Abstract

Objective

To understand better the current regional situation and public health response to cervical cancer and female breast cancer in the Americas.

Methods

Data on cervical cancer and female breast cancers in 33 countries, for the period from 2000 to the last year with available data, were extracted from the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) Regional Mortality Database and analysed. Changes in mortality rates over the study period – in all countries except those with small populations and large fluctuations in time–series mortality data – were calculated using Poisson regression models. Information from the PAHO Country Capacity Survey on noncommunicable diseases was also analysed.

Findings

The Bahamas, Trinidad and Tobago and Uruguay showed relatively high rates of death from breast cancer, whereas the three highest rates of death from cervical cancer were observed in El Salvador, Nicaragua and Paraguay. Several countries – particularly Paraguay and Venezuela – have high rates of death from both types of cancer. Although mortality from cervical cancer has generally been decreasing in the Americas, decreases in mortality from breast cancer have only been observed in a few countries in the Region of the Americas. All but one of the 25 countries in the Americas included in the PAHO Country Capacity Survey reported having public health services for the screening and treatment of breast and cervical cancers.

Conclusion

Most countries in the Americas have the public health capacity needed to screen for – and treat – breast and cervical cancers and, therefore, the potential to reduce the burden posed by these cancers.

Résumé

Objectif

Mieux comprendre la situation régionale actelle et la réponse des services de santé publique face au cancer du col de l'utérus et au cancer du sein sur le continent américain.

Méthodes

Des données sur les cancers du sein et du col de l'utérus dans 33 pays, depuis l'année 2000 jusqu'à la dernière année de données disponibles, ont été extraites de la base de données sur la mortalité régionale de l'Organisation panaméricaine de la Santé (OPS) et ont ensuite été analysées. Les changements dans le taux de mortalité sur la période étudiée – dans tous les pays excepté ceux à faible population et à fortes fluctuations de données de mortalité en séries temporelles – ont été calculés au moyen de modèles log-linéaires. Les informations de l'enquête de capacité des pays de l'OPS sur les maladies non transmissibles ont également été analysées.

Résultats

On observe aux Bahamas, à Trinité et en Uruguay des taux relativement élevés de décès dus au cancer du sein, alors que les trois taux les plus élevés de décès dus au cancer du col de l'utérus ont été observés au Salvador, au Nicaragua et au Paraguay. Plusieurs pays - en particulier le Paraguay et le Venezuela - présentent des taux élevés de décès dus à ces deux types de cancer. Même si la mortalité liée au cancer du col de l'utérus est globalement en diminution sur le continent américain, les diminutions de la mortalité liée au cancer du sein n'ont été observées que dans quelques pays de la région. Mis à part un seul d'entre eux, les 25 pays concernés par l'enquête de capacité de l'OPS font état de la présence de services de santé publique pour la détection et le traitement des cancers du sein et du col de l'utérus.

Conclusion

La majorité des pays du continent américain disposent de la capacité nécessaire en matière de santé publique pour détecter et traiter les cancers du sein et du col de l'utérus et donc du potentiel pour réduire le fardeau que représentent ces cancers.

Resumen

Objetivo

Entender mejor la situación regional actual y la respuesta por parte de la sanidad pública al cáncer de cuello uterino y de mama femenino en las Américas.

Métodos

A partir de la Base de datos de mortalidad regional de la Organización Panamericana de la Salud (OPS) se obtuvieron y analizaron los datos sobre el cáncer de cuello uterino y de mama femenino en 33 países desde el año 2000 hasta el último año del que se disponen datos. Los cambios en las tasas de mortalidad durante el periodo de estudio (en todos los países, excepto en aquellos con poblaciones pequeñas y grandes fluctuaciones en ciclos temporales de datos sobre la mortalidad) se calcularon mediante modelos de regresión de Poisson. Asimismo, se analizó la información del Estudio de capacidad nacional de la OPS sobre enfermedades no transmisibles.

Resultados

Las Bahamas, Trinidad y Tobago y Uruguay mostraron tasas relativamente altas de mortalidad por cáncer de mama, mientras que en El Salvador, Nicaragua y Paraguay se observaron los tres mayores índices de mortalidad por cáncer de cuello uterino. Las tasas de mortalidad por ambos tipos de cáncer son elevadas en varios países, especialmente en Paraguay y Venezuela. Aunque la mortalidad por cáncer de cuello uterino, por lo general, ha ido disminuyendo en las Américas, sólo en algunos países de la Región de las Américas se ha podido constatar una disminución de la mortalidad por cáncer de mama. Según los informes, todos menos uno de los 25 países del continente americano incluidos en el Estudio de capacidad nacional de la OPS disponen de servicios de salud pública destinados a la detección y al tratamiento del cáncer de mama y de cuello uterino.

Conclusión

La sanidad pública de la mayoría de los países de las Américas tiene capacidad suficiente para detectar y tratar el cáncer de mama y de cuello uterino y, por tanto, el potencial necesario para reducir la carga que representan estos tipos de cáncer.

ملخص

الغرض

الفهم الأفضل للوضع الإقليمي الراهن واستجابة الصحة العمومية لسرطان عنق الرحم وسرطان الثدي لدى النساء في الأميركتين.

الطريقة

تم استخلاص البيانات المعنية بسرطان عنق الرحم وسرطان الثدي لدى النساء في 33 بلداً، من أجل الفترة من عام 2000 إلى السنة المنصرمة باستخدام البيانات المتاحة، من قاعدة بيانات الوفيات الإقليمية التابعة لمنظمة الصحة للبلدان الأمريكية وتحليلها. وتم حساب التغيرات في معدلات الوفيات على مدار فترة الدراسة – في جميع البلدان باستثناء البلدان ذات عدد السكان القليل وذات التراوح الكبير في بيانات وفيات السلاسل الزمنية - باستخدام نماذج ارتداد بواسون. وتم كذلك تحليل المعلومات المستخلصة من استقصاء منظمة الصحة للبلدان الأمريكية للقدرة القطرية المتعلقة بالأمراض غير السارية.

النتائج

أظهرت جزر البهاما وترينيداد وتوباغو وأورغواي معدلات وفاة عالية نسبياً ناجمة عن سرطان الثدي، بينما لوحظت أعلى ثلاثة معدلات وفاة ناجمة عن سرطان عنق الرحم في السلفادور ونيكاراغوا وباراغواي. وتضم عدة بلدان – ولاسيما باراغواي وفنزويلا - معدلات وفاة عالية ناجمة عن نمطي السرطان. وعلى الرغم من أن الوفيات الناجمة عن سرطان عنق الرحم انخفضت بشكل عام في الأميركتين، لم يتم ملاحظة انخفاضات في الوفيات الناجمة عن سرطان الثدي إلا في بضعة بلدان في الأميركتين. وأبلغ بلد واحد تقريباً من إجمالي 25 بلداً في الأميركتين المدرجة في استقصاء القدرة القطرية لمنظمة الصحة للبلدان الأمريكية عن اشتماله على خدمات الصحة العمومية من أجل فحص سرطان الثدي وسرطان عنق الرحم وعلاجهما.

الاستنتاج

تشتمل معظم البلدان في الأميركتين على قدرة الصحة العمومية اللازمة لفحص سرطان الثدي وسرطان عنق الرحم وعلاجهما، وبالتالي احتمال تقليل العبء الذي يفرضه هذان المرضين.

摘要

目的

更好地了解美洲子宫颈癌和女性乳腺癌的当前地区形势和公共卫生响应。

方法

从泛美卫生组织(PAHO)地区死亡率数据库中提取33 个国家2000 年到去年有关子宫颈癌和女性乳腺癌的可用数据并进行分析。使用泊松回归模型计算研究期间的死亡率变化(在所有国家中,人口少的国家以及时间序列死亡率数据波动大的国家除外)。还对PAHO有关非传染性疾病的国家能力调查的信息进行了分析。

结果

巴哈马、特立尼达和多巴哥以及乌拉圭的乳腺癌死亡率相对较高,而萨尔瓦多、尼加拉瓜和巴拉圭子宫颈癌的三种死亡率都最高。某些国家(尤其是巴拉圭和委内瑞拉)这两种癌症的死亡率都较高。虽然在美洲子宫颈癌的死亡率一直呈下降趋势,在美洲地区仅有少数国家出现乳腺癌死亡率下降趋势。在参与PAHO国家能力调查的25 个美洲国家中仅有一个国家报告提供筛查和治疗乳腺癌和子宫颈癌的公共卫生服务。

结论

美洲大多数国家需要有公共卫生能力以筛查(和治疗)乳腺癌和子宫颈癌,这样才能减少这两种癌症的潜在负担。

Резюме

Цель

Лучше понять текущую ситуацию в регионе и меры в области общественного здравоохранения по выявлению и лечению рака шейки матки и рака молочной железы у женщин в странах Америки.

Методы

Из региональной базы данных о смертности Панамериканской организации здравоохранения (ПАОЗ) были взяты и проанализированы данные о раке шейки матки и раке молочной железы у женщин в 33 странах за период с 2000 г. по прошлый год до даты, на которую имелись данные. С использованием модели регрессии Пуассона были рассчитаны изменения в показателях смертности за период исследования для всех стран, за исключением стран с небольшим населением и большими колебаниями временных рядов данных смертности. Также была проанализирована информация, полученная в результате анализа потенциала стран ПАОЗ в области борьбы с неинфекционными заболеваниями.

Результаты

Относительно высокие показатели смертности от рака молочной железы были выявлены на Багамских островах, в Тринидаде и Тобаго, а также Уругвае, а три самых высоких показателя смертности от рака шейки матки наблюдались в Сальвадоре, Никарагуа и Парагвае. В ряде стран — в частности, в Парагвае и Венесуэле — наблюдается высокий уровень смертности от обоих видов рака. Хотя смертность от рака шейки матки в странах Америки в целом снижается, снижение смертности от рака молочной железы в регионе стран Америки наблюдалось лишь в нескольких странах. Все, кроме одной из 25 стран Америки, включенных в анализ потенциала стран ПАОЗ, доложили о наличии служб общественного здравоохранения для обследования и лечения рака молочной железы и рака шейки матки.

Вывод

Большинство стран Северной и Южной Америки имеют потенциал общественного здравоохранения, необходимый для выявления, а также лечения рака молочной железы и рака шейки матки и, следовательно, потенциал для снижения угрозы, создаваемой этими видами рака.

Introduction

Cancer represents 30% of the burden posed by noncommunicable diseases in the Region of the Americas of the World Health Organization (WHO), where the leading causes of death have shifted from infectious diseases to noncommunicable diseases.1 Changes in demographic, social, economic and environmental factors, as well as life course changes – for example, changes in reproductive patterns – have contributed greatly to this epidemiological shift.2

Breast and cervical cancers are generally considered to be the most important cancers among women in the Americas, as they are among women worldwide.3 Globally, breast cancer incidence and mortality have increased over the past 30 years, at estimated annual rates of 3.1% and 1.8%, respectively. Over the same period, cervical cancer incidence and mortality have also increased, at estimated annual rates of 0.6% and 0.46%, respectively.4 The corresponding trends in the Americas have generally matched these global trends.5

These increases have occurred even though effective, population-based interventions are available for the control of breast and cervical cancers and the prevention of unnecessary deaths from these cancers. For cervical cancer, these interventions include vaccination against human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, screening based on cervical cytology, visual inspection of the cervix after applying acetic acid and testing for HPV DNA, and effective treatment for precancerous lesions and invasive cancer.6 WHO currently recommends the routine administration of HPV vaccine to girls – as part of a country’s national immunization programme – if cervical cancer is a public health priority in the country and if such HPV vaccination is programmatically feasible and sustainable and appears to be cost-effective in the country.7 If it is systematically applied with high coverage and quality assurance, cytological screening can reduce cervical cancer mortality by more than 50%.8 For breast cancer, the disease can be detected in its early stages through breast self-examination, clinical breast examination and mammography screening. The effectiveness of these strategies has been found to vary according to the resources available and the needs of the population involved.9 In general, however, mammography screening has led to a substantial reduction – estimated to be about 15% – in breast cancer mortality.10

The implementation of technologies that could reduce mortality from breast and cervical cancers continues to be a challenge in resource-constrained settings such as those often seen in the Caribbean and Latin America. This is especially true where several public health priorities compete for attention.

To assess the burden posed by breast and cervical cancers in the Americas and to understand the associated public health response, we reviewed the information on these cancers provided to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) by the relevant National Institutes of Vital Statistics and health ministry officials. We reviewed the temporal trends in mortality from breast and cervical cancers since 2000 and the results of a recent survey on the capacity of national programmes to prevent, screen for and treat noncommunicable diseases.

Methods

We extracted data – on mortality from breast and cervical cancers – from the PAHO Regional Mortality Database, which includes deaths that have been registered in national vital registration systems and reported annually to PAHO.11 The quality of the data from each country was evaluated by verifying the integrity and consistency of the data and validating selected variables (i.e. sex, age and underlying cause of death). An algorithm to correct for under-registration and ill-defined causes was applied to the data from countries that show more than 10% under-registration, more than 10% of deaths with an ill-defined cause, or both.12 For each of the 33 countries in WHO’s Region of the Americas with complete data, we included data from 2000 to the last year with reported data. This period was used because it was when each of the countries coded mortality using the International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision (ICD-10).

For breast cancer mortality, we extracted all deaths attributed to “female malignant neoplasm of breast” (i.e. ICD-10 code C50). For cervical cancer mortality, we extracted all deaths attributed to “malignant neoplasm of cervix uteri” (C53), “malignant neoplasm of corpus uteri” (C54) or “malignant neoplasm of uterus, part unspecified” (C55). We applied a reallocation algorithm – as used in similar analyses on trends and geographical comparisons13 – to reassign a proportion of the deaths coded as C55 to “malignant neoplasm of cervix uteri” (C53), based on the age- and time-specific distributions of the deaths. Eleven countries coded small proportions of their deaths among females (≤ 25% of the total number among women aged 30 years or older) as C55. For these countries – Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago and Venezuela – we reallocated the C55 deaths (unspecified) to C53 (cervix) or C54 (uterus), using the same ratio seen between the deaths coded C53 and those coded C54 – in the same data set – for the same country, year and age group. However, for the 13 countries that coded higher proportions of their deaths among women aged 30 years or older as C55 – Argentina, Belize, Canada, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Guyana, Paraguay, Peru, Puerto Rico, Uruguay and the United States of America – the deaths coded C55 for each year were reallocated to C53 or C54 using the same ratio seen between the deaths coded C53 and those coded C54 in an appropriate reference country in the same year. The reference countries used were Chile for the data from Argentina, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru and Uruguay; Mexico for the data from Belize, Canada, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Puerto Rico and the United States; and Trinidad and Tobago for the data from Guyana. The selection of the reference countries was based on the high quality of their vital statistics data, the consistently low proportions of their deaths that were coded C55, and their geographical, demographic and socioeconomic characteristics.

Age-standardized mortality rates were calculated using the world standard population.14 For those countries that did not have small populations and did not show large fluctuations in the time–series mortality data, annual changes in mortality rates were evaluated using Poisson regression models.

Information on the capacity of national public health programmes to deal with breast and cervical cancers was extracted – for the 25 countries in the Americas that provided the relevant data – from the PAHO Country Capacity Survey on noncommunicable diseases (S. Luciani, unpublished observations, 2013). This survey, which was conducted in April 2012, was based on a structured questionnaire which, for each targeted country, was sent to the health ministry staff members responsible for the national programme against noncommunicable diseases.

Results

In 2007, approximately 107 000 registered deaths in the Americas were attributed to female breast cancer (n = 82 370) or cervical cancer (n = 24 526),1 although another 12 240 deaths were reported as being from “cancer of the uterus, part unspecified” and some of these may have been from cervical cancer.

Breast cancer is the most common cause of cancer-related deaths among women in most countries in the Americas (Table 1). In Belize, El Salvador, Ecuador, Nicaragua, Paraguay and Peru, however, cervical cancer is the most common cause of cancer deaths among women (Table 2).

Table 1. Mortality from female breast cancer in the Region of the Americas, 2000–2009.

| Country or territory | Populationa (thousands) | GNIa (US$ per capita) | Mortality from female breast cancer |

APCd (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths in 2000 | ASMRb in 2000 | Latest yearc | Deaths in latest yearc | ASMRb in latest yearc | ||||

| North America | ||||||||

| Canada | 34 675 | 39 830 | 4857 | 18.1 | 2007 | 5066 | 15.6 | −2.25 (−2.67 to −1.83) |

| United States of America | 315 791 | 48 890 | 41 875 | 17.3 | 2007 | 40 600 | 14.8 | −2.19 (−2.34 to −2.04) |

| Mexico and Central America | ||||||||

| Belize | 324 | 6070 | 5 | 7.7 | 2008 | 12 | 12.8 | 3.58 (−5.55 to 13.6) |

| Costa Rica | 4794 | 11 950 | 183 | 10.6 | 2009 | 242 | 11.4 | 0.52 (−0.94 to 1.99) |

| El Salvador | 6264 | 6690 | 144 | 5.6 | 2008 | 233 | 7.7 | 3.52 (1.61 to 5.46) |

| Guatemala | 15 138 | 4800 | 177 | 4.2 | 2008 | 220 | 4.7 | ND |

| Mexico | 116 147 | 15 120 | 3433 | 8.7 | 2009 | 4803 | 9.0 | 0.39 (0.05 to 0.73) |

| Nicaragua | 5955 | 2840 | 153 | 9.7 | 2009 | 227 | 11.1 | −0.05 (−1.69 to 1.61) |

| Panama | 3625 | 14 740 | 169 | 13.3 | 2009 | 207 | 12.1 | −0.16 (−1.81 to 1.51) |

| South America | ||||||||

| Andean Area | ||||||||

| Colombia | 47 551 | 9640 | 1909 | 12.0 | 2008 | 2827 | 13.2 | 0.80 (0.27 to 1.32) |

| Ecuador | 14 865 | 8310 | 344 | 7.2 | 2009 | 593 | 9.2 | 1.87 (0.83 to 2.92) |

| Peru | 29 734 | 10 160 | 1187 | 12.0 | 2007 | 1261 | 10.2 | −0.46 (−1.35 to 0.44) |

| Venezuela | 29 891 | 12 620 | 1344 | 14.3 | 2007 | 1817 | 15.1 | 0.82 (0.05 to 1.59) |

| Brazil | 198 361 | 11 500 | 11 354 | 14.5 | 2009 | 15 769 | 14.9 | 0.09 (−0.10 to 0.27) |

| Southern Cone | ||||||||

| Argentina | 41 119 | 17 250 | 5026 | 19.9 | 2009 | 5378 | 17.8 | −1.21 (−1.51 to −0.92) |

| Chile | 17 423 | 16 160 | 1027 | 11.7 | 2008 | 1184 | 10.4 | −1.40 (−2.15 to −0.64) |

| Paraguay | 6683 | 5310 | 310 | 16.2 | 2009 | 474 | 18.5 | 1.34 (0.25 to 2.43) |

| Uruguay | 3391 | 14 740 | 693 | 25.3 | 2004 | 659 | 22.0 | ND |

| Caribbean | ||||||||

| “Latin” Caribbean | ||||||||

| Cuba | 11 249 | NA | 1118 | 14.3 | 2009 | 1415 | 15.4 | 1.16 (0.44 to 1.89) |

| Dominican Republic | 10 183 | 9490 | 426 | 13.1 | 2004 | 503 | 13.4 | ND |

| Puerto Rico | 3743 | 16 560 | 341 | 12.3 | 2007 | 416 | 12.3 | −0.56 (−2.09 to 0.99) |

| “English” Caribbean | ||||||||

| Antigua and Barbuda | 89 | 15 670 | 12 | 28.9 | 2009 | 10 | 21.4 | ND |

| Aruba | 108 | NA | 7 | 11.4 | 2009 | 13 | 15.5 | ND |

| Bahamas | 351 | 29 850 | 28 | 20.5 | 2008 | 44 | 22.8 | ND |

| Bermuda | – | – | 13 | 19.7 | 2008 | 9 | 12.9 | ND |

| Dominica | 73 | 12 460 | 6 | 20.6 | 2009 | 8 | 16.5 | ND |

| Grenada | 109 | 10 530 | 4 | 7.3 | 2009 | 11 | 16.1 | ND |

| Guyana | 758 | 3460 | 78 | 25.9 | 2006 | 35 | 9.8 | ND |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | 51 | 14 490 | 8 | 30.0 | 2008 | 6 | 22.2 | ND |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | 104 | 10 560 | 7 | 14.5 | 2008 | 16 | 28.6 | ND |

| Suriname | 534 | NA | 19 | 8.6 | 2007 | 24 | 10.0 | −1.76 (−7.71 to 4.57) |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 1351 | 24 940 | 127 | 19.2 | 2007 | 163 | 21.6 | 4.57 (1.80 to 7.42) |

| United States Virgin Islands | 105 | NA | 17 | 23.1 | 2007 | 10 | 11.4 | ND |

APC, annual percentage change; ASMR, age-standardized mortality rate; CI, confidence interval; GNI, gross national income; NA, not available; ND, not determined; US$, United States dollar.

a Data for the year 2012, from the records of the Pan American Health Organization.15

b Deaths per 100 000 females.

c Latest year for which relevant data on mortality from breast cancer were available.

d In ASMR between 2000 and the latest year for which data were available.

Table 2. Mortality from cervical cancer in the Region of the Americas, 2000–2009.

| Country or territory | Mortality from cervical cancer |

APCc (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths in 2000 | ASMRa in 2000 | Latest yearb | Deaths in latest yearb | ASMRa in latest yearb | ||

| Northern America | ||||||

| Canada | 703 | 2.7 | 2007 | 730 | 2.4 | −2.21 (−3.31 to −1.09) |

| United States of America | 7460 | 3.3 | 2007 | 7786 | 3.1 | −1.18 (−1.52 to −0.83) |

| Mexico and Central America | ||||||

| Belize | 17 | 23.2 | 2008 | 16 | 15.5 | −7.43 (−12.89 to −1.63) |

| Costa Rica | 151 | 9.1 | 2009 | 117 | 5.1 | −6.65 (−8.44 to −4.82) |

| El Salvador | 611 | 23.6 | 2008 | 566 | 17.9 | −3.01 (−4.01 to −2.0) |

| Mexico | 4944 | 12.3 | 2009 | 4326 | 8.0 | −4.86 (−5.17 to −4.56) |

| Nicaragua | 380 | 24.1 | 2009 | 421 | 19.4 | −3.73 (−4.76 to −2.68) |

| Panama | 153 | 12.0 | 2009 | 147 | 8.5 | −5.43 (−7.01 to −3.83) |

| South America | ||||||

| Andean Area | ||||||

| Colombia | 2416 | 14.7 | 2008 | 2609 | 12.0 | −3.05 (−3.54 to −2.56) |

| Ecuador | 694 | 13.9 | 2009 | 885 | 13.3 | −0.86 (−1.63 to −0.08) |

| Peru | 2117 | 20.9 | 2007 | 2031 | 16.3 | −1.15 (−1.85 to −0.44) |

| Venezuela | 1548 | 15.9 | 2007 | 1856 | 14.9 | −1.31 (−2.02 to −0.06) |

| Brazil | 7965 | 10.1 | 2009 | 8920 | 8.4 | −2.2 (−2.43 to −1.97) |

| Southern Cone | ||||||

| Argentina | 1861 | 8.4 | 2009 | 1955 | 7.6 | −0.99 (−1.48 to −0.49) |

| Chile | 771 | 8.9 | 2008 | 685 | 6.1 | −4.02 (−4.91 to −3.12) |

| Paraguay | 549 | 28.6 | 2009 | 537 | 20.5 | −3.49 (−4.35 to −2.63) |

| Caribbean | ||||||

| Cuba | 531 | 7.2 | 2009 | 593 | 7.0 | −0.16 (−1.18 to 0.87) |

| Guyana | 72 | 22.8 | 2006 | 44 | 12.7 | −4.88 (−9.77 to 0.27) |

| Puerto Rico | 94 | 3.5 | 2007 | 106 | 3.4 | −1.79 (−4.65 to 1.16) |

| Suriname | 26 | 12.6 | 2007 | 21 | 8.3 | −4.77 (−10.37 to 1.17) |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 89 | 13.6 | 2007 | 95 | 12.9 | −1.59 (−4.80 to 1.73) |

APC, annual percentage change; ASMR, age-standardized mortality rate; CI, confidence interval.

a Deaths per 100 000 females.

b Latest year for which relevant data on mortality from cervical cancer were available.

c In ASMR between 2000 and the latest year for which data were available.

Within the Americas, mortality from female breast cancer is relatively high in the countries of the Southern Cone and the “English” Caribbean. According to the most recent data, the age-standardized annual rate of death from breast cancer is 22.8 deaths per 100 000 females in the Bahamas, 21.6 deaths per 100 000 females in Trinidad and Tobago and 22.0 deaths per 100 000 females in Uruguay (Table 1). The lowest rates of death from female breast cancer in recent years were observed in El Salvador and Guatemala, whereas Brazil, Canada and the United States showed intermediate values (Table 1).

Recent data on cervical cancer mortality (Table 2) show relatively high annual rates in El Salvador, Nicaragua and Paraguay – with 17.9, 19.4 and 20.5 deaths per 100 000 females, respectively – and relatively low rates in Canada, Puerto Rico and the United States – with 2.4, 3.4 and 3.1 deaths per 100 000 females, respectively.

In some countries the rate of death from female breast cancer is substantially greater than that from cervical cancer. One example is Brazil, which in 2009 recorded rates of 14.9 and 8.4 deaths per 100 000 females, breast and cervical cancer, respectively. In other countries the two types of cancer cause similar mortality. This applies to Mexico, which in 2009 recorded 9.0 deaths from breast cancer and 8.0 deaths from cervical cancer per 100 000 females. And there are still other countries where the rate of death from female breast cancer is much lower than that from cervical cancer. In Nicaragua in 2009, for example, the rate of death from female breast cancer was almost half as high as the rate of death from cervical cancer – 11.1 and 19.4 deaths per 100 000 females, respectively.

Two of the countries that we investigated had relatively high rates of death from both female breast cancer and cervical cancer. One was Paraguay, with 18.5 deaths from breast cancer and 20.5 deaths from cervical cancer per 100 000 females in 2009; the other was Venezuela, with corresponding rates of 15.1 and 14.9 deaths per 100 000 in 2007 for breast and cervical cancer, respectively.

Of the 19 countries included in the analysis of temporal trends in mortality from breast and cervical cancers, four showed substantial declines in breast cancer mortality since 2000, with annual percentage changes ranging from –1.21% (95% confidence interval, CI: –1.51 to –0.92) in Argentina to –2.25% (95% CI: –2.67 to –1.83) in Canada (Table 1). Another eight countries showed substantial increases in breast cancer mortality since 2000, with annual percentage changes as high as 3.52% (95% CI: 1.61 to 5.46) in El Salvador and 4.57% (95% CI: 1.80 to 7.42) in Trinidad and Tobago (Table 1).

Since 2000, mortality from cervical cancer has been decreasing in almost all of the countries included in the analysis of temporal trends, with the greatest annual percentage changes observed in Costa Rica (–6.65%; 95% CI: –8.44 to –4.82) and Panama (–5.43%; 95% CI: –7.01 to –3.83) (Table 2)

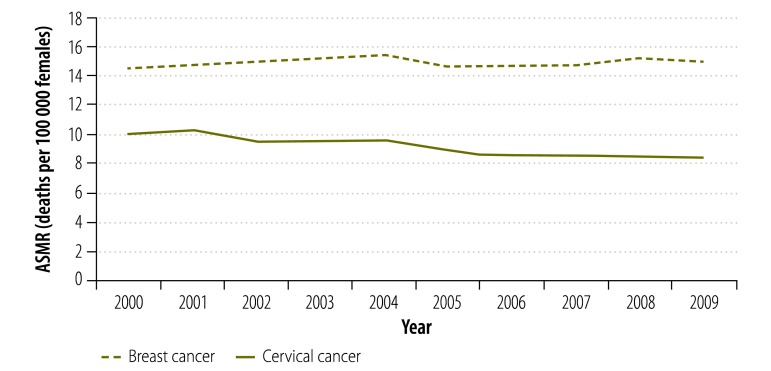

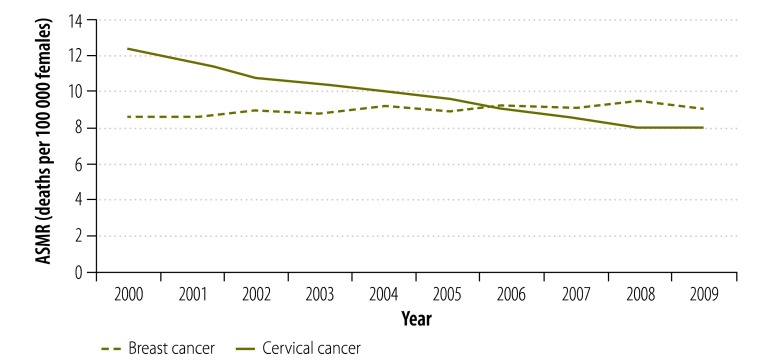

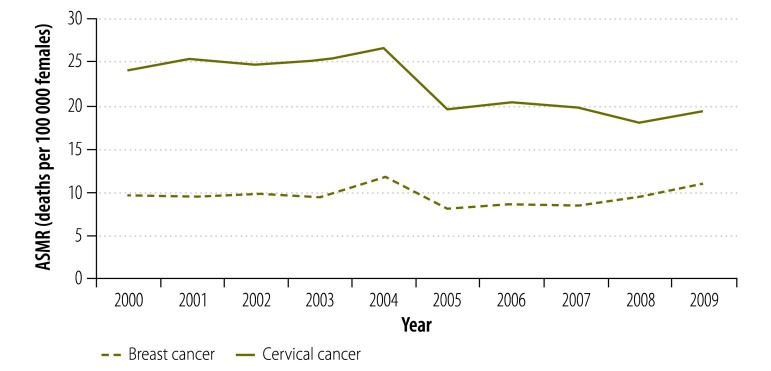

The trends for breast cancer mortality in relation to cervical cancer mortality followed three patterns: countries such as Brazil have maintained a higher rate of breast cancer mortality, whereas other countries, such as Mexico, have seen declines in cervical cancer mortality but increases in breast cancer mortality. Still others, such as Nicaragua, have maintained a higher rate of cervical cancer mortality (Fig. 1, Fig. 2 and Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Temporal trends in mortality from cervical and female breast cancers, Brazil, 2000–2009

ASMR, age-standardized mortality rate.

Fig. 2.

Temporal trends in mortality from cervical and female breast cancers, Mexico, 2000–2009

ASMR, age-standardized mortality rate.

Fig. 3.

Temporal trends in mortality from cervical and female breast cancers, Nicaragua, 2000–2009

ASMR, age-standardized mortality rate.

National policies and plans for the prevention and treatment of cancer exist in most of the countries we investigated and public health screening services for breast and cervical cancer are reported to be in place in 24 of the 25 countries that provided data for the PAHO Country Capacity Survey (Table 3). Cervical cancer screening is predominantly based on cytological testing in 24 countries, although 10 countries reported that they also offered testing for HPV DNA and 11 countries reported that they offered screening by visual inspection of the cervix after application of acetic acid. Although 24 countries reported that they offered free cytological screening for cervical cancer, only eight reported having free mammography-based screening services for breast cancer.

Table 3. Capacity to screen for, prevent and treat breast and cervical cancers in Latin America and the Caribbean, 2012.

| Parameter | South Americaa | Mexico and Central Americab | “Latin” Caribbeanc | “English” Caribbeand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer policy | ||||

| Cancer policy | All countries except Paraguay | Costa Rica and Guatemala | All countries | Barbados, Dominica, Jamaica, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago |

| Action plan for cancer | All countries except Ecuador | All countries except Belize | All countries | All countries and territories except Antigua and Barbuda, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines |

| Cervical cancer screening | ||||

| Cytology | ||||

| Available | All countries | All countries | All countries | All countries and territories |

| Free | All countries except Bolivia and Peru | All countries | Cuba and Dominican Republic | All countries and territories except Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and Suriname |

| HPV DNA test | Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Uruguay and Venezuela | Mexico | None | Bahamas |

| Visual inspection of cervix with acetic acid | Bolivia, Colombia, Paraguay and Peru | El Salvador, Guatemala and Nicaragua | Cuba and Puerto Rica | Guyana and Suriname |

| Breast cancer screening | ||||

| Clinical breast examination | All countries except Bolivia | All countries | All countries | All countries and territories |

| Mammography | ||||

| Available | All countries except Bolivia | All countries except Guatemala | Cuba and Puerto Rico | All countries and territories except Grenada |

| Free | All countries that have it available except Argentina, Paraguay and Peru | Costa Rica, Mexico and Nicaragua | Cuba | Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica, Saint Lucia and Trinidad and Tobago |

| Cancer treatment | ||||

| Chemotherapye | ||||

| Available | All countries | All countries except Belize | All countries | All countries and territories except Saint Kitts and Nevis |

| Free | All countries except Bolivia | Costa Rica, Mexico and Nicaragua | Cuba | Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago |

| Radiation therapy | ||||

| Available | All countries | All countries except Belize | All countries | Bahamas, Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago |

| Free | All countries except Bolivia and Peru | Costa Rica, Mexico and Nicaragua | Cuba | Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago |

| Tamoxifen | ||||

| Available | All countries except Paraguay | All countries except El Salvador and Guatemala | All countries | All countries and territories except Saint Kitts and Nevis and Grenada |

| Free | Brazil, Chile, Ecuador and Venezuela | Costa Rica and Nicaragua | Cuba | Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Dominica, Guyana, Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago |

| Oral morphine | ||||

| Available | All countries except Paraguay | Belize, Costa Rica and Panama | Cuba and Puerto Rico | All countries and territories except Guyana and Saint Kitts and Nevis |

| Free | Brazil, Chile and Venezuela | Belize and, Costa Rica | Cuba | Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago |

DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; HPV, human papillomavirus.

a Information available for Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela.

b Information available for Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua and Panama.

c Information available for Cuba, Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico.

d Information available for Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago.

e Chemotherapy refers to the list of cytotoxic medicines contained in the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (17th list, March 2011), accessible at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2011/a95053_eng.pdf

For cancer treatment, almost all of the 25 countries that provided data for the PAHO Country Capacity Survey reported the availability of chemotherapy, but eight countries, mainly in the Caribbean, reported that they had no radiotherapy available. In many countries, patients have to contribute financially to the costs of chemotherapy and – where available – radiotherapy. Although most of the countries reported having tamoxifen widely available, patients – even the poorest – were also charged for this drug. Most of the countries included in the survey reported having oral morphine available for palliative care. However, such medication was reportedly unavailable in seven of the countries, most of them in Central America.

Discussion

This brief descriptive analysis calls attention to the significant problem of breast and cervical cancers in all countries and territories of the Region of the Americas, and to the capacity that is available for the early detection and treatment of such cancers in the Region. It highlights the inequities represented by cervical cancer, which disproportionately affects women in the poorer countries, especially those with gross national incomes of less than 10 000 United States dollars per capita (Table 1 and Table 2). It also highlights the growing burden from breast cancer in several countries in Latin America and the Caribbean and the “double burden” of high mortality from both breast and cervical cancer faced by some of these countries.

Most of deaths from cervical cancer reported throughout the Americas were registered in Latin America or the Caribbean. This north–south divide can be seen in Appendix A (available at: http://www.paho.org/cancer/Appendix-A). The numbers of deaths from breast cancer in North America were, however, similar to the combined numbers for Latin America and the Caribbean (Appendix A). Within the countries and territories of Latin America and the Caribbean, the highest mortality rates from female breast cancer – seen in the countries of the Southern Cone – have been up to five times higher than the corresponding lowest rates – seen in Central America. Conversely, the highest rates of mortality from cervical cancer have been seen in Central America and have been up to three times higher than those recorded in the Southern Cone. These differences may be attributable to the level of socioeconomic development in each country and/or to geographical differences in access to screening, early diagnosis and treatment services.16–19

This review validates several recent reports on mortality from breast and cervical cancers in the Americas.5,16–25 In general, it has revealed temporal trends similar to those reported worldwide.4 However, several countries in the Americas have achieved important reductions in mortality from breast or cervical cancers over the last decade: Canada and the United States have achieved such reductions for breast cancer, whereas Chile, Costa Rica and Mexico have observed such reductions for cervical cancer. The relatively low annual numbers of deaths from both breast cancer and cervical cancer reported by the countries and territories of the Caribbean are potentially misleading, since they are reflections of small national populations and not of low mortality rates. The lack of radiotherapy in several of the small island nations of the Caribbean is a problem that needs to be resolved.

Progress in the development and implementation of policies, programmes and interventions against breast and cervical cancers have been seen in the Region of the Americas for several years.26–28 Since all the countries in the Region now have screening programmes for cervical cancer,25 several Latin American countries are now offering testing for HPV DNA in their national cervical cancer programmes26 and several report capacity for mammography screening.29 Effective screening for cervical cancer may partly explain recent declines in rates of mortality from such cancer. The continuing rise in mortality from breast cancer in several countries and territories of Latin America and the Caribbean is discouraging and probably a reflection of poor general access to health care and to a severe shortage of the resources needed to screen for such cancer.

According to some reports, in several countries in the Americas that have the capacity for screening and early detection, the main focus is still on treatment, with late-stage diagnosis and poor outcomes commonly observed.18 Such a focus can lead to low coverages in screening for both cervical cancer26 and breast cancer. In some countries mammography is limited to highly educated women or is unavailable to women who lack health insurance.30

The present analysis was based on deaths registered by national authorities and reported to PAHO, with corrections to account for any under-registration of mortality. Our mortality data differ from those presented in GLOBOCAN 2008,3 as they remain largely unchanged by estimation and prediction. There are, however, some limitations in using the mortality data reported to PAHO. First, PAHO has no mortality data from Bolivia, Haiti, Honduras or Jamaica, so these countries could not be included in this regional analysis. Second, PAHO only had incomplete mortality data for Anguilla, the British Virgin Islands, the Cayman Islands, Dominica, the Dominican Republic, French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Martinique, the former Netherlands Antilles, Saint Lucia, Turks and Caicos and Uruguay – although the data that were available for the Dominican Republic, Guatemala and Uruguay were sufficient for these three countries to be included in our analysis. As no subnational data for most countries in the Americas were available in the PAHO mortality database, no within-country comparisons of mortality rates were made. There is a general need to strengthen the vital statistics systems in most countries of Latin America and the Caribbean – to permit improvements in the quality, completeness and timeliness of the data collected on mortality – and to create or strengthen population-based cancer registries.

To enable comparisons between countries and take into consideration the substantial number of deaths recorded as being from “malignant neoplasm of uterus, parts unspecified” (i.e. ICD-10 code C55) we reassigned deaths attributed to C55 to a more specific cause of either cancer of the cervix or cancer of the uterus. This reassignment was possible for most of the countries included in our analyses; the exceptions were Caribbean countries and territories that reported small numbers of deaths from cervical cancer. As countries in the Region of the Americas do not apply a reallocation algorithm in reporting their national mortalities from cervical cancer, the data presented in this paper may vary from those presented in national reports by ministries of health. By applying the reallocation procedure, we tried to accommodate the underestimation of deaths from cervical cancer, adjust for any temporal improvements in data coding over the study period and improve the validity of any between-country comparisons. There were, however, limitations in using the procedure, particularly because there is no ideal reference population.

Low- and middle-income countries in the Americas are clearly making efforts – via screening and treatment programmes – to address the problems posed by breast and cervical cancers. In addition, by 2012 nine countries in the Region of the Americas – Argentina, Canada, Guyana, Mexico, Panama, Peru, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, and the United States – had introduced HPV vaccination into their national immunization programmes.28 The Region’s political and technical commitment to the control and treatment of cancer in general and cervical cancer in particular is demonstrated by the endorsement, by the Regions’ ministers of health, of a Regional Strategy and Plan of Action for Cervical Cancer Prevention and Control.31 Several countries in the Region have already implemented large-scale interventions that have demonstrated the feasibility and effectiveness of comprehensive programmes against cervical cancer and breast cancer.32,33 A network of South American cancer institutes known as RINC/UNASUR (for Red de Institutos Nacionales de Cáncer/Unión de Naciones Suramericanas) collaborates to strengthen programmes against breast and cervical cancer.34

The inequities represented by morbidity and mortality from breast and cervical cancers need to be reduced, perhaps by the use of existing health platforms, such as maternal and reproductive health programmes, to combat these women’s cancers.35,36 Although most countries in the Americas have some public health capacity for the control of breast and cervical cancers, the burden posed by these cancers could be reduced further by strengthening such capacity.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Resolution CSP28.R13. Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable diseases. In: 28th Pan American Sanitary Conference, Washington, 17–21 September 2012: resolutions. Washington: PAHO; 2013. Available from: http://new.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=7022&Itemid=39541&lang=en [accessed 19 June 2013].

- 2.Health in the Americas: regional overview and country profiles Washington: Pan American Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. GLOBOCAN 2008 v 2.0, cancer incidence and mortality worldwide Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forouzanfar MH, Foreman KJ, Delossantos AM, Lozano R, Lopez AD, Murray CJL, et al. Breast and cervical cancer in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2011;378:1461–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61351-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The challenge ahead: progress and setbacks in breast and cervical cancer: regional overviews Seattle: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Comprehensive cervical cancer control: a guide to essential practice Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization Human papillomavirus vaccines. WHO position paper. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2009;84:118–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitchener HC, Castle PE, Cox JT. Achievements and limitations of cervical cytology screening. Vaccine. 2006;24(Suppl 3):63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson BO, Yip CH, Smith RA, Shyyan R, Sener SF, Eniu A, et al. Guideline implementation for breast healthcare in low-income and middle-income countries: overview of the Breast Health Global Initiative Global Summit 2007. Cancer. 2008;113(Suppl):2221–43. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gøtzsche PC, Nielsen M. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(1):CD001877. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001877.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan American Health Organization [Internet]. Regional Health Observatory, regional mortality database. Washington: Pan American Health Organization; 2011. Available from: http://new.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=4456&Itemid=2392 [accessed 19 June 2013].

- 12.Pan American Health Organization On the estimation of mortality rates for countries of the Americas. Epidemiol Bull. 2003;24:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loos AH, Bray F, McCarron P, Weiderpass E, Hakama M, Parkin DM. Sheep and goats: separating cervix and corpus uteri from imprecisely coded uterine cancer deaths, for studies of geographical and temporal variations in mortality. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:2794–803. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World population prospects: the 2010 revision New York: United Nations; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Basic health indicators. Washington: Pan American Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bray F, Jemal A, Grey N, Ferlay J, Forman D. Global cancer transitions according to the Human Development Index (2008–2030): a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:790–801. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lozano-Ascencio R, Gómez-Dantés H, Lewis S, Torres-Sánchez L, López-Carrillo L. Tendencias del cáncer de mama en América Latina y el Caribe. Salud Publica Mex. 2009;51(Suppl 2):s147–56. doi: 10.1590/S0036-36342009000800004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Justo N, Wilking N, Jönsson B, Luciani S, Cazap E. A review of breast cancer care and outcomes in Latin America. Oncologist. 2013;18:248–56. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robles SC, Galanis E. Breast cancer in Latin America and the Caribbean. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2002;11:178–85. doi: 10.1590/S1020-49892002000300007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson BO, Cazap E. Breast Health Global Initiative (BHGI) outline for program development in Latin America. Salud Publica Mex. 2009;51(Suppl 2):s309–15. doi: 10.1590/S0036-36342009000800022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee BL, Liedke PER, Barrios CH, Simon SD, Finkelstein DM, Goss PE. Breast cancer in Brazil: present status and future goals. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e95–102. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70323-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freitas-Junior R, Gonzaga CM, Freitas NM, Martins E, Dardes RdeC. Disparities in female breast cancer mortality rates in Brazil between 1980 and 2009. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2012;67:731–7. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2012(07)05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pedraza AM, Pollán M, Pastor-Barriuso R, Cabanes A. Disparities in breast cancer mortality trends in a middle income country. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134:1199–207. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arbyn M, Castellsagué X, de Sanjosé S, Bruni L, Saraiya M, Bray F, et al. Worldwide burden of cervical cancer in 2008. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:2675–86. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arrossi S, Sankaranarayanan R, Parkin DM. Incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in Latin America. Salud Publica Mex. 2003;45(Suppl 3):S306–14. doi: 10.1590/S0036-36342003000900004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cervical cancer prevention and control programs: a rapid assessment in 12 countries of Latin America Washington: Pan American Health Organization; 2010. Available from: http://new.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=3595&Itemid=3637&lang=en [accessed 19 June 2013].

- 27.Luciani S. Cervical cancer burden and screening programs in Latin America and the Caribbean Madrid: Fundación para el Progreso de la Educación y la Salud; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munoz N. Progress in HPV vaccine introduction in Latin America. Madrid: Fundación para el Progreso de la Educación y la Salud; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cazap E, Buzaid AC, Garbino C, de la Garza J, Orlandi FJ, Schwartsmann G, et al. Latin American and Caribbean Society of Medical Oncology Breast cancer in Latin America: results of the Latin American and Caribbean Society of Medical Oncology/Breast Cancer Research Foundation expert survey. Cancer. 2008;113(Suppl):2359–65. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reyes-Ortiz CA, Freeman JL, Peláez M, Markides KS, Goodwin JS. Mammography use among older women of seven Latin American and Caribbean cities. Prev Med. 2006;42:375–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luciani S, Andrus JK. A Pan American Health Organization strategy for cervical cancer prevention and control in Latin America and the Caribbean. Reprod Health Matters. 2008;16:59–66. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(08)32405-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.González-Robledo LM, González-Robledo MC, Nigenda G, López-Carrillo L.Acciones gubernamentales para la detección temprana del cáncer de mama en América Latina: retos a futuro. Salud Publica Mex 201052533–43.Spanish 10.1590/S0036-36342010000600009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Almonte M, Murillo R, Sánchez GI, Jerónimo J, Salmerón J, Ferreccio C, et al. Nuevos paradigmas y desafíos en la prevención y control del cáncer de cuello uterino en América Latina. Salud Publica Mex 201052544–59.Spanish 10.1590/S0036-36342010000600010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Consejo de Salud Suramericano. Resolución 04/2011: Red de Institutos Nacionales de Cáncer de UNASUR (RINC/UNASUR) [Resolution 04/2011: Network of National Cancer Institutes of UNASUR (RINC/UNASUR)]. Rio de Janeiro: Unión de Naciones Suramericanas; 2011. Spanish. Available from: http://www2.rinc-unasur.org/wps/wcm/connect/RINC/site/home [accessed 19 June 2013].

- 35.Knaul FM, Bustreo F, Ha E, Langer A. Breast cancer: why link early detection to reproductive health interventions in developing countries? Salud Publica Mex. 2009;51(Suppl 2):s220–7. doi: 10.1590/S0036-36342009000800012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knaul FM, Bhadelia A, Gralow J, Arreola-Ornelas H, Langer A, Frenk J. Meeting the emerging challenge of breast and cervical cancer in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;119(Suppl 1):S85–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]