Abstract

Purpose of review

The Chicago Classification for esophageal motility disorders was developed to complement the enhanced characterization of esophageal motility provided by high resolution esophageal pressure topography (HREPT) as this new technology has emerged within clinical practice. This review aims to summarize the evidence supporting the evolution of the classification scheme since its inception.

Recent findings

Studies examining the specific esophageal motility disorders in regards to HREPT metrics, clinical characteristics, and responses to treatments have facilitated updates of the diagnostic scheme and criteria. These studies have demonstrated variation in treatment responses associated with sub-classification of achalasia, the use of distal latency in the diagnosis of distal esophageal spasm, and the development of diagnoses including EGJ outflow obstruction and hypercontractile esophagus.

Summary

The diagnostic criteria described in the Chicago Classification have evolved to demonstrate a greater focus on distinct clinical phenotypes. Future evaluation of the natural history and treatment outcomes will assist in further refinement of this diagnostic scheme and management of esophageal motility disorders.

Keywords: Esophageal motility disorders, high-resolution manometry, achalasia, distal esophageal spasm

Introduction

Esophageal manometry is often employed in the evaluation of dysphagia and non-cardiac chest pain. High-resolution esophageal pressure topography (HREPT), a new technology based on a combination of high-resolution manometry (HRM) and esophageal pressure topography, offers several advantages over conventional manometry for the examination of esophageal motility disorders including enabling the development of standardized, objective measurements of esophageal peristaltic and sphincter function [1, 2]. The adoption of this new technology into clinical practice mandated the development of a novel classification scheme for the diagnosis of esophageal motility disorders utilizing HREPT metrics. Such a classification scheme was developed based on the systematic analysis of HREPT clinical studies of 75 asymptomatic controls and 400 patients referred for manometry, and subsequently termed the Chicago Classification [1, 3]. Since its inception in 2007, an international working group has revisited and updated this classification scheme based on increased HREPT clinical experience and research publication [4–6**]. In general, the diagnostic scheme has shifted to include a larger focus on clinical phenotypes. The aim of this review is to discuss the background behind the evolution of the Chicago Classification.

Methodology of high resolution esophageal pressure topography

An HRM device is composed of multiple, closely-spaced pressure sensors (usually 1 cm apart) that are placed transnasally beyond the esophagogastric junction (EGJ). Esophageal pressure topography plots are color-coded pressure representations on a spatiotemporal field generated by sophisticated software-based algorithms for visualizing and analyzing manometric data[7]. HREPT studies entail analysis of (10) 5 mL water swallows performed in the supine position. The normative values and cutoffs in the current diagnostic scheme are based on studies performed and analyzed using an HRM system and Manoview software developed by Sierra Scientific Instruments Inc (Los Angeles, CA, USA) and may vary with different hardware and/or analysis software; however, the principles of diagnosis may be generalized to other manometric systems.

While the initial Chicago Classification was based on analysis of a patient population which included patients who had previously undergone fundoplication or Heller myotomy, the most recent classification scheme is intended to diagnosis primary esophageal motility disorders and not be applied to post-surgical manometric studies [6**]. In these post-procedural cases, interpretation should be considered based on each patient’s treatment history.

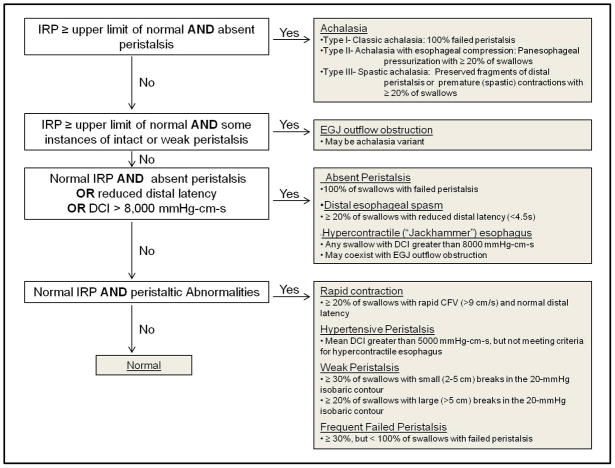

Analysis of an HREPT study is done in a systematic process [3, 6**]. First, each individual swallow is analyzed by applying HREPT specific metrics (see table 1). Lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxation is measured using the Integrated Relaxation Pressure (IRP). Esophageal peristaltic integrity is characterized as being intact, failed, or with small (2–5 cm) or large (>5 cm) peristaltic breaks in the 20 mmHg isobaric contour. Contraction velocity is measured in terms of Contractile Front Velocity (CFV) and Distal Latency (DL). Contractile vigor is measured by the Distal Contractile Integer (DCI). Then, the intrabolus pressure pattern is characterized. Finally, the compilation of the individual swallows is applied to the Chicago Classification scheme to designate a final diagnosis (see Figure 1).

Table 1.

Summary of esophageal pressure topography metrics utilized in the Chicago Classification.

| Definitions of Pressure Topography Metrics | |

|---|---|

|

IRP (mmHg) Integrated Relaxation Pressure |

Lowest mean esophagogastric junction (EGJ) pressure for 4 contiguous or non-contiguous seconds of relaxation |

|

Peristaltic breaks (cm) Peristaltic Integrity |

Gap in the 20 mmHg isobaric contour of the peristaltic contraction between the upper esophageal spincter (UES) and EGJ, measured in axial length |

|

DCI (mmHg-s-cm) Distal Contractile Integral |

Amplitude x duration x length (mmHg-s-cm) of the distal esophageal contraction greater than 20 mmHg from proximal to distal pressure troughs |

|

CDP (time, position) Contractile Deceleration Point |

The inflection point along the 30 mmHg isobaric contour where propagation velocity slows demarcating the tubular esophagus from the phrenic ampulla |

|

CFV (cm/s) Contractile Front Velocity |

Slope of the tangent approximating the 30 mmHg isobaric contour between the proximal pressure trough and the CDP |

|

DL (s) Distal Latency |

Interval between UES relaxation and the CDP |

Figure 1. The Chicago Classification, diagnostic algorithm.

Adapted from Bredenoord, et al. 2012 [6**]. IRP – Integrated relaxation pressure. EGJ – Esophagogastric junction. DCI – Distal contractile integer. CFV – Contractile front velocity.

Abnormal esophagogastric junction relaxation

The assessment of EGJ relaxation is an essential component in the diagnosis of esophageal motility disorders as it encompasses the initial branch point in the diagnostic algorithm of esophageal motility disorders. In addition, abnormal EGJ relaxation is a long-standing component in the diagnosis of achalasia, which is the most well defined esophageal motor disorder and the one with the most effective therapies [2, 8].

Conventional manometry possesses several difficulties in the assessment of LES relaxation. Its shortcomings include accounting for crural diaphragm contraction, intrabolus pressure, deglutitive esophageal shortening, radial asymmetry of the EGJ, and recording sensor movement relative to the EGJ. HREPT is able to remedy these potential confounders and improves the measurement of EGJ relaxation. The initial Chicago Classification described abnormal EGJ deglutitive relaxation in terms of an eSleeve 3 second nadir pressure [3, 9]. Further exploratory studies demonstrated that the 4 second IRP was the optimal measure of EGJ relaxation, as it demonstrated superior sensitivity compared with other measures in the diagnosis of achalasia, and therefore was assimilated into the Chicago Classification [5, 10].

Achalasia

One of the primary objectives of a diagnostic scheme is to help establish a treatment plan. Among esophageal motility disorders, the development of an achalasia sub-classification is one area in which HREPT diagnosis may be most beneficial in planning the type of treatment modality and predicting response to that treatment.

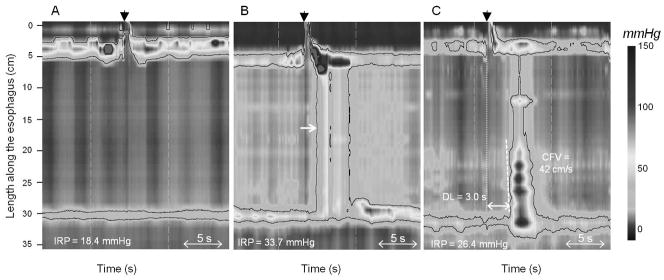

The initial Chicago Classification detailed subtypes of achalasia including classic (“aperistalsis without identifiable contractile activity”) and vigorous (“with persistent contractile activity, spasm, or elevation of intraesophageal intrabolus pressure”) [1, 3]. Subsequent updates of the classification scheme saw the achalasia subtype definitions refined into the current categories of classic achalasia (Type I: absent peristalsis), achalasia with esophageal compartmentalization (Type II: panesophageal pressurization in ≥ 20% of swallows), and spastic achalasia (Type III: no normal peristalsis and premature contractions in ≥ 20% of swallows) [5, 6**]. HREPT plots of the three subtypes are demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. HREPT plots of achalasia subtypes.

Black arrowhead demonstrates beginning of swallow. Each swallow exhibits abnormal esophagogastric (EGJ) relaxation defined by an integrated relaxation pressure (IRP) ≥ 15 mmHg. (A.) Type I, classic achalasia: all swallows with failed peristalsis. (B.) Type II, achalasia with esophageal compression. White arrow indicates panesophageal pressurization seen in the 30mmHg isobaric contour. (C.) Type III, spastic achalasia: premature contraction as demonstrate by distal latency (DL) < 4.5 seconds. CFV – contractile front velocity.

The current sub-classification of achalasia demonstrates separate clinical phenotypes that are helpful in predicting response to therapy. Currently, three separate studies support the predictive value of the achalasia sub-types. While these three studies have minor methodological differences, they offer similar conclusions (see table 2). Pandolfino et al. analyzed 99 newly diagnosed achalasia patients, all with HRM, who underwent balloon dilation, Heller myotomy, and/or Botox injection [11]. Salvador et al. analyzed 246 patients with achalasia, 230 with conventional manometry and 16 with HREPT, and followed patents after undergoing Heller-Dor myotomy [12**]. Pratap et al. analyzed 51 patients with HRM, 45 of which underwent balloon dilation [13**]. Pre-intervention symptom evaluation in each study suggested that chest pain may be more common in patients with Type III achalasia. Response to treatment was consistent across all three studies, with Type II patients having the best and Type III patients having the worst response to treatment. The Pandolfino study even suggests that Type I patients may have a better response to myotomy (compared with dilation or Botox injection) as the initial treatment. Even though Salvador evaluated a large number of patients with conventional manometry and Pratap applied normative values established from a different HREPT system and only had three patients with Type III achalasia, the principle of the achalasia sub-classification into classic (aperistaltic), panesophageal pressurization, and spastic applies. While prospective treatment trials are needed for further evaluation, these initial studies suggest that achalasia subtypes represent unique clinical phenotypes and may offer a method to facilitate planning achalasia treatment.

Table 2. Summary studies demonstrating different responses to treatment based on achalasia sub-classification.

| Pandolfino | Salvador | Pratap | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manometry system | HRM: 36 sensors at 1cm intervals. | HRM: 36 sensors at 1cm intervals Conventional manometry | HRM: 16 channels. 8 channels at distal end 1 cm apart, remaining 8 channels 3 cm apart |

| Definition of achalasia subtypes. ** (All with abnormal EGJ relaxation) |

|

Conventional manometry:

|

Same as Pandolfino |

| Treatment | Botox, Heller myotomy, and/or balloon dilation | Heller-Dor myotomy | Balloon dilation |

| Measure of treatment outcome | Review of clinic records. Repeat interventions. | Symptom score questionnaire | Clinical follow-up |

| Definition of successful outcome | After last intervention, documented subjective improvement. No recommended repeat intervention for > 12 months | Without postoperative symptom score > 10th percentile of the preoperative score | Symptomatic relief requiring no further intervention up to 6 months after a single intervention |

| Follow-up | Mean 19–20 months | Median 31 months | Mean 6 months |

| Result: successful outcome |

|

|

|

HRM – high resolution manometry. EGJ – esophagogastric junction. CFV – contractile front velocity.

EGJ outflow obstruction

A population of patients can be found with abnormal EGJ relaxation with remaining peristaltic activity such that it fails to meet criteria for a diagnosis of achalasia. This pattern was termed functional obstruction in the early Chicago Classification schemes [3–5]. An analysis of a small group of patients (N=16) meeting these criteria demonstrated that they frequently present with dysphagia and/or chest pain and have manometric characteristics similar to a known mechanical obstruction (post-fundoplication) including an elevated intrabolus pressure [14]. The analysis also suggested that while patients respond poorly to balloon dilation or Botox injection overall, they may respond to treatment with myotomy. Pressure attributable to contraction of the crural diaphragm may also contribute to an esophageal outflow obstruction as was evident in one patient in the above study and in a series of patients with hiatal hernia presenting with dysphagia who exhibited an increased intrabolus pressure [15]. The similarity between HREPT patterns observed in this disorder and mechanical esophageal obstructions has been reflected in the most recent update in the Chicago Classification by introducing the designation EGJ outflow obstruction [6**].

While this group of patients may represent those with undetected inflammatory or infiltrating malignant disorder, EGJ outflow obstruction has been suggested to be a variant of achalasia with overlap in both clinical and manometric findings. Further natural history and treatment observation may be able to further characterize this group.

Motility disorders with normal EGJ relaxation

Distal Esophageal Spasm (DES) and nutcracker esophagus are clinical entities characterized by abnormal esophageal function resulting in dysphagia or chest pain. The conventional manometry diagnostic scheme proposed by Spechler and Castell described DES in terms of “simultaneous contractions” and nutcracker esophagus in terms of “high distal wave amplitude” [8]. HREPT introduced new metrics to quantify the speed of contraction [the “contractile front velocity” (CFV) and distal latency] and contractile vigor [the distal contractile integer (DCI)]. The enhanced information supplied by HREPT evaluation of esophageal motility has facilitated further classification and specification of these disorders, providing updated criteria that describe distinct clinical phenotypes.

Distal Esophageal Spasm

The diagnosis of DES that has been defined by manometric criteria (as opposed to clinical, pathologic, or functional criteria) has been a frequent cause of controversy. The early Chicago Classification schemes interpreted “simultaneous contractions,” as described in conventional manometry schemes, as rapid contractions, defined by a CFV > 8 mm/s [4, 5, 8, 16]. However, the CFV is subject to regional variability in contractile velocity within the swallow and the correlation of symptoms with these “spastic” events remains in question [17, 18].

The HREPT metric Distal Latency (DL) has been proposed as an improved measure to represent simultaneous contractions [19*, 20]. The DL is the time from the upper esophageal relaxation to the Contractile Deceleration Point (CDP). A study examining concurrent HREPT and videofluroscopy demonstrated that the CDP is a reliable landmark on the contractile front that signifies the transition from esophageal peristaltic clearance to esophageal emptying [21]. Evaluation of 75 normal controls determined normal limits of DL >4.5 seconds and CFV >9 cm/s (when measured between the transition zone to the CDP) [19*–21].

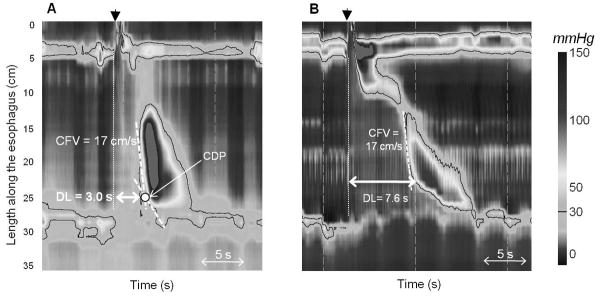

HREPT studies of 1070 consecutive interpretable studies were analyzed, 24 of which were found to exhibit premature contraction (i.e. DL <4.5s) and 67 patients were found to have rapid contractions (i.e. CFV > 9m/s, but normal DL) [19*]. Representative HREPT plots are displayed in Figure 3. Review of medical records revealed that all 24 of the patients with premature contractions had a dominant symptom of dysphagia or chest pain and were diagnosed and managed as DES (6 patients) or spastic achalasia (18 patients). The 67 patients with rapid contractions with normal latency had a more heterogeneous dominant symptom (56% dysphagia, 34% GERD, and 10% other) and were ultimately diagnosed and managed with an array of diagnoses (14 normal, 39 weak, 5 hypertensive, 7 EGJ outflow obstruction, and only two with rapid contraction with normal latency that could potentially have been described as weak peristalsis given large breaks in the 20mmHg isobaric contour plot). This study suggests that the diagnosis of DES based on an abnormal DL defines a more distinct clinical phenotype. Thus, the DL has been adapted into the most recent Chicago Classification to define DES, though further evaluation of clinical outcomes is needed to support this metric [6**].

Figure 3. HREPT plots of distal esophageal spasm and rapid contraction with normal latency.

(A.) Distal esophageal spasm: Appreciate the “simultaneous contraction” as indicated by a distal latency (DL) < 4.5s, measured from the start of the swallow (black arrowhead) to the contractile deceleration point (CDP). (B.) Rapid contraction with normal latency. Notice the regional variability in the contractile front velocity (CFV) demonstrated in the swallow.

Hypercontractile disorders

The finding of elevated wave amplitude has persistently been a part of the diagnostic criteria of nutcracker esophagus. However, elevated wave amplitude alone is not always associated with dysphagia and chest pain as the diagnosis is meant to support [22].

Early versions of the Chicago Classification have defined hypercontractile disorders in terms of mean DCI. Since the development of the Chicago Classification, there has been a distinction between the entity of patients with a mean DCI of 5000–8000 mg-s-cm (termed “nutcracker” or “hypertensive” peristalsis) and those with DCI > 8000 mg-s-cm (the term “spastic nutcracker” was introduced with the initial Chicago Classification), as a mean DCI > 8000 mg-s-cm was a rare finding (3% of 400 evaluated patients), seemed to exhibit a distinct pattern with repetitive high amplitude contractions, and was universally associated with dysphagia and/or chest pain [3]. However, there remained some dissatisfaction with the classification scheme as the criterion of a mean DCI was arbitrary, did not account for a possible single profoundly abnormal swallow, and the scheme did not account for the repetitive contractions that had been observed.

Recent evaluation of HREPT studies of 72 asymptomatic controls and 1070 patients sought to refine this classification [23*]. 44 patients (4.1%) were found to have at least one swallow with a DCI > 8000 mmHg-cm-s, and were defined as hypercontractile. The greatest single DCI seen in the control group was 7732 mmHg-s-cm, with a median DCI 2073 mmHg-s-cm (5–95th percentile 757–5946). Among the hypercontractile patients, the majority (75%) presented with dysphagia, and generally had a positive response to a variety of treatments (including antireflux, anticholinergic, and endoscopic Botox injection). Multipeaked contractions were frequently seen in the patients with DCI > 8000 mg-s-cm (36/44, 86%), and thus the term “Jackhammer esophagus” was coined to describe this pattern (see Figure 4). However, significant differences were not observed between hypercontractile patients with or without multipeaked contractions in terms of symptoms or response to treatments. The most recent update of the Chicago Classification reflects the diagnostic criterion of determining hypercontractile (“Jackhammer”) esophagus based on at least one swallow with a DCI > 8000 mmHg-cm-s, while hypertensive peristalsis (nutcracker esophagus) is defined as mean DCI >5000 mmHg-s-cm but not meeting criteria for hypercontractile esophagus [6**].

Figure 4. HREPT plots of Hypercontractile esophagus compared with hypertensive peristalsis.

(C.) Hypercontractile esophagus: Defined by distal contractile integer (DCI) ≥ 8000 mmHg-s-cm. Notice the multipeaked, “jackhammer”-like contractions. (D.) Hypertensive peristalsis (nutcracker esophagus): defined by DCI > 5000 mmHg-s-cm, but <8000 mmHg-s-cm.

Borderline peristaltic abnormalities

A spectrum of disorders with normal EGJ relaxation remains that do not meet criteria for the major motility disorders (DES, jackhammer esophagus, or absent peristalsis which is defined as 100% failed swallows) but have metrics beyond the 95th percentile seen in normal controls [3, 19*, 23*, 24*]. In the most recent Chicago Classification, these disorders include rapid contraction with normal latency, hypertensive peristalsis (nutcracker esophagus), as described above, weak peristalsis with large or small defects, and frequent failed peristalsis [6**]. Minor changes in the titles and diagnostic criteria have occurred through the updates in the Chicago Classification, but the general principles have remained the same.

Studies utilizing HREPT and intraluminal impedance have demonstrated that peristaltic breaks > 2cm in the 20mmHg isobaric contour plot are associated with impaired bolus transport [24*, 25]. A study examining HREPT characteristics of 75 normal controls and 113 patients with nonobstructive dysphagia demonstrated that weak peristalsis with small (2–5cm) or large (>5cm) peristaltic breaks was only seen in approximately one third of the patients, and though seen in both normal controls and patients with dysphagia, weak peristalsis was more commonly seen in patients. The same study demonstrated that although failed peristalsis leads to impaired bolus transport as well, frequent failed peristalsis was not more commonly seen in patients with dysphagia than in normal controls.

Without a clear association with symptoms or response to treatment, the clinical significance of these disorders of peristaltic abnormalities has yet to be determined.

Conclusion

The advent of HREPT has provided a diagnostic modality with the potential to enhance the diagnosis of esophageal motility disorders. The diagnostic criteria detailed within the Chicago Classification have evolved as clinical use and experience with HREPT increases.

The goals of a diagnostic scheme include accurate classification of patients for inclusion into clinical trials and ultimately to help determine disease-specific treatments. As the technology continues to develop and more data surfaces on the natural history and treatment responses of HREPT-defined esophageal motility disorders, the diagnostic criteria detailed in the Chicago Classification will continue to be revisited and updated. And thus, our views of and clinical approaches to esophageal motility disorders will continue to evolve.

Key points.

The Chicago Classification of esophageal motility disorders has evolved to now hold a greater focus on clinically-relevant phenotypes.

Differentiation of achalasia into subtypes of I.) classic (absent peristalsis), II.) with panesophageal pressurization, and III.) spastic provides a method to predict responsiveness to treatment.

Distal esophageal spasm, when defined by premature contractions measured with distal latency, describes a more clinically homogeneous entity than when defined by contractile front velocity.

Further examination of the natural history and clinical trials using HREPT inclusion criteria are needed for continued revision of the classification scheme.

Acknowledgments

Financial support:

This work was supported by R01 DK079902 (JEP) from the Public Health Service

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

John E. Pandolfino [Given Imaging (Consulting, Educational), Sandhill Scientific (Consulting, Research)]

References

*of special interest

** of outstanding interest

- 1.Fox MR, Bredenoord AJ. Oesophageal high-resolution manometry: moving from research into clinical practice. Gut. 2008;57(3):405–23. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.127993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahrilas PJ. Esophageal motor disorders in terms of high-resolution esophageal pressure topography: what has changed? Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(5):981–7. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandolfino JE, Ghosh SK, Rice J, et al. Classifying esophageal motility by pressure topography characteristics: a study of 400 patients and 75 controls. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(1):27–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahrilas PJ, Ghosh SK, Pandolfino JE. Esophageal motility disorders in terms of pressure topography: the Chicago Classification. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42(5):627–35. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31815ea291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pandolfino JE, Fox MR, Bredenoord AJ, et al. High-resolution manometry in clinical practice: utilizing pressure topography to classify oesophageal motility abnormalities. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21(8):796–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01311.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **6.Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, Kahrilas PJ, et al. Chicago Classification Criteria of Esophageal Motility Disorders Defined in High Resolution Esophageal Pressure Topography. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24(1) doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01834.x. In Press The most recent update of the Chicago Classifcation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clouse RE, Staiano A, Alrakawi A, et al. Application of topographical methods to clinical esophageal manometry. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(10):2720–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spechler SJ, Castell DO. Classification of oesophageal motility abnormalities. Gut. 2001;49(1):145–51. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.1.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pandolfino JE, Ghosh SK, Zhang Q, et al. Quantifying EGJ morphology and relaxation with high-resolution manometry: a study of 75 asymptomatic volunteers. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290(5):G1033–40. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00444.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghosh SK, Pandolfino JE, Rice J, et al. Impaired deglutitive EGJ relaxation in clinical esophageal manometry: a quantitative analysis of 400 patients and 75 controls. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293(4):G878–85. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00252.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pandolfino JE, Kwiatek MA, Nealis T, et al. Achalasia: a new clinically relevant classification by high-resolution manometry. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(5):1526–33. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **12.Salvador R, Costantini M, Zaninotto G, et al. The preoperative manometric pattern predicts the outcome of surgical treatment for esophageal achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14(11):1635–45. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1318-4. This study demonstrates an achalasia-subtype dependent response to myotomy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **13.Pratap N, Kalapala R, Darisetty S, et al. Achalasia cardia subtyping by high-resolution manometry predicts the therapeutic outcome of pneumatic balloon dilatation. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17(1):48–53. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2011.17.1.48. This study demonstrates an achalasia-subtype response to ballon dilation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scherer JR, Kwiatek MA, Soper NJ, et al. Functional esophagogastric junction obstruction with intact peristalsis: a heterogeneous syndrome sometimes akin to achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13(12):2219–25. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0975-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pandolfino JE, Kwiatek MA, Ho K, et al. Unique features of esophagogastric junction pressure topography in hiatus hernia patients with dysphagia. Surgery. 2010;147(1):57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghosh SK, Pandolfino JE, Zhang Q, et al. Quantifying esophageal peristalsis with high-resolution manometry: a study of 75 asymptomatic volunteers. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290(5):G988–97. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00510.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ. AGA technical review on the clinical use of esophageal manometry. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(1):209–24. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barham CP, Gotley DC, Fowler A, et al. Diffuse oesophageal spasm: diagnosis by ambulatory 24 hour manometry. Gut. 1997;41(2):151–5. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.2.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *19.Pandolfino JE, Roman S, Carlson D, et al. Distal esophageal spasm in high-resolution esophageal pressure topography: defining clinical phenotypes. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(2):469–75. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.058. This study describes the use of distal latency in the diagnosis of distal esophageal spasm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roman S, Lin Z, Pandolfino JE, et al. Distal contraction latency: a measure of propagation velocity optimized for esophageal pressure topography studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(3):443–51. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pandolfino JE, Leslie E, Luger D, et al. The contractile deceleration point: an important physiologic landmark on oesophageal pressure topography. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22(4):395–400. e90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01443.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agrawal A, Hila A, Tutuian R, et al. Clinical relevance of the nutcracker esophagus: suggested revision of criteria for diagnosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40(6):504–9. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200607000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *23.Roman S, Pandolfino JE, Chen J, et al. Phenotypes and Clinical Context of Hypercontractility in High-Resolution Esophageal Pressure Topography (EPT) Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.313. epub. This study examines clinical characteristics of hypercontractile esophageal disorders and coins the term “Jackhammer esophagus”. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *24.Roman S, Lin Z, Kwiatek MA, et al. Weak peristalsis in esophageal pressure topography: classification and association with Dysphagia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(2):349–56. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.384. This study examines the clinical characteristics of a group of patients with dysphagia and weak peristalsis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bulsiewicz WJ, Kahrilas PJ, Kwiatek MA, et al. Esophageal pressure topography criteria indicative of incomplete bolus clearance: a study using high-resolution impedance manometry. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(11):2721–8. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]