diabetes mellitus in a large group of South African Indians. S Afr Med J. 1985;67:924–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Christensen DL, Friis H, Mwaniki DL, Kilonzo B, Tetens I, Boit MK, et al. Prevalence of glucose intolerance and associated risk factors in rural and urban populations of different ethnic groups in Kenya. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;84:303–10. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elbagir MN, Eltom MA, Elmahadi EM, Kadam IMS, Berne C. A high prevalence of diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in the Danagla community in northern Sudan. Diabet Med. 1998;15:164–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199802)15:2<164::AID-DIA536>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nsakashalo-Senkwe M, Siziya S, Goma FM, Songolo P, Mukonka V, Babaniyi O. Combined prevalence of impaired glucose level or diabetes and its correlates in Lusaka urban district, Zambia: a population based survey. Int Arch Med. 2011;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1755-7682-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Motala AA, Esterhuizen T, Gouws E, Pirie FJ, Omar MAK. Diabetes and other disorders of glycemia in a rural South African community: prevalence and associated risk factors. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1783–8. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahrén B, Corrigan CB. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus in north-western Tanzania. Diabetologia. 1984;26:333–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00266032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Levitt NS, Steyn K, Lambert EV, Reagon G, Lombard CJ, Fourie JM, et al. Modifiable risk factors for Type 2 diabetes mellitus in a peri-urban community in South Africa. Diabet Med. 1999;16:946–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.1999.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Levitt NS, Katzenellenbogen JM, Bradshaw D, Hoffman MN, Bonnici F. The prevalence and identification of risk factors for NIDDM in urban Africans in Cape Town, South Africa. Diabetes Care. 1993;16:601–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.4.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Malawi national STEPS survey for chronic non-communicable diseases and their risk factors. Final report Lilongwe: Malawi Ministry of Health, World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/steps/Malawi_2009_STEPS_Report.pdf [accessed 1 April 2013].

- 55.Faeh D, William J, Tappy L, Ravussin E, Bovet P. Prevalence, awareness and control of diabetes in the Seychelles and relationship with excess body weight. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:163. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alberts M, Urdal P, Steyn K, Stensvold I, Tverdal A, Nel JH, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular diseases and associated risk factors in a rural black population of South Africa. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2005;12:347–54. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000174792.24188.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kasiam Lasi On’Kin JB, Longo-Mbenza B, Okwe N, Kabangu NK, Mpandamadi SD, Wemankoy O, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of diabetes mellitus in Kinshasa hinterland. Int J Diabetes & Metab. 2008;16:97–106. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Evaristo-Neto AD, Foss-Freitas MC, Foss MC. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in a rural community of Angola. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2010;2:63. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-2-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Omar MA, Seedat MA, Dyer RB, Motala AA, Knight LT, Becker PJ. South African Indians show a high prevalence of NIDDM and bimodality in plasma glucose distribution patterns. Diabetes Care. 1994;17:70–3. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Silva-Matos C, Gomes A, Azevedo A, Damasceno A, Prista A, Lunet N. Diabetes in Mozambique: prevalence, management and healthcare challenges. Diabetes Metab. 2011;37:237–44. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Charlton KE, Schloss I, Visser M, Lambert EV, Kolbe T, Levitt NS, et al. Waist circumference predicts clustering of cardiovascular risk factors in older South Africans. Cardiovasc J S Afr. 2001;12:142–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maher D, Waswa L, Baisley K, Karabarinde A, Unwin N, Grosskurth H. Distribution of hyperglycaemia and related cardiovascular disease risk factors in low-income countries: a cross-sectional population-based survey in rural Uganda. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:160–71. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.National survey Zimbabwe non-communicable disease risk factors – (ZiNCoDs). Preliminary report Harare: Ministry of Health and Child Welfare; 2005. Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/steps/STEPS_Zimbabwe_Data.pdf [accessed 1 April 2013].

- 64.Omar MA, Seedat MA, Motala AA, Dyer RB, Becker P. The prevalence of diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in a group of urban South African blacks. S Afr Med J. 1993;83:641–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mathenge W, Foster A, Kuper H. Urbanization, ethnicity and cardiovascular risk in a population in transition in Nakuru, Kenya: a population-based survey. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:569. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tappy L, Bovet P, Shamlaye C. Prevalence of diabetes and obesity in the adult population of the Seychelles. Diabet Med. 1991;8:448–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1991.tb01630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Erasmus RT, Blanco Blanco E, Okesina AB, Matsha T, Gqweta Z, Mesa JA. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in factory workers from Transkei, South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2001;91:157–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mollentze WF, Moore AJ, Steyn AF, Joubert G, Steyn K, Oosthuizen GM, et al. Coronary heart disease risk factors in a rural and urban Orange Free State black population. S Afr Med J. 1995;85:90–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Færch K, Borch-Johnsen K, Vaag A, Jørgensen T, Witte DR. Sex differences in glucose levels: a consequence of physiology or methodological convenience? The Inter99 study. Diabetologia. 2010;53:858–65. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1673-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Satyavani K, Vijay V. Impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance in urban population in India. Diabet Med. 2003;20:220–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.00904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Townsend L, Flisher AJ, Gilreath T, King G. A systematic literature review of tobacco use among adults 15 years and older in sub-Saharan Africa. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;84:14–27. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Færch K, Vaag A, Witte DR, Jørgensen T, Pedersen O, Borch-Johnsen K. Predictors of future fasting and 2-h post-OGTT plasma glucose levels in middle-aged men and women – the Inter99 study. Diabet Med. 2009;26:377–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nakanishi N, Nakamura K, Matsuo Y, Suzuki K, Tatara K. Cigarette smoking and risk for impaired fasting glucose and type 2 diabetes in middle-aged Japanese men. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:183–91. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-3-200008010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rafalson L, Donahue RP, Dmochowski J, Rejman K, Dorn J, Trevisan M. Cigarette smoking is associated with conversion from normoglycemia to impaired fasting glucose: the Western New York Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:365–71. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sicree RA, Zimmet PZ, Dunstan DW, Cameron AJ, Welborn TA, Shaw JE. Differences in height explain gender differences in the response to the oral glucose tolerance test – the AusDiab study. Diabet Med. 2008;25:296–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.van Genugten RE, Utzschneider KM, Tong J, Gerchman F, Zraika S, Udayasankar J, et al. American Diabetes Association GENNID Study Group Effects of sex and hormone replacement therapy use on the prevalence of isolated impaired fasting glucose and isolated impaired glucose tolerance in subjects with a family history of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2006;55:3529–35. doi: 10.2337/db06-0577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Assah FK, Ekelund U, Brage S, Mbanya JC, Wareham NJ. Free-living physical activity energy expenditure is strongly related to glucose intolerance in Cameroonian adults independently of obesity. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:367–9. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Faerch K, Vaag A, Holst JJ, Hansen T, Jørgensen T, Borch-Johnsen K. Natural history of insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion in the progression from normal glucose tolerance to impaired fasting glycemia and impaired glucose tolerance: the Inter99 study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:439–44. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Guthold R, Ono T, Strong KL, Chatterji S, Morabia A. Worldwide variability in physical inactivity a 51-country survey. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34:486–94. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kruger A, Wissing MP, Towers GW, Doak CM. Sex differences independent of other psycho-sociodemographic factors as a predictor of body mass index in black South African adults. J Health Popul Nutr. 2012;30:56–65. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v30i1.11277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Abdul-Ghani MA, DeFronzo RA. Pathophysiology of prediabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2009;9:193–9. doi: 10.1007/s11892-009-0032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Use of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lee CMY, Huxley RR, Wildman RP, Woodward M. Indices of abdominal obesity are better discriminators of cardiovascular risk factors than BMI: a meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:646–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Christensen DL, Eis J, Hansen AW, Larsson MW, Mwaniki DL, Kilonzo B, et al. Obesity and regional fat distribution in Kenyan populations: impact of ethnicity and urbanization. Ann Hum Biol. 2008;35:232–49. doi: 10.1080/03014460801949870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Msamati BC, Igbigbi PS. Anthropometric profile of urban adult black Malawians. East Afr Med J. 2000;77:364–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Puoane T, Steyn K, Bradshaw D, Laubscher R, Fourie J, Lambert V, et al. Obesity in South Africa: the South African demographic and health survey. Obes Res. 2002;10:1038–48. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kasiam Lasi On’kin JB, Longo-Mbenza B, Nge Okwe A, Kangola Kabangu N. Survey of abdominal obesities in an adult urban population of Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2007;18:300–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kavanagh A, Bentley RJ, Turrell G, Shaw J, Dunstan D, Subramanian SV. Socioeconomic position, gender, health behaviours and biomarkers of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:1150–60. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tang M, Chen Y, Krewski D. Gender-related differences in the association between socioeconomic status and self-reported diabetes. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:381–5. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rathmann W, Haastert B, Icks A, Giani G, Holle R, Meisinger C, et al. KORA Study Group Sex differences in the associations of socioeconomic status with undiagnosed diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in the elderly population: the KORA Survey 2000. Eur J Public Health. 2005;15:627–33. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Robbins JM, Vaccarino V, Zhang H, Kasl SV. Socioeconomic status and type 2 diabetes in African American and non-Hispanic white women and men: evidence from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:76–83. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.1.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Agardh E, Allebeck P, Hallqvist J, Moradi T, Sidorchuk A. Type 2 diabetes incidence and socio-economic position: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:804–18. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Briefing notes for AfDB’ s long-term strategy. Briefing note 5: Income inequality in Africa [Internet]. Abidjan: African Development Bank Group; 2012. Available from: http://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Policy-Documents/FINAL%20Briefing%20Note%205%20Income%20Inequality%20in%20Africa.pdf [accessed 1 April 2013].