Abstract

Introduction:

Smoking initiation seldom occurs after emerging adulthood, making prevention critical during this phase of the life course. Among emerging adults, Hispanics have an especially high risk for cigarette use. Emerging adulthood scholars suggest role transitions commonly experienced by this age group may lead to substance use including cigarette experimentation and/or progression, contributing to the high smoking rates exhibited by Hispanics.

Methods:

Hispanic emerging adults (aged 18–24) completed surveys indicating which of a comprehensive list of role transitions they had experienced in the past year. Separate logistic regression models explored the association between each individual role transition and smoking in the past 30 days, controlling for age and gender and using a Bonferonni correction.

Results:

Among the sample of emerging adults (n = 1,390), 41% were male, the average age was 21, and about 21% reported cigarette use in the past 30 days. Losing a job, becoming a family member’s caregiver, starting to date someone new, experiencing a breakup, being arrested, and becoming addicted to illicit drugs and/or alcohol were all associated with smoking.

Conclusions:

The stress associated with navigating through changes in critical periods of the life course may lead some emerging adults to smoke. Future research should be directed toward determining what specific mechanisms make these transitional processes risk factors for smoking. These determinations could prove critical if effective prevention programs are to be designed that lead to a decrease in the smoking prevalence among Hispanic emerging adults.

INTRODUCTION

Understanding what influences smoking among emerging adults is a priority as currently one in three emerging adults smoke in the United States (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012). Smoking initiation seldom takes place after emerging adulthood (Nelson et al., 2008), making effective prevention programs critical during this phase of the life course (Stone, Becker, Huber, & Catalano, 2012). In 2011, Hispanic emerging adults had a higher smoking prevalence (28.4%) than Blacks (25.7%) and Asian Americans (10.1%) (SAMHSA, 2012). Intermittent smoking is common among Hispanic emerging adults (Lariscy et al., 2013), suggesting a future increase in their smoking prevalence if intermittent smoking develops into habituation.

Emerging adulthood is a time of change, identity exploration, and development between the ages of 18–25 (Arnett, 2011). Role transitions experienced during this developmental stage may lead to substance use (Arnett, 2005), including cigarette experimentation and/or progression to nicotine dependence. The stress associated with navigating through changes in critical periods of the life course may lead emerging adults to engage in unhealthy behaviors such as smoking, possibly as a coping mechanism. Because the smoking prevalence among Hispanic emerging adults has not declined as dramatically as among other priority populations (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012), it is possible that role transitions experienced during this period become risk factors for smoking. Hispanics may exhibit a disproportionate number of transitions as their family, work, and school obligations grow in emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2003). This study identified the role transitions experienced by Hispanic emerging adults that were associated with smoking to inform prevention programs for this population.

METHODS

Surveys were completed by participants in Project RED (Retiendo y Entendiendo Diversidad para Salud) (Lorenzo-Blanco, Unger, Ritt-Olson, Soto, & Baezconde-Garbanati, 2012), a longitudinal study of acculturation patterns and substance use among Hispanics in Southern California. Initially, participants were enrolled in the study as adolescents, attending seven high schools in the Los Angeles area. Details on school recruitment, student recruitment, and survey procedures have been published elsewhere (Unger, Ritt-Olson, Wagner, Soto, & Baezconde-Garbanati, 2009). The university’s Institutional Review Board approved all procedures. Participants who self-identified as Hispanic, Latino or Latina, Mexican, Mexican American, Chicano or Chicana, Central American, South American, Mestizo, La Raza, or Spanish were surveyed in emerging adulthood from November 2010 to December 2012. Research assistants sent letters to respondents’ last known addresses and invited them to visit a Web site or call a toll-free phone number to participate in the study. If participants could not be contacted with the information they had provided in high school, staff searched for them online using publicly available search engines and social networking sites. These tracking procedures resulted in 2,151 participants with valid contact information. A total of 1,390 (65%) emerging adults provided verbal consent over the phone, or read the consent script online and clicked a button to indicate consent, and participated in the survey. Those lost to follow-up were more likely to be male but did not statistically significantly differ on age or smoking behavior.

The list of role transitions was developed based on literature reviews and focus groups with Hispanic emerging adults in Los Angeles. The list included 24 nonredundant role transitions. The survey items for these 24 transitions were prompted with “Has this happened to you in the last year?” with responses coded 1 “Yes” or 0 “No.” The 24 items were, “Started dating someone,” “Started a new romantic relationship,” “Got engaged,” “Got married,” “Moved in with boyfriend or girlfriend,” “Broke up with boyfriend or girlfriend,” “Got legally separated from a spouse,” “Got a divorce,” “Had a baby,” “Lost a baby,” “Got a new job,” “Lost a job,” “You were demoted or forced to work fewer hours,” “You were unemployed, seeking work but unable to find it,” “Started college or new school or classes,” “Had to care for a parent or relative,” “Stopped having to care for a parent or relative,” “Had to babysit siblings or family members,” “Stopped babysitting siblings or family members,” “Got extremely ill,” “Overcame serious illness,” “Were arrested,” “Became addicted to drugs or alcohol,” and “Overcame addiction to drugs or alcohol.” The outcome variable was smoking in the past 30 days coded 1 “Yes” and 0 “No.”

Due to the high correlations among the role transitions, a single logistic regression model would have produced multicollinearity. Instead 24 separate logistic regression models were employed to examine the relationship between each transition and smoking, controlling for age and gender. To control for Type I errors due to multiple tests, a conservative Bonferonni correction was used to evaluate statistical significance; p values < .002 (.05/24) were considered significant. Additionally, the events per variable (EPV) rule in logistic regression would have suggested separate models. The EPV rule recommends 15 cases (“Yes” in the dependent variable) for each explanatory variable in the model. With 26 explanatory variables, the analysis would have required 390 (15×26) cases to avoid overfitting the model (Greenland, 1989; Harrell, Lee, & Mark, 1996); this study had 292 smokers. Smoking in the past 30 days was calculated using the estimates from each multivariable analysis by simulation using 1,000 randomly drawn sets of estimates from a sampling distribution with mean equal to the maximum likelihood point estimates and variance equal to the variance covariance matrix of the estimates, with covariates held at their mean values (King, Tomz, & Wittenberg, 2000).

RESULTS

Among the participants, 41% were male, the average age was 21 and about 21% reported cigarette use in the past 30 days (Table 1). The three most common transitions experienced over the past year were starting new classes/education (65%), dating someone new (55%), and babysitting a sibling (52%). Among the 24 transitions, 6 were significantly associated with smoking after the Bonferonni correction with p < .002.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristicsa

| Mean | 95% CI | N | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 21.14 | 21.12, 21.16 | 1,384 |

| Male | 0.41 | 0.38, 0.44 | 1,386 |

| Past 30-day smoking | 0.21 | 0.19, 0.23 | 1,381 |

| Started education | 0.65 | 0.63, 0.69 | 1,345 |

| New dating | 0.55 | 0.53, 0.58 | 1,336 |

| Babysit sibling | 0.52 | 0.50, 0.55 | 1,343 |

| New job | 0.47 | 0.45, 0.50 | 1,344 |

| New romance | 0.44 | 0.41, 0.47 | 1,338 |

| Can’t find work | 0.34 | 0.31, 0.36 | 1,343 |

| Breakup | 0.31 | 0.28, 0.34 | 1,341 |

| Caregiver | 0.22 | 0.20, 0.24 | 1,343 |

| Lost job | 0.20 | 0.18, 0.22 | 1,343 |

| Demotion | 0.15 | 0.13, 0.17 | 1,342 |

| Stopped babysitting | 0.13 | 0.11, 0.15 | 1,340 |

| Moved in w/significant | 0.14 | 0.12, 0.15 | 1,343 |

| Serious illness | 0.12 | 0.10, 0.14 | 1,345 |

| Had a baby | 0.11 | 0.10, 0.13 | 1,344 |

| Engaged | 0.10 | 0.08, 0.12 | 1,343 |

| Overcame illness | 0.08 | 0.07, 0.10 | 1,345 |

| Stopped care giving | 0.07 | 0.06, 0.09 | 1,335 |

| Overcame addiction | 0.05 | 0.04, 0.06 | 1,335 |

| Arrested | 0.04 | 0.03, 0.05 | 1,346 |

| Lost a baby | 0.04 | 0.03, 0.05 | 1,342 |

| Married | 0.04 | 0.03, 0.05 | 1,341 |

| Drug/alcohol addiction | 0.03 | 0.02, 0.04 | 1,342 |

| Divorce | 0.004 | 0.000, 0.007 | 1,343 |

| Legal separation | 0.004 | 0.000, 0.007 | 1,342 |

Note. aNumbers in cells are means, associated 95% CIs, and useful sample size for each concept.

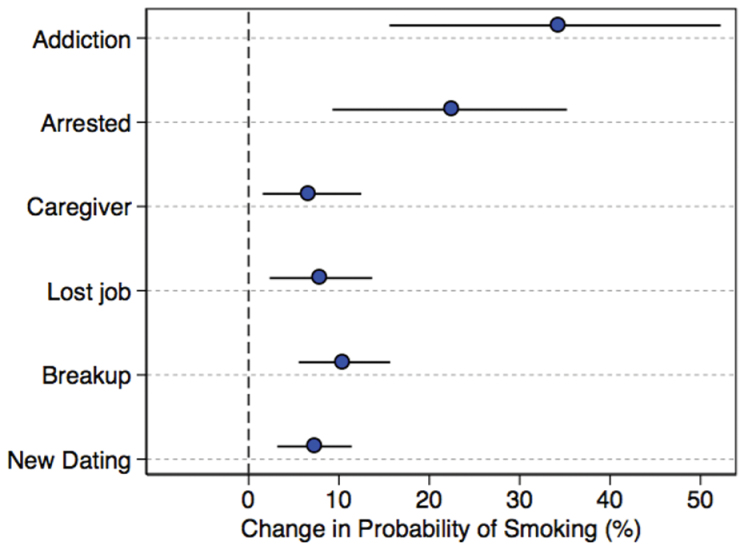

The transition most strongly associated with smoking was becoming addicted to drugs and/or alcohol over the past year. Emerging adults who reported becoming addicted were 34% (95% CI, 16%–52%) more likely to report cigarette smoking compared with those who did not report addiction to drugs and/or alcohol (Figure 1). Being arrested was also associated with smoking. The probability of smoking among emerging adults who reported being arrested was about 41% (95% CI, 29–55) versus 18% (95% CI, 16–20) among those who were not arrested. Loss of a job was associated with smoking; the probability of smoking among those who reported loss of a job was 25% (95% CI, 20–31) versus 18% (95% CI, 15–20) among those who did not lose a job.

Figure 1.

Transitions and smoking show the change in predicted probability of smoking in the past 30 days with 95% CIs. An overlapping CI with zero would have indicated a null result with alpha = .002. Estimates were calculated by simulating the first difference in the transition, for example, lost job changing from 0 to 1. Each estimate was arrived by the use of 1,000 randomly drawn sets of estimates from each respective coefficient covariance matrix with control variables held at their mean values.

Both starting and ending relationships with a significant other were associated with smoking. Emerging adults who started to date someone new in the past year were 7% (95% CI, 3–11) more likely to report cigarette smoking compared with those who did not start dating someone new. The probability of smoking among those who reported having a breakup with a significant other was about 26% (95% CI, 22–31) versus 16% (95% CI, 14–19) among those who did not have a breakup. Finally, being a caregiver for a parent or relative was associated with smoking. The probability of smoking among those who reported having to care for a parent or relative was 24% (95% CI, 19–30) versus 18% (95% CI, 15–20) among those who did not.

Reverse Association

It is possible that smokers are more likely to experience role transitions and, given Project RED’s longitudinal design, data were available to explore these associations by using smoking status in high school as a predictor for each transition in emerging adulthood. This study examined longitudinal data from Hispanic adolescents (average age 16) who completed surveys in the last year of measurement in high school and about 3 years later in emerging adulthood (n = 928). Those who reported smoking in the past 30 days in high school were 14% (95% CI, 5–25) more likely to report having moved in with a boyfriend or girlfriend in emerging adulthood. High school smoking status was not associated with the remaining 23 transitions controlling for age and gender using the Bonferonni correction with p < .002.

DISCUSSION

This study identified six role transitions that were positively associated with smoking among Hispanic emerging adults. The transition most strongly associated with smoking was addiction to alcohol and/or drugs, followed by being arrested. These associations may represent a syndrome of risky behavior that includes cigarette smoking (Jessor, Donovan, & Costa, 1991). Previous studies (Cooper, Rodríguez de Ybarra, Charter, & Blow, 2011; Dietz, Sly, Lee, Arheart, & McClure, 2012) have found that the estimated odds of smoking increased as alcohol consumption increased. However, these studies did not consider role transitions in emerging adulthood. Future studies examining emerging adults may need to consider the specific role transitions in this period as possible confounders of associations between alcohol and tobacco use.

This study also found that becoming a caregiver for a family member was associated with smoking, suggesting additional familial responsibilities may lead to smoking. This is consistent with Arnett’s (2003) observation that Hispanic emerging adults identify obligations to family members as a part of the transition to adulthood. Loss of a job was associated with smoking, consistent with previous studies (Unger, Hamilton, & Sussman, 2004). Emerging adulthood is the period of time where individuals ruminate over their work experiences and begin to investigate career opportunities leading them into the future. Setbacks in this iterative process such as job loss may increase the risk of smoking. Finally, romantic relationships—both positive and negative—were associated with smoking. Starting and ending romantic relationships were common transitions among this sample of emerging adults. Similar to the process of finding a job or settling into a career, dating is an emotional process potentially driving some emerging adults to smoke (Cerbone & Larison, 2000). Not all role transitions were associated with smoking. This could be a function of cell size, as in the case of legal separation, or the role transition may not be perceived as a stressor, potentially not requiring a coping mechanism.

An assessment of reverse association indicated that smokers in high school were more likely to have moved in with a romantic partner in emerging adulthood. This may suggest smokers move out of the family home more frequently compared with nonsmokers due to lifestyle choices such as smoking. Future research should attempt to clarify the role between smoking or other substance use and emerging adults’ exodus from the family home. This early departure may be a risk factor for other problem behaviors in the future.

Limitations of this study include measurement at a single timepoint in emerging adulthood, but assessment of reverse associations should mitigate the limitation of this cross-sectional design. Although role transitions were assessed over the past year and smoking was assessed over the past month, suggesting that the transitions preceded the smoking, it is equally plausible that the smoking initiation occurred before the role transitions. Longitudinal studies could determine whether role transitions precede smoking initiation or whether role transitions are associated with smoking transitions (e.g., initiation to daily smoking). Smoking status relied on self-report and was dichotomized limiting the understanding of smoking frequency. Findings may not generalize to other racial or ethnic groups, and the 24 role transitions may not include all relevant transitions experienced by Hispanic emerging adults that could influence smoking.

Despite these limitations, the findings suggest specific changes experienced by emerging adults are meaningful for Hispanics and should be explored in prevention and intervention programs in the future. For example, programs could teach emerging adults more adaptive strategies to cope with transitions. Future research should determine what specific mechanisms are making these transitional processes risk factors for smoking. It may be the case that smoking becomes a maladaptive coping mechanism during a time of uncertainty and change. These determinations could prove critical if tailored prevention programs are to be designed that lead to a decrease in the smoking prevalence among Hispanic emerging adults.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (5R01DA016310-09).

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Arnett J. J. (2003). Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 100, 63–76.10.1002/cd.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J. J. (2005). The developmental context of substance use in emerging adulthood. Journal of Drug Issues, 35, 235–254.10.1177/002204260503500202 [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J. J. (2011). Emerging adulthood(s): The cultural psychology of a new life stage. In Jensen L. A. (Ed.), Bridging cultural and developmental approaches to psychology: New synthesis in theory, research, and policy, (pp. 255–275). New York, NY: Oxford University Press; [Google Scholar]

- Cerbone F. G., Larison C. L. (2000). A bibliographic essay: The relationship between stress and substance use. Substance Use & Misuse, 35, 757–786.10.3109/ 10826080009148420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper T. V., Rodríguez de Ybarra D., Charter J. E., Blow J. (2011). Characteristics associated with smoking in a Hispanic college student sample. Addictive Behaviors, 36, 1329–1332.10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz N. A., Sly D. F., Lee D. J., Arheart K. L., McClure L. A. (2012). Correlates of smoking among young adults: The role of lifestyle, attitudes/beliefs, demographics, and exposure to anti-tobacco media messaging. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. Advance online publication.10.1016/ j.drugalcdep.2012.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S. (1989). Modeling and variable selection in epidemiologic analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 79, 340–349.0090-0036/89$1.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell F. E., Lee K. L., Mark D. B. (1996). Multivariate prognostic models: Issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Statistics in Medicine, 15, 361–87.10.1002/ (SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361::AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R., Donovan J. E., Costa F. M. (1991). Beyond adolescence: Problem behavior and young adult development. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; [Google Scholar]

- King G., Tomz M., Wittenberg J. (2000). Making the most of statistical analyses: Improving interpretation and presentation. American Journal of Political Science, 44, 341–355 Retrieved from www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/2669316 [Google Scholar]

- Lariscy J. T., Hummer R. A., Rath J. M., Villanti A. C., Hayward M. D., Vallone D. M. (2013). Race/ethnicity, nativity, and tobacco use among U.S. young adults: Results from a nationally representative survey. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. Advance online publication.10.1093/ntr/nts344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco E. I., Unger J. B., Ritt-Olson A., Soto D., Baezconde-Garbanati L. (2012). A longitudinal analysis of hispanic youth acculturation and cigarette smoking: The roles of gender, culture, family, and discrimination. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. Advance online publication.10.1093/ntr/nts204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson D. E., Mowery P., Asman K., Pederson L. L., O’Malley P. M., Malarcher A., … Pechacek T. F. (2008). Long-term trends in adolescent and young adult smoking in the United States: Metapatterns and implications. American Journal of Public Health, 98, 905–915.10.2105/AJPH.2007.115931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone A. L., Becker L. G., Huber A. M., Catalano R. F. (2012). Review of risk and protective factors of substance use and problem use in emerging adulthood. Addictive Behaviors, 37, 747–775.10.1016/ j.addbeh.2012.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) (2012). Results from the 2011 national survey on drug use and health: Summary of national findings, NSDUH Series H-44, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-4713, Rockville, MD: Author; [Google Scholar]

- Unger J. B., Hamilton J. E., Sussman S. (2004). A family member’s job loss as a risk factor for smoking among adolescents. Health Psychology, 23, 308–313.10.1037/ 0278-6133.23.3.308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger J. B., Ritt-Olson A., Wagner K. D., Soto D. W., Baezconde-Garbanati L. (2009). Parent-child acculturation patterns and substance use among Hispanic adolescents: A longitudinal analysis. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 30, 293–313.10.1007/s10935-009-0178-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2012). Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: A report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; [Google Scholar]