Abstract

The pharmaceutical world has greatly benefited from the well-characterized structure-function relationships of toxins with endogenous biomolecules, such as ion-channels, receptors, and signaling molecules. Thus, therapeutics derived from toxins have been aggressively pursued. However, the multifunctional role of various toxins may lead to undesirable off-target effects, hindering their use as therapeutic agents. In this paper, we suggest that previously unsuccessful toxins (due to off-target effects) may be revisited with mixtures by utilizing the pharmacodynamic response to the potential primary therapeutic as a starting point for finding new targets to ameliorate the unintended responses. In this proof of principle study, the pharmacodynamic response of HepG2 cells to a potential primary therapeutic (deguelin, a plant-derived chemopreventive agent) was monitored, and a possible secondary target (p38MAPK) was identified. As a single agent, deguelin decreased cellular viability at higher doses (> 10 μM), but inhibited oxygen consumption over a wide dosing range (1.0 – 100 μM). Our results demonstrate that inhibition of oxygen consumption is related to an increase in p38MAPK phosphorylation, and may only be an undesired side effect of deguelin (i.e., one that does not contribute to the decrease in HepG2 viability). We further show that deguelin’s negative effect on oxygen consumption can be diminished while maintaining efficacy when used as a therapeutic mixture with the judiciously selected secondary inhibitor (SB202190, p38MAPK inhibitor). These preliminary findings suggest that an endogenous response-directed mixtures approach, which uses a pharmacodynamic response to a primary therapeutic to determine a secondary target, allows previously unsuccessful toxins to be revisited as therapeutic mixtures.

Keywords: therapeutic mixtures, deguelin, pharmacodynamics, plant-derived therapeutics

1 INTRODUCTION

The well-characterized structure-function relationships of toxins, such as snake venoms and plant-derived toxins, have led to major advances in understanding normal and disease state physiology, as well as the development of pharmacological regimens based on the structures of various toxins (McCleary and Kini, 2012). One such example is captopril, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor to treat hypertension that is based on bradykinin-potentiating factor (BPF) isolated from the Brazilian pit viper Bothrops jararaca (Ferreira, 1965). Captopril has also been used in combination with marimastat (a matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor) and fragmin (a low molecular weight heparin approved by the U.S. FDA) as an antiangiogenesis therapeutic mixture for patients with advanced stage cancer (Jones et al., 2004). From the successes of captopril, among many other therapeutics derived from toxins, natural toxin-based pharmacology has been aggressively pursued (Koh and Kini, 2012).

Previously known for their success as insecticides and fishing poisons, plant-derived rotenoids, such as deguelin, have been investigated for their potential use as chemopreventive (designed to delay the onset of cancer) and chemotherapeutic (designed to destroy cancer after it appears) agents (Kim et al., 2008; Aggarwal et al., 2004). Deguelin, a natural isoflavonoid isolated from the root of Lonchocarpus utilis and Lonchocarpus urucu (Caboni et al., 2004), inhibits NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) of the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC), HSP90, and AKT (Lee et al., 2005; Oh et al., 2007, 2008; Peng et al., 2007). As a fishing poison, rotenoids are often used due to their inhibition of cellular respiration via inhibition of complex I of the ETC (Neuwinger, 2004). Inhibition of respiration in cells results in tissue asphyxia and consequently organ paralysis (Neuwinger, 2004). As a chemopreventive agent, rotenoids, specifically deguelin, have shown promise for a variety of cancer types (Chun et al., 2003; Murillo et al., 2002; Peng et al., 2007; Udeani et al., 1997). Unfortunately, when used as a chemotherapeutic, rotenoids have exhibited undesirable side effects, such as respiratory depression and cardiotoxicity, presumably due to a decrease in cellular oxygen consumption caused by inhibition of complex I (Lee, 2004). Additionally, deguelin has been shown to induce a Parkinson’s disease-like syndrome in rats when administered in high doses, which is also potentially related to activity at complex I (Caboni et al., 2004). These undesired side effects related to complex I inhibition have hindered deguelin’s use as a chemotherapeutic agent (Agarwal and Deep, 2008; Fang and Casida, 1998).

While deguelin has inherent faults that diminish its legitimacy as a chemotherapeutic agent, it may still hold promise as a potential therapeutic if combined with another xenobiotic. In recent years, using a combinatorial/mixtures approach with targeted kinase therapeutics has shown promise as an effective strategy (Engelman et al., 2007; Ma et al., 2005; Namiki et al., 2006; Stommel et al., 2007; Yasui et al., 2007) because many mechanisms for cell survival rely on intricate and sophisticated intracellular signaling networks, making single-point inhibition impractical for treatment (Fitzgerald et al, 2006; Toschi and Janne, 2008). The initial pharmacodynamic response to xenobiotic insult is primarily coordinated by signal transduction networks, which typically follow a simple framework: the phosphorylation/dephosphorylation cycle mediated by kinases and phosphatases (Kholodenko, 2006; Sauro and Kholodenko, 2004). Since a typical cellular response to exposure involves the integration of many kinases into pathways for a coordinated response, this enzyme class make advantageous targets for a mixtures approach (Cohen, 2002; Collins and Workman, 2006; Dancey and Sausville, 2003).

There are several different strategies for determining possible mixtures therapies for kinase targets (Jackson, 1993). One strategy involves the simultaneous inhibition of a single target using two or more compounds, while another strategy utilizes two inhibitors to attack two different proteins on a linear pathway (e.g. mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade) (Fitzgerald et al., 2006). A drawback to these mixtures approaches is that prior knowledge of the network and kinases of interest are required to select which inhibitors to use. This paper suggests an alternative strategy: instead of selecting mixtures based on previously known mechanisms and complex networks that may not fit the cell line or disease of interest, the endogenous response of the cell to a primary therapeutic may be used to select the secondary target of interest. By monitoring the endogenous response of the network while under duress from a primary therapeutic, the cell’s alternate mode of survival can be exposed, and a second inhibitor may be selected for a more effective mixtures therapeutic strategy. By utilizing the endogenous response to primary therapeutic, undesirable effects (such as decreased oxygen consumption following exposure to deguelin) may be targeted for amelioration. Overall, this strategy holds promise for potentially maintaining efficacy of an initial therapeutic (deguelin) while reducing side effects for improved patient outcome.

In this study, we investigated the endogenous response of HepG2 cells, a human hepatocellular carcinoma-derived cell line, to a primary therapeutic (deguelin) at varying doses to determine a potential secondary target for a beneficial therapeutic mixture. We selected the HepG2 cell line as our model in vitro system due to the central role that the liver plays in xenobiotic biotransformation after exposure (Mersch-Sundermann, et al., 2004). Most importantly, the HepG2 cell line retains endogenous xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes, whereas primary hepatocyte culture typically loses these vital enzymes (Knasmuller, et al., 1998). We monitored the response of HepG2 cells to deguelin by determining 24 hour viability and kinetically measuring oxygen consumption over 24 hours. From this data, we found a critical shift in oxygen consumption at 400 minutes post-dose that spanned several doses. At this time-point, we monitored the relative post-translational phosphorylation of 8 proteins involved in cell proliferation or apoptotic signal transduction cascades. From this phosphorylation response data, we selected p38MAPK as a secondary target, and used a specific p38MAPK inhibitor (SB202190) in combination with deguelin to possibly alter the overall cellular response to deguelin. We found that by using an endogenously selected therapeutic mixture, deguelin’s inhibition of oxygen consumption was diminished while maintaining efficacy. This proof of principle study shows that by using an endogenous response-directed mixtures approach, previously unsuccessful toxins as a primary therapeutic may be revisited.

2 MATERIALS & METHODS

2.1 Materials

Deguelin (CAS no. 522-17-8) and SB202190 (CAS no. 152121-30-7) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). RPMI-1640 containing phenol red, RPMI-1640 without phenol red, sodium pyruvate, HEPES, L-glutamine, fetal bovine serum, and penicillin-streptomycin were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Cell lines and MTT assay kits were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). MitoXpress oxygen probe was obtained from Luxcel Corporation (Cork, Ireland). BioPlex beads, lysis buffer, and reagents necessary for determination of relative phosphorylation were obtained from BioRad (Hercules, CA)

2.2 Cell culture

Human hepatocellular carcinoma-derived HepG2 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640, supplemented with 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 5 mM HEPES, 2 mM L-Glutamine, 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C, 5% CO2 and passaged at 80 % confluence.

2.3 Dosing

Cells were seeded into clear-bottom, black-sided 96-well plates at a concentration of 4 × 104 cells per well in RPMI-1640 without phenol red and allowed to grow for 24 hours before dosing. Media was then aspirated from wells and cells were challenged with varying doses of single and mixed compounds in fresh media. Compounds were prepared so that resulting well concentrations would be <1% DMSO and 0.01 μM to 100 μM (deguelin) and 350 nM (SB202190).

2.4 MTT assay

After 24 hours of exposure to single compounds or mixtures, cell viability was determined using the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethyl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) assay, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The assay is based on the reduction of tetrazolium MTT to formazan by metabolically active cells, in part by the action of dehydrogenase enzymes, to generate reducing equivalents such as NADH and NADPH. Briefly, MTT reagent was added to the wells of the microplate, and after two hours of incubation at 37°C, intracellular formazan crystals were solubilized with the provided detergent solution. Absorbance values were obtained using the Safire2 microplate reader (Tecan US, Raleigh, NC) with a measurement wavelength of 570 nm and a reference wavelength of 700 nm, read from the bottom. Experiments were each performed at least in triplicate. Percent viability was calculated by normalizing to controls, which received dosing vehicle (1% DMSO).

2.5 Oxygen consumption assay

Immediately after dosing with single compounds or mixtures, cellular oxygen consumption was assessed using the MitoXpress probe, according to manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, oxygen-sensitive probe was diluted to a stock concentration of 1 μM, and stock probe was diluted 1:15 in each well of a 96-well plate containing cells; 100 μL of pre-warmed mineral oil was also added to each well to block ambient oxygen from the cells. After pre-warming the plates at 37°C for 1 hour, cells were challenged with varying doses of deguelin alone or in combination the IC50 of SB202190 (350nM). Immediately following addition of compound(s), oxygen consumption was determined by measuring fluorescence. Fluorescent signal was obtained using the Infinite M1000 microplate reader (Tecan US, Raleigh NC) with excitation wavelength of 380 nm and emission wavelength of 650 nm, reading from the bottom every 10 minutes for 24 hours after dosing. Experiments were performed in quadruplicate. Relative oxygen consumption was calculated by normalizing to controls, which received dosing vehicle (1% DMSO).

2.6 Bio-Plex Multiplex Immunoassay

After 400 minutes of exposure (Boyd et al., 2012) to increasing doses of deguelin (0.01, 0.1, 1.0, 10, 100 μM) in 1% DMSO alone, or in combination with IC50 of SB202190 (350nM), cells were lysed using lysis buffer (BioRad, Hercules, CA) with 500μM phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride (PMSF) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and phosphatase inhibitors (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Total protein concentration was determined using the DC Protein Assay (BioRad, Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein phosphorylation was detected using multiplex assays analyzed with the flow based BioPlex suspension array system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and lysates were prepared according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Beads and detection antibodies against phosphorylated ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204, Thr185/Tyr187), AKT (Ser473), HSP27 (Ser78), IκBα (Ser32/Ser36), JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), p38MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182), p53 (Ser15), and p90RSK (Thr359/Ser363) were obtained from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). Relative phosphorylation was calculated by normalizing to control cells, which received dosing vehicle (1% DMSO). All experiments were performed in duplicate.

2.7 Statistical Analysis

Dose-response curves for MTT assays were generated by best-fit Hill-plot regression of scatter plot data using Prism V5 (Graphpad Software, San Diego, CA). Oxygen consumption curves were generated by choosing the best-fit polynomial regression of scatter plot data using Prism V5 (Graphpad Software, San Diego, CA). The time point of interest (400 min) was selected using SAS JMP V8 (Cary, NC) where the change in the slope of the oxygen consumption curve reached a minimum for most exposures. Statistical significance for viability and relative phosphorylation was assessed by using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post-test. Statistical significance for oxygen consumption (a kinetic assay) was assessed by using a Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test with Dunns post-test. A difference at P < 0.05 level was considered statistically significant. For viability and relative phosphorylation data, error bars reflect standard error of the mean. For oxygen consumption curves (best-fit polynomial regression), error was reported at the 95% confidence interval.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Deguelin as a monotherapy

To determine the overall effect of deguelin alone, HepG2 cells were exposed to log doses of deguelin (0.01 – 100 μM) and viability at 24 hours post-dose was measured using the MTT assay (shown in Figure 1). Our viability data suggests that deguelin is effective at doses greater than 10μM (EC50 = 45 ± 1 μM).

Figure 1. Percent viability of HepG2 cells in response to 24 hour exposure of 0.01 – 100 μM deguelin.

Viability, shown as % viability, was measured as in Methods and was calculated relative to control cells which received dosing vehicle (<1% DMSO) only. Dose-response curve was generated by a best-fit Hill-plot regression of scatter plot data. Error is reported as ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

3.2 HepG2 viability (in response to deguelin) may not be directly associated with O2 consumption

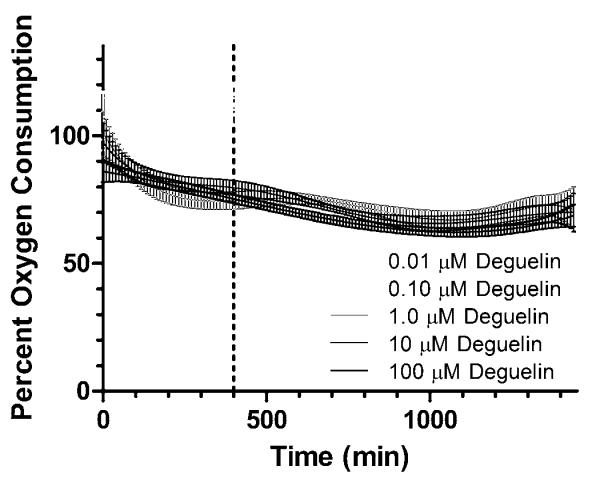

To better relate deguelin’s inhibition of oxygen consumption to endpoint viability, we kinetically measured the oxygen consumption of HepG2 cells in response to deguelin over 24 hours post-dose, as shown in Figure 2, using the MitoXpress oxygen consumption assay. From Figure 2, oxygen consumption decreased when in the presence of 1.0 – 100 μM doses of deguelin (as compared to controls, represented as percent oxygen consumption). A Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test with Dunns post-test was used to compare oxygen consumption responses to various doses. The oxygen consumption responses at all doses were statistically different (P < 0.05) from each other except for 1.0 μM vs 10 μM and 10 μM vs 100 μM. Most importantly, there is a clear separation in oxygen consumption responses between two dosing groups: the lowest doses (0.01 and 0.1 μM) and the higher doses (1.0 – 100 μM). Since our oxygen consumption data at these doses does not seem to correspond with our MTT assay (which demonstrated no decrease in viability for the 1.0 and 10 μM doses), the inhibition of oxygen consumption may not be directly associated with 24 hour HepG2 viability in response to deguelin. Furthermore, for the lower doses of deguelin (0.01 and 0.1 μM), oxygen consumption actually increases relative to controls until about 400 minutes post-exposure; at this time-point, oxygen consumption decreases, ultimately returning to control levels. Therefore, 400 minutes appears to be an interesting time point post-exposure that results in the greatest disparity in oxygen consumption between high and low doses. Since the full dosing regimen of deguelin indicated 400 minutes post-dose as a key time-point where doses of deguelin lead to both decreased (1.0 – 100 μM) and increased (0.01, 0.1 μM) oxygen consumption, we investigated the post-translational phosphorylation response to identify the underlying signal transduction events that allow for both decreased oxygen consumption and survival (ie. ~100% viability) at the 1.0 and 10 μM doses. This method of selecting critical time-points of phosphorylation events from oxygen consumption data has been previously used by Boyd et al. (2012).

Figure 2. Percent oxygen consumption of HepG2 cells in response to 0.01 – 100 μM deguelin.

Oxygen consumption response of HepG2 cells to increasing doses of deguelin (shown in shades of gray) measured over 24 hours. Oxygen consumption was measured using MitoXpress extracellular assay as outlined in section 2.5. Percent oxygen consumption is shown relative to control cells which received dosing vehicle (<1% DMSO) only. Oxygen consumption curves were generated using a best-fit polynomial function with error bars reflecting the 95% confidence intervals. Vertical line at 400 minutes was selected as the time-point of greatest disparity in oxygen consumption.

3.3 Endogenous phosphorylation response to deguelin exposes a potential secondary therapeutic target

We next explored the signal transduction response, by means of post-translational phosphorylation activity, of HepG2 cells exposed to increasing doses of deguelin. We simultaneously measured the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204, Thr185/Tyr187), AKT (Ser473), HSP27 (Ser78), IκBα (Ser32/Ser36), JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), p38MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182), p53 (Ser15), and p90RSK (Thr359/Ser363) at 400 minutes post-exposure to deguelin using bead-based ELISA flow cytometry. These protein targets were selected because of their relevance in signal transduction pathways related to cellular death and recovery [Dong et al., 2002; Jin and El-Deiry, 2005; Oren, 2003; Wilkinson and Millar, 2000], and due to the availability of selective inhibitors. Figure 3 shows the relative phosphorylation response of HepG2 cells to 400 minute exposures of increasing doses of deguelin (as compared to controls, normalized to a value of 1). A two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test determined significant differences (P < 0.05) between deguelin-exposed and control cells for p38MAPK at 0.1 μM; ERK1/2, JNK, p38MAPK, IκBα, p53, and p90RSK at 1.0 μM; for all proteins except JNK at 10 μM; and for all proteins at 100 μM (Figure 3). While several proteins experienced a relative phosphorylation change in response to deguelin at 400 minutes post-dose, p38MAPK phosphorylation is statistically different across four orders of magnitude of dose (1.0 – 100 μM).

Figure 3. Relative phosphorylation of protein targets in response to 0.01 – 100 μM deguelin.

Post-translational phosphorylation response of protein targets (from cell lysates) to 400 minute exposures of deguelin as outlined in Methods; responses are shown relative to control cells, which received dosing vehicle (<1% DMSO), but no deguelin. The solid black line at y = 1 shows where observed post-translational phosphorylation responses are the same as control. The phosphorylation responses found to be significantly different (P < 0.05) from controls are marked with *.

3.4 Using mixtures to suppress endogenous p38MAPK response to deguelin

To determine if our directed mixtures approach, which takes advantage of the endogenous pharmacodynamic response to deguelin, has the potential to decrease viability while minimizing deguelin’s effect on oxygen consumption, we attempted to suppress the post-translational p38MAPK phosphorylation response to deguelin by using a secondary inhibitor, SB202190. We chose SB202190 because it is a selective inhibitor of p38MAPK (Lee et al., 1994). HepG2 cells were exposed to SB202190 alone at its manufacturer reported IC50 (350 nM) and in combination with a full range of deguelin doses (0.01 – 100 μM), and we measured the p38MAPK post-translational phosphorylation response at 400 minutes post-dose (shown in Figure 4). From this figure, SB202190 alone does decrease the phosphorylation response of p38MAPK (0.61 ± 0.02) when compared to controls, indicating that it is a relatively potent inhibitor (350 nM) of p38MAPK. A two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test determined significant differences (P < 0.05) between the p38MAPK response to deguelin alone and the mixture, as well as SB202190 alone and the mixture. Most notably the relative p38MAPK phosphorylation responses to mixtures of deguelin (0.1 – 10 μM) with SB202190 were significantly decreased in comparison to deguelin alone.

Figure 4. Relative p38MAPK phosphorylation in response to deguelin, SB202190, and mixtures of deguelin with SB202190.

The phosphorylation response of p38MAPK from cell lysates at 400 minute exposures to mixtures of deguelin and 350 nM SB202190 (black), deguelin alone (white), and 350 nM SB202190 alone (black dots with grey line representing standard error of the mean) as discussed in sections 2.6 and 3.4; all values are reported as relative to control cells, which received dosing vehicle (<1% DMSO) only. Error is reported as ± SEM. Post-translational phosphorylation responses of the mixture found to be significantly different (P < 0.05) from deguelin alone are marked with * and those different (P < 0.05) than SB202190 alone are marked with #.

3.5 Mixtures approach retains efficacy while decreasing deguelin’s effect on O2 consumption

To test this new potential therapeutic regimen, we exposed HepG2 cells to varying doses of deguelin (0.01-100 μM) in combination with SB202190 at its manufacturer reported IC50 (350 nM) and measured viability. At 24 hours post-dose, viability was measured following treatment with SB202190 alone and in combination with deguelin, and compared to viability data for deguelin alone (controls measured concurrently), as shown in Supplemental Figure 1. SB202190 alone did not significantly decrease viability at the 350 nM dose (98 ± 3 %). Viability was slightly decreased in response to mixtures of deguelin (EC50 = 33 ± 1 μM) when compared to deguelin alone (EC50 = 45 ± 1 μM).

To determine the effect of this mixtures technique on oxygen consumption, HepG2 cells were exposed to a full dosing regimen of deguelin (0.01 – 100 μM) in combination with SB202190 (350 nM). After dosing, oxygen consumption was measured kinetically over 24 hours and compared relative to controls, shown as percent oxygen consumption. From Figure 5, SB202190 alone did not affect oxygen consumption from 0 – 600 minutes post-dose. However, after 600 minutes SB202190 decreased oxygen consumption. Mixtures of deguelin (0.01 – 100 μM) with 350 nM SB202190 sustained oxygen consumption (100% oxygen consumption relative to controls) for 0.01 μM and 0.1 μM, or increased oxygen consumption (1.0 – 100 μM), whereas exposure to deguelin alone inhibited oxygen consumption at doses of 1.0 – 100 μM. A Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test with Dunns post-test was used to compare oxygen consumption responses between doses of deguelin alone and in combination with SB202190. When compared to oxygen consumption in response to deguelin alone, mixture doses were statistically different (P < 0.05) for 1.0, 10 and 100 μM. When considering viability, efficacy of the highest mixture dose was sustained, while oxygen consumption at the highest mixture dose of deguelin (100 μM) with SB202190 was significantly increased (P < 0.05) when compared to 100 μM deguelin alone. By increasing oxygen consumption using this endogenously-directed mixtures approach, we were able to successfully ameliorate an undesired alternative action of deguelin.

Figure 5. Percent oxygen consumption of HepG2 cells in response to deguelin alone, and in combination with SB202190.

Oxygen consumption response of HepG2 cells to SB202190 alone (squares), deguelin alone (triangles) and deguelin with 350 nM SB202190 (circles) measured over 24 hours. Oxygen consumption was measured using MitoXpress extracellular assay as outlined in section 2.5. Oxygen consumption is shown relative to control cells, which received dosing vehicle (<1% DMSO), but no deguelin or SB202190. Oxygen consumption curves were generated using a best-fit polynomial function (solid line) with surrounding dotted lines reflecting the 95% confidence intervals.

4 DISCUSSION

Due to the activity of various toxins at specific intracellular proteins, therapeutic agents derived from these toxins have been aggressively pursued (McCleary and Kini, 2012). One such example is cobrotoxin, a protein isolated from the venom of the Taiwan cobra Naja naja atra (Chang et al., 1997). Cobrotoxin binds to nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling molecules with high affinity, such as p50 and inhibitory κB kinases (IKKs) (Park et al., 2005). Therapeutic agents capable of suppressing NF-κB are constantly being explored due to abnormal or constitutive NF-κB activity in many cancer types (Dolcet et al., 2005). Cobrotoxin’s inhibition of NF-κB signaling molecules suppresses NF-κB activity, making cobrotoxin an advantageous chemotherapeutic agent (Son et al., 2007). From this ideology, the present proof of principle study has demonstrated that an endogenous response-directed mixtures approach may be useful for diminishing possible off-target effects while maintaining efficacy of naturally-derived potential therapeutics. Deguelin, a plant-derived chemopreventive agent, has been shown (Figure 1) to decrease HepG2 viability at high doses. Previously, deguelin has been shown to alter activity at different intracellular proteins, such as AKT and HSP90 (Lee et al., 2005; Oh et al., 2007, 2008; Peng et al., 2007), making it a valid candidate for kinase-targeted chemotherapy. However, deguelin has also been shown to affect mitochodrial bioenergetics, presumably due to its activity at complex I of the electron transport chain (Fang and Casida, 1998;Gerhauser, et al., 1997). Previously, this inhibitory activity has been shown to decrease intracellular oxygen consumption in a mouse skin model (Gerhauser, et al., 1997), which may also contribute to cellular toxicity at distal cells. Our results (Figure 2) indicate that off-target inhibition of oxygen consumption was sustained over 24 hours in response to a range of doses (1.0 – 100 μM) of deguelin when it was used as a monotherapy. While inhibition of oxygen consumption was sustained over a wide dosing range, a significant decrease in HepG2 viability occurs only at doses greater than 10 μM. This suggests that deguelin’s inhibition of oxygen consumption may not be contributing to the decrease in HepG2 viability. It is known from the Warburg Effect that cancer cells can utilize aerobic glycolysis for ATP production, whereas differentiated cells primarily produce ATP via oxidative phosphorylation that requires sufficient amounts of oxygen (Warburg, 1956). In the absence of oxygen, it is difficult for differentiated cells to produce enough ATP from anaerobic glycolysis for survival, thus many undergo apoptosis under hypoxic conditions. However, cancer cells, such as HepG2, can survive in an oxygen-deficient environment due to their reliance on aerobic glycolysis to produce ATP [for a review, see Vander Heiden et al., 2009]. Therefore, the Warburg Effect, in conjunction with our results, supports that deguelin’s activity at separate intracellular sites may be causing decreased viability, whereas inhibition of oxygen consumption is possibly an undesirable alternative activity of deguelin that limits its usefulness as a possible therapeutic (Lee et al., 2005; Oh et al., 2007, 2008).

To better understand the discrepancies in HepG2 viability and oxygen consumption in response to deguelin, we investigated the post-translational phosphorylation response of several key proteins involved in cell recovery or pro-apoptotic signaling cascades (Figure 3). We found that p38MAPK phosphorylation in response to deguelin is significantly different over several orders of magnitude (0.1 – 100 μM) of dose. For 0.1 – 10 μM doses of deguelin, the relative phosphorylation response of p38MAPK is significantly increased. With regard to HepG2 viability, the 0.1 – 10 μM dosing range is ineffective, indicating p38MAPK as a possible protein involved in an endogenous defense mechanism that improves survival against deguelin. This is further supported by the decrease in relative phosphorylation of p38MAPK in response to 100 μM dose of deguelin that coincides with decreased viability at this dose, indicating the cell may not be able to effectively respond to a high dose of deguelin. This preliminary data suggests that a directed mixtures approach utilizing p38MAPK as a secondary target, thereby capitalizing on the endogenous response to deguelin, may be advantageous. However, it should be noted that due to the limited number of proteins measured in this study, there may be activity at other proteins/cascades that could be influencing the overall pharmacodynamic response to deguelin.

While monotherapies for cancer have proven to be successful when a single target controls the cell’s fate, many carcinomas are often more complex, with intricate signaling networks governing proliferation (Toschi and Janne, 2008). This complex survival framework, capable of facilitating uncontrolled proliferation, can withstand the inhibition of a single target by switching to an alternate mode for survival. However, by utilizing the endogenous response to a single insult (primary therapeutic), a second inhibitor may be used as a mixture with the primary therapeutic for a more effective treatment. Combinatorial approaches have previously been shown to improve various cancer therapies (Engelman et al., 2007; Fitzgerald et al., 2006; Ma et al., 2005; Namiki et al., 2006; Stommel et al., 2007; Toschi and Janne, 2008; Yasui et al., 2007). To this end, we combined a selective p38MAPK inhibitor, SB202190, with deguelin to suppress the endogenous p38MAPK response to deguelin alone (Figure 4). Additionally, when used as a therapeutic mixture, efficacy of deguelin was maintained (Supplemental Figure 1). While SB202190 has been shown to be a selective p38MAPK inhibitor, we recognize that inhibitors are not perfect and may alter the activity of undesired intracellular proteins (Muniyappa and Das, 2008). Additionally, SB202190 has been shown to be toxic in a human leukemia cell line 24 hours post-exposure at higher doses (50 M) (Nemoto et al., 1998). In this study, we found that SB202190 (350 nM) alone did not significantly decrease HepG2 viability 24 hours post-exposure (Supplemental Figure 1). It should be noted that the diverse role of p38MAPK signaling, for example the conflicting results during ischemia/reperfusion injury (for review, see Steenbergen, 2002), after cellular stress or xenobiotic exposure can vary based on the model system used (Cuadrado and Nebreda. 2010).

By using this directed mixtures approach, the undesired alternative action of deguelin (inhibition of oxygen consumption) can be ameliorated without sacrificing efficacy. From Figure 5, SB202190 treatment alone decreased oxygen consumption slightly, but treatment with the various mixtures led to an increase in oxygen consumption when compared to deguelin alone, thus minimizing deguelin’s undesired effect on oxygen consumption. Most notably, the highest mixture dose showed an increase in oxygen consumption when compared to 100 μM of deguelin alone, while maintaining efficacy (less than 15% viability). These results are consistent with previous studies that monitored mitochondrial bioenergetics in response to ETC inhibitors (Arvier et al., 2007; Dumas et al., 2003; Roussel et al., 2003). Desquiret and coworkers (2008) found that dexamethasone, a synthetic glucocorticoid, inhibits mitochondrial activity (specifically complex I and II) in HepG2 cells. Since glucocorticoid stimulation activates G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), they hypothesized that GPCR mediated kinase pathways may be key players in regulating rapid glucocorticoid activity at ETC complexes. From this, they co-exposed HepG2 cells to dexamethasone and SB202190 (since p38MAPK is downstream of GPCR), and found that SB202190 increased Complex I activity by 80%, when compared to HepG2 cells exposed to dexamethasone alone, which demonstrates the vital role p38MAPK plays in mediating mitochondrial bioenergetics after xenobiotic exposure. By using our proposed mixtures approach, the undesired alternative action of deguelin (inhibition of oxygen consumption) was diminished by inhibiting p38MAPK.

As a proof of principle, the novel mixtures approach presented here exploits the endogenous intracellular response to a primary therapeutic, revealing a secondary target for a combinatorial therapeutic regimen. By using this endogenously selected mixture, the cell’s native response mechanism against a primary therapeutic is inhibited, making the intracellular signaling network less effective at cell recovery and decreasing viability. From this directed mixtures approach, a primary therapeutic’s efficacy can be maintained, while potentially decreasing undesired side effects. Additionally, by using this approach, previously unsuccessful therapeutics derived from toxins can be revisited. This ultimately speaks to the significance of pharmacodynamic mixtures that target kinase responses as an avenue of future research.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Highlights for the manuscript: “Amelioration of an Undesired Action of Deguelin” By Julie A. Vrana, Nathan Boggs, Holly N. Williams, and Jonathan Boyd

Decreased oxygen consumption is a negative side effect of deguelin

Endogenous phosphorylation responses to deguelin implicated p38MAPK as a secondary target

Therapeutic mixture: deguelin and a p38MAPK inhibitor (SB202190)

Mixture diminished deguelin’s inhibition of oxygen consumption and maintained efficacy

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, NIH IDeA Networks of Biomedical Research Excellence (INBRE), the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, and West Virginia University whose funding supported portions of this research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None

REFERENCES

- Agarwal R, Deep G. Kava, a tonic for relieving the irrational development of natural preventive agents. Cancer Prev. Res. 2008;6:409–412. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal BB, Takada Y, Oommen OV. From chemoprevention to chemotherapy: common targets and common goals. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2004;13:1327–1338. doi: 10.1517/13543784.13.10.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvier M, Lagoutte L, Johnson G, Dumas JF, Sion B, Grizard G, Malthièry Y, Simard G, Ritz P. Adenine nucleotide translocator promotes oxidative phosphorylation and mild uncoupling in mitochondria after dexamethasone treatment. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;293:E1320–E1324. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00138.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd J, Vrana JA, Williams HN. In Vitro Approach to Predict Post-Translational Phosphorylation Response to Mixtures. Toxicology. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2012.10.010. in press. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caboni P, Sherer TB, Zhang N. Rotenone, deguelin, their metabolites and the rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2004;17:1540–1548. doi: 10.1021/tx049867r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang LS, Chou YC, Lin SR, Wu BN, Lin J, Hong E, Sun YJ, Hsiao CD. A novel neurotoxin, cobrotoxin b, from Naja naja atra (Taiwan cobra) venom: purification, characterization, and gene organization. J. Biochem. 1997;122:1252–1259. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun KH, Kosmeder JW, II, Sun S, Pezzuto JM, Lotan R, Hong WK, Lee HY. Effects of deguelin on the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway and apoptosis in premalignant human bronchial epithelial cells. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2003;95:291–302. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P. Protein kinases-the major drug targets of the twenty-first century? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2002;1:309–315. doi: 10.1038/nrd773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins I, Workman P. New approaches to molecular cancer therapeutics. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:689–700. doi: 10.1038/nchembio840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado A, Nebreda AR. Mechanisms and functions of p38 MAPK signalling. Biochem. J. 2010;429:403–417. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dancey J, Sausville EA. Issues and progress with protein kinase inhibitors for cancer treatment. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003;2:296–313. doi: 10.1038/nrd1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desquiret V, Gueguen N, Malthièry Y, Ritz P, Simard G. Mitochondrial effects of dexamethasone imply both membrane and cytosolic-initiated pathways in HepG2 cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2008;40:1629–1641. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolcet X, Llobet D, Pallares J, Matias-Guiu X. NF-kB in development and progression of human cancer. Virchows Arch. 2005;446:475–482. doi: 10.1007/s00428-005-1264-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong C, Davis RJ, Flavell RA. MAP Kinases in the immune response. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2002;20:55–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.091301.131133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas JF, Simard G, Roussel D, Douay O, Foussard F, Malthiery Y, Ritz P. Mitochondrial energy metabolism in a model of undernutrition induced by dexamethasone. Br. J. Nutr. 2003;90:969–977. doi: 10.1079/bjn2003980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, Song Y, Hyland C, Park JO, Lindeman N, Gale C-M, Zhao X, Christensen J, Kosaka T, Holmes A, Rogers AM, Capuzzo F, Mok T, Lee C, Johnson BE, Cantley LC, Janne PA. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316:1039–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang N, Casida JE. Anticancer action of cubé insecticide: Correlation for rotenoid constituents between inhibition of NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase and induced ornithine decarboxylase activities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:3380–3384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira SH. A bradykinin-potentiating factor (bpf) present in the venom of bothrops jararaca. Br. J. Pharmacol. Chemother. 1965;24:163–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1965.tb02091.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald JB, Schoeberl B, Nielsen UB, Sorger PK. Systems biology and combination therapy in the quest for clinical efficacy. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:458–466. doi: 10.1038/nchembio817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhauser C, Lee SK, Kosmeder JW, Moriarty RM, Hamel E, Mehta RG, Moon RC, Pezzuto JM. Regulation of ornithine decarboxylase induction by deguelin, a natural product cancer chemopreventive agent. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3429–3435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson RC. Amphibolic drug combinations: the design of selective antimetaboliteprotocols based upon the kinetic properties of multienzyme systems. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3998–4003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z, El-Deiry WS. Overview of cell death signaling pathways. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2005;4:139–163. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.2.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PH, Christodoulos K, Dobbs N, Thavasu P, Balkwill F, Blann AD, Caine GJ, Kumar S, Kakkar AJ, Gompertz N, Talbot DC, Ganesan TS, Harris AL. Combination antiangiogenesis therapy with marimastat, captopril and fragmin in patients with advanced cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2004;91:30–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kholodenko BN. Cell signaling dynamics in time and space. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;7:165–176. doi: 10.1038/nrm1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WY, Chang DJ, Hennessy B, Kang HJ, Yoo J, Han SH, Kim YS, Park HJ, Seo SY, Mills G, Kim KW, Hong WK, Suh YG, Lee HY. A novel derivative of the natural agent deguelin for cancer chemoprevention and therapy. Cancer Prev. Res. 2008;7:577–587. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knasmuller S, Parzefall W, Sanyal R, Ecker S, Schwab C, Uhl M. Use of metabolically competent human hepatoma cells for the detection of mutagens and antimutagens. Mutat. Res. 1998;402:185–202. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(97)00297-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh CY, Kini RM. From snake venom toxins to therapeutics - cardiovascular examples. Toxicon. 2012;59:497–506. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HY. Molecular mechanisms of deguelin-induced apoptosis in transformed human bronchial epithelial cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004;68:1119–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HY, Oh SH, Woo JK. Chemopreventive effects of deguelin, a novel Akt inhibitor, on tobacco-induced lung tumorigenesis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1695–1699. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JC, Laydon JT, McDonnell PC, Gallagher TF, Kumar S, Green D, McNulty D, Blumenthal MJ, Keys JR, Landvatter SW, Strickler JE, McLaughlin MM, Siemens IR, Fisher SM, Livi GP, White JR, Adams JL, Young PR. A protein kinase involved in the regulation of inflammatory cytokine biosynthesis. Nature. 1994;372:739–746. doi: 10.1038/372739a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma PC, Schaefer E, Christensen JG, Salgia R. A selective small molecule c-MET inhibitor, PHA665752, cooperates with rapamycin. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11:2312–2319. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mersch-Sundermann V, Knasmuller S, Wu XJ, Darroudi F, Kassie F. Use of a human-derived liver cell line for the detection of cytoprotective, antigenotoxic and cogenotoxic agents. Toxicology. 2004;198:329–340. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleary RJR, Kini RM. Non-enzymatic proteins from snake venoms: A gold mine of pharmacological tools and drug leads. Toxicon. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2012.09.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muniyappa H, Das KC. Activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) by widely used specific p38 MAPK inhibitors SB202190 and SB203580: a MLK-3-MKK7-dependent mechanism. Cell Signal. 2008;20:675–683. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murillo G, Salti GI, Kosmeder JW, II, Pezzuto JM, Mehta RG. Deguelin inhibits the growth of colon cancer cells through the induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. Eur. J. Cancer. 2002;38:2446–2454. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namiki Y, Namiki T, Yoshida H, Date M, Yashiro M, Matsumoto K, Nakamura T, Yanagihara K, Tada N, Satoi J, Fujise K. Preclinical study of a “tailor-made” combination of NK4-expressing gene therapy and gefitinib (ZD1839, Iressa) for disseminated peritoneal scirrhous gastric cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2006;118:1545–1555. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto S, Xiang J, Huang S, Lin A. Induction of apoptosis by SB202190 through inhibition of p38beta mitogen-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:16415–16420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.16415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuwinger HD. Plants used for poison fishing in tropical Africa. Toxicon. 2004;44:417–430. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SH, Woo JK, Yazici YD, Myers JN, Kim WY, Jin Q, Hong SS, Park HJ, Suh YG, Kim KW, Hong WK, Lee HY. Structural Basis for Depletion of Heat Shock Protein 90 Client Proteins by Deguelin. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2007;99:949–961. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SH, Woo JK, Jin Q, Kang HJ, Jeong JW, Kim KW, Hong WK, Lee HY. Identification of novel antiangiogenic anticancer activities of deguelin targeting hypoxia-inducible factor-1α. Int. J. Cancer. 2008;122:5–14. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oren M. Decision making by p53: life, death and cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:431–442. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MH, Song HS, Kim KH, Son DJ, Lee SH, Yoon DY, Kim Y, Park IY, Song S, Hwang BY, Jung JK, Hong JT. Cobrotoxin inhibits NF-kappa B activation and target gene expression through reaction with NF-kappa B signal molecules. Biochemistry. 2005;44:8326–8336. doi: 10.1021/bi050156h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng XH, Karna P, O’Regan RM. Down-regulation of inhibitor of apoptosis proteins by deguelin selectively induces apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2007;71:101–11. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.027367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussel D, Dumas JF, Augeraud A, Douay O, Foussard F, Malthiéry Y, Simard G, Ritz P. Dexamethasone treatment specifically increases the basal proton conductance of rat liver mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 2003;541:75–79. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00307-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauro HM, Kholodenko BN. Quantitative analysis of signaling networks. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2004;86:5–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenbergen C. The role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury; relationship to ischemic preconditioning. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2002;97:276–285. doi: 10.1007/s00395-002-0364-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stommel JM, Kimmelman AC, Ying H, Nabioullin R, Ponugoti AH, Wiedemeyer R, Stegh AH, Bradner JE, Ligon KL, Brennan C, Chin L, DePinho RA. Coactivation of receptor tyrosine kinases affects the response of tumor cells to targeted therapies. Science. 2007;318:287–290. doi: 10.1126/science.1142946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toschi L, Janne PA. Single-agent and combination therapeutic strategies to inhibit hepatocyte growth factor/MET signaling in cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14:5941–5946. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udeani GO, Gerhauser C, Thomas CF, Moon RC, Kosmeder JW, Kinghorn AD, Moriarty RM, Pezzuto JM. Cancer chemopreventive activity mediated by deguelin, a naturally occurring rotenoid. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3424–3428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309–314. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson MG, Millar JBA. Control of the eukaryotic cell cycle by MAP kinase signaling pathways. FASEB J. 2000;14:2147–2157. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0102rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui H, Hideshima T, Ikeda H, Jin J, Ocio EM, Kiziltepe T, Okawa Y, Vallet S, Podar K, Ishitsuka K, Richardson PG, Pargellis C, Moss N, Raje N, Anderson KC. BIRB 796 enhances cytotoxicity triggered by bortezomib, heat shock protein (Hsp) 90 inhibitor, and dexamethasone via inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase/Hsp27 pathway in multiple myeloma cell lines and inhibits paracrine tumour growth. Br. J. Haematol. 2007;136:414–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.